Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #World Anti-Doping Agency

Today's Running News

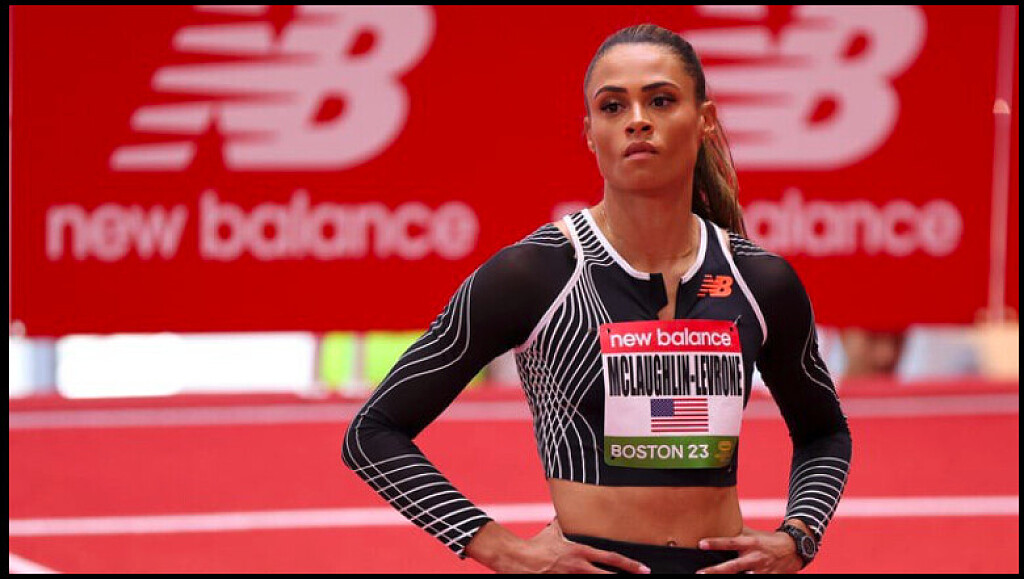

Doping Dilemma: How WADA's Policies Are Failing Our Sport

I am alarmed by how the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) is policing our sport. It's disheartening to see athletes win races only to be stripped of their titles months later due to delayed doping allegations. This approach undermines the integrity of athletics and, in the long run, does more harm than good.

Having dedicated my life to running—I ran my first mile on February 16, 1962, and I discovered my passion for our sport after clocking a 2:08.5 in a 880-yard race JUne 1, 1963—I've witnessed the sport's evolution firsthand. As the founder and publisher of Runner’s World for 18 years and, since 2007, the editor and publisher of My Best Runs, I am concerned about the professional side of athletics.

The Flaws in WADA's Zero-Tolerance Policy

WADA's strict liability standard holds athletes accountable for any prohibited substance in their system, regardless of intent. This has led to controversial sanctions, such as the four-year ban of American runner Shelby Houlihan. She tested positive for the steroid nandrolone, which she attributed to consuming a pork burrito. Despite her defense, the ban was upheld, raising questions about the fairness of such rigid policies.

Overhauling the Banned Substances List

The extensive list of prohibited substances maintained by WADA includes compounds with minimal or no performance-enhancing effects. By focusing on substances with proven performance benefits, we can prevent athletes from being unjustly penalized for trace amounts of inconsequential substances.

The Problem with Retroactive Disqualifications

Delayed disqualifications due to retroactive positive tests cause significant disruptions. Athletes are stripped of titles months or even years after competitions, leading to uncertainty and diminished trust in the sport. Investing in faster, more sensitive testing methods is crucial to detect violations promptly, ensuring that competition results are reliable and fair.

Rethinking the "Whereabouts" Requirement

WADA's "whereabouts" rule mandates that athletes provide their location for one hour each day to facilitate out-of-competition testing. This constant monitoring infringes on athletes' privacy rights and imposes an unreasonable burden. Reevaluating this policy could help balance effective anti-doping measures with respect for personal freedoms.

Understanding Blood Doping and Its Implications

Blood doping, which involves increasing red blood cells to enhance performance, poses significant health risks, including blood clots, stroke, and heart attack. While it's linked to deaths in sports like cycling, there is no documented case of a runner dying directly from blood doping.

Interestingly, many doping violations involve substances like erythropoietin (EPO), which, despite health risks, haven't been directly linked to fatalities among runners. In contrast, alcohol—a legal substance—is responsible for approximately 3 million deaths worldwide annually. This disparity raises questions about the consistency of current substance regulations in sports.

The Business of Anti-Doping

Established in 1999 with an initial operating income of USD 15.5 million, WADA's budget has grown significantly, reaching USD 46 million in 2022. This increase reflects the expanding scope of WADA's activities, including research, education, and compliance monitoring.

Funding is primarily sourced from public authorities and the sports movement, with the International Olympic Committee (IOC) being a major contributor. Notably, in 2024, the United States withheld over USD 3.6 million—about 6% of WADA's annual budget—due to disputes over the agency's handling of doping cases.

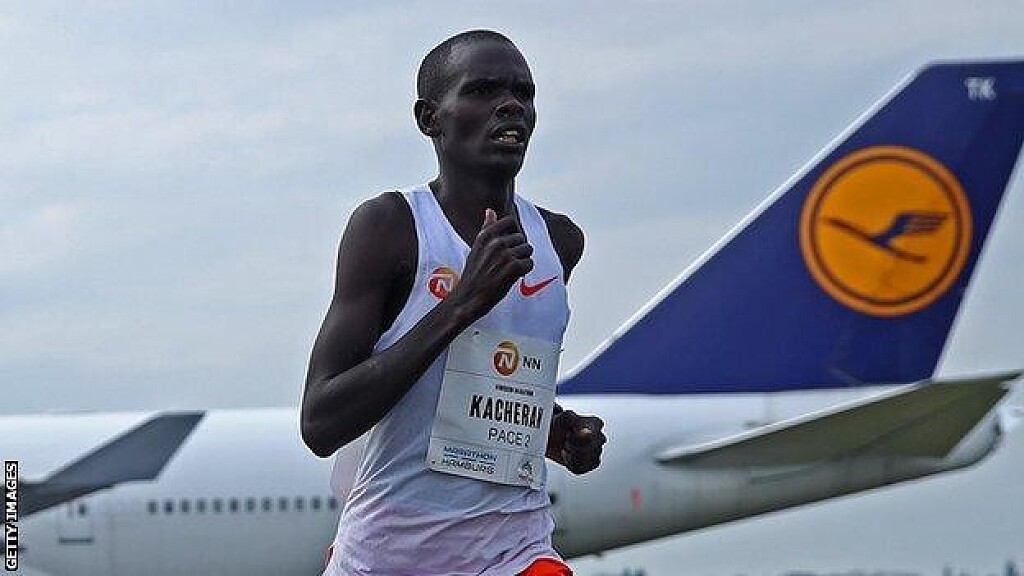

EPO's Prevalence in Doping Cases

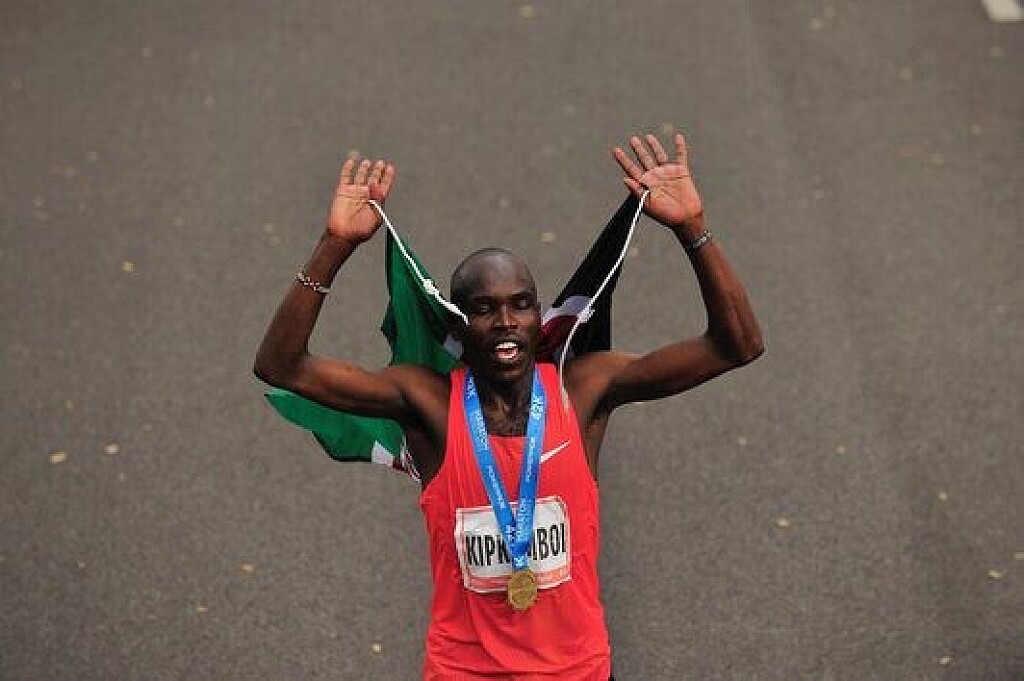

Erythropoietin (EPO) has a history of abuse in endurance sports due to its performance-enhancing capabilities. For example, Kenyan marathon runner Brimin Kipkorir was provisionally suspended in February 2025 after testing positive for EPO and Furosemide. This suspension adds to a series of high-profile doping cases affecting marathon running, especially among Kenyan athletes.

Adapting Governance and Policies to Maintain Trust

High-profile doping scandals have exposed flaws in the governance of athletics. The case of coach Alberto Salazar illustrates the challenges in enforcing anti-doping regulations. Salazar, who led the Nike Oregon Project, was initially banned for four years in 2019 for multiple anti-doping rule violations, including trafficking testosterone and tampering with doping control processes.

In 2021, he received a lifetime ban for sexual and emotional misconduct. His athlete, Galen Rupp, never tested positive for banned substances, yet his reputation suffered due to his association with Salazar. This situation underscores the importance of independent and transparent governance in maintaining the sport's integrity.

The banned drug list

The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) maintains a comprehensive list of substances and methods prohibited in sports to ensure fair competition and athlete health. This list is updated annually and includes categories such as:

· Anabolic Agents: These substances, including anabolic-androgenic steroids, promote muscle growth and enhance performance.

· Peptide Hormones, Growth Factors, and Related Substances: Compounds like erythropoietin (EPO) and human growth hormone (hGH) that can increase red blood cell production or muscle mass.

· Beta-2 Agonists: Typically used for asthma, these can also have performance-enhancing effects when misused.

· Hormone and Metabolic Modulators: Substances that alter hormone functions, such as aromatase inhibitors and selective estrogen receptor modulators.

· Diuretics and Masking Agents: Used to conceal the presence of other prohibited substances or to rapidly lose weight.

· Stimulants: Compounds that increase alertness and reduce fatigue, including certain amphetamines.

· Narcotics: Pain-relieving substances that can impair performance and pose health risks.

· Cannabinoids: Including substances like tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which can affect coordination and concentration.

· Glucocorticoids: Anti-inflammatory agents that, when misused, can have significant side effects.

Additionally, WADA prohibits certain methods, such as blood doping and gene doping, which can artificially enhance performance. It's important to note that while substances like alcohol are legal and widely consumed, they are not banned in most sports despite their potential health risks.

In contrast, substances like EPO, which have not been directly linked to fatalities among runners, are prohibited due to their performance-enhancing effects and potential health risks. This raises questions about the consistency and focus of current substance regulations in sports..

Regarding the percentage of doping violations involving EPO, specific statistics are not readily available. However, EPO has been a focal point in numerous high-profile doping cases, particularly in endurance sports. For detailed and up-to-date information, consulting WADA's official reports and statistics is recommended

Blood Doping Across Sports

Blood doping is prohibited across various sports, particularly those requiring high endurance. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) banned blood doping in 1985, and since then, numerous sports organizations have implemented similar prohibitions. Cycling has been notably affected, with many major champions associated with or suspended for blood doping.

In conclusion, while the fight against doping is essential to maintain fairness in athletics, the current methods employed by WADA may be causing more harm than good. It's imperative to develop more nuanced, fair, and effective anti-doping policies that protect both the integrity of the sport and the rights of its athletes.

by Bob Anderson

Login to leave a comment

2014 Boston Marathon winner to finally receive prize money

10 years after setting the course record, Ethiopia's Buzunesh Deba will be awarded her prize money through the B.A.A.'s new voluntary payments initiative.

On Tuesday, the Boston Athletic Association (B.A.A.), which organizes the Boston Marathon, announced new plans to address prize money discrepancies caused by doping offences over the past 40 years. Starting in January 2025, the B.A.A. will begin issuing voluntary payments to athletes whose results were re-ranked due to disqualifications, dating back to 1986—the year prize money was first introduced.

This announcement is significant for Ethiopian runner Buzunesh Deba and Kenyan athlete Edna Kiplagat, who were both elevated to first place after Kenya’s Rita Jeptoo (2014) and Diana Kipyokei (2021) were disqualified for doping. In Deba’s case, she was originally awarded the second-place prize, but was later recognized as the winner of the 2014 race; she also set the course record of 2:19:59. Despite this, Deba has waited nearly a decade to receive the USD $100,000 owed to her: $75,000 for first place and $25,000 for the course record.

Deba’s payment, set to be issued in January, will be the largest compensation under the B.A.A.’s voluntary payout program. Earlier this year, a Wall Street Journal article put a spotlight on the B.A.A., sharing Deba’s 10-year wait for the prize money. The story caught the attention of Philadelphia businessman Doug Guyer, who sent Deba a USD $75,000 cheque to cover the difference between the first- and second-place prizes.

Jack Fleming, B.A.A. president and CEO said in a press release, “Our initiative aims to ensure that clean athletes are compensated appropriately. While the process to reclaim and redistribute prize money has been challenging, it remains essential to uphold fair competition.”

Eighty runners from eight Boston Marathons and nine participants from the Boston 5K event are eligible to receive payments totalling USD $300,000. Athletes found guilty of doping offences at any time will be ineligible for compensation. The B.A.A. says it will seek to reclaim payments from any recipient later disqualified.

The B.A.A. collaborates with global anti-doping organizations, including the Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU), the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA), to ensure a level playing field at its events. Notably, no male Boston Marathon champion has been stripped of their title for doping.

by Marley Dickinson

Login to leave a comment

Kenya's Charles Kipkkurui Langat issued with two-year ban for doping offence

Kenyan road runner Charles Kipkkurui Langat has received a two-year ban for violating World Athletics anti-doping regulations.

Kenyan road runner Charles Kipkkurui Langat been banned for two years from competing after being found to have violated World Athletics anti-doping rules.

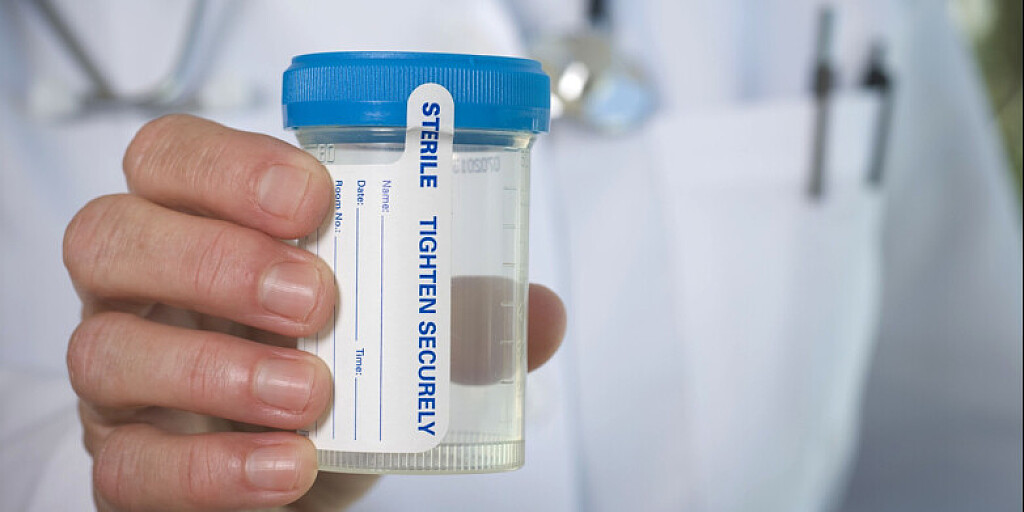

The 28-year-old athlete, who won the eDreams Mitja Marató Barcelona in 2023 with an impressive time of 58:53, provided an out-of-competition urine sample in Iten, Kenya, on August 6, 2024.

The sample tested positive for the prohibited substance Furosemide a diuretic commonly used as a masking agent.

The Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU), the body responsible for managing doping-related issues in athletics, confirmed the violation in a statement released this week.

The AIU’s findings state that Langat did not have a Therapeutic Use Exemption (TUE) for Furosemide, and after reviewing his case, it was determined that no procedural errors occurred during the sample collection and testing process.

“The AIU has no evidence that the Anti-Doping Rule Violations were intentional, and the mandatory period of Ineligibility to be imposed is therefore a period of two (2) years,” the AIU said in its decision.

Langat admitted to the use of Furosemide in an explanation provided to the AIU, stating that he had been suffering from inflammation since September 2023 and had sought medical treatment in the Netherlands earlier this year.

He claimed a doctor advised him to use the substance.

“On 31 July 2024, he contacted a doctor that he knew, who, based on the Athlete’s symptoms, advised him to try using Furosemide for four (4) days to help reduce the inflammation he was experiencing and to ‘help the kidney and the adrenal glands,’” the report detailed.

Despite his explanation, Langat’s admission was enough for the AIU to impose sanctions.

The AIU outlined that his ineligibility would begin from September 11, 2024, when he was provisionally suspended, and his results since August 6, 2024, would be disqualified.

This includes the forfeiture of any titles, awards, and appearance money accumulated during this period.

Langat's case is the latest in a growing number of doping violations involving Kenyan athletes.

Just days ago, another Kenyan runner, Emmaculate Anyango Achol, was provisionally suspended after failing a doping test for testosterone and the blood-boosting hormone EPO.

Anyango, who made headlines by becoming the second woman to complete a 10km race in under 29 minutes, is currently awaiting the outcome of her case.

Kenya,has been grappling with a string of doping scandals in recent years.

The Athletics Integrity Unit has intensified its testing efforts, particularly in high-altitude training regions like Iten, where many elite athletes train.

Langat’s acceptance of the two-year ban and his decision not to contest the charge has drawn attention from both the global athletics community and his home country.

The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and the Anti-Doping Agency of Kenya (ADAK) have the right to appeal the decision to the Court of Arbitration for Sport.

by Festus Chuma

Login to leave a comment

What the New Grand Theory of Brain Science Can Teach Athletes

“Predictive processing” offers novel ways to think about sports psychology, the limits of endurance, and the urge to explore.

If you read popular science books about the brain, you might have encountered a new “grand theory” called predictive processing. If you haven’t yet, you will. Over the last two decades, it has gone from obscure idea to increasingly dominant paradigm. And it’s such a broad and all-encompassing theory that it seemingly has something to say about everything: how the brain works, why it’s structured the way it is, what that means for how we perceive the world—but also horror movies, mental health, cancer cells, and perhaps even endurance sports and adventure.

I’ve been trying to get my head around predictive processing for five or six years now. It can get complicated if you dig into the mathematical details. But I recently read a book called The Experience Machine: How Our Minds Predict and Shape Reality that does a good job of conveying the theory’s essence in an accessible way. It came out last year and is by Andy Clark, a cognitive philosopher at the University of Sussex who is one of the theory’s leading proponents. The book got me thinking about how predictive processing applies to some of the areas of science that I’m most interested in.

Here, then, is a very rough guide to predictive processing—still a speculative and unproven theory at this point, but an intriguing one—from the Sweat Science perspective.

Normally, we assume that you see the world as it is. Light bounces off the objects around you and into your eyes; the receptors in your eyes send signals to your brain; your brain makes sense of those incoming signals and concludes that, say, there’s a snake on the path. Predictive processing flips the script. Your brain starts by making a prediction of what it expects to see; it sends that prediction out toward your eyes, where the predictions are compared with incoming signals. If there’s any discrepancy between the outgoing predictions and the incoming signals, you update your predictions. Maybe it turns out that it’s a stick on the path, even though at first glance you could have sworn it was a snake.

This is actually a very old idea. It’s often attributed, in a basic form, to Hermann von Helmholtz, a nineteenth-century German scientist. Modern neuroscience pushes the idea farther and offers some clues that it’s true: for example, there are more neural connections leading from the brain to sensory organs like the eyes than there are carrying information from the senses back to the brain. Those outgoing signals are presumably carrying the brain’s predictions to the senses. What we see (and hear and smell and so on), in this picture, is basically a controlled hallucination that is periodically fact-checked by the senses.

What I find particularly intriguing about predictive processing is that there’s a deeper mathematical layer. A British scientist named Karl Friston, who pioneered several brain imaging techniques in the 1990s and is by several measures the most-cited neuroscientist ever, has proposed an idea called the free energy principle. All life, Friston argues, has an essential drive to minimize surprise—which is related to a mathematical quantity, borrowed from physics, called free energy—in order to ensure its continued survival. The resulting equations are beautiful but famously inscrutable. If you’re interested, the best introduction I’ve found is in a free e-book published in 2022 by Friston and two colleagues called Active Inference: The Free Energy Principle in Mind, Brain, and Behavior. The important point, though, is that these equations lead to the qualitative picture I described above, of the brain as a prediction machine.

In The Experience Machine, Clark lays out some examples of why this idea matters. Mental health conditions like depression and anxiety may relate to glitches in how the brain updates its predictions; the aesthetic chills you get from great art or horror movies may signal that we’ve encountered “critical new information that resolves important uncertainties”—a physiological “aha” moment. But what does all this tell us about endurance?

The athlete-related topic that Clark addresses most directly in his book is sports psychology. For example, he has a section on the power of self-affirmation, in which the positive words you say to yourself alter your brain’s predictions, which in turns alters your actions in performance-boosting ways. I’ve written a bunch of times about the effects of motivational self-talk on endurance. I’m fascinated by the evidence that it works, but struggle to reconcile it with my mechanistic understanding of how the body works. Predictive processing offers a new way of understanding the science of self-talk.

The key point is that our brains aren’t just predicting the present; they’re also simulating the future, to minimize unexpected surprises. If we expect to feel pain, fatigue, doubt, or even hunger, those predictions become self-fulfilling prophecies—just as, if you’re wandering through the rainforest, you’re more likely to mistake a stick for a snake than if you’re walking down Fifth Avenue. I remember, a decade ago, puzzling over the results of a study that fed people milkshakes and found that their appetite hormones responded differently depending on whether they were told it was an “indulgent” shake or a “sensible” one. How could appetite hormones respond to words? Through the predictions sent from the brain to the gut.

Clark has a long discussion of placebos, but the most unexpected suggestion he makes is a way of improving sports performance “in a rather sneaky manner.” One of the interesting facts about placebos is that the response can be trained. If you give a real, clinically effective drug to someone repeatedly, their brain will eventually begin predicting the response more and more strongly. During the Second World War, nurses who were running short of morphine sometimes injected saline instead; it turns out that, if the patients had been receiving morphine regularly, their bodies (and brains) responded to the saline injection in a similar way.

Clark proposes training an athlete with a drug that is banned in competition (like stimulants), then giving them a placebo version when they actually race. In theory, this should generate a stronger placebo response than you’d normally get. For the record, I don’t think this is consistent with what the World Anti-Doping Agency calls “the spirit of sport,” but it’s an interesting thought experiment.

What first sparked my interest in predictive processing was an email from a reader after my book Endure came out in 2018. I’d written about how our expectations of how a race will feel at any given point affects how hard we feel we’re able to push, based on theories from Ross Tucker and other researchers. Predictive processing, the emailer suggested, might have something to say on the topic.

I think that’s true. As you gain experience, you develop a pretty good idea of what you’ll feel like halfway through a 5K. If you feel better or worse than expected, that generates a prediction error. There are two ways of fixing prediction errors. One is to update your beliefs: I thought this pace would feel medium-hard at this point in the race, but it feels hard, so I’ll adjust my internal prediction. The other is to adjust your actions: I thought this pace would feel medium-hard, so I’ll slow down until it feels medium-hard. The second strategy is what Friston calls active inference.

Why is it that we generally adjust our pace rather than our beliefs when we’re racing? I’m not sure, but I wonder whether predictive processing will suggest some new ways of probing this longstanding question.

There’s a puzzle in predictive processing called the Dark Room problem. If the free energy principle demands that we minimize surprise, why don’t we just lock ourselves in a dark room until we starve to death? One way of answering this question is to recall that we’re not just trying to minimize present surprise; we’re also trying to minimize surprise in the future. And the best way of avoiding future surprises is to learn as much as possible about the world and how it works.

Predictive processing, in other words, wires us to seek out the unknown in order to learn about it, as a way of minimizing future surprise. This is a different way of thinking about why we like venturing into the wilderness, undertaking challenges like running a marathon, and traveling to unfamiliar places. This is an idea I’m digging deeper into for a forthcoming book on the science of exploring.

Does expressing these ideas in the language of predictive processing actually change anything? That remains to be seen. I’ve talked to some scientists over the past few years who view it as genuinely new, and others who view it more as new words for familiar ideas.

The most practical suggestion that I’ve seen comes from an Israeli scientist named Moshe Bar, who wrote a book called Mindwandering in 2022. Bar’s big idea is that we have what he calls “overarching states of mind” that reflect the degree to which we’re focusing on the “top-down” predictions generated by our brains versus the “bottom-up” observations from our senses.

When we put more weight on predictions, we become more narrowly focused on a given task; when we put more weight on sensory data, we have broader attention, are more inclined to explore, and have a more positive mood. By “zooming out”—thinking about the big picture or the future, talking to ourselves in second person—we can shift the dial toward sensory input and loosen the grip that our predictions sometimes exert on us.

Admittedly, all of this sounds a bit esoteric. But the more I read about predictive processing, and the more I talk to scientists who are developing these ideas, the more I’m convinced that there’s something interesting here. Exactly where all this will lead—well, that’s hard to predict.

by Outside Online

Login to leave a comment

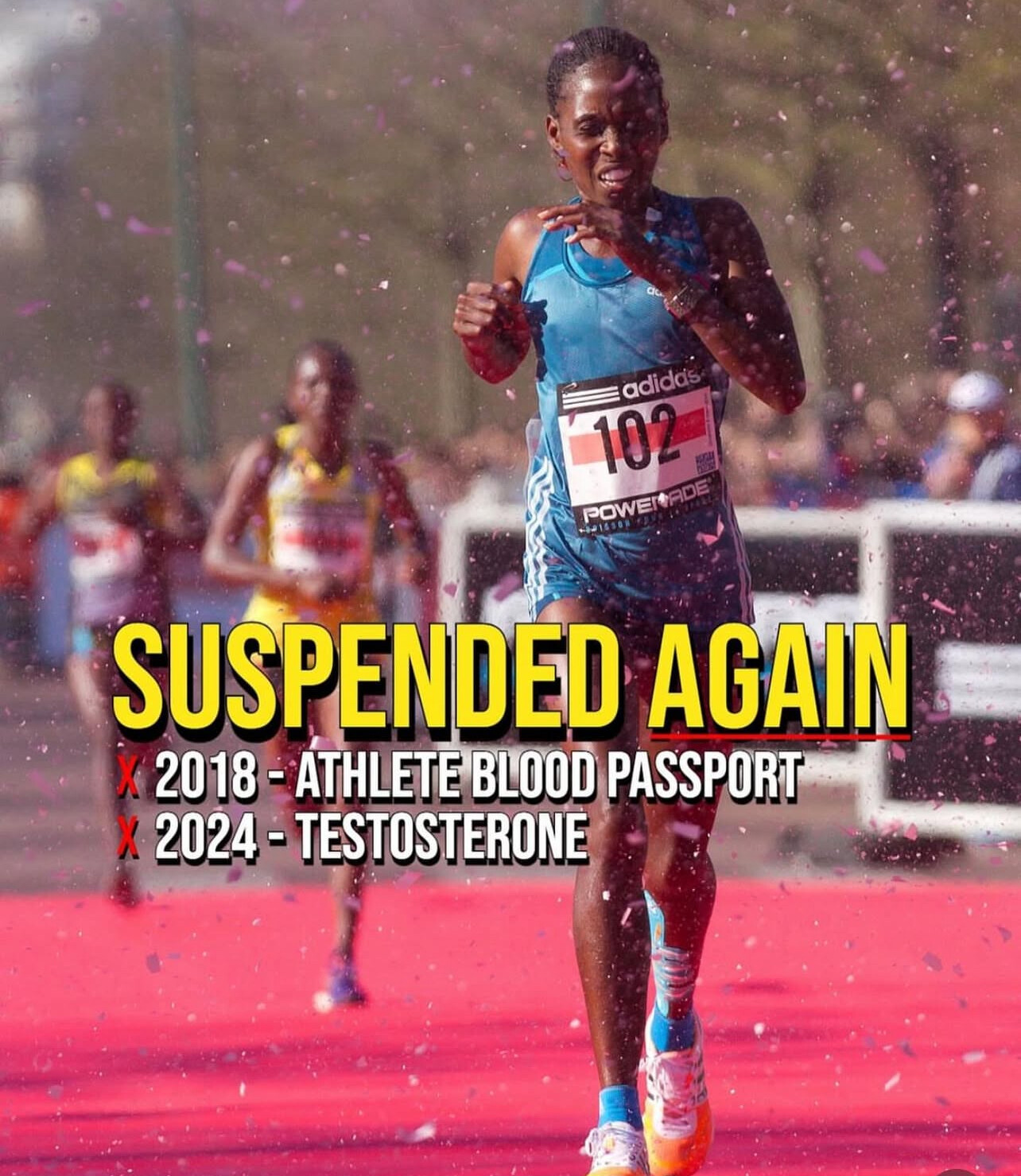

Kenya's Celestine Chepchirchir issued with three-year ban for doping offence

Kenyan runner Celestine Chepchirchir has been banned for three years after testing positive for a prohibited substance, forfeiting all recent titles and awards

Kenyan road runner Celestine Chepchirchir has been banned for three years from competing after being found to have violated World Athletics anti-doping rules.

The 28-year-old athlete provided a urine sample out-of-competition in Kapsabet on February 9, 2024 which tested positive for exogenous testosterone and its metabolites.

According to the official AIU statement, the laboratory in Lausanne, Switzerland, identified the presence of testosterone and its metabolites—Androsterone, Etiocholanolone, 5α-androstane-3α,17 diol, and 5β-androstane-3α,17 diol—as being of exogenous origin.

"Ms. Celestine Chepchirchir did not have a Therapeutic Use Exemption that would justify the presence of these substances," the AIU confirmed.

The ruling added that there was no departure from the International Standard for Testing and Investigations or the International Standard for Laboratories that could explain the adverse finding.

The athlete faced a mandatory four-year period of ineligibility for such a violation under the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) guidelines.

However, Chepchirchir's prompt admission of the violations and her acceptance of the consequences enabled her to benefit from a reduced three-year ban.

"The athlete did not reply within the initial deadline but subsequently signed an Admission of Anti-Doping Rule Violations and Acceptance of Consequences Form," the AIU reported.

Celestine Chepchirchir's ban will commence from March 26, 2024, the date on which her provisional suspension was first imposed.

Moreover, all her results post-February 9, 2024, will be disqualified, with all consequent titles, awards, medals, points, prizes, and appearance money forfeited.

Rights of appeal against the decision are available to WADA and the Anti-Doping Agency of Kenya (ADAK), which could potentially take the matter to the Court of Arbitration for Sport in Lausanne, Switzerland.

The AIU has confirmed that this decision will be publicly reported on their website as part of their commitment to transparency and fairness in the handling of doping cases in athletics.

This case marks another in a series of doping incidents involving Kenyan athletes a troubling pattern that has drawn global attention to the nation's sports programs.

by Festus Chuma

Login to leave a comment

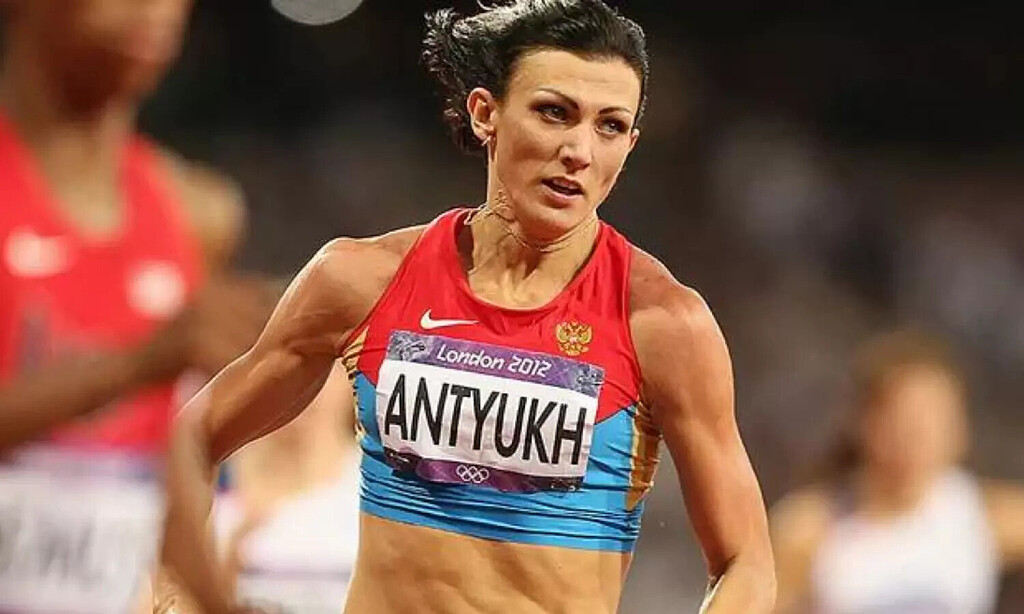

Pamela Jelimo set to receive Olympic silver after Ekaterina Guliyev's doping ban

South Africa's Caster Semenya has been elevated to gold with Kenya's Pamela Jelimo set for silver after doping reshuffle in 2012 Olympics 800m.

Former Olympic 800 champion, Pamela Jelimo, is poised to be awarded the 2012 London Olympic 800m silver, marking a significant shift in the event's final standings due to doping violations.

This development comes after the Russian Athletics Federation (RusAF) announced a four-year ban for Ekaterina Poistogova-Guliyev for historic doping offences, leading to a reshuffle of the medal positions from the London games.

The ban, which results from violations between July 2012 and October 2014, voids all of Poistogova-Guliyev's results from that period, according to a RusAF statement.

The athlete, who initially competed for Russia before switching allegiance to Turkey, was implicated in the use or attempted use of banned substances, with evidence drawn from the Moscow anti-doping laboratory.

The case has had far-reaching implications, not only for Poistogova-Guliyev but also for other athletes in the 2012 Olympic 800m event.

Pamela Jelimo, the London Olympic bronze medallist, will be elevated to silver, and American Alysia Montano, who finished fifth, is set to inherit the bronze, pending official confirmation.

This adjustment stems from a broader investigation into systematic doping within Russian athletics, spearheaded by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA).

WADA had initially recommended a lifetime ban for Poistogova-Guliyev in 2015, alongside the stripping of her London medal, as part of its findings on state-sponsored doping.

Although the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) imposed a two-year ban on Poistogova-Guliyev in 2017, her results were initially voided only back to October 2015, allowing her to retain her Olympic medal temporarily.

The recent decision by RusAF to extend the voiding of her results to July 2012 effectively strips her of the medal, subject to final approval by the International Olympic Committee (IOC).

The women's middle distance events at the London Olympics have been notably affected by doping, with three runners in the 800m final, including Poistogova-Guliyev, Mariya Savinova, and Elena Arzhakova, having their results voided due to doping offences.

Jelimo's elevation to the silver medal position comes after a long wait; it took 10 years for her to be awarded the bronze medal for the same event, following the disqualification of Maria Savinova for doping violations.

The reallocation of medals in cases of doping violations is a complex and often slow process, involving multiple organisations including WADA, CAS, RusAF, and the IOC.

The final decision on the redistribution of medals from the 2012 Olympics will be closely watched by the athletics community and represents a critical step in the ongoing fight against doping in sport.

Poistogova-Guliyev's ban, which lasts until 2026, reflects a deduction for the time served under her previous CAS-imposed sanction.

In addition to her case, RusAF has announced a two-year and six-month ban for 3,000m steeplechaser Nikolay Chavkin for similar doping offenses.

by Festus Chuma

Login to leave a comment

Kenya's Winnie Jemutai issued with three-year ban for doping offence

Winnie Jemutai is the latest Kenyan athlete to join the list of shame after being provisionally suspended by the AIU for the Presence/Use of Prohibited Substance (Testosterone).

The Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU) has banned Kenyan middle-distance runner Winnie Jemutai Boinett for three years due to the presence and use of a prohibited substance, testosterone.

This decision follows the disqualification of Boinett's results since November 12, 2023 when she was provisionally suspended.

Boinett's suspension comes after a urine sample she provided in-competition at the XLI Cross Internacional de Italica in Seville, Spain, on November 12, 2023, tested positive for testosterone, a substance banned under the World Anti-Doping Agency's (WADA) prohibited list.

Following the initial findings, Boinett admitted to the anti-doping rule violations and accepted the consequences, including the forfeiture of any medals, titles, points, prize money, and other prizes won since the date of the provisional suspension.

In a letter to the AIU dated March 5, 2024, Boinett stated, "I had injury. I went to different hospitals for treatment, I don't have exact documents showing exact medications that I went through I honestly accept that I break the anti-doping rules and am ready to face the consequences thank you."

This early admission and acceptance of sanction led to a one-year reduction in the originally asserted period of ineligibility, pursuant to Rule 10.8.1, based on Boinett's cooperation and acknowledgment of the violations.

Furthermore, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and the Anti-Doping Agency of Kenya (ADAK) have been granted the right to appeal against this decision to the Court of Arbitration for Sport in Lausanne, Switzerland, should they find grounds to do so.

This provision ensures that all parties involved have a fair opportunity to present their case and seek justice through the appropriate legal channels.

by Festus Chuma

Login to leave a comment

Sarah Chepchirchir slapped with an eight-year ban by AIU

39-year-old runner Sarah Chepchirchir has been slapped with an eight-year ban for violating the anti-doping rules for the second time following her first ban which happened from 2019 to 2023.

The Athletics Integrity Unit has slapped Sarah Chepchirchir of Kenya with an eight-year ban for violating an anti-doping rule.

Chepchirchir was banned for the Presence/Use of a Prohibited Substance (Testosterone) and her results from November 5, 2023have been disqualified.

The AIU reported that the 39-year-old runner provided a urine sample on November 5, 2023, after competing at the Bangsaen42 Chonburi Marathon in Chonburi, Thailand.

An analysis of the sample by the World Anti-Doping Agency (“WADA”) accredited laboratory in Bangkok, Thailand (the “Laboratory”), revealed the presence of Metabolites of Testosterone consistent with exogenous origin (the “Adverse Analytical Finding”).

As per the AIU, testosterone is a Prohibited Substance under the WADA 2023 Prohibited List under the category S1.1 Anabolic Androgenic Steroids. It is a Non-Specified Substance prohibited at all times.

Meanwhile, the AIU further noted that the Chepchirchir previously served a period of Ineligibility of four (4) years from February 6, 2019 to February 5, 2023 for an Anti-Doping Rule Violation under Article 2.2 of the 2018 IAAF Rules (equivalent to Rule 2.2 of the Rules) (Use of a Prohibited Substance or a Prohibited Method) based on abnormal values in the hematological module of her Athlete Biological Passport.

“A period of Ineligibility of eight (8) years commencing on December 22, 2023, until December 21, 2031, and disqualification of the Athlete’s results on and since November 5, 2023, with all resulting consequences, including the forfeiture of any titles, awards, medals, points prize, and appearance money.

“The Athlete is deemed to have accepted the above Consequences and to have waived her right to have those Consequences determined by the Disciplinary Tribunal at a hearing,” the AIU said regarding her punishment.

by Abigael Wuafula

Login to leave a comment

Ugandan middle-distance runner Prisca Chesang given two-year ban for masking agent

On Friday, the Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU) issued a two-year ban for two-time U20 world championship medalist Prisca Chesang of Uganda. Chesang tested positive for the banned diuretic and masking agent furosemide.

Chesang’s positive test came out-of-competition, at a training camp in Kapchorwa, Uganda, on Sept. 14. She was in Kapchorwa preparing for the women’s mile at the 2023 World Road Running Championships in Riga, Latvia, where she placed 18th overall, on Oct. 1.

The 20-year-old is a two-time world U20 medalist in the women’s 5,000m, winning bronze at both the 2021 and 2022 U20 championships. According to the AIU, they did not discover any evidence that Chesang’s actions were intentional and therefore she was only given a two-year ban instead of four years. Chesang admitted to the Anti-Doping Rule Violation (ADRV); her result from the 2023 World Road Running Championships will be disqualified, and she will serve a two-year ban, until Dec. 6, 2025.

Furosemide is a diuretic, meaning it increases urine production, eliminating excess water and salt from the body. (It is also used for losing weight.) Furosemide also serves as a masking agent for other performance-enhancing substances that leave the body through urination, and therefore show up in a urine test. The drug has been prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) for decades.

Chesang is one of Uganda’s top up-and-coming distance runners and represented the East African nation at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics in the women’s 5,000m (but failed to advance from the heats). Her top senior championship finish was a seventh-place result at the 2023 World XC Championships in Bathurst, Australia, helping Uganda’s women’s team win bronze.

Chesang is only the second female Ugandan runner to be suspended by the AIU. The country’s first came in Nov. 2023, when Janat Chemusto was given a four-year ban for the use of a prohibited substance.

by Marley Dickinson

Login to leave a comment

Ugandan runner Prisca Chesang provisionally suspended by the Athletics Integrity Unit

Ugandan runner faces provisional suspension by AIU for for the presence/use of a prohibited substance (Furosemide).

World U20 5000m bronze medalist Prisca Chesang has found herself in hot water with the Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU).

The 20-year-old Ugandan has been provisionally suspended by AIU for the Presence/Use of a Prohibited Substance (Furosemide), a clear violation of the World Anti-Doping rules.

Chesang, who made headlines as the fourth female Ugandan athlete to secure a medal at the junior championship, finds herself facing charges under Article 2.1 and Article 2.2 of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA).

Chesang's remarkable journey began at the 2021 World Athletics U20 Championships in Nairobi, Kenya, and continued in Cali, Colombia last year, where she clinched the bronze medal.

She joined the ranks of Peruth Chemutai (2018), Annet Negesa (2010), and Dorcus Inzikuru (2000) as one of the few female Ugandan runners to achieve such a feat at the junior level.

"The AIU has provisionally suspended Prisca Chesang (Uganda) for the Presence/Use of a Prohibited Substance (Furosemide)," the AIU confirmed.

Chesang's suspension echoes a somber note in Ugandan running history, following the suspension and three-year ban of Janat Chemusto in November.

Prisca Chesang had been making remarkable strides in the senior division as well, finishing 7th overall at the World Cross Country Championships held in Bathurst, Australia, earlier this year.

However, it was her astonishing performance in the 10km race and her ranking at the World Cross Country Championships in 2023 that truly had the athletics world taking notice.

On New Year's Eve in 2022, Chesang emerged as the champion of the Madrid 10km with an incredible time of 30:19.

This achievement unofficially crowned her as the fastest junior athlete ever over the 10km distance.

Her exceptional performance ranked her 6th on the Senior World List for 2022 and placed her among the top 20 on the World All-Time list for the same distance.

by Festus Chuma

Login to leave a comment

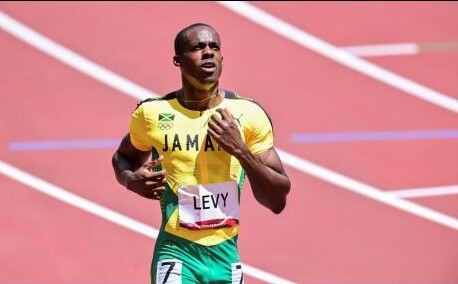

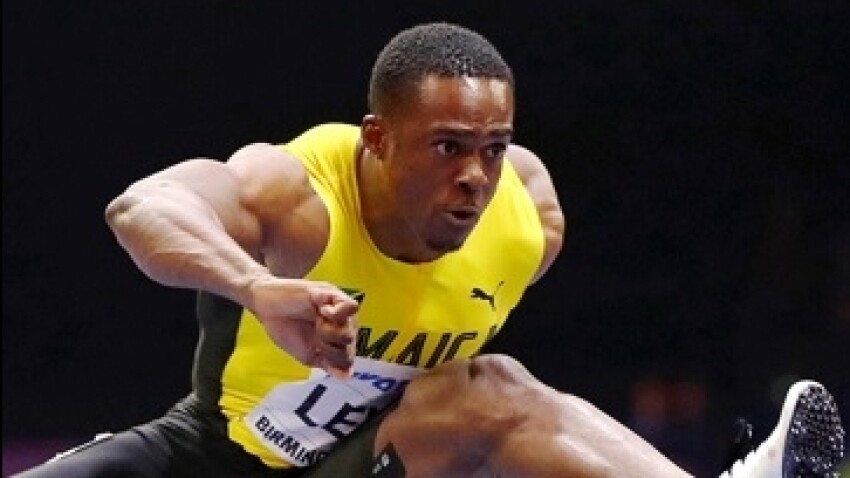

Jamaican Olympic bronze medalist in the 110m hurdles, Ronald Levy faces potential 4-year ban

Jamaican Olympic bronze medalist in the 110m hurdles, Ronald Levy, faces a significant setback in his athletic career as the B-sample from his recent drug test has returned positive for two banned substances.

The initial discovery of these substances was made in his A-sample during an out-of-competition test conducted last month by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) lab in Canada.

As a result of the positive B-sample, Levy now faces a hearing and the possibility of a four-year ban from competitive athletics. Such a ban could have far-reaching implications, potentially ruling him out of participating in the upcoming Paris Olympics in the summer of next year, as well as the World Athletic Championships scheduled for 2025 and 2027.

Banned Substances Identified

According to Radio Jamaica Sports sources, the two banned substances detected in Levy’s sample are GW501516-Sulfoxide and GW501516-Sulfone. The presence of these prohibited substances raises serious concerns about Levy’s adherence to anti-doping regulations.

Earlier this month, the athlete confirmed the adverse finding through his Instagram page, disclosing that he had been notified of the test results on November 3. However, he did not initially reveal the names of the specific drugs that led to the adverse finding.

The development casts a shadow over Levy’s athletic career and places his future participation in major international competitions in doubt. It also underscores the importance of strict adherence to anti-doping protocols and the consequences of violating anti-doping regulations in the world of sports.

by Ben McLeod

Login to leave a comment

AIU slap 23-year-old Esther Borura with three-year ban for doping

Esther Borura was banned due to the Presence of a Prohibited Substance (19-norandrosterone) and the Use of a Prohibited Substance (Nandrolone or Nandrolone. precursors).

The Athletics Integrity Unit has slapped Esther Birundu Borura with a three-year ban for an anti-doping rule violation.

Borura’s ban backdates to September 6, 2023, and will run to 2026. She was banned due to the Presence of a Prohibited Substance (19-norandrosterone) and the Use of a Prohibited Substance (Nandrolone or Nandrolone precursors).

The AIU also noted that the 23-year-old’s results since June 30, 2023, have been disqualified. On June 30, 2023, Borura provided a urine sample, Out-of-Competition in Iten, Kenya, which was given code 7184933.

On August 22, the World Anti-Doping Agency (“WADA”) accredited laboratory in Doha, Qatar reported an Adverse Analytical Finding in the Sample.

“The AIU reviewed the Adverse Analytical and determined that Borura did not have a Therapeutic Use Exemption (“TUE”) that had been granted (or that would be granted) for the 19-Norandrosterone consistent with exogenous origin found in the Sample.

There was no apparent departure from the International Standard for Testing and Investigations (“ISTI”) or from the International Standard for Laboratories (“ISL”) that could reasonably have caused the Adverse Analytical Finding,” the AIU statement read in part.

On September 7, Borura requested for an interview with the AIU through her Athletes’ Representative.

As reported by the AIU, on September 13, they (AIU) asked the Athlete to provide a written summary of her explanation and the information that she wished to provide in the interview.

“On 15 September 2023, the Athletes’ Representative provided the AIU with the Athlete’s summary explanation, which set out that the Athlete waived her rights to have the B Sample analysed and to request the LDP, admitted to having committed Anti-Doping Rule Violations, had purchased prohibited substances in April 2023, and been injected in May 2023.

Averred that this was the only time that she had used prohibited substances. On 26 September 2023, the Athlete attended an interview with AIU representatives and provided additional information in relation to her explanation (as summarised above),” the statement further noted.

by Abigael Wuafula

Login to leave a comment

World championship silver medalist suspended 30 months for evading doping test

Jamaican 400m runner and 2022 world championship silver medalist Christopher Taylor has been slapped with a 30-month suspension by the Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU) after evading an out-of-competition doping test without justification in November 2022.

After a comprehensive six-month investigation, the AIU found that Taylor violated Article 2.3 of the World Anti-Doping Agency’s (WADA) Anti-Doping Code, deeming his actions as “evading, refusing, or failing to submit to sample collection.” In November 2022, anti-doping officials attempted to conduct an out-of-competition doping test at the location Taylor had specified on his whereabouts form, but he was not present at the location and had not updated his whereabouts information.

According to the Jamaica Observer, Taylor was at the Norman Manley International Airport in Kingston when the officials arrived at his home, waiting to catch a flight to the U.S.

If an athlete is not where they say they are when anti-doping officials show up, it counts as a missed test. Typically, a first or second offense does not carry any penalty, but if an athlete misses three tests during a 12-month period, that constitutes a whereabouts violation, resulting in an automatic period of ineligibility.

Taylor was a finalist in the men’s 400m at the Tokyo Olympics and the 2022 World Championships in Eugene, Ore. He also helped the Jamaican men’s 4x400m relay team win silver at 2022 Worlds.

Twelve of the 30 months of his suspension have already elapsed; Taylor will become eligible to compete again in May 2025. His last competitive race was in August 2022.

by Marley Dickinson

Login to leave a comment

Molly Seidel Stunned the World (and Herself) with Olympic Bronze in Tokyo. Then Life Went Sideways.

She stunned the world (and herself) with Olympic bronze in Tokyo. Then life went sideways. How America’s unexpected marathon phenom is getting her body—and brain—back on track.

On a clear December night in 2019, Molly Seidel was at a rooftop holiday party in Boston, wearing a black velvet dress, doing what a lot of 25-year-olds do: passing a joint between friends, wondering what she was doing with her life.

“You should run the Olympic Trials,” her sister, Izzy, said, as smoke swirled in the chilly air atop The Trackhouse, a retail shop and community hub on Newbury Street operated by the running brand Tracksmith. “That would be hilarious if you did that as your first marathon.”

Molly, an elite 10K racer who’d spent much of 2019 injured, looked out at the city lights, and laughed. Why the hell not? She’d just qualified for the trials, winning the San Antonio Half with a time of 1:10:27. (“The shock of the century,” as she’d put it.) True, 13.1 miles wasn’t 26.2—but running a marathon was something to do. If only because she never had before.

A four-time NCAA track and cross-country champion at The University of Notre Dame in Indiana, Molly had moved to Boston in 2017, where she’d worked three jobs to supplement her fourth: running for Saucony’s Freedom Track Club. The $34,000 a year that Saucony paid her (pre-tax, sans medical) didn’t go far in one of America’s most expensive cities. Chasing kids around as a babysitter, driving around as an Instacart shopper, and standing around eight hours a day as a barista—when you’re running 20 miles a day—wasn’t ideal. But whatever, she had compression socks. And she was downing free coffee and paying rent, flying to Flagstaff, Arizona, every so often for altitude camps, and having a good time. Doing what she loved. The only thing she’s ever wanted to do since she was a freckly fifth-grader in small-town Wisconsin clocking a six-minute mile in gym class.

“I was hustling, and I loved it. It was such a fun, cool time of my life,” she says, summarizing her 20s. Staring into Molly’s steely brown eyes, listening to her speak with such clarity and conviction about her struggles since, it’s easy to forget: She is still only 29.

After Molly had hip surgery on her birthday in July 2018, her doctors gave her a 50/50 chance of running professionally again. By summer 2019, she’d parted ways with FTC, which left her sobbing on the banks of the Charles River, getting eaten alive by mosquitoes and uncertainty. Her biggest achievement lately had been being named #2 Top Instacart Shopper (in Flagstaff; Boston was big-time).

The day after that rooftop party, Molly asked her friend and former FTC teammate Jon Green, who she’d newly anointed as her coach: “Think I should run the marathon trials?” Sure, he shrugged. Nothing to lose. Maybe it’d help her train for the 10K, her best shot—they both thought—at making a U.S. Olympic team.

“I’m going to get my ass kicked six ways to Sunday!” she told the host of the podcast Running On Om six weeks before the trials in Atlanta.

Instead, on February 29, 2020, she kicked some herself. Pushing past 448 of the fastest, most-experienced women marathoners in the country, coming in second with a 2:27:31, earning more in prize money ($60,000) than she had in two years of racing—and a spot on the U.S. trio for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, along with Kenyan-born superstars Aliphine Tuliamuk and Sally Kipyego. “I don’t know what’s happening right now!” Molly kept saying into TV cameras, wrapped in an American flag, as stunned as a lottery winner.

Saucony who? Puma came calling. Along with something Molly hadn’t anticipated: the spotlight. An onslaught of social media followers. And two weeks later, a global pandemic and lockdown—and all the anxiety and isolation that came with it. She was drowning, and she hadn’t even landed in Tokyo yet.

The 2020 Olympics, as we all know, were postponed to 2021. An emotional burden but a physical boon for Molly, in that it allowed her to get in a second marathon. In London, she finished two minutes faster than her debut. When the Olympics finally rolled around, she was ready.

Before the race, Molly says, “I was thinking: ‘Once I cross the starting line, I get to call myself an Olympian and that’s a win for the day.’”

But then she crossed the finish line—with a finger-kiss to the sky and a guttural Yesss!—in third place with a 2:27:46, just 26 seconds behind first (Kenya’s Peres Jepchirchir). And realized: She gets to call herself an Olympic medalist forever. Only the third American woman to ever earn one in the marathon.

Lots of kids have fleeting hopes of making it to the Olympics. I remember thinking I could be Mary Lou Retton. Maybe FloJo, with shorter fingernails. Then I decided I’d rather be Madonna or president of the United States and promptly forgot about it. But Molly held tight to her Olympic aspirations. She still has a poster she made in 2004, with stickers and a snapshot of her smiley 10-year-old self, to prove it. “I wish I will make it into the Olympics and win a gold medal,” she wrote, and signed it: Molly Seidel, the “y” looping back to underline her name. In case there was any doubt as to who, specifically, would be winning the medal.

Molly grew up in Nashotah, Wisconsin, and is the eldest of three. Her sister and brother, younger by not quite two years, are twins. Izzy is a running influencer and corporate content creator for companies like Peloton; and Fritz favors Formula 1 racing and weightlifting and works for the family’s leather-tanning business. The family was active, sporty. Dad, Fritz Sr., was a ski racer in college; Mom, Anne, a cheerleader. You can tell. Watching clips of Molly’s mom and dad watching the Olympic race from their backyard patio, jumping up and down, tears streaming, is the kind of life-affirming moment you wish you could bottle. “I’m in shock. I’m in disbelief,” Molly says into the mic, beaming. “I just wanted to come out today and I don’t know…stick my nose where it didn’t belong and see what I could come away with. And I guess that’s a medal.” When the interviewer holds up her family on FaceTime, Molly breaks down. “We did it,” she says into the screen between sobs and smiles. “Please drink a beer for me.

Molly hasn’t always been unabashedly herself, even when everyone thought she was. A compartmentalizer to the core, she spent most of her life hiding a huge part of it: anorexia, bulimia, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, debilitating depression.

It started around age 11, when she learned to disguise OCD tendencies, like compulsively knocking on wood, silently reciting prayers “to avoid God getting mad at me,” she says. “It was a whole thing.” She says her parents were aware of the behaviors, but saw them more as odd little habits. “They had no reason to suspect anything. I was very high-functioning,” she says. “They didn’t realize that it was literally taking over my life.”

She wasn’t officially diagnosed with OCD until her freshman year of college, when she saw a therapist for the first time. At Notre Dame, disordered eating took hold, quietly yet visibly, as it does for up to 62 percent of female college athletes, according to the National Eating Disorders Association. As recently as the Tokyo Olympics, she was making herself throw up in the airport bathroom, mere days before taking the podium. Molly hesitates to share that detail; she fears a girl might read this and interpret it as behavior to model. “Having been in that place as a younger athlete, I know I would have,” she says. But she also understands: Most people just don’t get how unrelenting eating disorders can be.

In February 2022, she finally received a diagnosis of the root cause for all of it: ADHD. About being diagnosed, she says, “It made me feel really good, like [I don’t have] a million different disorders. I have a disorder that manifests itself in a lot of different symptoms.”

She waited to try Adderall until after the Boston Marathon in April, only to drop out at mile 16 due to a hip impingement. Initially, the meds made her feel fantastic. Focused. Free. Until she realized Adderall hurt more than it helped. She couldn’t sleep, couldn’t eat, lost too much weight. Within weeks, she devolved. “The eating disorder came roaring back,” she says, referring to it, as she often does, as its own entity, something that exists outside of herself. That ruthlessly takes control over her very need for control. “I almost think of it as an alter ego,” she explains. “Adderall was just bubblegum in the dam,” as she puts it. She ditched the drug, and her life—professionally, physically—unraveled.

In July 2022, heading into the World Championships, she bombed the mental health screening, answering the questions with brutal honesty. She’d been texting Keira D’Amato weeks prior. “Yo girl, things are pretty bad right now. Get ready…” Sobbing on the sidewalk in Eugene, Oregon, she texted D’Amato again. And the USATF made it official: D’Amato would take her spot on the team. Then Molly did what she’d been “putting off and putting off”— checked herself into eating disorder treatment for the second time since 2016, an outpatient program in Salt Lake City, where her new boyfriend was living at the time.

Somehow (see: expert compartmentalizer) mid-meltdown, in February 2022, she had met an amateur ultrarunner named Matt, on Hinge. A quiet, lanky photographer, he didn’t totally get what she did. “I didn’t understand the gravity of it,” he tells me. “I was like, Oh she’s a pro runner, that’s cool. I didn’t realize she was, like, the pro runner!”

Going back to treatment “was pretty terrible,” she says. At least she could stay with Matt. Hardly a honeymoon phase, but the new relationship held promise. “I laid it all out there,” says Molly. “And he was still here for it, for all the messiness. It was really meaningful.” And a mental shift. “He doesn’t see me as just Molly the Runner.”

Almost a year later, on a freezing April evening in Flagstaff, Molly is racing around Whole Foods, palming a head of cabbage, grabbing a thing of hummus, hunting for deals even though she doesn’t need to anymore.

“It’s all about speed, efficiency, and quality,” she says, explaining the secret to her earlier Instacart success. She checks the expiration date on a container of goat cheese and beelines for the butcher counter, scans it faster than an Epson DS3000, though not without calculation, and requests two tomato-and-mozzarella-stuffed chicken breasts. Then she darts over to the beverage aisle in her marshmallow-y Puma slip-ons that Matt custom-painted with orange poppies. She grabs a case of La Croix (tangerine), then zips to the checkout. We’re in and out in under 15 minutes and 50 bucks, nothing bruised or broken.

Other than her body. Let’s just say: If Molly were an avocado or a carton of eggs, she probably wouldn’t pass her own sniff test. The week we meet, she is just coming off a month of no running. Not a single mile. She’s used to running twice a day, 130 miles a week. No wonder she’s spraying her kitchen counter with Mrs. Meyer’s and scrubbing the stovetop within minutes of welcoming me into her new home.

The place, which she shares with Matt and his Australian border collie, Rye, has a post-college flophouse feel: a deep L-shaped couch draped in Pendleton blankets, a bar cluttered with bottles of discount wine, a floor lamp leaning like the Tower of Pisa next to a chew toy in the shape of a ranch dressing bottle. Scattered about, though, are reminders that an elite runner sleeps here. Or at least tries to. (“Pro runner by day, mild insomniac by night” reads the bio on her rarely used account on what used to be Twitter.) There’s a stick of Chafe Safe on the coffee table. Shalane Flanagan’s cookbooks on the counter. And framed in glass, propped on the office floor: Molly’s Olympic kit—blue racing briefs with the Nike Swoosh, a USA singlet, her once-sweat-drenched American flag, folded in a triangle. “I’m not sure where to hang it,” she says. “It seems a little ostentatious to have it in the living room.”

With long brown curls and a round, freckly face, Molly has an aw-shucks look so innocent that it’s hard, at first, to perceive her struggles. Flat-out ask her, though—How are you even functioning?—and she’ll tell you: “I’m an absolute wreck. There’s no worse feeling than being a pro runner who can’t run. You just feel fucking useless.” Tidying a stack of newspapers, she adds, “Don’t worry, I’ve had therapy today.”

She’s watched every show. (Save Ted Lasso, “too sickly sweet.”) Listened to every podcast. (Armchair Expert is a favorite.) She’s got nothing else to do but PT and go easy on the ElliptiGo in the garage, onto which she’s rigged a wooden bookstand, currently clipped with A History of God: The 4,000 Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. “I don’t read running books,” she says. “I need something different.”

Like most runners—even the most amateur among us—running, moving, is what keeps her sane. “What about swimming? Can you at least swim?” I ask, projecting my own desperation if I were in her size 8.5 shoes. “I fucking hate swimming,” says Molly. Walking? “Oh, yeah, I can go on walks. Another. Long. Walk.”

The only thing she has on her schedule this week is pumping up a local middle school track team before their big meet. The invitation boosted her spirits. “Should I just memorize Miracle on Ice?” she says, laughing. “No, I know, I’ll do Independence Day.”

Injuries are nothing new for Molly. Par for the course for any professional athlete. But especially for women, like her, who lack bone density—and have since high school, when, according to a study in the Orthopedic Journal of Sports Medicine, nearly half of female runners experience period loss. Osteoporosis and its precursor, osteopenia, are rampant in female runners, leading to ongoing issues that threaten not just their college and professional running careers, but their lives.

Still, Molly admits, laughing: She’s especially accident-prone. I ask her to list every scratch she’s ever had, which takes her 10 minutes, and goes all the way back to babyhood, when she banged her head against the bathtub spout. There was a cracked spine from a sledding incident in 8th grade, a broken collarbone from a ski race in high school, shredded knee cartilage in college when a driver hit her while she was riding a bike. “Ribs are constantly breaking,” she says. In 2021, two snapped, and refused to heal in time for the New York City Marathon. No biggie. She ran through the pain with a 2:24:42, besting Deena Kastor’s 2008 time by more than a minute and setting the American course record.

Molly’s latest injury? Glute tear. “Literally a gigantic pain in the ass,” she posted on Instagram in March. Inside, Molly was devastated. Pulling out of the Nagoya Marathon—the night before her 6:45 a.m. flight to Japan, no less—was not in the plan. The plan, according to Coach Green, had been simple. It always is. If the two of them even have one. “Just to have fun and be consistent.” And get a marathon or two in before the Olympic Trials in February 2024.

She’d been finally—finally—fit on all fronts; ready to race, ready to return. She needed Nagoya. And then, nothing. “It feels like I’m back at the bottom of the well,” says Molly, driving home from Whole Foods in her Toyota 4Runner. “This last year-and-a-half has been so difficult. It’s just been a lot of doubt. How do I approach this, as someone who has now won a medal? Like, man, am I even relevant in this sport anymore?” She pops a piece of gum in her mouth. I wait for her to offer me some, because that’s what you do with gum, but she doesn’t. She’s so in her head. “It’s hard when you’re in the thick of it, you know, to figure out: Why the fuck do I keep doing this? When it just breaks my heart over and over and over again?”

We pull into her driveway. “I was prepared for the low period after Tokyo,” she says. “But this has been much longer and lower than I expected.”

The curse of making it to the Olympics, let alone coming back with a medal: expectations. Molly’s own were high. “I think I thought, after the Olympics, if I win a medal, then I will be fixed, it will fix everything.” Instead, in a way, it made everything worse.

That’s the problem that has plagued Molly for most of her running career: Her triumphs and troubles intermingle, like thunder and lightning. Which, by the way, she has been struck by. (A minor backyard-grill, summer-thunderstorm incident. She was fine.)

The next morning in Flagstaff, Molly’s feeling like she can run a mile, maybe two. It’s snowing, though, and she doesn’t want to risk the slippery track, so we meet at Campbell Mesa Trails. She loops a band around the back of her truck to stretch and sends me off into the trees to run alone while she does a couple of laps on the street.

Molly leaves for an acupuncture appointment, and we reunite later at Single Speed Coffee (“the best coffee in Flagstaff,” promises the ex-barista who drinks up to three cups a day). We curl up on a couch like it’s her living room, and she talks as freely—and as loudly—as if it was. Does she realize everyone can hear her? She doesn’t care. I guess that’s what happens when you’ve grown so comfortable sharing—in therapy, on podcasts, in a three-part video series on ADHD for WebMD—you just…share. Loud and proud.

Mental illness is so insidious, says Molly. “It’s not always this Sylvia Plath stick-my-head-in-a-fucking-oven thing, where you’re sad all the time,” she says. “High-functioning depressed people live normal successful lives. I can be having the happiest moment, and three days later I’m in a total downward spiral.” It’s something you never recover from, she says, but you learn to manage.

“I’m this incredibly flawed person who struggles so much. I think: How could I have won this thing when I’m so flawed? I look at all the people around me, all these accomplished people who have their shit together, and I’m like, ‘one of these things is not like the other,’” she says, taking a sip of her flat white. “I was literally in the Olympic Village thinking: Everybody is probably looking at me wondering: Why the hell is she here?”

They weren’t. They don’t. She knows that.

And yet her mind races as fast as she does. It takes up So. Much. Space. When she’s running, though, the noise disappears. She’s not Olympic Molly or Eating Disorder Molly, she’s not even, really, Runner Molly. “When I’m running,” she says, “I’m the most authentic version of myself.”

Talking helps, too. Molly first shared her mental health history a few years ago, “before she was famous,” as she puts it. After the Olympics, though, she kept talking and hasn’t stopped. The Tokyo Games were a turning point, she says. Suddenly the most revered athletes in the world were opening up about their mental health. Molly credits Simone Biles’s bravery for her own. If Biles, and Michael Phelps and Naomi Osaka, could come clean... then maybe a nerdy, niche-y, unlikely medaling marathoner could, too.

“Those guys got a lot more shit for it than I did,” says Molly. “I got off easy. I’m not a household name,” she laughs. She knows she can be candid and off the cuff—and chat freely in a not-empty café—in a way Biles never could. “I’m a nobody!” she laughs.

Still, a nobody with 232,000 Instagram followers whom she has touched in very IRL ways—becoming an unintentional poster woman for normalizing mental health challenges among athletes. “You are such an incredible inspiration,” @1percentpeterson posts, one comment of a zillion similar. “It’s ok to not be ok!” says another. Along with all the online love is, of course, online hate. Molly rattles off a few lowlights: “She’s an attention-seeking whore,” “Her bones are so brittle she’ll never race again,” “She’s running so badly and posting a lot she should really focus on her running more.” Molly finds it curious. “I’m like, ‘If you hate me, you don’t need to follow me, sir.’”

It’s Molly’s nobody-ness—what Outside writer Martin Fritz Huber called her “runner-next-door” persona, and I’ll just call “genuine personality”—that has made her somebody in running’s otherwise reserved circles.

Somebody who (gasp!) high-fives her sister in the middle of a major race, as she did at mile 18 of the 2021 New York City Marathon. “They shat on me in the broadcast for it,” she says. “They were like, ‘She’s not taking this seriously.’” (Except, uh, then she set the American course record, so…)

Somebody who, obviously, swears like a sailor and dances awkwardly on Instagram, who dresses up like a turkey, and viral-tweets about getting mansplained on an airplane. (“He starts telling me how I need to train high mileage & pulls up an analysis he’d made of a pro runner’s training on his phone. The pro runner was me. It was my training. Didn’t have the heart to tell him.”)

Somebody who makes every middle-aged mom-runner I know swoon like a Swiftie and say: “OMG! YOU HUNG OUT WITH MOLLY SEIDEL!!?” Middle-aged dad-runners, too. “I saw her once in Golden Gate Park!” my friend Dan fanboyed when he heard. “I waved!” Did she wave back? “She smiled,” he says, “while casually laying down 5:25s.”

And somebody who was as outraged as I was that I bought a $16 tube of French toothpaste from my hip Flagstaff motel. (It was 10 p.m.! It was all they had!) “For that price it better contain top-shelf cocaine,” she texted. Lest LetsRun commenters take that tidbit out of context: It’s a joke. It’s, in part, what makes Molly America’s most relatable pro runner: She’s not afraid to make jokes. (While we’re at it… Don’t knock her for smoking a little legal weed, either. That’s so 2009. Per the World Anti-Doping Agency: Cannabis is prohibited during competition, not at a Christmas party two months before it. Per Molly: “People would be shocked to know how many pro runners smoke weed.”)

I can’t believe I never asked to see it. Molly’s medal. A real, live Olympic medal. Maybe because it was tucked into a credenza along with Matt’s menorah and her maneki-neko cat figurines from Japan. But I think it was because hanging out with Molly felt so…normal, I almost forgot she’d won one.

People think elite distance runners have to be one-dimensional, she says. That they have to be sculpted, single-minded, running-only robots. “Because that’s what the sport has been,” she says.

Molly falls for it, too, she says. She scrolls the feeds, sees her fellow pros living seemingly perfect lives. She wants everyone to know: She’s not. So much so that she requested we not print the photos originally commissioned for this story, which were taken when she was at the lowest of lows. (“It’s been...refreshing...to be pretty open and real with Rachel [about] the challenges of the last year,” she wrote in an email to Runner’s World editors. “But the photos [were taken at] a time when I was really struggling and actively trying to hide how bad my eating disorder had become.”)

Molly finds the NYC Marathon high-five thing comical but indicative of a more serious issue in elite running: It takes itself too seriously. It’s too…elitist. Too stilted. “Running a marathon is a pretty freaking cool experience!” If you’re not having fun, she asks rhetorically, what’s the point? Still, she admits, she isn’t always having fun. Though you wouldn’t know it from her Instagram. “Oh, I’m very good at making it seem like I am,” she says.

She used to enjoy social media when it was just her friends. Before she gained 50,000 followers in a single day after the trials, and some 70,000 on Strava. Before the pandemic, before the Olympics. Keeping up with content became a toxic chore. “You feel like you’re just feeding this beast and it’s never going to stop,” she says. She’s taken to deleting the app off her phone, reloading it only to fulfill contractual agreements and post for her sponsors, then deleting it again.

As much as she hates having to post, she enjoys plugging products the only way that feels natural: through parody. As does Izzy, her influencer sister, who, like Molly, prefers to skewer rather than shill (à la their idea behind their joint Insta account: @sadgirltrackclub). “The classic influencer tropes make me want to throw up,” she says (perverse pun as a recovering bulimic not intended). “New Gear Drop!’ or ‘This is my Outfit of the Day!’ Cringe. “Hot Girl Instagram is not how I identify,” she says.

Nor is TikTok. “Sponsors tell me all the time: You should TikTok! I’m like, ‘I am not doing TikTok.’ I know how my brain works. They’ll say, ‘We’ll pay you less if you don’t’—and I’m, like, I don’t care.”

And to those sponsors who ghosted her after she returned to eating disorder treatment, good riddance. “Michelob dropped me like a bad habit,” she says. “Whatever. You have watery-ass beer anyway.”

To those who have stood by her, though, she’s utterly devoted. Pissed she couldn’t wear the Puma panther head to toe in Tokyo, Molly took off her Puma Deviate Elites and tied them over her shoulder, obscuring the Nike logo on her Olympic singlet for all the world to see. Or not see. “Nike isn’t paying my fucking bills.”

The love is mutual, says Erin Longin, a general manager at Puma. After decades backing legends like Usain Bolt, Puma was relaunching road running and wanted Molly as their guinea pig. “She’s a serious athlete and competitor, but she also has fun with it,” says Longin. “Running should be fun. Molly embodies that.” At their first meeting, in January 2020, Molly made them laugh and nerded out over their new shoes. “We all left there, fingers crossed she’d sign with us,” says Longin.

Come February, they all flipped out. Longin was watching the trials, not expecting much. And then: “We were all messaging, “OMG!!” Then Molly killed in London. Medaled in Tokyo. “What she did for us in that first year…” says Longin. “We couldn’t have planned it!”

Then came the second year, and the third, and throughout it all—injuries, eating disorder treatment, missed races, missed opportunities—Puma hasn’t flinched. “It’s easy for a company to do the right thing when everything is going great,” Molly posted in April, heartbroken from her couch instead of Heartbreak Hill. “But it’s when the sh*t hits the fan and they’re still right there with you….” She received 35,000 hearts—and a call from Longin: “You make me feel so proud.”

Does it matter to Puma if Molly never places—never races—again? “Nope,” Longin says.

My last afternoon in Flagstaff, it’s cloudy skies, still freezing. I find Molly on the high school track wearing neoprene gloves, black puffy coat, another pair of Pumas. Her breath is white, her cheeks red. Her legs churning in even, elegant strides. Upright, alone, at peace, backed by snow-dusted peaks. Running itself is what matters, not racing, she tells me. “I honestly don’t give a shit about winning,” she says. All she wants—really wants, she says—is to be healthy enough to run until she’s old and gray.

Molly’s favorite runner is one who didn’t get to grow old. Who made his mark decades before she was born: Steve Prefontaine. “Pre raced in such a genuine way. He made people feel something,” she says. “The sports performances you truly remember,” she adds, “are the ones where you see the struggle, the work, the realness.”

Sounds familiar. “I hate conversations like, ‘Who’s the GOAT?’” Molly continues. “Who fucking cares? Who’s got the story that’s going to get people excited? That’s going to make some kid want to go out and do it?”

I know one of those kids: My best friend’s daughter, Quinn, a rising track phenom in Oregon, who has dealt with anxiety and OCD tendencies. She has a picture of Molly Seidel, and her times, taped to her bedroom wall. This past May, Quinn joined Nike’s Bowerman Club. She was named Oregon Female Athlete of the Year Under 12 by USATF. She wants to run for Notre Dame.

“Quinn loves running more than anything,” her mom tells me, texting photos of her elated 11-year-old atop the podium. “But I don’t know…” She’s unsure about setting her daughter on this path. How could she not, though? It’s all Quinn wants to do. Maybe what Quinn, too, feels born to do.

It’ll be okay, I tell her, I hope. Quinn has something Molly never had: She has a Molly.

Molly and I catch up via phone in June. A team of doctors in Germany has overhauled her biomechanics. She’s been running 110 miles a week, feeling healthy, hopeful. Happy. A month later, severe anemia (and accompanying iron infusions) interrupts her summer racing schedule. She cancels the couple of 10Ks she had planned and entertains herself by popping into the UTMB Speedgoat Mountain Race: a 28K trail run through Utah’s Little Cottonwood Canyon—coming in second with a 3:49:58. Molly’s focus is on the Chicago Marathon, October 8th; her first major race in almost two years.

Does it matter how she does? Does it matter if she slays the Olympic Trials in February? If she makes it to Paris 2024? If she fulfills her childhood dream and brings home gold?

Nah. Not if—like Matt, like Puma, like, finally, even Molly herself—you see Molly the Runner for who she really is: Molly the Mere Mortal. She’s the imperfect one who puts it perfectly: What matters isn’t her time or place, how she performs on the pavement. Or social media posts. What matters—as a professional athlete, as a person—is how she makes people feel: human.

She’d been finally—finally—fit on all fronts; ready to race, ready to return. She needed Nagoya. And then, nothing. “It feels like I’m back at the bottom of the well,” says Molly, driving home from Whole Foods in her Toyota 4Runner. “This last year-and-a-half has been so difficult. It’s just been a lot of doubt. How do I approach this, as someone who has now won a medal? Like, man, am I even relevant in this sport anymore?” She pops a piece of gum in her mouth. I wait for her to offer me some, because that’s what you do with gum, but she doesn’t. She’s so in her head. “It’s hard when you’re in the thick of it, you know, to figure out: Why the fuck do I keep doing this? When it just breaks my heart over and over and over again?”

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

Des Linden and Kara Goucher Demystify Drug Testing Requirements in Pro Running

Specifically, how the “whereabouts” policy really works.

Drug testing in professional running has made plenty of headlines over the years—even as the process itself has remained somewhat mysterious to spectators of the sport. But on this week’s episode of Nobody Asked Us, Des Linden and Kara Goucher pulled back the curtain and offered a rare peek inside anti-doping practices, including the scoop on “whereabouts” policy.

Linden began the conversation by recalling that she’d been drug tested in the early morning of the previous weekend. “We could demystify the process because I think… people don’t hear too much about it except as just a quick tweet or [via] somebody who hasn’t really been through it or has a story that is uninformed because they heard it from someone who heard it from someone,” said Linden. “We’ve been through this a number of times so I thought we could talk about the process a little bit.”

According to the World Anti-Doping Agency, athletes who are part of the Registered Testing Pool (those operating at the highest level of their sport) must submit to regular drug testing year-round. To accommodate the testing, these athletes must offer up their home address (or address for their overnight accommodations), competition schedules, and any alternative locations where they may be found. They also must provide a 60-minute time slot for each day where they will be available for testing.

“You have one hour where they will not inform you that you’re there or that they’re looking for you. They will just knock and you have to be where you put your whereabouts for the day,” said Linden. The WADA stipulates that those who miss the test may be liable for, you guessed it, a ‘missed test,’ and infraction that can lead to bans.

Linden shared that her hour window is first thing in the morning when she knows she’ll have to pee. “Five to six a.m. is my hour window usually at home, and then they wake me up and I have to go to the bathroom right away,” she said. Goucher shared that she also opted for a morning slot for drug testing until her son was born. “After I had Colt, I did change it to the afternoon—just because there were many a time where he got woken up… so I did change it to like two because I was always home by then and just napping or playing with him,” she shared.

The WADA also reserves the right to test athletes directly post-race. Goucher and Linden said this process often involves waiting around after you’ve crossed the finish line until you have to go. In this case, drug testers follow athletes into the bathroom. The process can be awkward—especially if it’s a numbers one and two kind of situation. “They’re like tuck your shirt up into your bra and pull your pants down, I’m going to watch,” explained Kara. “At first it feels weird, but later in life you’re like ‘Pfff, whatever. Here we go.’”

Once, athletes had to fax their schedules to the governing bodies for drug testing, according to Linden and Goucher. But nowadays, the test scheduling happens via an app. “If you’re in a certain pool… then you have to put in one hour where you’re going to be and they can’t inform you,” said Linden. “And then you have the rest of the day where you sort of give them an idea of where you are and how they can get a hold of you.” They may choose to test runners outside their chosen hour; however, they must work with the athlete to find a location that works, per the two runners’ conversation. Goucher said that a drug tester once met her at a preschool orientation, for example.