Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #Courtney Dauwalter

Today's Running News

The GOAT Returns: Courtney Dauwalter Takes on the Cocodona 250 Mile Ultra

Courtney Dauwalter, widely regarded as one of the greatest ultrarunners of all time, is set to take on the formidable Cocodona 250—a 250-mile ultramarathon stretching from Phoenix to Flagstaff, Arizona. This grueling race, commencing at 5 a.m. PT on Monday, May 5, 2025, marks her first race over 200 miles since 2020 .

Born on February 13, 1985, in Hopkins, Minnesota, Dauwalter’s athletic journey began with cross-country skiing, where she became a four-time state champion during high school. She continued her athletic pursuits at the University of Denver on a cross-country skiing scholarship and later earned a master’s degree in teaching from the University of Mississippi in 2010 . Before turning professional in 2017, she taught middle and high school science in Denver.

Dauwalter’s ultrarunning career is marked by remarkable achievements. In 2023, she became the first person to win the Western States 100, Hardrock 100, and the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB) in the same year . Her victories often come with record-breaking performances, showcasing her exceptional endurance and mental fortitude.

The Cocodona 250 is a point-to-point race that challenges runners with diverse terrains, including desert landscapes, mountainous trails, and significant elevation changes. For Dauwalter, this race presents an opportunity to explore new limits. “I haven’t run a race over 200 miles since 2020,” she noted, highlighting the significance of this endeavor .

Her preparation for Cocodona has been promising. She began her 2025 season with a victory at the Crown King Scramble 50K, indicating strong form leading into this ultramarathon .

A distinctive aspect of Dauwalter’s approach is her embrace of the “Pain Cave,” a term she uses to describe the mental space where she confronts and overcomes extreme physical challenges. She visualizes it as a place to “chip away” at her limits, finding growth through adversity.

Unlike many elite athletes, Dauwalter eschews strict training regimens and coaching, opting instead for an intuitive approach that prioritizes joy and curiosity. Her philosophy centers on listening to her body and finding happiness in the process, which she believes enhances performance.

Courtney Dauwalter’s journey from a science teacher to an ultrarunning icon serves as an inspiration to athletes and non-athletes alike. Her achievements demonstrate the power of resilience, mental strength, and a passion-driven approach to pursuing one’s goals.

As she embarks on the Cocodona 250, the ultrarunning community watches with anticipation, eager to witness another chapter in the extraordinary career of this remarkable athlete.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

How Trail Races Are Redefining the Running Boom

In recent years, the global running community has seen a dramatic shift in where and how people race. While traditional road marathons still draw massive crowds, trail races—once considered a niche segment—are experiencing a surge in popularity. From rugged mountain paths to dense forests and desert crossings, more runners are lacing up to compete off-road, seeking challenge, solitude, and a deeper connection to nature.

The Rise of Trail Runnimg

Trail running has grown rapidly in the past decade, but its momentum accelerated after the COVID-19 pandemic, when road races were canceled and people turned to nature for both fitness and sanity. What started as necessity turned into passion for many, and race organizers took note. Events that once attracted a few hundred now sell out in minutes.

Today, races like the UTMB (Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc) in France, the Western States 100 in California, and the Ultra-Trail Cape Town in South Africa are globally recognized—drawing elites and amateur runners alike. These races offer not just distance and competition, but elevation, terrain variety, and breathtaking backdrops.

More Than a Race—A Journey

Unlike a typical 10K or marathon, trail races often require navigation, climbing, and mental fortitude. Weather and terrain can change quickly. Aid stations may be miles apart. But it’s exactly these demands that attract runners hungry for something deeper than just speed or medals.

“There’s something primal about running in the wilderness,” says 2023 UTMB finisher Sara Delgado. “It’s not just about pace—it’s about presence.”

Elite Trail Runners on the Rise

Top road racers are taking notice too. Marathoners like Jim Walmsley and Kilian Jornet have made trail dominance a core part of their legacy. Meanwhile, athletes like Courtney Dauwalter are redefining what endurance looks like, regularly winning 100-mile races overall—not just in the women’s field.

Sponsors have followed the talent. Major brands are investing in trail running gear, shoes, and media coverage, making the sport more visible and viable for elite athletes and growing its appeal for weekend warriors.

Global Appeal

From Portugal’s Douro Valley to the jungles of Costa Rica and the peaks of Japan’s Alps, trail races are being launched in every corner of the world. Many combine local culture with intense landscapes, turning these events into destination experiences.

Travel-based trail running adventures—3-day stage races, run-and-yoga retreats, and culinary trail tours—are also gaining traction. It’s no longer just a race, but a way to see the world, one footstep at a time.

What This Means for the Future

Trail running is redefining the running boom by offering what many road races cannot: quiet, challenge, authenticity, and unfiltered connection to the earth. As the sport continues to grow, it’s likely we’ll see more hybrid athletes, crossover races, and increased visibility across the media.

The road will always have its place, but for a growing number of runners, the real race begins where the pavement ends.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Camille Herron and the Wikipedia Controversy: Integrity in Ultrarunning Under Scrutiny

Update: after reading our article Camille sent this to MBR "Individuals are violating World Athletic rules and publicly claiming they broke my records. It’s undermining the integrity of the sport and devaluing those who adhere to the rules and the ratified record holders, including me.

I hope Yiannis’s statement provides added clarity who’s behind the push to disregard the rules and retaliated against me."

Camille Herron recently addressed the Wikipedia controversy on her Facebook page, expressing her commitment to fairness and accountability in ultrarunning. She acknowledged the challenges of speaking up about rules and technicalities, noting that it can lead to retaliation.

Herron emphasized that the International Association of Ultrarunners (IAU) has validated her concerns twice, confirming that she continues to hold the IAU World Records and World Bests for 48 Hours and 6 Days. She concluded by thanking her supporters and reaffirming her dedication to integrity in the sport.

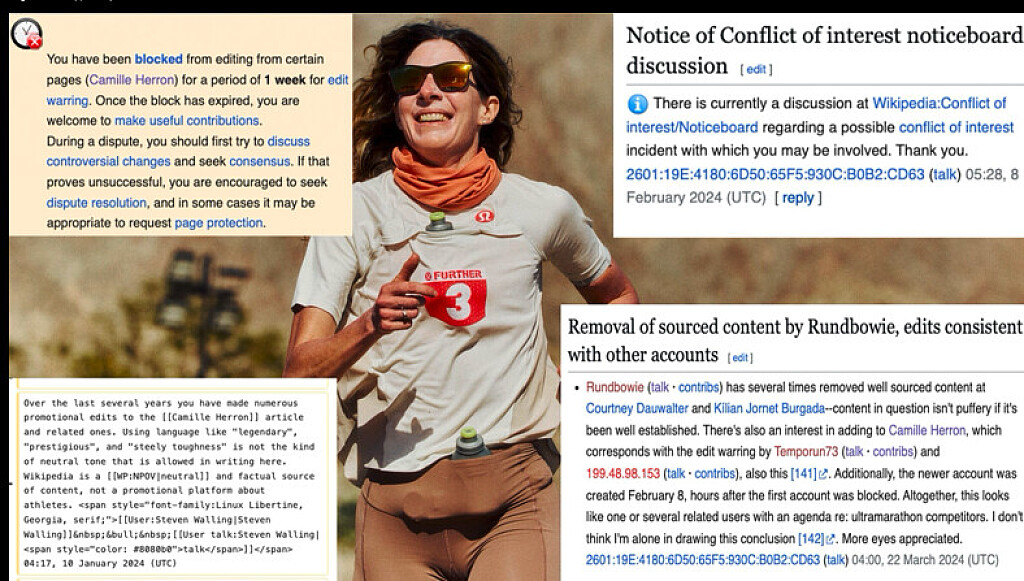

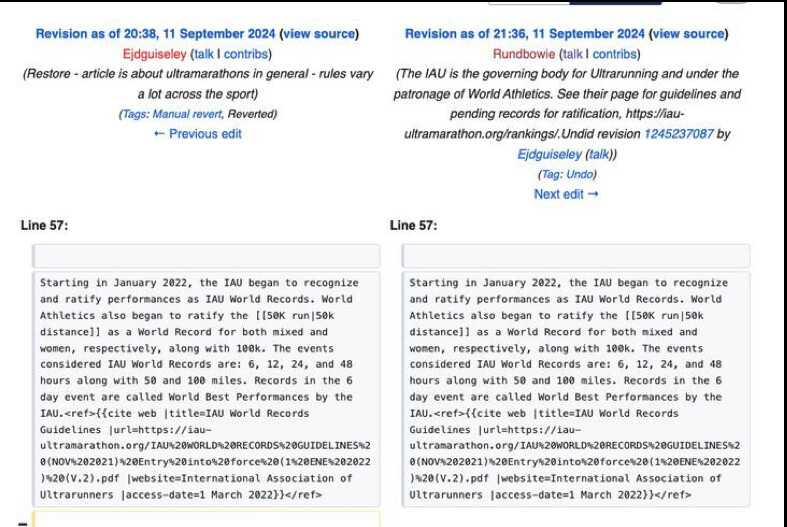

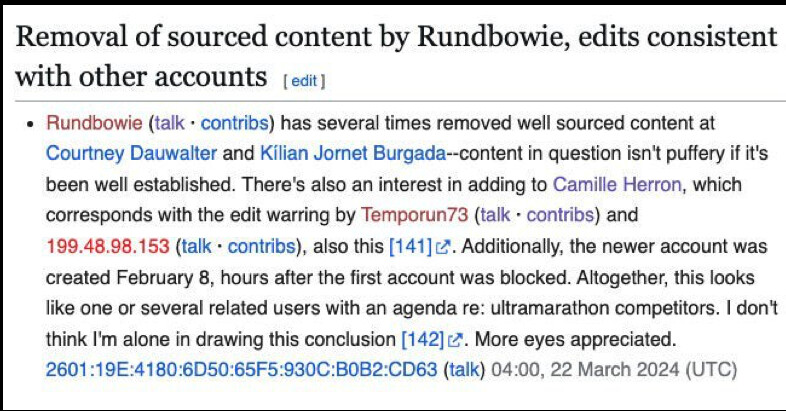

In September 2024, the ultrarunning community was shaken by a controversy involving American ultrarunner Camille Herron and her husband and coach, Conor Holt. The couple was accused of editing Wikipedia pages to enhance Herron's achievements while diminishing those of her competitors.

An investigation by Canadian Running revealed that two Wikipedia accounts, "Temporun73" and "Rundbowie," were linked to Herron's email and Holt's IP address. These accounts made numerous edits to Herron's page, amplifying her accomplishments, and altered the pages of fellow ultrarunners, including Courtney Dauwalter and Kilian Jornet, to downplay their achievements. For instance, statements like "widely regarded as one of the best trail runners ever" were removed from competitors' pages, while Herron was described as "widely regarded as one of the greatest ultramarathon runners of all time."

Following the exposure of these activities, Herron's primary sponsor, Lululemon, terminated their partnership with her. In a statement, the company emphasized its commitment to equitable competition and stated, "After careful consideration and conversation, we have decided to end our ambassador partnership with Camille."

In response to the allegations, Holt took full responsibility, stating, "Camille had nothing to do with this. I'm 100 percent responsible and apologize [to] any athletes affected by this and the wrong I did." He explained that his actions were an attempt to protect Herron from online harassment and bullying that had adversely affected her mental health.

The incident has sparked widespread discussion within the ultrarunning community, with many expressing disappointment over the unsportsmanlike behavior. Herron, known for her numerous world records and contributions to the sport, now faces challenges in rebuilding trust and credibility within the community.

As the situation unfolds, it serves as a reminder of the importance of integrity and sportsmanship in athletics. The ultrarunning community continues to reflect on the implications of this controversy and the lessons to be learned moving forward.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

How Did Courtney Dauwalter Get So Damn Good?

If Courtney Dauwalter could travel back in time, this is what she would do: She’d join a wagon train crossing the American continent, Oregon Trail-style, for a week, maybe more, just to see if she could swing it. It would be hard, and also pretty smelly, but Dauwalter wonders what type of person she’d be if she deliberately decided to take that journey. Would she stop in the plains and build a farm? Could she make it to the Rocky Mountains? How much suffering could she take, and how daunted might she be by the terrain ahead of her?

“If you get to Denver and this huge mountain range is coming out of the earth, are you the type of person who stops and thinks, ‘This is good’?” she wonders. “Or are you the person who’s like, ‘What’s on the other side?’ ”

Dauwalter is probably (definitely) the best female trail runner in the world—a once-in-a-generation athlete. She’s hard to miss at the sport’s most famous races, and not just because of the nineties-style basketball shorts she prefers. (Her explanation: she just likes them.) It’s because she’s often running among the leading men in the sport, smiling beneath her mirrored sunglasses. The 39-year-old is five foot seven and lean, with smile lines and hair streaked with highlights from abundant time spent in high-altitude sun.

Dauwalter shared her historical daydream with me while sipping a pink sparkling water at her house in Leadville, Colorado, after a four-hour morning training run. Her cross-country wagon musings get at why she’s the best female ultrarunner ever to live: Dauwalter is curious. She’s curious about pain, about limits, about possibility. This quality is fundamental to what makes her so good.

Over the past eight years, Dauwalter has won almost everything she’s entered. In 2016, she set a course record at the Javelina Jundred—an exposed, looped route through the Sonoran Desert of Arizona. That same year she won the Run Rabbit Run 100-miler in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, by a margin of 75 minutes, despite experiencing temporary blindness for the last 12 miles (she could only see a foggy sliver of her own feet). Because of ultrarunning’s huge distances, it’s not unheard of to beat the competition by so much, but it doesn’t happen with the frequency that Dauwalter manages.

In 2018, she won the extremely competitive Western States 100 in California; it was her first time on the course. A year later, she set a new course record while winning the prestigious Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB), besting the second-place finisher by just under an hour. In 2022, she set the fastest known time on the 166.9-mile Collegiate Loop Trail in her backyard in Colorado, and she won (and set a new course record at) the Hardrock 100, a grueling high-altitude loop through the state’s San Juan Mountains.

Dauwalter is also one of the few runners of her caliber to seriously dabble in the really long distance races. In 2017, she won the Moab 240—yes, that’s 240 miles—in two days, nine hours, and fifty-five minutes, ten hours ahead of the second-place finisher. She ran even farther at Big’s Backyard Ultra in 2020, a quirky test of wills where athletes complete a 4.167-mile course every hour on the hour until only one runner is left. Dauwalter set a women’s course record of just over 283 miles.

Given everything she’s accomplished, it’s hard to believe that the past two summers have been her most successful yet. In 2023, she returned to Western States, where she smashed the women’s course record by more than an hour and finished sixth overall. When she passed Jeff Colt, who finished ninth, he remembers how calm and collected she looked, running all alone. “My pacer looked back at me and said, ‘Jeff, I can’t even keep up with her right now,’ ” he says. Less than three weeks later, she won Hardrock again, taking fourth place overall and setting a new women’s course record. The race changes direction on the looped course each year, and she now holds both the clockwise and counterclockwise records.

In the interest of testing herself one more time, in late August she traveled to France to run UTMB again. She won that race too, becoming the first person in history to win all three races in a single summer. “She’s one of those humans who defy even the concept of an outlier,” says Clare Gallagher, a former Western States winner who has raced against Dauwalter. “I look at her summer and I have no words. It’s truly hard to conceptualize.”

Dauwalter led UTMB from the start, and she finished more than an hour ahead of the woman in second place. As she descended the final stretch of trail, she was followed by a barrage of cameras and a handful of people who looked like they just wanted a bit of her magic to rub off on them. As crowds roared on either side of the finish line in Chamonix, she looked back at the spectators and clapped in their direction, never raising her hands above her head or pumping her fists in the air. After hugging her parents and her husband, 39-year-old Kevin Schmidt, she jogged back in the direction she’d just come to high-five hundreds of fans.

Dauwalter grew up in the suburbs of Minneapolis, in a tight-knit family that was always active. The kids all played soccer, and when they weren’t at practice they were busy building tree forts or making up games at the local park. In seventh grade, she started running cross-country, and in eighth grade she joined the nordic ski team. She claims to have spent the first years just trying to stay upright, but in high school she went on to be a four-time state nordic ski champion and attended the University of Denver on a cross-country-skiing scholarship. She says that her parents, who now frequently crew and support her at races, led by example. “You work hard, you give everything you’ve got, you don’t forget to have fun,” she says.

Minnesota winters are notoriously cold, and she credits her ability to dig deep within herself to the unforgiving conditions. “Growing up there, you just learn to do stuff, regardless of the weather,” she says. She also points to a cross-country coach who taught her to think differently about pain. “He laid the groundwork for understanding that our bodies are capable of so much,” she says. “We can push past those initial signals saying that’s all I have and turn the knob, and there’s always one more gear.”

After college, Dauwalter taught middle and high school science in Denver, which is where she met Schmidt. “A woman I worked with and a guy he worked with were married, and they just kept putting us in the same places,” she says. “I didn’t know they were meddling!” Schmidt, who works as a software engineer, is also a competitive runner. He and Dauwalter train together—sometimes he’ll join in for her second run of the day—and they trade off supporting each other during races. When I met up with them in Leadville, Dauwalter had just finished crewing for Schmidt at a 100-miler in Switzerland. During her races, he maps her splits, takes care of her aid-station needs, and serves as crew captain. He’s the “spreadsheet brain” to her “tie-dye brain,” as he puts it, and he provides emotional support too.

“Its clear to me when she has taken up residence in the pain cave, so I try my best to fill it with snacks and encouragement,” says Schmidt. One time, while driving to an aid station during a race, Schmidt got a flat tire while carrying everything Dauwalter needed for the night. He wound up sprinting the final three miles to catch her in time.

When Dauwalter started racing more competitively and winning, she and Schmidt had a series of discussions about what they wanted their lives to look like. Ultimately, they decided that she should try to give professional running a shot. In 2017, without a sponsor and with a lot of unknowns still ahead, she left teaching to run full-time. “What we wanted was to look back when we were 90 years old and not wonder what if? about anything,” she says.

Mike Ambrose, the former team manager at Salomon, offered Dauwalter her first sponsorship as a trail runner that same year. She was still new on the scene, but Ambrose could see that she was driven, and the talent was there. “She’s super curious about pushing herself,” he says. “She had this huge engine coming from nordic skiing, and her 24-hour time was really crazy. I thought, well, if she just figures it out and gets more trail experience, she obviously has the mental and physical capacity.”

Despite her nearly superhuman athleticism and mental fortitude, Dauwalter is also very normal. She likes nachos, candy, and beer. She watches sports (the Vikings are her NFL team, even though she’s been in Broncos territory for years), and she wants to spend time with the people she loves, including her parents, and the friends who often crew for her.

Ultrarunning frequently sees short-lived stars, runners who dominate for a couple of years before burning out or slowing down, either from overtraining or simply from the passage of time and the wear on their bodies. Dauwalter, however, seems to have a rare capacity to push against her own limits without tipping over the edge. She’s been running long distances at an elite level for seven years now. Gallagher wonders how she’s managed to avoid injury, given Dauwalter’s volume of physically demanding races.

Login to leave a comment

The Distance Running Scene in 2024: A Year of Remarkable Achievements

The global distance running scene in 2024 was marked by incredible performances, new records, and innovative approaches to training and competition. From marathons in bustling city streets to ultramarathons through rugged terrains, the year showcased the resilience, determination, and evolution of athletes from all corners of the globe.

The World Marathon Majors—Tokyo, Boston, London, Berlin, Chicago, and New York—continued to be the centerpiece of elite distance running, each event contributing to a year of unprecedented performances and milestones.

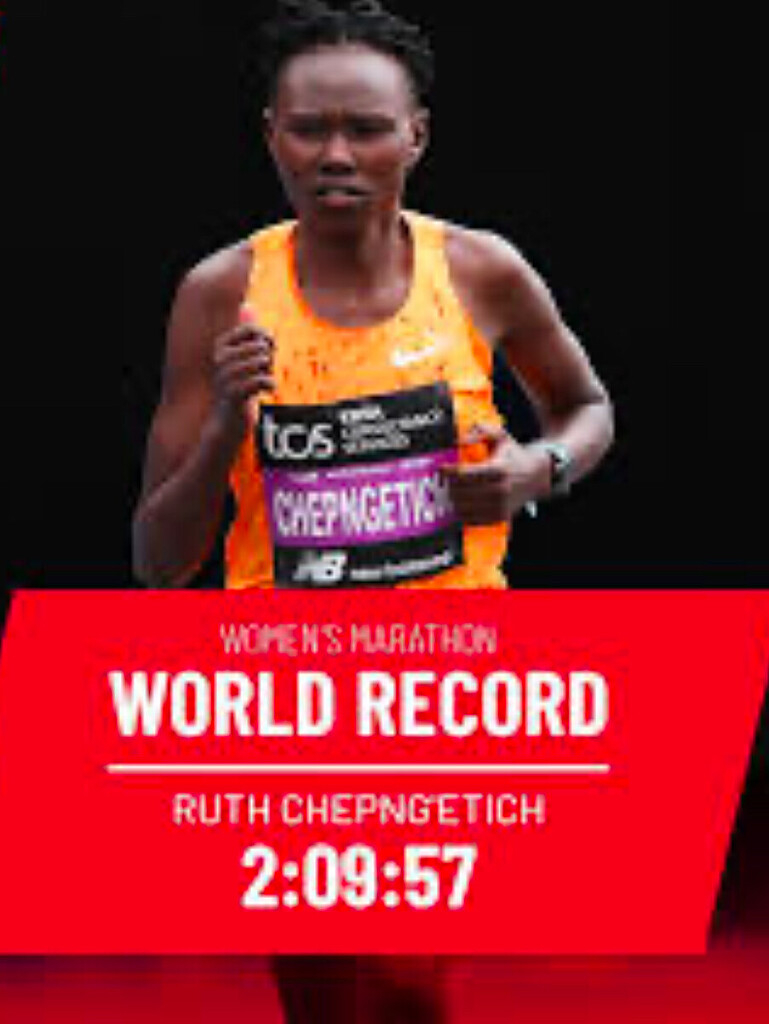

Tokyo Marathon witnessed a remarkable performance by Kenya's Ruth Chepngetich, who set a new women's marathon world record with a time of 2:11:24. This achievement sparked discussions about the rapid advancements in women's long-distance running and the influence of technology in the sport.

In the Boston Marathon, Ethiopia's Amane Beriso delivered a dominant performance, winning in 2:18:01. On the men's side, Kenya's Evans Chebet defended his title, highlighting Boston's reputation for tactical racing over sheer speed.

London Marathon saw Ethiopia's Tamirat Tola take the men's crown, besting the field with a strong tactical race. Eliud Kipchoge, despite high expectations, did not claim victory, signaling the growing competitiveness at the top of men’s marathoning. On the women's side, Kenya's Peres Jepchirchir triumphed, adding another major victory to her impressive resume.

The Berlin Marathon in 2024 showcased yet another extraordinary performance on its fast course, though it was Kelvin Kiptum’s world record from the 2023 Chicago Marathon (2:00:35) that remained untouched. In 2024, Berlin hosted strong fields but no records, leaving Kiptum’s achievement as the defining benchmark for men’s marathoning.

The Chicago Marathon was the highlight of the year, where Kenya's Ruth Chepngetich made history by becoming the first woman to run a marathon in under 2:10. She shattered the previous world record by nearly two minutes, finishing in 2:09:56. This groundbreaking achievement redefined the possibilities in women's distance running and underscored the remarkable progress in 2024.

The New York City Marathon showcased the depth of talent in American distance running, with emerging athletes achieving podium finishes and signaling a resurgence on the global stage.

Each marathon in 2024 was marked by extraordinary performances, with athletes pushing the boundaries of human endurance and setting new benchmarks in the sport.

Olympic Preparations: Paris 2024 Looms Large

With the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris just around the corner, many athletes used the year to fine-tune their preparations. Qualifying events across the globe witnessed fierce competition as runners vied for spots on their national teams.

Countries like Kenya, Ethiopia, Japan, and the United States showcased their depth, with surprising performances by athletes who emerged as dark horses. Japan’s marathon team, bolstered by its rigorous national selection process, entered the Olympic year as a force to be reckoned with, particularly in the men's race.

Ultramarathons: The Rise of the 100-Mile Phenomenon

The ultramarathon scene continued to grow in popularity, with races like the Western States 100, UTMB (Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc), and Leadville 100 drawing record participation and attention.

Courtney Dauwalter, already a legend in the sport, extended her dominance with wins at both UTMB and the Western States 100, solidifying her reputation as the GOAT (Greatest of All Time) in ultrarunning.

On the men’s side, Spain’s Kilian Jornet returned to form after an injury-plagued 2023, capturing his fifth UTMB title. His performance was a masterclass in pacing and strategy, showcasing why he remains a fan favorite.

Notably, ultramarathons saw increased participation from younger runners and athletes transitioning from shorter distances. This shift signaled a growing interest in endurance challenges beyond the marathon.

Track and Road Records: Pushing the Limits

The year 2024 witnessed groundbreaking performances on both track and road, with athletes shattering previous records and setting new benchmarks in distance running.

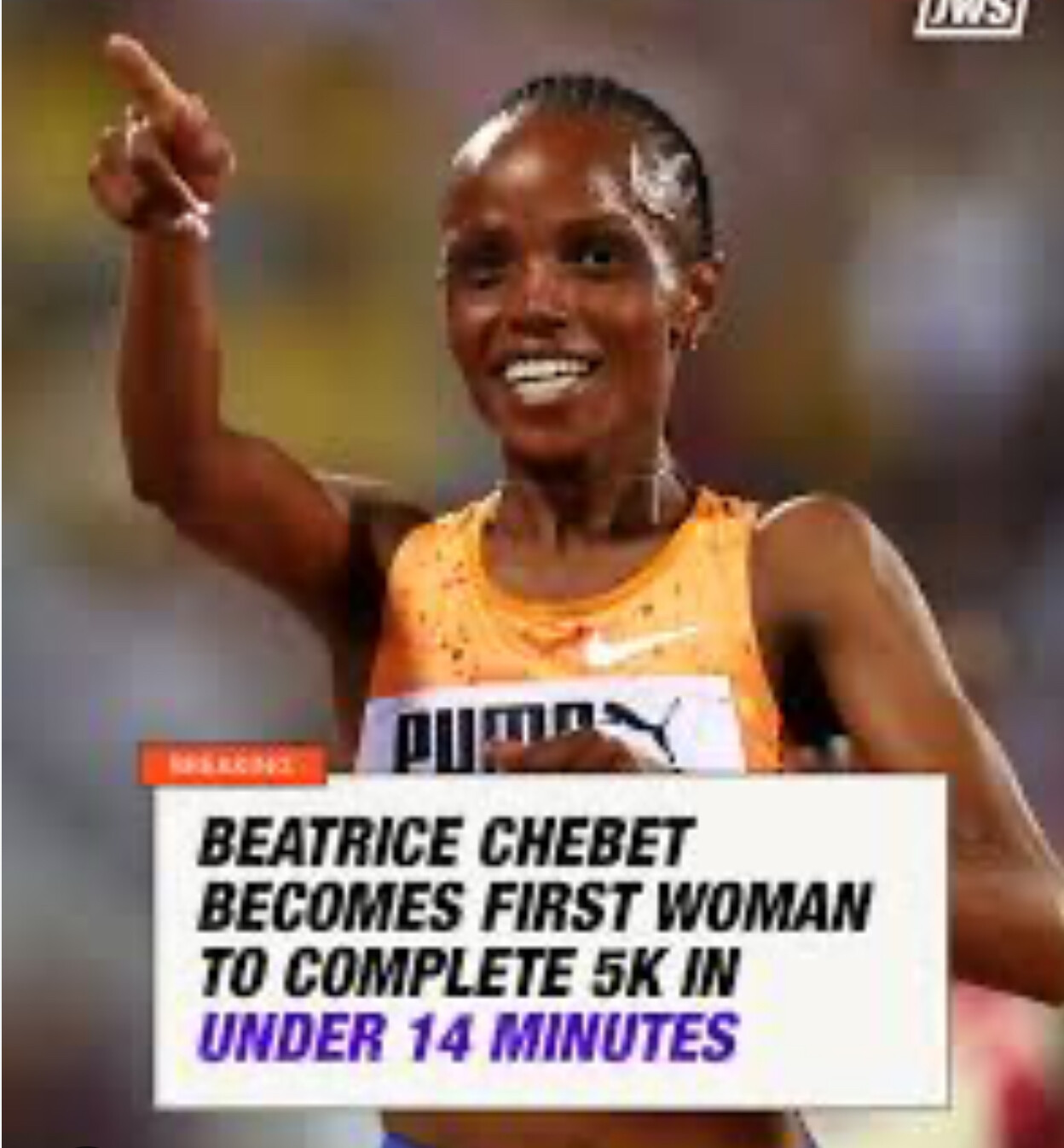

Beatrice Chebet's Dominance: Kenya's Beatrice Chebet had an exceptional year, marked by multiple world records and championship titles.

10,000m World Record: In May, at the Prefontaine Classic, Chebet broke the women's 10,000m world record, becoming the first woman to run the distance in under 29 minutes, finishing in 28:54.14.

Olympic Triumphs: At the Paris Olympics, Chebet secured gold in both the 5,000m and 10,000m events, showcasing her versatility and dominance across distances.

5km World Record: Capping off her stellar year, on December 31, 2024, Chebet set a new women's 5km world record at the Cursa dels Nassos race in Barcelona, finishing in 13:54. This achievement made her the first woman to complete the 5km distance in under 14 minutes, breaking her previous record by 19 seconds.

Faith Kipyegon's Excellence: Kenya's Faith Kipyegon continued her dominance in middle-distance running by breaking the world records in the 1500m and mile events, further cementing her legacy as one of the greatest athletes in history.

Joshua Cheptegei's 10,000m World Record: Uganda's Joshua Cheptegei reclaimed the men's 10,000m world record with a blistering time of 26:09.32, a testament to his relentless pursuit of excellence.

Half Marathon Records: The half marathon saw an explosion of fast times, with Ethiopia’s Yomif Kejelchabreaking the men's world record, running 57:29 in Valencia. The women's record also fell, with Kenya’s Letesenbet Gidey clocking 1:02:35 in Copenhagen.

These achievements highlight the relentless pursuit of excellence by distance runners worldwide, continually pushing the boundaries of human performance.

The Role of Technology and Science

The impact of technology and sports science on distance running cannot be overstated in 2024. Advances in carbon-plated shoes, fueling strategies, and recovery protocols have continued to push the boundaries of human performance.

The debate over the fairness of super shoes reached new heights, with critics arguing that they provide an unfair advantage. However, proponents emphasized that such innovations are part of the natural evolution of sports equipment.

Data analytics and personalized training plans became the norm for elite runners. Wearable technology, including advanced GPS watches and heart rate monitors, allowed athletes and coaches to fine-tune training like never before.

Grassroots Running and Mass Participation

While elite performances stole the headlines, 2024 was also a banner year for grassroots running and mass participation events. After years of pandemic disruptions, global races saw record numbers of recreational runners.

Events like the Great North Run in the UK and the Marine Corps Marathon in the U.S. celebrated inclusivity, with participants from diverse backgrounds and abilities.

The popularity of running as a mental health outlet and community-building activity grew. Initiatives like parkrunand local running clubs played a pivotal role in introducing more people to the sport.

Diversity and Representation

Diversity and representation became central themes in distance running in 2024. Efforts to make the sport more inclusive saw tangible results:

More women and runners from underrepresented communities participated in major events. Notably, the Abbott World Marathon Majors launched a program to support female marathoners from emerging nations.

Trail and ultrarunning communities embraced initiatives to make races more accessible to runners from diverse cultural and economic backgrounds.

Challenges and Controversies

Despite the many successes, 2024 was not without its challenges:

Doping Scandals: A few high-profile doping cases marred the sport, reigniting calls for stricter testing protocols and greater transparency.

Climate Change: Extreme weather conditions impacted several races, including the Boston Marathon, which experienced unusually warm temperatures. Organizers are increasingly focusing on sustainability and adapting to climate-related challenges.

Looking Ahead to 2025

As the year closes, the focus shifts to 2025, which promises to build on the momentum of 2024. Key storylines include:

The quest for a sub-2-hour marathon in a record-eligible race, with Kelvin Kiptum and Eliud Kipchoge at the forefront.

The continued growth of ultrarunning, with new records likely to fall as more athletes take up the challenge.

The evolution of distance running as a global sport, with greater inclusivity and innovation shaping its future.

Conclusion

The distance running scene in 2024 was a celebration of human potential, resilience, and the unyielding pursuit of greatness. From record-breaking marathons to grueling ultramarathons, the year reminded us of the universal appeal of running. As the sport evolves, it continues to inspire millions worldwide, proving that the spirit of running transcends borders, ages, and abilities.

by Boris

Login to leave a comment

The Strange Saga of Ultrarunner Camille Herron and Wikipedia

The husband of runner Camille Herron admitted to having altered the Wikipedia biographies of prominent ultrarunners. The revelation came after a Canadian journalist launched an investigation.

On September 24, Conor Holt, the husband and coach of American ultrarunner Camille Herron, admitted to altering the biographies of Herron, Courtney Dauwalter, Kilian Jornet, and other prominent runners on the website Wikipedia. Holt’s edits boosted his wife’s accolades but also downgraded those of the other prominent ultrarunners.

“Camille had nothing to do with this,” Holt wrote in an email sent to Outside and several running media websites. “I’m 100 percent responsible and apologize [to] any athletes affected by this and the wrong I did.”

The confession brought some clarity to an Internet mystery that embroiled the running community for several days and sparked a flurry of chatter on social media and running forums. Herron, 42, is one of the most visible ultrarunners in the sport, and over the years she has won South Africa’s Comrades Marathon and also held world records in several different events, including the 48-hour and six-day durations. But the Wikipedia controversy led to swift consequences for Herron—her major sponsor, Lululemon, parted ways with her on Thursday morning.

The entire ordeal sprung from an investigation led by a Canadian journalist who spent more than a week following digital breadcrumbs on dark corners of

Marley Dickinson, a reporter for the website Canadian Running, began looking into the Wikipedia controversy in mid-September after receiving a tip from someone in the running community. The tipster told Dickinson, 29, that someone was attempting to delete important data from the Wikipedia entry for “Ultramarathon.”

The person had erased the accomplishments of a Danish runner named Stine Rex, who in 2024 broke two long-distance running records—the six-day and 48-hour marks—which were previously held by Herron. At the time, the sport’s governing body, the International Association of Ultrarunners, was deciding whether or not to honor Rex’s six-day record of 567 miles.

“The person making the edits said the IAU had made a decision on the record, even though they hadn’t yet,” Dickinson told me. “Whoever was doing it really wanted to get Rex’s run off of Wikipedia.”

Wikipedia allows anonymous users to edit entries, but it logs these changes in a public forum and shows which user accounts made them. After an edit is made, a team of volunteer moderators, known as Wikipedians, examines the changes and then decides whether or not to publish them. The site requires content to be verifiable through published and reliable sources, and it asks that information be presented in a neutral manner, without opinion or bias. The site can warn or even suspend a user for making edits that do not adhere to these standards.

Dickinson, who worked in database marketing at Thomson Reuters before joining Canadian Running, was intrigued by the bizarre edits. “I’ve always been into looking at the backend of websites,” he told me. “There’s usually a way you can tie an account back to a person.”

The editor in question used the name “Rundbowie,” and Dickinson saw that the account had also made numerous changes to Herron’s biography. Most of these edits were to insert glowing comments into the text. “I thought whoever this person is, they are a big fan of Camille Herron,” Dickinson said.

Rundbowie was prolific on Wikipedia, and made frequent tweaks and updates to other biographies. The account had removed language from the pages of Jornet and Dauwalter—specifically deleting the text “widely regarded as one of the greatest ultramarathon runners of all time.” Rundbowie had then attempted to add this exact language to Herron’s page. Both attempts were eventually denied by Wikipedians.

After examining the edits, Dickinson began to suspect that Rundbowie was operated by either Herron or Holt. Further digital sleuthing bolstered this opinion. He saw that the Rundbowie account, which made almost daily edits between February and April, abruptly went silent between March 6-12. Those dates corresponded with Herron’s world-record run in a six-day race put on by Lululemon in California.

But Dickinson wasn’t done with his detective work. He saw that in March, Wikipedia had warned Rundbowie on its public Incident Report page. The reason

A final Internet deep dive convinced Dickinson that he was on the right track. The IP address—a string of characters associated with a given computer—placed Temporun73 in Oklahoma, which is where Herron and Holt live. Then, on a forum page for Oregon State University, which is where Herron attended graduate school, Dickinson found an old Yahoo email address used by Herron. The email name: Temporun73.

“To me, this was a clear sign that it was either Conor or Camille” Dickinson said.

Dickinson published his story to Canadian Running on Monday, September 23. The piece included screenshots of Wikipedia edits as well as Dickinson’s trail to Herron and Holt. It started off a flurry of online reactions.

A thread on the running forum LetsRun generated 360 comments, and several hundred more appeared on the Reddit communities for trail running and ultrarunning. Film My Run, a British YouTube site, uploaded an immediate reaction video the following day. Within 12 hours, more than a hundred people shared their thoughts in the comments section.

It’s understandable why. Lauded for her accolades in ultra-distance races, Herron is also one of the most visible ultrarunners on the planet. She gives frequent interviews, and has been an outspoken advocate for the anti-doping movement, for smart and responsible training habits, and for the advancement of women runners.

“I think we’re going to continue to see barriers being broken and bars raised. I want to see how close I can get to the men’s world records, or even exceed a men’s world record,” she told Outside Run in 2023.

Herron has also spoken and written about her own mental health. Earlier this year, she began writing and giving interviews about her recent diagnosis with Autism and ADHD.

“Although I knew little about autism before seeking out a diagnosis, my husband, who observed my daily quirks and often reminded me to eat, drink, and go to bed, would jokingly speculate that I might be autistic,” she told writer Sandra Rose Salathe on the website FloSpace in July.

Dickinson told me he had a very positive image of Herron from his short time at Canadian Running. He joined the website in 2021.

“She’s always been super nice and welcoming,” Dickinson said.

Dickinson says he reached out to Herron and Holt via email and social media, but did not receive a reply. On Monday afternoon, a user on the social media platform X asked Herron about the story. “It’s made up,” Herron’s account replied. “Someone has an ax to grind and is bullying and harassing me.”

Herron’s social media accounts were deactivated shortly afterward—Holt later said he took them down.

Some online commenters questioned if the story was legitimate—something I did too, initially. Following Dickinson’s arcane trail through Wikipedia’s backend required a careful read, and a strong knowledge of the encyclopedia’s rules and regulations.

After speaking to Dickinson, I sent my notes to a Wikipedia expert named Rhiannon Ruff, who operates a digital consulting firm called Lumino that helps clients navigate the online encyclopedia. Ruff examined the story as well as the Wikipedia histories of Rundbowie and Temporun 73, and said that the evidence strongly suggested that both accounts were operated by the same person. But, since Wikipedia allows for anonymity, you cannot make the connection with 100 percent certainty.

Ruff pointed out that Wikipedia’s internal editors strongly believed the two accounts had a biased with Herron, because the accounts had attempted to write in the same sentence. “Both tried to add details about her crediting the influence of her father and grandfather, and how she runs with a smile,” Ruff said.

Ruff also pointed me to the prolific editing history of Temporun73. Started in 2016, the account had made approximately 250 edits to

“I never got a chance to say anything to the Canadian Running website before they published it,” Holt wrote.

Holt admitted that he was the operator of the Temporun73 and Rundbowie accounts. But he said his Wikipedia editing was aimed at combating online bullies who had removed biographical details from Herron’s Wikipedia page in the past.

“I kept adding back in the details, and then they blocked my account in early February of this year,” Holt wrote. “Nothing was out of line with what other athletes have on their pages. Wikipedia allows the creation of another account, so I created a new account Rundbowie. I was going off what other athletes had on their pages using the username Rundbowie and copying/pasting this info.”

“I was only trying to protect Camille from the constant bullying, harassment and accusations she has endured in her running career, which has severely impacted her mental health,” he added. “So much to the point that she has sought professional mental health help.”

Outside asked Holt via email to provide further details, but we did not receive a response. In an email to Canadian Running, Holt said he was focused on Herron’s upcoming race, and would not be conducting interviews.

But the fallout from the admission came quickly. On Thursday morning Dickinson broke more news: apparel brand Lululemon, which has backed Herron since 2023, had ended its partnership. In a statement provided to several outlets, the brand said it was dedicated “to equitable competition in sport for all,” and that it sought

by Outside Online

Login to leave a comment

How to Prepare For Your First Running Event

Are you signed up for your first running race this year? If so, you might be wondering what to do next. Many of us register for a 10k or half marathon in the hopes that doing so will simply motivate (or pressure) us to get to the finish line, and sometimes, it does. But let’s face it, Forrest Gump was just a movie. In real life, without proper preparation, you could wind up injured, unable to finish, or not even make it to the starting blocks, all of which would be really disappointing, to say the least.

Preparing for your first race requires careful planning, from training and getting the right kit to goal-setting and pre-race fuelling. Proper preparation ensures you’re physically ready for the race, have the energy to keep going and can overcome race day nerves, all of which will mean you have a more enjoyable race, and are likely to make it the first of many.

1. Set a goal

Once you’ve chosen a race and signed up, it can be smart to set an achievable goal. This can give you something to focus on during both your training and your race, and that can help you stay motivated, while achieving your goal can also give you a greater sense of satisfaction (for this reason, it’s a good idea to set a secondary goal in case you don’t make your primary goal.

Your goal could be something ambitious, like running a sub three-hour marathon, but it can easily be as simple as just finishing the race. When I did my first triathlon in 2012, I simply wanted to finish and I wanted to do so without walking during any of the running section. I didn’t finish anywhere near the podium, but I managed to achieve my goals and I was really happy with myself.

2. Make a training plan

For injury prevention, it’s obviously vital to make a smart training plan, and to leave yourself enough time before race day to actually execute it. There is no one way to train, and your plan will depend on where you’re starting and where you want to get to, but just as a rough idea, in our first marathon training plan we recommend 12 weeks for seasoned runners, but a full year for novices.

The most important aspect of training to remember is to build up gradually to give your body time to adapt to each increase in load, make ample room for rest and recovery and if possible, work with a coach and train in conditions similar to those you’ll be racing in.

3. Gear up

As you get closer to the big day, you’ll need to start to consider your gear. You’ll need to choose trail running shoes or road running shoes and have trained in them for a while to be sure they’re right for you. If you’ve already put in a ton of miles of them, you may need to replace them with an identical pair a few weeks before the race, and break them in. Once you’ve found the perfect pair of running socks, have a new or nearly new pair set aside for race day.

Use your training months to figure out what clothing you’re most comfortable in, taking into account the expected climate and conditions. Are you happiest in a pair of running shorts or do you prefer running tights? You’ll need a well-fitting running top that’s breathable and doesn’t chafe, and consider whether you want to run with a headband or running hat if you're expecting sunny conditions.

Remember, the general rule for running is light, breathable clothing that wicks moisture, but everyone is different. Reigning UTMB champ Courtney Dauwalter is well-known for running in baggy men’s running shorts and shorts, which isn’t common, but it definitely works for her.

4. Rest up

You’ll spend months slowly ramping up your mileage in order to reach your race distance, but once you get there, you’ll want to start to reduce both your distance and intensity in the final couple of weeks before your race, a practice known as tapering. During this time, you’ll focus on easy runs.

In the final two days before your race, get complete rest and lots of sleep. If you’re not a great sleeper, read our article getting better sleep for some tips on improving your sleep hygiene and routine.

5. Recce your route

Ultra runner Renee McGregor has ranked highly in some pretty rugged races, from Snowdonia to the Himalayas, and when I heard her talk about her accomplishments, she described making the podium in a gnarly race where the majority of participants took a wrong turn. Her advantage? She wasn’t necessarily the fastest runner, but she had checked out the race course ahead of time and knew where to go.

Understanding your route before you take off, if possible, can help you plan for when you’re going to want to slow down, or walk, where you can gain back some time, when and if you’ll need running poles and any tricky sections in a trail race where there’s the possibility of getting off-route.

6. Get in the right headspace

In addition to your physical training, it’s advisable to give your mental state some attention. Running a race can be exhilarating and empowering but it can also be nerve wracking and daunting. In the months leading up to your race, it can be worthwhile practicing mindfulness or meditation, which a 2020 study published in the journal Neural Plasticity found improved coordination, endurance and cognitive function. This could help you in the lead up to the race and in combating race-day nerves.

Know yourself and understand what you’ll need the day before your race and morning of to ensure you’re in the best head space possible. It might be good to minimize social contact and give yourself some quiet time to focus and get in the right headspace.

7. Fuel up

Just like filling up the tank of your car before you set off on a long drive, you’re going to want to make sure your body has plenty of energy stored before a race. For a race that’s not likely to take much more than an hour, you can simply make sure you eat well in the couple of preceding days, but fueling for endurance races can take careful fine-tuning. Following his second-place win at the 2023 UTMB, Zach Miller revealed that for him, managing his sodium levels with salt tablets was the secret to success.

For longer distances, you might want to consider increasing your carbohydrate intake – a practice known as carb loading – to increase your body’s glycogen stores. The best nutritional advice is to focus on well-balanced meals with protein and carbohydrates and not going overboard on refined carbs or fiber, which might wreak havoc on your gut. Learn more in our article on carb loading.

Though you should definitely eat well in the days leading up to your race, if you’re going to be able to eat during the race and are loading your hydration vest up with running gels, then you don’t necessarily need to carb load, but you will want to make sure your stomach can handle gels and take them with plenty of water to avoid the dreaded “runners' trots.”

Ultimately, for longer endurance races, working with a dietician will give you an advantage, since every athlete and every race is different. This will help you avoid the pitfalls of low energy availability and might help you figure out your unique nutritional needs faster.

8. Pre-hydrate

As we explain in our article on hydration tips for runners, hydration for a race doesn’t begin with filling up your hydration pack. Your behavior in the days before a long run can really affect your hydration levels on the big day, so avoid dehydrating foods like caffeine and alcohol.

According to Susan Kitchen, registered dietitian and USA Triathlon Level II and IRONMAN certified endurance coach, if you’re training for a big race, you want to avoid being in the heat unnecessarily in the days leading up to it, unless you're just doing a training run, but sitting outside on the beach sweating, or in a sauna, is not a good idea. Sip plenty of water in the days before your race, too.

9. Make a recovery plan

Chances are, all of your energy and efforts will be focused on that finish line, but the longer the race, the more you’ll want to make a recovery plan, otherwise it’s all too easy to end up having too many celebratory beers, which after a long run can be a bad idea.

Try to plan for at least a couple of days off work following your race to recuperate, hydrate and nourish your body, schedule a massage and engage in some of your favorite recovery activities to reward your body for all its hard work.

10. Set your alarm

The night before race day, make sure you set your alarm nice and early so you have plenty of time to prepare. Chiefly, you’ll want to have time to sip water, eat and give yourself enough digestion time before the starting gun goes.

In our article on what to eat before a half marathon, we explain that nutrition experts recommend runners eat a familiar breakfast around three to four hours before the race start, or a large snack 90 minutes to two hours beforehand. When deciding what time to get up, factor in that meal as well as how much time you need to get to the race plus any other pre-race rituals you want to observe.

by Julia Clarke

Login to leave a comment

American Katie Schide Shatters Courtney Dauwalter’s Course Record to Win UTMB

She’s now the third woman to win both Western States and UTMB in the same year.

Katie Schide is on a tear.

On Saturday, the American won the women’s race at the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB) in dominant fashion, finishing the 109-mile race in 22 hours, 9 minutes, and 31 seconds. Her time is 21 minutes faster than Courtney Dauwalter’s course record of 22:30:54 from 2021.

Schide, 32, is undefeated this year, winning the Canyons 100K in April and the prestigious Western States 100 in June.

Ruth Croft of New Zealand was 39 minutes behind Schide in second place (22:48:37). She passed Canada’s Marianne Hogan—who would finish third in 23:11:15—just after the 100-mile mark. Dauwalter, who won the Hardrock 100 on July 12, did not compete in this year’s edition.

In the men’s race, Vincent Bouillard of France was not favored to win, but he ultimately took the crown. He went to the lead after 48 miles and never relinquished it, crossing the finish line in Chamonix in 19:54:23. His compatriot, Baptiste Chassagne, was next to finish in 20:22:45, while Ecuador’s Joaquin Lopez placed third (20:26:22).

Last year’s champion, Jim Walmsley of the U.S., withdrew just after 50 miles because of a knee issue, according to a post on his Instagram story. He remains the only American man to win the race.

UTMB has been contested since 2003. The course—which slightly changes year-to-year—starts and ends in the French Alpine town of Chamonix and traverses through Italy and Switzerland along the way, covering over 30,000 feet of elevation gain.

This is Schide’s second time winning the event after taking top honors in 2022. Originally from Maine, Schide now trains in France and is sponsored by The North Face.

In the final 7 kilometers, a downhill section, she was over 20 minutes ahead of course record pace, but she started limping. The buffer, however, was enough, and by the end, the hitch in her stride had mostly dissipated.

Schide said in a post race interview on the UTMB broadcast that her main goal was to dip under the 22-hour barrier, followed by a secondary goal breaking Dauwalter’s time from 2021. Schide went out hard in the first half—like she did in 2022—but she said winning two years ago gave her some much-needed context.

“I think this race, I just went in more confident in myself and I wasn’t surprised that I was fast,” she said. “Whereas in 2022, I was kind of freaking out because I was like “Oh, I didn’t really mean to do that.’ But this time, I meant to do it, and I was just focused on trying not to die too hard at the end.”

Schide now joins Dauwalter (2023) and Nikki Kimball (2007) as the third woman to win both Western States and UTMB in the same year.

Login to leave a comment

UTMB Is Having a Golden Moment. But It’s Delicate.

After a year that included a maelstrom of controversy, the world’s most prominent ultra-trail running event has righted its path

“It felt like a golden era of trail running.”

That quote came from Keith Byrne, a senior manager at The North Face and a UTMB live stream commentator for nearly a decade, who was talking about last summer’s UTMB World Series Finals in Chamonix, France.

The UTMB races during the last week of August last summer were, I thought, the most alluring in the event’s 20-year history.

After years of being frustrated by the course, American Jim Walmsley finally put it all together for a victorious lap around Mont Blanc. In doing so he became the first U.S. man to win the race, setting a course record of 19:37:43. He and his wife, Jess, had moved from Arizona to live full-time in France to make it happen. And then there was Colorado’s Courtney Dauwalter, who won the race handily in 23:29:14 to notch her third victory and continue the strong legacy of American women on the course. The win felt extra historic because it made her the first person to win Western States, Hardrock, and UTMB in the same year—arguably the three most legendary and competitive 100-mile events in the world, and she dominated each one.

The events came off without a hitch and included record crowds in Chamonix, plus a record 52 million more tuning into the livestream.

Throughout the fall and winter, harmony and happiness seemed to give way to chaos and discontent. But a year later, as the UTMB Mont Blanc weeklong festival of trail running kicks off on August 26, everything seems back to normal in Chamonix. What happened along the way is a tale of drama, perhaps both necessary and unnecessary, all of it culminating in course corrections by the multinational race series.

In short, what a year it has been for UTMB.

And now, hordes of nervous and excited runners from all corners of the globe are descending on Chamonix for this year’s UTMB Mont-Blanc races. Registration for UTMB World Series events is reportedly up about 35 percent year over year with even greater growth in interest for OCC, CCC and UTMB race lottery applications. There is more media coverage, more pre-race hype, and more excitement than ever before. More running brands are using the UTMB Mont Blanc week to showcase their new running gear with media events, brand activations, and fun runs. Even The Speed Project—although entirely unrelated to UTMB—chose Chamonix as the starting point of its latest so-called underground point-to-point relay race to try to catch some of the considerable buzz UTMB is generating.

So what happened? Did the UTMB organization do its due diligence and make amends with several significant changes in the spring? Was the angst and stirring of emotions just not as widely felt as the fervent bouts of Instagram activism claimed it to be? Have the participants and fans of the ultra-trail running world suffered amnesia or become ambivalent? Or is it all a sign of the race—and the entire sport of trail running—going through growing pains as it adjusts to the massive global participation surge, increased professionalism, and heightened sponsorship opportunities?

On the eve of another 106-mile lap around the Mont Blanc massif, I wanted to take a look at what happened and the current state of UTMB’s global race series that culminates here in Chamonix this week.

We caught a glimpse of what was to come shortly before UTMB last year, when the race organization announced the European car company Dacia as its new title sponsor. A fossil-fuel powered conglomerate didn’t sit well with some fans of the event, coming amid an era of widespread climate doom (even though the brand would be highlighting its new Spring EV at the UTMB race expo.) The Green Runners, an environmental running community co-founded by British trail running stars Damian Hall and Jasmin Paris, called it an act of “sportswashing” and released a petition calling on UTMB to denounce the partnership. (Hall even traveled all the way to Chamonix to deliver the petition in person.)

These grumblings of discontent and others that followed exploded into a social media firestorm shortly after UTMB. In October, it became public that UTMB had moved to launch a race in British Columbia, Canada, just as a similar event in the same location was struggling with permitting. A he-said, she-said back-and–forth left onlookers with whiplash. Then on December 1, UTMB livestream commentator Corrine Malcolm announced on Instagram that she had been fired and in late January, a leaked email from elite runners Kilian Jornet and Zach Miller to fellow athletes called for a boycott of the race series. All of it, jet fuel for social media algorithms.

“We’re at a turning point in trail running, but we can keep the core values if the community stands up,” the Pro Trail Runners Association secretary, Albert Jorquera, told me at the time.

In the midst of these dramas, I interviewed race founders Catherine and Michel Poletti over lunch at a Chamonix cafe. For nearly a decade now, I have met with the couple for candid conversations that helped frame online articles and magazine stories, and most recently for the book, The Race that Changed Running: The Inside Story of UTMB.

I plunged headlong into two articles with hopes of explaining it all. There was so much heat swirling around the UTMB stories, and so little light.

“The very thing that made ultrarunning so bonding was being torn apart by the community itself through social media,” said Topher Gaylord. A former elite runner who tied for second in the inaugural UTMB in 2003, Gaylord engineered UTMB’s first title sponsorship with The North Face and has been a close supporter of the Polletis for 20 years. “Some players are using social media to divide the community. That’s super disappointing.”

To me, it felt like the aggressive online activists were winning the day. Trail running suddenly seemed polarized, infected with the intertwined social media viruses of false indignation and close-mindedness. Twice, I deep-sixed my article drafts. Friends and editors convinced me they wouldn’t be read dispassionately. Who wants to be handed a fire extinguisher, when your goal is to torch the house?

Well, what a difference eight months can make. We now have some perspective and, with it, some answers.

Since its earliest days, UTMB’s volunteer founding committee believed in the values of the sport. The very first brochure produced for the race—a mere sheet of paper—featured a paragraph on values. In later years that statement became much more comprehensive, expanding to cover a wide range of topics and the race’s mission to support and protect them.

But maintaining those values in an organization that has gone from a singular race with a literal garden-shed office to a 43 global event series with a staff of more than 70 full-time employees is tricky at best. In an interview once, Michel Poletti paused, asking if I had seen a photo of a mutual friend that was making the rounds. He was climbing one of Chamonix’s famed needle-sharp aiguilles, one foot on each side of a razor sharp ridge—a perilous balancing act, big air on each side. It was his metaphor for trying to move ever up, while balancing business growth and heartfelt values.

Over the course of dozens of hours of interviews with the Polettis, I came to learn one thing: UTMB always moves forward up the ridge. In the process, UTMB corrects its course. It starts with a careful analysis after each edition, evaluating pain points in areas such as logistics, security, media, traffic, and others, discussing how they can be addressed. Historically, those course corrections haven’t been at the pace others might want—especially since the social unrest that developed during the Covid pandemic—but the organization has a reliable pattern of steadily addressing concerns.

And so, not too many weeks after that lunch meeting, UTMB set to work. First came a heartfelt effort they kept under the radar—traveling around the U.S. to listen and learn. They spent two weeks in the U.S. in February, visiting with American athletes, race directors, journalists, consultants, and their Ironman partners. “We need to learn from our mistakes and from this crisis,” Michel said.

Methodically over the ensuing months, UTMB rolled out a series of changes. Some were aimed at directly addressing the controversies, others were overdue for what is, by any metric, the world’s premier ultra-trail running event.

“My hope is that the trail running community understands that we are human,” Catherine had told me over the winter.

Four months ago, at the end of April, the race organization announced that Hoka would become the new title sponsor of UTMB Mont-Blanc and the entire UTMB World Series through 2028. It was a huge move because Hoka, one of the biggest running brands in the world, essentially doubled-down on its support of UTMB and trail running in general. The five-year deal brought benefits other than cash, too. Hoka has a strong history of inclusivity and growing representation among marginalized communities, an area UTMB has announced it intends to focus more on beginning this year. The deal also moved Dacia out of the title sponsor limelight, instead bringing a brand with a strong reputation in trail running to the fore.

Dacia was shifted to the role of a premier partner in Europe, and now plays an integral part in a new eco-focused mobility plan UTMB updated in July. Fifty of their cars can be signed out for use by over 70 staff and 2,500 volunteers, encouraging them to arrive in Chamonix using public transportation instead. The move is estimated to eliminate 200 vehicles driving into the valley. (The organization’s new mobility plan will transport an estimated 15,000 runners and supporters, eliminating the need for approximately 6,000 cars during the UTMB Mont-Blanc week. On average, a bus will run every 15 minutes between Chamonix and Courmayeur, Italy, and Chamonix and Orsières, Switzerland.)

In May, UTMB announced a new anti-doping policy it had developed with input from PTRA. The organization committed to spending at least $110,000 per year, money that will be allocated to test all podium finishers and a randomized selection of the 687 elite athletes in attendance. The new policies will be implemented by the International Testing Association, an independent nonprofit that has also conducted two free informational webinars for the 1,400 UTMB Mont Blanc elite runners.

Not long after the announcement, Catherine Poletti suggested this was just a start. Speaking at TrailCon, a new conference held in Olympic Valley, California, on June 26, she said, “It’s a first big step for us. And we’ll continue to develop this policy.” (The most important anti-doping protocol may still be beyond UTMB, however. “The elephant in the room is that we need a coordinated approach to establish out-of-competition testing,” Tim Tollefson, an elite U.S. runner and director of the Mammoth TrailFest in California, who spearheaded independent testing at his event in 2023. “Individually, we’re just lighting our money on fire.”)

In mid-June, UTMB addressed a longtime issue with top runners—prize money. A chunk of the funding from the ratcheted-up Hoka sponsorship was directed to supporting the bigger prizes for the OCC, CCC and UTMB races in Chamonix—about $300,000 this year, nearly double of 2023—as well as more prize money for the three UTMB World Series Majors. (The sequence was intentional. The organization wanted a new doping policy in place before increasing prize purses, since large cash awards are often thought to lead to a growth in doping.)

It’s a move that was long overdue—the most celebrated marquee event in any sport should reward its top athletes more than any other event—but not possible without Hoka’s increased involvement. The proposal was shared with PTRA in advance of the announcement, and the group provided feedback that was incorporated into the final divvying up of the purse. The total amount spent on prize money across all UTMB races is now more than $370,000.

“We increased the prizes quite dramatically,” said UTMB Group CEO Frédéric Lenart. “It’s very important for us to support athletes in their living.”

Finally, just last week, UTMB announced a new department within the company called “Sport and Sustainability.” The group is headed by longtime UTMB staffer Fabrice Perrin. He was a driving force behind the creation of UTMB’s live coverage back in 2012. Heading up relations with the pro athletes will be longtime elite trail runner Julien Chorier. Nicolas LeGrange, UTMB’s Director of Operations, will be in charge of sustainability and DEI, Diversity, Equity Inclusion.

On the DEI front, UTMB is calling its strategy “leave no one behind,” and they promise new initiatives coming this fall so that, according to Perrin, “every athlete feels a sense of belonging within our community,” he says. “I am committed to ensuring that we perfect symbiosis with the entire community of trail running.”

UTMB has already begun to embrace adaptive athletes, something it was criticized for lacking as recently as last year. This year’s UTMB Mont Blanc races will feature a team of 12 adaptive athletes who will be participating in the MCC, OCC and UTMB races. Under the direction of adaptive athlete and team manager Boris Ghirardi, who lost his left foot and part of his left leg after a motorcycle accident in 2019, the race organization recruited the athletes from around the world to showcase how adaptability and resilience are key elements of the UTMB values.

“I proposed this program to make a concrete action around adaptive athletes and the inclusion policy, and to prove that it was possible,” he said this weekend. “If you really get everyone working on this, you can change the game.”

And with that, UTMB Mont-Blanc 2024 is underway, resuming the golden era status that Byrne raved about last August. Starting this past weekend, banners have been unfurled over Place du Triangle de l’Amitié in the heart of Chamonix, kicking off the carefully choreographed trail running Super Bowl that is UTMB. The excitement begins on August 26 and culminates as the race for UTMB individual crowns reach a tipping point on August 31. (The golden hour of the final finishers on September 1 will be something to behold, too.)

“It’s like wrapping the Tour de France, Burning Man, and the biggest industry trade show into one giant, week-long festival,” Gaylord says. “It’s an amazing week for our sport, one of the biggest showcases we have.”

The aura of Chamonix and the opportunity to run a race there is drawing as much or more interest than ever before. It is perhaps the essence of what will keep the UTMB World Series afloat into the distant future. Runners will continue to chase Running Stones at qualifying events around the world, knowing the carrot of running one of the races around the Mont Blanc massif is second to none.

Trail running is booming on a global scale, and it’s not just UTMB shouldering the burden or reaping the benefits. The Golden Trail World Series, Spartan Trail Running, Xterra Trail Running—and even the World Trail Majors, Western States 100, and dozens of other more prominent trail races—are all trying to get a bigger piece of the pie, either by way of money or relevance.

UTMB Mont Blanc, as trail running’s most important race, is at the very beating heart of it all. And trail running is a soul sport, so when change and growth happen, it can feel threatening to all of us whose lives have been changed for the better by time spent with dirt underfoot and blue sky above. UTMB is big enough now that it’s urgently important that it make changes judiciously and preemptively.

As the world’s most significant trail race, the consequences of UTMB’s choices will ripple throughout the ecosystem. UTMB understands this. “Do we owe something to trail running? Yes, of course we do,” Michel Poletti once told me. That’s truer than ever now.

At TrailCon in June, Catherine Poletti summed up UTMB’s challenge. “Trail running is changing around the world. We’ve seen that evolution over 20 years. We need to adapt, to find a good balance, to accept different models and ways of organizing.”

Back in August 2021, I wrote an article here called, “UTMB, Don’t Break Our Hearts.” It came the summer after the organization announced its investment from the Ironman Group. Change– big change– was everywhere. Could the race around Mont Blanc maintain its soul and passion amid talk of multinational sports marketing, we all wondered? Michel Poletti closed the interview by saying, “Nous prenons un rendez-vous dans trois ans.” Simply translated: “We’ll schedule an interview in three years.”

Three years is now, and both UTMB and trail running’s landscape have changed dramatically, if not literally then certainly figuratively. We’ve seen UTMB adjust its rudder this past year, responding to concerns. Perhaps not at the pace any individual or specific group would like, and not to the extent some would wish. But it’s happening, and for that we should all breathe a cautious sigh of relief. Because if you love trail running, you have to care about what happens at the world’s biggest trail race.

As I write this in Chamonix very early on the morning of August 26, overcast skies are parting and blue skies are in the offing. The forecast for the week ahead is for bright sun with a few clouds. It’s a workable enough metaphor for trail running’s future. But one thing has to happen for it to come true. The race that changed running needs to continue to listen to its stakeholders around the world, and engage with them as it grows and develops in the days ahead. If that happens, Byrne’s vision of the golden age of our sport just might linger on. I can hope.

by Outside Online

Login to leave a comment

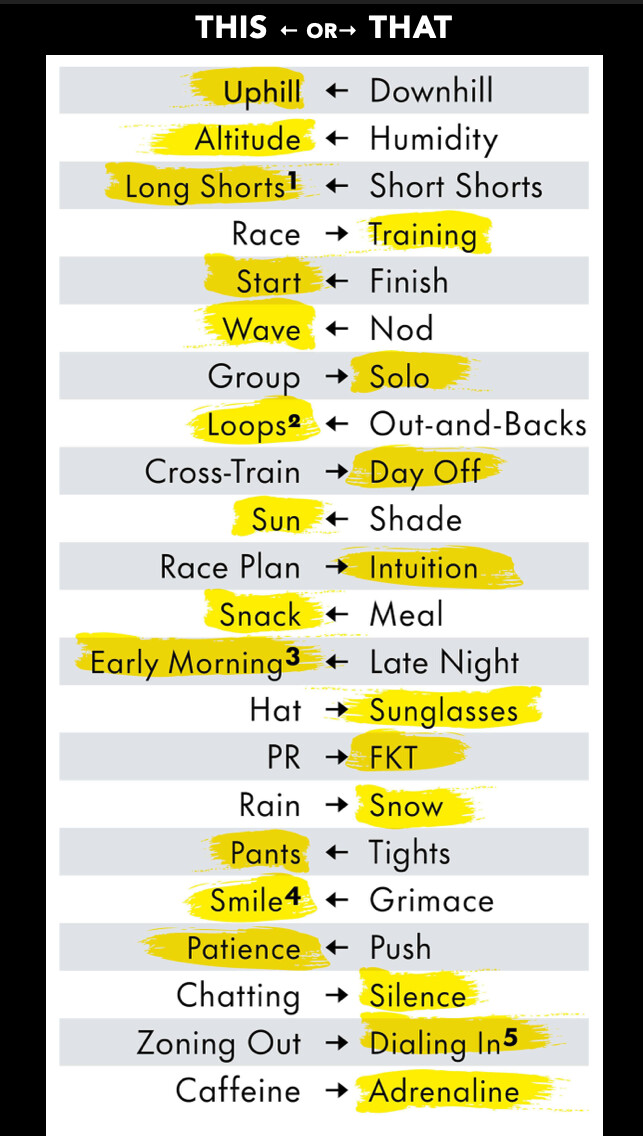

Why Ultrarunning GOAT Courtney Dauwalter Says Loops—Not Out-and-Backs—Are the Superior Route

We polled Dauwalter on some of running’s most polarizing questions. Take the quiz to see how you stack up.

In 2023, Courtney Dauwalter had one of the most legendary years in trail-running history, becoming the first person to win the Triple Crown of the 100-mile races—Western States, Hardrock, and UTMB—in a single season. This year, she’s showed no signs of slowing down, repeating as Hardrock champion and improving on her course record by over two minutes.

Courtney has a lot to say: “Comfort is key! I prefer [shorts with] long inseams because I am most comfortable in them. We should all wear the clothes that make us feel our best when we're out trying hard things.”

On the type of course: "I love any type of route, really, but loops definitely feel like big adventures. Not knowing what’s around each corner or what view you might be rewarded with is exciting.”

Race plan; “Early mornings feel so simple and peaceful. I love to drink my coffee and watch the sun rise while I plan out my day.

Courtney Explains: “Staying in the moment, focusing on taking the next step, and repeating a positive mantra are things I try to do during the toughest moments of any run.”

by Runner’World

Login to leave a comment

Ludovic Pommeret Wins Hardrock 100 in Course-Record Time Courtney Dauwalter is on course-record pace, trying to win the race for a third consecutive year

This is an ongoing story that will continue to be updated as more runners reach the finish line in Silverton, Colorado.]

Maybe you forgot that Ludovic Pommeret was the 2016 Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc champion. Or that he was the fifth-place finisher in Chamonix, France, just last year. Or maybe you thought the 49-year-old Frenchman was past his prime. Either way, he reminded us all he’s at the top of not only his game, but the game at the 2024 Hardrock 100.

The Hoka-sponsored runner from Prevessin, France, took the lead less than a third of the way into the rugged 100.5-mile clockwise-edition of the course after separating from countryman François D’Haene, the 2021 Hardrock champion and 2022 runner-up, and never looked back. Pommeret progressively chipped away at the course record splits—a course record, mind you, set by none other than Kilian Jornet in 2022—to win this year’s event in 21:33:12, the fastest time in the race’s 33-year history. Jornet set the previous overall course record of 21:36:24, also in this clockwise direction in 2022.

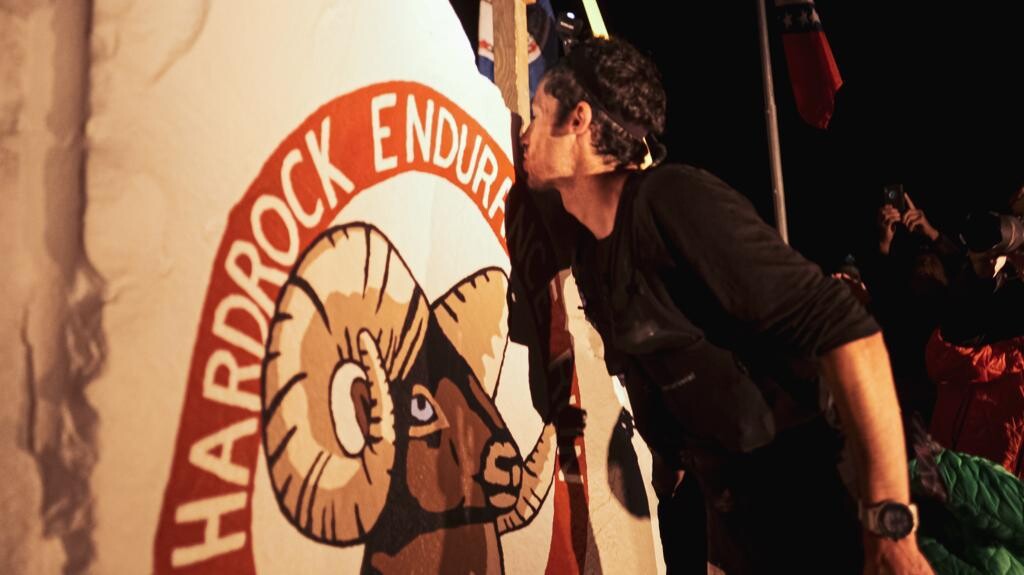

(Pommeret kissed the rock in to complete the course in 21:33:07 at 4:33 A.M. local time, but race officials credited him with the slightly slower official time.)

“It was my dream (to win it),” Pommert told a small collection of fans and media after winning the race at 3:33 A.M. local time. “I was just asking ‘when will there be a nightmare?’ But finally, there was no nightmare. Thanks to my crew. They were amazing. And thanks to all of you. This race is, uh, no word, just so cool and wild and tough.”

On Friday, July 12, 146 lucky runners embarked on the 2024 Hardrock 100. Run in the clockwise direction this year, it was the “easy” way for the course with a staggering 33,000 feet of climbing and an average elevation over 11,000 feet thanks to the steep climbs and more tempered, runnable descents.

Combined with relatively cooperative weather (hot during the day on Friday, but no storms) and a star-studded front of the pack headlined by Courtney Dauwalter and D’Haene, the tight-knit Hardrock 100 community was on course record watch.

And the event delivered—along with a whole lot more.

On the men’s side, the front of the race took a blow before the gun even went off when Zach Miller, last year’s Ultra-Trail du Mont Blanc runner-up, was denied entry after undergoing an emergency appendectomy the weekend before.

Despite the heartbreak of being forced to wait another year to participate in this hallowed event, Miller was very much a presence in the race, most notably for slinging fastnachts (Amish donuts) from his van in Ouray for race supporters and fans.

Such is the spirit of this event, deemed equally as much a run as a race.

The men’s race was further upended when D’Haene, in tears surrounded by his wife, three children, and friends, dropped from the race at the remote Animas Forks aid station (mile 58). An illness from two weeks before proved insurmountable for the challenge ahead. That blew the door wide open for the hard-charging leaders ahead.

Pommeret had built a 45-minute lead over Jason Schlarb, an American runner who lives locally in Durango, and Swiss runner Diego Pazosby, the time he had left the 43.9-mile Ouray aid station amid 85-degree temperatures. His split climbing up and over 12,800-foot Engineer Pass (mile 51.8) extended his lead to more than an hour over Schlarb and nearly 90-minutes at the Animas Forks aid station.

“I thought it was great. To run off the front like he did, and then just hold that all day and get the overall course record is pretty awesome,” Miller said. “When Killian did it, two years ago, it was a, it was a track race between him, Dakota, and François, after they got some separation from Dakota, it was Kilian and and François, all the way to Cunningham Gulch (the mile 91 aid station) and then Kilian just torched it on the way in. So yeah, it was super, super impressive for Ludo to do that. That’s a very impressive effort.”

The sleepy historic mining town of Silverton, Colorado was unusually hectic at 6 A.M. on Friday. In the blue hour before the sun poked over the San Juan Mountains looming above, 146 runners toed the start line of the Hardrock 100, marked by flags from the countries represented by competitors on either side of the dirt road.

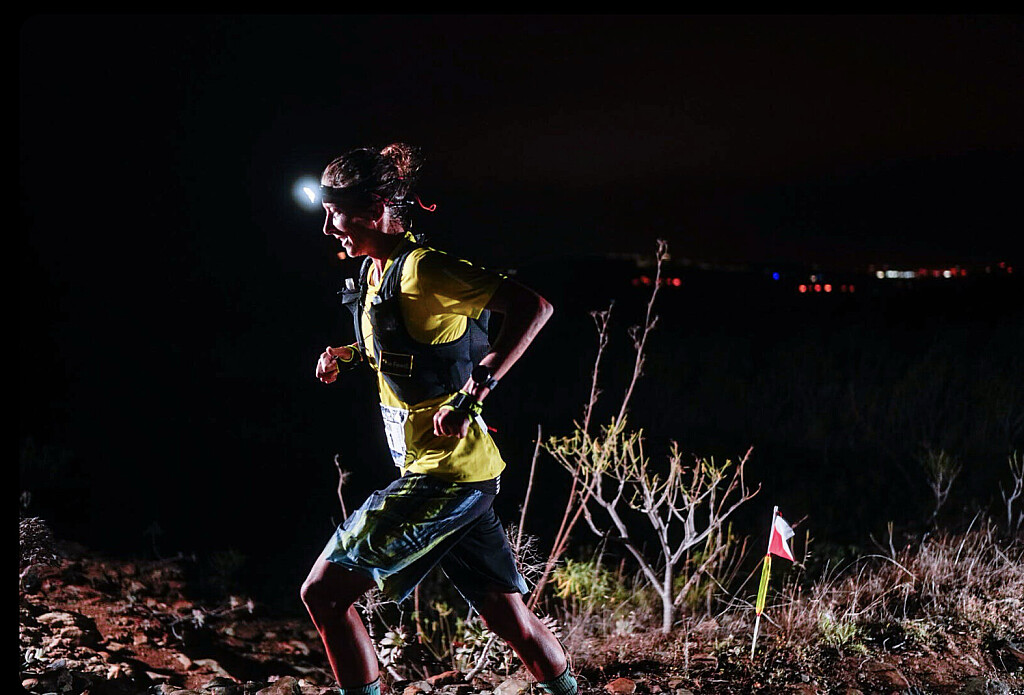

With the sound of the gun, runners jogged off the start line—their caution a tacit sign of respect for the monumental challenge of what was to come. As the runners passed through town to the singletrack wending its way up to Miner’s Shrine, group of men headlined by D’Haene, Ludovic Pommeret, Diego Pazos, and Jason Schlarb quickly took command of the front, the bright yellow t-shirt of Courtney Dauwalter was easy to spot just behind, along with Katharina Hartmuth and Camille Bruyas.

If they weren’t awake already, runners certainly were after crossing the ice-cold Mineral Creek two miles into their journey before starting the grunt up to Putnam Basin. At the top of a sunny, grassy Putnam Ridge (mile 7) 1:34 into the race, the lead pack of men remained, while Dauwalter had made a statement solo just three minutes back from the men and four minutes up on Hartmuth.

Dauwalter was smiling and chatty when she reached the KT aid station at mile 11.5, in 2:24 elapsed. By Chapman (mile 18.4), four hours in and 10 minutes under her own course record pace, she was pouring water on her head under the blazing sun. Things were heating up—in more ways than one.

When Pommeret galloped into Telluride (mile 27.7) after 5:37 of elapsed time in the lead, he was right on Jornet’s course record pace. One minute, some fluids and restocking later, and he was gone.

But wait, it was still a close race! D’Haene charged into Telluride just two minutes later and hardly stopped before continuing on through downtown before busting out the poles and starting the steep, steep 5,000-foot climb up Virginius Pass to the iconic Kroger’s Canteen aid station nestled into a notch of rock at the top at 13,000 feet.

Not to be outdone, the women’s race proved equally thrilling coming into Telluride. Bruyas bridged the gap up to Dauwalter, and the two ran into town together in 6:25 elapsed. Both took three minutes in the aid station, although that must have been enough social time for Dauwalter, as she pulled ahead marching up the climb, poles out and head down. A bouncy Bruyas alternated between hiking and jogging just behind.

But time again again, Dauwalter’s long, powerful stride simply proved unparalleled. By Kroger’s (mile 32.7) Dauwalter had reestablished her lead by five minutes over Bruyas and 17 ahead of Hartmuth in third. She’d built that gap to 10 minutes in Ouray at mile 43.9, but she left that aid station in less than two minutes with a stern, serious look on her face. But as she crested Engineer Pass at the golden hour, wildflowers blanketing the vibrant green hillsides basking in the setting sun, she enjoyed a 30-minute lead in the women’s race and was knocking at the door of the men’s podium.

While Dauwalter forged ahead with her unforgiving campaign for a third straight win, the men’s race started to rumble. Like Dauwalter, Pommeret continued to blaze the lead looking strong as he trotted down Engineer to the Animas Forks aid station at mile 57.9 in 11:39 elapsed. He hardly stopped before continuing on to Handies Peak, which at 14,058 feet marks the high point of the race. He had blown the race wide open.

An hour and 15 minutes later, Schlarb, looking a bit more beleaguered, ran into Animas Forks with his pacer, where he sat down and changed his shirt while receiving a pep talk from his partner and son. But he made quick work of the time off feet nonetheless, and three minutes later he was back at it, seven minutes before Pazos appeared.

While D’Haene arrived just 10 minutes later, he did so in tears, holding the hand of his youngest son. After a considerable amount of time sitting in the aid station, surrounded by his family and crew, he called it quits. The lingering effects of an illness from just 10 days before proved too much to overcome as the hardest miles of the race loomed ahead.

While D’Haene pondered his fate, Dauwalter blitzed into Animas Forks in 13:26 with that same look of determination, 16 minutes ahead of course-record pace. She briefly stopped to prepare for the impending night, picking up her good friend and pacer Mike Ambrose to leave the aid station in fourth overall. Bruyas maintained her second place position 30 minutes back, with Hartmuth in third about 20 minutes behind her.