Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #Kilian Jornet

Today's Running News

Kilian Jornet Announces Bold New Ultra-Endurance Challenge

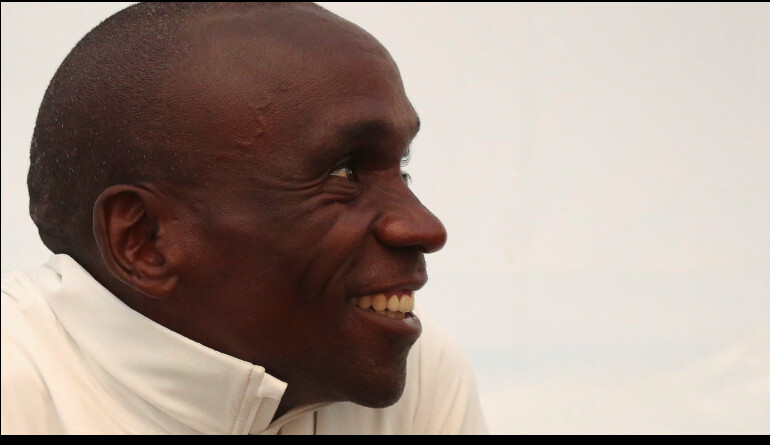

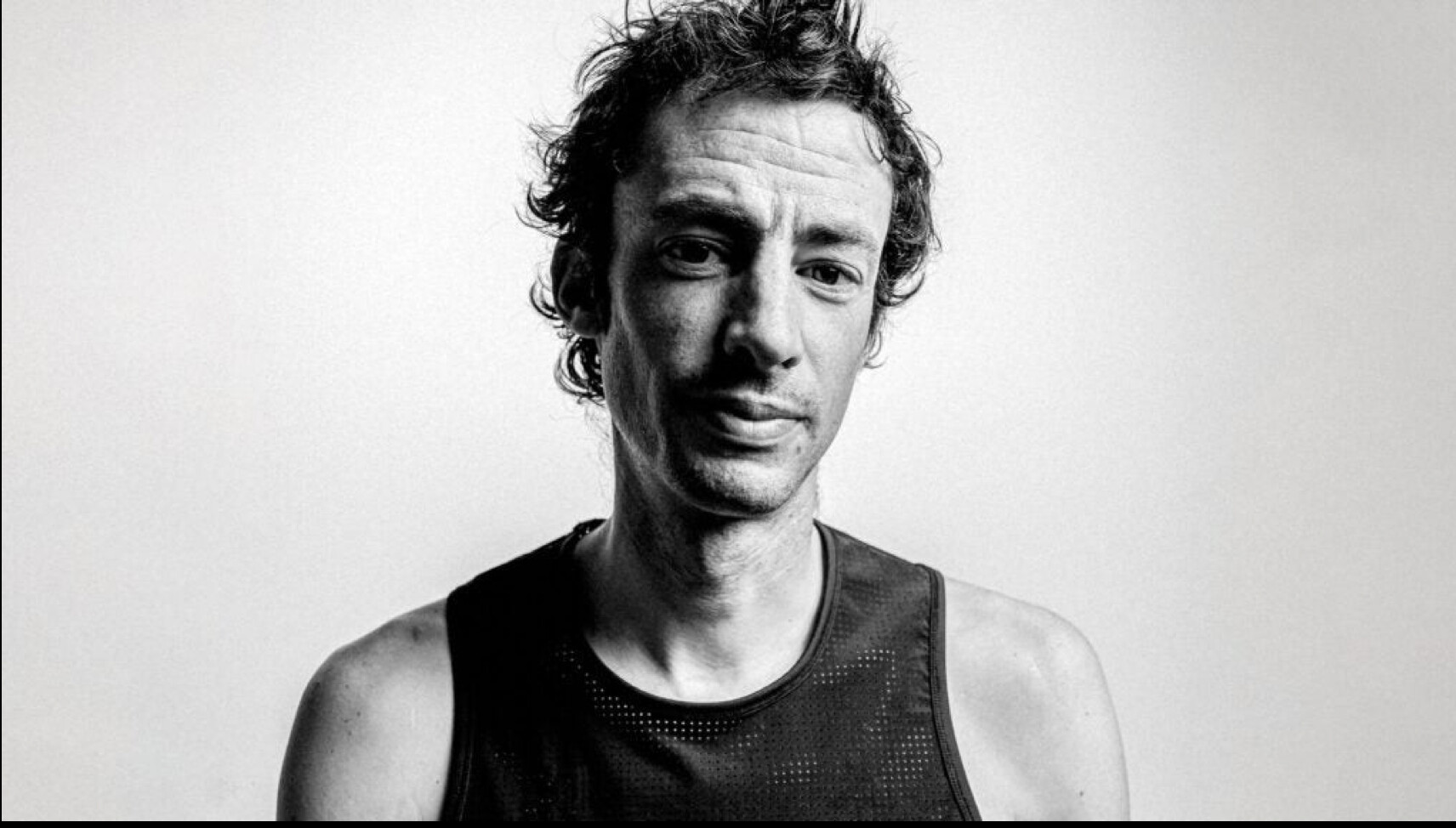

Kilian Jornet, widely regarded as the greatest endurance athlete of all time, has unveiled his most audacious project yet—combining the grit of the Tour de France with the relentless grind of marathon running.

The mountain-running icon plans to summit every 14,000-foot peak in the contiguous United States, linking them all by bicycle and on foot. His concept blends cycling stages on par with the Tour de France and running a marathon each day, all while climbing some of the highest mountains in America.

A New Level of Endurance

Jornet has long redefined the limits of human performance. From setting speed records on Mont Blanc, Everest, and the Matterhorn, to dominating ultramarathons around the globe, his career has blurred the line between mountaineering, cycling, and distance running.

This latest challenge pushes even further—requiring not just peak physical conditioning, but also careful logistics, recovery, and resilience in some of the toughest terrains on earth.

Why This Challenge Matters

The project is more than just an athletic quest. By connecting summits, marathons, and cycling stages into one continuous journey, Jornet is symbolically uniting three of endurance sport’s greatest disciplines. His effort will not only test human possibility but also inspire runners, cyclists, and climbers to think beyond conventional limits.

As Jornet himself has often said, his greatest motivation comes from curiosity—asking what lies beyond the next climb, the next trail, or the next idea of what’s possible.

The Road Ahead

No specific launch date has yet been set, but anticipation across the endurance community is already high. If Jornet succeeds, this could go down as one of the most ambitious endurance projects in modern history—an odyssey across mountains, roads, and trails that only someone like Kilian could attempt.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Caleb Olson Stuns the Field with Breakthrough Win at the 2025 Western States 100

American ultra-trail runner Caleb Olson delivered a career-defining performance at the 2025 Western States Endurance Run, emerging as the surprise champion in what was billed as one of the most competitive editions in the race’s 52-year history.

The 29-year-old from Salt Lake City conquered the infamous 100-mile (161-kilometer) course through Northern California’s rugged Sierra Nevada mountains, finishing in 14 hours, 11 minutes, and 25 seconds—just two minutes shy of Jim Walmsley’s legendary course record set in 2019 (14:09:28). Olson’s time is now the second-fastest ever recorded at Western States.

His win comes just a year after a strong fifth-place finish in 2024 and cements his place among the top ranks of global ultrarunning.

A Battle of Heat, Elevation, and Grit

The race began at 5:00 a.m. in Olympic Valley, with runners quickly climbing to the course’s highest point—2,600 meters (8,600 feet)—before descending into the heat-scorched canyons. Snowfields in the early miles gave way to punishing heat, as temperatures soared to 104°F (40°C) in exposed sections of the trail.

Despite the brutal conditions, approximately 15 elite athletes crested the high point together, setting the stage for a tactical and attritional race. Olson surged to the front midway, clocking an average pace near 12 kilometers per hour and never relinquished his lead.

Elite Field Delivers Drama

Close behind Olson was Chris Myers, who battled stride-for-stride with the eventual winner for much of the race before taking second in 14:17:39. It was a breakthrough performance for Myers, who has been steadily climbing the ultra ranks.

Spanish trail running legend Kilian Jornet, 37, finished third, matching his 2010 result. Returning to Western States for the first time since his win 14 years ago, Jornet hoped to test himself against a new generation on the sport’s fastest trails. Though renowned for his resilience in mountainous terrain, he struggled to match the frontrunners during the course’s hottest sections.

“Western States always finds your limit,” Jornet said post-race. “Today, that limit came earlier than I’d hoped.”

Rising Stars and Withdrawals

Among the elite field was David Roche, one of America’s most promising young ultrarunners, who was forced to withdraw after visibly struggling at the Foresthill aid station (mile 62). Roche had entered the race unbeaten in 100-mile events.

“I’ve never seen him in that kind of state,” said his father, Michael Roche, who was on hand to support him. “This race just takes everything out of you.”

Roche’s exit was a reminder that, even with perfect preparation, the Western States 100 is as much about survival as speed.

The Lottery of Dreams

Held annually since 1974, the Western States Endurance Run is more than a race—it’s a pilgrimage. With only 369 slots available, most runners enter via a lottery system with odds of just 0.04% for first-timers. Elite athletes can bypass the lottery by earning one of the coveted 30 Golden Ticketsawarded at select qualifying races each year.

For many, getting to the start line takes years of qualifying and persistence—making finishing the race an achievement in itself.

Olson’s Star Ascends

Before this landmark win, Caleb Olson was already on the radar of the ultra community. He had logged top-20 finishes at the “CCC”—a 100-kilometer race associated with the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc series—and had demonstrated consistency in major trail events.

Saturday’s victory vaults him into the upper echelon of global ultrarunners and marks a generational shift in the sport.

“I’ve dreamed of this moment,” Olson said at the finish. “Today, everything came together—the training, the heat management, and the belief. This is why we run.”

2025 Western States results

Men

Saturday June 28, 2025 – 100.2 miles

Caleb Olson (USA) – 14:11:25

Chris Myers (USA) – 14:17:39

Kilian Jornet (SPA) – 14:19:22

Jeff Mogavero (USA) – 14:30:11

Dan Jones (NZL) – 14:36:17

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Western States 100

The Western States ® 100-Mile Endurance Run is the world’s oldest and most prestigious 100-mile trail race. Starting in Squaw Valley, California near the site of the 1960 Winter Olympics and ending 100.2 miles later in Auburn, California, Western States, in the decades since its inception in 1974, has come to represent one of the ultimate endurance tests in the...

more...Why Zegama Remains the Most Revered Mountain Marathon

Zegama-Aizkorri 2025: The Mountain Marathon That Defines Grit and Glory

ZEGAMA, SPAIN — On Sunday, May 25, 2025, the world’s most electrifying trail marathon returns to the rugged peaks of the Basque Country. The Zegama-Aizkorri Mountain Marathon, now in its 24th edition, is more than a race—it’s a rite of passage for mountain runners.

Each year, hundreds of elite and amateur athletes are drawn to the small village of Zegama to test themselves on a course that is as breathtaking as it is brutal. With 42.195 kilometers (26.2 miles) of steep, technical terrain and 2,736 meters (8,976 feet) of vertical gain, the challenge is legendary.

A Look Back at 2024: Jornet and Nordskar Shine

In 2024, trail running legend Kilian Jornet claimed his 11th Zegama title, completing the course in 3:38:07, the second-fastest time in the race’s history. The Spaniard’s unmatched mastery of this terrain—where weather, altitude, and technicality collide—continues to amaze.

On the women’s side, Norway’s Sylvia Nordskar delivered a breakthrough performance, winning in 4:29:12. Her victory came after years of chasing a podium finish, cementing her place among the world’s best mountain runners.

What Makes Zegama So Unique?

Zegama's course runs through the Aizkorri-Aratz Natural Park, an untouched alpine landscape of jagged ridges, mossy forests, and sweeping vistas. But it’s not just the scenery that defines Zegama—it’s the intensity of the terrain:

• Brutal Climbs: Runners face punishing ascents like Sancti Spiritu, where fans line both sides of the narrow path, turning the mountain into a human tunnel of noise and encouragement.

• Technical Descents: Slippery rock faces and steep downhills test a runner’s balance and nerve, often under unpredictable weather that can shift from fog to freezing rain in minutes.

• Unmatched Atmosphere: Thousands of passionate Basque fans hike deep into the mountains to cheer with cowbells, flags, and chants. It’s been compared to the Tour de France on foot.

In Zegama, you’re not just running against the clock—you’re running with the crowd, through weather, over stone, and into history.

2025 Expectations

With another stacked field expected for 2025, the stage is set for drama. Can Jornet make it 12 wins? Will Nordskar defend her title? Or will a new name rise through the mist?

One thing is certain: Zegama es Zegama. No other race captures the raw essence of mountain running like this one.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

How Trail Races Are Redefining the Running Boom

In recent years, the global running community has seen a dramatic shift in where and how people race. While traditional road marathons still draw massive crowds, trail races—once considered a niche segment—are experiencing a surge in popularity. From rugged mountain paths to dense forests and desert crossings, more runners are lacing up to compete off-road, seeking challenge, solitude, and a deeper connection to nature.

The Rise of Trail Runnimg

Trail running has grown rapidly in the past decade, but its momentum accelerated after the COVID-19 pandemic, when road races were canceled and people turned to nature for both fitness and sanity. What started as necessity turned into passion for many, and race organizers took note. Events that once attracted a few hundred now sell out in minutes.

Today, races like the UTMB (Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc) in France, the Western States 100 in California, and the Ultra-Trail Cape Town in South Africa are globally recognized—drawing elites and amateur runners alike. These races offer not just distance and competition, but elevation, terrain variety, and breathtaking backdrops.

More Than a Race—A Journey

Unlike a typical 10K or marathon, trail races often require navigation, climbing, and mental fortitude. Weather and terrain can change quickly. Aid stations may be miles apart. But it’s exactly these demands that attract runners hungry for something deeper than just speed or medals.

“There’s something primal about running in the wilderness,” says 2023 UTMB finisher Sara Delgado. “It’s not just about pace—it’s about presence.”

Elite Trail Runners on the Rise

Top road racers are taking notice too. Marathoners like Jim Walmsley and Kilian Jornet have made trail dominance a core part of their legacy. Meanwhile, athletes like Courtney Dauwalter are redefining what endurance looks like, regularly winning 100-mile races overall—not just in the women’s field.

Sponsors have followed the talent. Major brands are investing in trail running gear, shoes, and media coverage, making the sport more visible and viable for elite athletes and growing its appeal for weekend warriors.

Global Appeal

From Portugal’s Douro Valley to the jungles of Costa Rica and the peaks of Japan’s Alps, trail races are being launched in every corner of the world. Many combine local culture with intense landscapes, turning these events into destination experiences.

Travel-based trail running adventures—3-day stage races, run-and-yoga retreats, and culinary trail tours—are also gaining traction. It’s no longer just a race, but a way to see the world, one footstep at a time.

What This Means for the Future

Trail running is redefining the running boom by offering what many road races cannot: quiet, challenge, authenticity, and unfiltered connection to the earth. As the sport continues to grow, it’s likely we’ll see more hybrid athletes, crossover races, and increased visibility across the media.

The road will always have its place, but for a growing number of runners, the real race begins where the pavement ends.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Kilian Jornet is The Laid-Back Legend of the Mountains and Ultramarathons

Kilian Jornet is one of the most decorated endurance athletes in history, yet you wouldn’t know it from speaking with him. He carries his accolades with a shrug and a smile, displaying the kind of calm confidence that comes from years of pushing human limits at extreme altitudes and distances. Whether he’s setting records on towering peaks or dominating the world’s most grueling ultramarathons, Jornet approaches every challenge with an almost playful ease.

Breaking Records in the Mountains

Jornet’s list of accomplishments reads like something out of a mountaineering legend’s biography. He holds the fastest known time (FKT) for ascent and descent of some of the world’s most iconic peaks, including Mont Blanc, the Matterhorn, and Denali. His 24-hour uphill skiing record—a staggering 23,864 meters (78,312 feet) of elevation gain—stands as a testament to his extraordinary endurance.

For Jornet, mountains aren’t just a competitive arena; they are home. Growing up in the Pyrenees, he was introduced to skiing and mountain running at an early age. By his teens, he was already an elite ski mountaineer, but his ambitions stretched far beyond the competition circuit. He set his sights on redefining speed and endurance in the world’s most rugged terrains.

Dominating Ultramarathons

Beyond mountaineering, Jornet has excelled in ultramarathons, often obliterating world-class competition. His wins include victories at:

• Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB) – Arguably the most prestigious ultramarathon in the world, where Jornet has claimed multiple titles.

• Hardrock 100 – He’s won this brutally tough race in Colorado multiple times, including running it with a dislocated shoulder in 2017.

• Western States 100 – A race where his performance cemented his status among the world’s best ultrarunners.

• Zegama-Aizkorri Marathon – A mountain marathon in the Basque Country where he has thrilled fans with record-breaking runs.

Jornet’s dominance is not just about physical strength. His ability to read the mountains, understand his body, and adapt to extreme conditions gives him an almost supernatural edge.

The Mindset of a Champion

Despite his mind-blowing achievements, Jornet remains humble. When asked about his records, he often downplays them, focusing instead on the experience rather than the numbers. His approach to training is unconventional by traditional standards—he listens to his body, adapts his workouts based on how he feels, and prefers to spend as much time as possible in the mountains rather than following rigid training plans.

This laid-back mindset might seem at odds with his high-performance results, but it’s exactly what makes him great. He thrives in uncertainty, adapting in real time and trusting his instincts rather than fixating on data.

Looking Ahead

Jornet continues to push boundaries, not just in racing but in exploring human potential in extreme environments. His recent projects have included minimalist alpine expeditions and self-supported endurance challenges rather than traditional competitions. He is also an advocate for environmental sustainability, working to preserve the mountains he loves.

At 36 years old, Jornet is still redefining what’s possible in endurance sports. Whether he’s racing, breaking records, or simply enjoying a day in the mountains, he remains one of the most inspiring athletes the world has ever seen.

For those who dream of reaching their own endurance goals, there’s a lesson to be learned from Jornet: approach every challenge with passion, stay adaptable, and never lose sight of the joy that brought you to the sport in the first place.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Camille Herron and the Wikipedia Controversy: Integrity in Ultrarunning Under Scrutiny

Update: after reading our article Camille sent this to MBR "Individuals are violating World Athletic rules and publicly claiming they broke my records. It’s undermining the integrity of the sport and devaluing those who adhere to the rules and the ratified record holders, including me.

I hope Yiannis’s statement provides added clarity who’s behind the push to disregard the rules and retaliated against me."

Camille Herron recently addressed the Wikipedia controversy on her Facebook page, expressing her commitment to fairness and accountability in ultrarunning. She acknowledged the challenges of speaking up about rules and technicalities, noting that it can lead to retaliation.

Herron emphasized that the International Association of Ultrarunners (IAU) has validated her concerns twice, confirming that she continues to hold the IAU World Records and World Bests for 48 Hours and 6 Days. She concluded by thanking her supporters and reaffirming her dedication to integrity in the sport.

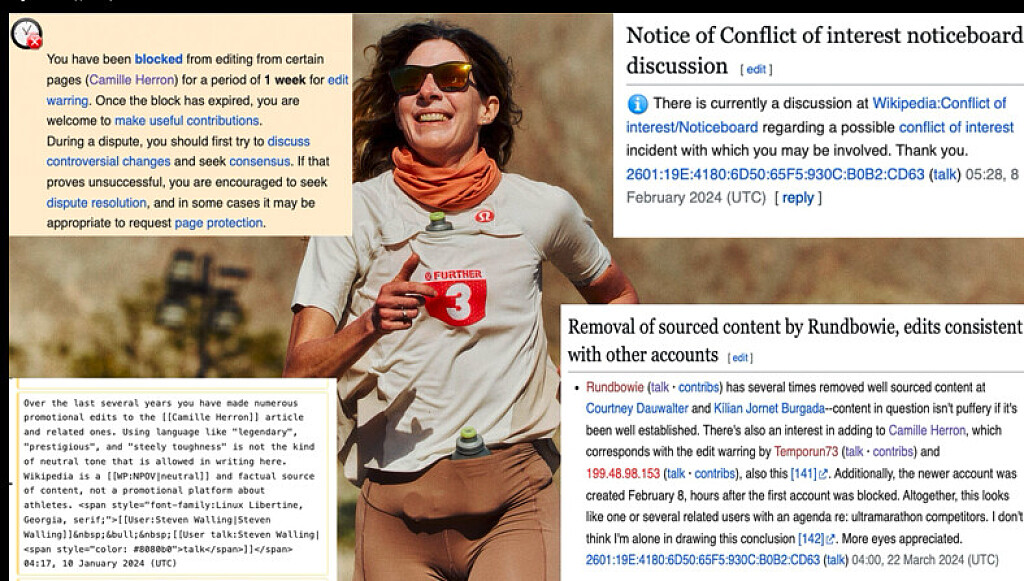

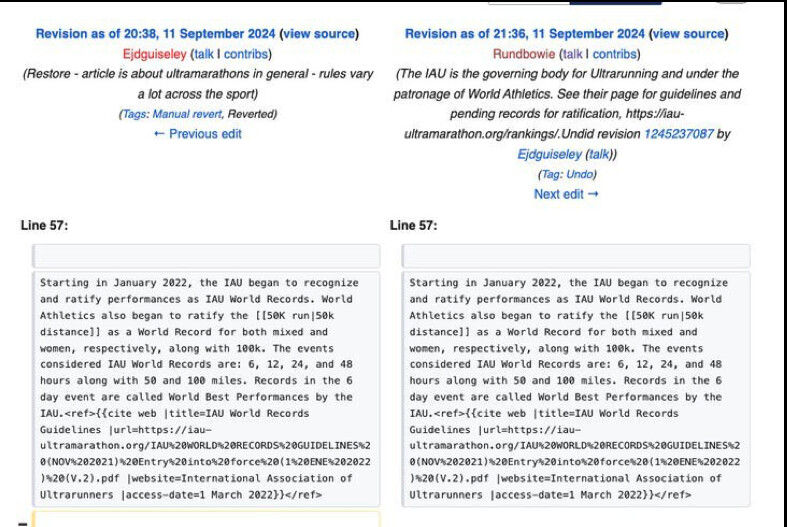

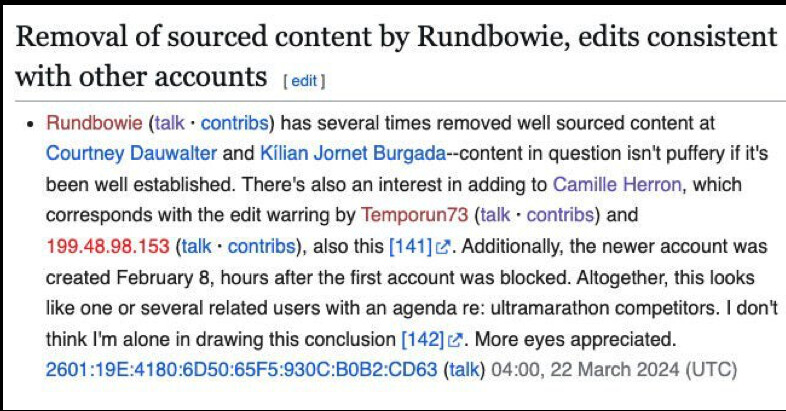

In September 2024, the ultrarunning community was shaken by a controversy involving American ultrarunner Camille Herron and her husband and coach, Conor Holt. The couple was accused of editing Wikipedia pages to enhance Herron's achievements while diminishing those of her competitors.

An investigation by Canadian Running revealed that two Wikipedia accounts, "Temporun73" and "Rundbowie," were linked to Herron's email and Holt's IP address. These accounts made numerous edits to Herron's page, amplifying her accomplishments, and altered the pages of fellow ultrarunners, including Courtney Dauwalter and Kilian Jornet, to downplay their achievements. For instance, statements like "widely regarded as one of the best trail runners ever" were removed from competitors' pages, while Herron was described as "widely regarded as one of the greatest ultramarathon runners of all time."

Following the exposure of these activities, Herron's primary sponsor, Lululemon, terminated their partnership with her. In a statement, the company emphasized its commitment to equitable competition and stated, "After careful consideration and conversation, we have decided to end our ambassador partnership with Camille."

In response to the allegations, Holt took full responsibility, stating, "Camille had nothing to do with this. I'm 100 percent responsible and apologize [to] any athletes affected by this and the wrong I did." He explained that his actions were an attempt to protect Herron from online harassment and bullying that had adversely affected her mental health.

The incident has sparked widespread discussion within the ultrarunning community, with many expressing disappointment over the unsportsmanlike behavior. Herron, known for her numerous world records and contributions to the sport, now faces challenges in rebuilding trust and credibility within the community.

As the situation unfolds, it serves as a reminder of the importance of integrity and sportsmanship in athletics. The ultrarunning community continues to reflect on the implications of this controversy and the lessons to be learned moving forward.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

The Distance Running Scene in 2024: A Year of Remarkable Achievements

The global distance running scene in 2024 was marked by incredible performances, new records, and innovative approaches to training and competition. From marathons in bustling city streets to ultramarathons through rugged terrains, the year showcased the resilience, determination, and evolution of athletes from all corners of the globe.

The World Marathon Majors—Tokyo, Boston, London, Berlin, Chicago, and New York—continued to be the centerpiece of elite distance running, each event contributing to a year of unprecedented performances and milestones.

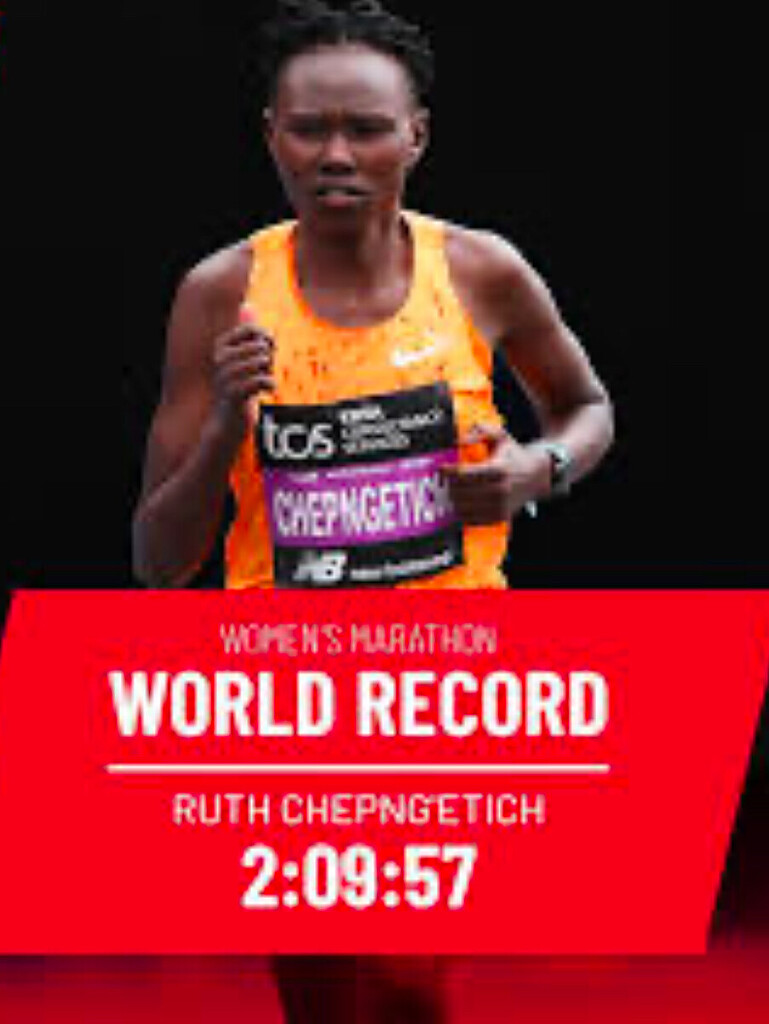

Tokyo Marathon witnessed a remarkable performance by Kenya's Ruth Chepngetich, who set a new women's marathon world record with a time of 2:11:24. This achievement sparked discussions about the rapid advancements in women's long-distance running and the influence of technology in the sport.

In the Boston Marathon, Ethiopia's Amane Beriso delivered a dominant performance, winning in 2:18:01. On the men's side, Kenya's Evans Chebet defended his title, highlighting Boston's reputation for tactical racing over sheer speed.

London Marathon saw Ethiopia's Tamirat Tola take the men's crown, besting the field with a strong tactical race. Eliud Kipchoge, despite high expectations, did not claim victory, signaling the growing competitiveness at the top of men’s marathoning. On the women's side, Kenya's Peres Jepchirchir triumphed, adding another major victory to her impressive resume.

The Berlin Marathon in 2024 showcased yet another extraordinary performance on its fast course, though it was Kelvin Kiptum’s world record from the 2023 Chicago Marathon (2:00:35) that remained untouched. In 2024, Berlin hosted strong fields but no records, leaving Kiptum’s achievement as the defining benchmark for men’s marathoning.

The Chicago Marathon was the highlight of the year, where Kenya's Ruth Chepngetich made history by becoming the first woman to run a marathon in under 2:10. She shattered the previous world record by nearly two minutes, finishing in 2:09:56. This groundbreaking achievement redefined the possibilities in women's distance running and underscored the remarkable progress in 2024.

The New York City Marathon showcased the depth of talent in American distance running, with emerging athletes achieving podium finishes and signaling a resurgence on the global stage.

Each marathon in 2024 was marked by extraordinary performances, with athletes pushing the boundaries of human endurance and setting new benchmarks in the sport.

Olympic Preparations: Paris 2024 Looms Large

With the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris just around the corner, many athletes used the year to fine-tune their preparations. Qualifying events across the globe witnessed fierce competition as runners vied for spots on their national teams.

Countries like Kenya, Ethiopia, Japan, and the United States showcased their depth, with surprising performances by athletes who emerged as dark horses. Japan’s marathon team, bolstered by its rigorous national selection process, entered the Olympic year as a force to be reckoned with, particularly in the men's race.

Ultramarathons: The Rise of the 100-Mile Phenomenon

The ultramarathon scene continued to grow in popularity, with races like the Western States 100, UTMB (Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc), and Leadville 100 drawing record participation and attention.

Courtney Dauwalter, already a legend in the sport, extended her dominance with wins at both UTMB and the Western States 100, solidifying her reputation as the GOAT (Greatest of All Time) in ultrarunning.

On the men’s side, Spain’s Kilian Jornet returned to form after an injury-plagued 2023, capturing his fifth UTMB title. His performance was a masterclass in pacing and strategy, showcasing why he remains a fan favorite.

Notably, ultramarathons saw increased participation from younger runners and athletes transitioning from shorter distances. This shift signaled a growing interest in endurance challenges beyond the marathon.

Track and Road Records: Pushing the Limits

The year 2024 witnessed groundbreaking performances on both track and road, with athletes shattering previous records and setting new benchmarks in distance running.

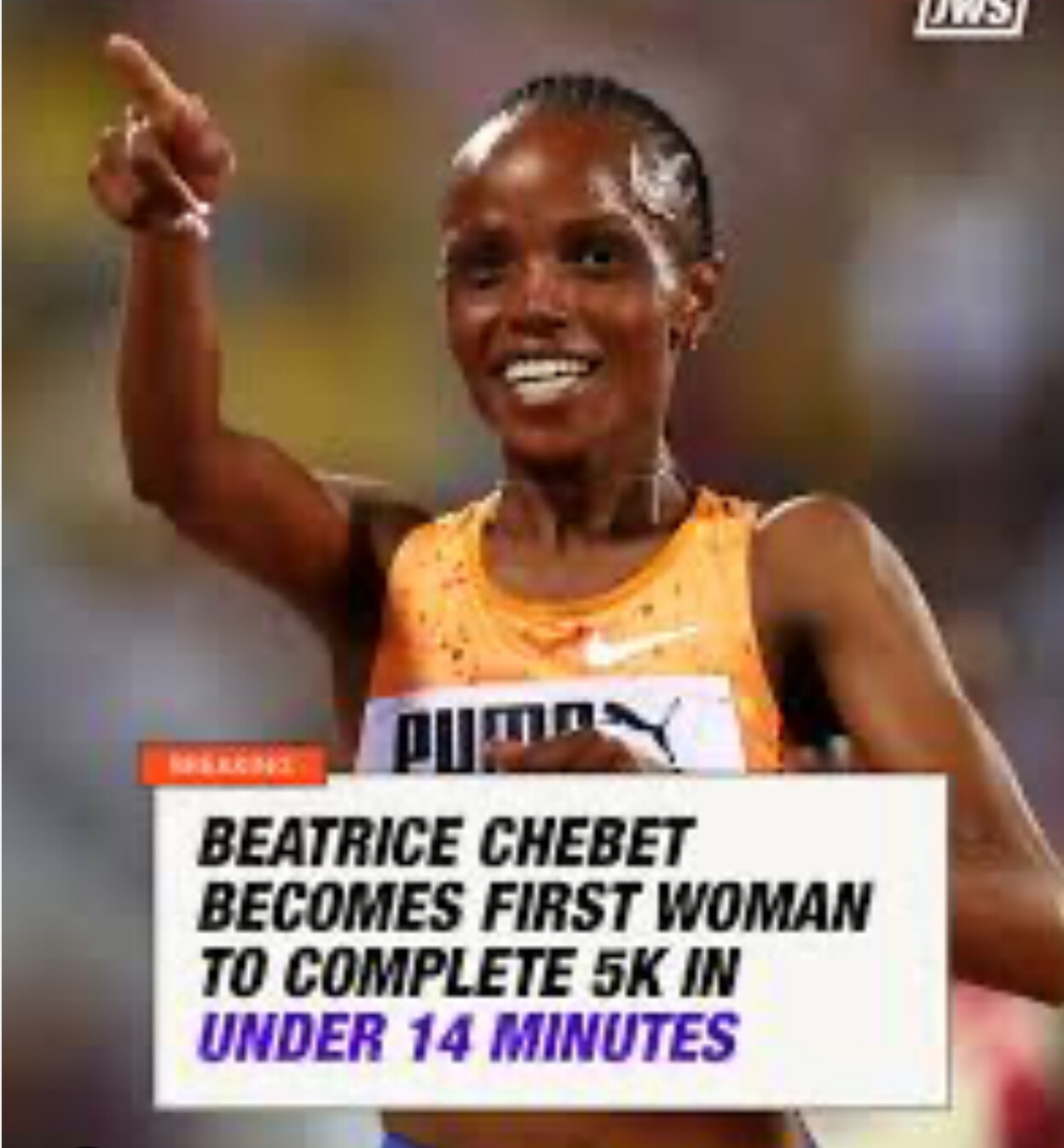

Beatrice Chebet's Dominance: Kenya's Beatrice Chebet had an exceptional year, marked by multiple world records and championship titles.

10,000m World Record: In May, at the Prefontaine Classic, Chebet broke the women's 10,000m world record, becoming the first woman to run the distance in under 29 minutes, finishing in 28:54.14.

Olympic Triumphs: At the Paris Olympics, Chebet secured gold in both the 5,000m and 10,000m events, showcasing her versatility and dominance across distances.

5km World Record: Capping off her stellar year, on December 31, 2024, Chebet set a new women's 5km world record at the Cursa dels Nassos race in Barcelona, finishing in 13:54. This achievement made her the first woman to complete the 5km distance in under 14 minutes, breaking her previous record by 19 seconds.

Faith Kipyegon's Excellence: Kenya's Faith Kipyegon continued her dominance in middle-distance running by breaking the world records in the 1500m and mile events, further cementing her legacy as one of the greatest athletes in history.

Joshua Cheptegei's 10,000m World Record: Uganda's Joshua Cheptegei reclaimed the men's 10,000m world record with a blistering time of 26:09.32, a testament to his relentless pursuit of excellence.

Half Marathon Records: The half marathon saw an explosion of fast times, with Ethiopia’s Yomif Kejelchabreaking the men's world record, running 57:29 in Valencia. The women's record also fell, with Kenya’s Letesenbet Gidey clocking 1:02:35 in Copenhagen.

These achievements highlight the relentless pursuit of excellence by distance runners worldwide, continually pushing the boundaries of human performance.

The Role of Technology and Science

The impact of technology and sports science on distance running cannot be overstated in 2024. Advances in carbon-plated shoes, fueling strategies, and recovery protocols have continued to push the boundaries of human performance.

The debate over the fairness of super shoes reached new heights, with critics arguing that they provide an unfair advantage. However, proponents emphasized that such innovations are part of the natural evolution of sports equipment.

Data analytics and personalized training plans became the norm for elite runners. Wearable technology, including advanced GPS watches and heart rate monitors, allowed athletes and coaches to fine-tune training like never before.

Grassroots Running and Mass Participation

While elite performances stole the headlines, 2024 was also a banner year for grassroots running and mass participation events. After years of pandemic disruptions, global races saw record numbers of recreational runners.

Events like the Great North Run in the UK and the Marine Corps Marathon in the U.S. celebrated inclusivity, with participants from diverse backgrounds and abilities.

The popularity of running as a mental health outlet and community-building activity grew. Initiatives like parkrunand local running clubs played a pivotal role in introducing more people to the sport.

Diversity and Representation

Diversity and representation became central themes in distance running in 2024. Efforts to make the sport more inclusive saw tangible results:

More women and runners from underrepresented communities participated in major events. Notably, the Abbott World Marathon Majors launched a program to support female marathoners from emerging nations.

Trail and ultrarunning communities embraced initiatives to make races more accessible to runners from diverse cultural and economic backgrounds.

Challenges and Controversies

Despite the many successes, 2024 was not without its challenges:

Doping Scandals: A few high-profile doping cases marred the sport, reigniting calls for stricter testing protocols and greater transparency.

Climate Change: Extreme weather conditions impacted several races, including the Boston Marathon, which experienced unusually warm temperatures. Organizers are increasingly focusing on sustainability and adapting to climate-related challenges.

Looking Ahead to 2025

As the year closes, the focus shifts to 2025, which promises to build on the momentum of 2024. Key storylines include:

The quest for a sub-2-hour marathon in a record-eligible race, with Kelvin Kiptum and Eliud Kipchoge at the forefront.

The continued growth of ultrarunning, with new records likely to fall as more athletes take up the challenge.

The evolution of distance running as a global sport, with greater inclusivity and innovation shaping its future.

Conclusion

The distance running scene in 2024 was a celebration of human potential, resilience, and the unyielding pursuit of greatness. From record-breaking marathons to grueling ultramarathons, the year reminded us of the universal appeal of running. As the sport evolves, it continues to inspire millions worldwide, proving that the spirit of running transcends borders, ages, and abilities.

by Boris

Login to leave a comment

Is baking soda your next great fuelling tool?

You’re gearing up for a tough workout, and instead of grabbing your usual electrolyte drink, you’re reaching for… baking soda? It might sound like a kitchen hack gone wrong, but many endurance athletes swear by this household staple for improving performance (and the hydrogel company Maurten created an expensive product around it–more on that, below). Here’s what you need to know to help you decide whether this idea is half-baked, or if it’s the key to your next PB.

The science of sodium bicarbonate

Baking soda, or sodium bicarbonate (“bicarb” for short), has been studied for its ability to act as a buffering agent. During intense exercise, like a tempo run or hill repeats, your muscles produce lactic acid, which contributes to that dreaded “burn.” As lactic acid builds up, your muscle function declines. Sodium bicarbonate can help buffer this acid, delaying fatigue and potentially allowing you to sustain your effort for longer periods. A wide range of studies show that athletes who consume baking soda before high-intensity efforts may experience improved performance. But can it help you on those longer-distance runs? While more research is needed, some studies suggest that sodium bicarbonate might boost post-exercise recovery, with other research suggesting it may help runners speed up, even after hours of training.

Swedish sports nutrition company Maurten has created a hydrogel formula for runners that some athletes, like mountain athlete Kilian Jornet and world 5,000m and 10,000m record holder Joshua Cheptegei, swear by. Runners new to using sodium bicarbonate can adjust the hydrogel and bicarb components according to their weight and training needs.

Does it really work?

While there’s some solid science backing baking soda’s benefits, it’s not ideal for every runner. Most of the performance gains have been noted in shorter events, typically lasting between one to seven minutes of all-out effort. For distance runners, like those training for marathons or half-marathons, the impact may not be as pronounced. However, if you’re into track events or HIIT workouts, this kitchen staple could give you an easy-on-the-budget boost. The key is proper dosing (around 0.2 to 0.3 grams per kilogram of body weight) and timing–it should be taken 60 to 90 minutes before your workout or race.

Beware of side effects

Before you go dumping a spoonful of baking soda into your water bottle, be aware: it comes with potential side effects, the most common being gastrointestinal distress. Bloating, cramping or even diarrhea are possible, especially if you take too much or don’t properly dissolve it in water. If you’re interested in trying baking soda for a performance boost, make sure to test it out during training before a big race day, to avoid any unpleasant surprises mid-run.

by Keeley Milne

Login to leave a comment

The Strange Saga of Ultrarunner Camille Herron and Wikipedia

The husband of runner Camille Herron admitted to having altered the Wikipedia biographies of prominent ultrarunners. The revelation came after a Canadian journalist launched an investigation.

On September 24, Conor Holt, the husband and coach of American ultrarunner Camille Herron, admitted to altering the biographies of Herron, Courtney Dauwalter, Kilian Jornet, and other prominent runners on the website Wikipedia. Holt’s edits boosted his wife’s accolades but also downgraded those of the other prominent ultrarunners.

“Camille had nothing to do with this,” Holt wrote in an email sent to Outside and several running media websites. “I’m 100 percent responsible and apologize [to] any athletes affected by this and the wrong I did.”

The confession brought some clarity to an Internet mystery that embroiled the running community for several days and sparked a flurry of chatter on social media and running forums. Herron, 42, is one of the most visible ultrarunners in the sport, and over the years she has won South Africa’s Comrades Marathon and also held world records in several different events, including the 48-hour and six-day durations. But the Wikipedia controversy led to swift consequences for Herron—her major sponsor, Lululemon, parted ways with her on Thursday morning.

The entire ordeal sprung from an investigation led by a Canadian journalist who spent more than a week following digital breadcrumbs on dark corners of

Marley Dickinson, a reporter for the website Canadian Running, began looking into the Wikipedia controversy in mid-September after receiving a tip from someone in the running community. The tipster told Dickinson, 29, that someone was attempting to delete important data from the Wikipedia entry for “Ultramarathon.”

The person had erased the accomplishments of a Danish runner named Stine Rex, who in 2024 broke two long-distance running records—the six-day and 48-hour marks—which were previously held by Herron. At the time, the sport’s governing body, the International Association of Ultrarunners, was deciding whether or not to honor Rex’s six-day record of 567 miles.

“The person making the edits said the IAU had made a decision on the record, even though they hadn’t yet,” Dickinson told me. “Whoever was doing it really wanted to get Rex’s run off of Wikipedia.”

Wikipedia allows anonymous users to edit entries, but it logs these changes in a public forum and shows which user accounts made them. After an edit is made, a team of volunteer moderators, known as Wikipedians, examines the changes and then decides whether or not to publish them. The site requires content to be verifiable through published and reliable sources, and it asks that information be presented in a neutral manner, without opinion or bias. The site can warn or even suspend a user for making edits that do not adhere to these standards.

Dickinson, who worked in database marketing at Thomson Reuters before joining Canadian Running, was intrigued by the bizarre edits. “I’ve always been into looking at the backend of websites,” he told me. “There’s usually a way you can tie an account back to a person.”

The editor in question used the name “Rundbowie,” and Dickinson saw that the account had also made numerous changes to Herron’s biography. Most of these edits were to insert glowing comments into the text. “I thought whoever this person is, they are a big fan of Camille Herron,” Dickinson said.

Rundbowie was prolific on Wikipedia, and made frequent tweaks and updates to other biographies. The account had removed language from the pages of Jornet and Dauwalter—specifically deleting the text “widely regarded as one of the greatest ultramarathon runners of all time.” Rundbowie had then attempted to add this exact language to Herron’s page. Both attempts were eventually denied by Wikipedians.

After examining the edits, Dickinson began to suspect that Rundbowie was operated by either Herron or Holt. Further digital sleuthing bolstered this opinion. He saw that the Rundbowie account, which made almost daily edits between February and April, abruptly went silent between March 6-12. Those dates corresponded with Herron’s world-record run in a six-day race put on by Lululemon in California.

But Dickinson wasn’t done with his detective work. He saw that in March, Wikipedia had warned Rundbowie on its public Incident Report page. The reason

A final Internet deep dive convinced Dickinson that he was on the right track. The IP address—a string of characters associated with a given computer—placed Temporun73 in Oklahoma, which is where Herron and Holt live. Then, on a forum page for Oregon State University, which is where Herron attended graduate school, Dickinson found an old Yahoo email address used by Herron. The email name: Temporun73.

“To me, this was a clear sign that it was either Conor or Camille” Dickinson said.

Dickinson published his story to Canadian Running on Monday, September 23. The piece included screenshots of Wikipedia edits as well as Dickinson’s trail to Herron and Holt. It started off a flurry of online reactions.

A thread on the running forum LetsRun generated 360 comments, and several hundred more appeared on the Reddit communities for trail running and ultrarunning. Film My Run, a British YouTube site, uploaded an immediate reaction video the following day. Within 12 hours, more than a hundred people shared their thoughts in the comments section.

It’s understandable why. Lauded for her accolades in ultra-distance races, Herron is also one of the most visible ultrarunners on the planet. She gives frequent interviews, and has been an outspoken advocate for the anti-doping movement, for smart and responsible training habits, and for the advancement of women runners.

“I think we’re going to continue to see barriers being broken and bars raised. I want to see how close I can get to the men’s world records, or even exceed a men’s world record,” she told Outside Run in 2023.

Herron has also spoken and written about her own mental health. Earlier this year, she began writing and giving interviews about her recent diagnosis with Autism and ADHD.

“Although I knew little about autism before seeking out a diagnosis, my husband, who observed my daily quirks and often reminded me to eat, drink, and go to bed, would jokingly speculate that I might be autistic,” she told writer Sandra Rose Salathe on the website FloSpace in July.

Dickinson told me he had a very positive image of Herron from his short time at Canadian Running. He joined the website in 2021.

“She’s always been super nice and welcoming,” Dickinson said.

Dickinson says he reached out to Herron and Holt via email and social media, but did not receive a reply. On Monday afternoon, a user on the social media platform X asked Herron about the story. “It’s made up,” Herron’s account replied. “Someone has an ax to grind and is bullying and harassing me.”

Herron’s social media accounts were deactivated shortly afterward—Holt later said he took them down.

Some online commenters questioned if the story was legitimate—something I did too, initially. Following Dickinson’s arcane trail through Wikipedia’s backend required a careful read, and a strong knowledge of the encyclopedia’s rules and regulations.

After speaking to Dickinson, I sent my notes to a Wikipedia expert named Rhiannon Ruff, who operates a digital consulting firm called Lumino that helps clients navigate the online encyclopedia. Ruff examined the story as well as the Wikipedia histories of Rundbowie and Temporun 73, and said that the evidence strongly suggested that both accounts were operated by the same person. But, since Wikipedia allows for anonymity, you cannot make the connection with 100 percent certainty.

Ruff pointed out that Wikipedia’s internal editors strongly believed the two accounts had a biased with Herron, because the accounts had attempted to write in the same sentence. “Both tried to add details about her crediting the influence of her father and grandfather, and how she runs with a smile,” Ruff said.

Ruff also pointed me to the prolific editing history of Temporun73. Started in 2016, the account had made approximately 250 edits to

“I never got a chance to say anything to the Canadian Running website before they published it,” Holt wrote.

Holt admitted that he was the operator of the Temporun73 and Rundbowie accounts. But he said his Wikipedia editing was aimed at combating online bullies who had removed biographical details from Herron’s Wikipedia page in the past.

“I kept adding back in the details, and then they blocked my account in early February of this year,” Holt wrote. “Nothing was out of line with what other athletes have on their pages. Wikipedia allows the creation of another account, so I created a new account Rundbowie. I was going off what other athletes had on their pages using the username Rundbowie and copying/pasting this info.”

“I was only trying to protect Camille from the constant bullying, harassment and accusations she has endured in her running career, which has severely impacted her mental health,” he added. “So much to the point that she has sought professional mental health help.”

Outside asked Holt via email to provide further details, but we did not receive a response. In an email to Canadian Running, Holt said he was focused on Herron’s upcoming race, and would not be conducting interviews.

But the fallout from the admission came quickly. On Thursday morning Dickinson broke more news: apparel brand Lululemon, which has backed Herron since 2023, had ended its partnership. In a statement provided to several outlets, the brand said it was dedicated “to equitable competition in sport for all,” and that it sought

by Outside Online

Login to leave a comment

Kilian Jornet summits 82 Alpine peaks in 19 days

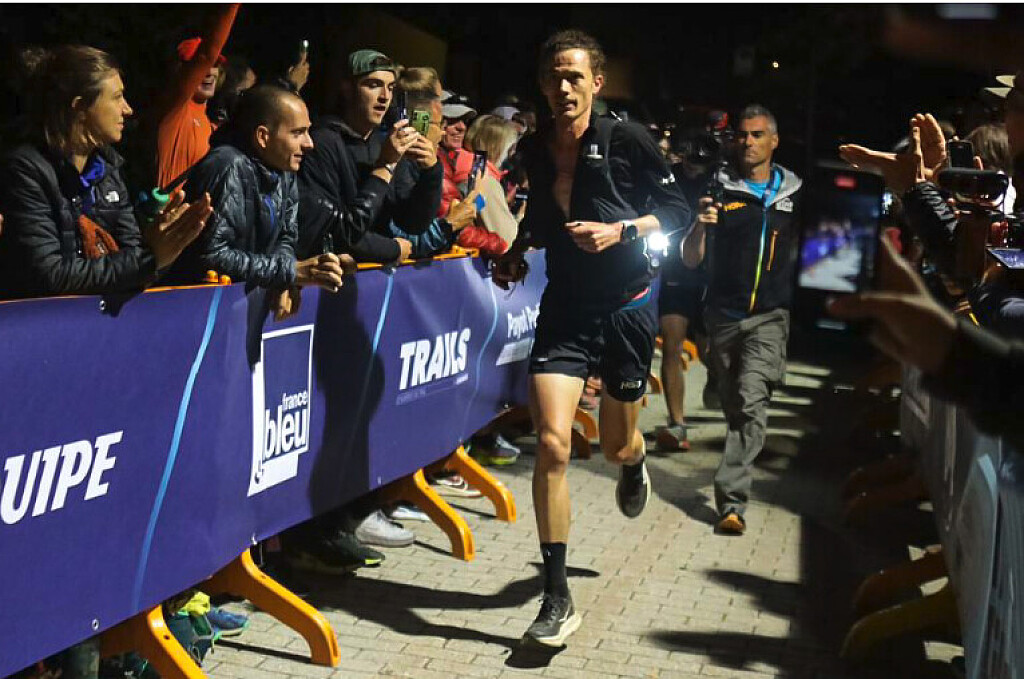

On Monday, Spain’s Kilian Jornet, four-time UTMB champion and a legend in ski mountaineering and climbing, completed his monumental mountain challenge to summit all 82 Alpine peaks over 4,000m high in only 19 days. Jornet shattered the previous Fastest Known Time (FKT) of 62 days, set in 2015 by Swiss alpinist Ueli Steck, who used a combination of cycling and paragliding.

Following his remarkable 10th victory at the Sierre-Zinal race (where he beat his own course record by a single second), Jornet embarked on a quest, dubbed “Alpine Connections,” to ascend as many of the 4,000-metre peaks in the Alps as possible, using only human-powered methods to travel between them. This endeavour seamlessly combined trail running, mountaineering, climbing and cycling.

In 2023, Jornet took on his toughest challenges yet, summiting all 177 peaks over 3,000 metres in the Pyrenees in just eight days. Reflecting on the feat at the time, he called it “one of the most difficult things I’ve ever done.” With the “Alpine Connections” project, Jornet pushed his limits even further as he continued to use only running or cycling between mountains, being careful to leave no trace that he was there.

Jornet started his journey in the Bernina range of eastern Switzerland. In just a few days, he conquered 10 peaks, covering 423 km with a staggering 19,831m of elevation gain. The early stages of the challenge tested both his physical and mental endurance, and Jornet worked closely with scientists to track the physical and mental demands of his trek. He also provided daily recaps, stats and tracking on the Nnormal blog, Strava and @nnormal_official.

Jornet faced other, more humourous challenges during his journey: at one point, police threatened to tow his vehicle when work needed to be done on the parking lot he had left it in—2,500km away, and 4,000 metres below him.

Upon reaching the summits of Dôme and Barre des Écrins (the westernmost peaks in the series) on Instagram, Jornet shared his thoughts on Instagram. “This was, without any doubt, the most challenging thing I’ve ever done in my life, mentally, physically, and technically, but also maybe the most beautiful.”

“It’s difficult to process all my emotions just now, but this is a journey that I will never forget. It’s time for a bit of rest now.”

by Keeley Milne

Login to leave a comment

UTMB Is Having a Golden Moment. But It’s Delicate.

After a year that included a maelstrom of controversy, the world’s most prominent ultra-trail running event has righted its path

“It felt like a golden era of trail running.”

That quote came from Keith Byrne, a senior manager at The North Face and a UTMB live stream commentator for nearly a decade, who was talking about last summer’s UTMB World Series Finals in Chamonix, France.

The UTMB races during the last week of August last summer were, I thought, the most alluring in the event’s 20-year history.

After years of being frustrated by the course, American Jim Walmsley finally put it all together for a victorious lap around Mont Blanc. In doing so he became the first U.S. man to win the race, setting a course record of 19:37:43. He and his wife, Jess, had moved from Arizona to live full-time in France to make it happen. And then there was Colorado’s Courtney Dauwalter, who won the race handily in 23:29:14 to notch her third victory and continue the strong legacy of American women on the course. The win felt extra historic because it made her the first person to win Western States, Hardrock, and UTMB in the same year—arguably the three most legendary and competitive 100-mile events in the world, and she dominated each one.

The events came off without a hitch and included record crowds in Chamonix, plus a record 52 million more tuning into the livestream.

Throughout the fall and winter, harmony and happiness seemed to give way to chaos and discontent. But a year later, as the UTMB Mont Blanc weeklong festival of trail running kicks off on August 26, everything seems back to normal in Chamonix. What happened along the way is a tale of drama, perhaps both necessary and unnecessary, all of it culminating in course corrections by the multinational race series.

In short, what a year it has been for UTMB.

And now, hordes of nervous and excited runners from all corners of the globe are descending on Chamonix for this year’s UTMB Mont-Blanc races. Registration for UTMB World Series events is reportedly up about 35 percent year over year with even greater growth in interest for OCC, CCC and UTMB race lottery applications. There is more media coverage, more pre-race hype, and more excitement than ever before. More running brands are using the UTMB Mont Blanc week to showcase their new running gear with media events, brand activations, and fun runs. Even The Speed Project—although entirely unrelated to UTMB—chose Chamonix as the starting point of its latest so-called underground point-to-point relay race to try to catch some of the considerable buzz UTMB is generating.

So what happened? Did the UTMB organization do its due diligence and make amends with several significant changes in the spring? Was the angst and stirring of emotions just not as widely felt as the fervent bouts of Instagram activism claimed it to be? Have the participants and fans of the ultra-trail running world suffered amnesia or become ambivalent? Or is it all a sign of the race—and the entire sport of trail running—going through growing pains as it adjusts to the massive global participation surge, increased professionalism, and heightened sponsorship opportunities?

On the eve of another 106-mile lap around the Mont Blanc massif, I wanted to take a look at what happened and the current state of UTMB’s global race series that culminates here in Chamonix this week.

We caught a glimpse of what was to come shortly before UTMB last year, when the race organization announced the European car company Dacia as its new title sponsor. A fossil-fuel powered conglomerate didn’t sit well with some fans of the event, coming amid an era of widespread climate doom (even though the brand would be highlighting its new Spring EV at the UTMB race expo.) The Green Runners, an environmental running community co-founded by British trail running stars Damian Hall and Jasmin Paris, called it an act of “sportswashing” and released a petition calling on UTMB to denounce the partnership. (Hall even traveled all the way to Chamonix to deliver the petition in person.)

These grumblings of discontent and others that followed exploded into a social media firestorm shortly after UTMB. In October, it became public that UTMB had moved to launch a race in British Columbia, Canada, just as a similar event in the same location was struggling with permitting. A he-said, she-said back-and–forth left onlookers with whiplash. Then on December 1, UTMB livestream commentator Corrine Malcolm announced on Instagram that she had been fired and in late January, a leaked email from elite runners Kilian Jornet and Zach Miller to fellow athletes called for a boycott of the race series. All of it, jet fuel for social media algorithms.

“We’re at a turning point in trail running, but we can keep the core values if the community stands up,” the Pro Trail Runners Association secretary, Albert Jorquera, told me at the time.

In the midst of these dramas, I interviewed race founders Catherine and Michel Poletti over lunch at a Chamonix cafe. For nearly a decade now, I have met with the couple for candid conversations that helped frame online articles and magazine stories, and most recently for the book, The Race that Changed Running: The Inside Story of UTMB.

I plunged headlong into two articles with hopes of explaining it all. There was so much heat swirling around the UTMB stories, and so little light.

“The very thing that made ultrarunning so bonding was being torn apart by the community itself through social media,” said Topher Gaylord. A former elite runner who tied for second in the inaugural UTMB in 2003, Gaylord engineered UTMB’s first title sponsorship with The North Face and has been a close supporter of the Polletis for 20 years. “Some players are using social media to divide the community. That’s super disappointing.”

To me, it felt like the aggressive online activists were winning the day. Trail running suddenly seemed polarized, infected with the intertwined social media viruses of false indignation and close-mindedness. Twice, I deep-sixed my article drafts. Friends and editors convinced me they wouldn’t be read dispassionately. Who wants to be handed a fire extinguisher, when your goal is to torch the house?

Well, what a difference eight months can make. We now have some perspective and, with it, some answers.

Since its earliest days, UTMB’s volunteer founding committee believed in the values of the sport. The very first brochure produced for the race—a mere sheet of paper—featured a paragraph on values. In later years that statement became much more comprehensive, expanding to cover a wide range of topics and the race’s mission to support and protect them.

But maintaining those values in an organization that has gone from a singular race with a literal garden-shed office to a 43 global event series with a staff of more than 70 full-time employees is tricky at best. In an interview once, Michel Poletti paused, asking if I had seen a photo of a mutual friend that was making the rounds. He was climbing one of Chamonix’s famed needle-sharp aiguilles, one foot on each side of a razor sharp ridge—a perilous balancing act, big air on each side. It was his metaphor for trying to move ever up, while balancing business growth and heartfelt values.

Over the course of dozens of hours of interviews with the Polettis, I came to learn one thing: UTMB always moves forward up the ridge. In the process, UTMB corrects its course. It starts with a careful analysis after each edition, evaluating pain points in areas such as logistics, security, media, traffic, and others, discussing how they can be addressed. Historically, those course corrections haven’t been at the pace others might want—especially since the social unrest that developed during the Covid pandemic—but the organization has a reliable pattern of steadily addressing concerns.

And so, not too many weeks after that lunch meeting, UTMB set to work. First came a heartfelt effort they kept under the radar—traveling around the U.S. to listen and learn. They spent two weeks in the U.S. in February, visiting with American athletes, race directors, journalists, consultants, and their Ironman partners. “We need to learn from our mistakes and from this crisis,” Michel said.

Methodically over the ensuing months, UTMB rolled out a series of changes. Some were aimed at directly addressing the controversies, others were overdue for what is, by any metric, the world’s premier ultra-trail running event.

“My hope is that the trail running community understands that we are human,” Catherine had told me over the winter.

Four months ago, at the end of April, the race organization announced that Hoka would become the new title sponsor of UTMB Mont-Blanc and the entire UTMB World Series through 2028. It was a huge move because Hoka, one of the biggest running brands in the world, essentially doubled-down on its support of UTMB and trail running in general. The five-year deal brought benefits other than cash, too. Hoka has a strong history of inclusivity and growing representation among marginalized communities, an area UTMB has announced it intends to focus more on beginning this year. The deal also moved Dacia out of the title sponsor limelight, instead bringing a brand with a strong reputation in trail running to the fore.

Dacia was shifted to the role of a premier partner in Europe, and now plays an integral part in a new eco-focused mobility plan UTMB updated in July. Fifty of their cars can be signed out for use by over 70 staff and 2,500 volunteers, encouraging them to arrive in Chamonix using public transportation instead. The move is estimated to eliminate 200 vehicles driving into the valley. (The organization’s new mobility plan will transport an estimated 15,000 runners and supporters, eliminating the need for approximately 6,000 cars during the UTMB Mont-Blanc week. On average, a bus will run every 15 minutes between Chamonix and Courmayeur, Italy, and Chamonix and Orsières, Switzerland.)

In May, UTMB announced a new anti-doping policy it had developed with input from PTRA. The organization committed to spending at least $110,000 per year, money that will be allocated to test all podium finishers and a randomized selection of the 687 elite athletes in attendance. The new policies will be implemented by the International Testing Association, an independent nonprofit that has also conducted two free informational webinars for the 1,400 UTMB Mont Blanc elite runners.

Not long after the announcement, Catherine Poletti suggested this was just a start. Speaking at TrailCon, a new conference held in Olympic Valley, California, on June 26, she said, “It’s a first big step for us. And we’ll continue to develop this policy.” (The most important anti-doping protocol may still be beyond UTMB, however. “The elephant in the room is that we need a coordinated approach to establish out-of-competition testing,” Tim Tollefson, an elite U.S. runner and director of the Mammoth TrailFest in California, who spearheaded independent testing at his event in 2023. “Individually, we’re just lighting our money on fire.”)

In mid-June, UTMB addressed a longtime issue with top runners—prize money. A chunk of the funding from the ratcheted-up Hoka sponsorship was directed to supporting the bigger prizes for the OCC, CCC and UTMB races in Chamonix—about $300,000 this year, nearly double of 2023—as well as more prize money for the three UTMB World Series Majors. (The sequence was intentional. The organization wanted a new doping policy in place before increasing prize purses, since large cash awards are often thought to lead to a growth in doping.)

It’s a move that was long overdue—the most celebrated marquee event in any sport should reward its top athletes more than any other event—but not possible without Hoka’s increased involvement. The proposal was shared with PTRA in advance of the announcement, and the group provided feedback that was incorporated into the final divvying up of the purse. The total amount spent on prize money across all UTMB races is now more than $370,000.

“We increased the prizes quite dramatically,” said UTMB Group CEO Frédéric Lenart. “It’s very important for us to support athletes in their living.”

Finally, just last week, UTMB announced a new department within the company called “Sport and Sustainability.” The group is headed by longtime UTMB staffer Fabrice Perrin. He was a driving force behind the creation of UTMB’s live coverage back in 2012. Heading up relations with the pro athletes will be longtime elite trail runner Julien Chorier. Nicolas LeGrange, UTMB’s Director of Operations, will be in charge of sustainability and DEI, Diversity, Equity Inclusion.

On the DEI front, UTMB is calling its strategy “leave no one behind,” and they promise new initiatives coming this fall so that, according to Perrin, “every athlete feels a sense of belonging within our community,” he says. “I am committed to ensuring that we perfect symbiosis with the entire community of trail running.”

UTMB has already begun to embrace adaptive athletes, something it was criticized for lacking as recently as last year. This year’s UTMB Mont Blanc races will feature a team of 12 adaptive athletes who will be participating in the MCC, OCC and UTMB races. Under the direction of adaptive athlete and team manager Boris Ghirardi, who lost his left foot and part of his left leg after a motorcycle accident in 2019, the race organization recruited the athletes from around the world to showcase how adaptability and resilience are key elements of the UTMB values.

“I proposed this program to make a concrete action around adaptive athletes and the inclusion policy, and to prove that it was possible,” he said this weekend. “If you really get everyone working on this, you can change the game.”

And with that, UTMB Mont-Blanc 2024 is underway, resuming the golden era status that Byrne raved about last August. Starting this past weekend, banners have been unfurled over Place du Triangle de l’Amitié in the heart of Chamonix, kicking off the carefully choreographed trail running Super Bowl that is UTMB. The excitement begins on August 26 and culminates as the race for UTMB individual crowns reach a tipping point on August 31. (The golden hour of the final finishers on September 1 will be something to behold, too.)

“It’s like wrapping the Tour de France, Burning Man, and the biggest industry trade show into one giant, week-long festival,” Gaylord says. “It’s an amazing week for our sport, one of the biggest showcases we have.”

The aura of Chamonix and the opportunity to run a race there is drawing as much or more interest than ever before. It is perhaps the essence of what will keep the UTMB World Series afloat into the distant future. Runners will continue to chase Running Stones at qualifying events around the world, knowing the carrot of running one of the races around the Mont Blanc massif is second to none.

Trail running is booming on a global scale, and it’s not just UTMB shouldering the burden or reaping the benefits. The Golden Trail World Series, Spartan Trail Running, Xterra Trail Running—and even the World Trail Majors, Western States 100, and dozens of other more prominent trail races—are all trying to get a bigger piece of the pie, either by way of money or relevance.

UTMB Mont Blanc, as trail running’s most important race, is at the very beating heart of it all. And trail running is a soul sport, so when change and growth happen, it can feel threatening to all of us whose lives have been changed for the better by time spent with dirt underfoot and blue sky above. UTMB is big enough now that it’s urgently important that it make changes judiciously and preemptively.

As the world’s most significant trail race, the consequences of UTMB’s choices will ripple throughout the ecosystem. UTMB understands this. “Do we owe something to trail running? Yes, of course we do,” Michel Poletti once told me. That’s truer than ever now.

At TrailCon in June, Catherine Poletti summed up UTMB’s challenge. “Trail running is changing around the world. We’ve seen that evolution over 20 years. We need to adapt, to find a good balance, to accept different models and ways of organizing.”

Back in August 2021, I wrote an article here called, “UTMB, Don’t Break Our Hearts.” It came the summer after the organization announced its investment from the Ironman Group. Change– big change– was everywhere. Could the race around Mont Blanc maintain its soul and passion amid talk of multinational sports marketing, we all wondered? Michel Poletti closed the interview by saying, “Nous prenons un rendez-vous dans trois ans.” Simply translated: “We’ll schedule an interview in three years.”

Three years is now, and both UTMB and trail running’s landscape have changed dramatically, if not literally then certainly figuratively. We’ve seen UTMB adjust its rudder this past year, responding to concerns. Perhaps not at the pace any individual or specific group would like, and not to the extent some would wish. But it’s happening, and for that we should all breathe a cautious sigh of relief. Because if you love trail running, you have to care about what happens at the world’s biggest trail race.

As I write this in Chamonix very early on the morning of August 26, overcast skies are parting and blue skies are in the offing. The forecast for the week ahead is for bright sun with a few clouds. It’s a workable enough metaphor for trail running’s future. But one thing has to happen for it to come true. The race that changed running needs to continue to listen to its stakeholders around the world, and engage with them as it grows and develops in the days ahead. If that happens, Byrne’s vision of the golden age of our sport just might linger on. I can hope.

by Outside Online

Login to leave a comment

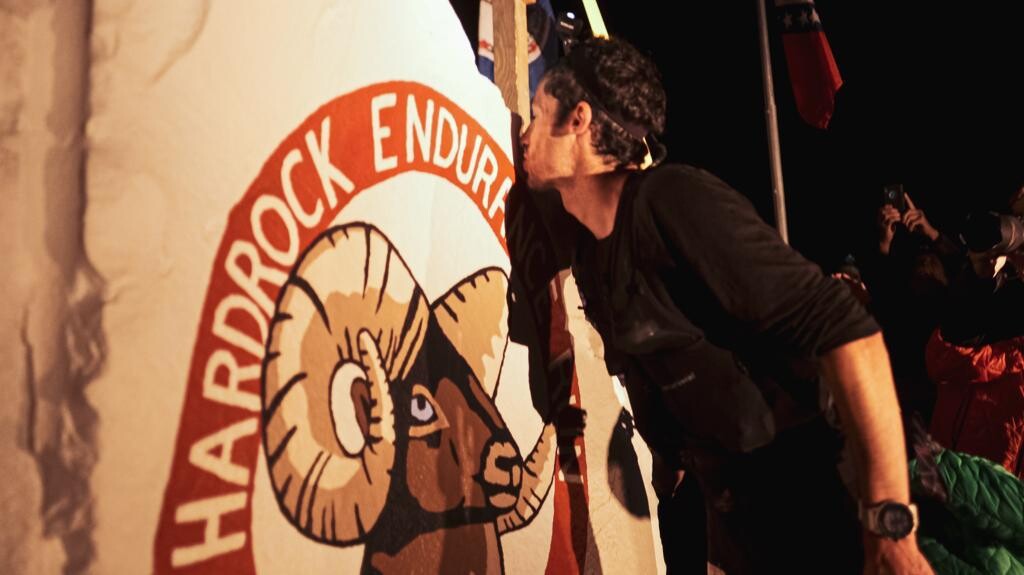

Ludovic Pommeret Wins Hardrock 100 in Course-Record Time Courtney Dauwalter is on course-record pace, trying to win the race for a third consecutive year

This is an ongoing story that will continue to be updated as more runners reach the finish line in Silverton, Colorado.]

Maybe you forgot that Ludovic Pommeret was the 2016 Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc champion. Or that he was the fifth-place finisher in Chamonix, France, just last year. Or maybe you thought the 49-year-old Frenchman was past his prime. Either way, he reminded us all he’s at the top of not only his game, but the game at the 2024 Hardrock 100.

The Hoka-sponsored runner from Prevessin, France, took the lead less than a third of the way into the rugged 100.5-mile clockwise-edition of the course after separating from countryman François D’Haene, the 2021 Hardrock champion and 2022 runner-up, and never looked back. Pommeret progressively chipped away at the course record splits—a course record, mind you, set by none other than Kilian Jornet in 2022—to win this year’s event in 21:33:12, the fastest time in the race’s 33-year history. Jornet set the previous overall course record of 21:36:24, also in this clockwise direction in 2022.

(Pommeret kissed the rock in to complete the course in 21:33:07 at 4:33 A.M. local time, but race officials credited him with the slightly slower official time.)

“It was my dream (to win it),” Pommert told a small collection of fans and media after winning the race at 3:33 A.M. local time. “I was just asking ‘when will there be a nightmare?’ But finally, there was no nightmare. Thanks to my crew. They were amazing. And thanks to all of you. This race is, uh, no word, just so cool and wild and tough.”

On Friday, July 12, 146 lucky runners embarked on the 2024 Hardrock 100. Run in the clockwise direction this year, it was the “easy” way for the course with a staggering 33,000 feet of climbing and an average elevation over 11,000 feet thanks to the steep climbs and more tempered, runnable descents.

Combined with relatively cooperative weather (hot during the day on Friday, but no storms) and a star-studded front of the pack headlined by Courtney Dauwalter and D’Haene, the tight-knit Hardrock 100 community was on course record watch.

And the event delivered—along with a whole lot more.

On the men’s side, the front of the race took a blow before the gun even went off when Zach Miller, last year’s Ultra-Trail du Mont Blanc runner-up, was denied entry after undergoing an emergency appendectomy the weekend before.

Despite the heartbreak of being forced to wait another year to participate in this hallowed event, Miller was very much a presence in the race, most notably for slinging fastnachts (Amish donuts) from his van in Ouray for race supporters and fans.

Such is the spirit of this event, deemed equally as much a run as a race.

The men’s race was further upended when D’Haene, in tears surrounded by his wife, three children, and friends, dropped from the race at the remote Animas Forks aid station (mile 58). An illness from two weeks before proved insurmountable for the challenge ahead. That blew the door wide open for the hard-charging leaders ahead.

Pommeret had built a 45-minute lead over Jason Schlarb, an American runner who lives locally in Durango, and Swiss runner Diego Pazosby, the time he had left the 43.9-mile Ouray aid station amid 85-degree temperatures. His split climbing up and over 12,800-foot Engineer Pass (mile 51.8) extended his lead to more than an hour over Schlarb and nearly 90-minutes at the Animas Forks aid station.

“I thought it was great. To run off the front like he did, and then just hold that all day and get the overall course record is pretty awesome,” Miller said. “When Killian did it, two years ago, it was a, it was a track race between him, Dakota, and François, after they got some separation from Dakota, it was Kilian and and François, all the way to Cunningham Gulch (the mile 91 aid station) and then Kilian just torched it on the way in. So yeah, it was super, super impressive for Ludo to do that. That’s a very impressive effort.”

The sleepy historic mining town of Silverton, Colorado was unusually hectic at 6 A.M. on Friday. In the blue hour before the sun poked over the San Juan Mountains looming above, 146 runners toed the start line of the Hardrock 100, marked by flags from the countries represented by competitors on either side of the dirt road.

With the sound of the gun, runners jogged off the start line—their caution a tacit sign of respect for the monumental challenge of what was to come. As the runners passed through town to the singletrack wending its way up to Miner’s Shrine, group of men headlined by D’Haene, Ludovic Pommeret, Diego Pazos, and Jason Schlarb quickly took command of the front, the bright yellow t-shirt of Courtney Dauwalter was easy to spot just behind, along with Katharina Hartmuth and Camille Bruyas.

If they weren’t awake already, runners certainly were after crossing the ice-cold Mineral Creek two miles into their journey before starting the grunt up to Putnam Basin. At the top of a sunny, grassy Putnam Ridge (mile 7) 1:34 into the race, the lead pack of men remained, while Dauwalter had made a statement solo just three minutes back from the men and four minutes up on Hartmuth.

Dauwalter was smiling and chatty when she reached the KT aid station at mile 11.5, in 2:24 elapsed. By Chapman (mile 18.4), four hours in and 10 minutes under her own course record pace, she was pouring water on her head under the blazing sun. Things were heating up—in more ways than one.

When Pommeret galloped into Telluride (mile 27.7) after 5:37 of elapsed time in the lead, he was right on Jornet’s course record pace. One minute, some fluids and restocking later, and he was gone.

But wait, it was still a close race! D’Haene charged into Telluride just two minutes later and hardly stopped before continuing on through downtown before busting out the poles and starting the steep, steep 5,000-foot climb up Virginius Pass to the iconic Kroger’s Canteen aid station nestled into a notch of rock at the top at 13,000 feet.

Not to be outdone, the women’s race proved equally thrilling coming into Telluride. Bruyas bridged the gap up to Dauwalter, and the two ran into town together in 6:25 elapsed. Both took three minutes in the aid station, although that must have been enough social time for Dauwalter, as she pulled ahead marching up the climb, poles out and head down. A bouncy Bruyas alternated between hiking and jogging just behind.

But time again again, Dauwalter’s long, powerful stride simply proved unparalleled. By Kroger’s (mile 32.7) Dauwalter had reestablished her lead by five minutes over Bruyas and 17 ahead of Hartmuth in third. She’d built that gap to 10 minutes in Ouray at mile 43.9, but she left that aid station in less than two minutes with a stern, serious look on her face. But as she crested Engineer Pass at the golden hour, wildflowers blanketing the vibrant green hillsides basking in the setting sun, she enjoyed a 30-minute lead in the women’s race and was knocking at the door of the men’s podium.

While Dauwalter forged ahead with her unforgiving campaign for a third straight win, the men’s race started to rumble. Like Dauwalter, Pommeret continued to blaze the lead looking strong as he trotted down Engineer to the Animas Forks aid station at mile 57.9 in 11:39 elapsed. He hardly stopped before continuing on to Handies Peak, which at 14,058 feet marks the high point of the race. He had blown the race wide open.

An hour and 15 minutes later, Schlarb, looking a bit more beleaguered, ran into Animas Forks with his pacer, where he sat down and changed his shirt while receiving a pep talk from his partner and son. But he made quick work of the time off feet nonetheless, and three minutes later he was back at it, seven minutes before Pazos appeared.

While D’Haene arrived just 10 minutes later, he did so in tears, holding the hand of his youngest son. After a considerable amount of time sitting in the aid station, surrounded by his family and crew, he called it quits. The lingering effects of an illness from just 10 days before proved too much to overcome as the hardest miles of the race loomed ahead.

While D’Haene pondered his fate, Dauwalter blitzed into Animas Forks in 13:26 with that same look of determination, 16 minutes ahead of course-record pace. She briefly stopped to prepare for the impending night, picking up her good friend and pacer Mike Ambrose to leave the aid station in fourth overall. Bruyas maintained her second place position 30 minutes back, with Hartmuth in third about 20 minutes behind her.

Pommeret continued charging ahead solo, increasing over Schlarb and Pazzos by more than two hours late in the race. When Pommeret passed through the 80.8-mile Pole Creek aid station at 10:44 P.M., it shocked the small group of race officials, media and fans watching the online tracker from the race headquarters in Silverton. Based on that split, it was originally calculated that Pommert could arrive as early as 2:34 A.M.—which would have been a finishing time of 20:34—but he didn’t run the final 20 miles quite as fast as Jornet did in 2022.

Behind him Pazos caught Schlarb to take over second place before Pole Creek and increased the gap to four minutes by the Cunningham aid station (mile 91.2).

Pommeret, who develops training software for air traffic controls in Geneva, Switzerland, didn’t break into ultra-trail running until 2009 when he was 34 years old. He was third in UTMB that year—behind a 20-year-old Jornet, who won for the second straight year—the first of seven top-five finishes in the marquee race in Chamonix. (He was third in 2017 and 2019 and fourth in 2021 and 2023.) He also won the 90-mile TDS race during UTMB week in 2022, and the 170-kilometer Diagonale des Fous race (Grand Raid La Reunion) on Réunion Island in the Indian Ocean in 2021 and placed sixth in his first attempt at the Western States 100 in California in 2022.

Last year, Pommeret placed 13th overall in the Western States 100 and nine weeks later finished fifth at UTMB behind Jim Walmsley, Miller, Germain Grangier, and Mathieu Blanchard.

“We know Ludo is a beast, but to be a beast for so long, for so long is so impressive,” Miller said. “He’s 49, which by all means is a capable age in this endurance world. But I think anytime someone 49 does something like that, it’s gonna turn some heads because that would’ve been a really good performance for anyone. To have the track record he’s had—winning Diagonale des Fous, UTMB and Hardrock, that’s pretty impressive.”

Courtney’s Final

By the time Dauwalter was pushing her way up Handies Peak, she had a smile on her face and engaged in playful conversation with media and spectators on the course. She had good reason to smile: she was feeling good and she had increased her 10-minute lead at Ouray to more than 60 minutes. Dauwalter went through the Burrows aid station (mile 67.9) in less than a minute, while Bruyas came in an hour later and spent four minutes refueling before heading out again.

Three hours after Pommeret had passed through the Pole Creek aid station (mile 80.8), Dauwalter arrived at 1:54 A.M., still in fourth place overall about 50 minutes behind Pazos and Schlarb. She took a little more time there, but was back on her feet in four minutes and running strong again and still on record pace. Bruyas walked in to Pole Creek at 3:08 A.M. in sixth overall, but the gap behind Dauwalter continued to widen.

Dauwalter was in and out of the Maggie aid station (mile 85.1) in two minutes and blazed through the Cunningham aid station (mile 91.2) even faster. The race seemed to be in hand at that point with Bruyas more than 90 minutes behind (in fact, someone updated Wikipedia and declared her the winner not long after Pommeret finished), it was just a matter of how fast she could finish.

Login to leave a comment

The queen of ultradistance Courtney Dauwalter is set to defend her Hardrock 100 crown

Courtney Dauwalter , the queen of ultra-distance running, will once again put on trail running shoes this Friday to compete in the Hardrock 100 , the prestigious 165-kilometer mountain race with 10,000 meters of positive elevation gain that takes place in the San Juan Mountains in Colorado, United States.

The American runner will try to defend the title she won in 2023, when she won the race with a record time of 26h14:08 , although this year, unlike last year, the race will be run clockwise.

"It's a great race, very tough and difficult. I'm coming back because all my participations here have had very tough moments, and I hope to be able to soften those moments a bit and finish the race without so many difficulties," said Dauwalter in an interview with iRunFar.

The reigning Transgrancanaria and Mt. Fuji 100 champion will face her main opponents in Germany's Katharina Hartmuth and France's Camille Bruyas , second in the UTMB Mont-Blanc in 2023 and 2021, respectively.

On the men's side, the main figure will be the French runner François D'Haene , who wants to repeat his victory from 2021 and, why not, beat the circuit record belonging to the Spaniard Kilian Jornet (21h36:24).

American Zach Miller is on the roster, although he is likely to miss the event due to recent appendix surgery.

The Hardrock 100 begins and ends in the town of Silverton and passes through some of the most spectacular mountain scenery in the United States, home to elk, bears and cougars. The highest point is Handies Peak, at 4,200 meters.

The race will start on Friday 12th July at 6am (2pm in Spain) and can be followed live on YouTube .

by Matias Camenforte

Login to leave a comment

Hardrock 100

100-mile run with 33,050 feet of climb and 33,050 feet of descent for a total elevation change of 66,100 feet with an average elevation of 11,186 feet - low point 7,680 feet (Ouray) and high point 14,048 feet (Handies Peak). The run starts and ends in Silverton, Colorado and travels through the towns of Telluride, Ouray, and the ghost town...

more...Walmsley and Schide favorites as Western States line-ups are finalized

Americans Jim Walmsley and Katie Schide, both UTMB winners, will head the finalized fields for the 51st edition of Western States 100 Endurance Run at the end of this month.

Western States is the oldest and arguably the most iconic 100-mile trail run in the world and the stars are again out in force Auburn on June 29-30.

Can Walmsley make it four?

Last year Walmsley memorably ended his quest to finally add a UTMB title in Chamonix to his CV and he’s the current course record holder at Western States, which he’s already won three times.

His time of 14:09:28 from 2019 hasn’t been bettered since and he’s the highest-ranked runner in terms of the UTMB index at 934 (Kilian Jornet is top on 941).

But he’ll face a raft of strong rivals including the 2023 runner-up Tyler Green (USA, UTMB Index 880) and several other top finishers from 2023, including fourth-placed Jiasheng Shen (CHN, UTMB Index 906).

Dakota Jones (USA, UTMB Index 902), Ji Duo (CHN, UTMB Index 889) and Hayden Hawks (USA, UTMB Index 910) booked their spots alongside Walmsley via Golden Tickets from top-three performances at other big events.

Schide the one to beat

And on the women’s side the 2022 UTMB winner Katie Schide (UTMB Index 825) will be looking to go one better than last year’s second place at Western States.

Only superstar Courtney Dauwalter on 847 is ahead of Schide on the UTMB Index but the reigning Western States champion (who smashed the course record time when beating Schide) won’t be back to defend her title.

That means that Schide, who underlined her form with victory at the Canyons Endurance Runs by UTMB at the end of April, starts as the clear favourite.

But she too will face tough opposition from the likes of Eszter Csillag (HUN, UTMB Index 768), who finished third 12 months ago, and three-time finisher Emily Hawgood (ZWE, UTMB Index 757).

Other big names lining up include former professional IRONMAN athlete Heather Jackson (USA, UTMB Index 764), Eleanor Davis (GBR, UTMB Index 753) and Emily Schmitz (USA, UTMB Index 736).