Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #2020 Olympic Trials

Today's Running News

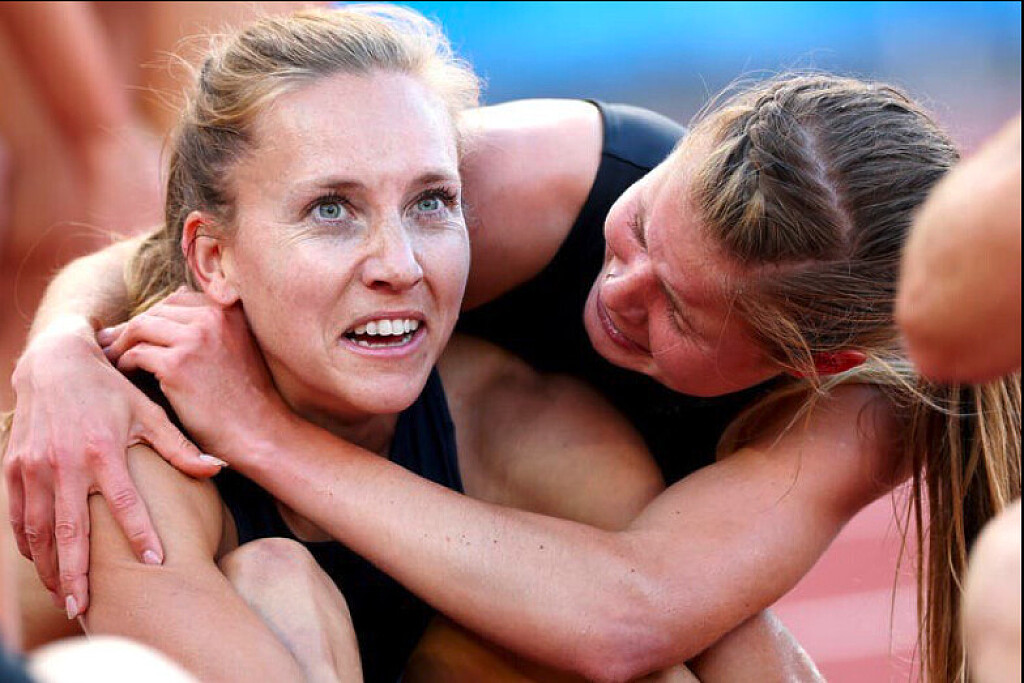

This 31-Year-Old Runner Is a Mom and an Olympian

Buoyed by her faith, motherhood, and family, Marisa Howard never relinquished her dream of becoming an Olympian

As a young girl, Marisa Howard dreamed about becoming an Olympian one day. But her focus was on another Olympic sport, gymnastics. She had no idea what the 3,000-meter steeplechase even was.

She also had no idea she’d be a mom when the dream actually came true.

Over the last two decades, Marisa, 31, has gone through numerous highs and lows, near-misses, injuries, a lack of sponsor support, and joyful life changes—most notably giving birth to son, Kai, in 2022. But the steeplechaser from Boise, Idaho, never let go of the dream. Relying on her faith, a strong family support system, and the frugal but full life she shares with her husband, Jeff, the dream came true on June 27 with a third-place finish in the steeplechase at the U.S. Olympic Trials in Eugene, Oregon.

After chipping away at her craft for three Olympic cycles, Marisa ran the race of her life—finishing with a 15-second personal best of 9 minutes and 7.14 seconds—to earn a spot on Team USA.

Her dream of running for Team USA in the Olympics officially materialized on August 4 when she lined up to race in the prelims of the 3,000-meter steeplechase in Paris. She ran with the lead pack in her heat as long as she could, but with two laps to go she slid to seventh and finished in that position in 9:24.78, missing the chance to advance to the August 6 final by two places and about seven seconds.

“I think it just becomes a lot more real when you see people that have been kind of knocking on the door for years and finally break through. It’s like, ‘Wow, we’re human and we can do it.’ Dreams do come true,” Marisa said. “I was six or seven or eight years old when this Olympic dream was born, and I plan on competing until he’s that age, hopefully, to show him what it’s like to do hard things and chase your dreams. I think it’ll be cool in 10 years when I show Kai these videos and be able to tell him, “Look at what Mommy did when you were two.”

In between making the team in late June and arriving in Paris in late July, Marisa’s life returned to normal—as if being a mom with a 2-year-old is ever normal, or at least consistent, on a day-to-day basis. That month included rough bouts of stomach flu for her and her son, the continued day-to-day management of Kai with Jeff, juggling workouts with childcare help from family and friends, reestablishing normal sleep patterns for everyone, and of course, finalizing travel plans to get the family to Paris.

It all came with a humbling reminder of the perspective that has been the bedrock of Marisa’s postpartum revival as an athlete.

“The day after I qualified, we were driving back home to Idaho and we were all tired. Kai was exhausted and screaming in the car, and I told my husband, ‘He doesn’t care that I’m an Olympian, he just wants food and sleep and, really, I’m just mom,’” she said. “It’s humbling—there’s nothing more humbling than taking care of your sick baby—and I think as a parent, we’re humbled every single day, and we come up short sometimes despite doing the best we can, but I’m thankful that there’s grace and forgiveness. I think it makes those high moments so much sweeter.”

Marisa is part of a new wave of elite runners that aren’t putting their family plans on hold due to their career, and one of several moms who competed at the U.S. Olympic Trials. Stephanie Bruce raced the 10,000 meters just nine months postpartum after giving birth to her daughter, Sophia, in September 2023, while Kate Grace ran strong preliminary and semifinal 800-meter races to advance to the final of that event just 15 months after giving birth to son, River, in March 2023.

Elle St. Pierre gave birth to her son, Ivan, at about the same time, and returned to racing six months postpartum, finishing seventh in a speedy 4:24 at the Fifth Avenue Mile in New York City. That was just the beginning for St. Pierre, who broke the American indoor record in the mile (4:16.41) in January then won the gold medal in the 3,000 meters at the indoor world championships in Glasgow in March. At the Olympic Trials, Pierre won the 5,000 meters and placed third in the 1500, qualifying for Team USA in both events, even though she declined the Olympic entry for the 5,000.

After Howard gave birth to Kai in late May 2022, she began doing pelvic floor therapy along with general strength training and some easy jogging. By the time she started running in earnest that fall, she was surprised at how quickly her aerobic fitness came back to her.

“What’s really surprised me is that I’m able to run paces that I never hit before pregnancy with the same amount or less effort,” she says. “My aerobic engine has just gotten so strong. You do see women come back stronger, but it’s a wide range of how long it takes them to come back. ”

When she returned to the track, she was aiming for a top-three finish at the 2023 U.S. championships to qualify for the world championships in Budapest. She made it to the final and was in third place with two laps to go, but just didn’t have the closing speed. However, she did get the Olympic Trials standard by clocking a near-PR of 9:22.73, demonstrating she was just as fast as her pre-pregnancy self despite limited training and two years away from racing.

By late 2023 and early 2024, Pat McCurry, Marisa’s coach since college, was able to add more volume and intensity to her training, setting up what he thought would be her best season yet. And while Marisa admittedly didn’t race as well as hoped in her races before the Olympic Trials, McCurry knew she was capable of great things.

“She was on a different level once we got back to that base fitness post-pregnancy, and I think that’s what’s paid off in massive fitness dividends,” said McCurry, who has coached Marisa on Idaho Afoot training group since 2015. “The racing didn’t look amazing from the outside. The training was spectacular. We were doing things in training since January that we’ve never done before—just the level of intensity and volume we were sustaining was stellar.”

Marisa picked up running at Pasco High School in Washington, and carried on with the dream at Boise State University. There, she also met Jeff Howard, a Boise State runner who held the school record in the 10,000 meters. But more important than their common athletic passion, they shared the same Christian values that were the foundation of her life. They married in the summer of 2013 just after he graduated. He eventually took a job as a high school teacher at a nearby school, while she blossomed into a three-time NCAA Division I All-American for the Broncos, notching a runner-up finish at the 2014 NCAA championships and fourth-place finish the following year as a senior.

After she graduated, she picked up a small sponsorship deal with women’s apparel brand Oiselle and set her sights on the 2016 U.S. Olympic Trials . She got injured and missed the trials that year. But Howard and her husband bought a house in Boise and started their family life in earnest. That added stability, along with the guidance of McCurry, who she began working with in 2016, allowed her to dig deeper into training and continue to make progress in the steeplechase, lowering her personal best to 9:30.92 at a race in Lapinlahti, Finland.

The Oiselle sponsorship evaporated after about three years but that didn’t seem to matter. She and Jeff were living frugally and loving life, especially because, by then, most of their family had moved to Boise. Marisa had two aunts who had lived in the area before she went to college, and Jeff’s parents moved to town shortly after they were married. Marisa’s parents, and later her best friend, Marianne Green, also picked up their roots and relocated to town.

The ensuing years brought a variety of highs and lows—several near-miss fifth place finishes at U.S. championships, a silver medal at the 2019 Pan American Games, a few injuries that delayed her progress, a breakthrough eight-second PR in the semifinals of the 2020 Olympic Trials, and, of course, welcoming Kai into the world in 2022.

What makes Marisa’s situation especially challenging is that she’s run competitively without a traditional sponsor since 2017, more or less collectively bootstrapping the dream on her husband’s high school teacher’s salary and working part-time as a schol nurse and as a coach. (She will officially join the Boise State staff as an assistant coach after the Olympics.) She often stays with friends when she travels to races and says she’s grateful to the meet directors who have flown her out to race, put her up in hotels, and also paid her to pace races.

She also earned USATF Foundation grants and in 2022 was the recipient of a $10,000 grant to offset child care expenses from a program sprinting legend Allyson Felix organized through Athleta’s Power of She Fund and the Women’s Sports Foundation. Marisa competed at the 2024 Olympic Trials as part of the Tracksmith Amateur Support Program, which provides a small quarterly stipend, running apparel, and shoes to about 40 athletes in all disciplines of track and field.

“We’ve found ways to make it work. We drive used cars, and we refinanced in 2020, so thankfully our mortgage is very low,” she says. “So really a lot of my expenses are just shoes, a little bit of travel, coaching fees, gym fees, and things like that. But it does add up. But thankfully we live well within our means and are able to do it. As I’ve said before, the Lord always provides.”

But even with that support and her continued progress, Marisa entered the Olympic Trials as a dark horse contender to make Team USA. And that’s despite knowing that Emma Coburn and Courtney Frerichs, the top stars of the event for the past 10 years, were sidelined with injuries. She hadn’t run great in her races leading up to the trials, and her confidence was waning, McCurry says.

“I felt like not having a full contract [from a shoe sponsorship] had kind of eroded away at some of her confidence, and she was starting to have a little bit of imposter syndrome at races,” says McCurry. “We just had a really firm talk where I was like, damn it, you’re better than this,” he says. “Not we, not the training, you, Marissa Howard, are better than this.”

That pep talk was just what she needed. It helped remind Marisa about her bigger purpose, just as much as packing diapers, toys, and pajamas for Kai did before she and Jeff made the eight-hour drive to Eugene for the Olympic Trials.

In her semi-final heat at the trials on June 24, Marisa ran aggressively and finished second behind Gabbi Jennings in 9:26.38. After the race, she said she was looking forward to the final, but, for the moment, was most interested in making sure Kai got to bed on time.

Running with purpose and caring for her son emboldened her for the final, where she ran with conviction among the top five before moving into the lead briefly with a lap to go. In what was a thrilling final lap, Val Constien retook the lead and sprinted to victory down the homestretch in an Olympic Trials-record 9:03.22, followed by a surging Courtney Wayment (9:06.50) and a determined Marisa (9:07.14) as the top nine finishers all set new personal bests.

“My husband and I talk about competitive greatness: You want to rise to the occasion when everyone else is at their best. So it’s like, gosh, I was able to do it! I think a lot of it for me has always been about having my priorities in place. I’m a Christian first, and then a wife, and then a mom, and then a runner. And I think if I keep those in that line, that’s where I see success,” Marisa says.

“I’ve sat next to gold medalists and other high-level athletes in chapels before U.S. championship races and they’ve told me, ‘I’ve won that gold medal and it doesn’t fill that void in my heart.’ And just knowing that a medal or success isn’t going to change you, ultimately, you have to be secure in who you are. So just remembering where my priorities lie helps to kind of keep me grounded.”

Login to leave a comment

What You Need to Know About the U.S. Track and Field Olympic Trials

From June 21-30, more than 900 runners, throwers, and jumpers will put it all on the line for a chance to compete for Team USA at the Paris Olympics

The U.S. Track and Field Olympic Trials is a showcase of hundreds of America’s best track and field athletes who will be battling for a chance to qualify for Team USA and compete in this summer’s Paris Olympics. For many athletes competing in Eugene, simply making it on to the start line is a life-long accomplishment. Each earned their spot by qualifying for the trials in their event(s). The athlete qualifier and declaration lists are expected to be finalized this week.

But for the highest echelon of athletes, the trials defines a make-or-break moment in their career. Only three Olympic team spots (in each gender) are available in each event, and given the U.S. depth in all facets of track and field—sprints, hurdles, throws, jumps, and distance running events—it’s considered the world’s hardest all-around team to make. How dominant is the U.S. in the world of track and field? It has led the track and field medal count at every Olympics since 1984.

At the trials, there are 20 total events for women and men—10 running events from 100 meters to 10,000 meters (including two hurdles races and the 3,000-meter steeplechase), four throwing events (discus, shot put, javelin, and hammer throw), four jumping events (long jump, triple jump, high jump, and pole vault), the quirky 20K race walking event, and, of course, the seven-event heptathlon (women) and the 10-event decathlon (men).

(At the Olympics, Team USA will also compete in men’s and women’s 4×100-meter and 4×400-meter relays, plus a mixed gender 4×400, and a mixed gender marathon race walk. The athletes competing on these teams will be drawn from those who qualify for Team USA in individual events, along with alternates who are the next-best finishers at the trials.

There’s also the Olympic marathon, but the U.S. Olympic Trials Marathon was held on February 3 in Orlando, Florida, to give the athletes enough time to recover from the demands of hammering 26.2 miles before the big dance in Paris.

Although some countries arbitrarily select their Olympic track and field teams, the U.S. system is equitable for those who show up at the Olympic Trials and compete against the country’s best athletes in each particular event. There’s just one shot for everyone, and if you finish among the top three in your event (and also have the proper Olympic qualifying marks or international rankings under your belt), you’ll earn the opportunity of a lifetime—no matter if you’re a medal contender or someone who burst onto the scene with a breakthrough performance.

The top performers in Eugene will likely be contenders for gold medals in Paris. The list of American stars is long and distinguished, but it has to start with sprinters Sha’Carri Richardson and Noah Lyles, who will be both competing in the coveted 100 and 200 meters. Each athlete won 100-meter titles at last summer’s world championships in Budapest and ran on the U.S. gold-medal 4×100 relays. (Lyles also won the 200) Each has been running fast so far this spring, but more importantly, each seems to have the speed, the skill, and swagger it takes to become an Olympic champion in the 100 and carry the title of the world’s fastest humans.

But first they have to qualify for Team USA at the Olympic Trials. Although Lyles is the top contender in the men’s 100 and second in the world with a 9.85-second season’s best, five other U.S. athletes have run sub-10-second efforts already this season. Richardson enters the meet No. 2 in the U.S. and No. 3 in the world in the women’s 100 (10.83), but eight other Americans have also broken 11 seconds. That will make the preliminary heats precariously exciting and the finals (women’s on June 22, men’s on June 23) must-see TV.

There are five returning individual Olympic gold medalists competing in the U.S. Olympic Trials with the hopes of repeating their medals in Paris—Athing Mu (800 meters), Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone (400-meter hurdles), Katie Moon (pole vault), Vallarie Allman (discus), and Ryan Crouser (shot put)—but there are more than a dozen other returning U.S. medalists from the Tokyo Olympics, as well as many more from the 2023 world championships, including gold medalists Chase Ealey (shot put), Grant Holloway (110-meter hurdles), Laulauga Tausaga (discus), and Crouser (shot put).

The most talented athlete entered in the Olympic Trials might be Anna Hall, the bronze and silver medalist in the seven-event heptathlon at the past two world championships. It’s an epic test of speed, strength, agility, and endurance. In the two-day event, Hall and about a dozen other women will compete in the 100-meter hurdles, high jump, shot put, 200 meters, long jump, javelin throw, and 800 meters, racking up points based on their performance in each event. The athletes with the top three cumulative totals will make the U.S. team. At just age 23, Hall is poised to contend for the gold in Paris, although Great Britain’s Katarina Johnson-Thompson, the world champion in 2019 and 2023, is also still in search of her first Olympic gold medal after injuries derailed her in 2016 and 2021.

If you can find your way to Eugene—and can afford the jacked-up hotel and Airbnb prices in town and nearby Springfield—you can watch it live in person at Hayward Field. Rebuilt in 2021, it’s one of the most advanced track and field facilities in the world, with an extremely fast track surface, a wind-blocking architectural design, and 12,650 seats that all offer great views and close-to-the-action ambiance. Tickets are still available for most days, ranging from $45 to $195.

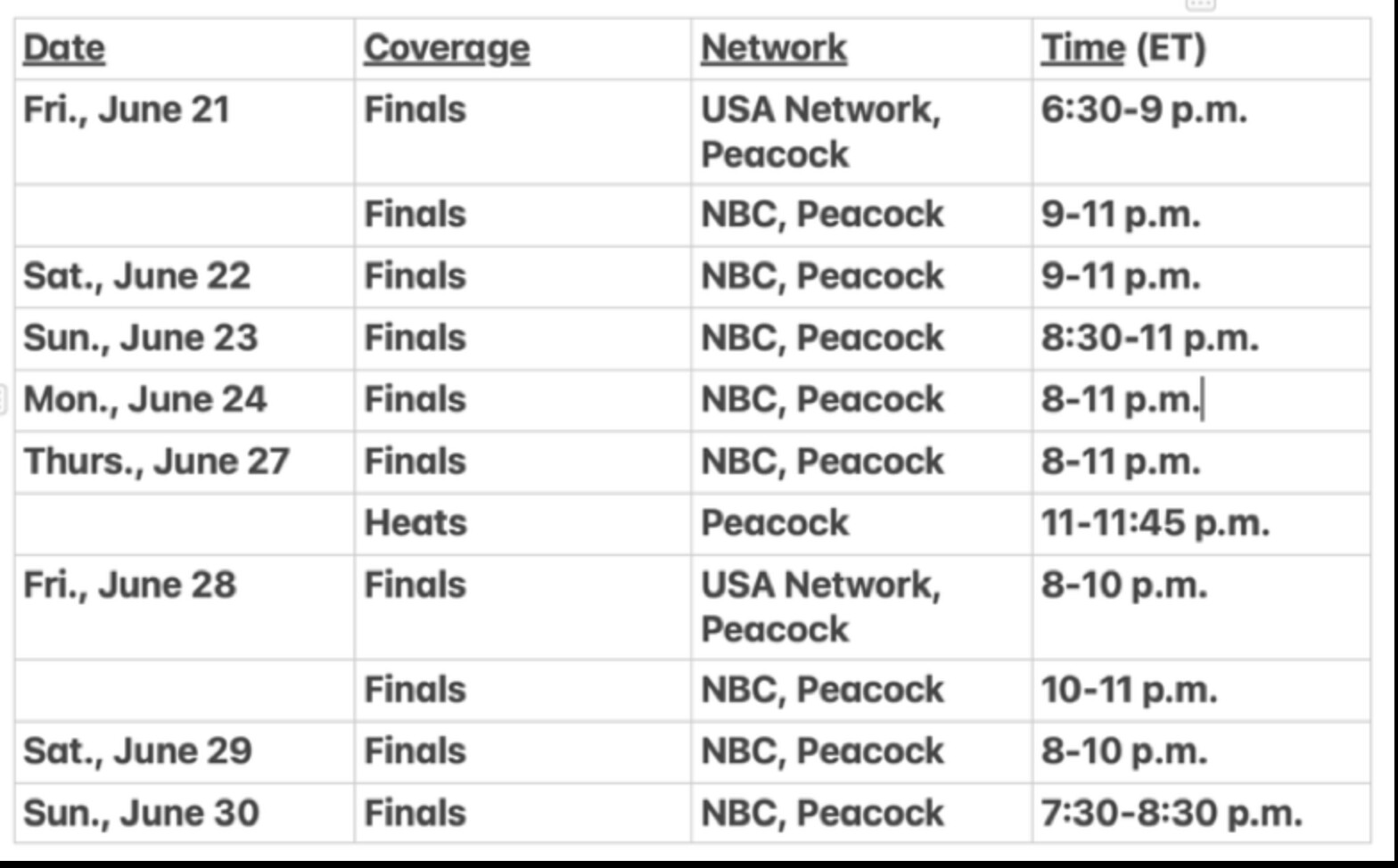

If you can’t make it to Eugene, you can watch every moment of every event (including preliminary events) via TV broadcasts and livestreams. The U.S. Olympic Trials will be broadcast live and via tape delay with 11 total broadcast segments on NBC, USA Network, and Peacock. All finals will air live on NBC during primetime and the entirety of the meet will be streamed on Peacock, NBCOlympics.com, NBC.com and the NBC/NBC Sports apps.

The Olympic Trials will be replete with young, rising stars. For example, the men’s 1500 is expected to be one of the most hotly contested events and the top three contenders for the Olympic team are 25 and younger: Yared Nuguse, 25, the American record holder in the mile (3:43.97), Cole Hocker, 23, who was the 2020 Olympic Trials champion, and Hobbs Kessler, 21, who turned pro at 18 just before racing in the last Olympic Trials. Sprinter Erriyon Knighton, who turned pro at age 16 and ran in the Tokyo Olympics at age 17, is still only 20 and already has two world championships medals under his belt. Plus, the biggest track star from the last Olympics, Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone, is aiming for her third Olympics and third Olympic gold (she won the 400-meter hurdles and was on the winning 4×400 relay in Tokyo), and she’s only 24.

Several young collegiate stars could earn their place on the U.S. team heading to Paris after successful results in the just-completed NCAA championships. Leading the way are double-NCAA champions McKillenzie Long, 23, a University of Mississippi senior who enters the trials ranked sixth in the world in the 100 (10.91) and first in the 200 (21.83), and Parker Valby, a 21-year-old junior at the University of Florida, who ranks fifth in the U.S. in the 5,000 meters (14:52.18) and second in the 10,000 meters (30:50.43). Top men’s collegiate runners include 5,000-meter runner Nico Young (21, Northern Arizona University), 400-meter runner Johnnie Blockburger (21, USC), and 800-meter runners Shane Cohen (22, Virginia) and Sam Whitmarsh (21, Texas A&M).

It’s very likely. Elle St. Pierre is the top-ranked runner in both the 1500 and the 5,000, having run personal bests of 3:56.00 (the second-fastest time in U.S. history) and 14:34.12 (fifth-fastest on the U.S. list) this spring. Although she’s only 15 months postpartum after giving birth to son, Ivan, in March 2023, the 29-year-old St. Pierre is running better and faster than ever. In January, she broke the American indoor record in the mile (4:16.41) at the Millrose Games in New York City, then won the gold medal in the 3,000 meters at the indoor world championships in Glasgow in March.

St. Pierre could be joined by two world-class sprinters. Nia Ali, 35, the No. 2 ranked competitor in the 100-meter hurdles and the 2019 world champion, is a mother of 9-year-old son, Titus, and 7-year-old daughter, Yuri. Quanera Hayes, 32, the eighth-ranked runner in the 400 meters, is the mother to 5-year-old son, Demetrius. Hayes, a three-time 4×400 relay world champion, finished seventh in the 400 at the Tokyo Olympics.

Meanwhile, Kate Grace, a 2016 Olympian in the 800 meters who narrowly missed making Team USA for the Tokyo Olympics three years ago, is back running strong at age 35 after a two-year hiatus during which she suffered from a bout of long Covid and then took time off to give birth to her son, River, in March 2023.

No, unfortunately, there are a few top-tier athletes who are hurt and won’t be able to compete. That includes Courtney Frerichs (torn ACL), the silver medalist in the steeplechase at the Tokyo Olympics in 2021; Alicia Monson (torn medial meniscus), a 2020 Olympian in the 10,000 meters, the American record holder in the 5,000 and 10,000 meters, and the fifth-place finisher in the 5,000 at last year’s world championships; and Joe Klekcer (torn adductor muscle), who was 16th in the Tokyo Olympics and ninth in the 2022 world championships in the 10,000. Katelyn Tuohy, a four-time NCAA champion distance runner for North Carolina State who turned pro and signed with Adidas last winter, is also likely to miss the trials due to a lingering hamstring injury. There is also some doubt about the status of Athing Mu (hamstring), the Tokyo Olympics 800-meter champion, who has yet to race in 2024.

Meanwhile, Emma Coburn, a three-time Olympian, 2017 world champion, and 10-time U.S. champion in the 3,000-meter steeplechase, broke her ankle during her season-opening steeplechase in Shanghai on April 27. She underwent surgery a week later, and announced at the time that she would miss the trials, but has been progressing quickly through her recovery. If both she and Frerichs miss the meet, it will leave the door wide open for a new generation of steeplers—including 2020 Olympian Valerie Constein, who’s back in top form after tearing her ACL at a steeplechase in Doha and undergoing surgery last May.

The U.S. earned 41 medals in track and field at the 2020 Paralympic Games in Tokyo—including 10 gold medals—which ranked second behind China’s 51. This year’s Paralympics will follow the Olympics from August 28-September 8 in Paris.

The 2024 U.S. Paralympic Trials for track and field will be held from July 18-20 at the Ansin Sports Complex in Miramar, Florida, and Paralympic stars Nick Mayhugh, Brittni Mason, Breanna Clark, Ezra Frech, and Tatyana McFadden are all expected to compete.

In 2021 at the Tokyo Paralympics, Mayhugh set two new world records en route to winning the 100 meters (10.95) and 200 meters (21.91) in the T-37 category, and also took the silver medal in the 400 meters (50.26) and helped the U.S. win gold and set a world record in the mixed 4×100-meter relay (45.52). Clark returns to defend her Paralympic gold in the T-20 400 meters, while McFadden, a 20-time Paralympic medalist who also competed on the winning U.S. mixed relay, is expected to compete in the T-54 5,000 meters (bronze medal in 2021).

Livestream coverage of the U.S. Paralympic Trials for track and field will be available on Peacock, NBCOlympics.com, NBC.com, and the NBC/NBC Sports app, with TV coverage on CNBC on July 20 (live) and July 21 (tape-delayed).

Login to leave a comment

3-time champion Molly Huddle is ready for 2023 NYC Half

The United Airlines NYC Half came into Molly Huddle‘s life in 2014 and it was one of the key turning points in the now 38 year-old’s storied career. Never a fan of cross country or indoor track, the 28-time national champion liked to de-camp from her Providence, R.I., home in the winter to put in her pre-season base miles in the warmth of Arizona. The NYC Half, with its mid-March date, was the perfect race to close-out her winter training block. Her long-time coach Ray Treacy, whom Huddle affectionately calls “The Guru,” gave his blessing and she signed-up for the 2014 race. It would be her first-ever half-marathon.

With the temperature right at the freezing mark, Huddle ran the entire race with the leaders. She went through the first 10-K in 33:01, and the second in a much faster 32:21 as the pace heated up. Although too far behind eventual winner Sally Kipyego (1:08:31), she finished a close third to eventual 2014 Boston Marathon champion Buzunesh Deba, 1:08:59 to 1:09:04.

“It was good,” a shivering Huddle told Race Results Weekly’s Chris Lotsbom that day. “I think I stuck my nose in it in the beginning and the distance got to me a little in the end, but it was definitely a fun experience. I definitely want to do another one.”

The rest, shall we say, is history.

For the next three years Huddle would repeat the same winter program, training in Arizona then coming to New York for the NYC Half before starting her track season*. She won in 2015, 2016 and 2017, and in the 2016 race she set the still-standing USATF record for an all-women’s race: 1:07:41. During her reign at the top, she beat top athletes like Sally Kipyego, Caroline Rotich, Des Linden, Aliphine Tuliamuk, Buzunesh Deba, Emily Sisson, Edna Kiplagat, Diane Nukuri, and Amy Cragg. She also lowered her 10,000m personal best from 31:28.66 to an American record 30:13.17, a mark which would stand for more than six years until Alicia Monson broke it just 11 days ago at The Ten in San Juan Capistrano, Calif. She also collected $65,500 in prize money from the event which is organized by New York Road Runners.

Huddle returns to the NYC Half for the first time in six years on Sunday, but she’s no longer focused on winning. The race comes about 11 months after she, and husband Kurt Benninger, had their first child, daughter Josephine Valerie Benninger, whom Huddle calls “JoJo.” Speaking to Race Results Weekly at a press event yesterday in Times Square, she reflected on her history with the race.

“The last time I did the Half was 2017, I think, so a long time,” said Huddle, wearing a warm hat and jacket on a cold, late-winter day. “Great to be back. Great to be running again seriously after having the baby in April. So, this will be a good test.”

Huddle has been slowly building her fitness since giving birth to Josephine. She first returned to racing last August at the low-key Bobby Doyle Summer Classic 5 Mile in Narragansett, R.I., –very close to her home– clocking 29:17. Since then she has run in a series of local races in New England –a pair of 10-K’s, a 5-K cross country, and a half-marathon– to regain her racing chops.

Then, in January of this year, she ran the super-competitive Aramco Houston Half-Marathon and clocked a very good 1:10:01, a mark which qualified her for the 2024 USA Olympic Team Trials Marathon. She went back to training, and the NYC Half should give her a good reading on her progress.

“I’m really happy to fit it back in the schedule,” said Huddle, who is still breastfeeding and will be pumping while she is in New York (Kurt is with Josephine at home in Providence). “I feel like I’m having more baseline workouts now, less of a building phase and more back to normal. I’ve had a few little injury problems last month, but I’m coming around.”

A well-traveled athlete, Huddle is sticking close to home for her races now. New York is a three and one-half hour drive (or train ride) from Providence.

“I love racing within a drive distance of home now because of the baby, and this is an easier race for me to get to,” Huddle said. “So that’s good.”

Sunday’s race has yet another purpose for Huddle. It will kick-off her training for her next marathon, a distance that she hasn’t taken on since the 2020 Olympic Trials in Atlanta when she was forced to drop out with an injury. Although she wasn’t at liberty to reveal which race it will be, she said that the timing of the NYC Half was perfect, just like it always was.

“So, I’m really focusing more on the roads now; it fits in really well with that plan now,” Huddle said. She continued: “This is going to kick off a marathon build-up for me, so this will be a really good race to fit into my marathon block as we go forward the next two months.”

by David Monti

Login to leave a comment

United Airlines NYC Half-Marathon

The United Airlines NYC Half takes runners from around the city and the globe on a 13.1-mile tour of NYC. Led by a talent-packed roster of American and international elites, runners will stop traffic in the Big Apple this March! Runners will begin their journey on Prospect Park’s Center Drive before taking the race onto Brooklyn’s streets. For the third...

more...You Might Be Slower Soon After Getting a COVID Booster

New research finds a temporary decrease in a key aspect of fitness.

Everyone has that friend who got their COVID-19 vaccine and bounced back the next day, with little more than a sore arm. We’ve also heard (or told) stories of being in bed for multiple days after the first, second, third, and fourth shot.

While no one enjoys feeling unwell, runners have an added concern: How will a shot affect my upcoming training and racing?

A recent study offers some quantification to anecdotal evidence runners have been sharing for the past year and a half, where the new research found a small decline in aerobic capacity post-booster. Here’s how to incorporate that finding into your training plans.

Why Runners Care About VO2 Max

VO2max is often treated as the gold standard measurement of cardiovascular fitness. It represents the maximum amount of oxygen your body can use during exercise. This matters for runners because, all else equal, the more oxygen you can use, the harder you can work.

Given the significance of VO2 max to athletes, researchers in Belgium set out to test whether the COVID-19 booster affected it. They recruited 42 recreational endurance athletes (runners, cyclists, and swimmers) who were scheduled to receive their COVID booster—i.e., the third shot in the two-series Pfizer vaccine. Just before they got their shot, the athletes took a VO2 max test. This involved riding a stationary bike while wearing a device that measured oxygen consumption. As resistance on the bike went up, their oxygen consumption also went up until it eventually plateaued—indicating VO2max.

One week after receiving their booster, the athletes repeated the test. Compared to their performance pre-booster, their VO2max showed, on average, a 2.7 percent decrease.

Given that a decline in VO2 max reflects a decline in cardiovascular fitness, this finding is worth factoring into your training and racing plans. However, it’s worth noting that a 2.7 percent decrease in VO2 max does not necessarily mean a 2.7 percent decrease in speed. Here’s an example using Jack Daniels’s VDOT values (which are a proxy for VO2 max).

Let’s say a runner with a VDOT of 38 gets her COVID booster. This lowers her VO2 max (VDOT) by 2.7 percent, giving her a reduced VDOT value of 36.97. According to Daniels’s calculations, all else being equal, her previous 5K time of 25:12 would slow to about 25:45, or by 33 seconds—which is only 2.2 percent slower. If she’s fitter and has a half marathon time of 1:44:20 and a VDOT of 43? One week after the booster, her VDOT would be just below 42, and her half marathon time would increase from 1:44:20 to around 1:46:30, or by 2.1 percent.

VO2 Max Isn’t Everything

Admittedly, these calculations assume “all else being equal,” which is virtually impossible. Many other factors contribute to running performance, including running economy (how much oxygen you need to run a given pace), stride mechanics, and even perceived effort. Hielko Miljoen, a sports cardiologist at University of Antwerp and lead author on the paper, pointed out that in that respect, this study is only the beginning of an answer to how the booster affects performance.

“The next step in this investigation should be to do an endurance test, because VO2max is just one part of exercise capacity and athlete performance,” he says.

Additionally, the researchers only tested VO2 max one week out from the booster shot. While it’s unknown what effects may exist further out from the shot—the researchers did not retest the athletes at later intervals—it seems unlikely that the decline is permanent. “This study is by no means an answer,” says Miljoen. “It is trying to reassure people that the effects are not huge, probably not lasting.”

Weigh the Risks

Every medical decision is a personal one, and the reality is that getting the COVID-19 vaccine, including the booster, doesn’t come with a non-zero amount of risk.

“The entire field of medicine comes with statistics,” says Miljoen. “The benefit and harm of a certain medical procedure or intervention are only known on a population basis, so individuals must make up their own mind based on the data out there.”

While life-threatening risks of the vaccine are low, getting it or the booster may interrupt your training for a few days. A recent study of more than 1,000 elite Polish athletes found that the athletes lost an average of two and a half training days around getting the COVID vaccine. However, the same study found that athletes lost an average of eight training days due to COVID-19 infection. Given these and other research data, the authors concluded in favor of vaccination for athletes, writing that “the benefit–loss ratio strongly favors vaccination.”

Time Your Shot Strategically

While it doesn’t feel great to miss any amount of training, one advantage of vaccination and booster shots is that they can be timed to have minimal impact on a racing season—whereas COVID infection can’t.

Ben Rosario, executive director of Hoka NAZ Elite, recalls two of his athletes contracting what he believes was COVID in January 2020.

“I think it really affected them in the 2020 Olympic Trials marathon, because it was a real detriment to their training at that time,” he says. “They missed a really important 10 or so days of training.”

With the initial vaccines, he observed that athletes would feel unwell for seven to 10 days; consequently, they tried not to schedule their vaccination in the week or two leading up to a race. The results of the Belgian study suggest that similar scheduling may be warranted for the booster. While you may only feel the effects of the booster for a day or two, its less discernable effects—like suppressed VO2 max—can still affect your race if you schedule it too close to the shot.

Go Light Around Your Booster

Amy Yoder Begley, coach of the Atlanta Track Club, says that what her team found worked best was to ease off training for the few days surrounding their booster. Typically, the athletes would do a light day of training on the day of the booster and then go home, hydrate, and focus on moving their arm throughout the rest of the day. They’d take the next day off to let their body recover and then, depending how they felt, they’d slowly ease back into training.

“I just kept telling people: literally you’re talking two to five days to let the body do its thing to give you more protection down the road, if possible,” says Begley.

Rosario has a similar message: “My advice to all runners would be to be patient. What’s the harm in missing some training if you’re going to come back super healthy?”

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

After Much Anticipation, Orlando Announced as Host of the Olympic Marathon Trials

The race will take place on February 3, 2024.

USA Track & Field (USATF) has named a host city for the 2024 Olympic Marathon Trials, and it’s Orlando, Florida.

The Trials will take place on February 3, 2024, giving the local organizing committee on the ground only 15 months to prepare for the high-profile event.

The top three finishers in the men’s and women’s races will represent Team USA at the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris (provided they have met the ever-evolving standards set by World Athletics, the sport’s worldwide governing body, to run at the Games).

USATF was slow in naming a host city for the event. By contrast, when the Atlanta Track Club hosted the 2020 Olympic Trials, those organizers had 22 months to put together a race for about 700 men and women.

The fields for the race in Orlando will likely be smaller, however, because the qualifying standards to get into the Trials are tougher than they were to get into the 2020 race. In December 2021, USATF announced that women had to run a marathon faster than 2:37 in order to qualify. (For the 2020 Trials, that time was 2:45.) Or, they need to run a half marathon faster than 1:12.

Following Sunday’s NYC Marathon, only 60 women have run a marathon qualifying time. The window for half marathon qualifying opens on January 1, 2023. Men wanting to qualify for the 2024 Trials have to run 2:18 or faster (last time, the standard was 2:19) or 1:03 in the half marathon. As of mid-October, which was the last time USATF updated its list, 68 men had qualified for the Trials.

The California International Marathon, to be run this year on December 4, typically yields several Trials qualifiers.

Orlando is the first Florida city to be awarded the event.

The 2020 Olympic Marathon Trials were one of the last elite races held before the COVID pandemic shut down the world for more than a year and postponed the Olympics. At the 2021 Olympic marathon, held in Sapporo, Japan, American Molly Seidel won a bronze medal. The 2024 Olympic marathons in Paris will be held in August of that year.

Login to leave a comment

Capt. Kyle King wins one for the home team at the Marine Corps Marathon

Capt. Kyle King had been hoping to compete in the Marine Corps Marathon for years. With runners back on the course Sunday morning for the first time since 2019, the Marine stationed in Twentynine Palms, Calif., achieved his goal and then some, winning the event’s 47th edition in 2 hours 19 minutes 19 seconds.

“That was a little emotional coming to the finish line,” he said. “I’ve wanted to run this race for so long.”

King, a 33-year-old artillery officer, finished 3 minutes 27 seconds faster than runner-up Jonathan Mott of Lakeland, Fla. England’s Chelsea Baker was the first woman to finish the race, completing the course in 2:42:38. Cara Sherman of Clifton Park, N.Y., was second, 4:30 behind.

King, who grew up in Washington state, has run competitively since high school, including a stint at Eastern Washington University. After taking a hiatus when he joined the Marines, he gravitated back toward the sport when he was stationed in Denver in 2018. In 2019, he won the Eugene (Ore.) Marathon, allowing him to qualify for the 2020 Olympic trials, at which he finished 47th in 2:18:20.

King prepared intensely for each of those opportunities, but his top goal was always the Marine Corps Marathon.

“I’ve been wanting to do this marathon for a while — just the work schedule and racing schedule [made it difficult],” he said. “This is the first time it actually happened.”

Chilly temperatures accompanied the start of the race through Arlington and D.C., but conditions improved as the morning unfolded. King found the weather beneficial to an extent.

“It was super cold. Honestly, I prefer cold over hot,” he said. “I wouldn’t say it really affected me. I honestly thought it was about perfect conditions. Pretty much no wind, nice and chilly, didn’t have to worry about getting too dehydrated.”

The power of the crowd was prominent Sunday, along the course and at the finish line. With friends, family and service members lining the way, runners called the energy infectious. King said the cheers of his fellow Marines provided an extra boost during difficult stretches.

“It’s really special doing it with all the Marines out there,” he said. “It was awesome to run in front of them and bring in the win for the home team.”

The previous two marathons were conducted remotely amid the pandemic, with participants running independently and submitting their times online. The virtual marathon setup failed to capture the camaraderie of the event, competitors said.

Gen. David H. Berger, the 38th commandant of the Marine Corps, was glad to be back in person, too. In 2019, he became the first commandant to run this marathon, finishing in 5:29:38. Running the race in person again this year, he emphasized his desire to compete alongside the community.

“This is not about the Marine Corps. It’s about the people. And although we organize it [and] it has our name, it’s really about the people,” said Berger, who finished in 5:46:36. “The emphasis should be [on] the people — the active duty, the reserved people, the civilians. This is definitely the people’s marathon.”

“Every individual who’s running has their own story, and every story has that mission that got them there to the start line,” Nealis said. “When they come across the finish [line] … they earned the right to be part of the few, the proud, the Marine Corps Marathon finishers.”

by Michael Charles

Login to leave a comment

Marine Corps Marathon

Recognized for impeccable organization on a scenic course managed by the US Marines in Arlington, VA and the nation's capital, the Marine Corps Marathon is one of the largest marathons in the US and the world. Known as 'the best marathon for beginners,' the MCM is largest marathon in the world that doesn't offer prize money, earning its nickname, “The...

more...Can Mantz and Sisson set American records on Sunday at the Chicago Marathon

Conner Mantz and Emily Sisson are looking to set American records at the Chicago marathon on Sunday. Mantz, who comes to his marathon debut with impressive XC and track credentials, has his eye on Leonard Korir’s American debut mark of 2:07:56, which was set in Amsterdam in 2019.

“All of my races and workouts have led up to this distance,” Mantz said. “I get excited thinking about it but I need to remember my first marathon and there are some unknowns.”

Sisson, who set the American women’s record in the half-marathon with a 1:07:11 at the USATF Half-marathon Championships in Indianapolis in May, only has one completed marathon under her belt – a 2:23:08 at London in 2019 (she dropped out of the 2020 Olympic Trials)– but has her eyes on the women’s American record of 2:19:12, which was set this past January by Keira D’Amato in Houston.

“My first marathon experience was really positive, and I really enjoyed it,” Sisson said. “After my first marathon in London I was drawn back to it and really want to see what I can do.

“My main goal is to try to break 2:20. If I’m feeling good and the record is in striking range I’ll take a stab at it. I had a really good buildup without any big setbacks. The weather for the weekend looks great, and I don’t know how many times I’ll have that, so I might as well take a swing at it.”

The temperatures will be in the low-50s at the start of the race and most likely cross the 60-degree mark by the time the men’s and women’s winners will cross the finish line. While it may be a touch humid at the beginning of the race, that isn’t expected to have that much of an effect.

Even more promising is the wind. Chicago is unique among the World Marathon Majors in that much of the course up to the halfway point is run in the core of the downtown area among the tall buildings, which can whip the wind around. It also leaves the potential for the competitors to be dealing with a headwind as they make the final push up Michigan Avenue to the finish.

This year, the predicted 7-12 mph winds will be from the southeast, which could be a bit of an assistance over the final few miles.

The race is set to start at 7:30 AM Sunday, and will be shown locally on NBC and streamed on Peacock.

by Let’s Run

Login to leave a comment

Bank of America Chicago

Running the Bank of America Chicago Marathon is the pinnacle of achievement for elite athletes and everyday runners alike. On race day, runners from all 50 states and more than 100 countries will set out to accomplish a personal dream by reaching the finish line in Grant Park. The Bank of America Chicago Marathon is known for its flat and...

more...How Keira D’Amato became America’s best ever woman marathoner

Keira D'Amato is currently at the top of the American women's distance running scene. She holds multiple American records — in the 10-mile and the marathon, the latter of which had stood for nearly 16 years before D'Amato smashed it in January — and has racked up win after win this year at everything from 10Ks to 7 milers. But just two years earlier, the real estate agent and mom of two was mostly unknown, quietly putting in miles near her home in Midlothian, Virginia.

That's not to say D'Amato's success came out of nowhere — before starting her real estate career and her family she was a standout runner, a four-time All-American, at American University in Washington, D.C.

"My life then was to eat, sleep, breathe and run. That was all I knew and all I wanted to do," D'Amato, 37, tells PEOPLE. "It was my whole world." She planned to pursue professional running after graduation, but her dreams were quickly derailed by a series of injuries. When her insurance denied a needed ankle surgery, D'Amato was "kind of forced out" of the sport.

"It was a weird breakup. It really felt like running was breaking up with me," she says. "It was heartbreaking. All of sudden I was Keira the runner who doesn't run."

D'Amato ended up meeting her husband Anthony, getting her real estate license and having two kids, Thomas, now 7, and Quin, 5. Her running at that time was very casual — she picked it up again to get back in shape after the two pregnancies and for a dose of sanity while at home with young kids and a military husband, who at times was deployed for more than a year.

"That was a really, really hard time for me," she says. "Just two kids under 2 and being at home alone. I felt lonely and I felt a little trapped." D'Amato would hire a babysitter for an hour, just so she could get out and run.

"I needed something that was mine and that I controlled and something that was just slow and peaceful. Then as soon as I walked back in the door, I was feeling really proud that I'd accomplished something for me that I could go right back to being a mom," she says. "It just helped me cope during that time."

D'Amato also started jumping into a races — a local 5K, or a long weekend in Nashville with a friend for a half marathon. "It was totally for fun and it taught me how to love running without needing to be fast or have goals."

Her real return to running started as a prank — she kindly gifted Anthony with an entry to the 2017 Shamrock Marathon for Christmas one year, and feeling bad about it, decided to sign herself up too.

Thinking she'd run it in around 3 hours and 30 minutes (an impressive time for the average runner, but nothing outstanding), D'Amato ended up easily covering the 26.2 miles in 3:14:54. Eight months later, she decided to train for the Richmond Marathon, and shockingly finished in 2:47:00 — two minutes short of the Olympic Trials qualifying time.

"That's when the fire started because I was like, 'Oh, two minutes in a marathon. That's four seconds per mile. I can do that.' "

With the help of her old college coach, Scott Raczko, D'Amato qualified, and then came in 15th at the 2020 Olympic Trials, ahead of around 450 other women, including several professional runners. A few weeks later, the COVID-19 pandemic shut down the world, and races.

But for D'Amato, "running wasn't canceled," she says. "I think a lot of other pros thought, 'Well, there are no races. This is a really natural time to take a break.' For me, I'm like, 'Hey, they're taking a break. I'm putting the pedal to the metal and I'm going to really catch up.' I trained really, really hard during COVID."

She started making some headlines after running a speedy 5K on her local track, and then even more in Nov. 2020 after she organized a 10-mile race where she broke the American women's record. Four months later, D'Amato signed her first-ever professional running deal with Nike.

"That was really cool," she says. "I think for Nike to bet on someone that wasn't a right-out-of-college national champion, it was some mom in a smaller town — for them to see what I saw in myself is really powerful."

D'Amato had already been relying on Nike for her running shoes, and appreciated that unlike other brands that require their runners to join teams in Arizona or Oregon, she could continue training at home in the Richmond area.

"They support people like me that are trying to be the best in the world, but they're also really supportive on an individual level of everyone finding their own best," she says. "They really build up the sport from youth programs to professional athletes and everything in between. I feel like they've created shoes for all runners to be their own best."

D'Amato ticked off more goals from there, coming in 4th at the Chicago Marathon — her first World Marathon Major as a pro — and winning the 2021 U.S. Women's Half Marathon title.

Then, in Jan. 2022, she went after the American marathon record, a record that had stood since 2006, despite years of the top female marathoners in the country trying to bring it down. It was D'Amato, on a windy day in Houston, who was finally able to do it in a time of 2:19:12.

"On the starting line that day, I was thinking I'm either going to get the record or I'm not. If I get it, that would be wild, but if I don't, I'm going to be right where I am right now and that's cool too. I'm happy," she says.

D'Amato thinks that the way she found her way to professional running — going from a standout college career to her "elaborate halftime show" to getting back in the game — helped her to her record-breaking runs.

And D'Amato isn't done now that she has the American record. She got to knock off another goal in June when she got a last-minute call-up to compete at the World Track and Field Championships and donned a USA uniform for the first time.

Despite having just 17 days to train for a marathon (D'Amato had been racing speedier 10Ks when she got the ask to join the team), she went out fast and finished eighth in the world. In September, she'll toe the line at the Berlin Marathon — known for its flat and speedy course — and has her mind set on lowering the American record again.

"I'm in this really beautiful spot where I feel like I have nothing to lose, but just everything to gain," she says. "I'm putting everything out there, my heart, my soul, my running shoes and just going for it with every opportunity."

by Julie Mazziotta (People Magazine)

Login to leave a comment

Aliphine Tuliamuk will make marathon return at 2022 New York City Marathon

For Aliphine Tuliamuk, the decision to run in the 2022 TCS New York City Marathon was a no-brainer. The 33-year-old ran the event back in 2019, finishing 12th, and she never thought it would take three years before a return trip to Staten Island’s start line.

“It was not even, you know, a matter of if – it was just when can I get to New York? So, it was not even a decision. Easy,” explains the Kenyan-born American long-distance runner, who made a name for herself in February 2020 when she won the U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials.

But the Covid-19 pandemic hit immediately after her Trials win, postponing the Olympics and canceling that year’s edition of the NYC Marathon. During the forced hiatus, she started a family with partner – now husband – Tim Gannon, welcoming daughter Zoe in January 2021. Injury struck later that year while she was training for the postponed Tokyo Olympics, and Tuliamuk withdrew about 20k into her Olympic debut with severe hip pain and hasn’t competed in a marathon since.

Her return to marathon competition has Tuliamuk fired up, both literally and figuratively.

“I’m faster than I’ve ever been before,” she recently told On Her Turf. “And it kind of makes me excited and nervous to see what (the) New York City Marathon brings, because this is going to be the first time I am actually going to complete a marathon since the 2020 Olympic Trials. That’s like, almost three years. So it’s going to be super exciting.”

Tuliamuk won’t have to wait until November, however, to enjoy a visit to the Big Apple. She’ll lace up her sneakers this Saturday, Aug. 13, as a “running buddy” to the young women who participate in the New York Road Runners (NYRR) Run for the Future program. The free, seven-week program introduces 11th- and 12-grade female high schoolers to the sport of running and culminates with this weekend’s NYRR Percy Sutton Harlem 5K.

“Running transformed my life into the life that I have today,” she explains. “I mean, without running I wouldn’t be where I am today. And to know that these girls did not have running experience before, they knew nothing about running, and then they were able to get into running through New York Road Runner feeder program, and now they will be graduating, and I get to run with them? I think that’s just incredible.”

The opportunity comes with an extra layer of “grateful” after Tuliamuk’s most recent injury. She sustained a concussion in February after slipping while training in icy, snowy conditions. She also suffered headaches and temporary memory loss, both of which subsided after about a week but left a lasting impression.

“It just gives you a perspective that like your life could literally, in a second, just turn and be something else,” she says. “This is just me being dramatic, but I could have forgotten completely. And the life that I had would have been something like a past life. I think after that, I was like, ‘Okay, I’m going to try to live life to the fullest.’ I’m going try to be present as much as I can, because you just never know.”

by Lisa Antonucci

Login to leave a comment

TCS New York City Marathon

The first New York City Marathon, organized in 1970 by Fred Lebow and Vince Chiappetta, was held entirely in Central Park. Of 127 entrants, only 55 men finished; the sole female entrant dropped out due to illness. Winners were given inexpensive wristwatches and recycled baseball and bowling trophies. The entry fee was $1 and the total event budget...

more...2022 Carlsbad 5000 Announces Its Elite Field

eigning champion and 17-time NCAA All-American Edward Cheserek headlines men’s race; Olympians Kim Conley and Dom Scott lead women’s elite fields

36-Year Southern California Running Tradition Returns with over 6,000 runners on Sunday, May 22

One by one, America’s most famous road races have returned after being waylaid by COVID. The Boston Marathon, Peachtree Road Race, New York City Marathon.

Familiar images unfolded. Runners excitedly talked to friends and strangers in corrals. Spectators delivering high-fives. Medals draped around necks.

Bolder Boulder, Bay to Breakers, the Los Angeles Marathon.

Come Sunday, the last of the United States’ iconic road races returns after a three-year pandemic hiatus when the Carlsbad 5000 presented by National University celebrates its 36th running. Over 6,000 runners and joggers will enjoy the splash of the surf and clean salt air along the traffic-free Pacific Coast Highway 101, then sipping brews in the Pizza Port Beer Garden.

“I’m excited to return to the Carlsbad 5000,” said reigning champion Ed Cheserek of Kenya. “Last time in 2019 was a lot of fun and after everything our running community has been through since then, I’m really looking forward to being back at the beach in sunny Southern California.”

The Carlsbad 5000 is renowned as “The World’s Fastest 5K” and the moniker was earned.

Sixteen world records have been set on the seaside course, plus a slew of national records and age group bests. Olympic gold medalists Tirunesh Dibaba, Meseret Defar and Eliud Kipchoge have run Carlsbad.

So have U.S. Olympic medalists Deena Kastor and Meb Keflezighi. Keflezighi, the San Diego High product and only male runner in history to win the Boston and New York City marathons, plus an Olympic medal, is now co-owner of the race.

“The San Diego community is very proud of the fact that Carlsbad hosts the world’s most famous 5k race,” said San Diego Track Club coach Paul Greer, a former sub-4-minute miler. “We’re proud of the race. And local runners are endeared by the fact that Meb is involved in the event because he’s one of our own.”

Many people deserve credit for the Carlsbad 5000’s success. Chief among them are Tim Murphy, the race’s creator, Steve Scott, the former American mile record holder who designed the course, and the late Mike Long, the beloved man who built relationships with African athletes and recruited them.

When the race was first held in 1986, the 10K and marathon were road racing’s popular distances. The 5K was considered a casual fun run.

“That’s how innovative Tim was,” said Scott. “He was going to start something when there wasn’t anything there.”

Scott not only designed the course. He won the first three races.

Another plus for The ’Bad: the race fell perfectly on the calendar, with the elite runners being in peak fitness after running the World Cross Country Championships.

“The world records were produced by the quality of the fields and the expectations of running fast,” said road racing historian and announcer Toni Reavis.

It may have been three years since the Carlsbad 5000 was held live (there was a virtual race in 2020), but all the charms will be back Sunday. The custom beer garden IPAs, the ocean views, the left-hand, downhill turn onto Carlsbad Village Drive, and the sprint to the finish.

The race’s official charity is the Lucky Duck Foundation, a local non-profit dedicated to fighting homelessness in San Diego County.

“Homelessness is San Diego’s number one social issue right now, and I couldn’t be prouder to partner with Lucky Duck Foundation as an official charity of the Carlsbad 5000,” said Keflezighi.

As in the past, the Carlsbad 5000 will feature a series of age-group races, starting with the Men’s Masters at 6:55 am, the Women’s Masters at 8:00 am, Open Men at 9:15 am, Open Women at 10:08 am, Junior Carlsbad Kids Mile at 11:20 am, Junior Carlsbad Kids Half-Mile at 12:13 pm, Elite Men at 1:20 pm and Elite Women at 1:23 pm.

The morning-long races create a cheering audience for the pros.

“That’s the other thing that made the elites run fast,” said Reavis. “The crowds.”

So after a three-year pause, the Carlsbad 5000 is back. For why the race continues to maintain its iconic appeal, Reavis said, “It’s those ocean breezes, the lapping waves, the laid-back lifestyle. It is perfect for this little Southern California town which gets transformed into a race course.”

For a complete race day schedule and more, visit Carsbad5000.com.

— Elite Rosters Follow —

Elite Men

Bib Number , Name, Country, Career Highlight, Birthday

1. Edward Cheserek, KENYA, Defending Champion . 17x NCAA Champion, 02/02/1994

2. Kasey Knevelbaad, USA – Flagstaff, 13:24.98 5000M(i) Personal Best, 09/02/1996

3. Reid Buchanan, USA – Mammoth, 2019 Pan American Games 10,000m Silver, 02/03/1993

4. Jose Santana Marin, MEXICO, 2019 Pan American Marathon Silver Medal, 09/03/1989

5. Eben Mosip, KENYA, Road 5k Debut, 12/31/2002

6. James Hunt, GREAT BRITAIN, 4-time Welsh Champion, 04/28/1996

7. Dennis Kipkosgei, Kenya, 2021 Philadelphia Broad Street 10 Miler Champion, 12/20/1994

8. Sean Robertson, USA, Butler University Athlete, 09/16/2001

9. Tate Schienbein, USA – Portland, 2013 U.S. Junior Steeplechase Champion, 04/04/1994

10. Hosava Kretzmann, USA – Flagstaff, AZ, 14:15 5000m PB, 09/02/1994

11. Dylan Belles, USA – Flagstaff, AZ, 2X Olympic Trials Qualifier, 05/16/1993

12. Dylan Marx, USA, San Diego’s Fastest Marathoner, 01/14/1992

13. Steven Martinez, USA – Chula Vista, 2x U.S. Olympic Trials Qualifier, 09/15/1994

14. Spencer Johnson, USA – San Diego, 14:39.09 (2022 Oxy Distance Carnival), 03/20/1995

15. August Pappas, USA – San Diego, 14:05 PB, Big Ten Indoor Track Champs, 04/10/1993

16. Dillon Breen, USA – San Diego, 14:43 Virtual Carlsbad 2020, 09/01/1992

17. Dante Capone, USA – San Diego, Phd Student at Scripps Institute, 11/07/1996

18. Jack Bruce, AUSTRALIA, 13:28.57 5000m Best on Track, 08/31/1994

Elite Women

Bib Number , Name, Country, Career, Highlight, Birthday

20. Kim Conley, USA, One of America’s best 5000m runners, 03/14/1986

21. Dominique Scott, SOUTH AFRICA, Two-time Olympian, 05/24/1992

22. Grace Barnett, USA – Mammoth, Silver at 2021 USATF 5k Championships, 05/29/1995

23. Carina Viljoen SOUTH AFRICA, 5k Road Racing Debut, 04/15/1997

24. Ayla Granados, USA – Castro Valley, 15:53 Personal best, 09/18/1991

25. Biruktayit Degefa, ETHIOPIA, 2022 Crescent City 10k Champion, 09/09/1990

26. Andrea Ramirez Limon, MEXICO, 2021 National 10000m Champion, 11/05/1992

27. Claire Green, USA – San Francisco, NCAA All-American, 05/12/1996

28. Caren Maiyo, KENYA, 5k Road Debut. 7th At 2022 Houston Half Marathon, 04/17/1997

29. Nina Zarina, RUSSIA, California resident, 3rd at the 2021 LA Marathon, 03/17/1987

30. Emily Gallin, USA – Malibu, Finished 4th 2022 LA Marathon, 10/30/1984

31. Lauren Floris, – USA – Oak Park, 2020 U.S. Olympic Trials Qualifier, 07/07/1990

32. Sara Mostatabi, USA – Los Angeles, 09/27/1993

33. Ashley Maton, – USA – Toledo, 16.37 PR at U.S. Road 5k Championships, 11/20/1993

34. Judy Cherotich. KENYA, 16:50 PR

35. Lindsey Sickler, USA – Reno, 16:59 PR, 09/05/1997

36. Megan Cunningham, USA – Flagstaff, 15:53 Track Best 5000M, 03/01/1995

37. Jeannette Mathieu, USA – San Francisco, 2020 Olympic Trials Qualifier, 04/19/1990

38. Bre Guzman, USA – San Diego, 17:37 5k/ 36:00 Road 10k PR, 10/30/1992

39. Aubrey Martin, USA – San Diego, 17:33 5k /1:19 Half Personal Best, 10/10/1997

40. Chloe Gustafson, USA – San Diego, Division II – NCAA All-American, 11/10/1992

41. Sammi Groce, USA – San Diego, 2021 Rock ‘n’ Roll Marathon Winner, 04/29/1994

42. Kristi Gayagoy, USA – San Diego, 17:06 PR

43. Annie Roberts, USA – San Diego, 16:58 5k, 07/10/1996

44. Alexa Yatauro, USA – San Diego, 17:40 5k, 10/18/1995

45. Jessica Watychowicz, USA – Colorado Springs, 15:47.51 5000m Track PB, 02/27/1991

About the Carlsbad 5000

The Carlsbad 5000 annually attracts amateur, competitive and professional runners from around the world. The 36th running of the iconic race will take place on the weekend of May 21-22, 2021. The inaugural 1986 event helped establish the 5K as a standard road running distance, and today, the 5K is the most popular distance in the United States. Throughout its history, the Carlsbad 5000 has seen 16 World records and eight U.S. records, as well as numerous national and age group marks. Race day begins at 7:00 am with the Masters Men (40 years old and over), the first of seven races to take place on Sunday. The “Party by the Sea” gets started as soon as the first runners cross the finish line with participants 21 and older celebrating in the Pizza Port beer garden with two complimentary craft brews and runners of all ages rocking out to live music on the streets of the Carlsbad Village. Further information about the Carlsbad 5000 can be found online at Carlsbad5000.com and on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

by Running USA

Login to leave a comment

Carlsbad 5000

The Carlsbad 5000 features a fast and fun seaside course where 16 world records have been set. Both rookie runners and serious speedsters alike enjoy running or walking in Carlsbad. Weekend festivities kick off Saturday morning with the beloved Junior Carlsbad, a kids-only event in the heart of Carlsbad Village featuring fun runs, toddler trots, and diaper dashes! On Sunday,...

more...Molly Seidel despite being a favorite for the 2022 Boston Marathon, still struggles with confidence

The 27-year-old battled with an eating disorder to qualify for the USA Olympic team in her first ever marathon. Despite winning bronze at Tokyo 2020 and being a favorite for the 2022 Boston Marathon, she still struggles with confidence.

Molly Seidel is a rare kind of marathon talent.

The Wisconsin native first made athletics headlines when she qualified in second place for the U.S. Olympic team for Tokyo 2020, in her first ever marathon.

Despite this, many onlookers thought that her inexperience would show at the Olympic race in Sapporo. And how wrong they turned out to be.

In what was just her third career marathon, she finished on the podium with an Olympic bronze medal around her neck. The only runners to beat her were a triple world half marathon record holder in Peres Jepchirchir, and marathon world record holder Brigid Kosgei.

Using that momentum, Seidel finished fourth at the New York City Marathon in November 2021. Her time of 2:24:42 made her the fastest American woman ever.

On April 18, 2022, she goes to the 2022 Boston Marathon as one of the favorites, seeking the host nation's first win since Desiree Linden in 2018.

But despite her recent successes the American star still struggles with 'imposter syndrome'.

"I struggle with confidence and I struggle with wondering whether or not I belong at this level, whether I belong as a competitor on the world stage," Seidel told CNN.

The making of a front runner

Growing up in Wisconsin, Seidel was always a front runner in school sport. She broke course records and won several state track titles.

The first time her school's cross-country coach Mike Dolan first saw her attack an uphill run, he knew she was special.

“She would be a minute ahead of all the guys and all the girls," Dolan told Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

"I knew at that time she would be a heck of a runner."

Seidel proved her coach right as she went on to win an NCAA cross country title in 2015, two NCAA indoors (3,000m & 5000m) and an outdoor 10,000m title to become the most decorated distance runner in state history.

Some onlookers even thought she could be a potential U.S. Track Olympic Team athlete for Rio 2016.

Mental health struggles

From the outside, Seidel seemed to be in the best shape of her life, but underneath she was experiencing a deep inner turmoil.

She first went public on her struggles with depression, OCD, crippling anxiety and bulimia in a podcast ran by her close friend Julia Hanlon called "Running On Om", just two months before the 2020 Olympic Trials.

“People who are close to me knew what I was going through during my time at Notre Dame (University), from 2012 to 2016. They knew my OCD had manifested itself into disordered eating,” she revealed in a follow-up interview with ESPN.

“When I was in the NCAA, it was obvious I was battling an eating disorder. It was so obvious that people would write on track and field message boards that I looked sick." - Molly Seidel to ESPN.

“They knew I struggled to eat anything I deemed unhealthy They knew I thought I had to be super lean and super fit all the time, never even allowing myself to eat a bowl of mac and cheese or go out to eat with friends without worrying about what I would order. I've never tried to hide what I went through with my family and friends.”

In 2016 she went into a treatment program for her eating disorder, which she’s still dealing with alongside the anxiety and depression.

When Seidel returned to training, she decided to stop running 5k and 10k and stepped up to the marathon.

“I always kind of dreamed of doing the marathon," Seidel told CNN.

"I think there's just this kind of like glamor and mystery around it, and especially for a younger runner who enjoys doing the distance events in high school, that's kind of the ultimate goal. Everybody wants to do the marathon."

From first marathon to Olympic medal

Her debut 42km race at the USA Trials in Atlanta landed her a place on her nation's Olympic team with race winner Aliphine Tuliamuk and third placed Sally Kipyego.

"I struggled with this kind of imposter syndrome after the trials, specifically as probably the person no one expected to make the team and the person that got probably the most criticism like: Hey, why is this girl on the team?" she continued.

"I think I really struggled with that, and I struggled going into the Games and feeling like I belonged there and trying to prove that I wasn't a mistake on that team."- Molly Seidel to CNN.

Her second marathon effort was the daunting 2020 London Marathon, where she finished sixth .

Then, just 18 months after her first marathon Seidel, who is affectionately known as “Golly Molly” earned bronze and became the third American woman ever to medal in the Olympic marathon.

In November 2021, a broken Seidel returned for her fourth marathon in New York, where she placed fourth with a personal best time despite fracturing two ribs as she prepared for the event.

It was an absolute disaster of a build up,” she recalled.

"It was really hard, not only with the mental stress that we had going on after the Games of just feeling, frankly, no motivation. And just trying to find that drive to re-up for another hard race right after an enormous race that I'd been training effectively two years for.”

Those injuries are now behind the 27-year-old, who has been training in Flagstaff.

Though she dropped out of the New York Half in March due 'setbacks in training', Seidel heads back to Boston where she lived for four years with high hopes for something special.

“Boston was like the place that made me a pro-runner. It was the first place I moved after I finished college.It was the place that kind of like rebuilt me as a runner after going through a lot of challenges through college,” she said to CBS Boston.

“Just getting to do the race in the place that made me the runner that I am and with the people that helped me become the runner that I am, it’s just enormously meaningful to me. That what makes it a lot more special than any other race.”

by Evelyn Watta

Login to leave a comment

Boston Marathon

Among the nation’s oldest athletic clubs, the B.A.A. was established in 1887, and, in 1896, more than half of the U.S. Olympic Team at the first modern games was composed of B.A.A. club members. The Olympic Games provided the inspiration for the first Boston Marathon, which culminated the B.A.A. Games on April 19, 1897. John J. McDermott emerged from a...

more...Why training doesn’t stop after your run

Under Armour’s approach to training is different from its competitors. The company believes that performance doesn’t just come from training, it comes from a holistic approach to running which includes considering emotional, psychological, physiological and nutritional strategies. They call this approach 360 Performance – it means that running doesn’t stop when your watch does and highlights the ways in which training really is all-encompassing. This approach to running may seem daunting, but actually, it’s geared towards balance.

For Aisha Praught-Leer, a UA athlete and 1,500m Olympian, 360 Performance is how she lives her life. “Showing up on race day is such a small part of my existence. Everything else, the getting there, happens in the quiet moments.”

Georgia Ellenwood, Ashley Taylor, Patrick Casey and Aisha Praught-Leer are all professional UA athletes. However, when they talk about 360 performance, they talk about things beyond the nuts and bolts of training. To them, 360 means taking care of your entire being and improving yourself in every way.

Michael Watts, Under Armour’s Director of Global Athlete Performance, feels that 360 Performance is what sets UA apart. “Every minute and every hour matters in the life of an athlete, if they are not training or competing then they are in a perpetual state of recovery. How they optimize their recovery depends on their own circumstances and journey. We want athletes to become more knowledgeable about themselves and how best to optimize their performance based on their data. Why does it matter? Because the best athletes in the world sweat the details, they are on a constant journey to master their mind, body and craft. We just help guide them.”

Believe in yourself

Ellenwood, a Canadian heptathlete, saw a difference in her results when she began to believe in herself. She says 360 Performance means so much more than training – it means emotional, psychological and physiological harmony. Under Armour helped her find this. “I’m a real perfectionist,” Ellenwood says. “I used to be so worried about taking risks in practice, because I didn’t want to look dumb or to fail. But I think sometimes you need to hit a hurdle hard or you need to fall. Do the ugly stuff in training.” Ellenwood says she’s made way more progress after allowing herself to make mistakes and becoming process-oriented, as opposed to obsessing over results.

When it comes to practically preparing for her day, Ellenwood needs to get her body physically and mentally prepared. “Before I even leave the house I do pre-hab, so that means getting my feet ready, I warm up my legs with a heat pack, I have an hour of exercises before I even start practice.”

From there, Ellenwood will train for six to eight hours. In order to maintain that level of activity, she says she takes comfort in her routine and allows rest when needed. “Running is my full-time job and I love it, but sometimes it becomes a lot. If I need to stop for a moment if I’m becoming overwhelmed by the load, I let myself. I’ve learned that stepping away from the track for a minute, to regroup, is ok.”

Be patient

Taylor, a Canadian 800m runner, echoes this statement. She says that she, too, used to place a big emphasis on results, but she feels supported by an organization that sees her as more than a runner. “UA gives us a lot of sport-specific support. But they support us beyond that. They help remind me to love myself through the process and to be patient.” With her goals for 2020 entirely changed, patience has been key.

Casey might be the most patient of the four UA athletes. The American miler has been looking forward to the 2020 Olympic Trials for nearly eight years. After being sidelined due to injury in 2016, he had his sights firmly set on qualifying this July. However, like everyone else, Casey’s plans have changed. He said he’s coping quite well with the new training, and feels like he’ll be ready when the time comes to line up again. “I used to think of running as the two or three hours I’d actually be training everyday. Now I think of it as what I’m doing when I’m not running. How I’m recovering, how I’m preparing myself – because you can only do so much physically in a day.”

It’s a lifestyle

All of the athletes feel that thinking about training in this new way, as a lifestyle as opposed to one aspect of their day, has made them better runners. Aisha Praught-Leer, a 1,500m runner and Olympian, feels like she places more of an emphasis on overall happiness now, which has in turn, made her a better runner.

“Showing up on race day and running a fast time is just a miniscule part of my existence. That’s just the tip of the iceberg. Training is how I’m sleeping, how I’m eating and how I’m keeping myself happy as a person.” Praught-Leer says while she’s a social person at practice, she’s an introvert at heart. For her, she unwinds with a solo run or a self-care routine that she’s perfected. While painting her nails doesn’t seem like training, it helps her unwind. She feels like the better she’s feeling about her life overall, the faster she will run. “My job is high pressure, so it’s imperative to take care of the below-the-surface stuff, to be able to run fast times on race day.”

Praught-Leer has learned that taking care of the below-the-surface stuff needs to be a priority. “Like Under Armour encourages, I really take a holistic approach to my training. It’s not my couple hours a day when I’m training. It’s how I recover, it’s how I’m sleeping, how I’m eating, how I’m hydrating and how I’m keeping myself happy and sane and motivated.”

360 Performance isn’t just about running – it’s actually about everything else outside of training that allows you to enjoy your sport. For the athletes above, running is their job, and they still ensure they’re loving what they do. If running is your leisure activity, enjoyment is even more important. A happy runner is a fast runner, and that’s what Under Armour wants to see in those they support.

by Madeleine Kelly

Login to leave a comment

Olympic Medalists Will Headline 2022 Boston Marathon Women’s Field

Peres Jepchirchir of Kenya, the 2021 Olympic gold medalist in the marathon, and her countrywoman Joyciline Jepkosgei, who ran the fastest marathon of 2021, 2:17:43, when she won the London Marathon, headline the Boston Marathon elite women’s field for 2022.

American Molly Seidel, who won Olympic bronze last summer, will also line up in Hopkinton on April 18.

The race marks the 50th anniversary of the first official women’s field at the Boston Marathon. This year’s elite women entrants include Olympic and Paralympic medalists, World Major Marathon champions, and sub-2:20 marathoners.