Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Search Results for Ultra

Today's Running News

Rick Rayman, 77, completes his 400th marathon at TCS Toronto Waterfront Marathon

On Sunday at the TCS Toronto Waterfront Marathon, Rick Rayman, a professor of dentistry at the University of Toronto, marked his 400th marathon finish. Rayman is 77, and not only has he now completed 400 marathons, but he has participated in every single Toronto Waterfront Marathon in the race’s 34-year history.

As if that weren’t enough, Rayman has also run every single day for the past 44 years and 10 months–a daily run streak that’s topped by only one individual in Canada, according to runeveryday.com. (That’s Simon Laporte of Notre-Dame des Prairies, Que., whose streak is three years longer. Rayman is #20 on the international run streak list.) “I don’t know if the 19 runners ahead of me have run as many marathons as I have, but who cares?” he says, adding, “The older and slower I get, the more notoriety I get.”

On Dec. 10, he’ll celebrate 45 years of running without missing a single day. He runs for at least half an hour, though some days he runs for an hour or two. And he takes care to add that he never runs on a treadmill–though he has participated in 10 indoor marathons in the past, including six at York University, three at the University of Toronto’s Hart House and one the SkyDome (now the Rogers Center).

“It’s such a great marathon!” Rayman says of the Toronto race, even though he struggled with back pain in the second half, most of which he walked. “I can run 12 miles (or 20 km) without any pain,” he says. When asked if he’s ever considered switching to the half-marathon, he replies, “Never.”

“It’s a good question,” he concedes, “because my half marathon time is considerably better than my full. But I enjoy the challenge of the marathon.” Rayman was the only individual in the M75-79 age category.

Over the years, Rayman has seen a few changes at the Toronto Waterfront Marathon. The technology for tracking runners on the course, in particular, has evolved considerably since the early days, and he enjoys the recent changes to the course, which allow midpackers and back-of-the-packers like himself to see the elites running past in the other direction on Wellington Street and Eastern Ave. He credits race director Alan Brookes and his staff at Canada Running Series with putting on a world-class event.

Rayman admits he’s slowing down. “I’m not going to do another marathon this year,” he says, adding that next year, he has plans to run the Fort Lauderdale Marathon in February, Ontario’s Georgina Marathon in the spring, the Buffalo Marathon in May and the marathon at the Niagara Ultra in June. “I did 11 [marathons] this year; I might cut that in half next year. Maybe six or seven.”

Regardless, you can catch him running every day, rain or shine, from his home in North York. “I’ll keep doing it until I can’t,” he says.

(10/17/2023) ⚡AMP

by Anne Francis

TCS Toronto Waterfront Marathon

The Scotiabank Toronto Waterfront Marathon, Half-Marathon & 5k Run / Walk is organized by Canada Running Series Inc., organizers of the Canada Running Series, "A selection of Canada's best runs!" Canada Running Series annually organizes eight events in Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver that vary in distance from the 5k to the marathon. The Scotiabank Toronto Waterfront Marathon and Half-Marathon are...

more...Molly Seidel Stunned the World (and Herself) with Olympic Bronze in Tokyo. Then Life Went Sideways.

She stunned the world (and herself) with Olympic bronze in Tokyo. Then life went sideways. How America’s unexpected marathon phenom is getting her body—and brain—back on track.

On a clear December night in 2019, Molly Seidel was at a rooftop holiday party in Boston, wearing a black velvet dress, doing what a lot of 25-year-olds do: passing a joint between friends, wondering what she was doing with her life.

“You should run the Olympic Trials,” her sister, Izzy, said, as smoke swirled in the chilly air atop The Trackhouse, a retail shop and community hub on Newbury Street operated by the running brand Tracksmith. “That would be hilarious if you did that as your first marathon.”

Molly, an elite 10K racer who’d spent much of 2019 injured, looked out at the city lights, and laughed. Why the hell not? She’d just qualified for the trials, winning the San Antonio Half with a time of 1:10:27. (“The shock of the century,” as she’d put it.) True, 13.1 miles wasn’t 26.2—but running a marathon was something to do. If only because she never had before.

A four-time NCAA track and cross-country champion at The University of Notre Dame in Indiana, Molly had moved to Boston in 2017, where she’d worked three jobs to supplement her fourth: running for Saucony’s Freedom Track Club. The $34,000 a year that Saucony paid her (pre-tax, sans medical) didn’t go far in one of America’s most expensive cities. Chasing kids around as a babysitter, driving around as an Instacart shopper, and standing around eight hours a day as a barista—when you’re running 20 miles a day—wasn’t ideal. But whatever, she had compression socks. And she was downing free coffee and paying rent, flying to Flagstaff, Arizona, every so often for altitude camps, and having a good time. Doing what she loved. The only thing she’s ever wanted to do since she was a freckly fifth-grader in small-town Wisconsin clocking a six-minute mile in gym class.

“I was hustling, and I loved it. It was such a fun, cool time of my life,” she says, summarizing her 20s. Staring into Molly’s steely brown eyes, listening to her speak with such clarity and conviction about her struggles since, it’s easy to forget: She is still only 29.

After Molly had hip surgery on her birthday in July 2018, her doctors gave her a 50/50 chance of running professionally again. By summer 2019, she’d parted ways with FTC, which left her sobbing on the banks of the Charles River, getting eaten alive by mosquitoes and uncertainty. Her biggest achievement lately had been being named #2 Top Instacart Shopper (in Flagstaff; Boston was big-time).

The day after that rooftop party, Molly asked her friend and former FTC teammate Jon Green, who she’d newly anointed as her coach: “Think I should run the marathon trials?” Sure, he shrugged. Nothing to lose. Maybe it’d help her train for the 10K, her best shot—they both thought—at making a U.S. Olympic team.

“I’m going to get my ass kicked six ways to Sunday!” she told the host of the podcast Running On Om six weeks before the trials in Atlanta.

Instead, on February 29, 2020, she kicked some herself. Pushing past 448 of the fastest, most-experienced women marathoners in the country, coming in second with a 2:27:31, earning more in prize money ($60,000) than she had in two years of racing—and a spot on the U.S. trio for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, along with Kenyan-born superstars Aliphine Tuliamuk and Sally Kipyego. “I don’t know what’s happening right now!” Molly kept saying into TV cameras, wrapped in an American flag, as stunned as a lottery winner.

Saucony who? Puma came calling. Along with something Molly hadn’t anticipated: the spotlight. An onslaught of social media followers. And two weeks later, a global pandemic and lockdown—and all the anxiety and isolation that came with it. She was drowning, and she hadn’t even landed in Tokyo yet.

The 2020 Olympics, as we all know, were postponed to 2021. An emotional burden but a physical boon for Molly, in that it allowed her to get in a second marathon. In London, she finished two minutes faster than her debut. When the Olympics finally rolled around, she was ready.

Before the race, Molly says, “I was thinking: ‘Once I cross the starting line, I get to call myself an Olympian and that’s a win for the day.’”

But then she crossed the finish line—with a finger-kiss to the sky and a guttural Yesss!—in third place with a 2:27:46, just 26 seconds behind first (Kenya’s Peres Jepchirchir). And realized: She gets to call herself an Olympic medalist forever. Only the third American woman to ever earn one in the marathon.

Lots of kids have fleeting hopes of making it to the Olympics. I remember thinking I could be Mary Lou Retton. Maybe FloJo, with shorter fingernails. Then I decided I’d rather be Madonna or president of the United States and promptly forgot about it. But Molly held tight to her Olympic aspirations. She still has a poster she made in 2004, with stickers and a snapshot of her smiley 10-year-old self, to prove it. “I wish I will make it into the Olympics and win a gold medal,” she wrote, and signed it: Molly Seidel, the “y” looping back to underline her name. In case there was any doubt as to who, specifically, would be winning the medal.

Molly grew up in Nashotah, Wisconsin, and is the eldest of three. Her sister and brother, younger by not quite two years, are twins. Izzy is a running influencer and corporate content creator for companies like Peloton; and Fritz favors Formula 1 racing and weightlifting and works for the family’s leather-tanning business. The family was active, sporty. Dad, Fritz Sr., was a ski racer in college; Mom, Anne, a cheerleader. You can tell. Watching clips of Molly’s mom and dad watching the Olympic race from their backyard patio, jumping up and down, tears streaming, is the kind of life-affirming moment you wish you could bottle. “I’m in shock. I’m in disbelief,” Molly says into the mic, beaming. “I just wanted to come out today and I don’t know…stick my nose where it didn’t belong and see what I could come away with. And I guess that’s a medal.” When the interviewer holds up her family on FaceTime, Molly breaks down. “We did it,” she says into the screen between sobs and smiles. “Please drink a beer for me.

Molly hasn’t always been unabashedly herself, even when everyone thought she was. A compartmentalizer to the core, she spent most of her life hiding a huge part of it: anorexia, bulimia, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, debilitating depression.

It started around age 11, when she learned to disguise OCD tendencies, like compulsively knocking on wood, silently reciting prayers “to avoid God getting mad at me,” she says. “It was a whole thing.” She says her parents were aware of the behaviors, but saw them more as odd little habits. “They had no reason to suspect anything. I was very high-functioning,” she says. “They didn’t realize that it was literally taking over my life.”

She wasn’t officially diagnosed with OCD until her freshman year of college, when she saw a therapist for the first time. At Notre Dame, disordered eating took hold, quietly yet visibly, as it does for up to 62 percent of female college athletes, according to the National Eating Disorders Association. As recently as the Tokyo Olympics, she was making herself throw up in the airport bathroom, mere days before taking the podium. Molly hesitates to share that detail; she fears a girl might read this and interpret it as behavior to model. “Having been in that place as a younger athlete, I know I would have,” she says. But she also understands: Most people just don’t get how unrelenting eating disorders can be.

In February 2022, she finally received a diagnosis of the root cause for all of it: ADHD. About being diagnosed, she says, “It made me feel really good, like [I don’t have] a million different disorders. I have a disorder that manifests itself in a lot of different symptoms.”

She waited to try Adderall until after the Boston Marathon in April, only to drop out at mile 16 due to a hip impingement. Initially, the meds made her feel fantastic. Focused. Free. Until she realized Adderall hurt more than it helped. She couldn’t sleep, couldn’t eat, lost too much weight. Within weeks, she devolved. “The eating disorder came roaring back,” she says, referring to it, as she often does, as its own entity, something that exists outside of herself. That ruthlessly takes control over her very need for control. “I almost think of it as an alter ego,” she explains. “Adderall was just bubblegum in the dam,” as she puts it. She ditched the drug, and her life—professionally, physically—unraveled.

In July 2022, heading into the World Championships, she bombed the mental health screening, answering the questions with brutal honesty. She’d been texting Keira D’Amato weeks prior. “Yo girl, things are pretty bad right now. Get ready…” Sobbing on the sidewalk in Eugene, Oregon, she texted D’Amato again. And the USATF made it official: D’Amato would take her spot on the team. Then Molly did what she’d been “putting off and putting off”— checked herself into eating disorder treatment for the second time since 2016, an outpatient program in Salt Lake City, where her new boyfriend was living at the time.

Somehow (see: expert compartmentalizer) mid-meltdown, in February 2022, she had met an amateur ultrarunner named Matt, on Hinge. A quiet, lanky photographer, he didn’t totally get what she did. “I didn’t understand the gravity of it,” he tells me. “I was like, Oh she’s a pro runner, that’s cool. I didn’t realize she was, like, the pro runner!”

Going back to treatment “was pretty terrible,” she says. At least she could stay with Matt. Hardly a honeymoon phase, but the new relationship held promise. “I laid it all out there,” says Molly. “And he was still here for it, for all the messiness. It was really meaningful.” And a mental shift. “He doesn’t see me as just Molly the Runner.”

Almost a year later, on a freezing April evening in Flagstaff, Molly is racing around Whole Foods, palming a head of cabbage, grabbing a thing of hummus, hunting for deals even though she doesn’t need to anymore.

“It’s all about speed, efficiency, and quality,” she says, explaining the secret to her earlier Instacart success. She checks the expiration date on a container of goat cheese and beelines for the butcher counter, scans it faster than an Epson DS3000, though not without calculation, and requests two tomato-and-mozzarella-stuffed chicken breasts. Then she darts over to the beverage aisle in her marshmallow-y Puma slip-ons that Matt custom-painted with orange poppies. She grabs a case of La Croix (tangerine), then zips to the checkout. We’re in and out in under 15 minutes and 50 bucks, nothing bruised or broken.

Other than her body. Let’s just say: If Molly were an avocado or a carton of eggs, she probably wouldn’t pass her own sniff test. The week we meet, she is just coming off a month of no running. Not a single mile. She’s used to running twice a day, 130 miles a week. No wonder she’s spraying her kitchen counter with Mrs. Meyer’s and scrubbing the stovetop within minutes of welcoming me into her new home.

The place, which she shares with Matt and his Australian border collie, Rye, has a post-college flophouse feel: a deep L-shaped couch draped in Pendleton blankets, a bar cluttered with bottles of discount wine, a floor lamp leaning like the Tower of Pisa next to a chew toy in the shape of a ranch dressing bottle. Scattered about, though, are reminders that an elite runner sleeps here. Or at least tries to. (“Pro runner by day, mild insomniac by night” reads the bio on her rarely used account on what used to be Twitter.) There’s a stick of Chafe Safe on the coffee table. Shalane Flanagan’s cookbooks on the counter. And framed in glass, propped on the office floor: Molly’s Olympic kit—blue racing briefs with the Nike Swoosh, a USA singlet, her once-sweat-drenched American flag, folded in a triangle. “I’m not sure where to hang it,” she says. “It seems a little ostentatious to have it in the living room.”

With long brown curls and a round, freckly face, Molly has an aw-shucks look so innocent that it’s hard, at first, to perceive her struggles. Flat-out ask her, though—How are you even functioning?—and she’ll tell you: “I’m an absolute wreck. There’s no worse feeling than being a pro runner who can’t run. You just feel fucking useless.” Tidying a stack of newspapers, she adds, “Don’t worry, I’ve had therapy today.”

She’s watched every show. (Save Ted Lasso, “too sickly sweet.”) Listened to every podcast. (Armchair Expert is a favorite.) She’s got nothing else to do but PT and go easy on the ElliptiGo in the garage, onto which she’s rigged a wooden bookstand, currently clipped with A History of God: The 4,000 Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. “I don’t read running books,” she says. “I need something different.”

Like most runners—even the most amateur among us—running, moving, is what keeps her sane. “What about swimming? Can you at least swim?” I ask, projecting my own desperation if I were in her size 8.5 shoes. “I fucking hate swimming,” says Molly. Walking? “Oh, yeah, I can go on walks. Another. Long. Walk.”

The only thing she has on her schedule this week is pumping up a local middle school track team before their big meet. The invitation boosted her spirits. “Should I just memorize Miracle on Ice?” she says, laughing. “No, I know, I’ll do Independence Day.”

Injuries are nothing new for Molly. Par for the course for any professional athlete. But especially for women, like her, who lack bone density—and have since high school, when, according to a study in the Orthopedic Journal of Sports Medicine, nearly half of female runners experience period loss. Osteoporosis and its precursor, osteopenia, are rampant in female runners, leading to ongoing issues that threaten not just their college and professional running careers, but their lives.

Still, Molly admits, laughing: She’s especially accident-prone. I ask her to list every scratch she’s ever had, which takes her 10 minutes, and goes all the way back to babyhood, when she banged her head against the bathtub spout. There was a cracked spine from a sledding incident in 8th grade, a broken collarbone from a ski race in high school, shredded knee cartilage in college when a driver hit her while she was riding a bike. “Ribs are constantly breaking,” she says. In 2021, two snapped, and refused to heal in time for the New York City Marathon. No biggie. She ran through the pain with a 2:24:42, besting Deena Kastor’s 2008 time by more than a minute and setting the American course record.

Molly’s latest injury? Glute tear. “Literally a gigantic pain in the ass,” she posted on Instagram in March. Inside, Molly was devastated. Pulling out of the Nagoya Marathon—the night before her 6:45 a.m. flight to Japan, no less—was not in the plan. The plan, according to Coach Green, had been simple. It always is. If the two of them even have one. “Just to have fun and be consistent.” And get a marathon or two in before the Olympic Trials in February 2024.

She’d been finally—finally—fit on all fronts; ready to race, ready to return. She needed Nagoya. And then, nothing. “It feels like I’m back at the bottom of the well,” says Molly, driving home from Whole Foods in her Toyota 4Runner. “This last year-and-a-half has been so difficult. It’s just been a lot of doubt. How do I approach this, as someone who has now won a medal? Like, man, am I even relevant in this sport anymore?” She pops a piece of gum in her mouth. I wait for her to offer me some, because that’s what you do with gum, but she doesn’t. She’s so in her head. “It’s hard when you’re in the thick of it, you know, to figure out: Why the fuck do I keep doing this? When it just breaks my heart over and over and over again?”

We pull into her driveway. “I was prepared for the low period after Tokyo,” she says. “But this has been much longer and lower than I expected.”

The curse of making it to the Olympics, let alone coming back with a medal: expectations. Molly’s own were high. “I think I thought, after the Olympics, if I win a medal, then I will be fixed, it will fix everything.” Instead, in a way, it made everything worse.

That’s the problem that has plagued Molly for most of her running career: Her triumphs and troubles intermingle, like thunder and lightning. Which, by the way, she has been struck by. (A minor backyard-grill, summer-thunderstorm incident. She was fine.)

The next morning in Flagstaff, Molly’s feeling like she can run a mile, maybe two. It’s snowing, though, and she doesn’t want to risk the slippery track, so we meet at Campbell Mesa Trails. She loops a band around the back of her truck to stretch and sends me off into the trees to run alone while she does a couple of laps on the street.

Molly leaves for an acupuncture appointment, and we reunite later at Single Speed Coffee (“the best coffee in Flagstaff,” promises the ex-barista who drinks up to three cups a day). We curl up on a couch like it’s her living room, and she talks as freely—and as loudly—as if it was. Does she realize everyone can hear her? She doesn’t care. I guess that’s what happens when you’ve grown so comfortable sharing—in therapy, on podcasts, in a three-part video series on ADHD for WebMD—you just…share. Loud and proud.

Mental illness is so insidious, says Molly. “It’s not always this Sylvia Plath stick-my-head-in-a-fucking-oven thing, where you’re sad all the time,” she says. “High-functioning depressed people live normal successful lives. I can be having the happiest moment, and three days later I’m in a total downward spiral.” It’s something you never recover from, she says, but you learn to manage.

“I’m this incredibly flawed person who struggles so much. I think: How could I have won this thing when I’m so flawed? I look at all the people around me, all these accomplished people who have their shit together, and I’m like, ‘one of these things is not like the other,’” she says, taking a sip of her flat white. “I was literally in the Olympic Village thinking: Everybody is probably looking at me wondering: Why the hell is she here?”

They weren’t. They don’t. She knows that.

And yet her mind races as fast as she does. It takes up So. Much. Space. When she’s running, though, the noise disappears. She’s not Olympic Molly or Eating Disorder Molly, she’s not even, really, Runner Molly. “When I’m running,” she says, “I’m the most authentic version of myself.”

Talking helps, too. Molly first shared her mental health history a few years ago, “before she was famous,” as she puts it. After the Olympics, though, she kept talking and hasn’t stopped. The Tokyo Games were a turning point, she says. Suddenly the most revered athletes in the world were opening up about their mental health. Molly credits Simone Biles’s bravery for her own. If Biles, and Michael Phelps and Naomi Osaka, could come clean... then maybe a nerdy, niche-y, unlikely medaling marathoner could, too.

“Those guys got a lot more shit for it than I did,” says Molly. “I got off easy. I’m not a household name,” she laughs. She knows she can be candid and off the cuff—and chat freely in a not-empty café—in a way Biles never could. “I’m a nobody!” she laughs.

Still, a nobody with 232,000 Instagram followers whom she has touched in very IRL ways—becoming an unintentional poster woman for normalizing mental health challenges among athletes. “You are such an incredible inspiration,” @1percentpeterson posts, one comment of a zillion similar. “It’s ok to not be ok!” says another. Along with all the online love is, of course, online hate. Molly rattles off a few lowlights: “She’s an attention-seeking whore,” “Her bones are so brittle she’ll never race again,” “She’s running so badly and posting a lot she should really focus on her running more.” Molly finds it curious. “I’m like, ‘If you hate me, you don’t need to follow me, sir.’”

It’s Molly’s nobody-ness—what Outside writer Martin Fritz Huber called her “runner-next-door” persona, and I’ll just call “genuine personality”—that has made her somebody in running’s otherwise reserved circles.

Somebody who (gasp!) high-fives her sister in the middle of a major race, as she did at mile 18 of the 2021 New York City Marathon. “They shat on me in the broadcast for it,” she says. “They were like, ‘She’s not taking this seriously.’” (Except, uh, then she set the American course record, so…)

Somebody who, obviously, swears like a sailor and dances awkwardly on Instagram, who dresses up like a turkey, and viral-tweets about getting mansplained on an airplane. (“He starts telling me how I need to train high mileage & pulls up an analysis he’d made of a pro runner’s training on his phone. The pro runner was me. It was my training. Didn’t have the heart to tell him.”)

Somebody who makes every middle-aged mom-runner I know swoon like a Swiftie and say: “OMG! YOU HUNG OUT WITH MOLLY SEIDEL!!?” Middle-aged dad-runners, too. “I saw her once in Golden Gate Park!” my friend Dan fanboyed when he heard. “I waved!” Did she wave back? “She smiled,” he says, “while casually laying down 5:25s.”

And somebody who was as outraged as I was that I bought a $16 tube of French toothpaste from my hip Flagstaff motel. (It was 10 p.m.! It was all they had!) “For that price it better contain top-shelf cocaine,” she texted. Lest LetsRun commenters take that tidbit out of context: It’s a joke. It’s, in part, what makes Molly America’s most relatable pro runner: She’s not afraid to make jokes. (While we’re at it… Don’t knock her for smoking a little legal weed, either. That’s so 2009. Per the World Anti-Doping Agency: Cannabis is prohibited during competition, not at a Christmas party two months before it. Per Molly: “People would be shocked to know how many pro runners smoke weed.”)

I can’t believe I never asked to see it. Molly’s medal. A real, live Olympic medal. Maybe because it was tucked into a credenza along with Matt’s menorah and her maneki-neko cat figurines from Japan. But I think it was because hanging out with Molly felt so…normal, I almost forgot she’d won one.

People think elite distance runners have to be one-dimensional, she says. That they have to be sculpted, single-minded, running-only robots. “Because that’s what the sport has been,” she says.

Molly falls for it, too, she says. She scrolls the feeds, sees her fellow pros living seemingly perfect lives. She wants everyone to know: She’s not. So much so that she requested we not print the photos originally commissioned for this story, which were taken when she was at the lowest of lows. (“It’s been...refreshing...to be pretty open and real with Rachel [about] the challenges of the last year,” she wrote in an email to Runner’s World editors. “But the photos [were taken at] a time when I was really struggling and actively trying to hide how bad my eating disorder had become.”)

Molly finds the NYC Marathon high-five thing comical but indicative of a more serious issue in elite running: It takes itself too seriously. It’s too…elitist. Too stilted. “Running a marathon is a pretty freaking cool experience!” If you’re not having fun, she asks rhetorically, what’s the point? Still, she admits, she isn’t always having fun. Though you wouldn’t know it from her Instagram. “Oh, I’m very good at making it seem like I am,” she says.

She used to enjoy social media when it was just her friends. Before she gained 50,000 followers in a single day after the trials, and some 70,000 on Strava. Before the pandemic, before the Olympics. Keeping up with content became a toxic chore. “You feel like you’re just feeding this beast and it’s never going to stop,” she says. She’s taken to deleting the app off her phone, reloading it only to fulfill contractual agreements and post for her sponsors, then deleting it again.

As much as she hates having to post, she enjoys plugging products the only way that feels natural: through parody. As does Izzy, her influencer sister, who, like Molly, prefers to skewer rather than shill (à la their idea behind their joint Insta account: @sadgirltrackclub). “The classic influencer tropes make me want to throw up,” she says (perverse pun as a recovering bulimic not intended). “New Gear Drop!’ or ‘This is my Outfit of the Day!’ Cringe. “Hot Girl Instagram is not how I identify,” she says.

Nor is TikTok. “Sponsors tell me all the time: You should TikTok! I’m like, ‘I am not doing TikTok.’ I know how my brain works. They’ll say, ‘We’ll pay you less if you don’t’—and I’m, like, I don’t care.”

And to those sponsors who ghosted her after she returned to eating disorder treatment, good riddance. “Michelob dropped me like a bad habit,” she says. “Whatever. You have watery-ass beer anyway.”

To those who have stood by her, though, she’s utterly devoted. Pissed she couldn’t wear the Puma panther head to toe in Tokyo, Molly took off her Puma Deviate Elites and tied them over her shoulder, obscuring the Nike logo on her Olympic singlet for all the world to see. Or not see. “Nike isn’t paying my fucking bills.”

The love is mutual, says Erin Longin, a general manager at Puma. After decades backing legends like Usain Bolt, Puma was relaunching road running and wanted Molly as their guinea pig. “She’s a serious athlete and competitor, but she also has fun with it,” says Longin. “Running should be fun. Molly embodies that.” At their first meeting, in January 2020, Molly made them laugh and nerded out over their new shoes. “We all left there, fingers crossed she’d sign with us,” says Longin.

Come February, they all flipped out. Longin was watching the trials, not expecting much. And then: “We were all messaging, “OMG!!” Then Molly killed in London. Medaled in Tokyo. “What she did for us in that first year…” says Longin. “We couldn’t have planned it!”

Then came the second year, and the third, and throughout it all—injuries, eating disorder treatment, missed races, missed opportunities—Puma hasn’t flinched. “It’s easy for a company to do the right thing when everything is going great,” Molly posted in April, heartbroken from her couch instead of Heartbreak Hill. “But it’s when the sh*t hits the fan and they’re still right there with you….” She received 35,000 hearts—and a call from Longin: “You make me feel so proud.”

Does it matter to Puma if Molly never places—never races—again? “Nope,” Longin says.

My last afternoon in Flagstaff, it’s cloudy skies, still freezing. I find Molly on the high school track wearing neoprene gloves, black puffy coat, another pair of Pumas. Her breath is white, her cheeks red. Her legs churning in even, elegant strides. Upright, alone, at peace, backed by snow-dusted peaks. Running itself is what matters, not racing, she tells me. “I honestly don’t give a shit about winning,” she says. All she wants—really wants, she says—is to be healthy enough to run until she’s old and gray.

Molly’s favorite runner is one who didn’t get to grow old. Who made his mark decades before she was born: Steve Prefontaine. “Pre raced in such a genuine way. He made people feel something,” she says. “The sports performances you truly remember,” she adds, “are the ones where you see the struggle, the work, the realness.”

Sounds familiar. “I hate conversations like, ‘Who’s the GOAT?’” Molly continues. “Who fucking cares? Who’s got the story that’s going to get people excited? That’s going to make some kid want to go out and do it?”

I know one of those kids: My best friend’s daughter, Quinn, a rising track phenom in Oregon, who has dealt with anxiety and OCD tendencies. She has a picture of Molly Seidel, and her times, taped to her bedroom wall. This past May, Quinn joined Nike’s Bowerman Club. She was named Oregon Female Athlete of the Year Under 12 by USATF. She wants to run for Notre Dame.

“Quinn loves running more than anything,” her mom tells me, texting photos of her elated 11-year-old atop the podium. “But I don’t know…” She’s unsure about setting her daughter on this path. How could she not, though? It’s all Quinn wants to do. Maybe what Quinn, too, feels born to do.

It’ll be okay, I tell her, I hope. Quinn has something Molly never had: She has a Molly.

Molly and I catch up via phone in June. A team of doctors in Germany has overhauled her biomechanics. She’s been running 110 miles a week, feeling healthy, hopeful. Happy. A month later, severe anemia (and accompanying iron infusions) interrupts her summer racing schedule. She cancels the couple of 10Ks she had planned and entertains herself by popping into the UTMB Speedgoat Mountain Race: a 28K trail run through Utah’s Little Cottonwood Canyon—coming in second with a 3:49:58. Molly’s focus is on the Chicago Marathon, October 8th; her first major race in almost two years.

Does it matter how she does? Does it matter if she slays the Olympic Trials in February? If she makes it to Paris 2024? If she fulfills her childhood dream and brings home gold?

Nah. Not if—like Matt, like Puma, like, finally, even Molly herself—you see Molly the Runner for who she really is: Molly the Mere Mortal. She’s the imperfect one who puts it perfectly: What matters isn’t her time or place, how she performs on the pavement. Or social media posts. What matters—as a professional athlete, as a person—is how she makes people feel: human.

She’d been finally—finally—fit on all fronts; ready to race, ready to return. She needed Nagoya. And then, nothing. “It feels like I’m back at the bottom of the well,” says Molly, driving home from Whole Foods in her Toyota 4Runner. “This last year-and-a-half has been so difficult. It’s just been a lot of doubt. How do I approach this, as someone who has now won a medal? Like, man, am I even relevant in this sport anymore?” She pops a piece of gum in her mouth. I wait for her to offer me some, because that’s what you do with gum, but she doesn’t. She’s so in her head. “It’s hard when you’re in the thick of it, you know, to figure out: Why the fuck do I keep doing this? When it just breaks my heart over and over and over again?”

(10/08/2023) ⚡AMPby Runner’s World

Armed with Smarts and Science, Camille Herron Sets an Astounding Record in Greece

The American ultrarunner credits patience and reduced carbohydrate intake to helping her smash the women’s course record in the Spartathlon, the iconic 153-mile race from Athens to Sparta

Camille Herron continues up to her usual record-breaking ways, smashing the women’s record at the 40th edition of the daunting Spartathlon ultra-distance running event in Greece on October 2.

Herron, a 41-year-old Lululemon-sponsored runner from Warr Acres, Oklahoma, covered the 153-mile course in 22 hours, 35 minutes and 30 seconds. She shaved more than two hours off the previous record and became the first woman to finish the course in under 24 hours in the 40-year history of the race.

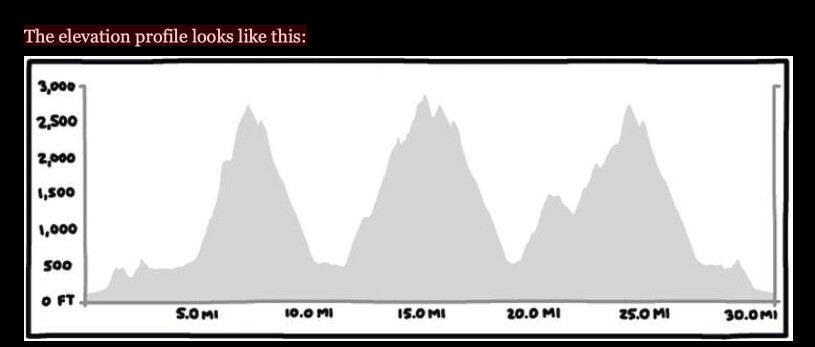

Spartathlon was created in 1983 to send runners on a journey following the ancient route of Pheidippides, a courier who ran the distance between Athens and Sparta to seek military aid during a battle against the Persians in 490 B.C.. The modern-day race route includes flat roads and mountainous trails with more than 10,000 feet of elevation gain.

Incredibly, Herron averaged 8:55 mile pace, with her fastest mile clocking in at 6:28 (for the seventh mile).

“Wow, it was so much fun because we were running in the footsteps of Phidippides,” Herron says. “The whole time I was running, I was just trying to imagine what he did running on those ancient roads and paths. It’s a little different nowadays having cars and like all these things we have to dodge along the way. But it was incredible. I just loved the whole day because I love both road running and trail running and the course had big sections of each. To have a race that combined all of that, the process in my mind was all about a journey to a destination.”

Greek runner Fotis Zisimopoulos was the overall winner in 19:55:09, a new course record that broke the longstanding mark of 20:25:00 by ultrarunning legend Yiannis Kouros in 1984. Herron finished third overall behind Zisimopoulos and Norway’s Simen Holvik (22:35:31) and shattered the women’s record of 24:48:18 set by Poland’s Patrycja Bereznowska in 2018.

The Spartathlon course starts with a fast urban road section between Athens and Corinth—where dodging vehicles, traffic and pedestrians is necessary—before transitioning onto trails and meandering through vineyards and orchards before eventually going into the Geraneia Mountains. The final section of the course consists of downhill and flat road sections that lead to Sparta.

As she’s known to do, Herron started fast. But she was surprised to have five other women running seven-minute mile pace alongside her. She made a judgment call to slow down a bit, knowing she had a lot of running ahead of her and needed to save her legs.

“In my mind I’m thinking, ‘This is way too fast,’” Herron says. “I was worried we weren’t going to have our legs under us to hit the mountain section. So I ended up just backing off and let all of these women go. They were just hammering it. I was like, ‘Whoa, this is crazy!’ But at the same time, I was inspired by the other women in the race that they had the courage and the strength to go for it. I was like, ‘Hey, you go girl.’”

Finland’s Noora Honkala and Satu Lipiäinen were at the front, followed by Hungary’s Szvetlana Zétényi, Switzerland’s Stine Rex and Germany’s Sarah Mangler. They all wound up building 10- to 30-minute gaps on Herron. But when they entered the trail section with significant climbing, Herron tapped into her uphill abilities and started closing the deficits to the other women. Once back on the roads, she snapped back into her quintessential quick stride turnover and quickly made up the 12-minute gap to pass Lipiäinen, the second-place woman.

Out front, Honkala ran fast and pushed the pace the whole day. When she entered the mountain phase of the race, she had a 26-minute gap on Herron. But Herron’s relatively strong trail and downhill running abilities paid huge dividends, and with 20 more miles to go, she caught and passed Honkala. Herron surged the rest of the way, ultimately building a gap of more than 50 minutes on Honkala (23:23:03). Lipiäinen finished third (23:48:34), followed by Zétényi (27:57:49) and Rex (28:18:35) in what was the most competitive women’s race in the history of the event.

Herron continues to improve with age, especially in longer events. In February, she set multiple masters world records and U.S. records at the Raven 24-Hour race in South Carolina, running 150.43K (93.47 miles) in 12 hours, and then crossing the 100-mile mark in 12:52:50.

Then in March, Herron set a new women’s world record after logging 435.336K (or 270.505 miles) in 48 hours at the Sri Chinmoy 48-Hour Festival in Canberra, Australia. That mark not only broke the existing women’s 48-hour world record of 411.458K (255.668 miles) set by U.K. runner Joasia Zakrzewski, but it also surpassed the all-time American record of 421.939K (262.181 miles) previously set by Olivier LeBlond in 2017. In surpassing LeBlond’s mark, Herron became the first female runner ever to hold an overall American record at any distance.

Herron credits her recent testing with Trent Stellingwerff, the Director of Innovation and Research at the Canadian Sports Institute, for helping discover that Herron has a high VO2 max and produces a naturally high fat oxidation rate when she’s running long distances. Herron underwent that testing as part of Lululemon’s FURTHER initiative, which is backing scientific studies for women as a means to better understand women’s sports performance.

Working with her dietician, Herron used that knowledge to cut back on her carbohydrate intake during Spartathlon to less than 50 grams per hour, down from the 60 to 75 grams per hour that she had been consuming in events earlier this year and in prior years.

Her main source of fueling? Aside from taking a gel every hour, she consumed sections of honey and salt sandwiches that her husband and coach, Conor Holt, served her at aid stations.

“Those changes were life-changing,” Herron says. “I mean, you hear about athletes in marathons and shorter races that are trying to increase carbohydrate intake. But we learned my body is naturally wired for fat oxidation, so I ended up backing off my carbohydrate intake and it made me feel better. It just paid off later in the race. I wasn’t having the gut problems I’ve had in the past, so I was able to just run like a ‘Steady Freddie’ and perform better. It just shows the longer I go, the stronger I am, and I’m able to really show what my natural physiology is capable of beyond a hundred miles.”

Colt said Herron’s training also played a key role in her success. She put in significant mileage during stints in Oregon, Colorado, and Oklahoma during the summer and then arrived in Greece a week before the race so she could run the course over several days.

“We did our homework and we did the training and she was ready,” Colt says. “She’s got a few more good, good ones in her, I think.”

Herron dedicated her performance to German ultrarunner and friend Nele Alder-Baerens, who is suffering from Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and can no longer compete. She said she’s inspired by women like Alder-Baerens, who holds the world record for running 85.492K (53.1 miles) in six hours.

She’s grateful for the opportunities Lululemon is providing and is excited to see what continued sports science testing with the Canadian Sports Institute will reveal, especially as it relates to adapting to training and racing through perimenopause.

“It’s important for the general visibility of women and showing what happens when a brand really gets behind women,” Herron says. “Most sports science is based on men, but we’re studying women. I mean, we’re making it happen. The support from Lululemon has just been incredible. And it just goes to show what happens when women are supported in sports. It feels like there’s no ceiling.”

(10/07/2023) ⚡AMPby Outside Online

He Qualified for Team USA. Then Came the Bill.

Even as trail and ultrarunning explode, the spoils of professionalization aren’t spread equally across the sport. Athletes on this year’s U.S. 24-hour team are looking to change that

Scott Traer qualified for his first U.S. national team more than a decade ago in 2012. He was new to the sport and naive about what it took to compete at the international level—even after being selected as one of the country’s best athletes in the 24-hour discipline, a niche tributary of trail and ultrarunning where athletes complete as many laps around a track as possible within 24 hours.

While the 24-hour race format may seem eccentric, well-known names like Courtney Dauwalter, Kilian Jornet, and Camille Heron have dabbled in the ultra-track scene. International governing bodies regulate the discipline with USA Track & Field (USATF), the national governing body for track and field, cross country, road running, race walking, and mountain-ultra-trail (MUT) disciplines, overseeing the American contingent.

Traer, then 31, was working odd construction jobs in and around Boston to make ends meet while training when he got the call from USATF that he had been selected for Team USA.

“I was really excited,” says Traer. “Then, I found out that I had to pay for everything. So I was like, ‘Forget about it.’”

That financial reality took the wind out of Traer’s sails. He didn’t have the disposable income to foot the bill for international travel and didn’t have paid time off from his jobs. While he was disappointed that he wouldn’t get to represent his country in 2012, he was still determined to pursue his dream of chasing a career in coaching and racing.

Now, Traer, 42, is a full-time coach living near Phoenix and working with the Arizona-based event organization Aravaipa Running as an assistant race director. He has earned top accolades in the sport, including a course record at the Javelina 100K and a Golden Ticket to Western States at the Black Canyons 100K, eventually leading to a top-ten finish at the Western States Endurance Run.

True to his blue-collar roots, he is known for racing in unbranded gear, typically a long-sleeve, white SPF shirt unbuttoned and flapping in time with his stride. Ten years after making his first 24-hour team, he re-qualified for the opportunity to compete for the U.S. again, this time for the 2023 IAU 24-Hour World Championships in Taiwan (which international sports federating bodies officially refer to as Chinese Taipei), on December 2.

The catch: USATF is only providing a stipend of $600 to Team USA athletes.

Oregon ultrarunner Pam Smith has competed on Team USA seven times in the 24-hour and 100K world championship events. Now, she’s serving as the Team USA manager to help steward the next generation of ultra athletes. But that passion has come at a cost.

“I estimate I’ve spent around $10,000 in personal funds to be able to compete at the world championships and to represent the USA at these events,” says Smith, 49, who finished fourth at the 2019 IAU World Championships in France. “USATF does pay for the manager’s travel expenses, but there is no other compensation; in fact, the managers have to use their own funds to cover some fees, like membership dues and background checks.”

It might surprise fans of the sport that many of their favorite athletes are paying significant money to sport the red, white, and blue uniform—and that many can’t compete because they cannot shoulder the cost. The U.S. is known for strong 24-hour runners, and the men’s and women’s teams both won gold at the previous IAU 24-Hour World Championships in 2019 in Albi, France, with two individual podium spots.

“The U.S. has many of the best 24-hour runners in the world,” says Smith. “It’s a shame that these athletes don’t even get their airfare covered.”

While Smith’s airfare is covered, her work and that of her colleagues is presumed to be done on a volunteer basis. (A quick online search shows a flight to Chinese Taipei from most U.S. cities costs in the $1,500-$2,400 price range.)

Trail running, particularly the elite side of the sport, is at an inflection point. While some races dole out prize money, and a select few athletes at the top of the sport command respectable salaries, most runners at the elite level rely on a scattershot combination of brand partnerships and personal funding to float their racing. While the sport’s very best athletes are well compensated professionals, most “sponsored” trail runners earn between $10,000 and $30,000 per year. Between travel, gear, nutrition, and other expenses, many runners at the elite level are fronting their own cash to compete.

When Chad Lasater qualified for Team USA after a strong run at the Desert Solstice 24-Hour Race, he hadn’t planned on making the team. But, when he found out he’d qualified, he started looking into the logistics and was shocked to discover he’d be responsible for paying his way to Taipei.

“The cost of airfare, lodging, food, and time away from work can be significant, especially when traveling to somewhere like Taipei,” says Lasater, 51, from Sugar Land, Texas. “I feel that everyone should have an equal opportunity to be on the U.S. team, and the cost of traveling to the world championships should not preclude anyone from accepting a spot on the team. We should really be sending our best 24-hour athletes to the world championships, not the best athletes who can afford to travel.”

Teams that rely on individual brands or athletes to foot the bill will prefer runners with sponsorships or disposable income and can afford to take time off work and pay for childcare.

At the top of the sport, like the world championships, it’s routine to see completely unsponsored runners competing with no brand affiliation, especially in the eccentric realm of 24-hour track events. Even some sponsored runners don’t always get their travel expenses covered.

While a world championship event is certainly a big deal, it doesn’t command the same fanfare and media attention as other marquee events, like the Western States Endurance Run or Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc, where many brands prefer to focus their resources.

Jeff Colt, a 32-year-old professional ultrarunner for On who lives in Carbondale, Colorado, publicly debated the merits of returning to Western States in California this year or competing in the 2023 World Mountain and Trail Running Championships in Austria in early June. (The trail running world championships and 24-hour world championships are different events, but the Team USA athletes who compete in each one face similar challenges when it comes to funding and market value to brands.) He ultimately decided to claim his Golden Ticket and compete at States. More eyeballs on the event mean a higher return on the investment for running brands, which in turn elevates athletes’ value to their sponsors

“My sponsor, On, was clear that they supported my decision either way, but they were more interested in me running Western States,” says Colt. “And rightfully so. There’s a lot of media attention at races like States and UTMB, which allow brands to activate and get visibility for their logo. That support feels good as an athlete, too. It’s not just better for the brand.”

Nike has an exclusive partnership with USATF; all athletes competing at any world championship event in the mountain-ultra-trail disciplines (as well as the Olympics and World Athletics Championships for track and field and the marathon) must wear Nike-issued Team USA uniforms that are provided to the athletes free of charge, with the exception of shoes. Any photos or videos of professional runners at these events are less valuable to competing running brands because their athletes will appear bedecked in another company’s logo. This disincentivizes many brands from investing in unsponsored athletes’ travel expenses and limits athletes’ ability to get financial support, most of which currently comes from shoe and apparel brands in the trail running industry. And if athletes cannot compete because of illness or injury, they must return parts of the kit. Even if they keep the kit, many sponsored runners’ contracts prohibit them from training and racing in the gear, so it gathers dust at the back of their closets.

Arizona runner Nick Coury, preparing to compete on his third U.S. 24-hour team, says this contract limits the economic opportunities of unsponsored athletes—partially because it disallows an athlete to place another sponsor’s logo on the Nike gear.

“This is especially upsetting to many because Nike provides large sums of money to USATF for this arrangement, yet neither passes through significant support to national teams despite USATF being a nonprofit aimed at ‘driving competitive excellence and popular engagement in our sport,’” says Coury, 35, from Scottsdale, Arizona. “USATF is taking money from Nike, restricting elite athletes to fund themselves through sponsorship, and doing little to nothing to encourage a competitive national team.”

One athlete, sharing anonymously, reported selling parts of their Nike kit to help offset travel expenses. “It’s the same kit [100-meter and 200-meter track and field superstar] Noah Lyles wears, so it’s super valuable.”

Traer thinks it’s unfair that athletes are forced to wear Nike gear and render free labor supporting a huge company, especially when the 24-hour team isn’t fully funded. Lyles, an Adidas athlete who won the 100-meter dash at this year’s World Athletics Championships in Budapest, had to wear Nike gear while warming up and racing, too. But his travel and expenses were paid in full by USATF, and his Adidas relationship benefits because track and field stars get considerably more exposure than ultrarunners. Furthermore, in track and field, the world championships serve as a prelude to the biggest running event on the calendar, the Olympics, which take place every four years and attract an expansive viewership that reaches far beyond hardcore running fans.

“It bothers me because Nike is making a huge amount of money,” Traer says. “I don’t want to hear that there isn’t enough money to support athletes because I see smaller brands in our sport that have less money doing a much better job supporting athletes.”

Nancy Hobbs is the chairperson of the USATF Mountain and Ultra Trail Running Council, the division of USATF that oversees the U.S. 24-Hour Team. Her executive committee has been discussing more equitable distribution of funds. Initially, funding was based on the number of years the championships had been held and how many athletes were attending.

Ultimately though, it comes down to the relatively small amount of Nike money that USATF allocates to the USATF MUT Running Council.

“With a certain amount of money in the budget, we could choose to send fewer athletes (i.e., just a scoring team with no spares in case of injury, etc.), but the council discussion has been on the importance of fielding a full team with some additional athletes for attrition and providing more athletes an opportunity to compete internationally (provided they qualify for the team based on selection criteria),” says Hobbs.

Though the compensation for mountain-ultra-trail athletes may feel low, it is significantly higher than in the past. In 1999, a mere $250 was distributed to each MUT subcommittee, totaling $750 for all 1999 expenses. In 2013, MUT teams received $25,000 in funding for travel. This year, $83,000 was distributed across all of the teams it sends to international championships for MUT disciplines.

“We’ve come a long way with MUT since 1998,” says Hobbs. “We have more work to do. This is a volunteer-driven group which is passionate about our sport and trying to provide athletes opportunities through championships, teams, and programs within the structure of USATF.”

Coury qualified for his third U.S. 24-hour team in 2021 and broke the American 24-hour record. He’s had to fund his travel out of pocket for all three international appearances. He says the lack of funding limits the team’s ability to compete on the world stage.

“I’ve found it extremely challenging to train for a 24-hour event while holding a full-time job, as have others, and I know I haven’t and won’t hit my personal potential as a result,” says Coury. “We’ve seen an explosion in the competitiveness and interest in trail races, and part of that is the ability for ultrarunners to make a living as professional athletes. We see very few runners in the 24-hour space who can go professional, which reflects in our team’s competitiveness.”

While Team USA won both gold medals in 2019, international competition is escalating. Coury says opening up additional funding would help draw elites and strong amateurs alike to try their hand at the 24-hour format, which would help Team USA’s standing on the world stage.

“Athletes like Courtney Dauwalter and Camille Herron have represented Team USA multiple times and been key to our results,” says Coury. “Yet I am certain they must weigh training, qualifying, and representing Team USA against the sponsorship opportunities in trail ultrarunning, where financial support is much greater. I imagine there would be more interest from some of our most capable athletes if we had a better financial story around the team, providing a path for it to fund an athlete’s career instead of costing out of pocket. Given the prospects of making a living at a trail race versus paying to represent Team USA, I’m positive we’re discouraging some of our best athletes from even wanting to try.”

In previous years, Team USA has resorted to raising money through bake sales and selling T-shirts to raise funds for the team’s travel expenses. Past team captain Howard Nippert made and sold ice bandanas to support the team. This year’s captain Smith is hosting fundraising dinners. Coury says that the ultrarunning community has stepped up to support the team where traditional funding has failed.

“It reminds me in some ways of the amateur athlete situation back in the 1970s, where representing your country came at a significant financial burden and really made athletes reconsider it,” says Coury. “Why isn’t USATF making it desirable to train and compete for Team USA? Why is it seemingly doing the opposite?”

The 24-hour team is at a crossroads: either it will receive adequate funding and support to send the best team possible to the world championships, or it will maintain this status quo while Team USA falls further and further behind on the international stage. Traer has launched a petition on Change.org to draw attention to the funding issue and is determined to sound the alarm about how a lack of funding holds athletes and all of Team USA back.

“No one should have to decide that they made Team USA but can’t afford to pay to wear their country’s flag,” says Traer. “If an athlete earns their spot on the team, they should get the support they need to compete. End of story.”

(10/07/2023) ⚡AMPby Outside Online

3 Athletes on Why They’re Running the Marine Corps Marathon

One of the largest marathons in the world to draw in 30,000 runners from all 50 states

The 48th Marine Corps Marathon (MCM)—“The People’s Marathon”—is the fourth-largest marathon in the U.S. and largest urban ultramarathon (they offer a 50K and 10K, too).

Each year, the U.S. Marine Corps holds the MCM a few weeks before the anniversary of its establishment. On October 29, 30,000 runners will toe the line in Arlington, Virginia, to follow the course as it winds through the nation’s capital. We caught up with three runners aiming for the finish line this year.

Rosie Gagnon, who lives in Berryville, Virginia, will be running the 50K MCM race in honor of her son, Marine Corps veteran, James Morris, who passed away by suicide in Ferurary 2018.

Even struggling through his mental health battles, Morris had endless confidence in his mother. Though Gagnon had been a runner for over two decades, Morris had encouraged her to run her first marathon. And when she completed that, he challenged her to dream even bigger–a 100 miler.

Morris passed away while Gagnon was training for this ultra, but she was determined to keep running in his memory.

“I actually bonked really hard,” Gagnon says, laughing. “I quit 60 miles in. I reached a point where I hit a wall–throwing up and crawling on the ground–and felt it was symbolic of what my son had gone through, because he got to the point where he couldn’t see how he could go on.”

The pain of this first race was disappointing but also a blessing. Morris says the experience taught her that, no matter how dark life gets, you keep putting one foot in front of the other.

Shortly after, Gagnon joined Wear Blue: Run to Remember, a group that honors the service of American military members through running. You may have seen one of them at races across the country wearing their bright blue shirts and the name of a fallen veteran. Gagnon challenged herself to run 100 ultramarathons in memory of Morris, and to raise awareness about military and veteran suicide. This will be her first time running the Marine Corps Marathon, and it will be her 60th ultra.

Running has become not only an outlet for spreading awareness about the importance of military mental health awareness and resources, but it’s been an outlet for grief.

“I used to wake up everyday wondering, ‘How can I live with this pain for another 40 years?’ and the one outlet where I found comfort was through running,” Gagnon says. “I focused on one race at a time, trying to get to that 100. I thought it would take longer, but it’s been moving pretty fast. I’m more than halfway through now!”

“If all I can do is put on shoes and run for somebody,” she says. “I’m going to do that.”

Between working a full-time job, managing clients in her running coach business, and raising three kids under the age of six, Kelly Vigil squeezes in training for the MCM when she can. Originally from northern Virginia, Vigil now lives in Charleston, South Carolina, and has run the MCM four times. This year, she’s running the 50K option.

“It’s my all-time favorite race,” she says. “When you get there, everything is taken care of,and everyone is super excited to be there. The spectators are amazing, which is hard to get in a marathon unless you’re running one of the major ones. At mile 21, you still have people cheering you on.”

Her husband was in the Marine Corps for six years, which makes her particularly connected to the race. Another reason is because Vigil used to work full-time in the charity running field, working with organizations to create their race programs.

“Athletes who are running for a cause aren’t necessarily going to feel more pressure, but there’s more meaning as to why they’re doing it,” Vigil says. “It helps them push forward when their body or mind isn’t in it anymore.”

As a mom of young kids, training isn’t always easy, but Vigil gets it done. Her long runs are timed so that she has an allotted amount of time to be away training on Saturday. Whatever mileage she gets done is what it is, and Vigil is happy with that.

“I’m not very strict with my training plan,” she says. “A lot of my running includes a stroller (with my two-year-old) or I might split up my runs in the morning and evening. I’m just doing what I can.”

Also a certified running coach, Vigil is currently working with other athletes who are running the MCM.

“Coaching keeps me in the community even when I’m not training for something,,” she says. “We’re all going after these different goals and doing what we can to stay consistent and do the work.”

For some, a commute to work includes traffic, to-go coffee, and a few swear words as someone cuts you off on the highway. But Jessica Hood’s commute to the office involves lots of marathon training.

Hood is extremely busy, so she puts in her miles by running to work. The total distance from her house to her office is about 14 miles, but depending on her training schedule, she’ll run seven or so and then hop on the metro bus for the rest of the way. Her office has a gym and showers, so she’s not taking a seat at her desk in sweaty running clothes.

“I do what I have to do and it probably takes a shorter amount of time,” Hood laughs. “You know, because you’d be sitting in DC traffic.”

Hood moved to the DC area about two years ago and works in finance, but her main passion is running. She began posting running content on social media in 2022 and developed a hearty following of 37k on Instagram and 81.5k on TikTok.

“It’s super cool how runners can get connected through social media,” she says. “I have a lot of running friends who don’t live in DC, but we all meet up at certain events and races across the country.”

Because of her influencer status, Hood is part of the MCM Social Media Influencer program, where she’s an advocate for the race. Though it’s sold out now, she spent months encouraging people to sign up through her posts online. This year will be her first time running the MCM marathon, though she’s spectated before and the energy was like nothing else.

“I thrive off of race day energy,” she says. “I love running and take it seriously, but it’s also about the fun of it and doing it with other people. So having a lot of people in my DC community running with me makes me so happy.”

Due to the race’s overwhelming popularity, early bird registrations for next year’s event opens January 1, 2024, with military members being able to register December 31. The Marine Corps Historic Half takes place May 19, 2024, and is part of the MCM series.

(09/30/2023) ⚡AMPby Outside Online

Three ways runners get better with age

Recent performances in distance running have demonstrated the ability of athletes to break records well into their late 30s and 40s, particularly in longer distances. Sports scientist Sian Allen, a research manager for the Lululemon innovation team, recently shared three ways athletes are able to improve their performances as they age, and her observations hold true for both professionals and regular runners hoping to continue to smash PBs.

1.- Years of training wisdom

A recent study published in the Annual Review of Psychology points out that our crystallized intelligence–the stored knowledge that we accumulate over the years–doesn’t peak until we are in our 60s. Years of learning carry over to improved running performance.

In a recent article in The Irish Times, Swiss researcher and ultrarunner Dr. Beat Knechtle explains that the boost in older endurance athletes’ performances has a lot to do with experience and mindset. “Experience, starting slow, going slow, focusing on the aim … younger athletes always tend to want to achieve a place, a podium, a time,” he said. “The older ones like me say the first aim is to finish, and finishing means preparing.”

2.- Improved physical awareness

As we age, we become more familiar with our bodies and are capable of understanding the feedback signals our brain is receiving, a process referred to as interoception. Anyone who has competed over years or decades can probably attest that they have become far better at “reading their body” over time.

A recent study also pointed out that athletes, from sprinters to endurance athletes, are better at this skill than non-athletes. The wide range of runners were more confident in their interoceptive abilities and could hone these over time.

3.- Better pacing skills

Just as years of experience can help runners learn to troubleshoot and adjust on race day, they also learn how to pace themselves effectively. Research has shown that older marathon runners are more likely to use steady-state or negative pacing strategies, rather than trying to put “time in the bank” in the first half of a marathon.

With more learned control and a greater willingness to be conservative in the early stages of a race, older runners are better able to plan and execute speedier race performances.

(09/28/2023) ⚡AMPby Keeley Milne

Viktoria Brown smashes her own 6-day record

Whitby, Ont.’s Viktoria Brown has conquered the multi-day racing scene, and she just keeps getting better. Brown ran a whopping 747 kilometers at the EMU 6-day Race in Hungary, besting her previous Canadian 6-day record of 736 km. Runners competed on an 898.88 meter-long certified road loop that was 100 per cent asphalt.

Brown is well-known for her many multi-day records, and for recently competing at Badwater 135, the scorching ultra in Death Valley, Calif., where she finished fourth.

She holds the 48h Canadian record (363 km), and the 72-hour Canadian record (471 km), and was the owner of the 72h WR, recently bested by Danish athlete Stine Rex. She entered EMU having trained minimally, and became ill with salmonella poisoning partway through the event.”My goal at this race was to hit 800 kilometers,” Brown told Canadian Running.

“Only three women have ever done that, and I believe that without the salmonella poisoning, I would have hit it,” she said. “I only ran 56 km on day five, while I ran 110+ km on all other days, including 151 km on day six.”

Ultras are often a test in troubleshooting, and this is only magnified by multi-day racing.”Vomiting started at noon on Monday (the start of day five) and went on all day until I went down for sleep around 10 pm,” Brown said. “I got up at 3:30 am, was back on the course at 4 a.m., and ran straight until the race ended, 32 hours later.” Brown says she was extremely lucky to have a medical doctor on her crew, whom she credits with bringing her back from illness.

To combat the salmonella, Brown slept for six and a half hours to reset her body.”I wasn’t throwing up anymore, although my body was completely empty and I still had diarrhea,” she said. “But that meant that five-10 per cent of the intake was absorbed, so we could slowly start to refuel.” Brown had to walk until late afternoon on Tuesday, both because her body was recovering and due to intense heat during the daytime.”By late afternoon I was able to start jogging, then running, and then even running relatively fast by the end.”

Brown says she felt she was unable to train for this race, but her excellent base fitness proved to be enough. “After the 48h World Championship in August (that I won) I had some slight pain under my right knee, so I could only do minimal training,” she explains.”By the time the injury healed, I caught a cold, so then I couldn’t train at all. Maybe being more rested for this race helped more than the training would have,” said Brown.

Post-race, Brown says it’s hard to catch up on sleep, but she has a surprising lack of soreness and no blisters.”My body is in great shape, but my mind will need some serious recovery,” the runner said. “These races are extremely demanding mentally.” Brown will compete next at the Kona Ironman World Championship in Hawaii in October, and later at the 24-hour world championship with Team Canada in Taiwan.

(09/22/2023) ⚡AMPby Keeley Milne

Beyond Marathons: Uncovering the World’s Most Scenic Trail Runs

For experienced trail runners searching for their next trail marathon and newcomers to the sport who are researching trail run events for the first time, we have compiled a list of the top destinations for trail running

These races are renowned and provide breathtaking scenery, making them a must-have addition to your race calendar. Our selection deliberately combines well-known races with hidden gems you may not be familiar with. These hidden gems offer a unique sense of adventure and excitement, going beyond the usual races that everyone knows about.

WaitomoTrailRun,New Zealand

The Waitomo Trail Run, a one-of-a-kind event located in New Zealand's North Island, offers a unique and unforgettable experience. Now in its third year, this trail run has quickly become the largest of its kind in the country.

Participants find themselves immersed in the stunning landscape of Hobbit country, with its picturesque rolling hills adorned with vibrant green grass. As you traverse the course, you'll also have the opportunity to explore captivating limestone caves illuminated by the enchanting glow of glowworms.

It's important to note that littering is strongly discouraged, as there is a peculiar consequence for those who discard their energy gel wrappers. Participants may find themselves tasked with clearing gorse from the hills above Te Anga road while sporting nothing but jandals, shorts, and a singlet. However, they will be rewarded with warm cordial for sustenance and have the opportunity to partake in the wet Perendales crutching experience for several days.

Lavaredo Ultra Trail, Northern Italy

Located in central-eastern Italy, the Dolomites showcase breathtaking rock formations that are truly remarkable. The Lavaredo Ultra Trail takes place within this distinctive lunar landscape, ranking as one of the most exquisite races worldwide. Only by participating in this event will you truly grasp why this place holds a magical allure, much like Venice.

Even the world’s best sportsbooks that cover marathon odds would struggle to conjure up the necessary prices due to the distraction this location's beauty presents.

As part of the UTWT competitions, the race unfolds amidst the majestic Dolomite mountains, running alongside the picturesque Misurina Lake and at the base of the renowned Tre Cime of Lavaredo, a symbol of global mountaineering. The beauty of this location stems from the striking contrast between the lush alpine forests, the rugged gray rocks, and the vivid blue skies and lakes.

While the race offers fast sections, it is also technically demanding, requiring attentiveness to the rocky terrain and tree roots along the course. This is an event that should not be missed, although securing a spot through the registration draw is essential. Be sure to mark it on your agenda, as the experience is bound to be unforgettable!

Vallee Du Trail, Chamonix, France

Chamonix, renowned as the valley for trail running and the official host of the prestigious Ultra Trail du Mont Blanc, embodies the essence of the trail running community. Chamonix is a paradise for trail runners, as it offers a remarkable collection of 18 well-marked running routes that meander through picturesque mountain trails, enchanting forests, and serene alpine meadows, all while providing breathtaking panoramas of majestic mountains and icy peaks.

What sets Chamonix apart is its inclusive and hospitable trail running community, which caters to elite athletes and anyone who possesses a deep affection for the mountains and the exhilarating outdoors.

MatterhorUltraks, Switzerland

The Matterhorn, the ultimate representation of a picturesque alpine setting and alpine skiing, takes center stage for trail running during the summer. In Switzerland's Matterhorn Ultraks event, this majestic peak is visible from all directions and can be encircled through various routes ranging from 16 to 46 km.

One particularly remarkable feature is the K30 trail, which spans 31.5 km and includes a thrilling highlight: a suspension bridge crossing the glacier gorge. Zermatt serves as the starting point for all the trails.

By the way, "Ultraks" represents a series of trail running events at the most awe-inspiring mountain peaks across Europe.

X-TerraTrailRunWorld Championship, Hawaii

The X-Terra Trail Run World Championship is held at Kualoa Ranch, located in Hawaii. This ranch is famously known as Jurassic Valley, as it served as the backdrop for the iconic dinosaur movies.

The trails used in the X-Terra Trail Run World Championship are typically inaccessible to the general public. Therefore, this race offers a unique opportunity for runners to explore and appreciate the natural beauty of this area.

The terrain itself is diverse and awe-inspiring. Participants will have the chance to run alongside cliffs and white sand beaches and navigate their way through dense rainforests.

No prior qualifications are required to participate in the 21-kilometer championship course. This event also includes a 10-kilometer race, a five-kilometer race, and an "adventure walk," making it accessible to runners of all ages and skill levels, from beginners to elite athletes.

(09/22/2023) ⚡AMPAmanda Nelson breaks Canadian 24-hour record

Ultrarunner Amanda Nelson broke the Canadian women’s 24-hour record at That Dam Hill in London, Ont., over the weekend, running an unofficial distance of 248.8 kilometers and picking up her fourth national ultramarathon record.

Although Nelson, who hails from Woodstock, Ont., told Canadian Running on Monday that the exact distance likely won’t be made official for a couple of weeks, she broke the 238.261-km record held by Bernadette Benson by at least 10 km.

“I had lots of highs and lows—more highs than lows—but there were times where I was like, ‘Why am I doing this?’” she said of her weekend effort, her third attempt at breaking the Canadian 24-hour record.

She said while her path to achieving the 24-hour record hasn’t always been smooth, an uneven surface is exactly what was needed to finally accomplish this feat.

Nelson said her two previous, unsuccessful shots at the record were both attempted on the track. Although running on a flat surface would seem to take less of a toll on the body, the monotony of running laps on a track was too mentally draining.

“Mentally, just doing the track, it’s not for me,” said Nelson. “That Dam Hill isn’t a track—it’s a 2.25-km loop on pavement with hills. Although it’s hard running on pavement for that long, there’s more variety to the surroundings at That Dam Hill. I need the hills and the downhills and variety. They help a lot, mentally. I knew I had to do a course that wasn’t on a track if I was going to take another try at breaking the record.”

Nelson said positive self-talk was also key to staying on track during her most recent shot at the record. “When I’m going through a low, I make sure to remind myself that I can keep going, that I am strong enough and this bad feeling is going to pass.”

She said she felt “amazing” in the final moments of her run, and that the end of her record-breaking race was made even more special when Hanna Nelson, her 10-year-old daughter, joined her for the last partial loop until the clock hit 24 hours.

“It was great, but it’s crazy how the second you finish, you’re done. Everything just kicks in and you’re like, ‘I couldn’t even run one more step.’”

In addition to her latest record, the 34-year-old holds the women’s 12-hour Canadian record (135.072 km) and the 100-mile Canadian record (14:45:51). In May, she broke her Canadian women’s backyard ultra record by running 375.51 km over 56 hours at the Race of Champions-Backyard Masters in Rettert, Germany.

That performance in Germany helped qualify Nelson for Big Dog’s Backyard Ultra Individual World Championships in Short Creek, Tenn., which begins Oct. 21. She is one of only three Canadians who have qualified for the race (Ihors Verys and Eric Deshaies have also punched their tickets), and one of only four female qualifiers among 75 runners representing 38 countries.

However, there’s a chance the race may be over for her before it begins—the cost of making the return trip to Tennessee could end up being too prohibitive for Nelson.

(09/19/2023) ⚡AMPby Paul Baswick

So You Missed Your Splits or Lost Your Race – Now What?

How failing in training and racing can make you a stronger runner

It’s Tuesday. No, it’s not only Tuesday. It’s critical velocity day. My coach has assigned me two warm-up miles and six 600 meters in 3:13-3:21 intervals, with a 90 second jog between each one. I head out to smash the workout. I’m confident. I’m excited. Then, I start. It’s blistering hot. Sweat is dragging all my face sunscreen down my forehead into my eyes. Water sloshes in my stomach. I’m so thirsty but I can’t drink anymore or I’ll puke. I start to slow. Miss my paces. What is happening? My head spins and I get this horrible gut-wrenching feeling as I pull through the last interval. My coach is going to be disappointed. My Strava record is going to be humiliating. Because I absolutely, undoubtedly failed this run.

Thinking of yourself or your run as a failure can be debilitating and keep you down for days. For a while, I thought I needed to stifle this feeling. But as it turns out, I should be making nice with failure rather than fighting it.