Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #Shalane Flanagan

Today's Running News

Gate River Run 2025 Returns to PRRO Circuit with Elite Competition and a Scenic Challenge

The Gate River Run is back for its 48th edition on Saturday, March 1, 2025, in Jacksonville, Florida, bringing together elite athletes, competitive runners, and thousands of participants for one of the most exciting road races in the country.

This year marks a historic moment as the race rejoins the Professional Road Running Organization (PRRO) Circuit for the first time since 1993, elevating its status on the international stage. With a challenging 15K course, a prize purse of $62,000, and the famous climb over the Hart Bridge, the Gate River Run is set to deliver another thrilling race in one of Florida’s most vibrant cities.

The event will once again serve as the USA 15K Championship, a title it has held since 1994, ensuring a strong field of American contenders alongside international competition. More than 18,000 runners are expected to take part, making this the largest 15K race in the country.

Elite field and prize structure

The 2025 Gate River Run is expected to feature a deep and competitive field, with elite athletes competing for national titles and significant prize money. As part of the PRRO Circuit, the race will draw top talent from both the U.S. and abroad.

The total prize purse for 2025 is $62,000, distributed as follows:

Open division: $20,500 each for men and women, awarded to the top ten finishers

American Cup: $8,000 each for the top five U.S. male and female athletes

Equalizer bonus: $5,000 to the first athlete, male or female, to cross the finish line

Additional bonuses are available for record-breaking performances:

World record: $10,000

American record: $5,000

Course record: $3,000

The current course records belong to Todd Williams, who ran 42:22 in 1995, and Shalane Flanagan, who set the women’s mark of 47:00 in 2014.

Course details

The 15K (9.3-mile) course showcases some of Jacksonville’s most scenic and historic neighborhoods, including Downtown, San Marco, and St. Nicholas, with sweeping views of the St. Johns River. The early miles feature fast and flat stretches, allowing runners to settle into their rhythm before tackling the city’s signature challenge—the Hart Bridge.

Known as the “Green Monster,” the Hart Bridge presents a daunting climb in the final two miles, rising 141 feet above the river. The demanding half-mile ascent has tested even the strongest runners, making it one of the most memorable features of the race. After cresting the bridge, runners experience a thrilling downhill stretch toward the finish line at Metropolitan Park.

Event schedule

Elite women start at 7:55 am

Elite men and wave one start at 8:00 am

Subsequent waves begin shortly after, accommodating runners of varying paces

Jacksonville’s running heritage

Jacksonville has long been a city that embraces running. Home to one of the largest urban park systems in the U.S., its scenic riverfront, historic districts, and expansive green spaces have made it a favorite for runners of all levels. The Gate River Run, founded in 1978 by JTC Running, has played a major role in shaping the city’s running culture.

Over the years, the race has hosted some of the biggest names in distance running, including Olympic medalists Deena Kastor, Shalane Flanagan, and Meb Keflezighi. With its return to the PRRO Circuit, the event reaffirms its place as one of the premier road races in the country.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Gate River Run

The Gate River Run (GRR) was first held in 1978, formerly known as the Jacksonville River Run, is an annual 15-kilometer road running event in Jacksonville, Fla., that attracts both competitive and recreational runners -- in huge numbers! One of the great running events in America, it has been the US National 15K Championship since 1994, and in 2007...

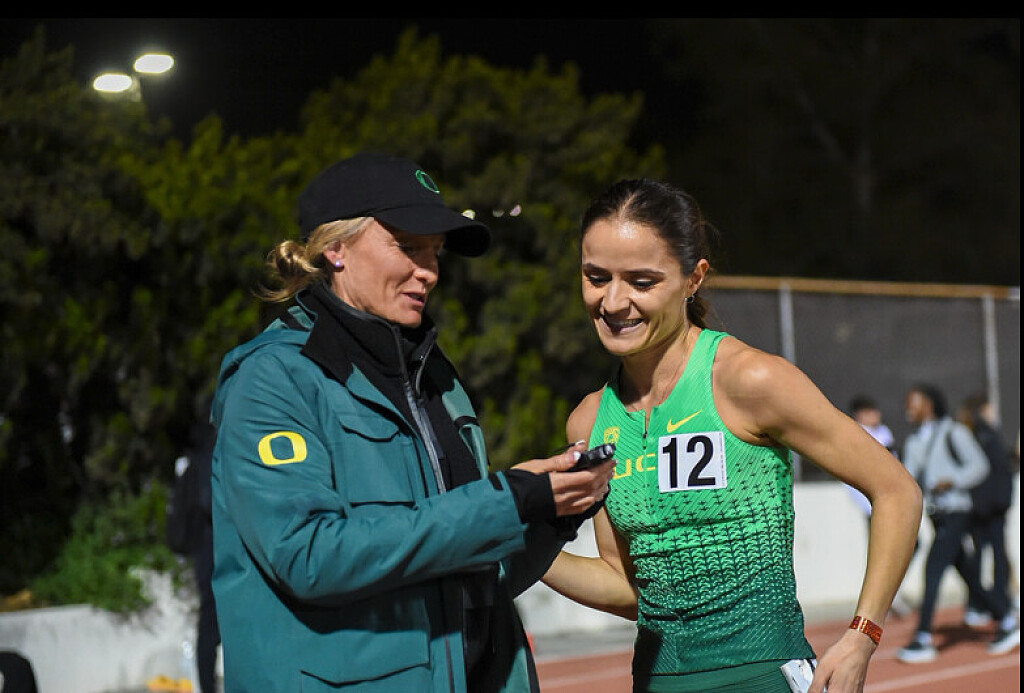

more...Shalane Flanagan Finds Her Sweet Spot With College Coaching

She’s juggling the University of Oregon women’s distance runners, the Bowerman Track Club, and a young family.

Before she gives a new workout to her University of Oregon athletes, Shalane Flanagan will try it out herself.

During cross-country season, it was a 5-mile tempo loop. Was it too hilly? Were the turns too sharp? In April, she was “messing around at the track one day,” as she described it, when she attempted a descending ladder of mile-800-600-400 at 10K-5K-3K-1500 pace with a short jog recovery.

“Yeah, that’s really hard,” she thought to herself. “But I think if they did that twice, it would make 10K runners feel really prepared.” Her goal with the experimentation is to make sure a workout is “feasible, but not outlandish” before her runners do it.

Few distance coaches in the NCAA are doing what she does, testing hard workouts, although Flanagan, 42, is quick to say that she does not hit the same splits her athletes do. Her boss, Oregon head coach Jerry Schumacher, is not so sure. “I see her out running every now and then, holy cow, she’s flying,” he told Runner’s World, quipping that it’s too bad she’s used up her NCAA eligibility.

Fewer still have the credentials that Flanagan, a four-time Olympian, has. She was the Olympic silver medalist in the 10,000 meters in 2008 and the 2017 New York City Marathon champion. Since she retired in 2019, she stayed on as an assistant coach with the Bowerman Track Club, a Nike pro group also coached by Schumacher that she ran for in the latter stages of her career.

That experience gives her credibility with her runners. So when she tells her athletes that they’re ready to handle a workout or race a certain time, they believe her.

“I don’t like to refer back to myself a lot,” she said in an interview at her home, a large 1920s colonial about a half mile from Hayward Field. “But I’ll say, ‘Hey, I’ve had experience with this,’ and I think they know, when I’m giving them advice, it’s not a hypothetical. I’m not projecting or guessing.

“They know it’s coming from a genuine place, because I’ve lived it,” she added. “I think that can be helpful with their confidence.”

Multiple full-time jobs

Flanagan had been living near Portland, Oregon, with her husband, Steve Edwards, and toddler son, Jack, when Schumacher was hired as the head coach of Oregon in Eugene, two hours south, in the summer of 2022. He brought Flanagan on as an assistant coach, while both kept their responsibilities with the Bowerman team, which also moved to Eugene. It was a lot.

Those early days for Flanagan—getting to know 11 female distance runners on the team, developing their training, learning the ever-changing NCAA rules, recruiting—were exhausting. And that was before they adopted a second child, Grace, as a newborn, in January 2023. They had only hours notice before Grace’s arrival.

Flanagan gets childcare help for Jack, almost 4, and Grace, 1, from a variety of babysitters and her parents. Her father, Steve Flanagan, and her stepmother visit often. One time, Flanagan had some team members’ parents visiting, and she turned around to see her dad showing them her Olympic medal. “What are you doing?” she asked him. “Put that away, that’s embarrassing.”

About three months in, when Schumacher asked her how she was handling the workload, she told him she was overwhelmed. “I’m really tired,” she said, “but this is the most fun I’ve ever had professionally. Like, I really love this job. I really love college athletics.”

Schumacher gave her full autonomy to write the training for Oregon’s women. And unlike with the Bowerman program, which former runners have said did not have much variation depending on the athlete, Flanagan has personalized training at Oregon for each individual. Some athletes on her team run as little as 25 miles per week, others go as high as 75.

One cornerstone of her training is the weekly long run on Sundays, and most weeks it has some structure to it, with tempo portions or a fartlek. For most of the team, the distance ranges from 12 to 16 miles, depending on the person.

When she first arrived in Eugene, she wrote the training with ranges in mileage. Easy days, for instance, she’d have her runners do 6 to 8 miles, depending on how they felt. They didn’t like that. They wanted an exact number. Getting them to trust themselves, listen to their bodies, and know the difference between muscle soreness and a potential injury has been one of her biggest challenges.

“I have tried to instill in them that they need to learn their body,” she said. “Like, I’m not in their body—they need to take stock and learn how to read their body. It’s one of the greatest skills and assets I felt like I had [as a runner].”

Flanagan tries to run with various groups at least one day per week on their easy runs. “It’s fun to run with the coach,” said Klaudia Kazimierska, who was fourth in the 1500 meters at the NCAA outdoor championships in 2023. “She’s a great inspiration, and she was a great athlete. She tries to give us a lot of information—and she tries to show us that running is so fun.”

Flanagan finds it easier to learn about her athletes when they’re on the run instead of sitting down and looking at one another. She’ll pick up vibes about what’s going on with them and urge them to limit their social media, especially when it comes to training.

“They devour information about what everyone else is doing,” Flanagan said. “I tell them, ‘You’ve got to be careful what goes in your head.’ I don’t follow any other kids from any other programs or any other coaches. I think it would undermine my intuitiveness. I don’t want to know.”

At the same time, she finds her college athletes much more professional than she was as an undergraduate at the University of North Carolina, when she worked hard, but also focused on her classes and other parts of college life. Not these women. “If anything, I’m like, ‘Yo, you’ve got to chill out. You’ve got to dial this back,’” she said. “They’re really into their running and I don’t have to nudge or push. They are really on top of it. It’s kind of freaky.”

Mixed results

Flanagan’s approach has yielded immediate results, but some athletes have had setbacks as well.

Last year, four qualified for the NCAA outdoor championships in the distance events, from 800 to 10,000, including three who made the final in the 1500.

Early in the 2024 outdoor season, the Ducks seemed destined to have more in this year’s championship meet, which started June 5 at Hayward Field.

At the end of March, Maddy Elmore set a school record in the 5,000 meters, running 15:15.79. Two weeks later, Şilan Ayyildiz, a transfer from the University of South Carolina who had been at Oregon for only about three months, ran 15:15.84.

Ayyildiz lines up at the NCAA championships this weekend, along with Kazimierska and Mia Barnett in the 1500 meters, and a freshman steeplechaser, Katie Clute. But Elmore sustained an injury to her soleus in late April and was unable to run in the qualifying meet for NCAAs. Flanagan’s total is again four athletes at NCAAs. She had hoped to have at least one qualifier in every event distance event.

In her short tenure, she has seen how college students have to grapple with stress, classes, finals, and in some cases, anxiety. They pick up illnesses. The big result doesn’t always come at the right time—if it comes at all. “I see these things and I see how they move and handle the work, but sometimes in this season, I may not get the performance in a race,” she said. The coach is still learning.

A busy summer

Elmore might be back in time to race the Olympic Trials, which begin on June 21. Kazimierska will go home to Poland and hope to make the Polish Olympic team in the 1500 meters. As soon as the season is over, Flanagan will turn more of her attention to the Bowerman team, which currently has three women: Karissa Schweizer, Christina Aragon, and Kaylee Mitchell. The club had several departures from the men’s and women’s side after Shelby Houlihan’s doping ban in 2021 and the move to Eugene in 2022.

It’s been difficult for Flanagan to watch the turnover, especially as some of the athletes she’d trained alongside for years, like steeplechaser Courtney Frerichs, left. They’re friends.

At the same time, Flanagan understands it. She changed coaches a few times herself during her career. It would be selfish for her to expect them to stay.

“Especially at the end of a career, to eke out those last big performances, sometimes you need a change of scenery,” she said. “I actually think it’s healthy to get different training, a different stimulus. Sometimes you can fall into this monotony and it feels stale especially if you’ve been doing it for a while.”

When she heard from athletes that they were thinking of leaving Bowerman, Flanagan jumped in with suggestions.

Her coaching brain took over to help.

“At the end of the day, I want them to be successful and happy,” she said. “So when they expressed maybe needing a change, I’m like, ‘Okay, let’s work through this. What are your plans? I don’t want you to leave and aimlessly not have a plan. What does that look like, what do you want to do?’ It’s a natural evolution.”

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

U.S. Olympic Marathoners Will Race the Bolder Boulder 10K as a Pre-Paris Tune-Up

Conner Mantz, Clayton Young, and Leonard Korir will run in the International Pro Team Challenge on May 27.

Memorial Day is always an exceptional celebration for runners in Boulder, Colorado, but this year, it will have some extra special Olympic flair.

On Monday, May 27, more than 40,000 runners will run through the city that’s known for the iconic Flatirons rock formations, the Pearl Street pedestrian mall, and an exceptionally active population in the annual Bolder Boulder 10K. Now in its 44th year, it’s been one of the top road running races in the U.S. since its inception, and this year will serve as one of the final tune-ups for the men’s U.S. Olympic marathon squad before racing in the Paris Olympics later this summer.

Conner Mantz, Clayton Young, and Leonard Korir, the top three finishers in the 2024 U.S. Olympic Trials who will be racing the marathon in the Paris Olympics on August 10, will be competing as Team USA Red in the Bolder Boulder’s International Pro Team Challenge that follows the citizen’s races. (Korir is expected to officially be named to the U.S. team in early May based on final pre-Olympic international rankings.)

The pro race, which has a prize purse of $83,700 before potential bonuses, is one of the things that makes the Bolder Boulder so unique. After all the runners in 98 citizen waves have completed the race, professional men’s and women’s international teams from more than a dozen countries compete on the same course for team and individual titles. The races feature a staggered start, with women beginning 15 minutes before the men so the winners of each race will finish about 10 minutes apart inside the University of Colorado’s Folsom Field football stadium.

The finishing moments are among the thrilling spectacles in American running. By that point, the stadium is filled with a near-capacity crowd of roaring runners, family, and friends who have been watching the action play out on the massive video screens.

“The finish in the full stadium is like nothing else in the sport,” says Mantz, 27, who won the men’s race last year in 29:08 with a thrilling late-race surge to pass Kenya’s Alex Masai in the final 200 meters before the finish. “It was pretty electric. It took away all the pain you’re feeling mid-race. I was like, ‘Just race as hard as you can.’”

Team USA Red will have plenty of competition, from Team USA White, the secondary American team of Jared Ward, Futsum Zienasellassie, and Sam Chelanga, as well as teams from Kenya, Ethiopia, Mexico, and Rwanda. Teams are scored like a cross country race, with points awarded on the basis of finishing place, which means the team with the lowest combined score for all three runners is the winner. Ties are decided by the positions of the third-place finishers.

The women’s Team USA Red team will be led by defending champion Emily Durgin, along with Sara Hall and Boulder native Nell Rojas. Durgin finished ninth at the U.S. Olympic Trials in February and won the USATF 10 Mile Championships on April 7 in Washington D.C. At last year’s Bolder Boulder, she stormed to victory in 33:24, winning by 24 seconds over Kenya’s Daisy Kimeli.

Hall placed fifth in the U.S. Olympic Trials Marathon on February 3 in a U.S. master’s record (2:26:06) and 15th in the Boston Marathon on April 15. The women’s Team USA White roster will be composed of an all-University of Colorado alumnae squad—Makena Morley, Sara Vaughn, and Carrie Verdon.

“I can’t wait to be back in Boulder for the best day of the year,” says Durgin, 29, who will compete in the U.S. Olympic Trials 10,000 meters on the track in late June with the hopes of making the U.S. Olympic team. “Competing with Nell and Sara will make the experience even better.”

The women’s U.S. Olympic marathon team of Fionna O’Keefe, Emily Sisson, and Dakotah Lindwurm were invited to race in the Bolder Boulder but each runner declined, citing scheduling timing conflicts or a disinterest in racing at Boulder’s lofty altitude (5,430 feet). All of the runners who are racing for the U.S. teams in Boulder live at 4,500 feet or higher.

An Olympic Legacy

Boulder is known as one of the top running meccas in the U.S., in part because elite-level American and international runners have made it their training base since Olympic gold medalist Frank Shorter arrived in the early 1970s. Emma Coburn, Jenny Simpson, Yared Nuguse, Joe Klecker, Jake Riley, Hellen Obiri, and Edna Kiplagat are among the many top-level runners who are currently training in Boulder. Shorter, the 1972 marathon gold medalist, was a co-founder of Bolder Boulder 10K in 1979, and helped it grow into one of the country’s largest races.

Since then, numerous U.S. Olympians have raced in the Bolder Boulder, including Deena Kastor (a three-time women’s champion), Aliphine Tuliamuk (the 2022 women’s winner), Alan Culpepper, Elva Dyer, Ryan Hall, Abdi Abdirahman, Jorge Torres, Shalane Flanagan, Amy Cragg, Magdalena Boulet, and Libby Hickman, as well as Korir (who won it in 2022), and Ward (who was fourth in 2022).

Thanks to Boulder’s robust running community and the prestige of the race, the Bolder Boulder has also always featured fast sub-elite runners competing in the early citizen waves. Yet, the race has also celebrated dedicated middle-of-the-pack runners, as well as the first-time runners and walkers in the later waves. It was one of the first races to have bands playing along the course (as well as belly dancers and other entertainers), runners dressed up in costumes, elite wheelchair races, and in recent years, it has been known for a mid-race slip-and-slide and unofficial bacon aid station.

For the past 25 years, the Bolder Boulder has organized a special Memorial Day tribute—one of the largest in the country—that honors military veterans and new cadets.

The U.S. men’s Olympic marathon team competing in this year’s Bolder Boulder will be a legacy moment for the race, says Bolder Boulder race director Cliff Bosley.

“Having the three men that will represent our country in the marathon at this summer’s Paris Olympic Games is something we are extremely proud of,” Bosley says. “All three ran here last year, and to have them back is just incredible for the race, the city of Boulder, and the sport of running.”

by Brian Metzler

Login to leave a comment

Paul Chelimo is set to make marathon debut at Olympic Trials

Paul Chelimo, an Olympic 5000m silver and bronze medalist, will make his marathon debut at the U.S. Olympic Trials on Feb. 3 in Orlando.

“Ever since I was a kid, I dreamed of running a marathon… The day has come- this is it!” was posted on his social media Friday.

Chelimo, 33, qualified for the marathon trials by running a 1:02:22 half marathon last April 2, safely quicker than the 1:03:00 minimum to get into the field.

He didn’t publicly commit to racing the marathon trials until now. He could still contest the track trials in June.

“Let’s start by Orlando... then we will see!” Chelimo’s agent wrote in an email when asked about track trials.

At marathon trials, the top three finishers on Feb. 3 are likely to make up the team for Paris. Since Chelimo has never raced a marathon, he also must run 2:11:30 or faster to hit a minimum qualifying time for Olympic eligibility.

Chelimo made five of the last six Olympic or world outdoor championships teams on the track in the 5000m. He won Olympic silver in 2016 and bronze in 2021, the latter being the lone U.S. men’s distance medal at the Tokyo Games.

Now, he joins a recent list of American global track medalists to move up to the marathon after Kara Goucher (2007 World 10,000m silver), Shalane Flanagan (2008 Olympic 10,000m silver), Galen Rupp (2012 Olympic 10,000m silver) and Bernard Lagat (world 5000m medals in 2007, 2009 and 2011).

Jenny Simpson, a world champion and Olympic bronze medalist at 1500m, also plans to make her marathon debut at the Feb. 3 trials.

Rupp made the 2016 Olympic marathon team in his debut at the distance at those trials. Molly Seidel did the same for the Tokyo Games. Each won a bronze medal in their first Olympic marathon.

Rupp, eyeing a fifth Olympics, headlines the men’s trials field along with Conner Mantz, the fastest American marathoner in 2022 and 2023 going for his first Games.

by Olympic Talk

Login to leave a comment

2028 US Olympic Trials Marathon

Most countries around the world use a selection committee to choose their Olympic Team Members, but not the USA. Prior to 1968, a series of races were used to select the USA Olympic Marathon team, but beginning in 1968 the format was changed to a single race on a single day with the top three finishers selected to be part...

more...Molly Seidel Stunned the World (and Herself) with Olympic Bronze in Tokyo. Then Life Went Sideways.

She stunned the world (and herself) with Olympic bronze in Tokyo. Then life went sideways. How America’s unexpected marathon phenom is getting her body—and brain—back on track.

On a clear December night in 2019, Molly Seidel was at a rooftop holiday party in Boston, wearing a black velvet dress, doing what a lot of 25-year-olds do: passing a joint between friends, wondering what she was doing with her life.

“You should run the Olympic Trials,” her sister, Izzy, said, as smoke swirled in the chilly air atop The Trackhouse, a retail shop and community hub on Newbury Street operated by the running brand Tracksmith. “That would be hilarious if you did that as your first marathon.”

Molly, an elite 10K racer who’d spent much of 2019 injured, looked out at the city lights, and laughed. Why the hell not? She’d just qualified for the trials, winning the San Antonio Half with a time of 1:10:27. (“The shock of the century,” as she’d put it.) True, 13.1 miles wasn’t 26.2—but running a marathon was something to do. If only because she never had before.

A four-time NCAA track and cross-country champion at The University of Notre Dame in Indiana, Molly had moved to Boston in 2017, where she’d worked three jobs to supplement her fourth: running for Saucony’s Freedom Track Club. The $34,000 a year that Saucony paid her (pre-tax, sans medical) didn’t go far in one of America’s most expensive cities. Chasing kids around as a babysitter, driving around as an Instacart shopper, and standing around eight hours a day as a barista—when you’re running 20 miles a day—wasn’t ideal. But whatever, she had compression socks. And she was downing free coffee and paying rent, flying to Flagstaff, Arizona, every so often for altitude camps, and having a good time. Doing what she loved. The only thing she’s ever wanted to do since she was a freckly fifth-grader in small-town Wisconsin clocking a six-minute mile in gym class.

“I was hustling, and I loved it. It was such a fun, cool time of my life,” she says, summarizing her 20s. Staring into Molly’s steely brown eyes, listening to her speak with such clarity and conviction about her struggles since, it’s easy to forget: She is still only 29.

After Molly had hip surgery on her birthday in July 2018, her doctors gave her a 50/50 chance of running professionally again. By summer 2019, she’d parted ways with FTC, which left her sobbing on the banks of the Charles River, getting eaten alive by mosquitoes and uncertainty. Her biggest achievement lately had been being named #2 Top Instacart Shopper (in Flagstaff; Boston was big-time).

The day after that rooftop party, Molly asked her friend and former FTC teammate Jon Green, who she’d newly anointed as her coach: “Think I should run the marathon trials?” Sure, he shrugged. Nothing to lose. Maybe it’d help her train for the 10K, her best shot—they both thought—at making a U.S. Olympic team.

“I’m going to get my ass kicked six ways to Sunday!” she told the host of the podcast Running On Om six weeks before the trials in Atlanta.

Instead, on February 29, 2020, she kicked some herself. Pushing past 448 of the fastest, most-experienced women marathoners in the country, coming in second with a 2:27:31, earning more in prize money ($60,000) than she had in two years of racing—and a spot on the U.S. trio for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, along with Kenyan-born superstars Aliphine Tuliamuk and Sally Kipyego. “I don’t know what’s happening right now!” Molly kept saying into TV cameras, wrapped in an American flag, as stunned as a lottery winner.

Saucony who? Puma came calling. Along with something Molly hadn’t anticipated: the spotlight. An onslaught of social media followers. And two weeks later, a global pandemic and lockdown—and all the anxiety and isolation that came with it. She was drowning, and she hadn’t even landed in Tokyo yet.

The 2020 Olympics, as we all know, were postponed to 2021. An emotional burden but a physical boon for Molly, in that it allowed her to get in a second marathon. In London, she finished two minutes faster than her debut. When the Olympics finally rolled around, she was ready.

Before the race, Molly says, “I was thinking: ‘Once I cross the starting line, I get to call myself an Olympian and that’s a win for the day.’”

But then she crossed the finish line—with a finger-kiss to the sky and a guttural Yesss!—in third place with a 2:27:46, just 26 seconds behind first (Kenya’s Peres Jepchirchir). And realized: She gets to call herself an Olympic medalist forever. Only the third American woman to ever earn one in the marathon.

Lots of kids have fleeting hopes of making it to the Olympics. I remember thinking I could be Mary Lou Retton. Maybe FloJo, with shorter fingernails. Then I decided I’d rather be Madonna or president of the United States and promptly forgot about it. But Molly held tight to her Olympic aspirations. She still has a poster she made in 2004, with stickers and a snapshot of her smiley 10-year-old self, to prove it. “I wish I will make it into the Olympics and win a gold medal,” she wrote, and signed it: Molly Seidel, the “y” looping back to underline her name. In case there was any doubt as to who, specifically, would be winning the medal.

Molly grew up in Nashotah, Wisconsin, and is the eldest of three. Her sister and brother, younger by not quite two years, are twins. Izzy is a running influencer and corporate content creator for companies like Peloton; and Fritz favors Formula 1 racing and weightlifting and works for the family’s leather-tanning business. The family was active, sporty. Dad, Fritz Sr., was a ski racer in college; Mom, Anne, a cheerleader. You can tell. Watching clips of Molly’s mom and dad watching the Olympic race from their backyard patio, jumping up and down, tears streaming, is the kind of life-affirming moment you wish you could bottle. “I’m in shock. I’m in disbelief,” Molly says into the mic, beaming. “I just wanted to come out today and I don’t know…stick my nose where it didn’t belong and see what I could come away with. And I guess that’s a medal.” When the interviewer holds up her family on FaceTime, Molly breaks down. “We did it,” she says into the screen between sobs and smiles. “Please drink a beer for me.

Molly hasn’t always been unabashedly herself, even when everyone thought she was. A compartmentalizer to the core, she spent most of her life hiding a huge part of it: anorexia, bulimia, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, debilitating depression.

It started around age 11, when she learned to disguise OCD tendencies, like compulsively knocking on wood, silently reciting prayers “to avoid God getting mad at me,” she says. “It was a whole thing.” She says her parents were aware of the behaviors, but saw them more as odd little habits. “They had no reason to suspect anything. I was very high-functioning,” she says. “They didn’t realize that it was literally taking over my life.”

She wasn’t officially diagnosed with OCD until her freshman year of college, when she saw a therapist for the first time. At Notre Dame, disordered eating took hold, quietly yet visibly, as it does for up to 62 percent of female college athletes, according to the National Eating Disorders Association. As recently as the Tokyo Olympics, she was making herself throw up in the airport bathroom, mere days before taking the podium. Molly hesitates to share that detail; she fears a girl might read this and interpret it as behavior to model. “Having been in that place as a younger athlete, I know I would have,” she says. But she also understands: Most people just don’t get how unrelenting eating disorders can be.

In February 2022, she finally received a diagnosis of the root cause for all of it: ADHD. About being diagnosed, she says, “It made me feel really good, like [I don’t have] a million different disorders. I have a disorder that manifests itself in a lot of different symptoms.”

She waited to try Adderall until after the Boston Marathon in April, only to drop out at mile 16 due to a hip impingement. Initially, the meds made her feel fantastic. Focused. Free. Until she realized Adderall hurt more than it helped. She couldn’t sleep, couldn’t eat, lost too much weight. Within weeks, she devolved. “The eating disorder came roaring back,” she says, referring to it, as she often does, as its own entity, something that exists outside of herself. That ruthlessly takes control over her very need for control. “I almost think of it as an alter ego,” she explains. “Adderall was just bubblegum in the dam,” as she puts it. She ditched the drug, and her life—professionally, physically—unraveled.

In July 2022, heading into the World Championships, she bombed the mental health screening, answering the questions with brutal honesty. She’d been texting Keira D’Amato weeks prior. “Yo girl, things are pretty bad right now. Get ready…” Sobbing on the sidewalk in Eugene, Oregon, she texted D’Amato again. And the USATF made it official: D’Amato would take her spot on the team. Then Molly did what she’d been “putting off and putting off”— checked herself into eating disorder treatment for the second time since 2016, an outpatient program in Salt Lake City, where her new boyfriend was living at the time.

Somehow (see: expert compartmentalizer) mid-meltdown, in February 2022, she had met an amateur ultrarunner named Matt, on Hinge. A quiet, lanky photographer, he didn’t totally get what she did. “I didn’t understand the gravity of it,” he tells me. “I was like, Oh she’s a pro runner, that’s cool. I didn’t realize she was, like, the pro runner!”

Going back to treatment “was pretty terrible,” she says. At least she could stay with Matt. Hardly a honeymoon phase, but the new relationship held promise. “I laid it all out there,” says Molly. “And he was still here for it, for all the messiness. It was really meaningful.” And a mental shift. “He doesn’t see me as just Molly the Runner.”

Almost a year later, on a freezing April evening in Flagstaff, Molly is racing around Whole Foods, palming a head of cabbage, grabbing a thing of hummus, hunting for deals even though she doesn’t need to anymore.

“It’s all about speed, efficiency, and quality,” she says, explaining the secret to her earlier Instacart success. She checks the expiration date on a container of goat cheese and beelines for the butcher counter, scans it faster than an Epson DS3000, though not without calculation, and requests two tomato-and-mozzarella-stuffed chicken breasts. Then she darts over to the beverage aisle in her marshmallow-y Puma slip-ons that Matt custom-painted with orange poppies. She grabs a case of La Croix (tangerine), then zips to the checkout. We’re in and out in under 15 minutes and 50 bucks, nothing bruised or broken.

Other than her body. Let’s just say: If Molly were an avocado or a carton of eggs, she probably wouldn’t pass her own sniff test. The week we meet, she is just coming off a month of no running. Not a single mile. She’s used to running twice a day, 130 miles a week. No wonder she’s spraying her kitchen counter with Mrs. Meyer’s and scrubbing the stovetop within minutes of welcoming me into her new home.

The place, which she shares with Matt and his Australian border collie, Rye, has a post-college flophouse feel: a deep L-shaped couch draped in Pendleton blankets, a bar cluttered with bottles of discount wine, a floor lamp leaning like the Tower of Pisa next to a chew toy in the shape of a ranch dressing bottle. Scattered about, though, are reminders that an elite runner sleeps here. Or at least tries to. (“Pro runner by day, mild insomniac by night” reads the bio on her rarely used account on what used to be Twitter.) There’s a stick of Chafe Safe on the coffee table. Shalane Flanagan’s cookbooks on the counter. And framed in glass, propped on the office floor: Molly’s Olympic kit—blue racing briefs with the Nike Swoosh, a USA singlet, her once-sweat-drenched American flag, folded in a triangle. “I’m not sure where to hang it,” she says. “It seems a little ostentatious to have it in the living room.”

With long brown curls and a round, freckly face, Molly has an aw-shucks look so innocent that it’s hard, at first, to perceive her struggles. Flat-out ask her, though—How are you even functioning?—and she’ll tell you: “I’m an absolute wreck. There’s no worse feeling than being a pro runner who can’t run. You just feel fucking useless.” Tidying a stack of newspapers, she adds, “Don’t worry, I’ve had therapy today.”

She’s watched every show. (Save Ted Lasso, “too sickly sweet.”) Listened to every podcast. (Armchair Expert is a favorite.) She’s got nothing else to do but PT and go easy on the ElliptiGo in the garage, onto which she’s rigged a wooden bookstand, currently clipped with A History of God: The 4,000 Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. “I don’t read running books,” she says. “I need something different.”

Like most runners—even the most amateur among us—running, moving, is what keeps her sane. “What about swimming? Can you at least swim?” I ask, projecting my own desperation if I were in her size 8.5 shoes. “I fucking hate swimming,” says Molly. Walking? “Oh, yeah, I can go on walks. Another. Long. Walk.”

The only thing she has on her schedule this week is pumping up a local middle school track team before their big meet. The invitation boosted her spirits. “Should I just memorize Miracle on Ice?” she says, laughing. “No, I know, I’ll do Independence Day.”

Injuries are nothing new for Molly. Par for the course for any professional athlete. But especially for women, like her, who lack bone density—and have since high school, when, according to a study in the Orthopedic Journal of Sports Medicine, nearly half of female runners experience period loss. Osteoporosis and its precursor, osteopenia, are rampant in female runners, leading to ongoing issues that threaten not just their college and professional running careers, but their lives.

Still, Molly admits, laughing: She’s especially accident-prone. I ask her to list every scratch she’s ever had, which takes her 10 minutes, and goes all the way back to babyhood, when she banged her head against the bathtub spout. There was a cracked spine from a sledding incident in 8th grade, a broken collarbone from a ski race in high school, shredded knee cartilage in college when a driver hit her while she was riding a bike. “Ribs are constantly breaking,” she says. In 2021, two snapped, and refused to heal in time for the New York City Marathon. No biggie. She ran through the pain with a 2:24:42, besting Deena Kastor’s 2008 time by more than a minute and setting the American course record.

Molly’s latest injury? Glute tear. “Literally a gigantic pain in the ass,” she posted on Instagram in March. Inside, Molly was devastated. Pulling out of the Nagoya Marathon—the night before her 6:45 a.m. flight to Japan, no less—was not in the plan. The plan, according to Coach Green, had been simple. It always is. If the two of them even have one. “Just to have fun and be consistent.” And get a marathon or two in before the Olympic Trials in February 2024.

She’d been finally—finally—fit on all fronts; ready to race, ready to return. She needed Nagoya. And then, nothing. “It feels like I’m back at the bottom of the well,” says Molly, driving home from Whole Foods in her Toyota 4Runner. “This last year-and-a-half has been so difficult. It’s just been a lot of doubt. How do I approach this, as someone who has now won a medal? Like, man, am I even relevant in this sport anymore?” She pops a piece of gum in her mouth. I wait for her to offer me some, because that’s what you do with gum, but she doesn’t. She’s so in her head. “It’s hard when you’re in the thick of it, you know, to figure out: Why the fuck do I keep doing this? When it just breaks my heart over and over and over again?”

We pull into her driveway. “I was prepared for the low period after Tokyo,” she says. “But this has been much longer and lower than I expected.”

The curse of making it to the Olympics, let alone coming back with a medal: expectations. Molly’s own were high. “I think I thought, after the Olympics, if I win a medal, then I will be fixed, it will fix everything.” Instead, in a way, it made everything worse.

That’s the problem that has plagued Molly for most of her running career: Her triumphs and troubles intermingle, like thunder and lightning. Which, by the way, she has been struck by. (A minor backyard-grill, summer-thunderstorm incident. She was fine.)

The next morning in Flagstaff, Molly’s feeling like she can run a mile, maybe two. It’s snowing, though, and she doesn’t want to risk the slippery track, so we meet at Campbell Mesa Trails. She loops a band around the back of her truck to stretch and sends me off into the trees to run alone while she does a couple of laps on the street.

Molly leaves for an acupuncture appointment, and we reunite later at Single Speed Coffee (“the best coffee in Flagstaff,” promises the ex-barista who drinks up to three cups a day). We curl up on a couch like it’s her living room, and she talks as freely—and as loudly—as if it was. Does she realize everyone can hear her? She doesn’t care. I guess that’s what happens when you’ve grown so comfortable sharing—in therapy, on podcasts, in a three-part video series on ADHD for WebMD—you just…share. Loud and proud.

Mental illness is so insidious, says Molly. “It’s not always this Sylvia Plath stick-my-head-in-a-fucking-oven thing, where you’re sad all the time,” she says. “High-functioning depressed people live normal successful lives. I can be having the happiest moment, and three days later I’m in a total downward spiral.” It’s something you never recover from, she says, but you learn to manage.

“I’m this incredibly flawed person who struggles so much. I think: How could I have won this thing when I’m so flawed? I look at all the people around me, all these accomplished people who have their shit together, and I’m like, ‘one of these things is not like the other,’” she says, taking a sip of her flat white. “I was literally in the Olympic Village thinking: Everybody is probably looking at me wondering: Why the hell is she here?”

They weren’t. They don’t. She knows that.

And yet her mind races as fast as she does. It takes up So. Much. Space. When she’s running, though, the noise disappears. She’s not Olympic Molly or Eating Disorder Molly, she’s not even, really, Runner Molly. “When I’m running,” she says, “I’m the most authentic version of myself.”

Talking helps, too. Molly first shared her mental health history a few years ago, “before she was famous,” as she puts it. After the Olympics, though, she kept talking and hasn’t stopped. The Tokyo Games were a turning point, she says. Suddenly the most revered athletes in the world were opening up about their mental health. Molly credits Simone Biles’s bravery for her own. If Biles, and Michael Phelps and Naomi Osaka, could come clean... then maybe a nerdy, niche-y, unlikely medaling marathoner could, too.

“Those guys got a lot more shit for it than I did,” says Molly. “I got off easy. I’m not a household name,” she laughs. She knows she can be candid and off the cuff—and chat freely in a not-empty café—in a way Biles never could. “I’m a nobody!” she laughs.

Still, a nobody with 232,000 Instagram followers whom she has touched in very IRL ways—becoming an unintentional poster woman for normalizing mental health challenges among athletes. “You are such an incredible inspiration,” @1percentpeterson posts, one comment of a zillion similar. “It’s ok to not be ok!” says another. Along with all the online love is, of course, online hate. Molly rattles off a few lowlights: “She’s an attention-seeking whore,” “Her bones are so brittle she’ll never race again,” “She’s running so badly and posting a lot she should really focus on her running more.” Molly finds it curious. “I’m like, ‘If you hate me, you don’t need to follow me, sir.’”

It’s Molly’s nobody-ness—what Outside writer Martin Fritz Huber called her “runner-next-door” persona, and I’ll just call “genuine personality”—that has made her somebody in running’s otherwise reserved circles.

Somebody who (gasp!) high-fives her sister in the middle of a major race, as she did at mile 18 of the 2021 New York City Marathon. “They shat on me in the broadcast for it,” she says. “They were like, ‘She’s not taking this seriously.’” (Except, uh, then she set the American course record, so…)

Somebody who, obviously, swears like a sailor and dances awkwardly on Instagram, who dresses up like a turkey, and viral-tweets about getting mansplained on an airplane. (“He starts telling me how I need to train high mileage & pulls up an analysis he’d made of a pro runner’s training on his phone. The pro runner was me. It was my training. Didn’t have the heart to tell him.”)

Somebody who makes every middle-aged mom-runner I know swoon like a Swiftie and say: “OMG! YOU HUNG OUT WITH MOLLY SEIDEL!!?” Middle-aged dad-runners, too. “I saw her once in Golden Gate Park!” my friend Dan fanboyed when he heard. “I waved!” Did she wave back? “She smiled,” he says, “while casually laying down 5:25s.”

And somebody who was as outraged as I was that I bought a $16 tube of French toothpaste from my hip Flagstaff motel. (It was 10 p.m.! It was all they had!) “For that price it better contain top-shelf cocaine,” she texted. Lest LetsRun commenters take that tidbit out of context: It’s a joke. It’s, in part, what makes Molly America’s most relatable pro runner: She’s not afraid to make jokes. (While we’re at it… Don’t knock her for smoking a little legal weed, either. That’s so 2009. Per the World Anti-Doping Agency: Cannabis is prohibited during competition, not at a Christmas party two months before it. Per Molly: “People would be shocked to know how many pro runners smoke weed.”)

I can’t believe I never asked to see it. Molly’s medal. A real, live Olympic medal. Maybe because it was tucked into a credenza along with Matt’s menorah and her maneki-neko cat figurines from Japan. But I think it was because hanging out with Molly felt so…normal, I almost forgot she’d won one.

People think elite distance runners have to be one-dimensional, she says. That they have to be sculpted, single-minded, running-only robots. “Because that’s what the sport has been,” she says.

Molly falls for it, too, she says. She scrolls the feeds, sees her fellow pros living seemingly perfect lives. She wants everyone to know: She’s not. So much so that she requested we not print the photos originally commissioned for this story, which were taken when she was at the lowest of lows. (“It’s been...refreshing...to be pretty open and real with Rachel [about] the challenges of the last year,” she wrote in an email to Runner’s World editors. “But the photos [were taken at] a time when I was really struggling and actively trying to hide how bad my eating disorder had become.”)

Molly finds the NYC Marathon high-five thing comical but indicative of a more serious issue in elite running: It takes itself too seriously. It’s too…elitist. Too stilted. “Running a marathon is a pretty freaking cool experience!” If you’re not having fun, she asks rhetorically, what’s the point? Still, she admits, she isn’t always having fun. Though you wouldn’t know it from her Instagram. “Oh, I’m very good at making it seem like I am,” she says.

She used to enjoy social media when it was just her friends. Before she gained 50,000 followers in a single day after the trials, and some 70,000 on Strava. Before the pandemic, before the Olympics. Keeping up with content became a toxic chore. “You feel like you’re just feeding this beast and it’s never going to stop,” she says. She’s taken to deleting the app off her phone, reloading it only to fulfill contractual agreements and post for her sponsors, then deleting it again.

As much as she hates having to post, she enjoys plugging products the only way that feels natural: through parody. As does Izzy, her influencer sister, who, like Molly, prefers to skewer rather than shill (à la their idea behind their joint Insta account: @sadgirltrackclub). “The classic influencer tropes make me want to throw up,” she says (perverse pun as a recovering bulimic not intended). “New Gear Drop!’ or ‘This is my Outfit of the Day!’ Cringe. “Hot Girl Instagram is not how I identify,” she says.

Nor is TikTok. “Sponsors tell me all the time: You should TikTok! I’m like, ‘I am not doing TikTok.’ I know how my brain works. They’ll say, ‘We’ll pay you less if you don’t’—and I’m, like, I don’t care.”

And to those sponsors who ghosted her after she returned to eating disorder treatment, good riddance. “Michelob dropped me like a bad habit,” she says. “Whatever. You have watery-ass beer anyway.”

To those who have stood by her, though, she’s utterly devoted. Pissed she couldn’t wear the Puma panther head to toe in Tokyo, Molly took off her Puma Deviate Elites and tied them over her shoulder, obscuring the Nike logo on her Olympic singlet for all the world to see. Or not see. “Nike isn’t paying my fucking bills.”

The love is mutual, says Erin Longin, a general manager at Puma. After decades backing legends like Usain Bolt, Puma was relaunching road running and wanted Molly as their guinea pig. “She’s a serious athlete and competitor, but she also has fun with it,” says Longin. “Running should be fun. Molly embodies that.” At their first meeting, in January 2020, Molly made them laugh and nerded out over their new shoes. “We all left there, fingers crossed she’d sign with us,” says Longin.

Come February, they all flipped out. Longin was watching the trials, not expecting much. And then: “We were all messaging, “OMG!!” Then Molly killed in London. Medaled in Tokyo. “What she did for us in that first year…” says Longin. “We couldn’t have planned it!”

Then came the second year, and the third, and throughout it all—injuries, eating disorder treatment, missed races, missed opportunities—Puma hasn’t flinched. “It’s easy for a company to do the right thing when everything is going great,” Molly posted in April, heartbroken from her couch instead of Heartbreak Hill. “But it’s when the sh*t hits the fan and they’re still right there with you….” She received 35,000 hearts—and a call from Longin: “You make me feel so proud.”

Does it matter to Puma if Molly never places—never races—again? “Nope,” Longin says.

My last afternoon in Flagstaff, it’s cloudy skies, still freezing. I find Molly on the high school track wearing neoprene gloves, black puffy coat, another pair of Pumas. Her breath is white, her cheeks red. Her legs churning in even, elegant strides. Upright, alone, at peace, backed by snow-dusted peaks. Running itself is what matters, not racing, she tells me. “I honestly don’t give a shit about winning,” she says. All she wants—really wants, she says—is to be healthy enough to run until she’s old and gray.

Molly’s favorite runner is one who didn’t get to grow old. Who made his mark decades before she was born: Steve Prefontaine. “Pre raced in such a genuine way. He made people feel something,” she says. “The sports performances you truly remember,” she adds, “are the ones where you see the struggle, the work, the realness.”

Sounds familiar. “I hate conversations like, ‘Who’s the GOAT?’” Molly continues. “Who fucking cares? Who’s got the story that’s going to get people excited? That’s going to make some kid want to go out and do it?”

I know one of those kids: My best friend’s daughter, Quinn, a rising track phenom in Oregon, who has dealt with anxiety and OCD tendencies. She has a picture of Molly Seidel, and her times, taped to her bedroom wall. This past May, Quinn joined Nike’s Bowerman Club. She was named Oregon Female Athlete of the Year Under 12 by USATF. She wants to run for Notre Dame.

“Quinn loves running more than anything,” her mom tells me, texting photos of her elated 11-year-old atop the podium. “But I don’t know…” She’s unsure about setting her daughter on this path. How could she not, though? It’s all Quinn wants to do. Maybe what Quinn, too, feels born to do.

It’ll be okay, I tell her, I hope. Quinn has something Molly never had: She has a Molly.

Molly and I catch up via phone in June. A team of doctors in Germany has overhauled her biomechanics. She’s been running 110 miles a week, feeling healthy, hopeful. Happy. A month later, severe anemia (and accompanying iron infusions) interrupts her summer racing schedule. She cancels the couple of 10Ks she had planned and entertains herself by popping into the UTMB Speedgoat Mountain Race: a 28K trail run through Utah’s Little Cottonwood Canyon—coming in second with a 3:49:58. Molly’s focus is on the Chicago Marathon, October 8th; her first major race in almost two years.

Does it matter how she does? Does it matter if she slays the Olympic Trials in February? If she makes it to Paris 2024? If she fulfills her childhood dream and brings home gold?

Nah. Not if—like Matt, like Puma, like, finally, even Molly herself—you see Molly the Runner for who she really is: Molly the Mere Mortal. She’s the imperfect one who puts it perfectly: What matters isn’t her time or place, how she performs on the pavement. Or social media posts. What matters—as a professional athlete, as a person—is how she makes people feel: human.

She’d been finally—finally—fit on all fronts; ready to race, ready to return. She needed Nagoya. And then, nothing. “It feels like I’m back at the bottom of the well,” says Molly, driving home from Whole Foods in her Toyota 4Runner. “This last year-and-a-half has been so difficult. It’s just been a lot of doubt. How do I approach this, as someone who has now won a medal? Like, man, am I even relevant in this sport anymore?” She pops a piece of gum in her mouth. I wait for her to offer me some, because that’s what you do with gum, but she doesn’t. She’s so in her head. “It’s hard when you’re in the thick of it, you know, to figure out: Why the fuck do I keep doing this? When it just breaks my heart over and over and over again?”

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

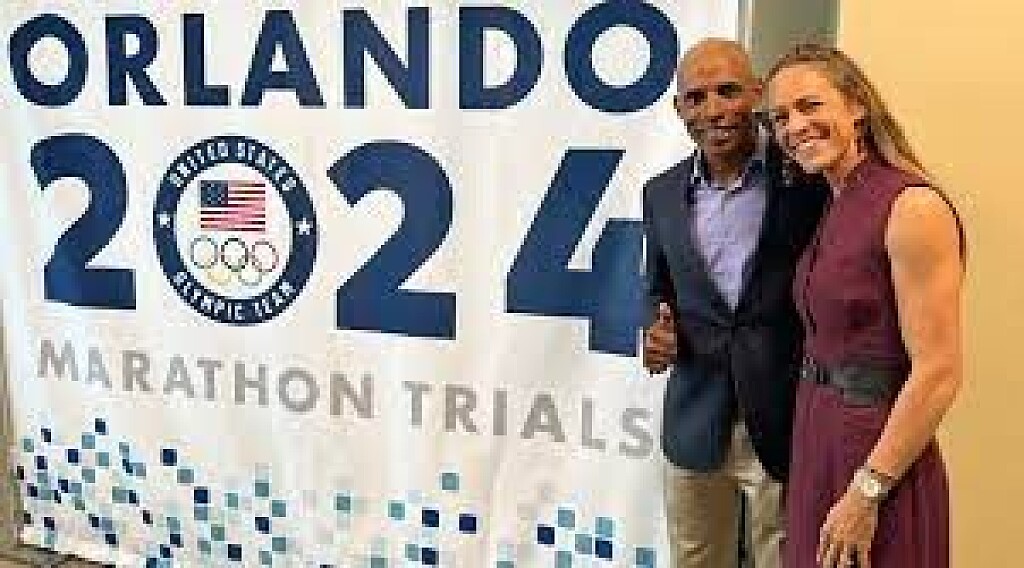

2024 U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials to start at 12 noon

USA Track and Field (USATF) caused a stir on social media on Tuesday after announcing in an email addressed to athletes that the 2024 Olympic Marathon Trials would begin at 12 noon, due to broadcasting rights. The marathon trials are scheduled to take place in Orlando, Fla., on Feb. 3, 2024.

The late start time has already caused worry for many coaches and athletes due to the potential for high temperatures. In February, the average temperatures in Orlando range from a low of 13 C to a high of 23 C, but in recent years, it has not been uncommon for temperatures to soar to 30 C–which would be detrimental to performance and potentially unsafe for elite marathoners.

According to Runners World, the email sent to athletes mentions that the Local Organizing Committee (LOC) in Orlando has extensive experience in planning and executing high-level events and has contingencies in place for any potential challenges, including weather-related ones.

The decision to set the start time at noon is believed to be influenced by executives at NBC, the network broadcasting the event. The email highlights that the race will be televised live on NBC for three hours, providing coverage of the men’s and women’s runners and races.

The Paris Olympic marathon, which is also expected to be warm, is scheduled for Aug. 10–the middle of summer in the French capital. But both the men’s and women’s races are set to begin at 8 a.m. local time. This disparity in start times has added to the concerns raised by the late start for the U.S. Trials in Orlando.

The U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials serves as the selection race for the men’s and women’s Olympic teams that will compete at the Summer Games in Paris. The top three finishers who also meet World Athletics’ qualifying standards will go on to represent Team USA at the Olympics.

Some athletes and coaches have expressed concern, while others seem to be looking forward to it. 2018 Boston Marathon champion Des Linden tweeted: “Warmer temps should slightly minimize the pace of super shoes and reward smarter racing. Count me in!”

U.S. ultrarunner Camille Herron said “We are seven months out from the Olympic Marathon Trials. No excuses to not be prepared for a potentially hot day in Florida.”

Renowned U.S. marathon coach Kevin Hanson, who currently has 13 athletes (eight women and five men) qualified for the U.S. Trials, stressed his disappointment that athletes’ health is not taken into consideration. “There is no amount of TV coverage that is worth the health of our athletes,” Hanson tweeted.

This isn’t the first time USATF has faced criticism for its handling of extreme heat during events. At the 2021 Olympic Track and Field Trials in Eugene, Ore., where temperatures were forecasted to reach highs of 40 C, several events were rescheduled for safety. However, the heptathlon was not, and athlete Taliyah Brooks collapsed on the track due to the heat and later filed a lawsuit against USATF.

In the 2016 Olympic Marathon Trials in Los Angeles, which began at 9 a.m., some athletes struggled on an unusually warm day, with temperatures reaching the mid-70s Fahrenheit. Shalane Flanagan, who placed third in 2:29:19, collapsed at the finish line, and the organizing committee and USATF later faced criticism for not providing adequate water on the course for the athletes.

by Marley Dickinson

Login to leave a comment

2028 US Olympic Trials Marathon

Most countries around the world use a selection committee to choose their Olympic Team Members, but not the USA. Prior to 1968, a series of races were used to select the USA Olympic Marathon team, but beginning in 1968 the format was changed to a single race on a single day with the top three finishers selected to be part...

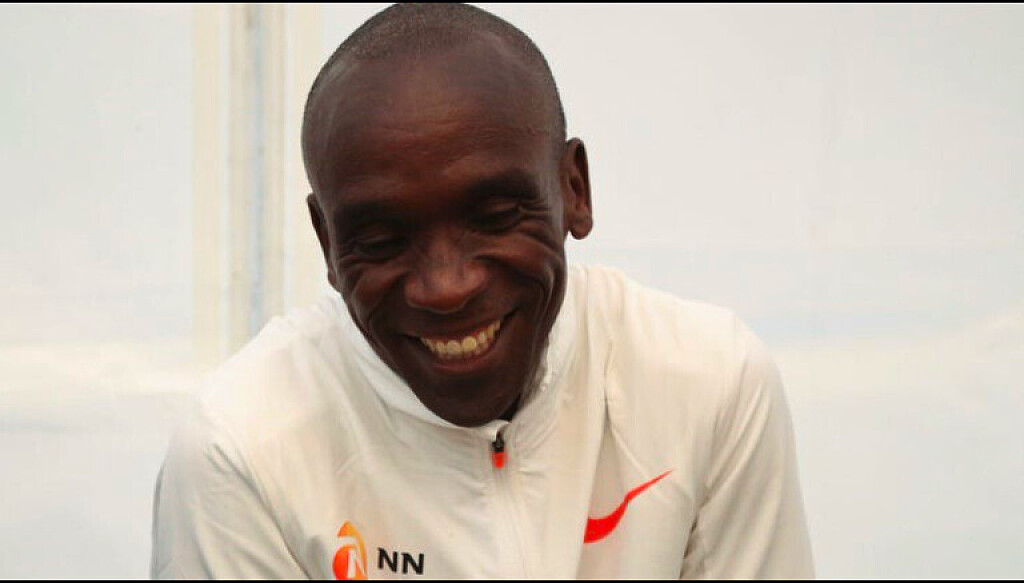

more...When Will Eliud Kipchoge Slow Down?

What we can learn from the world’s greatest distance runner of all-time while he’s still in his prime

Eliud Kipchoge has expanded the universe of what’s humanly possible in the marathon, and he will forever remain a legend in the sport of long-distance running.

Not only for himself, but especially for those who have come after him. That includes everyone, both elite and recreational runners, who are preparing a marathon this fall or some distant point in the future. His current 2:01:09 world record and his barrier-breaking 1:59:40 time-trial effort in 2019 are legendary feats, both for the current generation of runners and for all time.

The 38-year-old Kenyan marathoner is a once-in-a-lifetime athlete, but time waits for no one, and especially not a long-distance runner. Like all elite athletes, his time at the top is limited, but fortunately, there is still time to immerse in the inspirational examples he’s providing.

Kipchoge recently announced he’ll return to the Berlin Marathon on September 24, where, last year, he won the race for the fourth time and lowered the world record for the second time. It is most likely what will be the beginning of a grand denouement as he goes for another gold medal at the 2024 Olympics next summer in Paris.

Given that he won his first global medal in the City of Light—when, at the age of 18, he outran Moroccan legend Hicham El Guerrouj and Ethiopian legend-in-the-making Kenenisa Bekele to win the 5,000-meter run at the 2003 world championships—it would certainly be one of the greatest stories ever told if he could win the Olympic marathon there next year when he’s nearly 40.

Certainly he’ll run a few more races after the Olympics—and maybe through the 2028 Olympics in Los Angeles—but, realistically, it is the start of a farewell tour for a runner who will never be forgotten.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not at all writing Kipchoge off. In fact, I am excited to see him run in Berlin and can’t wait to watch next year’s Olympic marathon unfold. But just as we’ve watched Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods, Serena Williams, Shalane Flanagan, Usain Bolt, Allyson Felix, and other elite athletes succumb to the sunsetting of their peak performance level, so too will Kipchoge eventually suffer the same fate.

What I’m saying here is that we still have time to watch and appreciate Kipchoge eloquently working his magic and continue to be inspired in our own running and other pursuits in life. Remember how we marveled at Michael Jordan’s greatest in “The Last Dance” more than 20 years after his heyday? This is the start of the last dance for Kipchoge, who, like Jordan, is much, much more than a generational talent; he’s an all-time great whose legacy will transcend time.

Running has seen many extraordinary stars in the past 50 years who have become iconic figures— Frank Shorter, Joan Benoit Samuelson, Ted Corbitt, Carl Lewis, Steve Jones, Paul Tergat, Catherine Ndereba, Paula Radcliffe, Haile Gebrselassie, Kenenisa Bekele, Mary Keitany, Brigid Kosgei, and Kilian Jornet, to name a few—but none have come close to the body of work and global influence of Kipchoge.

Not only is Kipchoge one of the first African athletes to become a household name and truly command a global audience, but he’s done more than other running champions because of he’s been able to take advantage of this advanced age of digital media to deliberately push positive messages and inspiring content to anyone who is willing to receive it.

Kipchoge has won two Olympic gold medals, set two world records, and won 17 of the 19 marathons he entered, but he’s so much less about the stats and bling and more sharing—to runners and non-runners alike—that “no human is limited” and also that, despite our differences, we’re all human beings faced with a lot of the same challenges in life and, ultimately, hard work and kindness are what put us on the path to success.

How can an average runner who works a nine-to-five job and juggles dozens of other things in daily life be inspired by an elite aerobic machine like Kipchoge?

He is supremely talented, no doubt, but many elite runners have a similar aerobic capacity to allow them to compete on the world stage. What Kipchoge uniquely possesses—and why he’s become the greatest of all-time—is the awareness and ability to be relentless in his pursuit of excellence, and the presence and good will of how beneficial it is to share it.

If you haven’t been following Kipchoge or heard him speak at press conferences or sponsor events, he’s full of genuine wisdom and encouragement that can inspire you in your own running or challenging situation in life. His words come across much more powerfully than most other elite athletes or run-of-the-mill social media influencers, not only because he’s achieved at a higher level than anyone ever has, but because of his genuine interest in sharing the notion that it’s the simplest values—discipline, hard work, consistency, and selflessness—that make the difference in any endeavor.

This is not a suggestion to idolize Kipchoge, but instead to apply his wisdom and determination into the things that challenge you.

“If you want to break through, your mind should be able to control your body. Your mind should be a part of your fitness.”

“Only the disciplined ones in life are free. If you are undisciplined, you are a slave to your moods and your passions.”

“If you believe in something and put it in your mind and heart, it can be realized.”

“The best time to plant a tree was 25 years ago. The second-best time to plant a tree is today.”

Those are among the many simple messages that Kipchoge has lived by, but he also openly professess to giving himself grace to take time for mental and physical rest and recovery. It’s a simple recipe to follow, if you’re chasing your first or fastest marathon, or any tall task in life.

Kipchoge seems to defy age, but his sixth-place finish in the Boston Marathon in April proved he’s human. As much as it was painful to watch him falter, it was oddly refreshing and relatable to see him be something less than exceptional, and especially now that he’s tuning up for Berlin. He has nothing left to prove—to himself, to runners, to the world—but he’s bound to keep doing so just by following the same simple, undaunted regimen he always has.

There will be other young runners who will rise and run faster than Kipchoge and probably very soon. Fellow Kenyan Kelvin Kiptum—who has run 2:01:53 (Valencia) and 2:01:25 (London) in his first two marathons since December—seems to be next in line for Kipchoge’s throne of the world’s greatest runner. But even after that happens, Kipchoge’s name will go down in history alongside the likes of Paavo Nurmi, Abebe Bikila, Emil Zátopek, Grete Waitz, Shorter and Samuelson because of how he changed running and how he gave us a lens to view running without limits.

Berlin is definitely not the end of Kipchoge’s amazing career as the world’s greatest long-distance runner. I fully expect him to win again in an unfathomable time. But the sunset is imminent and, no matter if you are or have ever been an aspiring elite athlete at any level, a committed recreational runner, or just an occasional jogger trying to reap the fruits of consistent exercise, his example is still very tangible and something to behold.

by Outside Online

Login to leave a comment

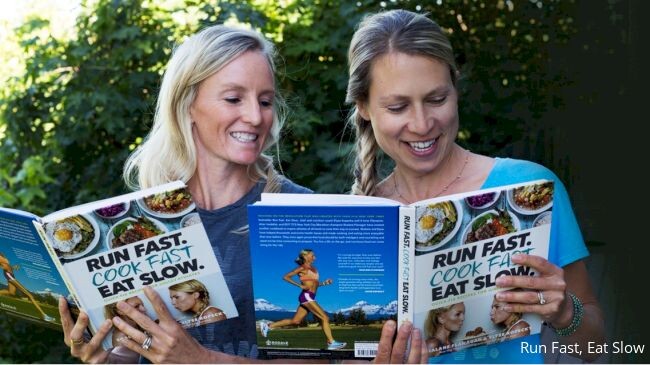

Shalane Flanagan’s Thai Quinoa Salad is a summer must-make

Shalane Flanagan has mastered the art of fueling on the fly. Flanagan, a four-time Olympian (twice in the marathon) and the 2017 New York City Marathon champion may be retired from professional competition, but she’s still a busy coach for Bowerman Track Club, a mom and co-author of three cookbooks with her friend and former teammate, Elyse Kopecki.

Flanagan has decades of experience in cooking and planning meals that both help her run fast and keep her healthy and energized. This recipe is easy to throw together or prep in advance. I love making a double batch of the dressing and freezing it for next time. While it’s perfect as-is, feel free to add whatever veggies or protein your family enjoys–throwing in a can of chickpeas and/or some chicken gives our household a protein boost when we make this one.

Shalane’s Thai Quinoa Salad

Ingredients

1 cup quinoa, rinsed and drained

2 cups grated carrots (about 2 large)

2 cups thinly sliced purple cabbage

3 green onions, white and green parts sliced

1 cup packed mint or cilantro leaves, chopped

1 cup packed basil leaves, chopped

1 jalapeño pepper, seeds removed and minced (optional)

1/2 cup chopped roasted peanuts

Dressing

1/4 cup extra-virgin olive oil

1/3 cup fresh lime juice

2 Tbsp honey or maple syrup

2 Tbsp soy sauce (tamari works as well)

1 Tbsp fish sauce (optional, remove to make the recipe vegan)

Directions

Cook your quinoa perfectly with Flanagan’s foolproof method: in a medium saucepan over high heat, bring 1 1/2 cups water to a boil with the quinoa. Reduce the heat to low and simmer, covered, for roughly 15 minutes or until all the water is absorbed. Fluff with a fork and transfer to a large salad bowl to cool.

Put the olive oil, lime juice, soy sauce or tamari, honey, and fish sauce in a glass jar and shake or stir until combined.

When the quinoa has cooled, add carrots, cabbage, onion, mint, basil, and pepper to the bowl, toss to combine. Add dressing and mix together. Top with the peanuts, and chill in the fridge for at least an hour before serving.

by Running Magazine

Login to leave a comment

World class racing returns to Boston on Sunday with the BAA 10K

The BAA 10K is this Sunday in Boston. The elites—as well as a mass field of nearly 10,000 runners—will race through the streets of the Back Bay neighborhood.

Emily Sisson has her eyes on another American record; she’s been on a tear the past year on the roads. In October, at the 2022 Chicago Marathon, she took 43 seconds off Keira D’Amato’s American record, running 2:18:29 for second place. Three months later, at the Houston Half Marathon, she broke her own American record, crossing the line in 1:06:52. She’s setting her sights on Shalane Flanagan’s 10K record of 30:52, which Flanagan set at the 2016 edition of the BAA 10K.

Also toeing the line is Molly Seidel, who’s been running some shorter races to prepare for a fall marathon. In February, she finished eighth at the U.S. Half Marathon Championships in 1:13:08.

A slew of former Boston Marathon champions are also competing on Sunday. Hellen Obiri, who won April’s race, will line up next to two-time champion Edna Kiplagat and 2015 winner Caroline Rotich. The course record of 30:36 could be up for grabs.

The men’s field is highlighted by 2021 Boston Marathon champion Benson Kipruto, who won the BAA 10K in 2018. American Leonard Korir returns as the race’s reigning champion, taking last year’s win in 28:00—12 seconds off the American record of 27:48 that has stood since 1985. Gabriel Geay, Geoffrey Koech, and Tsegay Kidanu should also be in contention.

Those in the Boston area can catch coverage of the race on WCVB. The BAA Racing App will also provide live updates and results, but there is no stream of the race. The elites are scheduled to start at 8 a.m. ET.

by Runner's World

Login to leave a comment

B.A.A. 10K

The 6.2-mile course is a scenic tour through Boston's Back Bay. Notable neighborhoods and attractions include the legendary Bull and Finch Pub, after which the television series "Cheers" was developed, the campus of Boston University, and trendy Kenmore Square. ...

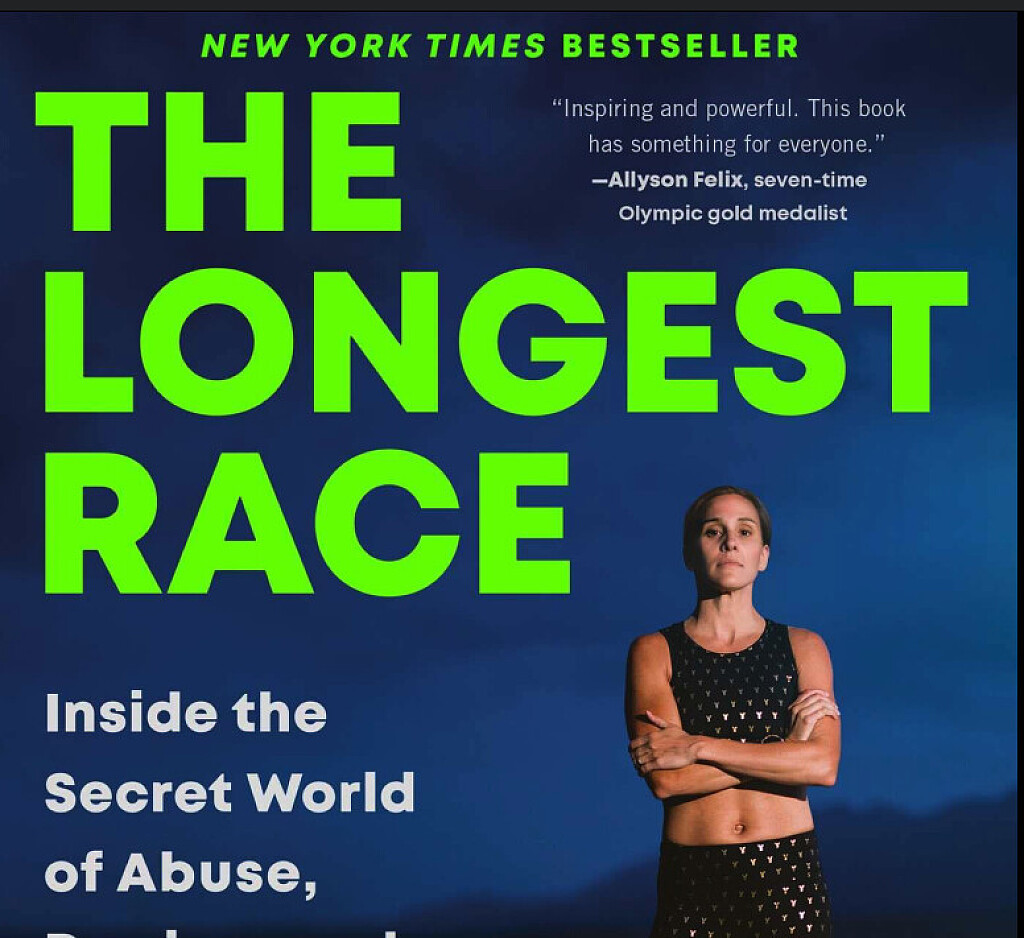

more...Kara Goucher’s Book Offers Rare Insight Into Elite Athlete Contracts

Confidentiality clauses usually stop runners from talking about their endorsement deals.Kara Goucher’s memoir about her career in professional running, The Longest Race, alleges shocking behavior by her longtime coach, Alberto Salazar, and how she overcame it. But a subplot throughout the book is how much money she was earning in the sport along the way.

Goucher is open about her contract with Nike and appearance fees at races, including the New York City Marathon, the Boston Marathon, and the Great North Run in the U.K. (Nike did not respond to an email from Runner’s World seeking comment.) Even though the deals are from 10 to 20 years ago, they provide an interesting look at the business side of professional running. It’s a rare peek, too, because sponsor contracts are bound by confidentiality clauses and, in many cases, those clauses extend beyond the term of the contract.

Goucher’s did, but she decided to reveal the information anyway—to be helpful to other athletes. “I just felt like it was very important to have those numbers in there,” she said in a phone call with Runner’s World. “How do you know what to ask for if you have no idea what anyone else is getting paid?” Here’s what we learned about Goucher’s pay and that of her husband, Adam Goucher, from the book:

In 2000, Adam Goucher was making a base payment of $50,000 from Fila, his first sponsor. In his first year, he ran so well that he earned $185,000 with bonuses. Goucher writes that the pay was a “welcome windfall that helped him pay off student loans.”

In 2001, Kara Goucher signed a four-year deal with Nike for $35,000 per year. This was her first professional contract after she graduated from the University of Colorado.

In 2003, Adam Goucher signed with Nike with a base pay of $90,000 per year. The Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamIn the fall of 2007, she ran the Great North Run, a half marathon in Newcastle, England. The race director paid her an appearance fee of $13,000 and made a deal with Goucher’s agent at the time, Peter Stubbs, to pay her $30,000 if she won. The money was “not far off the annual salary I had lived on for years,” Goucher wrote. She won the race.

In February 2008, Goucher signed a new Nike deal that paid her $325,000 per year for four years, with an option for Nike to extend to a fifth year. The contract included performance bonuses ranging from $10,000 to $500,000 for an Olympic gold medal. There were also reductions, which could cut her pay. She had to race 10 USATF-sanctioned events per year, and if she ended the year ranked lower than third in her event in the U.S. or out of the top 10 in the world, Nike could dock her pay.

Goucher told Runner’s World that, for her second shoe deal, she asked her agent to accept a commission of 8 percent for each year of the deal. The industry standard is 15 percent. He agreed. She continued to pay him 15 percent on her appearance fees and prize money. She also made sure that she was paid directly by Nike and then she paid her agent. (In most cases these days, the shoe company pays the agent, who then pays the athletes, because it’s less paperwork for the shoe company, having to deal with individual athletes.)

In November 2008, Goucher made her marathon debut at the New York City Marathon. She earned an appearance fee of $175,000. Nike also paid her bonuses paid on based on her place and time, but Goucher didn’t disclose those. She wrote, “One good marathon and I could easily walk away with more than my yearly contract salary.” In April 2009, Goucher ran the Boston Marathon, which, at the time, traditionally paid less in appearance fees to athletes than New York. (It is also the only major marathon in the U.S. in the spring.) Her appearance fee was $80,000, but when she learned another American, a male runner, was making $85,000, she asked the BAA to match that. Race organizers agreed.

In early 2010, Goucher learned she was pregnant with her son, Colt. Salazar confirmed with Nike executive John Capriotti on Goucher’s behalf that Goucher wouldn’t suffer a reduction in her pay as long as she remained “relevant,” she wrote. Her first of four quarterly payments from Nike arrived on time in January, as did her second in April. But in July, her accountant told her that her payment hadn’t arrived. Nor did her October payment.

This set off a lengthy battle between Goucher and Nike over money during her pregnancy. Ultimately, Nike docked her pay for six months and extended her contract to the end of 2013.

At the end of 2010, Adam Goucher’s contract with Nike ended.

In 2011, USA Track & Field (USATF) said it would be dropping the Gouchers’ health insurance, because her marathon ranking had dropped while she was pregnant. She appealed the decision, and the U.S. Olympic Committee stepped in and reinstated the health insurance. This rule has subsequently been changed—pregnant athletes can keep their health insurance—and today’s runners laud that change.

At the end of September 2011, Goucher left the Nike Oregon Project. She remained under contract with Nike and stayed in Portland, Oregon. Jerry Schumacher coached her, and she trained with Shalane Flanagan.

At the end of 2013, Goucher scrambled to race 10 times so Nike wouldn’t suspend her pay again. She ran a turkey trot to fulfill her obligations (and won a pie). Her contract with Nike ended at the end of the year, and she and Adam sold their house in Portland and moved to Boulder, Colorado.

In 2014, Goucher entertained contract offers from other companies, although Nike still had the option to match any offers. Saucony offered her $1 million total over 5 years, with bonuses and no reductions. Ultimately, she chose to sign with women’s clothing brand Oiselle for $20,000 per year, and a 2 percent stake in the company. She signed a separate deal for footwear with Skechers.

Today, Goucher encourages athletes to speak up and not be afraid to rock the boat, especially those who are lower-paid. She faults the secrecy around pay in track and field with creating difficult situations. It’s required to agree to the confidentiality clause in contracts in order to secure the deal, she said, and in some cases, that gives cover to companies that underpay talented athletes. The confidentiality clause “only harms the athlete and protects the brand,” she said. “Because then they can continue to pay you the least amount possible.”

Agent Hawi Keflezighi, who has never worked with Goucher, agreed with her assessment. “I think there are a lot of very bad contracts out there that footwear brands would probably be embarrassed to admit to,” he said. “There are some really bad deals out there that would probably create a backlash.”

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

The Boston Marathon has never been easy, that’s why Des Linden keeps coming back

The conditions were wretched when Des Linden first toed the starting line in Hopkinton in 2007. An amped-up nor’easter brought rain, a 30-mile-per-hour headwind, and soggy, chilly misery for the runners.

“I was one probably of the few people who felt, that was one of the best things I’ve ever done,” Linden recalled years later. “I’m going to do this forever. I loved it.”

On Patriots Day Linden will lace up for her 10th Boston Marathon. During the 16 years since her first appearance here, which also was her 26-mile debut, Linden has won the laurel wreath (”storybook stuff”), lost by two seconds on a sprint down Boylston Street, finished fourth twice, and 17th in a “total suffer-fest.”

Every trip here is a homecoming, said the California native and Michigan resident who has a dog named Boston. What brings Linden back is the race’s incomparable history, the feeling of family that she gets from the Boston Athletic Association, the exuberant crowds along the course, “the greatest finish line in our sport,” and the unchanging challenge from the lumpy layout and mercurial weather.

“We’re in this era where we want the marathon to be easier than ever before,” said Linden. “We want it faster, we want it flatter, we want wind blockers, we want shoes that bounce you forward, we want better gels. You name it, we’re trying to dumb this thing down. Boston is already not going to manage well with a lot of those things, then you throw in the weather conditions. I’ll take the tough one every time.”

Boston never has been easy. For decades there were no mile markers or water on the course. There was no prize money until 1986 — the reward was a medal and a bowl of canned beef stew. The starter fired the gun and sent you off. If you ended up sitting on the curb, cramped and blistered, the “meat wagon” picked you up.

Linden loves the purity of a race that always has the same course but rarely the same conditions. “A lot of people get surprised by it,” she said. “Well, it’s Boston in the spring.”

Boston is the recurring theme of “Choosing To Run,” Linden’s new memoir written with Bonnie D. Ford. Chapters recounting her 2018 triumph, the first by an American woman here in 33 years, are interspersed with a narrative of her evolution from a track racer to a marathoner.

Linden, who’ll officially become a master when she turns 40 in late July, is in the final stretch of her elite career, which she hopes will include a third Olympic team next year in Paris. Maybe she’ll run a fall marathon to prep for the Orlando trials in February. “Or maybe I just spin the legs and do some fast stuff,” she mused.

At this stage of her career it’s all about being smart and patient. “It’s a challenge letting go of your prime years, but there’s also a reality to it,” Linden said. “It’s recalibrating and readjusting what the goal is. I’m learning.”

One significant concession is her weekly mileage, which Linden has reduced from 120 to between 95 and 105. “I have this mentality that I’m being lazy if I’m not doing 115-120-mile weeks,” she said. “ ‘You’re not being lazy,’ my coach [Walt Drenth] said. ‘It’s just not practical.’ ”