Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Search Results for Ultra

Today's Running News

Runners Are Racing More than Ever

Strava’s year-end report shows that more runners are turning to competition and how different generations compete differently

This month, Strava released its annual Year in Sport, with fascinating insights about where running might be headed. Running was the most-uploaded sport in 2023. (Hear that? That’s the sound of job security!) Most runners log their miles solo, 9 percent are in groups of three or more people, and an additional 9 percent are logged running in a pair.

Trail running, specifically, continues its trend upwards, with the share of athletes running off-road up 6 percent year over year. Almost half (47 percent!) of runners took at least one trail run. Friends, welcome to the club. We have jackets! (Haha, no we don’t.)

Many runners use competition as motivation and inspiration. Plus, athletes who race are 5.3 times more likely to set a distance PR. While men are currently more likely to compete than women, the rate at which men and women are participating is increasing at the same speed.

When life after the COVID lockdowns stabilized for many folks, the Strava Year in Sport review shows that they laced up their running shoes to compete. Twenty-one percent of runners on Strava ran at least one race in 2023, a 24 percent increase over 2022.

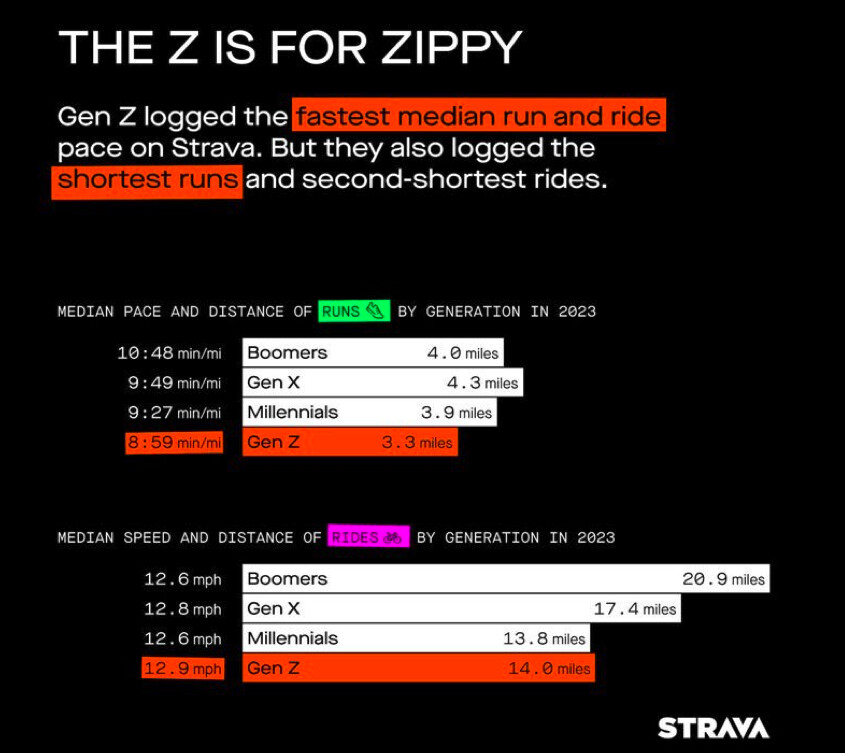

Racing was equally split across genders, with 21 percent of men and women competing at least once. Runners from Gen X (born between 1965 and 1980) were the most likely to race, with 26 percent logging at least one competition on Strava. Twenty-two percent of millennials (born between 1981 and 1996) raced, and 24 percent of boomers (born before 1965) pinned on a bib in 2023.

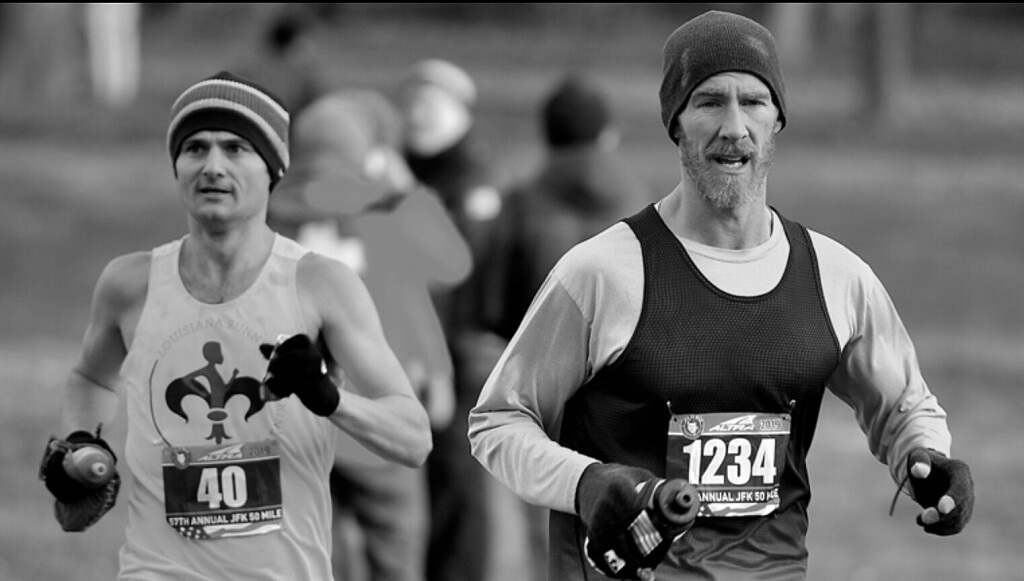

Ultramarathons, while still less popular than shorter distances, are steadily becoming more popular, too, according to statistics. While just 2 percent of runners on Strava completed an ultra in 2023, that’s still up 11 percent from 2022.

Out of all ultrarunners on the app, two-thirds completed at least one 50K, meaning plenty of runners double-dipped on super long-distance runs in 2023. Women were 43 percent less likely to have run an ultra of any distance (so, yeah, we might have a problem). Participation in ultras may be growing at the same rate among men and women, but there is still plenty of work to be done—for instance, addressing childcare disparities that leave women with three to four fewer hours per week to train—in order to reach equity. The longer the distance, the greater the gender gap tends to be, with half marathons having the smallest disparity—7 percent of women completing a half and 8 percent of men.

Longer races are less popular this year, sure, but participation is growing by about 10 to 15 percent. Less than 1 percent of runners on Strava completed an ultra over 50K, though this distance remains the most popular to run. Participation in 50 miles is roughly half that of 50Ks, and 100K participation is roughly half that. So, if you ran a 100K this year, pat yourself on the back, as you’re part of the 1 percent (.0025 percent, to be exact).

Marathons remain a popular distance for runners. Five percent of runners on Strava ran a 26.2-mile race in 2023, up 20 percent from last year. Again, women were 32 percent less likely to have run a marathon than men (4 percent of women on Strava ran a marathon versus. 5 percent of men), but both groups saw participation jump 20 percent compared to last year.

Gen Zers are not running as much as previous generations did at their age. Running, while less cost-prohibitive than, say, surfing, skiing, or mountain biking, still requires some financial investment. A 2020 survey by the Running Shoes Guru pinned the “average” run budget to between $937 and $1,132 annually. I guess those gels really do add up!

And when you consider that 60 percent of young adults don’t feel their basic needs are met, a decline in participation makes sense. According to Running USA, an independent group that produces industry surveys, the number of runners in the 35-44 and 45-54 age groups has dropped significantly since 2015, while participation in the 25-34 age group only increased slightly. According to the report, Gen Z runners prefer to run for experiential benefits like socializing, fun, and mental health.

Interestingly, data about Gen Z runners on the Strava Year in Sport says the opposite, reporting that this generation is 31 percent less likely to exercise primarily for their health compared to millennial and Gen X counterparts. The difference could be that runners committed enough to sign up for an activity tracking app are already a self-select group. Zoomers on Strava report that their primary motivation for exercise is athletic performance. This is echoed by the speed of their training runs, which average out to be a pace of 8:59 a mile. Zoinks!

Interestingly, data about Gen Z runners on the Strava Year in Sport says the opposite, reporting that this generation is 31 percent less likely to exercise primarily for their health compared to millennial and Gen X counterparts. The difference could be that runners committed enough to sign up for an activity tracking app are already a self-select group. Zoomers on Strava report that their primary motivation for exercise is athletic performance. This is echoed by the speed of their training runs, which average out to be a pace of 8:59 a mile. Zoinks!

Gen Z runners are also more run-dominant than other generations. Seventy percent of the generation’s Strava users uploaded runs onto the app versus 52 percent of Gen X, a 35 percent higher likelihood (this might as well be the likelihood to Google “What is a Zendaya?”) Gen Z runners saw the greatest percentage of growth in race participation this year, with a 60 percent jump in attendance at the marathon distance and a 68 percent increase at 13.1. (My mind would fully melt if I lined up against someone born in 2004, but also, welcome! Please be gentle.) According to Running USA, Gen Z runners gravitate towards races with a compelling theme or cause that resonates with their values.

Trends are different across training habits, too. Gen Z runners are twice as likely as boomers to have weekday activity after 4 P.M. and are 31 percent less likely to exercise before 10 A.M.. Fascinatingly, 39 percent of Gen Z Strava athletes started a new job, and a third of the cohort reported relocating in 2023, which could speak to flexibility or economic instability for younger runners.

Over the year, Gen Z runners logged 17 percent less mileage than Gen X athletes, explained primarily with a shorter average run length. Plus, Gen Z athletes have slightly fewer running weeks in a year. (Maybe if they weren’t so busy eating all that avocado toast, they could run more!) JK, as the kids on TikTok say. In truth, Gen Z runners might train less because they are shooting for shorter distances, or the other way around—it’s impossible to disentangle causation here.

It’s not only a fun pastime to browse the year-in-review data, poking fun at the generations before or after us like they’re siblings (“No, I run more!” “Well, I run faster!”), but it’s also a way to see where the industry is lacking.

The Strava Year in Sport data shows that the running industry will have to work to bring in more Gen Z athletes. This might mean that race directors and event organizers will have to continue tailoring their offerings to speak to a younger, more experience-driven demographic. Numbers also prove that, while the female section of the running pie has grown overall, more changes need to be made to reach gender equity. The statistics tell us a lot, but one of the biggest, if not the biggest, takeaways is that people are running more now than ever. And that? Well, that’s pretty rad.

(03/02/2024) ⚡AMPTry these tough race-prep workouts for unstoppable stamina on road and trail

While most of your training should be easy mileage, it’s important to have some speedwork and harder efforts in there if you want to perform your best on race day—and occasionally, an extremely challenging workout. Renowned coach and ultrarunner David Roche explains that, inserted once in a while, an epically tough session will pay off in a variety of ways. “Your brain and body can essentially have their light-bulb moments: ‘Oh! I see! I will not die the next time I push this hard? Good to know, you can carry on.’ ”

While these workouts are designed with trail runners in mind, they can be very effective for runners training for road and track races as well. “These workouts are designed to suck,” Roche jokes. “That way, future workouts and races will suck less.” Make sure that you are well-trained with a strong base before tackling these in order to prevent burnout and injuries, and do them after a few recovery days (and followed by a few recovery days as well).

Hill and tempo leg-crushing combo

Warm up with 15-30 minutes of easy running. If you’re prepping for shorter races, feel free to tweak the warmup, but make sure your muscles are warm and your legs are ready to work before kicking it into high gear.

Run 5 x 3-minute on hills at a hard effort, and run down the hill for recovery between reps.

After the final hill interval, run 15-30 minutes with a moderate effort to simulate tired, race-day legs.

Roche suggests aiming for an average grade of six to eight per cent on the hills—a moderate incline that will allow you to maintain form while pushing hard. “At the top, you can put your hands on your knees for a second before running down normally,” Roche says, and suggests giving an extra-hard push to the final two repeats. When you wrap up the final interval, run down the hill and ease into a relaxed tempo, pushing to a moderate effort.

Cool down with 10 minutes of easy running.

Roche suggests trying this one 10-17 days before your goal event.

Three-minute hill hell

Warm up with 15-30 minutes of easy running (adjust if you’re running a shorter race).

Run 8-10 x 3 minutes at roughly a 10K effort uphill, with one to two minutes of easy recovery between hills and three minutes of very easy recovery after your final rep.

Next, run 6 x 30 seconds of hard effort (Roche says aim to “feel and accept discomfort” in these) on semi-steep hills with 90 seconds of easy recovery between hills.

Cool down with 10 minutes of very easy running.

Roche says this workout can be used in almost any training cycle, even for road races, and suggests fitting it in once you have a strong mileage base to avoid injury.

Remember, Roche recommends several rest and recovery days before and after each super-tough workout that you do to prep your legs for race day.

(02/29/2024) ⚡AMPby Keeley Milne

Chase the Sun - Running in Sunglasses

Running is more than just a workout; it's an exhilarating adventure that lets you embrace the great outdoors, break a sweat, and feel the wind in your hair.

It’s not just about you and the pavement anymore - as any seasoned runner knows, the right accessories can make all the difference. This might be a new pair of running trainers, are some additional kit, anything from some bone-conducting headphones to a belt for your phone, keys, and a drink. You might have a Garmin running watch to track your times and fingerless gloves for those chilly mornings out on the road.

Among popular accessories, sunglasses emerge not just as a style statement but as a game-changer for your run. Picture this: you, pounding the pavement with a steady rhythm, the sun casting a warm glow on your path. Without sunglasses, you get momentarily blinded and stumble….

Now picture this – the same scene, but on your face is a sleek pair of shades adding that extra cool factor to your stride. Glare? No such thing as you power forward on your way to a personal best. Let's delve into why these are not just fashion whims but essential gear for every runner.

Why You Need Sunglasses for Running

Running under the open sky is invigorating, but it comes with its challenges. The sun can be a relentless adversary to your eyes, causing a multitude of problems. That's where sunglasses come in. Beyond being a trendy accessory, they are your shield against the sun's potent UV rays. Prolonged exposure to these rays can lead to eye strain, fatigue, and even long-term damage. Imagine squinting through your entire run, your eyes battling the glare –not exactly the calming jog you envisioned.

However, running involves constant movement, and that can mean sunglasses are uncomfortable. You have to balance that with the effects of the environment - anyone who's ever tried running against the breeze knows the struggle of keeping their eyes wide open. Sunglasses act as a barrier, keeping wind, dust, and other airborne nuisances at bay. Ever felt a speck of dust or a stray insect in your eye mid-stride? Sunglasses make sure your focus stays on the path ahead, not on clearing debris from your eyes.

Also, the importance of glare reduction cannot be understated. Whether you're running on a beach boardwalk, a city street, or a forest trail, reflective surfaces are everywhere. The sun bounces off cars, water, or even fellow runners! A good pair of running sunglasses with polarized lenses protects you from glare, ensuring you maintain optimal visibility and reducing the risk of accidents.

There are considerations – you can’t just grab any old pair of sunnies. If they’re not the right fit, you’ll be constantly adjusting ill-fitting sunglasses mid-run. With that in mind, here are the main considerations when identifying a pair of running sunglasses to add to your kit.

Recommended Sunglasses for Running

First and foremost, UV protection is non-negotiable, so you should look for sunglasses that offer 100% UVA and UVB protection. However, you need to pair those with something comfortable. Lightweight frames and adjustable features ensure a snug fit without causing discomfort. Remember, the last thing you want is for your sunglasses to become a distraction rather than an asset.

Lightweight doesn’t seem to fit with durability, but you’ll need a strong pair, just in case they fall off. Opt for frames made from robust materials that can withstand the occasional bump, sweat, or accidental drop. Running is an adventure, and your sunglasses should be up for the ride.

Also, the lenses are important. We’ve mentioned polarized already, and that’s important in reducing glare. However, you should also pay serious consideration to the lens color. While personal preference plays a role, certain tints can enhance visibility in specific conditions. Gray lenses maintain color accuracy in bright sunlight, brown lenses enhance contrast in varying light conditions, and yellow lenses are great for low-light settings.

There are a couple of brands which come highly recommended. One manufacturer with a reputation for making running sunglasses is Oakley. Their BXTR model boasts plant-based BiO-Matter®* frame material that provides lightweight comfort and durability whilst running, but they’re also durable – they’re designed and undergo high-velocity tests to ensure they’re fit for high-octane situations.

Bolle also has a reputation within the sports eyewear sector, and they’re another option. They have the C-Shifter among their popular running models, with polycarbonate shatterproof and impact-resistant lenses. There’s also a half-rim shield lens that provides excellent airflow for particularly demanding runs.

Finally, CEBE offers a budget-friendly range for those runners who might hang up their trainers after they’ve got fit. They have the Outline model, which comes with an ultra-lightweight frame and shatterproof lenses. They tend to be more multi-use rather than for running, but at the lower end of the scale, they’re certainly a budget option.

Conclusion

Sunglasses - they're not just a finishing touch to your running ensemble; they're your armor against the elements, your shield against UV rays, and your style statement on the go. Running is about freedom, and with the right sunglasses, you're chasing miles, but you don’t have to run away from the sun.

(02/18/2024) ⚡AMP

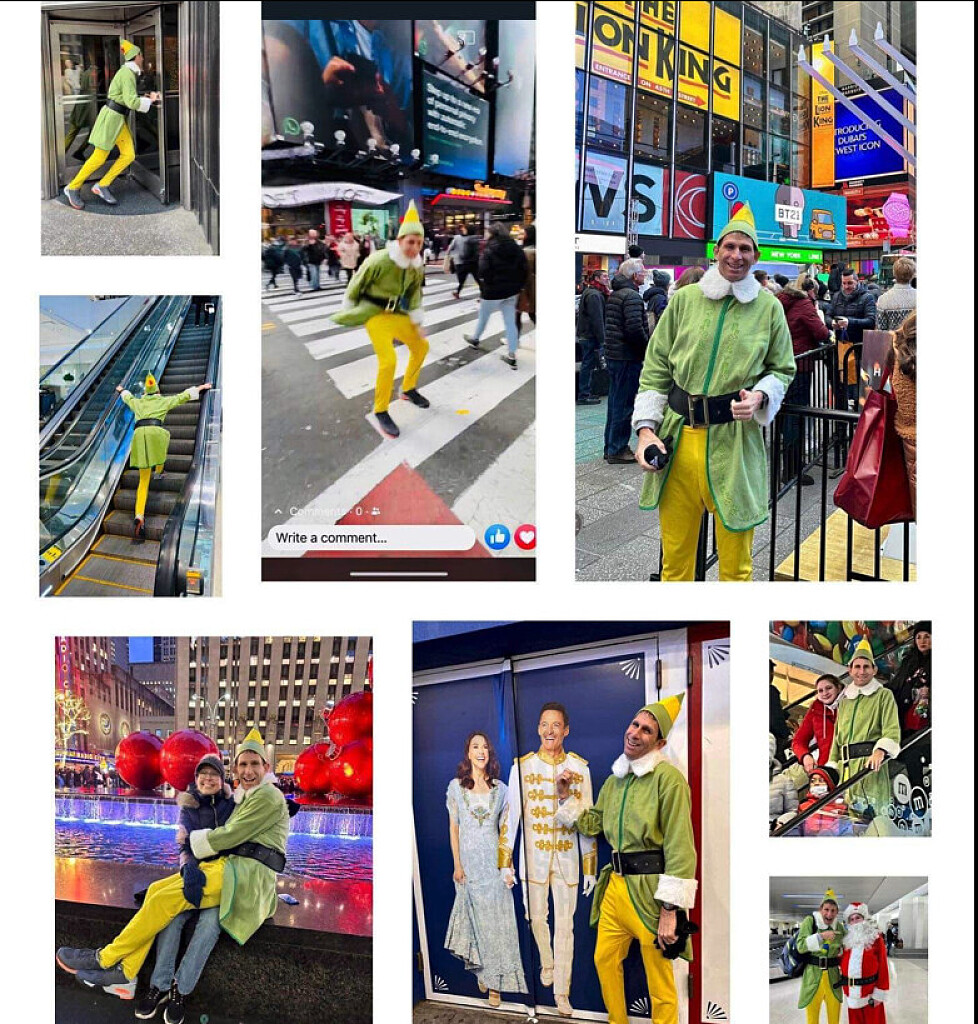

Buddy the Elf Shatters Guinness Record with Help from Pro Ultramarathoner

Jason Homorody was gunning for the fastest half marathon as a movie character when he ran into Harvey Lewis.A modern-day staple of road running is unexpectedly coming across people running in costume either for a charity or in the hopes of setting a Guinness World Record, but sometimes, these costumed individuals discover the unexpected themselves.

On Sunday, Jason Homorody, 50, was beginning his quest to break the record for the fastest half marathon time while dressed as a movie character—Buddy the Elf from Elf in his case—at the Warm Up Columbus Half Marathon when he received some surprising support from a fellow runner. While attempting to break the previous 1:30:42 record, Homorody, who—obviously—loves Elf and regularly wears the costume around to “cheer people up,” was joined by Harvey Lewis, the current backyard ultramarathon record holder and well-decorated ultrarunner, who has won the likes of the Badwater 135 and USATF 24-Hour National Championships.

“[He] came up on my shoulder and asked me what pace I was going for,” Homorody told Runner’s World. “Once I answered some questions, he asked if he could run with me. Honestly, at first, I had no idea who he was. But he ran with me the entire race.”Homorody also said Lewis helped him with hydration during the race. “When we would pass the water stop on the course, he was asking if he could get me anything. He kept encouraging me to get water because I think he was concerned about me overheating in my costume,” Homorody said, adding that the two talked about Lewis’ upcoming races during the event.“I was picking his brain about ultramarathoning,” Homorody said. “I knew he recently had a crazy backyard ultra world record, and I was asking if he was almost falling asleep at any point while running, and he said yes.”

So, did the support of an ultramarathoner ultimately push Homorody to his goal? It seems like it, as Buddy the Elf crossed the finish line in 1:25:44, besting the previous record by more than 5 minutes.

“[Lewis] was just a very down-to-earth guy, and he seemed genuinely excited to help pace me to my world record attempt,” Homorody said.

(02/11/2024) ⚡AMPby Runner’s World

Burnout Is Complicated

Kieran Abbotts is a PhD student at the University of Oregon, studying human physiology. He earned his master's degree in Metabolism and Exercise Physiology at Colorado State University. The lab that he works at now studies exercise and environment and stressors on physiology. In other words, he's an expert on how the chemicals in the body work during exercise, and what happens when things get out of whack.

"Essentially, there are two kinds of training. There's functional overreaching, which means you stress the body with hard workouts and long runs. Then you provide adequate time to recover, and you induce adaptations," Abbotts said. This kind of training is ideal-your body is getting stronger. "You want to be functionally overreaching as an elite athlete-so that you're making progress and becoming a better runner, but also giving yourself adequate recovery."

And then there's non-functional overreaching, which can feel the same to many athletes, but it's very different.

"With non-functional overreaching you're essentially doing the same thing-big workouts, stressing the body-but not giving yourself enough time to recover. And so you start doing damage." That damage might take a long time to show itself, Abbots said, but it eventually will.

This might be the most important thing to know about being an athlete at any level. Non-functional overreaching is exactly the same as very healthy training, except without enough rest. And rest is different for everyone, which makes it exceptionally easy to slip from functional overreaching into damaging non-functional overreaching without realizing it. Without adequate rest, the body begins to break down instead of build stronger.

Stress Is Stress

Professional ultrarunner Cat Bradley, 31, living in Hawaii, has experienced fatigue and burnout in various forms, including just after she won Western States in 2017.

Winning a big race is great, but it also means all eyes are on you-the pressure is high to stay on top. "After winning Western States, I took a month off, but I was still running at a high level. And for lack of a better term, I felt like I had a gun to my back," Bradley said. "I wanted Western States so badly, and after I won, so many things happened and I never shook that gun-to-the-back feeling. After a while, it led to burnout. I had to take a mental break."

For many athletes, finding success can be the stress that makes non-functional overreaching feel necessary. How can you take an extended break when you're winning and signing new sponsor contracts?

A second version of burnout for Bradley came when she went through an especially stressful situation outside of running. She was dealing with such extreme daily emotional stress in her personal life that everything else was affected, including running and training. When the body is enduring stress, it doesn't know (or care) what the cause is. We can't put our life into silos. If there's stress in one's life, everything else needs to be adjusted. It doesn't matter if that stress is "just work" or illness, or relationships.

When you're overtraining, or chronically overstressed, your body is creating higher levels of "catecholamines" hormones released by your adrenal glands during times of stress like epinephrine, norepinephrine, or adrenaline. "Having those chronically high levels of overstimulation and not enough recovery, you wind up with a desensitization," Abbotts said. "Overstimulation also causes decreased levels of plasma cortisol. Cortisol is the stress hormone, and it plays a very important role in your physiology."

When you're exercising or stressing the body, cortisol will go up, to help the body deal with the stress. But if you're constantly requiring lots of cortisol, your body will eventually down-regulate. It will adapt and then you'll have low levels of cortisol. This means trouble dealing with physical and mental stress.

In February, Bradley experienced her most recent version of burnout, and it happened mid-race. Bradley was running the Tarawera 100-miler in New Zealand. Besides training for such a big race, she was also working full-time and planning and preparing for her wedding, which was just days after the race. On top of everything, travel to the event was incredibly stressful.

"I was in fourth place, I could see third, and at mile 85, I passed out and hit my head on a rock," Bradley said. "We can talk about the reasons that I fainted, but I really think my brain just shut down-it was too much."

For Bradley, reaching burnout has a lot more to do with outside stressors than the actual running. But now she's aware of that-she continues to work on not reaching the gun-to-the-back feeling. The need to please others. The fear of losing fitness in order to take care of her body. It's an ongoing process, but an important one.

Overdoing Is the American Way

Professional ultrarunner Sally McRae said, based on her observations, Americans are really bad at taking time off. "I've traveled the world and Americans are really bad at resting," she said. "It's part of our work system. You go anywhere in Europe and everyone takes a month-long holiday. You have a kid and you take a year off. We're not conditioned like that in America. It's like you get one week and then after you work a decade, you get two weeks of vacation."

For McRae, avoiding burnout and overtraining has a lot to do with creating a life that's sustainable. She started working when she was 15-years-old, so she realized earlier than most that life couldn't just be working as hard as possible to count down to retirement.

"Perspective is massive when it comes to burnout. My goal every year is to find the wonder and the beauty and the joy in what I do. Because it's my job, but it's also my life," McRae said. "And I really believe we're supposed to rest-it should be a normal part of our life. Whether that's taking a vacation or taking an off-season. I take a two-month offseason and I have for a long time."

One of the most important parts about rest and not overstressing the body is that everyone is different. An overstressed body can lead to hormonal imbalances, which in turn affects everything.

"When you're overtraining, you tend to get mood changes and have trouble sleeping," Abbotts said. "Two of the big things that stand out are you're exhausted but you can't sleep. And the other is irritability-mood swings, and depression." When you get to the point that you've overstressed your body for so long that the chemicals are changing, pretty much everything starts falling apart.

And even though everyone is different, you'd never know that from looking at social media. "I know social media makes it seem like ultrarunners are running 40 miles a day, doing a 100-mile race every other weekend," McRae said. "And that's insane. You've got to be in touch with yourself. It's very different to wake up and feel sore or tired, but if you wake up and feel like you have no joy in the thing you're doing, you need a real break from it."

How Can the Running Community Do Better?

Elite ultrarunner and running coach Sandi Nypaver wants runners to get more in touch with how they're feeling and less concerned about numbers or what anyone else is doing.

"I have to have honest talks with people I'm coaching. I need them to feel like they can tell me how they feel, because sometimes they think they have to stick to the training plan for the week no matter what," she said. "But the plan is never set in stone. It's meant to be adjusted based on how you're feeling. Some weeks we might feel great and not need to change anything, while other weeks we might have to totally crash the plan and do something else."

It's easy to judge ourselves against everyone else, especially when results and reactions are so public and available.

"It's easy to say, 'if that person only took three days off after a big race, and now they're already back to training, that must be what you're supposed to do,'" she said. "But even at the highest level, training is different for everyone. Resting is different for everyone."

"Something that's really, really hard for many runners to understand is that once you're not sore anymore, that you're still not recovered," Nypaver said. "A lot of research says that things are still going on in your body for up to four weeks after, for certain races, depending on the distance."

Sometimes it's difficult to be aware of subtle signs when the soreness is gone. "Convincing people that they need to chill out for a while, even past the soreness, can be really difficult." But after a huge effort, and before the next, people rarely end up saying things like, "I really wish I hadn't rested so thoroughly." Part of it is actually having a recovery plan. Putting rest days on the calendar, focusing on foam rolling and mobility on days that you're not "doing."

"And, actually just relaxing. Taking it easy. It's not just a running model, we live in a culture where we're always being asked to do more," Nypaver said. "I wish instead of always thinking about doing more, we'd focus on how we want to be more. A lot of us want to be more relaxed and less stressed and happier and enjoy our lives. We need to put our attention on that instead of trying to do so much. It's something I struggle with all the time."

We don't get validation for resting, relaxing, and being present because there's no tangible thing to show for it. There's no "be really calm often" challenge on Strava. But the bigger rewards are great. You just have to trade in immediate dopamine hits for a much more balanced, happier life.

Simple, right?

"One thing I'm doing, and asking my athletes to do, is to write down your intentions," Nypaver said. "One of my intentions is to chill out more this summer and enjoy it. I grew up thinking it's all about running, and I have to go all-in on running. But having other outlets, other things that I like to do, is so important."

When you've reached burnout-an extended period of non-functional overreaching, prolonged rest is the only way to let the body fix itself.

"Once you are overtrained, you need to stop training," Abbotts said. "It's just kind of the bottom line. Maybe some people can get away with greatly reducing their training load, but most of the time you need to stop. You need an extended amount of time off."

There's nothing glamorous about rest. There's no prize money in relaxing. But it's the absolute key ingredient in extended performance, and in a much healthier, happier life.

(02/10/2024) ⚡AMPby Trail Runner Magazine

Try the Spine Race champion’s bonkers treadmill workout

In January, Great Britain’s Jack Scott, 29, clinched a record-breaking victory on the grueling 432-km Pennine Way, winning the Montane Winter Spine Race in 72 hours, 55 minutes and five seconds. After facing setbacks and physical challenges in the lead-up to the race, Scott was forced to go beyond conventional training methods to keep his body healthy and strong, and he shared his training secrets in a blog post with his sponsor, Inov8—revealing a bonkers treadmill workout that played a pivotal role in his success.

Scott’s extraordinary achievement not only eclipsed fellow Brit Damian Hall’s previous men’s record of 84 hours, 36 minutes, and 24 seconds; it also surpassed the overall best set by Jasmin Paris in 2019 (by more than 10 hours), a record considered by many to be unbeatable. Here’s how the ultra runner achieved the impossible.

Training challenges

Scott encountered unexpected obstacles during his final preparations for the 2024 Spine Race. Battling fatigue, IT band issues and a series of daily discomforts, he found himself unable to execute his training plan as desired. Scott strategically adapted his approach, incorporating longer days out on the course with a structured gym program and a distinctive treadmill workout.

Scott’s treadmill routine, aptly named “The Uphill Treadmill Power Hour,” proved to be a game-changer. With a short warm-up preceding an hour-long ascent on the treadmill set at a staggering 25 per cent incline, Scott gained between 1,375 and 1,525m of elevation. During this intense session, he varied his pace, ranging from 5.4 kph to 7.2 kph, and covering a distance of no more than 6 km total. The average pace across all of Scott’s sessions remained around 10 minutes per kilometer.

Maximum effect with minimal mileage

The uniqueness of this workout lies in its efficiency. “What I was doing here was working at Spine Race pace but also exploring a very high-intensity session for my heart and lungs (my heart rate would easily be above 175 [bpm] for 50 minutes during a session like this),” said Scott. This approach allowed him to maintain fitness and train race-specifically, all while keeping the mileage low and manageable.

Scott emphasized the session’s effectiveness in maximizing elevation gains without placing undue stress on his body. The treadmill power hours became a crucial component of his preparation, enabling him to adapt to the challenges of the Spine Race course and the unpredictable conditions he would face.

Try it at home

While most of us aren’t training for a challenge quite as tough as the Spine Race, we can still adapt Scott’s approach to help us crush our race goals. Try tweaking the workout to fit the length of time you have available, and your ability.

Warm up with a 10-minute brisk walk or easy jog.

Crank up the incline on your treadmill, adjusting it until you find a sweet spot—you should feel as though you are putting out a hard, leg-burning effort, but you should still feel comfortable and safe on the treadmill, and as though you can sustain your output for at least fifteen minutes.

Cool down with 10 minutes of very easy running or walking.

For regular runners seeking to inject innovation into their training routines, Scott’s power hour offers a fresh perspective, combining elevation-focused workouts with interval training to enhance race-specific fitness without overloading with excessive mileage.

(02/08/2024) ⚡AMPby Keeley Milne

Five tips from top Canadian ultrarunner Jazmine Lowther

Canadian ultrarunning star Jazmine Lowther has worked through some epic highs and challenging lows since she turned pro in 2022. Lowther took the top spot at the 2022 Canyons Endurance Runs by UTMB, followed by a fourth-place finish in the 2022 CCC race at Ultra-Trail du Mont Blanc (UTMB).

While she managed to speed to second at Transgrancanaria 128K in Spain in 2023, she has also struggled with injuries and biomechanics issues. Lowther recently shared five things she wishes she had embraced when she first dove into ultrarunning; newbies and seasoned athletes alike can learn from her wisdom and suggestions.

1.- Befriend your heart rate

Lowther says she mostly runs by RPE (rate of perceived exertion), but adopting an approach that leans more toward heart-rate-based training has allowed her to “understand my own physiology much deeper, recover properly, and respect pacing.”

Becoming familiar with your heart rate zones can be a valuable skill, and paying attention to your performance metrics, such as pace and endurance, in relation to your zones will help you become a more responsive, tuned-in, healthy athlete. You’ll also be better able to notice if your body needs more rest and recovery time.

2.- Start a training log

While many runners count on apps like Strava to capture their running data, spending time logging more in-depth information about your training is worthwhile, as it provides unique insights over time. “Strava is great (it has most of my training),” says Lowther, “but it doesn’t include how I felt, what workouts I completed, what I ate before/after, caffeinated, fatigue, etc.”

3.- Wear sunscreen

This one is as simple as it sounds. “Protect thy skin,” says Lowther. “Ultrarunning takes you out there for mega-long hours! Slather up!” While most of us know that prolonged sun exposure during outdoor running can increase the risk of skin damage, including sunburn, premature aging and an elevated risk of skin cancer, it can be easy to forget to reapply after hours on the trails. Wearing sunscreen helps to create a protective barrier, reducing the absorption of UV rays and minimizing the potential harm to the skin, and, as Lowther notes, is an essential precautionary measure (in all kinds of weather) for maintaining skin health.

4.- Find your baseline

Lowther suggests integrating benchmark training runs into your routine to establish an initial baseline. The process involves finishing a predetermined course or distance to use as a reference tool and provides a basis for assessing your performance and comparing it to others in terms of time, pace, or other relevant metrics. “I suppose I’ve done this in an unstructured way (Strava segments anyone?) but seriously, repeating workouts in the same location/distance is great for checking in on things,” she says.

5.- Have patience in the process

Focus on consistency and long-term goals and gains. Consider each run and workout as an investment in your fitness and training bank, even if it didn’t go exactly as planned. “One day at a time, year over year,” says Lowther. “Consistency, is that you?”

(02/08/2024) ⚡AMPby Keeley Milne

How Little Strength Training Can You Get Away With?

To be a maximalist, you must first be a minimalist. That's an aphorism I first heard from Michael Joyner, the Mayo Clinic physiologist and human performance expert, and it resonates. To truly reach your potential in one or a few areas, you have to be disciplined about all the other ways in which you could fritter away your valuable time and energy. Excellence requires tough choices.

All this is to say that when it comes to strength training, I'm not ashamed to admit that my number one question is "How little can I get away with?" I'm fully convinced that strength training has important benefits for health and performance, and I recognize that lifting heavy things can be a source of meaning and self-mastery. But I've got miles to run before I sleep and, metaphorically, a bunch of errands to run before my kids get home, so a recent review in Sports Medicine caught my eye. An international group of researchers, led by David Behm of Memorial University of Newfoundland and Andreas Konrad of Graz University in Austria, sum up the existing research on minimalist resistance training: how low can you go and still get meaningful gains in strength and fitness?

For starters, let's acknowledge that making meaningful gains is not the same as optimizing or maximizing your gains. There's a general pattern in the dose-response functions of various types of exercise: doing a little bit gives you the biggest bang for your buck, but adding more training leads to steadily diminishing returns (and eventually, for reasons that aren't as obvious as you might think, a plateau). Those diminishing returns are worth chasing if you're trying to maximize your performance. But if your goal is health, more is not necessarily better, as we'll see below.

In a perfect world, you'd like to see a systematic meta-analysis of all the literature on minimalist strength training, meaning that you'd pool the results of all the different studies into one big dataset and extract the magic training formula. Unfortunately, the resistance training literature is all over the map: different types of strength training, study subjects with different characteristics and levels of experience, different ways of measuring the outcome. That makes it impossible to meaningfully combine them in one dataset. Instead, Behm and Kramer settled for a narrative review, which basically means reading everything you can find and trying to sum it up.

Their key conclusion is that "resistance training-hesitant individuals" can get significant gains from one workout a week consisting of just one set of 6 to 15 reps, with a weight somewhere between 30 and 80 percent of one-rep max, preferably with multi-joint movements like squats, deadlifts, and bench press. That's strikingly similar to a minimalist program I wrote about a couple of years ago: that one involved a single weekly set of 4 to 6 reps, but the lifting motions were ultra-slow, which heightens the stimulus. You don't even necessarily have to lift to failure, though you probably need to get within a couple of reps of it.

The data that Behm and Kramer looked at came from studies that typically lasted 8 to 12 weeks. One of the unanswered questions is whether such a minimalist program would keep producing gains on a longer timeframe. You'd clearly need to continue increasing the weight you lift to ensure that you're still pushing your body to adapt. But do you reach a point where further progress requires you to increase the number of sets, or the number of workouts per week? Maybe-but it's worth recalling that we're not trying to maximize gains here, we're just trying to achieve some hazily defined minimum stimulus. For those purposes, the evidence suggests running through a rigorous full-body workout once a week is enough to maintain a minimum level of muscular fitness.

There's another, less obvious angle to minimalist strength training that researchers continue to grapple with. Duck-Chul Lee of Iowa State and I-Min Lee of Harvard, both prominent epidemiologists, published a recent review in Current Cardiology Reports called "Optimum Dose of Resistance Exercise for Cardiovascular Health and Longevity: Is More Better?"

The question echoes a debate that flared up a decade or so ago about whether too much running is bad for you, in which Duck-Chul Lee played a key role. Back in 2018, he also published a study of 12,500 patients from the Cooper Clinic in Dallas which found that those who did resistance training were healthier-but that the benefits maxed out at two workouts a week, and were reversed beyond about four workouts a week. At the time, I assumed the result was a fluke. But the new article collects a larger body of evidence to bolster the case. The newer data suggests that about an hour of strength training a week maximizes the benefits, and beyond two hours a week reverses them. Lee and Lee hypothesize that too much strength training might lead to stiffer arteries, or perhaps to chronic inflammation.

Now, when Duck-Chul Lee and others produced data suggesting that running more than 20 miles a week is bad for your health, I was brimming with skepticism and went over the data with a fine-tooth comb. I'm similarly cautious about these new results, and have trouble believing that there's anything unhealthy about doing three weekly strength workouts. But they do put the idea of minimalist strength training in a different light. Maybe you're not maximizing strength or muscle gains, but it's possible that you're optimizing long-term health-especially if the reason you only hit the gym once or twice a week is that you're too busy hitting the trails.

(02/03/2024) ⚡AMPby Trail Runner Magazine

Four runners share their mental health stories

Many runners find their sport is not only a way to gain physical resilience, but also a powerful ally in the path toward mental well-being. The road to mental health isn’t solitary, and witnessing others share their challenges and successes can be uplifting and inspiring.

From pros to amateurs, athletes are speaking out about their struggles and triumphs with mental health. Here are four runners to follow who are also mental health advocates.

1.- Alexi Pappas

Pappas is known for being a remarkable athlete (she ran the 10,000m for Greece at the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro), but she also boasts credentials as a renowned author, filmmaker, and mental health advocate. Pappas opened up about mental health in 2020: after working toward and achieving her Olympic dreams, her mental health spiralled, and she was eventually diagnosed with severe clinical depression, which was compounded by injuries, a lack of sleep and her own reluctance to take a break from training.

Pappas authored her first book in 2021: Bravey: Chasing Dreams, Befriending Pain, and Other Big Ideas, highlighting her triumphs and challenges in sports and life, and encouraging readers to be “braveys” in pursuing their passions. She continues to advocate and be a source of hope to others on social media.”What if we athletes approached our mental health the same way we approach our physical health?” Pappas asks.

Former American steeplechaser turned elite trail runner, Ostrander uses her Instagram platform to share mental health and eating disorder awareness and advocacy.

In 2021, Ostrander returned to professional competition after being sidelined with multiple injuries for the previous 18 months. During this time, she was hospitalized for treatment of an eating disorder. Ostrander qualified for the U.S. Olympic Trials, where she ran a personal best of 9:26.96 in the 3,000m steeplechase, before deciding to take a year-long break from professional running to prioritize her own mental health.

Ostrander returned to racing in 2023, and made a shift to the trails, running to ninth place at the Mammoth 26K in California in September.

3.- Evan Birch

Canadian ultrarunner and mental health advocate Evan Birch shares an unflinching look at his mental health journey on social media as he works to destigmatize the conversation around mental wellness. Birch is a former 911 dispatcher from Calgary who has been running on trails for more than a decade, and who most recently conquered Western Canada’s first 200-mile race, The Divide 200, in September 2023.

A busy father to young children, Birch recently collaborated with filmmaker Dylan Leeder to create Running Forward, a documentary illuminating the intersection between running and mental health.”It is more important to me now that I meet the truth within me, than it is to make other people comfortable with how I am,” Birch says on social media. “The gifts I have received from allowing myself to be sad are so plentiful.”

4.- Denoja Uthayakumar

From Scarborough, Ont., Uthayakumar is no stranger to hardship, but she has taken her experiences and built a social platform where she can advocate for individuals from similar backgrounds. Uthayakmar is a cancer survivor, body positivity and mental health advocate and was Canadian Running’s pick for our 2023 Community Builder of the Year award.

Uthayakumar was born into a Tamil family, and was diagnosed with thyroid cancer at age five; she shares her physical and mental health challenges alongside the joy that running and the community around it bring to her. “This year pushed me. It broke me down. It challenged me to no end,” Uthayakumar says on Instagram. “It was hard, but I rose higher with my running journey, and was able to share more of my story during my healing while being a survivor.”

(01/31/2024) ⚡AMPby Keeley Milne

This ultrarunning champ’s 5K workout will make you faster

No matter what distance you're training for, you'll boost speed and running economy with this fun, fast session.

Whether you are training for a 10K PB this season or hoping to run your first ultra, you’ll benefit from adding a speedwork session (like this one) to your training toolbox. Utah-based running coach, personal trainer and ultrarunning champ Rhandi Orme has a workout that she likes to prescribe to her athletes, as well as using herself (and she suggests modifications for all levels of runners).

“This is a workout that long-distance athletes can benefit from,” she told Canadian Running. “Having top-end speed on the shorter distances improves runners’ VO2 max and running economy, which helps us run faster and stronger at longer distances, too.

The workout

Warm up with 15-20 minutes of easy running, followed by dynamic drills or stretches.

Run 5 x 2 minutes at 5K goal pace, with two minutes of recovery jogging between intervals.

Run 4 x 2 minutes at 5K goal pace with a minute’s recovery jog between intervals.

Finish your speedwork with a fast mile, to see what you can do on tired legs (all effort-based for this final interval). “Don’t look at your watch. Pretend you are running the last mile of your next 5K race,” says Orme.

Cool down with 10-20 minutes of easy running.

*Bonus: any time after this hard effort (but on the same day) is ideal for your leg-strength training session.

Modifications

Shorten or extend intervals based on your current level of fitness. Orme suggests that beginners start with 4 x 30 seconds (at goal pace) and then 2 x 60 seconds. “You can also increase the recovery time between intervals,” says Orme. For newer runners, reducing the “fast-finish” mile to a “fast-finish” half-mile is a great option, and Orme suggests playing with the recovery time and the number of intervals based on your current fitness.

“Once the workout begins to get more comfortable, you can increase the intervals and reduce the recovery, working your way up to the full workout,” says Orme. “I would recommend doing this workout every other week, until you see a noticeable improvement.” For experienced runners hoping to add more volume, she suggests extending the warmup and cooldown.

Remember to follow a harder training day like this one with a rest day or easy-run day.

(01/31/2024) ⚡AMPby Keeley Milne

7 Legit Benefits of Running At Night—And How To Do It Safely

It was around mile two of the Joshua Tree Half Marathon that I started to hear animals I couldn’t see. Was that a horse? I wondered (and hoped). The daylight was officially gone.

But I realized that as spooky as night running might be, it also creates an eerie kind of magic. Lights twinkled in the valley below the hilly path I was climbing, but all around me it was pitch black, aside from the few feet of sandy trail that each runner’s headlamp illuminated. With nothing else to see, all I had to focus on were my own footsteps and my breath—and how I could race through the desert as quickly as possible.

Amie Dworecki, B.S., M.A., MBA, Amie Dworecki, B.S., M.A., MBA, is a running coach and founder of Running With Life.

Brad Whitley, DPT, physical therapist at Bespoke Treatments in Seattle

Marnie Kunz, CPT2, USATF- and RRCA-certified running coach

Most long-distance races take place in the morning, but this half marathon starts right around sunset. Because the scenery of the course is a tad monotonous, the race organizers embrace the adrenaline rush you can get from running under the stars.

I joined as part of a press trip sponsored by Nathan Sports, Skechers, and Swiftwick. The experience reminded me that even when the days are short during the winter and pushing your pace after the sun goes down becomes the norm, night running can be its own unique adventure.

The more I looked into running at night, the more advantages I found—even if you need to take a few extra safety precautions when you’re lacing up.

The perks of running at night

What are the main benefits of night running? Here are a few of the top reasons to get in a nocturnal workout.

1. The temperature is cooler

Earlier in the day before the Joshua Tree race, I’d been cowering from the heat anytime the sun touched my skin. But once it was dark out, the desert air got so cool that my sweat-wicking T-shirt barely had any work to do.

As it turns out, temperatures around 40° Fahrenheit are ideal for long-distance running, largely because our hearts don’t have to work quite as hard to pump our blood to cool us down, according to a May 2012 study in PLOS One.

Even if the mercury doesn’t get quite that low after dark in a hot or humid climate, night running after sunset (or, alternatively, heading out before sunrise) is clearly the way to go to nab those cooler running temperatures.

2. Your body’s more ready to run

Running shortly after rolling out of bed can sometimes feel like wading through molasses. It’s no surprise why: You’ve just been lying stationary for hours, so your body temperature and mobility aren’t exactly ideal.

3. It might feel easier

The dark can be a secret weapon for runners. One August 2012 study in the Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology on optic flow (our perception of our movement in relation to our surroundings) suggested that because we can’t see as far in the dark, we feel like we’re going faster because close objects seem to pass by more quickly than those in the distance.

Even though your watch might not record any speedier miles, running in the dark can be a helpful confidence boost when you get the sense that you’re zooming along.

4. Night running can help you sleep

How can running at night affect your sleep quality? Despite rumors to the contrary, there’s some evidence to suggest evening runs might actually help you get deeper zzzs.

An October 2018 meta-analysis in Sports Medicine found that as long as you finish running more than an hour before your bedtime, it most likely won’t mess with your sleep quality. Instead, it could actually help you spend slightly longer in those restorative deep sleep stages.

Anecdotally, some people say they also seem to fall asleep faster.

That’s something to experiment with, according to certified running coach Amie Dworecki, CPT. Everybody’s different, so you might need to find out what works best for your own circadian rhythm.

5. You’re likely better fueled

Eating can be tricky for morning runners—you’ll run better with some food in your stomach, but if you don’t give yourself enough time to digest, you might run into GI issues.

At night, though, you should be fairly well-fueled from noshing all day, Dworecki says. Just be sure to have a snack to top off your carbohydrate stores before heading out the door, says certified running coach Marnie Kunz, CPT.

6. It’s more peaceful

Depending on where you run, during the day you might feel like you’re playing Frogger with traffic and pedestrians, dogs, and baby strollers. At night, most of those hurdles typically fade away.

“It's really almost a meditative experience because of the quiet and solitude,” Dworecki says. “It can really add relaxation to your running.”

7. You have more options

Because you’re less likely to have a certain time you need to be back by at night than you would in the morning, it’s easier to choose your own adventure based on how you’re feeling. You can add a couple extra miles if you feel like it, or end early and walk home instead.

Running at night vs. morning: How to choose

Many runners swear by their morning miles. But obviously, the a.m. hours aren’t the only time to run. How do you know whether night or morning runs will serve you best?

For some people, it’s purely logistical: The best time to get in a run is whenever you can run. But if you have a choice, it might help to pay attention to the natural ups and downs in your energy levels.

“If you're a night person, you can actually feel better or more energetic if you're running in the evenings,” Dworecki says. Or, she adds, you might be able to use running to give yourself an energy boost at a time when it would typically dip.

If you’re someone who needs camaraderie to lace up, one of the benefits of night running is you’re more likely to find a group run to join after the work day, or convince a friend to join you for a few social miles.

Even if you’re alone, night running can also give you more of a thrill than the chore-like approach you might take to morning runs.

“It's kind of an adrenaline rush running at night sometimes,” Kunz says.

On the other hand, running in the morning can be safer because there’s typically more people on the street, and more daylight means you’re more visible to cars.

Running first thing in the morning can also make you more consistent—even if you get stuck working late hours or friends convince you to head out for a happy hour, your workout will already be done.

Safety precautions for night running

1. Make sure you have enough light

Unless you know you’ll be running in a well-lit area, you’ll need to bring or wear your own running lights, Dworeck says.

I ran the Joshua Tree Half Marathon with the lightweight Nathan Sports Neutron Fire RX 2.0 Runner’s Headlamp, which securely attached to my forehead, and gave me 250 lumens of light in any direction I turned. Although it took me a little while to find the right spot on my forehead so it didn’t slip or bounce, once I did, I forgot it was even there.

If the thought of wearing a light on your head doesn’t sound appealing, you can also opt for a chest lamp or carry your own small flashlight. There are even have lights you can put on your shoes or your gloves, Dworecki says.

2. Stay visible to cars

Before the race, I was sent Nathan’s Laser Light 3 Liter Hydration Pack, which has a genius double-duty design that gives you a place to stash water as well as lights on the back in case you’re running anywhere there might be cars.

If you don’t have actual lights on your body, at least be sure to wear bright reflective gear so drivers can easily see you. Light-up reflective vests aren’t your only option—these days, many pieces of running gear stylishly incorporate reflective details, and there are even several reflective running shoes.

3. Consider leaving your headphones at home

Night running probably isn’t the right time to zone out to a podcast. Because you won’t be able to see as well, it helps to keep your other senses sharp.

“Watch your use of headphones just to be aware of what's around you,” Dworecki says.

4. Let someone know where you are

Although running when the streets are quiet can feel less stressful than during busier, noisier parts of the day, empty roads or trails can also be dangerous.

“Let someone know where you're going or share your run so they can track you,” Kunz says.

Apps like Strava let you proactively send your location to select contacts in real time. Alternatively, you can choose to stick to sidewalks or a track where you know other people will be out and about.

How to motivate yourself to run at night

After a long day, forcing yourself to get off of your warm couch and out into the dark doesn’t always sound super appealing. Kunz suggests making a promise to yourself to simply run 10 minutes—it’s just a little exercise snack that doesn’t feel like too much pressure.

“You know you can turn back, but once you're out the door, usually you'll feel okay and just keep running,” she says.

Dworecki adds that for some people, it’s easier to run right from their workplace. When I was training for an ultramarathon, for instance, I used to run home four miles from my office every night so that I didn’t waste half an hour commuting on the subway—my commute was my run (and it only took slightly longer). Then, once I stepped in the door, I could just relax without having to convince myself to leave again.

It can also be helpful to make night running more social by joining a group run or turning it into a date with a friend to catch up after work.

“[It] makes your run more fun and it gives you some accountability,” Kunz says. Even running with a dog can help a night run feel less lonely.

FAQ

1. Do I need a light to run at night?

If you’re going on trails or areas without ample street lamps, you’ll want to bring your own light source with you to make sure you can see where you’re going and what you’re about to step on. The most popular option among runners is a headlamp.

2. Can running at night help in managing stress?

Running is always a good stress release—the extra blood flow to our brain triggers a release of dopamine and endorphins, sometimes leading to the famous “runner’s high.” These benefits might be especially welcome at night.

“It's a great way to kind of blow off steam at the end of the day, and help unwind and relax before going to sleep,” Kunz says.

3. Is it bad to run at 10 p.m.?

Sometimes the only chance you have to fit in a workout is after many people go to bed. Dworecki says that sometimes when she’s struggling with insomnia, she might head out for a run around 1 a.m.

Just know that working up a sweat with intense exercise, like running vs. walking, for instance, will raise your heart rate pretty high, so be sure to give yourself enough time (at least an hour) to wind down after you're finished so it doesn’t mess with your sleep.

No matter when you get back home, do a cooldown, take a hot shower, eat some food, and settle in for the night knowing you’ve gotten all those longevity benefits and health perks.

(01/28/2024) ⚡AMPHow to Use the Run/Walk Method for Faster Times and Longer Distances

Adding walk breaks to your training runs and races just might provide your ticket to faster finishes or longer distances.

Many runners have a few dirty little secrets, like not quite making it to the bathroom or chafing in unmentionable spots. But one thing many runners also won’t admit to... walking. That is, unless you embrace the run/walk method, which involves adding precisely planned walk intervals to your runs.

The run/walk method can offer runners many benefits, including helping to fight off fatigue. It can even help you clock faster finish times and maybe even win a race that you thought was out of reach. Just look to Marc Burget for evidence. A ultramarathon run/walker, Burget, 50, won the 2016 Daytona 100 (miles) in 14 hours and 14 minutes which, at the time, was a course record.

“The idea that you should move from walking to running is the wrong framework,” Burget, director of operations at Bailey’s Health and Fitness in Jacksonville, Florida tells Runner’s World. “Instead, putting walks in my race plans allows me to go the whole 100 miles without becoming tired.”

Research supports Burget’s experience. According to a 2016 study published in the Journal of Science and Medicine in Sports, of the 42 runners studied, those who used the run/walk method in a marathon reported less muscle pain and fatigue and finished with similar times, compared to those who only ran.

So, while it’s true that runners typically move faster than walkers, it’s also true that during long races or training runs, taking well-timed walk breaks can help you reach your goals. To understand the run/walk method, here are common myths and truths about the training and racing strategy, plus how to test out the system for yourself.

Myth: Only Slow Runners Use the Run/Walk Method

Truth: Slow Walks Support Faster Finishes

In recent years, more runners and experts have learned that zone 2 running (that is, lower effort runs), improves many elements of fitness and supports your ability to run both long- and short-distance races without fatiguing as quickly.

Whatever distance you race, it’s important to manage your energy levels from the start, so you can make it to the finish without bonking. While fuel plays a role in maintaining energy, how you pace a race is also crucial.

“There’s a myth that a lot of runners perpetuate about banking time,” Chris Twiggs, chief training officer at Galloway Training Programs tells Runner’s World. “The time bank doesn’t exist. The bank that does exist is the bank of energy. When you walk during your run, you are investing in the bank of energy.”

Burget agrees. The first time he ran 100 miles, he planned to run the whole way, but because of exhaustion, he ended up walking about 20 miles. Once he started to train with the run/walk method, he cut his walking down to 10 to 15 miles thanks to 30-second walk intervals. Now, with experience, most of his ultras include eight to 10 miles of walking and he either alternates three minutes of running and 30 seconds of walking, or 0.3 miles of running and 30 seconds of walking, depending on his race strategy and goals.

How to use the run/walk method to get faster:

If you have your mind on a PR, the run/walk method could help you get there. You just have to practice.

“Your walk should be brisk, but not work,” says Burget. “You want your heart rate to drop down.” You also want to give your muscles a break from the intense effort to allow for a midrun recovery.

Because you’re walking, you also need to make your run intervals faster than if you’re going for a steady-state run. For example, let’s say you want to average an 8-minute per mile pace for a marathon. Try running a 7:40 pace for nine-tenths of a mile, then walk for 30 seconds, so that you finish a mile in eight minutes. “You’re not losing 30 seconds,” Burget explains. “You’re moving forward, but part of your pace is a walk.” Likewise, if you want to maintain an 11-minute pace, you could do a 40-second walk every three minutes of running at around a 10:20 pace per mile.

If you have been running for a bit but you don’t know where to start with your interval ratios and paces, do a “magic mile” run, both experts say. This will help set your goal pace for a race. With that magic mile time in mind, set your interval ratios, keeping in mind that generally, the faster your average pace, the longer your run intervals. For example, if you’re aiming for an 8-minute mile average pace, you may run three minutes and walk 30 seconds. But if you’re aiming for a 10-minute mile average pace, you may run 90 seconds and walk 30 seconds.

If you’re a beginner, Twiggs suggests starting your workouts by running for 30 seconds and walking for 30 seconds. If that seems too easy or you can feel yourself wanting to run more keep the 30-second walk, but run slightly longer between walks, he says.

You can keep track of your ratio using time or distance. Twiggs uses time, while Burget often pays attention to the mile markers in his races, walking for the last tenth of each mile. Play around with what works best for you.

“It took me a few months to figure out the ratio that works for me,” says Burget, who has also run a 2:50 marathon by alternating six-minute runs and 15-second walks.

When you want to actually increase your average pace per mile, do another magic mile to see how much faster you can go, and then either increase the speed of your run intervals, add more time to the run intervals, or cut down on the time of your walk breaks.

Myth: Only Beginners Take Walk Breaks

Truth: The Run/Walk Method Can Work for Everyone

While there are no statistics on how many runners use walks in their training or in their races, how long they’ve been running, or how “tired” any runner is when they walk, we can confidently say that runners who strive to incorporate walks into their runs are all ages and all levels of fitness.

Both Burget and Twiggs run ultras, something less than 1 percent of Americans did in 2023, and ultrarunners typically aren’t new to the running game.

In fact, planning your run/walk strategy for races can take practice so many experienced runners and walkers may turn to it. For example, Burget has learned to time his walks to match the location of hydration stops and elevation gain in his ultras so he can maximize his running potential. But that came with lots of practice using the run/walk method.

How to use the run/walk method to advance your race results:

Always study the details of your upcoming race and consider creating a strategy to match walks with water stations and hills. “Looking at the landscape when planning your run/walk is important,” says Burget.

“Walking hills is smart because we want to do what we can to conserve our energy so that when we expend our energy we get the most bang for our buck,” says Twiggs.

Running up hills during training will help you build leg strength, but in a race it could decrease your pace (and finish time) because it takes so much effort, adds Twiggs. Without planning, you might find yourself running up a hill (wasted effort) and then walking a descent as you recover. Planning ahead can help you flip that to maximize your energy and increase your speed.

The point: Go into your race with a clear plan that has specifically planned walk breaks so you’re not just slowing it down when you feel like it, which could be a detriment to performance, Twiggs explains. Playing around with your run/walk ratios during training will also help you set this in stone come race day.

Myth: Being a Run/Walker Will Limit Your Race Opportunities

Truth: Walks Can Help You Participate in Longer, Harder Races

The reason running is defined as “high” intensity while walking is considered “low to moderate” intensity is because it takes more energy to run than to walk. Typically, your heart beats more frequently when you run than when you walk in order for your body to produce that extra effort.

Break up those runs with walks, though, and you are giving your heart, muscles, bones, and joints a break. It’s helps with the deposit into your energy bank, as Twiggs says. The benefit of those deposits? You may be able to add to your race schedule, say by running a half marathon instead of a 10K, if that has seemed out of reach. If you think you can’t run a marathon, could you run/walk one?

To prove the point that adding walks into long runs can cut down on fatigue and help you go longer (or even run more frequently), take another example from Burget: In 2023, he ran seven marathons in seven consecutive days, aiming for a sub-three-hour finish for each race. While he ran just over three hours in two of the races, his other times ranged from 2:52:15 to 2:58:57. “I used the same interval for each race,” Burget says, “a 20-second walk during each mile.”

How to use the run/walk method to run longer:

While you experiment with run/walk intervals, try to notice how you feel in comparison to runs that don’t include walks. Do you feel like you can increase your typical run distance or duration by a half-mile or 10 minutes?

To progress to longer distances, you have a variety of options: You can increase the pace of your runs or shorten the walk breaks you take, says Twiggs, while still running for the same overall amount of time. (This will increase your average pace.) Or you can maintain your pace and your ratio, but add more rounds of intervals, so you run for a longer duration and therefore, distance, which may come easier than only running because of the added recovery element. Do what feels best for you.

In addition to helping you conquer longer distances, the run/walk method might increase your race options by also allowing you to take part in multi-day events, such as runDisney weekends or Philadelphia’s Marathon Weekend, which includes an 8K, half, and marathon.

While some runners, of course, take part in these events without using the run/walk method, “we’ve seen anecdotally that for millions of runners, this allows them to run races they would not have otherwise considered,” says Twiggs, because it can allow for that quicker recovery.

(01/28/2024) ⚡AMPA Guide to Effective Goal Setting

While some folks might navigate life with less of a plan, athletes, particularly runners with competitive ambition, need structure to their goals. Goal setting is as natural to you as accidentally clicking "Sign Up" on Ultrasignup; before you know it, your goals are on paper!

However, even for goal-oriented individuals like yourself, there's always room to refine your goal-setting approach to maximize your potential. And that starts with a proper perspective. A mentor once phrased it as follows: "It's not solely about achieving the goal,l but rather about the person you must become to attain it."

This perspective emphasizes the growth process, with the goal as a guiding target. It liberates us from negative thinking and self-blame if we miss our target. Many successes remain if we do the work and grow in our attempts. The only true failure occurs when we fail to put in the effort or set the wrong initial goal. Effective goal setting can help you avoid both.

As we immerse into the new year, lottery selections, and the process of finalizing race schedules and objectives for 2024, I aim to share my guide on effective goal setting that I apply myself, teach our coaches at CTS, and work with many of my athletes through. As a coach, imparting the skill of effective goal setting to my athletes is among the most invaluable contributions I can make. It is the foundation for a year or a lifelong pursuit, marked by personal growth and self-discovery.

Setting the Stage: Your Trail Running Vision

A good starting place for any goal is to reflect on your long-term vision as a person and athlete. What are your ultimate aspirations in the sport? This could include completing specific races, achieving certain performance milestones, or simply experiencing personal growth through running. Consider what truly motivates you. Is it the joy of running on scenic trails, the desire to push your physical and psychological limits, the thrill of competition, the sense of belonging in a community, the means of coping with life's pressures, or the person you're becoming in the process? Understanding the answers to these questions will help you set meaningful goals.

After gaining clarity, put your vision into writing and make it a habit to revisit it frequently. Keep this vision statement in front of you by putting it in places you will see on a regular basis, such as your bathroom mirror, phone screen saver, or calendar reminders that alert you throughout the day or week. Remember that your vision may evolve as you continue to grow and develop. Having a well-articulated statement of purpose is a powerful tool that can assist you in refocusing when necessary. We've all faced challenging seasons, and reconnecting with the motivations behind our involvement in the demands of trail and ultrarunning can help us maintain a positive outlook and a strong sense of direction. In fact, it's not uncommon for my athletes to revisit these purpose statements even during the midst of a challenging ultra event.

Types of Goals

Before we get to the how-to's, let's define some terms and build a good framework. There are various types of goals that trail and ultrarunners commonly pursue. One prevalent category of goals is outcome goals, which involve specific race-related achievements such as finishing a race within a designated time or securing a particular placement. Outcome goals provide a clear target and can be highly motivating, often presenting a binary pass-or-fail outcome. For instance, an outcome goal might be, "I want to complete a 100-mile race in under 24 hours."

Another common type of goal relevant to all endurance athletes is performance goals. These goals revolve around quantifiable metrics that assess speed, skills, or endurance. Performance goals are frequently integrated into training programs aimed at achieving outcome goals. An example of a performance goal is, "I want to maintain a sub-10-minute mile pace during my endurance runs on my local trail."

Process goals, on the other hand, concentrate on the specific actions and steps required for success. A process goal should accompany every outcome or performance goal. For instance, if the outcome goal is to complete a 100-mile race in under 24 hours, a suitable process goal might be to maintain consistent daily training for a six-month period. While this process goal may lack detailed specifics, it is arguably an athlete's most crucial goal. It demands hard work, discipline, and a smart training approach to sustain consistency. Even if the athlete falls short of their target, the process can be a success if it has made them a better athlete and individual throughout the journey. Ultimately, progress and growth matter more than the final result. The result is typically a celebration of the process.

Intertwining Motivations

In addition to outcome, performance, and process goals, intrinsic and extrinsic motivations are intertwined. Intrinsic motivations are internal and revolve around the sheer joy and satisfaction derived from running. Many trail and ultrarunners find intrinsic motivation in "exploring new trails in the natural surroundings," reflecting their love for trail running.

External motivations are driven by outward factors like race medals, winning, Ultrasignup rankings, and recognition from others. While these external factors can motivate in the short term, they may lack long-term commitment. Balancing extrinsic and intrinsic motivations for a sustainable and fulfilling running experience is crucial.

Understanding the motivations behind our goals plays a critical role in enhancing and complementing our pursuit of these goals.

SMART Goal Framework

The SMART goal framework is a widely recognized and effective approach to goal setting that provides a structured and systematic way to define and achieve objectives. This framework is particularly valuable for trail and ultrarunners looking to set clear and attainable goals in their training and racing endeavors. Let's break down what SMART stands for and how it can be applied to running goals:

S - Specific: The first step in setting a SMART goal is to make it specific. A specific goal is well-defined and leaves no room for ambiguity. For trail and ultrarunners, specificity might involve clarifying the race distance, terrain type (e.g., mountainous trails), and location. Instead of a vague goal like "I want to run a trail race," a specific goal would be "I will complete the Silver Rush 50 Mile race in the Rocky Mountains."

M - Measurable: Goals should be measurable, allowing you to track your progress and determine when you've achieved them. In trail running, measurability can be related to time, distance, pace, or elevation gain. For example, "I plan to finish a 100K trail race in under 12 hours" is a measurable goal because it provides a clear benchmark for success.

A - Achievable: An achievable goal is realistic and attainable within your capabilities and resources. While aiming high is admirable, setting unrealistic goals can lead to frustration and inconsistent efforts in your pursuit. Assess your fitness level, available training time, support network, and other commitments to ensure your goal is achievable. For instance, "I will complete a 100-mile ultramarathon within one year, given my current training routine and available time" is achievable if it aligns with your abilities.

R - Relevant: Your goal should reflect your broader objectives and aspirations. It should align with your values, interests, and long-term plans. In trail running, a relevant goal might involve selecting races that match your passion for rugged terrain or adventure. For instance, "I want to compete in challenging mountain trail races because I'm passionate about conquering steep ascents and descents" is a relevant goal for a mountain-loving trail runner.

T - Time-Bound: Lastly, every goal should have a timeframe for completion. A time-bound goal creates urgency and helps you focus on your training and racing schedule. For example, "I intend to run a marathon-distance trail race within six months" sets a clear timeframe for your goal.

Trail and ultrarunners can transform vague aspirations into well-defined and achievable objectives by applying the SMART goal framework. This structured approach enhances motivation and improves the likelihood of success in training and racing pursuits. Whether you aim to complete a big race, achieve a personal best, or explore new trails, SMART goals can guide your process.

Define Your Goals