Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Search Results for Ultra

Today's Running News

‘We Are Here Because of Him’: The Runner Who Defied Apartheid

In the dying days of South Africa’s apartheid regime, pioneering Black runners helped transform the Comrades Marathon into the race it is today, one that reflects the country around it.

On a balmy Sunday morning in late August, Kgadimonyane Hoseah Tjale stood below a stadium full of roaring fans on the finish line of the Comrades ultramarathon, clutching a small air horn.

He had been here before. In the 1980s and early 1990s, Tjale racked up four podium finishes at the Comrades, a 56-mile race between the South African cities of Pietermaritzburg and Durban. Today, it is the largest ultramarathon in the world, attracting a field of up to 20,000 runners, throngs of spectators and millions of live television viewers.

The story of how the Comrades became the race it is today is bound up in the story of Tjale and other pioneering Black runners of his generation. In the dying days of South Africa’s apartheid regime, they helped transform the race from a poky, amateur affair into an enormous event that looks much like the country around it.

They did so from one of the most uneven playing fields in the modern world.

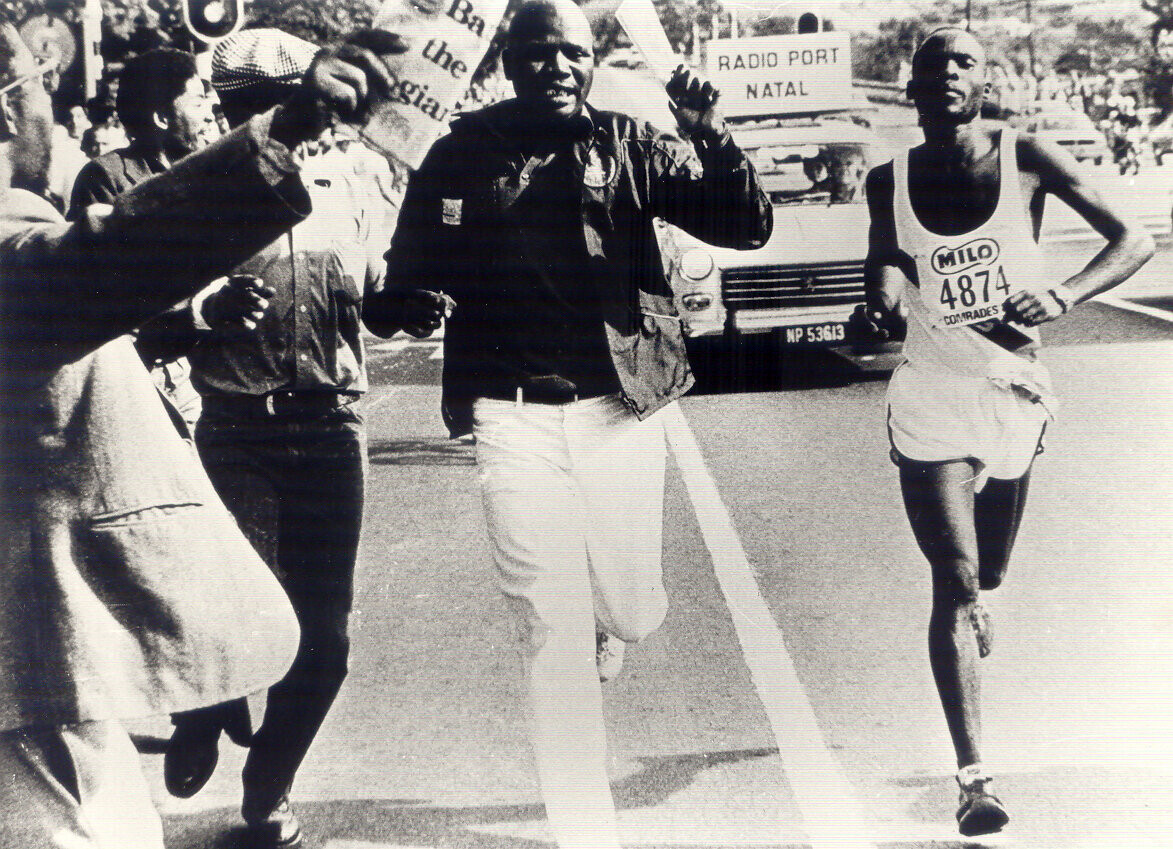

Back at the race for the first time in 29 years, Tjale marveled as the top finishers sprinted past him. In his days, nearly every top runner was white. Now, all the top men were Black, wearing the jerseys of big corporate running clubs that paid for them to attend training camps. The 2022 men’s race winner, a university security guard named Tete Dijana, earned around $42,000 in prize money and bonuses. It was equivalent to about a decade of his salary.

“There was none of that in our times,” said Tjale, a retired delivery driver who was living in a shack north of Johannesburg when he ran his final Comrades race in 1993, when the race did not offer a cash prize.

(First photo) The start of the Comrades Marathon at the Pietermaritzburg City Hall. Credit...Rogan Ward for The New York Times

Tjale had been invited back by the Comrades’ organizers to sound a horn marking the cutoff for a special medal given to runners who finish in less than six hours. In the car from the airport two days before, Tjale asked one of them why they had invited him.

Tjale had been invited back by the Comrades’ organizers to sound a horn marking the cutoff for a special medal given to runners who finish in less than six hours. In the car from the airport two days before, Tjale asked one of them why they had invited him. He’d never won the race, after all.

But for Comrades runners, the reason was obvious.

“We are here because of him,” said Freddie Wilson, a runner from Johannesburg, as he waited to take a photograph with Tjale at the race expo. His voice shook with emotion.

Like many Black South Africans, Wilson grew up watching Tjale on TV. His family didn’t have a television, but on Comrades Sunday they would crowd with others in their neighborhood into the lounge of a family who did and spend the entire day watching the race.

Wearing a bucket hat and running with a distinctive, lopsided gait, Tjale was a revelation in the front pack. From inside a country whose government was purpose-built to stifle the ambitions of Black South Africans, here was a Black man doing something audaciously ambitious, for the whole country to see.

(Third photo) Spectators running with Tjale in a Comrades Marathon during the 1980s.Credit...The Comrades Marathon Association

“He was our great,” Sello Mokone, who has run the Comrades 18 times, said. “The moment we saw a Black guy doing this, we knew we could do it too.”

At his peak, Tjale could run 56 miles at a pace of just over six minutes a mile. He racked up dozens of wins at ultramarathons, including at South Africa’s other famous ultra, the 35-mile Two Oceans. Twice, he almost defeated the Comrades’ white folk hero, a floppy-haired blond man named Bruce Fordyce, who won the race nine times between 1981 and 1990.

Bob de la Motte, a white runner who finished second to Fordyce three times, said that Tjale “was the better athlete.”

But while Fordyce focused full-time on the Comrades, living off money from speaking gigs and corporate sponsorships, Tjale worked as a delivery driver, running 15 miles from the crowded workers’ hostel where he lived to his job. On weekends, he ran every local race he could find, from 10 kilometers to 100 kilometers (6.2 miles to 62.1 miles), for prize money to supplement his income.

“He was lucky,” Tjale said of their rivalry.

Tjale grew up in the 1960s in a rural area near the city of Polokwane, formerly known as Pietersburg. He dropped out of school after eighth grade. A few years later, he moved to Johannesburg to work as a live-in gardener for a white family. There, he clipped hedges during the day and washed the family’s dishes after dinner. In between, sometimes, he went for a jog.

In the late 1970s, his running caught the attention of his employer, who helped him buy a pair of sneakers and join a running club. He began entering races, and soon, winning.

It was an auspicious moment to take up distance running. At the time, South Africa was subject to widespread international sports boycotts, which kept the country out of most major events. The nation was desperate to get back in, and in the mid-1970s, the apartheid government announced it would desegregate a minor sport, running.

Amid a global boom in running, entries at races like the Comrades began to tick upward. And South Africa’s single state-run TV station began broadcasting the Comrades live in the early 1980s. Millions watched Black runners like Tjale and white competitors like Fordyce share bottles of water and sling their arms over one another at the finish line.

“In the Comrades, everyone needed help at some point, and people always gave it,” said Poobie Naidoo, another elite South African distance runner from the 1980s, who is of Indian heritage.

But the moment runners like Tjale and Naidoo stepped off the course, they returned to an apartheid reality. In 1979, not long after his first Comrades, Tjale was arrested on his way to work for not having documents showing he was allowed to be in a white part of the city. He spent a night in jail.

“On the road was the only place I sometimes felt like apartheid wasn’t there,” Tjale said.

In 1989, both Tjale and Fordyce participated in a 100-kilometer world championship. Because of the timing, Fordyce skipped the Comrades, and Tjale ran it on tired legs. Another runner, Sam Tshabalala, became the race’s first Black champion. Tjale, meanwhile, ran his final Comrades in 1993, quietly finishing 51st.

In 2016, Tjale, a reserved man with an easy laugh, retired to a 20-acre farm he bought near Polokwane. It was one of the first times since he married in the 1970s that he and his wife had been able to live together, and they spent quiet evenings on their couch cracking jokes and watching soap operas.

He didn’t think much more of the Comrades, besides occasionally turning down invites to events the race hosted. “I was done with that thing,” he said simply.

But this year, a Comrades Marathon Association board member named Isaac Ngwenya called with a plea. Would Tjale come and let himself be honored. He agreed and last weekend boarded a plane for Durban.

Tjale arrived to a race radically transformed from the one he left. At the Comrades expo, thousands of runners — most of them Black — milled around, trading training stories. The night before the race, more than 300 people slept in the Pietermaritzburg Y.M.C.A., where race organizers put up entrants who could not afford accommodation.

“It’s something I can show my son, and myself — that I did this thing,” said Cynthia Smith, a security guard, as she stretched out on her foam mattress.

On the start line at Pietermaritzburg City Hall the next morning, more than 13,000 runners sang an old migrant laborers’ song called Shosholoza, whose title means “go forward.” The gun popped, and they surged into the winter morning.

“It’s like living your entire life in a single day,” Tommy Neitski, a 42-time finisher, said of the race’s mass appeal. It’s also like seeing all of South Africa in a day, on a course that winds its way past shacks and boutique hotels, sugar cane fields and gritty industrial towns.

Tjale arrived at the finish line at Durban’s Moses Mabhida Stadium to sound the six-hour horn. Waiting in a V.I.P. lounge, he ran into Jetman Msuthu-Siyephu, winner of the 1992 race. They spent the morning trading memories.

As the day wore on, the two men watched the salt-streaked runners pour in by the thousands, dissolving in joy and exhaustion as they stumbled over the finish line. Tjale couldn’t stop smiling.

“When we go,” he said to Msuthu-Siyephu, “we will have left something for this world.”

(09/04/2022) ⚡AMPby Ryan Lenora Brown (New York Times)

Comrades Marathon

Arguably the greatest ultra marathon in the world where athletes come from all over the world to combine muscle and mental strength to conquer the approx 90kilometers between the cities of Pietermaritzburg and Durban, the event owes its beginnings to the vision of one man, World War I veteran Vic Clapham. A soldier, a dreamer, who had campaigned in East...

more...Kilian Jornet Isn't The G.O.A.T. of Trail Running Just Because He Wins Big Races

After Kilian Jornet won the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB) for a record-tying fourth time on August 27, it was easy to assume that running 100 miles is something that comes easy to him.

It doesn't, but it would be easy to think that because, well, it sure looked that way.

While the 34-year-old who hails from the Catalan region of Spain has long ago established himself as the G.O.A.T. of ultra-distance trail running in the mountains, he's as human as each of the other 2,300 runners who toed the line at this year's UTMB. Like his fellow competitors, Jornet felt fatigue in his legs from grinding through the 171.5km (106.5-mile) course and its 33,000 feet of elevation gain. He said he had difficulty breathing when he ran too fast or climbed too abruptly, likely the lingering effects of having just overcome Covid-19 earlier in the month.

And, like everyone else, he had to fight off low moments of mental torment, and maybe even a tiny trace of self-doubt-remember, he's human-as American rival Jim Walmsley opened up a big lead on him over the Grand Col Ferret as the course passed from Italy to Switzerland.

But what sets Jornet apart, and what has always distinguished him as an athlete, is a unique combination of physical ability, smart racing strategy and a deep connection to the mountains that allows him to move joyfully, patiently and, at times, seemingly with relative ease amid the physical anguish that comes with running such a grueling race.

But make no mistake, he suffered enroute to winning UTMB in a course-record 19 hours, 49 minutes, even if he made it look easy overcoming Walmsley and dispatching competent French contender Mathieu Blanchard.

"Since the start there has not been a single moment in which I didn't suffer," Jornet said after the race. "I knew that I needed to keep my intensity under a certain threshold where it can be heavy for the lungs, but it was no problem. But muscularly it was very hard from the start of the race."

Jornet is human, even if it took a debilitating illness to show it. But as he turned in yet another masterwork performance on the world's biggest stage, Jornet gave glimpses of what has made him so otherworldly for so long. Perhaps surprisingly, superior physicality is only a small part of it.Patience and Respect

Having already won UTMB three times and Hardrock a record-tying five times-most recently just six weeks earlier-Jornet had nothing to prove in Chamonix. In fact, if he had never toed the line or for that matter retires from competition, his legacy of epic race victories and Fastest Known Time (FKT) records on some of the most difficult trails and biggest mountains around the world would stand the test of time.

But that brings up another element that makes Jornet great is that he has always run as if he had nothing to prove. Sure, he's a competitive athlete, but his focus seems to be more about immersing in the zest of competition and the life-affirming bliss he's always felt in the mountains.

For Jornet, the destination truly is the journey, not the outcome. That adventure-oriented focus was something he learned in his youth growing up in the high-alpine environment of the Cap de Rec mountain refuge in the Spanish Pyrenees, where his dad was a mountain guide and his mom was a ski instructor. He climbed his first peak at age 3 and started competing in ski mountaineering races at 12.

Along the way, he developed a grounded sense of presence in the mountains that has allowed him to remain calm and bide his time in ultra-distance races-especially more rugged mountain races like UTMB and Hardrock. Instead of going all-out from the front, he typically follows a more fluid strategy of just staying in contact with the lead group and letting the race play out a bit as the terrain dictates before becoming hyper-competitive.

Contrast that to Walmsley, who has been hellbent on becoming the first American man to win the race with a front-running mentality, countryman Zach Miller, who returned after injuries and Covid-19 kept him away from continuing the same pursuit for three years, and the hard-charging Blanchard, who was eager to steal the show and make a name for himself in front of a supportive mostly French crowd after a robust third-place finish in 2021.

Even when Jornet was younger, he ran with maturity and wisdom beyond his years, always earnestly clinging to the premise that the experience of racing-and sharing it with his competitors, not to mention spectators and volunteers when possible-is always more important than the actual race itself.

When Walmsley built a big lead with a strong power-hiking surge up the Grand Col Ferret, Jornet was seemingly content, at that moment, to ease through the highest point of the course, chatting at times with volunteers, fans and videographers in French, Spanish or English as he had done at times earlier in the race. In previous UTMB races, he's burst ahead on the switchbacks up Grand Col Ferret and other steep climbs on that course, only to stop on top and wait for his competitors to catch up while gazing at the stars or picking mushrooms with children.

"At Hardrock this year, when I saw him on top of Grant Swamp Pass, he stopped in the middle of the race just to chat with me because we hadn't seen each other in a while," Miller says. "That's just the way Kilian is."A Versatile Mountain Athlete

Jornet has a much more diverse set of athletic skills and abilities than most ultrarunners. In addition to winning ultras, Jornet was a multiple world champion in ski mountaineering and SkyRunning in his twenties. He also set a host of new speed ascent marks and roundtrips on Mt. Kilimanjaro (Tanzania), Aconcagua (Argentina), Mont Blanc (France) and the Matterhorn (Switzerland). Although he missed in his attempt to set a new FKT on 29,032-foot Mt. Everest in 2017, he actually summited the world's highest mountain twice in six days without supplemental oxygen.

When he was a few years younger, he set a new record on the 171-mile Tahoe Rim Trail in California and Nevada and posted the fastest-ever time up the steep, rocky 1.3-mile Mt. Sanitas Trail in Boulder, Colorado.

"Kilian is a beast," says Francois D'Haene, the other four-time UTMB winner who last year became the first to win Hardrock and UTMB in the same summer. "When it comes to Vertical K races and distances from 40K to 100K, I think there is no competition between us. He's faster than me and stronger than me, especially on technical terrain."

Aside from long-and-rugged Hardrock and UTMB, Jornet won the shorter and much faster 42km Zegama Alpine Marathon in Spain and placed fourth in the 31km Sierre-Zinal village-to-village race in Switzerland in August. A lot of it has to do with the fact that he still trains in much of the same fashion as he did as a kid, often focusing more on fun, hard, playful days of adventure on foot or on skis as much as he does structured high-performance workouts.

"Kilian is unique in the range that he can cover," Miller says. "As a runner, his ability to switch back and forth from something like Zegama to Hardrock to Sierre-Zinal to UTMB is just incredible. And because of that ability, I think he's a bit of a mad scientist when it comes to training. He kind of turns himself into a guinea pig and trains in ways other guys might not be willing to for fear of overtraining."

All of that translated into Jornet's ability to win this year's UTMB despite trailing Walmsley by about 15 minutes at the 126km aid station at Champex. When the surging Blanchard caught him and quickly left the aid station, Jornet's competitiveness and mountain practicality started to fire up. They passed Walmsley and gapped him and then ran stride for stride over the ensuing 2,300-foot climb from the village of Trient down into the ski town of Valloricine.

Finally, after leaving the 153km aid station at the same moment as Blanchard, Jornet surged on a gently sloped 4km section of trail to the base of the final 2,600-foot climb up Tte aux Vents. Blanchard got a first-hand view of the master at work and all he could do was watch him run away to victory and hold on for second place.

"Running from Champex with Mathieu, I knew I was stronger going up but that he was catching on the downhills," said Jornet, who has lived in Norway for the past several years with his wife, Emelie Forsberg, and their two young children. "Once we got to Valloricine, the strategy was to push very hard up the final climb to Tte aux Vents and then manage the lead. I had about an 8-minute lead and I was feeling comfortable with it, but in a ultra race you never know, many things can happen."A Transcendent Athlete

At some point a conversation about Jornet should transcend trail running and include the similarities he shares with other great athletes who have had a similarly dominant presence in other sports. And yes, that means Tom Brady, Michael Jordan, Lindsay Vonn, Eddie Merckx, Michael Phelps, Ann Trason, Lynn Hill, Kelly Slater and Eliud Kipchoge.

Why not? Like each of those all-time athletes, Jornet has consistently risen to the occasion at the biggest moments of his career, not only because he physically outclasses the competition, but also because his intellectual prowess as an athlete and his ability to outthink, outwit and outlast them. It's not that he wins everything-although he's won the vast majority of his races since winning UTMB as a 20-year-old in 2008-it's more that he's been competing at the highest level for 15 years and hasn't regressed and has rarely had bad days.

In 2017, he had a rough go of it in the UTMB and finished second to D'Haene and in 2018 he dropped out after inflammation and pain caused by a pre-race bee sting made it difficult to keep running.

"Even his bad races he performs well, and I think that's what makes Kilian special," says Walmsley, who finished fourth at UTMB this year. "Whether it's a bad moment or a bad race, he's always still competing at a really high level. I have raced him twice at UTMB and both times I have thought I have found a crack, but I haven't been able to hold onto it."

Until recently, Jornet might have been viewed solely for his athletic. But with his bold move this year to break away from longtime sponsor Salomon and begin a new environmentally friendly trail running shoe brand called NNormal (with Spanish footwear brand Camper), he's not only begun to hone his entrepreneurial spirit in the world of business but also to make an impact as the environmental steward he's always been.

It's a path only a handful of high-level outdoor athletes achieved success at after making their mark in their sport disciplines, most notably Yvon Chouinard, a climber, surfer and kayaker who founded Patagonia in 1970.

Jornet ran all of his races this year in the same model of NNormal shoes that will be available at running shops and online this fall. It's a uniquely designed shoe that's balanced under the midfoot to promote midfoot and forefoot running gaits, but with enough cushioning to run with a heel-striking stride, especially on downhill sections of a trail. A thin polyurethane plate provides protection from rocks and some energy return, while a proprietary version of a Vibram Litebase Megagrip outsole serves up secure traction.

That all might sound pretty standard, but Jornet really wants his NNormal shoes to stand out for their durability. He and his colleagues have gone to great lengths to source long-lasting components, but they've also designed the shoe to be deconstructed so it will be easy to re-sole, repair or recycle it after hundreds of miles of wear and tear. It's all part of NNormal's No Trace philosophy that is all aimed at transparently designing gear with the smallest carbon footprint possible.

"There are a lot of good guys in the sport, but in [my] mind, Kilian is the king of the sport," says Miller, who was the fifth finisher at UTMB this year. "He sets the tone for the entire sport and [is] a great representative of the sport."

(09/03/2022) ⚡AMPby Trail Runner Magazine

This Ultrarunner Outlasted a Fully Charged Tesla

Bobbie Balenger ran a staggering 242 miles in three days, covering more distance than an electric vehicle on a single charge.

Endurance runner Robbie Balenger set a world record last year when he completed 16 laps of the Central Park Loop Challenge, running a total of 100 miles in the course of a single day. His most recent ultrarunning accomplishment—attempting to run further than a Tesla electric car on a single charge—is the subject of a new documentary from Ten Thousand, as part of their ongoing Feats of Strength series.

Firstly, the Tesla sets off from the same starting point where Balenger will begin his run, and is driven across the state of Texas until its battery is depleted, which occurs after 242 miles. Balenger then assigns himself 72 hours to surpass that distance on foot, a feat which he expects to be as challenging mentally as it will be physically.

It's just between my two ears, that battle," he says. "And that battle can get pretty lonely." However, he embraces the unpleasant aspects of the experience, like the physical discomfort, fatigue, and soreness which persist and only get worse as he covers more distance.

"I say that running is the inverse of a drug," he continues. "With drugs, you feel really good while you're doing it, then you feel like shit afterwards. With running, especially when you get into it, you feel like shit while you're doing it then you get to feel great afterwards."

At the halfway mark of 121 miles, Balenger pauses for an hour and 50 minutes of rest. He is then joined for the second stretch by a number of other endurance athletes, including Ironman triathlete Nick Bare and distance runner Hellah Sidibe, who run alongside him while offering encouragement.

46 hours in, at 5:30 a.m., Balenger takes another 50-minute nap before heading into his third and final day of running. "One of the things that draws me to these things is you are so aware of yourself and being alive while doing it," he says. "Through the pain, all of it, every sense is heightened."

After 76 hours 54 minutes, Balenger has run a total distance of 242.01 miles, outlasting the Tesla in terms of distance even if he went over his original time target of 72 hours. Ultimately, he says he is grateful to all of the people who helped him on his journey, and proud of himself and what he has accomplished.

"The bigger picture in life is just follow-through," he says. "You break through these versions of yourself, and tear it away and come out a new person, which I think happens for everyone as we evolve through chapters in life, but what's interesting is ones that happen so quickly... There's very few experiences in life where you look back three days later and you're like, I do not recognize that person."

(09/03/2022) ⚡AMPAmerican ultrarunner completes barefoot trek of California's John Muir Trail

American ultrarunner Kenneth Posner completed a 22-day trek along California’s 210-mile (337K) John Muir Trail (JMT) on Saturday. While Posner didn’t run the route, he is an avid trail runner and ultrarunner, and he almost exclusively runs barefoot. He didn’t take to the JMT to break any official records (the various fastest known time records for the JMT hover around two to four days), but rather for a personal challenge: to hike the entire trail without shoes.

Completing a trail completely barefoot may seem like a random goal to many people, but for Posner, it has been a years-long battle. As he explains in his blog, he made his first barefoot JMT attempt in 2020. “Barefoot is simple,” he writes. “Natural. Intense. Every step is an adventure.” That initial shot at the JMT resulted in Posner completing about 240K of it without any footwear. For the other 100 or so kilometres, he was forced to don shoes. “The terrain [on the JMT] was more difficult than I expected.”

In 2021, he returned to the California trail, certain that he could finish the whole thing without resorting to shoes. Once again, though, he succumbed to the difficult terrain of the JMT, and he had to give in and put on shoes. Since then, he has been working toward the same goal, and this year, he managed to pull it off.

He set off on the JMT in early August, heading south from Yosemite National Park. The trek took him through mountainous terrain all the way to Kings Canyon National Park, where he finally reached the end of the JMT.

“Just completed the 210-mile #JohnMuirTrail entirely #barefoot, in 22 days,” Posner tweeted. “The sandy trails were lovely, the rocky mountain passes were challenging, and the gravel was quite difficult. Gave me new appreciation for how patient and tough our ancestors must have been.”

(09/03/2022) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

Camille Herron’s breakfast of champions, Fuel up and go chase a world record (or maybe a PB)

I’ll try any running (or eating!) advice Camille Herron has to offer. The multiple world-record holder continuously levels up, finding new ways to improve her running and racing. Herron is in South Africa running the downhill course of the legendary Comrades Marathon this weekend, an 89K ultra that she won (on the uphill course) in 2017.

She shared with us the pre-run breakfast she swears by. If you haven’t heard of teff, you aren’t alone; while Westerners are still learning about the tiny, protein-rich grain, it’s been a staple in Ethiopian cooking for thousands of years. Teff has a mild, nutty flavor. Herron substitutes it for oatmeal, and says it’s been a “game-changer.”

Camille Herron’s breakfast of champions

Ingredients

4 Tbsp of teff

1 Tbsp ground flax seed

1 Tbsp chia seeds

Handful of cut walnuts

Handful of blueberries

1 tsp camu powder

1 tsp bee pollen

1 Tbsp non-fortified nutritional yeast

1 to 2 Tbsp honey

Pinch of salt

Directions

Add hot water, stir, and let sit for 10 to 15 minutes. Add or substitute any nuts or fruit that you enjoy. Herron says teff has been a pre-run fuel revelation for her: “it doesn’t retain as much water as oats, so it doesn’t feel heavy on the gut pre-run.” She adds, “it feels like it stabilizes blood sugar for a long time.”

1 Tbsp wheat germ

(09/01/2022) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

British ultrarunner completes 2,850 km run along Europe’s Danube River

Kieran Alger ran the length of the second-longest river in Europe in 67 days.

If you’ve travelled to Budapest, Vienna or a number of other European cities, you might have run along the Danube River. That’s what British ultrarunner Kieran Alger just finished doing on Tuesday, but unlike what was likely a chill mid-vacation run for you, he did it for 67 days.

The Danube is the second-longest river in Europe, passing through 10 countries and spanning 2,850 kilometres, and Alger covered it from point to point. He called this challenge Danube Sea to Source and used it to raise money for five different charities, all of which fight child poverty.

Alger started his run on June 25 on the coast of the Black Sea in Romania. From there, he simply followed the Danube, taking every twist and turn the river makes. This challenge was almost completely unsupported, meaning Alger didn’t have a crew following along and meeting up with him at every pitstop. He carried his own supplies (a 22-pound bag) and camped most nights.

As Alger told the BBC after finishing his journey, he believes he is the first person to complete this running challenge along the Danube. As one would imagine, the Sea to Source was hardly an easy endeavour, but Alger said he had to fight more than just fatigue.

“In Romania, I battled lots and lots of wild dogs,” he said. “I suffered a couple of dog attacks … and I had to run quite a lot of those stretches on high alert.”

While this made the run even more difficult, Alger said he found that “the struggles made the highlights even better.” After crossing his finish line in Donauschingen, Germany, on Tuesday, Alger stopped the clock on his challenge after 67 days of running. That works out to more than a marathon every day for more than two months.

(08/31/2022) ⚡AMP

by Ben Snider-McGrath

America’s Camille Herron finished sixth at the Comrades Marathon on August 27

"Oh Comrades Marathon you were magical! Thank you everyone for making us feel like rockstars out there. I’m proud to finish 6th this time and another top 10 finish. It was an honor to be here again and share the road with you all. Enjoy the moment for all your hard work," posted Camille Herron.

Camille Herron is an American ultramarathon runner. She is the first and only athlete to win all three of the International Association of Ultrarunners' 50K, 100K, and 24 Hour World Championships.

She won the 2017 Comrades Marathon and holds several World Record times at ultramarathon distances, along with the Guinness World Record for the fastest marathon in a superhero costume.

In November 2017, she broke Ann Trason's 100-mile Road World Record by over an hour in 12:42:40. She broke her 12-Hour and 100 Mile World Records in February 2022 at the Jackpot 100/US Championship, winning the race outright and beating all of the men.

In April 2022, she became the youngest woman to reach 100,000 lifetime miles. She is the first and only woman to run under 13 hours for 100 miles, exceed 150 km for 12-Hours, and to reach 270 km for 24Hrs.

(08/29/2022) ⚡AMPComrades Marathon

Arguably the greatest ultra marathon in the world where athletes come from all over the world to combine muscle and mental strength to conquer the approx 90kilometers between the cities of Pietermaritzburg and Durban, the event owes its beginnings to the vision of one man, World War I veteran Vic Clapham. A soldier, a dreamer, who had campaigned in East...

more...Benefits and limits of speed training for endurance runners

Interval training, repetitions or speed work are terms many people taking up athletics will often hear but what do they mean, where should it fit within your training and what are the potential pitfalls you should avoid when introducing it into your plan?

This guide will help provide some fundamentals.

For the sake of this article, intervals, repetitions and speed work will all be seen as the same general type of training, though in reality some coaches will have slight variances in their interpretations of those different terms.

The theory behind speed training

When aiming to lower a personal best time, many coaches believe that running at paces quicker than or around your goal pace is important. This is for a variety of reasons not limited to:

Preparing yourself mentally to run at those speeds and learning what it feels like physically

Stimulating the recruitment of fast-twitch muscles fibres

Fast-twitch muscle fibres are used for short, explosive movements as opposed to slow-twitch muscle fibres, which are less powerful but fatigue slower.

A higher proportion of fast-twitch muscle fibres will increase your top-end running speed while a higher proportion of slow-twitch muscles may increase your overall endurance. Striking a balance will be important to most runners, competing in all but the most extreme ultra-marathon distances.

Improving your running economy (how efficient you are in terms of the way you run) both at top speeds and at slower paces

Slower running will likely improve your aerobic fitness but will not stimulate the body to produce fast-twitch muscle fibres in the same way speed training does. This is because the body does not require as many fast-twitch muscles fibres to run at slower speeds.

How important speed training is for you will be depend on the races you are planning to partake in, though most distances will benefit from it to some degree.

Are you aiming to complete an ultra-marathon or is the 1500m your goal race?

What does speed training look like?

In the same way that the importance of speed training will depend on what events you are planning for, your speed training will look different based on your planned event.

Runners aiming to run the 1500m may well do fewer shorter reps at higher speeds, with 10,000m runners increasing the length of repetitions and sometimes the volume too.

Please note the sessions detailed below are not introductory sessions and should be worked up to over a period of months not weeks.

- Two typical 1500m sessions

3 to 4 x 500m with two to three minutes recovery between repetitions. These may be done at your target 1500m pace

3 x (800m, 200m, 200m) – three minutes between sets (after completing all the efforts within the brackets), 90 seconds between the repetitions (those within brackets)

- Two typical 10,000m sessions

8 x 1000m with two minutes recovery between efforts. All run at 10,000m goal pace.

1600m, 1200m, 800m, 800m, 1200m, 1600m. Two to three minutes between efforts. These would ideally be run slightly outside 10,000m goal pace for the longer efforts, and slightly inside for the shorter efforts. The idea is to keep the paces reasonably even, with a marginal increase in speed for the shorter efforts if possible.

How speed training fits with your overall training programme

It is impossible to sustain these types of sessions day after day, due to the significant impact each session has on your body.

Many runners choose to incorporate some kind of speed training once a week with some experienced and elite-level runners increasing this where they have more time to recover.

It is important to see how your body responds to these sessions, be honest with the impact they have and be conservative where they may cause a risk of injury.

In order to get the maximum benefit from these sessions, allow your body to recover by running slower than you normally would on the day or two following the session.

The dangers associated with speed training

Runners should be patient and build up to any speed training they do. If you try it too early without preparing your body through some easier running, muscle injuries can be more likely.

Alongside lighter running, strength and conditioning exercises for your calves, quads and hamstrings can help ensure that you are better prepared when you first start speed training.

As mentioned, these sessions will tire you out significantly more than most slower running, so be sure to watch out for the signs of overtraining, such as increased fatigue, excess soreness and an elevated heart rate when resting.

If you experience any of these, it may indicate it is time to back off your training, and be sure to speak to a qualified professional where possible to provide you the best advice.

Finally running at increased speeds may bring with it the temptation of lighter, faster shoes. These can be useful but the less cushioning can cause greater strain on your leg muscles.

Be sure to slowly introduce these to your sessions so that your legs have time to adapt.

Enjoy the training.

Think about how important speed is to your running goals.

(08/29/2022) ⚡AMPby George Mallett (World Athletics)

How Dani Moreno Became the First-Ever American Woman to Podium at the OCC Race at UTMB

"How far is the podium?!" Dani Moreno yelled to her French friend as she crested a high point in the race at this week's hyper-competitive OCC race, based in Chamonix, France.

"Too far!" her friend responded.

He would later regret saying that. Why? Because 6 hours and 17 minutes after starting, Dani Moreno, 30, from the Mammoth Lakes, California, secured her spot on the podium to finish in third place, the first-ever American woman to reach this level at OCC.

The OCC (Orsieres-Champex-Chamonix) race is a 56km (35 mile) option with 3500 m (11,500 feet) of elevation gain. Unlike the UTMB 100-mile race that circumnavigates Mount Blanc, starting and finishing in Chamonix, France, the OCC option begins in Switzerland and stays in the Valais region, until the finish, where it drops into the Chamonix valley. Winners expect to arrive at the finish in under six hours, while the cutoff is 14 hours, 30 minutes.

Weeks prior to OCC, Moreno experienced an unusually difficult race at Sierre-Zinal, in Switzerland. Before the race, she lost someone close to her back at home and a funeral service was the week of the race. She thinks the emotion caught up with her.

"I went into that race realizing I hadn't fully grieved," said Moreno. "I didn't represent myself and all this work I'd done." But after overwhelming support from friends and family, she recalibrated for OCC and showed up ready to compete. Her fiance traveled to Chamonix to help crew, along with a couple of friends.

Early in the race, Moreno would pass competitors on the ups and get passed on the downs, and yet she kept saying to herself: trust, trust, trust. Trusting in her strengths and pacing was critical, and it paid off halfway into the race.

"I passed five girls and moved into fourth at the halfway point," she said. "I could see the third-place woman but didn't know what was happening in front of them. Then third place and I were battling it out."

"You are As Strong As You Think You Are"

Moreno's secret weapon? Having fun-no matter what.

"It was fun the whole time," said Moreno. "Well, maybe the last downhill was agonizing because I was really trying to see if I could catch second place." She would make airplane arms, pretending to fly, while high-fiving spectators, always with a smile. "It felt like a fun day out with my friends."

Before the last descent, she received a huge boost after seeing her ultrarunning hero, Ruth Croft, who offered her words of encouragement. And at one of the last spots along the course, she remembers her fiance yelling to her: "You are as strong as you think you are!"

"Those last 90 minutes I sort of blacked out," said Moreno, digging deep to try and catch up to the second place woman. A few hundred yards from the finishing chute, she knew she'd done it, and the joy of her last few hundred yards was palpable. "It was a lot. First, I was like, I did it, but then I was like we did it. My coach, my family, everyone that believed in me."

Moreno finished in 6 hours and 17 minutes, only 7 minutes off the winning woman, Sheila Aviles, from Spain. The second-place woman, Nria Gil, finished only one minute ahead. Other American women in the top ten were Kimber Maddox (4th) and Allie McLaughlin (6th).

Running As Expression, Running As Order.

Dani Moreno moved to the eastern slope of California's Sierra Nevada Mountains after living and attending university at UCSB, where she ran cross country. Moreno is a four-time member of Team USA and a two-time USA champion. In addition to competing at the highest levels of the sport, Moreno maintains a full-time job at a construction firm, working in mergers and acquisitions.

"First, I was like, I did it, but then I was like we did it."

OCC was the longest race-both time and distance-that Moreno had ever pursued. But on her website, she writes that her goal is "to solidify myself as one of the best mountain runners in the world at the sub-ultra-distances." Refreshingly, she appears content with fine-tuning her performances in shorter trail races. So often in this sport, athletes feel pressure to level up to increasingly longer distances. For the next couple years, Moreno hopes to focus on marathon trail distances. However, more ultras are very much on the horizon.

"My plan is to do a 100K in the next year and a half, nestled between other shorter races, and keep inching my way up," she said. Moreno mentioned not wanting to do the CCC yet, the 101K option at UTMB. Yet.

"I'd like to do OCC again, and go about a little more aggressively this time." She plans to finish the Golden Trail Series, too, which she did last year.

Want to Run a UTMB Race? Here are Moreno's Three Rules:

Respect the weather. The weather in this dramatic region can change in an instant. Be ready for anything. "Practicing with your equipment is key," she says.

Learn how to move and fuel. Moreno is strict about practicing eating and drinking while training. During her OCC race she mixed up sports drinks and foods, things she was familiar with. The best place to learn what works-and what doesn't-is during training. "It's okay to fail during training," she said. Better to fail in training than in a race.

Be prepared for undulations. Constant ups and downs. "The undulations. Sometimes in the U.S. we tend to only go up and then down, and that's it. Here, there are multiple [big] ups and downs."

Beyond the competition, Moreno seeks trails not only as an elite athlete, but as a way of becoming a whole person, of building order and resiliency into her life.

"It helps me get through a lot of stuff," said Moreno. "It helps me organize and compartmentalize stuff in my life. Sometimes in life I can get overwhelmed by my emotions, Running provides important guidelines for that."

(08/28/2022) ⚡AMPNorth Face Ultra Trail du Tour du Mont-Blanc

Mountain race, with numerous passages in high altitude (>2500m), in difficult weather conditions (night, wind, cold, rain or snow), that needs a very good training, adapted equipment and a real capacity of personal autonomy. It is 6:00pm and we are more or less 2300 people sharing the same dream carefully prepared over many months. Despite the incredible difficulty, we feel...

more...ADHD and runners: can diet help with management?

As a sports nutritionist, I commonly counsel runners and other athletes who have Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder—generally referred to as ADHD (or ADD). ADHD is characterized by hyperactivity, impulsivity, and/or inattention. It affects 4-10% of all American children and an estimated 4.4% of adults (ages 18-44 years). ADHD usually peaks when kids are 7 or 8 years old. Some of the ADHD symptoms diminish with maturation but 65-85% of the kids with AHDH go on to become adults with ADHD.

Ideally, runners with ADHD get the help they need to learn how to manage their time and impulsiveness. Unfortunately, many youth athletes with ADHD just receive a lot of negative feedback because they have difficulty learning rules and strategies. This frustrates teammates and coaches. Older athletes with ADHD often run to reduce their excess energy, calm their anxiety, and help them focus on the task at hand. This article offers nutrition suggestions that might help coaches, friends, and parents, as well as runners with ADHD, learn how to calm the annoying ADHD behaviors.

• To date, no clear scientific evidence indicates ADHD is caused by diet, and no specific dietary regime has been identified that resolves ADHD. High quality ADHD research is hard to do because the added attention given to research subjects with ADHD (as opposed to the special diet) can encourage positive behavior changes. But we do know that when & what a person eats plays a significant role in ADHD management and is an important complimentary treatment in combination with medication.

• ADHD treatment commonly includes medications such as Concerta, Ritalin & Adderall. These medications may enhance sports performance by improving concentration, creating a sense of euphoria, and decreasing pain. These meds are banned by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and the International Olympic Committee (IOC). Hence, runners who hope to compete at a high level are discouraged from taking ADHD medications

• To the detriment of ADHD runners, their meds quickly blunt the appetite. Hence, they (like all athletes) should eat a good breakfast before taking the medication.

• The medication-induced lack of appetite can thwart the scrawny teen runner who wants to gain weight and add muscle. Teens should be followed by their pediatricians, to be sure they stay on their expected growth path. If they fall behind, they could meet with a registered dietitian (RD) with knowledge of sports nutritionist (CSSD) to help them reach their weight goals.

• An easy way for “too thin” runners to boost calories is to swap water for milk (apart from during exercise). The ADHD athlete who does not feel hungry might find it easier to drink a beverage with calories than eat solid food. Milk (or milk-based protein shake or fruit smoothie) provides the fluid the athlete needs for hydration and simultaneously offers protein to help build muscles and stabilize blood glucose.

• A well-balanced diet is important for all runners, including those with ADHD. Everyone’s brain and body need nutrients to function well. No amount of vitamin pills can compensate for a lousy diet. Minimizing excess sugar, food additives, and artificial food dyes is good for everyone.

• Eating on a regular schedule is very important. All too often, high school runners with ADHD fall into the trap of eating too little at breakfast and lunch (due to meds), and then try to perform well during afterschool sports. An underfed brain gets restless, inattentive, and is less able to make good decisions. This can really undermine an athlete’s sports career

• Adults with ADHD can also fall into the same pattern of under-fueling by day, “forgetting” to eat lunch, then by late afternoon are hangry and in starvation mode. We all know what happens when any runner gets too hungry – impulsiveness, sugar cravings, too many treats, and fewer quality calories. This is a bad cycle for anyone and everyone.

• All runners should eat at least every four hours. The body needs fuel, even if the ADHD meds curb the desire to eat. ADHD runners can set a timer: breakfast at 7:00, first lunch at 11:00, second lunch at 3:00 (renaming snack as second lunch leads to higher-quality food), dinner at 7:00.

•For high school runners with ADHD, the second lunch can be split into fueling up pre-practice and refueling afterwards. This reduces the risk of arriving home starving and looking for (ultra-processed) foods that are crunchy, salty, and/or sweet.

• (Adult) runners with ADHD are often picky eaters and tend to prefer unhealthy snacks. For guidance on how to manage picky eating, click here for adults and here for kids.

• Fiber-rich fruits, vegetables, and whole grains can be lacking on an ADHD runner’s food list. Their low fiber diet can lead to constipation. Fiber also feeds the zillions of microbes in their digestive tract that produce chemicals that can positively impact brain function and behavior. Everyone with ADHD should eat more fiber-rich foods like beans (hummus, refried beans in a burrito), seeds (chia, pumpkin, sunflower, sesame), and whole grains (oatmeal, brown rice, popcorn). They offer not only fiber but also magnesium, known to calm nerves.

• With more research, we’ll learn if omega-3 fish oil supplements help manage the symptoms of ADHD. At least, eat salmon, tuna, and oily fish as often as possible, preferably twice a week, if not more.

• Picky eaters who do not eat red meats, beans, or dark leafy greens can easily become iron deficient. Iron deficiency symptoms include interrupted sleep, fatigue, inattention, and poor learning and can aggravate ADHD. Iron deficiency is common among runners, especially females, and needs to be corrected with iron supplements.

• While sugar has the reputation of “ramping kids up”, the research is not conclusive about whether sugar itself triggers hyperactivity. The current thinking is the excitement of a party ramps kids up, more so than the sugary frosted cake. Yes, some runners are sugar-sensitive and know that sugar causes highs and crashes in their bodies. They should choose to limit their sugar intake and at least enjoy protein along with sweets, such as a glass of milk with the cookie, or eggs with a glazed donut. Moderation of sugar intake is likely more sustainable than elimination of all sugar-containing foods.

(08/27/2022) ⚡AMPby Colorado Runner

Brazilian Runner Dies After Fall During UTMB Team Event

A Brazilian runner, 40, was fatally injured at the Petite Trotte à Léon, part of the UTMB ultra, earlier this week.

The unidentified man fell 30-50 feet around 1:30 a.m., only 23 miles into the race.

The Ultra Trail du Mont Blanc (UTMB) got off to a tragic start following the death of a Brazilian runner earlier this week. The 40-year-old runner, whose identity remains anonymous, was fatally injured on the first night of the 300K (186-mile) Petite Trotte à Léon (PTL) team event.

“The runner was with his team on an official trail, which is secured for the PTL and marked throughout the year, between the Col de Tricot and the Refuge de Plan Glacier,” UTMB officials said about the accident, which occurred about 23 miles into the race.

At around 1:30 a.m. CET, the two-person Brazilian team was in a remote portion of the course with loose stones. It was there, above the French village of Les Contamines, that the victim fell an estimated 30 to 50 feet.

An Italian team, which was pacing behind the Brazilians, reported the incident after discovering the victim’s teammate safe, but in shock. A helicopter team responded shortly after and pronounced the runner dead before flying his body and teammate to a local hospital.

“It’s so very sad, but it was an accident,” Catherine Poletti, cofounder of the UTMB and president of the UTMB Group, told Outside. “When you go into nature for adventure—it may be the mountains, it may be the sea—but all the time there is a risk. We cannot provide something with zero risk. It’s impossible. I think that’s a good thing because when you want to have an experience or adventure, you absolutely need to know where the limits are, what your experience is.”

The remaining 104 teams could choose whether they wanted to finish the race—all decided to keep running.

Approximately 240 participants began this year’s PTL in Chamonix, France, on August 22. They will cover 82,000 feet of elevation gain within the Mont Blanc massif, traversing France, Switzerland and Italy.

To enhance runner safety, the race has instituted specific protocols, like selecting athletes based on criteria meant to ensure their successful completion. Runners are required to possess sound knowledge of the mountain environment, since they will likely encounter precarious weather conditions while also navigating steep slopes, falling stones, narrow paths, and glaciers. Due to a lack of marked trails, participants must be able to read a map and use a compass and altimeter, too.

While the PTL must be completed in autonomy, there are aid stations where participants can sleep and eat by cashing in one of their four meal tickets. While on course, runners are tracked with GPS beacon and required to carry mountaineering helmets—which the Brazilian victim was not wearing at the time of his death.

This is not the first time a runner has died during the UTMB since the event was founded in 2003. In August 2021, a 35-year-old Czech runner fell to his death during the Sur les Traces des Ducs de Savoie (TDS) race.

Despite the inherent risk involved, approximately 10,000 runners are expected to compete in one of this year’s eight UTMB races, held from August 22-28.

(08/27/2022) ⚡AMPby Runner’s World

Two Promising Updates on Heart Health in Endurance Athletes

There’s encouraging new evidence on artery stiffening and the risks of too much exercise

Reporting on emerging science can sometimes feel like watching live coverage of an ultramarathon. Sure, there’s the occasional dramatic move, but for long stretches of time it feels like nothing is happening. Beneath the surface, though, the action continues. Fatigue mounts, blisters begin to form, an aid station is missed… the evidence gradually accumulates, and only later do we realize when the outcome was settled.

In that spirit, I have a couple of mid-race updates on a topic of longstanding interest: the potential deleterious effects of too much endurance exercise. I’ve been reporting on this controversy for more than a decade now, and summed up the current state of evidence most recently last summer. It would be nice, of course, if we now had final evidence about whether training for marathons or ultramarathons might damage the heart. Instead, it’s become clear that the perfect study is almost impossible to design, because you simply can’t randomize people to spend a few decades either running marathons or lying on the couch. Still, the steady drip of incremental evidence continues, and two new studies fill in some important gaps.

The first one, published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, explores the links between exercise and atherosclerosis, the build-up of plaques that narrow and stiffen your arteries. One way to test for atherosclerosis is to get a coronary artery calcium (CAC) score, which uses a CT scan to assess how much calcium is present in your heart’s arteries. Recent evidence suggests that masters endurance athletes tend to have higher CAC scores than non-athletes, perhaps because of wear and tear from years of pumping all that blood during exercise. That’s not good, because high CAC scores reliably predict an elevated risk of serious and potentially fatal heart problems in the general population.

The good news is that endurance athletes tend to have different plaques compared to non-athletes. The athletes have plaques that are smooth, hard, and unlikely to rupture; the non-athletes have softer plaques that are more likely to break off from the artery wall and block the flow of blood. So there’s a theoretical argument that high CAC scores shouldn’t be considered as much of a problem in athletes as they are in others. But no one has demonstrated that this is how it pans out in the real world.

This is where the new study comes in. A group led by Pin-Ming Liu of Sun Yat-sen University in China analyzed data from a long-running study whose subjects got a baseline CAC test back in 2000 or 2001, a follow-up CAC test five or ten years later, and filled out questionnaires on their exercise habits on at least three different occasions during the study. These repeated measures are crucial, because it can distinguish between those whose CAC scores are high (perhaps simply because of genetic bad luck) and those whose scores are increasing (presumably due to some lifestyle factor such as exercise).

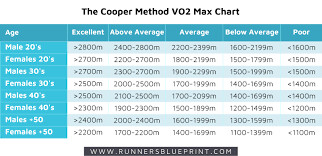

They looked at three groups with a total of about 2,500 subjects: those who consistently did less than the recommended amount of exercise; those who consistently hit or slightly exceeded the recommendations; and those who averaged at least three times the recommendations. In this case, the recommended amount of exercise, based on public health advice, is 150 minutes a week of moderate exercise or 75 minutes a week of vigorous exercise, with activities like running counting as vigorous.

There were two key conclusions. First, the group doing the most exercise was indeed more likely to have an increase in CAC score on their second test, consistent with previous studies. Second, despite their increased CAC scores, the high-exercise group was not more likely to suffer adverse cardiac events during the study’s follow-up. This, too, is consistent with the idea that exercise promotes the formation of plaques, but those plaques don’t carry the same risks as plaques in sedentary people.

This is far from the final word on this topic, in part because only a handful of subjects had exercise levels comparable to those of an elite endurance athlete. But it’s an encouraging sign that CAC scores mean something different in exercisers than they do in non-exercisers.

Debates about CAC scores and other risk factors sometimes feel a bit abstract. The study many of us crave is much simpler: take a bunch of people, find out how much they exercise, and wait to see who dies first. Many such studies have been done, but their results are difficult to interpret because there are so many other differences, beyond exercise habits, between those who choose to run 100 miles a week and those who choose not to run at all.

Despite those caveats, there were two such studies, one from the Cooper Clinic in Texas and the other from Copenhagen, that claimed to see a “reverse J-curve” in the relationship between exercise amount and mortality risk. Doing a little exercise produced a dramatic decrease in your chances of dying early; doing more produced a modest further increase; but doing too much bent the curve back upward and began increasing your risk again.

Numerous other studies have tested the same idea and failed to find evidence that more exercise, beyond a certain point, raises your risk of premature death. But given the imprecisions inherent in this kind of observational data, it’s hard to know which study to trust (especially when you really want a particular conclusion), so I normally wouldn’t report on yet another study finding that too much exercise isn’t bad for you after all.

This one has an interesting twist, though. It’s published in Circulation, by a group led by Dong Hoon Lee of Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and it follows 116,221 adults from the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, beginning in the 1980s. Over the course of 30 years, there were more than 47,000 deaths among the subjects, which means you’re not drawing conclusions on the basis of small numbers. (The Copenhagen study I mentioned above famously suggested that ”strenuous” running raises your risk of premature death on the basis of just two deaths in that group.)

The crucial detail is that subjects in the new study were asked about their exercise habits every two years, instead of just once at the beginning of the study. This allowed the researchers to divide subjects into groups based on their average exercise levels over the course of the study, rather than relying on a single snapshot of exercise habits to deduce someone’s health as much as 30 years later.

The headline result is that those doing 150 to 300 minutes a week of vigorous exercise such as running (or, somewhat equivalently, 300 to 600 minutes a week of moderate exercise such as walking) were about half as likely to die during the study. Even after adjusting for other secondary benefits of exercise like lower body mass index, their risk was still about a quarter less. Note that 300 minutes a week is five hours of running—not a heavy-duty ultramarathon training program, but still a substantial amount of exercise.

As for those doing more than five hours a week, the benefits stayed about the same. At least, they did if you use the average physical activity levels over the course of the study. When the researchers reran the analysis using just the first exercise questionnaire from the 1980s, the reverse J-curve reappeared. There are several problems with relying on a single measure of exercise habits, the researchers point out, including the risk of reverse causation: declining health before the baseline assessment might spur you to do more exercise, leading to the false impression that exercise causes bad health. This is the way nearly all the previous studies of exercise and mortality have been conducted, so the new results may finally explain why a few studies have observed that reverse J.

It’s still too early to declare that years of serious endurance training have no effect on the heart. In fact, it’s clear that training does change the heart—that’s kind of the point—and it wouldn’t be surprising if those changes sometimes end up having negative effects. But the epidemiological evidence continues to accumulate that the overall effects on longevity are either positive or, at worst, neutral. And that doesn’t even take into account how much fun it is.

(08/27/2022) ⚡AMPby Outside

Here’s how kindness will make you a better runner

Renowned ultrarunner, coach and co-author (with his wife, Megan Roche) of The Happy Runner, David Roche has some suggestions about how we can practice kindness and positivity toward others in our running and racing, and he explains why science backs this up.

“Lifting others up can lift you up too,” says Roche. “It’s not just psychological, but in how physiology responds to stress. Uplifting emotions may improve running economy. Affirmations reduce cortisol and stress. Even adaptation processes on the cellular level may be improved by a positive neurophysical context,” he adds.

If that’s not enough for you, know that you’ll also have way more fun; whatever the end result of your race, you’ll look back on the experience with more joy.

Celebrate shared experience

While the running community still has a long way to go in supporting diversity and inclusivity, trails do tend to tear down barriers and bond people. Most of us feel far more comfortable talking to strangers on a trail than we would on a street. If you see someone struggling a little out there, you’ve probably been in that situation yourself, and you have some empathy for them.

That person you stopped to give a salt tablet to mid-race when you noticed them struggling hits the finish-line all smiles and tears, and you’ll feel their success like its you’re own. Roche explains that by building your running community, you will tend to be more process-focused and less results-focused (which was actually, in turn, help you run faster).

Thank every single volunteer and encourage every other runner

If you’ve ever had challenging race, you’ve probably experienced some moments of suffering. Mine, in ultrarunning, often involve struggling to keep enough nutrition in and combat nausea; I find it hard to carry on conversations when I feel that unwell. A much more experienced ultrarunner (who has also combated GI distress) once commented to me that the worse she felt, the more appreciative of the volunteers she tried to be. At first, that seemed unfathomable to me. Be extra thankful when I all I really want to do is cry or throw up?

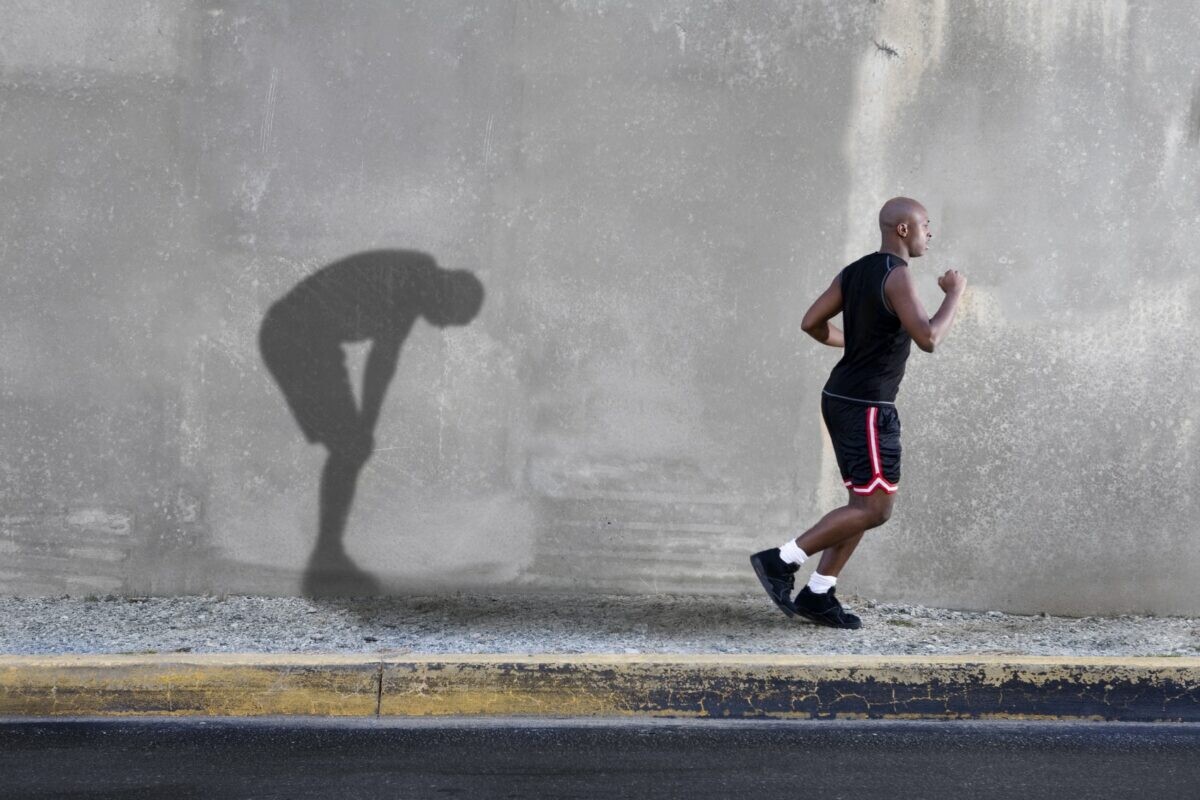

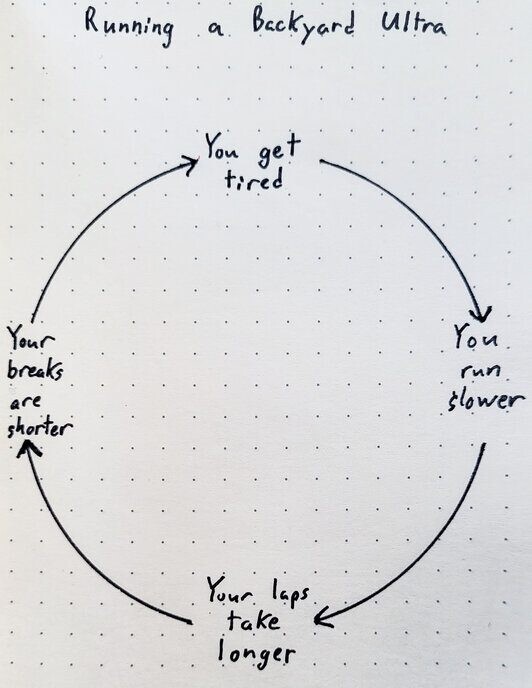

I set out to test this theory when I ran a backyard ultra earlier in 2022. I dedicated myself to asking questions about others when my brain started to spiral into lowness, and to express my gratitude toward my crew and the race volunteers. That day was a certain kind of magic unlike any other I’ve had, and while I’m sure I can’t chalk it up entirely to practicing being nice, it certainly helped.

Roche sums up the concept of being a beacon of cheer when he says: “Spread the freaking love because life is too short and uncertain and scary to spend it alone, withholding affection.” I can’t argue with that. Even if you’re an introvert like me, up your kindness-game next race. You have absolutely nothing to lose by giving it a try.

You don’t have to be perfect at this–no one is. “The goal isn’t to exude an infallible aura of kindness, but to accept yourself and others as much as you can given the constraints of your background, brain chemistry, and perspective,” says Roche.

(08/25/2022) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

One simple trick to master fuelling on the run, Practice, practice, practice: here's how

Practice. If you’re used to simply lacing up your shoes and heading out the door, it can seem like a nuisance to have to consider your meals, snacks, and what nutrients you should be taking in every single time you run. Becoming better at this key skill for any longer-distance race means incorporating it into your training as often as possible. Here’s why, and how to get started.

Experiment with gels and real food

If you’re training for a marathon distance or longer, you should be taking in some form of calories once your weekly long runs are longer than an hour. Regardless of what nutrition plan you follow in your life outside of running, you’ll probably turn to carbohydrates during a race, and for good reason. Simple carbohydrates, often in the form of glucose, are the easiest to digest and will give you an energy boost quickly.

If you’re training for an ultra, depending on the distance, you need to co-ordinate consuming thousands of calories. Gels can be an easy form of simple carbs to take in, but when you’re logging many hours, you may want to turn to real food.

If you have tackled a few long runs, you’ll know that while you might feel hungry, not every type of food will satisfy or sit well in your stomach. Experiment on long runs with foods that appeal to you, and see if you can manage to eat and digest them while running without GI distress. Some runners have no issue eating a sandwich while logging mileage, others will feel sick trying to digest anything of substance. The good news is that you can actually train your gut to handle digesting food better while running; it just takes (you guessed it) practice.

Practice the actual act of managing to eat while running

If you’ve ever volunteered at a marathon or ultra aid station, you have probably noticed people struggling to open gels, drink from little cups, or unscrew the lids on their hydration packs. While some very experienced athletes have their fueling down to a fine art, the vast majority of runners aren’t at their most dextrous during a hard run.

When most of the calories you are consuming are being used to keep your legs moving, your body temperature regulated and your brain functioning enough to keep you on the course, you lose fine motor skills. Practicing eating and drinking on long runs can make a vast difference when it comes to race day.

Learn how your body responds to salt and caffeine

Caffeine can be a very effective stimulant for athletes, but knowing how much and how to use it is unique to each runner. A large body of research has shown that caffeine enhances mental alertness and delays physical fatigue, but it can be tricky to determine how much is ideal for your body and how you prefer to ingest it. Test out gels or drink mixes that contain caffeine, caffeine pills and caffeine chewables to see if you find them effective.

We know that sodium is an essential electrolyte, and salt is one of the thing things the body becomes depleted of most quickly during hard efforts. Salt also contains electrolytes like magnesium, calcium and potassium, so it’s good for more than just sodium replenishment. Experiment with salt pills, chewable salt tablets, or simply add a pinch of salt to some water.

Drink mixes have varying amounts of electrolytes, so be sure to keep track of what you try and what seems effective–hotter days will require more salt to keep your body running smoothly.

While it can seem like one more thing to juggle when you head out to train, making sure you’re keeping track of fuel and experimenting at every opportunity will make you a more wise, prepared and strong athlete. When it comes to fuelling, practice really does make perfect.

(08/24/2022) ⚡AMPby Keeley Milne

How to run every street in your town

Is your training lacking a bit of motivation? Try finding and exploring places you've never run before with CityStrides.

The #RunEveryStreet challenge started organically for runners like Vancouver’s David Papineau, who set out with a pen and paper to run all 1,090 streets in the Vancouver area in 2014. It wasn’t until 2018 that renowned ultrarunner Rickey Gates ran every street in San Francisco over 46 days, which put CityStrides on the map and opened the realm of possibilities for runners like Toronto’s Stephen Peck, who recently did the same thing on his city’s 11,000 streets.

In case you do not know what CityStrides is (i.e. me, six months ago), it’s an Internet open street map software that syncs with MapMyRun, Garmin and Strava, creating a heatmap which shows you how much of a city you’ve run. CityStrides uses the GPS data from the third-party apps and throws all the runs or walks you’ve ever done on a map, giving you a super precise detail of the streets you’ve covered and when you’ve covered them.

When Papineau first uploaded his runs to CityStrides in 2018, he was shocked at how much of Vancouver he still had to cover. “I used to print a map on paper and bring it with me on my run,” says Papineau. “Trying to run every street is like building a house: most runners have covered the main streets and parks (the foundation), and running every street is just filling in the gaps between.”

How to get started?

If you use a third-party app like Strava or Garmin Connect for your training, getting started on CityStrides is easy. Visit the CityStrides website and connect to the third-party app to create your profile within seconds.

The application will automatically create a profile for you and connect all your previous runs and all runs moving forward.

If you are just starting with running, using CityStrides is an easy way to keep yourself motivated. Use your progress as motivation to run every street in your neighbourhood or town. “One of the rewarding things about CityStrides is that you will often see places you would often never go to,” says Papineau.

Papineau said the best way to get started is to get out and do it! “Start with the short runs around your immediate neighbourhood on streets you have not run down, and branch out from there.”

Some techniques Papineau used while completing Vancouver were pre-setting his route on his GPS watch, plus graphing out runs in areas he’s never been. “In grid cities or towns, it’s easy to tackle running every street in a particular neighbourhood since the roads are restricted to parallel and perpendicular directions.”

“I’d travel to an area and write down the streets I needed, then run them,” says Papineau.

“When you start seeing your total completion percentage go up, you almost get this endorphin rush for completing new streets,” he says. “It’s rewarding to see all your hard work documented.”

CityStrides may become an obsession, or you may not like it at all, but at least you get to see and experience new places you’d never see in your own backyard.

(08/24/2022) ⚡AMPby Marley Dickinson

Kilian Jornet and NNormal launch their first trail shoe

Kilian Jornet calls the Kjerag "a shoe that can be used for everything from a VK to a 100-mile race”

The Kjerag [pronounced: sche-rak], a trail running shoe and the first product launched by ultrarunning phenom Killan Jornet’s brand NNormal. The Kjerag is named for a 1,100-metre-high mountain in Norway, which can be conquered by running up challenging trails or tackled via some moderate hiking.

The made-for-everyone versatility of the mountain inspired the name of the shoe, touted as being made for every runner at every level. At 200 g, the Kjerag is a lightweight shoe boasting unique shock absorption and stability, with a stack height of 23.5 mm and a heel-to-toe offset/drop of 6 mm.

The design team at NNormal worked with Jornet to create a shoe that’s made to be versatile enough to switch between road running and scrambling up technical trails.

Jornet explained in a press release on Monday: “Our goal with Kjerag was to find the highest-quality materials, cutting-edge technologies, planet-friendly production processes–the best of everything. Then to bring them together in a shoe that can be used for everything from a VK (vertical kilometer) to a 100-mile race.”

The Kjerag has a generous front volume to provide comfort for runners tackling long races or trekking through hot days. Jornet has been test-driving the shoe throughout the 2022 season. “You forget about them when you run,” he reports. “They follow the natural movement of the foot, which helps prevent muscle fatigue and blisters. The shoes adapt to you.”

The Kjerag has a super-sticky, extra durable Megagrip Vibram sole, with 3.5 mm lugs intended to prioritize speed and allow sensitivity to the terrain. The shoe boasts a “new generation of foam” with its EExpure midsole, sitting in direct contact with your feet via a very thin membrane. “No inner sole means best-possible propulsion and compression, less slippage and fewer blisters,” explains NNormal.

NNormal will be launching a range of apparel and accessories alongside the Kjerag that align with the same principles: lightweight and breathable attire made for both intense and less strenuous activities at every level. All the clothing designs are intended to be both timeless and durable.

A shoe as all-encompassing as the Kjerag is hard to imagine, and it will be interesting to see if regular runners find the trail runner as versatile as NNormal claims it to be.

(08/23/2022) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

This Siberian Yupik Ultrarunner Is Ready To Take On Leadville

Just 170 miles from Russia, Nome, Alaska is perhaps best known as the finish line for the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race. Nome's population is near 3,500, but grows in the summer with an influx of gold dredgers and panners.

Crystal Toolie is a Siberian Yupik ultrarunner from Nome, and is one of five Indigenous runners in this weekend's Life Time Leadville Trail 100 Run presented by La Sportiva. In Nome, Siberian Yupik peoples are from the villages of Gampbell and Savoonga on Saint Lawrence Island (164 miles west), off the coast of Alaska. Even here, they're a relatively small community compared to other Alaska Natives.

Training in Nome harbors unique challenges that develop spades of endurance and strength.

Training in Muskox Country

"It's a very isolated town. This year, we've had a lot more [brown] bears. And we have [musk oxen]," said Toolie. "So if you're a runner and you train outside, you have to be aware of your surroundings." The small but supportive running community in Nome leans on social media to update each other on bear and other wildlife sightings.

"There was one winter when I strictly just ran on the treadmill. It was torturous," said Toolie. "There are other years that no matter what the temperature or if there's a blizzard out, I made sure to get outside and run."

Blizzard conditions are commonplace in remote Alaska, making appropriate gear mandatory. "I would wear regular running shoes but double up on socks and wear cleats, so I don't slip," said Toolie. "Layers, if it's a blizzard. I would wear snow pants and a winter coat. My inner layer will be something that's sweat-wicking, something to cover up my face and hood. Sometimes goggles, sometimes not. And then wear really good gloves."

In addition to layering, Toolie sticks to Nome's limited road system as a safety measure, making it a priority to be visible during runs. Looking to Leadville, she incorporated hiking local mountains into her training.

"This year, I've been able to get out of the road system and get into the mountains, which is great for training for Leadville," said Toolie.

Running Under the Lights

During winter runs, Toolie has nature's headlamp guiding her way. Best seen just outside of the city, the Northern Lights present colorful bands of greens and whites that illuminate the sky. The lights are generated from electrically-charged particles in the earth's magnetosphere colliding with gases, creating energy in the form of light.

Though beautiful, the lights were sometimes frightening to Toolie as a child.

"Our elders would tell us if you're outside late, when you know you're not supposed to be, making noise, the Northern Lights would come down and steal you up," said Toolie. "And so if you whistle or make loud noises, the Northern Lights dance and become more vibrant. It looks like it's coming down."

Nome-St. Lawrence Island Dance Group

Beyond ultrarunning, Toolie is dedicated to preserving the movements of her culture. Several years ago, Toolie reinstated the Indigenous dance group in the area. Toolie's great grandfather, Nick Wongittillin, was the leader of the first Nome dance group, when he passed away, they stopped. "We all wanted our children to be able to learn about our culture, to be able to pass down that tradition," said Toolie.

Composers set the tone on drums (Saguyak) - constructed from tightly stretched walrus stomach linings from the Bering Sea - based on how they're feeling at that moment. The zen-like movements are reminiscent of Qigong from southeast Asia. Toolie and her relatives even have a particular song dedicated by an elder to their running pursuits.

The women wear regalia that is distinguishable from other Alaska Natives in the region. Traditionally, their dress-like garments have three to four red lines sewn at the bottom, symbolic of the Russian Orthodox influence on the culture. The women wear their hair in two braids with beads sewn into them.

The group performs at local events of celebration and mourning, a way to bring the community together. The elders ensure the dances are appropriately conducted so that the integrity of the movements is consistent over time.

Climate Threats and Commercialism