Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #Badwater

Today's Running News

U.S. Olympian Jenny Simpson completes 7 marathons in 7 days

Two weeks after finishing 18th at the New York City Marathon in 2:31:54, U.S. Olympian Jenny Simpson tackled one of the most gruelling challenges: the Great World Race, which involves running seven marathons on seven continents in seven days.

The decorated middle-distance runner was a late addition to the event that offered a fitting end to her storied career. Over her career on the track, Simpson won four medals at major championships, including an Olympic bronze in the 1,500m at Rio 2016 and a gold medal at the 2011 World Championships in Daegu, South Korea.

The Great World Race kicked off on Nov. 14 at Wolf’s Fang, Antarctica and concluded on Nov. 20 in Miami. Simpson completed the challenge with the following times:

Antarctica: 3:31

South Africa: 3:15

Australia: 3:12

Turkey: 3:11

Istanbul (overlap leg): 3:15

Colombia: 3:16

Miami: 5:15

Simpson finished fourth in the women’s competition. The week-long-race was won by Ashley Paulson, a two-time Badwater 135 champion, while the men’s race went to David Kilgore after Ireland’s William Maunsell withdrew on the fifth day–four days after he set a continental marathon record on Antarctica.

Reflecting on her last-minute decision to join, Simpson said the invitation was an irresistible opportunity to challenge herself one last time. Initially, it was announced the New York City Marathon would be her final race, but the chance to “run around the world” was too much to pass up for Simpson.

“I have never in my life been so happy to see a finish line,” Simpson wrote on Instagram. “Seven marathons in seven days, plus around the world in one week! My body is surprisingly resilient and I’m so glad I did it.”

Participation in the jet-setting event doesn’t come cheap—the USD $52,000 entry fee covers charter flights, in-flight meals and emergency evacuation coverage for the Antarctica leg. Despite the cost and the gruelling schedule, the event is a bucket-list challenge for many hardcore marathoners.

by Marley Dickinson

Login to leave a comment

Leadville 100 sees long-standing course record fall

This year's edition of "the race across the sky" saw history-making performances on both the men's and women's sides

Leadville 100, known as the “race across the sky” for its stunning vistas as it traverses the Colorado Rockies, has been a staple in the ultrarunning community since its inception in 1983. This year’s event saw blistering performances in both the men’s and women’s races, with popular coach and author David Roche taking 16 minutes off the long-standing course record, and women’s race winner Mary Denholm recording the second-fastest time ever at the event.

The 100-mile race has runners climbing nearly 4,800 metres of elevation gain over rugged mountain trails, and runners begin and end in Leadville, Colo.

Women’s race

Denholm took off hot and dominated the competition from start to finish. By the halfway point, she had built an insurmountable 50-minute lead. She crossed the finish line in 18:23:51, securing the second-fastest time ever recorded for the women’s race, just short of legendary Ann Trason’s mark of 18:06:24, set in 1994. Denholm was followed by fellow American runners Zoe Rom in 21:27:41, and Julie Wright in 21:48:57.

Alberta’s Ailsa MacDonald and Molly Hurford of Ontario were initially in contention for podium positions, but both faced challenges that saw them taking DNFs. Hurford left the race after suffering a badly sprained ankle, and MacDonald after dealing with unrelenting gut issues.

Men’s race

Like Denholm, Roche set a fast pace from the start and built on his lead throughout the race. His time of 15:26:34 took more than 16 minutes off the previous course record, set by Matt Carpenter in 2005. He was followed in by U.S. ultrarunners Adrian Macdonald in 15:56:34, and Ryan Montgomery in 16:09:40.

Pete Kostelnick, a well-known ultrarunner famous for completing the fastest transcon run of the U.S. in 2016 (42 days, six hours and 30 minutes), made a remarkable return to running earlier this year after recovering from a severe car accident that resulted in multiple pelvic fractures. In May, Kostelnick finished the Cocodona 250, followed by Badwater 135 only a few weeks ago; he finished Leadville 100 in 24:30:18.

Calgary’s Reiner Pauwwe took the 28th overall position (24th man) in 22:16:59.

by Keeley Milne

Login to leave a comment

Leadville Trail 100 Run

The legendary “Race Across The Sky” 100-mile run is where it all started back in 1983. This is it. The race where legends are created and limits are tested. One hundred miles of extreme Colorado Rockies terrain — from elevations of 9,200 to 12,600 feet. You will give the mountain respect, and earn respect from all. ...

more..."It’s all about seeing what I can do" – 74 runners cross the finish line after tackling temperatures over 100F in Death Valley ultra

The race is frequently billed as the world's toughest foot race

What is the toughest race in the world? If you're a trail runner, the obscure Barkley Marathons probably comes to mind with its overgrown terrain and mind-boggling 54,200 feet of accumulated vert. But for those whose preferred mode of transport is road running shoes? There's nothing quite like the Badwater 135 which wrapped up yesterday morning in typically grueling conditions.

An impressive 74 runners out of 97 hopefuls who took off from the starting line in Death Valley National Park had crossed the finish line Wednesday morning after running through daytime temperatures as high as 120 degrees Fahrenheit (48.8C) and nighttime lows above 100F (37.7C). A recent heat wave sweeping the western states has been blamed for several deaths in National Parks including one in Death Valley on July 6 when a motorcyclist succumbed to heatstroke.

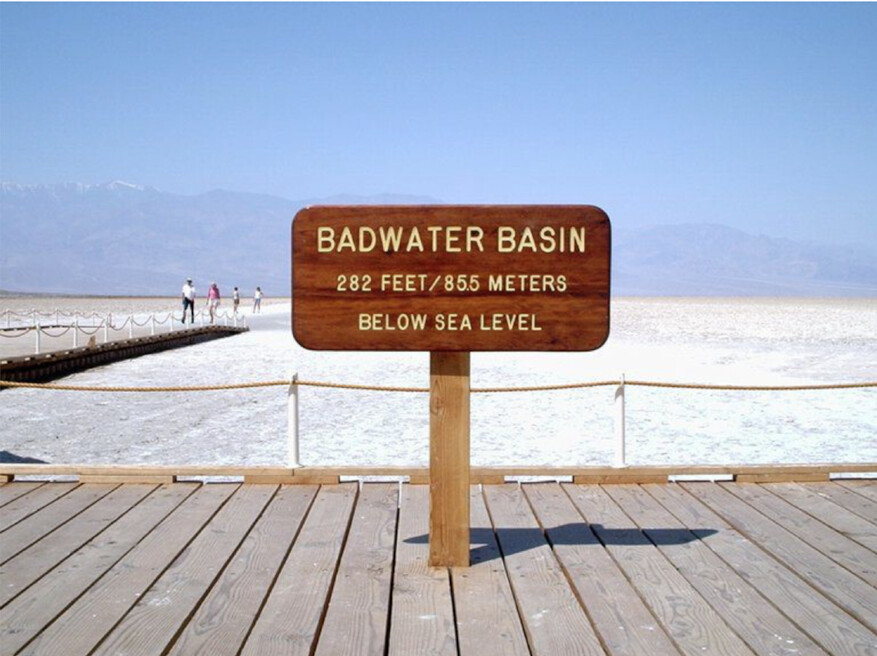

In addition to extreme heat, these hardy runners encountered higher humidity than normal as they set off during a light rainstorm. The course took them from Badwater Basin, the lowest point in North America, to the trailhead of Mount Whitney at 8,300 feet and over three mountain ranges with a total elevation gain of 14,600 feet.

“For me it’s all about seeing what I can do, you know, testing my own limits, seeing how well I can do these extreme things,” Alabam runner Jessica Jones tells the Associated Press.

In the end, it was Colorado runner Shaun Burke, 37, of Durango who took first place in the men’s division with a time of 23:29:00 while 52-year-old Line Caliskaner of Norway led the women’s division, at 27:36:27 and finished second overall. We're willing to bet these runners had done some serious heat training and had some well-rehearsed hydration strategies in place to survive this course.

Race organizers do not provide aid stations or support during the race, which has been an annual event since 1987. To date, there have been no fatalities at the Badwater 135.

Login to leave a comment

Harvey Lewis races Badwater 135 for the 13th time in a row

This year’s edition of Badwater 135, dubbed the “world’s toughest foot race,” kicked off on Monday, plunging runners into the brutal extremes of California’s Death Valley. This year’s race featured the return of fan favorites, including Backyard Ultra world champion Harvey Lewis, a two-time Badwater winner making his 13th consecutive appearance, and fellow American Pete Kostelnick, also a two-time champion, who made a remarkable comeback after a severe car accident in Leadville. American Shaun Burke claimed the overall victory amidst the scorching heat, while Norwegian Line Caliskaner triumphed in the women’s category, finishing an impressive second overall.

The 135-mile (217km) race kicks off at the Badwater Basin, which, at 85 metres below sea level, is the lowest point in North America. This year’s race saw temperatures hitting a scorching 51 degrees Celsius. Runners who finish under the 48-hour mark earn the prestigious Badwater 135 belt buckle.

In 2023, Viktoria Brown of Whitby, Ont., was the only Canadian in the field of 100 runners and finished in 30:11:52 securing fourth among the women and claiming 13th place overall. This year’s race saw two Canadians joining the ranks—Frances Picard of Quebec, and Hannah Perry from Canmore, Alta.

Men’s race

Last year’s men’s champion, Simen Holvik of Norway, led for much of the race—in 2023, Holvik was second to U.S. runner Ashley Paulson, who finished first overall and took two hours off her own women’s course record. Burke, who received a late invite to the event in June, steadily closed the gap, eventually overtaking him before the 108-mile timing point. Holvik did not finish the race, leaving Burke unchallenged for the remainder.

Burke completed Badwater for the first time in 2023, when he was sixth overall and fourth among the men. Spanish runner Iván Penalba Lopez claimed the second men’s spot (third overall) in 28:06:34 in his third finish of the race, and Michael Ohler of Germany completed the men’s podium and third man (fourth overall) in 28:24:25. Kostelnick succeeded in finishing his come-back race, crossing the line in 35:28:55; Lewis followed in 36:41:22.

Picard, who was tackling the race for the first time, was still on course at the time of publication.

Top men

Shaun Burke (U.S.) 23:29:00 Iván Penalba Lopez of Alfafar (Spain) 28:06:34 Michael Ohler (Germany) 28:24:25

Women’s race

Caliskaner became the first Norwegian woman to complete the event, finishing second overall. An accomplished ultrarunner, in 2023 52-year-old Calinskaner won both the Berlin Wall Race (100 miles), and the Thames Path 100-miler. She maintained a narrow lead over Micah Morgan of the U.S. early on and added to her lead as the race progressed. Caliskaner finished in 27:36:27, over two hours ahead of Morgan, who finished in 29:11:28, second among the women and fifth overall.

Josephine Weeden of the U.S. rounded out the women’s podium in 33:26:37. Absent from this year’s race was American Ashley Paulson, who won the women’s race for the past two years and took the overall title last year. Alberta’s Perry was still on course at the time of publication but had passed through the 108-mile aid station in 29 hours and 51 minutes.

Top women

Line Caliskaner (Norway) 27:36:27 Micah Morgan (U.S.) 29:11:28 Josephine Weeden (U.S.) 33:26:37

by Running magazine

Login to leave a comment

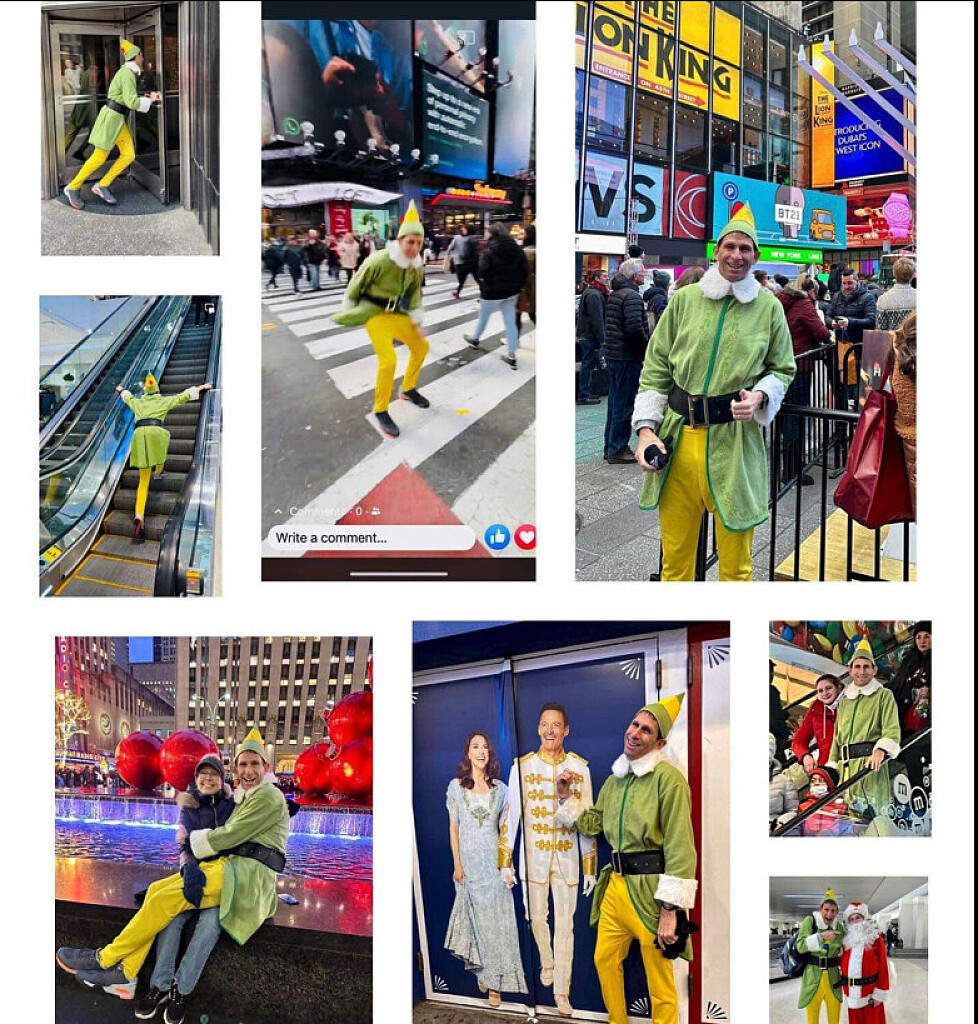

Buddy the Elf Shatters Guinness Record with Help from Pro Ultramarathoner

Jason Homorody was gunning for the fastest half marathon as a movie character when he ran into Harvey Lewis.A modern-day staple of road running is unexpectedly coming across people running in costume either for a charity or in the hopes of setting a Guinness World Record, but sometimes, these costumed individuals discover the unexpected themselves.

On Sunday, Jason Homorody, 50, was beginning his quest to break the record for the fastest half marathon time while dressed as a movie character—Buddy the Elf from Elf in his case—at the Warm Up Columbus Half Marathon when he received some surprising support from a fellow runner. While attempting to break the previous 1:30:42 record, Homorody, who—obviously—loves Elf and regularly wears the costume around to “cheer people up,” was joined by Harvey Lewis, the current backyard ultramarathon record holder and well-decorated ultrarunner, who has won the likes of the Badwater 135 and USATF 24-Hour National Championships.

“[He] came up on my shoulder and asked me what pace I was going for,” Homorody told Runner’s World. “Once I answered some questions, he asked if he could run with me. Honestly, at first, I had no idea who he was. But he ran with me the entire race.”Homorody also said Lewis helped him with hydration during the race. “When we would pass the water stop on the course, he was asking if he could get me anything. He kept encouraging me to get water because I think he was concerned about me overheating in my costume,” Homorody said, adding that the two talked about Lewis’ upcoming races during the event.“I was picking his brain about ultramarathoning,” Homorody said. “I knew he recently had a crazy backyard ultra world record, and I was asking if he was almost falling asleep at any point while running, and he said yes.”

So, did the support of an ultramarathoner ultimately push Homorody to his goal? It seems like it, as Buddy the Elf crossed the finish line in 1:25:44, besting the previous record by more than 5 minutes.

“[Lewis] was just a very down-to-earth guy, and he seemed genuinely excited to help pace me to my world record attempt,” Homorody said.

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

Viktoria Brown smashes her own 6-day record

Whitby, Ont.’s Viktoria Brown has conquered the multi-day racing scene, and she just keeps getting better. Brown ran a whopping 747 kilometers at the EMU 6-day Race in Hungary, besting her previous Canadian 6-day record of 736 km. Runners competed on an 898.88 meter-long certified road loop that was 100 per cent asphalt.

Brown is well-known for her many multi-day records, and for recently competing at Badwater 135, the scorching ultra in Death Valley, Calif., where she finished fourth.

She holds the 48h Canadian record (363 km), and the 72-hour Canadian record (471 km), and was the owner of the 72h WR, recently bested by Danish athlete Stine Rex. She entered EMU having trained minimally, and became ill with salmonella poisoning partway through the event.”My goal at this race was to hit 800 kilometers,” Brown told Canadian Running.

“Only three women have ever done that, and I believe that without the salmonella poisoning, I would have hit it,” she said. “I only ran 56 km on day five, while I ran 110+ km on all other days, including 151 km on day six.”

Ultras are often a test in troubleshooting, and this is only magnified by multi-day racing.”Vomiting started at noon on Monday (the start of day five) and went on all day until I went down for sleep around 10 pm,” Brown said. “I got up at 3:30 am, was back on the course at 4 a.m., and ran straight until the race ended, 32 hours later.” Brown says she was extremely lucky to have a medical doctor on her crew, whom she credits with bringing her back from illness.

To combat the salmonella, Brown slept for six and a half hours to reset her body.”I wasn’t throwing up anymore, although my body was completely empty and I still had diarrhea,” she said. “But that meant that five-10 per cent of the intake was absorbed, so we could slowly start to refuel.” Brown had to walk until late afternoon on Tuesday, both because her body was recovering and due to intense heat during the daytime.”By late afternoon I was able to start jogging, then running, and then even running relatively fast by the end.”

Brown says she felt she was unable to train for this race, but her excellent base fitness proved to be enough. “After the 48h World Championship in August (that I won) I had some slight pain under my right knee, so I could only do minimal training,” she explains.”By the time the injury healed, I caught a cold, so then I couldn’t train at all. Maybe being more rested for this race helped more than the training would have,” said Brown.

Post-race, Brown says it’s hard to catch up on sleep, but she has a surprising lack of soreness and no blisters.”My body is in great shape, but my mind will need some serious recovery,” the runner said. “These races are extremely demanding mentally.” Brown will compete next at the Kona Ironman World Championship in Hawaii in October, and later at the 24-hour world championship with Team Canada in Taiwan.

by Keeley Milne

Login to leave a comment

Hardrock 100 preview: will Courtney Dauwalter do it again?

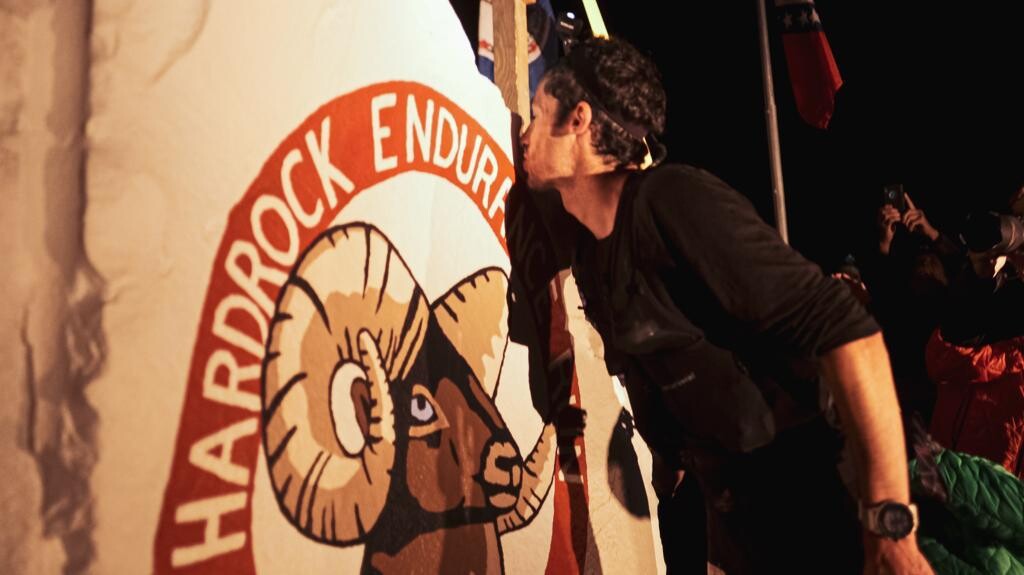

The Hardrock Hundred Mile Endurance Run (HR100), known for its high altitude, deep elite field and challenging entry process, begins Friday at 8:00 a.m. E.T. This year’s event, the first ever to be live-streamed, promises to be a thriller. Runners will encounter over 10,000 metres of elevation gain while facing extreme weather conditions, navigating treacherous terrain and attempting to avoid altitude sickness.

Only 140 participants get to line up at Hardrock each year, and this year’s contenders include the remarkable Courtney Dauwalter, fresh off a jaw-dropping performance and course record at the Western States 100, and other well-known elites. The race will be live-streamed on the Run Steep Get High YouTube channel. Here’s what you need to know to follow along.

HR100 both begins and ends in Silverton, Co., and athletes are above 3,300 metres elevation for much of the race. It was founded in 1992 as a tribute to the miners who used to follow “their mules and instincts, prospecting the San Juans for gold, silver, and other metals,” the race website explains. With a finishing cutoff time of 48 hours, athletes know they are in for a long haul. The course switches directions every year, and this year runners are moving counter-clockwise around the looped course.

The women’s race

All eyes are on the phenomenal Dauwalter this year (but when are they not?) after a stunning performance three weeks ago at Western States, where she set a blistering new course record (78 minutes faster than Canadian Ellie Greenwood’s from 2012) and placed fifth overall. Canada’s Stephanie Case, who was second last year, has withdrawn from this year’s event. 60-year-old legendary ultra machine Pam Reed of Jackson Hole, Wyo., will be tackling the third part of her WSER/Badwater 135/HR100 triple this year.

Leadville, Colo.-based Dauwalter holds the course record for HR100 in the clockwise direction (26:44) from 2022; this year runners will move counter-clockwise, and that course record is 27:18 for women, set by Diana Finkel in 2009, and Dauwalter will most certainly be looking to challenge that time. Will her legs be tired? Will she win the entire thing? We can’t wait to find out.

Also from Leadville, 23-year-old trail phenom Annie Hughes won the Run Rabbit Run 100-Miler and High Lonesome 100 Mile in 2022, and the Leadville 100 Mile in 2021. She’s a high-altitude ultrarunning champ, and has also compiled some wins in really long races–she won the Cocodona 250 Mile in 2022 and Moab 240 in 2021.

If you haven’t heard of France’s Claire Bannwarth, it’s time to brush up: she was the first woman in the 432-kilometre 2022 Winter Spine Race (by more than 24 hours), and will be making her North American racing debut at HR100. Bannwarth races prolifically and runs long–she will be jumping into the Tahoe 200 Mile race a week after HR100.

Colorado’s Darcy Piceu, fresh off the waitlist, is a veteran of HR 100, with the 2023 edition being her 10th running. Piceu boasts three wins and five second-place finishes, and she was fourth in 2022.

The men’s race

With Kilian Jornet, last year’s winner (and course record holder in the clockwise direction) not returning this year, the podium seems up for grabs. None of the other top four men from 2022 will be headed to the San Juans, but a very accomplished group of athletes will be lining up and fans will be eager to see who holds up to the HR100 test.

Ohio’s Arlen Glick is a master of the 100-mile distance, running 12:57 to win the Umstead 100-miler in April and taking a speedy third at October’s Javelina 100. Like Dauwalter, Glick raced at WSER last month. He placed 14th, while he took third in 2022. Glick will be a hot contender and fascinating to watch at HR100.

California-based Dylan Bowman is a Hardrock veteran, placing second at the 2021 edition. Bowman has had a lower racing profile in the past year while working on Freetrail, a media business and trail running community. He’s been training in the San Juans pre-race and is eager to showcase his ability.

France’s Aurélien Dunand-Pallaz has over 10 years of ultrarunning success, but gained notoriety in 2021 when he took second at UTMB and won Spain’s Transgrancanaria. He missed the 2022 edition of HR100 for the birth of his child and is a favourite in his debut this year.

Oregon-based trail running legend Jeff Browning will be taking on his sixth Hardrock at age 51. Browning won in 2018, and finished fifth the past two years. In October, Browning won the Moab 240 in 57 hours, and more recently, he showcased his fitness by winning the Bighorn 100.

by Keeley Milne

Login to leave a comment

Hardrock 100

100-mile run with 33,050 feet of climb and 33,050 feet of descent for a total elevation change of 66,100 feet with an average elevation of 11,186 feet - low point 7,680 feet (Ouray) and high point 14,048 feet (Handies Peak). The run starts and ends in Silverton, Colorado and travels through the towns of Telluride, Ouray, and the ghost town...

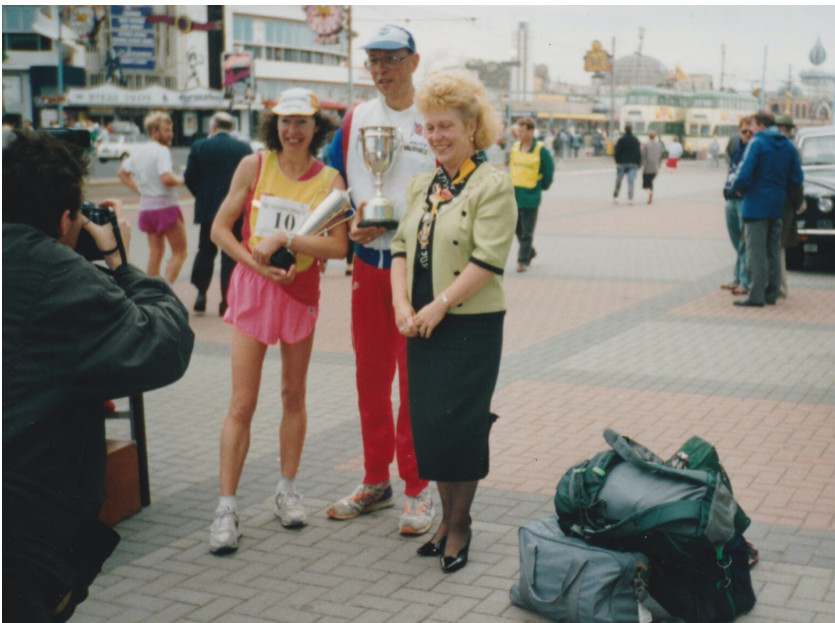

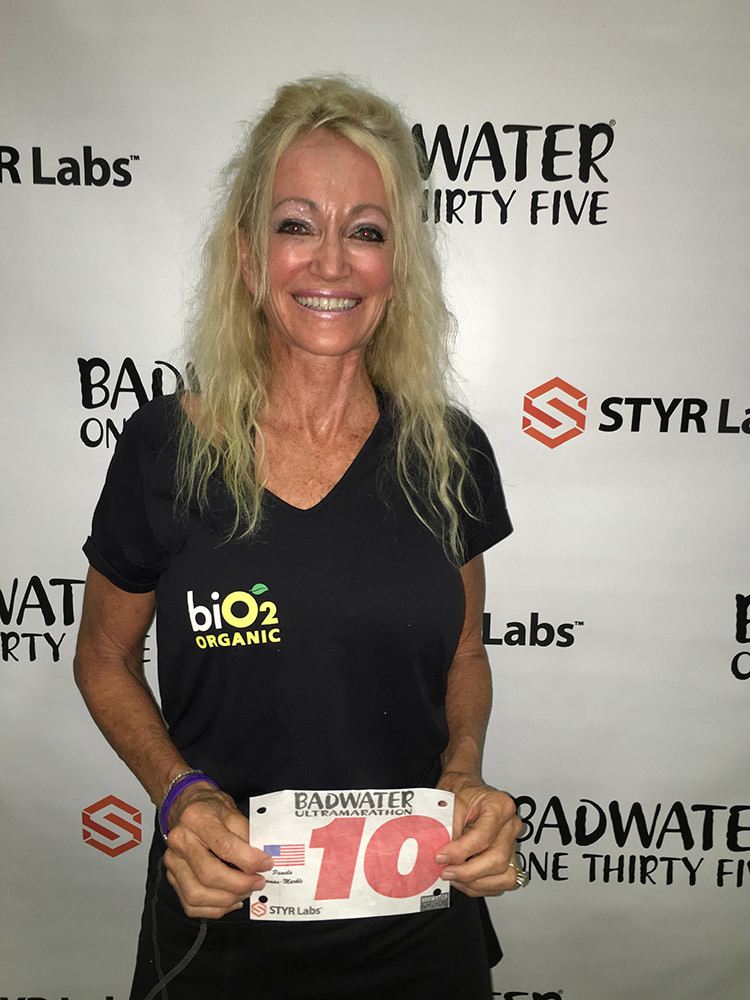

more...Ashley Paulson wins Badwater 135, smashing her own course record

The defending women's champion chopped nearly two-and-a-half hours off last year's time to finish first overall.

Defending Badwater 135 women’s champion Ashley Paulson has smashed the women’s course record she set last year, chopping nearly two and a half hours off her 2022 time to finish first overall at this year’s race.

Paulson, of St. George, Utah, completed the course—an infamously hot and gruelling 135-mile (217-km) run through California’s Death Valley to Mount Whitney—in 21:44:35. In doing so she not only demolished the women’s record she set last year (24:09:34) but finished more than 20 minutes ahead of this year’s men’s champion, Simen Holvik of Norway (22:28:08). Temperatures during the race have been known to soar well above 100 F (37 C).

Placing second in the men’s category and third overall was last year’s winner, Yoshihiko Ishikawa of Japan (23:52:29), who has two Badwater 135 victories under his belt. He was followed by fourth-place finisher and second-place women’s runner Sonia Ahuja of Thousand Oaks, Calif., who trailed Paulson by nearly two hours, finishing the course in 25:42:51. Rounding out the top five finishers was 2021 champion Harvey Lewis of Cincinnati, who completed his 12th Badwater 135 in 27:26:49, finishing third among the men. Rounding out the women’s podium was Maree Connor of Lambton, Australia (27:49:24).

Viktoria Brown, the only Canadian in the field of 100 runners, finished strong, running 30:11:52 to place fourth among women and claim 13th place overall. It’s been a stellar year for the Whitby, Ont., ultrarunner, who in March broke her own 48-hour Canadian record and 72-hour world record while competing at the GOMU (Global Organization of Multi-Day Ultramarathoners) six-day world championships in Policoro, Italy.

With her commanding victory this year, Paulson becomes the first woman to win back-to-back races at Badwater since Japan’s Sumie Inagaki won the event in 2011 and 2012.

Paulson’s win last year came amid some controversy. In 2016, the professional runner and triathlete accepted a ruling from the United States Olympic Committee National Anti-Doping Policies (USADA) banning her from competition in triathlon events for six months, the result of an anti-doping rule violation. She had a positive result for ostarine, a selective androgen receptor modulator (SARM), during a random sampling.

Follow-up tests found ostarine in a contaminated supplement the athlete was taking. In an analysis of Paulson’s GPX files and other data, Derek Murphy, who runs the site marathoninvestigation.com, concluded that her Badwater data was clean and showed no evidence of cheating.

This year’s race, which started Tuesday at 8 p.m. PDT, and lasts 48 hours, marks the 46th running of the Badwater 135. Considered by many to be the world’s toughest foot race, the ultramarathon begins at 85 metres below sea level—the lowest elevation in North America—and takes runners up to 2,548m of altitude.

by Paul Baswick

Login to leave a comment

Badwater 135

Recognized globally as "the world’s toughest foot race," this legendary event pits up to 90 of the world’s toughest athletes runners, triathletes, adventure racers, and mountaineers against one another and the elements. Badwater 135 is the most demanding and extreme running race offered anywhere on the planet. Covering 135 miles (217km) non-stop from Death Valley to Mt. Whitney, CA, the...

more...This Ultrarunner Is Living in a Glass Box for 15 Days

During the experiment, Krasse Gueorguiev will have only a bed and a treadmill

Krasse Gueorguiev, a Bulgarian ultramarathon runner, will spend 15 days in a glass box in a park in Sofia, Bulgaria, to raise money to help young people battling addiction.

Gueorguiev, a motivational speaker and charity ambassador, has run nearly 30 ultramarathons worldwide, from the Arctic to Cambodia, including the 135-mile Badwater Ultramarathon in Death Valley, California.

"I want to challenge myself," Gueorguiev told Reuters. "I want to show when you put someone in the box how psychologically they change."

Proceeds from the stunt will be used for several projects aimed at preventing addiction for children under 18, not just for drugs and alcohol—the runner also hopes to help teens avoid addiction to things like social media and energy drinks.

On Sunday, the runner was placed in a box with three glass walls on a pedestal in front of the National Palace of Culture in Sofia (Bulgaria's capital). During the experiment, Gueorguiev will have only a bed and a treadmill, with no access to books, a computer, or a phone. He will only be allowed to speak to members of the public for 30 minutes each day.

"This is not a physical experiment; it is a psychological experiment," he said.

If the stunt sounds familiar, you may remember magician David Blaine undertaking a similar experiment in 2003. The illusionist spent 44 days in a glass box suspended over the River Thames in London.

The stunt was met with much public outcry, though, unlike Gueorguiev, Blaine's time in the box was for entertainment purposes only. He endured drumming from the crowd in the evening hours and having eggs and other items hurled at his temporary home. The magician seemingly took it all in stride. "I have learned more in that box than I have learned in years. I have learned how strong we are as human beings," Blaine told reporters after emerging from the box. Upon completing the 44 days, Blaine was noticeably thinner, with depleted muscle mass and a thick beard.

Only time will tell if a similar fate inside the box will befall Gueorguiev.

This is also not the ultrarunner’s first attempt at performing a stunt in the name of goodwill. In 2019, Gueorguiev ran about 750 miles through Bulgaria, North Macedonia, and Albania to urge the governments to build better infrastructure, and in January of 2018, Krasse ran for 36 hours straight on a treadmill at a Sofia shopping mall.

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

Viktoria Brown breaks 72-hour world record, 48-hour Canadian best in Italy

Earlier in March, Whitby, Ont., runner Viktoria Brown broke her own 48-hour Canadian record and 72-hour world record while competing at the GOMU (Global Organization of Multi-Day Ultramarathoners) six-day world championships in Policoro, Italy. Brown ran 364 km over 48 hours and 475 km after 72, beating her two previous records by 11 km and 8 km, respectively. She finished the six-day event with a grand total of 684 km to take home the women’s individual gold medal.

The event in Italy marked the first six-day world championship organized by GOMU, which was founded in 2021. Brown is a vice president, as is Greek ultrarunning legend Yiannis Kouros; Canadian ultrarunning pioneer Trishul Cherns is president. The organization held its first world championship event—a 48-hour competition—in New Jersey in September 2022, and Brown and the team are looking to add 72-hour and 10-day races into the mix in the near future.

Canada didn’t send a team to the GOMU worlds, so Brown competed for Hungary, where she also holds citizenship. She helped lift the Hungarian women to the team world championship to pair with her individual gold medal. Going into the event, Brown’s Canadian 48-hour record stood at 353 km, which she ran in June 2022 at the Six Days in the Dome event in Wisconsin. After two days of running in Italy, she had eclipsed her PB to add another 11 km to her national record, which now stands at a whopping 364 km.

Up next was the 72-hour mark, and Brown had her eyes on her world record of 467 km. She ran that amazing result at the same race where she posted her 48-hour best last June. Just like she did in Wisconsin, Brown charged forward after securing her 48-hour record, and eventually toppled her 72-hour best, too, with a tally of 475 km.

At that point, Brown already had two records in the books, but she was still only halfway through the six-day race. She carried on for another three days, eventually finishing with a phenomenal winning result of 684 km. That’s an amazing total, but even more incredible is the fact that it’s more than 50 km shy of Brown’s six-day PB (and, you guess it, another Canadian record) of 736 km. As with her 48- and 72-hour marks, Brown ran that result at the Six Days in the Dome last year.

Brown says the next race on her schedule is the Badwater 135 ultramarathon in California, but since that isn’t until July, she may take another shot at the 72-hour record with hopes of improving her world record once again.

by Running Magazine

Login to leave a comment

Tunnel Ultra: The mind-bending 200-mile ultra-marathon in the dark

How do you like to spend your weekend off?

Do you put your feet up in front of the TV? Maybe shopping is your way to unwind? Perhaps you're a bit more adventurous and enjoy a stroll in the countryside?

That doesn't quite cut it for some people, who choose to run a 200-mile ultra-marathon in a disused railway tunnel instead.

The Tunnel Ultra is a race like no other. It's easy to find longer events. Some even involve repeating the same loop for days on end. But nowhere else can you take part in a race so twisted that you spend more than two days in darkness doing a one-mile shuttle run 200 times, or so punishing that one runner went temporarily blind - then thanked the race organiser for the privilege.

No outside support is permitted, headphones are banned and runners are not allowed to run side by side. Oh, and there is a strict time limit of 55 hours.

The Tunnel website describes it as "a mind-bending test of extreme endurance and sensory deprivation". It is more health warning than marketing slogan.

"I could be sat on the sofa watching Strictly with the wife and kids. Or do I want to be in a dripping tunnel, tired and miserable, knowing I've got work on Monday?" Guy Bettinson, a 45-year-old programme manager from Cumbria who won the Tunnel in 2020, wonders out loud. "I'd rather waste my weekend putting myself through misery."

"It's so pointless. You're not getting from A to B, which makes it such a massive mental challenge," says Andy Persson, another finisher that year. "If you can push your mind further than you think is possible, it's quite empowering."

Christian Mauduit, a French software engineer who won the 2021 edition, says: "I'm chasing that internal adventure - that meeting with myself. It's like a little kid - they want to see how close they can come to the fire. I'm still that little kid."

Bettinson describes every ultra-marathon start line as a "mid-life crisis anonymous meeting". "We've all got issues," he says. "It's clearly some kind of therapy."

The race takes place in Combe Down Tunnel, a mile south of Bath city centre, and starts at 4pm on a Friday in March. No more than 40 runners make it that far, partly because of a strict - and deliberately opaque - qualification process and largely because the tunnel is not big enough to accommodate many more. "Even the start line is weird," says Mauduit. "You have to stand one behind another in a queue."

Combe Down was restored as a cycle path in 2013 after 47 years under weeds. It is the UK's longest foot tunnel - and the obvious setting for an ultra-marathon if your name is Mark Cockbain.

"I like things that have got an X-factor," says Cockbain, a prolific former ultra-runner who set up the Tunnel in 2019 to add to his brilliant yet brutal portfolio of events as a race organiser. "As soon as I got permission to use the tunnel, it was a no-brainer."

The race is low key in the extreme. A fold-up table outside one end of the tunnel serves as race HQ. There is no shelter or rest area to speak of unless runners have the foresight to bring a camping chair. They must all share a portable toilet which, by the end of the weekend, would not look out of place at a music festival. Refreshments are limited to water and tea, while the most luxurious snacks are Pot Noodles. If you're lucky, they might not be out of date.

"I cut back on delicacies," says Cockbain in the matter-of-fact style for which he has become famous in the ultra-running community. "You can get through any of these races with a bit of water and food. I wanted to make it all about the running."

For Mike Raffan, a 43-year-old IT manager from Aberdeen who finished second in 2021, that's part of the appeal. "It's nice that there isn't any nonsense," he says. "The Tunnel is pure, unadulterated running. You run from one end to the other in a straight line, turn around a traffic cone, come back again, and just keep going. That's it." Persson agrees. "There's no fanfare. If you're looking to be pampered, you've come to the wrong place."

All of which adds up to a notoriously low finish rate. Of the 31 runners who started the inaugural Tunnel, only two completed it, and 13 in total in the three years it has been in existence.

"I don't want there to be no finishers," says Cockbain. "But I do want them to go through hell to get there."

So how exactly do you survive a race that is deliberately designed to break you physically, mentally and emotionally?

In one sense, it is simple. "The only things you have to think about are moving, eating, drinking, sleeping and going to the toilet. That's the limit of your universe," says Max Newton, a fundraising manager from Sheffield who was among the seven finishers in 2020. "All that jazz in real life is nonsense."

"One tactic for me is 100% commitment," says Raffan. Those words carry added weight from someone who ran 182 miles in 42 hours around his back garden three months after open-heart surgery in 2020. During another Cockbain race he continued running in conditions so bleak that his eyeball froze. "I never thought about not finishing the Tunnel. Before the race I told them, 'Do not let me stop unless there's a medical reason for it'."

Mauduit's approach is similar. "I'm asking myself all the complex questions - 'Why am I doing this? Should I go there?' - before the race, in training. During the race I just finish the lap - there's no question."

"You have to be all in. If doubt creeps in, you're gone," says Cockbain. A 50-year-old electronics engineer by trade, he completed 199 marathons and 106 ultras - including some of the toughest in the world, notably five Spartathlons, three Badwaters, a double Badwater and a 300-mile race in the Arctic - before knee problems forced him to stop running in 2011. "I could sit in a corner and hit my head with a spoon for three days if that's what I decided to do."

Bettinson admits the "possibility of failure was a big thing" when he stood on the start line, yet he went on to finish in a scarcely believable 43 hours nine minutes. It remains a Tunnel record by more than six hours and is "up there with some of the all-time greatest ultra achievements", according to Cockbain, not a man given to hyperbole.

Repeatedly running along the same stretch of tarmac throws up a mental challenge rarely found in races of any distance, let alone 200 miles (the total distance is actually 208 because the tunnel is slightly longer than a mile).

"The difficult thing with doing 100 laps is there are 100 chances to stop," says 49-year-old Newton, who also ran a 300-mile lapped ultra last summer. Even if runners quit mid-lap, they must make their way back to the start line. Mauduit agrees that the turnaround point at race HQ is often the most difficult. "Once you're on the course it's easy - everyone can do two miles," he says.

"When you reach the start line again you're facing two choices. One is calling it a day. You will still suffer, your legs will hurt, the pain will follow you for hours, and you have to deal with the fact you gave up. Or you can beat your own personal record in the tunnel and write history. You only have to be motivated for five seconds - just enough time to pick your butt up and get into the tunnel. During the Tunnel I don't do 200 miles; I do two miles 100 times."

A positive mindset is universal - some would argue essential - among those who have completed the race.

"When it's really hurting and I'd rather be in bed, I say to myself, 'I love this tunnel and I can't believe I've got this opportunity'," says Persson, a 57-year-old counsellor from Bristol who once ran 900 miles from Land's End to John O'Groats in 17 days.

"You've got to embrace it - there's no point fighting it or being grumpy. You have to find the bits that make it good," says Newton. Alan Cormack, who finished second in the inaugural Tunnel, adds: "You don't have to worry about weather, mud, navigation. And you don't have to carry a pack."

With no scenery, music or conversation, surely it must be boring? "On these runs you're often very busy," says Mandy Foyster, who staggered over the finish line five minutes inside the time limit in 2021 to become the only female runner to have completed the race. "You don't have time to get bored - you're doing maths in your head and you're so focused on keeping going."

Persson says "my personality likes routine", while Mauduit positively loves it. He once ran 238 miles in 48 hours on a treadmill, but says his favourite events are six-day races. His record is 541 miles.

For Raffan, ultras are his meditation. "People ask what I think about when I'm running. Absolutely nothing. At the best points your mind is empty. When you're in that proper trance state you're not thinking about anything."

Running 200 lengths of the tunnel means running 200 times past a speaker built into the wall at the midway point that resembles a giant eyeball and pumps out classical music on loop all day and night. "There are these little submarine-style windows which glow different colours," says Newton. "It's like super stereo."

Cormack describes it as a screeching violin, which Bettinson claims "adds to the weirdness and psychological torture". Mauduit is more direct: "It drives you nuts."

More psychological torture comes in the form of darkness. There is only dim lighting in the tunnel - which is shared with cyclists and walkers during the day - and even these are switched off between 11pm and 5am.

"Not only are you in the darkness, but you are alone and you have no headphones. It's like a giant meeting with you and your feet," says 47-year-old Mauduit. "All human bodies are conditioned by daylight. In a standard race, when the sun rises you feel great. In the tunnel you have no reference - it's always night."

"It became a very big battle to stay awake," says Foyster, a seasoned ultra-distance athlete whose idea of celebrating her 50th birthday was to cycle between Ben Nevis, Scafell Pike and Snowdon and sleep on the summits of each. "When I got to the end of the tunnel I'd step out in the daylight and just stand there for 10-15 seconds."

Foyster put more thought than most into keeping the so-called sleep monsters at bay - "I had perfume to spray and a Vicks to stick up my nose - anything to stimulate your senses" - but her most valuable tool was a small spray bottle. "When I felt myself falling asleep I sprayed myself in the face with water. That was absolutely fantastic."

Some runners might grab a power nap outside the tunnel - and pray it doesn't rain. Others treat sleep as an inconvenience in a race with an already demanding time limit. A rare few don't even afford themselves the luxury of sitting down.

"If you stop you've got to start again. If you don't stop you don't have to start again. I just kept going," says Bettinson, whose 17 years in the Army have proven an excellent grounding for ultra-running. "I did end up lying down a couple of times, but you're in so much pain by the second night that you can't sleep anyway. And you're just wasting time by not moving."

Raffan pulled out of the 2019 Tunnel after 100 miles to join his wife and daughter at the zoo. It remains his only DNF from more than 50 ultras. When he returned in 2021 he deliberately did not bring a chair. "I ended up sitting on somebody else's, but that was good because whenever they needed it, it forced me to get out."

"I don't trust myself to set an alarm and wake up, so I didn't take the risk," says Mauduit. "The only time I stopped was at the refreshment table or to go to the bathroom."

If sleeping is optional in the Tunnel, hallucinations are all but guaranteed.

"I saw a family of abominable snowmen, a massive slug and I thought I was on the edge of a cliff," says Karl Baxter, who failed to finish the race in 2020 but conquered it with less than an hour to spare the following year.

"Orange blobby monsters kept floating at me out of the darkness," says Foyster, who blames her good friend Baxter for convincing her to sign up for the race. "I wasn't in a tunnel a lot of the time - I was running through Egyptian tombs or over a suspension bridge with deep ravines."

Mauduit recalls: "On the last day it got insanely bad. I was seeing stairs; I was walking on a glass floor. I couldn't escape from it. The hallucinations were an order of magnitude stronger than anything I've ever had before. It was mind-blowing."

Cockbain has seen it countless times. "It's just total carnage," he says. "People are losing their marbles. If they stop for a rest, they can't remember which way they're going."

The effects lasted beyond the race for Persson. "I saw ticker tape, carvings in the wall, and I was convinced there was a glass conservatory with flowers. My wife and daughter picked me up and I was still hallucinating by the time I got home. I've never had that level of it before - it was so extreme."

Training for the race varies wildly between competitors. Bettinson's longest run in the build-up to his victory was a mere 12 miles; Foyster "did a lot of fast walking"; Cormack, who was scared of the dark as a child, favoured night-time runs; and Baxter attempted to simulate the boredom with lengthy treadmill sessions or by running up and down a one-mile stretch of road. He managed 48 of them one day.

Eating and drinking strategies are equally individual, but, given that runners burn about 20,000 calories during the course of the race, hunger triumphs over health. Dentists and doctors, look away now.

Pizzas, chocolate, cake and flat cola fuelled Foyster for nigh on 55 hours. Baxter polished off tube after tube of salt and vinegar crisps, all eaten on the move to save time. Jam sandwiches, flapjacks and Pot Noodles - "they really hit the spot" - kept Newton going. Raffan tucked into supermarket meal deals and butteries - a "really dense, stodgy" Scottish pastry - but describes cold custard as his "secret weapon". Persson's menu of quiche, sausage rolls and overnight oats seems positively gourmet by comparison.

Bettinson is powered by a concoction of Lucozade, pineapple juice and beetroot juice. He also liquifies food and puts it in baby pouches "so it's easy to get down". Because it is impossible to replace the energy you are burning, his plan is "fuel early and then cling on".

As the saying goes, what goes in must come out, although most runners visibly wince when they remember a toilet situation that Newton laughingly describes as "a disgrace".

Bettinson says: "The first time I did the Tunnel it was a little chemical kiddy loo that you'd take camping. It was in a half-collapsed tent with a broken zip. Mark deliberately put it in a puddle, so you had to get your feet wet just to get inside it, and after the first 50 miles it was like a festival loo - you had to hover over the top."

Even if runners can cope with the boredom, darkness and sleep deprivation, pounding tarmac for longer than some weekend breaks last takes an immense physical toll.

"Of course your legs will hurt - you're running 200 miles. What did you think was going to happen?" says Mauduit, a man whose CV also features winning a Deca Ironman - a triathlon consisting of a 23-mile swim, 1,118-mile bike ride and a 262-mile run.

"Everything after 20 miles involves pain," says Bettinson, who admits that theory was tested when his hips were in "absolute agony" 100 miles in. "Anyone can get round it - you just have to want to."

Newton's approach veers towards the spiritual. "In a weird way, if you run through excruciating pain it doesn't hurt any more," he says, with the caveat that this approach doesn't always translate to his partner Anna. "She's worried I'm going to die. She has seen me in a bad state - sometimes it has been a bit messy."

Cockbain has this advice: "The feeling of wanting to give up doesn't last - if you put something in its place."

Runners know better than to expect sympathy from Cockbain, whose stable of events also includes an unsupported 300-mile run from Hull to the south coast as well as a race where pairs of runners in boiler suits are chained together and have 24 hours to cover as much ground as possible. You can sense the disappointment in his voice when he recalls how The Hill, which involved climbing up and down a hill in the Peak District 55 times - equating to 160 miles - in 48 hours had to be scrapped after the pub which doubled as the checkpoint closed down.

Perhaps Bettinson sums up Cockbain best: "Mark has a motivational speech at the start of his races: 'If you're going too slow, speed up.'"

Baxter, a 51-year-old from Norfolk who spent 12 years in the Army and now drives lorries for a living, turned an ankle during his second attempt at the Tunnel. "It came up like an egg. I sat down for 20 minutes and I was going to quit. Mark said, 'A twisted ankle never killed anyone' and told me to carry on. It taught me a lot. Once I got to 150 miles I knew I was going to finish."

Individual motivation comes in different forms, but a common thread among finishers is the time, energy and money they have invested in a race that often few people outside their close circle of family and friends know about. Nobody gets into ultra-running for the glory, least of all those taking part in Cockbain's events.

"My wife is handling all the family by herself, working and having no fun," says Mauduit, who rode his motorbike from Paris to take part in the Tunnel. "I'm having this five-day vacation so I should do something good with that."

Bettinson flips the question on its head. "My why for being there is I chose to be there. I've paid the money, I've done the training, I've turned up. Why on earth wouldn't I finish?"

Foyster, meanwhile, does it for the sheep. Having grown particularly fond of the animals during endurance adventures such as running the width of the UK or cycling the length of it, she now uses ultra-marathons to help raise funds for a sheep sanctuary in Lincolnshire.

"When I was struggling in the Tunnel, my friend sent me videos of the sheep. I'm thinking of them at the tough times," she says. "Some people ask me if I have a coach. I say my coach is a sheep called Bella."

Foyster, who works at an animal sanctuary near Norwich, has run the London Marathon dressed as a sheep and even had a fancy dress costume lined up for the Tunnel, but never got chance to wear it because she was in such bad shape later in the race. What was the outfit? "A sheep dressed up as Darth Vader."

The gruelling nature of Cockbain's races and the derisory finish rate creates a special sort of camaraderie among runners, evident from the dark humour on the start line to the support they offer each other as they push beyond their limits.

"Everyone feels like they're in it together. It doesn't feel competitive," says Newton. Cormack, who runs a cleaning company in Aberdeen, adds: "Nobody cares if you're first or you're 20th." Bettinson says: "Mark's events feel less like a race and more about the entrants against the event as a collective. You're only ever racing against yourself."

Foyster, 56, says she goes into any event with a "1,000% determination to finish it", but her unwavering drive in the Tunnel took her to a place she had never been before.

"After 100 miles my body started to break down," she recalls. "By 150 miles I had adopted my walk-shuffle approach, and in the last 10 miles I completely lost my mind. I kind of went over to the other side.

"At mile 192 I became completely disorientated and started going the wrong way. I thought I was wandering along a quiet country lane. I didn't know who I was or what I was or what I was doing."

In a rare moment of weakness/graciousness (delete depending on the coldness of your heart), Cockbain allowed Foyster's friend to accompany her as she staggered to beat the time limit. He even turned cheerleader on Foyster's final lap.

"At mile 198 my vision went," says Foyster. "I couldn't see anything. I crashed into the wall a few times. I had a broken tooth. I felt like I just needed to collapse on the floor. It was the first time that I'd felt worried about myself physically.

"Mark appeared behind us on a bicycle shouting 'you've got to go faster'. I was running blind - I was running into a white mist. I felt like I was sprinting flat out. I kept running until Karen the timing lady caught me in her arms." Foyster had finished in 54:55, not even time for another lap.

Because she was "in a complete and utter state", Foyster says she did not get to savour the finish line moment. "That's the only bit I regret."

She didn't miss much. "There are only a handful of people there. You get a bit of a clap, Mark shakes your hand and gives you your medal," says Persson. "It's not like you've got people patting you on the head," says 55-year-old Cormack, who then slept on the back seat of his car because he was too tired to put his tent up.

"Mark said a few words - I was so knackered I can't remember what - and I just picked my box up and went to the train station," says Bettinson. "It was a busy weekend and there were a lot of people ready for a day out. There was me, absolutely stinking, wheeling this box and eating bits of scabby old sandwich."

Foyster was so spent that she had to be carried to her hotel room. Baxter, who did some of the carrying, says: "That was just as hard as the last few miles."

"If you finish one of Mark's races you get respect from him. That means a lot," says Newton. Bettinson agrees. "Most of my medals I chuck in the bin. If it's one I'm bothered about I keep it in a drawer. I've kept the Tunnel one."

Cockbain's goal is simple: "All I want is that someone walks away remembering it for the rest of their life. Ultimately we're going to live and die. How are you going to fill up the middle of that? Achievements last forever."

"Races aren't pretty - that is real life," says Foyster. "The Tunnel is the hardest I've pushed myself. I've never needed help like that, so my overwhelming feeling was I was so grateful."

Mauduit, who describes the Tunnel as an "awesome race", adds: "I thank Mark for putting it together. I discovered something new. It was a blast. It all makes sense because it doesn't make sense. It's worth every penny."

Baxter remembers clearly his feelings in the week after the Tunnel. "I was buzzing. I felt on top of the world. I felt invincible." Newton recalls: "When I was telling people about the Tunnel I was talking with a smile on my face."

But what on earth is next for those who have completed one of the most challenging ultra-marathons invented?

Baxter tells a story typical of a certain breed of ultra-runners. "My girlfriend said, 'Is that it?' I said, 'No way. I want to go further.' Plus, no-one has done it twice." He may have company. "I'll be back one day," says Mauduit. "I'm thinking about it."

Cockbain recognises the signs from his own running days. "It's a drug. It's an addiction. It's a never-ending 'what's next?' You never get satisfied."

Even Bettinson, the record holder, says: "My holy grail is I want to finish an event where I know I've given absolutely everything - even if I don't finish. It could be one mile or it could be a thousand miles.

"I'm still chasing that unicorn."

by BBC

Login to leave a comment

Take a Sneak Peek into 'Born to Run 2'

Thirteen years after the publication of Christopher McDougall's popular book, Born to Run, the author teams up with renowned running coach Eric Orton for Born to Run 2: The Ultimate Training Guide, a fully illustrated, practical guide to running for everyone from amateurs to seasoned runners, about how to eat, race, and train like the world's best. Born to Run 2 will be available on December 6, 2022, but you can read this excerpt from the book.

Chapter 8: Form - The Art of Easy

Eric promised he could teach running form in ten minutes. If I had to estimate, I'd guess he was miscalculating by a factor of at least 7,000 percent, so I subjected his proposition to lab testing and gave it a try myself:

I hit Pause and checked my watch. Then I tried it again. Each time, I found Eric's estimate to be wildly exaggerated. It wasn't even close to ten minutes. More like five.

One song. One wall. Three hundred seconds. If someone had only shared this secret with Karma Park, it could have saved her a world of misery.

Karma was such a disaster, the Navy honestly couldn't tell if she was a terrible runner or a terrific actor. How she even made it into boot camp was a mystery.

The strange thing was, running was her only weakness. Chuck her out of a boat at sea? No problem. Pull-ups, push-ups, crunches? Piece of cake. Karma was a competitive swimmer and varsity wrestler growing up, so two-hour workouts were in her blood. But ask her to run a mile and a half? In under thirteen minutes? Not a chance. Over and over she tried, and every time she ended up walking, grabbing her ribs from stitches and wincing from aches in her legs.

"I'm pretty sure the recruiter fudged the numbers on my Physical Readiness Test so she could get me in," Karma believes. "I finished the run and thought, Oh crap, I'm a minute too slow, and she's like, 'No, no, you're good.' "

When Karma got to basic training, she gritted her teeth and did her best. The Navy was her ticket to a dream life, so there was no way she was giving up. Karma was twenty-five at the time, with a wife in law school and hopes of becoming a surgeon. The surest path toward financing their future was a career in the military. Besides, she had a debt to pay back. Karma came to America from South Korea at age eleven, and while, yeah, maybe Alabama wasn't the most welcoming place for a foreign kid with budding gender issues, Karma was still deeply grateful for the life her family was able to create there.

"I really wanted to serve this country," she says. "But in boot camp I was in and out of sick bay all the time." Karma chanted the drill instructors' mottoes to herself-Pain is only skin deep! Heel to toe! Heel to toe!-but the harder she pushed, the more she broke down. "At first maybe they were checking that I wasn't dogging it," Karma recalls. "I can see how I would be suspected because I feel that other recruits faked it to get out of running, but I was in so much pain, they knew something else was going on."

Finally, Navy doctors diagnosed Karma with chronic hip displacement. She was ordered to report to the long-term sick bay, where she'd be stuck for as long as it took-a month, six months, a year-for her to either heal or quit. Those were her options: get better, get faster or get out.

Karma was crushed, but privately vindicated: ever since she was young and her mom would sign the whole family up for local 5Ks as a way of assimilating into their new home, Karma knew she couldn't run. "My dad and I would walk at the back of the pack, and I thought, This is the most ridiculous thing ever. We have cars and bikes, why are we running? I was really fit in all the other aspects of PE, but with running, I tried and tried and never got any better."

Back in civilian life, Karma struggled. She put her own education on hold and began managing a Subway so her wife could finish law school. She began putting on weight, but when she tried to exercise, her old leg injuries flared up and she finally discovered the real cause of her pain was rheumatoid arthritis. The medication made her lethargic and bloated, and her body ached so badly she needed a cane to walk.

Karma was in a bad spiral that nothing could stop. Except her wife's lover.

"My wife had an affair with a guy who was really fit," Karma says. "When I confronted her, she told me I was fat. That hit me really hard." So hard that after she and her wife separated, Karma decided to punish herself with the thing she detested most. "I decided to drown my emotional pain by subjecting myself to physical pain," she says. "When I left the Navy I swore off running-I hate it hate it hate it, never running again. This time, I decided to run myself ragged into an early grave. I hated myself and hated running, so this is what I'll do."

For once, Karma's injuries came to the rescue. Her legs seized up before her heart, and while she was searching for a new way to beat on herself, she had the enormous good luck to meet Sheridan. With that amazing woman by her side, parts of Karma that she hadn't even realized were hurting began to heal. For the first time, she had the confidence and support to face her gender identity and begin transitioning to the self that had always been buried.

She also resolved, once again, to get back into shape.

If you're keeping score at home, by now Karma has struck out three times as a runner. Over the years, I've heard a lot of stories like this from busted ex-runners-and lived one myself-but this is the first instance where I thought, okay, maybe it's time for the mercy rule to kick in and let it go for good. But against those odds, Karma stepped up again. When Sheridan gave birth to their first son, Karma set her jaw and decided their baby wasn't going to grow up with a parent hobbled with a cane or gone before their time.

"That's how I began my journey into learning how to run properly," she says.

This go-round, Karma attacked the problem from a different angle: What if her brain was the problem and not her body? Karma is a math whiz and comes from a medical family, so she was a little annoyed at herself for not realizing sooner that if your equation keeps giving you the wrong result, adding the same numbers isn't going to help. Rather than running harder, she thought, maybe there was a way she could run smarter.

Her eureka! moment occurred soon after, when she noticed that her legs hurt more on downhills than ups. That's when it hit her: What if she treated the entire planet like a hill? Get up on her forefoot, in other words, instead of heel-toe, heel-toeing it like she'd always been told.

"When I mentioned this to a friend, she immediately said, 'Haven't you read Born to Run? That's what it's all about.'"

Karma picked up a copy, and there, on page 181, she found the role model who would change her life. Not Ann Trason, the courageous science teacher who nearly outran a team of Raramuri runners in the Leadville Trail 100. Not Scott Jurek, the gracious and unbreakable hero who rose from a rough Minnesota childhood to become the greatest ultrarunner of all time. Karma didn't even see herself in Jenn Shelton, that patron saint of human fireballs, or Caballo Blanco, the lovelorn loner who used running to heal a broken heart.

Nope. When Karma looked into the mirror, grinning back at her was Barefoot Ted.

I'm not happy about this now, but when Caballo Blanco and I first met Ted McDonald, we were ready to Rock-Paper-Scissors over who was going to clunk him on the head and chuck him into the canyon. Ted likes to say "My life is a controlled explosion," which only confirmed my conviction that he has no idea what "control" means.

I was slow to see what Jenn and Billy Bonehead and Manuel Luna liked about Ted. It took a few clashes before I finally got it, including a toe-to-toe shouting match in the middle of Death Valley, where I threatened to leave Ted by the side of the road to die while he was yelling in my face, "I don't care how big you are! I'll fight you!"-at the very moment, by the way, when we were supposed to be crewing for Luis Escobar in the Badwater Ultramarathon.

But I couldn't miss the fact that lots of other people really enjoy him. Ted is a lot on a slow day, but he's also a huge-hearted friend and his own kind of genius. When I sent word to Ted that a group of my Amish ultrarunning buddies were traveling through Seattle en route to a Ragnar Relay, he immediately threw open the doors of his Luna Sandal shop and made them at home in an improvised bunkhouse. Nearly every year, Ted travels back down to the Copper Canyons and hands a wad of cash to Manuel Luna, the Raramuri artisan who taught him how to make huaraches. Not because they're partners; because they're friends.

Still, it was gratifying to see that Luis had as much steam shooting out of his ears as I did after we invited Ted to join us in Colton for our photo shoot. For forty-eight hours we couldn't get a yes or no out of the guy, which would have been fine if he'd just stayed silent as well. Instead, Luis and I kept getting cryptic little teaser texts, like digital art smiley faces that dissolved from our phones a few seconds after appearing. It felt less like waiting for a friend to show up (or not) and more like being stalked by the Zodiac Killer.

Then lo and behold, an Amtrak train pulls into San Bernardino station and out pops Barefoot Ted, a big Santa Claus backpack full of sandal-making supplies over his shoulder. He'd spent six hours getting there, and immediately began hand-crafting a gorgeous pair of custom sandals for each of our volunteer models. While his hands were busy, so was his mouth: Ted cut loose with a thirty-minute spoken-word performance that left us all slack-jawed in astonishment as he prattled on, fluently and kind of brilliantly, about everything that had been rattling around inside his skull while he was captive on the train. ("Turning everything you see into food is a superpower. Do you have it?" is the only line I remember.) Soon after finishing a dozen sandals he was gone, grabbing a lift back to Santa Barbara that same night because, unbeknown to us, he'd had a pressing commitment there all along. What a guy.

As a runner, Ted was a true revolutionary. He was so far ahead of the pack when it came to minimalism, the rest of the country took years to catch up. Not that he didn't make a compelling argument from the start. It's just that in typical Ted fashion, the story took a direction only a man who calls himself The Monkey would follow.

If you recall, Ted only began running in the first place because he dreamed of becoming America's Anachronistic Ironman. Which meant, for reasons known only to Ted, he wanted to spend his fortieth birthday completing a full triathlon (2.4-mile ocean swim, 112-mile bike ride and 26.2-mile run) but only using gear from the 1890s. If Ted has one quality greater than his raw athleticism it's his absolutely bulletproof self-confidence, so when he found he could handle the swimming and cycling but not the running, the problem couldn't be his body: it had to be the running.

Close: it was actually the running shoes. The first time Ted ran barefoot, his planetary axis shifted. "I was totally amazed at how enjoyable it was," Ted says. "The shoes would cause so much pain, and as soon as I took them off, it was like my feet were fish jumping back into water after being held captive."

On a barefooter's blog, he found the Three Great Truths:

Change the way you run That was the opposite of everything Ted had ever been told about running, but everything Ted had ever been told about running wasn't working. Besides, it immediately made sense. No decent basketball player just heaves the ball in the air and hopes for the best. No serious tennis player slashes their racket around like a club. Ted had spent a few years as a teacher in Japan, and he knew that sushi chefs and martial artists spend years perfecting the basic steps of their craft. In the world of movement, form and technique reign supreme.

Ted didn't know any barefoot runners in person, only online, so he set off on this quest for reinvention on his own. He found himself in the same predicament as a Czech soldier he'd heard about who, during the Second World War, spent his long nights on guard duty dreaming of Olympic glory. Rather than stand and shiver, the soldier began running in place, lifting his knees high to clear the snow and, to avoid being heard, landing as silently as possible in his heavy boots.

Back home after the war, the soldier replaced slippery snow with wet laundry: he washed his clothes by running on top of them in a bathtub full of soap and water. (Get a load of that, Mr. 100 Up: one sloppy stride in a sudsy tub and you're not starting over, you're heading to the emergency room.)

Those weird home experiments paid off spectacularly. Coached only by his own ingenuity, Emil Zatopek pulled off the most stunning track performance in Olympic history: at the 1952 Games, he won gold in all three distance events, including the first marathon he ever attempted.

Despite how fast he ran, Emil took a ton of crap about how awful he looked. Upstairs, Zatopek was a horror. He'd get this grimace on his face, one sportswriter said, "as if he'd just been stabbed through the heart." Zatopek's head lolled around and his hands clawed his own chest like he was birthing an alien baby through his rib cage. But what sportswriters missed was that below the waist, Zatopek was a machine: rhythmic, precise, impeccable.

Ted never did get around to his Anachronistic Ironman-not yet, at least-but otherwise, he was unstoppable. Once he realized that running was a skill to be mastered and not a punishment to be endured, he became a Monkey on a mission.

Before long, he'd ripped out a marathon quick enough to qualify for Boston, and then ran Boston quick enough to qualify for the next one, and from there it was onward and literally upward, as he shifted from long roads to high-mountain ultramarathons.

But what Karma envied most wasn't Ted's remarkable twenty-five-hour finish at the Leadville Trail 100, or his out-of-left-field world record for skateboarding (242 miles in twenty-four hours). She didn't care if she ever ran as fast as Ted. She just wanted to be as healthy. She wanted to follow his footsteps from Hurt Ted to Happy Ted.

"I made a conscious decision to fully embrace forefoot running," Karma says.

Maybe embrace isn't the right word. Since May 3, 2014, Karma hasn't missed a single day of running. Every evening, no matter what kind of storm is blowing through Birmingham, Alabama, no matter if she's fighting a cold or dealing with craziness at the medical office she manages, Karma pulls on her sandals and heads out the door.

Her eight-year-and-counting streak began in true Barefoot Ted fashion: bizarrely. Less than a year after changing her form, the woman who swore she'd never run again was bringing home her first marathon medal. Gone was the cane, forgotten was the specter of crippling arthritis. By changing the way she moved, Karma discovered she could change the way she felt. She soon ramped up from a marathon to a 50K, and that's when things took off. The day after that first ultramarathon, Karma decided to test her soreness by jogging an easy two miles. She was surprised to find her legs actually felt better after that run, so she went out again the next day and the next and thus a streak was born.

To maintain her daily running streak, Karma logs at least one mile a day, but that's just her baseline. During her first year of streaking she also tackled three ultramarathons, and then began creating streaks within her streak: she ran five miles a day for a full year, seven miles a day for ten months, and three miles a day for 1,300 days. Despite all these clicks on her odometer, Karma still felt she needed to borrow one more hack from Barefoot Ted: as a reminder to remain smooth and light, she always runs in a pair of his Lunas.

Karma had never actually met Ted in person until the day he hopped off the train in San Bernardino and blew into our photo shoot like a grinning bald tornado. Ted is usually quick on his feet, but when he came eye to eye with Karma, it took him a few beats to get his bearings.

The person who'd reached out to Ted years ago had never felt at home in her body and was facing two frightening transformations. The Karma in front of Ted today had made it through to the other end. In the past, Karma had looked to Ted for hope and guidance. Now, she deserved something very different. Ted understood, and delivered.

"If you have any questions, ask Karma," Ted said, as he addressed the circle of very experienced and accomplished ultrarunners hanging on his every word about the art of minimalist running. "She knows as much as I do."

This is an excerpt from Born to Run 2: The Ultimate Training Guide by Christopher McDougall and Eric Orton, available on December 6, 2022 by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright 2022 by Christopher McDougall and Eric Orton.

by Trail Runner Magazine

Login to leave a comment

You’ve Heard of Running for Beer. But What About Running as Beer?

New Zealand ultrarunner Glenn Sutton finished the Dunedin Marathon on September 11 in a huge beer can costume that he crafted himself.

You might find this hard to believe, but only one of the 165 runners that completed the Dunedin Marathon in Dunedin, Otago, New Zealand on September 11 was wearing a human-sized beer can costume.

Glenn Sutton, a 48-year-old ultra runner from Dunedin, and local brewery Emerson’s, the marathon’s sponsor, came up with the idea before the COVID-19 pandemic canceled the 2020 edition of the marathon.

“I thought it would be something quirky to do. I hadn’t seen it done before,” Sutton told Runner’s World. “I’ve seen cans where people’s arms and heads poke out, but not a full-size can.”

After two long years of waiting, the Dunedin Marathon was finally scheduled for fall 2022, so Sutton got to work. A joiner by trade, he put his ornate woodworking skills into constructing a beer can costume that would cover his entire body from his head to just above his feet. His friend Bruce Adams made the signage that covered the wooden frame, which depicted Emerson’s Super Quench, a low-carb Pacific pilsner that launched earlier this year.

While in the can, Sutton couldn’t use his arms much and could only manage a shuffle rather than a full stride. It was hot, “like running in a glass house,” Sutton said. He could only see through a plastic cut-out at eye level, which blurred his already obstructed vision.

On race day, Adams ran about five meters ahead of him to make sure Sutton was on the right path. Sutton, who’s run ultra races like the days-long Badwater 135 before, wasn’t worried about taking his time to finish the race. He typically runs under three hours for marathons, but knew this particular attempt would take longer—especially if there were setbacks along the way.

Unfortunately, a major setback did occur. With 5K left, an unexpected gust caused Sutton to clip his foot on the inside of the can. He tried to catch himself, but fell on the footpath.

At that point, he was “like a turtle on its back,” rolling around while locked into harnesses around his shoulders and waist. Though the can took some damage, Sutton survived the fall unscathed. He unstrapped, got out, re-strapped in, and trudged forward for the final three miles.

As he neared the end, Sutton heard his name over the loudspeakers. A crowd clapped him through the finish line, which he crossed in a time of 6:12:37.

“It was quite cool,” said Sutton. “It drew a bit of attention, and that’s what it was all about.”

Sutton’s next challenge? Big Dog’s Backyard Ultra Satellite Team Championships, where he has to run a 4.167-mile loop at the top of the hour, every hour, for as long as possible. Nations choose their 15 best ultra runners to compete against the rest of the world, and the team that logs the most yards wins. If Sutton outlasts his 14 New Zealand teammates, he individually qualifies for the Backyard Ultra world championships in October 2023.

“I enjoy challenging myself to go these distances,” said Sutton. “I don’t mind grinding it out—and I want a bit of pain.”

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

Here’s How the U.S.’s 5,000-Meter World Finalists Handle Excessive Heat on Race Day

Racing in hot weather can be daunting. Utilize these pro tips from Elise Cranny, Karissa Schweizer, and Emily Infeld to better prepare yourself for the next scorcher.

If you’ve ever raced in the summer, then you know how difficult it is to be underneath the beating sun for too long. Heat stroke, sunburn, and dehydration are legitimate dangers from overexposure. But maybe you signed up for a race that starts in the middle of a summer day. Maybe you’re running a destination marathon in a hotter climate. Perhaps you’re even attempting an ultramarathon, like Badwater 135, which takes place in Death Valley. You want to race, but you also want to be safe.

Professional runners sympathize. On July 20 at the World Athletics Championships in Eugene, Oregon, the women’s 5,000 meters took to the track for their preliminary races in searing 90-degree heat.

Yet despite the scalding temperatures, Elise Cranny, Karissa Schweizer, and Emily Infeld of the U.S. all qualified for the 5,000-meter final without any problems from the temperature. Schweizer and Infeld even ran season bests. Here are their tips for handling the heat so next time you’re faced with a race on hot day, you can be prepared.

Gradually adapt to hotter temperatures

Before the prelim, Infeld hadn’t run much in hot weather. She trains part-time in Flagstaff, Arizona, whose average summer high hover around 80 degrees, and has spent the last few months in Eugene, which hadn’t experienced 90-degree days yet.

“We were trying as best we could to go at the hottest part of the day, which is around 4 to 6, to do workouts,” said Infeld. “Some days that was 80 degrees, some days that was 60. So, I was trying to do sauna, and do things that I could to prepare in case it was hot.”

Infeld owns a portable sauna tent that goes up to 140 degrees. She would go for a run, and if it wasn’t hot enough for her body to learn to adapt, she’d hydrate well and sit in the sauna for 20 minutes to simulate heat training. A review published in Frontiers looked at numerous studies that confirmed that passive heat acclimation strategies, such as sauna, have a measurable effect on athletic performance and heat tolerance. If you don’t have access to a sauna, a study from Temperature recommends overdressing to simulate hotter temperatures, though admits this method isn’t as effective.

Infeld’s preparations paid off with a season best time of 15:00.98 and a time qualifier for the 5,000-meter final.

Stay as cool as possible before racing

Schweizer already had one race under her belt before the 5,000-meter prelims —the championship 10,000 when she placed ninth in a personal best of 30:18.05. Because the weather was temperate for the 10,000, Schweizer found the heat during the 5,000 jarring.

Not only does Schweizer train to adapt to the heat—such as working out in the Salt Lake City, Utah sun during altitude camp with the Bowerman Track Club or using a sauna like Infeld—but she also takes precautions before race to stay cool.

She spends much of her pre-race time in the shade, wears an ice vest to warm up, and even stuffs ice in her uniform on the starting line: “It was to the point where I had chills, so I was pretty cold going into the race.”

While utilizing shade and ice may sound like too simple of a solution, it’s actually very effective. The same Temperature study previously mentioned reveals that pre-cooling your body optimizes endurance performance and mitigates the effects of heat strain during extreme temperatures. Some techniques mentioned include ice baths, ice vests, cold towels, and drinking very cold drinks or frozen beverages (called “ice-slurries” in the text) before the race. The study recommends trying out a few techniques to see what works best for you on race day.

Wear sunglasses to prevent extra strain

Cranny credits her races last year at the Olympic Trials and Olympics as practice for racing in the heat, and also has similar pre-race cooling procedures as her teammate, Schweizer. But Cranny also found that wearing sunglasses during races makes a huge difference.

According to Cranny, many of the Bowerman Track Club athletes wear sunglasses in practice. But until the USATF Championships in June, she had never worn them in a race before. Shalane Flanagan, who coaches the club alongside Jerry Schumacher, highly recommended it, telling Cranny that it prevents squinting in direct sunlight, which relaxes the face. By relaxing her face, Cranny felt she prevented other parts of her body from tensing up, such as her shoulders.