Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #strength training

Today's Running News

This Is What It Really Takes to Get Faster

Every runner who dreams of shaving seconds—or minutes—off their personal best has to confront one truth: speed is earned through consistent work, not a single breakthrough workout.

Build Your Base First

“You can’t get faster if you don’t already have an aerobic base,” says Kelly Roberts, RRCA-certified coach and founder of the Badass Lady Gang. That base comes from running three to four times per week for about 40 minutes at a conversational pace. Once you can sustain that comfortably, you’re ready to introduce speed work.

Speed Comes From Teaching Your Body to Run Fast

“Speed doesn’t come from one magical workout,” says Jes Woods, RRCA-certified Nike Running coach. “It comes from consistent speed work. That’s where you actually teach your body how to run fast.”

Speed work develops efficiency: better oxygen use, quicker lactate clearing, and greater tolerance for harder efforts. In short, it trains your body to handle more stress—and recover from it—at faster paces.

What Speed Workouts Look Like

You can build speed in several ways:

• Intervals: Fast segments with recoveries.

• Fartleks: Speed play with less structure.

• Tempo runs: Steady efforts just outside your comfort zone.

• Hill sprints: Strength and power mixed with speed.

A solid weekly plan to improve speed usually includes 1–2 speed sessions, 1–2 easy runs, one strength day, and a long run. Easy runs promote recovery, strength training builds power and stability, and long runs expand endurance—all essential pieces alongside your speed days.

“That balance allows your body to stress, adapt, and recover in the right proportions,” Woods says.

The Mental Side of Getting Faster

Speed training isn’t just physical. Roberts says the hardest part is managing the mental noise when things get uncomfortable.

“When you run faster, everything gets louder,” she says. “Your legs scream, and the little parrots on your shoulder scream back.”

Her advice: pay attention to self-talk and lean on mantras. One of her go-tos is, “I don’t know if I can do this. Let’s see what happens when I give my best.”

When You’ll Start Seeing Results

If you train consistently, most runners notice progress in six to eight weeks. Research backs this up: intermittent sprint training improved 10K times in six weeks in one study, and VO₂ max increased significantly after eight weeks of aerobic training in another.

“You’ll feel different,” Roberts says. “Your runs will feel easier as your aerobic strength improves.”

Beginner vs. Experienced Runners

Genetics, training history, and consistency all shape how quickly you’ll get faster. Some runners respond more quickly, while others chip away over time. But beginners often see the biggest gains because there’s more room for improvement.

“If you’re looking to get faster, you’ll never see bigger PR swings than you will as a new runner,” Roberts says.

The Bottom Line

Speed is attainable for every runner. Build your base, train consistently, mix your workouts, and practice staying calm when things get uncomfortable. Over time, the seconds will fall off—and you’ll become a faster, stronger version of yourself.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Unlocking Speed: How to Train Smarter, Not Just Harder

Every runner dreams of getting faster. Whether you’re chasing a new 5K PR, gunning for a sub-40 10K, or eyeing a breakthrough marathon time, there’s nothing quite like shaving seconds—or even minutes—off your personal best. But here’s the truth: speed isn’t just about grinding harder. It’s about training smarter.

Build the Foundation First

Speed starts with your aerobic base. You can’t build a skyscraper on shaky ground. Many runners make the mistake of jumping into intervals before their base is solid, only to plateau or burn out. If your weekly mileage is inconsistent or too low, speedwork won’t deliver the gains you’re chasing.

The solution? Commit to regular easy runs and gradually increase your weekly volume. Keep most of your mileage at a conversational pace. This aerobic engine is what powers every fast finish later on.

Add Intentional Intensity

Once your base is strong, it’s time to add focused intensity. Intervals, tempo runs, progression runs, and hill sprints teach your body how to run fast and hold pace under fatigue. But more is not always better. Overdoing hard sessions leads to injury or stagnation.

Limit yourself to 1–2 quality workouts per week. Your goal is adaptation—not exhaustion. Be consistent, not heroic.

Train Your Running Economy

Running fast isn’t just about cardiovascular fitness. It’s also about efficiency—how well you translate effort into forward motion. That’s where strides, form drills, and strength training come in. Just two sessions of resistance training per week can improve muscle balance and coordination.

Want bonus gains? Add plyometrics (like skipping or bounding) to enhance your ground contact power and neuromuscular sharpness. The smoother and more economical your stride, the faster your splits—without extra effort.

Mindset: The Final Gear

Speed begins in the mind. Confidence, mental toughness, and consistency often outlast raw talent. It’s not enough to hope you’ll run faster—you have to believe it. That belief is built in the quiet moments: when you finish the workout you almost skipped, when you log another steady week, when you visualize your goal on race day.

Fast runners aren’t born—they’re made. Piece by piece. Mile by mile.

So next time you lace up, remember: getting faster isn’t about magic workouts or chasing the pain. It’s about smart, intentional, consistent training. And it’s within your reach.

Speed is earned. Now go earn yours.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Staying on Track: Expert Advice on Injury Prevention for Long-Distance Runners

As a long-distance runner, you've likely experienced the frustration of an injury that sidelines you from training and competition. Injuries can be a significant setback, but with the right strategies, you can reduce your risk and stay on track. In this article, we'll explore expert advice and tips on injury prevention, covering topics such as strength training, proper running form, recovery, and injury management.

Understanding Common Injuries

Long-distance runners are prone to a range of injuries, including shin splints, plantar fasciitis, and runner's knee. These injuries often result from overtraining, poor biomechanics, and inadequate recovery. By understanding the causes of these injuries, you can take steps to prevent them.

Strengthening Your Foundation

Strength training is a crucial component of injury prevention for long-distance runners. By strengthening your muscles, you can improve your running efficiency, reduce your risk of injury, and enhance your overall performance. Some key exercises to include in your strength training routine are:

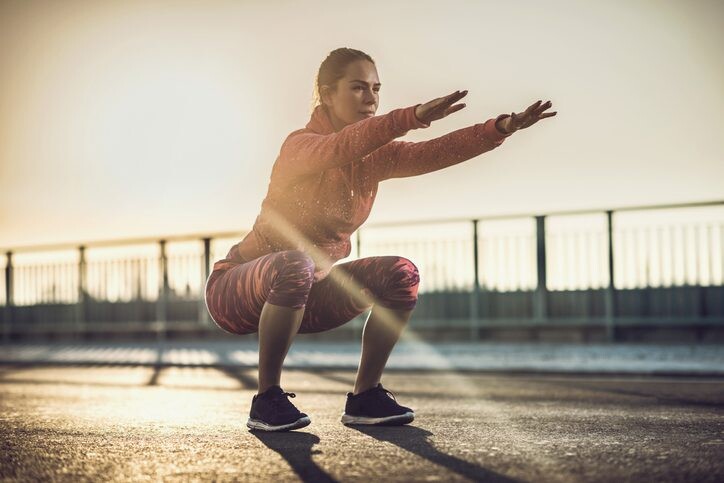

- Glute bridges and squats to improve hip and knee stability

- Calf raises and ankle exercises to strengthen your feet and ankles

- Core exercises to enhance stability and balance

The Right Shoes for Injury Prevention

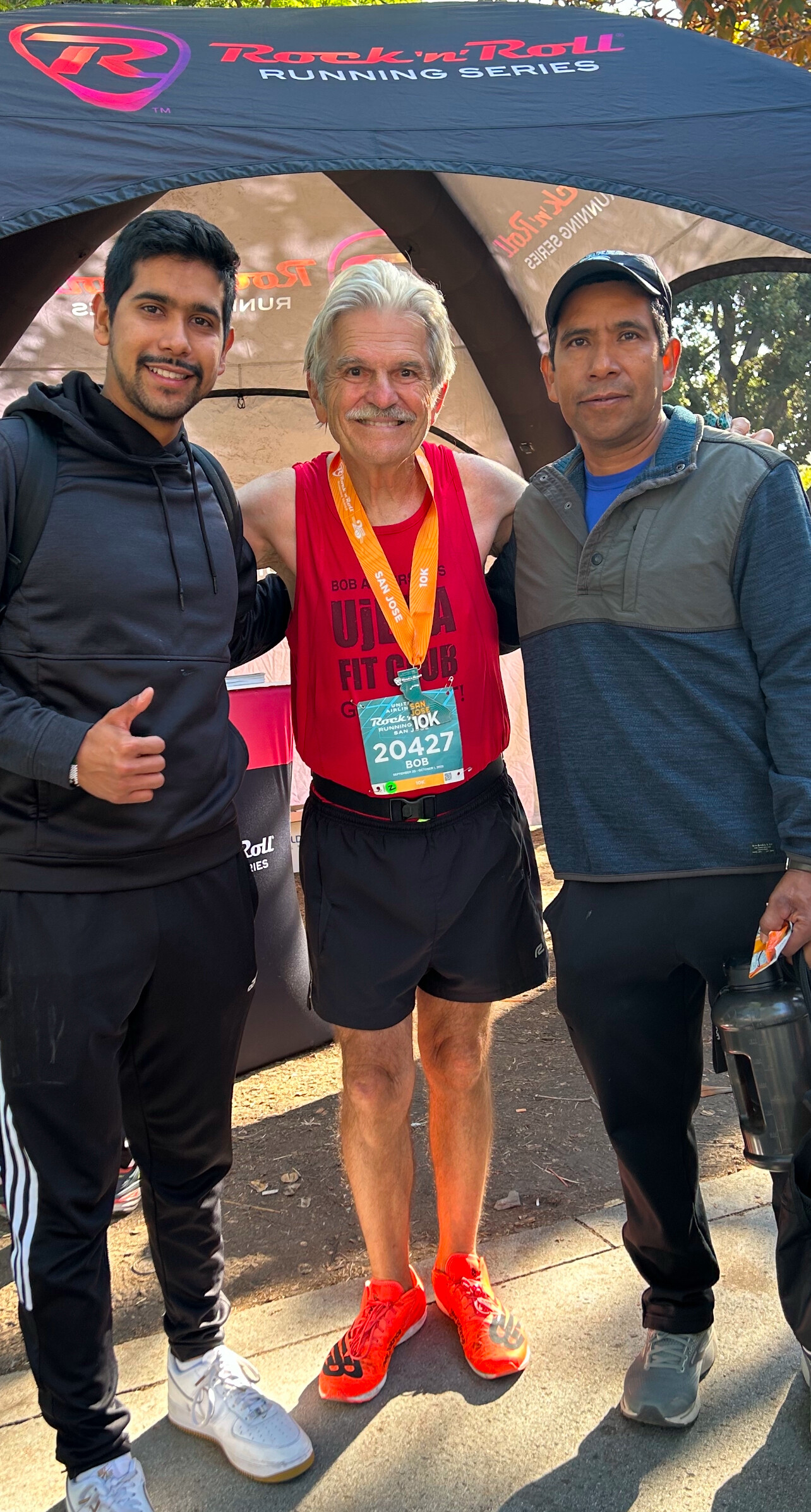

Running shoes play a critical role in injury prevention. Worn-out shoes can lead to a range of problems, including increased impact on joints, poor foot mechanics, and increased risk of overuse injuries. According to Bob Anderson, a lifetime runner with over 60 years of experience, "Don't risk your running longevity by training in worn-out shoes. Rotating shoes is key - I have multiple pairs that I rotate through, which helps extend the life of each shoe and reduces my risk of injury." By having multiple pairs of shoes and rotating them regularly, you can reduce your risk of injury and ensure that your shoes are always providing the support and cushioning you need.

When choosing running shoes, consider the following factors:

- Support and stability: Look for shoes that provide adequate support and stability for your foot type and running style.

- Cushioning: Choose shoes with sufficient cushioning to absorb the impact of running.

- Fit: Ensure a comfortable fit that doesn't constrict your toes or heel.

Proper Running Form

Good running form can help reduce your risk of injury and improve your performance. Here are some tips to improve your running form:

- Maintain good posture and alignment

- Focus on a midfoot or forefoot strike, rather than heel striking

- Keep your stride length and cadence efficient

- Use your arms to help drive your running motion

Recovery and Injury Management

Recovery is a critical component of injury prevention. By allowing your body time to recover between hard runs, you can reduce your risk of injury and improve your performance. Some key recovery strategies include:

- Stretching and foam rolling to reduce muscle tension

- Rest and recovery days to allow your body to repair and rebuild

- Nutrition and hydration strategies to support your training

Some final thoughts

By incorporating these strategies into your training routine, you can reduce your risk of injury and stay on track to achieving your running goals. Whether you're training for a marathon or simply looking to stay healthy and active, injury prevention is key to success. With the right approach, you can enjoy a long and healthy running career.

by Sally Decker

Login to leave a comment

CAN YOU RUN A MARATHON WITHOUT TRAINING?

Despite what you might see on social media, we definitely do not recommend attempting a marathon without proper training.

Running 26.2 miles is a tremendous physical challenge, and attempting it unprepared not only risks injury but also makes the experience extremely difficult. Respect the distance and put in the necessary preparation.

TOP TIPS FOR MARATHON TRAINING

• Start Early: Begin your training as early as possible—ideally six months before race day. Don’t think of it as “marathon training” from day one. Break it into smaller training blocks. Building a strong base before starting a structured plan will help develop your fitness and strength, setting you up for success.

• Follow a Structured Plan: Use an app like Runna or work with a coach to create a training plan tailored to your goals. Structured plans provide consistency and can be adjusted if you encounter setbacks along the way.

• Consistency Is Key: Aim to run at least three times a week. Consistency is the foundation of marathon training. However, listen to your body—take extra rest days if you’re dealing with soreness or minor issues.

• Fuel and Hydrate Properly: Learn how to fuel and hydrate effectively before, during, and after runs. Focus on simple carbohydrates before a run and a mix of carbohydrates and protein afterward to aid recovery and replenish energy stores.

• Incorporate Cross-Training and Strength Work: Complement your running with cross-training activities like swimming, cycling, or elliptical sessions. Include one or two strength training sessions per week with exercises like squats, deadlifts, lunges, and core work.

• Prioritize Recovery: Recovery is as important as training. Use foam rolling, stretching, and yoga to aid recovery, and prioritize sleep—especially as training intensifies.

WHAT DOES A MARATHON TRAINING PLAN LOOK LIKE?

Our 16-week marathon training plan (available on our website) features four runs per week, carefully structured to help you build endurance and confidence. Here’s a look at what it entails:

Week 1:

• A 30-minute easy run

• A 5-mile (8 km) easy/steady run with strides

• An interval workout of 2 sets of 5 x 1-minute intervals

• A 60-minute long run

This structure is typical of most marathon training plans. If this feels too challenging, focus on gradually building up your mileage and consistency before starting the full plan.

As training progresses, long runs will increase in distance, and workouts will introduce marathon-specific pace work to prepare you for race day.

Peak Week:

• A 30-minute easy run

• A 6-mile (10 km) easy/steady run with strides

• An interval workout of 2 sets of 10 x 1-minute intervals

• An 18.6-mile (30 km) long run

With the right plan, dedication, and consistency, you’ll be well-prepared to conquer 26.2 miles.

by Mark Dredge

Login to leave a comment

Cameron Myers - Australia’s Middle-Distance Prodigy Breaking Records

Cameron Myers, an 18-year-old Australian middle-distance runner from Canberra, has rapidly ascended in the athletics world, setting multiple records and showcasing exceptional talent on the international stage.

Early Life and Training

Myers began his athletic journey at the age of 10 under the guidance of coach Lee Bobbin. By 14, he transitioned to training with renowned coach Dick Telford, integrating into a group that included Olympian Jye Edwards. This foundational period was crucial in developing the skills that would later define his career.

Record-Breaking Performances

In February 2023, at just 16 years and 259 days old, Myers became the second-youngest person ever to run a sub-four-minute mile, clocking 3:55.44 at the Maurie Plant Meet in Melbourne. This performance surpassed Jakob Ingebrigtsen’s age-group record by over two seconds. Later that year, he set a world U18 best in the 1500m with a time of 3:33.26 at the Diamond League event in Chorzów, Poland.

Continuing his upward trajectory, Myers began 2025 with a series of remarkable achievements. On January 25, he shattered the world U20 indoor mile record at the Dr. Sander Invitational in New York, posting a time of 3:53.12. This feat eclipsed the previous record held since 2009. A week later, at the New Balance Indoor Grand Prix in Boston, he set a national record in the 3000m, finishing in 7:33.12.

Recent Competitions

In February 2025, Myers competed in the prestigious Wanamaker Mile at the Millrose Games in New York. Facing a field that included Olympic medalists, he secured third place with a time of 3:47.48, breaking his own world U20 mile record and equaling the Australian national record set by Oliver Hoare in 2022. This performance also marked the first time an under-20 athlete ran the mile in under 3:48.

Most recently, on March 29, 2025, Myers led the 1500m from start to finish at the Maurie Plant Meet in Melbourne, winning with a time of 3:34.98. His commanding performance against a competitive field further solidified his status as a rising star in middle-distance running.

Training and Future Aspirations

Under Telford’s mentorship, Myers has intensified his training regimen, incorporating strength training, altitude sessions, and rigorous threshold workouts to address areas of improvement. Despite narrowly missing qualification for the Paris Olympics, these experiences have fueled his determination to excel in future competitions. With his current trajectory, Myers is poised to make significant contributions to Australian athletics on the global stage.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

What It Takes to Go Beyond 26.2 - Taking on the Ultra

For many runners, crossing the marathon finish line is the pinnacle of endurance racing. But for an increasing number of athletes, 26.2 miles is just the beginning. The ultramarathon—defined as any race longer than a marathon—has surged in popularity, drawing runners eager to test their limits over 50K (31 miles), 100K (62 miles), 50 miles, 100 miles, and beyond.

But how do you make the leap from marathoner to ultramarathoner? What does it take to conquer these longer distances? Let’s break it down

The Key Differences Between a Marathon and an Ultra

While both require strong endurance, an ultramarathon is a completely different beast from a road marathon. Here’s what sets them apart:

• Pacing Is Crucial – In a marathon, you can push your pace hard and still hold on. In an ultra, going out too fast can be a disaster. Starting conservatively is essential.

• Nutrition Matters More – Running beyond 26.2 miles means your body will need real food, not just energy gels. Successful ultrarunners eat a mix of carbohydrates, protein, and fatto sustain energy levels.

• Trail Running Dominates – Many ultras take place on rugged trails, requiring technical footwork, elevation gains, and varying terrain.

• Mental Fortitude is Everything – Ultramarathons test your mental resilience as much as your physical endurance. Learning to embrace discomfort and keep moving forward is key.

How to Train for an Ultramarathon

1. Build Your Base (Time on Feet > Speedwork)

Training for an ultra isn’t just about miles—it’s about spending long hours on your feet. Instead of focusing on speed, ultra training prioritizes slow, steady endurance.

• Increase Weekly Mileage Gradually – Aim for at least 50-70 miles per week for a 50K and 70-100 miles per week for a 100K or 100-miler.

• Back-to-Back Long Runs – Instead of one long run, many ultra plans include two long runs on consecutive days to simulate running on tired legs.

• Practice Hiking – Even elite ultrarunners hike the steep sections. Practicing power hiking helps conserve energy on climbs.

2. Strength Training & Mobility Work

Ultras put serious strain on your body. Strength training improves durability, while mobility work helps prevent injuries.

• Core Work – A strong core stabilizes you on technical trails.

• Leg Strength – Squats, lunges, and step-ups strengthen the quads, hamstrings, and calves.

• Ankle & Foot Mobility – Essential for navigating uneven terrain.

3. Master Race-Day Nutrition

Unlike marathons, where fueling is simpler, ultramarathon nutrition requires strategy.

• Eat Real Food – Ultras often include PB&J sandwiches, bananas, pretzels, and broth. Find what works for you in training.

• Stay Hydrated & Balance Electrolytes – Dehydration or electrolyte imbalances can end your race early.

• Fuel Frequently – Many ultrarunners eat every 30-45 minutes to avoid bonking.

4. Train for the Terrain

If your ultra is on technical trails, hills, or mountains, training in similar conditions is critical.

• Hill Repeats – Strengthen quads for long descents.

• Technical Trail Running – Practice on rocky or root-filled trails to improve footing.

• Night Running – Many ultras involve running in the dark, so get used to using a headlamp.

Mental Strategies for an Ultramarathon

Running an ultra is as much mental as physical. Even the fittest runners struggle if they aren’t mentally prepared.

• Break the Race Into Sections – Instead of focusing on the total distance, mentally divide the race into aid station segments.

• Have a Mantra – Simple phrases like “Relentless forward motion” or “One step at a time”can help during tough moments.

• Expect Lows—And Know They Pass – Every ultrarunner experiences physical and mental lows, but pushing through leads to new highs.

Choosing Your First Ultra

Not sure where to start? Here are three great entry points into ultramarathoning:

1. 50K Trail Race – A great intro, only 5 miles longer than a marathon but often on trails with varying terrain.

2. 50-Mile Race – A serious jump, requiring race-day nutrition and pacing mastery.

3. Timed Ultras (6-Hour or 12-Hour Races) – Rather than a set distance, these races challenge runners to cover as much distance as possible in a fixed time.

Should You Run an Ultra?

If you love endurance challenges, embrace the grind, and enjoy long hours on the trail, ultramarathoning might be your next big adventure. The transition from marathon to ultra isn’t just about running farther—it’s about running smarter, stronger, and with a mindset prepared for anything.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

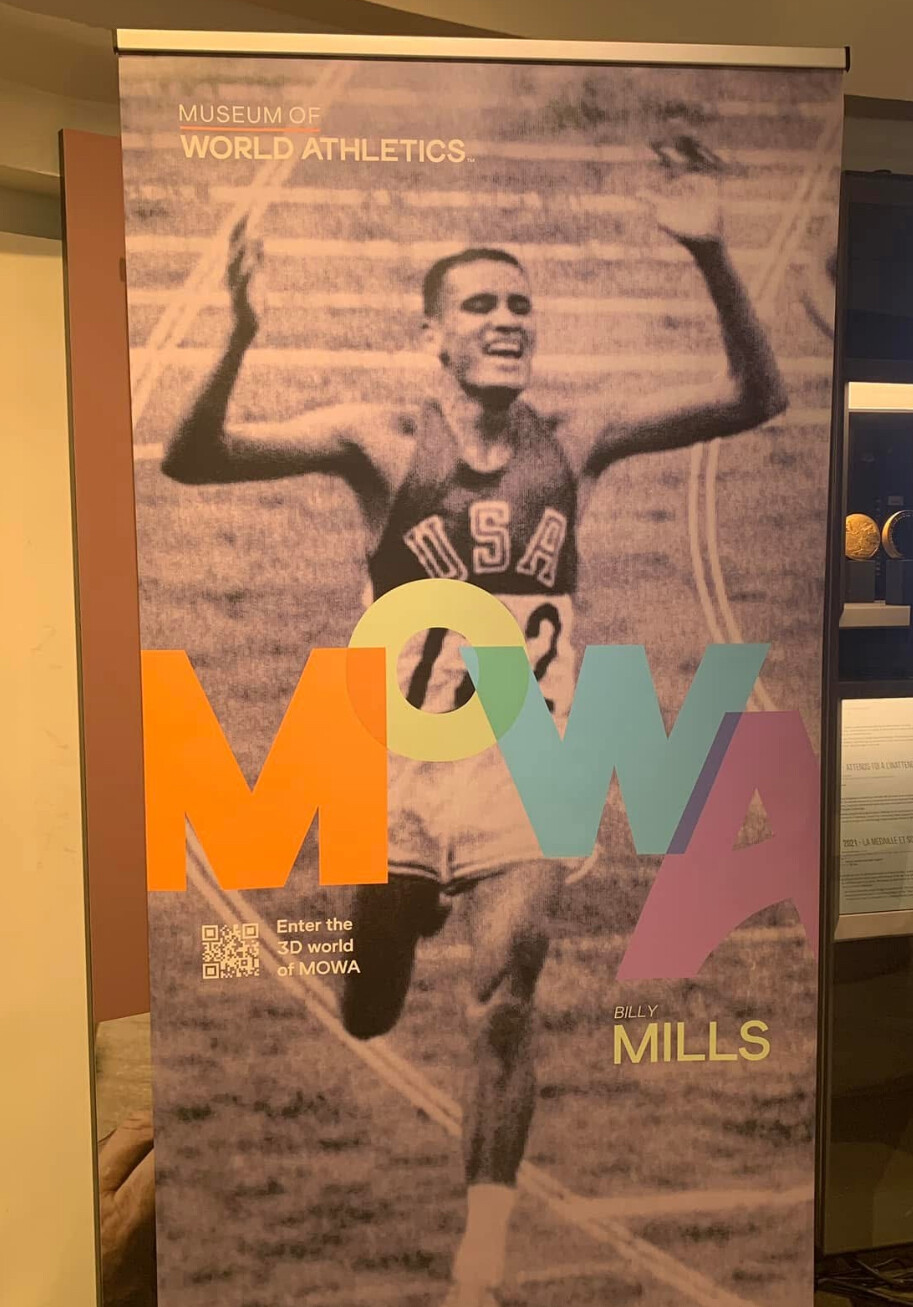

How Much Have Tracks and Shoes Improved 10,000m Times? A Look at Billy Mills’ 1964 Olympic Gold Compared to Today

When Billy Mills won the 10,000 meters at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, he shocked the world. A relative unknown at the international level, Mills surged past world record holder Ron Clarke in the final stretch to win gold in 28:24.4, setting an Olympic record. It remains one of the most famous upsets in Olympic history.

At the 2024 Paris Olympics, Billy Mills sat in the stands, watching intently as the men's 10,000-meter final unfolded. Sixty years after his historic victory in Tokyo, he witnessed another American, Grant Fisher, battling for the podium.

With two laps to go, Fisher was perfectly positioned, matching strides with the East African elites, his long, efficient stride reminiscent of Mills' own finishing kick in 1964.

As the bell rang for the final lap, Fisher surged, momentarily moving into second. Mills, now 86, leaned forward, sensing history. But in the last 100 meters, Fisher was edged out, securing bronze. Mills smiled, knowing how close greatness had come again. Fisher clocked 26:43.46, just one third of a second behind the gold medal winner.

Mills had ran his time on a cinder track, wearing "basic running shoes"—conditions that would be considered primitive compared to today’s high-tech track surfaces and carbon-plated racing shoes. Given all the advancements in running technology, how much faster could Billy Mills have run on a modern track with today’s footwear? And how much have these innovations contributed to the faster times we see today?

The Difference Between Cinder and Synthetic Tracks

One of the biggest changes in distance running over the last six decades has been the transition from cinder tracks to synthetic surfaces. Cinder tracks, composed of crushed brick, coal, or ash, provided uneven footing, absorbed energy from each step, and became soft and unpredictable when wet. Athletes often wore spikes with long, heavy pins to grip the loose surface.

By contrast, modern synthetic tracks, introduced in the late 1960s, offer a firm, springy surface that returns more energy to the runner with each stride. Research suggests that switching from a cinder track to a synthetic track can improve distance-running performance by about 1-2 percent.

For a 10,000-meter race, a 1-2 percent time reduction equates to about 17 to 34 seconds. This means that if Billy Mills had run his race on a modern track, his time could have been anywhere between 27:50 and 28:07 just from the track surface alone.

The Impact of Modern Running Shoes

The second major advancement in distance running has been the development of carbon-plated racing shoes with high-energy-return foams. The latest models, introduced after 2016, are designed to reduce energy loss with each step, making it easier for runners to maintain their pace over long distances. Studies suggest these shoes provide 2-4 percent energy savings, which translates to a 30-60 second improvement over 10,000 meters.

Adding this to the estimated track advantage, Mills’ performance could have been further improved, bringing his potential time down to around 26:50 to 27:30.

Comparing Billy Mills’ Performance to Modern Champions

The current Olympic record for the 10,000 meters was set by Uganda’s Joshua Cheptegei at the 2024 Paris Olympics with a time of 26:43.14. That’s 1 minute and 41 seconds faster than Mills' winning time.

However, when we factor in advancements in track surfaces and footwear, the estimated modern equivalent of Mills’ race suggests he could have run within a minute of today’s best, making him far more competitive by modern standards than his official time suggests.

Other Factors That Have Led to Faster 10,000m Times

While tracks and shoes play a significant role in faster performances, several other factors have contributed to the improvement in 10,000-meter times over the decades:

More specialized training. Today’s distance runners have more scientifically tailored training programs, including altitude training, precise recovery strategies, and improved strength training techniques.

Better pacing and race strategy. Modern races are often assisted by pacemakers who set a steady, fast pace, helping runners conserve energy and stay consistent. In contrast, Mills’ race was a classic tactical battle with surges and slow-downs.

Nutritional and recovery advances. Today’s runners have access to optimized hydration, fueling, and recovery methods that allow them to train harder and more efficiently.

Billy Mills’ Performance in Context

Billy Mills’ gold medal run remains one of the most inspiring performances in Olympic history, not just because of the time he ran, but because of the way he won. His dramatic sprint finish against heavily favored competitors on a slower, less predictable surface showcased his incredible talent, toughness, and racing instincts.

Had he raced under today’s conditions with modern advantages, Mills likely would have been among the best in the world by today’s standards. His story is a reminder that while technology has helped athletes run faster, the heart and determination behind great performances remain unchanged.

The next time you watch an Olympic 10,000-meter race, consider just how much conditions have changed since 1964—and how incredible it was for Billy Mills to win on that cinder track with the tools available at the time. His legacy stands as a testament to the pure competitive spirit of running.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

The Science of Longevity in Running: How Some Runners Stay Fast for Decades

Running is often thought of as a young person’s sport, but time and time again, we see athletes defying age, continuing to run and even race well into their 60s, 70s, and beyond. Some runners, like My Best Runs founder Bob Anderson, who started running in February 1962 and is still going strong today, prove that longevity in the sport isn’t just possible—it’s achievable with the right approach.

What allows some runners to maintain speed and endurance over the decades while others slow down? The answer lies in science, training adaptations, mindset, and lifestyle choices. This article explores how runners can stay competitive for life—and perhaps even improve with age.

The Science of Aging and Running Performance

Physiologically, runners experience certain changes as they age:

• VO2 max naturally declines at a rate of about 10% per decade after 40. However, regular training can slow this decline significantly.

• Muscle fibers shrink, and fast-twitch fibers deteriorate faster than slow-twitch fibers, impacting speed and power. Strength training and sprint workouts can help counteract this.

• Tendons lose elasticity, and cartilage wear increases, making injury prevention crucial.

• The body takes longer to recover from hard workouts, making rest, nutrition, and cross-training essential for long-term success.

The good news is that lifelong runners often have stronger hearts, denser bones, and slower biological aging than non-runners. Regular endurance training can reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and cognitive decline.

Training Smart: Adapting Workouts for Longevity

Many runners burn out or get injured because they don’t adjust their training as they age. Here’s how to train smart for decades.

Maintain Speed with Strides and Intervals

Fast-twitch muscle fibers decline faster than slow-twitch fibers, but incorporating short sprints, strides, and intervals helps retain speed. Even just six to eight 100-meter strides at the end of easy runs can keep the neuromuscular system sharp.

Prioritize Strength Training

Strength training two to three times per week can help counteract muscle loss, improve bone density, and prevent injuries. Key exercises include squats, lunges, core work, and hip mobility drills.

Adjust Recovery

Younger runners recover quickly, but for those over 50, rest and active recovery days become more important. Running every day might not be sustainable, but alternating hard workouts with cross-training, such as cycling, swimming, or hiking, can help maintain fitness without overuse injuries.

Keep Mileage Consistent

Aging runners who maintain a consistent but moderate mileage base tend to perform better long-term than those who dramatically reduce or increase mileage. The key is staying active year-round and avoiding long breaks that lead to muscle loss and decreased aerobic capacity.

Nutrition and Recovery: Fueling for the Long Run

Proper nutrition plays a major role in running longevity.

Focus on Anti-Inflammatory Foods

Chronic inflammation contributes to aging and joint pain. Long-term runners benefit from foods rich in omega-3s (salmon, walnuts), antioxidants (berries, leafy greens), and lean proteins (chicken, beans).

Stay Hydrated and Maintain Electrolyte Balance

As we age, our sense of thirst declines, so staying hydrated becomes more critical. Older runners are also more prone to electrolyte imbalances, making magnesium, sodium, and potassium intake vital.

Increase Protein Intake

After 50, the body needs more protein to maintain muscle mass. Aim for 1.2–1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily, focusing on high-quality sources like eggs, lean meats, Greek yogurt, and plant-based proteins.

Mental Toughness and Staying Motivated

Longevity in running isn’t just about the body—it’s also about the mind. Many lifelong runners stay motivated by setting new goals, training with a group, and embracing the aging process rather than resisting it.

Bob Anderson, founder of My Best Runs, started running in February 1962 and continues to train and race today. His ability to sustain a high level of performance comes down to consistent training, smart adaptations, and a passion for the sport. His 6:59 per mile pace for 350 miles of racing (50 races totally 350.8 miles over one year) at age 64 is proof that age is just a number when you train right. More recently he ran 49:48 for 10k at age 76.

The Role of Cross-Training and Injury Prevention

Even the most dedicated runners face injuries. The key to longevity is knowing when to rest and when to cross-train.

Some of the best cross-training options for runners over 50 include cycling, swimming, pickleball, hiking, and yoga. Incorporating at least one non-running workout per week reduces injury risk and keeps running sustainable for the long haul.

Gene Dykes and Rosa Mota: Icons of Running Longevity

Bob Anderson is not alone in proving that age is just a number. Gene Dykes, one of the most remarkable masters runners in history, has shattered records in his 70s. At age 70, he famously ran a 2:54:23 marathon.

His secret? A high-mileage approach combined with interval training and a love for the sport that keeps him motivated year after year.

On the women's side, Rosa Mota, the legendary Portuguese marathoner and 1988 Olympic gold medalist, continues to inspire runners worldwide. Even in her 60s, she remains an active ambassador for the sport, showing that passion, consistency, and smart training allow runners to stay competitive for life.

In December 2024, at age 66, Rosa Mota set a new W65 10K world record by completing the San Silvestre Vallecana race in 38:23.

Both Dykes and Mota exemplify the idea that the body can continue to perform at a high level if treated right. Their stories, along with those of runners like Bob Anderson, prove that longevity in running is not just about genetics-it's about persistence, training adaptations, and maintaining the joy of ring.

Final Thoughts: Running for Life

Longevity in running isn’t about fighting age—it’s about embracing the journey, adapting intelligently, and staying passionate. The best runners understand that while paces may slow, the love of the sport grows deeper with time.

Whether you’ve been running since February 1962 like Bob Anderson or are just starting in your 50s or 60s, consistency, smart training, and joy in the process are the real secrets to running for life.

by Boras Baron

Login to leave a comment

Harnessing Muscle Memory: Returning to Running After a Break

After taking a break from running, you might be pleasantly surprised to find that your legs instinctively remember the rhythm and motion once you lace up again. This phenomenon, known as muscle memory, allows previously trained muscles to quickly regain strength and coordination, even after extended periods of inactivity.

Understanding Muscle Memory

Muscle memory refers to the process by which repetitive physical activities are ingrained into your neuromuscular system, enabling movements to become more automatic over time. When you engage in activities like running, your brain and muscles develop a synchronized pattern through consistent practice. Even after a break, these established neural pathways facilitate a quicker return to form.

The Science Behind Muscle Memory

Research indicates that after a period of detraining, muscles can rapidly regain strength upon resumption of activity. A study from the University of Jyväskylä found that participants who took a 10-week break from strength training were able to return to their previous strength levels within five weeks of retraining. This suggests that the neuromuscular adaptations from prior training persist, allowing for efficient reacquisition of strength and coordination.

Maximizing Muscle Memory in Running

To harness the benefits of muscle memory and ensure a smooth transition back into running, consider the following strategies:

Start Slowly: Begin with shorter, less intense runs to allow your muscles and joints to readjust. Gradually increase your mileage and intensity to prevent overuse injuries.

Incorporate Strength Training: Engage in resistance exercises targeting key running muscles, such as the quadriceps, hamstrings, and calves. Strengthening these areas supports better performance and reduces injury risk.

Prioritize Flexibility: Regular stretching, especially of the lower body, enhances flexibility and aids in maintaining proper running form. Dynamic stretches before runs and static stretches afterward can be beneficial.

Listen to Your Body: Pay attention to any discomfort or pain. It's essential to differentiate between normal post-exercise soreness and potential injury signals. Rest as needed to allow for adequate recovery.

Maintain Consistency: Establish a regular running schedule to reinforce neuromuscular patterns and build endurance. Consistency is key to reestablishing and strengthening muscle memory.

Muscle memory serves as a valuable ally when returning to running after a break. By understanding and leveraging this phenomenon, you can ease back into your routine more effectively, reducing the risk of injury and enhancing overall performance. Remember to progress gradually, incorporate complementary strength and flexibility exercises, and listen to your body's signals to make the most of your return to running.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

These kettlebell exercises could be the key to your next PB

Bored of your stale strength training routine? The kettlebell can be a runner’s best friend, and we have the perfect exercises to get you started. Kettlebells are a simple tool ideal for building strength where it matters most, and these exercises target your glutes, hamstrings, core and back—the same areas that take a beating from the repetitive impact of running.

Whether you’re aiming to prevent injuries or boost your speed and power, kettlebell training can deliver solid rewards in minimal time.

What makes kettlebells special? Unlike traditional strength moves, kettlebell exercises fire up multiple muscle groups at once, giving you a full-body workout that translates directly to better running performance on any terrain.

Kettlebell goblet squat

To do a kettlebell squat, hold the kettlebell close to your chest in the “goblet” position, keeping your elbows tucked.

Stand with your feet slightly wider than shoulder-width, toes pointed slightly out.

Lower your hips back and down like sitting in a chair, keeping your chest up and knees tracking over your toes.

Press through your heels to return to standing, squeezing your glutes at the top.

Kettlebell row

For a kettlebell row, place the kettlebell on the ground, hinge at your hips with a flat back, and rest one hand on a sturdy surface for support.

Grip the kettlebell with the opposite hand, keeping your shoulder away from your ear.

Pull the kettlebell toward your ribs by engaging your back, then lower it slowly with control. Keep your core tight and avoid twisting your torso.

Kettlebell swing

Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart and the kettlebell on the ground between your feet Hinge at your hips, keeping your back flat, and grab the kettlebell with both hands, squeezing your arms toward one another.

Hike the kettle back between your legs like a football snap, then thrust your hips forward to swing the kettlebell to chest height.

Let the kettlebell drop naturally, guiding it back between your legs as you hinge again—power comes from your hips, not your arms.

Kettlebell side lunge

Hold the kettlebell with both hands in front of your chest, gripping the handle securely.

Step out to the side, bending the stepping leg into a squat position while keeping the other leg straight.

Keep your chest lifted and shoulders pulled back as you lower yourself.

Push through the bent leg to return to your starting stance. This move strengthens lateral stability and mobility, key for runners navigating uneven terrain or sharp turns.

Stuck trying to figure out how heavy of a kettlebell you need? Experts suggest a weight range (for those new to kettlebell strength) of 12-16 kg (26-35 lbs) for men and 8-12 kg (18-26 lbs) for women, but everyone is unique. It’s important to adjust the size of your kettlebell so that you can maintain slow, controlled movements, focusing on form over weight or speed.

Do 10-12 repeats of each exercise and run through the circuit two or three times. As you get stronger, use heavier kettlebells or add reps.

by Keeley Milne

Login to leave a comment

How to plan your best running season ever

he trails are icy, the sun feels like it’s on vacation, and runners everywhere are dreaming of warm race days. Whether you’re targeting a marathon, a speedy 5K or an epic trail run, now is the perfect time to map out your race season. Smart planning isn’t just about picking events; it’s about setting yourself up for a successful year.

Start with the big picture

What’s your “A” race? The one that gets your heart pumping just thinking about it? Centre your season around this event, then add smaller races to sharpen your skills or just for fun. Prioritizing ensures you’re peaking at the right time and not burning out halfway through the year. Not into racing? Choose one big goal (distance, FKT or PB, whatever your jam is) with less intense adventures building up to it.

Build a base first

Winter is the time for base training—a steady diet of easy miles to build endurance and strengthen your aerobic engine. Building a strong base reduces injury risk and improves long-term performance. Hold off on hammering out intervals or tough tempo sessions until your body is ready to handle the load.

Sprinkle in strength and mobility

Don’t just run—build strength and flexibility, too. Research suggests that strength training can improve running economy by up to eight per cent, while mobility work helps prevent the dreaded winter stiffness. Bonus: adding these elements now gives you a head start when the mileage climbs later.

Plan your peaks and breaks (and focus on the basics)

Races are exciting, but too many can derail your season. Aim for two or three peak races and use others as training opportunities. Don’t forget to pencil in recovery weeks post-race. Rest is where the magic happens—your body adapts, repairs and gets stronger. Make sure you plan to fuel well throughout your season, including during rest periods, and make sleep a priority.

Adapt as you go

While a solid plan is crucial, life happens. Injury, weather or unexpected commitments might shift your season. Stay flexible and ready to adjust. A successful runner isn’t just fast; they’re adaptable. When running feels challenging and motivation is low, remind yourself that you’re playing the long (consistent) game, and the payoff is coming.

by Keeley Milne

Login to leave a comment

How to review your running year so you can improve in the months to come

THE END OF THE YEAR IS A GREAT TIME TO reflect on your running over the past 12 months – whether your aim has been fun, achieving parkrun PBs or preparing for a marathon.

A year-end review can help you spot trends, address setbacks and enhance your training for the upcoming year – whether that’s to boost performance or increase enjoyment. To do this, I encourage you to conduct a light performance analysis. It doesn’t require extensive data; instead, ask yourself key questions to start the new year with focus.

Audit yourself

Begin by reflecting on your goal-setting from a year ago. What were those goals? Are they still relevant? Perhaps you achieved several PBs or completed a couch to 5K programme and need a new challenge. Alternatively, you might need to scale back this year if your previous goals were unattainable. Remember, running should be enjoyable, and it’s normal to experience ups and downs.

Then take a closer look at your training, racing and lifestyle over the past year. Use data, along with the self-reflection questions to follow, to score yourself from one to five in the areas identified. This will guide your goal-setting and action plan for the year ahead.

1. Physical

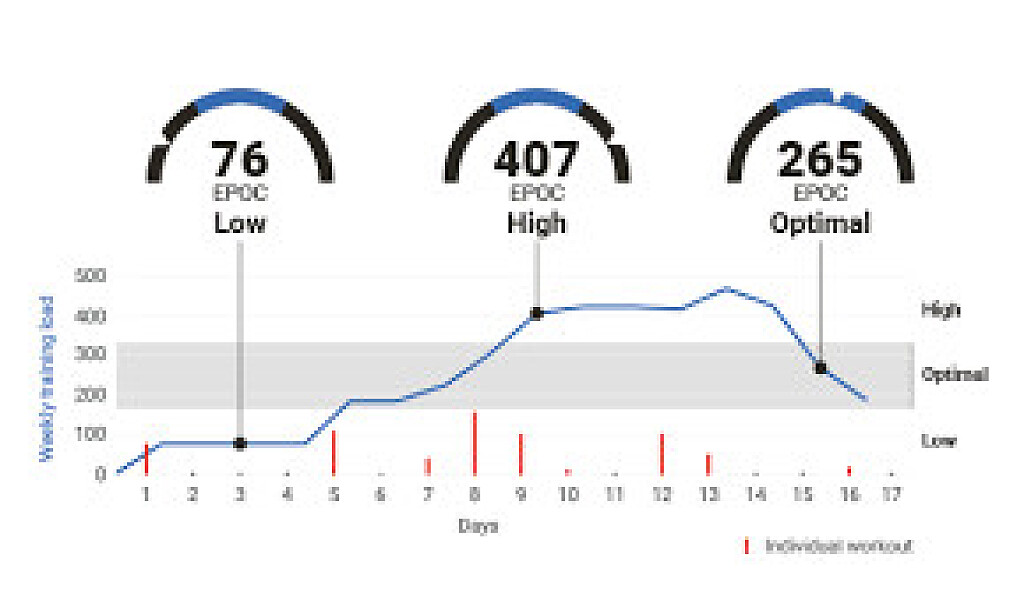

This covers your overall fitness, strength, endurance and injury prevention. If you’re more experienced, you might use data from apps such as Strava or Garmin Connect, or a detailed training log. This can include metrics such as mileage, heart rate or HRV measurements. For the performance-minded, consider lab testing such as lactate and VO2-max testing. If you’re less experienced, focus on how your rate of perceived exertion (RPE) might have changed in different training sessions and races as the year went on.

● Endurance Review your total volume over the year in distance or time. Were there gaps in consistency owing to injury, motivation or life events? Have you included longer runs regularly? Do you feel your heart rate or effort has reduced for similar paces, or are you able to sustain your pace for longer periods?

● Speed and power Analyse improvements in shorter races compared with longer ones. Use the RW race-time predictor to see if you align more closely on longer or shorter races, or if you are well balanced. Reflect on your training: did you include a mix of long runs, intervals, fartlek sessions, hill workouts, tempo runs and recovery runs? A well-rounded training plan leads to balanced improvement.

● Injury and strength Track how many injuries you’ve had, and their severity and causes. Has strength training supported your running? Use strength and flexibility tests such as knee-to-wall tests and sit-and-reach tests to benchmark yourself against norms for your age.

2. Planning and performance

This section looks at your approach to training plans and race performance.

● Race pace vs training pace Are you performing consistently in races compared with training? Do you feel you underperform or overperform in competitive situations?

● Variety Did you include races of different distances and on various surfaces throughout the year? Or did you stay in a comfort zone with your favourite or strongest type of race?

● Splits Evaluate how you pace yourself during races. Do you start too fast and fade, or do you

3. Mindset and wellbeing

Your mindset and emotional wellbeing play a significant role in your running performance, as well as in maintaining your motivation and consistency.

● Motivation and enjoyment Did you maintain enthusiasm for running or were there periods of low motivation? Identify factors that contributed to any highs and lows.

● Anxiety and pressure Did you regularly feel stressed or anxious about your running or performance? Consider your goal-setting and whether you have the right balance between process and outcome focus.

● Race nerves and focus Evaluate how you handled race-day pressure. Did you feel confident and focused or did nerves affect your performance? Assess your mental approach to tough runs and races – did you stay positive and push through challenging moments? Did you explore any mental techniques such as positive self-talk or mantras for key moments in races?

● Consistency and commitment Look at how disciplined you were with your training. Did you skip runs or stay consistent? What external factors affected your behaviour and how well did you handle those disruptions?

4. Recovery

You can follow the perfect plan with a good mix of training, but if you don’t recover, your fitness gains will be limited and you’re more likely to pick up injuries. Various pieces of data can help you monitor recovery, such as sleep tracking, heart-rate variability and the ‘recovery’ metrics from most GPS watches. Often, however, you’ll know if improvements are needed by answering some key questions:

● Sleep and rest Assess how well you prioritised rest, including sleep quality and duration. Poor recovery can lead to fatigue, injury and decreased performance, so reflect on how (or if) you balanced your hard training with adequate rest.

● Nutrition and hydration Did you fuel properly before during and after runs? Did you hydrate adequately, especially during long runs and races? Have you noticed patterns between nutrition and performance? Did you effectively plan and practise your race-day nutrition?

● Health and vitality Did you frequently catch colds or infections? In the run-up to key races, did you keep doing the simple things, such as using hand gel and taking any supplements you might need?

● Injury recovery Did you give yourself enough time to heal, follow rehab exercises and ease back

Write these down as a simple action plan with up to five priorities. Create objectives that are realistic and motivating, balancing short-term achievements – such as improving your pace or increasing weekly volume – with long-term ambitions, such as completing a marathon or getting a personal best.

Lastly, remember that running isn’t just about performance. Think about how to add enjoyment to your running, such as participating in races of different distances or on various surfaces. Consider joining a club or training group to maximise the social and mental health benefits of running.

Combining all of these lessons will help you get more from your running in 2025, whatever your goal may be. Good luck!

Login to leave a comment

Three tips for runners making a comeback

Pressed pause on training for a period? Here's how to make your return to running pain and problem-free.

Every runner faces a return to the sport at some point, whether it’s after months or even years away. Rebuilding your strength and fitness can be a fulfilling part of the process, but it’s crucial to do it thoughtfully—and we have some tips to help you stay on track. Whether it was an injury, a major life change or an unplanned extended break that kept you sidelined, now is the time to focus on moving forward.

1.- Leave your past behind

One of the biggest challenges when returning to running is resisting the urge to compare your current abilities to your past performance. It’s natural to feel frustrated when you think back to times when running felt easier, especially when every step now feels more difficult. But here’s the reality: you’re starting fresh from today. Dwelling on past achievements won’t get you anywhere; instead, focus on the progress you’re making as you move forward. Accept where you are right now and take pride in rebuilding your strength for the next phase of your running journey.

2.- Start slow and steady

Rebuilding is not the time for all-or-nothing thinking. Avoid the temptation to jump from zero runs to a packed training schedule—gradual increases are key to avoiding injury and burnout. While your return-to-running plan should be customized with your unique abilities and level of fitness in mind, it’s a good idea to start with two to three short runs per week. Sprinkle in walk breaks as needed, and keep it simple. Add new elements, like strength training or extra mileage, only after you’ve built consistency over several weeks.

3.- Forget pace and heart rate—for now

Press pause on worries about pace or heart rate data. Early in your return, the goal is to enjoy the act of running. Forget about pace, effort or numbers—instead focus on consistency and how running makes you feel. Keeping things comfortable and sustainable will help you rediscover what you love about the sport.

by Keeley Milne

Login to leave a comment

Keys to Achieving an Incredible Marathon Finish in Less Than 4 Hours

There is one achievement that everyone who takes part in running events can agree is the bar everyone looks to hit; completing it in under four hours.

There is a lot of preparation that goes into averaging 9:09 for 26.2 miles and it is not an easy feat. Full commitment is needed as it will take a lot, both physically and mentally, to get your body into a position to achieve that lofty goal.

People who have completed half-marathons should be aware that things don’t always translate the same to full marathons. Greg Laraia, a running coach in New York City at Motiv, says it is “a little bit more tricky.”

“You have to rely on nutrition, strength, your mental capacity, and a million other factors that running entails before you can say, ‘hey, I'm just going to go out and run the half marathon in two hours, and then do it again,’” said the coach.

Over at Runners World, Caitlin Carlson revealed what coaches and running professionals recommend to help break the 4-hour mark while running a marathon. For starters, it takes some self-reflection.

Going back and looking at previous races to see where you may have fallen short is key to reaching that next level. Is the necessary work, such as speed and strength training or mobility and recovery work, being put in?

If there are pieces missing, those are easy low hanging fruits where you can add those things in and you should notice a big difference,” Laraia says.

During preparation, it is imperative to put your body through different levels of effort. Sometimes while training, people will get stuck in a rut of wanting to challenge themselves a little bit when it comes to pacing, but not too much.

This is where professionals separate themselves from amateurs and casual runners. They have a distinct plan every week, knowing that mixing in easier days with tougher ones will get your body where it needs to be.

“I was in my early 20s for the first two and I really didn’t know what I was doing training and fueling-wise, thus, both races went terribly with horrible zonks at miles 18 to 20,” said Marie Gundersen Ishpujani, who broke the 4-hour mark at the 2011 New York City Marathon in her third attempt.

It is a good way for a person to learn just how much their body is capable of. The same can be achieved by pushing beyond 20 miles in training leading up to the marathon.

How can you complete a sub-4 hour marathon if you aren’t training those distances? But, this is where having a coach helps because novices to the sport could actually hurt themselves if they are not preparing correctly.

“If you’ve done three or four marathons and you’re trying to get this sub-four-hour marathon, your body’s probably pretty strong and pretty physically able to handle the 22 and 24 miles,” said Jimmy Anderson, who is 51 years old with 27 marathons under his belt; 25 of which he broke the 4-hour mark in.

Last but certainly not least, recovery needs to be optimized. There are many different things people can do to ensure their body gets back to as close to 100 percent healthy as possible and is ready to perform on marathon day.

Cold plunges are enjoyed by some, while foam rolling and stretching are incorporated by others.

by Kenneth Teape

Login to leave a comment

Seven Things To Do Before You Start Marathon Training

It’s essential to start preparing for a marathon 2-3 months before you begin your marathon-specific training. The more prep work you do before training starts, the less likely you are to get injured and the more likely you’ll be to reach your goals. Here are 7 things you need to do in the weeks before you start following your marathon training plan.

1.- Pick a training plan or hire a coach.

This is a no-brainer, but make sure you’re strategic in picking the right plan or coach. To ensure you get the plan you need, review your past training logs and make notes of what kind of weekly mileage you want to complete. Write out your goals for the race. Then start looking for the training plan that’s going to work best for you. If you only want to run four days a week, don’t choose a plan that asks you to run six days a week. Running isn’t your only goal in life, so find a training plan that works well with your lifestyle.

2.- Work on your weaknesses.

If you know you need to work on glute strength, commit to strength training three days per week now so that once marathon training starts, you’ll be strong enough to handle all the miles. If you know you need to work on your mental game, start working on it by reading books, listening to podcasts, etc. Even if you don’t have weak glutes or know of any muscle imbalances, you should still focus on doing strength training a minimum of two times per week.

3.- Be a little less structured with your workouts, but give each workout a purpose.

Marathon training can feel as though it goes on forever and ever. Now is the time to be a little less structured with your workouts. Give yourself the freedom to workout later in the day on the weekends. Don’t be afraid to miss a workout to see friends, or just cut yourself some slack when you need it. Make sure you’re doing the work you need to (base building and strength training), but don’t go crazy. Once marathon training officially starts, you’ll need to be on your ‘A game’ and giving yourself some time to breathe now will set you up for success.

4.- Build your running base.

Before you begin training, you’ll need to have completed 4-6 weeks of consistent running. The number of miles you’ll need to run per week to build your base depends on your goal for the marathon, your running history and what kind of mileage you’ll be doing during the first month of your training plan.

5.- Have fun with your workouts.

This is a time when you can try out all the fun fitness classes in your neighborhood without having to worry about how they will interfere with marathon training. Once marathon training starts, there won’t be much time for exploring new workouts.

6.- Improve your running form.

Now is the time to focus on stride rate, stride length, foot strike, arm swing, etc. Small changes made over time can make you a more efficient runner.

7.- If you had any nagging injuries you haven’t taken care of, see a doctor or physical therapist.

Don’t wait for a small twinge to become a real injury.

by Jess Underhill

Login to leave a comment

From Beginner to Advanced Runners: How Often Should You Be Lacing Up? Experts Break Down What Factors to Consider

Use these tips for figuring out your ideal running frequency.

Just like there’s no “best” running shoe for everyone, or training plan, or energy gel, there’s no ideal running frequency for all runners. Even though many runners ask how often they should run, the days per week you lace up depends on factors that vary from one individual to the next. Even when you do settle into a pattern that works for you, your approach may need to shift as aspects of your training (and life, in general) change.

However, there are some general guidelines that can help new runners identify a healthy starting point for how often to run, as well as some guidance more experienced athletes can follow to decide if it’s time to dial up or scale back on their weekly runs. Runner’s World spoke with Alison Marie Helms, Ph.D., UESCA-certified running coach and founder of Women’s Running Academy, and Raj Hathiramani, certified running coach at Mile High Run Club in New York City, to get their expert advice. Here’s what you need to know.

Factors to Consider When Determining How Often You Should Run

Before designing a personalized training schedule, any qualified coach will take the time to understand their runner, both as an athlete and a fully-realized person with a life outside of running. So, whether you’re working with a pro or developing a plan on your own, consider the following factors when deciding how often you should run:

Goals

Determining your running goals is a good place to start figuring out how often to run. Do you want to set a new half-marathon PR? Finish your first ultra? Improve your cardiovascular health? What you hope to accomplish can help you determine your overall running volume, which informs how many times a week you should ideally run.

“People who have more specific time or distance goals may be running more frequently per week, and those who have more fitness or wellbeing-oriented goals might be running less frequently,” Hathiramani says. Among runners with performance-related goals, those who race longer distances may need to run more often than those with their sights set on shorter distances.

Experience

Two runners can have the same goal, like finishing their first marathon, for example. But if one marathon hopeful is brand new to running and the other has multiple 5K, 10K, and half-marathon races under their belt, their training frequency should look different.

“It’s never a good idea to do too much too soon,” Hathiramani says. He recommends new runners gradually ease into running, even using a walk/run approach, and avoid running on back-to-back days. “This is

Running one to two days per week is also ideal for those just getting into running. You can do a walk/run workout or go for a quick, slow jog down the block. The goal is consistency if you’re looking to jumpstart a new workout habit.

Three Days a Week

For many runners, lacing up three days a week strikes a balance between feeling substantial and attainable. You can get in a variety of runs and still have plenty of time for cross-training and recovery. For example, you may plan a long run for the weekend, an interval on Tuesday, and a tempo run on Thursday. That still leaves four days for rest and activities like strength training and mobility work.

This frequency may be ideal for someone training for a short distance, like a 5K, but it may not be adequate for all runners with long-distance racing goals, like a half marathon or longer, Hathiramani says.

Four to Five Days a Week

For Hathiramani’s client base, which is primarily half marathon and marathon runners, four to five days a week is the “sweet spot,” as it allows runners to vary their training and accumulate the volume they

→At first, keep your volume the same

For example, if you’re used to running 12 miles over the course of three days, add a day of running but keep your total weekly mileage at 12. Helms recommends doing this for a week or two before adding additional miles to your runs.

→Increase overall volume gradually

The general rule of thumb is to increase your overall weekly mileage by no more than 10 to 15 percent. (However, if your current mileage is relatively low—like five to 10 miles per week—you’re probably safe to increase by up to 30 percent, Helms says.)

→Take “step-back” weeks

Every few weeks, reduce your mileage by a small percentage. For example, if you went from 20 to 22 miles in week one, then to 24 miles in week two, and 27 miles in week three, drop back down to 20 miles in week four. “You’re still running, but you’re letting your body recover, maybe taking an extra rest day or reducing your average mileage, and letting it sort of realize some of the endurance and aerobic capacity gains you’re making,” Hathiramani says.

→Resist the urge to “catch up”

Adjusting to a more demanding

“Consistency is a really important way to instill discipline and motivation in your training to help you achieve your goal,” Hathiramani says. “That being said, there are things out of your control that may make it hard for you to be consistent, and that’s okay.”

Login to leave a comment

Running More Relaxed Can Improve Your Performance—Here’s How to Do It

Experts share their best tips to help you stay calm, cool, and collected while you’re out on the run.

It’s possible to run fast without clenching every muscle in your body. Just look at some of the pros like Cole Hocker, Nikki Hiltz, or Sarah Vaughn who seem to clock seriously fast times while making it look like an easy walk (er, run) in the park.

These pros and many others have mastered running with slack shoulders, fluid arms, and a powerful stride, all while seeming light on their feet. It’s the art of running relaxed—and it can actually help your performance.

Experts encourage you to run relaxed on easy and long run days—those workouts where you’re meant to go at an easy effort. But running relaxed is a tool you can use to your benefit for any type of run.

“It is important to remain relaxed in terms of not recruiting muscles that don’t need to be recruited, because that can increase the energy that you’re using for the run,” Heather Milton, M.S., exercise physiologist at NYU Langone Health’s Sports Performance Center tells Runner’s World. This can cause you to fatigue and slow down more quickly, she explains.

For example, lifting your shoulders up toward your ears or tensing up your face while you run requires more energy than letting your upper body and jaw hang a little looser. This could also affect form: If you’re running tensely upright, without a forward lean, you’re less able to activate the glutes, and your knees take on more force, potentially leading to knee pain, Milton explains.

To help you perfect the art of running relaxed and get the most out of your workouts, we tapped experts for their best tips.

Quick Forms Tips to Help You Relax on the Run

When it comes to running relaxed, maintaining the proper running form is key and will help improve your efficiency. Although not everyone’s stride is the same, keep these cues in mind while you’re out clocking miles:

➥Keep Your Upper Half Loose

Run

➥Lean Forward

“What we want to see is that there is a slight angle of your running, so from your ankle through your hips, through your shoulders, you’re progressively closer to your target, looking forward,” Milton says. You can imagine your body in a slight diagonal line as you run forward. This will enable a greater amount of lower leg activation, better push off, and better hip extension. It can also reduce your risk for injury and improve your performance, she explains.

➥Make Your Center Stable

“The core should be a stable column on which we run and can have more effective push off,” says Milton. This is why it's important to build core strength, she adds.

➥Drive Forward With Your Feet

In terms of your feet, Milton recommends you focus on swiping the ground behind you while you run.

8 Tips to Help You Stay Relaxed on the Run

Beyond fixing your form, here are a few things you can try leading up to race day and during your run to help you maintain that relaxed run posture. Rather than implementing all of these tips at once, try out a few of them to see which ones work best for you so you stay calm, cool, and collected on the road.

1. Work on Your Mobility

Limited range of motion can hinder your ability to run more relaxed.

“It really takes access to every joint movement in the body,”John Goldthorp, a certified personal trainer and run coach tells Runner’s World. If you can’t freely move your joints, then you can’t make the necessary movements that you need to help you run really well, he explains.

This is why he recommends working through different planes of motion (front to back, side to side, and rotational) before you run and even on non-running days.

To do that, practice moves like standing cat cow, side bends, and rib cage and pelvic rotations, all of which work the spine and upper body through the different movement patterns. Also, work on pronation

Working with a physical therapist or functional mobility specialist can also help you address these areas so you can improve your range of motion and run more fluidly.

2. Address Any Pain Areas

As you can imagine, or might have even experienced, running with pain can hinder your ability to relax. This is why Milton recommends strength training as a way to address some of your pain points.

For example, address shin splints by strengthening your feet, ankles, calves, and hips. Target pain associated with runner’s knee by strengthening your hips and inner quads.

“Strength training is a great way to make sure that your body is ready for the run,” says Milton.

3. Add Strides to Your Calendar

The key is to practice running short bouts at different paces like your easy, marathon, half marathon, 10K, 5K, and mile pace while relaxed, says Goldthorp. He recommends you start by introducing strides toward the middle or second half of an easy run.

“Like any new stimulus, you’ll want to introduce things gradually both in terms of how many repetitions you do and how fast you’re running them,” he explains. This may mean running four reps of 20-second strides with

Lastly, take a few minutes to gradually progress from a slow walk to a brisk walk and then to a light jog, says Goldthorp. “I always think to myself, I’m not really going to hit my ‘training pace’ for probably about 15 minutes,” so don’t rush it, he says.

This will not only help you ease into the run better, but it can help you find your rhythm more easily and allows you to remain relaxed as you adjust from not running to running slowly to running at a quick clip. Just remember to keep that loose feeling through each progression.

5. Complete a Quick Self Scan

Before you head out for a run, Goldthorp recommends you take note of where you typically hold tension in your body. For example, do you clench your jaw or shrug your shoulders?

“Scan your body. If you notice tension, see if you can let it go, see if you can soften that area,” he says. You can also visualize that area of your body flowing like water.

Then, on the run, check for specific body cues, says Milton. For example, make sure you’re bringing your arms back directly behind you and then letting

If you’re running with a watch on race day “check in and check your splits and make sure that you’re not running too fast, which can create a lot of undue tension,” Milton adds. If you are going too fast, she recommends coming back to your breathing and making sure it feels appropriate for your target pace.

8. Don’t Be Afraid to Give It Your All

There might be times, especially at the end of a workout or race, where we’re willing to get ugly and push past our comfort zone to hit your goal time or beat an opponent, says Accetta. In these moments, it’s acceptable to push yourself even if that means tensing up a bit.

The key is recognizing when to kick it into high gear, like when you’re sprinting to the finish. You don’t want to waste all your energy too soon, Accetta explains. Even when you do pick it up, remember some of those form tips of keeping your upper body loose and your jaw slack so your legs have the energy they need to turnover fast.

Login to leave a comment

Does Yoga Count as Strength Training?

If you’ve ever been sore after a yoga class or felt your muscles aching while holding Warrior 2, you’re familiar with the strengthening benefits of yoga. Although many of us associate yoga with primarily increasing flexibility and calming one’s chaotic thoughts, yoga does build muscle. But how effective is it? Does yoga count as strength training?

Does Yoga Count as Strength Training?

The short answer is, it depends.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), adults should accumulate a minimum of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise per week plus at least two total-body strength training workouts per week. Strength training increases muscular strength and muscular endurance, which are two of the five components of health-related fitness.

Strength training, also known as resistance training, involves exercises that load your muscles. This not only builds muscle but increases bone density and helps stabilize joints to prevent injuries. Lifting weights or using resistance bands are two common options for strength training.

But they’re not necessarily the only options. Bodyweight training, in which you use your own weight as resistance, is another type of strength training. Some styles of yoga can be considered bodyweight training and can be ideal for anyone who either doesn’t have access to a gym or doesn’t care for or have time for traditional strength training exercises.

That said, there are two factors that largely influence the response to does yoga count as strength training.

1. Type of Yoga

Yoga is an extremely diverse practice with many different styles and ways to practice. Certain types of yoga and poses can strengthen muscles and potentially even build muscle.

2. Your Fitness Level

The other factor that plays a significant role in whether yoga functions as strengthening is your fitness level. Ultimately, it is more difficult to build muscle with yoga than it is with traditional resistance training using external implements such as dumbbells, barbells, kettlebells, resistance bands

In order to build muscle, you need to overload your muscles’ current capacity enough to induce some amount of damage to your muscle fibers. This microscopic damage triggers a process known as muscle protein synthesis, which repairs and rebuilds muscle and helps make your muscles stronger over time.

While it is possible to strengthen your muscles and potentially build muscle exclusively through bodyweight exercises, most people reach a plateau of body strength where some external resistance is necessary to continue strengthening and increasing muscle mass. In general, practicing yoga is not as effective as lifting weights.

However, anything that challenges you is strengthening your muscles. For example, chair yoga can be an efficient strength-training workout. Don’t compare yourself to others and meet your body where you’re at. Also, never push your body beyond your current fitness level or to the point of pain or extreme discomfort.

What Are the Best Types of Yoga for Strength Training?

Beginners often assume that classes for more experienced practitioners are inherently more difficult and better for strengthening than beginner classes. This isn’t necessarily true. These classes are often faster-paced and focus more on transitions between poses and less instruction from the teacher. This can increase the risk of injury for those who are still mastering the foundations and learning basic yoga poses. It can also shift the emphasis to the space in between the poses rather than the strengthening practice of holding the poses for a length of time.

It’s the style of yoga that plays a more important role in whether or not you will be strengthening your muscles or focusing on other aspects of fitness and health in your yoga class.

Some of the best types of yoga for muscle strength include:

Vinyasa yoga

Power yoga

Login to leave a comment

Four essential strength moves for runners

These simple exercises add only 20 minutes to your training regime, and are recommended by a coach and physiotherapist.

Let’s face it: runners love to run. But if you’re not adding strength training to your weekly plan, you’re leaving some serious performance gains on the table. We’re here to help you get started, with four exercises recommended by an expert.

Richelle Weeks, a certified running coach and physiotherapist at Sportscience Ottawa, says that every runner should consider adding a few essential exercises to their routine. “Any runner who is serious about their running should be strength training regularly,” Weeks recently said to Fit & Well. “When done properly it can improve performance by five per cent because it improves running economy. It can also help reduce common overuse running injuries, especially in the 40-plus runner.”

Finding the time for strength training isn’t always easy—runners are already fitting training hours into busy lives. But even a short, 20-minute workout once or twice a week can make a huge difference. Weeks has shared a straightforward routine on Instagram that you can do at home, targeting the key muscle groups runners rely on most: calves, quads, glutes, hamstrings and core.

So, what should you add to your lineup? Here’s a quick look at Weeks’ recommended moves. For all of these, she suggests starting with three sets of eight reps; once you gain strength, she suggests using heavier weights rather than adding more reps.

1.- Side lunge

This side-to-side movement builds hip stability and strengthens the glutes, quads and hamstrings, helping with lateral stability for better form and injury prevention.

How to do it: Step out to the side, bending your knee and keeping your other leg straight. Sink into a lunge while keeping your chest lifted, then push back up to standing. Repeat on both sides.

2.- Glute bridge march

This move activates the glutes and core, providing stability to your hips and helping reduce low back strain, a common problem area for runners.

How to do it: Lie on your back with knees bent, feet hip-width apart. Lift your hips to create a straight line from your shoulders to your knees. March each knee toward your chest while keeping your hips stable.

3.- Side plank rotation

The side plank rotation fires up the core and engages the obliques, improving your balance and trunk control—essential for strong, stable strides.

How to do it: Begin in a side plank, with your elbow beneath your shoulder and your feet stacked. Rotate your torso, reaching your top hand down under your torso, then return to the starting position. Repeat on both sides.

4.- Calf raise

Strong calves are crucial for a powerful push-off. Calf raises build strength and resilience in this often-overlooked muscle group, reducing the risk of Achilles and other lower-leg injuries.

How to do it: Stand with your feet hip-width apart, slowly rise onto your toes, and lower back down with control. Add weights or stand on a step to increase the challenge.

For those with extra time, Weeks suggests adding an upper-body exercise or two. “It can help maintain an upright posture when fatigued during a race, like at the end of a marathon. It can also help make arm swing efficient,” she says. Options include a push exercise like push-ups, shoulder presses or bench presses, and a pull exercise like pull-ups, rows or back flies.

Start small, but make strength training part of your weekly routine to see noticeable gains in performance and injury prevention. As Weeks emphasizes, these moves are quick, accessible, and just might be the key to your next PB.

by Marley Dickinson

Login to leave a comment

Are muscle imbalances slowing you down?

When you lace up for your daily run, chances are you’re thinking about mileage and endurance, not the balance of strength in your muscles. However, ignoring muscle imbalances—especially between the front and back of your body—can lead to long-term pain and injury. Here’s how to recognize and prevent this sneaky problem.

What are muscle imbalances?

Muscle imbalances occur when opposing muscles around a joint aren’t equally strong or flexible. While everyone has some degree of imbalance, it becomes a concern when it starts affecting movement or causing pain. Runners are particularly prone to imbalances between their quads (the muscles in the front of the thighs) and their glutes or hamstrings (the muscles in the back). This can lead to tight hip flexors, weak glutes and poor posture, ultimately resulting in knee, hip or lower back pain. A recent article in The New York Times highlighted how focusing on strengthening underworked muscles is key to preventing discomfort caused by repetitive strain.

Ann Crowe, a physical therapist based in Clayton, Mo., works primarily with runners and cyclists, and emphasizes the importance of strengthening all muscle groups—not just those directly used in running. She points out that many athletes focus solely on cardiovascular fitness and neglecting strength training, which is essential for stabilizing muscles during movement.

The impact of everyday activities