Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #Marathon Des Sables

Today's Running News

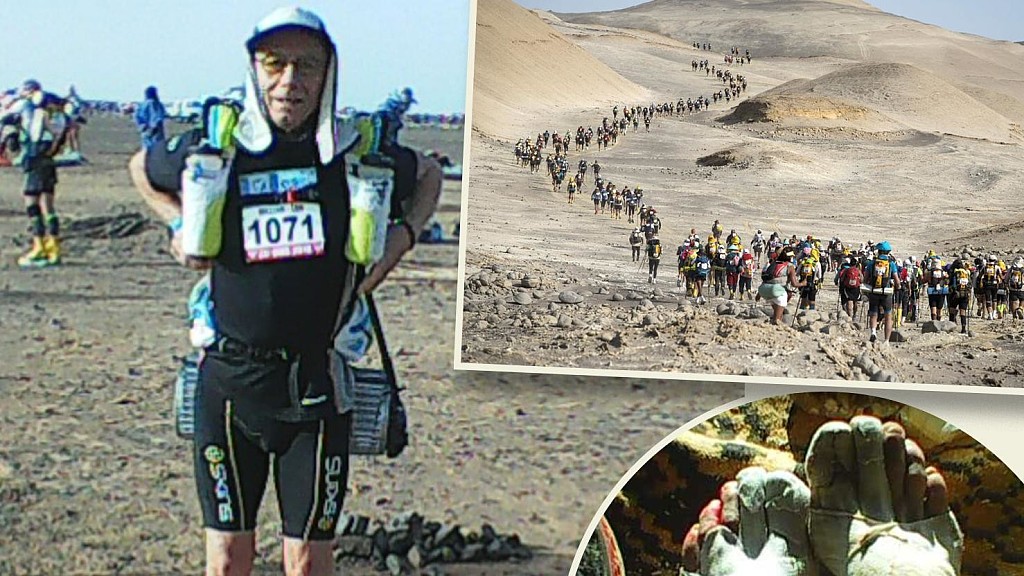

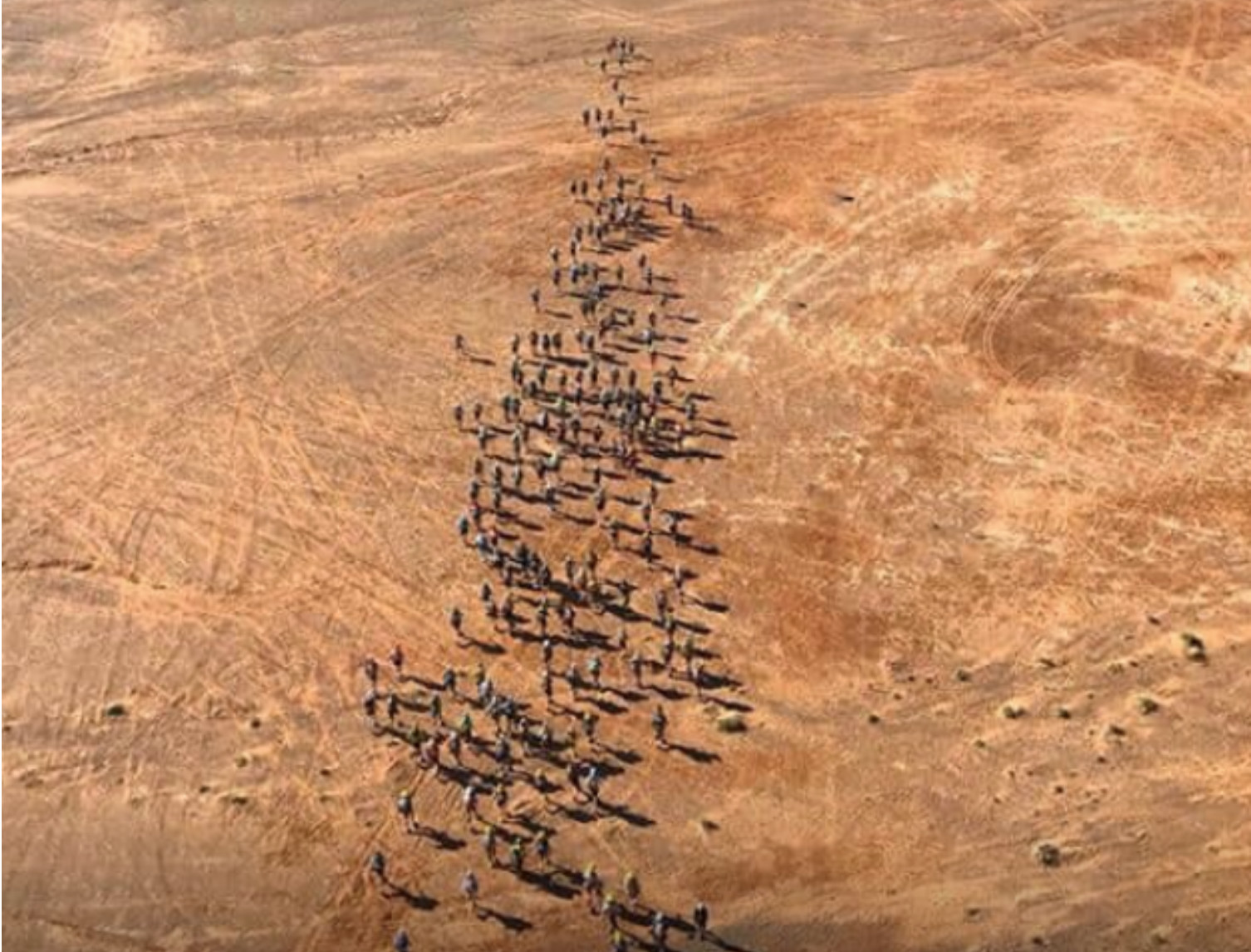

Surviving the Sahara – Inside the Marathon des Sables, the World’s Toughest Footrace

Dubbed the toughest footrace on Earth, the Marathon des Sables (MdS) is a grueling multi-day ultramarathon that challenges participants to traverse approximately 250 kilometers across the unforgiving terrain of the Moroccan Sahara Desert. This annual event tests the limits of human endurance, self-sufficiency, and resilience.

A Brief History of a Brutal Race

The Marathon des Sables was conceived by Frenchman Patrick Bauer, who in 1984 embarked on a solo trek of 350 kilometers across the Sahara Desert. Inspired to share this transformative experience, Bauer organized the inaugural race in 1986 with just 23 participants. Since then, the MdS has grown exponentially, attracting over a thousand competitors annually from around the globe.

The Race Format – Six Days of Pain and Perseverance

The MdS spans six stages over seven days, covering diverse and challenging terrains:

• Stages 1–3: Medium-distance runs of 30–40 km each.

• Stage 4 (The Long Day): An arduous 80+ km stretch, often extending into the night.

• Stage 5: A standard marathon distance of 42.2 km.

• Stage 6: A non-competitive charity stage, approximately 10 km, fostering camaraderie among participants.

Competitors must be self-sufficient, carrying their own food, equipment, and personal belongings throughout the race. Water is rationed and provided at checkpoints, and communal Berber tents are set up at designated bivouac sites for overnight stays.

Training and Preparation – Building the Body and the Mind

Preparation for the MdS requires a comprehensive approach:

• Endurance Training: Incorporating high-mileage runs, often back-to-back, to simulate race conditions.

• Strength Conditioning: Focusing on core and lower-body strength to handle the added weight of the backpack.

• Heat Acclimatization: Training in heated environments or during peak temperatures to adapt to desert conditions.

• Mental Fortitude: Developing strategies to cope with isolation, fatigue, and the psychological demands of the race.

Many participants also engage in simulated self-sufficiency exercises, practicing with their race gear and nutrition plans to ensure efficiency and comfort during the event.

Gear and Packing Essentials – Living Out of a Backpack

Competitors are required to carry mandatory equipment, including:

• Sleeping bag

• Headlamp and spare batteries

• Compass and roadbook

• Emergency whistle and signaling mirror

• Minimum of 2,000 calories per day

• First-aid supplies, cooking equipment, and survival gear

Optional items often include gaiters to prevent sand ingress, specialized desert footwear, and comprehensive blister care kits. Balancing pack weight (typically between 6.5 to 15 kg) with essential supplies is crucial for performance and comfort.

The Daily Grind – Life in the Desert

Each day begins before dawn, with participants breaking camp and preparing for the day’s stage. The course presents a variety of challenges, from towering sand dunes to rocky jebels (mountains), under the relentless desert sun. Checkpoints provide rationed water and medical support, but the journey between them is a true test of endurance.

Evenings are spent at bivouac sites, where runners tend to injuries, share experiences, and rest under the starlit Sahara sky, fostering a unique sense of community and mutual support.

Famous Runners and Legendary Stories

The MdS has seen remarkable athletes:

• Rachid El Morabity: A Moroccan runner with multiple victories, renowned for his dominance in desert ultramarathons.

• Laurence Klein: A French athlete with several MdS wins, exemplifying endurance and resilience.

Inspirational tales abound, such as that of Mauro Prosperi, an Italian competitor who in 1994 survived nine days lost in the desert after a sandstorm veered him off course—drinking bat urine and eating lizards before eventually being rescued.

Why They Keep Coming Back

For many, one MdS is enough. For others, it becomes an annual pilgrimage. The appeal goes beyond running—it’s about testing your limits and discovering who you really are when stripped of all comfort.

The camaraderie, the solitude, the intensity, and the transformation draw people back. In a world filled with convenience, the MdS offers a rare crucible: a space where pain becomes purpose and exhaustion becomes transcendence.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

An amazing challenge. I am sure the feeling of crossing the finish line must be a feeling that would be hard to put in words. - Bob Anderson 4/4 3:11 am |

Marathon Des Sables

The Marathon des Sables is ranked by the Discovery Channel as the toughest footrace on earth. Seven days 250k Known simply as the MdS, the race is a gruelling multi-stage adventure through a formidable landscape in one of the world’s most inhospitable climates - the Sahara desert. The rules require you to be self-sufficient, to carry with you on your...

more...Harry Hunter, 75, set to take part in Marathon Des Sables in Morocco

Harry Hunter will soon be flying out to Morocco to take part in the Marathon Des Sables in aid of Alexander Devine Children's Hospice.

Harry Hunter, 75, from Windsor, will be taking part in the race in April and hopes to raise funds for the hospice, which is the only specialist children's hospice serving Berkshire and surrounding counties.

The race is in its 38th year and is a multiday race held in southern Morocco, in the Sahara Desert. This year the total distance is 252km over six stages.

A fellow boot camper of Mr Hunter's has described him as an "inspirational character", having served for 22 years in the Blues and Royals in Windsor.

He is not a stranger to extreme challenges for charity and is "well known" in the area.

Mr Hunter will be 76 years old on the second day of the race, making him the oldest man to run it.

A fundraiser on Just Giving has been launched with a target of raising £2,000 for charity.

Alexander Devine Children's Hospice currently supports over 165 children and their families, but they are committed to growing their service and reaching out to every child and their family that needs them.

The hospice needs £2.8 million of funding each year and most of this comes from donations.

by Daisy Waites

Login to leave a comment

Marathon Des Sables

The Marathon des Sables is ranked by the Discovery Channel as the toughest footrace on earth. Seven days 250k Known simply as the MdS, the race is a gruelling multi-stage adventure through a formidable landscape in one of the world’s most inhospitable climates - the Sahara desert. The rules require you to be self-sufficient, to carry with you on your...

more...Olympian Army major gets ready for 250km ultramarathon

Two-time Olympic rowing champion and Army major Heather Stanning is ready for her next challenge.

Alongside a famous face, she is set to take on the Marathon des Sables, an extraordinary race and adventure that's been taking place in the southern Moroccan Sahara since 1986.

Forces News caught up with her in Cyprus during training.

This event is the ultimate ultra race and certainly not for the faint-hearted – which is probably why Maj Stanning said 'yes' when asked if she would take part.

The Marathon des Sables sees competitors race 250km over six days, self-sufficient and in the Sahara desert.

Maj Stanning's team is made up of three other British Army personnel and TV personality Judge Robert Rinder.

Maj Stanning said: "Why am I doing it?

"The Army Benevolent Fund approached me and said 'It's our 80th year, we want to do a big challenge, raise awareness and raise some money, will you do this challenge for us?'.

"I was like 'Oh absolutely' and then they told me, I was like 'Oh wow, that is a challenge'."

"I've been training since before Christmas, just gradually building up," Maj Stanning explained.

"For me, the biggest thing is staying in one piece and not getting injured.

"I may not be doing loads and loads of miles every week, but it's just gradually building up.

"It's time on my feet. Quite honestly, I will probably walk the majority of it. And that's probably where us in the military will do quite well.

"Let's not think we are all going to be ultra runners and break some records. It's about getting to the finish line."

by Sofie Cacoyannis

Login to leave a comment

Marathon Des Sables

The Marathon des Sables is ranked by the Discovery Channel as the toughest footrace on earth. Seven days 250k Known simply as the MdS, the race is a gruelling multi-stage adventure through a formidable landscape in one of the world’s most inhospitable climates - the Sahara desert. The rules require you to be self-sufficient, to carry with you on your...

more...2023 Western States 100 Men’s Preview

The Western States 100 is set for 2023. The iconic point-to-point, net-downhill course takes in 100.2 miles, 18,000 feet of climbing, and 22,000 feet of descending, as it starts at the Palisades Tahoe ski resort in Olympic Valley, California, and finishes at Placer High School in Auburn.

Environmental conditions will play into the race’s competitive story this year. With record snowfall throughout the upper elevations of the Sierra Nevada, the mountain range through which the race travels, runners will encounter plenty of snow over the course’s first quarter, along with numerous high water crossings lower down as all that snow melts.

Some 16 miles of the course were burned over by last fall’s Mosquito Fire, leaving miles of shade-less terrain. And of course, there will probably be weather at play, with the event’s notorious heat likely to encompass the middle and lower elevations of the course.

The men’s race at last year’s Western States 100 was sharp, with just 50 minutes separating the first and 10th finishers. Seven of that stellar line-up are back this year, as well as some serious additions like the U.K.’s Tom Evans, French-Canadian Mathieu Blanchard, and Dakota Jones.

Although there are notable absentees including reigning champion Adam Peterman and course-record holder Jim Walmsley, the depth of this men’s field suggests it could be an even tighter race this year.

As you’d guess, iRunFar will be there to report firsthand on all the action as it unfolds starting at 5 a.m. U.S. PDT on Saturday, June 24. Stay tuned!

A special thanks to HOKA for making our coverage of the Western States 100 possible!

Be sure to check out our in-depth women’s preview to learn about the women’s race and, then, follow our live coverage on race day!

The top 10 runners in the 2022 race were invited to return for 2023. Unfortunately, reigning champion Adam Peterman is out with injury, and seventh-place Vincent Viet of France has opted not to return. It also looks like fifth-place Drew Holmen has withdrawn, as he just finished fifth at the Trail World Championships 80k, held in Austria 15 days before Western States.

Hayden Hawks – 2nd, 15:47:27

Last year’s second-place man, Hayden Hawks, was pretty jovial in his post-race interview about not being able to best race winner Adam Peterman. But without the reigning champion present on the start line, this could be Hawks’s year. Despite struggling with the heat last year, his finish time knocked two hours off his eighth-place finish from 2021, and there are lots of indicators that he could have more to offer on this course.

Some of his previous top performances include a 5:18 win at the 2020 JFK 50 Mile and a win at the 2018 Lavaredo Ultra Trail. So far this year, he’s warmed up by winning the Canyons 50k and taking second at the Tarawera Ultramarathon 100k.

Arlen Glick – 3rd, 15:56:17

Arlen Glick surpassed a lot of people’s expectations when he took third at Western States last year. Although he went into the race with bag of form in the 100-mile distance — having won the Javelina 100 Mile, the Mohican 100 Mile and the Burning River 100 Mile all in 2021 — this was his initiation into mountainous ultrarunning. He took to it very well, running a stormer to place third, and has since logged more mountain miles, taking second in the Run Rabbit Run 100 Mile later in 2022, before returning to the 2022 Javelina 100 Mile to place third.

Tyler Green – 4th, 15:57:10

Tyler Green took fourth at Western States last year, and forced third-place Arlen Glick into an uncomfortable sprint finish as he closed on him in the race’s final moments. In terms of placing, he was back from his second-place finish in 2021, but improved his finish time by about 14 minutes in his third go at the race. In 2019, he placed 14th in a time of 16:51, in what was a very fast year.

Following on from Western States last summer, he had a below par run at the 2022 UTMB, making it just inside the top 50, but showed he is back on form with a third-place finish at the 2023 Transgrancanaria. Last year in his pre-race interview he spoke about stepping back from his day job of teaching to focus more on track coaching and his own running, so that may have allowed him to come into this year’s race with better preparation than previous years.

Ludovic Pommeret (France)

Ludovic Pommeret, sixth at last year’s Western States, went on to inspire veteran racers everywhere with a commanding win at the 2022 TDS at age 47 — almost an hour clear of second place on the demanding route. Some of his other top performances include a win at the 2016 UTMB, where he also took fourth in 2021, and a win at the 2021 Diagonale des Fous.

He’s probably at the other end of the spectrum of Arlen Glick, in that his best performances have been on courses more mountainous than this one, but he’s still not to be underestimated.

Not many ultra-trail runners have made Kilian Jornet sweat to the degree that French-Canadian Mathieu Blanchard did at last year’s UTMB. The two battled it out all day for a close finish, in which Blanchard took second place — under the existing course record — thus earning his Golden Ticket into Western States. He’s been mixing it up a lot this year, taking second in the 146-mile Coastal Challenge Expedition Run stage race in Costa Rica, third in the Marathon des Sables, and running 2:22 in what looked like a fairly casual effort at the Paris Marathon.

by Sarah Brady

Login to leave a comment

Western States 100

The Western States ® 100-Mile Endurance Run is the world’s oldest and most prestigious 100-mile trail race. Starting in Squaw Valley, California near the site of the 1960 Winter Olympics and ending 100.2 miles later in Auburn, California, Western States, in the decades since its inception in 1974, has come to represent one of the ultimate endurance tests in the...

more...Tete Dijana looks to defend his crown at Comrades Marathon

The 2023 Comrades Marathon is nearly upon us, with thousands preparing to take on the down route from Pietermaritzburg to Durban.

This year’s race has an official race distance of 87.7km, as competitors race for victory in a number of prize categories – the men and women’s winners earning over €20,000.

The men’s field this year features a number of past winners – as does the women’s – and promises to be an exciting race from start to finish.

Dijana aims to crown Nedbank again

Last year saw five of the top seven finishers all come from the Nedbank running club, but it was Tete Dijana who proved chief amongst them.

He won last year’s race in a time of 5:30:38, with clubmate and 2019 winner Edward Mothibi three minutes behind him and Dan Matshailwe, another Nedbank runner, a further three minutes behind Mothibi.

Expect all those names to feature near the top three, with Nedbank set to work together once more to assert dominance over South Africa’s most famous ultra.

Perhaps the chief non-Nedbank competitor will be 2018 winner Bongmusa Mthembu. Fourth last year, he was the fastest non-Nedbank runner and has set himself more preparation time for the race this year, competing in the Om Die Dam 50km, which he won in 2:56:33.

He is a three time-winner at the Comrades Marathon, his first in 2014 when he was registered with Nedbank, and his other two coming in back-to-back wins in 2017 and 2018 for his current team Arthur Ford.

International talent

The last non-South African to win the race was Stephen Muzhingi, the Zimbabwean taking three titles in a row between 2009 and 2011, and it seems a tall order to expect anyone other than local runners to take the title.

But regardless, there are those who will be competing. British runner Shane Cliffe has finishers in the Lakes in a Day and The Grand Tour of Skiddaw to his name.

There’s also Simon Brown, who has run the Marathon des Sables and qualified for the cancelled Western States 100 in 2020, and experienced runner and coach Ian Sharman.

by Olly Green

Login to leave a comment

Comrades Marathon

Arguably the greatest ultra marathon in the world where athletes come from all over the world to combine muscle and mental strength to conquer the approx 90kilometers between the cities of Pietermaritzburg and Durban, the event owes its beginnings to the vision of one man, World War I veteran Vic Clapham. A soldier, a dreamer, who had campaigned in East...

more...Nine-time winner of Morocco's "Marathon des sables" race abandons

Shocking news struck the runners of the Marathon des Sables late Thursday (Apr. 27). 9-time winner of the race, Rachid El Morabity threw in the towel a few minutes after being caught red-handed with food in the bag.

The goal of the race is to cover 250 km in 7 days across the Sahara, in food self-sufficiency. Any food provided by a third party is therefore prohibited. But an unannounced control operated in the tent of the Moroccan proved to be positive.

The sanction of the organization was immediate: a penalty of 3 hours sealing the end of the dreams of tenth title for Rachid El Morabity.

He who was aiming to join his compatriot Lahcen Ahansal in the legend of the event. El Morabity's teammate and compatriote, Aziz El Akkad, has decided to abandon.

Rachid El Morabity's younger brother, Mohamed, remains alone at the top of the ranking, 3 minutes 17 seconds ahead of his direct contender Aziz Yachou.

In the women's ranking, French marathoner Maryline Nakache is first, get ahead of Moroccan Aziza El Amrany and Japanese Tomomi Bitoh by 30 minutes.

by Africanews and Pierre Michaud

Login to leave a comment

Marathon Des Sables

The Marathon des Sables is ranked by the Discovery Channel as the toughest footrace on earth. Seven days 250k Known simply as the MdS, the race is a gruelling multi-stage adventure through a formidable landscape in one of the world’s most inhospitable climates - the Sahara desert. The rules require you to be self-sufficient, to carry with you on your...

more...Ultra running is exploding in popularity around the world, but what actually is an ultramarathon?

The term Ultra covers a broad range of races, from mountains to road

Ultra running is fast becoming a mainstream sport. Once, it was the realm of a few crazy runners, and not the pastime of everyone from your boss to your neighbour. But what actually is an ultramarathon?

How long is an ultramarathon?

An ultramarathon is anything longer than a marathon, which is 26.2 miles (42.195km). So, you could complete a marathon and run back to your car and you’ve technically run an ultra distance.

Typically, ultramarathons start at 50km and go up from there. Standard distances are 50km, 100km and 161km (100 miles), the latter often being referred to as a “miler”.

While a marathon is never longer than 26.2 miles, ultras tend to vary a bit. For example, the Hong Kong 100 is in fact 103km. And the Ultra Marathon du Mont Blanc, a miler, is in fact 171km. Others are a bit shorter than advertised, too.

Aside from the above three types, there are ultra races of all sorts of distances and formats. As long as it’s more than a marathon, the distances and formats can be limitless.

An increasingly popular format is 250km split over stages, such as the Marathon Des Sables. Runners complete different distances each day, some less than an ultra, and sleep at night.

As the sport continues to grow, others try to push the boundaries – such as the 298km Hong Kong Four Trails Ultra Challenge, which is non-stop and has no support on the trails. Runners finish the distance in between around 48 and 70 hours.

The formats are becoming increasingly imaginative. A backyard ultra, for example, is around a 6.7km loop. The runners start on the hour every hour until there is just one runner left, so the distance is not set. It keeps going and going. Runners have gone on for more than 80 hours.

Outside organised events, runners often complete ultramarathons just for fun, to set a personal best or a Fastest Known Time (FKT), which is ultra terminology for a specific course record. This can be anything from the 44km Hong Kong Trail, which takes a few hours, to the 4,172km Pacific Crest Trail, which has an FKT of almost two months.

What terrain is an ultramarathon on?

With an infinite range of distances come infinite terrains. An ultramarathon can be road, flat, track, pavement, mountain, trail, snow and more. As long as you can run on it, you can run an ultramarathon on it.

A famous road ultramarathon is the 246km Spartathlon. It follows the legendary route run by Pheidippides, who ran from Athens to Sparta before the Battle of Marathon in Ancient Greece, thus inventing the marathon.

The most high-profile mountain ultra is the Ultra Marathon du Mont Blanc, which has a total of 10,040 metres accumulative elevation gain in the Alps.

Track ultras often take the format of a set time rather than distance. For example, how far you can travel in 24 hours, round and round the same athletics track.

When Zach Bitter set the 100-mile world record, which has since been broken again, he ran it around a 443m track by doing 363 laps.

The distances and terrains are so varied race to race they are essentially different sports. Kilian Jornet is considered one of the best ultra-mountain runners ever, but comparing him with Yiannis Kouros, considered one of the best ultra road runners ever, is like asking who is better at football: Tom Brady or Lionel Messi.

Is an ultra harder than a marathon?

The word ultra refers to the distance, not difficulty. An ultramarathon is inherently hard, but not inherently harder than a marathon or any other distance for that matter.

If you have a specific and demanding finishing time in mind for your marathon, you will have to stick to a specific split, keep your legs spinning and spinning, all the time concentrating on your pace and pushing your body.

Is that easier or harder than a 24-hour 100km over mountains, with variation in terrain and elevation, when you walk some parts and rest at check points?

What about a 5km? If you want to run a fast 5km, you will be at your absolute limit for the entire time and collapse over the finish line.

Non-runners often think an ultramarathon is the “next step” for runners looking for a new challenge. Searching for a faster time is just as challenging as searching for a longer distance.

Either can be harder than the other – it’s down to the runner.

The same is true within ultra running. Ruth Croft, one of the best runners, dominates races around 50km. She was repeatedly asked when she would do a 100 miler once she had “completed” a 50km. Croft resisted the urge to cave to the pressure to run further until she was ready, understanding that fast and far are two often incomparable metrics.

When you consider all of the above, the simple definition of “longer than a marathon” does not quite do justice to the massive range of events encapsulated by the term ultramarathon.

Login to leave a comment

2022 Marathon des Sables Women’s Results

On the women’s side, first-time Marathon des Sables entrant Anna Comet (Spain) was untouchable. Comet ran in a league of her own for the majority of the race, building a lead of up to 53 minutes by the end of Stage 4. Sylvaine Cussot (France) set an equally solid course all week, generally finishing several minutes behind Comet but well in front of the rest of the field, to hold in second place all week.

The gun sounded at the 2022 Marathon des Sables’ fifth and final competitive stage on Friday, April 1. The first finishers broke the tape in the early afternoon, Moroccan local time. The final, noncompetitive Stage 6 takes place on Saturday, April 2.

Thanks to Anna Comet, the 2022 women’s Marathon des Sables was never close. She came into Stage 5 leading by almost an hour, and then broke the tape over an hour before second-place finisher Sylvaine Cussot in the cumulative rankings.

Aziza El Amrany (Morocco) rounded out the podium, a sharp debut performance for this Moroccan breakout runner.

2021 MdS women’s winner Aziza Raji (Morocco) finished fourth and Manuela Vilaseca (Spain) came in fifth.

Bethany Rainbow (United Kingdom) finished sixth as the only other woman to run the race in under 30 hours. She ran a valiant final stage to come in under the gun, finishing just 4:30 behind Comet for second place in the stage.

Login to leave a comment

Marathon Des Sables

The Marathon des Sables is ranked by the Discovery Channel as the toughest footrace on earth. Seven days 250k Known simply as the MdS, the race is a gruelling multi-stage adventure through a formidable landscape in one of the world’s most inhospitable climates - the Sahara desert. The rules require you to be self-sufficient, to carry with you on your...

more...2022 Marathon des Sables Results: Mens

The Sahara Desert’s Marathon des Sables (MdS) is as scorching as it is revered. After an October comeback last year following a 2.5-year COVID-19-induced hiatus, the race returned to Morocco again this March.

Temperatures well above 100 degrees Fahrenheit and plenty of blistering sunshine are hallmarks of the seven-day, 155-mile desert stage race. Finishing it — or simply running in it — is no joke. Each year, race organizers deploy 120,000 liters of water, a support staff numbering in the hundreds, and a wide array of vehicles, aircraft, and even camels to monitor the action and keep runners safe.

Last year, brutal heat and a virulent stomach bug caused an unusually high 40% dropout rate. In this edition, conditions in the field appear somewhat more stable. However, challenging desert weather still wreaked havoc at times throughout the week of racing.

The 2022 Marathon des Sables started with fair weather on Sunday, March 27. But high heat and howling wind beset the race’s second stage the next day. Though only moderately long, Stage 2 also negotiated plenty of steep terrain.

The wild second stage scrambled runners, especially some perennial race favorites. Eight-time MdS winner Rachid El Morabity (Morocco) led the field coming out of Stage 1 but lost 9 minutes during the marathon-length Stage 2. He landed in third place behind his younger brother, Mohamed El Morabity, a first for the pair as Mohamed has finished second in this race four times, and each behind his winning brother. Mohamed maintained his lead — by a razor-thin margin of 37 seconds — through Stage 4 on Wednesday.

Rachid El Morabity stormed back to win, outpacing the rest of the field — and his younger brother — in the race’s final stage. Mohamed led by around half a minute at all checkpoints on Stage 5, but Rachid overtook him late, and then pulled away.

His Marathon des Sables dominance continues — it’s the ninth time he’s won the race.

Mohamed El Morabity played second fiddle yet again. He claimed his fifth runner-up MdS finish all-time.

Aziz Yachou (Morocco) was the only other runner to finish under 19 hours cumulatively. A strong Stage 5, where he took second, left him 4 minutes back of Rachid El Morabity’s week-long pace. This is Yachou’s second MdS effort, and he improved on his fourth-place debut in 2021.

Merile Robert (France) took fourth and missed the podium for the first time since 2017, and Jordan Tropf (United States) took fifth.

Login to leave a comment

Marathon Des Sables

The Marathon des Sables is ranked by the Discovery Channel as the toughest footrace on earth. Seven days 250k Known simply as the MdS, the race is a gruelling multi-stage adventure through a formidable landscape in one of the world’s most inhospitable climates - the Sahara desert. The rules require you to be self-sufficient, to carry with you on your...

more...Running 250 km through the desert: it’s time for the Marathon des Sables

It all started in 1984 when Patrick Bauer (who was 28 at the time) took on a completely self-sufficient 12-day journey across the Sahara Desert, covering 350 km on foot. Two years later the first Marathon des Sables (MDS) was born, with 23 “pioneers” taking on a similar challenge.

Since then, Bauer’s event (he remains the race director) has continued to grow, with a record 1,300 competitors taking part in the 30th-anniversary race in 2015.This year’s race, the 36th edition, will feature 1,100 competitors from 50 countries who will, like the 25,000 athletes who have participated in the event since 1986, take on the 250 km course carrying their food and equipment. Each day race organizers provide the athletes with water and put up a tent for them to sleep under – otherwise they are on their own.

There are five stages in the race, along with a “solidarity” or charity stage that does not count for the overall ranking of the race. The stages range from 30 to 90 km. The athletes don’t know the official course until the day before the race when it is officially announced, but they are guaranteed (according to the event media guide):flat terrain, often hard and stony and suitable for “real runners” as opposed to “trail runners”

sand (sometimes hard or crusted, but most often soft) that they will have to master (for example by opting for shaded areas so they sink less because when the sun heats the sand, it becomes softer)

small, normal and giant sand dunes that will make all competitors draw on their reserves

ascents and descents, not very long but often steep, sometimes sandy, sometimes stony

technical sections over rocky escarpments and along crests (the authentic “trail running moments” of the MDS)

gorges that will provide a beneficial and life-saving shade, when competitors pass through them, and dried wadis (supposedly dried river beds… but some years, a trickle of water is flowing!) where competitors can find some vegetation. The daily temperatures are typically in the 30s, but can rise to as much as 45 degrees Celsius.

At night the temperature can drop to 5 C or less. Athletes must carry a week’s worth of food, a sleeping bag, a compass, knife, lighter, whistle, headlamp, venom extractor, signalling mirror and sunscreen. They are also provided with a GPS beacon so organizers can keep track of the athletes at all times. The race takes place in the middle of the desert so that it can be held in total isolation and guarantees that athletes cannot receive any assistance.COVID-19 and the MDS

Last year’s 35th edition took place last fall after being postponed three times. It was a tough year for the event, with an athlete suffering a cardiac arrest during the first stage, then a gastrointestinal bug ripping through the field, leading almost 50 per cent of the participants to pull out, far higher than the normal 5 to 10 per cent attrition rate the event typically sees.

2022 Coverage

Triathlon Magazine Canada editor Kevin Mackinnon will be on hand to cover this year’s race, one of the 65 accredited journalists covering this year’s MDS. He’ll be providing updates and photo galleries through the first few days of racing in Morocco. There will be 15 Canadians competing at the 2022 MDS. Stay tuned for more from Morocco in the coming days.

by Running Magazine

Login to leave a comment

Marathon Des Sables

The Marathon des Sables is ranked by the Discovery Channel as the toughest footrace on earth. Seven days 250k Known simply as the MdS, the race is a gruelling multi-stage adventure through a formidable landscape in one of the world’s most inhospitable climates - the Sahara desert. The rules require you to be self-sufficient, to carry with you on your...

more...Last Minute Halloween Costumes For Trail Runners

Need something for your kiddo's trick-or-treating? Mandatory office Halloween soiree? First post-covid social engagement? Try one of these easy-to-assemble trail running Halloween costumes!

Basic Trail Bro: Don a Ciele hat, and rock some bright Goodr's with a confusingly non-technical button-up shirt and jorts if you're feeling spicy. BYOB - a super dank IPA (the hazier, the better) swaddled in a coozy you got in a race swag bag. You're probably from Boulder. Or Flagstaff. (Portland variation: add a rain jacket and a slightly better beer.) Make sure to track your trick-or-treat excursion on Strava and don't stop talking about your podcast.

The Courtney: Throw on a tee-shirt and your comfiest basketball shorts and BYO candy corn. Nachos optional.

The Ultra Ultra Runner: Grab your trekking poles, headlamp, gaiters, neck gaiter, waist-light, UPF hat with sunshade, taped-seam windbreaker, sunglasses, clear glasses, 12-liter vest, hip-belt, flasks, bladder, body glide, ramen noodles, gels, spare socks, spare shoes, space blanket, sunscreen, arm sleeves and wind pants. Though you may be dressed like you're about to run the Marathon Des Sables, you could also just be out for a casual jog. You're a human drop-bag: ready for anything.

The Crewmate: Same as above, but carry everything around in your arms the entire night and try to hand everybody you see quesadillas and Skratch.

The Emelie: Grab your S/O and dress entirely in S/Lab, or skimo suits with a babybjorn. Still be faster than everyone.

The Rookie Trail Racer: Grab some long shorts, a sleeveless Nike shirt, and blast the tunes in your Beats By Dre headphones (around your neck, so everyone can hear). Forget the hydration pack, just bring a good ol' Gatorade bottle and be sure to ask everyone "How many miles is 25k????".

The Harvey: Just circle your block 354.2 times while trick-or-treating

Sexy Minimalist Trail Runner: Just split shorts and a handheld. That's it.

The Influencer: This costume is #Sponsored. Flip up the brim of your colorful hat, and snap a pic with your favorite beet-based energy bar or isolated cricket protein, preferably while gazing out at the ocean, or from a summit. Keep your phone and significant other at the ready for any potential photo ops. Bonus points if you have a cute dog who knows a TikTok dance. Make sure all product logos are visible at all times.

Sexy IPOS: Nothing but a gravel bike and KT tape.

The Media Mogul: POV: Your YouTube channel is just about to go viral. Grab your go-pro and lace up your trail runners, because you're about to get a lot of B-roll. Wear a Sony TX90000 BD around your neck, and be sure to periodically change lenses for no particular reason. You're a human steady-cam who'll do anything to get the shot.

The Local Legend: To embody the low-key vibe of the frustratingly-fast unsponsored hometown hero, pull on a of worn-out trail runners and tattered shorts. Wait, is that a Team USA Shirt? Who is this runner? How many FKT's do they have? OOOPS! Someone just stole your CR!

by Trail Runner Magazine

Login to leave a comment

Marathon des Sables Wrapup

After a 2.5-year break due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was with great anticipation that the 2021 Marathon des Sables took place this week. The famous desert race, which runs in the Sahara Desert of Morocco, travels 155 miles (250 kilometers) over seven days, traversing sand dunes and stone-filled plains in an arid climate where mid-day temperatures easily reach 120 degrees Fahrenheit (48 degrees Celsius).

Each day, a mobile bivouac is erected in the desert, which serves as the day’s finish line, campground for the night, and the following day’s starting line. There are six stages total, and five of them are competitive stages. The final stage is an untimed charity stage. Participants must carry their own equipment including food, camping materials, and survival gear along with water rations supplied by the race organization.

Typically, the race takes place in April, which is spring in the Sahara Desert. This October edition was said to be hotter and drier than usual for this race and this time of the year. In addition to the heat, a stomach virus ravaged many of the participants. By the end of the week, dropouts amounted to over 40% of all starters, an unusually high drate for this particular race.

Sadly, the race claimed the life of one runner due to cardiac arrest. The French man, in his fifties, was an experienced ultrarunner who had met the medical requirements necessary to start the race. iRunFar covered this story earlier in the week.

For the first three days of the 2021 edition, it looked like parity might define the race. Moroccan brothers Rachid El Morabity and the younger Mohamed El Morabity ran close together, leading the rest of the men’s field by just minutes. On the women’s side, Morocco’s Aziza Raji held a bigger, but not insurmountable, half-hour lead over Aicha Omrani (France) and Hassna Hamdouch (Morocco) in second and third.

The stage was set for shakeups in the grueling 50-mile Stage 4. However, Raji and the El Morabity brothers were about to render the outcome academic. At the end of Stage 4, just 15 minutes separated Rachid and Mohamed El Morabity from each other in first and second overall — but the rest of the field lagged behind by over an hour. Meanwhile, Raji had built her lead over the women’s field from less than an hour to a mind-boggling four-plus hours.

In the end, Rachid El Morabity took the win, finishing with a time of 21:17:32. Mohamed took a narrow second in 21:32:12, less than 15 minutes behind his older brother. This marks Rachid El Morabity’s eighth win of this iconic sand race, and Mohamed El Morabity’s fourth 2nd place behind his brother.

Merile Robert (France) was the lone non-Moroccan on the men’s podium, a position with which he’s familiar. This marks his fifth Marathon des Sables finish, with his top previous finish also third behind the El Morabity brothers in 2018.

Aziz Yachou (Morocco) took fourth place, less than two minutes out of podium position, in what was an incredible breakout performance. According to his social media, Yachou received an hour’s penalty during the race due to losing an item of his required kit, which makes this podium near miss even more fascinating. (Required kit and the penalties for missing or losing items are clearly communicated by the race organization before the race.)

Mathieu Blanchard (France, lives in Canada) rounded out the top five, though he was a distant two hours and 20 minutes behind fourth place. He said on social media he suffered the stomach virus during Stage 4. Blanchard has had quite the 2021, following up his third place at the 2021 UTMB with this performance.

Notably, 10-time Marathon des Sables winner and Moroccan sand running legend Lahcen Ahansal finished ninth in the age 50-59 category with a time of 38:16:32.

Aziza Raji demolished the women’s field with a winning time of 30:30:24. It was Raji’s first win. She was second at the last edition and had a few top-five finishes before that. She’s only the second Moroccan woman in the history of the race to win it, after two-time women’s champion Touda Didi.

Tomomi Bitoh (Japan) took second in 34:39:17, moving up in the cumulative standings during the 50-mile Stage 4 and marathon-distance Stage 5 through a well-paced week of racing.

Aicha Omrani finished third in 35:47:48; remarkably, she finished the 2011 Marathon des Sables in nearly the double the time it took her finish this edition.

Hassna Hamdouch and Elise Caillet (France) rounded out the top five.

Login to leave a comment

Marathon Des Sables

The Marathon des Sables is ranked by the Discovery Channel as the toughest footrace on earth. Seven days 250k Known simply as the MdS, the race is a gruelling multi-stage adventure through a formidable landscape in one of the world’s most inhospitable climates - the Sahara desert. The rules require you to be self-sufficient, to carry with you on your...

more...Man dies while competing in grueling, multi-day race across the Sahara Desert

An unnamed competitor in the 2021 Marathon des Sables died on Monday, marking the third fatality in the race's 35-year history.

Known as one of the most difficult footraces in the world, the Marathon des Sables takes place each year in Southern Morocco's Sahara Desert. The race covers approximately 250 kilometers (about 155 miles) over a period of about seven days.

Because it exceeds the traditional marathon distance of 26.2 miles, the Marathon des Sables qualifies as an "ultramarathon." The level of prolonged exertion to complete an ultramarathon, particularly when combined with extreme environmental conditions, can take a severe toll on one's body, causing potentially dangerous physical and psychological issues.

The Marathon des Sables reported the tragic incident on Monday, noting that the competitor suffered "cardiac arrest in the dunes of Merzouga" following "a fainting spell."

They added that the man was "in his early 50's and had fulfilled all the medical requirements for the race." He had already completed the first stage of the competition "without the need for medical assistance" at the time of the incident.

"After he collapsed, he was immediately rescued by two other competitors who are also doctors, who triggered the SOS button on his beacon and started the heart massage protocol," said officials from the event.

The Marathon des Sables Medical Director arrived at the site "within minutes by helicopter and took over from the participants." However, despite "45 minutes of resuscitation," the competitor was pronounced dead by medical staff.

The man's identity has been kept secret "out of respect" for his family, who has reportedly been informed of his passing.

Following the incident, Race Director Patrick Bauer broke the news to participants, leaving "staff and competitors...extremely affected."

While the race is planned to continue despite the tragedy, competitors will participate in a minute of silence before the beginning of the third stage.

As noted by The Conversation, ultra-endurance activities put a range of stresses on the body, physically and psychologically. "As growing numbers of competitors look to push themselves to their absolute limit, and [organizers] seek new challenges to enable them to do so, there is always going to be some risk," wrote the publication.

However, "the main cause of death during ultramarathons...is actually sudden cardiac death." Consisting of 43 percent of ultramarathon deaths, these cardiac arrests are usually sustained by those with unknown heart conditions.

Other potential dangers include environmental conditions, psychological stress, sleep deprivation, water and sodium loss and tissue damage.

In order to participate in the Marathon des Sables, competitors must provide "a medical certificate issued by the organization stating their ability to participate and a resting ECG report." Throughout the race, each individual is responsible for providing and carrying their own food, sleeping equipment, and other gear.

by Newsweek

Login to leave a comment

These races are epic and why ultrarunning is soaring in popularity

The events can be gruelling and even dangerous, yet more and more people are signing up

John Stocker hadn’t slept in three-and-a-half days when he finally crossed the finish line after running more than 337 miles in an ultramarathon event in Suffolk, stopping only at brief intervals for food and rest.

Of the 123 people who started the race in Knettishall Heath on 5 June, he was the last person still running 81 hours later on Tuesday evening, and had to summon all of his physical and mental strength to get around the last lap.

“Your tiredness just takes over. And then I clipped my toe and went down on the concrete. I laid there thinking I wasn’t going to be getting back up,” the 41-year-old personal trainer said, as he recovered at home in Bicester. “But the whole reason I do these ultras is to show my kids that they should try to achieve as much as they can, and not be told by anyone that they can’t do something. That’s what kept me going.”

Ultrarunning has soared in popularity, with a report in May showing a 345% increase in participation globally over the past 10 years and thousands of events taking place annually. Meanwhile, participation in 5Ks has declined since 2015, and participation in marathons has levelled off.

The term broadly refers to any race over the length of a marathon, and can come in many shapes and forms – including the six-day, 251km Marathon des Sables across the Sahara, and the Spine Race across the Pennine hills covering 431km.

“It has been an explosion. When I came to ultrarunning about 14 years ago, I did a Google search and found about 60 races. Now we estimate there’s probably about 10,000,” said Steve Diedrich, the founder of the website Run Ultra. “The pandemic put people into two categories: the people who sat on the couch and the people who got off the couch. And those who got off the couch have pushed themselves further and become ultrarunners.”

Adharanand Finn, the author of The Rise of the Ultra Runners, said: “Generally as running has got more popular and more people have done marathons there’s a natural inflation. To tell people you’ve run a marathon is maybe not as impressive as it once was.

“These races are so epic and so huge, people are so impressed and it’s easy to get sucked in by that.”

The UK has a long history of ultrarunning in the form of fell races, but races specifically labelled as ultras are on the increase. The “back yard challenge” races, which originated in the US, are particularly gruelling; at the Suffolk event participants had to run a 4.167-mile (7km) route every hour until they could no longer carry on. If runners complete their lap early they can take a short break to sleep, eat and use the toilet before heading back to the start line.

“It’s like Groundhog Day. Because you get back to the tent and you’ve got a few minutes and then all of a sudden it’s your next loop, it starts all over again,” said Stocker. “I still have nightmares now of them blowing the whistle over and over again.”

Along with his fellow runner Matthew Blackburn, he beat the world record for the event previously held by Karel Sabbe, a Belgian dentist who ran 312.5 miles (502km) in 75 hours in October. Now the pair will head to Tennessee to take part in the back yard ultra world championships and compete against the best in the field.

The races are not without risk. The ultrarunning community is still reeling from the deaths of 21 runners in an ultramarathon event in China last month after high winds and freezing rain hit the course. The country has suspended all long-distance races and an investigation into the tragedy is being carried out.

“Through the history of ultraracing there have been issues with floods, cold exposure, heat exposure, a range of everything depending on the location,” but deaths are very rare, said Diedrich. In its 35-year history, two people have died taking part in the Marathon Des Sables.

“We have to have some sort of a safety net, because you’re asking people to push to the absolute limit of their exhaustion,” said Lindley Chambers, the owner of Challenge Running, which organised last week’s Suffolk back yard ultra. He said the route was carefully mapped out to avoid risk of injury and staff were on hand to aid runners at all times.

“You need to be sensible, and manage the risks as best you can,” he said. “But then on the other side, the runners want it to feel like an adventure, they want to feel like they’re challenged. They don’t want you to hold their hand all the way round.”

Login to leave a comment

HOW ULTRARUNNER TOM EVANS ESCAPES HIS COMFORT ZONE

The ultrarunner started his sporting career for a bet, and discovered a love of pushing his limits that has kept him moving ever since.

“My thought process can best be described as ‘minimal’,” laughs Tom Evans, describing his 2017 entry into the six-day, 251km Marathon des Sables, held annually in the Sahara Desert. As well as being possibly the toughest race on the planet, it also happened to be Evans’ first. “I knew it was the hardest race out there, and I thought there was no point in doing the easy ones,” he says. “I’d jump straight in at the deep end.”

Though he lacked any formal training, Evans’ self-belief carried him to an unbelievable third place – the fastest time run by any European in the race’s history – and, naturally, skyrocketed him into the world of professional ultrarunning. “I was always sporty,” explains the 29-year-old. “I represented England at rugby, hockey and athletics events while at school. Looking back, I wasn’t necessarily the best, but I always tried the hardest. After school, I realised I didn’t want to go to university, so at 18 I joined the army. I’d always felt I had something to prove, and in the army an easy way to do that was by keeping fit. The army is an endurance-based organisation, which suited me really well.”

After the Marathon des Sables, Evans capped off a successful streak by winning the 101km CCC race at the 2018 Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc. The following year, he left the army to pursue running full-time, and he hasn’t looked back. Next on his schedule is Red Bull’s official charity partner event the Wings for Life World Run on May 9 – a unique race with no finish line, in which runners compete against a ‘catcher car’ until it overtakes them. This year’s participants will still compete at the same time, but – due to COVID-19 restrictions – they’ll run against a virtual car, via an app.

It’ll be different from Evans’ past experiences at the annual event, but he’s a master of adaptability. Currently holed up in Loughborough with his fiancée, professional triathlete Sophie Coldwell, he’s keeping busy by switching snowy trails for road running and has even smashed the Three Peaks challenge on a treadmill. Here’s how Evans keeps pushing forward...

The Red Bulletin: You came third in the Marathon des Sables after entering for a bet. How?

Tom Evans: My friends did [the race] in 2016 and finished in the top 300. I thought I could do better, and over a few beers they bet me I couldn’t. I signed up the next morning. There’s a lot of crossover with the military, because you’re sleeping outside under the stars and pushing yourself to your limits every day. Through running the race, I discovered this ability to suffer for a very long time in the heat. Two years later, I left the army to become a full-time professional athlete.

Ultrarunning is one of the most punishing sports. Is it all down to this natural ability?

No, I train very hard and I get used to suffering. I know in any race there will come a point when I’ll want to stop. When I get there it’s like, ‘Right, I knew it was going to happen, so now’s the time to embrace it, but also know that the minute after you stop, it’s going to stop hurting.’ I think I can withstand a lot, but I want to know how long I can actually keep feeling uncomfortable for.

Many people struggled to find focus during lockdown. What kept you motivated?

It’s very easy to keep a habit once you have it, but it’s very difficult to start the habit in the first place. I think people go from never running at all to loving it. Then there’s the other side of that: as soon as you do stop something like running, it’s very difficult to start again. So, for me, it’s about keeping as much consistency as possible. I always set mid-term and long-term goals – I’m very goals-based. Having gone from boarding school to the military, I like knowing what I’m doing.

Typically I drive to the Peak District or Snowdon or the Lake District, where there are phenomenal trails, but I wasn’t able to do that in lockdown. So I started running from my door instead. Road running suits me well, because it’s easier to collect data on your run. You don’t have to pigeonhole yourself into a certain distance or event. I run because I love running, and it’s a brilliant thing to be able to do.

What’s your plan for the Wings for Life World Run?

Because it’s a charity event, my goal is to raise as much awareness for spinal cord research as I possibly can by putting in a performance that people talk about. It’s going to be a long, uncomfortable run, which is my sweet spot. I think the best way people can physically prepare is to go on the website and play around with speeds; look at how far you can get [while] running at a certain pace. Because it’s on the app, you can challenge your friends virtually, which keeps the competition alive.

Login to leave a comment

Over Half Of Ultrarunners Get Nauseous During Races; Here's Why

The list of issues and injuries that an ultrarunner can face while racing is lengthy. Blisters, chafing, cramps, muscle strains, knee pain, heat illnesses, and altitude sickness are just a handful of the possibilities. Perhaps none of these potential problems, however, are as prevalent and impactful during ultramarathons as nausea and vomiting. Indeed, practically every ultrarunner has their own tale of yakking on the side of a trail or into an aid station trashcan. For some, it's an unlucky one-off event, but for others, recurrent nausea consistently mars their ability to perform up to their expectations.

The reason so many ultrarunners get stricken with nausea is undoubtedly multi-faceted, and to be honest, there is not a cut-and-dry singular explanation. Still, we do have some clues as to why the prevalence of nausea and vomiting is up to 2-3 times more common in these races than much shorter distances. Let's take a look at what the research says about the possible culprits as well as some of the strategies you can try to deal with this troublesome symptom.

Just How Common Is Nausea?

Beyond the anecdotes, what exactly do we know about the prevalence of nausea in ultrarunners? Before we get to some data on that question, it's important to recognize that surveys used to gather this information quantify nausea differently. In addition, the occurrence of nausea is likely to vary with temperature and humidity, elevation, and the length of a race. As such, it's a bit foolhardy to throw out a single estimate of nausea and think that it applies to every ultrarunning scenario.

Caveats aside, some of the relevant data tells us that nausea incidence clearly increases with race duration. Dr. Martin Hoffman, professor emeritus in the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at the University of California, Davis, has overseen several studies on this topic, and in some cases, up to 6 out of 10 runners experience nausea during an ultramarathon. To give you some perspective, consider that around 10% of regular marathoners typically suffer from nausea.

Now, some of these cases of nausea are quite mild or transient, meaning they won't hurt performance much. Still, up to half of cases can be severe enough to impact ultrarunning performance. In fact, one of Hoffman's investigations found that nausea or vomiting was the leading reason for racers to drop out of the Western States 100-mile Endurance Run. During a regular 26.2-mile marathon, a runner suffering from nausea near the end of the race is likely to grit their teeth and finish. In contrast, the thought of having to suffer for another 20, 30, or 50-plus miles while feeling queasy is, very understandably, too much for some ultrarunners to cope with.

Multiple Causes

The puzzle of why nausea is so common during ultrarunning is difficult to solve, in large part because there are multiple physiological changes occurring simultaneously over the course of an ultrarace. It's also incredibly tough to match the demands of an ultrarace in a laboratory, so mechanistic studies looking at the origins of nausea during super-prolonged exercise are few and far between.

Even with the scientific uncertainty, we do have some decent guesses as to what's provoking the urge to spew in so many ultrarunners. During prolonged exercise, you secrete hormones like adrenaline and glucagon into your blood that allow your body to liberate fat stores, make glucose, and maintain your blood sugar levels. Arginine vasopressin, a fluid-conserving hormone, is also released so that you can reduce urine production. Blood levels of endotoxins (sort of invader molecules that seep through your gut's walls) and inflammatory molecules can also surge. And finally, you've got muscle breakdown products, like urea and creatine kinase, spilling into your bloodstream. All these substances can stimulate what's called the chemoreceptor trigger zone in your brainstem, which communicates with another brain region called the vomiting center.

Long story short, you've got a cocktail of substances circulating in your bloodstream that act as a potent trigger for nausea. The concentrations of all these substances tend to increase over time during prolonged exercise, which may help to explain why nausea becomes much more common in the latter half of ultraraces.

A Nervous Gut

The release of stress hormones like adrenaline can also occur even before you take your first official stride during an ultra. Throughout the history of sport, many athletes have been plagued by precompetition anxiety severe enough to induce vomiting. Bill Russell, perhaps the best center of all-time in the sport of basketball, reportedly vomited before many of his big games. There's also a moment in the Steve Prefontaine biopic Without Limits that perfectly captures what prerace nerves can do to even the most elite athletes. In the scene, Prefontaine is seen puking under the grandstands before his race against other running greats like Frank Shorter and Gerry Lindgren, even as the crowd chants his name.

These anecdotal accounts are also beginning to be backed by research. Just this year, two of my colleagues and I published an investigation that found anxiety to be associated with the occurrence of nausea in endurance race competitors. The study, published in the European Journal of Sport Science, had 186 endurance-trained individuals document their life stress and anxiety as well as the gut symptoms they experienced during one of their recent races. A subset of the subjects also reported how anxious they felt on race morning. Ultimately, racers who reported higher levels of general anxiety had over three times the odds of experiencing significant levels of nausea during competition. Further, those who reported lots of anxiety on race morning had over five times the odds of experiencing substantial in-race nausea.

These are correlations, so it's hard to definitively prove that these athletes' nausea issues were completely due to anxiety. That said, other lines of evidence support the idea that this relationship is at least partially cause and effect. Plus, most of us have had our own out-of-sport run-ins with gut distress stemming from worries and anxieties, whether they be from a first date, a medical procedure, or an interview.

Sweltering Heat and Altitude

Environmental conditions also play a major role in development of nausea during ultras. Some of the most prominent ultramarathons in the world (e.g., Western States Endurance Run, Badwater Ultramarathon, Marathon des Sables) are held in sweltry conditions. When researchers ask runners to exercise in the heat, the incidence of nausea can quadruple in comparison to exercise carried out at the same intensity in more mild conditions.

Besides the heat, another environmental factor that many ultrarunners deal with is altitude. Nausea is a well-known symptom of acute mountain sickness, with written accounts going back at least several hundred years. Add exercise to the mix, and you can start to understand why nausea is a big issue for competitors at races like the Hardrock 100 and the Khardung La Challenge, which has the highest elevation of any ultrarace in the world.

Fueling: A Delicate Balance

One other notable contributing factor to nausea is in-race fueling. The nutritional demands of ultrarunners can far outpace those of other athletes competing at shorter distances. For those ultrarunners who are looking to push the boundaries of what their bodies can do, they might end up consuming carbohydrate at rates of 60-90 grams per hour. That's roughly equivalent to 3-4 sport gels per hour! Even lesser amounts of carbohydrate (30-60 grams per hour), though, can pose a significant challenge to the gut's capacity to digest and absorb fueling.

In short, fueling during an ultramarathon often takes place on a knife's edge. Too little can lead to a bonk and even nausea if your blood sugar gets too low, while too much foodstuff can also provoke the gut and induce queasiness. With that in mind, it's critical that ultrarunners practice their fueling strategies multiple times throughout the weeks leading up to a race. Ideally, at least some of these gut-training sessions would be done at a pace similar to race-pace and in similar environmental conditions that an athlete expects to compete in.

Strategies to Quell or Avoid Nausea

Given all this information, you might be wondering how to best avoid the nauseous fate of so many ultrarunners. First, you should accept the fact that there is likely no ironclad way to completely eliminate the risk of nausea during an ultra. There are just too many potential causes. That being said, you do have the power to minimize your risk of being stricken with severe nausea. And for some athletes, it will be important to take a multi-pronged approach as opposed to relying on a single strategy. Below are my top five tips for reducing the odds of tossing your cookies during your next ultra.

Acclimate to the heat and altitude if your race is held under those conditions. Likewise, employ cooling strategies (e.g., drinking cool beverages, putting some ice in your cap or shirt, dousing yourself with cool/cold water, etc.) throughout a race that's held in sweltering conditions.

If you suffer from prerace nerves, try techniques like slow deep breathing or mindfulness. Better yet, consult with a sports psychologist.

Avoid both overhydrating as well as underhydrating. During a single-stage ultramarathon, some amount of weight loss is normal (due to the loss of energy stores), so you shouldn't be drinking so much that you weigh the same or more after a race as before the race. On the other hand, large body mass losses (e.g., >5%) may be a sign that you're underhydrating.

Train your gut! If you plan to push the boundaries of food and fluid intake during the race, of course it makes sense that you should practice your nutrition plan during some of your longer training runs. Much like other organs in your body, the gut is adaptable.

Try ginger. I'm generally not a purveyor of supplements, but if the above mentioned strategies don't do the trick for you, there is at least one nutritional product that has shown some anti-nausea properties in settings outside of exercise: ginger. To be specific, these anti-queasiness effects have been most often studied in nausea occurring during pregnancy, motion sickness, and chemotherapy. No supplement is without risk, and many products sold in the U.S. are of questionable quality, so anyone looking to use ginger supplements-or any other supplement for that matter-should do their research and consult with their healthcare provider as well.

by Trail Runner Magazine

Login to leave a comment

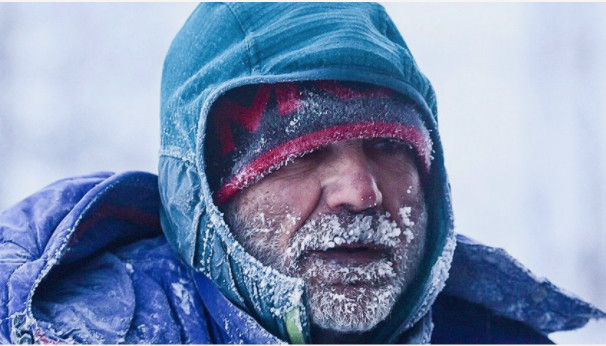

The Cold, Hard Reality of Racing the Yukon Arctic Ultra

Temperatures were brutally low at this year’s running of the 300-mile competition, and one frostbitten competitor may lose his hands and feet. Is this just the price of playing a risky game, or does something need to change?

Roberto Zanda left the Carmacks checkpoint of the Montane Yukon Arctic Ultra just before noon on February 6. He was at least 150 miles into the 300-mile race—he’d already been slogging down a dogsled trail through the Yukon backcountry for more than five full days. Temperatures had plunged below minus 40 Fahrenheit on the first night out of Whitehorse, the small Yukon city where the race began; along the race course, temperatures consistently ranged from the minus 20s to the minus 40s.

In short, conditions were brutal. Of the eight racers who’d begun the 100-mile version of the variable-length event, just four had finished. Of the 21 who’d started the 300-miler, only the 60-year-old Zanda and two others remained. Most of the rest had scratched with frostbite or hypothermia.

When Zanda left the checkpoint, hosted in a village rec center, a race medic wrote on the event’s Facebook page that the racer had paused only for “a short rest and a big meal. He was looking very strong.”

Just over 24 hours later, Zanda was in a helicopter, being rushed to Whitehorse General Hospital with hypothermia and catastrophic frostbite, lucky to be alive. He now faces the likely amputation of both hands and both feet. What went wrong?

This was the 15th running of the Yukon Arctic Ultra, an annual race in which competitors choose their distance—marathon, 100 miles, 300 miles, or, every second year, 430 miles—and their mode of transportation: a fat bike, cross-country skis, or their own booted feet. Race organizer Robert Pollhammer, 44, who runs an online gear store in his native Germany, started the event in 2003 after being involved with Iditasport, a similar event on the Alaskan side of the border.

The Yukon race takes place on part of a trail built each year by the Canadian Rangers for the Yukon Quest, a 1,000-mile dogsled race, and it’s as much a feat of logistics as it is an athletic contest. It’s continuous, not a stage race; competitors are self-sufficient, carrying all their camping and survival gear, spare layers, food, and water in sleds they pull behind them. Temperatures are cold enough to kill, and it’s dark for roughly 14 hours every day. Nonetheless, eager ultra racers travel from around the world for the event, paying anywhere from $750 to $1,750 USD to enter (depending on when they register and the distance they’re attempting), plus the cost of flights, hotel, and gear. The total can easily add up to $5,000 or more.

The entrants tend to be experienced ultra and adventure racers; many athletes have already completed events like the Gobi March or the Marathon des Sables. Most competitors come from Europe, although this year’s race also saw entrants from South Africa and Hong Kong. The race organization offers a survival course a few days beforehand—a crash education in moisture management, layering, and cold-weather injuries. Generally speaking, the racers are accomplished athletes, but they may not have extensive experience with severe cold. The challenge lies in keeping themselves safe while moving through the Yukon’s remote, frigid backcountry.

The race is billed as “the world’s coldest and toughest ultra,” and there have been plenty of serious injuries before: flesh blackened by frostbite, frozen skin peeling off racers’ faces like wax, and bits of fingers and toes lost to amputation. But what happened to Zanda is by far the worst medical outcome yet, and it has shocked former racers, event organizers, and fans. It has also led to discussions and debates, often heated, about where a race organization’s responsibilities end and a racer’s personal assumption of risk begins.

As Zanda moved out of Carmacks, his Spot tracker showed him clipping along steadily at around three miles per hour. Between 3 p.m. and 9 p.m., his beacon’s transmissions became more erratic—but that’s fairly normal in the Yukon, where satellite signals can be weak or inconsistent. Between 9 and 10 p.m., the problem cleared up and the Spot began sending signals every few minutes.

The last blip came in at 10:08 p.m., at route mile 189.7, and then the device went into sleep mode. After a strong ten-hour, 25-mile push from Carmacks, Zanda appeared to have stopped to camp for the night.

In the morning, as the sun rose, his tracker still hadn’t moved. The race crew wasn’t concerned yet—Zanda had taken a 12-hour rest once before during the race, as had some other athletes. At 9:32 a.m., Pollhammer posted on Facebook that two volunteer trail guides were headed out to check on him. “His Spot has not been sending for a long time now. Once we have news I will let you all know.”

The trail guides are the race’s safety net, patrolling hundreds of miles by snowmobile to check on the athletes and, when necessary, evacuate them from the course. They motored down the trail toward Zanda’s Spot location, but when they got there, in late morning, they found only the racer’s harness and sled, loaded with a tent and sleeping bag, a stove and fuel, and—crucially—the Spot device. Zanda was gone.

They called back to Pollhammer, who contacted the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and then they began searching the area, looking for some sign of where the racer might have left the packed trail and wandered into the forest. The Mounties were about to launch a search of their own when the call came in: Zanda had been found. A helicopter was dispatched and landed near him. The trail guides, advised by the incoming medical team, did what they could to care for Zanda while they waited. As Pollhammer put it in an email to me: “No time was lost.”

A few days later, Zanda spoke to a Canadian television reporter from his hospital room in Whitehorse. He wore a pale-green gown, and his hands were heavily bandaged, nearly up to his elbows. His feet and shins were the same. He said he’d left his sled behind to go look for help because his feet were freezing up. He and his family members have also told race organizers that Zanda had lost the trail and went in search of the next marker, leaving the sled behind while he scouted.

Hypothermia must have already had Zanda in its grip by then, muddying his mind and compromising his decisions. His sled was his lifeline, containing everything he needed to stay alive and the only tool he had to call for help. He wandered through the cold and dark all night while the sled sat on the trail, sending out a reassuring beacon to the world that all was well.

I competed in this year’s Yukon Arctic Ultra—my first attempt—and I didn’t last long. Twenty-two hours in, suffering from frostbite on three fingertips, I scratched from the event, one of four 100-mile racers who decided to quit.

I never met Zanda, though for all I know we could have been standing side-by-side at the start line. On the afternoon of day one, he left the first checkpoint 19 minutes ahead of me. That night, I passed by as he bivied on the side of the trail. A couple hours later, I put up my own tent, crawled inside, and was trying to change into dry clothes with my hands briefly exposed. That was long enough for frostbite to set in.

Early the next morning, Zanda and two other racers passed my tent. I heard them go by but didn’t call out. I was waiting until daylight to push the help button on my Spot. I’ve thought about those encounters a lot since I learned about what happened to Zanda. It’s impossible not to hear his story and ask: Could that have been me?

Easily. I knew when I signed up for the race that amputations, or even death, were among the potential consequences. At such low temperatures, exhausting yourself to the degree required to complete an ultramarathon is a good way to erase whatever thin margin of safety you’ve managed to create. But while some of my friends had concerns, I wasn’t really worried. That disconnect is what allows many of us to put ourselves in these situations.

Zanda wasn’t the only person hospitalized. Nick Griffiths, another 300-mile racer, scratched on day two. The frostbite on his left foot had become severe by the time he was whisked from the trail to a remote checkpoint for eventual evacuation to Whitehorse. Griffiths spent five days in the hospital, and he will eventually lose his big toe and two others next to it. (To preserve as much healthy tissue as possible, doctors will allow the toes to “self-amputate,” meaning that the dead tissue will simply fall off.) Losing the big toe, in particular, could have a serious impact on Griffiths’ future ability to walk, hike, and run.

“I’m hoping I’ll be all right,” he told me from his home in England, where he’s been reading up on athletes who’ve lost toes. “I’m not expecting to be able to go and do ultras or things like that, but there’s other challenges. It’s not ideal, but there’s no point jumping up and down about it. It’s done.”

I’m not sure I could muster the same acceptance if I were in Griffiths’ position, let alone Zanda’s. Understandably, the Italian racer’s friends and family are extremely upset. In the days after his rescue, the race’s Facebook page filled up with furious comments from people demanding to know how this could have happened, why Zanda wasn’t checked on sooner, why the race hadn’t been canceled entirely when the weather refused to relent. Zanda’s wife, Giovanna, wrote, in Italian, “It’s been too many hours before you decided to verify what happened. He didn’t die by miracle.” His brother, Paolo, posted, “Why they promise you safety when they do not care about you?” To which Pollhammer replied, “Nobody promises safety.”

That much is certain. The waiver I signed when I filed my registration paperwork last summer listed the risks I was assuming as including but not limited to “dehydration, hypothermia, frostbite, collision with pedestrians, vehicles, and other racers and fixed or moving objects, sliding down hills, overturning of ice-rocks, falling through thin ice, avalanche, dangers arising from other surface hazards, equipment failure, inadequate safety equipment, weather conditions, animals, the possibility of serious physical and/or mental trauma and injury, including death.”

Still, even as we sign our lives away, participating in an organized race may provide us with an illusion of safety in a way that an independent backcountry trek might not. If so, I suppose it becomes our job to tear down that illusion and make clear-eyed choices about the risks. That’s easier said than done, of course.

Throughout the aftermath of this year’s race, Pollhammer has remained calm as he answered his critics, walking the fine line of showing empathy for Zanda and his family while making it clear that he believes the error was the racer’s. Initially he seemed shaken, unsure about running the event again next year, but he has since announced the 2019 dates. I asked Pollhammer if, with the benefit of hindsight, he would do anything differently. He said that the rules and safety procedures evolve almost every year, and next year will likely be no different. But there are limits to what he can do, no matter how much he tweaks his protocols

“We can increase the list of mandatory gear, make people carry a sat phone, warn athletes even more so than we do now,” Pollhammer said. “We can do many things. However, we won’t be able to make sure people don’t get hypothermic and start making mistakes when they are out there. It they don’t act, or if they act too late, it will always mean trouble. I wish I could take that away from them, but it is impossible.”

Or as Nick Griffiths put it, “I can’t blame anybody for it—it was my own fault.”

As for Zanda, he told the CBC that he’ll be back out racing again—on prosthetics, if need be.

Login to leave a comment

Yukon Artic ultra 300 miler

The Yukon Arctic Ultra is the world's coldest and toughest ultra! Quite simply the world's coldest and toughest ultra. 430 miles of snow, ice, temperatures as low as -40°C and relentless wilderness, the YUA is an incredible undertaking. The Montane® Yukon Arctic Ultra (MYAU) follows the Yukon Quest trail, the trail of the world's toughest Sled Dog Race. Where dog...

more...Ultrarunner Tom Evans prepares for his biggest race at Olympic marathon trials

Like many, ultrarunner Tom Evans has struggled with the lack of races in lockdown. The former army captain burst onto the ultrarunning scene in 2017, coming third in the six-day Marathon des Sables, and last year he set a new record in the Tarawera 102km Ultra Marathon, in New Zealand. But he has had to adapt to circumstances and is now setting his sights on the marathon in the rescheduled Tokyo Olympics.

We talked to the 29-year-old about swapping the trails for the pavements, his mental strength, the Olympic marathon trials and his role as a Garmin ambassador.

You’ve set your sights on the Tokyo Games. How did this happen?

‘At the beginning of the pandemic, Tokyo was not on my list whatsoever – I very much planned on staying on the trails and running long rather than running fast. I guess what the pandemic has taught me is that I like structure and I’m a very goal-orientated athlete and person. I have to have goals, whether it’s “Today I’m going to list 10 things on eBay” or something bigger; I have to set goals and achieve those goals. It’s the same with my running, with there being so little opportunity to race, I thought I need something to set my sights on and if something is going to happen, it’s going to be the Olympics.