Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #Dathan Ritzenhein

Today's Running News

Geordie Beamish Rises from a Fall to World Champion Glory in Tokyo

Tokyo, September 15, 2025 — New Zealand’s Geordie Beamish produced one of the most dramatic victories of the World Athletics Championships, storming to gold in the men’s 3000m steeplechase. His winning time of 8:33.88 edged Morocco’s reigning champion Soufiane El Bakkali by just 0.07 seconds, with 17-year-old Kenyan Edmund Serem taking bronze in 8:34.56 .

This is a breakthrough moment for New Zealand athletics: the nation’s first-ever outdoor World Championships track gold .

A Tactical Race Decided at the Line

The steeplechase final unfolded at a controlled pace, leaving the medals to be decided in the closing laps. El Bakkali, a two-time Olympic and world champion, looked ready to add another title. But Beamish, renowned for his devastating kick, stayed composed.

On the last lap, he surged through the field, matching El Bakkali stride for stride. Off the final water jump, Beamish unleashed one last burst of speed. In a thrilling lean at the line, he dethroned one of the event’s greats.

A fall and a spike in the heats

Beamish’s victory was even more remarkable considering his rough path to the final. In his qualifying heat, he fell heavily and was stepped on in the face, yet managed to get up and finish second to advance .

That resilience set the tone for his gold-medal run.

Who Is Geordie Beamish?

• Born: October 24, 1996, in Hastings, New Zealand

• Club: On Athletics Club (based in Boulder, Colorado)

• Coach: Dathan Ritzenhein

• Specialties: 1500m through 5000m, and now the steeplechase

• Career highlights:

• 2024 World Indoor Champion in the 1500m (Glasgow)

• Oceania record holder in the 3000m steeplechase (8:09.64, Paris, 2024)

• Fifth in the 2023 World Championships steeplechase final

Beamish’s late move to the steeplechase has transformed his career, turning him from a versatile miler into a global champion.

This was a big upset

Beamish’s Tokyo win not only toppled El Bakkali’s reign but also put New Zealand back on the map of world middle-distance running. For a nation that once celebrated icons like Peter Snell and John Walker, this is a new chapter in the sport’s history.

With the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics on the horizon , Beamish has proven he has the strength, resilience, and tactical brilliance to contend for more global medals.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Joe Klecker Plans His Half Marathon Debut

In a live recording of The CITIUS MAG Podcast in New York City, U.S. Olympian Joe Klecker confirmed that he is training for his half marathon debut in early 2025. He did not specify which race but signs point toward the Houston Half Marathon on Jan. 19th.

“We’re kind of on this journey to the marathon,” Klecker said on the Citizens Bank Stage at the 2024 TCS New York City Marathon Expo. “The next logical step is a half marathon. That will be in the new year. We don’t know exactly where yet but we want to go attack a half marathon. That’s what all the training is focused on and that’s why it’s been so fun. Not that the training is easy but it’s the training that comes the most naturally to me.”

Klecker owns personal bests of 12:54.99 for 5000m and 27:07.57 for 10,000m. In his lone outdoor track race of 2024, he ran 27:09.29 at Sound Running’s The Ten in March and missed the Olympic qualifying standard of 27:00.00.

His training style and genes (his mother Janis competed at the 1992 Summer Olympics in the marathon and won two U.S. marathon national championships in her career; and his father Barney previously held the U.S. 50-mile ultramarathon record) have always linked Klecker to great marathoning potential. For this year’s TCS New York City Marathon, the New York Road Runners had Klecker riding in the men’s lead truck so he could get a front-row glimpse at the race and the course, if he chooses to make his debut there or race in the near future.

The Comeback From Injury

In late May, Klecker announced he would not be able to run at the U.S. Olympic Track and Field Trials in June due to his recovery from a torn adductor earlier in the season, which ended his hopes of qualifying for a second U.S. Olympic team. He spent much of April cross training and running on the Boost microgravity treadmill at a lower percentage of his body weight.

“The process of coming back has been so smooth,” Klecker says. “A lot of that is just because it’s been all at the pace of my health. I haven’t been thinking like, ‘Oh I need to be at this level of fitness in two weeks to be on track for my goals.’ If my body is ready to go, we’re going to keep progressing. If it’s not ready to go, we’re going to pull back a little bit. That approach is what helped me get through this injury.”

One More Track Season

Klecker is not fully prepared to bid adieu to the track. He plans to chase the qualifying standard for the 10,000 meters and attempt to qualify for the 2025 World Championships in Tokyo. In 2022, after World Athletics announced Tokyo as the 2025 host city, he told coach Dathan Ritzenhein that he wanted the opportunity to race at Japan National Stadium with full crowds.

“I’m so happy with what I’ve done on the track that if I can make one more team, I’ll be so happy,” Klecker says. “Doing four more years of this training, I don’t know if I can stay healthy to be at the level I want to be. One more team on the track would just be like a dream.”

Klecker is also considering doubling up with global championships and could look to qualify for the 2025 World Road Running Championships, which will be held Sept. 26th to 28th in San Diego. To make the team, Klecker would have to race at the Atlanta Half Marathon on Sunday, March 2nd, which also serves as the U.S. Half Marathon Championships. The top three men and women will qualify for Worlds. One spot on Team USA will be offered via World Ranking.

Sound Running’s The Ten, one of the few fast opportunities to chase the 10,000m qualifying standard on the track, will be held on March 29th in San Juan Capistrano.

Thoughts on Ryan Hall’s American Record

The American record in the half marathon remains Ryan Hall’s 59:43 set in Houston on Jan. 14th, 2007. Two-time Olympic medalist Galen Rupp (59:47 at the 2018 Prague Half) and two-time U.S. Olympian Leonard Korir (59:52 at the 2017 New Dehli Half) are the only other Americans to break 60 minutes.

In the last three years, only Biya Simbassa (60:37 at the 2022 Valencia Half), Kirubel Erassa (60:44 at the 2022 Houston Half), Diego Estrada (60:49 at the 2024 Houston Half) and Conner Mantz (60:55 at the 2021 USATF Half Marathon Championships) have even dipped under 61 minutes.

On a global scale, Nineteen of the top 20 times half marathon performances in history have come since the pandemic. They have all been run by athletes from Kenyan, Uganda, and Ethiopia, who have gone to races in Valencia (Spain), Lisbon (Portugal), Ras Al Khaimah (UAE), or Copenhagen (Denmark), and the top Americans tend to pass on those races due to a lack of appearance fees or a stronger focus on domestic fall marathons.

Houston in January may be the fastest opportunity for a half marathon outside of the track season, which can run from March to September for 10,000m specialists.

“I think the record has stood for so long because it is such a fast record but we’re seeing these times drop like crazy,” Klecker says. “I think it’s a matter of time before it goes. Dathan (Ritzenhein) has run 60:00 so he has a pretty good barometer of what it takes to be in that fitness. Listening to him has been really good to let me know if that’s a realistic possibility and I think it is. That’s a goal of mine. I’m not there right now but I’m not racing a half marathon until the new year. I think we can get there to attempt it. A lot has to go right to get a record like that but just the idea of going for it is so motivating in training.”

His teammate, training partner, and Olympic marathon bronze medalist Hellen Obiri has full confidence in Klecker’s potential.

“He has been so amazing for training,” Obiri said in the days leading up to her runner-up finish at the New York City Marathon. “I think he can do the American record.”

by Chris Chavez

Login to leave a comment

Aramco Houston Half Marathon

The Chevron Houston Marathon provides runners with a one-of-a-kind experience in the vibrant and dynamic setting of America's fourth-largest city. Renowned for its fast, flat, and scenic single-loop course, the race has earned accolades as the "fastest winter marathon" and the "second fastest marathon overall," according to the Ultimate Guide to Marathons. It’s a perfect opportunity for both elite athletes...

more...Hellen Obiri shares how love from Americans is motivating her to succeed in marathons

Kenyan marathoner Hellen Obiri has revealed how moving to the United States has become a major source of motivation for her given the way she gets treated well by Americans.

Two-time Boston Marathon champion Hellen Obiri is loving life in America since relocating to pursue her marathon dreams.

Obiri moved stateside in 2022 ahead of her marathon debut in New York that year, teaming up with a new coach and training group in Boulder, Colorado.

She joined the On Athletics Club (OAC), an elite team based in Boulder which is led by former distance runner Dathan Ritzenhein.

After a disappointing marathon debut in New York that saw her finish sixth in 2022, she has since got it right to win Boston twice (2023 and 2024) and New York in 2023, while she is looking for another victory in the Big Apple next month.

Preparation for her races means meeting different people on the road as she trains and the frequency has yielded familiarity while her success is now rubbing off on most Americans who have responded with love that has left the 34-year-old delighted and motivated.

“People here know me. Like now when I train, people say; ‘Hey Hellen, we saw you in Paris during [Olympics] closing ceremony you did so well, well done,’” she told FloTrack.

“It feels so good when people appreciate your work. I feel like I need to work extra hard for them to continue appreciating me. It keeps motivating me a lot,” he added.

Obiri will hope that the love from American motivates her to another rare double as she is looking to win both New York and Boston titles for the second straight year.

The mother of one, who relocated with her family to the US, has since adapted to life in America with Boulder’s high-altitude, rolling trails and temperate climate making it an ideal location for distance runners like her.

by Joel Omotto

Login to leave a comment

How to Run in the Heat Like the Pros

Over the past decade, training for the heat has gone from a nice-to-have to an absolute necessity for top runners. Professor Chris Minson is attempting to perfect the science.

After a few pleasant hours sitting in the sun watching the Prefontaine Classic in Eugene, Oregon last month, I headed down into the bowels of Hayward Field for a grueling test for running in the heat. Chris Minson, a professor of human physiology at the University of Oregon, had invited me to try the heat adaptation protocol he has developed for elite athletes from the university and from local pro teams like the Bowerman Track Club. I’ve written about Minson’s research several times, so experiencing the protocol first-hand seemed like a good idea… at the time.

Heat is a big deal in sports these days, and it’s only getting bigger. In recent years we’ve had major events like the world track and field championships in insanely hot places, like Qatar, where the marathons had to be started at midnight. But summertime in Eugene (where the Olympic Track Trials will take place later this month) and Paris (where the Olympics will be held) can also be sizzling. Over the past decade, heat preparation has gone from a nice-to-have to an absolute necessity for top athletes. The details of how to prepare remain more art than science, though, so I was interested to see how Minson put theory into practice.

Back in the 1920s and 1930s, scientists developed the first heat adaptation protocols for workers in South Africa’s sweltering gold mines. The gold standard for heat adaptation evolved from that work: spend at least an hour a day exercising in hot conditions, and after 10 to 14 days you’ll see a bunch of physiological changes. Your core temperature will be lower, your blood volume will be higher, you’ll begin sweating and dilating your blood vessels at a lower temperature threshold, you’ll sweat more, and so on. Put it all together and you’ll be able to stay cooler and run faster in hot conditions.

In fact, there’s even evidence that this type of heat adaptation can make you faster in moderate weather, perhaps as a result of the extra blood plasma. In the lead-up to the 2008 Olympics, Minson was working with American marathoner Dathan Ritzenhein, helping him prepare for the expected hot conditions in Beijing. But he started to worry about what would happen if it wasn’t hot: would all the heat training actually make Ritzenhein slower? Minson and his colleagues ran a study to find out; the results, which they published in 2010, suggested that heat adaptation helps even in cool conditions. That’s the study that really kicked interest in heat training into higher gear.

The problem with the classic approach, though, is that training for an hour in hot, muggy conditions is exhausting. If you’re trying to do a hard workout, you won’t be able to hit the splits you want. If you’re trying to do an easy run, it’s going to take more out of you than it usually does, potentially compromising your next hard workout or raising your risk of overtraining. So how do you get the benefits of heat adaptation without tanking the rest of your training plan?

Minson’s Exercise & Environmental Physiology Lab at the University of Oregon, which he co-runs with fellow physiologist John Halliwill, is located in the Bowerman Sports Science Center, a state-of-the-art facility located under the northwest grandstand of Hayward Field. The key piece of equipment, for my purposes, is an environmental chamber that can take you down to 0 degrees Fahrenheit or up to 22,000 feet of simulated altitude, deliver simulated solar radiation, or blast you with wind. For my heat run, Minson set the dials to 100 degrees Fahrenheit and 40 percent humidity.

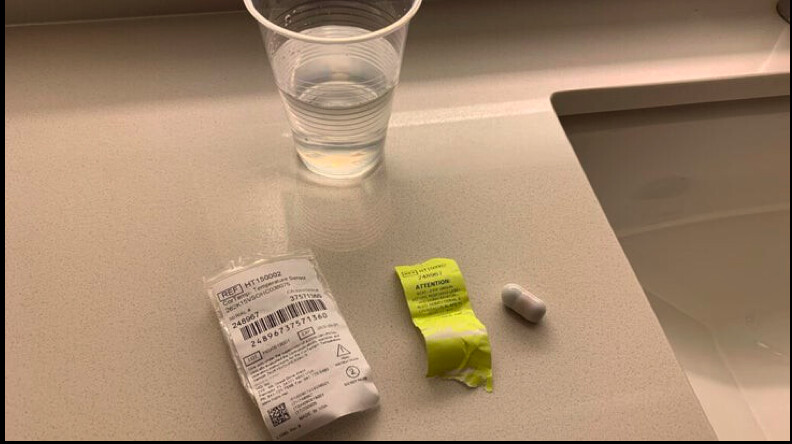

Earlier that day, Minson had given me a thermometer pill to swallow, which would enable him to wirelessly track my core temperature as the run progressed. “I’ll need that back,” he warned me, poker-faced. Fortunately, he was joking.

Before I entered the chamber, I peed in a cup so that Minson could check my urine-specific gravity, the ratio of how dense your urine is compared to water. I clocked in at 1.025, marginally above Minson’s threshold of 1.024 for mild dehydration. I blame it on having spent a few hours sitting in the sun watching the track meet. Then he checked my weight, so that he’d be able to figure out how much I sweated during the test.

When I stepped into the chamber, wearing nothing but shorts and running shoes, I could feel the blast of heat, but it wasn’t too oppressive—like a really hot day at the beach but under an umbrella. I started with a five-minute warm-up at a slow pace, gradually ramping up until I hit 7:30 mile pace. Then the formal protocol started: 30 minutes at that pace.

The pace was self-chosen; Minson refused to tell me the pace I “should” run. The goal was to settle in at an effort that I could comfortably maintain for half-an-hour, and that would get me hot enough to trigger adaptations—a core temperature of about 101 degrees Fahrenheit is thought to be about right—without overshooting and roasting myself. Most of the elite runners he works with end up choosing paces between 7:00 and 8:00 per mile. I slotted myself in the middle of that range—which, let’s be honest, was a dumb thing to do for an aging non-elite runner.

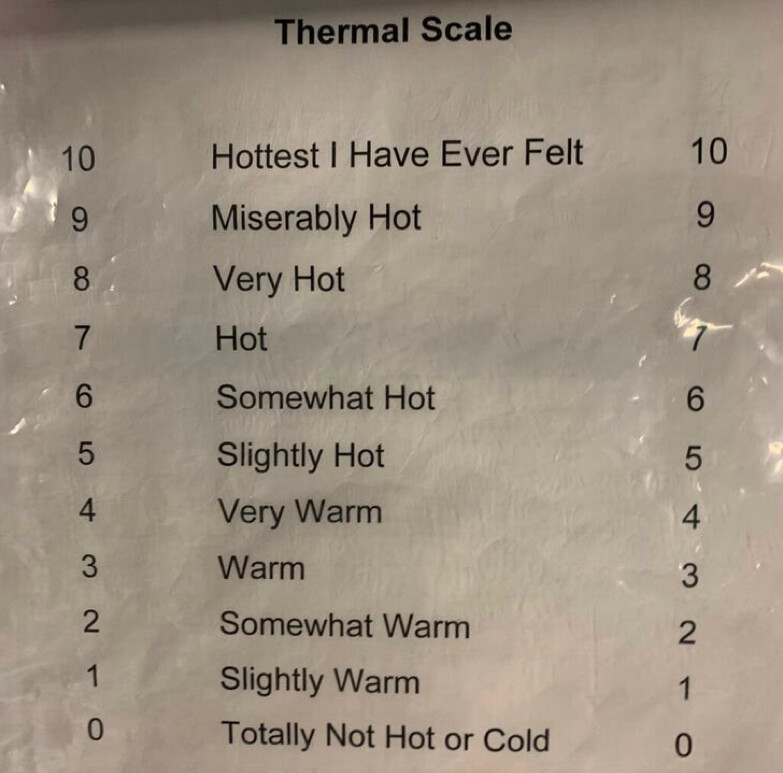

Still, the running itself felt easy to me. Every five minutes or so, Minson had me rate my perceived effort on the Borg scale, which runs from 6 to 20, and also rate how hot I felt. For this, he used his own 0 to 10 thermal scale.

I started out at the effort of 10 (“very light”) and thermal sensation of 3 (“warm”). After 15 minutes, my effort had crept up to 12 (“somewhat hard”), but my thermal sensation was still 3. By this point I was sweating up a storm, watching with interest as my splatters of sweat made a distinctly asymmetric pattern on the treadmill’s control panel. (Clearly I needed to visit the biomechanics lab down the hallway to sort out my stride asymmetries.)

In the latter part of the test, my sweat rate seemed to drop—not a great sign, since it could signal dehydration. My effort topped out at 13, but my thermal sensation crept up to 4 (“very warm”), then 5 (“slightly hot”), then 6 (“somewhat hot”). I still felt under control, though. Then the test ended, and Minson ushered me off the treadmill, into the next room, and into the hot tub, where he asked me to submerge myself up to my neck. The water was set to 104 degrees Fahrenheit, and it was awful. My thermal sensation immediately spiked up to 8 (“very hot”) and then 9 (“miserably hot”).

The odd thing is that the water was basically the same temperature as I was. My core temperature had crept up to 103.2 degrees towards the end of the run, and hit 103.7 shortly afterward. The water wasn’t warming me up in any significant way, but it was robbing me of the superficial perception of coolness that I got from air currents and the evaporation of sweat. It’s a good reminder of why cooling techniques like ice towels or simply dumping water on your head can be valuable: they can dramatically change your perception of how hot you are.

Sitting in that hot tub wasn’t fun, but it’s a key tool for Minson in his efforts to help athletes adapt to heat without interfering with their normal training. It extends the period of thermal stress without trashing their legs. A half-hour easy run, even in hot conditions, isn’t that draining for a well-trained athlete. At least, it’s not supposed to be.

After I’d had a cold shower and chugged a few bottles of sports drink, Minson went over the results with me. The good news is that I hadn’t seemed very bothered by the heat. I’d sweated out 2.2 pounds of fluid, indicating a fairly high sweat rate of around 2 liters per hour. That suggests that I should already be reasonably well equipped to race in warm conditions.

The bad news, though, was that my numbers didn’t make sense. There are no “wrong” answers on a subjective scale, but mine were puzzling. As the test proceeded and my core temperature drifted over 100 degrees, I kept claiming that I felt merely 3-out-of-10 “warm.” That might mean that I’m immune to heat—but more likely, it suggests that I wasn’t properly attuned to my body’s condition. If you’re running in the heat but you’re totally oblivious to how hot you’re getting, that can be a recipe for disaster.

In fact, my subjective numbers were strikingly similar to those of an elite runner Minson has worked with—one who has struggled in the heat. Minson helped the athlete renormalize his heat perception, so that conditions he originally labeled as 3 out of 10 became a more realistic 5 or 6 out of 10.

The ability to accurately gauge how hot you are is important even in training, because those core temperature pills are about $70 a pop. Once athletes have a sense of how hot they should feel during heat adaptation runs, Minson has them judge their half-hour efforts by feel. If they start getting too hot—above 7 on the Minson Scale—they can turn a fan on in the heat chamber to avoid overheating. There’s no rigid schedule of when they do these heat runs: they fit them in around their other training and racing and travel plans.

In practice, of course, most of us don’t have access to a high-tech heat chamber and temperature-controlled hot tub. But studies in recent years have shown that you can use a variety of approaches to get your core temperature up: hot baths, saunas (Minson has one in his lab, and another in his backyard), overdressing during runs. The big-picture takeaway from Minson’s approach is that you can find ways of getting a heat stimulus without disrupting the rest of your training.

To do that, though, you need to be able to gauge when you’re getting overcooked. When I got back to my hotel room that afternoon, I realized that I was feeling wrung out, as if I’d done a long, hard workout rather than a half-hour jog. I’d missed the mark. I decided to take the next day off, and dreamed that night of Minson’s other recent research focus: ice baths.

by Outside Online

Login to leave a comment

The Pill That Over Half the Distance Medallists Used at the 2023 Worlds

What's the deal with sodium bicarbonate?What if there was a pill, new to the market this year, that was used by more than half of the distance medalists at the 2023 World Athletics Championships? A supplement so in-demand that there was a reported black market for it in Budapest, runners buying from other runners who did not advance past the preliminary round — even though the main ingredient can be found in any kitchen?

How did this pill become so popular? Well, there are rumors that Jakob Ingebrigtsen has been taking it for years — rumors that Ingebrigtsen’s camp and the manufacturers of the pill will neither confirm nor deny.

So about this pill…does it work? Does it actually boost athletic performance? Ask a sports scientist, someone who’s studied it for more than a decade, and they’ll tell you yes.

“There’s probably four or five legal, natural supplements, if you will, that seem to have withstood the test of time in terms of the research literature and [this pill] is one of those,” says Jason Siegler, Director of Human Performance in the College of Health Solutions at Arizona State University.

But there’s a drawback to this pill. It could…well, let’s allow Luis Grijalva, who used it before finishing 4th in the World Championship 5,000m final in Budapest, to explain.

“I heard stories if you do it wrong, you chew it, you kind of shit your brains out,” Grijalva says. “And I was a little bit scared.”

The research supports that, too.

“[Gastrointestinal distress] has by far and away been the biggest hurdle for this supplement,” Siegler says.Okay, enough with the faux intrigue. If you’ve read the subtitle of this article, you know the pill we are talking about is sodium bicarbonate. Specifically, the Maurten Bicarb System, which has been available to the public since February and which has been used by some of the top teams in endurance sports: cycling juggernaut Team Jumbo-Visma and, in running, the On Athletics Club and NN Running Team. (Maurten has sponsorship or partnership agreements with all three).Some of the planet’s fastest runners have used the Maurten Bicarb System in 2023, including 10,000m world champion Joshua Cheptegei, 800m silver medalist Keely Hodgkinson, and 800m silver medalist Emmanuel Wanyonyi. Faith Kipyegon used it before winning the gold medal in the 1500m final in Budapest — but did not use it before her win in the 5,000m final or before any of her world records in the 1500m, mile, and 5,000m.

Herman Reuterswärd, Maurten’s head of communications, declined to share a full client list with LetsRun but claims two-thirds of all medalists from the 800 through 10,000 meters (excluding the steeplechase) used the product at the 2023 Worlds.

After years of trial and error, Maurten believes it has solved the GI issue, but those who have used their product have reported other side effects. Neil Gourley used sodium bicarbonate before almost every race in 2023, and while he had a great season — British champion, personal bests in the 1500 and mile — his head ached after races in a way it never had before. When Joe Klecker tried it at The TEN in March, he felt nauseous and light-headed — but still ran a personal best of 27:07.57. In an episode of the Coffee Club podcast, Klecker’s OAC teammate George Beamish, who finished 5th at Worlds in the steeplechase and used the product in a few races this year, said he felt delusional, dehydrated, and spent after using it before a workout this summer.

“It was the worst I’d felt in a workout [all] year, easily,” Beamish said.

Not every athlete who has used the Maurten Bicarb System has felt side effects. But the sport as a whole is still figuring out what to do about sodium bicarbonate.

Many athletes — even those who don’t have sponsorship arrangements with Maurten — have added it to their routines. But Jumbo-Visma’s top cyclist, Jonas Vingegaard — winner of the last two Tours de France — does not use it. Neither does OAC’s top runner, Yared Nuguse, who tried it a few times in practice but did not use it before any of his four American record races in 2023.“I’m very low-maintenance and I think my body’s the same,” Nuguse says. “So when I tried to do that, it was kind of like, Whoa, what is this? My whole body felt weird and I was just like, I either did this wrong or this is not for me.”

How sodium bicarbonate works

The idea that sodium bicarbonate — aka baking soda, the same stuff that goes in muffins and keeps your refrigerator fresh — can boost athletic performance has been around for decades.

“When you’re exercising, when you’re contracting muscle at a really high intensity or a high rate, you end up using your anaerobic energy sources and those non-oxygen pathways,” says Siegler, who has been part of more than 15 studies on sodium bicarbonate use in sport. “And those pathways, some of the byproducts that they produce, one of them is a proton – a little hydrogen ion. And that proton can cause all sorts of problems in the muscle. You can equate that to that sort of burn that you feel going at high rates. That burn, most of that — not directly, but indirectly — is coming from the accumulation of these little hydrogen ions.”

As this is happening, the kidneys produce bicarbonate as a defense mechanism. For a while, bicarbonate acts as a buffer, countering the negative effects of the hydrogen ions. But eventually, the hydrogen ions win.The typical concentration of bicarbonate in most people hovers around 25 millimoles per liter. By taking sodium bicarbonate in the proper dosage before exercise, Siegler says, you can raise that level to around 30-32 millimoles per liter.

“You basically have a more solid first line of defense,” Siegler says. “The theory is you can go a little bit longer and tolerate the hydrogen ions coming out of the cell a little bit longer before they cause any sort of disruption.”

Like creatine and caffeine, Siegler says the scientific literature is clear when it comes to sodium bicarbonate: it boosts performance, specifically during events that involve short bursts of anaerobic activity. But there’s a catch.

***

Bicarb without the cramping

Sodium bicarbonate has never been hard to find. Anyone can swallow a spoonful or two of baking soda with some water, though it’s not the most appetizing pre-workout snack. The problem comes when the stomach tries to absorb a large amount of sodium bicarbonate at once.

“You have a huge charged load in your stomach that the acidity in your stomach has to deal with and you have a big shift in the partial pressure of carbon dioxide across the gut,” Siegler says. “And that’s what gives you the cramping.”

A few years ago, Maurten was trying to solve a similar problem for marathoners trying to ingest large amounts of carbohydrates during races. The result was their carbohydrate drink, which relies on something called a hydrogel to form in the stomach. The hydrogel resists the acidity of the stomach and allows the carbohydrates to be absorbed in the intestine instead, where there is less cramping.

“We thought, okay, we are able to solve that one,” Reuterswärd says. “Could we apply the hydrogel technology to something else that is really risky to consume that could be beneficial?”

For almost four years, Maurten researched the effects of encapsulating sodium bicarbonate in hydrogels in its Swedish lab, conducting tests on middle-distance runners in Gothenburg. Hydrogels seemed to minimize the risk, but the best results came when hydrogels were paired with microtablets of sodium bicarbonate.

The result was the Maurten Bicarb System — “system,” because the process for ingesting it involves a few steps. Each box contains three components: a packet of hydrogel powder, a packet of tiny sodium bicarbonate tablets, and a mixing bowl. Mix the powder with water, let it stand for a few minutes, and sprinkle in the bicarb.The resulting mixture is a bit odd. It’s gooey. It’s gray. It doesn’t really taste like anything. It’s not quite liquid, not quite solid — a yogurt-like substance flooded with tiny tablets that you eat with a spoon but swallow like a drink.

The “swallow” part is important. Chew the tablets and the sodium bicarbonate will be absorbed before the hydrogels can do their job. Which means a trip to the toilet may not be far behind.

When Maurten launched its Bicarb System to the public in February 2023, it did not have high expectations for sales in year one.

“It’s a niche product,” Reuterswärd says. “From what we know right now, it maybe doesn’t make too much sense if you’re an amateur, if you’re just doing 5k parkruns.”

But in March, Maurten’s product began making headlines in cycling when it emerged that it was being used by Team Jumbo-Visma, including by stars Wout van Aert and Primož Roglič. Sales exploded. Because bicarb dosage varies with bodyweight, Maurten’s system come in four “sizes.” And one size was selling particularly well.

“If you’re an endurance athlete, you’re around 60-70 kg (132-154 lbs),” Reuterswärd says. “We had a shortage with the size that corresponded with that weight…The first couple weeks, it was basically only professional cyclists buying all the time, massive amounts. And now we’re seeing a similar development in track & field.”

If there was a “Jumbo-Visma” effect in cycling, then this summer there was a “Jakob Ingebrigtsen” effect in running.To be clear: there is no official confirmation that Ingebrigtsen uses sodium bicarbonate. His agent, Daniel Wessfeldt, did not respond to multiple emails for this story. When I ask Reuterswärd if Ingebrigtsen has used Maurten’s product, he grows uncomfortable.

“I would love to be very clear here but I will have to get back to you,” Reuterswärd says (ultimately, he was not able to provide further clarification).

But when Maurten pitches coaches and athletes on its product, they have used data from the past two years on a “really good” 1500 guy to tout its effectiveness, displaying the lactate levels the athlete was able to achieve in practice with and without the use of the Maurten Bicarb System. That athlete is widely believed to be Ingebrigtsen. Just as Ingebrigtsen’s success with double threshold has spawned imitators across the globe, so too has his rumored use of sodium bicarbonate.

Grijalva says he started experimenting with sodium bicarbonate “because everybody’s doing it.” And everybody’s doing it because of Ingebrigtsen.

“[Ingebrigtsen] was probably ahead of everybody at the time,” Grijalva said. “Same with his training and same with the bicarb.”

OAC coach Dathan Ritzenhein took sodium bicarbonate once before a workout early in his own professional career, and still has bad memories of swallowing enormous capsules that made him feel sick. Still, he was willing to give it a try with his athletes this year after Maurten explained the steps they had taken to reduce GI distress.

“Certainly listening to the potential for less side effects was the reason we considered trying it,” says Ritzenhein. “I don’t know who is a diehard user and thinks that it’s really helpful, but around the circuit I know a lot of people that have said they’ve [tried] it.”

Coach/agent Stephen Haas says a number of his athletes, including Gourley, 3:56 1500 woman Katie Snowden, and Worlds steeple qualifier Isaac Updike, tried bicarb this year. In the men’s 1500, Haas adds, “most of the top guys are already using it.”

Yet 1500-meter world champion Josh Kerr was not among them. Kerr’s nutritionist mentioned the idea of sodium bicarbonate to him this summer but Kerr chose to table any discussions until after the season. He says he did not like the idea of trying it as a “quick fix” in the middle of the year.

“I review everything at the end of the season and see where I could get better,” Kerr writes in a text to LetsRun. “As long as the supplement is above board, got all the stamps of approvals needed from WADA and the research is there, I have nothing against it but I don’t like changing things midseason.”

***

So does it actually work?

Siegler is convinced sodium bicarbonate can benefit athletic performance if the GI issues can be solved. Originally, those benefits seemed confined to shorter events in the 2-to 5-minute range where an athlete is pushing anaerobic capacity. Buffering protons does no good to short sprinters, who use a different energy system during races.

“A 100-meter runner is going to use a system that’s referred to the phosphagen or creatine phosphate system, this immediate energy source,” Siegler says. “…It’s not the same sort of biochemical reaction that eventuates into this big proton or big acidic load. It’s too quick.”

But, Siegler says, sodium bicarbonate could potentially help athletes in longer events — perhaps a hilly marathon.

“When there’s short bursts of high-intensity activity, like a breakaway or a hill climb, what we do know now is when you take sodium bicarbonate…it will sit in your system for a number of hours,” Siegler says. “So it’s there [if] you need it, that’s kind of the premise behind it basically. If you don’t use it, it’s fine, it’s not detrimental. Eventually your kidneys clear it out.”Even Reuterswärd admits that it’s still unclear how much sodium bicarbonate helps in a marathon — “honestly, no one knows” — but it is starting to be used there as well. Kenya’s Kelvin Kiptum used it when he set the world record of 2:00:35at last month’s Chicago Marathon; American Molly Seidel also used it in Chicago, where she ran a personal best of 2:23:07.

Siegler says it is encouraging that Maurten has tried to solve the GI problem and that any success they experience could spur other companies to research an even more effective delivery system (currently the main alternative is Amp Human’s PR Lotion, a sodium bicarbonate cream that is rubbed into the skin). But he is waiting for more data before rendering a final verdict on the Maurten Bicarb System.

“I haven’t seen any peer-reviewed papers yet come out so a bit I’m hesitant to be definitive about it,” Siegler said.

Trent Stellingwerff, an exercise physiologist and running coach at the Canadian Sport Institute – Pacific, worked with Siegler on a 2020 paper studying the effect of sodium bicarbonate on elite rowers. A number of athletes have asked him about the the Maurten Bicarb System, and some of his marathoners have used the product. Like Siegler, he wants to see more data before reaching a conclusion.

“I always follow the evidence and science, and to my knowledge, as of yet, I’m unaware of any publications using the Maurten bicarb in a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial,” Stellingwerff writes in a text to LetsRun. “So without any published data on the bicarb version, I can’t really say it does much.”

The closest thing out there right now is a British study conducted by Lewis Goughof Birmingham City University and Andy Sparks of Edge Hill University. In a test of 10 well-trained cyclists, Gough and Sparks found the Maurten Bicarb System limited GI distress and had the potential to improve exercise performance. Reuterswärd says the study, which was funded by Maurten, is currently in the review process while Gough and Sparks suggested further research to investigate their findings.

What about the runners who used sodium bicarbonate in 2023?

Klecker decided to give bicarb a shot after Maurten made a presentation to the OAC team in Boulder earlier this year. He has run well using bicarb (his 10,000 pb at The TEN) and without it (his 5,000 pb in January) and as Klecker heads into an Olympic year, he is still deciding whether the supposed benefits are worth the drawbacks, which for him include nausea and thirst. He also says that when he has taken the bicarb, his muscles feel a bit more numb than usual, which has made it more challenging for him to gauge his effort in races.

“There’s been no, Oh man I felt just so amazing today because of this bicarb,” Klecker says. “If anything, it’s been like, Oh I didn’t take it and I felt a bit more like myself.”

Klecker also notes that his wife and OAC teammate, Sage Hurta-Klecker, ran her 800m season’s best of 1:58.09 at the Silesia Diamond League on July 16 — the first race of the season in which she did not use bicarb beforehand.

A number of athletes in Mike Smith‘s Flagstaff-based training group also used bicarb this year, including Grijalva and US 5,000 champion Abdihamid Nur. Grijalva did not use bicarb in his outdoor season opener in Florence on June 2, when he ran his personal best of 12:52.97 to finish 3rd. He did use it before the Zurich Diamond League on August 31, when he ran 12:55.88 to finish 4th.“I want to say it helps, but at the same time, I don’t want to rely on it,” Grijalva says.

Almost every OAC athlete tried sodium bicarbonate at some point in 2023. Ritzenhein says the results were mixed. Some of his runners have run well while using it, but the team’s top performer, Nuguse, never used it in a race. Ritzenhein wants to continue testing sodium bicarbonate with his athletes to determine how each of them responds individually and whether it’s worth using moving forward.

That group includes Alicia Monson, who experimented with bicarb in 2023 but did not use it before her American records at 5,000 and 10,000 meters or her 5th-place finish in the 10,000 at Worlds.

“It’s not the thing that’s going to make or break an athlete,” Ritzenhein says. “…It’s a legal supplement that has the potential, at least, to help but it doesn’t seem to be universal. So I think there’s a lot more research that needs to be done into it and who benefits from it.”

The kind of research scientists like Stellingwerff want to see — double-blind, controlled clinical trials — could take a while to trickle in. But now that anyone can order Maurten’s product (it’s not cheap — $65 for four servings), athletes will get to decide for themselves whether sodium bicarbonate is worth pursuing.

“The athlete community, obviously if they feel there’s any sort of risk, they’re weighing up the risk-to-benefit ratio,” Siegler said. “The return has got to be good.”

Grijalva expects sodium bicarbonate will become part of his pre-race routine next year, along with a shower and a cup of coffee. Coffee, and the caffeine contained wherein, may offer a glimpse at the future of bicarb. Caffeine has been widely used by athletes for longer than sodium bicarbonate, and the verdict is in on that one: it works. Yet plenty of the greats choose not to use it.

Nuguse is among them. He does not drink coffee — a fact he is constantly reminded of by Ritzenhein.

“I make jokes almost every day about it,” Ritzenhein says. “His family is Ethiopian – coffee tradition and ceremony is really important to them.”

Ritzenhein says he would love it if Nuguse drank a cup of coffee sometime, but he’s not going to force it on him. Some athletes, Ritzenhein says, have a tendency to become neurotic about these sorts of things. That’s how Ritzenhein was as an athlete. It’s certainly how Ritzenhein’s former coach at the Nike Oregon Project, Alberto Salazar, was — an approach that ultimately earned Salazar a four-year ban from USADA.

Ritzenhein says he has no worries when it comes to any of his athletes using sodium bicarbonate — Maurten’s product is batch-tested and unlike L-carnitine, there is no specific protocol that must be adhered to in order for athletes to use it legally under the WADA Code. Still, there is something to be said for keeping things simple.

“Yared knows how his body feels,” Ritzenhein says. “…He literally rolls out of practice and comes to practice like a high schooler with a Eggo waffle in hand. Probably more athletes could use that kind of [approach].”

Talk about this article on our world-famous fan forum / messageboard.

by Let’s Run

Login to leave a comment

24 Hours with One of the World’s Best Marathoners

As the 2023 Boston Marathon winner and Olympian Hellen Obiri puts final touches on her build for the NYC Marathon, she’s aiming to become the seventh woman ever to win two majors in one year

Four weeks out from competing in the 2023 New York City Marathon, one of the world’s most prestigious road races, an alarm clock gently buzzes, signaling the start of the day for 33-year-old Hellen Obiri.

Despite having rested for nearly nine hours, Obiri, a two-time world champion from Kenya, says the alarm is necessary, otherwise she can oversleep. This morning’s training session of 12 miles at an easy pace is the first of two workouts on her schedule for the day as she prepares for the New York City Marathon on November 5.

The race will be her third attempt in the distance since she graduated from a successful track career and transitioned into road racing in 2022. Obiri placed sixth at her marathon debut in New York last November, finishing in 2:25:49.

“I was not going there to win. I was there to participate and to learn,” she says, adding that the experience taught her to be patient with the distance. This time around in New York, she wants to claim the title.

Obiri drinks two glasses of water, but she hasn’t eaten anything by the time she steps outside of her two-bedroom apartment in the Gunbarrel neighborhood of Boulder, Colorado.

In September 2022, the three-time Olympian moved nearly 9,000 miles from her home in the Ngong Hills, on the outskirts of Nairobi, Kenya, to Colorado. She wanted to pursue her marathon ambitions under the guidance of coach and three-time Olympian Dathan Ritzenhein, who is the fourth-fastest U.S. marathoner in history. Ritzenhein retired from professional running in 2020 and now oversees the Boulder-based On Athletics Club (OAC), a group of elite professional distance runners supported by Swiss sportswear company On.

Obiri, who was previously sponsored by Nike for 12 years before she signed a deal with On in 2022, said that moving across the world wasn’t a difficult decision. “It’s a great opportunity. Since I came here, I’ve been improving so well in road races.”

In April, Obiri won the Boston Marathon. It was only her second effort in the distance, and the victory has continued to fuel her momentum for other major goals that include aiming for gold at the 2024 Paris Olympics and also running the six most competitive and prestigious marathons in the world, known as the World Marathon Majors.

Obiri says goodbye to her eight-year-old daughter Tania and gets into a car to drive six miles to Lefthand trailhead, where she runs on dirt five days a week. She will train on an empty stomach, which she prefers for runs that are less than 15 miles. Once, she ate two slices of bread 40 minutes before a 21-mile run and was bothered by side stitches throughout the workout. Now, she is exceptionally careful about her fueling habits.

Three runners stretch next to their cars as Obiri clicks a watch on her right wrist and begins to shuffle her feet. Her warmup is purposely slow. In this part of Colorado, at 5,400 feet, the 48-degree air feels frostier and deserving of gloves, but Obiri runs without her hands covered. She is dressed in a thin olive-colored jacket, long black tights, and a black pair of unreleased On shoes.

Obiri’s feet clap against a long dirt road flanked by farmland that is dotted with horses and a few donkeys. Her breath is hardly audible as she escalates her rhythm to an average pace of six minutes and 14 seconds per mile. This run adds to her weekly program of 124 miles—some days, she runs twice. The cadence this morning is hardly tough on her lungs as she runs with her mouth closed, eyes intently staring ahead at the cotton-candy pink sunrise.

“Beautiful,” Obiri says.

Her body navigates each turn as though on autopilot. Obiri runs alone on easy days like today, but for harder sessions, up to four pacers will join her.

“They help me to get the rhythm of speed,” Obiri says. For longer runs exceeding 15 miles, Ritzenhein will bike alongside Obiri to manage her hydration needs, handing her bottles of Maurten at three-mile increments.

After an hour, Obiri wipes minimal sweat glistening on her forehead. Her breathing is steady, and her face appears as fresh as when she began the run. She does not stretch before getting into the car to return home.

The remainder of the morning is routine: a shower followed by a breakfast of bread, Weetabix cereal biscuits, a banana, and Kenyan chai—a mix of milk, black tea, and sugar. She likes to drink up to four cups of chai throughout the day, making the concoction with tea leaves gifted from fellow Kenyan athletes she sees at races.

Then, she will nap, sometimes just for 30 minutes, and other times upwards of two hours. “The most important thing is sleeping,” Obiri says. “When I go to my second run [of the day], I feel my body is fresh to do the workout. If I don’t sleep, I feel a lot of fatigue from the morning run.”

Obiri prepares lunch. Normally she eats at noon, but today her schedule is busier than usual. She cooks rice, broccoli, beets, carrots, and cabbage mixed with peanuts. Sometimes she makes chapati, a type of Indian flatbread commonly eaten in Kenya, or else she eats beans with rice.

The diet is typical among elite Kenyan athletes, and she hasn’t changed her eating habits since moving to the U.S. Obiri discovered a grocery store in Denver that offers African products, so she stocks up on ingredients like ground corn flour, which she uses to make ugali, a dense porridge and staple dish in many East African countries. She is still working through 20 pounds of flour she bought in June.

Obiri receives an hour massage, part of her routine in the early afternoon, three times a week. Usually the session is at the hands of a local physiotherapist, but sometimes Austin-based physiotherapist Kiplimo Chemirmir will fly in for a few days. Chemirmir, a former elite runner from Kenya, practices what he refers to as “Kenthaichi massage,” an aggressive technique that involves stretching muscles in short intervals.

Ritzenhein modifies Obiri’s training schedule, omitting her afternoon six-mile run so she can rest for the remainder of the day and reset for a speed workout tomorrow morning. Last fall, he took over training Obiri, who was previously coached by her agent Ricky Simms, who represented Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt, an eight-time gold medalist and world record holder, and British long distance runner Mo Farah, a four-time Olympic gold medalist.

Ritzenhein has programmed Obiri’s progression into the marathon with more volume and strength training. The meticulous preparation is essential to avoid the aftermath of her marathon debut in New York City last fall, when she was escorted off the course in a wheelchair after lacking a calculated fueling and hydration strategy. Obiri had averaged running 5:33-minute miles on a hilly route that is considered to be one of the most difficult of all the world marathon major races.

“It’s a real racing race. You have to make the right moves; you have to understand the course,” Ritzenhein says of the New York City Marathon. “We’ve changed some things in training to be a little more prepared. We’ve been going to Magnolia Road, which is a very famous place from running lore—high altitude, very hilly. We’ve been doing some long runs up there. In general, she’s got many more 35 and 40K [21 and 24 miles] runs than she had before New York last year.”

In New York, Obiri is aiming to keep pace alongside a decorated elite field that will include Olympic gold medalist Peres Jepchirchir, former women’s marathon world record holder Brigid Kosgei, and defending New York Marathon champion Sharon Lokedi, all of whom are from Kenya. In fact, Kenyan women have historically dominated at the New York City Marathon, winning nine titles since 2010 and 14 total to date, the most of any country since women were permitted to race in 1972.

“They are all friendly ladies,” Obiri says. “But you know, in sports we are enemies. It’s like a war. Everybody wants to win.”

While Obiri is finishing her massage, her daughter returns from school. Though Obiri arrived in Colorado last fall, her husband Tom Nyaundi and their daughter didn’t officially move to the U.S. until this past March. The adjustment, Obiri says, was a hard moment for the family.

“We didn’t have a car. In the U.S. you can’t move [around] if you don’t have a car. We had a very good team that helped us a lot,” Obiri says of the OAC, whom she refers to as her friends. “The athletes made everything easier for us. They were dropping my daughter to school. Coach would pick me up in the morning, take me to massage, to the store. I was lucky they were very supportive.” Now, Obiri says she and her family have fully adjusted to living in the U.S.

Obiri returns home and makes a tomato and egg sandwich before taking another nap. Usually she naps for up to two hours after lunch. Today, her nap is later and will last for two and a half hours.

Obiri doesn’t eat out or order takeaway. “We are not used to American food,” she says, smiling. “I enjoy making food at home.” Dinner is a rotation of Kenyan dishes like sukuma wiki—sautéed collard greens that accompany ugali—or pilau, a rice-based dish made with chicken, goat, or beef. This evening, she prepares ugali with sukuma wiki and fried eggs.

Before bed, Obiri says she can’t resist a nightcap of Kenyan chai. She will pray before falling asleep. And when she wakes up at 6:00 A.M. the next day, she will prepare for a track session, the intervals of which add up to nearly 13 miles: a 5K warmup, followed by 1 set of 4×200 meters at 32 seconds (200 meter jog between each rep); 3 sets of 4×200 meters at 33 seconds (200 meter jog between each rep); 5×1600 meters at 5:12 (200 meter jog between each rep) and finishing with a 5K cool down.

The workout is another one in the books that will bring her a step closer to the starting line of the race she envisions winning. “I feel like I’m so strong,” Obiri says. She knows New York will be tough. But “when I go to a race I say, ‘you have to fight.’ And if you try and give your best, you will do something good.”

Login to leave a comment

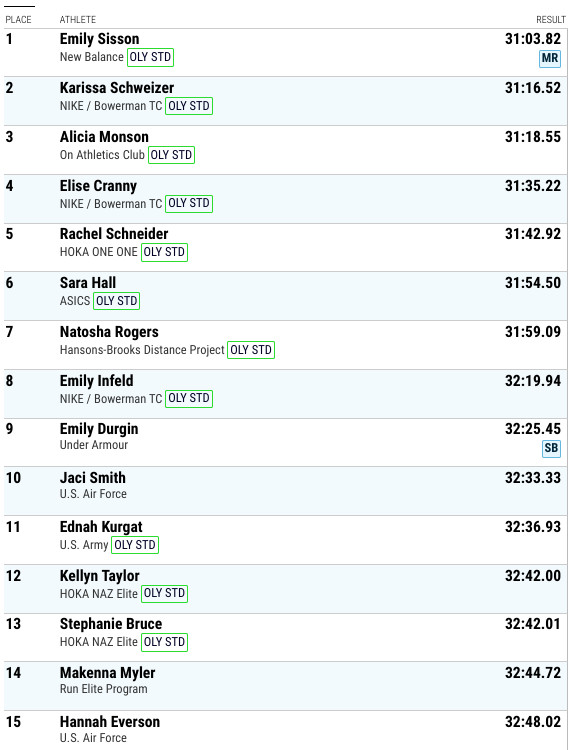

2023 US Outdoor Track and Field Championships preview from Chris Chavez

Last night was the deadline for athletes to declare their event for the 2023 U.S. Outdoor Track and Field Championships, which will take place in Eugene from July 6-9. At USAs, athletes are allowed to enter multiple events and then make a decision about which event(s) they wish to contest once entries are in, which allows those who’ve achieved multiple qualifiers to be strategic about where they want to concentrate their efforts. The top three in each event who meet the qualifying standards for the World Athletics Championships will go on to represent the United States in Budapest in August.

Reigning World champions have a “bye” to the next year’s Worlds, which means the country they represent gets to send four athletes, not three. Similarly, reigning Diamond League and World Athletics Continental Tour champs earn a bye, but if there is both a World and other champion in the same event, their country still only gets to send one extra athlete.

These complex rules lead many American World champions to make interesting choices about what events they wish to contest at USAs and how hard they want to push while still in the middle of the championship season.

MEN’S SPRINTS

– 100m world champion Fred Kerley has the bye to the world championships and will only run the 200m. Last year, he qualified for the World Championships in the 200m with a third place finish behind Noah Lyles and Erriyon Knighton. He injured his quad in the semifinal of the 200m and was unable to run the 4x100m relay for Team USA. Kerley has a season’s best of 19.92 from his win at the Doha Diamond League.

– 200m world champion Noah Lyles has the bye to the world championships and will only run the 100m. He ran a season's best of 9.95 in his outdoor opener in April. The last time he ran the 100m at a U.S. Championship, he finished seventh at the 2021 U.S. Olympic Trials final.

– 400m world champion Michael Norman is declared for the 100m and 200m at the U.S. Championships. He ran a wind-aided 10.02 (+3.0m/s wind) at the Mt. SAC Relays in April. He has not raced since a last place finish in the 200m at the Doha Diamond League in 20.65 on May 5.

WOMEN’S SPRINTS

– Sha’Carri Richardson is running the 100m and 200m. She is looking to qualify for her first World championship team. Her season’s best of 10.76 from her victory at the Doha Diamond League is the second-fastest performance in the world this year. Her season’s best of 22.07 from the Kip Keino Classic at altitude in Nairobi is No. 4 on the world list.

Only Gabby Thomas’ 22.05 from the Paris Diamond League is faster this year by an American woman. Richardson, the 2019 NCAA champion, attempted the double at USAs in both 2019 and 2022, where her highest finish was 8th in the 100m in 2019. She has yet to make a U.S. final in the 200m.

– Reigning U.S. champion Abby Steiner is only running the 200m despite qualifying in both the 100m and the 400m as well. She just ran her season’s best of 22.19 to win the NYC Grand Prix.

– As previously announced, 400m hurdles Olympic champion, World champion and world record holder Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone is running the flat 400m. She plans to make a decision after the U.S. Championships whether she will run the flat 400m (if she qualifies) or defend her 400m hurdles title in Budapest.

– NCAA record holder Britton Wilson, who ran 49.14 to become No. 4 on the U.S. all-time list, will only run the 400m and not the 400m hurdles. She hurdled at last year’s World championships and participated in the 4x400m relay.

MEN’S DISTANCE

– This year’s men’s steeplechase team should have a new look. 2016 Olympic silver medalist Evan Jager is not entered in the steeplechase. He has raced just once this outdoor season. Hillary Bor, the reigning U.S. champion who also owns the fastest steeplechase time by an American this year in 8:11.28, broke his foot earlier this spring and will miss the U.S. Championships. This is the first U.S. team he has missed since 2015. The top returner is Benard Keter, who made the Olympic team in 2021 and the World team in 2022, but he is only the fifth-fastest entrant by seed time.

– For the first time, 2021 U.S. 5000m champPaul Chelimo is entered in both the 5000m and the 10,000m. Chelimo, the 3x global medalist at 5000m, has typically only focused on the shorter event, but after his 27:12.73 performance at the Night of the 10,000m PBs in the U.K. earlier this season, he has decided to contest both events. He’s seeded No. 4 by qualifying time in both events behind Grant Fisher, Woody Kincaid, and Joe Klecker (all also double-entered).

WOMEN’S DISTANCE

– 800m Olympic and world champion Athing Mu entered the 1500m, as previously announced with coach Bobby Kersee. She has the bye to the world championships in the 800m. Her personal best of 4:16.06 is well outside the automatic standard of 4:05.00 and was achieved outside the qualifying window for the championships, but USATF rules allow for significant discretion in accepting entries from the Sports Committee chair.

– Josette Norris and On Athletics Club coach Dathan Ritzenhein have decided to focus solely on the 5000m. Norris ran 14:43.36 at Sound Running’s Track Fest in early May. That’s the second-fastest time by an American woman on the year behind her teammate and training partner Alicia Monson’s 14:34.88 at the Paris Diamond League. Monson is entered in both the 5000m and 10,000m after choosing to only contest the 10,000m last year.

– NC State’s NCAA record holder Katelyn Tuohy will only run the 5000m. Tuohy qualified for NCAAs in both the 1500m and the 5000m but ended up only running the 1500m after an uncharacteristically disappointing performance in the final.

– The Bowerman Track Club’s Elise Cranny has declared for the 1500m, 5000m and the 10,000m. The first round of the women’s 1500m is 19 minutes before the final of the 10,000m on Day 1 of the competition, so Cranny will likely scratch one or more events at a later point.

by Chris Chavez (Citius magazine)

Login to leave a comment

USATF Outdoor Championships

With an eye toward continuing the historic athletic success of 2022, USATF is pleased to announce competitive opportunities for its athletes to secure qualifying marks and prize money, including a new Grand Prix series, as they prepare for the 2023 World Athletics Championships in Budapest, Hungary.As announced a few months ago, the 2023 Indoor Championships in Nanjing, China have been...

more...Hellen Obiri: Boston Marathon winner on family sacrifice and quitting the track

As Hellen Obiri crossed the finish line to win this year's Boston Marathon, a few metres ahead was her daughter, Tania.

The double world champion was soon locked in an embrace with both her husband, Tom, and Tania as the family celebrated the surprise win in what was only her second marathon.

Speaking to BBC Sport Africa, Obiri found it all hard to describe.

"That was one good moment for me, at the finish line seeing my daughter. I cannot even explain what I felt."

The rush of emotion, which left Obiri in tears, is understandable when placed in the context of her decision to uproot her family and move them from Kenya to the United States after she quit track running to target the marathon.

"When switching to the road, I felt I needed a coach on the ground with me in training," the 33-year-old explained.

"On track you can train without a coach present and do well, but with the marathon sometimes you need a coach to watch what you are doing."

The Obiris' new home is in the city of Boulder, Colorado. But her husband and daughter only arrived a few weeks before the race in Boston. For months before that Obiri had been on her own.

'Why am I here?'

Previously a 5000m specialist who claimed world titles over the distance in 2017 and 2019, the 2018 Commonwealth title and Olympic silver medals in 2016 and 2020, Obiri made her marathon debut in New York last November.

Two months prior she had moved to the US to join her coach, retired American athlete Dathan Ritzenhein.

At the time, it meant leaving Tania and Tom back in Kenya waiting on their visas.

"It was a challenge because you don't have a family in the US. Sometimes the time difference (for) calling is not good. Maybe when you call the child is sleeping," she said.

"The most important thing is the family understands what you are going there to do, because it's a short career. The family give me a lot of time, support and a lot of encouragement."

But the pain of separation sometimes led Obiri to question her decision.

"She (Tania) was always telling me 'Mommy, I want you to come now'. When she tells you, you feel like crying, you feel you don't have morale.

"Why am I here and my baby's crying there?"

Despite her best efforts to remain focussed, New York did not go as planned as poor race tactics saw her finish sixth on her marathon debut.

"I used to run from the front in track races. I thought even in a marathon I can run in front. That cost me a lot because in marathon you can't do all the work for 42 kilometres," she admitted.

"What I learned from New York is patience, just wait for the right time so you can make a move."

Obiri proved to be a fast learner. With her family now watching on, she won her second marathon, taking more than four minutes off her time in New York.

"When you have your family around you, that means you don't have stress.

"You don't need to think about anything else. You are thinking about your family and the race and when your family is there to watch you, they give you a lot of encouragement."

Rocking life in Boulder

With the family now settled in their Colorado home, Tom has enrolled as a student. But Obiri worries about how a seven-year-old Kenyan girl will adjust to life in a different country.

"The first week was terrible for her because she didn't have friends here, it's a new environment," she said, fretting as any mother would.

"(But) Tania is so friendly. So after one week and a half, she was coming and telling mum 'I have some friends, this one and this one...'"

Obiri also had concerns when it came to Tania enrolling in school.

"I was so worried. I wondered, how will the teachers treat her as she's from Africa?

"Maybe some schoolmates will think 'You are from Africa, we don't want to be your friends.'

"I used to ask after school, 'Who wasn't nice to you? Do they treat you well?' and she said 'No, I'm okay with my friends and my teachers'."

Olympic agenda

The 2019 world cross country champion says not all of her friends understood her decision to uproot her family, but Obiri blocks out the "negative talk" to focus on her athletic ambitions and is also now at peace with her family situation.

Her next big mission, away from the six World Marathon Majors - which are Boston, New York, Chicago, London, Berlin and Tokyo - is to try to complete her list of global titles, filling the one very obvious hole in her list of achievements.

"I will work hard to be in the Kenya (marathon) team for Paris 2024."

"I have won gold medals in World Championships so I'm looking for Olympic gold. It is the only medal missing in my career."

by Sports Africa

Login to leave a comment

Boston Marathon

Among the nation’s oldest athletic clubs, the B.A.A. was established in 1887, and, in 1896, more than half of the U.S. Olympic Team at the first modern games was composed of B.A.A. club members. The Olympic Games provided the inspiration for the first Boston Marathon, which culminated the B.A.A. Games on April 19, 1897. John J. McDermott emerged from a...

more...Eliud Kipchoge is human afterall

Eliud Kipchoge came to Boston seeking to add the world’s most storied annual marathon to his unrivaled trophy case. He will leave with a sixth-place result and questions about whether he can achieve two outstanding, unprecedented goals.

“I live for the moments where I get to challenge the limits,” was posted on Kipchoge’s social media four hours after he finished. “It’s never guaranteed, it’s never easy. Today was a tough day for me. I pushed myself as hard as I could but sometimes, we must accept that today wasn’t the day to push the barrier to a greater height.”

Kipchoge was dropped in the 19th mile in his Boston Marathon debut in the middle of the race’s famed hills. He finished 3 minutes, 29 seconds behind fellow Kenyan Evans Chebet, who clocked 2:05:54 and became the first male runner to repeat as Boston champion since 2008.

“I did not observe Kipchoge,” Chebet said of what happened, according to the Boston Athletic Association. “Eliud was not so much of a threat because the bottom line was that we trained well.”

It marked just Kipchoge’s third defeat in 18 career marathons, a decade-long career at 26.2 miles that’s included two world record-breaking runs and two Olympic gold medals.

Kipchoge, 38, hopes next year to become the first person to win three Olympic marathons, but major doubt was thrown on that Monday, along with his goal to win all six annual World Marathon Majors. Kipchoge has won four of the six, just missing Boston and New York City, a November marathon that he has never raced.He skipped his traditional spring marathon plan of racing London to go for the win in Boston, the world’s oldest annual marathon dating to 1897.

Kipchoge has yet to speak to media, but may be asked whether a failed water bottle grab just before he lost contact with a leading pack of five contributed to his first defeat since he placed eighth at the 2020 London Marathon. Boston’s weather on Monday, rainy, was similar to London in 2020.

Kipchoge’s only other 26.2-mile loss was when he was runner-up at his second career marathon in Berlin in 2013.

He is expected to race two more marathons before the Paris Games. Kipchoge will be nearly 40 come Paris, more than one year older than the oldest Olympic champion in any running event, according to Olympedia.org. Kenya has yet to name its three-man Olympic marathon team.

“In sports you win and you lose and there is always tomorrow to set a new challenge,” was posted on Kipchoge’s social media. “Excited for what’s ahead.”

Kenyan Hellen Obiri won Monday’s women’s race in 2:21:38, pulling away from Ethiopian Amane Beriso in the last mile.

Obiri, a two-time world champion and two-time Olympic medalist in the 5000m on the track, made her marathon debut in New York City last November with a sixth-place finish. She was a late add to the Boston field three weeks ago after initially eschewing a spring marathon.

“I didn’t want to come here, because my heart was somewhere else,” said Obiri, who is coached in Colorado by three-time U.S. Olympian Dathan Ritzenhein. “But, my coach said I should try and go to Boston.”

Emma Bates was the top American in fifth in the second-fastest Boston time for an American woman ever, consolidating her status as a favorite to make the three-woman Olympic team at next February’s trials in Orlando. Emily Sisson and Keira D’Amato, who traded the American marathon record last year, didn’t enter Boston.

“I expected myself to be in the top five,” said the 30-year-old Bates, who feels she can challenge Sisson’s American record of 2:18:29, if and when she next races on a flat course.

The next major marathon is London on Sunday, headlined by women’s world record holder Brigid Kosgei of Kenya, Tokyo Olympic champion Peres Jepchirchir of Kenya and Olympic 5000m and 10,000m champion Sifan Hassan of the Netherlands in her 26.2-mile debut.

by Olympic Talk

Login to leave a comment

Boston Marathon

Among the nation’s oldest athletic clubs, the B.A.A. was established in 1887, and, in 1896, more than half of the U.S. Olympic Team at the first modern games was composed of B.A.A. club members. The Olympic Games provided the inspiration for the first Boston Marathon, which culminated the B.A.A. Games on April 19, 1897. John J. McDermott emerged from a...

more...Two-time Olympic medalist Hellen Obiri joins Boston Marathon elite list

On Wednesday, Hellen Obiri, a two-time Olympic medalist from Kenya, was announced as a late addition to the women’s elite field at the 2023 Boston Marathon on April 17, joining an already star-studded field featuring world championship and Olympic medalists.

This will be the second marathon of Obiri’s 12-year professional career. Her debut came last fall in New York, where she finished sixth in 2:25:49.

Last fall, Obiri moved from Kenya to Boulder, Colo., joining forces with coach Dathan Ritzenhein and On Athletics Club. She started her 2023 season with a bang, winning UAE’s RAK Half Marathon in February in 65:05 and setting a course record of 67:21 at the NYC Half two weeks ago. Obiri owns the fifth-fastest half-marathon result in history, with a personal best of 1:04:22 from February 2022.

This past week, Obiri made headlines on Strava as she did a 25-mile long run at 2:25 marathon pace with her OAC training partner Joe Klecker of the U.S. (who posted the run). According to Klecker’s Strava caption, Obiri hit 40K in 2:18 (even with a 7:14 first mile).

Obiri’s winning streak has indicated that she’s in great shape and now comes into Boston as one of the favourites in the women’s elite field. She will be challenged by 2022 world marathon champion Gotytom Gebreslase, 2020 Tokyo Marathon champion Lonah Salpeter and the woman who beat Obiri last fall in NYC, Sharon Lokedi.

We are less than three weeks away from the 127th Boston Marathon.

by Running Magazine

Login to leave a comment

Boston Marathon

Among the nation’s oldest athletic clubs, the B.A.A. was established in 1887, and, in 1896, more than half of the U.S. Olympic Team at the first modern games was composed of B.A.A. club members. The Olympic Games provided the inspiration for the first Boston Marathon, which culminated the B.A.A. Games on April 19, 1897. John J. McDermott emerged from a...

more...Here's Why It Feels Like Every Elite Runner Is Changing Sponsors Right Now

Tim Tollefson celebrated the new year shoveling a lot of snow, dreaming about a summer of possibility, and changing his shoes.

After six years with Hoka, Tollefson, 37, the well-known elite American ultrarunner from Mammoth Lakes, California, signed a new multi-year sponsorship deal with Craft. It might seem like a curious move this time of the year, but, in reality, most athlete sponsorship contracts in running are one-year partnerships that end on December 31. That typically gives brands the upper hand in these situations because they can have an easy out whenever an athlete doesn't have a great year of results, or they no longer fit with their marketing goals. It always comes down to the money, though sometimes it's in the athlete's best interests to start fresh, to leverage their recent results and social media platform to find a better deal with a brand that better fits their racing goals.

Because there are more brands partnering runners than ever before, and presumably more sponsorship money available, top-tier distance runners who are still at the top of their game-like Tim Tollefson, Allie McLaughlin, Josette Norris, Paige Stoner, David Ribich, Dani Moreno, Erin Clark, Natosha Rogers, Colin Bennie, Dillon Maggard, Camille Herron, and others-have been able to seek out new opportunities to continue their careers with the necessary support.

The terms of the newly signed deals haven't been disclosed, but there is a huge range in pay for professional distance runners-roughly $15,000 on the low end for a partially sponsored trail runner without significant international results, to $300,000 at the high end for a top-tier marathoner with Marathon Majors podium results. Certainly that means some live a life of luxury, while others are forced to work part-time jobs and pinch pennies to get by.

But there are also often signing bonuses, as well as premiums paid for earning appearance fees, major victories, global medals, podium finishes, breaking records, and other incentives, so running faster can be a fast track to a boost in income. However, most athletes are considered independent contractors, and many have to pay for their own healthcare, body work, and travel, depending on the details of their brand partnership.

"You start getting an idea of who's going to be available, for one reason or other, in the last few months of the year, and that's when brands and athletes start talking," said Mike McManus, Hoka's global sports marketing director. "As an athlete, you're as valuable as whatever money anyone wants to give you, but it's a process and all about negotiating. Sometimes you can match the money being offered; sometimes it just doesn't make sense for the partnership."

What Tollefson liked about Craft was similar to what he liked about Hoka six years ago-an upstart brand ready to make an impact in trail racing, its new line of trail shoes, and the trail community overall. Craft sees Tollefson as a runner with name recognition and several significant race wins in the past three years, not to mention a leader in the sport who started the Mammoth Trail Fest last year.

"This [new partnership with Craft] has reignited my deep passion for the sport and has reminded me of the things I want to accomplish," he said. "It's almost like a start-up situation led by passionate people who are excited to make an impact and want to support the people who are along for the journey. Curiosity drives me and I like a challenge. I know I am going to have some lifetime achievements ahead."

More Big Moves in Trail and Ultra

After an extraordinary year of racing on the trails, Allie McLaughlin changed from On to Hoka as her primary sponsor. The charismatic 32-year-old from Colorado Springs won the daunting Mount Marathon race in Alaska, placed among the top five in several Golden Trail Series races, and won both gold and bronze medals in the inaugural World Mountain and Trail Running World Championships in Thailand. She'll be representing the U.S. in this year's World Championships in Austria, in June, while also returning to the OCC 54K race, as part of the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB) festival in Chamonix, in August.

"It was really interesting to see how much trail means to them [Hoka], not only with their sponsorship of UTMB, but in general how they're helping push the sport forward," said McLaughlin, who had been with On since 2021. "There are a lot of reasons I like what Hoka is doing, but ultimately, the emphasis they're putting on the team and their athletes is really exciting."

Other trail and ultrarunners who have switched brands include Erin Clark, who finished 7th at last year's CCC, who left Hoka to sign with Nike, even though her partner, Adam Peterman, the 2022 Western States 100 champion and ultrarunning world champion, re-signed with Hoka.

Spanish trail runner Sara Alonso has changed from Salomon to ASICS, while Craft also signed Arlen Glick, a prolific 100-mile specialist from Ohio, and Mimmi Kotka, a Swedish runner with numerous podium finishes in Europe, to its team. Meanwhile, previously unsponsored American trail runners Tabor Hemming (Salomon) and Dan Curts (Brooks) are among those who have signed new deals.

Meanwhile, Dani Moreno, a world-class mountain runner from Mammoth Lakes, California, and Camille Herron, a record-setting ultrarunner from Warr Acres, Oklahoma, are both also leaving Hoka for yet-to-be-announced brands that offered better deals.

Bigger Transitions for Road and Track Runners

For track athletes and marathon runners, a change of shoe brands is often a more involved change, mostly because it often means changing training groups and coaches, too.

For example, Josette Norris, the fifth-place finisher in the 1,500m at the 2022 World Athletics Indoor Championships, not only switched from Reebok to On, but she left Reebok's Virginia-based Boston Track Club, and coach Chris Fox, and moved west to Boulder, Colorado, to join the On Athletics Club under Dathan Ritzenhein.

Similarly, David Ribich, one of the best American mile runners on the track last year, switched from the Seattle-based Brooks Beasts track club to the Nike-backed Union Athletics Club under Pete Julian.

Colin Bennie, the top American finisher in the Boston Marathon in 2021-previously with Reebok but unsponsored last year-signed with the Brooks Beasts but will be training on his own in San Francisco. Dillon Maggard, who was second at the U.S. cross country championships and ninth in 3,000m at the indoor world championships in 2022, is returning to Seattle to train with the Brooks Beasts, after being unsponsored last year. Natosha Rogers, who was a finalist in the 10,000m at last summer's World Athletics Championships in Eugene, Oregon, has changed from Brooks to Puma, but will continue to train on her own in Colorado. Middle-distance runner Cruz Culpepper, after short stints at the University of Washington and the University of Mississippi, gave up his remaining college eligibility to sign with Hoka and its NAZ Elite (NAZ) team.

Last summer, Paige Stoner left the Virginia-based Reebok group and Fox, her longtime coach, to train in Flagstaff, Arizona, partially because she didn't have other marathoners to train with on a regular basis in Charlottesville. She increased her volume last fall training with Sarah Pagano and Emily Durgin and won the U.S. championship at the California International Marathon in December with a course record of 2:26:02, her debut at the distance.

In January, Stoner parlayed that into a new deal with Hoka, as she also joined the Flagstaff-based Northern Arizona Elite and will be training with a group of strong marathoners-including Aliphine Tuliamuk, Alice Wright, Kellyn Taylor, and the recently unretired Stephanie Bruce-under the guidance of coaches Alan Culpepper, Ben Rosario, and Jenna Wreiden.

"I was especially drawn to NAZ because they have proven to be a powerhouse in the marathon, which will likely be my primary focus in the years to come," Stoner said. "I believe the team has all of the tools it takes to compete at the highest level in the sport, and I am eager to begin this new chapter."

Learning the Ropes

For track and road running, the path to success for elite-level, post-collegiate athletes typically includes earning a sponsorship right after the track season in June and joining a sponsored training group and coach. From there, it's all about improving times and placing high in U.S. championship races, with hopes of becoming fast enough to earn a spot in elite track meets in Europe or one of the World Marathon Majors.