Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

New research says, massage beats ice bath for improving recovery

Massage and ice baths are two popular recovery tools runners like to use between workouts so they can prepare their bodies for the next day’s training. Recently, a group of researchers decided to find out which method is more effective and came to the conclusion that runners who want to recover faster should skip the cold water and head to the massage table.

The study

The study, which was published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, included 48 well-trained male runners to perform three workouts. First, they did an exhaustive interval workout followed by an incremental treadmill test 24 hours later at three speeds: 12, 14, and 16 km/h. They then received either a massage, cold water immersion (i.e. ice bath) or passive rest as a control. 48 hours later, they repeated the treadmill test.

The researchers found that the runners who received massage had recovered significantly better than the control group, and had greater stride height and angle changes as they sped up. The runners who received an ice bath, on the other hand, did not appear to experience any noticeable changes compared to the control group. “These results suggest that massage intervention promotes faster recovery of RE (running economy) and running biomechanics than CWI (cold water therapy) or passive rest,” the researcher concluded.

The bottom line

If you’re looking to speed up your recovery after a hard workout, this study shows ice baths may not be as helpful as you think. You’re better off booking an appointment with a sports massage therapist instead. For those of you who aren’t able to get a massage after every hard workout (which is likely most of the running population), foam rolling is another good option that has also been proven to be effective.

Of course, it’s important to remember that neither massage or any other recovery tool will be valuable if you’re not also covering the basics of proper recovery, like stretching and mobility work, proper hydration and good post-workout nutrition. When you nail the basics, you give your body the best chance at staying healthy and injury-free.

(01/26/2022) ⚡AMPby Brittany Hambleton

Why comfort is key when it comes to runners and footwear

The importance of wearing comfortable shoes cannot be overstated.Research shows that we use less energy, are less likely to sustain an injury or fall and we perform better in sports and fitness activities when wearing comfortable shoes. Comfortable footwear is also important in helping us recover from strenuous activity, foot pain or injuries.The concept of comfort is very complex, and there is no single aspect of fit that is more important than others. In fact, individuals tend to prioritize comfort features differently. For example, some people prefer cushioning and don’t notice arch support. Others may say that if the shoe or sandal supports their arch well, they will like it. Fashion of course also influences how we select shoes — some people are willing to sacrifice comfort for style.

Because comfort is highly subjective and thus can’t be measured, I tell my patients to try on several pairs of shoes, make comparisons and then to trust their instinct on which shoes or insoles have the fit, feel and overall comfort they prefer, instead of relying on someone else to tell them what to wear.

I also emphasize that comfort decreases from standing to walking to running so you should move in the shoes or sandals to accurately assess how they feel.

Research suggests that part of how we perceive comfort in footwear has to do with how efficiently we move with the shoes on. If the shoe works with our body’s preferred movement pattern, we will move more efficiently and will perceive it to be more comfortable. Conversely, if the shoe works against our preferred movement pattern, we will move less efficiently and will perceive the shoe to be less comfortable.

Again, this comfort measurement is highly subjective and personal. I encourage people to trust their instincts on comfort after making comparisons.

FACTORS THAT AFFECT COMFORT IN FOOTWEAR

Some of the factors that affect comfort in footwear include fit, cushioning, support, stiffness and climate.

FIT

Matching the shape of the shoe to the shape of the foot in terms of length, width and volume, is an important starting point. Keep in mind that shoe size is inconsistent across brands, so focus more on how the shoe feels, instead of the size number. A recent study found that up to 72% of people are wearing shoes that do not fit them properly. The same study showed that improperly fitting shoes are associated with foot pain. For runners, I emphasize a fit that is snug in the heel and midfoot but allows room for the toes -- the back 2/3 of the shoe should be snug and the toe box should feel roomy.

CUSHIONING

There is probably an ideal amount of cushioning for each individual but we do not have a method of measuring for it. Some people like a lot and some like a little — the “right” amount is whatever you prefer. One concept to keep in mind however is that there is such a thing as too much cushioning. Excessively soft shoes are rarely the answer to address foot pain or injuries.

SUPPORT

This term means different things to different people but often refers to how it feels in the arch and midfoot. As with cushioning, the “right” amount is based on your personal preference.

STIFFNESS

Some shoes are very flexible and some are stiff, the way the shoe flexes under the foot is dependent on the structure of the midsole and outsole as well as the size of the person and the speed at which they run. There is no single ideal amount of stiffness in footwear so the best method is to run in the shoe and and select the style that feels most comfortable to you.

CLIMATE

The shoe’s upper must allow proper dissipation of heat and moisture to help maintain comfort and protection from the environment. Running shoes tend to be very breathable while hiking boots tend to be more weather resistant and less breathable. A quality pair of socks with wicking properties definitely help maximize footwear comfort in combination with the shoe.

In summary, comfort isn’t just about feeling good. There are many health benefits to wearing comfortable shoes. In order to find the best shoe for you, make comparisons, run in the shoes and trust your instincts to determine your personal preferences.

(01/26/2022) ⚡AMPby Paul Langer, DPM

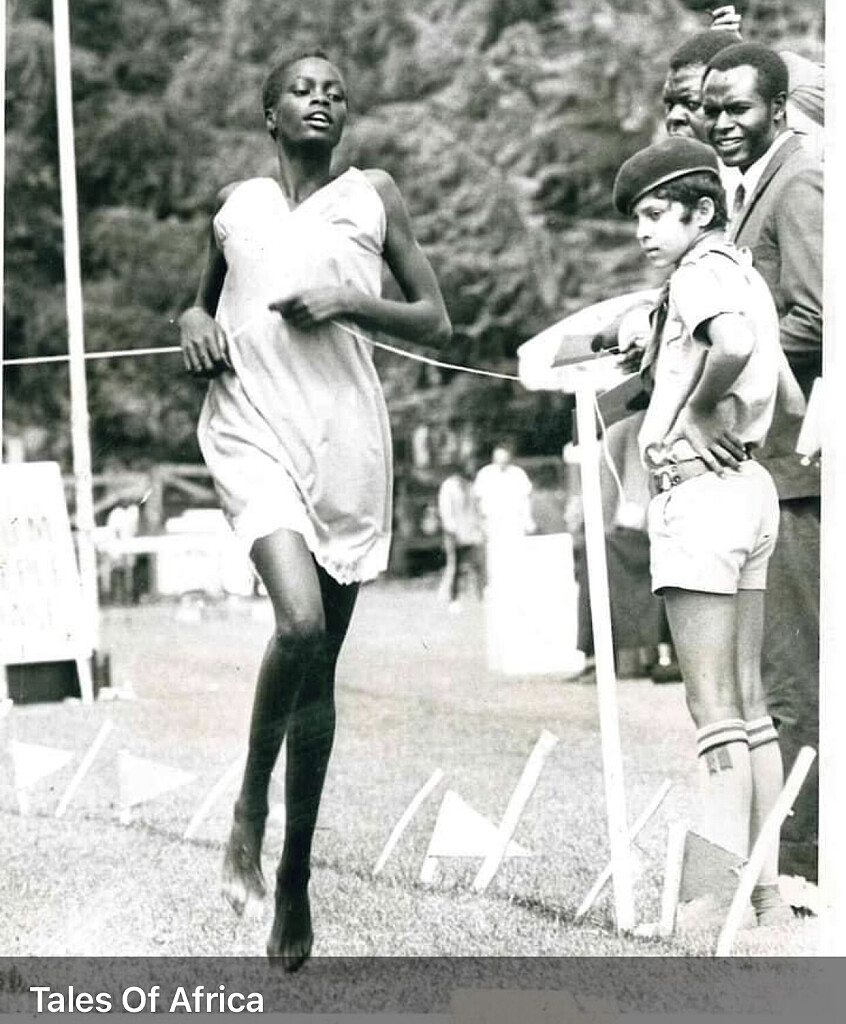

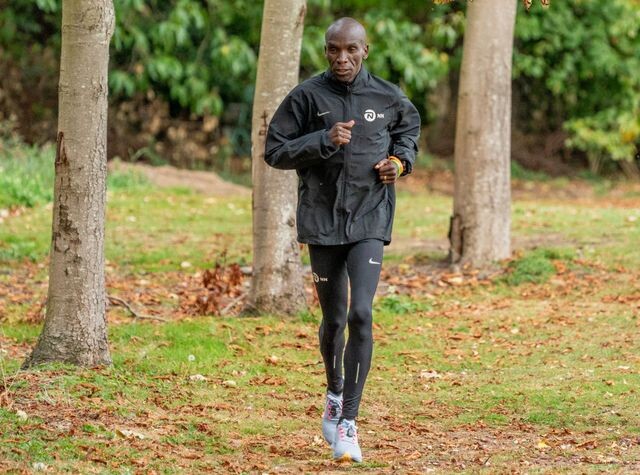

Kenyan Hellen Obiri to move up to the marathon with On

Over the weekend in Northern Ireland, two-time Olympic silver medalist from Kenya, Hellen Obiri, surprised the running world by winning the World Athletics Cross Country Tour Silver event, but not while wearing a Nike singlet. She was instead representing On – a brand that has recently been taking the world of athletics by storm, growing their team of elite-level sponsored athletes, including Canada’s Ben Flanagan.

A year and a half ago, On launched its first professional team, called On Athletics Club, coached by American distance runner Dathan Ritzenhein. “You need world-class athletes to build world-class products,” says Steve DeKoker, On’s head of global sports marketing. “Our goal is to build On as a global brand, and we need world-class athletes to help us develop.” Obiri’s signing is a huge acquisition for the Swiss sporting brand – she is the only athlete ever to win a world indoor, world outdoor and world XC title.

Ben Flanagan signs with On

“We want people that will fit the brand’s competitive values,” says DeKoker. “Both Obiri and Flanagan checked those boxes.” In her debut race wearing On product, the defending world cross country champion won the 8K easily in 26:44.

Obiri will head to the World Athletics Memorial Agnes Tirop XC race in Eldoret, Kenya on Feb. 12, before taking a shot at another 5,000m medal this summer at the 2022 World Championships in Eugene, Ore. “She will move up to the marathon distance in the fall of 2022,” DeKoker says. “And we will have our new premium-plated racing shoe on display for her debut.”

“The full expectation is to develop and supply our athletes with the top-of-the-line product to enhance their performance,” says DeKoker. “There are multiple On super-spikes scheduled to be released this year, with Alicia Monson racing in a pair this weekend at the NYC Millrose Games.”

Both Monson and Flanagan are two recent NCAA champions that DeKoker had his eyes on since they won their titles in 2018 and 2019. “When we found out Flanagan’s contract was up with Reebok, we knew we wanted to support him,” DeKoker says. “We feel he will have the Canadian half-marathon or marathon record in no time.”

For now, the brand plans to go all in to be competitive with the top distance brands on the roads and track, then dipping their feet in the sprint distances for the 2028 LA Olympics.

(01/26/2022) ⚡AMPby Marley Dickinson

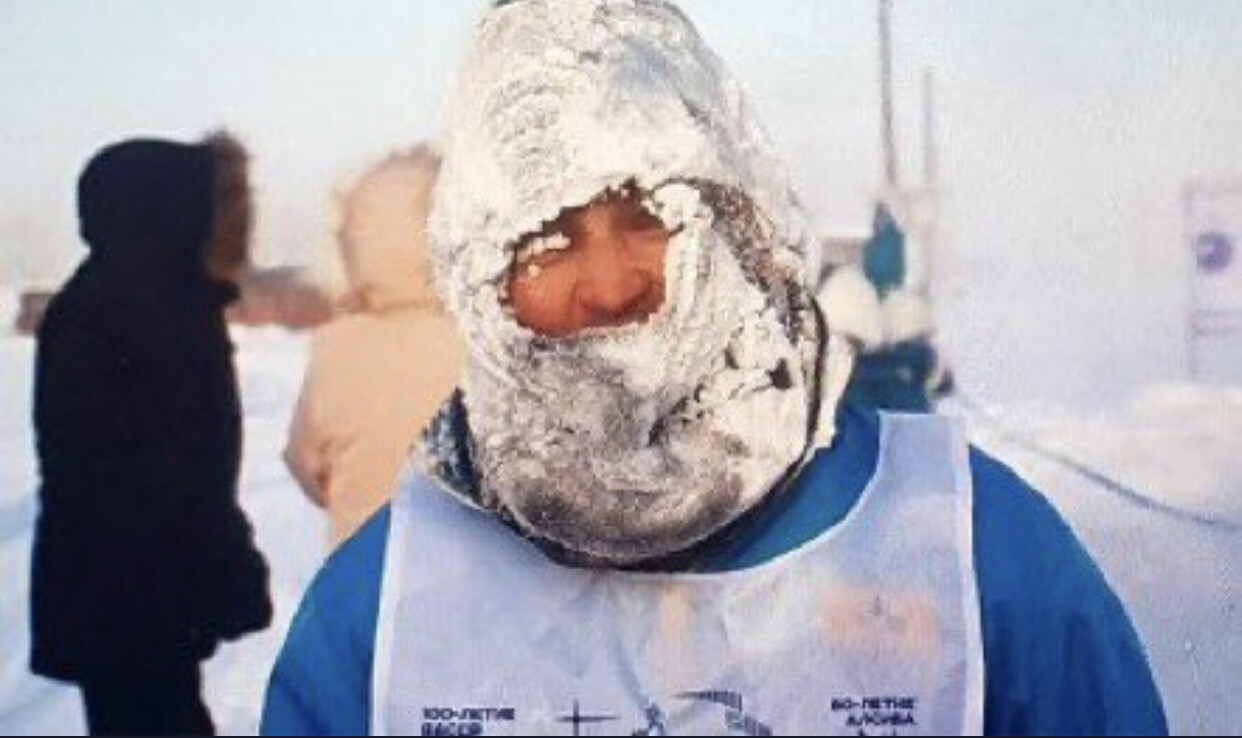

Siberia's Marathon set the official Guinness World Record for the world's coldest marathon

The world’s coldest marathon took place January 22 in Yakutia, Siberia and it was -53C.

The winner was Russia’s Vasily Lukin, who crossed the finish line in 3:22. It was his second straight victory at the extreme race after it was postponed in 2021 due to the pandemic.

The best result among the women was Yakutia local Marina Sedalischeva, who finished in 4:09.

Sixty five runners from the U.A.E., U.S. and Belarus came to Yakutia to brave the frozen conditions. Organizers were forced to start the race early in the morning as temperatures hit -60 C later in the day in Oymyakon, Yakutia’s Pole of Cold.

(01/25/2022) ⚡AMPTry these stair workouts for improved strength and power, stairs are a great addition to any running plan

Whether you’re sick of hills, the weather is forcing you inside or you’re just trying to change up your workout routine, stairs are a great addition to any running regime. These two workouts will challenge your fitness and help you build strength as you prepare for the spring racing season ahead.

The benefits of stairs

Running or jumping up stairs is a type of plyometric or neuromuscular training. Stairs help strengthen your legs, heart and lungs, promote skill development and technique and improve your power and force. Doing plyometrics has been shown to decrease injury rates and improve speed, agility and ground contact time, all of which help you become a better runner.

If you live in an apartment building, stair workouts are a great training option when the weather gets nasty, and if you don’t, the Stairmaster at the gym is also a good option. A stadium with bleachers is great for training stairs outdoors if you have one nearby, but really, any sizeable set of stairs will do.

The other benefit to stair workouts is that because they are such an explosive, high-energy movement, they don’t have to be very long. This is perfect for busy runners who are trying to squeeze a quality workout in between other commitments. They can also be done as a part of a run, but if you’re going to do this, make sure you do the stairs near the beginning of your run for safety reasons.

The workouts

Workout 1

Warmup: 15-20 minute easy jog, or walk up and down the stairs for 5-10 minutes.

Workout: Run up and down the stairs for two minutes, followed by 60 seconds of rest.Hop up the stairs on one leg for 15 steps, walk back down, repeat on the other side.Hop up the stairs on both legs for 20 steps, walk back down, take 60 seconds rest.Run up and down the stairs for two minutes.

Cooldown: 10-15 minute easy jog, or walk up and down the stairs for 5-10 minutes.

Workout 2

Warmup: 15-20 minute easy jog, or walk up and down the stairs for 5-10 minutes.

Workout: 10-12 x 30 seconds up the stairs, jog back down to the bottom and take 20 seconds rest between each interval.

Cooldown: 10-15 minute easy jog, or walk up and down the stairs for 5-10 minutes.

(01/25/2022) ⚡AMPby Brittany Hambleton

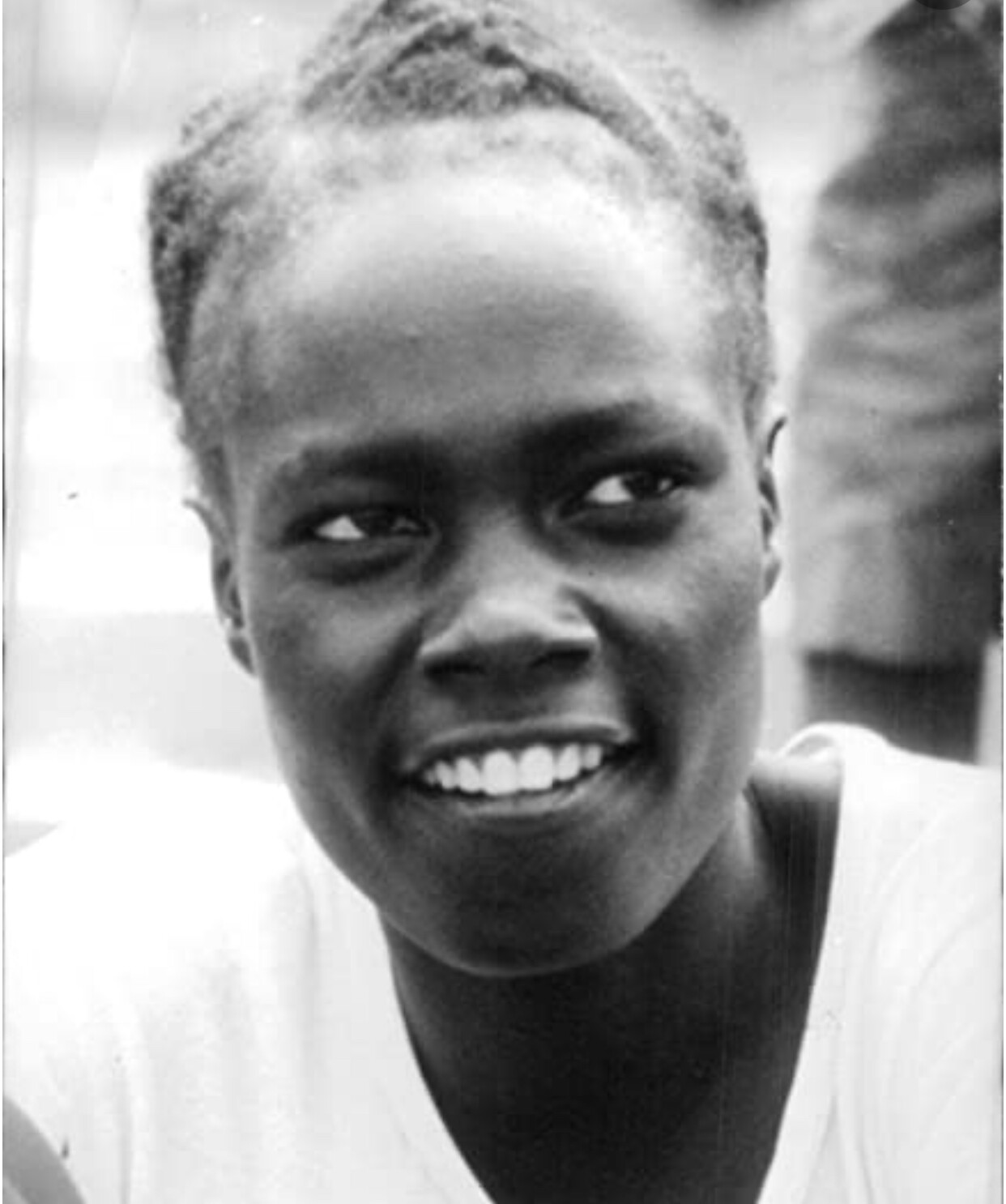

Ethiopian Senbere Teferi set for Agnes Tirop Memorial race

Ethiopia's Senbere Teferi has become the latest international athlete to confirm her participation to next month's Agnes Tirop Memorial World Cross Country Tour.

She joins compatriot world 5,000m and 10,000m record holder Letesenbet Gidey, who is currently training Eldoret and Djibouti’s Ayanleh Souleiman.

Kenyan Geoffrey Kamworor will also take part in the race set for February 12 at Lobo Village in Eldoret, Uasin Gishu County.

Teferi is keen to compete in honor of her departed best friend Agnes Tirop, who was found murdered in her home in Iten, Elgeyo Marakwet County on October 13 last year.

The estranged lover of the 2015 World Cross Country Championships winner, Ibrahim Rotich, is in police custody after denying murder charges.

In an interview with Nation Sport during the Great Ethiopian Run in Addis Ababa over the weekend, Tefere said she was saddened by Tirop’s cruel murder.

She recalled how they became good friends in 2015 when Tirop beat her during the World Cross Country Championships in China where she bagged silver behind the Kenyan.

Since then and they would always talk over the phone for long periods and were both managed by Gianni Demaonna.

“I was touched by the death of Tirop who was my best friend and shared a lot with in terms of competition. Losing such a nice friend in such a manner was really sad and I hope her family will get justice.

I will be starting my season during the Memorial Agnes Tirop Cross Country Tour in Eldoret, Kenya and running there is special for me because I want to honor my departed sister.

We always had a good relationship when we competed because we came from one continent and when a Kenyans win we celebrate, the same way we would when an Ethiopian wins," said Tefere.

She is looking forward to meet some of her competitors when she lands in Kenya in the next few days.

“I have never been to Kenya but I’m looking forward to meet some of the athletes who train there and get to share their experiences. I hear it is a nice place to train,” she added.

She is hoping to use the race to prepare for the World Championships to be held in USA later this year.

“The race in Kenya will gauge my preparations this season but my target is to compete in the 10,000m race where I’m targeting to be in the podium after emerging in sixth position in 2019 during the World Championships in Doha, Qatar,” said Tefere.

During the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games, Tefere finished 10th in the 5,000m won by Dutch’s Sifan Hassan with Hellen Obiri settling for silver and Ethiopia’s Gudaf Tsegay winning bronze.

(01/25/2022) ⚡AMPby Bernard Rotich

Five attributes of a good training partner, if your running buddy possesses these qualities, you know you've got a good one

Training partners can have a profound impact on your performance. Having someone who shows up day after day to suffer through mile repeats or help long runs fly by not only makes training more fun, but can help you improve far more than you would have on your own. Not all running partners are created equal, but if your running buddy has these qualities, you’ve got yourself a great partner-in-crime.

1.- They’re on time

This is a very basic, yet crucial, part of a running buddy arrangement. If your training partner is constantly late to your workouts, forcing you to waste valuable time waiting for them, it’s time to have a hard conversation with them. If, on the other hand, your partner is punctual the majority of the time, it’s a sign that they value you and respect your time.

2.- They aren’t flaky

The point of having a training partner is to have someone to train with — not someone who constantly backs out of workouts and forces you to train on your own. Yes, life happens sometimes and unexpected things pop up, but a good running buddy is someone who shows up every time to put in the work.

3.- They don’t complain

Training partners are there to motivate each other. A good running buddy should always have a positive attitude about even the hardest of workouts to help get you both to the end with smiles on your faces.

4.- They don’t make it a competition

When your training partner is around the same speed as you, it opens the door for competition in workouts. A good running buddy never turns a run or workout into a race, but instead tries to work with you to have the best workout possible. If you end up having a better day and are ahead of them during the workout, they’re happy for you, not jealous.

5.- They keep it fun

Many runners fall into the trap of taking their training too seriously, which sucks the joy out of the sport. A good training partner knows how to keep running fun and lighthearted, so both of you can enjoy your training, rather than stress over it or dread it.

(01/25/2022) ⚡AMPby Brittany Hambleton

Athing Mu switching to women´s wanamaker mile at Millrose Games

Olympic 800 meters champion Athing Mu will test her range further in elite mile field.

Of all the storylines coming together for this weekend's 114th Millrose Games at The Armory, the one making waves Monday is the switch by Athing Mu from the 800 meters to the WHOOP Women's Wanamaker Mile.

On the schedule of Saturday's events, that's only a nine-minute difference in start time. Those two events precede the traditional Millrose closer, the men's Wanamaker Mile.

But with Mu making her first New York City appearance in a race since she was a senior in high school in 2020, she stands to be one of the most compelling athletes in the meet.

Instead of racing in the 800 meters against Ajee' Wilson, Natoya Goule and high school stars Roisin Willis and Sophia Gorriaran, Mu will take on a bigger challenge in the mile against a field that includes Elle Purrier-St. Pierre, the reigning champion, Konstanze Klosterhalfen, Nikki Hiltz and Jessica Hull.

Mu opened her 2022 campaign with a 4:37.99 mile at the Ted Nelson Invitational at College Station, Texas, on Jan. 15, which is a personal best.

The recent Bowerman Award winner may just be scratching the surface in the longer event, and demonstrating the full spectrum of her range from 400 meters to the mile. She'll have to run much faster to compete for the win on Saturday. She already owns the American record in the 800 meters outdoors with 1:55.04.

Purrier ran a meet and Armory record 4:16.85 to win the 2020 race.

(01/25/2022) ⚡AMP

by Doug Binder

NYRR Millrose Games

The Pinnacle of Indoor Track & Field The NYRR Millrose Games, first held in 1908, remains the premier indoor track and field competition in the United States. The 2025 edition will once again bring the world’s top professional, collegiate, and high school athletes to New York City for a day of thrilling competition. Hosted at the New Balance Track &...

more...Useful tips on how to use running to lose weight faster

Running is an excellent way to lose weight. It has been shown that people who run regularly are able to burn more calories than those who don’t, and it also helps build muscle mass which in turn boosts your metabolism. But before you rush out to buy new running shoes, there are some things you should know about how to make the most of this exercise for weight loss. This article will discuss these helpful tips.

Find Yourself A Personal Trainer

Weight loss may seem like something that is easy enough to do on your own without any help, but it’s hard to know where to start when you don’t have any experience. You can buy books or search the internet for weight loss tips, but until you try them out for yourself, there is no way of knowing if they really work. Personal trainers are trained to help you achieve your weight loss goals, and they can create a tailored workout for you that is based on your own personal needs. A good trainer will also be able to offer advice about how to make the most of any exercise you do, including running.

However, when looking for a trainer you should hire, make sure to search Google for “personal trainer cost” to find out how much each trainer costs in your area or in other places as well. Also, make sure to ask about their qualifications and what training they have received that enables them to offer advice about your weight loss plan.

Wear The Right Clothing

When you exercise, the last thing you want is for clothing to be getting in your way or causing discomfort. A good pair of running shoes is a must, but you also need to wear the right clothes. It’s worth investing in clothes that are designed for running rather than just wearing your normal clothes. Do some research online to find out which brands offer the best advice about what to wear when you run, and then go into a store that sells these clothes so you can try them on for size. You can also find these items online and have them delivered to your home, but this will still cost you money and so it’s best if you can try on the clothes first by visiting a store.

Take Advantage Of The Weather

Running outside will burn more calories than running on a treadmill, but this is only true if the weather is decent enough to allow you to run outside. If it’s too cold or wet, then you may want to use a treadmill instead. This can reduce your weight-loss potential, but it doesn’t mean you can’t still lose weight. By doing a treadmill workout every other day, you should still be able to keep your weight loss going and even speed it up. You should consult with your personal trainer to work out the best exercise plan for your needs.

Get An Audiobook

If you find running boring, then an audiobook can help make the experience more exciting and interesting. You can download these books from the internet and they are a great way of making it feel like you aren’t really running when in fact, you are burning plenty of calories. This will help keep your weight loss going for longer. If you’re not a fan of audiobooks, then you can try listening to music on your iPod instead. If this doesn’t work for you, there is nothing stopping you from turning your run into a social occasion by taking a friend with you. You can also find walking apps that allow you to track your route and measure the calories you’re burning, which may make you feel like you’re getting more out of your run.

Don’t Expect Results Overnight

Losing weight can take some time, and you should never enter into any exercise plan expecting fast results. This will only lead to disappointment and quitting before giving yourself a chance to lose the weight you want to. If you set realistic goals and try your best every day, then the results will come and stay with you for longer. Your goal should be to exercise every day, no matter how much weight you have to lose. Once you have lost some of it, then your goal should be to maintain this new healthy weight. This way you will stay healthier for longer and also raise your confidence levels as well.

Don’t Forget To Bring A Bottle Of Water

When you exercise, your body loses water and this needs to be replaced. You need to drink more fluids than usual when you run and this means carrying a bottle of water with you every time you head out. Fill up the bottle at home before putting it in your bag and make sure that whatever type of running plan you’re following allows you to drink plenty of water. Drinking enough water will also help suppress your appetite, which is an added bonus and will help you lose weight faster.

Keep Track Of Your Progress

Lastly, it’s important to keep track of your progress when you are trying to lose weight. Some people like using a journal, while others prefer to use an app on their mobile device or phone. Regardless of what method you choose, keeping track of your results is very important and will allow you to stay motivated throughout the process. This way, if you hit a weight-loss plateau, then you can work out how to get over it and avoid quitting. It’s also important to set short-term and long-term goals and try to stay motivated by working towards them every day.

Losing weight can be a difficult task, but with the right tips and advice, it can be a lot easier. If you’re looking to start running in order to lose weight, then make sure you follow the tips we have provided in this article. By taking advantage of the weather, getting an audiobook, bringing a water bottle with you, and keeping track of your progress, you should be able to see results in no time at all. Remember that losing weight takes time and patience, so don’t give up if you don’t see results straight away – keep going, and eventually, you will reach your goals.

(01/24/2022) ⚡AMPby Colorado Runner

America's greatest distance runners Joan Benoit Samuelson teaches a MasterClass on running

Your mind is just as important as your body when you’re running, but developing a healthy, strong mindset is not always easy. Just like it takes time, dedication and practice to train your body for a race, it requires equal amounts of effort to train your mind, and who better to coach you through that process than America’s running sweetheart, Joan Benoit-Samuelson? Her class, Joan Benoit Samuelson Teaches the Runner’s Mindset, is available now as part of the popular MasterClass series, and will no doubt help you crush your goals in 2022.

“After 50+ years of running, I’m delighted to partner with @masterclass to share my lifelong passion for running,” Samuelson said on her Instagram. “I invite you to join me in this class and make your miles count, on the road and in life. Run on in good health and with fire in your belly.”

For the uninitiated, Benoit Samuelson is one of the most accomplished runners in history. She won the Boston Marathon twice, in 1979 and 1983, and was the winner of the first-ever Olympic women’s marathon in 1984.

Now in her mid-60s, she is also the only woman in the world to have run sub-3 hour marathons in five consecutive decades, her first in 1979 and her most recent in 2010. At the 2019 Berlin Marathon, she ran 3:02, nearly becoming the first woman to clock a sub-3 in six consecutive decades.

Her new MasterClass will cover a range of topics, including goal setting, balancing the runner’s mind, stretches and strength training, running your first marathon and navigating injury. She also shares interesting anecdotes about her early days of running.

“When I first started to run, I ran inside the confines of an old abandoned Army post,” she says in the opening remarks. “And there wasn’t any vehicular traffic allowed in that area at the time, so I would walk from our house to the fort and I would run to my heart’s desire. And then I’d walk home, because I was embarrassed to be seen running on the roads.”

She talks about being the underdog at that first Olympic marathon, the pressure of being an Olympic champion, how running has shaped her life and her desire to give back to the sport.

(01/24/2022) ⚡AMPby Brittany Hambleton

Will Nation and Sarah Jackson claim 3M Half Marathon titles

“The 3M Half Marathon has been good to me,” Will Nation said after crossing the finish line downtown Sunday in first place.

Nation and fellow Austin runner Sarah Jackson notched solid victories on the point-to-point downhill course, besting a field of some 6,000 runners.

Nation, a former Texas track and cross-country standout, first won the Half Marathon back in 2015, just after graduating.

“That was my first road race and first half-marathon,” Nation said of his 2015 win. “So it was my introduction into road racing. Today was the first time I’ve run 3M since then.”

Nation and Samuel Doud took it out fast from the start on Stonegate Boulevard at Gateway Shopping Center, flying through the first mile in 4 minutes, 50 seconds. The pair quickly broke away from the chase pack, which included Longhorns runner Kobe Yepez and John Liddell of Wauwatosa, Wis., and hit the 5-kilometer mark in 15:25.

When they passed the 10K mark on Great Northern Boulevard in 30:51, it was clear that it was a two-man race, as Nation and Doud had nearly a minute on the rest of the field. Just before the 8-mile mark on Shoal Creek Boulevard, Nation put the hammer down, and by the ninth mile he had a 30-second lead on Doud.

“We ran together for around 7 or 8 miles,” Nation said. “I was feeling good, so I decided to test my legs, and I pulled away.”

Nation averaged 4:56 a mile, breaking the tape in 1:04:36, while Doud cruised home second in 1:05:40. John Rice, a recent UT graduate and a two-time track and cross-country All-American, took third in 1:06:34, ahead of Yepez, who clocked 1:06:52. Liddell rounded out the top five in 1:07:54.

“I came here to run a fast time.” said Doud, who ran for American University in Washington. “I’ll be running the Ascension Seton Austin Marathon on Feb. 20, and I’m hoping for an Olympic qualifying time.”

Nation, who ran a personal best of 2:13:24 at the California International Marathon in December, also has his sights set on the Austin Marathon. “It’s good to get a race effort like this in before the marathon, because it’s really kind of a short window between now and then,” he said. “I’d love to win the hometown marathon.”

Jackson was a last-minute entry in the women’s race but wasted no time establishing a big gap on the rest of the field. The 2020 Austin Marathon champion moved into the lead right from the start and passed the 5K mark in 17:54, more than a minute ahead of Jaclyn Range of Ohio. Taking advantage of the cool weather, Jackson averaged 5:47 a mile in what amounted to a solo effort. By the 10K mark (35:42), she was nearly two minutes up on Range.

Jackson, who like Nation was coming off a fast time at the California International Marathon (2:42:27), finished in 1:15:47, a personal best for the half-marathon distance. Range took second in 1:18:37, ahead of Diane Fisher of Ohio, who posted a 1:19:13. Mary Reiser of Baltimore was fourth in 1:20:24, and Austin’s Katy Cranfill took fifth in 1:20:54.

“I went out a little fast and just tried to hang on. I was really in the zone today and felt really smooth,” Jackson said. “I’ve run 3M every year since high school, but this is my first win. You can just cruise on the downhills on this course and use them to your advantage. That’s why I love this race so much.”

The 3M race is known nationwide as one of the fastest half-marathon courses in the country, attracting runners from all over the nation in search of speedy times.

“I ran my best half-marathon yet today,” Range said. “My teammate Diane Fisher and I are both from Ohio. We’ve been running in the snow and cold, so this was a chance to come here and run. Conditions couldn’t have been more perfect."

(01/24/2022) ⚡AMPby Brom Hoban

3M Half Marathon

Welcome to the 3M Half Marathon! This year join over 7,000 fellow runners in Austin, Texas to run a personal best at the 3M Half Marathon. 3M Half is a fun and fast stand-alone half marathon boasting one of the fastest half marathon courses in the country. You’ll enjoy a point-to-point course with mostly downhill running that takes you past...

more...World half marathon bronze medalist Yalemzerf Yehualaw breaks race record at Great Ethiopian Run

Yalemzerf Yehualaw opened her 2022 season in spectacular style by claiming victory at the Total Energies Great Ethiopian Run 10km, taking 38 seconds off her own race record with 31:17.

Her winning time is the fastest 10km ever recorded at altitude, with Addis Ababa standing 2350m above sea level. Gemechu Dida won a close men's race in 28:24, just five seconds shy of the long-standing race record.

Yehualaw, who set the previous event record of 31:55 in 2019, came into the race eager to impress after having to withdraw from the Valencia 10km just two weeks ago. Today she ran a smart race, making her break from long-time leader Girmawit Gebregziabiher, the 2018 world U20 5000m bronze medalist, just past the 7.5km mark after cresting the hill near the National Palace.

At the 9km turn at Urael Church, Yehuawlaw accelerated dramatically and pulled clear of her rival, cruising to the finish line to win by 12 seconds from Gebregziabiher, who clocked 31:29. Double world U20 medalist Melknat Wedu, still just 17 years of age, finished third in 31:45.

The men’s race was much closer, with six athletes still in contention in the final 500 meters. In the end it was Dida who took a surprise victory over former Dubai Marathon champion Getaneh Molla with Boki Diriba finishing third as two seconds separated the podium finishers.

The highest-placed non-Ethiopian athlete was Kenya’s Cornelius Kibet Kemboi, who finished sixth in 28:39. A total of 17,600 runners finished the mass race.

Leading results

Women

1 Yalemzerf Yehualaw (ETH) 31:17

2 Girmawit Gebrzihair (ETH) 31:29

3 Melknat Wedu (ETH) 31:45

4 Gete Alemayehu (ETH) 32:06

5 Bosena Mulate (ETH) 32:17

6 Hawi Feyisa (ETH) 32:18

7 Birtukan Wolde (ETH) 32:22

8 Anchinalu Desse (ETH) 32:38

9 Mebrat Gidey (ETH) 32:42

10 Ayenaddis Teshome (ETH) 32:49

Men

1 Gemechu Dida (ETH) 28:24

2 Getaneh Molla (ETH) 28:25

3 Boki Diriba (ETH) 28:26

4 Moges Tuemay (ETH) 28:31

5 Getachew Masresha (ETH) 28:33

6 Cornelius Kibet Kemboi (KEN) 28:39

7 Teresa Ggnakola (ETH) 28:43

8 Solomon Berihun (ETH) 28:55

9 Ashenafi Kiros (ETH) 28:59

10 Antenayehu Dagnachew (ETH) 29:05.

(01/24/2022) ⚡AMPby World Athletics

the Great ethiopian 10k run

The Great Ethiopian Run is an annual 10-kilometerroad runningevent which takes place inAddis Ababa,Ethiopia. The competition was first envisioned by neighbors Ethiopian runnerHaile Gebrselassie, Peter Middlebrook and Abi Masefield in late October 2000, following Haile's return from the2000 Summer Olympics. The 10,000 entries for the first edition quickly sold out and other people unofficially joined in the race without...

more...Trail Running Mental Superpowers

Trying to pinpoint and identify what exactly leads to mental performance breakdowns in races. That curiosity has driven me to have many intriguing conversations with some of the most experienced athletes and coaches in the sport. There are quite a few different mental deficits that can cause a disappointing race result, but there was one that kept coming up over and over, again.

Almost every athlete and coach referred to the same concept - performance is greatly affected when the actual experience of the race doesn't match expectations or the image the athlete had in their head. Going into any experience with rigid assumptions or beliefs about how you think it's going to go creates the perfect environment for some dysfunctional thought patterns to flourish. Primarily, the inability to adapt to your circumstances.

Be Open-minded and Curious

According to trail runner and coach David Roche, athletes tend to idealize the experience going into a race. When things start the struggle sets in and an athlete hasn't planned for how they are going to respond, it's much easier to shut down, thinking "this experience is nothing like what I thought it would be."

Not only is your brain having to interpret an experience it's not super familiar with, but it's also pretty uncomfortable and even downright painful, at times.

David encourages his athletes to think about the hard stuff they are going to face, long before they get there. Great performances happen in spite of or even because of adversity, not in the absence of it. Every time you face a new challenge, you learn more about yourself. As Courtney Dauwalter has said about low points and dark moments in races, "You don't get to summon those whenever you want." Approach those times with an open mind and the curiosity to discover what you can endure.

They are a gift. Without resistance on your path, you don't get to find out how much you can persist through. You're stronger than you think you are. Give yourself the chance to prove it.

Great performances happen in spite of or even because of adversity, not in the absence of it.

Respond, Don't React

One thing that racing continues to teach me is that I don't have it all figured out. Just when I think I do, there's a new lesson to be learned. There have been many times in a race when things weren't going the way I planned, and I just reacted without logic. Reacting puts you on the defensive.

It often involves a victim mindset and invokes some pretty negative emotions. Anyone else ever had a full-blown pity party on the trail mid-race? Yea, me too.

On the other hand, responding to the same circumstances means taking in the new information and adjusting. Take away your perception or preconceived notions about what the experience means. The mental and emotional flexibility to problem solve a challenge is a superpower when it comes to trail running.

Reacting is a passive action while responding is an active one. Whether it's shifting your race plan, adjusting your perspective, or trouble-shooting a nutrition issue, empower yourself with adaptability.

Persistence Not Stubbornness

Another potential negative outcome of being too mentally and emotionally rigid is stubbornness. When the reality on race day doesn't match the highlight reel you've been running in your head, a common reaction is denial. When things get hard the impulse might be to dig in, and beat the race into submission. The problem with that is it sometimes includes tunnel vision.

When you're so focused on forcing the race to play out in a way that matches your expectations, you miss all the cues and feedback of the reality you're in. Or worse, you ignore them. Stubbornness sets in and you're no longer being an active participant in your race. I'm not suggesting that this mindset means giving up on your goals. It means knowing what you're capable of achieving without believing there's only way for you to do that. To me, persistence means striving towards your goal even if that means taking a different path than you thought it would.

There's nothing more dangerous than falling into the trap of thinking you have it all figured out.

There's nothing more dangerous than falling into the trap of thinking you have it all figured out. Without the curiosity to learn more about yourself, it's hard to push through difficult experiences.

Being prepared and ready to have the most successful performance means equipping yourself with the skills you need to respond and adapt to anything that the trail throws at you. Increased fitness and preparation don't give you increased control. If anything, it just gives you the illusion of it. An open-mind, the willingness to adapt and a Swiss Army knife of mental and physical skills equip you to tap deep into the well of possibilities.

(01/23/2022) ⚡AMPby Trail Runner Magazine

Garmin's 2021 Connect Fitness Report shows gravel bikes, hiking and trail running gained popularity last years

Garmin has announced the latest figures from its Garmin Connect Fitness report, an annual crunching of data from Garmin fitness device users from across the globe.

According to the results, Garmin Connect data showed that the global pandemic had a big impact on the number of indoor activities recorded over the past year, with Garmin customers logging 108.30 per cent more Pilates activities year-over-year.

On top of this, breathwork saw a year-on-year rise of 82.76 per cent and yoga also saw an uptake increase of more than 45.55 per cent.

But that’s not to say that everyone locked themselves inside and worked out ways to stay fit and healthy behind closed doors, because activities performed outdoors in the elements increased by 9.52 per cent year-on-year, with gravel cycling seeing the most growth followed by winter sports.

In fact, Garmin noticed a clear trend in the popularity of a number of outdoor pursuits, with more users apparently enjoying hiking, trail running and walking, all of which saw double digit increases compared with the previous year.

Garmin’s data also delved into regional variations, with South America topping the charts with 125.41 per cent more breathwork activities, 87.51 per cent more gravel rides and 37.6 per cent more trail runs.

Similarly, North Americans were turned on to both yoga and gravel rides, with a 34.39 per cent and 28.54 per cent increase in those activities respectively.

"In the face of ongoing lockdowns and the emergence of new COVID-19 variants, Garmin users logged a record-breaking number of fitness activities in 2021," said Joe Schrick, Garmin vice president fitness segment.

"We already knew that our customers are performance-driven and resilient, and the data proves that even a global pandemic won’t stand in the way of their relentless drive to 'beat yesterday'."

Some of the other more left-field activities that increased in popularity include boating, bouldering, hang gliding and rock climbing, proving that the active outdoor lifestyle is well and truly experiencing its day in the sunshine at the moment.

(01/23/2022) ⚡AMPby Apple News

Montell Douglas becomes GB’s first female summer and winter Olympian

Former 100m sprinter makes history after bobsleigh selection for the upcoming Winter Olympics in Beijing

Montell Douglas has become the first woman to compete for Great Britain at both the summer and winter Olympics after she was chosen as a member of the upcoming bobsleigh squad for next month’s Games in Beijing.

The 35-year-old was a reserve four years ago in Pyeongchang but this time has been selected for the squad and will serve as Mica McNeill’s brakewoman.

McNeill has a wealth of experience in the sport having competed herself in Pyeongchang while she also won a silver medal at the 2012 Winter Youth Olympics.

This will be the first time Douglas has competed on the ice at such a significant event but has steadily progressed alongside McNeil since the former British sprinter took up bobsleigh six years ago.

Since then the pair came fourth in the 2020–21 Bobsleigh World Cup two-women event in Innsbruck while Douglas also finished in the top ten on her Bobsleigh World Cup debut in 2017.

“It’s such a strange feeling. Beforehand, I had thoughts of how it would feel, but I think it’s more of a relief,” Douglas told BBC Sport.

“I’m over the moon to be representing women. There have been many male summer and winter Olympians, so I’m more thrilled about leaving a legacy like that behind than anything else.

“To come full circle, after 14 years and at the end of my career, that blows my mind. You’re never too old, it’s never too late, you should always dream and dream big.”

Douglas represented Great Britain on the track in Beijing 2008 and was the former British record holder over 100m with 11.05 after she ended what was then a 37-year-old record from Kathy Cook. Only Dina Asher-Smith and Daryll Neita have run faster than Douglas.

While it was joy for Douglas in being selected for next month’s Winter Olympics, the same could not be said for Greg Rutherford who missed out on selection in the men’s bobsleigh squad.

Rutherford, who famously won Olympic long jump gold on Super Saturday at London 2012, made his bobsleigh debut earlier this month.

(01/23/2022) ⚡AMP

by Athletics Weekly

World Para Athletics Championships in Japan postponed until 2024

A year after the Paralympics were held in Tokyo, this summer’s World Para Athletics Championships in Kobe have been pushed back again

The World Para Athletics Championships, which were meant to take place between August 26 – September 4 in Kobe, Japan, have been postponed until 2024.

The championships were already pushed back until 2022 from 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic but after a request by the Kobe Local Organising Committee (LOC) that date will be moved again.

“Both World Para Athletics and the LOC have reached an understanding that the competition will not take place in 2022,” said World Para Athletics.

“Both parties are working closely to assess the feasibility of a postponement to 2024 in order to retain the World Championships within the Paris 2024 cycle.”

That means that the next scheduled championships will take place in Paris next year, with Kobe then taking the reins in 2024, the same year France host the Paralympics.

Dubai hosted the last and ninth edition of the World Para Athletics Championships back in 2019.

When Kobe host the event in 2024 it will be the first time that athletes compete at a World Para Athletics Championships in the Far East although both Japan (1964 and 2020) and China (2008) have hosted the Paralympics.

The first World Para Athletics Championships took place in Berlin in 1994 and since 2011 they have been held in the same years as the World Athletics Championships.

It remains to be seen whether the International Paralympic Committee stick to that format because if they do it would mean that the World Para Athletics Championships would take place in 2023, 2024 and 2025.

(01/23/2022) ⚡AMP

by Athletics Weekly

2022 Boston Marathon jacket revealed

The 2022 Boston Marathon celebration jacket has been revealed on the Adidas site. This year’s blue, purple and green edition was designed to commemorate 50 years since eight women became the first ever to run a marathon in 1972.

Sustainability first

In an effort to be more environmentally sustainable, this year’s jacket is made from 100 per cent recycled content, such as cutting scraps and post-consumer household waste. It features a mesh lining, cuffed sleeves and reflective strips for 360 visibility. Like with all past celebration jackets, this smart victory blue piece features the Boston Marathon logo prominently on both the front and the back, marathon finishers can wear their accomplishment with pride.

The jacket is retailing at $120 US and is available along with other Boston Marathon gear for purchase

(01/23/2022) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

How to pace your faster half marathon

Have you ever endured that moment in a race where suddenly your legs cannot run any faster? The sensation of defeat overwhelms you, as your pace slows down and the finish line is still miles away. Many runners are familiar with the crash-and-burn experience in the half marathon distance. They start out fast since they feel good, but then fall off pace with just a few miles to go. You do not have to make that mistake! Keep reading to learn how to pace your fastest half marathon and enjoy a breakthrough race.

Why does pacing matter for the half marathon? For most runners, half marathon pace is not much slower than your lactate (anaerobic) threshold. When you run faster than your lactate threshold, you accumulate lactate at a much more rapid rate. Now, lactate isn’t the big bad we once believed; your body can actually shuttle it from the bloodstream to cells and use it for further energy production. However, a by-product of lactate production are hydrogen ions and other acidic metabolites. These cause a burning sensation in your muscles and a resulting fatigue of the muscles. Your breathing also increases, as you both attempt to consume more oxygen for energy and as your body regulates its acid-base balance.

Essentially, you fatigue at a much quicker rate when working above your lactate threshold than when you run slower intensities. When you start out a half marathon too fast – faster than goal pace – you fatigue more rapidly than you would at goal pace or slightly slower. That’s why the last 3-5 miles of a half marathon feels so difficult when you do not pace appropriately. You sabotaged your race by starting out too fast.

These tips are what I have found that worked for me in running my half marathons, including my PR of 1:34 (here’s how I took 12 minutes of my half marathon time). I have used these strategies on hundreds of runners as I have coached them to half marathon PRs. Of course, every runner is different, but these strategies can help you pace your fastest half marathon.

BEFORE THE RACE:

Warm up with 5-15 minutes of very easy running, three or four strides at race pace, and dynamic stretches. The warm-up elevates the temperature of your muscles, which allows greater force production, and increases blood flow which enhances energy production.

MILES 1-2:

Take these miles steady and slightly controlled. You are tapered, so that will equate to a pretty quick pace. Even if you warmed up before the race, you do not want to jump right into goal pace just yet. Aim for 10-15 seconds slower than your goal pace. Do not weave around other runners. The lateral movements will fatigue muscles you don’t normally use in running. Additionally, weaving will add extra distance to your race and affect your finish time. Let people pass you in that first mile.

MILES 3-9:

Settle into a steady pace. You should have practiced your half marathon pace enough in training where you know how this pace will feel on race day. The effort should feel moderate to moderately hard and relateively sustainable. Don’t obsess over your watch. Check in at your pace but trust yourself and trust your training. Take most of your fuel at this point, so that your body can continue to produce energy.

If you feel tempted to slow down or speed up too much at any point, focus on a few runners around you who are running your speed and pace with them. In How Bad Do You Want It?, Matt Fitzgerald describes the group effect as being how running with others reduces your perceived effort – thus making it easier to run faster than you would on your own. Take advantage of this effect if you find others running your goal pace.

MILES 10-12:

A half marathon will get hard at this point. If you started out conservatively, you should still have fuel in your tank. Maintain your goal pace as best as you can or increase it by 5-10 seconds per mile if possible. If you do pick up pace, do not increase it rapidly, as this costs more energy than a more gradual acceleration.

This is when the race becomes a mental game. You will feel comfortable, but with the proper coping strategies you can run at this effort. This segment of the race is when you should try to pass other runners: focus on one runner, work towards passing them, and then repeat. Passing will distract you from the discomfort. The accompanying surges that come with passing temporarily use a different energy pathway, so they are possible even when you are tired.

MILES 13-13.1:

Push your pace more and more – you are almost done and you are not about to crash and burn at this point (unless it is psychological). I like to count down by tenths of a mile from 12.1 and tell myself to push just a bit harder with each tenth that passes. Give your hardest effort over the final tenth.

FINAL NOTES ON PACING:

Focus on the mile you are in. Don’t worry about how you will feel in the next mile or at the end of the race.

Don’t stare at your GPS instant pace (trees and skyscrapers can throw it off). Instead, set it to show lap pace and check in on your mile or km laps to determine if you are running on pace.

Bad miles and good miles alike occur in a race. Don’t stress over a mile split that is too fast or too slow – simply get back to goal pace and focus on the next mile.

Make sure you have a solid nutrition plan to support the energy pathways needed to finish strong!

If this is your first half marathon, use a similar strategy but do not worry about your finish time as much. Make it a goal to start controlled and finish strong!

(01/22/2022) ⚡AMPby Laura Norris Running

What is the best and worst type of crowd support during a race?

Have you been in the final stages of a race and some encouragement from a friend or stranger motivated you to step on the gas and finish strong? Normally spectators shout at runners, “Keep going!” or “You got this!” or “Only one kilometer to go,” but does this positive encouragement have any benefit on the athlete?

Researchers out of Plymouth Marjon University in the U.K. released a study in the Journal of Human Kinetics on how crowd encouragement can boost the runners’ performance.

The study was done on over 800 runners who completed the 2021 London Marathon, and an additional 14 runners were interviewed on the support they received from the crowd. Runners found that the most valuable encouragement they received was personal, authentic and non-judgmental.

It was no surprise that positive encouragement affected 95 per cent of runners mentally. The results found that false information about the distance or race was the worst type of encouragement besides swearing. Both were described as unhelpful for runners.

The most helpful type of encouragement was personalized to the runner, for example, keep up the hard work (name), which is easy enough with names printed on bibs. The survey found that personal encouragement from a stranger can motivate you to keep going when you’re struggling.

The study concluded by recommending spectators to be empathetic and respectful to runners before voicing encouragement.

(01/22/2022) ⚡AMPby Marley Dickinson

How does Aleksandr Sorokin train for 100-mile world records?

Aleksandr Sorokin of Lithuania became the first man to break the 11-hour barrier for 100 miles. After breaking the 100-mile record, he broke his 12-hour world record, covering 177.4 kilometres (approximately 4:04/km) at the 2022 Spartanion race in Tel Aviv, Israel.

To put Sorokin’s performance in perspective, his time is equivalent to running 35 straight 5Ks in 20 minutes and 15 seconds each, which is a very good 5K time for any runner.

He broke his previous 100-mile world record by 23 minutes and his 12-hour record by seven kilometres. We spoke with Sorokin after he set his world records to get a grasp of his training and what’s next for the Michael Jordan of ultrarunning. So how does he train for speed above 50 miles?

“I am just following my running plan,” Sorokin says. “My coach, Sebastian Białobrzeski, has shown me the importance of the long run. We will often do 40-50km runs during training to build up my pain tolerance.” Sorokin’s base mileage sits around 200 kilometres per week, with his peak training weeks hitting 300 kilometres.

“After that, you just need to trust your training and pray everything else will be OK,” says Sorokin.

In the lead-up to his Spartanion race, Sorokin spent several weeks at altitude in Kenya’s renowned Rift Valley, which stands at 2,500m above sea level.

Sorokin fuels his body with junk food during his races. (i.e., chips, chocolate, candy and pop). He does this to keep his sodium and energy levels high during ultra races.

When we previously interviewed Sorokin, he mentioned that his decision to go after the 24-hour world record came after the 24-hour European Championships were cancelled in 2021. In 2022, the championships are back on and scheduled to take place in Verona, Italy in September. Sorokin has his eyes on the prize: “My main goal for the past two years has been winning the European 24-hour Championships,” Sorokin says. “I do want to do races in North America, but in the pandemic, it’s hard to make concrete plans.”

Sorokin also mentioned that he wanted to try some shorter distances in cooler climates over the next couple of months, but when we asked if he would be tackling any five or 10K races, he laughed, “I don’t run anything less than 10K.”

We may not be seeing Sorokin in a 5,000m race on the track anytime soon, but the 40-year-old ultrarunner carries an impressive 5K personal best of 15:45, which he ran last year in his hometown of Vilnius, Lithuania.

(01/22/2022) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

One Vancouver runner has taken 'plogging' to the next level

One year ago, Vancouver’s David Papineau was struggling to find the motivation to run. He was looking for a new challenge after running every street in the city. Papineau remembered the reason he originally stayed in Vancouver, his love for the outdoors and, of course, the moderate climate compared to his hometown, Calgary.

Over the next 10 months, Papineau picked up approximately 24,000 face masks off the streets of Vancouver. “On my runs, I couldn’t help but notice more pollution on the ground,” he says. “I began picking them up and recording each one in a spreadsheet.”

The act of picking up garbage while you run is called plogging, a combination of jogging and the word pick-up in Swedish (plocka upp). It is described as an eco-friendly exercise where people pick up trash while exercising as a way to clean up the environment.

“With more people working from home, there’s more pollution in areas you wouldn’t usually expect it,” Papineau says. “Parking lots, bus stations, parks and hospitals have become hotspots for mask pollution.”

As a runner at heart, Papineau eventually has a goal with his cleaning-up efforts. “I take a lot of pride in cleaning up these masks,” he says. “It’s become my obsession, like marathon running is for other runners.”

Papineau hopes to collect 30,000 face masks by March 30. “That is the day I began the challenge in 2021 – and it motivates me to get out the door and help this city become a cleaner space,” he says. Papineau brings his phone on each run to document each milestone, uploading pictures on his Twitter and Instagram.

For those who are looking to start plogging in your local community, it doesn’t take much equipment. A pair of salad tongs, gloves and a durable/breathable bag you can carry. “Don’t get hyper-focused on picking up everything, as you won’t get very far,” Papineau says. He suggests planning your route and picking up just one type of garbage, like coffee cups.

Papineau’s efforts to clean up Vancouver have not been ignored. The type of bag he uses to collect the masks is from a Victoria, B.C. bakery called Porto-Fino. Nick Mulroney, the son of the former prime-minster Brian Mulroney, reached out to Papineau asking about the type of bag, later to find out Mulroney invested in the small Vancouver Island bakery.

(01/22/2022) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

How to Actually Stick to Your Goal Pace During Intervals

Run your intervals at the right speeds to make sure you’re getting the most out of each effort.

Getting faster doesn’t happen overnight. To run a faster marathon, for example, you have to first pick up the pace during short segments. When those short segments start to feel easy, you can start extending the amount of time you spend at that pace—eventually to as long as 26.2 miles.

That’s the benefit of interval training, a.k.a doing short, high-intensity efforts followed by low-intensity rest or recovery. With this approach, you can clock more high-intensity effort overall than you would during a steady-state run.

Imagine running your fastest mile pace for one mile—you might make it, but collapse at the end. Now, think about running your fastest mile pace for just 400 meters (about one quarter of that mile), followed by a two-minute recovery. You’d likely be able to repeat that six times, which adds up to a mile and a half of quality effort—something that you might not be able to sustain in one go.

So, if you’re looking to get faster in any distance, intervals are a key workout to have on your training plan—and to maximize the benefits of these speed sessions, you have to find the right pace for you.

Why Interval Runs Need a Place on Your Training Plan

On a physiological level, intervals improve your body’s oxygen uptake abilities (a.k.a. your VO2 max), according to a 2015 study published in the journal Sports Medicine, so your working muscles can use that oxygen more efficiently and running will feel easier at a given intensity level.

Interval training also leads to greater mitochondrial adaptations compared to continuous training, 2017 research published in the Journal of Physiology found. Your mitochondria—the powerhouses of your cells—produce aerobic energy, which powers the majority of endurance running.

Intervals are also proven to make you faster over time: Trail runners who did interval training for six weeks ran 5.7 percent faster in a 3,000-meter track test in a 2018 study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. As your body gets used to maintaining faster paces for shorter periods, holding that pace for longer efforts will start to feel easier.

But not all intervals are created equally. Short intervals help you develop muscular strength and power, while longer intervals train your body to better buffer lactic acid, so you tire less easily, explains Danny Mackey, head coach of the Brooks Beasts, one of America’s premier middle-distance track teams. Treating every interval like an all-out sprint can tank your workout from the first rep. On the other hand, figuring out how to properly pace a speed workout can feel intimidating. These tips will help you find your footing.

How to Figure Out Your Interval Run Pace

In general, the shorter the interval, the faster your pace (the same way you’d run a 5K faster than a marathon).

Many training plans use race paces as reference points for intervals. For shorter intervals, you might aim for mile or 5K pace, while longer intervals call for half marathon or marathon pace. If you’ve raced those distances, that’s easy enough to figure you out. You can also pull your average mile pace for any recent race distance and then use a pace calculator to determine your other race paces.

But if you’ve never raced, that’s okay! “The talk test is a good gauge for new runners with no time history,” says Marnie Kunz, a USATF- and RRCA-certified run coach, NASM-certified trainer, and founder of Runstreet. “Intervals should be hard enough that you can’t carry on a conversation, while your recovery efforts should be at a conversational pace.”

When you’re ready to get more specific with your interval pacing, you can do a time trial or benchmark workout, says Kunz. It’s basically like doing a race minus the race environment. During this type of run, you choose a distance—say, a mile—and then attempt to run it as fast as you can. Then, you can use that pace to determine interval paces.

Reminder: Those race or benchmark paces are a measure of your current fitness. So if you’re looking to hit a goal pace in a certain race, that’s your starting point, says Mackey. “You start where you’re at, and [throughout training] you’ll start noticing that hitting that pace feels easier,” he says. That’s when you start going faster.

That said, it’s a lot easier to run a 400- or 800-meter effort at your 5K pace than a whole 5K—so you can set a goal pace at which you run your intervals that’s a little faster than your average time, says Kunz. For example, if your current 5K personal best is a 7:15 average pace, your 5K goal pace for intervals may be a 7:00. When those 5K repeats at 7:00 feel less intense, it might be time to extend the length of the intervals for that pace.

How to Actually Stick to Those Interval Paces

The point of intervals is to stay consistent—if you run at an all-out sprint for one interval and then go twice as slow for the others, that pretty much defeats the point of the workout, says Kunz. “The biggest mistake runners make is going out too fast,” she says. “It’s better to start a little slower and get slightly faster with each interval.” That goes for within each interval, too—you want to eeeease into it instead of kicking things off at your top speed and slowing down from there.

FYI, that also applies to recovery periods. How long you recover will depend on the type of workout you’re doing. A general rule of thumb is to recover for half or the same amount of time as the work itself (i.e. 200 or 400 meters after a 400-meter interval). If you’re looking to start each effort as close to 100 percent as possible, your heart rate should come down to under 120, or about 60 percent of your maximum heart rate, during recovery, says Mackey. Shorter recoveries ramp up the intensity of the workout because they don’t give your heart rate time to drop.

To make sure you’re not starting out to fast and giving yourself proper recovery, try these tactics for sticking to your interval run goal pace:

Go off RPE

One of the best ways to stick to your paces is to gauge your rate of perceived exertion, or RPE, on a scale of one to 10. Recovery efforts should fall on the lower end of the scale, between numbers one through three; high-intensity efforts should be closer to seven through 10 (the shorter the interval, the higher it should fall on that scale).

“If you’re not sure if you’re going hard enough, give it a month and see what you learn about your body,” says Mackey. “It’s uncomfortable to be training at those higher RPEs, but I guarantee you’re not only getting more fit, but you’re going to be able to better handle those more intense efforts.”

Integrate Tech

On the flip side, you can turn to tech to help you stay on pace. Certain running watches—like most Garmins and the Coros Pace 2—actually let you program a workout, including goal paces, in their partner apps. When you sync it to your watch and start running, the watch will beep or buzz during intervals to alert you as to whether you’re going faster or slower than your goal pace.

If you don’t love the idea of looking at your watch during intervals, NURVV running insoles, which use 32 different sensors to capture biometric data, have a Pace Coach feature in the partner app where you can program interval workouts. Then during your workout, you’ll get audio, visual, and haptic (if you have an Apple Watch) coaching based on your cadence and step length measurements to help you hit your target pace.

It’s very rare that the pros are picking themselves off the track, he adds—which means you shouldn’t feel entirely depleted at the end of an interval session, either.

The best way to end an interval session is to feel like you’ve got just one or two more reps in the tank, he says. That’s a pretty good indication that you put in the work, but will be ready to hit the ground running again in another 24 to 48 hours.

(01/22/2022) ⚡AMPby Runner’s World

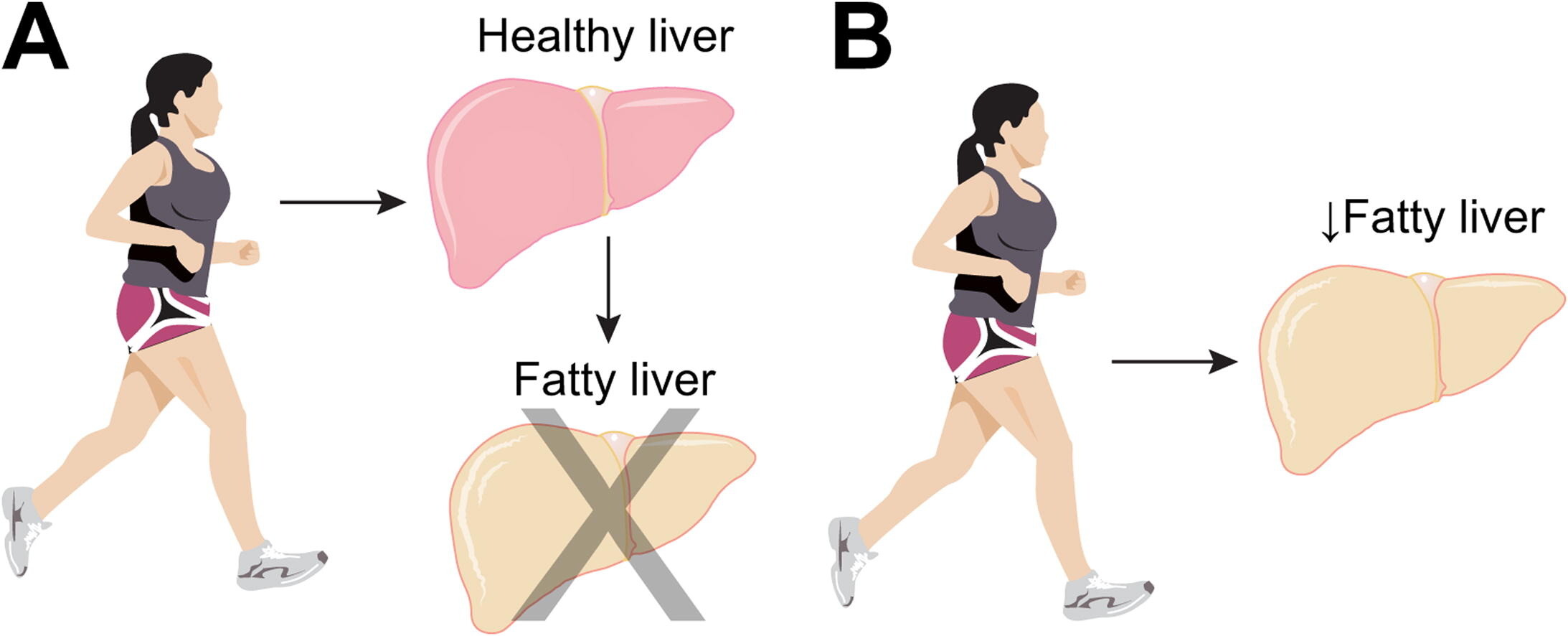

Exercise can help prevent fatty liver disease, new research suggests. Here’s why that’s a big deal.

Running and strength training are two activities that may prevent a condition known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), new research shows.

This may be due to the fact that exercise aids in lowering inflammation in your body and builds lean muscle mass that can help replace fat—both factors in the cause of NAFLD.

Running is beneficial for your heart, brain, and muscles—and new research suggests your liver could see the advantages as well.

A condition known as metabolic liver disease or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) involves fat deposits in the liver that increase over time and negatively impair your mitochondria (which play a role in turning the energy we get from food into energy our cells can use). That can impact how you metabolize carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins, and can lead to organ damage if not addressed.

A recent study in the journal Molecular Metabolism suggests that exercise can change mitochondrial function enough to reduce development of fatty liver deposits. Researchers fed mice a high-calorie diet to prompt liver fat development, then had some of them do treadmill training for six weeks. At the end of that time, those who’d been running showed more regulated liver enzymes and better mitochondrial activity.

Previous studies on people have shown the same connection between better liver function and regular exercise. For instance, a 2016 randomized clinical trial on those with NAFLD showed that vigorous and moderate exercise improved liver health markers. And commentary in 2018 in Gene Expression noted that exercise increases fatty acid oxidation and prevents mitochondrial damage in the liver.

Although preventing NAFLD might seem less important than other warding off other health risks like cardiovascular disease, cancer, or dementia, the condition’s prevalence rate indicates that it’s a major health problem—and it could get worse. When the disease shifts to a more severe form, it’s called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and it causes liver swelling and damage.

According to the American Liver Association, about 1 in 4 people have NASH and most are between the ages of 40 and 60. Up to a quarter of those with the condition develop cirrhosis, late-stage scarring in the liver that may require a transplant.

A 2018 study estimates that NAFLD will increase by 21 percent from 2015 to 2030, while NASH is expected to rise by 63 percent in the same timeframe. Those researchers anticipate that deaths due to these liver conditions will increase by 178 percent by 2030.

“The good news is that lifestyle changes can make a big difference, both for preventing NAFLD, as well as controlling or even reversing the condition if you have it,” Jeff McIntyre, NASH program director for the Global Liver Institute, told Runner’s World.

He said that in addition to regular activity like running, other lifestyle strategies include avoiding foods with added sugar—a potentially major cause of liver inflammation, he said —and incorporating strength training into your routine, since lean muscle mass can help replace fat.

“There are no approved medications yet for NASH or for NAFLD, so the main strategy for prevention and treatment is exercise and nutrition,” he said. “Plus, you’ll benefit other aspects of your body at the same time, like your cardiovascular system and cognitive health. So movement really is medicine.”

(01/22/2022) ⚡AMPby Runner’s World

Canadian Reid Coolsaet signs with Salomon

Since making the jump from the roads to the trails, Canada’s Reid Coolsaet has already begun making a name for himself and brands have taken notice. The two-time Olympian announced Thursday he had signed a sponsorship agreement with Salomon heading into the 2022 ultra-trail racing season.

Coolsaet is one of Canada’s most successful distance runners. He represented Canada twice in the Olympic marathon (London 2012 and Rio 2016) and has competed on the track at multiple World Championships and international competitions. In 2011, he ran the second-fastest marathon by a Canadian athlete at the time, finishing third in the Toronto Waterfront Marathon with a time of 2 hours, 10 minutes, 55 seconds. Today, he still holds the fifth-fastest Canadian marathon time in history.

Even after his Olympic days had come to a close, Coolsaet continued his career, turning his attention to master’s records. In June 2020, he ran 14:39 over 5K for the Canada Running Series virtual Spring Run-Off, breaking the Canadian M40 5K record of 14:42 held by Steve Boyd. His time was not ratifiable, but demonstrated he was still competitive in the sport.

Recently, he’s pivoted yet again, this time to the ultra-trail running scene. In August 2021, he won his debut ultra-trail race, placing first at the Quebec Mega Trail 110K in 14:24:16 despite taking a wrong turn and running 10K more than the rest of the field. Thanks to his partnership with Canadian company Stoked Oats, he was granted entry to this year’s Western States Endurance Run, and will be lining up in Olympic Valley, California on June 25.

“We are thrilled to announce that Reid Coolsaet is joining our Salomon Canada elite running team,” says Sr. Marketing Manager at Salomon Canada Virginie Murdison. “Reid is a prominent figure in the Canadian running scene, a well-regarded coach, and exemplifies Salomon’s values of inclusivity, clean sport, encouraging every individual to get outside and play. We are excited to partner with Reid as he takes on new adventures on and off the trails.”

Running fans across the country have been excited to see Coolsaet back on start lines (and podiums), and with this new sponsorship, Canadians everywhere will be excitedly waiting to see what he does next.

(01/21/2022) ⚡AMPby Brittany Hambleton

Abel Kipchumba, Brigid Kosgei among marquee names for the 2022 RAK Half Marathon

A stellar line-up of world-class runners will be a part of the 2022 Ras Al Khaimah Half Marathon on February 19 (Saturday) as organisers Ras Al Khaimah Tourism Development Authority (RAKTDA) Tuesday revealed the race route and technical sponsors.

Vying for top spot in the world’s fastest half marathon is Kenya’s Abel Kipchumba and Brigid Kosgei, who will both compete against recently announced international elite athletes Jacob Kiplimo, and reigning champion of the 2020 Ras Al Khaimah Half Marathon, Ababel Yeshaneh.

With a goal of bettering her personal best time of 1:04:49, current Marathon world record holder Kosgei is an experienced and highly sought after runner and makes an excellent addition to the impressive elite line up confirmed so far. Kosgei’s achievements include second place in Olympic Games, first place in both the 2020 and 2019 London Marathon and second place in the 2020 Ras Al Khaimah Half Marathon.

Joining Kosgei is male elite athlete, Abel Kipchumba, who famously secured the second fastest time in the 2021 Half Marathon distance category, with an incredible personal best of 58:07.

Looking to beat his personal best time, Kipchumba is expected to deliver an exciting competition and add to a series of world-class records which includes first place at the 2021 Valencia Half Marathon and 2021 Adizero Road to Records, and second place in the 2020 Napoli City Half Marathon.

The race will once again return to the stunning Marjan Island, set against the picturesque backdrop of the Arabian Gulf, treating all athletes to pristine views of the nature-based Emirate’s white sandy beaches and shimmering coastline.

(01/21/2022) ⚡AMPRak Half Marathon

The Rak Al Khaimah Half Marathon is the 'world's fastest half marathon' because if you take the top 10 fastest times recorded in RAK for men (and the same for women) and find the average (for each) and then do the same with the top ten fastest recorded times across all races (you can reference the IAAF for this), the...

more...Try this simple fartlek workout to improve your 5K

Winter is the perfect time to build a training base before any spring races. Focusing on improving your top-end speed with fartlek training can translate well to the 5 km distance and even trickle down to faster times for the half-marathon and marathon. The idea behind fartlek training is to help your body to adapt to various speeds and threshold zones.

Fartlek is a Swedish word meaning speed play. A fartlek session involves a continuous run while increasing and decreasing the speed and intensity for a period of time. Fartlek and interval training has many of the same benefits but the difference is the continuous running between reps.

The workout

10 to 15 reps of 90 seconds hard and one minute easy

Although 10 to 15 reps may seem like a lot on paper, the point of this workout isn’t the number of reps – it’s the time on your feet. To get the most out of it, spend the 90 seconds at your goal 5K pace, then the one-minute rest at a slow easy jog pace (for most runners this would be two to three minutes slower than your pace for the 90 seconds). 10 to 15 reps can simulate a 5K race. Your average pace on each rep will give an estimate of your current 5K time.

Runners have the option to make this workout easy or hard depending on their rest pace. The faster you jog your rest minute, the harder the workout will become, as your heart rate will remain high. My recommendation would be to start with a slow jog rest and increase your rest pace as you advance through the workout, depending on how your body feels.

If you are finding that the workout is too hard, even with the slow jog, break the workout in half: two sets of seven reps of 90 seconds and a minute jog (with three minutes jog rest between sets). The purpose of the workout is to maintain your goal 5K pace for its entirety If you are dropping off the pace after six or seven reps, don’t be afraid to add the additional rest to control your heart rate.

This workout is also helpful for beginners learning to run. Run the 90 seconds and transition to the one-minute jog into a one-minute walk, then repeat.

(01/21/2022) ⚡AMPby Marley Dickinson

2022 Dubai Marathon edition will not take place in January but hopefully in December due to COVID-19

The 2022 Dubai Marathon has been postponed, organizers told LetsRun.com last week. Typically staged in late January, the 2021 edition was cancelled due to COVID-19 and the 2022 edition will not take place in January either as local health and safety guidelines — including a temporary ban on flights from Kenya and Ethiopia — make it difficult to stage the race.

First held in 2000, Dubai began offering a $250,000 first-place prize in 2008 and a $1 million bonus for a world record. Though the world record bonus no longer exists and the prize money has been cut, the $100,000 reward for first place remains one of the biggest paydays in the sport.

As of now, Pace Events, the organizers and promoters of the Dubai Marathon, have set a tentative date of December 10 for the postponed 2022 edition. That would put the race in competition with the Abu Dhabi Marathon, a rival race begun in 2018 which staged its 2021 edition on November 26.

Pace Events provided the following statement to LetsRun.com on the 2022 Dubai Marathon:

On behalf of Pace Events FZ LLC, we trust you had a good new year and are looking forward to a brighter future for running events. As the organisers of the Dubai Marathon for 21 consecutive years since its first edition in 2000, Pace Events anticipates a time when we can all come together and have another World Athletics-sanctioned Marathon and mass participation event in the city of Dubai.