Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #Usain Bolt

Today's Running News

Sorato Shimizu Sprints Into History: 16-Year-Old Clocks 10.00s to Set World Age-16 Record

Japanese sprinting phenom Sorato Shimizu has etched his name into the history books with a jaw-dropping performance at the Japanese Inter-School Championships—blazing to a 10.00-secondfinish in the 100 meters. At just 16 years old, Shimizu now owns the fastest time ever recorded by a 16-year-old, breaking the previous world best of 10.09 held by Thailand’s Puripol Boonson.

The time, achieved with a legal wind assistance of +1.7 m/s, marks a stunning personal best for the young star and sets a new World Age-16 Record. The stadium erupted as Shimizu crossed the line and confirmed the time on the scoreboard, with fans and fellow athletes celebrating what could be the beginning of a generational sprinting career.

A Historic Milestone in Sprinting

Running 10.00 seconds in the 100m is a feat few athletes achieve—even at the elite senior level. That a 16-year-old high school student has accomplished it underscores Shimizu’s immense talent and the growing strength of sprinting development in Japan.

Shimizu’s run wasn’t just about raw speed—it showcased poise, explosive acceleration, and flawless execution from start to finish. His reaction time, drive phase, and transition into top-end speed were that of a seasoned pro. It was a performance that stunned not only spectators in Japan but sprint fans across the globe.

Breaking Boonson’s Mark

Before Shimizu’s 10.00, the world age-16 best was 10.09, set by Thailand’s Puripol Boonson in 2022. Boonson has since gone on to become one of Asia’s fastest men—and Shimizu is now poised to follow a similar path, if not exceed it.

With this performance, Shimizu moves into a rarefied tier of sprinting prospects, joining a list that includes the likes of Trayvon Bromell, Erriyon Knighton, and Usain Bolt—who all produced world-class times as teenagers.

The New Face of Japanese Sprinting

Japan has long produced disciplined and technically sound sprinters, with athletes like Abdul Hakim Sani Brown, Yoshihide Kiryu, and Ryota Yamagata helping bring Japanese sprinting into the global spotlight. Sorato Shimizu now emerges as the new face of that legacy—and possibly, its next global champion.

With the Paris Olympics behind us and eyes already shifting to Los Angeles 2028, Shimizu’s name will surely be one to watch on the international scene.

What’s Next for Sorato Shimizu?

While this 10.00 clocking will take some time to fully digest, one thing is clear: Sorato Shimizu is just getting started. Still in high school, his future includes national championships, international junior meets, and, if his progression continues, a spot on Japan’s senior relay and individual sprint squads.

His breakthrough opens new possibilities for Japanese sprinting, showcasing that sub-10 is not a dream for the future—it’s a reality for the present.

Final Word

In an era where sprinting records are harder than ever to break, Sorato Shimizu just redefined what’s possible at age 16. His 10.00-second dash not only resets the record books—it ignites excitement for the future of global sprinting.

This isn’t just a time. It’s a statement.

Sorato Shimizu has arrived.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Jamaica Takes Over the 100m in 2025 — But Don’t Count Team USA Out Just Yet

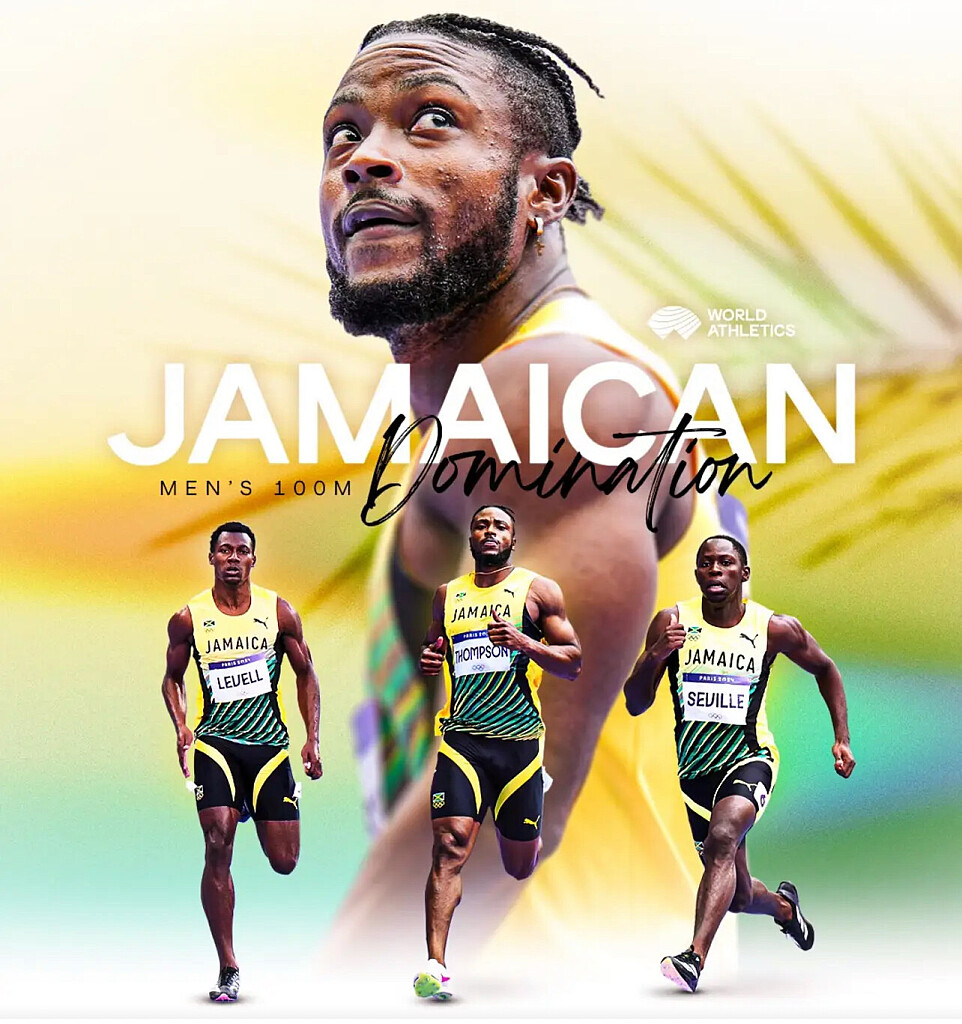

Jamaica is back—and in a big way. With just weeks until the World Athletics Championships Tokyo 2025, the top three times in the men’s 100 meters all belong to Jamaican sprinters:

Kishane Thompson – 9.75

Bryan Levell – 9.82

Oblique Seville – 9.83

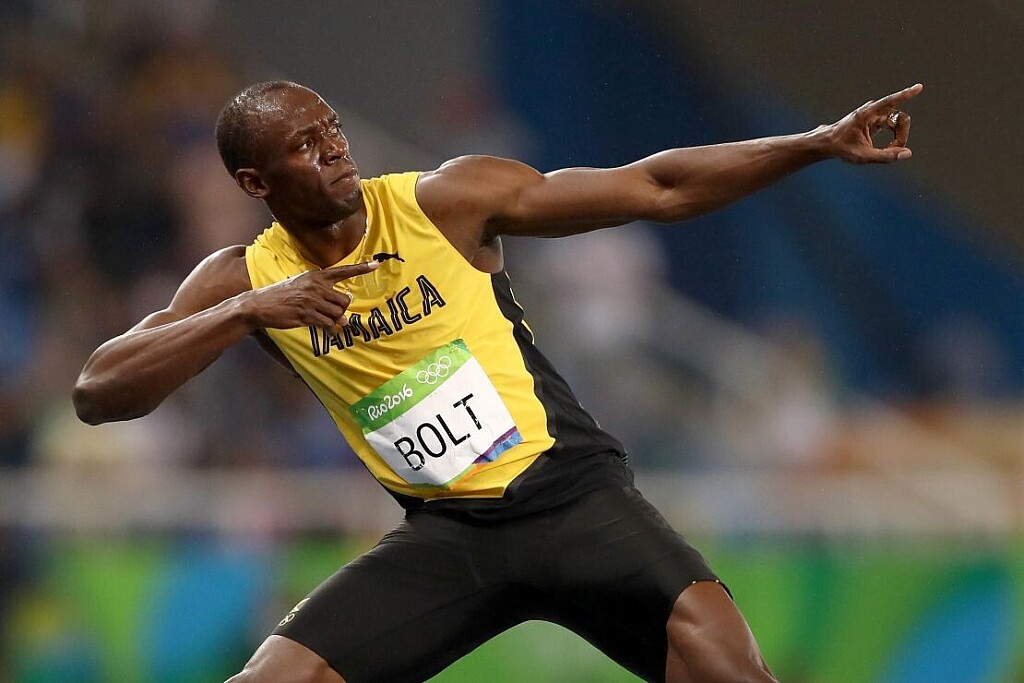

It’s a stunning sweep that echoes the glory days of Usain Bolt, Asafa Powell, and Yohan Blake. Once again, Jamaica is asserting sprinting dominance on the global stage.

But the Americans aren’t backing down.

The U.S. Response

Christian Coleman, the 2019 World Champion and indoor world record holder, remains a serious contender. While he hasn’t cracked the 9.80 mark this season, his raw speed and big-meet experience can’t be ignored.

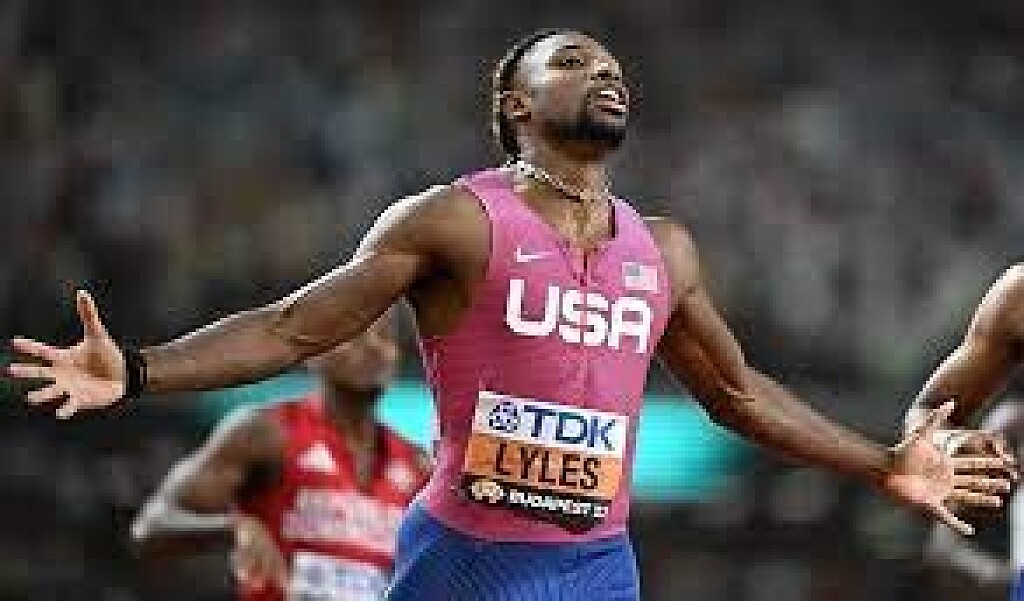

Then there’s Noah Lyles, the reigning 100m world champion from 2023. Lyles opened 2025 focused more on the 200m and Olympic buildup, but he’s expected to peak at the right time. He holds a personal best of 9.83, and if he gets the start right, he can be deadly in the final 30 meters.

Fred Kerley and Trayvon Bromell are also in the mix, both capable of sub-9.90 performances when healthy and locked in. Their challenge now is to stay consistent as the season progresses.

The Rivalry is Back

Tokyo 2025 could deliver one of the most thrilling 100-meter finals in recent memory:

• Three Jamaicans in peak form.

• Four Americans with world-class credentials.

• African stars like Omanyala and Tebogo chasing their first world title.

It’s a global showdown that brings back the tension and electricity of the Bolt-Gatlin era—only this time, the Jamaicans aren’t chasing; they’re being chased.

As World Athletics put it: “JAMAICA TO THE WORLD” — but America might have something to say about that.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

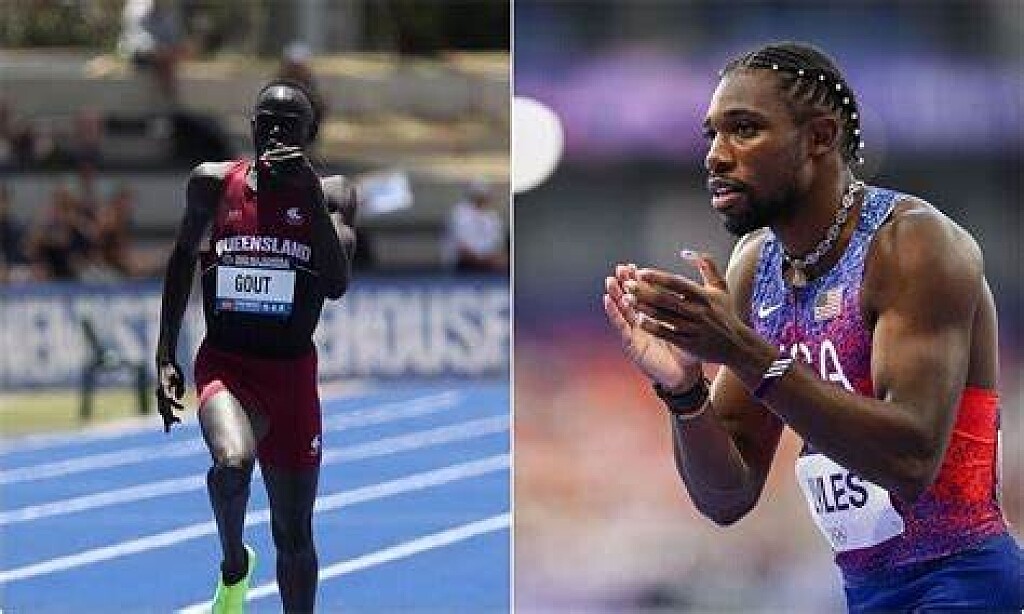

Australia’s teenage sprint sensation, Gout Gout, is gearing up for his biggest stage yet — the 2026 Commonwealth Games in Glasgow.

At just 17 years old, Gout Gout has already rewritten the record books. The Queensland-based sprinter, born in December 2007 to South Sudanese parents, is widely regarded as one of the most exciting young talents in global athletics. His rapid rise has drawn comparisons to legends like Usain Bolt — and for good reason.

Gout currently holds the Oceanian 200m record with a time of 20.02 seconds, set at the Golden Spike meet in Ostrava earlier this year. He also clocked 10.17 in the 100m to win the Australian U-18 title and later dominated the U-20 division. His combination of top-end speed, graceful stride, and fierce competitive drive has made him a must-watch on the world stage.

Now, the teen phenom is set to represent Australia at the 2026 Commonwealth Games, scheduled for July 23 to August 2 in Glasgow, Scotland. He is expected to compete in the 100m, while his entry in the 200m remains under consideration due to scheduling conflicts with the World Junior Championships, which will take place shortly after in Eugene, Oregon.

Gout’s Path to Stardom

Gout’s emergence as a global sprint force has been nothing short of remarkable. Raised in Ipswich, Queensland, he was introduced to athletics at a young age and quickly caught the attention of Australia’s elite coaches. Under the guidance of Diane Sheppard, Gout has developed into a technically polished athlete with a mature race strategy far beyond his years.

His silver medal at the 2024 World U20 Championships in the 200m confirmed what many already believed — Gout Gout isn’t just Australia’s future; he’s already one of its best.

Sheppard has praised his dedication, humility, and focus, noting:

“With Gout, it’s not just talent — it’s mindset. He’s willing to do the work and stay grounded.”

Glasgow 2026: A Games Reimagined

The 2026 Commonwealth Games will mark a return to Glasgow, which last hosted the event in 2014. Following Victoria’s withdrawal as host due to financial concerns, Glasgow stepped up with a streamlined, cost-efficient plan built on existing infrastructure.

The Games will feature:

• 10 core sports and 47 para-sport events

• Key venues including Scotstoun Stadium (track and field), Tollcross International Swimming Centre, and the Sir Chris Hoy Velodrome

• A strong focus on sustainability and legacy, with no new athletes’ village planned

Mascot “Finnie the Unicorn”, named after the Finnieston Crane and created by local students, has already captured hearts with its fun, distinctly Scottish vibe.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

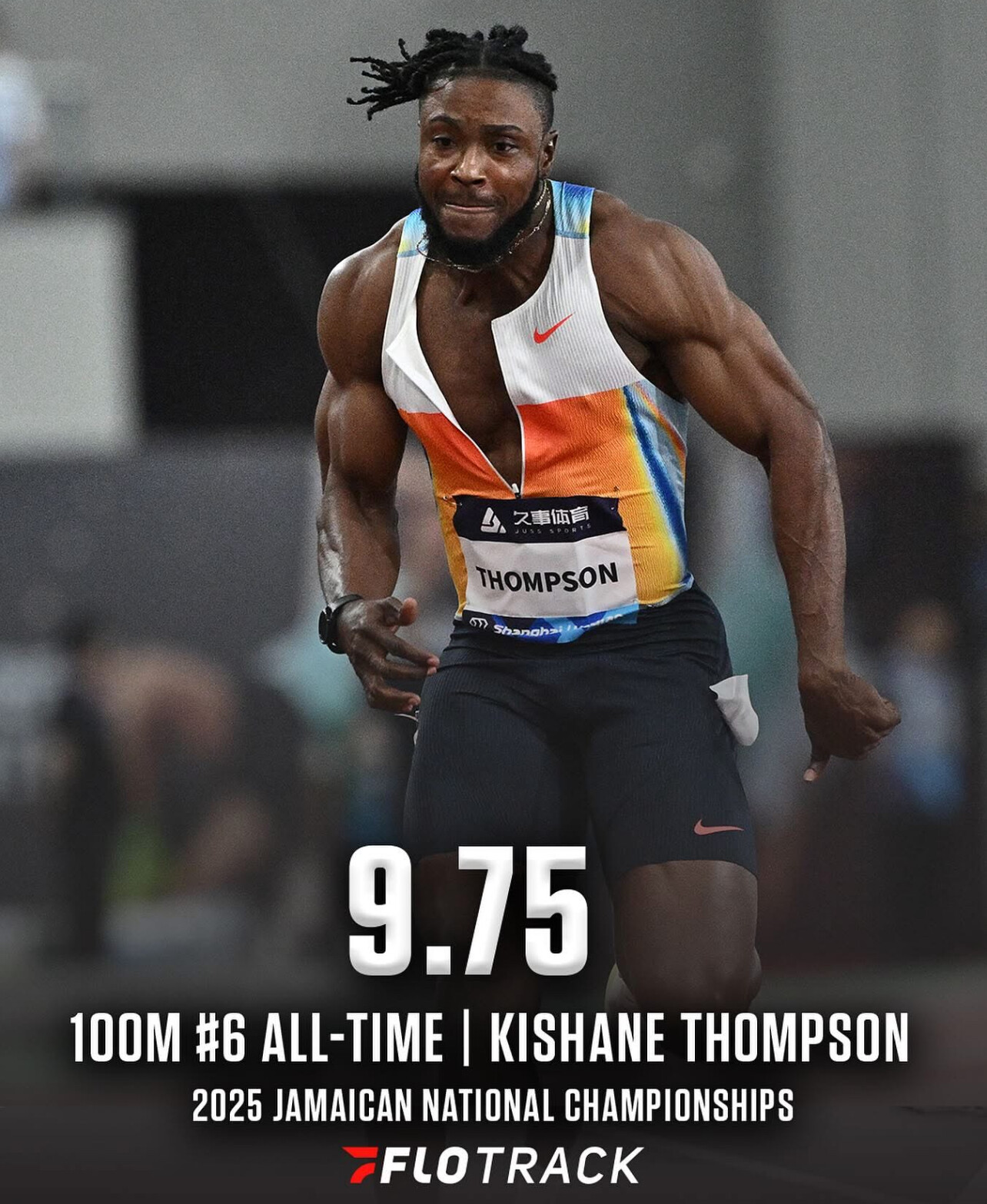

Kishane Thompson Runs 9.75 to Become Sixth Fastest Man in History

Jamaican sprinting just added another chapter to its storied legacy. On June 27, 2025, Kishane Thompson stunned the track world with a blazing 9.75-second performance in the men’s 100m final at the 2025 Jamaican National Championships, becoming the sixth-fastest man of all time.

Running in near-perfect conditions, Thompson powered down the track with a performance that firmly cements him among the global elite. Only five men—Usain Bolt, Tyson Gay, Yohan Blake, Asafa Powell, and Justin Gatlin—have ever run faster.

This wasn’t just a personal best. It was a breakout moment that may redefine Jamaica’s sprint hierarchy heading into the Paris Olympics later this summer. Thompson, who has quietly been building momentum over the past two seasons, now finds himself at the center of global attention.

“I knew I had this in me,” Thompson told reporters after the race. “Training has been going well, and I came here ready to execute. To do it on this stage, in front of my home crowd, is special.”

The performance lights up what’s already been a thrilling sprint season, with several athletes dropping times under 9.90. But 9.75? That’s a mark that sends shockwaves around the world.

With his explosive start and powerful closing stride, Thompson showed a blend of raw speed and race maturity well beyond his years. The moment also comes at a critical time for Jamaican sprinting, as the nation looks to find its next global icon following the retirement of Usain Bolt.

If Friday’s race was any indication, Kishane Thompson may be that next name.

Top 100m Performances All-Time

1. Usain Bolt – 9.58

2. Tyson Gay – 9.69

3. Yohan Blake – 9.69

4. Asafa Powell – 9.72

5. Justin Gatlin – 9.74

6. Kishane Thompson – 9.75

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

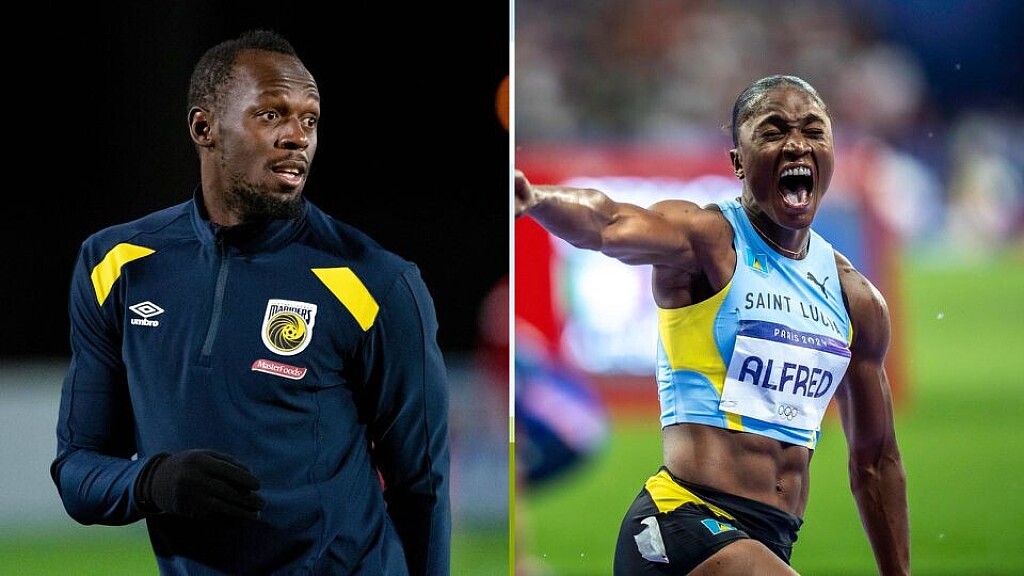

Fake News Creeps Into Athletics World with False Usain Bolt Claim

In a digital age overflowing with misinformation, fake news has found its way into nearly every corner of public life—and now it’s creeping into the world of athletics. Over the weekend, a Facebook post from a fan page titled Usain Bolt Fans falsely claimed that the legendary sprinter was stepping down as Jamaica’s ambassador.

The post, filled with dramatic language and linked to a questionable site (dailypressnewz.com), quickly gained traction—racking up hundreds of reactions, comments, and shares. But there’s one problem: it’s not true.

There has been no official confirmation from Usain Bolt, the Jamaican government, or any reputable media outlet. This appears to be a blatant fabrication—another example of how social media platforms, especially Facebook, are failing to properly police misinformation.

“Why would anyone want to spread such lies?” That’s the troubling question. Perhaps it’s about driving traffic to ad-heavy websites. Or it could be more sinister—part of a broader trend of undermining public trust in institutions and public figures. Either way, it’s deeply concerning.

Usain Bolt isn’t just an Olympic icon—he’s a symbol of excellence, integrity, and global unity through sport. Misusing his name to generate clicks is not only dishonest, it’s harmful.

At My Best Runs, we believe in truth, accuracy, and the integrity of the running community. If false headlines are allowed to spread unchecked, they can damage reputations and distort public perception—especially among younger athletes who look up to role models like Bolt.

This incident is a wake-up call. If fake news can so easily invade the running world, no part of our sport is safe from digital misinformation.

Let’s stay vigilant. Let’s ask questions. And let’s continue celebrating the real stories that make our sport so powerful.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Who’s the Fastest Man in the World Right Now?

Sprint Showdown 2025: Lyles, Knighton, and Tebogo Ignite a New Era of Speed on the Diamond League Stage

The 2025 Diamond League season is heating up fast, and the men’s sprints are once again the center of attention. Three names are defining the early action: Noah Lyles, Erriyon Knighton, and Letsile Tebogo—each with the potential to end the season as the world’s fastest man.

Noah Lyles: The Champion with a Target on His Back

Reigning Olympic and World Champion Noah Lyles is the man to beat. Though he hasn’t yet raced on the Diamond League circuit this year, his resume speaks volumes. He clocked 9.83 in the 100m and 19.47 in the 200m during the 2024 season and claimed double gold in Paris. All eyes are on when—and where—he’ll make his 2025 Diamond League debut. With a long-standing goal of breaking Usain Bolt’s 200m world record, Lyles remains the top contender.

Erriyon Knighton: Poised to Pounce

Still just 21 years old, Erriyon Knighton hasn’t raced yet in 2025, but anticipation is building. The American phenom owns a personal best of 19.49 in the 200m, set in 2022 as a teenager. After earning Olympic silver behind Lyles in Paris, Knighton is expected to return to the track soon and challenge for dominance in both the 100m and 200m this summer.

Leslie Tebogo: The Early Season Leader

Botswana’s Letsile Tebogo, the reigning Olympic 200m silver medalist and one of Africa’s brightest young stars, is already making headlines in 2025. He opened his season with a 10.20 in Xiamen and followed that with a 10.03 in Shanghai—finishing third in both Diamond League meets. Tebogo is scheduled to run his primary event, the 200m, at the Doha Diamond League on May 16, which could be a statement race as he builds toward the World Championships in Tokyo later this year.

What’s Next: A Collision Course

While all three athletes are on different timelines this season, the Diamond League is setting the stage for dramatic head-to-head clashes. Lyles and Knighton have yet to toe the line, while Tebogo is already building momentum. Their inevitable meeting—possibly at the Prefontaine Classic or in Europe this summer—could define the sprinting landscape in 2025.

The sprint wars are officially on. The only question left: Who will own the title of the world’s fastest man by season’s end?

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Gout Gout Clocks Back-to-Back 9.99s at Age 17

Dipping under the 10-second barrier in the 100 meters is a major milestone for any sprinter. For 17-year-old Australian sensation Gout Gout, doing it once wasn’t enough.

At the Australian Athletics Championships on Thursday, Gout stunned the crowd by running 9.99 seconds in his 100m heat—powered by a +3.4 m/s tailwind. Less than two hours later, he backed it up with an identical 9.99 in the final, this time with a +2.6 m/s wind. While the wind speeds mean neither time is eligible for record purposes, the message was clear: Gout Gout has arrived.

Including wind-aided marks, his performance ranks as the second-fastest 100m in the world this year, tying South Africa’s Bayanda Walaza, who ran 9.99 in March. More importantly, it obliterates the Australian and Oceanian U20 record of 10.15—but again, due to the excessive wind, the record books won’t recognize it.

Wind readings over +2.0 m/s are deemed illegal in sprinting, as they can artificially enhance performance—typically by about 0.1 seconds in the 100m. For Gout, this wasn’t the first time nature interfered with history. Back in December, as a U18 athlete, he clocked 10.04 with a +3.4 m/s wind. His current official personal best remains 10.17 seconds.

Still, the young sprinter isn’t letting wind readings define him.

“Sub-10 is something every sprinter hopes for,” Gout said. “To gain that sub-10 definitely boosts my confidence, especially for my main event—the 200m.”

And that’s not just talk. Gout broke the Australian 200m record in December at just 16 years old, clocking a blistering 20.04 seconds. With that time, he announced himself as a true global prospect.

The Australian 100m record of 9.93, set by Patrick Johnson in 2003, remains untouched—for now. But if Gout Gout keeps this trajectory, and gets the wind on his side, he may not only rewrite national records—he might just chase global ones.

Is Gout Gout the Next Usain Bolt?

While it’s tempting to draw comparisons between Gout Gout and Usain Bolt, especially given their early successes and similar event specializations, it’s important to recognize that Gout is carving his own path. Notably, he broke Bolt’s under-18 200m record by running 20.04 seconds, surpassing Bolt’s 20.13-second mark at the same age .

Usain Bolt’s world records stand at 9.58 seconds for the 100m and 19.19 seconds for the 200m, both set in 2009. Gout’s current legal personal bests are 10.17 seconds for the 100m and 20.04 seconds for the 200m . While there’s still a gap between their times, Gout’s trajectory suggests he could become a formidable competitor on the world stage

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Noah Lyles’ Paris 100m Victory: Implications of New Timing Rules on Sprint Records

In the electrifying atmosphere of the 2024 Paris Olympics, American sprinter Noah Lyles clinched the gold medal in the men’s 100m final, clocking a personal best of 9.784 seconds. This razor-thin victory over Jamaica’s Kishane Thompson, decided by just five-thousandths of a second, marked one of the closest finishes in Olympic 100m history.

As the athletics world celebrates Lyles’ achievement, attention turns to forthcoming changes in timing regulations set by World Athletics. Starting in 2025, a significant amendment will alter how sprint times are recorded: the race clock will commence only when an athlete initiates movement, effectively eliminating the inclusion of reaction times in official results.

Under this new system, Lyles’ Paris performance would be recalculated to exclude his reaction time, potentially resulting in a faster recorded finish. This adjustment not only redefines personal bests but also brings Usain Bolt’s longstanding world record of 9.58 seconds into closer contention. The recalibration raises compelling questions about the comparability of sprint times across different eras and the evolving nature of athletic records.

As athletes and enthusiasts alike anticipate the implementation of these changes, the track and field community stands on the cusp of a new chapter—one that may see historical records challenged and the very metrics of speed redefined.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

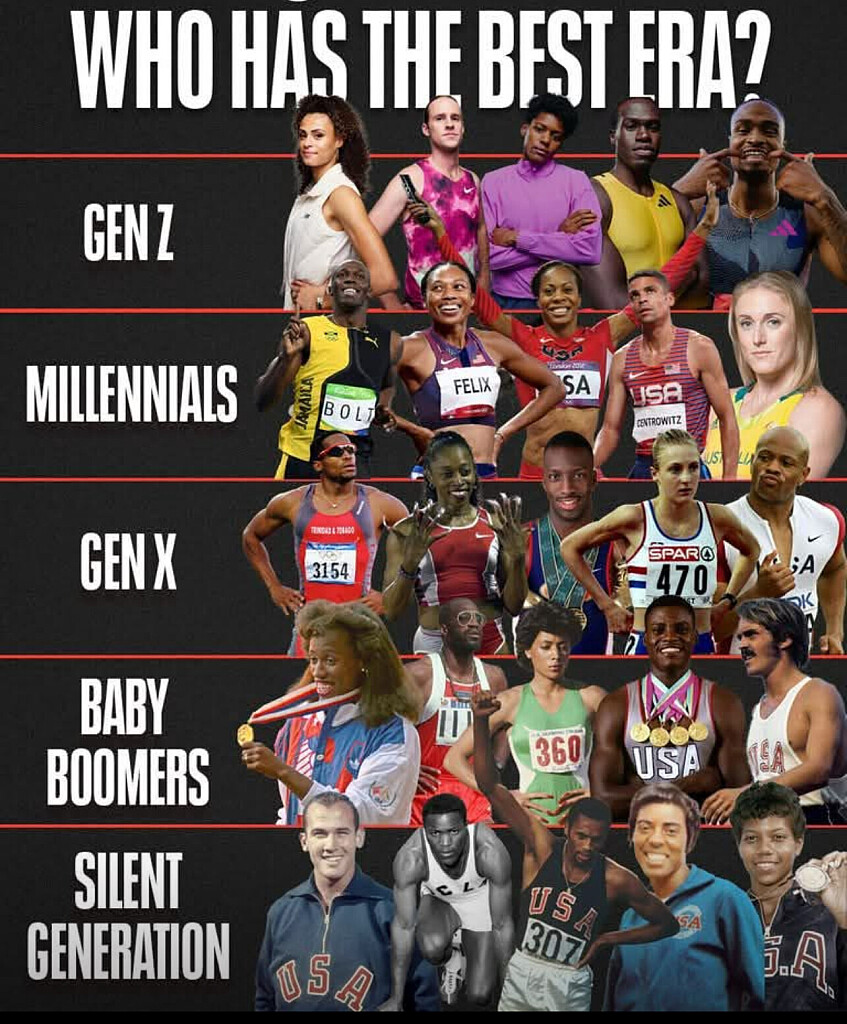

Who Had the Best Era in Track & Field? A Generational Showdown

Track and field has long been the stage for some of the most electrifying athletic performances in history. Each generation has produced legends who have redefined what is possible in sprinting, distance running, and field events. But which era stands above the rest?

From the Silent Generation pioneers to the Gen Z record-breakers, every period has contributed to the evolution of the sport. Let’s break down each era’s greatest stars and their lasting impact on track and field.

Gen Z (Born 1997 - 2012): The Future of Track & Field

The newest generation of elite athletes is already making waves on the world stage. With the benefit of cutting-edge training, nutrition, and recovery techniques, these young stars are smashing records at a rapid pace.

Notable Sprinters & Field Athletes:

• Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone (USA) – 400m hurdles world record holder and Olympic champion

• Mondo Duplantis (Sweden) – Pole vault world record holder

• Erriyon Knighton (USA) – One of the fastest teenagers ever in the 200m

Notable Distance Runners:

• Jakob Ingebrigtsen (Norway) – Olympic 1500m champion, European mile record holder

• Joshua Cheptegei (Uganda) – 5000m and 10,000m world record holder

• Jacob Kiplimo (Uganda) – Half marathon world record holder (57:31)

• Gudaf Tsegay (Ethiopia) – World champion in the 1500m, dominant in middle distances

Gen Z athletes are not only breaking records but also shaping the future of the sport through their influence on social media and global visibility. With their combination of speed, endurance, and access to modern sports science, they may soon surpass all who came before them.

Defining Traits: Explosive, record-breaking, tech-savvy

Millennials (Born 1981 - 1996): The Superstars of the Modern Era

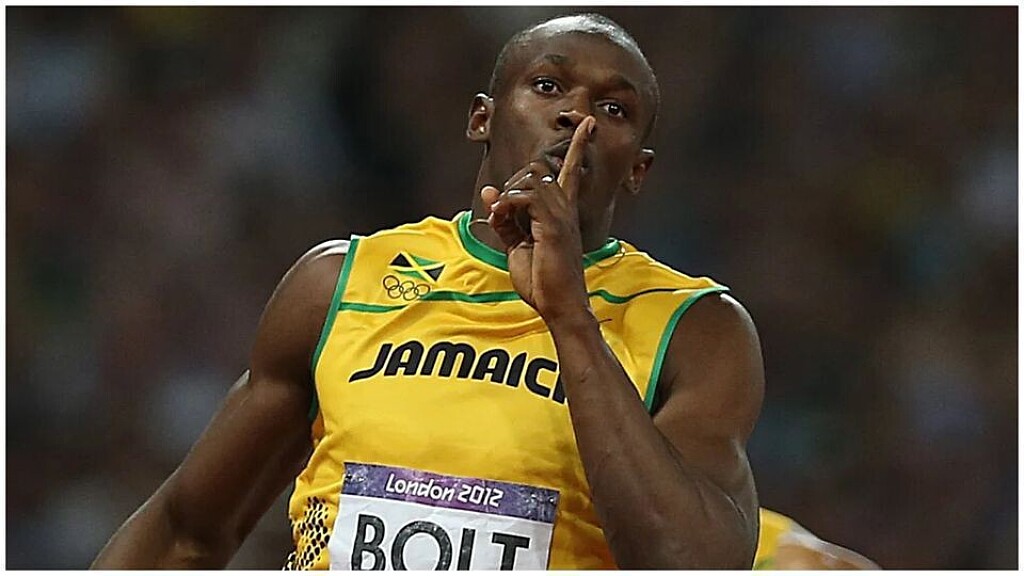

No discussion of dominant track and field generations is complete without mentioning Usain Bolt. The Jamaican sprinting legend captured the world’s attention with his charisma and untouchable world records.

Notable Sprinters:

• Usain Bolt (Jamaica) – Fastest man in history (100m: 9.58, 200m: 19.19)

• Allyson Felix (USA) – Most decorated female Olympian in track history

• Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce (Jamaica) – One of the most dominant sprinters of all time

Notable Distance Runners:

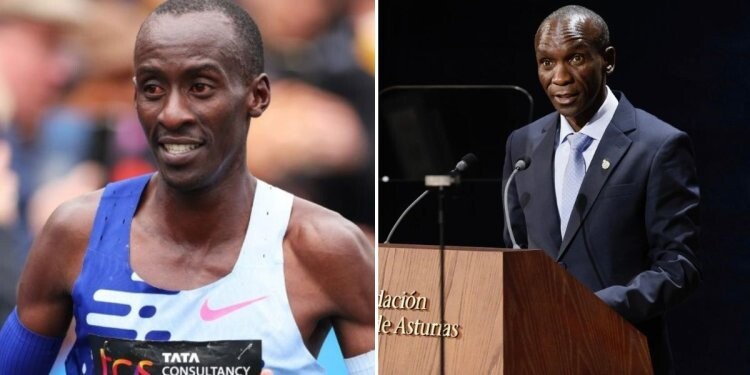

• Eliud Kipchoge (Kenya) – The greatest marathoner of all time, first to break two hours in a marathon

• Mo Farah (UK) – Dominated the 5000m and 10,000m at two Olympic Games

• Genzebe Dibaba (Ethiopia) – 1500m world record holder

• Ruth Chepngetich (Kenya) – First woman to break the 2:10 barrier in the marathon, setting a world record of 2:09:56 at the 2024 Chicago Marathon

Millennials excelled across all track and field disciplines. They ushered in an era of professional distance running dominance, with African runners setting standards in middle and long distances. Meanwhile, Kipchoge’s sub-2-hour marathon attempt was a historic milestone in human endurance.

Defining Traits: Charismatic, dominant, endurance revolutionaries

Gen X (Born 1965 - 1980): The Tough and Versatile Competitors

Gen X athletes were the bridge between the amateur days of track and the fully professional era. They pushed the sport forward with fierce rivalries and new records, while also seeing the globalization of track and field.

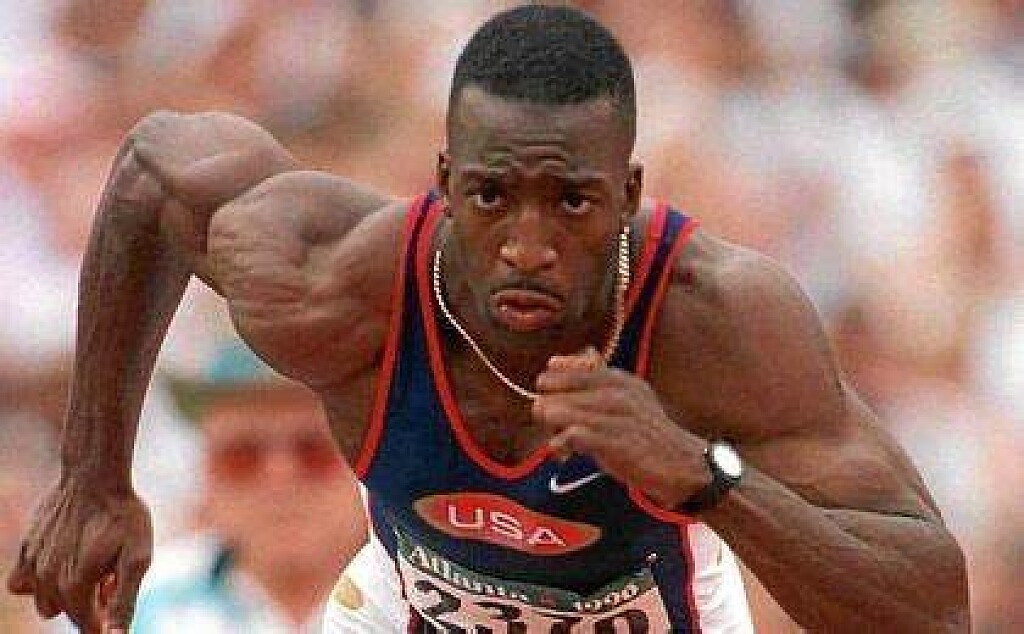

Notable Sprinters:

• Maurice Greene (USA) – Former world record holder in the 100m (9.79)

• Marion Jones (USA) – One of the most dominant sprinters of the late ‘90s

Notable Distance Runners:

• Haile Gebrselassie (Ethiopia) – Olympic and world champion, former marathon world record holder

• Paul Tergat (Kenya) – Pioneered marathon running dominance for Kenya

• Tegla Loroupe (Kenya) – First African woman to hold the marathon world record

This era marked a golden age for distance running, with Gebrselassie and Tergat setting the stage for the marathon revolution that would come in the next generation. With increased sponsorships, the road racing circuit became more competitive, and Kenyan and Ethiopian dominance solidified.

Defining Traits: Tough, globalized, long-distance pioneers

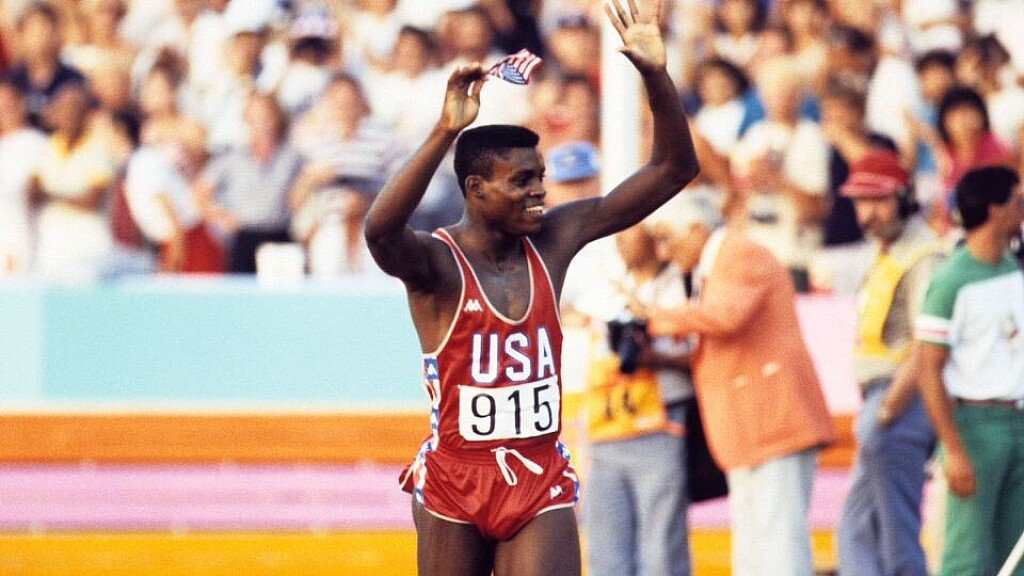

Baby Boomers (Born 1946 - 1964): The Golden Age of Track & Field

The Baby Boomers took track and field into the modern Olympic era, producing some of the most iconic figures in the sport’s history.

Notable Sprinters:

• Carl Lewis (USA) – Nine-time Olympic gold medalist across sprints and long jump

• Florence Griffith-Joyner (USA) – 100m (10.49) and 200m (21.34) world record holder

Notable Distance Runners:

• Sebastian Coe (UK) – 800m and 1500m Olympic champion, middle-distance legend

• Steve Prefontaine (USA) – One of the most influential distance runners in history

• Miruts Yifter (Ethiopia) – 5000m and 10,000m Olympic champion

This era brought middle and long-distance running into the mainstream, with rivalries like Coe vs. Ovett and Prefontaine vs. the world captivating fans. The Baby Boomers were the first generation of professional-level training and saw athletes truly dedicated to their craft year-round.

Defining Traits: Bold, revolutionary, multi-talented

Silent Generation (Born 1928 - 1945): The Pioneers of Kenya’s Dominance

This generation laid the foundation for modern track and field, producing legends whose influence still resonates today.

Notable Distance Runners:

• Kip Keino (Kenya) – The pioneer of Kenya’s dominance in distance running, winning Olympic gold in the 1500m (1968) and 3000m steeplechase (1972)

• Emil Zátopek (Czechoslovakia) – Triple gold in 5000m, 10,000m, and marathon at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics

• Paavo Nurmi (Finland) – Nine-time Olympic gold medalist in long-distance events

Kip Keino’s triumph over Jim Ryun in the 1500m final at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics is considered one of the greatest upsets in Olympic history. Competing at high altitude, Keino used a fast early pace to break Ryun, ushering in an era of Kenyan middle-distance dominance that continues today.

Defining Traits: Groundbreaking, resilient, visionary

Which Generation Had the Greatest Impact?

Each generation of track and field athletes has contributed to the sport’s evolution in unique ways:

• Millennials brought global superstardom (Bolt, Felix, Fraser-Pryce, Kipchoge, Chepngetich)

• Gen X athletes were fierce competitors in a rapidly changing sport (Greene, Gebrselassie, Tergat)

• The Baby Boomers set records that still stand today (Carl Lewis, Flo Jo, Coe, Prefontaine)

• The Silent Generation laid the foundation for modern track and field (Owens, Zátopek, Kip Keino)

• Gen Z is already breaking records and shaping the future of the sport (McLaughlin-Levrone, Ingebrigtsen, Cheptegei)

While it’s hard to declare one era the best, one thing is certain: the sport of track and field continues to evolve, with each generation pushing the limits of human performance.

Which generation do you think is the greatest? Let us know in the comments!

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Usain Bolt reveals meal plan that helped him smash 100m world record at 2008 Beijing Olympics

Usain Bolt broke world records in all his three specialties but the 2008 Olympics diet change was the beginning of his dominance on track.

Three-time Olympic 100m champion Usain Bolt has revealed how a change in diet at the 2008 Olympics in Beijing played a crucial role in him setting a world record in his specialty.

The legendry Jamaican sprinter who also managed three Olympic 200m gold titles, was fueled by chicken nuggets because he thought Chinese food tasted odd.

In his autobiography, Faster than Lightning, Bolt wrote: “At first I ate a box of 20 for lunch, then another for dinner. The next day I had two boxes for breakfast, one for lunch and then another couple in the evening. I even grabbed some fries and an apple pie to go with it,” the 11-time world champion told TalkSport.

Bolt estimated he ate 1,000 of McDonald’s chicken nuggets during the Beijing Olympics. It was an even more impressive feat considering he did it with his shoelaces untied! Bolt finished so clear of his competitors that he pumped his chest while crossing the finishing line and had he not done that, a better final time would have been recorded.

The 38-year-old made history a year later when he set another record in the men’s 100m with a time of 9.58 seconds at the 2009 World Championships. He also won two 4x100m relay golds and holds the world record in all three disciplines.

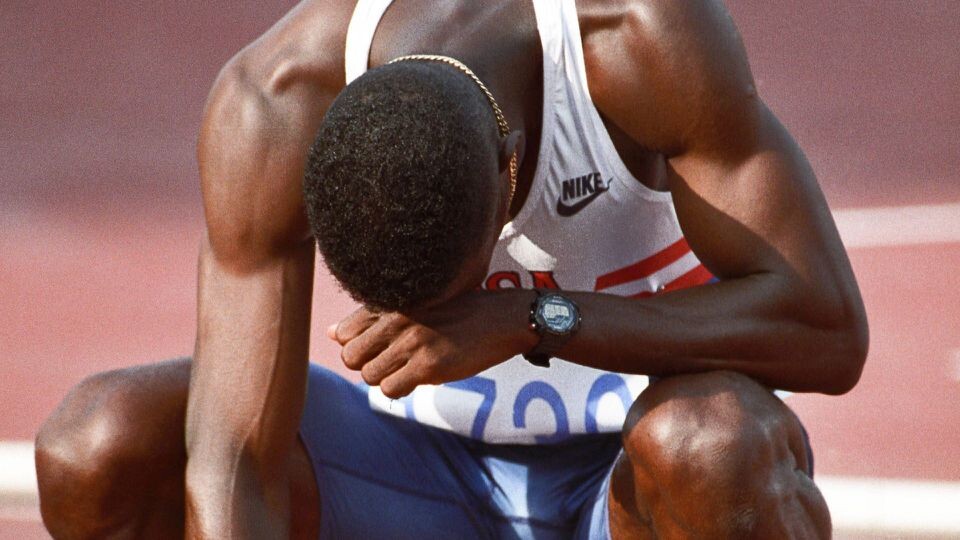

Bolt retired from athletics after the 2017 World Championships, where he won bronze in his final solo 100m race but then pulled up in his last ever contest in the 4x100m relay final.

After refusing a wheelchair, he hobbled across the finish line alongside his teammates - but, despite his legendary career ending in heartbreak, Bolt will go down as one of the track's greatest ever competitors.

by Evans Ousuru

Login to leave a comment

'I want to be the best to ever do it'- American sprint sensation still dreaming big despite injury woes

The two-time world bronze medalist wants to come back and continue his legacy after injuries slowed him down in the last two years.

American sprint sensation Trayvon Bromell has been a victim of injuries but he now feels ready to come back in 2025 and continue the legacy he had in 2022.

Bromell is one of America’s great sprinting talents but the world never got to see his full potential in the recent events.

In 2024, the two-time world bronze medallist had to pull out of the Olympic trials due to an injury he picked up at a meeting in Savona.

The injury was a huge setback in his career that was just beginning to pick up after his major injury in 2019 when he suffered an adductor muscle setback.

In a previous interview with NBC Sports, Bromell disclosed that his ambition is to surpass the likes of Usain Bolt and Tyson Gay and become one of the greatest sprinters in the world.

Bromell wants his achievements to be beyond the titles and the medals and he pointed out that his definition of success is very different from what other people think.

“Everybody didn’t see me and hear me back then, but now you have to. I want to be the best to ever do it,” Bromell said.

“The odds have always been stacked against me in my life, and that’s why I get emotional after running crazy times. It’s never been about the race or the medals for me.”

He opened up about growing up in a single-parent home and how he struggled to be heard by those around him. Growing up to become one of America’s greatest talents brings him to tears.

Bromell revealed that he wants to be a testimony to all those who feel like some things are impossible. The former world indoor champion further noted that the people who have grown up in such a setup would understand the struggle.

“Being the greatest of all time in this event. I’m a big advocate of making people see me, but when I say that I don’t mean it in a literal sense,” Bromell said.

“But for all of those people who know what it feels like to not be heard or to not be seen ... I want to prove that it’s possible.”

Being raised up by his mother was not easy since she was also struggling to make ends meet. Bromell had to be strong at a young age and take up responsibilities that were meant for adults.

With such a lifestyle, he struggled to maintain a positive outlook in life and was filled with a lot of resentment towards everybody.

“I feel like nobody heard my cries for help, nobody was there for me, and I grew up with so much aggression because I felt like nobody cared and the world was against me,” he added.

by Abigael Wafula

Login to leave a comment

Usain Bolt reveals bizarre reason he dropped running 400m

Bolt loved all the short distance races but 400m was never his long-term priority even though he preferred it early in his trophy-laden career.

Jamaican sprint legend Usain Bolt has revealed what made him stop taking part in 400m despite loving the specialty in his formative years.

Bolt, the three-time Olympic 100m champion, said his coach Glen Mills was one of many people who felt the younger Bolt was better suited to the longer sprint distance than the marquee 100m event, meaning the 6ft 5ins sprinter almost ended up as a quarter-miler, much to his disgust.

The three-time Olympic 200m champion reiterated that even though he liked 400m, doing away with it and focusing on 100m paid dearly for him going by his record.

"Running the 400m wasn’t fun at all. It was always pain. But I was good at it, so I used to do it. However much as I did it, though, I never liked it. So I stopped and went back to the 100m. You could say I’m happy it worked out," Bolt told TalkSport.

"The over-distance runs are the hardest thing we do in training, because when you feel that lactic acid you can’t walk, you can’t sit down, you don’t know what to do – it takes a while to get it out of your system,” he added.

The 11-time world champion said time wasn't everything and his focus was always the technique. "All we try to focus on is technique because, the better you get at these things, the better the times will get. When the champs come, then you can try to run fast.”

The 38-year-old is the most successful male athlete of the World Championships. Bolt is the first athlete to win four World Championship titles in the 200m and is one of the most successful in the 100m with three titles, being the first person to run sub-9.7s and sub-9.6s races.

by Evans Ousuru

Login to leave a comment

16-year-old Aussie sprinter clocks outrageous 100m time

Gout Gout, the young athlete drawing comparisons to Usain Bolt, now holds the Australian U18 100m and 200m records.

Australia’s Gout Gout has left the world speechless once again. At Friday’s Australian All Schools Athletics Championships in Nathan, Australia, the sprinter made a run at the elusive 10-second barrier–at the age of just 16. In heats, he soared to a blazing 10.04 seconds (+3.4 m/s winds), crossing the line more than five tenths of a second ahead of second place. Including all non-legal marks, Gout’s time secured him the number-four spot on the all-time U18 list.

Tailwind speeds exceeding 2.0 m/s are deemed illegal in sprinting, as stronger winds are considered to aid the racers. Wind assistance can impact times by about 0.1 seconds, a substantial difference in the world of sprinting.

In the 100m final at the Queensland Sport and Athletics Centre, Gout went on to run a stunning (and wind-legal) 10.17. The time shattered his own personal best of 10.29 and the previous U18 Australian record of 10.27 held by Sebastian Sultana, and still places him sixth on the all-time U18 list.

The high schooler first made headlines when he cruised to a 20.77-second win in the qualifying rounds of the 200m at the World U20 Championships in Lima, Peru, in August. The following day, he clinched the silver medal in the event’s final.

Gout signed a pro contact with Adidas in October, and just a week later, clocked an electrifying 20.29 at the All Schools Queensland track and field championships. The time broke his own U18 national record, along with the 31-year-old U20 national record and the Oceanic record. His time was the fourth-fastest in Australia’s history.

Gout’s race on Friday clip is his second to go viral in the athletics world in four months; many track and field fans began drawing comparisons of his tall stature and running style to those of Jamaican track legend Usain Bolt.

by Cameron Ormond

Login to leave a comment

Hassan and Tebogo named World Athletes of the Year

Olympic champions Sifan Hassan and Letsile Tebogo have been announced as World Athletes of the Year at the World Athletics Awards 2024 in Monaco.

Following a vote by fans, Hassan and Tebogo received top honors on an evening that saw six athletes crowned in three categories – track, field and out of stadium – before the overall two winners were revealed.

Tebogo was confirmed as men’s track athlete of the year, with Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone receiving the women’s honour. Hassan claimed the women’s out of stadium crown and Tamirat Tola the men’s, while Mondo Duplantis and Yaroslava Mahuchikh were named field athletes of the year.

This year’s Rising Stars were also celebrated, with Sembo Almayew and Mattia Furlani receiving recognition.

World Athletes of the Year for 2024

Women’s World Athlete of the Year: Sifan Hassan (NED)Men’s World Athlete of the Year: Letsile Tebogo (BOT)

Women’s track: Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone (USA)Women’s field: Yaroslava Mahuchikh (UKR)Women’s out of stadium: Sifan Hassan (NED)Men’s track: Letsile Tebogo (BOT)Men’s field: Mondo Duplantis (SWE)Men’s out of stadium: Tamirat Tola (ETH)

Women’s Rising Star: Sembo Almayew (ETH)Men’s Rising Star: Mattia Furlani (ITA)

“At the end of what has been a stellar year for athletics, we are delighted to reveal our list of World Athletes of the Year – both in their respective disciplines and overall,” said World Athletics President Sebastian Coe. “This group of athletes represents the very best of our sport and has this year redefined what is possible in terms of athletic performance.

“Our 2024 cohort set new standards in heights, speed and distance, including six world records and a host of Olympic and national records between them.

“I congratulate all our award winners, and all of the athletes nominated for these honors, and I thank them for inspiring us all with their performances this year.”

World Athletes of the Year Hassan and Tebogo both won gold and claimed multiple medals at the Paris 2024 Olympic Games.

Dutch star Hassan’s medal treble in Paris was capped by her winning the final athletics gold medal of the Games with her triumph in the marathon in an Olympic record of 2:22:55. That performance came just 37 hours after Hassan claimed bronze in the 10,000m, and six days after her first medal in the French capital – also bronze – in the 5000m.

As a result, she became the first woman to win medals in the 5000m, 10,000m and marathon at the same Games, and the first athlete since Emil Zatopek, who won all three men’s titles in Helsinki in 1952.

Tebogo also made history in Paris when he won the 200m, as he claimed a first ever Olympic gold medal in any sport for Botswana. He ran an African record of 19.46 – a time that moved him to fifth on the world all-time list – and that performance followed his sixth-place finish in the 100m final. He went on to form part of Botswana’s silver medal-winning men’s 4x400m team.

He dipped under 20 seconds for 200m a total of nine times in 2024, with those performances topped by his Olympic title-winning mark which remained the fastest of the year.

His fellow track athlete of the year, McLaughlin-Levrone, improved her own world 400m hurdles record twice, to 50.65 and 50.37, and claimed Olympic gold in that event as well as in the 4x400m. Tola, who joined Hassan in being named out of stadium athlete of the year, won the Olympic marathon title in Paris in an Olympic record.

World records were set by both field athletes of the year. Mahuchikh cleared 2.10m to improve the world high jump record before winning Olympic gold, while Duplantis revised his own world pole vault record three times, eventually taking it to 6.26m, and won the Olympic title.

"Thank you to the fans, to everybody who voted," said Hassan, who was in Monaco to receive her two awards. "I never thought I was going to win this one. This year was crazy. It’s not only me – all the athletes have been amazing. I’m really grateful. What more can I say?"

Standing alongside Hassan on the stage at the Theatre Princesse Grace, Tebogo said: "It feels amazing to know that the fans are always there for us athletes. It was a great year.

"This means a lot," he added. "It’s not just about the team that is around you, there are a lot of fans out there that really want us to win something great for the continent. It was a real surprise to hear my name because I didn’t expect this."

Almayew and Furlani named Rising Stars of 2024

Not only did Sembo Almayew and Mattia Furlani achieve great things as U20 athletes in 2024, they both also secured success on the senior stage.

Almayew finished fifth in the 3000m steeplechase final at the Paris Olympics, going close to her own national U20 record with her 9:00.83 performance, before she travelled to Lima where she won the world U20 title, setting a championship record in the process. With that win, the 19-year-old became the first ever Ethiopian world U20 women’s steeplechase champion.

Furlani improved the world U20 long jump record to 8.38m at the European Championships on home soil in Rome to secure silver, and he won two more senior major medals at the World Indoor Championships, where he got another silver, and the Olympic Games, where he claimed bronze.

In Glasgow – at the age of 19 years and 24 days – Furlani became the youngest athlete ever to win a world indoor medal in the horizontal jumps.

Knight wins President’s Award

The winner of the President’s Award was also announced in Monaco on Sunday (1), with Nike co-founder Phil Knight receiving the honour in recognition of his constant inspiring support for athletics and the development of the sport.

The President's Award, first awarded in 2016, recognises and honours exceptional service to athletics. Past winners of the award include the Ukrainian Athletics Association, British journalist Vikki Orvice, Swiss meeting director Andreas Brugger, Jamaican sprint superstar Usain Bolt, the Abbott World Marathon Majors, and 1968 men’s 200m medallists Tommie Smith, Peter Norman and John Carlos for their iconic moment on the podium in Mexico.

“Phil Knight’s passion for athletics is pretty much lifelong,” said Coe. “He developed an almost father-son relationship with his coach, the legendary Bill Bowerman, whose training approach was a departure from the orthodoxies of the day and who not only guided Knight’s career on the track but became a central figure when Phil took his first tentative steps in the running shoe business that became the dominant global force Nike.

“His love of athletics runs through Nike. It is a business created and driven by runners, with Phil never afraid to be the front runner.”

Knight said: “Thank you, Seb Coe, for the ultimate honour of the President’s Award, given by World Athletics. I am in great company, with Tommie Smith and John Carlos, and Usain Bolt. Obviously, I didn’t run as fast as those guys, but I am in such high company that I am thrilled by the award. Track and field has always been an important part of Nike – it has always been a central part of who Nike is.

“I do think running will continue to grow. Not only does Seb and his team do a great job promoting the sport, but it is a sport that not only is enjoyable, but it is probably the best fitness activity you can do. So, for me to win this honour, it is very meaningful.”

During the ceremony, a moment was taken to remember last year’s men’s out of stadium athlete of the year Kelvin Kiptum, the marathon world record-holder who died in a road traffic accident in February, as well as other figures from the sport who have passed away in 2024.

by World Athletics

Login to leave a comment

Afghan sprinter homeless in Germany after Paris Olympics

Less than four months ago, Afghanistan sprinter Sha Mahmood Noor Zahi proudly carried his country’s flag down the River Seine at the 2024 Paris Olympics. A week later, he became a household name in Afghanistan by setting a national record in the men’s 100m preliminary round, missing a qualifying spot in the heats by just one place. At that moment, Noor Zahi made the biggest decision of his life: choosing to leave his country with a one-way ticket to Germany in hopes of a better future.

In an interview with the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, Noor Zahi said he has been living in a shelter in the city of Schweinfurt for the past few months while awaiting his asylum application. Though he does not speak English or German, he can be found training four to (sometimes) five hours a day at Sachs Stadion, the home of the city’s soccer team.

The 33-year-old achieved his dream of running at the Olympic Games through a universality place selection for Tokyo 2020. (The program aims to ensure broader global representation at major championships by allowing athletes from countries with less-developed sports programs to participate). Noor Zahi has taken full advantage of the opportunity, lowering his 100m personal best from 11.04 seconds to 10.64 seconds in the span of three years. Although he does not have a coach, he continues to follow the training plan he received in Iran before the Paris Olympics.

Noor Zahi’s main goal is to qualify for the 2028 Olympics in Los Angeles (his third Olympics), when he would be 37. He has ambitions to become the first person from his country to run under 10 seconds and qualify for an Olympic final. “I’ve run and run to overcome many obstacles,” he said about his challenges. “So why stop now?”

An athlete he has always admired is Jamaica’s Usain Bolt, whom he recalls watching in videos on his mobile phone in his younger days in Afghanistan. Noor Zahi pointed to Bolt’s speed, confidence and the way he graced the track. For Noor Zahi to achieve his goal, he needs to stay in Germany, where he can continue to train and pursue a career in athletics.

The situation in his home country remains dire. The radical Islamist Taliban group regained power in 2021 after the withdrawal of international troops. Since then, the group has been publicly executing people in stadiums, and women are only allowed on the streets when accompanied by men.

Noor Zahi is aware that he is also fighting a battle against time in sprinting, where athletes over 30 rarely set personal bests. His idol, Bolt, set his world record at 23 and was 30 when he won his final Olympic medals in Rio 2016.

by Marley Dickinson

Login to leave a comment

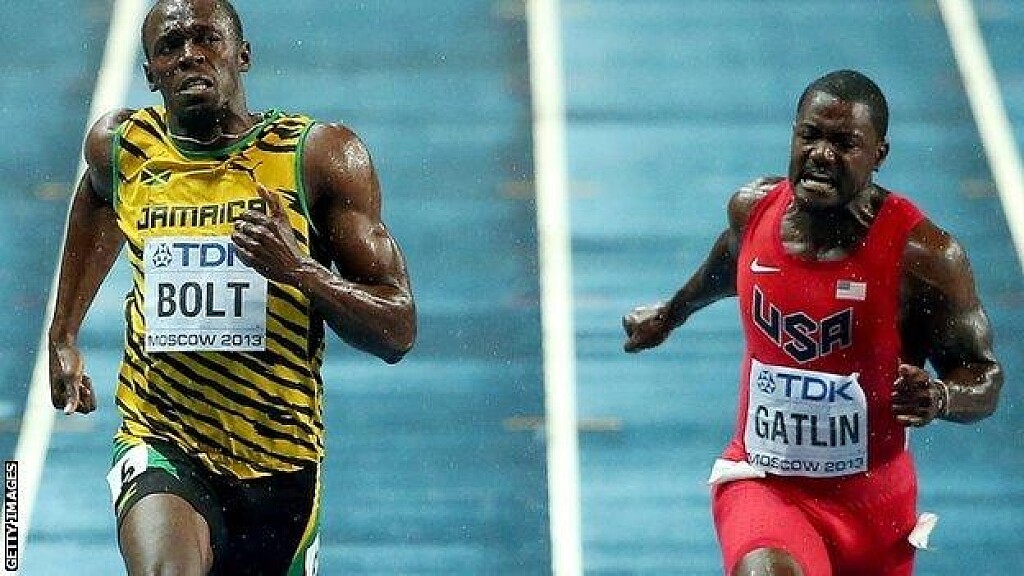

'He made me eat cleaner & work harder' - Justin Gatlin on how Usain Bolt shaped him into becoming a better sprinter

Justin Gatlin has heaped praise on his long-time arch-nemesis Usain Bolt, thanking him for making him the athlete he ended up becoming after returning to the sport.

American sprint icon Justin Gatlin has revealed the profound impact Usain Bolt had on his career, acknowledging how the Jamaican legend pushed him to reach new heights.

Known for a rivalry that defined an era of sprinting, Gatlin and Bolt clashed in numerous unforgettable races, showcasing contrasts in style and personality. Yet, despite the fierce competition, Gatlin now reflects on their encounters with admiration, crediting Bolt for inspiring him to be his best.

“Competing against someone like him, he brought the best out of me,” Gatlin said on The Higher Perspective Talks.

His comments came just over a week after Bolt himself recognized Gatlin as his toughest competitor. Gatlin expressed that Bolt’s presence on the track forced him to elevate his approach to training, nutrition, and overall athletic dedication.

“He made me wanna train harder. He made me wanna be a different athlete. He made me eat cleaner, work harder, compete harder because that was an athlete that represented a standard, one that I always wanted to get to,” Gatlin explained, underscoring the high benchmark Bolt set with his relentless speed and unwavering confidence.

Reflecting on their head-to-head races, Gatlin noted that he was always ready to face Bolt, eager to test himself against the reigning champion. “When I banged against him, I was ready any time. I wanted to race him every day if I could,” Gatlin shared. His words highlight not only the intensity of their rivalry but also the motivation he found in trying to match Bolt’s prowess.

Usain Bolt also had kind words for Gatlin during a recent appearance on John Obi Mikel’s Obi One podcast. “I think Justin Gatlin, I have to give my hats off to him,” Bolt said. “The last five, six years of my career, it was me and him every season. He kept me on my toes throughout, and I loved the competition.”

Bolt recalled a particularly memorable exchange when he saw a video of Gatlin confidently declaring his intent to win gold.

“I remember I’m just on Instagram scrolling, and someone sent me a video,” Bolt recounted. “He [Gatlin] was like, ‘Justin, I’m gonna win, don’t worry, and I’m going to wear the gold medal around my neck.’ And I’m like, ‘What? Alright, let’s go then.’”

Recognizing Gatlin’s fierce resolve, Bolt added, “Listen, Gatlin is going to show up. He is that guy in a Championship; no matter what is going on, he is going to show up.”

Their rivalry may have seen Bolt take the lion’s share of victories, but the respect they have for one another transcends competition.

As Gatlin reflects on his journey, it’s clear that Bolt’s influence left a lasting mark, inspiring him to push beyond his limits in pursuit of excellence. Their rivalry brought unparalleled excitement to the sport, and their mutual respect continues to exemplify the power of elite competition.

by Mark Kinyanjui

Login to leave a comment

Record-breaking teen sprinter Gout Gout is set to train alongside Noah Lyles

Gout Gout recently signed with Adidas and will have the opportunity to train alongside world champion Noah Lyles, gaining valuable mentorship as he continues his path to the top.

After inking a lucrative deal with leading German athletic apparel and footwear corporation Adidas, Gout Gout will now have a chance to train with triple world champion Noah Lyles.

Gout Gout’s manager James Templeton noted that it is a great opportunity for the youngster to interact with Noah Lyles and get to know more about sprinting as he looks to chat his own path to the top.

James Templeton is optimistic that Noah Lyles will be open to teaching Gout Gout a lot, noting that he believes the reigning Olympic 100m champion is a great personality to be around.

Noah Lyles is also an Adidas athlete and earlier this year, the American sprint king extended his contract until the 2028 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. Noah Lyles’ contract with Adidas is considered the richest in track and field since Usain Bolt's deal with Puma.

"We have the opportunity to go to Florida and join the training group of Noah Lyles and coach Lance Brauman (Lyles’ coach). There are about 16 or 18 top sprinters there,” James Templeton told ABC News.

"We'll be heading over for two or three weeks. That'll be a great opportunity, a wonderful educational experience. I haven't heard from Noah, but he's a great guy and I'm sure he'll be happy to take the younger guy under his wing a little bit."

Meanwhile, Gout Gout has been very impressive in his races and since 2022, he has proven to be unstoppable, running crazy times and making headlines. Gout Gout was named the holder of the Australian Under-16 100m and 200m records at the age of 14.

The following year, Gout Gout managed to break the Australian Under-18 men’s 200m record after running 20.87 seconds. He claimed top honors at the Australian Junior Athletics Championships in Brisbane.

In 2024, Gout Gout has been on top of the world with his crazy times and superb form. He started his season with a personal best time of 10.29 seconds to claim the win in the U-18 Boys 100m at the Queensland Athletics Championships.

Gout Gout then won the Australian U20 100m title in a time of 10.48 seconds in Adelaide before heading to the World Athletics U20 Championships in Lima, Peru. In Peru, the Australian youngster won a silver medal in the 200m.

He recently signed with Adidas and then proceeded to the Queensland All-Schools Championships, clocking a time of 20.29 seconds in the heats of the 200m to showcase his authority once again.

by Abigael Wafula

Login to leave a comment

Usain Bolt shares the best advice he’s ever received

Known for his iconic celebrations and world-record-breaking times, eight-time Olympic gold medallist Usain Bolt shared a powerful piece of advice from his long-time coach on this week’s episode of the High-Performance Podcast.

Bolt credited his coach, Glen Mills—who led the Jamaican Olympic track and field team for two decades—for the advice that shaped the rest of his career. Mills began coaching Bolt after his Olympic debut in Athens 2004, where Bolt, then a rising talent, failed to advance from the men’s 200m heats.

After that, Mills told Bolt, “You have to learn how to lose before you can learn how to win.” As a teenager, Bolt didn’t fully grasp what Mills meant by it, but it became clear. “You will fail at some point,” Bolt said on the podcast. “What’s important is what you take away and learn from it. If you can be truthful and honest with yourself, you’ll realize what you need to do to get better.”

Bolt came to Mills as a 200m specialist and credits his coach with developing his explosive power in the 100m—a distance in which Bolt set a world record of 9.58 seconds in 2009, a record that remains unbroken.

Bolt went on to become the seventh man in history to win Olympic gold in both the 100m and 200m at the 2008 Games in Beijing, a feat he accomplished twice more in his career, at London 2012 and Rio 2016—making him the only athlete in history to achieve a three-peat in these two sprint events.

The 38-year-old officially retired after the 2017 World Championships and briefly tried his hand at professional soccer with Australia’s Central Coast Mariners in 2018.

by Marley Dickinson

Login to leave a comment

16-year-old Aussie sprinter turns pro with Adidas

The Grade 11 sprinter’s running style and tall frame have been compared to that of the legendary Usain Bolt.

Australia’s sprint sensation Gout Gout has signed a professional contract with Adidas at just 16.

The high schooler made headlines after he cruised to a 20.77-second win in the qualifying rounds of the 200m at the World U20 Championships this past August. The clip went viral in the athletics world, and track and field fans drew comparisons from his tall stature and running style to those of Jamaican track legend Usain Bolt.

“Usain Bolt is that you?” one comment said.

“Gout Gout reminds me of Usain Bolt. He will definitely level up with him,” said another.

The following day, Gout ran another personal best of 20.60 seconds in the 200m final, setting an Australian U18 record and winning silver. He was outrun by South Africa’s Bayanda Walaza who took home double golds in the World U20 100m and 200m and won silver in the 4x100m relay at the Paris Olympics earlier that month. Walaza is two years older than Gout, who was competing against athletes three to four years older.

The Aussie’s performance surpassed Bolt’s own winning time from the 2002 Junior World Championships in Kingston, Jamaica, where the 16-year-old Jamaican clocked 20.61. “It’s pretty cool because Usain Bolt is arguably the greatest athlete of all time, and just being compared to him is a great feeling,” Gout said.

Like Bolt, the 200m isn’t Gout’s only event. He also holds a personal best of 10.29 in the 100m and has held the Australian U18 200m record since last year, at just 15.

In 2005, Gout’s parents moved from South Sudanese to Brisbane, Australia where Gout was born in 2007. The athlete attends Ipswich Grammar School, an all-boys boarding school, in Queensland, Australia, where he first showed off his athleticism in rugby. He’ll only be 24 when the Olympics come to his hometown of Brisbane in 2032.

by Cameron Ormond

Login to leave a comment

How to train for a marathon no matter how fit you are

If you’re planning a marathon, you’re on the road to becoming part of a select proportion of the global population – 0.01 per cent, to be exact. But that doesn’t mean running one is exclusive to the lycra-clad minority. With the right planning, training and dogged determination anyone can have a go. Here’s what you need to know if you’re gearing up to train for the race of your life.

Which marathon should I choose to run?

The London Marathon is special, with incredible atmospheric and historic appeal, but it’s notoriously tricky to get a place and is far from the only one to consider. All marathons are 26.2 miles, so if you’re a beginner, you might want to choose what seasoned runners call an “easy” marathon – one with a flat and paved course. While the Brighton Marathon is one of the most popular (and mostly flat) UK spring races, the Greater Manchester Marathon is known as the flattest and fastest UK option. The under-the-radar Abingdon Marathon is one of the oldest in the UK and also has a flat route – great for new runners and for those who are keen to beat their personal bests.

Around Europe, try the Berlin and Frankfurt marathons in Germany, or the Amsterdam Marathon in the Netherlands. More recently, the Valencia and Seville marathons in Spain have grown in appeal. For a great beginner list, visit coopah.com. It’s worth doing your research to ensure it’s a route you’ll enjoy (atmospheric, well populated, flat, historic… whatever piques your interest), as this will pay dividends when things get tough.

Training

How long does it take to train for a marathon?

“You need 16-to-18 weeks of training,” says Richard Pickering, a UK Athletics qualified endurance coach. “And if you’re starting from nothing, I think you need closer to six months.” This may sound like a long time to dedicate to one event but a structured plan will help you develop the strength, endurance and aerobic capacity to run longer distances. Not to mention work wonders for your overall health.

“Anyone can run a marathon if they are willing to put in the hard work,’ says Cory Wharton-Malcolm, Apple Fitness+ Trainer and author of All You Need Is Rhythm & Grit . “As long as you give yourself enough time and enough grace, you can accomplish anything.’

Ready to get running? Read on.

Five steps to preparing for a marathon

1. Follow a training plan and increase mileage gradually

“Even if it’s a simple plan, and that plan is to run X times per week or run X miles per week, it’s beneficial to have something guiding you,’ says Wharton-Malcolm. ‘It’s happened to me, without that guidance, you may overtrain causing yourself an injury that could have been avoided. And if you’re injured, you’re far less likely to fall in love with running.”

For authoritative plans online, see marathon event websites (try the Adidas Manchester Marathon or the TCS London Marathon websites) or from a chosen charity such as the British Heart Foundation. Most will consist of the key training sessions: speed work (spurts of fast running with stationary or active rest periods), tempo runs (running at a sustained “comfortably uncomfortable” pace), and long-distance slogs.

Most marathon plans will abide by the 10 per cent rule, in that they won’t increase the total run time or distance by more than 10 per cent each week – something that will reduce your risk of injury.

2. Practise long runs slowly

Long runs are your bread-and-butter sessions. They prepare your body to tolerate the distance by boosting endurance, and give you the strength to stay upright for hours. Intimidating as this sounds, the best pace for these runs is a joyously slow, conversational speed.

“People may think they need to do their marathon pace in long runs,” says Pickering, “but it’s good to run slowly because it educates the body to burn fat as fuel. This teaches it to use a bit of fat as well as glycogen when it goes faster on race day, and that extends your energy window so that you’re less likely to hit the ‘wall’.”

The caveat: running slowly means you’re going to be out for a while. With the average training plan peaking at 20 miles, you could be running for many hours. “When I did lots of long runs, I had a number of tools: listening to music, audio-guided runs, apps or audio books,” says Wharton-Malcom. “I used to run lots of routes, explore cities… You can also do long runs with friends or colleagues, or get a train somewhere and run back so it’s not the same boring route.”

3. Do regular speed work

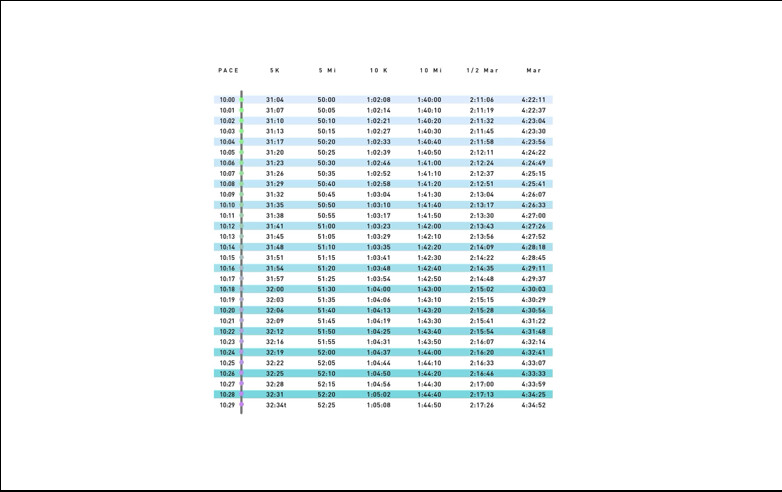

Speed work may sound like the reserve of marathon aficionados, but it’s good for new long-distance runners too. “I think people misunderstand speed work,” says Wharton-Malcom. “The presumption is that the moment you add ‘speed’ to training, you have to run like Usain Bolt, but all ‘speed’ means is faster than the speed you’d normally be running. So if you go out for a 20-minute run, at the end of the first nine minutes, run a little faster for a minute, then at the end of the second nine minutes, run a little faster for a minute.”

Small injections of pace are a great way for novices to reap the benefits. “The idea is to find the sweet spot between ‘Ah, I can only hold on to this for 10 seconds’ and ‘I can hold on to this for 30-to-60 seconds’,” he adds.

Hill sprints are great for increasing speed. Try finding a loop with an incline that takes 30 seconds to ascend, then run it continuously for two to three lots of 10 minutes with a 90-second standing rest.

Interval work is also a speed-booster. Try three lots of three minutes at tempo pace with a 90-second standing rest. “The recovery [between intervals] is when you get your breath back and your body recirculates lactate [a by-product of intense exercise, which ultimately slows bodies down],” explains Pickering, “and this means you’re able to do more than you otherwise would.”

4. Run at marathon-pace sometimes

Every now and then, throw in some running at your chosen race pace. “You need to get used to a bit of marathon pace,” says Pickering, “but I wouldn’t put it into your programme religiously.”

Some runners like to practise marathon pace in a “build-up” race, typically a half-marathon. “It can give people confidence,” says Pickering. “Your half-marathon should be six-to-seven weeks prior to the main event, and have a strategy to ensure you’re not racing it because you need to treat it as a training run.”

5. Schedule in rest and recovery

Of course, no training plan is complete without some R&R. Rest days give your body a chance to adapt to the stresses you’ve put it through and can provide a mental break. “Active recovery” is a swanky term for taking lighter exercise such as an easy run, long walk, gentle swim, some yoga – crucial because you don’t want to do two hard sessions back-to-back. “A long run would count as a hard day, so if your long run is on Sunday, you could do an easy run such as 30-40 minutes at a conversational pace on a Monday, but don’t do anything fast until Tuesday,” says Pickering.

What about recovery tools?

Foam rollers, massage guns, ice baths – the list is long. Pickering says to keep it simple: “I would encourage foam rolling [relieving muscle tension by rolling over a foam tube] or sports massage, and they’re kind of the same thing.”

And Wharton-Malcom swears by the restorative power of a good rest: “From personal experience, sleep is our secret weapon and it’s so underrated. Getting your eight-hours-plus per night, taking power naps during the day… you can do so well with just sleeping a bit more.”

Race day

How to perform your best on race day – what to eat

“The marathon is going to be relying on carbohydrate loading [such as spaghetti, mashed potato, rice pudding], which should take place one-to-three days before an event,” explains performance nutritionist Matt Lovell. Other choices might include: root vegetables (carrots, beetroot), breads or low-fat yoghurts.

“On the day, the main goal is to keep your blood glucose as stable as possible by filling up any liver glycogen.” Which means eating a breakfast rich in slow-release carbohydrates, such as porridge, then taking on board isotonic drinks, like Lucozade Sport or coconut water, and energy gels roughly every 30-45 minutes.

How to stay focused

Even with the right fuel in your body, the going will get tough. But when you feel like you can’t do any more, there is surprisingly more in the tank than you realise.

“Sports scientists used to think we eat food, it turns into fuel within our body and, when we use it up, we stop and fall over with exhaustion,” says performance psychologist Dr Josephine Perry. “Then they did muscle biopsies to understand that, when we feel totally exhausted, we actually still have about 30 per cent energy left in the muscles.”

How do you tap into that magic 30 per cent? By staying motivated – and this ultimately comes down to finding a motivational mantra that reminds you of your goal and reason for running.

“Motivational mantras are incredibly personal – you can’t steal somebody else’s because it sounds good; it has to talk to you,’ explains Dr Perry, author of The Ten Pillars of Success. “Adults will often have their children as part of their motivational mantra – they want to make them proud, to be a good role model. If you’re doing it for a charity, it might be that.” Write your motivational mantra on your energy gel, drinks bottle or hand. “It doesn’t just need to come from you,” adds Dr Perry. “I love getting athletes’ friends and family to write messages to stick on their nutrition, so every time they take a gel out of their pocket, they’ve got a message from someone who loves them.” Perry is supporting the Threshold Sports’ Ultra 50:50 campaign, encouraging female participation in endurance running events.

Smile every mile, concludes Dr Perry: “Research shows that when you smile it reduces your perception of effort, so you’re basically tricking your brain into thinking that what you’re doing isn’t as difficult as it is.”

One thing is for sure, you’re going to be on a high for a while. “What happens for most people is they run the race and, for most of the race, they say ‘I’m never doing this again,’ says Wharton-Malcom. “Then the following morning, they think, ‘OK, what’s next?’”

What clothes should you wear for a marathon?

What you wear can also make a difference. Look for clothing made with moisture-wicking fabrics that will move sweat away from the skin, keeping you dry and comfortable. An anti-chafe stick such as Body Glide Anti-Chafe Balm is a worthy investment, or simply try some Vaseline, as it will stop any areas of the skin that might rub (under the arms, between the thighs) from getting irritated. Seamless running socks, like those from Smartwool, can also help to reduce rubbing and the risk of blisters.

Post-race recovery

What to eat and drink

Before you revel in your achievement, eat and drink something. Lovell says recovery fuel is vital: “Getting carbohydrates back into the body after a marathon is crucial. It’s a forgiving time for having lots of calories from carbohydrates and proteins, maybe as a recovery shake or a light meal such as a banana and a protein yoghurt.”

Have a drink of water with a hydration tablet or electrolyte powder to replenish fluid and electrolyte salts (magnesium, potassium, sodium) lost through sweat.

“You can have a glass of red later if you want, but your priority is to rehydrate with salts first, then focus on carbohydrate replenishment, then have some protein, and then other specialist items such as anti-inflammatories.” Choose anti-inflammatory compounds such as omega 3 and curcumin from turmeric, which you can get as a supplement, to help reduce excessive inflammation and allow for better muscle rebuilding.

Tart cherry juice – rich in antioxidants, anti-inflammatories and naturally occurring melatonin – could also be useful, with the latest research reporting that it can reduce muscle pain after a long-distance race and improve both sleep quantity and quality by five-to-six per cent. “And anything that improves blood flow such as beetroot juice, which is a good vasodilator, will help with endurance and recovery,” adds Lovell. Precision Hydration tablets are very good for heavy sweaters.

Any other other good products to help with recovery?

The post-run recovery market is a saturated one, but there are a few products worth trying. Magnesium – from lotions and bath flakes to oil sprays drinks and supplements – relaxes muscles and can prevent muscle cramps, as well as aiding recovery-boosting sleep.

Compression socks boost blood flow and therefore the removal of waste products from hardworking muscles, and have been shown to improve recovery when worn in the 48 hours after a marathon. Arnica has anti-inflammatory properties that can help speed up the healing process after a long run, and can be used as an arnica balm or soak.

by The Telegraph

Login to leave a comment

Another look at the new women’s marathon record set in Chicago today

30-year-old Kenyan Ruth Chepngetich destroyed the women’s marathon world record today (13 Oct. 2024) at the 46th Bank of America Chicago Marathon. Her time of 2:09:56 ripped 1:57 from the previous mark set in Berlin 2023 by Ethiopia’s Tigst Assefa (2:11:53).

At this point, the athletics record book feels like it ought to be written in No. 2 Ticonderoga pencil. That’s how fast records fall in this age of technological and nutritional advances. This is especially true at the longer distances where such advancements create greater margins.

Still, Ruth Chepngetich’s new world record stands out as history’s first women’s sub-2:10, and first sub-5:00 per mile pace average. But Tigst Assefa’s 2:11:53 mark set last year in Berlin had us all cradling our heads, as well. That performance cut 2:11 off Brigid Kosgei‘s 2:14:04 record from Chicago 2019, which shattered Paula Radcliffe‘s seemingly impregnable 2:15:25 set in London 2003.

In each case: Radcliffe’s, Kosgei’s, Assefa’s, and now Chepngetich’s record have caused mouths to gape in the immediacy of their efforts. But nothing should surprise us anymore.

Racing is often a self-fulfilling prophecy determined by one’s build-up. Ruth Chepngetich said in her TV interview she came into Chicago off a perfect three-months of training after her disappointing ninth-place finish in London in April (2:24:36). Two previous wins in the Windy City (2021 and 2022) and a runner-up in 2023 meant Ms. Chepngetich arrived well seasoned on this course, with a keen understanding of what training was required to produce such a record run.

Of course, sadly, no record in athletics can be free of skepticism considering the industrial level of PED use that is uncovered, seemingly, every other Tuesday. Though understandable, cynicism should not be one’s default reaction.

To maintain any allegiance to the game, to follow it with any interest at all, we have to celebrate each record at face value. Just as rabid fans have to acknowledge some records to be ill-gotten, cynics accept that many special runs are exactly as they appear, above reproach.

Besides, when you break down Ruth’s 5k splits, each one from 5k to 35k was slower than the previous 5k. Not until the split from 35k to 40k (15:39) did she run faster than the split before (15:43 from 30 to 35k)

5k – 15:0010k – 30:14 (15:14)15k – 45:32 (15:18)20k – 60:51 (15:19)25k – 1:16:17 (15:26)30k – 1:31:40 (15:32)35k – 1:47:32 (15:43)40k – 2:03:11 (15:39)Fini – 2:09:56

1st half – 64:162nd half – 65:40

So congratulations to Ruth Chepngetich and her team for a marvelous run through a beautiful city. Now, let’s see how long this mark stays on the books before the No. 2 Ticonderoga pencil gets pulled out again.

BY THE NUMBERS

There have been 26 women’s world records set in the marathon since Beth Bonner‘s 2:55:22 in New York City in 1971. Over the ensuing 53 years, the average percentage change from one record to the next has been 1:26%. See WOMEN’S WORLD RECORD PROGRESSION.

Today’s record by Ruth Chepngetich, 2:09:56 (just one second slower than Bill Rodgers‘ American men’s record in Boston 1975!), lowered Tigst Assefa’s 2:11:53 mark by a healthy 1.5%. And Assefa’s time cut Brigid Kosgei’s 2:14:04 by 1.65%.

These latest records are still taking significant chunks off their predecessors and doing so in quick order. That suggests women are far from slicing everything they can from even this new record.

Yet, when comparing the women’s marathon world record to the men’s (2:00:35, set by Kelvin Kiptum in Chicago 2023), we see a differential of 7.2%. That is by far the best women’s record vis-à-vis the men’s throughout the running spectrum. Second place on that list is Florence Griffith-Joyner‘s 10.49 100m in relation to Usain Bolt‘s 9.58, a percentage difference of 8.675%.

The traditional rule of thumb has been a 10% gap between men’s and women’s records. But there are so many factors in play, it is difficult to make any definitive statement that explains one event, much less one athlete from another. I guess that’s why we keep watching.

by Toni Reavis

Login to leave a comment

Bank of America Chicago

Running the Bank of America Chicago Marathon is the pinnacle of achievement for elite athletes and everyday runners alike. On race day, runners from all 50 states and more than 100 countries will set out to accomplish a personal dream by reaching the finish line in Grant Park. The Bank of America Chicago Marathon is known for its flat and...

more...5 track stars we'd love to see on Dancing with the Stars

With Season 33 of Dancing with the Stars well underway, we’re seeing Olympic athletes like Team USA rugby star Ilona Maher and gymnast Stephen Nedoroscik (aka “pommel horse guy”) tear up the stage in a new way. Eight-time NBA All-Star Dwight Howard and two-time Super Bowl champion Danny Amendola are also surprising the audience with their stellar footwork in a very different type of competition. It makes us wonder—which track athletes would dominate the dance floor?

In Dancing with the Stars (DWTS) history, 12 elite athletes have been crowned champion and taken home the Mirrorball Trophy—but the only track and field athletes who have participated in the show are former U.S. 100m world record holder Maurice Greene and American sprint hurdler (and bobsledder) Lolo Jones. Considering how much track and field athletes enjoy their celebratory dances (sometimes walking the fine line between celebrating and showboating), we think these five personalities would thrive in the ballroom.

Usain Bolt

We all know our favourite world-class sprinter’s signature victory pose became iconic for a reason–Usain Bolt knows how to make a statement. He became the 100m and 200m world record holder after coming from a 400m background, proving that he can be good at everything he tries. The confidence and vibrant energy Bolt brought to every track event throughout his career makes us certain he’d bring that same spirit to the dance floor.

If knowing Bolt’s captivating and charismatic personality when performing in front of a crowd isn’t already enough, here’s a video of him samba dancing after a press conference at Rio 2016. Clearly, he’s already a pro.

Alysha Newman

Canada’s Alysha Newman went viral for her celebratory dance after winning the bronze medal in the women’s pole vault at Paris 2024. The Canadian record holder cleared the bar, faked an injury–and started twerking. That’s exactly the energy they’re looking for when screening world-class athletes for potential dance skills. The technical expertise required in pole vaulting also gives Newman an edge when it comes to executing lifts or more challenging moves.

Newman got both positive and negative attention on social media from the victory twerk, but stayed confident and was true to herself–once again demonstrating that she is a qualified candidate for the show.

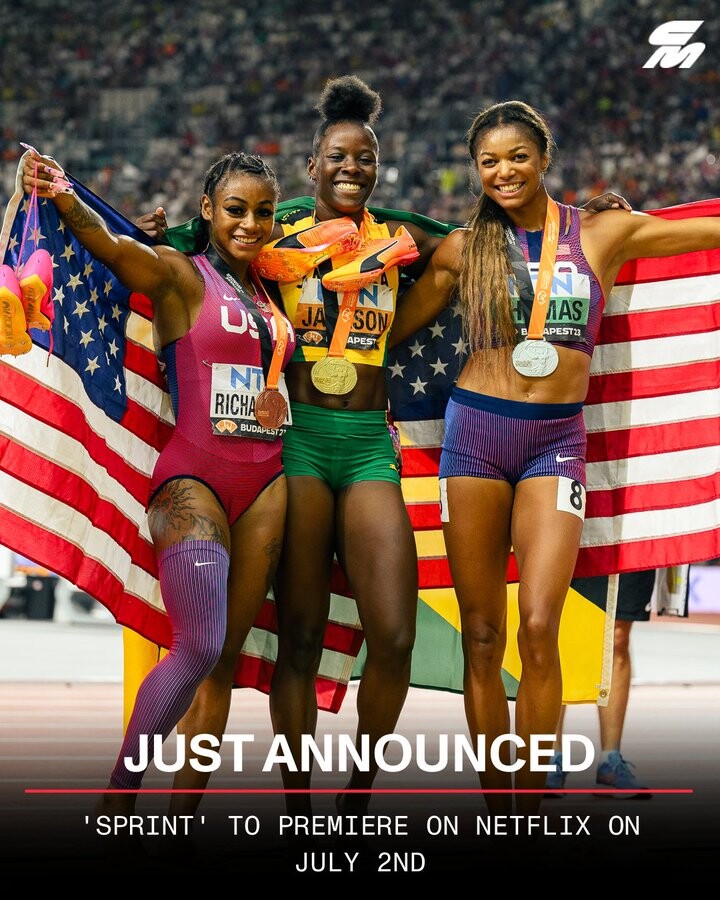

Noah Lyles

We’re sure the first person that came to mind when thinking of an athlete with a television personality was Team USA’s Noah Lyles. The 27-year-old, already a star on Netflix’s docuseries Sprint, exudes confidence and drive in each and every race he appears in. To say that Lyles is a competitive athlete might be an understatement–the 100m and 200m sprinter has quickly become popular for his bold moves even before races, in an attempt to rile up the crowd.

We’ve also seen this Olympic champion and six-time world champion dancing on TikTok. A character like Lyles could win over the audience on DWTS, and with those kinds of moves, he might even be a contender for the trophy.

Sha’Carri Richardson

Another major sprint personality we simply cannot leave out is Sha’Carri Richardson of the U.S. As you may know, the cast on DWTS gets dressed up glamorously for each show, and Richardson is the definition of glam. With her hair, nails, and lashes on race day, we know the 24-year-old would fully embrace the sparkly, embellished outfits worn during DWTS performances. Look good, feel good—right? Not to mention, like Lyles, this 100m world champion exudes confidence in every performance, a quality that would take her far in the ballroom.

Aaron Brown

Canada’s four-time Olympian Aaron Brown is not only a newly-minted Olympic gold medallist, but also an influencer. The 100m and 200m sprinter posts a mix of inspirational and humorous videos on his YouTube channels–showing off his fun and driven personality. With the current DWTS cast using TikTok and Instagram as a platform to build a fan base and earn more votes, Brown earns extra points as a potential candidate for already being experienced in that domain. We’ve yet to see his dancing abilities put to the test, but if put up against a rival like Lyles, we’re sure we can expect nothing but sensational moves from the four-time Canadian Olympian.

Honourable mention: Jakob Ingebrigsten

If he can bring these moves back, you can expect a nomination from us to get Ingebrigtsen on the next season.

by Running Magazine

Login to leave a comment

Usain Bolt has already made his feelings clear as second 16-year-old breaks his record

Olympic legend Usain Bolt has seen his sprint times beaten by youngsters Gout Gout and Nickecoy Bramwell in recent months, but he remains philosophical on his achievements being topped.

Usain Bolt has already made his feelings clear on young athletes breaking his records by declaring that he is excited by emerging "personalities" in the sport.

Following Nickecoy Bramwell's record-breaking feat earlier in the year, another record held by the Jamaican icon was smashed this week as 16-year-old Gout Gout produced a silver medal-winning time of 20.60 seconds in the 200m at the U20 World Championships in Peru. The young Australian narrowly edged out Bolt's 2002 time in the same race when he was almost 16 years old.

The Olympic legend clocked 20.61 in the final, although he had a quicker time of 20.58 in the first round. More than two decades on from Bolt's heroics, South African Bayanda Walaza clinched gold with a time of 20.54, while Britain's Jake Odey-Jordan secured bronze in 20.81.

Back in May, 16-year-old Jamaican hopeful Bramwell took Bolt’s Under-17 400m world record at the Carifta Games in Grenada with the youngster clocking 47.26 seconds to beat the record by just 0.07 seconds. Bolt's record had previously stood for an incredible 22 years.