Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

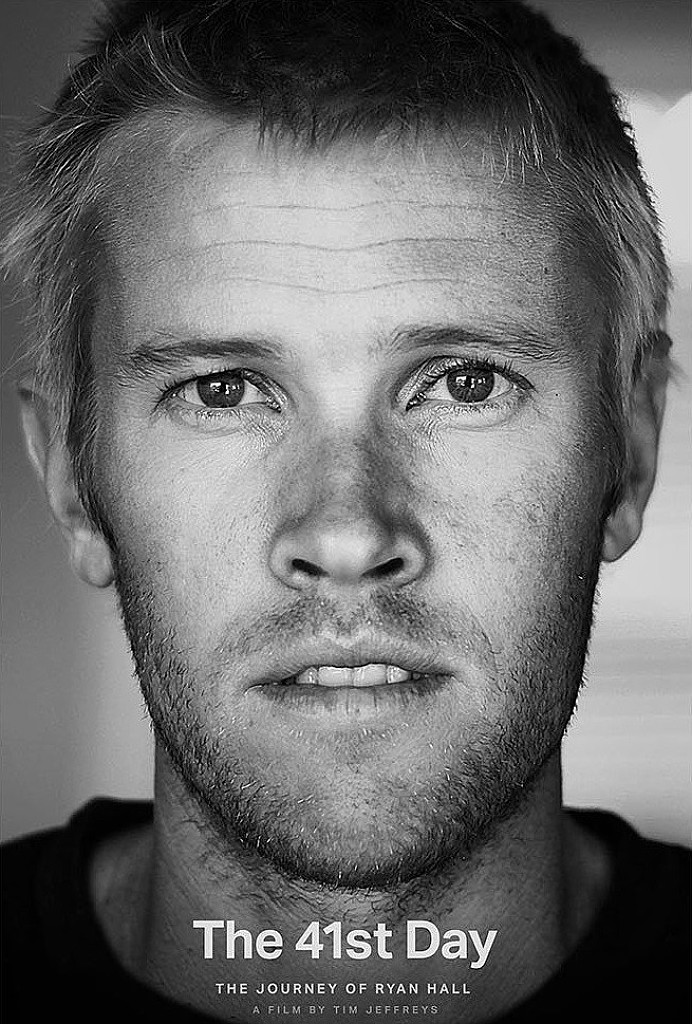

Articles tagged #Ryan Hall

Today's Running News

Conner Mantz’s Gritty Fourth-Place Finish at the 2025 Boston Marathon

In a performance that underscored his rising stature in American distance running, Conner Mantz delivered a personal best of 2:05:08 at the 2025 Boston Marathon, finishing fourth and narrowly missing a podium spot by just four seconds. This time stands as the second-fastest ever recorded by an American on the storied Boston course, trailing only Ryan Hall’s 2:04:58 from 2011.

A Race of Strategy and Resolve

Mantz, 28, positioned himself strategically within the lead pack for much of the race. However, at the 20-mile mark, Kenya’s John Korir executed a decisive move around Heartbreak Hill, opening a 20-second gap that would eventually extend to nearly a minute. Korir went on to win the race in 2:04:45, the second-fastest winning time in Boston Marathon history.

As Korir surged ahead, Mantz found himself in a fierce battle for the remaining podium spots with Tanzania’s Alphonce Simbu and Kenya’s Cybrian Kotut. The trio remained tightly grouped as they approached the final stretch on Boylston Street. Despite a valiant effort, Mantz was outkicked in the last 300 meters, finishing just behind Simbu and Kotut, who both clocked 2:05:04.

Reflections on a Career-Defining Race

After the race, Mantz reflected on the experience:

“I made my hard move and they responded as if I wasn’t there making a move. So it was a little bit humbling,” Mantz said. “Missing it and getting outkicked for the last 300 meters is a little bitter. It’s still probably the best race I’ve had.”

This performance marked a significant improvement over his previous personal best of 2:07:47, set at the 2023 Chicago Marathon, and his 11th-place finish at the 2023 Boston Marathon with a time of 2:10:25.

Building Momentum

Mantz’s Boston performance continues a series of impressive results. In January, he set a new American half-marathon record by finishing the Houston Half Marathon in 59:17, breaking Ryan Hall’s 18-year-old record.

His consistent excellence on the road has solidified his status as one of America’s premier long-distance runners.

Mantz’s achievements not only highlight his personal growth but also signal a resurgence in American distance running. As he continues to build on his successes, fans and fellow athletes alike will be watching closely to see how he performs in upcoming international competitions.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

A Day for the History Books: Korir and Lokedi Shine at the 2025 Boston Marathon

The 129th edition of the Boston Marathon, held Monday, April 21, 2025, delivered unforgettable drama and record-setting performances on the iconic route from Hopkinton to Boylston Street. Under near-perfect running conditions—mid-50s temperatures, low humidity, and a light tailwind—elite runners took full advantage, producing some of the fastest times in race history.

John Korir Claims His Crown and Continues a Family Legacy

Kenya’s John Korir won the men’s race in a sensational 2:04:45, the second-fastest time ever run on the Boston course. The younger brother of 2012 Boston champion Wesley Korir, John added another chapter to his family’s Boston legacy by not only conquering the challenging course but doing so in dominant fashion.

Despite a minor fall early in the race, Korir surged away from a deep international field after 20 miles, building a gap that no one could close. His finishing time was just over a minute shy of Geoffrey Mutai’s legendary 2:03:02 from 2011—the fastest time ever run in Boston but not eligible as a world record due to the course layout.

“I knew I was ready for something big,” Korir said post-race. “To follow in my brother’s footsteps and win Boston means everything.”

American hopes were high coming into the race, and Conner Mantz did not disappoint. Running a massive personal best of 2:05:08, he placed fourth overall and became the second-fastest American ever on the Boston course, behind only Ryan Hall’s 2:04:58 (set in 2011).

Sharon Lokedi Breaks the Tape—and the Record

The women’s race was equally historic. Sharon Lokedi, who won the 2022 New York City Marathon, delivered the performance of her life to win in 2:17:22, a new Boston Marathon course record, smashing the previous mark of 2:19:59 set by Buzunesh Deba in 2014.

Lokedi ran a smart, strategic race. She stayed tucked in a lead pack through the Newton Hills and then launched a powerful surge at mile 24, dropping two-time Boston champion Hellen Obiri and the rest of the field. Obiri finished second in a personal best 2:18:10, making it a Kenyan 1-2 sweep on the women’s podium.

“This course is tough, but I felt strong the whole way,” Lokedi said. “To run a course record here—it’s just unbelievable.”

Top 10 Elite Men – 2025 Boston Marathon

1. John Korir (Kenya) – 2:04:45

2. Alphonce Simbu (Tanzania) – 2:05:04

3. Cybrian Kotut (Kenya) – 2:05:04

4. Conner Mantz (USA) – 2:05:08

5. Muktar Edris (Ethiopia) – 2:05:59

6. Rory Linkletter (Canada) – 2:07:02

7. Clayton Young (USA) – 2:07:04

8. Tebello Ramakongoana (Lesotho) – 2:07:19

9. Daniel Mateiko (Kenya) – 2:07:52

10. Ryan Ford (USA) – 2:08:00

Top 10 Elite Women – 2025 Boston Marathon

1. Sharon Lokedi (Kenya) – 2:17:22 (Course Record)

2. Hellen Obiri (Kenya) – 2:17:41

3. Yalemzerf Yehualaw (Ethiopia) – 2:18:06

4. Irine Cheptai (Kenya) – 2:21:32

5. Amane Beriso (Ethiopia) – 2:21:58

6. Calli Thackery (Great Britain) – 2:22:38

7. Jess McClain (USA) – 2:22:43

8. Annie Frisbie (USA) – 2:23:21

9. Stacy Ndiwa (Kenya) – 2:23:29

10. Tsige Haileslase (Ethiopia) – 2:23:43

Notable American Performances

• Emma Bates finished 13th with a time of 2:25:10.

• Dakotah Popehn secured 16th place in 2:26:09.

• Des Linden completed her 28th and final professional marathon, finishing 17th in 2:26:19.

• Sara Hall placed 18th with a time of 2:26:32.

Looking Ahead

The 2025 Boston Marathon reaffirmed its place as one of the world’s premier races—not just for its history and prestige, but for its ability to showcase incredible athletic achievement. With deep American performances and Kenyan dominance at the front, it sets the stage for an exciting year.

For fans, runners, and historians, this year’s Boston will go down as one of the most memorable ever.

My Best Runs

Your front row seat to the world of running

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Boston Marathon

Among the nation’s oldest athletic clubs, the B.A.A. was established in 1887, and, in 1896, more than half of the U.S. Olympic Team at the first modern games was composed of B.A.A. club members. The Olympic Games provided the inspiration for the first Boston Marathon, which culminated the B.A.A. Games on April 19, 1897. John J. McDermott emerged from a...

more...Sara Hall Returns to Boston Marathon, Continuing a Legacy of Excellence

Sara Hall, one of America’s most accomplished marathoners, is set to compete in the 129th Boston Marathon on April 21, 2025. This marks her fourth appearance in Boston, where she aims to build upon her impressive track record.

Hall’s personal best in the marathon is 2:20:32, achieved at The Marathon Project in 2020, making her the fourth-fastest American woman in history at the distance. In 2024, she finished 15th overall and was the second American woman at the Boston Marathon with a time of 2:27:58. Later that year, she broke her own American masters record by running 2:23:45 at the Valencia Marathon .

Hall’s versatility is evident in her achievements across various distances. She set an American half marathon record of 1:07:15 in 2022 and has won 10 U.S. national titles, uniquely securikng championships in both the mile and the marathon. Her international accolades include a gold medal in the 3,000m steeplechase at the 2011 Pan American Games .

Beyond her athletic prowess, Hall is known for her commitment to philanthropy. She and her husband, Ryan Hall, a former U.S. Olympian and American record holder in the half marathon, co-founded the Hall Steps Foundation, which focuses on combating global poverty. In 2015, they adopted four sisters from Ethiopia, expanding their family and deepening their connection to the global community .

As Hall prepares for the 2025 Boston Marathon, she continues to inspire with her dedication, resilience, and contributions both on and off the course.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

The Global Sub-60 Chase: Why Breaking 60 Minutes in the Half Marathon Is the New Benchmark

In the world of distance running, certain time barriers carry iconic weight: the four-minute mile, the two-hour marathon, and now, perhaps more than ever before, the sub-60-minute half marathon.

Running 13.1 miles at an average pace of under 4:35 per mile (approximately 2:50 per kilometer) was once a feat reserved for only a handful of legends. Today, more than 100 men have accomplished the mark—transforming what was once historic into a new global benchmark. From the streets of Valencia to the avenues of Houston, the sub-60 chase has reshaped the competitive landscape.

At the heart of this movement is Uganda’s Jacob Kiplimo, arguably the most exciting half marathoner on the planet. In 2021, Kiplimo smashed the world record by clocking 57:31 in Lisbon, Portugal—a performance that combined raw power, impeccable pacing, and near-perfect weather. His fluid stride and ability to surge at will have made him the gold standard for half marathon excellence.

Kiplimo’s brilliance lies not just in his times, but in his consistency. He’s one of the few runners who can deliver near-world-record performances while battling the best in championship-style races, such as his victory at the 2020 World Half Marathon Championships in Gdynia, Poland.

So, what does it take to go sub-60? It’s more than just genetic talent. Athletes training at the Kenyan Athletics Training Academy (KATA) in Thika and at the KATA Retreat in Portugal are learning that going under an hour requires a perfect storm of speed, endurance, tactical racing, and recovery. Former 2:07 marathoner Jimmy Muindi, now coaching at KATA Portugal, emphasizes the importance of training specificity: “It’s not just about the miles—it’s about the right workouts, at the right time, and the right rest.”

Technology has also played its part. Super shoes, optimized pacing, and faster courses have contributed to faster times, but the core remains the same: the athlete. And sub-60 remains a sacred number—an invisible finish line that continues to pull the best out of the world’s elite.

American Runners Breaking the Sub-60 Barrier

For years, American distance running lagged behind East African dominance in the half marathon. However, significant breakthroughs have occurred over the past two decades:

• Ryan Hall made history in 2007 by becoming the first American to break the one-hour barrier, finishing the Houston Half Marathon in 59:43. This performance stood as the American record for 18 years.

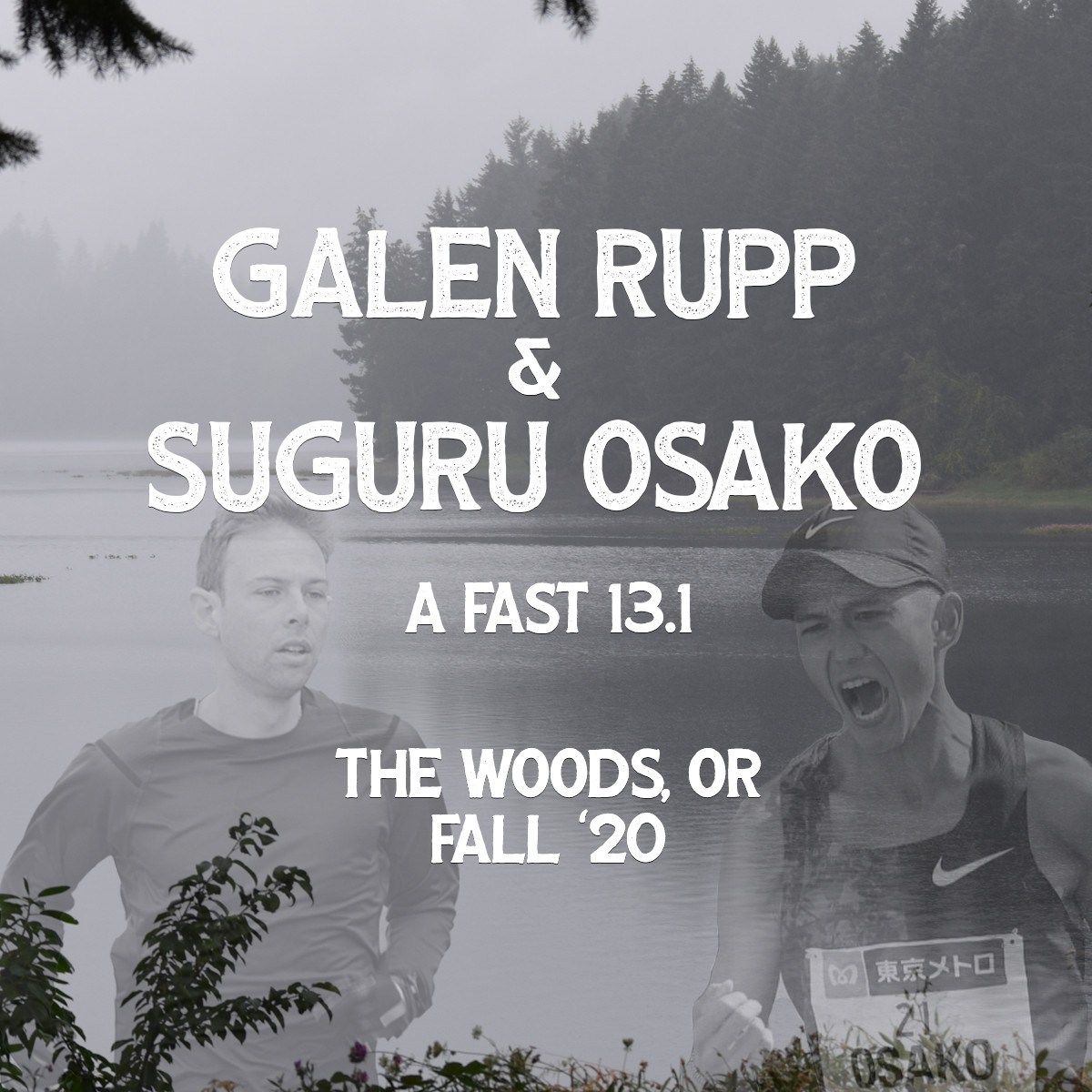

• Galen Rupp, a two-time Olympic medalist, joined the sub-60 club in 2018 with a time of 59:47 at the Roma-Ostia Half Marathon, showcasing his versatility across distances.

• Conner Mantz recently set a new American record by completing the Houston Half Marathon in 59:17, demonstrating the rising talent in U.S. distance running.

These achievements signify a new era for American distance runners, who are now competing at the highest levels on the global stage.

“The new super shoes have helped runners from at least 10 countries achieve a sub-60-minute half marathon,” says MBR editor Bob Anderson.

This surge in international performances underscores the evolving landscape of elite distance running, where advancements in technology and training are enabling athletes worldwide to reach new milestones.

With the 2025 racing calendar heating up, all eyes will be on the next generation of half marathoners. Who will be the next to join Kiplimo in the sub-58 club? And how long until sub-59 becomes the norm?

As the sport evolves, one thing is clear: the chase for sub-60 isn’t just about times—it’s about what’s possible.

by Bob Anderson with Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

More about Conner Mantz: From Utah Prodigy to American Record Holder

Conner Mantz's journey from a young running enthusiast in Utah to an American record holder is a testament to his unwavering dedication and exceptional talent. Born on December 8, 1996, in Logan, Utah, Mantz's early passion for running set the stage for a remarkable career in long-distance running.

Mantz's affinity for running became evident at a young age. At just 12, he completed his first half marathon, igniting a fervor for the sport. By 14, he impressively finished a half marathon in 1:11:24, maintaining an average pace of 5:26.8 minutes per mile. During his time at Sky View High School in Smithfield, Utah, Mantz distinguished himself as a three-time All-American at the Foot Locker Cross Country Championships. His prowess also earned him a spot on Team USA at the 2015 IAAF World Cross Country Championships in Guiyang, China, where he placed 29th in the junior race, leading the team to a commendable sixth-place finish.

Choosing to further his running career and education, Mantz committed to Brigham Young University (BYU), turning down offers from institutions like Princeton and Furman. Before starting at BYU, he took a two-year hiatus to serve as a missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Ghana. Upon his return in 2017, Mantz redshirted his first year, laying a solid foundation for his collegiate career. Under the guidance of coach Ed Eyestone, Mantz clinched back-to-back NCAA Division I Cross Country Championships titles in 2020 and 2021, solidifying his reputation as one of the nation's premier collegiate runners.

Transition to Professional Running

Turning professional in December 2021, Mantz signed with Nike and quickly made his mark. He won the USA Half Marathon Championships in Hardeeville, South Carolina, with a time of 1:00:55. The following year, he debuted in the marathon at the 2022 Chicago Marathon, finishing seventh with a time of 2:08:16. This performance was the second-fastest marathon debut by an American, just behind Leonard Korir's 2:07:56.

Olympic Pursuits and Notable Performances

In 2024, Mantz's career reached new heights. He won the U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials, securing his spot at the Paris 2024 Olympics. Despite facing a two-inch tear in his quad during preparations, Mantz showcased resilience, finishing eighth in the Olympic marathon. Post-Olympics, he continued to impress, placing sixth at the 2024 New York City Marathon.

Breaking the American Half Marathon Record

On January 19, 2025, at the Houston Half Marathon, Mantz etched his name into the record books. He completed the race in a staggering 59:17, breaking Ryan Hall's 18-year-old American record of 59:43 set in 2007. This achievement not only shattered the long-standing record but also made Mantz the first American in seven years to run a sub-60-minute half marathon.

Looking Ahead

Conner Mantz's trajectory in long-distance running is a blend of early passion, collegiate excellence, and professional triumphs. As he continues to push boundaries and set new standards, the running community eagerly anticipates his future endeavors, confident that Mantz will remain a formidable force on both national and international stages.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Thrilling Finish at the 2025 Chevron Houston Half Marathon: Conner Mantz Ties Event Record, Sets New American Standard

The 2025 Chevron Houston Half Marathon delivered an unforgettable race, featuring one of the closest finishes in the event’s history. In a jaw-dropping sprint to the finish line, Addisu Gobena of Ethiopia and Conner Mantz of the United States both crossed the tape at 59:17, sharing the event record in an electric photo finish.

For Mantz, this historic performance was doubly significant. The Utah native not only tied the event record but also shattered Ryan Hall’s longstanding American record of 59:43, set in 2007. Mantz’s 59:17 establishes a new national standard, cementing his place as one of the greatest American half-marathoners.

The men’s field showcased extraordinary depth, with four runners breaking the elusive 1-hour mark and an additional eight runners finishing under 61 minutes. The sheer quality of performances underscores Houston’s reputation as one of the premier half-marathon events in the world.

Men’s Results Overview

1. Addisu Gobena (Ethiopia) – 59:17

2. Conner Mantz (USA) – 59:17 (New American Record)

3. Gabriel Geay (Tanzania) – 59:18

4. Jemal Yimer (Ethiopia) – 59:20

5. Patrick Dever (Great Britain) – 1:00:11

Mantz’s record-breaking run wasn’t the only highlight for American fans. Hillary Bor, Wesley Kiptoo, Andrew Colley, and Alex Maier all posted sub-61-minute finishes, demonstrating the growing strength of U.S. distance running.

A Photo Finish for the Ages

The showdown between Gobena and Mantz captivated spectators. Both runners surged in the final meters, with Gobena just barely edging ahead in the official results. While Gobena claimed the win, Mantz’s breakthrough made headlines, showing that American distance running continues to rise to global prominence.

Conner Mantz’s Perspective

“This was a dream race for me,” Mantz said after the event. “I’ve always admired Ryan Hall’s record, and to not only break it but to do so in such a competitive field is incredibly special. Sharing the event record with Addisu Gobena makes it even more memorable.”

A Record-Setting Day

The 2025 Chevron Houston Half Marathon proved to be one for the history books. With its flat, fast course and deep international field, the event continues to attract world-class talent. Gobena and Mantz’s shared record and Mantz’s new American milestone will stand as highlights of this year’s race, reminding fans why Houston is synonymous with excellence in distance running.

Women’s Half Marathon:

Weini Kelati lowered her own American women’s half marathon record by completing the race in 1:06:09, a 16-second improvement from her previous record of 1:06:25 set at the same event last year. Kelati secured second place in the women’s field, finishing just four seconds behind Ethiopia’s Senayet Getachew, who won with a time of 1:06:05.

The favorable weather conditions in Houston contributed to these record-breaking performances, making the 2025 Houston Half Marathon a memorable event for American distance running.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Aramco Houston Half Marathon

The Chevron Houston Marathon provides runners with a one-of-a-kind experience in the vibrant and dynamic setting of America's fourth-largest city. Renowned for its fast, flat, and scenic single-loop course, the race has earned accolades as the "fastest winter marathon" and the "second fastest marathon overall," according to the Ultimate Guide to Marathons. It’s a perfect opportunity for both elite athletes...

more...Houston chases new American records elite fields include Yehaulaw and Kiptoo

The 2025 road racing year will open with an exciting chase for American records at the Aramco Houston Half Marathon and course records at the Chevron Houston Marathon on Sunday, January 19.

The Houston Marathon Committee announced the professional fields for both races today, featuring returning champions and all-time top performers.

The women’s half marathon field is led by the fifth fastest woman in history, Yalemzerf Yehaulaw of Ethiopia who will race in North America for the first time. Yehaulaw, 25, holds two of the top ten all-time half marathon performances including her personal best of 1:03:51 from Valencia in 2021. In 2024, Yehaulaw set a new personal best time in the marathon, winning the Amsterdam Marathon in 2:16:52, a course record.

“It has always been my ambition to race in the United States and now the opportunity has finally come,” said Yehaulaw, the 2022 TCS London Marathon winner. “Running an early race means I get a chance to focus fully on the half marathon to go for a fast time. I am eager to win.”

The Aramco Houston Half Marathon women’s race also features the follow-up half marathon for the American record holder Weini Kelati. Kelati set the record of 1:06:25 in her debut half marathon here last year. She has not raced the distance since, instead focusing on the 10,000m in which she represented the United States at the 2024 Paris Games.

“I’m really excited to come back to Houston and run my second half marathon,” said Kelati, who finished fourth here in 2024. “Last year was great and I hope this year’s race will be even better. My training has been going well and I know the competition will be very good.”

The women’s professional field features 15 women who have run faster than 1:10 in the half marathon. Other top contenders include last year’s third place finisher Buze Diriba of Ethiopia; the third fastest British half marathoner in history, Jessica Warner-Judd, and fellow Brit and 2024 Olympic marathoner, Calli Hauger-Thackery. Hauger-Thackery won the California International Marathon last month.

The men’s competition will see a rematch of last year’s thrilling Aramco Houston Half Marathon. Wesley Kiptoo of Kenya who has been runner-up here for the past two years will again face off against Jemal Yimer of Ethiopia. Yimer outsprinted Kiptoo in 2024, beating him by just one second.

“I can’t wait to return to Houston to try to defend my 2024 title,” said Yimer, who also won here in 2020. “It’s a special place for me to kick off my 2025 road season.”

The pair will be joined by Tanzania Olympian and former Boston Marathon runner-up Gabriel Gaey who has a personal best of 59:42 from his seventh place finish here in 2020.

The men’s race will also see an attempt to finally topple the American half marathon record of 59:43 set here by Ryan Hall in 2007. Leading the chase on the 18-year-old record will be 2024 Olympic marathoners Conner Mantz and Clayton Young. Mantz and Young, who finished eighth and ninth in Paris, train together in Provo, Utah. In November, they were the top two American finishers in the TCS New York City Marathon with Mantz breaking the American course record. This will be Young’s Houston debut. Mantz last ran here in 2023, finishing in sixth place.

“I want to race the Aramco Houston Half Marathon because there are other fast Americans going for the American Record,” said Mantz, who also set the American record in the 10 mile last October. “The opportunities to race in a field like this, on a fast and record-eligible course are rare.”

Mantz and Young will face competition for a spot in the record books from Diego Estrada, the ninth fastest American in history and 2015 Houston champion who had a career-best performance here last year when he finished fifth in 1:00:49. Joe Klecker, an Olympian in the 10,000m, will look to play a factor in his half marathon debut along with his training partner Morgan Pearson, a two-time Olympic silver medalist in the triathlon with a personal best of 1:01:08. Klecker comes to Houston with family history. His mother Janis Klecker is the 1992 Houston Marathon champion.

The Chevron Houston Marathon features the return of two-time champion Dominic Ondoro of Kenya. Ondoro, who won here in 2017 and 2023, will be part of a field that includes two men who have run under Zouhair Talbi’s course record of 2:06:39 set in 2024: Haimro Alame (Israel, 2:06:04) and Ande Filmon (Eritrea, 2:06:38). The field also includes last year’s third place finisher, Hendrik Pfeiffer of Germany. Pfeiffer led nearly 22 miles of last year’s race and finished with a personal best of 2:07:14.

“Houston was the best marathon race in my career so far. I have great memories of the fast course and the impressive city,” said Pfeiffer, whose wife Esther is in the women’s half marathon elite field. “I have already experienced how it feels to lead the race for more than 35 kilometers and I‘m hungry for more. I will definitely try to chase a fast time again.“

A new winner will be crowned in the Chevron Houston Marathon women’s race. After making her half marathon debut here in 2023, Anna Dibaba will return to Houston to run just the second marathon of her career. The sister of Ethiopian legends Tirunesh, Ejegayehu and Genzebe, Dibaba ran 2:23:56 in her debut in Amsterdam last October.

“As I race in more marathons I am sure that I will understand better what I am capable of,” said Dibaba who placed fourth in the 2023 Aramco Houston Half Marathon. “You have to respect the distance of the marathon and it is not enough to be in shape. You must know how to interpret each race, the various courses and conditions. I am looking forward to seeing what I am now able to do in my next race in Houston."

There are two Ethiopian women who have run faster than Dibaba entered in the race. Tsigie Hailesale who has run 2:22:10 and has marathon victories in Stockholm and Cape Town is the fastest and Sifan Melaku, also a past winner in Stockholm with a 2:23:49 personal best.

American Erika Kemp will line up for only her second career marathon in Houston. Kemp, a two-time U.S. champion will look to build on her experience from the Boston Marathon last spring.

“In 2023 I learned what it was like to be out there competing for over two hours,” said Kemp, who runs for Brooks, the footwear and apparel sponsor of the Houston Marathon Weekend of Events. “I’m hoping to utilize the course karma I’ve built up in Houston to have a great marathon.”

“We are excited to see so many top runners kick off their 2025 racing season with us in Houston,” said Wade Morehead, Executive Director of the Houston Marathon Committee. “We are expecting a historic day that will add to this event’s reputation as one of the best races in the world.”

More than USD 190,000 in prize money and bonuses will be awarded to the top finishers of the Chevron Houston Marathon and USD 70,000 plus time bonuses for the top finishers in the Aramco Houston Half Marathon. The races will be broadcast live on ABC13 and feature commentary from Olympic Marathoner and Boston Marathon champion Des Linden.

by AIMS

Login to leave a comment

Chevron Houston Marathon

The Chevron Houston Marathon offers participants a unique running experience in America's fourth largest city. The fast, flat, scenic single-loop course has been ranked as the "fastest winter marathon" and "second fastest marathon overall" by Ultimate Guide To Marathons. Additionally, with more than 200,000 spectators annually, the Chevron Houston Marathon enjoys tremendous crowd support. Established in 1972, the Houston Marathon...

more...Sara Hall Smashes Her Own American Masters Record

In her fourth marathon of 2024, Sara Hall finished 10th at the Valencia Marathon in Spain in 2:23:45. Hall, 41, shattered her own U.S. masters record, 2:26:06, which she set at the Olympic Marathon Trials in February.

The race was won by Megertu Alemu of Ethiopia in 2:16:49.

Hall averaged 5:29 per mile pace in Valencia. It was her best marathon since 2022, when she ran 2:22:10 at the World Championships in Eugene, Oregon, and placed fifth.

Hall has been frequent racer throughout her career, not needing much time to recover between races. Her entry into Valencia was a last-minute addition, after she raced in Chicago eight weeks earlier, and the race did not go according to plan. (Hall was 18th in 2:30:12.) She also ran Boston this year, finishing 15th in 2:27:58.

She posted to her Instagram account after the race.

“After a long stretch of not feeling like myself since Boston, it felt so good to have my normal fight out there,” Hall wrote, in part. “Applied the lessons I learned from Chicago, handled the very similar conditions much better. Chose to believe in myself even when my confidence had been rattled over and over. What a dream to do this four times this year.”

Hall elaborated in a text message to Runner’s World that she missed several bottles in Chicago—she fumbled a couple, and others she didn’t drink much out of—and became dehydrated in the humid conditions. “This time just was much more intentional to consume fluids even if I didn’t feel like I needed it,” she said.

She also increased her electrolytes and said she went out more conservatively than she would normally run and did at Chicago. Hall ran half spits that were almost even—1:11:40 and 1:12:05.

Hall’s PR is 2:20:32 from the Marathon Project in Chandler, Arizona, a one-time event set up for elite runners during the pandemic. That PR puts her fifth on the U.S. all-time list, behind Emily Sisson, Keira D’Amato, Betsy Saina, and Deena Kastor.

Her career is notable for its duration. Hall has appeared in every Olympic Trials since 2004, either on the track or in the marathon, or both. She is coached by her husband, Ryan Hall, who is third on the U.S. all-time list for men’s marathoners.

Hall was not the only record setter in Valencia. Roberta Groner, 46, who represented the U.S. at the 2019 world championships in Doha, Qatar, where she finished sixth, ran 2:29:32, setting an American record for the 45–49 age group.

Groner’s record should be safe for at least the next three years—or until Hall turns 45 in April 2028.

by Sarah Lorge Butler

Login to leave a comment

VALENCIA TRINIDAD ALFONSO

The Trinidad Alfonso EDP Valencia Marathon is held annually in the historic city of Valencia which, with its entirely flat circuit and perfect November temperature, averaging between 12-17 degrees, represents the ideal setting for hosting such a long-distance sporting challenge. This, coupled with the most incomparable of settings, makes the Valencia Marathon, Valencia, one of the most important events in...

more...The Evolution of Marathon Running: A Kenyan Perspective

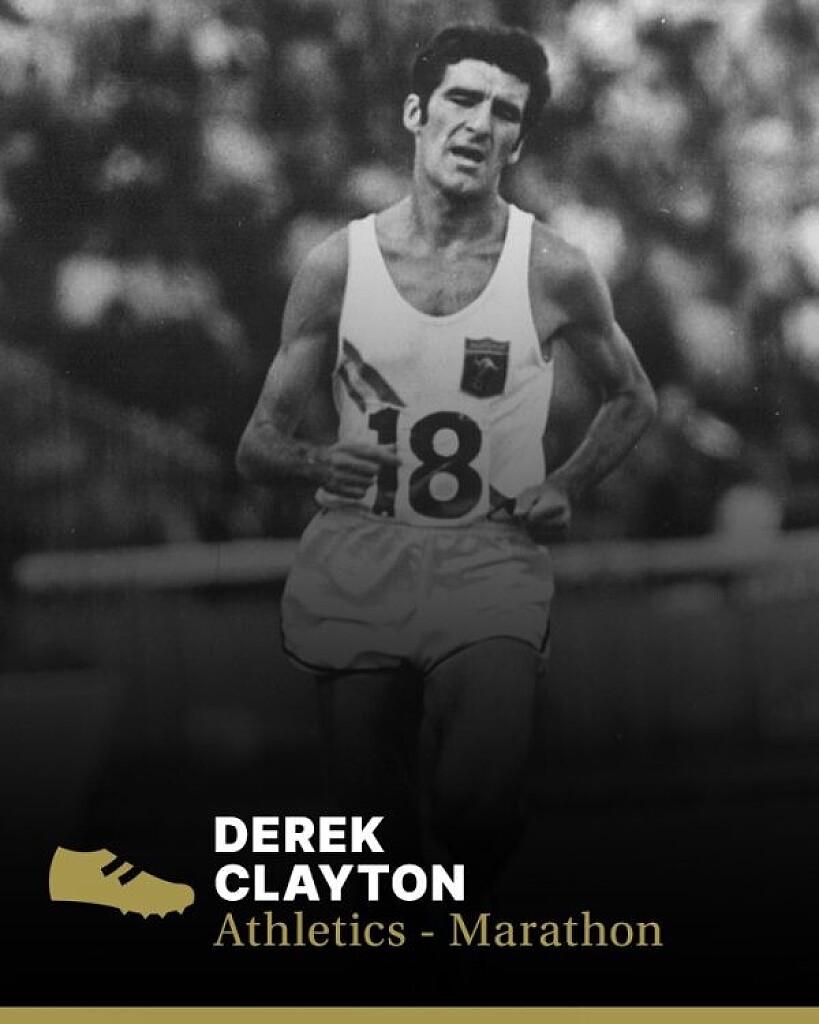

I can still vividly remember when 2:08:32 in the marathon seemed like an unbreakable barrier. Derek Clayton of Australia set this world record back in 1969 at the Antwerp Marathon—a time so remarkable that it stood for nearly 12 years. Now, hundreds of runners have far surpassed that mark. Today, running a sub-2:05 marathon has become almost routine, particularly for athletes from Africa.

On the women’s side, the achievements are just as groundbreaking. Ruth Chepngetich of Kenya recently made history at the 2024 Chicago Marathon by breaking the 2:10 barrier, finishing in a stunning 2:09:56. While this remarkable time is still awaiting ratification, it is set to redefine the boundaries of women’s marathon running. This performance follows the previous world record of 2:11:53, set by Tigst Assefa of Ethiopia at the 2023 Berlin Marathon. These times show just how far women’s marathon performances have progressed in recent years.

While advancements like “magic” shoes have undoubtedly played a role in these extraordinary performances, it’s important to note that better pacing by other professional runners, now a standard practice, has also made a significant difference. These pacesetters help keep athletes on target through much of the race, ensuring consistency and reducing mental strain. However, the story of record-breaking runs runs much deeper than technology and pacing strategies.

In Kenya alone, there are at least 80,000 distance runners who dream of nothing else but becoming professional athletes. For them, running isn’t just a passion—it’s a path to success and stability.

At the Kenyan Athletics Training Academy (KATA), the training camp I established in Thika, Kenya, we house, feed, and train aspiring athletes. I Each week, I receive messages from 10 or more runners hoping to join our program. For these athletes, running is not a hobby or a pastime. It’s a career aspiration, with the ultimate goal of winning races and securing prize money. They love running, but make no mistake—their drive is fueled by the potential to achieve financial security and support their families.

Contrast this with the United States, where very few runners train with the sole focus of becoming professional athletes. Instead, many children grow up dreaming of careers in sports like baseball, basketball, football, or, more recently, soccer. The talent pool for these sports is massive, and from this base, the superstars emerge.

That said, American marathoners have delivered incredible performances. Ryan Hall’s 2:04:58 at the 2011 Boston Marathon remains a monumental achievement, showcasing what U.S. athletes are capable of on a favorable course. On the women’s side, runners like Keira D’Amato (2:19:12) and Emily Sisson (2:18:29, an American record) are setting new benchmarks, proving that the U.S. can compete at the highest levels.

In the U.S., running is often a lifestyle choice rather than a career ambition. Recreational and “fun” runners dominate the scene, which has its benefits—contributing to a higher average life expectancy (76 years in the U.S. compared to 63 in Kenya). In Kenya, it’s rare to see runners over 40 years old out training. The focus there is on younger athletes whose primary goal is to make a living through running.

For many in Kenya, running is the equivalent of pursuing a high-paying job in other fields. This mentality dates back to pioneers like Kip Keino, who opened the door for countless Kenyan athletes to achieve global success. His legacy inspired generations, and today, Kenyan runners—both men and women—continue to push the limits of human potential.

As marathon times keep dropping and prize money continues to grow, I believe we’ll see even faster performances from both men and women—especially in Africa, where running is deeply ingrained as a pathway to opportunity.

by Bob Anderson

Login to leave a comment

Joe Klecker Plans His Half Marathon Debut

In a live recording of The CITIUS MAG Podcast in New York City, U.S. Olympian Joe Klecker confirmed that he is training for his half marathon debut in early 2025. He did not specify which race but signs point toward the Houston Half Marathon on Jan. 19th.

“We’re kind of on this journey to the marathon,” Klecker said on the Citizens Bank Stage at the 2024 TCS New York City Marathon Expo. “The next logical step is a half marathon. That will be in the new year. We don’t know exactly where yet but we want to go attack a half marathon. That’s what all the training is focused on and that’s why it’s been so fun. Not that the training is easy but it’s the training that comes the most naturally to me.”

Klecker owns personal bests of 12:54.99 for 5000m and 27:07.57 for 10,000m. In his lone outdoor track race of 2024, he ran 27:09.29 at Sound Running’s The Ten in March and missed the Olympic qualifying standard of 27:00.00.

His training style and genes (his mother Janis competed at the 1992 Summer Olympics in the marathon and won two U.S. marathon national championships in her career; and his father Barney previously held the U.S. 50-mile ultramarathon record) have always linked Klecker to great marathoning potential. For this year’s TCS New York City Marathon, the New York Road Runners had Klecker riding in the men’s lead truck so he could get a front-row glimpse at the race and the course, if he chooses to make his debut there or race in the near future.

The Comeback From Injury

In late May, Klecker announced he would not be able to run at the U.S. Olympic Track and Field Trials in June due to his recovery from a torn adductor earlier in the season, which ended his hopes of qualifying for a second U.S. Olympic team. He spent much of April cross training and running on the Boost microgravity treadmill at a lower percentage of his body weight.

“The process of coming back has been so smooth,” Klecker says. “A lot of that is just because it’s been all at the pace of my health. I haven’t been thinking like, ‘Oh I need to be at this level of fitness in two weeks to be on track for my goals.’ If my body is ready to go, we’re going to keep progressing. If it’s not ready to go, we’re going to pull back a little bit. That approach is what helped me get through this injury.”

One More Track Season

Klecker is not fully prepared to bid adieu to the track. He plans to chase the qualifying standard for the 10,000 meters and attempt to qualify for the 2025 World Championships in Tokyo. In 2022, after World Athletics announced Tokyo as the 2025 host city, he told coach Dathan Ritzenhein that he wanted the opportunity to race at Japan National Stadium with full crowds.

“I’m so happy with what I’ve done on the track that if I can make one more team, I’ll be so happy,” Klecker says. “Doing four more years of this training, I don’t know if I can stay healthy to be at the level I want to be. One more team on the track would just be like a dream.”

Klecker is also considering doubling up with global championships and could look to qualify for the 2025 World Road Running Championships, which will be held Sept. 26th to 28th in San Diego. To make the team, Klecker would have to race at the Atlanta Half Marathon on Sunday, March 2nd, which also serves as the U.S. Half Marathon Championships. The top three men and women will qualify for Worlds. One spot on Team USA will be offered via World Ranking.

Sound Running’s The Ten, one of the few fast opportunities to chase the 10,000m qualifying standard on the track, will be held on March 29th in San Juan Capistrano.

Thoughts on Ryan Hall’s American Record

The American record in the half marathon remains Ryan Hall’s 59:43 set in Houston on Jan. 14th, 2007. Two-time Olympic medalist Galen Rupp (59:47 at the 2018 Prague Half) and two-time U.S. Olympian Leonard Korir (59:52 at the 2017 New Dehli Half) are the only other Americans to break 60 minutes.

In the last three years, only Biya Simbassa (60:37 at the 2022 Valencia Half), Kirubel Erassa (60:44 at the 2022 Houston Half), Diego Estrada (60:49 at the 2024 Houston Half) and Conner Mantz (60:55 at the 2021 USATF Half Marathon Championships) have even dipped under 61 minutes.

On a global scale, Nineteen of the top 20 times half marathon performances in history have come since the pandemic. They have all been run by athletes from Kenyan, Uganda, and Ethiopia, who have gone to races in Valencia (Spain), Lisbon (Portugal), Ras Al Khaimah (UAE), or Copenhagen (Denmark), and the top Americans tend to pass on those races due to a lack of appearance fees or a stronger focus on domestic fall marathons.

Houston in January may be the fastest opportunity for a half marathon outside of the track season, which can run from March to September for 10,000m specialists.

“I think the record has stood for so long because it is such a fast record but we’re seeing these times drop like crazy,” Klecker says. “I think it’s a matter of time before it goes. Dathan (Ritzenhein) has run 60:00 so he has a pretty good barometer of what it takes to be in that fitness. Listening to him has been really good to let me know if that’s a realistic possibility and I think it is. That’s a goal of mine. I’m not there right now but I’m not racing a half marathon until the new year. I think we can get there to attempt it. A lot has to go right to get a record like that but just the idea of going for it is so motivating in training.”

His teammate, training partner, and Olympic marathon bronze medalist Hellen Obiri has full confidence in Klecker’s potential.

“He has been so amazing for training,” Obiri said in the days leading up to her runner-up finish at the New York City Marathon. “I think he can do the American record.”

by Chris Chavez

Login to leave a comment

Aramco Houston Half Marathon

The Chevron Houston Marathon provides runners with a one-of-a-kind experience in the vibrant and dynamic setting of America's fourth-largest city. Renowned for its fast, flat, and scenic single-loop course, the race has earned accolades as the "fastest winter marathon" and the "second fastest marathon overall," according to the Ultimate Guide to Marathons. It’s a perfect opportunity for both elite athletes...

more...Rory Linkletter adjusts to new coach ahead of TCS New York City Marathon

Canadian marathoner Rory Linkletter is preparing for the 2024 TCS New York City Marathon on Nov. 3 with a new coach and a renewed focus. After his previous coach, Ryan Hall, decided to step away from coaching following the Paris 2024 Olympics, Linkletter was forced to seek new guidance with less than 10 weeks to go until the race.

For Linkletter, his Paris Olympic marathon was a mix of pride and disappointment. He was proud to represent the red and white at an event he had always dreamed about competing at, but he felt his race was underwhelming. “I feel like I didn’t show my best,” Linkletter said on his 47th-place finish (2:13:09).

Linkletter told Canadian Running his preparation for Paris centred heavily on mastering the challenging course and hills: “I felt like I needed to get strong and run hills, but at the end of the day, it’s always the fittest man who wins,” he says. “I got too far away from speed and power.”

He took a week off after Paris and then dove back into training, focusing on his next challenge–the 2024 New York City Marathon. During his time off, Linkletter was taken by surprise when Hall announced he would be stepping back from coaching. “I was shocked. It was all so sudden,” Linkletter admits. “If you knew Ryan, you wouldn’t be surprised, but I didn’t expect it to happen so soon.”

New beginnings

Balancing the post-Olympic blues with the sudden coaching transition wasn’t easy, but Linkletter says he’s the most motivated to train when he’s disappointed.

The 2:08:01 marathoner initially created his own training plan for NYC, and reached out to a few people he trusted for feedback. One of those was Jon Green, coach of U.S. Olympic marathon bronze medallist Molly Seidel. “We met up, had a conversation, and he said he’d be happy to help me get to NYC,” Linkletter says. “By the time we met again, he had mapped out a plan for me. I liked what he had.”

Green is someone Canada’s second fastest marathoner has long respected, going back to their days racing against each other in the NCAA—Linkletter competing for Brigham Young University (BYU) and Green for Georgetown. Now, as a coach-athlete duo, they’re working to fine-tune Linkletter’s strengths for the NYC Marathon in his home of Flagstaff, Ariz.

Moving forward

Training in Flagstaff has become a constant for Linkletter. He’s found a home in the high-altitude environment, which is known for its ideal training conditions. “I love it here,” he says. “It’s one of the best, if not the best, places to train.” With the NYC Marathon on the horizon, Linkletter is content in Flagstaff, but remains open to exploring options that will best prepare him for the future. “Paris was awesome, but I want to be there again in L.A. 2028 and be the best version of myself,” he says.

By then, Linkletter will be 31 years old—what he believes will be his prime—and he’s determined to make every year count as he builds toward the goal.

by Marley Dickinson

Login to leave a comment

TCS New York City Marathon

The first New York City Marathon, organized in 1970 by Fred Lebow and Vince Chiappetta, was held entirely in Central Park. Of 127 entrants, only 55 men finished; the sole female entrant dropped out due to illness. Winners were given inexpensive wristwatches and recycled baseball and bowling trophies. The entry fee was $1 and the total event budget...

more...What the elites eat: Marathon Edition

Curious about what elite marathoners eat to fuel their peak performance? From carb-loaded pre-race meals to post-race burger feasts, here’s an inside look at what the elites eat before, during, and after a marathon.

As runners and human beings, we’re naturally curious, slightly nosy people. With information instantly available with the twitch of a finger across our iPhone screens, this curiosity has never been easier to satisfy. Plus, many of our favorite runners are more transparent than ever about their training blocks, pulling back the blinds through social media to show what it takes to be the best. Which is why we’re ever-fascinated by the race-related nutrition strategy of elite runners, who often perform at superhero-like levels.

We asked a few elite marathoners what they eat surrounding race day—pre-race dinner, pre-race breakfast, and post-race celebration—so you don’t have to.

Note: One sentiment echoed among all of the athletes interviewed was that their diets are personal and have gone through lots of trial-and-error to be finessed to their specifications. No lifestyle should be replicated exactly.

35, Boulder, Colorado

About him: First American and ninth overall finisher in the 2019 Chicago Marathon (2:10:36). Placed second at the 2020 U.S. Olympic Trials Marathon (2:10:02); Finished 28th in Tokyo Olympics marathon (2:16:26). After a second round of double Haglund’s surgery in 2022, he’s back in top form and running the 2024 New York City Marathon on November 3.

The night(s) before a race:

“I start thinking about meals two nights out, and I go carb-heavy on both. For the first night, I like to have Thai food, usually a noodle dish, and a side of rice. The only thing I’ll really avoid is spice since I’ve had issues from it a couple times. The night before, I do pasta, usually a marinara (that’s what a lot of races provide for the elite athletes), but a good pesto sauce works well, too. I mostly stay away from the creamy sauces. I don’t like to get too much more specific—you never know exactly what’s going to be available, so I try not to make particular foods part of my routine.”

Race morning:

“Race mornings I’ll get up at least three hours before (I prefer four, but with 7 to 8 A.M. starts, that becomes a little counter-productive), I’ll go for a short walk with some skipping or something, just to get the body moving. My first choice for breakfast is oatmeal with peanut butter, honey, and a little fruit mixed in. And at least one, usually two cups of coffee. It’s not something to avoid, but I recommend making sure that you have more than just simple carbs (cereal, muffin, etc), I find that if there isn’t at least some protein, I start getting that ‘empty’ feeling during my warmup, and if that mixes with the adrenaline, I feel real queasy. If I’m taking gels, I take one on the start line, maybe five minutes before. I also like Generation UCAN, which I’ll sip as I’m going through my drills, maybe half an hour out.”

During the race:

“I like to get my calories from gels and have just electrolytes in my bottles. Most major marathons provide drink stations every 5K, and I’ll drink about 8-10 oz of SOS per bottle (there can be splashing, and you never get it all out). I’ll take Roctane gels before every other drink station (every 30 minutes or so).”

Post-race meal:

“Most races I want a hash—lots of potatoes with some eggs, bacon, cheese, and veggies all mixed up, but after marathons my stomach takes a while to settle down, so I’m more in a lunch mood. So my go-to post-race meal is a big bistro bacon cheeseburger, ideally with an onion ring and barbecue sauce, side of fries, and a beer. I mostly stay away from fried foods during a build up, but I always take at least a week off after a marathon and at this point, that beer and burger is almost a Pavlovian ‘vacation time’ signal for my whole body.”

41, Flagstaff, Arizona

About her: She’s the fourth-fastest American woman in history based on her personal best (2:20:2) at the 2020 Marathon Project; Second-fastest American female half-marathon runner and former American record-holder (1:07:15). Most recently, she was 18th overall and the women’s master champion in the 2024 Chicago Marathon (2:30:12).

The night(s) before a race:

“Rice with chicken. I skip the veggies to not risk having to make a bathroom stop in the race.”

Pre-race breakfast:

“Two scoops of UCAN energy powder with whey protein, and a little bit of almond butter.” Bonus, Hall credits her husband, Ryan Hall, as being the best coffee maker, brewing pour-over, medium roast coffee blended with butter.

During the race:

Ketone-IQ—peach flavored.

Post-race meal:

“My favorite post-meal race is Thai food. I’m usually eating a lot of boring food before the race, so I want something spicy and more flavorful after.”

Bonus—Lunch during training blocks:

“Two scoops of UCAN powder, two pieces of gluten-free bread with Kerrygold Butter.”

36, Boulder, Colorado

About her: Won the 2019 Grandma’s Marathon and finished ninth in the 2020 U.S. Women’s Olympic Trials Marathon in 2:30:39. She was the top American finisher in the Boston Marathon in 2021 (fifth, 2:27:12, ) and 2022 (10th, 2:25:57). In January, she placed ninth in the Houston Half Marathon in a new personal best of 1:08:52.

The night(s) before a race:

“I always have the same thing. Basically, a couple cups of white rice and a chicken breast is where I tend to fall. White rice is going to fuel the most carbs per serving. I used to mix up potatoes and white rice, but for me, I digest white rice well, I feel better, it’s easy to find, simple, and works well.

I don’t care about spices—and I’m usually not making it myself if I’m not at home. Typically, before races, there’s a pre-race dinner, and chicken is an option. I wouldn’t do any cream-based sauces. If it tastes good, great. If it doesn’t, great. I don’t care.”

Pre-race breakfast:

“Typically it’s oatmeal with a tablespoon of peanut butter, a banana, and maybe honey. I’m not 100 percent satisfied with my pre-race meal, because sometimes it can feel a bit heavy in my stomach, because oatmeal does have some fiber. So I try to play around with things. Sometimes I’ll do a couple pieces of toast with a banana and peanut butter. I can switch between those two. Try to get 500-600 calories in, mostly from carbs, two-three hours before the race. Plus, I drink coffee with half-and-half.

Post-race meal:

“Immediately after the race, I honestly will grab whatever is available. Typically, after a race, we’ll be shuttled to a post-race holding area where you’re waiting, so there are usually refreshments there. I’ll slam Gatorade—anything with sugar and electrolytes. Maybe there’s my own bottle with Skratch in it. Banana, a protein shake. I’m pretty open, as long as it’s immediate.

And as far as later, it completely depends. I’m trying to do a better job at this—especially after a major marathon—but it kind of takes a while. You might get drug-tested, then shuttled back to your hotel, shower, then six hours later you’re like, ‘I need to eat.’ If it’s a marathon, I love a big burger with fries—the classic stuff, lettuce, tomato, onion, and tons of ketchup and mayo. That’s something my body would crave. Fries are my favorite food ever that I don’t typically eat during a marathon cycle.”

35, Louisville, Colorado

About her: Finished sixth in the 2017 London Marathon (2:25:38), seventh in the 2019 New York City Marathon (2:28:23), eighth in the 2019 Chicago Marathon (2:29:06), eighth in the 2021 New York City Marathon (2:27:00). Most recently, an Achilles injury forced her to pull out of the 2024 Chicago Marathon days before the race.

The night(s) before a race:

“I do 72-hours of carb-loading. So, obviously, in the build to that, carbs are key. Three days out from the race is when I start it. It is always the same. The night before, I have pasta with marinara sauce, and I don’t do a lot of protein with that. I do love angel hair, that’s my go-to. I also like rigatoni. Plus, I’ll have some type of bread and salad.”

Pre-race breakfast:

“The morning of, I always do a plain bagel and peanut butter with a banana. I’ve done that since high school. And I do an Americano with two shots. I eat that threeish hours out from the race.

During the race:

“I’ll take my first gel 15 minutes before the start of the race. I’ve been all over the place with what I take, but right now, Neversecond. Big fan of their Cola C30 gels. They worked wonders for me during this build. I had some stomach issues earlier in the build with long runs and couldn’t quite figure out what was going on, so I switched up my nutrition during, so never second has been a godsend.”

Post-race meal:

“After the race, it’s hard because usually my stomach is a mess. Not only did you just run really hard for two and a half hours, but you’re taking all this fuel during, so I have a really hard time eating solids immediately after the race. My choice if I can get it is soda. I’m not a big soda drinker, but after a marathon, all I want is a Coke, Sprite, or Ginger Ale. I’m always really thirsty when I finish.

Then later when I feel like eating, I always do a burger (stacked with all the fixings—sometimes adding bacon) and sweet potato fries with ranch. I never opt out of Ranch. Anything I can dip ranch in is a plus for me. And I order a Blue Moon. I’m not a beer drinker, but that’s what I want after a marathon.”

by Mallory Arnold

Login to leave a comment

NCAA school faces backlash over 28-year-old Kenyan freshman

This time of year, many 18 and 19-year-olds are preparing for their first year of college or university. Kenyan runner Solomon Kipchoge will be experiencing the same firsts as a 28-year-old freshman at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas. Kipchoge has a half marathon best faster than the American record and will be 10 years older than the majority of the incoming NCAA recruiting class for the 2024/2025 season, which has caused a stir among athletes.

The 28-year-old holds a half-marathon personal best of 59:37, which was set at the Semi-Marathon de Lille 2023 in France (a World Athletics Elite Label road race). His personal best is faster than any time ever run by an American over the half-marathon distance. (The American record of 59:43 is held by Ryan Hall.)

The 28-year-old holds a half-marathon personal best of 59:37, which was set at the Semi-Marathon de Lille 2023 in France (a World Athletics Elite Label road race). His personal best is faster than any time ever run by an American over the half-marathon distance. (The American record of 59:43 is held by Ryan Hall.)

Although the NCAA has no restrictions on age, eligibility rules grant athletes a period of five years to complete four seasons of their sport. This means that athletes entering university at age 18 (the standard age for graduating high school) will be finished competing at age 23. Athletes who postpone the start of their post-secondary education will still be eligible at an older age–but beginning at age 28 seems like quite a stretch; the Kenyan will be competing against a field with athletes 10 years younger than himself.

Many users on Instagram are unsupportive of Kipchoge’s (very) late start to his degree in agricultural education. “It’s awesome that these guys are getting this opportunity and they should take advantage of it…With that being said, the NCAA regulations are objectively extremely flawed, and there is no reason nearly pro-caliber runners should be competing against teenagers 10+ years younger than them who are straight out of high school,” one comment reads.

Some international athletes still choose to compete in the NCAA (despite financial barriers) to take advantage of opportunities for development–but the Kenyan is already one of the fastest half-marathon runners in the world. In May, Kipchoge took fourth in an elite field at the Rimi Riga Half-Marathon, clocking 1:02:15. Already a world-class athlete, Kipchoge is unlikely to find development opportunities within NCAA-level competition.

by Running Magazine

Login to leave a comment

Defending champions return to Bix

Kellyn Taylor and Biya Simbassa each ran the Quad-City Times Bix 7 for the first time last year.

They clearly loved the course, the atmosphere and just about everything about the annual race through the streets of Davenport.

Both Taylor and Simbassa held off late challenges from other runners, both ran the sixth best Bix 7 times ever by a U.S. athlete of their gender and both plan to return to defend their championships when the race is held for the 50th time on July 27.

It marks the first time in 12 years that both the men’s and women’s champions are returning to defend their Bix titles.

Simbassa admitted he wasn’t really sure how he felt about the Bix 7 course last year when he first saw the endless array of ups and downs in the course. But after holding off Olympian Clayton Young to win, he liked it.

“I mean, now I do,’’ he said after his victory. “It’s a course that’s all about strength and I train for this."

Taylor went through a similar transformation.

“When I saw the course, I was like, ‘Oh, no. What did I get myself into?’ ” she said. “That’s a super substantial hill right at the beginning and then it rolls all the way through. It’s certainly not easy by any means. I think that works to my favor since I’m more of a strength runner.”

Taylor appreciated more than just the hills.

“The crowds were amazing,” she said. “It’s not what I expected at all — the streets were completely lined, and a race that isn’t a huge marathon, I don’t feel like you see that that often. The crowds were incredible.”

Taylor and Simbassa will be bidding to repeat as Bix 7 champions, something that has been done only seven times in the race’s history, four times by men, three times by women.

Both runners failed to land berths on the U.S. Olympic team, which would have precluded a return to Bix, but they’ve still used their 2023 victories as a springboard to additional success.

Taylor briefly led the New York City Marathon last November before placing eighth, making her the top American finisher in the race. It was the third time she has been in the top eight at New York.

The Wisconsin native, who will turn 38 a few days before the Bix 7, then focused her attention on making the U.S. Olympic team and made a respectable showing in the trials in the marathon, finishing 15th, and the 10,000 meters, placing sixth.

Simbassa, a 31-year-old native of Ethiopia who now lives in Flagstaff, Arizona, attempted to earn an Olympic spot in the marathon but placed 11th in the trials.

However, he has followed that with an ambitious schedule on the U.S. road racing circuit, recording top-five finishes in the Bolder Boulder 10k (5th), Cherry Blossom 10-miler (5th), Gate River 15k (4th), Amway River Bank 25k (3rd) and Houston Half-marathon (4th).

Also included in the field are four former Olympians and nine other runners who have placed in the top 10 at the Bix 7 in the past. Elite athlete coordinator John Tope said even more top runners could be added between now and race day.

Among the top men’s entries are two former Iowa State University standouts.

Wesley Kiptoo of Kenya was the 2021 NCAA indoor 5,000-meter champion and a seven-time All-American for the Cyclones. He was seventh in the Bix 7 two years ago and won the Cherry Blossom 10-miler earlier this year.

Hillary Bor, a Kenya native who is now an American citizen, also attended Iowa State before representing the U.S. in the 3,000-meter steeplechase at the Olympics in both 2016 and 2021. He also is the U.S. record-holder in the 10-mile run.

Other former Olympians in the field are Morocco’s Mohamed El Aaraby and Americans Jake Riley and Shadrack Kipchirchir. Riley and Araby both competed in the marathon in Tokyo in 2021 and Kipchirchir ran the 10,000 meters in 2016.

Riley also is a Bix 7 veteran along with Kenya’s Reuben Mosip and Americans Frank Lara, Andrew Colley and Isai Rodriguez. Lara was second in the Bix 7 in 2021 and eighth a year ago.

Rounding out the men’s field are Raymond Magut of Kenya; Tsegay Tuemay and Tesfu Tewelde of Eritrea; and Americans Nathan Martin, Ryan Ford, JP Trojan, Merga Gemeda and Titus Winders.

The most recognizable name in the women’s field is 41-year-old Sara Hall, the wife of two-time Olympian, U.S. half-marathon record-holder and 2010 Bix champion Ryan Hall. Sara Hall was fifth in the U.S. Olympic marathon trials earlier this year and has two strong Bix 7 efforts on her resume, placing second in 2014 and third in 2017.

She and Taylor will be challenged by three up-and-coming runners from Kenya — Emmaculate Anyango Achol, Grace Loibach Nawowuna and Sarah Naibei. Achol has run the second fastest women’s 10k ever (28:57) and Naibei won the Lilac Bloomsday 12k in May.

Also in the field are Bix 7 veterans Kassie Parker, Jessa Hanson, Carrie Verdon and Tristin Van Ord along with Americans Annmarie Tuxbury and Stephanie Sherman, Ethiopia’s Mahlet Mulugeta and Kenya's Veronicah Wanjiru.

The elite field also includes four legendary runners who have helped build the Bix 7 into the international event that it is. Two-time champion Bill Rodgers, who has run the Bix 7 43 times, will be joined by four-time women’s champion and 1984 Olympic gold medalist Joan Samuelson, two-time Olympic medalist Frank Shorter and Meb Keflezighi, who has two Bix titles and an Olympic silver medal on his resume.

by Don Doxsie

Login to leave a comment

Bix 7 miler

This race attracts the greatest long distance runners in the world competing to win thousands of dollars in prize money. It is said to be the highest purse of any non-marathon race. Tremendous spectator support, entertainment and post party. Come and try to conquer this challenging course along with over 15,000 other participants, as you "Run With The Best." In...

more...TWENTY-ONE YEARS AGO, HE WAS INCARCERATED FOR LIFE. LAST YEAR, HE RAN THE NYC MARATHON A RADICALLY CHANGED MAN.

RAHSAAN ROUNDED THOMAS A CORNER. Gravel underfoot gave way to pavement, then dirt. Another left turn, and then another. In the distance, beyond the 30-foot wall and barbed wire separating him from the world outside, he could see the 2,500-foot peak of Mount Tamalpais. He completed the 400-meter loop another 11 times for an easy three miles.

Rahsaan wasn’t the only runner circling the Yard that evening in the fall of 2017. Some 30 people had joined San Quentin State Prison’s 1,000 Mile Club by the time Rahsaan arrived at the prison four years prior, and the group had only grown since. Starting in January each year, the club held weekly workouts and monthly races in the Yard, culminating with the San Quentin Marathon—105 laps—in November. The 2017 running would be Rahsaan’s first go at the 26.2 distance.

For Rahsaan and the other San Quentin runners, Mount Tam, as it’s known, had become a beacon of hope. It’s the site of the legendary Dipsea, a 7.4-mile technical trail from Mill Valley to Stinson Beach. After the 1,000 Mile Club was founded in 2005, it became tradition for club members who got released to run that trail; their stories soon became lore among the runners still inside. “I’ve been hearing about the Dipsea for the longest,” Rahsaan says.

Given his sentence, he never expected to run it. Rahsaan was serving 55 years to life for second-degree murder. Life outside, let alone running over Mount Tam all the way to the Pacific, felt like a million miles away. But Rahsaan loved to run—it gave him a sense of freedom within the prison walls, and more than that, it connected him to the community of the 1,000 Mile Club. So if the volunteer coaches and other runners wanted to talk about the Dipsea, he was happy to listen.

We’ll get to the details of Rahsaan’s crime later, but it’s useful to lead with some enduring truths: People can grow in even the harshest environments, and running, whether around a lake or a prison yard, has the power to change lives. In fact, Rahsaan made a lot of changes after he went to prison: He became a mentor to at-risk youth, began facing the reality of his violence, and discovered the power of education and his own pen. Along the way, Rahsaan also prayed for clemency. The odds were never in his favor.

To be clear, this is not a story about a wrongful conviction. Rahsaan took the life of another human being, and he’s spent more than two decades reckoning with that fact. He doesn’t expect forgiveness. Rather, it’s a story about a man who you could argue was set up to fail, and for more than 30 years that’s exactly what he did. But it’s also a story of navigating the delta between memory and fact and finding peace in the idea that sometimes the most formative things in our lives may not be exactly as they seem. And mostly, it’s a story of transformation—of learning to do good in a world that too often encourages the opposite.

RAHSAAN “NEW YORK” THOMAS GREW UP IN BROWNSVILLE, A ONE-SQUARE-MILE SECTION OF EASTERN Brooklyn wedged between Crown Heights and East New York. As a kid he’d spend hours on his Commodore 64 computer trying to code his own games. He loved riding his skateboard down the slope of his building’s courtyard. On weekends, he and his friends liked to play roller hockey there, using tree branches for sticks and a crushed soda can for a puck.

Once a working-class Jewish enclave, Brownsville started to change in the 1960s, when many white families relocated to the suburbs, Black families moved in, and city agencies began denying residents basic services like trash pickup and streetlight repairs. John Lindsay, New York’s mayor at the time, once referred to the area as “Bombsville” on account of all the burned-out buildings and rubble-filled empty lots. By 1971, the year after Rahsaan was born, four out of five families in Brownsville were on government assistance. More than 50 years later, Brownsville still has a poverty rate close to 30 percent. The neighborhood’s credo, “Never ran, never will,” is typically interpreted as a vow of resilience in the face of adversity. For some, like Rahsaan, it has always meant something else: Don’t back down.

The first time Rahsaan didn’t run, he was 5 or 6 years old. He had just moved into Atlantic Towers, a pair of 24-story buildings beset with rotting walls and exposed sewer pipes that housed more than 700 families. Three older kids welcomed him with their fists. Even if Rahsaan had tried to run, he wouldn’t have gotten far. At that age, Rahsaan was skinny, slow, and uncoordinated. He got picked on a lot. Worse, he was light-skinned and frequently taunted as “white boy.” The insult didn’t even make sense to Rahsaan, whose mother is Black and whose father was Puerto Rican. “I feel Black,” he says. “I don’t feel [like] anything else. I feel like myself.”

Rahsaan hated being called white. It was the mid-1970s; Roots had just aired on ABC, and Rahsaan associated being white with putting people in chains. Five-Percent Nation, a Black nationalist movement founded in Harlem, had risen to prominence and ascribed godlike status to Black men. Plus, all the best athletes were Black: Muhammad Ali. Reggie Jackson. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. In Rahsaan’s world, somebody white was considered physically inferior.

Raised by his mother, Jacqueline, Rahsaan never really knew his father, Carlos, who spent much of Rahsaan’s childhood in prison. In 1974, Jacqueline had another son, Aikeem, with a different man, and raised her two boys as a single mom. Carlos also had another son, Carl, whom Rahsaan met only once, when Carl was a baby. Still, Rahsaan believed “the myth,” as he puts it now, that one day Carlos would return and relieve him, his mom, and Aikeem of the life they were living. Jacqueline had a bachelor’s degree in sociology and worked three jobs to keep her sons clothed and fed. She nurtured Rahsaan’s interest in computers and sent him to a parochial school that had a gifted program. Rahsaan describes his family as “upper-class poor.” They had more than a lot of families, but never enough to get out of Brownsville, away from the drugs and the violence.

Some traumas are small but are compounded by frequency and volume; others are isolated occurrences but so significant that they define a person for a lifetime. Rahsaan remembers his grandmother telling him that his father had been found dead in an alley, throat slashed, wallet missing. Rahsaan was 12 at the time, and he understood it to mean his father had been murdered for whatever cash he had on him—maybe $200, not even. Now he would never come home.

Rahsaan felt like something he didn’t even have had been taken from him. “It just made me different, like, angry,” he says. By the time he got to high school, Rahsaan resolved to never let anyone take anything from him or his family again. “I started feeling like, next time somebody tryin’ to rob me, I’m gonna stab him,” he says. He started carrying a knife, a razor, rug cutters—“all kinds of sharp stuff.” Rahsaan never instigated a fight, but he refused to back down when threatened or attacked. It was a matter of survival.

The first time Rahsaan picked up a gun, it was to avenge his brother. Aikeem, who was 14 at the time, had been shot in the leg by a guy in the neighborhood who was trying to rob him and Rahsaan. A few months later, Rahsaan saw the shooter on the street, ran to the apartment of a drug dealer he knew, and demanded a gun. Rahsaan, then 18, went back outside and fired three shots at the guy. Rahsaan was arrested and sent to Rikers Island, then released after three days: The guy he’d shot was wanted for several crimes and refused to testify against Rahsaan.

By day, Rahsaan tried to lead a straight life. He graduated from high school in 1988 and got a job taking reservations for Pan Am Airways. He lost the job after Flight 103 exploded in a terrorist bombing over Scotland that December, and the company downsized. Rahsaan got a new job in the mailroom at Debevoise & Plimpton, a white-shoe law firm in midtown Manhattan. He could type 70 words a minute and hoped to become a paralegal one day.

Rahsaan carried a gun to work because he’d been conditioned to expect the worst when he returned to Brownsville at night. “If you constantly being traumatized, you constantly feeling unsafe, it’s really hard to be in a good mind space and be a good person,” he says. “I mean, you have to be extraordinary.”

After high school, some of Rahsaan’s friends went to Old Westbury, a state university on Long Island with a rolling green campus. He would sometimes visit them, and at a Halloween party one night, he got into a scrape with some other guys and fired his gun. Rahsaan spent the next year awaiting trial in county jail, the following year at Cayuga State Prison in upstate New York, and another 22 months after that on work release, living in a halfway house in Queens. He got a job working the merch table for the Blue Man Group at Astor Place Theater, but the pay wasn’t enough to support the two kids he’d had not long after getting out of Cayuga.

He started selling a little crack around 1994, when he was 24. By 27 he was dealing full-time. He didn’t want to be a drug dealer, though. “I just felt desperate,” he says. Rahsaan had learned to cut hair in Cayuga, and he hoped to save enough money to open a barbershop.

He never got that opportunity. By the summer of 1999, things in New York had gotten too hot for Rahsaan and he fled to California. For the first time in his 28 years, Rahsaan Thomas was on the run.

EVERY RUNNER HAS AN ORIGIN STORY. SOME START IN SCHOOL, OTHERS TAKE UP RUNNING TO IMPROVE their health or beat addiction. Many stories share common themes, if not exact details. And some, like Rahsaan’s, are absolutely singular.

Rahsaan drove west with ambitions to break into the music business. He wanted to be a manager, maybe start his own label. His new girlfriend would join him a week later in La Jolla, where they’d found an apartment, so Rahsaan went first to Big Bear, a small town deep in the San Bernardino Mountains 100 miles east of Los Angeles. It’s where Ryan Hall grew up, and where he discovered running at age 13 by circling Big Bear Lake—15 miles—one afternoon on a whim. Hall has recounted that story so many times that it’s likely even better known than the American records he would go on to set in the half and full marathons.

Rahsaan didn’t know anything about Ryan Hall, who at the time was just about to start his junior year at Big Bear High School and begin a two-year reign as the California state cross-country champion. He didn’t even know there was a lake in Big Bear. Rahsaan went to Big Bear to box with a friend, Shannon Briggs, a two-time World Boxing Organization heavyweight champion.

Briggs and Rahsaan had grown up together in Atlantic Towers. As kids they liked to ride bikes in the courtyard, and later they went to the same high school in Fort Greene. But Briggs’s mom had become addicted to drugs by his sophomore year, and they were evicted from the Towers. Briggs and Rahsaan lost touch. Briggs began spending time at a boxing gym in East New York; often he’d sleep there. He had talent in the ring. People thought he might even be the next Mike Tyson, another native of Brownsville who was himself a world heavyweight champ from 1986 to 1989.

Briggs went pro in 1991, and by the end of that decade he was earning seven figures fighting guys like George Foreman and Lennox Lewis. Rahsaan was at those fights. The two had reconnected in 1996, when Rahsaan was trying to rebuild his life after prison and Briggs’s boxing career was on the rise. In August 1999, Briggs was gearing up to fight Francois Botha, a South African known as the White Buffalo, and had decamped to Big Bear to train. “He was like, ‘Yo, come live with me, bro,’” Rahsaan recalls.

Briggs was running three miles a day to increase his stamina. His route was a simple out-and-back on a wooded trail, and on one of Rahsaan’s first days there, he decided to join him. Rahsaan hadn’t done so much as a push-up since getting out of prison, but he wanted to hang with his friend. Briggs and his training partners set off at their usual clip; within a few minutes they’d disappeared from Rahsaan’s view. By the time they were doubling back, he’d barely made it a half mile.

Rahsaan never liked feeling physically inferior. So back in La Jolla, he started running a few times a week, going to the gym, whatever it took. Before long he was up to five miles. And the next time he ran with Briggs, he could keep up. After that, he says, “Running just became my thing.”

FOR YEARS, RAHSAAN HAD BUCKED AT TAKING RESPONSIBILITY for the murder that sent him to prison. The other guys had guns, too, he insisted. If he hadn’t shot them, they’d have shot him. It was self-defense.

In the moment, he had no reason to think otherwise. It was April 2000. A friend had arranged to sell $50,000 worth of weed, and Rahsaan went along to help. They met in the parking lot of a strip mall in L.A., broad daylight. The buyers brought guns instead of cash, things went sideways, and, in a flash of adrenaline, Rahsaan used the 9mm he’d packed for protection, killing one man and putting the other in critical condition. He was 29 and had been in California eight months.

After awaiting trial for three years in the L.A. County jails, Rahsaan was sentenced to 55 years to life. But for the crushing finality of it, the grim interminability, the prospect of never seeing the outside world again, he was on familiar ground. Even Brownsville had been a kind of prison—one defined, as Rahsaan puts it now, by division and neglect, a world unto itself that societal forces made nearly impossible to escape. He was used to life inside.

Rahsaan spent the next 10 years shuttling between maximum security facilities, the bulk of those years at Calipatria State Prison, 30 miles from the Mexican border. By the time he got to San Quentin, he was 42.

As part of the prison’s restorative justice program, Rahsaan met a mother of two young men who’d been shot, one killed and the other critically injured. Her pain, her dignity, her ability to forgive her sons’ shooters prompted Rahsann to reflect on his own crime. “It made me feel like, damn, I did this to his mother,” he says. “I did this to my mother. You don’t do that to Black mothers. They go through so much.”

ABOUT 2 MILLION PEOPLE ARE INCARCERATED IN THE UNITED States today, roughly eight times as many as in the early 1970s. Nearly half of them are Black, despite Black Americans representing only 13 percent of the U.S. population.

This disparity reflects what the legal scholar and author Michelle Alexander calls “the new Jim Crow,” an invisible system of oppression that has impeded Black men in particular since the days of slavery. In her book of the same title, Alexander unpacks 400 years of policies and social attitudes that have created a society in which one in three Black males will be incarcerated at some point in their lives, and where even those who have been paroled often face a lifetime of discrimination and disenfranchisement, like losing the right to vote. If you hit a wall every time you try to do something, are you really free? More than half of the people released from U.S. jails and prisons return within three years.

After Rahsaan got out of Cayuga back in 1992, with a felony on his permanent record, he’d had trouble doing just about anything legit: renting an apartment, finding a decent job, securing a loan. Though he’d paid for the Mercedes SUV he drove to California, the lease was in his girlfriend’s name. Selling crack had provided financial solvency, and his success in New York made him feel invincible. One weed deal in California seemed easy enough. But he wasn’t naive. Rahsaan packed a gun, and if he felt he had to use it, he would.