Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #Western States

Today's Running News

Americans Jim Walmsley and Katie Schide Win Trail Running World Championship Titles

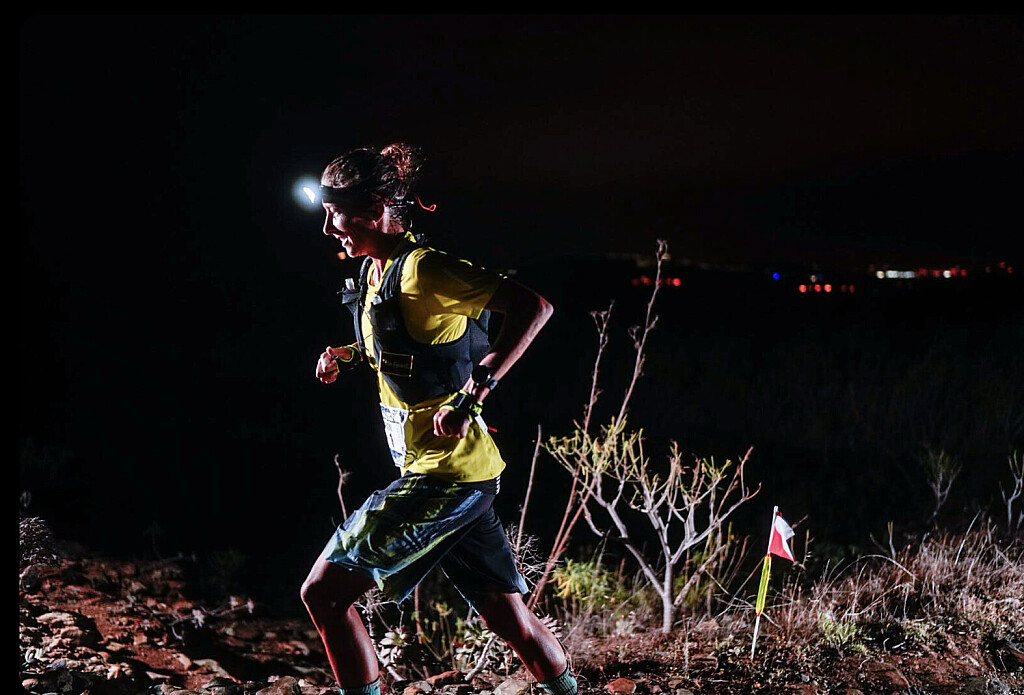

Canfranc, Spain — September 27, 2025. It was a historic day for U.S. trail running in the Pyrenees as Jim Walmsley and Katie Schide stormed to victory in the Long Trail race at the 2025 World Mountain and Trail Running Championships. Both dominated the grueling 50.9-mile course that packed in nearly 17,750 feet of elevation gain and loss across technical, mountainous terrain.

Walmsley’s Men’s Triumph

Walmsley, already celebrated as one of the best ultra runners of his generation, played his cards perfectly. After running with France’s Benjamin Roubiol and Louison Coiffet through the opening stages, he surged clear just past 47 km. By the 70 km mark he had carved out a commanding lead and never looked back.

He broke the tape in 8:35:11, more than ten minutes ahead of Roubiol and Coiffet, who shared silver in 8:46:05. For Walmsley, who became the first American man to win UTMB in 2023, this victory further cements his legacy as the standard-bearer for U.S. trail and ultra running.

Schide’s Commanding Performance

On the women’s side, Katie Schide delivered a masterclass in front-running. She built a gap of 38 seconds within the first 4 km, stretched it to five minutes by 25 km, and by the halfway point was nearly 20 minutes ahead of her nearest rival.

Schide crossed the finish in 9:57:59, winning by more than 25 minutes. Already a champion of UTMB, Hardrock, and Western States, her latest triumph adds a world title to a résumé that ranks among the most impressive in the sport.

A Landmark for U.S. Trail Running

Together, Walmsley and Schide showcased American dominance on one of the world’s toughest stages. Their wins highlight not only physical endurance and technical skill but also tactical brilliance and unwavering mental strength.

For fans and fellow athletes alike, their victories in the Pyrenees are a reminder of what’s possible when preparation meets opportunity on the world stage.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

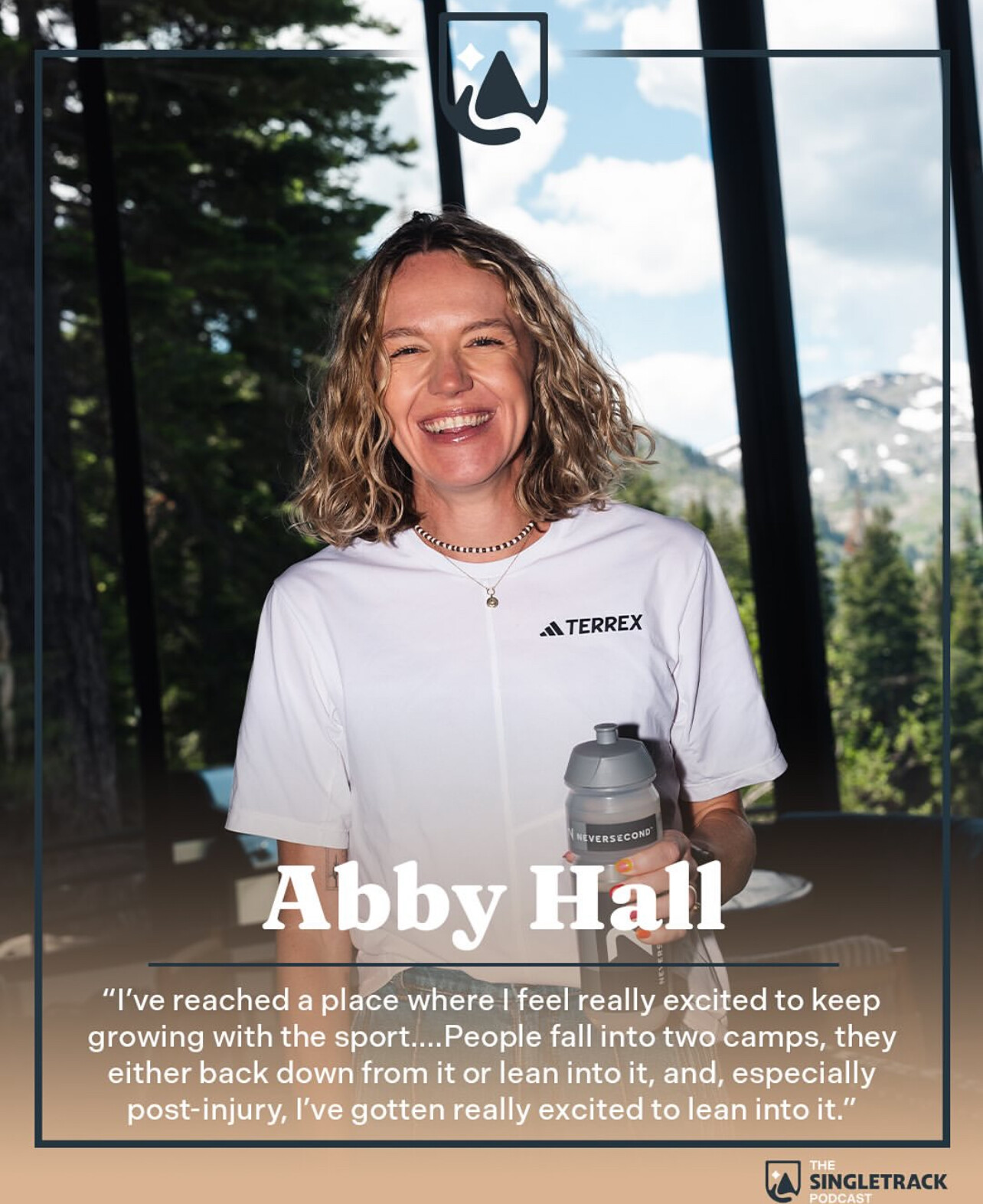

Abby Hall Claims Fairytale Victory at 2025 Western States 100 After Golden Ticket Surprise

In a race defined by resilience, heat, and high drama, Abby Hall delivered one of the most emotional and triumphant performances in Western States Endurance Run history, winning the women’s race at the 52nd edition of the world’s oldest and most iconic 100-mile trail event.

Hall, who just months ago wasn’t even on the start list, crossed the finish line at Placer High School in 16 hours, 37 minutes, and 16 seconds, recording the fourth-fastest women’s time in race history. Her victory marks a stunning return to form after years of injury setbacks and a last-minute Golden Ticket entry.

A Storybook Build-Up to the Start Line

Hall’s journey to Western States was anything but straightforward. After a lengthy recovery from a serious knee injury, the American ultrarunner returned to form with a win at Ultra-Trail Kosciuszko by UTMB in December 2024. But a Golden Ticket to Western States proved elusive.

She finished fifth at the Black Canyon Ultras, narrowly missing an automatic entry. However, fate intervened when a pregnancy deferral by fellow runner Emily Sullivan caused the Golden Ticket to roll down—giving Hall an unexpected but welcome shot at redemption.

“It was such a beautiful passing of the baton,” Hall shared on Instagram. “I’m so inspired watching an incredible athlete like Emkay enter this new season of her life as she becomes a mother.”

How the Race Unfolded

Hall made her intentions clear early, leading through the Escarpment checkpoint at mile 4. Although she was briefly overtaken, she reclaimed the lead shortly after mile 60 and never looked back.

Facing fierce competition from Fuzhao Xiang (CHN)—who finished second last year—Hall maintained a steady and commanding pace through the canyon heat, where temperatures reached 104°F (40°C). With 10 miles to go, she held a 10-minute lead over Xiang, and that gap remained virtually unchanged to the finish.

Xiang once again finished runner-up, clocking 16:47:09, while Marianne Hogan (CAN) surged late in the race to secure third in 16:50:58, overtaking Ida Nilsson (SWE) in the final miles. Fiona Pascall (GBR) rounded out the top five.

2025 Western States 100 – Women’s Results

June 28, 2025 | 100.2 miles

1. Abby Hall (USA) – 16:37:16

2. Fuzhao Xiang (CHN) – 16:47:09

3. Marianne Hogan (CAN) – 16:50:58

4. Ida Nilsson (SWE) – 17:00:48

5. Fiona Pascall (GBR) – 17:21:52

Hall also placed 11th overall, finishing just behind many top men’s competitors in one of the deepest fields in race history.

A Career-Defining Moment

This was Hall’s second appearance at Western States—her first came in 2021, when she finished 14th. Her return this year wasn’t just about redemption; it was a masterclass in determination, patience, and execution.

“It’s surreal,” Hall said at the finish. “This race has meant so much to me for so long. To be back here, to be healthy, and to be crossing that line first—it’s everything.”

The Global Rise of Women’s Ultrarunning

With five nations represented in the top five, the 2025 women’s race showcased the global depth and diversity of talent in ultrarunning. From Xiang’s technical brilliance to Hogan’s consistency and Nilsson’s enduring grit, this was a race that highlighted how far the women’s field has come—and how fast it continues to get.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

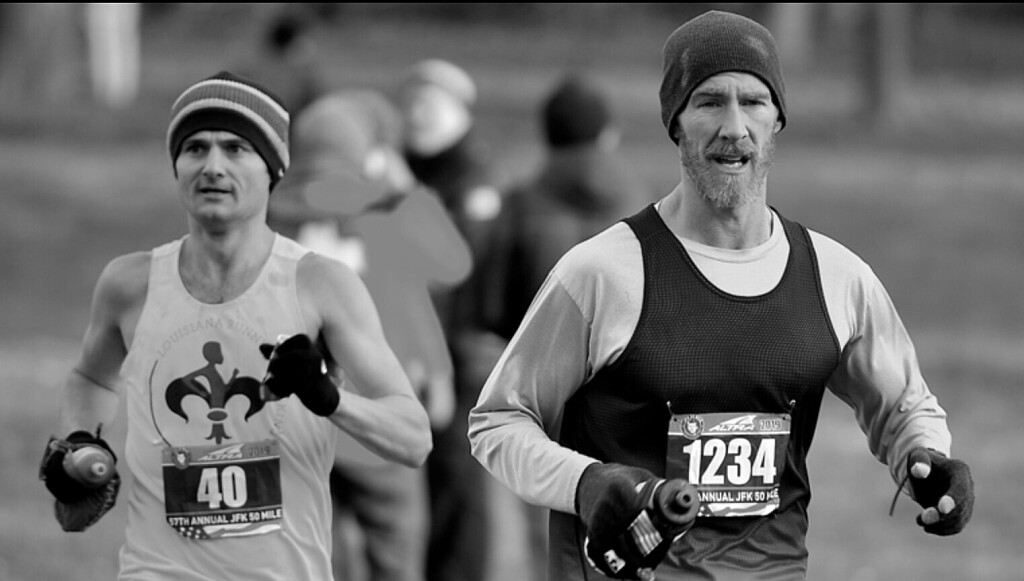

Caleb Olson Stuns the Field with Breakthrough Win at the 2025 Western States 100

American ultra-trail runner Caleb Olson delivered a career-defining performance at the 2025 Western States Endurance Run, emerging as the surprise champion in what was billed as one of the most competitive editions in the race’s 52-year history.

The 29-year-old from Salt Lake City conquered the infamous 100-mile (161-kilometer) course through Northern California’s rugged Sierra Nevada mountains, finishing in 14 hours, 11 minutes, and 25 seconds—just two minutes shy of Jim Walmsley’s legendary course record set in 2019 (14:09:28). Olson’s time is now the second-fastest ever recorded at Western States.

His win comes just a year after a strong fifth-place finish in 2024 and cements his place among the top ranks of global ultrarunning.

A Battle of Heat, Elevation, and Grit

The race began at 5:00 a.m. in Olympic Valley, with runners quickly climbing to the course’s highest point—2,600 meters (8,600 feet)—before descending into the heat-scorched canyons. Snowfields in the early miles gave way to punishing heat, as temperatures soared to 104°F (40°C) in exposed sections of the trail.

Despite the brutal conditions, approximately 15 elite athletes crested the high point together, setting the stage for a tactical and attritional race. Olson surged to the front midway, clocking an average pace near 12 kilometers per hour and never relinquished his lead.

Elite Field Delivers Drama

Close behind Olson was Chris Myers, who battled stride-for-stride with the eventual winner for much of the race before taking second in 14:17:39. It was a breakthrough performance for Myers, who has been steadily climbing the ultra ranks.

Spanish trail running legend Kilian Jornet, 37, finished third, matching his 2010 result. Returning to Western States for the first time since his win 14 years ago, Jornet hoped to test himself against a new generation on the sport’s fastest trails. Though renowned for his resilience in mountainous terrain, he struggled to match the frontrunners during the course’s hottest sections.

“Western States always finds your limit,” Jornet said post-race. “Today, that limit came earlier than I’d hoped.”

Rising Stars and Withdrawals

Among the elite field was David Roche, one of America’s most promising young ultrarunners, who was forced to withdraw after visibly struggling at the Foresthill aid station (mile 62). Roche had entered the race unbeaten in 100-mile events.

“I’ve never seen him in that kind of state,” said his father, Michael Roche, who was on hand to support him. “This race just takes everything out of you.”

Roche’s exit was a reminder that, even with perfect preparation, the Western States 100 is as much about survival as speed.

The Lottery of Dreams

Held annually since 1974, the Western States Endurance Run is more than a race—it’s a pilgrimage. With only 369 slots available, most runners enter via a lottery system with odds of just 0.04% for first-timers. Elite athletes can bypass the lottery by earning one of the coveted 30 Golden Ticketsawarded at select qualifying races each year.

For many, getting to the start line takes years of qualifying and persistence—making finishing the race an achievement in itself.

Olson’s Star Ascends

Before this landmark win, Caleb Olson was already on the radar of the ultra community. He had logged top-20 finishes at the “CCC”—a 100-kilometer race associated with the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc series—and had demonstrated consistency in major trail events.

Saturday’s victory vaults him into the upper echelon of global ultrarunners and marks a generational shift in the sport.

“I’ve dreamed of this moment,” Olson said at the finish. “Today, everything came together—the training, the heat management, and the belief. This is why we run.”

2025 Western States results

Men

Saturday June 28, 2025 – 100.2 miles

Caleb Olson (USA) – 14:11:25

Chris Myers (USA) – 14:17:39

Kilian Jornet (SPA) – 14:19:22

Jeff Mogavero (USA) – 14:30:11

Dan Jones (NZL) – 14:36:17

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

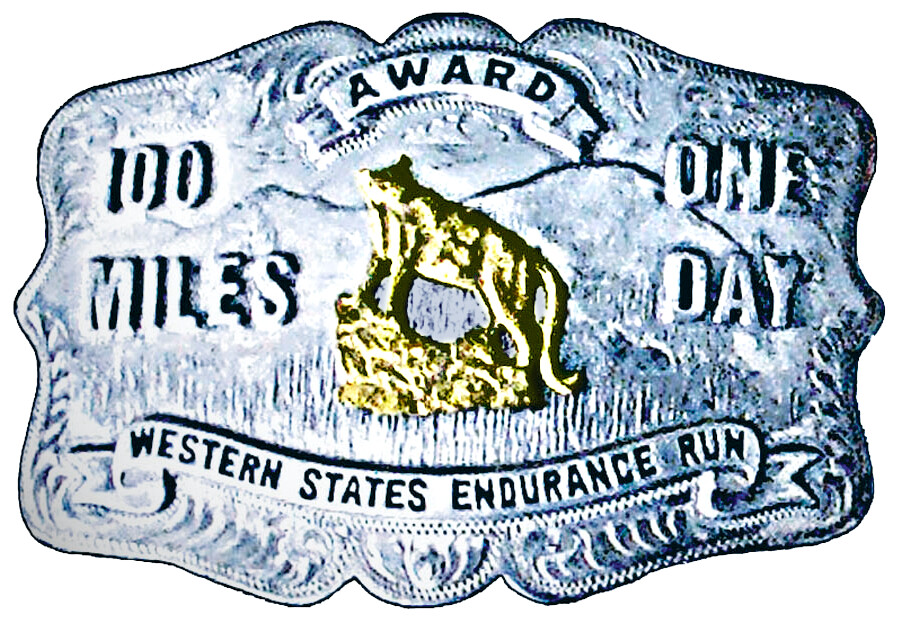

Western States 100

The Western States ® 100-Mile Endurance Run is the world’s oldest and most prestigious 100-mile trail race. Starting in Squaw Valley, California near the site of the 1960 Winter Olympics and ending 100.2 miles later in Auburn, California, Western States, in the decades since its inception in 1974, has come to represent one of the ultimate endurance tests in the...

more...Western States 100 Gears Up for an Epic Showdown Across Sierra Trails

The legendary Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run returns June 28–29, 2025, promising one of the most competitive and compelling editions in its storied history. Known as the world’s oldest 100-mile trail race, this ultra begins in Olympic Valley (formerly Squaw Valley) and finishes 100 rugged miles later at Placer High School in Auburn, California.

With more than 18,000 feet of climbing and 23,000 feet of descent, the race tests every aspect of a runner’s will and endurance. From snow-capped ridges to sweltering canyon floors, the course traverses remote backcountry, river crossings, and punishing climbs—all under the clock, with the coveted silver belt buckle awaiting those who finish under 24 hours.

Who’s Racing?

This year’s field is packed with elite talent, resilient veterans, and powerful storylines.

Top Men’s Contenders:

• Rod Farvard (USA) – One of the fastest Golden Ticket winners this season.

• Dan Jones (New Zealand) – Former Olympic Trials marathoner.

• Caleb Olson (USA) – Rising talent on the ultra scene.

• Chris Myers (USA) – Strong performances across the trail circuit.

• Jia-Sheng Shen (China) – Brings international prestige to the field.

Leading Women:

• Emily Hawgood (Zimbabwe) – Regular top-10 finisher with unfinished business.

• Eszter Csillag (Hungary) – One of Europe’s most consistent mountain runners.

• Heather Jackson (USA) – Former pro triathlete turned ultra star, back after a win at Unbound Gravel XL.

• Fu-Zhao Xiang (China) – Dominant at multiple global ultras.

• Ida Nilsson (Sweden) – Former European mountain running champion.

Notable Golden Ticket Winners:

• Riley Brady, Hannah Allgood, Rosanna Buchauer, Hậu Hà, Tara Dower, Abby Hall, Lin Chen, Caitlan Fielder, Nancy Jiang, Fiona Pascall, Johanna Antila

A Field That Crosses Generations

One of the most heartwarming developments this year is the record-setting six athletes aged 70 or older toeing the line.

Among them is Jim Howard, a two-time Western States champion (1981, 1983), who is making an inspiring return at age 70—running with two artificial knees. “I want to go out there one more time and be part of this incredible race,” Howard told Canadian Running.

Also returning is Jamil Coury, founder of Aravaipa Running, looking to build on his strong performance 15 years ago.

The Course

• Start: Olympic Valley (elevation: ~6,200 ft)

• Highest Point: Emigrant Pass (~8,750 ft)

• Finish: Auburn (elevation: ~1,200 ft)

• Snow is often a factor in the early miles, with extreme heat common in the canyons. Aid stations are spaced roughly every 4–8 miles, supported by over 1,500 volunteers.

Runners cross rivers, climb ridgelines, descend technical single-track, and are cheered into the stadium at Placer High—often in the dead of night.

Media and Spectator Access

• Live coverage, tracking, and video will be available on the Western States Endurance Run website.

• Key aid stations will allow crew and spectators, including Foresthill (mile 62) and Robie Point (mile 99).

A Race Like No Other

• One of the five races in the Grand Slam of Ultrarunning

• A UTMB World Series qualifier

• Historic, grassroots feel with world-class competition

Whether you’re cheering for a podium contender, an age-defying legend, or simply following the passion of runners determined to finish within 30 hours, this year’s Western States 100 is poised to deliver drama, beauty, and inspiration.

Let the countdown begin.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Western States 100

The Western States ® 100-Mile Endurance Run is the world’s oldest and most prestigious 100-mile trail race. Starting in Squaw Valley, California near the site of the 1960 Winter Olympics and ending 100.2 miles later in Auburn, California, Western States, in the decades since its inception in 1974, has come to represent one of the ultimate endurance tests in the...

more...The GOAT Returns: Courtney Dauwalter Takes on the Cocodona 250 Mile Ultra

Courtney Dauwalter, widely regarded as one of the greatest ultrarunners of all time, is set to take on the formidable Cocodona 250—a 250-mile ultramarathon stretching from Phoenix to Flagstaff, Arizona. This grueling race, commencing at 5 a.m. PT on Monday, May 5, 2025, marks her first race over 200 miles since 2020 .

Born on February 13, 1985, in Hopkins, Minnesota, Dauwalter’s athletic journey began with cross-country skiing, where she became a four-time state champion during high school. She continued her athletic pursuits at the University of Denver on a cross-country skiing scholarship and later earned a master’s degree in teaching from the University of Mississippi in 2010 . Before turning professional in 2017, she taught middle and high school science in Denver.

Dauwalter’s ultrarunning career is marked by remarkable achievements. In 2023, she became the first person to win the Western States 100, Hardrock 100, and the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB) in the same year . Her victories often come with record-breaking performances, showcasing her exceptional endurance and mental fortitude.

The Cocodona 250 is a point-to-point race that challenges runners with diverse terrains, including desert landscapes, mountainous trails, and significant elevation changes. For Dauwalter, this race presents an opportunity to explore new limits. “I haven’t run a race over 200 miles since 2020,” she noted, highlighting the significance of this endeavor .

Her preparation for Cocodona has been promising. She began her 2025 season with a victory at the Crown King Scramble 50K, indicating strong form leading into this ultramarathon .

A distinctive aspect of Dauwalter’s approach is her embrace of the “Pain Cave,” a term she uses to describe the mental space where she confronts and overcomes extreme physical challenges. She visualizes it as a place to “chip away” at her limits, finding growth through adversity.

Unlike many elite athletes, Dauwalter eschews strict training regimens and coaching, opting instead for an intuitive approach that prioritizes joy and curiosity. Her philosophy centers on listening to her body and finding happiness in the process, which she believes enhances performance.

Courtney Dauwalter’s journey from a science teacher to an ultrarunning icon serves as an inspiration to athletes and non-athletes alike. Her achievements demonstrate the power of resilience, mental strength, and a passion-driven approach to pursuing one’s goals.

As she embarks on the Cocodona 250, the ultrarunning community watches with anticipation, eager to witness another chapter in the extraordinary career of this remarkable athlete.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

One Mile or One Hundred The Battle for the Soul of the Mile in 2025

In 2025, the word “mile” carries very different meanings depending on who’s lacing up their shoes. For some, it’s about blistering speed—the chase for a personal best in an all-out sprint lasting just a few intense minutes. For others, it’s about endurance, grit, and surviving a 100-mile ultramarathon—not once, but four times in one season. While one version of the mile is measured in minutes, the other is measured in days, elevation, and blisters.

Both forms of running are surging in popularity, drawing passionate athletes and growing crowds. But which “mile” speaks to you?

The Rise of the Road Mile

The road mile is back in the spotlight. Once overshadowed by the 5K and 10K, this short, intense race has re-emerged as a fan favorite. In cities across the U.S. and around the world, runners are lining up for high-stakes, high-speed showdowns that test both speed and tactical racing smarts.

One of the most iconic examples is the New Balance 5th Avenue Mile in New York City. Scheduled for Sunday, September 7, 2025, this legendary event draws elite professionals, masters athletes, and youth competitors for a one-mile drag race down Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue. With the skyline as a backdrop and cheering crowds lining the route, it offers one of the purest expressions of speed in road racing.

“It’s raw, it’s electric, and it’s over before you know it,” said one competitor who’s raced both marathons and the mile. “The road mile demands absolute precision—whether you’re aiming to break five minutes or six, you don’t get time to recover from a tactical mistake.”

Events like the Guardian Mile in Cleveland and the Grand Blue Mile in Iowa have followed suit, offering prize money, flat courses, and the kind of short-format excitement that appeals to both spectators and athletes. The mile, once seen as a track-specific discipline, has truly found a home on the road.

The Grand Slam of Ultrarunning

At the other extreme lies the Grand Slam of Ultrarunning—one of the sport’s most grueling and prestigious challenges. Often confused online with terms like “mile grand slam” due to the cumulative 400 miles of racing, the official name is simply The Grand Slam.

To earn this distinction, runners must complete four of the oldest and most iconic 100-mile trail races in the United States during a single summer. The core races typically include:

• Western States 100 (California)

• Vermont 100 Mile Endurance Run

• Leadville Trail 100 (Colorado)

• Wasatch Front 100 (Utah)

Some years permit substitutions like the Old Dominion 100, depending on scheduling. Regardless of the lineup, the difficulty is staggering: thousands of feet of elevation gain, brutal cutoffs, altitude, heat, and sleep deprivation.

“To finish one 100-miler is an accomplishment,” said a veteran ultrarunner who’s completed the Slam. “To finish four in under 16 weeks—there’s nothing like it. It’s not about speed. It’s about survival, strategy, and heart.”

Since its formal inception in the 1980s, fewer than 400 runners have completed the Grand Slam—a testament to its difficulty and prestige.

Two Extremes, One Shared Spirit

At first glance, these two uses of the word “mile” couldn’t be more different. One is sleek and fast; the other is rugged and long. One ends before your legs even start to ache; the other pushes your limits for an entire day—and night.

But at their core, both disciplines require the same fuel: dedication, discipline, and the courage to test yourself. Whether it’s the final lean in a road mile or the final climb at mile 96 of a trail race, runners in both arenas are chasing something personal—and powerful.

Final Thought

So what does the mile mean in 2025? For some, it’s a tactical burn over 1,760 yards. For others, it’s the slow, steady march of 100 trail miles—repeated four times. Either way, the mile remains one of the sport’s most meaningful measures of challenge.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

How Trail Races Are Redefining the Running Boom

In recent years, the global running community has seen a dramatic shift in where and how people race. While traditional road marathons still draw massive crowds, trail races—once considered a niche segment—are experiencing a surge in popularity. From rugged mountain paths to dense forests and desert crossings, more runners are lacing up to compete off-road, seeking challenge, solitude, and a deeper connection to nature.

The Rise of Trail Runnimg

Trail running has grown rapidly in the past decade, but its momentum accelerated after the COVID-19 pandemic, when road races were canceled and people turned to nature for both fitness and sanity. What started as necessity turned into passion for many, and race organizers took note. Events that once attracted a few hundred now sell out in minutes.

Today, races like the UTMB (Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc) in France, the Western States 100 in California, and the Ultra-Trail Cape Town in South Africa are globally recognized—drawing elites and amateur runners alike. These races offer not just distance and competition, but elevation, terrain variety, and breathtaking backdrops.

More Than a Race—A Journey

Unlike a typical 10K or marathon, trail races often require navigation, climbing, and mental fortitude. Weather and terrain can change quickly. Aid stations may be miles apart. But it’s exactly these demands that attract runners hungry for something deeper than just speed or medals.

“There’s something primal about running in the wilderness,” says 2023 UTMB finisher Sara Delgado. “It’s not just about pace—it’s about presence.”

Elite Trail Runners on the Rise

Top road racers are taking notice too. Marathoners like Jim Walmsley and Kilian Jornet have made trail dominance a core part of their legacy. Meanwhile, athletes like Courtney Dauwalter are redefining what endurance looks like, regularly winning 100-mile races overall—not just in the women’s field.

Sponsors have followed the talent. Major brands are investing in trail running gear, shoes, and media coverage, making the sport more visible and viable for elite athletes and growing its appeal for weekend warriors.

Global Appeal

From Portugal’s Douro Valley to the jungles of Costa Rica and the peaks of Japan’s Alps, trail races are being launched in every corner of the world. Many combine local culture with intense landscapes, turning these events into destination experiences.

Travel-based trail running adventures—3-day stage races, run-and-yoga retreats, and culinary trail tours—are also gaining traction. It’s no longer just a race, but a way to see the world, one footstep at a time.

What This Means for the Future

Trail running is redefining the running boom by offering what many road races cannot: quiet, challenge, authenticity, and unfiltered connection to the earth. As the sport continues to grow, it’s likely we’ll see more hybrid athletes, crossover races, and increased visibility across the media.

The road will always have its place, but for a growing number of runners, the real race begins where the pavement ends.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

The Last Push Before Summer: How Runners Are Peaking This Spring

As the calendar turns toward May, runners across the globe are entering a crucial phase in their annual training cycles: the final opportunity to race hard and fast before summer heat shifts the strategy.

While many spring races are just wrapping up—or happening this weekend—runners are still chasing personal bests and season goals. The London Marathon, Madrid Marathon, and Big Sur International Marathon are all set for this Sunday, capping off one of the most exciting stretches of the global racing calendar.

But the season isn’t quite over yet. The Eugene Marathon, Vancouver Marathon, Pittsburgh Marathon, and other early May events are giving runners one more shot to test their fitness—and many are taking full advantage.

A Critical Window for Speed and Strategy

“This is one of the best times of year to be fit,” says Coach Dennis from KATA Portugal. “Runners who stayed healthy through the winter and peaked for April races are now sharper than ever. If you can handle one more race effort, this is the time to go for it.”

Late April and early May offer ideal racing weather in much of the Northern Hemisphere. Cool mornings and calm conditions are perfect for PRs, BQ attempts, or one last tune-up before switching into base-building mode.

The Spring Surge Continues

The Eugene Marathon (April 27) and BMO Vancouver Marathon (May 4) are both known for fast, scenic courses and well-organized race weekends. They attract everyone from local club runners to elites trying to salvage a qualifying time or simply end the spring on a high note.

“My goal race is Berlin this fall, but Eugene gives me a mid-year checkpoint,” says California-based runner Mallory James. “If I’m not racing now, I’m falling behind.”

Time to Recover—or to Launch

Some runners will use May for recovery after a hard season. Others—especially those gearing up for summer trail and mountain races—are just now hitting their peak mileage. Events like the Dipsea, Mt. Washington Road Race, and Western States 100 are fast approaching.

Coach’s Tip: Plan Your Summer Wisely

According to KATA coach and 2:07 marathoner Jimmy Muindi, spring is where momentum is built—but summer is where runners evolve. “If you raced well this spring, great. Now shift the focus to long-term strength. Summer is for building, not burning out.”

Whether you’re racing this weekend or logging miles toward your fall marathon, this is your moment to finish strong—and set the tone for everything that comes next. As the calendar turns toward May, runners across the globe are entering a crucial phase in their annual training cycles: the final opportunity to race hard and fast before summer heat shifts the strategy.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Des Linden Announces Retirement From Professional Marathoning

2018 Boston Marathon Champion Eyes Ultra Distances as Her Next Frontier

Des Linden, one of America’s most celebrated distance runners and the 2018 Boston Marathon champion, has announced she is retiring from professional marathoning. Known for her grit, longevity, and no-nonsense approach to the sport, Linden is not stepping away from running altogether. Instead, she’s setting her sights on a new challenge—ultramarathons.

Linden, 40, made the announcement with characteristic clarity, emphasizing that while her days competing at the highest level in the marathon are behind her, her passion for endurance running is far from over. “The chapter on professional marathoning is closing,” she said, “but the book isn’t finished.”

Her victory at the 2018 Boston Marathon remains one of the most iconic moments in U.S. distance running history. Battling freezing rain and headwinds, Linden surged through the elements to become the first American woman to win Boston in 33 years. That win elevated her status from elite competitor to running legend.

But Des has always been more than just one win. She’s represented the U.S. on the Olympic stage twice (London 2012, Rio 2016), placed second at the 2011 Boston Marathon, and has run more than 20 career marathons under 2:30. Her steady pacing, resilience, and loyalty to the grind have made her a fan favorite for over a decade.

In recent years, Des has hinted at her evolving interests in longer distances. She famously broke the women’s 50K world record in 2021, clocking 2:59:54—becoming the first woman to run sub-3:00 for the distance. That performance gave a glimpse of what might be next.

Now, with her professional marathoning career officially behind her, Linden plans to explore the world of trail and ultra running. “There’s something pure and raw about ultras,” she said. “It’s about effort, persistence, and the long game—things I’ve always loved about running.”

Linden’s legacy is already cemented, but her next chapter promises to be just as compelling. Whether it’s the Western States 100 or Comrades, fans can expect to see the same toughness and authenticity that made her a household name in the marathon world.

From Boston’s heartbreak hill to the rugged climbs of ultramarathon courses, Des Linden’s journey continues—just at a longer distance.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Kilian Jornet is The Laid-Back Legend of the Mountains and Ultramarathons

Kilian Jornet is one of the most decorated endurance athletes in history, yet you wouldn’t know it from speaking with him. He carries his accolades with a shrug and a smile, displaying the kind of calm confidence that comes from years of pushing human limits at extreme altitudes and distances. Whether he’s setting records on towering peaks or dominating the world’s most grueling ultramarathons, Jornet approaches every challenge with an almost playful ease.

Breaking Records in the Mountains

Jornet’s list of accomplishments reads like something out of a mountaineering legend’s biography. He holds the fastest known time (FKT) for ascent and descent of some of the world’s most iconic peaks, including Mont Blanc, the Matterhorn, and Denali. His 24-hour uphill skiing record—a staggering 23,864 meters (78,312 feet) of elevation gain—stands as a testament to his extraordinary endurance.

For Jornet, mountains aren’t just a competitive arena; they are home. Growing up in the Pyrenees, he was introduced to skiing and mountain running at an early age. By his teens, he was already an elite ski mountaineer, but his ambitions stretched far beyond the competition circuit. He set his sights on redefining speed and endurance in the world’s most rugged terrains.

Dominating Ultramarathons

Beyond mountaineering, Jornet has excelled in ultramarathons, often obliterating world-class competition. His wins include victories at:

• Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB) – Arguably the most prestigious ultramarathon in the world, where Jornet has claimed multiple titles.

• Hardrock 100 – He’s won this brutally tough race in Colorado multiple times, including running it with a dislocated shoulder in 2017.

• Western States 100 – A race where his performance cemented his status among the world’s best ultrarunners.

• Zegama-Aizkorri Marathon – A mountain marathon in the Basque Country where he has thrilled fans with record-breaking runs.

Jornet’s dominance is not just about physical strength. His ability to read the mountains, understand his body, and adapt to extreme conditions gives him an almost supernatural edge.

The Mindset of a Champion

Despite his mind-blowing achievements, Jornet remains humble. When asked about his records, he often downplays them, focusing instead on the experience rather than the numbers. His approach to training is unconventional by traditional standards—he listens to his body, adapts his workouts based on how he feels, and prefers to spend as much time as possible in the mountains rather than following rigid training plans.

This laid-back mindset might seem at odds with his high-performance results, but it’s exactly what makes him great. He thrives in uncertainty, adapting in real time and trusting his instincts rather than fixating on data.

Looking Ahead

Jornet continues to push boundaries, not just in racing but in exploring human potential in extreme environments. His recent projects have included minimalist alpine expeditions and self-supported endurance challenges rather than traditional competitions. He is also an advocate for environmental sustainability, working to preserve the mountains he loves.

At 36 years old, Jornet is still redefining what’s possible in endurance sports. Whether he’s racing, breaking records, or simply enjoying a day in the mountains, he remains one of the most inspiring athletes the world has ever seen.

For those who dream of reaching their own endurance goals, there’s a lesson to be learned from Jornet: approach every challenge with passion, stay adaptable, and never lose sight of the joy that brought you to the sport in the first place.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

How Did Courtney Dauwalter Get So Damn Good?

If Courtney Dauwalter could travel back in time, this is what she would do: She’d join a wagon train crossing the American continent, Oregon Trail-style, for a week, maybe more, just to see if she could swing it. It would be hard, and also pretty smelly, but Dauwalter wonders what type of person she’d be if she deliberately decided to take that journey. Would she stop in the plains and build a farm? Could she make it to the Rocky Mountains? How much suffering could she take, and how daunted might she be by the terrain ahead of her?

“If you get to Denver and this huge mountain range is coming out of the earth, are you the type of person who stops and thinks, ‘This is good’?” she wonders. “Or are you the person who’s like, ‘What’s on the other side?’ ”

Dauwalter is probably (definitely) the best female trail runner in the world—a once-in-a-generation athlete. She’s hard to miss at the sport’s most famous races, and not just because of the nineties-style basketball shorts she prefers. (Her explanation: she just likes them.) It’s because she’s often running among the leading men in the sport, smiling beneath her mirrored sunglasses. The 39-year-old is five foot seven and lean, with smile lines and hair streaked with highlights from abundant time spent in high-altitude sun.

Dauwalter shared her historical daydream with me while sipping a pink sparkling water at her house in Leadville, Colorado, after a four-hour morning training run. Her cross-country wagon musings get at why she’s the best female ultrarunner ever to live: Dauwalter is curious. She’s curious about pain, about limits, about possibility. This quality is fundamental to what makes her so good.

Over the past eight years, Dauwalter has won almost everything she’s entered. In 2016, she set a course record at the Javelina Jundred—an exposed, looped route through the Sonoran Desert of Arizona. That same year she won the Run Rabbit Run 100-miler in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, by a margin of 75 minutes, despite experiencing temporary blindness for the last 12 miles (she could only see a foggy sliver of her own feet). Because of ultrarunning’s huge distances, it’s not unheard of to beat the competition by so much, but it doesn’t happen with the frequency that Dauwalter manages.

In 2018, she won the extremely competitive Western States 100 in California; it was her first time on the course. A year later, she set a new course record while winning the prestigious Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB), besting the second-place finisher by just under an hour. In 2022, she set the fastest known time on the 166.9-mile Collegiate Loop Trail in her backyard in Colorado, and she won (and set a new course record at) the Hardrock 100, a grueling high-altitude loop through the state’s San Juan Mountains.

Dauwalter is also one of the few runners of her caliber to seriously dabble in the really long distance races. In 2017, she won the Moab 240—yes, that’s 240 miles—in two days, nine hours, and fifty-five minutes, ten hours ahead of the second-place finisher. She ran even farther at Big’s Backyard Ultra in 2020, a quirky test of wills where athletes complete a 4.167-mile course every hour on the hour until only one runner is left. Dauwalter set a women’s course record of just over 283 miles.

Given everything she’s accomplished, it’s hard to believe that the past two summers have been her most successful yet. In 2023, she returned to Western States, where she smashed the women’s course record by more than an hour and finished sixth overall. When she passed Jeff Colt, who finished ninth, he remembers how calm and collected she looked, running all alone. “My pacer looked back at me and said, ‘Jeff, I can’t even keep up with her right now,’ ” he says. Less than three weeks later, she won Hardrock again, taking fourth place overall and setting a new women’s course record. The race changes direction on the looped course each year, and she now holds both the clockwise and counterclockwise records.

In the interest of testing herself one more time, in late August she traveled to France to run UTMB again. She won that race too, becoming the first person in history to win all three races in a single summer. “She’s one of those humans who defy even the concept of an outlier,” says Clare Gallagher, a former Western States winner who has raced against Dauwalter. “I look at her summer and I have no words. It’s truly hard to conceptualize.”

Dauwalter led UTMB from the start, and she finished more than an hour ahead of the woman in second place. As she descended the final stretch of trail, she was followed by a barrage of cameras and a handful of people who looked like they just wanted a bit of her magic to rub off on them. As crowds roared on either side of the finish line in Chamonix, she looked back at the spectators and clapped in their direction, never raising her hands above her head or pumping her fists in the air. After hugging her parents and her husband, 39-year-old Kevin Schmidt, she jogged back in the direction she’d just come to high-five hundreds of fans.

Dauwalter grew up in the suburbs of Minneapolis, in a tight-knit family that was always active. The kids all played soccer, and when they weren’t at practice they were busy building tree forts or making up games at the local park. In seventh grade, she started running cross-country, and in eighth grade she joined the nordic ski team. She claims to have spent the first years just trying to stay upright, but in high school she went on to be a four-time state nordic ski champion and attended the University of Denver on a cross-country-skiing scholarship. She says that her parents, who now frequently crew and support her at races, led by example. “You work hard, you give everything you’ve got, you don’t forget to have fun,” she says.

Minnesota winters are notoriously cold, and she credits her ability to dig deep within herself to the unforgiving conditions. “Growing up there, you just learn to do stuff, regardless of the weather,” she says. She also points to a cross-country coach who taught her to think differently about pain. “He laid the groundwork for understanding that our bodies are capable of so much,” she says. “We can push past those initial signals saying that’s all I have and turn the knob, and there’s always one more gear.”

After college, Dauwalter taught middle and high school science in Denver, which is where she met Schmidt. “A woman I worked with and a guy he worked with were married, and they just kept putting us in the same places,” she says. “I didn’t know they were meddling!” Schmidt, who works as a software engineer, is also a competitive runner. He and Dauwalter train together—sometimes he’ll join in for her second run of the day—and they trade off supporting each other during races. When I met up with them in Leadville, Dauwalter had just finished crewing for Schmidt at a 100-miler in Switzerland. During her races, he maps her splits, takes care of her aid-station needs, and serves as crew captain. He’s the “spreadsheet brain” to her “tie-dye brain,” as he puts it, and he provides emotional support too.

“Its clear to me when she has taken up residence in the pain cave, so I try my best to fill it with snacks and encouragement,” says Schmidt. One time, while driving to an aid station during a race, Schmidt got a flat tire while carrying everything Dauwalter needed for the night. He wound up sprinting the final three miles to catch her in time.

When Dauwalter started racing more competitively and winning, she and Schmidt had a series of discussions about what they wanted their lives to look like. Ultimately, they decided that she should try to give professional running a shot. In 2017, without a sponsor and with a lot of unknowns still ahead, she left teaching to run full-time. “What we wanted was to look back when we were 90 years old and not wonder what if? about anything,” she says.

Mike Ambrose, the former team manager at Salomon, offered Dauwalter her first sponsorship as a trail runner that same year. She was still new on the scene, but Ambrose could see that she was driven, and the talent was there. “She’s super curious about pushing herself,” he says. “She had this huge engine coming from nordic skiing, and her 24-hour time was really crazy. I thought, well, if she just figures it out and gets more trail experience, she obviously has the mental and physical capacity.”

Despite her nearly superhuman athleticism and mental fortitude, Dauwalter is also very normal. She likes nachos, candy, and beer. She watches sports (the Vikings are her NFL team, even though she’s been in Broncos territory for years), and she wants to spend time with the people she loves, including her parents, and the friends who often crew for her.

Ultrarunning frequently sees short-lived stars, runners who dominate for a couple of years before burning out or slowing down, either from overtraining or simply from the passage of time and the wear on their bodies. Dauwalter, however, seems to have a rare capacity to push against her own limits without tipping over the edge. She’s been running long distances at an elite level for seven years now. Gallagher wonders how she’s managed to avoid injury, given Dauwalter’s volume of physically demanding races.

Login to leave a comment

Hayden Hawks Named 2024 UltraRunner of the Year

Hayden Hawks has been named the 2024 UltraRunner of the Year, cementing his status as one of the most accomplished athletes in ultrarunning. The recognition comes after a stellar season highlighted by victories in some of the world’s most prestigious ultra-distance races.

The Cedar City, Utah native delivered standout performances, including a victory at the Courmayeur-Champex-Chamonix (CCC) 101K on Mont Blanc. Known as one of the toughest races in the Ultra-Trail World Tour, the CCC is a proving ground for elite ultrarunners, and Hawks’ 10:20:11 finish solidified his dominance on the global stage.

He also claimed victory at the highly competitive Black Canyon 100K in Arizona, where he not only won but set a new course record with a time of 7:30:18. His season was rounded out with podium finishes at races like the Western States 100, where he placed third in 14:24:31, and the Julian Alps Ultra-Trail in Switzerland, where he finished second.

Hawks lives in Cedar City with his wife, Ashley, and their two children. Balancing a demanding training schedule with family life, he credits his support system for his success, calling his family his “greatest motivation.”

Hawks’ achievements in 2024 highlight his versatility across different terrains and conditions. Whether racing on the mountainous trails of Europe or the arid landscapes of the American West, Hawks has consistently demonstrated his ability to adapt and excel. His Black Canyon course record and CCC triumph underscore his speed, endurance, and tactical prowess.

As the 2024 UltraRunner of the Year, Hayden Hawks has not only etched his name into the sport’s history but also inspired countless runners worldwide to push their limits. With a career that continues to rise, the running community eagerly awaits what 2025 will bring for this ultrarunning star.

Login to leave a comment

The Distance Running Scene in 2024: A Year of Remarkable Achievements

The global distance running scene in 2024 was marked by incredible performances, new records, and innovative approaches to training and competition. From marathons in bustling city streets to ultramarathons through rugged terrains, the year showcased the resilience, determination, and evolution of athletes from all corners of the globe.

The World Marathon Majors—Tokyo, Boston, London, Berlin, Chicago, and New York—continued to be the centerpiece of elite distance running, each event contributing to a year of unprecedented performances and milestones.

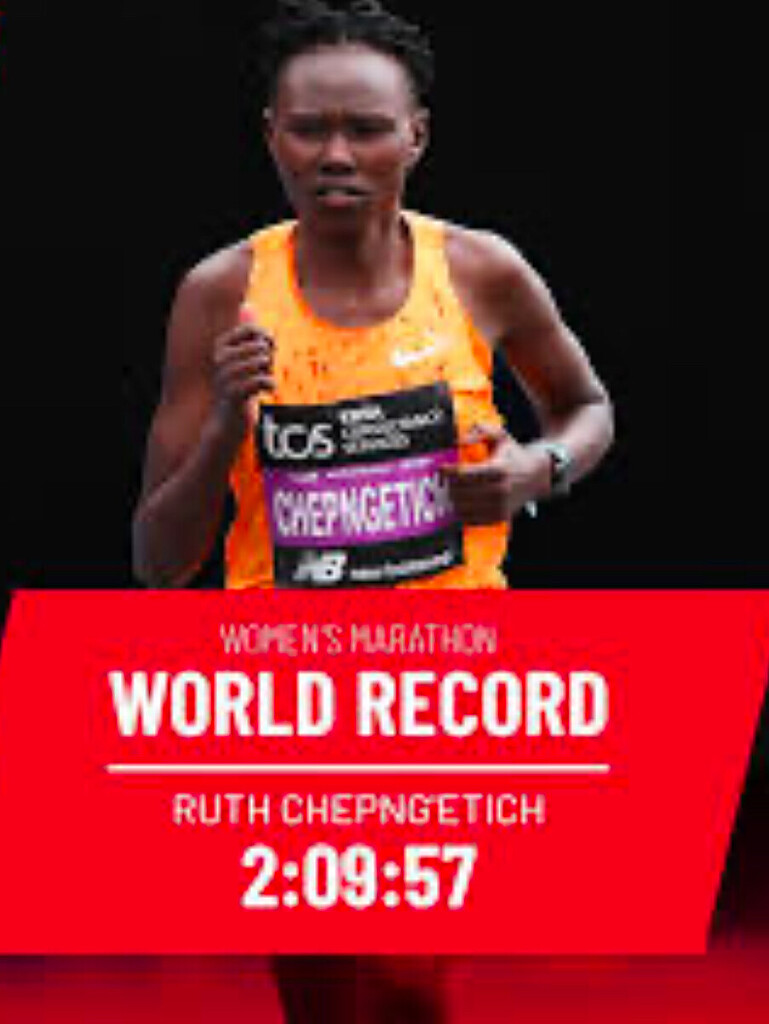

Tokyo Marathon witnessed a remarkable performance by Kenya's Ruth Chepngetich, who set a new women's marathon world record with a time of 2:11:24. This achievement sparked discussions about the rapid advancements in women's long-distance running and the influence of technology in the sport.

In the Boston Marathon, Ethiopia's Amane Beriso delivered a dominant performance, winning in 2:18:01. On the men's side, Kenya's Evans Chebet defended his title, highlighting Boston's reputation for tactical racing over sheer speed.

London Marathon saw Ethiopia's Tamirat Tola take the men's crown, besting the field with a strong tactical race. Eliud Kipchoge, despite high expectations, did not claim victory, signaling the growing competitiveness at the top of men’s marathoning. On the women's side, Kenya's Peres Jepchirchir triumphed, adding another major victory to her impressive resume.

The Berlin Marathon in 2024 showcased yet another extraordinary performance on its fast course, though it was Kelvin Kiptum’s world record from the 2023 Chicago Marathon (2:00:35) that remained untouched. In 2024, Berlin hosted strong fields but no records, leaving Kiptum’s achievement as the defining benchmark for men’s marathoning.

The Chicago Marathon was the highlight of the year, where Kenya's Ruth Chepngetich made history by becoming the first woman to run a marathon in under 2:10. She shattered the previous world record by nearly two minutes, finishing in 2:09:56. This groundbreaking achievement redefined the possibilities in women's distance running and underscored the remarkable progress in 2024.

The New York City Marathon showcased the depth of talent in American distance running, with emerging athletes achieving podium finishes and signaling a resurgence on the global stage.

Each marathon in 2024 was marked by extraordinary performances, with athletes pushing the boundaries of human endurance and setting new benchmarks in the sport.

Olympic Preparations: Paris 2024 Looms Large

With the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris just around the corner, many athletes used the year to fine-tune their preparations. Qualifying events across the globe witnessed fierce competition as runners vied for spots on their national teams.

Countries like Kenya, Ethiopia, Japan, and the United States showcased their depth, with surprising performances by athletes who emerged as dark horses. Japan’s marathon team, bolstered by its rigorous national selection process, entered the Olympic year as a force to be reckoned with, particularly in the men's race.

Ultramarathons: The Rise of the 100-Mile Phenomenon

The ultramarathon scene continued to grow in popularity, with races like the Western States 100, UTMB (Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc), and Leadville 100 drawing record participation and attention.

Courtney Dauwalter, already a legend in the sport, extended her dominance with wins at both UTMB and the Western States 100, solidifying her reputation as the GOAT (Greatest of All Time) in ultrarunning.

On the men’s side, Spain’s Kilian Jornet returned to form after an injury-plagued 2023, capturing his fifth UTMB title. His performance was a masterclass in pacing and strategy, showcasing why he remains a fan favorite.

Notably, ultramarathons saw increased participation from younger runners and athletes transitioning from shorter distances. This shift signaled a growing interest in endurance challenges beyond the marathon.

Track and Road Records: Pushing the Limits

The year 2024 witnessed groundbreaking performances on both track and road, with athletes shattering previous records and setting new benchmarks in distance running.

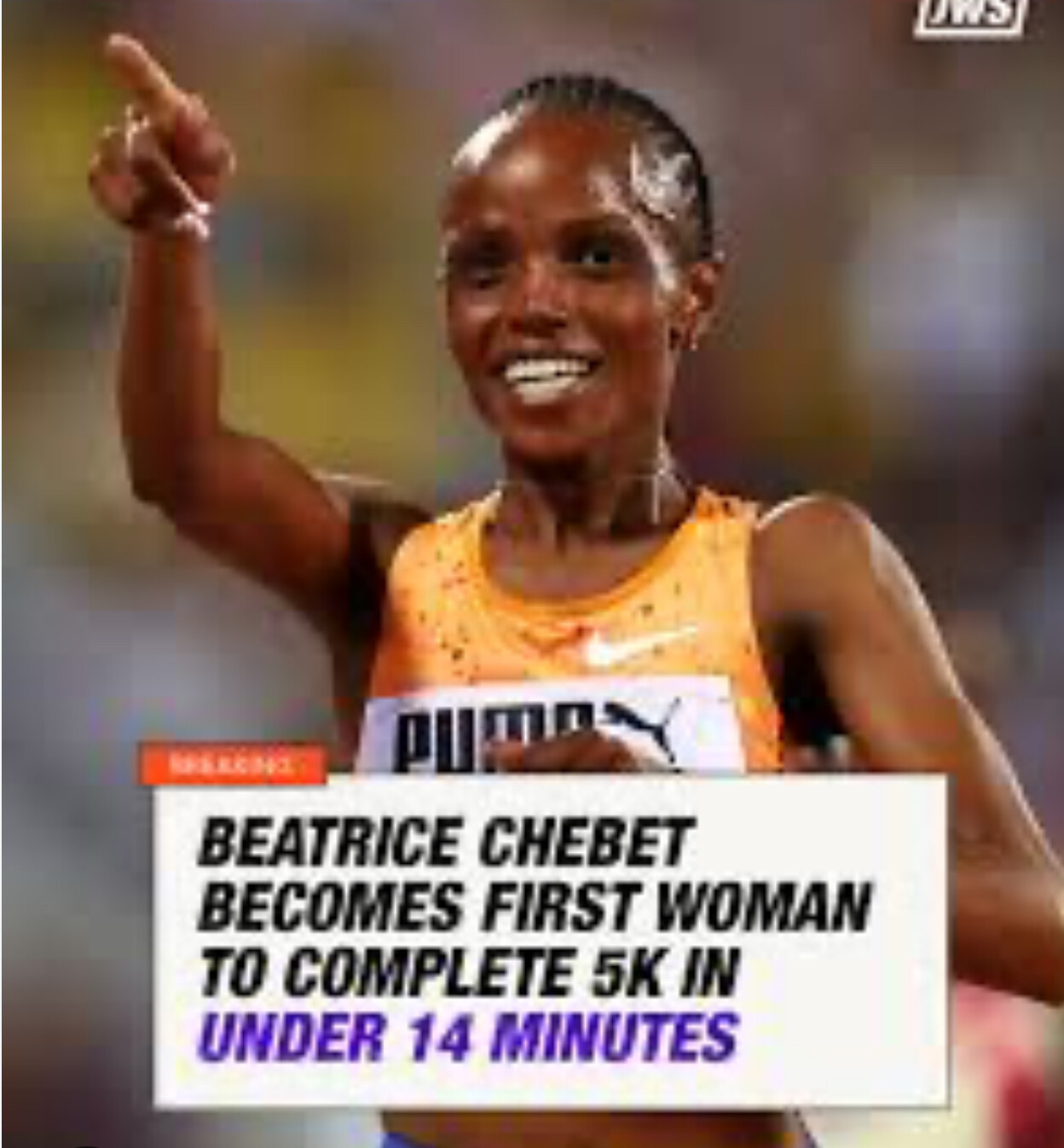

Beatrice Chebet's Dominance: Kenya's Beatrice Chebet had an exceptional year, marked by multiple world records and championship titles.

10,000m World Record: In May, at the Prefontaine Classic, Chebet broke the women's 10,000m world record, becoming the first woman to run the distance in under 29 minutes, finishing in 28:54.14.

Olympic Triumphs: At the Paris Olympics, Chebet secured gold in both the 5,000m and 10,000m events, showcasing her versatility and dominance across distances.

5km World Record: Capping off her stellar year, on December 31, 2024, Chebet set a new women's 5km world record at the Cursa dels Nassos race in Barcelona, finishing in 13:54. This achievement made her the first woman to complete the 5km distance in under 14 minutes, breaking her previous record by 19 seconds.

Faith Kipyegon's Excellence: Kenya's Faith Kipyegon continued her dominance in middle-distance running by breaking the world records in the 1500m and mile events, further cementing her legacy as one of the greatest athletes in history.

Joshua Cheptegei's 10,000m World Record: Uganda's Joshua Cheptegei reclaimed the men's 10,000m world record with a blistering time of 26:09.32, a testament to his relentless pursuit of excellence.

Half Marathon Records: The half marathon saw an explosion of fast times, with Ethiopia’s Yomif Kejelchabreaking the men's world record, running 57:29 in Valencia. The women's record also fell, with Kenya’s Letesenbet Gidey clocking 1:02:35 in Copenhagen.

These achievements highlight the relentless pursuit of excellence by distance runners worldwide, continually pushing the boundaries of human performance.

The Role of Technology and Science

The impact of technology and sports science on distance running cannot be overstated in 2024. Advances in carbon-plated shoes, fueling strategies, and recovery protocols have continued to push the boundaries of human performance.

The debate over the fairness of super shoes reached new heights, with critics arguing that they provide an unfair advantage. However, proponents emphasized that such innovations are part of the natural evolution of sports equipment.

Data analytics and personalized training plans became the norm for elite runners. Wearable technology, including advanced GPS watches and heart rate monitors, allowed athletes and coaches to fine-tune training like never before.

Grassroots Running and Mass Participation

While elite performances stole the headlines, 2024 was also a banner year for grassroots running and mass participation events. After years of pandemic disruptions, global races saw record numbers of recreational runners.

Events like the Great North Run in the UK and the Marine Corps Marathon in the U.S. celebrated inclusivity, with participants from diverse backgrounds and abilities.

The popularity of running as a mental health outlet and community-building activity grew. Initiatives like parkrunand local running clubs played a pivotal role in introducing more people to the sport.

Diversity and Representation

Diversity and representation became central themes in distance running in 2024. Efforts to make the sport more inclusive saw tangible results:

More women and runners from underrepresented communities participated in major events. Notably, the Abbott World Marathon Majors launched a program to support female marathoners from emerging nations.

Trail and ultrarunning communities embraced initiatives to make races more accessible to runners from diverse cultural and economic backgrounds.

Challenges and Controversies

Despite the many successes, 2024 was not without its challenges:

Doping Scandals: A few high-profile doping cases marred the sport, reigniting calls for stricter testing protocols and greater transparency.

Climate Change: Extreme weather conditions impacted several races, including the Boston Marathon, which experienced unusually warm temperatures. Organizers are increasingly focusing on sustainability and adapting to climate-related challenges.

Looking Ahead to 2025

As the year closes, the focus shifts to 2025, which promises to build on the momentum of 2024. Key storylines include:

The quest for a sub-2-hour marathon in a record-eligible race, with Kelvin Kiptum and Eliud Kipchoge at the forefront.

The continued growth of ultrarunning, with new records likely to fall as more athletes take up the challenge.

The evolution of distance running as a global sport, with greater inclusivity and innovation shaping its future.

Conclusion

The distance running scene in 2024 was a celebration of human potential, resilience, and the unyielding pursuit of greatness. From record-breaking marathons to grueling ultramarathons, the year reminded us of the universal appeal of running. As the sport evolves, it continues to inspire millions worldwide, proving that the spirit of running transcends borders, ages, and abilities.

by Boris

Login to leave a comment

How Recreational Runners Get Through UTMB: 'It's All About Digging Deep into Yourself'

Wearing purple shorts, a blue and white tie-dyed T-shirt, a bright pink hat, a light blue Salomon hydration pack, fluorescent yellow-rimmed Oakley sunglasses, and a pair of Hoka Speedgoat 5 shoes, Chaiwen Chou was a vibe as she crossed the finish line of Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB) on Sunday afternoon in Chamonix, France.

Chou, who had also freshened up the pink and purple tint of her hair before the race, stood out among the numerous other dusty and weary runners clad in more traditionally colored trail garb as they took their final strides in the epic 106-mile race around the Mont Blanc massif.

But what was most remarkable about the 41-year-old software developer from New York City was the huge smile on her face and expression of pure joy that emanated from her. When she arrived at the finish line after 45 hours and 15 minutes of running-about 75 minutes before the cutoff-she was beaming ear to ear and greeted with big hugs from her mom, brother, partner, and a good friend who helped crew her on her journey.

While her interest in running started on a bit of a whim a decade ago, her continued passion and progression have led her to run more than 30 trail running races, including the biggest and most celebrated one in the world. On Sunday, she was one of 95 American runners to complete the grueling UTMB course.

"So when I turned 30, I had this typical New Year's resolution, like, I want to get fit, I want to learn how to run," said Chou, who grew up in Massachusetts. "And then I met a friend who ran, and I started running with him and doing group runs. And then we started running trails, and we specifically entered The North Face Endurance Challenge, and that's where I ran my first marathon, and fell in love with trail running and then learned about ultrarunning and this whole world that I never even knew existed."For many recreational ultrarunners from around the world like Chou, UTMB sits at the top of their lifelong bucket list. It means starting at the same time as the elite professional runners on Friday evening in Chamonix, and maneuvering through the same rugged and aesthetic 106-mile loop with a daunting 32,000-feet plus of climbing and descending. It's historic, and the crowds and the energy around it are unparalleled.

It's also a monumental challenge to complete.

Trail Running's Infectious Buzz

Ultra-trail running is having a moment right now-especially since the end of the Covid pandemic-but it probably started a decade ago as the urge to run beyond the marathon gained mainstream traction and destination races around the world started to become desirable goal races for recreational runners.The North Face Endurance Challenge began as a singular 50-mile championship-style trail race near San Francisco in 2006 with a $30,000 prize purse, but it evolved into a multi-distance race weekend (from 10K to 50 miles) aimed at encouraging runners of all abilities to immerse themselves in the sport. After a few successful years of the event in Mill Valley, California, it expanded to several locations across the U.S.-upstate New York, Madison, Wisconsin, and Washington D.C., among others-and around the world.

Although The North Face pulled the plug on the series in late 2019 with a suggestion that it was going to reimagine the event format, nothing ever materialized after the Covid-19 pandemic temporarily disrupted the world-and specifically running events-in 2020. But those events played a big role in introducing runners and non-runners alike to the unique aspects of trail running, and many of those who caught the bug-like Chou-have continued to chase their passion in global events like the UTMB World Series.

Chou and her friends returned to The North Face Endurance Challenge four years in a row and she upped the ante each time, going from the marathon to the 50K and finally to consecutive finishes in the 50-miler. She competed in the 50-mile race in San Francisco in 2017 and 2019 and then started traveling to other races around the U.S. and eventually around the world. By 2020, she had completed the Madeira Island 115K race in Portugal and the Tarawera Ultramarathon 100-miler in New Zealand.

Once Covid subsided, Chou set her sights on trying to get into UTMB, which she did by collecting running stones and finishing seventh at the Grindstone 100 amid torrential rain storms last September in northwest Virginia. Her training for UTMB was interrupted in February when, just a week after she found out she secured an entry into UTMB through the lottery, she broke her ankle. Then once she got to Chamonix a week before the race, she smashed her left knee on a shakeout run and it swelled up pretty badly.

As such, her UTMB experience was rougher than she had hoped-the 80-degree heat and the 32,000 feet of vertical gain and descent pushed her to her limits-as she had challenges fueling consistently and also got sick several times. But she persevered and reached her primary goal of finishing.

Officially, she was the 1,542nd finisher out of 1,760 runners who completed the full loop. (A total of 1,001 runners started but did not finish.) She did whatever it took and she crossed the finish line.

"So this is the first time I've been in the Alps, and I'm just blown away by how beautiful it is," she said. "Even though I was in pain pretty much the whole race because the climbing and the elevation gain here are insane compared to the East Coast! But it was just so beautiful everywhere. It's pretty crazy. But you get to be out there all day though, so that's fun."Every Runner Has a Story

Becky Convery only started running four years ago in the middle of the Covid lockdown. What started as short, occasional runs turned into a passion for trail running that was fueled, in part, by doing group runs with the Virginia Happy Trails Running Club.

Like Chou, Convery also qualified for UTMB through the Grindstone 100. The 58-year-old Washington D.C. attorney almost quit that race, but she dug deep to finish. During UTMB, Convery dealt with GI issues from early on in the race and couldn't keep any food down. It was so bad, she almost dropped out at the 51.5-mile aid station in Courmayeur, Italy. But then she thought of Wayne Chang, a running buddy from Virginia, who did just that last year and immediately regretted it. With her friend's experience top of mind as she struggled, Convery persevered and finished in 45:27 with an hour to spare."I wanted to quit at Grindtone last fall. I was miserable and just wanted to go to bed, but he wouldn't let me quit," Convery said. "He's like, 'Look, I quit UTMB and I woke up a couple hours later, and I was like, 'Oh my God, what have I done?' So when it got hard out there (during UTMB), I thought of Wayne, and even though I couldn't keep food down, I said to myself, 'What would Wayne do?' He'll kill me if I quit, so I knew I couldn't quit. So I just kept going."

As much as UTMB gets considerable international notoriety for the livestream and media coverage around the elites-and understandably so, it draws many of the world's best runners-at the heart, UTMB is a personal journey of courage, commitment, and hope for most of the 2,800 runners who toe the starting line.

And really, that's what the entire sport of ultra-trail running is all about and what differentiates it from road racing. For many, it's not about racing at all-competing against other runners or even the clock-it's about challenging yourself and the natural terrain in pursuit of a dream that might seem like it's on the realistic edge of your abilities.

"It's all about digging deep into yourself," Convery said. "With this race, it's so international and there are so many nations represented, it's just an amazing time up there. Even though most people don't speak each other's language, everybody gets it. Everyone is pulling for each other. It's a great environment out there. I'm glad I made it."

Going the Distance

That's always been the case for 67-year-old Mike Smith, a retired resident of Santa Fe, New Mexico, who reached the finish line 15 minutes after Convery. It was Smith's second year in a row finishing UTMB, and because he won his age group at the Canyons 100K in April, he'll likely be back next year.

"The best part about it is always the people," Smith says. "But, oh gosh, chasing the time cutoff at that last aid station, that hike up to the La Flegere ski area, that's always a challenge."Smith relishes in those kinds of ultra-trail challenges. By reaching the finish line in Chamonix, he recorded the 224th 100-mile trail race finish of his career dating back to the mid-1990s. According to an ultrarunning history site, he ranks No. 2 in the world in all-time 100-mile finishes and first among 100-mile trail races. (Last year's UTMB was his 205th finish, which means he completed 18 100-mile ultra-trail races in the interim.

"This is always a spectacular finish," said his wife, Sandra, who wrote a book about what it's like to crew her husband at races. "This is one of the most exciting finish lines there is. The finish lines at smaller races are exciting because there's such a close community of people, but here, there are so many people from around the world, and that's just wonderful."

In all, 2,761 runners started this year's UTMB and 1,760 finished, including 95 U.S. runners who reached the finish line (out of 152 American starters) under the cutoff. Frenchman Vincent Bouillard was the overall winner in 19:54:23 on Saturday afternoon, but 20 hours later there were still about 1,000 runners moving toward the finish line and trying to beat the 46.5-hour cutoff on Sunday afternoon. Among the 95 U.S. finishers, 41 completed the course after the 40-hour mark.

Lamont King, 51, a runner from Roseville, California, has watched and been inspired by runners finishing in the golden hour of the Western States 100 as a fan and as a board member of the race for years. So finishing UTMB on his first try in 45:59-about 30 minutes before the cutoff-was a special moment for him.

"The race was very, very tough. We just don't have that kind of vertical in California where I'm from," said King, who has been trail running for 20 years. "But it's just amazing to be in this scenery in the mountains. It's just fantastic, and it makes up for a little bit of pain. I did have to push a little bit more than I probably would've liked, but I got it done. Coming in with all those people cheering for you in that final finish is almost overwhelming. It's just beautiful."

by Trail Runner Magazine

Login to leave a comment

American Katie Schide Shatters Courtney Dauwalter’s Course Record to Win UTMB

She’s now the third woman to win both Western States and UTMB in the same year.

Katie Schide is on a tear.

On Saturday, the American won the women’s race at the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB) in dominant fashion, finishing the 109-mile race in 22 hours, 9 minutes, and 31 seconds. Her time is 21 minutes faster than Courtney Dauwalter’s course record of 22:30:54 from 2021.

Schide, 32, is undefeated this year, winning the Canyons 100K in April and the prestigious Western States 100 in June.

Ruth Croft of New Zealand was 39 minutes behind Schide in second place (22:48:37). She passed Canada’s Marianne Hogan—who would finish third in 23:11:15—just after the 100-mile mark. Dauwalter, who won the Hardrock 100 on July 12, did not compete in this year’s edition.

In the men’s race, Vincent Bouillard of France was not favored to win, but he ultimately took the crown. He went to the lead after 48 miles and never relinquished it, crossing the finish line in Chamonix in 19:54:23. His compatriot, Baptiste Chassagne, was next to finish in 20:22:45, while Ecuador’s Joaquin Lopez placed third (20:26:22).

Last year’s champion, Jim Walmsley of the U.S., withdrew just after 50 miles because of a knee issue, according to a post on his Instagram story. He remains the only American man to win the race.

UTMB has been contested since 2003. The course—which slightly changes year-to-year—starts and ends in the French Alpine town of Chamonix and traverses through Italy and Switzerland along the way, covering over 30,000 feet of elevation gain.

This is Schide’s second time winning the event after taking top honors in 2022. Originally from Maine, Schide now trains in France and is sponsored by The North Face.

In the final 7 kilometers, a downhill section, she was over 20 minutes ahead of course record pace, but she started limping. The buffer, however, was enough, and by the end, the hitch in her stride had mostly dissipated.

Schide said in a post race interview on the UTMB broadcast that her main goal was to dip under the 22-hour barrier, followed by a secondary goal breaking Dauwalter’s time from 2021. Schide went out hard in the first half—like she did in 2022—but she said winning two years ago gave her some much-needed context.

“I think this race, I just went in more confident in myself and I wasn’t surprised that I was fast,” she said. “Whereas in 2022, I was kind of freaking out because I was like “Oh, I didn’t really mean to do that.’ But this time, I meant to do it, and I was just focused on trying not to die too hard at the end.”

Schide now joins Dauwalter (2023) and Nikki Kimball (2007) as the third woman to win both Western States and UTMB in the same year.

Login to leave a comment

UTMB Is Having a Golden Moment. But It’s Delicate.

After a year that included a maelstrom of controversy, the world’s most prominent ultra-trail running event has righted its path

“It felt like a golden era of trail running.”

That quote came from Keith Byrne, a senior manager at The North Face and a UTMB live stream commentator for nearly a decade, who was talking about last summer’s UTMB World Series Finals in Chamonix, France.

The UTMB races during the last week of August last summer were, I thought, the most alluring in the event’s 20-year history.

After years of being frustrated by the course, American Jim Walmsley finally put it all together for a victorious lap around Mont Blanc. In doing so he became the first U.S. man to win the race, setting a course record of 19:37:43. He and his wife, Jess, had moved from Arizona to live full-time in France to make it happen. And then there was Colorado’s Courtney Dauwalter, who won the race handily in 23:29:14 to notch her third victory and continue the strong legacy of American women on the course. The win felt extra historic because it made her the first person to win Western States, Hardrock, and UTMB in the same year—arguably the three most legendary and competitive 100-mile events in the world, and she dominated each one.

The events came off without a hitch and included record crowds in Chamonix, plus a record 52 million more tuning into the livestream.

Throughout the fall and winter, harmony and happiness seemed to give way to chaos and discontent. But a year later, as the UTMB Mont Blanc weeklong festival of trail running kicks off on August 26, everything seems back to normal in Chamonix. What happened along the way is a tale of drama, perhaps both necessary and unnecessary, all of it culminating in course corrections by the multinational race series.

In short, what a year it has been for UTMB.

And now, hordes of nervous and excited runners from all corners of the globe are descending on Chamonix for this year’s UTMB Mont-Blanc races. Registration for UTMB World Series events is reportedly up about 35 percent year over year with even greater growth in interest for OCC, CCC and UTMB race lottery applications. There is more media coverage, more pre-race hype, and more excitement than ever before. More running brands are using the UTMB Mont Blanc week to showcase their new running gear with media events, brand activations, and fun runs. Even The Speed Project—although entirely unrelated to UTMB—chose Chamonix as the starting point of its latest so-called underground point-to-point relay race to try to catch some of the considerable buzz UTMB is generating.

So what happened? Did the UTMB organization do its due diligence and make amends with several significant changes in the spring? Was the angst and stirring of emotions just not as widely felt as the fervent bouts of Instagram activism claimed it to be? Have the participants and fans of the ultra-trail running world suffered amnesia or become ambivalent? Or is it all a sign of the race—and the entire sport of trail running—going through growing pains as it adjusts to the massive global participation surge, increased professionalism, and heightened sponsorship opportunities?

On the eve of another 106-mile lap around the Mont Blanc massif, I wanted to take a look at what happened and the current state of UTMB’s global race series that culminates here in Chamonix this week.

We caught a glimpse of what was to come shortly before UTMB last year, when the race organization announced the European car company Dacia as its new title sponsor. A fossil-fuel powered conglomerate didn’t sit well with some fans of the event, coming amid an era of widespread climate doom (even though the brand would be highlighting its new Spring EV at the UTMB race expo.) The Green Runners, an environmental running community co-founded by British trail running stars Damian Hall and Jasmin Paris, called it an act of “sportswashing” and released a petition calling on UTMB to denounce the partnership. (Hall even traveled all the way to Chamonix to deliver the petition in person.)

These grumblings of discontent and others that followed exploded into a social media firestorm shortly after UTMB. In October, it became public that UTMB had moved to launch a race in British Columbia, Canada, just as a similar event in the same location was struggling with permitting. A he-said, she-said back-and–forth left onlookers with whiplash. Then on December 1, UTMB livestream commentator Corrine Malcolm announced on Instagram that she had been fired and in late January, a leaked email from elite runners Kilian Jornet and Zach Miller to fellow athletes called for a boycott of the race series. All of it, jet fuel for social media algorithms.

“We’re at a turning point in trail running, but we can keep the core values if the community stands up,” the Pro Trail Runners Association secretary, Albert Jorquera, told me at the time.

In the midst of these dramas, I interviewed race founders Catherine and Michel Poletti over lunch at a Chamonix cafe. For nearly a decade now, I have met with the couple for candid conversations that helped frame online articles and magazine stories, and most recently for the book, The Race that Changed Running: The Inside Story of UTMB.

I plunged headlong into two articles with hopes of explaining it all. There was so much heat swirling around the UTMB stories, and so little light.

“The very thing that made ultrarunning so bonding was being torn apart by the community itself through social media,” said Topher Gaylord. A former elite runner who tied for second in the inaugural UTMB in 2003, Gaylord engineered UTMB’s first title sponsorship with The North Face and has been a close supporter of the Polletis for 20 years. “Some players are using social media to divide the community. That’s super disappointing.”

To me, it felt like the aggressive online activists were winning the day. Trail running suddenly seemed polarized, infected with the intertwined social media viruses of false indignation and close-mindedness. Twice, I deep-sixed my article drafts. Friends and editors convinced me they wouldn’t be read dispassionately. Who wants to be handed a fire extinguisher, when your goal is to torch the house?

Well, what a difference eight months can make. We now have some perspective and, with it, some answers.

Since its earliest days, UTMB’s volunteer founding committee believed in the values of the sport. The very first brochure produced for the race—a mere sheet of paper—featured a paragraph on values. In later years that statement became much more comprehensive, expanding to cover a wide range of topics and the race’s mission to support and protect them.

But maintaining those values in an organization that has gone from a singular race with a literal garden-shed office to a 43 global event series with a staff of more than 70 full-time employees is tricky at best. In an interview once, Michel Poletti paused, asking if I had seen a photo of a mutual friend that was making the rounds. He was climbing one of Chamonix’s famed needle-sharp aiguilles, one foot on each side of a razor sharp ridge—a perilous balancing act, big air on each side. It was his metaphor for trying to move ever up, while balancing business growth and heartfelt values.

Over the course of dozens of hours of interviews with the Polettis, I came to learn one thing: UTMB always moves forward up the ridge. In the process, UTMB corrects its course. It starts with a careful analysis after each edition, evaluating pain points in areas such as logistics, security, media, traffic, and others, discussing how they can be addressed. Historically, those course corrections haven’t been at the pace others might want—especially since the social unrest that developed during the Covid pandemic—but the organization has a reliable pattern of steadily addressing concerns.

And so, not too many weeks after that lunch meeting, UTMB set to work. First came a heartfelt effort they kept under the radar—traveling around the U.S. to listen and learn. They spent two weeks in the U.S. in February, visiting with American athletes, race directors, journalists, consultants, and their Ironman partners. “We need to learn from our mistakes and from this crisis,” Michel said.

Methodically over the ensuing months, UTMB rolled out a series of changes. Some were aimed at directly addressing the controversies, others were overdue for what is, by any metric, the world’s premier ultra-trail running event.

“My hope is that the trail running community understands that we are human,” Catherine had told me over the winter.

Four months ago, at the end of April, the race organization announced that Hoka would become the new title sponsor of UTMB Mont-Blanc and the entire UTMB World Series through 2028. It was a huge move because Hoka, one of the biggest running brands in the world, essentially doubled-down on its support of UTMB and trail running in general. The five-year deal brought benefits other than cash, too. Hoka has a strong history of inclusivity and growing representation among marginalized communities, an area UTMB has announced it intends to focus more on beginning this year. The deal also moved Dacia out of the title sponsor limelight, instead bringing a brand with a strong reputation in trail running to the fore.

Dacia was shifted to the role of a premier partner in Europe, and now plays an integral part in a new eco-focused mobility plan UTMB updated in July. Fifty of their cars can be signed out for use by over 70 staff and 2,500 volunteers, encouraging them to arrive in Chamonix using public transportation instead. The move is estimated to eliminate 200 vehicles driving into the valley. (The organization’s new mobility plan will transport an estimated 15,000 runners and supporters, eliminating the need for approximately 6,000 cars during the UTMB Mont-Blanc week. On average, a bus will run every 15 minutes between Chamonix and Courmayeur, Italy, and Chamonix and Orsières, Switzerland.)

In May, UTMB announced a new anti-doping policy it had developed with input from PTRA. The organization committed to spending at least $110,000 per year, money that will be allocated to test all podium finishers and a randomized selection of the 687 elite athletes in attendance. The new policies will be implemented by the International Testing Association, an independent nonprofit that has also conducted two free informational webinars for the 1,400 UTMB Mont Blanc elite runners.