Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #Strava

Today's Running News

Tshepo Tshite Rewrites South African History with Record-Breaking 3,000m Run in Ostrava

Tshepo Tshite could not have asked for a more emphatic start to his 2026 season. Under the bright lights of the Czech Indoor Gala in Ostrava on Tuesday night, the 29-year-old middle-distance star delivered a performance that etched his name even deeper into South African athletics history.

Lining up for the men’s 3,000m short track race, Tshite ran with confidence and control across the 15 laps, producing a superb time of 7:38.17. That effort not only secured him second place in a highly competitive field, but also shattered the South African national record. The previous mark of 7:39.55, set by Elroy Gelant in Belgium back in February 2014, was pushed firmly into the record books.

Victory narrowly slipped away by the finest of margins, as Portugal’s Isaac Nader crossed the line first in 7:38.05, just 0.12 seconds ahead of the South African. Still, the night belonged to Tshite, whose run stood out as one of the highlights of the meeting.

This latest achievement adds yet another chapter to Tshite’s growing legacy. He now holds four South African national records, underlining his remarkable consistency across middle-distance events. His previous national bests include the 1500m indoor (3:35.06), 1500m outdoor (3:31.35), and the indoor mile (3:54.10)—a rare and impressive collection that showcases both speed and endurance.

With the season only just underway, Tshite’s record-breaking performance in Ostrava sends a clear message: he is in top form and ready to challenge the very best. For South African athletics fans, this was more than just a fast race—it was a statement of intent from one of the country’s finest middle-distance runners.

by Erick Cheruiyot for My Best Runs.

Login to leave a comment

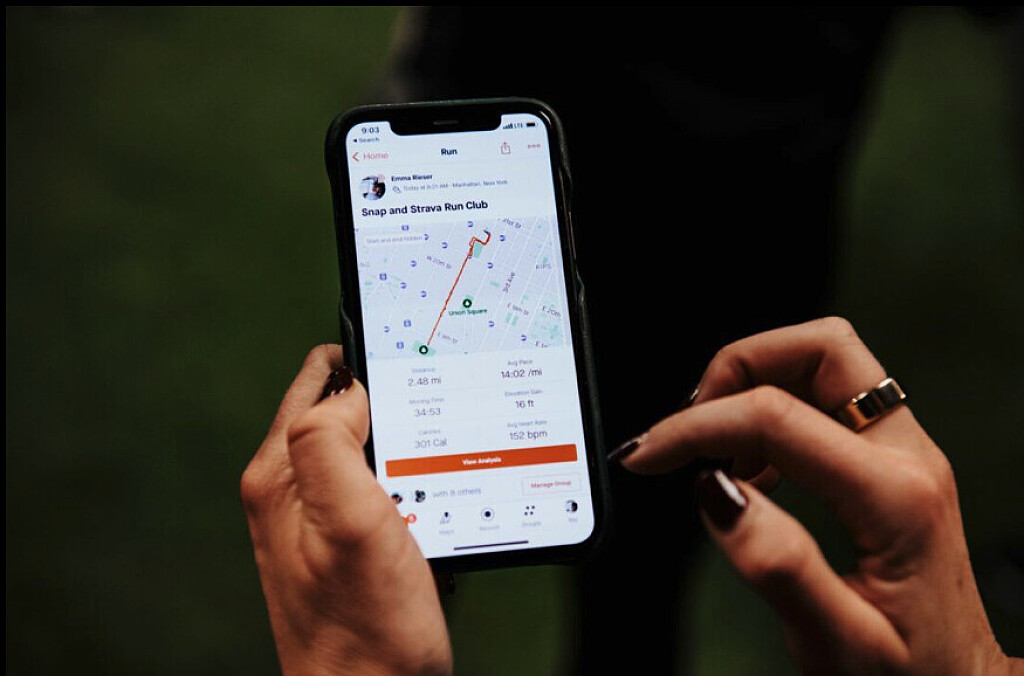

Strava Removes 4.45 Million Activities to Restore Integrity to Running Leaderboards

Strava just took a giant leap to restore trust in its running segment leaderboards—over 4.45 million activities have been purged from the platform.

Why such a massive cleanup? Many of those entries were either mislabeled as runs when they weren’t, or recorded while the user was riding in a car. For runners chasing KOMs (King of the Mountain) and segment PRs, this move is long overdue.

The platform’s goal is simple: ensure that leaderboard rankings reflect genuine human effort, not accidental car rides or mislogged workouts.

Earlier this year, Strava introduced a new machine learning system designed to catch these errors. It analyzes 57 variables—including speed, acceleration, and GPS patterns—to detect anomalies. Since launching in February, the system has led to a 72% drop in user-reported “vehicle” runs.

For runners who’ve trained hard and earned their spot on the board, this is a welcome correction. And for those who’ve lost segment crowns to impossible paces, justice has finally arrived.

Strava isn’t just removing suspicious data—it’s giving runners control. The system allows users to fix flagged runs by marking them private or deleting them entirely.

But that’s not all. Strava is continuing to enhance the experience for runners:

• AI-powered route suggestions tailored to your training goals

• Points of interest like restrooms and water fountains embedded into routes

• Seamless point-to-point navigation for longer or exploratory runs

Strava has also expanded its platform by acquiring The Breakaway, a performance-focused training app, signaling even more tools may soon be available for serious and recreational runners alike.

Bottom line: Strava’s leaderboards are becoming cleaner, smarter, and more accurate—which means segment records now reflect what they were meant to: real running.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

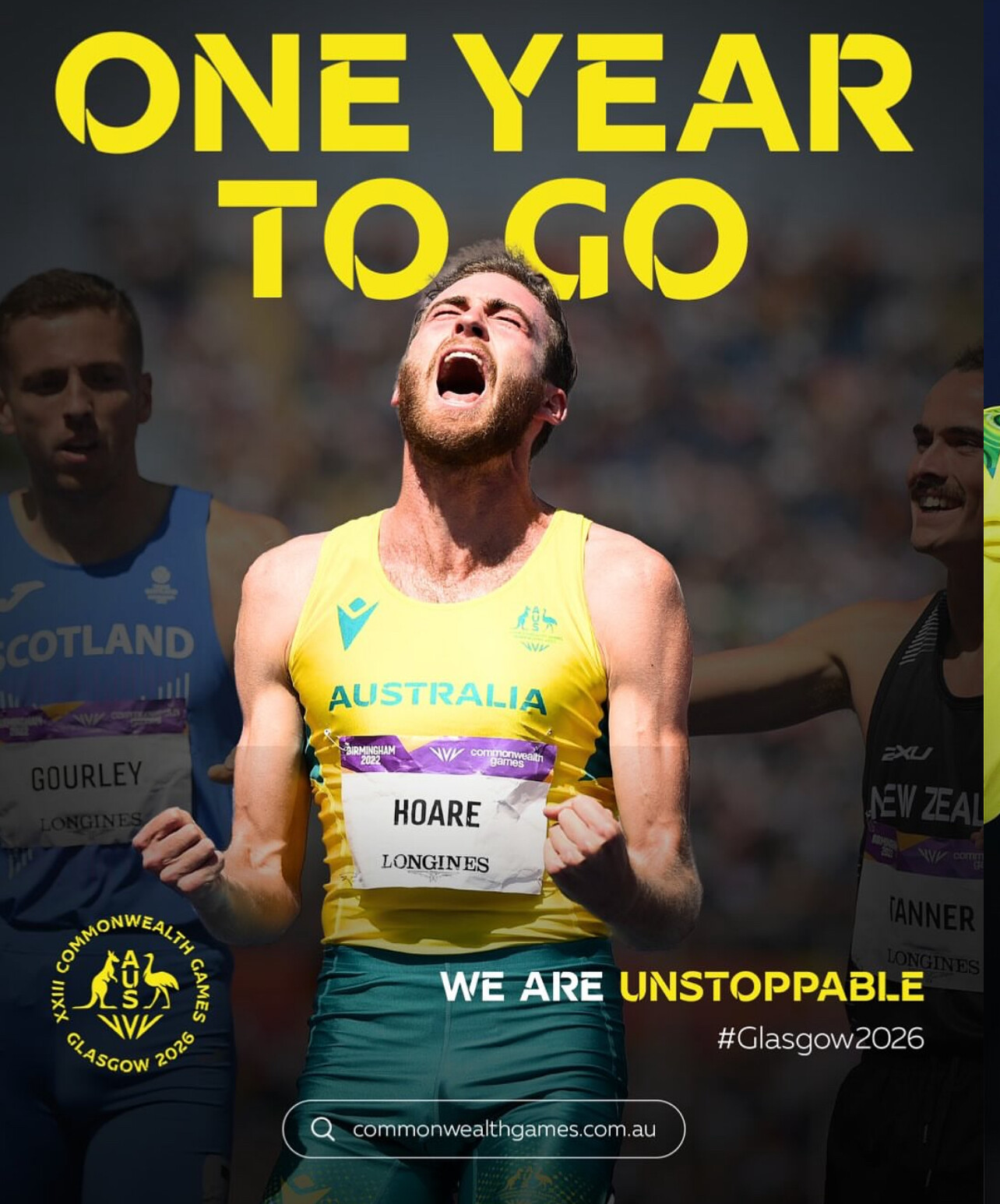

Australia’s teenage sprint sensation, Gout Gout, is gearing up for his biggest stage yet — the 2026 Commonwealth Games in Glasgow.

At just 17 years old, Gout Gout has already rewritten the record books. The Queensland-based sprinter, born in December 2007 to South Sudanese parents, is widely regarded as one of the most exciting young talents in global athletics. His rapid rise has drawn comparisons to legends like Usain Bolt — and for good reason.

Gout currently holds the Oceanian 200m record with a time of 20.02 seconds, set at the Golden Spike meet in Ostrava earlier this year. He also clocked 10.17 in the 100m to win the Australian U-18 title and later dominated the U-20 division. His combination of top-end speed, graceful stride, and fierce competitive drive has made him a must-watch on the world stage.

Now, the teen phenom is set to represent Australia at the 2026 Commonwealth Games, scheduled for July 23 to August 2 in Glasgow, Scotland. He is expected to compete in the 100m, while his entry in the 200m remains under consideration due to scheduling conflicts with the World Junior Championships, which will take place shortly after in Eugene, Oregon.

Gout’s Path to Stardom

Gout’s emergence as a global sprint force has been nothing short of remarkable. Raised in Ipswich, Queensland, he was introduced to athletics at a young age and quickly caught the attention of Australia’s elite coaches. Under the guidance of Diane Sheppard, Gout has developed into a technically polished athlete with a mature race strategy far beyond his years.

His silver medal at the 2024 World U20 Championships in the 200m confirmed what many already believed — Gout Gout isn’t just Australia’s future; he’s already one of its best.

Sheppard has praised his dedication, humility, and focus, noting:

“With Gout, it’s not just talent — it’s mindset. He’s willing to do the work and stay grounded.”

Glasgow 2026: A Games Reimagined

The 2026 Commonwealth Games will mark a return to Glasgow, which last hosted the event in 2014. Following Victoria’s withdrawal as host due to financial concerns, Glasgow stepped up with a streamlined, cost-efficient plan built on existing infrastructure.

The Games will feature:

• 10 core sports and 47 para-sport events

• Key venues including Scotstoun Stadium (track and field), Tollcross International Swimming Centre, and the Sir Chris Hoy Velodrome

• A strong focus on sustainability and legacy, with no new athletes’ village planned

Mascot “Finnie the Unicorn”, named after the Finnieston Crane and created by local students, has already captured hearts with its fun, distinctly Scottish vibe.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Jakob Ingebrigtsen Returns to Altitude Training in St. Moritz Following Injury and Personal Turmoil

Olympic champion Jakob Ingebrigtsen is heading back to the mountains of St. Moritz to resume altitude training after a difficult first half of the 2025 season marked by injury and family challenges. The 23-year-old Norwegian has been recovering from a strained Achilles tendon that derailed his early outdoor campaign and forced him to miss several key meets.

Recovery First

Ingebrigtsen initially planned to train at altitude in Sierra Nevada in the spring, but his Achilles issue required a change of course. He instead remained home to focus on recovery, missing high-profile events in Oslo, Ostrava, the Pre Classic, and the London Diamond League.

In a recent update shared on social media, Jakob acknowledged the long road back but said he was grateful for the time spent with his young daughter and dogs. “At least I had the best company,” he wrote, sharing photos from a forest outing. His message suggests a turning point in his recovery, both physically and emotionally.

Altitude Training in St. Moritz

Coach Filip Ingebrigtsen has confirmed that Jakob will now join Norway’s altitude group in St. Moritz for a three- to four-week training block. The plan is to carefully build back fitness without rushing into competition. If all goes well, Jakob could return to racing in mid-August, with the Silesia Diamond League meeting in Poland emerging as a likely target.

While his return has been delayed, confidence remains high. Ingebrigtsen’s indoor season earlier this year was exceptional—he broke the world indoor records for both the 1500m and mile. In June, shortly before his Achilles flare-up, he set a new European 1500m record of 3:27.95 and clocked 7:54.10 in the two-mile, a world best.

Personal Challenges and Legal Closure

In the midst of his recovery, Ingebrigtsen also had to navigate a difficult legal chapter. On June 23, his father, Gjert Ingebrigtsen, was convicted of minor assault against Jakob’s younger sister, Ingrid, for an incident involving a wet towel. Gjert received a 15-day suspended sentence and was ordered to pay damages. He was acquitted of similar charges involving Jakob due to lack of evidence.

The verdict marks a formal conclusion to a painful and public family dispute that first came to light in late 2023. With this chapter behind him, Jakob appears ready to shift focus fully back to his training and racing.

Looking Ahead

Jakob Ingebrigtsen’s approach to 2025 has been cautious but strategic. Rather than forcing an early comeback, he’s prioritized recovery, stability, and preparation. If his return to St. Moritz goes as planned, fans can expect to see him back on the track in top form later this summer—potentially just in time to contend for another global title.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

World Athletics Makes 300m Hurdles an Official Event

World Athletics has officially recognized the 300m hurdles as an official event, marking a major shift in the sport’s landscape. While it has long existed as a training and exhibition distance, the 300m hurdles will now count toward world rankings and all official statistical purposes, similar to the 400m hurdles.

In a statement released by World Athletics, the governing body noted:

“It will serve all World Athletics statistical purposes, including world rankings towards which it will score as a similar event to the 400m hurdles. A list of world best performances will be kept, while conditions for setting an inaugural world record will be decided at a later stage, once the popularity of the event has reached a meaningful level.”

Though not yet eligible for world records, the event already boasts elite-level performances. Norway’s Karsten Warholm—the 400m hurdles world record holder—blazed 33.26 in Oslo in 2021, a mark widely recognized as the world best. He followed it up with a 33.28 performance in Bergen last year.

On the women’s side, Dutch superstar Femke Bol holds the top time with her 36.86 run in 2022.

The move to formalize the event brings renewed attention to what has typically been a non-championship distance. A major showcase is already on the calendar: the men’s 300m hurdles will feature at the Oslo Diamond League on June 12, 2025, setting the stage for a high-profile showdown in Warholm’s home country.

With elite athletes already embracing the event and more high-level races on the way, the 300m hurdles may soon become a fan favorite—and a mainstay in international competition.

Photos: Karsten Warholm Sets 300m Hurdles World Record

Norwegian hurdler Karsten Warholm setting the 300m hurdles world record with a time of 33.26 seconds at the Impossible Games in Oslo.

Femke Bol Breaks Women’s 300m Hurdles World Record

Dutch athlete Femke Bol breaking the women’s 300m hurdles world record with a time of 36.86 seconds at the Ostrava Golden Spike event.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Athlos Returns Bigger Bolder and Ready to Make History

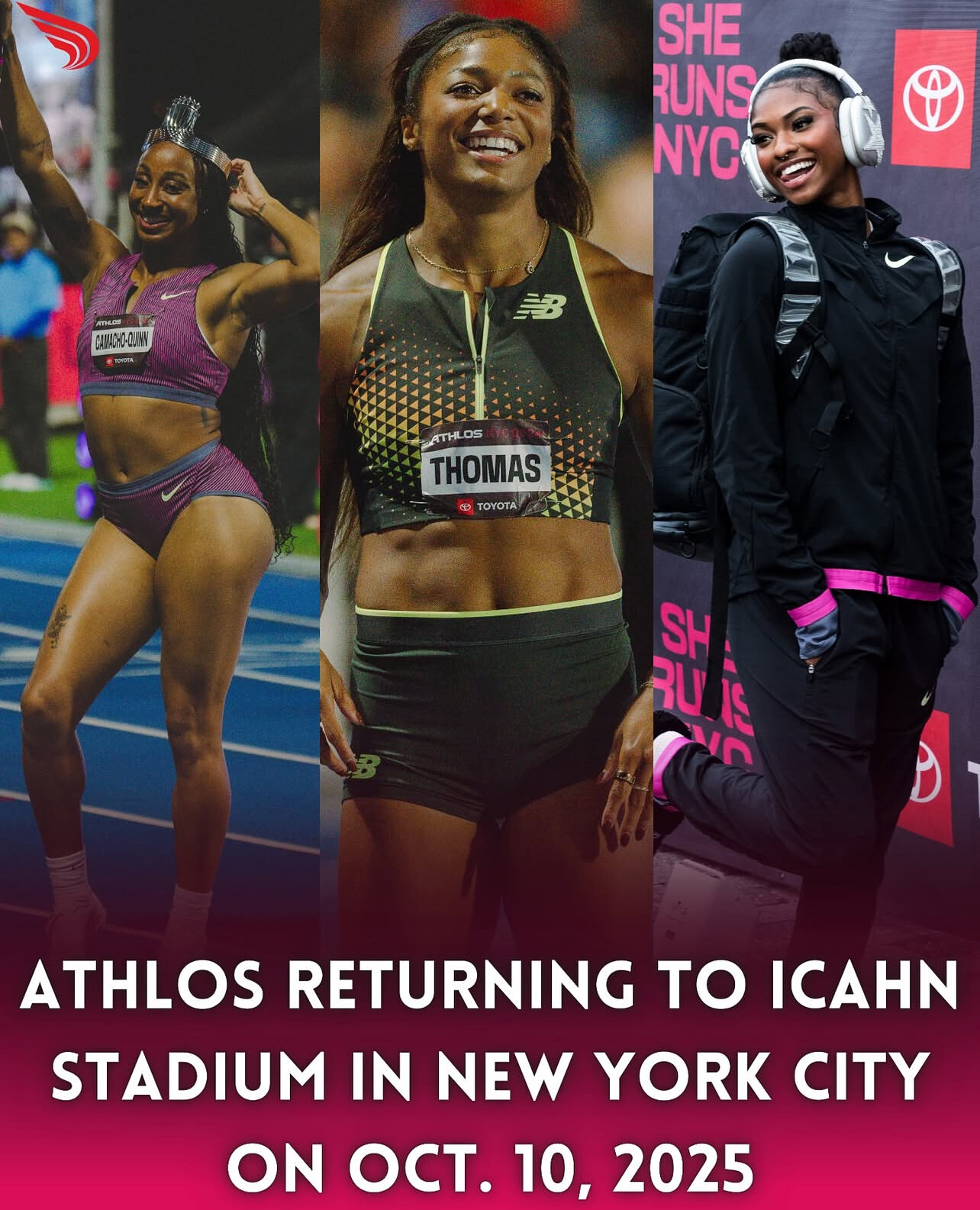

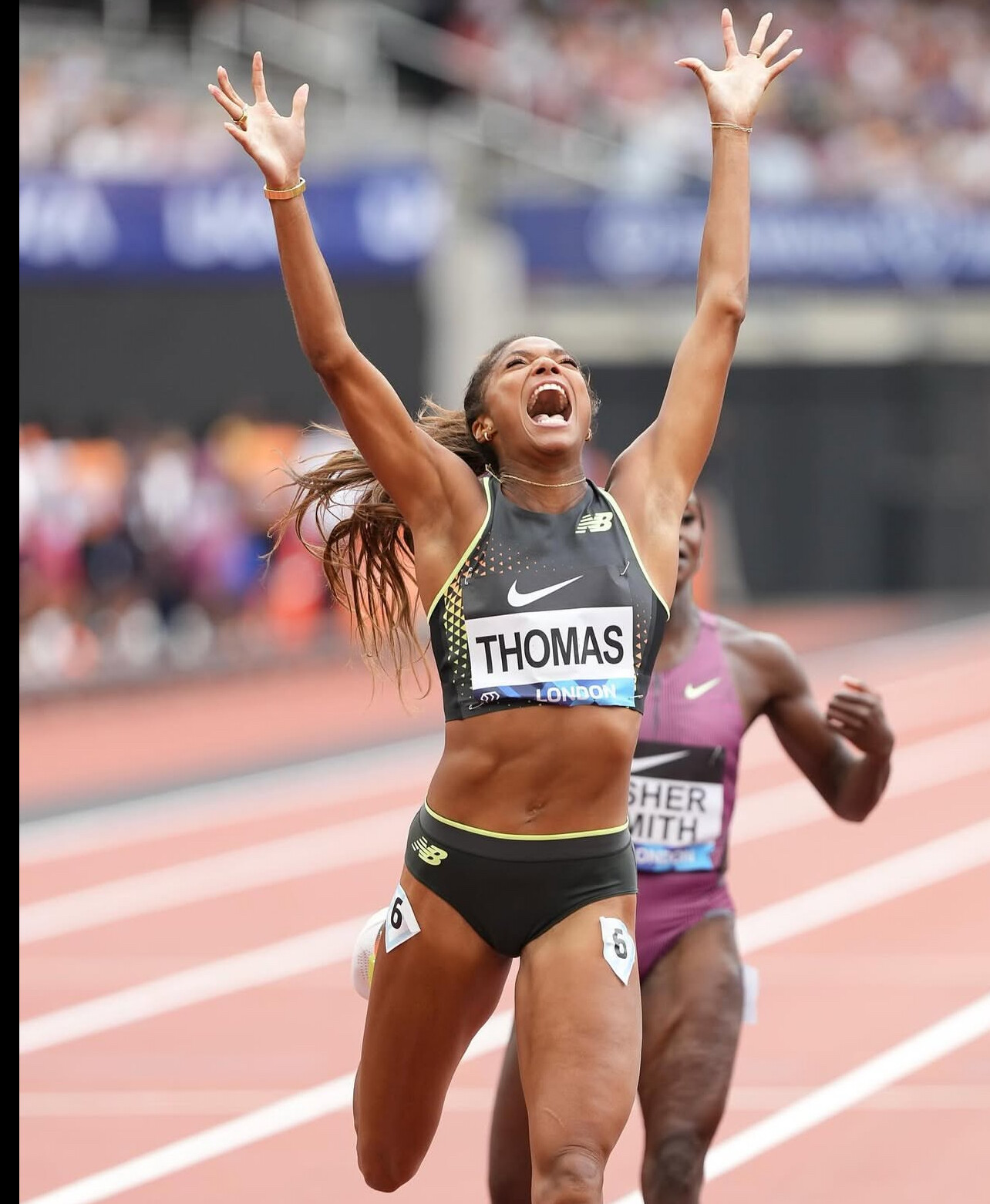

After a groundbreaking debut at Icahn Stadium in New York City, Athlos is set to return on October 10, 2025, promising an even bigger and better showcase of elite women’s track and field.

Last year, Athlos shattered records with a $663,000 prize purse—the largest ever for a women-only track meet. But it wasn’t just about the money. It was about recognition, opportunity, and redefining what’s possible for women in the sport.

Now, Athlos is ready to take it to the next level, backed by leading sponsors who are investing in the future of women’s track and field.

A Historic Debut That Changed the Game

When Athlos launched in September 2024, it wasn’t just another track meet. It was a statement.

The event featured world-class athletes competing in sprints, middle-distance races, jumps, and throws in front of a packed New York crowd. The performances were electric, but the real impact went beyond the finish line. Athlos challenged the status quo, proving that a women’s-only event could deliver the excitement, competition, and financial backing the sport has long deserved.

With a $663,000 prize purse, Athlos gave female track athletes the kind of financial opportunities typically reserved for men’s competitions. Media coverage soared, sponsorship interest grew, and conversations about pay equity in athletics intensified.

Athlos had arrived, and it wasn’t just a one-time moment—it was the start of a movement.

Sponsors Driving the Future of Athlos

Athlos’ success has been fueled by a growing lineup of sponsors that recognize the power and potential of women’s track and field. Last year’s meet was backed by:

• Toyota Motor North America – Presented the 100-meter hurdles event, highlighting its commitment to empowering female athletes.

• Tiffany & Co. – Designed custom sterling silver crowns for each event winner, bringing prestige and elegance to the competition.

• Oiselle – Served as the inaugural athletic apparel sponsor, aligning with Athlos’ mission to elevate women in running.

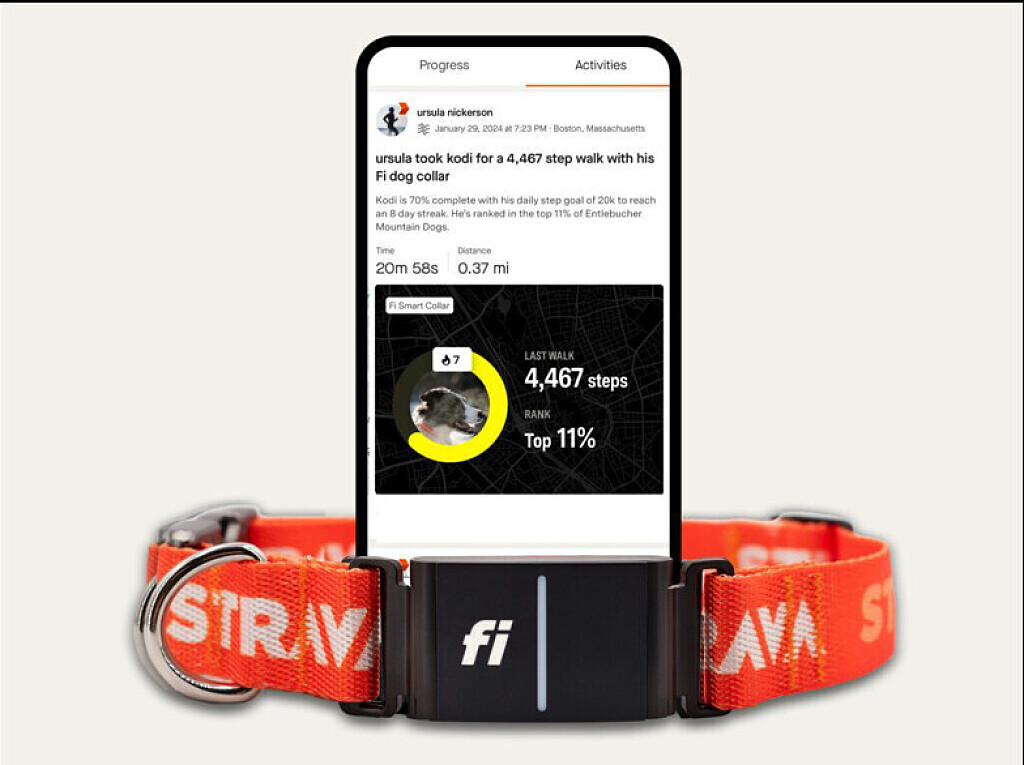

• Therabody, Strava, Champagne Telmont, and Wyn Beauty – Provided additional sponsorship, enhancing the event’s reach and profile.

With these industry leaders backing the meet, Athlos is proving that women’s sports are a worthy investment—one that is growing in value every year.

What to Expect in 2025

With its second edition set for October, Athlos is raising the stakes. While the full event lineup is yet to be announced, here’s what fans can expect:

• More Star Power – Last year’s event brought together elite talent from around the world, and 2025 promises to be even bigger, featuring Olympians, world champions, and rising stars, all competing for one of the largest prize purses in women’s track history.

• Increased Prize Money? – The record-breaking $663,000 prize purse in 2024 set a new standard. Will Athlos push it even further in 2025? Organizers have hinted at an even larger payout, solidifying the event as a premier financial opportunity for female track athletes.

• Expanded Events – Last year’s meet featured select disciplines, but 2025 could see more events added, giving a broader platform for top-tier competition.

• A Next-Level Experience – Expect enhanced fan engagement, including interactive digital content, social media activations, and upgraded live streaming coverage, bringing Athlos to a global audience like never before.

More Than a Meet, a Movement for Women’s Track

Athlos isn’t just about race results. It’s about reshaping the landscape for female athletes.

For too long, women’s track and field has received less prize money, fewer sponsorship deals, and lower media visibility. But things are changing—fast. From record attendance in women’s soccer and basketball to major increases in broadcast ratings and sponsorship investments, women’s sports are finally getting the recognition they deserve.

Athlos is part of this shift.

By creating a high-profile, high-stakes competition exclusively for female athletes, it’s proving that women’s track isn’t just equal—it’s a must-watch event in its own right.

Countdown to Athlos 2025

With just months to go, excitement is building for the second edition of Athlos. The event isn’t just returning—it’s evolving, growing, and setting new standards for women’s athletics.

More details on prize money, event lineups, and athlete participation will be announced soon. But one thing is clear: Athlos is here to stay, and its impact is only getting stronger.

How to Watch and Get Tickets

Athlos 2025 will be live-streamed globally, with tickets available soon for the in-person event at Icahn Stadium in New York City. Official updates will be posted on the Athlos website and social media channels.

The countdown has begun. Women’s track is taking center stage, and Athlos is leading the charge.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Run for Recovery: Join the Together LA Wildfire Relief Run on March 1

In response to the devastating wildfires that swept through Los Angeles County in January 2025, the Los Angeles Marathon has partnered with Strava to launch the Together LA Wildfire Relief Run. This virtual event, scheduled for Saturday, March 1, invites runners nationwide to support recovery efforts by logging miles on Strava and including “Together LA” in their activity titles. Strava has pledged a $20,000 donation to bolster the initiative.

Participants can further contribute by purchasing limited-edition Together LA merchandise, with all net proceeds directed to Community Organized Relief Effort (CORE) and the California Fire Foundation. These organizations are at the forefront of providing emergency relief and recovery services to the affected communities.

This collaborative effort underscores the resilience and unity of the running community, aiming to make a tangible impact in the lives of those affected by the wildfires.

For those unfamiliar, wildfires are uncontrolled fires that rapidly spread across vegetation, often exacerbated by dry conditions and strong winds. In regions like Los Angeles, these fires can cause significant destruction to homes and natural habitats, leading to substantial economic and environmental impacts.

Together, we run. Together, we rise. Together LA.

Login to leave a comment

Record-Breaking Performances Shine at Czech Indoor Gala in Ostrava

World indoor 1500m champion Freweyni Hailu delivered one of the fastest 3000m performances of all time at the Czech Indoor Gala—the fourth World Athletics Indoor Tour Gold meeting of the season—held in Ostrava on Tuesday (4).

Competing in just the third 3000m race of her career, the Ethiopian 23-year-old dominated with an 8:24.17 season opener, moving her to eighth on the world all-time list. Following a 2:52.08 split at 1000m and hitting 2000m in 5:45.8, Hailu surged over the final five laps, closing the last kilometre in 2:39 to secure victory.

Portugal’s Salome Afonso, who ran with Hailu in the early stages, finished second in a personal best of 8:39.25, followed closely by Kenya’s Purity Kajuju Gitonga in 8:39.36. Great Britain’s 18-year-old Innes FitzGerald shattered the European indoor U20 record by over 10 seconds, running 8:40.05 to claim fourth place.

The men’s 800m also saw a standout performance, with Belgium’s Eliott Crestan breaking the 1:45 barrier indoors for the first time, clocking a national record of 1:44.69 in his season debut. The world indoor bronze medallist improved on his previous best of 1:45.08 from last year’s World Indoor Championships in Glasgow, securing 12th place on the world all-time list. Italy’s Catalin Tecuceanu finished second in 1:45.35, while Algeria’s Slimane Moula, making his indoor debut, took third in 1:45.50.

In the women’s 800m, Gabriela Gajanova emerged victorious in 2:02.16, overtaking world indoor bronze medallist Noelie Yarigo in the final 150m as Yarigo faded in the closing stretch.

Meanwhile, Portugal’s Isaac Nader continued his dominance in Ostrava, setting his second consecutive meeting record with a 3:54.17 mile after breaking the 1500m record last year. He surged past Great Britain’s Elliot Giles in the home straight, with Giles finishing second in 3:54.62 in his first indoor race since 2022. Sweden’s Samuel Pihlstrom also made history, running a Swedish indoor record of 3:54.78 to place third.

With multiple meeting records shattered and world-leading times set, the Czech Indoor Gala in Ostrava reaffirmed its status as a premier stop on the World Athletics Indoor Tour Gold circuit.

Login to leave a comment

Anticipation Builds for Middle-Distance Showdowns at 2025 Czech Indoor Gala

The Czech Indoor Gala, scheduled for February 4, 2025, in Ostrava, is set to feature thrilling middle-distance races, particularly in the men’s 800 meters and the women’s 3000 meters.

Men’s 800 Meters:

Czech national record holder Jakub Dudycha will compete on home soil. As a junior, he set a national U20 indoor record of 1:47.42 at the Czech Indoor Gala, later improving it to 1:47.12. Outdoors, he advanced to the semi-finals at the European Championships in Rome, clocking a time under 1:45, and subsequently set a new Czech senior record of 1:44.82 in Bydgoszcz. Dudycha has expressed his ambition to break the national indoor record this season.

He will face formidable international competitors, including Belgium’s Eliott Crestan, who is the sixth fastest European in history with a national record of 1:42.43 set at the Paris Diamond League meeting. Crestan is a bronze medallist from both the European and World Indoor Championships. Another strong contender is Catalin Tecuceanu, representing Italy since 2022, who secured European bronze in Rome and boasts personal bests of 1:45.00 indoors and 1:43.75 outdoors.

Women’s 3000 Meters:

Kristiina Sasínek Mäki, a Tokyo Olympics finalist, will compete in the 3000 meters. She has been training under Swiss coach Louis Heyer and is eager to showcase her progress. However, she will face stiff competition from African athletes. Ethiopia’s Freweyni Hailu, the 1500m world indoor champion from Glasgow 2024, returns after setting a meeting record in the mile at last year’s Czech Indoor Gala. Joining her is compatriot Sembo Almayew, the junior world record holder in the steeplechase and World U20 champion, as well as Norah Jeruto, the World 3000m steeplechase champion from the 2022 Eugene Championships, now representing Kazakhstan.

The Czech Indoor Gala, part of the World Athletics Indoor Tour Gold series, continues to attract top-tier talent, ensuring a night of exceptional athletic performances in Ostrava.

Login to leave a comment

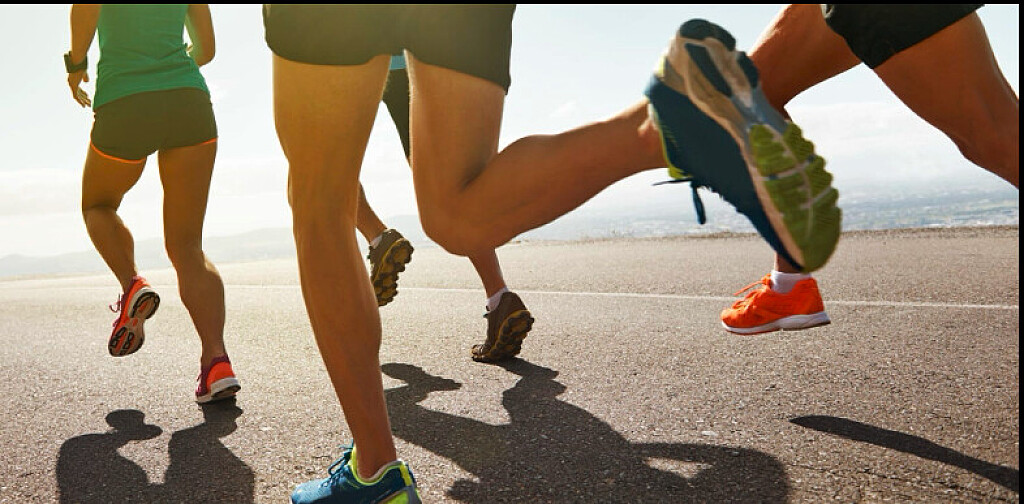

5 Reasons to run outside all winter—and get stronger, tougher, faster, healthier and happier

In the winter of 1939, when the military posted Swedish miler Gundar Hagg to the far north of that nordic country, he devised a unique training program of running on trails through knee- or hip-deep snow. Most days he would do 2500 meters in snow for strength, followed by 2500 meters on a cleared road for turn-over. But during those times when he couldn’t find cleared roads—sometimes for weeks—he’d run up to the full 5-kilometers in snow. The next summer he set huge PRs, coming within one second of the mile world record.

Hagg continued his routine in subsequent winters, devising a hilly 5K loop in a different locale that trudged through snowy forest for 3000 meters then ended with a 2000 meter stretch of road where he could run at full speed. He kept improving, and the summer of 1942 he set 10 world records between the 1500 and 5,000 meters.

While Hagg’s routine was created out of necessity, he obviously valued the snowy training. When he moved to a city with a milder climate, he wrote in a training journal, “It will be harder running than any previous year. Probably there won’t be much snow.” And every winter he scheduled trips north to train on the familiar, tough, snowy trails.

Hagg isn’t the only runner who has found winter training valuable. Roger Robinson, who raced internationally for England and New Zealand in the 1960s before setting masters road records in the ‘80s, recalls his training for the deep-winter English cross country championships of the 1950’s and 60s. “We ran, often at race pace, over snow, mud, puddles, deep leaves, ploughed fields, scratchy stubble, stumpy grass, sticky clay, sheep-poo, whatever, uphill and down,” Robinson says. “And thus, without going near a gym or a machine, we developed strength, spring, flexibility, and stride versatility that also paid off later on the road or track; I made one of my biggest track breakthroughs after a winter spent running long intervals on a terrain of steep hills and soft shifting sand.”

Robinson, now 85, with two artificial knees, still runs in the cold and slop. “Running is still in great part about feeling the surfaces and shape of the earth under my feet,” he says.

Hagg and Robinson are of a different generation than those of us with web-connected treadmills that can let us run any course on earth from the comfort of our basement, but they’re on to something we might still benefit from: winter can be an effective training tool. Here are five reasons you’ll want to bundle up and head out regardless of the conditions, indeed, why you can delight when it is particularly nasty out.

1) Winter Running Makes You Strong

As Hagg demonstrated and Robinson points out, winter conditions work muscles and tendons you’d never recruit on the smooth, dry path. A deep-winter run often ends up being as diverse as a set of form and flexibility drills: high knees, bounds, skips, side-lunges, one-leg balancing.

Bill Aris, coach of the perennially-successful Fayetteville-Manlius high school programs, believes that tough winter conditions are ideal for off-season training that has the goal of building aerobic and muscular strength. He sends the kids out every day during the upstate New York winter, and says they come back, “sweating, exhausted and smiling, feeling like they have completely worked every system in their bodies.”

2) Winter Running Makes You Tough

No matter how much you know it is good for you and that you’ll be glad when you’re done, it takes gumption to bundle up, get out the door and face the wintry blast day after day. But besides getting physically stronger, you’re also building mental steel. When you’ve battled snow and slop, darkness and biting winds all winter, the challenges of distance, hills and speed will seem tame come spring.

3) Winter Running Improves Your Stride

Running on the same smooth, flat ground every day can lead to running ruts. Our neuromuscular patterns become calcified and the same muscles get used repeatedly. This makes running feel easier, but it also predisposes us to injury and prevents us from improving our stride as we get fitter or improve our strength and mobility. Introducing a variety of surfaces and uncertain footplants shakes up our stride, recruits different muscles in different movement patterns, and makes our stride more effective and robust as new patterns are discovered.

You can create this stride shake-up by hitting a technical trail. But as Megan Roche, physician, ultrarunning champion, clinical researcher at Stanford and Strava running coach, points out, “A lot of runners don’t have access to trails. Many runners are running on flat ground, roads—having snow and ice is actually helpful, makes it like a trail.”

In addition to creating variety, slippery winter conditions also encourage elements of an efficient, low-impact stride. “One thing running on snow or ice reinforces is a high turn over rate and a bit more mindfulness of where your feet are hitting the ground,” Roche says. “And those two things combine to a reduced injury risk.” After a winter of taking quicker, more balanced strides, those patterns will persist, and you’ll be a smoother, more durable runner when you start speeding up and going longer on clearer roads.

4) Winter Running Makes You Healthier

“Exercising in general, particularly during periods of higher cold or flu season has a protective effect in terms of the immune system,” says Roche. You get this benefit by getting your heart rate up and getting moving even indoors, but Roche says, “Getting outside is generally preferable—fresh air has its own positive effect.”

Cathy Fieseler, ultrarunner, sports physician, and chairman of the board of directors of the International Institute of Race Medicine (IIRM), says there’s not much scientific literature to prove it, but agrees that in her experience getting outside has health benefits. “In cold weather the furnace heat in the house dries up your throat and thickens the mucous in the sinuses,” Fieseler says. “The cold air clears this out; it really clears your head.”

Fieseler warns, however, that cold can trigger bronchospasms in those with asthma, and Roche suggests that when it gets really cold you wear a balaclava or scarf over your mouth to hold some heat in and keep your lungs warmer. “Anything below zero, you need to be dressed really well and mindful of your lungs, making sure that you’re not exposing your lungs to too cold for too long,” Roche says.

5) Winter Running Makes You Feel Better

For all its training and health benefits, the thing that will most likely get most of us out the door on white and windy days is that it makes us feel great. “A number of runners that I coach and that I see in clinics suffer from feeling more depressed or a little bit lower in winter,” says Roche. “Running is a great way to combat that. There’s something really freeing about getting out doors, feeling the fresh air and having that outdoor stress release.”

Research shows that getting outside is qualitatively different than exercising indoors. A 2011 systematic review of related studies concluded, “Compared with exercising indoors, exercising in natural environments was associated with greater feelings of revitalization and positive engagement, decreases in tension, confusion, anger, and depression, and increased energy.” They also found that “participants reported greater enjoyment and satisfaction with outdoor activity and declared a greater intent to repeat the activity at a later date.”

That “intent to repeat” is important. Running becomes easier and more enjoyable, the more you do it. “Consist running is really the most fun running,” Roche says. “It takes four weeks of consistency to really feel good. Your body just locks into it.”

Most people associate consistency with discipline, and setting goals and being accountable is an effective way to build a consistent habit. Strava data shows that people who set goals are much more consistent and persistent in their activities throughout the year. The desire to achieve a goal can help overcome that moment of inertia when we’re weighing current comfort with potential enjoyment.

But the best way to create long-term consistency is learning to love the run itself. Runners who make it a regular part of their life talk little about discipline and more about how much they appreciate the chance to escape and to experience the world on their run each day—even, perhaps especially, on the blustery, cold, sloppy ones.

Login to leave a comment

Chipotle ends Los Angeles Strava challenge due to the wildfires

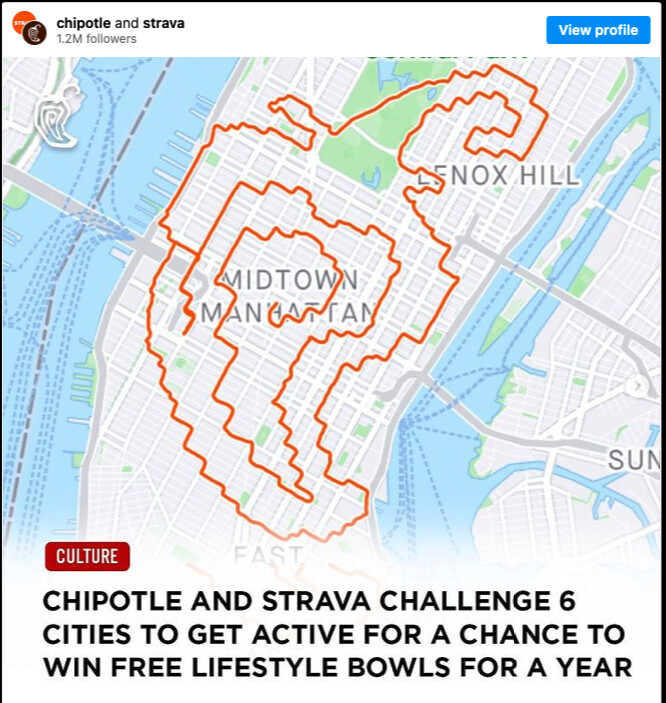

Chipotle’s January Strava challenge, offering runners a chance to win free Chipotle for a year, has come to a halt in Los Angeles as devastating wildfires forced the company to end the city competition early. With more than 180,000 residents evacuated due to fires in the city’s northwest, Chipotle decided it would be best to prioritize safety, and stopped the challenge at 11:59 p.m. PT on Thursday.The challenge was a hit in Los Angeles, which led to the global Strava x Chipotle City Challenge competition before the wildfires began on Jan. 7.

The challenge involves runners worldwide competing to become “Local Legends” by completing the most designated Strava segments during the month. The top individual in each participating city wins free Chipotle for a year, while cities collectively logging the highest mileage earn rewards like buy-one-get-one (BOGO) entrée deals for all residents.

Chipotle issued a statement explaining their decision: “Los Angeles, your health and safety is our greatest priority. Due to the devastating wildfires that are impacting the area, we are ending the Chipotle Los Angeles Segment Challenge at 11:59 p.m. PT on January 9, 2025. The Local Legend who has the greatest number of attempts at that time will be awarded with Lifestyle Bowls for a Year.”

Particles from wildfire smoke and other pollutants can be deadly and impact health. This is particularly concerning for runners, as intense outdoor exercise can aggravate the effects of airborne pollutants.

Brandon Fang of Del Rey, Calif., was named the winner after logging an incredible 284 efforts on the 330-metre segment (93.72 kilometres). On the final day of the challenge, Fang ran 12 kilometres on the segment in the morning, then returned later in the evening to run 50K after hearing about the early cutoff–all to secure a year’s worth of Chipotle.

While the Los Angeles competition came to an end due to the catastrophic fires, it continues in 24 other cities across North America and Europe (including Toronto). Runners in those cities still have a chance to win prizes and contribute to their city’s mileage totals.

Login to leave a comment

5 icky running habits to drop in 2025

The new year often comes with a wave of resolutions and the familiar chorus of “New year, new me.” Sure–sticking to these promises is much easier said than done, but it’s worth a try–especially when some running habits don’t deserve a spot in your 2025 plans. Here are five habits runners should ditch while striding into this fresh year of training.

1. Comparing your stats

Whether you’re racing your training partners during intervals or getting lost in a Strava rabbit hole chasing kudos, it’s time to pump the brakes. Running isn’t always a competition, and continuously pushing the pace can sour relationships with your running buddies. No one enjoys being dipped at the finish line of a workout, especially when they’re expecting a chill session.

Remember, comparing stats–be it heart rate or paces–won’t always reveal who is the better athlete. Everyone’s body and running style is different; the workout warrior might not be as strong on race day. Moreover, constantly comparing yourself to your peers will take a toll on your mental health. Focusing on your own progress can allow running to continue being fun and fulfilling.

2. Running through pain

We’ve all done it–brushing off pain as mere stiffness or a minor tweak. But pushing through is a fast track to injury. Your running buddies don’t want to hear your complaints now, and they’ll want to hear them even less if that tweak turns into a major setback.

Taking a day or two off, or even swapping out running for a bike ride or fast hike (i.e., cross-training) could save you from weeks on the sidelines. Listen to your body and leave running through pain in the past.

3. Not washing hats and headbands

Running hats and headbands, usually lost in the bottom of your bag, often get overlooked on laundry day, leaving you with a smelly accessory you’re too embarrassed to admit hasn’t been washed in weeks. It’s official: this is the year we show our headwear as much love as our shirts and shorts. You can even go as far as investing in a couple of extras to keep the rotation fresh; your scalp–and teammates–will thank you.

4. Forgetting sunscreen

Runners are notorious for skipping sun protection. Studies show that runners, especially marathoners, are at a higher risk for skin cancer, due to prolonged sun exposure. Make sunscreen as essential as your winter gloves and dry socks. Toss a bottle into your running bag so you’re always prepared–2025 isn’t the year for excuses.

5. Skipping strength

Complaining about injuries but skipping the weight room? That’s so last year. While strength isn’t as critical to performance for endurance athletes as it is for sprinters, it’s still a key ingredient for injury prevention–for all runners.

Building muscles that support and stabilize joints will help your body handle the repetitive impact of running. Strength isn’t a huge commitment, either; two to three brief sessions per week is the perfect way to invest in your longevity as a runner.

Login to leave a comment

How to review your running year so you can improve in the months to come

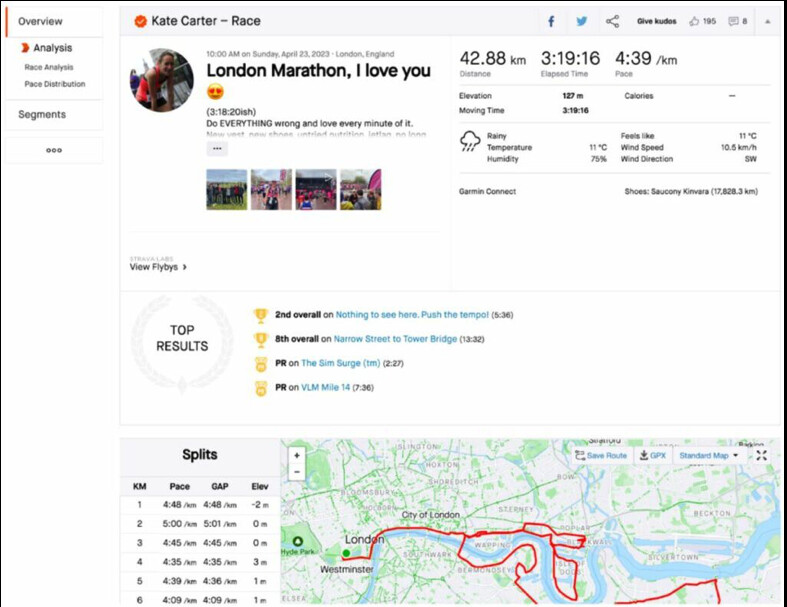

THE END OF THE YEAR IS A GREAT TIME TO reflect on your running over the past 12 months – whether your aim has been fun, achieving parkrun PBs or preparing for a marathon.

A year-end review can help you spot trends, address setbacks and enhance your training for the upcoming year – whether that’s to boost performance or increase enjoyment. To do this, I encourage you to conduct a light performance analysis. It doesn’t require extensive data; instead, ask yourself key questions to start the new year with focus.

Audit yourself

Begin by reflecting on your goal-setting from a year ago. What were those goals? Are they still relevant? Perhaps you achieved several PBs or completed a couch to 5K programme and need a new challenge. Alternatively, you might need to scale back this year if your previous goals were unattainable. Remember, running should be enjoyable, and it’s normal to experience ups and downs.

Then take a closer look at your training, racing and lifestyle over the past year. Use data, along with the self-reflection questions to follow, to score yourself from one to five in the areas identified. This will guide your goal-setting and action plan for the year ahead.

1. Physical

This covers your overall fitness, strength, endurance and injury prevention. If you’re more experienced, you might use data from apps such as Strava or Garmin Connect, or a detailed training log. This can include metrics such as mileage, heart rate or HRV measurements. For the performance-minded, consider lab testing such as lactate and VO2-max testing. If you’re less experienced, focus on how your rate of perceived exertion (RPE) might have changed in different training sessions and races as the year went on.

● Endurance Review your total volume over the year in distance or time. Were there gaps in consistency owing to injury, motivation or life events? Have you included longer runs regularly? Do you feel your heart rate or effort has reduced for similar paces, or are you able to sustain your pace for longer periods?

● Speed and power Analyse improvements in shorter races compared with longer ones. Use the RW race-time predictor to see if you align more closely on longer or shorter races, or if you are well balanced. Reflect on your training: did you include a mix of long runs, intervals, fartlek sessions, hill workouts, tempo runs and recovery runs? A well-rounded training plan leads to balanced improvement.

● Injury and strength Track how many injuries you’ve had, and their severity and causes. Has strength training supported your running? Use strength and flexibility tests such as knee-to-wall tests and sit-and-reach tests to benchmark yourself against norms for your age.

2. Planning and performance

This section looks at your approach to training plans and race performance.

● Race pace vs training pace Are you performing consistently in races compared with training? Do you feel you underperform or overperform in competitive situations?

● Variety Did you include races of different distances and on various surfaces throughout the year? Or did you stay in a comfort zone with your favourite or strongest type of race?

● Splits Evaluate how you pace yourself during races. Do you start too fast and fade, or do you

3. Mindset and wellbeing

Your mindset and emotional wellbeing play a significant role in your running performance, as well as in maintaining your motivation and consistency.

● Motivation and enjoyment Did you maintain enthusiasm for running or were there periods of low motivation? Identify factors that contributed to any highs and lows.

● Anxiety and pressure Did you regularly feel stressed or anxious about your running or performance? Consider your goal-setting and whether you have the right balance between process and outcome focus.

● Race nerves and focus Evaluate how you handled race-day pressure. Did you feel confident and focused or did nerves affect your performance? Assess your mental approach to tough runs and races – did you stay positive and push through challenging moments? Did you explore any mental techniques such as positive self-talk or mantras for key moments in races?

● Consistency and commitment Look at how disciplined you were with your training. Did you skip runs or stay consistent? What external factors affected your behaviour and how well did you handle those disruptions?

4. Recovery

You can follow the perfect plan with a good mix of training, but if you don’t recover, your fitness gains will be limited and you’re more likely to pick up injuries. Various pieces of data can help you monitor recovery, such as sleep tracking, heart-rate variability and the ‘recovery’ metrics from most GPS watches. Often, however, you’ll know if improvements are needed by answering some key questions:

● Sleep and rest Assess how well you prioritised rest, including sleep quality and duration. Poor recovery can lead to fatigue, injury and decreased performance, so reflect on how (or if) you balanced your hard training with adequate rest.

● Nutrition and hydration Did you fuel properly before during and after runs? Did you hydrate adequately, especially during long runs and races? Have you noticed patterns between nutrition and performance? Did you effectively plan and practise your race-day nutrition?

● Health and vitality Did you frequently catch colds or infections? In the run-up to key races, did you keep doing the simple things, such as using hand gel and taking any supplements you might need?

● Injury recovery Did you give yourself enough time to heal, follow rehab exercises and ease back

Write these down as a simple action plan with up to five priorities. Create objectives that are realistic and motivating, balancing short-term achievements – such as improving your pace or increasing weekly volume – with long-term ambitions, such as completing a marathon or getting a personal best.

Lastly, remember that running isn’t just about performance. Think about how to add enjoyment to your running, such as participating in races of different distances or on various surfaces. Consider joining a club or training group to maximise the social and mental health benefits of running.

Combining all of these lessons will help you get more from your running in 2025, whatever your goal may be. Good luck!

Login to leave a comment

You Failed Your Workout—Now What?

It’s Tuesday. No, it’s not only Tuesday. It’s critical velocity day. My coach has assigned me two warm-up miles and six by 800 meters in 3:13-3:21, with a 90 second jog between each one. I head out to smash the workout. I’m confident. I’m excited. Then, I start.

It’s blistering hot. Sweat is dragging all my face sunscreen down my forehead into my eyes. Water sloshes in my stomach. I’m so thirsty, but I can’t drink anymore or I’ll puke. I start to slow. Miss my paces. What is happening? My head spins and I get this horrible gut-wrenching feeling as I pull through the last interval. My coach is going to be disappointed. My Strava is going to be humiliating. Because I absolutely, undoubtedly failed this run.

Thinking of yourself or your run as a failure can be debilitating and keep you down for days. For a while, I thought I needed to stifle this feeling. But as it turns out, I should be making nice with failure rather than fighting it.

The ‘F’ Word: Failing a Workout

So what exactly does it mean to “fail” a run? It looks different for everyone, but to many runners it means missing the splits of your prescribed workout. You can fail in training and fail in a race—both can be disheartening. However, running coach and founder of Run Your Personal Best, Cory Smith, says this doesn’t always mean you’re running too slow.

“A lot of people think the faster you run, the better,” he says. “But if you’re trying to hit a certain zone or train a certain adaptation and you run too fast, then you’re training something different than your coach wanted you to train, that can be a failure, too.”

In fact, Smith doesn’t believe going slower than your prescribed paces should be defined as the typical, negative definition of failure.

“Failure is data collection,” he says. “It’s learning information. If I fail a workout, it doesn’t make me a failure as a person or an athlete, it’s just an opportunity to look at the data and figure out how to grow from it.”

Oftentimes you’ll hear runners call it the “F word” or scold others for talking about failure, but

“We have an opportunity, with our language, to normalize failure,” she says. “If we can redefine it, we change our relationship with it.”

What both Foerster and Smith stress the most is that one bad workout doesn’t make or break you. Smith compares it to basing your retirement fund on one day when the market went down, even though we know it goes up and down all the time.

“The most powerful thought around failure is that one workout never makes or breaks a race or athlete,” Foerester says. “We’re in a constant state of learning, if we open ourselves up to be.”

Beating yourself up over a workout can often bleed into your next run, creating a sort of downward spiral effect.

“It puts you into a negative mindset, and then the next workout you’re going to put more pressure on yourself to do well, to convince yourself that last workout was just a fluke,” Smith says. “This leads to anxiety, which can hurt your workout performance.”

One study reports that a negative emotional state can hinder athletic performance. Speed, specifically, was proven to be affected by emotional state. This study examined the correlation between sadness and depression and reduced running speeds, head movements, and arm swinging.

In other words, failure can be heavy, if you let it.

An Upsetting UTMB: Failing a Race

Like we said, failure looks different for everyone. So far, we’ve been talking about failing during training sessions—which can be referred to as process failure. An outcome failure, however, is not meeting an end-result or goal for which you trained. Like a race.

For Addie Bracy, it looks like an uncharacteristic 116th place in the 2023 CCC 100K last September. Bracy is an elite trail runner, winning the 2021 Run Rabbit Run 100 and placing third at the 2023 Speedgoat 50K. She has a consistent track record across the board and even has her masters in Sport and Performance Psychology.

“I had a pretty poor performance,” she says, reflecting on CCC. “Objectively, one of the worst I’ve ever had in trail running, and certainly not the race I trained for.”

Bracy says she can’t pinpoint a rhyme or reason why, but that it just wasn’t clicking that day. At a certain point, she realized the race wasn’t going the way she thought and reframed her mindset. Failure, in her definition, is only when you give up—and she chose not to.

“I think that’s the beauty of ultras—they’re so long that you’re going through the mental process then and there,” she says. “I had thoughts of stopping, but I went through the mentality of ‘That’s not why you do this,’ and gave my best effort to focus on just finishing instead of making a certain time.”

This is what Smith identifies as performance standards versus outcome goals.

“Outcome goals are the splits you or your coach sets or the final finishing time,” he says. “The performance standards aren’t outcomes, but how much effort you put into whatever that task is.”

Meaning, Bracy started with an outcome goal of a particular time, and mid-race, reframed her goals to do

Foerster goes a step further and says that failure is not only okay, it’s actually beneficial.

“Anytime we can meet emotional discomfort where we have to deal with heavy emotions like disappointment, we teach ourselves how to navigate that more effectively,” Foerster says. “So that when we meet another uncomfortable moment in a race, we know we can meet it and process through it.”

In a study conducted by Ayelet Fishbach, Behavioral Science professor at University of Chicago, and Kaitlin Woolley, associate professor at the SC Johnson Cornell College of Business, it was proven that discomfort could lead to personal growth. By applying cognitive reappraisal, study participants assigned a new meaning to discomfort before they experienced it so it served as motivation rather than a reason to stop their goals. And, in the case of this study, participants who were forced into discomfort while doing a task reported a greater sense of achievement.

Much like running itself can be uncomfortable, forcing yourself to address the emotions that come with failure can be an unfamiliar, disagreeable experience. But doing so allows you to feel, process, and recognize that you can change your relationship with failure every time you meet it.

“Discomfort is the currency to our dreams,” Foerster says. “If we’re willing to meet it, all our potential is on the other side.”

So miss those splits. Fail, and fail hard. Address the feeling head-on and don’t let it define you. It’s just one out of many more runs to come.

Login to leave a comment

Strava removes 6.5 million “impossible” performances from leaderboards

Is the popular fitness tracking app finally taking the necessary steps to catch cheaters?

You know that time you “accidentally” uploaded your bike ride as a run on Strava and found yourself launched to the top of the segment leaderboard? Well, the Strava police are out to get you. On Tuesday, the fitness tracking service introduced an upgraded algorithm to pre-emptively remove performances that are a little too good–including your impressive (and very impossible) three-minute mile run. The app also revealed they’ll be erasing 6,500,000 suspicious uploads from existing leaderboards upfront.

With 85 million segment efforts uploaded daily to the app, inspecting each performance thoroughly is hopeless. The service relies heavily on its users to report inaccurate or suspicious results in addition to its current filtration system, but millions of “impossible” activities still make their way past these existing lines of defence onto the leaderboard top 10. The new auto-flagging system is set to detect segment performances that are a little too good to be true before they even reach the leaderboards.

“This is BS! I was 30 seconds off [Kelvin] Kiptum’s world record and I only had to change tires once.” one user joked on Reddit.

Runs that are obviously completed on a bike and rides that are clearly logged from a car or e-bike will be the first to go. Strava runners have found the app’s uploads increasingly demoralizing–imagine running a mile-long segment in a best time of 4:30, only to find all 10 runs in the leaderboard are sub-four minutes and completed at a heart rate of 110 BPM.

Strava users have raised doubts on how thorough and effective this new algorithm will be–the service had already advertised upgrades to the flagging system in September and last year, but leaderboards saw little improvement. “This was announced over a year ago already and from what I can see, nothing has changed,” one user wrote. Numerous comments also address the need for an in-app flagging function; currently, Strava only allows users to flag suspicious activities through a web browser.

Other users are ecstatic at the chance to have an honest leaderboard and an actual shot at claiming the Local Legend title. “Yea Strava!” one user wrote. “Thanks for the acknowledgment and efforts to straighten out the issue. A big task to deal with, I know.”

“Brilliant news,” another comment reads. “If this also sorts out the challenges at the same time, that will encourage me to enter them again. Too many are blatantly cheating.”

Strava acknowledged they won’t be able to catch 100 per cent of cheaters, but says the added layer of filtration will help ensure that authentic performances and users get the recognition and the “kudos” they deserve.

by Cameron Ormond

Login to leave a comment

Strava users overwhelmed by notifications bug

If you’re one of the millions of Strava users who thought their app glitched after an avalanche of push notifications from people you forgot you followed, rest assured: your app is not broken. On Tuesday, Strava had a “Friends Activities,” a notification bug that alerted users every time someone they followed completed an activity.

From runs and rides to swims and walks, Strava is eager to notify you every time your connections move. Cue the flurry of notifications like: “Your friend just finished a ride!”, “Your friend just completed a run!”, or “Your friend crossed the street!” And don’t forget to give Kudos!According to Strava, all users experienced a bug this morning, (which has now been resolved). While the bug was praised with good intentions, users reacted negatively to it, finding the sheer volume of notifications overwhelming.

While it’s great to celebrate your friends’ accomplishments, not everyone appreciates their phone lighting up with 20+ alerts (especially those who follow triathletes, who log multiple activities a day). It didn’t take long for Strava users to take to X (formerly Twitter), with many questioning whether the app was broken or why they were suddenly bombarded with updates. Strava Support responded, advising users to adjust their notifications settings to regain control.How to turn off “friend” notifications

Open the Strava app.

Navigate to Settings.

Go to Push Notifications.

Under Friends, toggle off Friends Activities.

You’ll thank us later.

Login to leave a comment

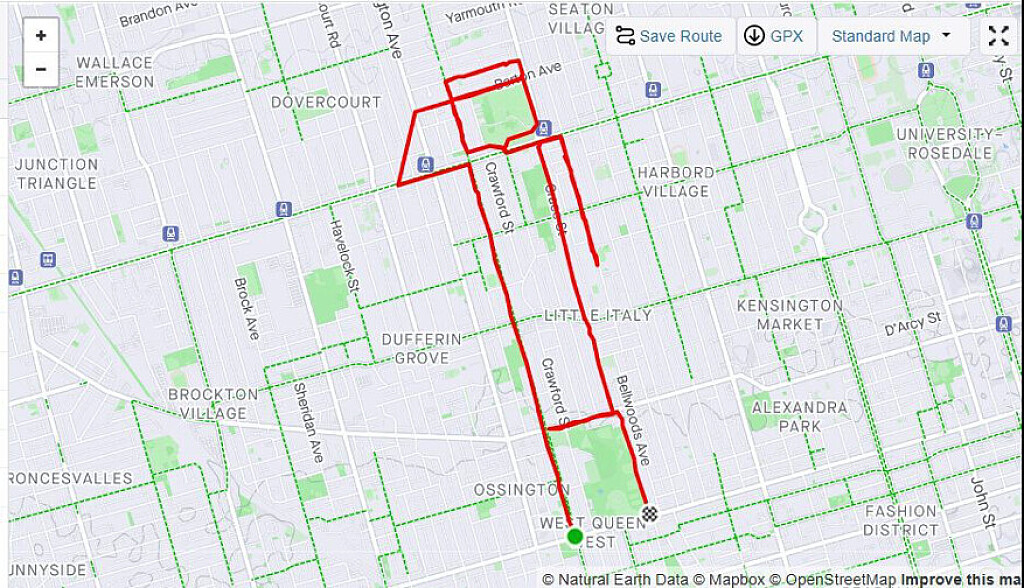

Toronto runner takes Strava art to the next level

Toronto-based accountant Duncan McCabe has taken Strava art to new heights. Blending his passions for video editing and running, he has created a viral TikTok featuring a mesmerizing animation of a Strava-art stick man.

As of Friday morning, McCabe’s dancing Strava video has garnered more than eight million views on social media.

We spoke to McCabe, the artist, who said he was surprised at the video’s viral success. He says he was inspired by San Francisco Strava artist Lenny Maughan and Toronto’s Mike Scott, who famously biked a GPS route of a giant beaver across the city’s east end. In 2023, McCabe created a series of animal drawings leading up to the Toronto Waterfront Marathon.

The 32-year-old explained the extensive planning behind his latest project, set to Sofi Tukker’s hit song Purple Hat. “For six months, I had a line across the stick person’s head that was used for animation,” McCabe said. “The hat-tip adds creativity and is a nod to the song.”

McCabe says the biggest challenge was maintaining fluid transitions. “My stick man had to be the same size in the frames,” he explained. “I mapped it out for 10 months.”

McCabe found motivation for the project by consistently seeing his progress and dates on his Strava. “It was the motivating factor for me,” he said.

With viral fame comes scrutiny, and McCabe has faced skepticism on X and TikTok about the video’s diagonal lines. “It’s believable right up until the stick man runs smoothly diagonally through a row of houses again and again,” one user commented.

However, the diagonal lines make his video even more impressive, as McCabe had to start and stop his watch to ensure the lines met precisely at certain points on the map.

Massive kudos!

Login to leave a comment

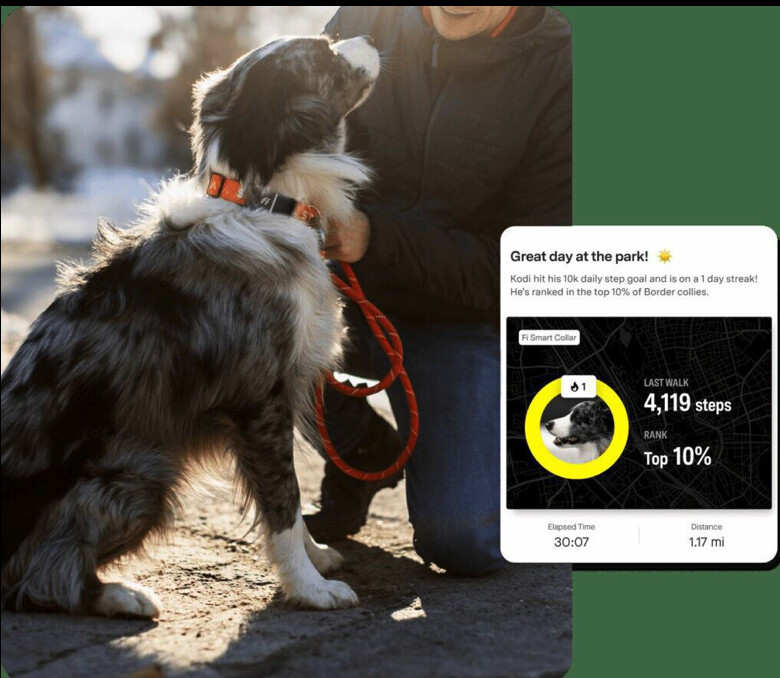

How Long Does It Take the Average Person to Walk 10,000 Steps?

All you need to know about setting aside time to meet this common goal.

Your fitness tracker probably tells you how many steps you take most days. And your device likely sets the goal of 10,000 steps a day or maybe that’s what you’ve entered as your daily step-count target. This number has become the popular goal for many people and for good reason: Moving more throughout the day is good for your body in numerous ways and it supports your mind, too.

In fact, every 1,000 steps a person takes each day lowers their systolic blood pressure (the top number) by about 0.45 points—that’s a good thing, especially for your heart! The more you move, the more likely you are to lower your risk of chronic illness, like cardiovascular disease, and support your mental health.

Now, if you’re wondering how long it takes to walk 10,000 steps so you actually meet this goal, we got you! Here, two exercise physiologists explain how long it typically takes to cover 10,000 steps, depending on your average pace, so you can carve out time for your body and mind to clock more movement.

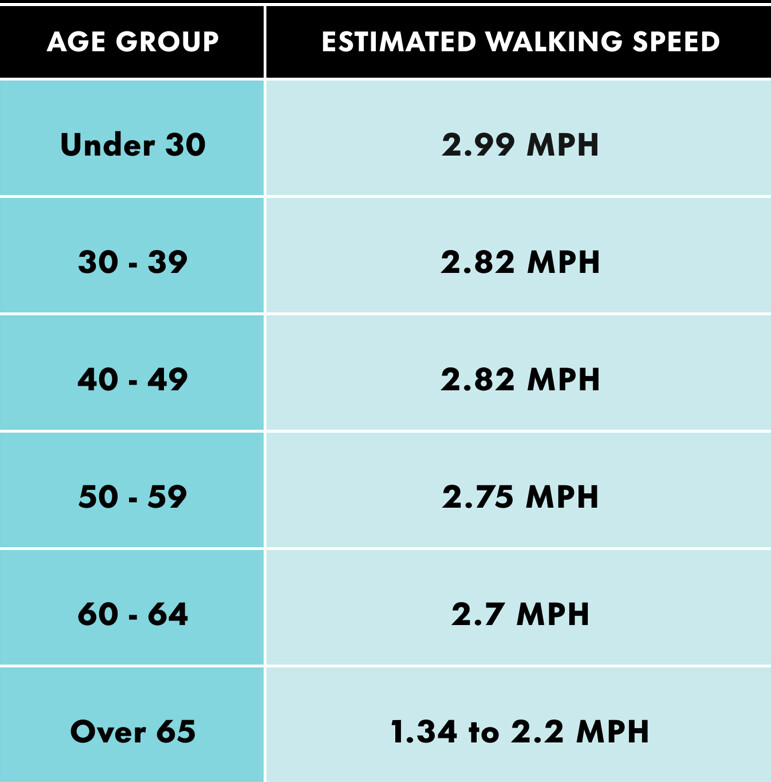

How long does it take to walk 10,000 steps?

For a person of average height (5-foot-3-inches for women and 5-foot-9-inches for men), a 2,000-step walk is about a mile, according to Laura A. Richardson, Ph.D., a clinical exercise physiologist and clinical associate professor at the University of Michigan School of Kinesiology.

This step count varies depending on the length of someone’s leg and the length of their stride, as well as their cadence. However, say it takes you 2,000 steps to cover one mile, and you walk at an average pace of about 20 minutes per mile, then it would take you about 100 minutes to walk 10,000 steps, Richardson explains Runner’s World. That’s one hour and 40 minutes.

Authors of a 2020 article published in Sustainability reviewed studies that examined walking habits in order to suggest ways to increase activity, and they came to a similar conclusion on timing. They found that healthy older adults typically average 100 steps per minute when moving at a moderate pace. This translates to about 100 minutes to clock 10,000 steps.

This will obviously change depending on your walking pace, though. If you walk a 15

The numbers change, of course, if you run some of those 10,000 steps, explains Rachelle Reed, Ph.D., an exercise physiologist, tells Runner’s World. Based on Strava, the average mile pace for American men is a 9:32 and 10:37 for American women. It would take those men about 47 minutes to take 10,000 steps and the women would need about 53 minutes to do the same.

How many calories do you burn per 10,000 steps?

To figure out how many calories you burn walking 10,000 steps, you need to know the metabolic equivalent rate (MET) for your exact pace. A MET is determined by multiplying the body’s oxygen consumption by bodyweight every minute. One MET is roughly equal to the amount of oxygen you consume at rest and is also equal to one calorie.

Following that equation, the National Academy of Sports Medicine says walking at a less than two miles per hour is equivalent to 2 METs per minute, which means someone who weights 150 pounds burns fewer than 140 calories per hour. Meanwhile, that same person walking at a brisk pace of approximately 3.5 miles per hour is equivalent to 4.5 METs, leading to a calorie burn of about 306 per hour.

Walking at a very brisk pace of four to six miles per hour is roughly equivalent to 5 METs, per the NASM. “It’s five times the amount of energy you need compared to rest,” Reed adds. Thus, you can burn around 340 calories per hour.

To put that in the context of 10,000 steps: Let’s say you walk about three miles per

How can you boost the benefits of your 10,000 steps?

To truly kick up the calorie burn, you have to change the intensity of your movement, which might mean adding in some running, walking at an incline on the treadmill, or walking up a hill, according to Richardson.

Reed suggests adding a weighted vest to your walks (or runs) a.k.a. rucking to increase the intensity level.

Finally, you may wonder if getting those steps on the treadmill is as beneficial as heading outside. There are pros and cons to both. “Pros of a treadmill are it’s easier to manipulate,” Reed says. “You can have complete control over the length of the intervals, the speed, and the incline much more easily there. But there’s also something to be said about getting your physical activity outside. There are additional mental benefits like stress relief and feeling more connected with your environment that people can gain from being active outside.”

Richardson agrees: “The nice thing about being outdoors is the sunlight, the fresh air, the different level terrain, depending on what type of surface someone’s walking on, that can engage different muscles,” she says. “So again, pros and cons to both. Really, choose

Login to leave a comment

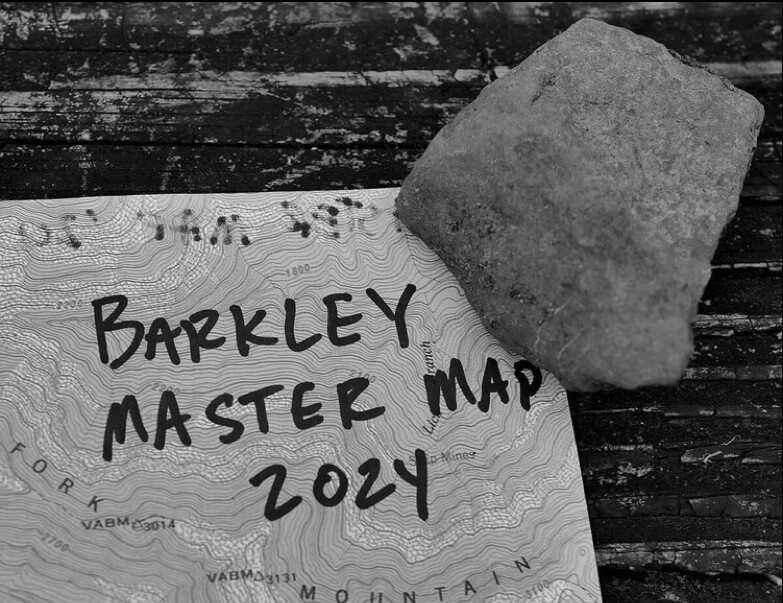

Runners have gone wild in the current boom, increasingly hitting the trails and embracing ultra distances

that immerse us in nature, where mile splits matter far less than the experience of respondents to a 2024 Runner’s World survey have run an ultramarathon.

65%

of those ran their first ultra in the past five years.

33%

said that they’re planning to run or considering running an ultra in the next two years.

‘It definitely feels more people are running trail and ultra, certainly post-Covid. The scene is really exciting with more races (and more accessible races), more brands, more sport-specific media, more younger, faster runners and more women – but they’re still a minority. Black Trail Runners and others are doing great work to make the scene more diverse. It’d be great to see more diversity, more accessibility and gender equality.’

Damian Hall, author and record-breaking ultrarunner236%

The year-on-year increase in internet searches for the Barkley Marathons from August 2023.

61%

of those surveyed by RW are interested or may be interested in following the big ultra races, such as the Barkley Marathons, Spine and Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc. 34%

This year’s increase in registrations for the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc World Series Finals, compared with 2023. Demand is two to three times higher than max capacity.

43

Events in UTMB World Series in 2024, in Asia, Oceania, Europe, Africa and the Americas.

$7.3 billion

The value of the global trail running shoes market in 2022, according to a report by Allied Market Research. Up from $1.38bn in 2016, according to data from Grand View Research.

$12.4 billion

Predicted value of the global trail running shoes market in 2032, according to Allied Market Research.

30%

Year-on-year increase in numbers for the Montane Spine races. ‘The Montane Spine has expanded with more races within the events and more locations. We’ve had to organise other races to keep up with demand because the Montane Spine races continue to consistently sell out. We’re seeing people looking for ultramarathons to help with their mental health.’

Phil Hayday-Brown, founder of the Montane Spine Race

63%

The year-on-year increase in participants at Black To The Trails, with a waiting list operating for 2024’s sold-out event. 58% of runners were people of colour, with 14 of the 19 UK ethnic categories represented; 70% of participants were women.‘The Black Trail Runners community continues to grow daily with thousands of followers in the UK and globally, we’re a registered community and campaigning charity with the mission to increase the inclusion, participation and representation of people of Black ethnicity in trail running. If you want to see a more ethnically diverse sector, you can join us to help us do that – you don’t need to be of Black ethnicity to support the work that we do.’

Sabrina Pace-Humphreys, ultrarunner and co-founder of Black Trail Runners

5,252%

Growth in trail races with 500 or more participants in the 10 years leading up to 2022, according to RunRepeat. 11%

The year-on-year increase in runners on Strava completing at least one ultra, according to 2024 Strava data, growing at the same rate for men and women.

10% year-on-year increase in 50Ks.16% year-on-year increase in 50-milers. 14% year-on-year increase in 100Ks.

1,676% increase in ultra participation between 1996 and 2018, according to a recent report from RunRepeat, with numbers rising from just 34,401 to 611,098.

5,590 races

on the International Trail Runners Association calendar between January and August 2024: a 458% increase from the 1,002 races planned a decade ago.

49%

of respondents to the RW survey who run on trails started trail running within the past five years.

231%

Growth in trail running worldwide in the decade leading up to 2022, according to RunRepeat research. ‘All our events have been sell-outs the last couple of years. The Tolkien Trail Race sells out 500 entries in under an hour, and we’re noticing races fill up quicker and quicker each year. Trail racing has the least barriers to compete, with less emphasis on times than road racing, which can be intimidating. There’s an element of adventure, a test of endurance and the release of being in nature that’s evidently being enjoyed across ages and genders.’

Chris Holdsworth, race director for Pennine Trailsitting the trails and embracing ultra distances that immerse us in nature, where mile splits matter far less than the experience

Login to leave a comment

Kilian Jornet summits 82 Alpine peaks in 19 days

On Monday, Spain’s Kilian Jornet, four-time UTMB champion and a legend in ski mountaineering and climbing, completed his monumental mountain challenge to summit all 82 Alpine peaks over 4,000m high in only 19 days. Jornet shattered the previous Fastest Known Time (FKT) of 62 days, set in 2015 by Swiss alpinist Ueli Steck, who used a combination of cycling and paragliding.

Following his remarkable 10th victory at the Sierre-Zinal race (where he beat his own course record by a single second), Jornet embarked on a quest, dubbed “Alpine Connections,” to ascend as many of the 4,000-metre peaks in the Alps as possible, using only human-powered methods to travel between them. This endeavour seamlessly combined trail running, mountaineering, climbing and cycling.

In 2023, Jornet took on his toughest challenges yet, summiting all 177 peaks over 3,000 metres in the Pyrenees in just eight days. Reflecting on the feat at the time, he called it “one of the most difficult things I’ve ever done.” With the “Alpine Connections” project, Jornet pushed his limits even further as he continued to use only running or cycling between mountains, being careful to leave no trace that he was there.

Jornet started his journey in the Bernina range of eastern Switzerland. In just a few days, he conquered 10 peaks, covering 423 km with a staggering 19,831m of elevation gain. The early stages of the challenge tested both his physical and mental endurance, and Jornet worked closely with scientists to track the physical and mental demands of his trek. He also provided daily recaps, stats and tracking on the Nnormal blog, Strava and @nnormal_official.

Jornet faced other, more humourous challenges during his journey: at one point, police threatened to tow his vehicle when work needed to be done on the parking lot he had left it in—2,500km away, and 4,000 metres below him.

Upon reaching the summits of Dôme and Barre des Écrins (the westernmost peaks in the series) on Instagram, Jornet shared his thoughts on Instagram. “This was, without any doubt, the most challenging thing I’ve ever done in my life, mentally, physically, and technically, but also maybe the most beautiful.”

“It’s difficult to process all my emotions just now, but this is a journey that I will never forget. It’s time for a bit of rest now.”

by Keeley Milne

Login to leave a comment

Rampaging Edmonton Marathon runner claims he was drugged with meth

On Sunday, Aug. 18, thousands of runners took to the streets for the 2024 Servus Edmonton Marathon, marking the largest event in the marathon’s 33-year history. However, the event was marred by a disturbing incident involving a University of Alberta student who was detained by police after allegedly assaulting other marathon runners at the 27 km mark. Days later, the student/runner shared his side of the story on Reddit, alleging that he was drugged with methamphetamine shortly after the race began.

The runner’s story

In a detailed statement, the runner recounted being low on sleep, anxious and rushed as he arrived late to the marathon. Just minutes into the race, he says he took water from what he thought was a legitimate water station. It was at this moment that he suspects he was drugged.

He described how his condition quickly deteriorated after consuming the drink. His stomach became uneasy, his heart rate spiked and breathing became difficult—symptoms highly unusual for someone running at his usual training pace. By the halfway point of the marathon, he recalls his memory fading. Data from his Strava activity indicated that his path grew erratic, and several witnesses later reported seeing him running shirtless, screaming and obstructing other participants.

The runner said he has no memory of these actions but vividly recalls the terror he felt as the police on the course detained him, resulting in physical injuries including cuts, a concussion and a sprained wrist. Race director Tom Keogh confirmed that the runner was detained about two and a half hours into the race, just after the 27 km mark. “Our medical team and police on-site responded quickly and appropriately,” Keogh said in an interview. “He appeared fine in post-race photographs and was even seen flashing a peace sign to the camera around the 10-kilometre mark [58 minutes into his race].”

The police report

The runner described his arrest experience as traumatic, involving a bag over his head, a cold concrete cell and wavering confusion. According to the Edmonton Police Service (EPS), he was released around 2 p.m. on Aug. 18, dazed and without a clear understanding of what had happened. He was then dropped off at his home. It wasn’t until the following day that he visited the hospital, where he claims he was informed that he had been drugged with methamphetamine.

EPS provided a detailed account of their interaction with the runner, explaining that they responded to multiple reports of a man behaving aggressively on the marathon route and assaulting other runners. Due to his erratic behaviour, which included spitting and kicking at the police cruiser windows, officers restrained him and applied a spit mask before transporting him to the Detainee Management Unit. The runner questioned why he was not assessed for drug intoxication at the time, the police believed his behaviour to be related to intoxication or mental health issues. No charges were laid.

EPS stated that they are continuing to investigate the reported assaults against other race participants, as one victim has filed a formal complaint. The EPS says they have not received any other reports of drugging along the race route. They also noted that there has been no evidence of a fraudulent water station, as claimed by the runner.

Keogh dismissed allegations of widespread drugging at the marathon, stating that other medical cases during the event were related to dehydration and heat, with no other suspected drug incidents reported. He encouraged the runner to file a formal complaint with the police if he wished to pursue the matter further.

Methamphetamine can have dangerous and unpredictable short-term mental and physical effects, which typically last eight hours but can sometimes extend up to 24 hours, depending on the method of consumption. According to Health Canada, the drug’s effects are felt within seconds if injected or smoked, and within 20 to 30 minutes if taken orally.

The runner’s motivation for posting his story on Reddit appears to be driven by a sense of bewilderment and embarrassment over his experience. Canadian Running has been in contact with the runner (who has not been named in this article due to privacy); he has not been able to verify any aspects of his account. “This has been one of the most frightening and dehumanizing experiences of my life. I’m deeply frustrated by the lack of support from the Edmonton Marathon organizers and the way the police treated me,” the runner says.

by Running Magazine

Login to leave a comment

Skeezy New Trend: Strava ‘Surrogates’ Are Making Money by Logging Runs for Other People

Want to make some money on your next run? An Indonesian teenager has found a lucrative way to do just that by, well, running for other people.

Wahyu Wicaksono, 17, has become what’s known in the country as a “Strava jockey,” logging running achievements for others on the app for a fee.

“I am active on X and it is booming there,” Wahya told Channel News Asia. He charges 10,000 rupiah (about 62 cents) per kilometer for running at a “Pace 4” (one kilometer in four minutes). For a more leisurely “Pace 8” (one kilometer in eight minutes), the fee is 5,000 rupiah per kilometer. Clients pay upfront, and Wahyu tracks his runs by logging in to the buyer’s account. elling data from runs or bike rides has gone viral in Indonesia. Another Strava jockey who spoke to CNA is 17-year-old Satria, who charges 5,000 rupiah per kilometer. “I have taken part in marathons before, so running is my hobby. I’ve got nothing to lose,” he told the outlet.

Except maybe his Strava account.

“Strava’s mission is to motivate people to live their best lives. Part of the platform’s magic comes from the authenticity of our global community in uploading an activity, giving kudos, or engaging in a club,” Linh Le, Strava’s director of corporate communications, told Runner’s World, adding that sharing accounts or credentials is a violation of the app’s terms of service. “This is important to safeguarding and respecting the progress and work of our athletes as they lace up every day.”

Strava has more than 100 million subscribers across 190 countries, but the publicized trend seems largely isolated to Indonesia for now. Still, with the ever-increasing desire for validation in the form of likes and other engagement, it doesn’t seem outside the realm of possibility that overworked runners desperate to “earn” that final segment might pay a fast neighborhood kid to crank out some miles on their behalf.

After all, as Strava’s motto goes, “If it’s not on Strava, it didn’t happen.” elling data from runs or bike rides has gone viral in Indonesia. Another Strava jockey who spoke to CNA is 17-year-old Satria, who charges 5,000 rupiah per kilometer. “I have taken part in marathons before, so running is my hobby. I’ve got nothing to lose,” he told the outlet.

Login to leave a comment

Experts Say You Should Ditch the Watch at Least Twice a Week and Run Based on Feel—Here’s Why

It’s time to incorporate more effort-based training into your schedule.Running is both an art and a science in many ways, and sometimes, you choose whether you want to lean into the former or the latter. Such is the case when running by feel (art) or pace (science).

Running by feel is also known as effort-based training or going by your rate of perceived exertion (RPE). “We define perceived exertion as your own subjective intensity of effort, strain, discomfort, or fatigue that you experience during exercise,” says Luke Haile, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Department of Health and Exercise Science at Commonwealth University of Pennsylvania. Your RPE is affected by numerous factors, from your emotional state to the weather to how well you slept the night before. “When you can understand it, it can really guide your training,” Haile says.

The easiest way to look at running by feel is on a scale of one to 10 (although some versions of RPE go up to 15 or 20), says Greg Laraia, a running coach at Motiv in New York City. One means you’re exercising with barely any effort at all while a 10 would be an all-out, can-barely-breathe effort. In practice, this looks like heading out to run at a six or seven for your easy runs (rather than at, say, 10-minute mile pace).

If you know your body and your paces well, you can also run by feel sans RPE scale and just going off what an eight-minute mile ~feels~ like, for example. Experienced runners can get so good at knowing how a particular pace feels to them that they don’t even need the feedback from tech—they can simply decide that they want to run eight-minute miles and, more or less, nail it.

But can ditching your watch and running by feel versus pace still get you to your goals? Read on to find out the pros and cons to both approaches, and how to know which is best for you. (Spoiler: Most likely, you’ll want to integrate a mix of both metrics!)

Pros of Running By Feel

“The real gift of running by feel is [that it’s] almost a mindfulness practice that, with training, allows you to feel how the body is in that moment and to take notice of how your feet feel, how your calves feel, down to your heart rate, breathing, noticing your sweating, and knowing what it feels like when you are at the right pace for a given goal,” says Haile.

The more in tune you get with your body and learn to listen to it, the more you learn when you have more to give to a run or when there’s something lurking under the surface, like an injury coming on, that isn’t allowing you to reach your full potential, Haile adds.

Because of this, running by feel can help reduce your risk of injury or burnout, says Laraia. If you have a “bad” day but your training plan says you need to run at a higher heart rate zone or a particular pace, you might push yourself to hit that and overdo it. But if you’re running by feel, you keep your pace and heart rate in check (because it feels challenging enough).

Cons of Running By Feel

For starters, running by feel may not be as accurate for novice runners: Haile and his team have conducted a number of experiments around RPE in both recreational and more experienced (not necessarily fast!) runners.