Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #Alberto salazar

Today's Running News

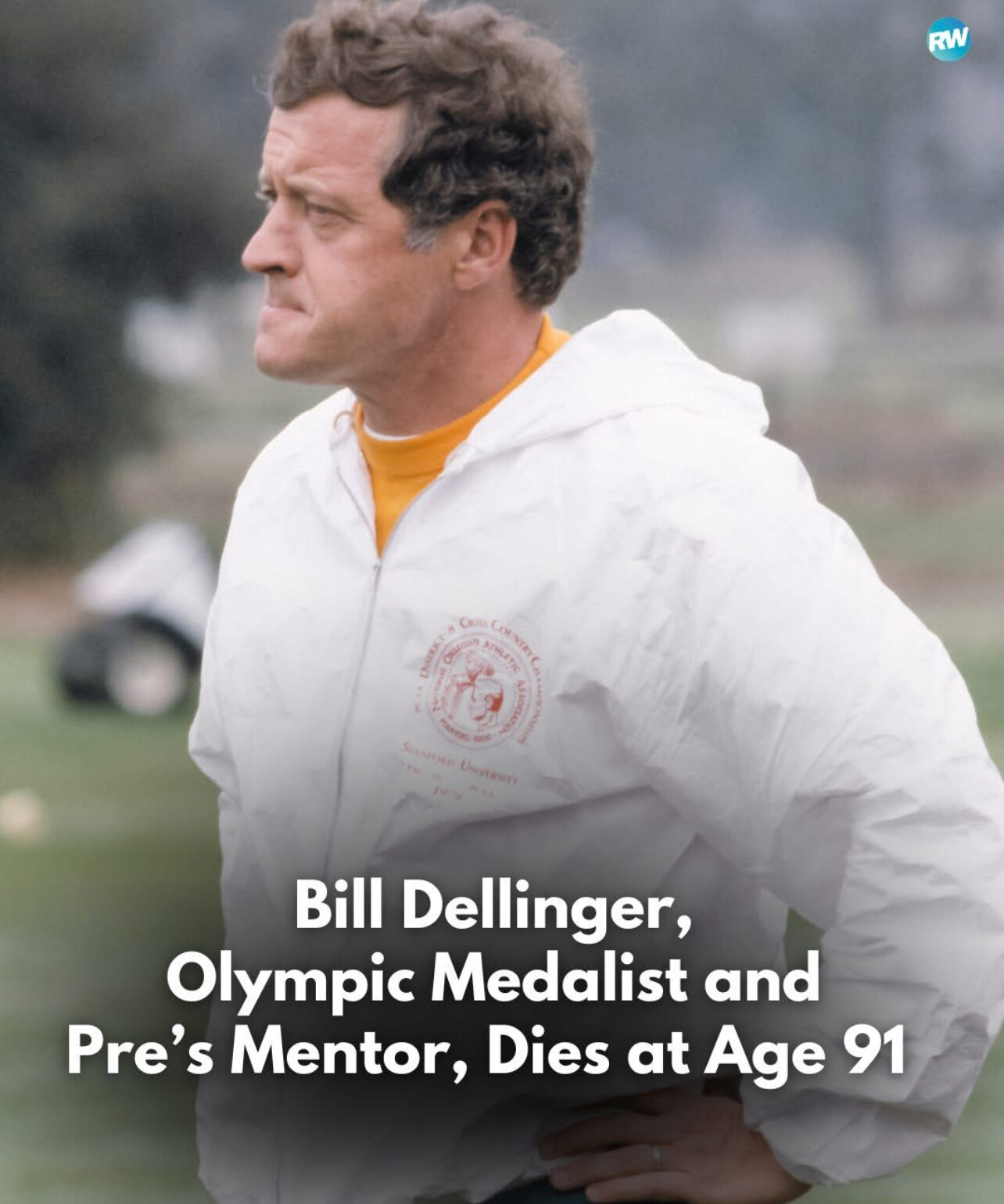

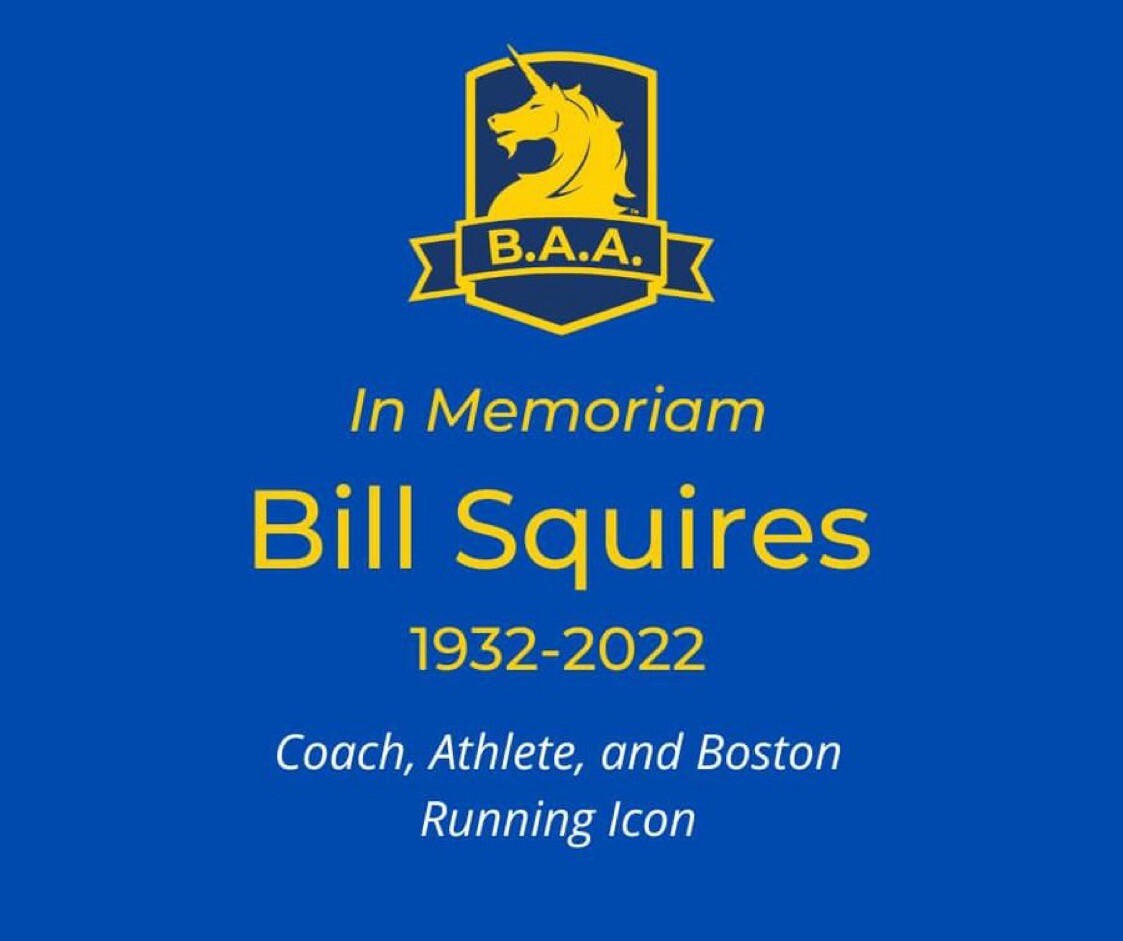

Bill Dellinger, Olympic Medalist and Legendary Coach, Passes Away at 91

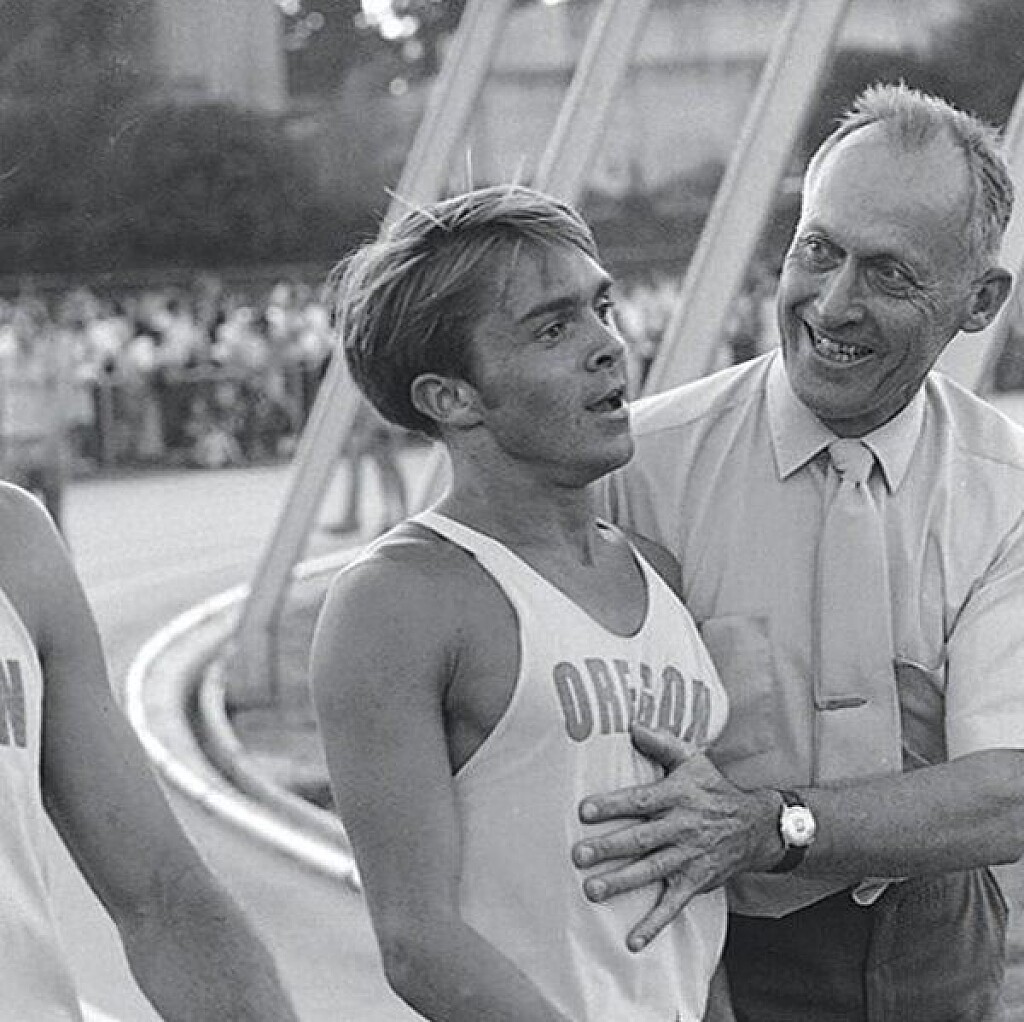

The world of distance running is mourning the loss of one of its greats. Bill Dellinger, a three-time Olympian, Olympic bronze medalist, and one of the most influential coaches in U.S. track history, has passed away at the age of 91 on June 26.

Dellinger’s name is etched into the legacy of American distance running, both for his competitive fire and his ability to mentor champions. A fierce competitor on the track and a quiet architect of greatness on the sidelines, Dellinger leaves behind a legacy that stretches across generations.

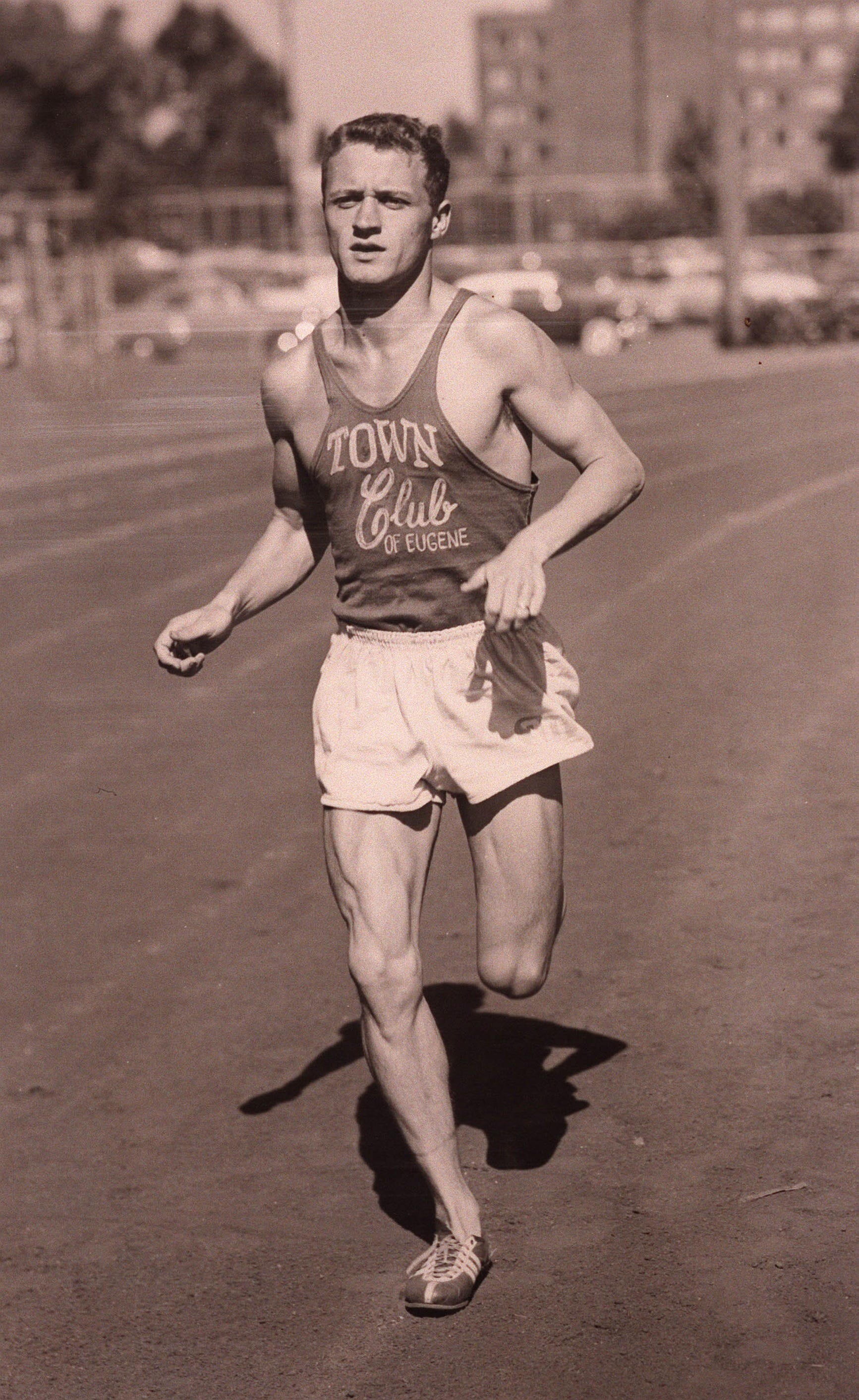

Born on March 23, 1934, in Grants Pass, Oregon, Dellinger rose to national prominence while competing for the University of Oregon under coach Bill Bowerman. He represented the United States in three Olympic Games—Melbourne 1956, Rome 1960, and Tokyo 1964—earning a bronze medal in the 5000 meters in his final Olympic appearance.

But Dellinger’s second act may have been even more impactful.

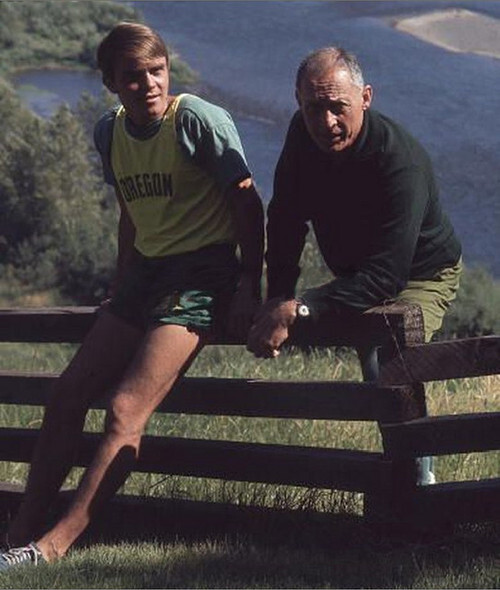

In 1973, he succeeded Bowerman as head coach at Oregon and immediately found himself guiding the nation’s most electric young runner—Steve Prefontaine. Their relationship transcended typical coach-athlete dynamics. Dellinger was more than a tactician; he was a stabilizing force for a fiercely independent and intense young star.

“Dellinger wasn’t just a coach. He was an architect of belief,” Prefontaine once said. “He knew when to push and when to trust.”

Dellinger coached at Oregon until 1998, mentoring athletes like Alberto Salazar, Matt Centrowitz Sr., Rudy Chapa, and many others who carried the Oregon tradition to global stages. He helped solidify Oregon’s reputation as the mecca of American distance running.

He was known for blending scientific training methods with an intuitive understanding of athlete development. His workouts were tough, his expectations high, but his support unwavering.

A Lifetime of Influence

Dellinger’s contributions to the sport extended well beyond the track. He co-authored training guides, helped shape early Nike culture, and lent his name to the prestigious Dellinger Invitational, one of the top collegiate cross-country meets in the country.

“Bill’s influence on distance running—first as a world-class athlete and then as a masterful coach—was profound,” said Bob Anderson, lifelong runner and founder of Runner’s World and My Best Runs.

“I hadn’t seen Bill in years, but his presence still echoes in the sport today. He inspired a generation and helped build the foundation of what American distance running has become. He may be gone, but he’ll never be forgotten.”

A Final Lap

Dellinger’s passing marks the end of an era, but his life’s work will continue on every time an Oregon singlet toes the line, every time a young coach references his methods, and every time a runner believes they can dig a little deeper.

He didn’t just coach champions—he helped shape the soul of American distance running.

Rest in peace, Coach Dellinger.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

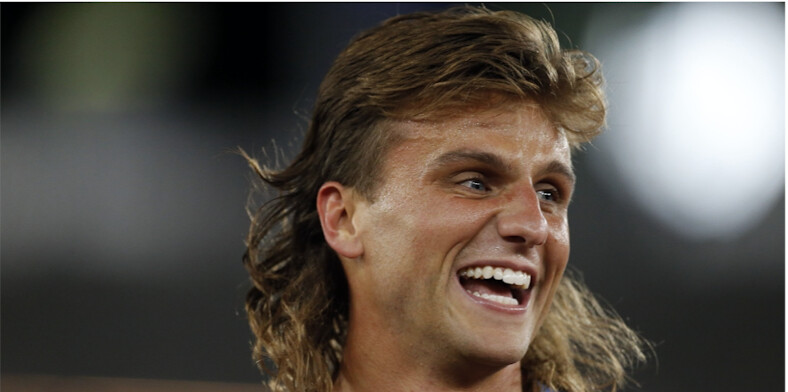

Clayton Murphy Shocks Fans with Early Retirement After Stellar Olympic Career

Olympic bronze medalist Clayton Murphy stunned the track and field world by announcing his retirement at just 30 years old on May 7, 2025. Known for his gritty racing style and breakthrough performances, Murphy exits the sport with a legacy that inspired a generation of American middle-distance runners.

A Decade at the Top

Murphy’s journey began in New Madison, Ohio, and quickly accelerated during his collegiate years at the University of Akron, where he captured the 2016 NCAA 1500m title. Just months later, he stunned the world by winning bronze in the 800 meters at the Rio Olympics, clocking a personal best of 1:42.93—the fifth-fastest time ever by an American. It marked the first U.S. medal in the Olympic 800m since 1992.

Over the next decade, Murphy consistently represented the United States on the world stage, including appearances at the Tokyo 2021 Olympics and multiple World Championships. His smooth stride, tactical awareness, and fierce closing speed earned him fans worldwide.

Why Retire Now?

In an emotional Instagram post, Murphy reflected on his decision:

“I poured everything I had into this sport, and I’m walking away with pride, gratitude, and a heart full of memories. A decade on the global stage is more than most pros will ever get to experience, and I’m so grateful for what every year has taught me.”

While Murphy did not point to a single reason for stepping away, his message hinted at a desire for growth and new opportunities beyond the oval. He thanked his longtime coaches Lee LaBadie and Alberto Salazar, as well as his wife and fellow Olympian Ariana Washington, for their unwavering support.

What’s Next?

Though he’s stepping off the track, Murphy made it clear he won’t be far from the sport:

“I might be done running 50s around the track, but I know I’ll always be a part of this sport one way or another. Can’t wait to share with you what’s next!”

A Lasting Legacy

Fans and athletes alike flooded social media with tributes. One wrote, “You’ll always be one of the best!” while fellow 800m standout Bryce Hoppel commented, “Congrats on the career!”

Murphy’s retirement may have come earlier than expected, but his impact on American middle-distance running is undeniable. As he enters his next chapter, the sport says goodbye to a competitor who always gave his all—every lap, every race, every time.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Doping Dilemma: How WADA's Policies Are Failing Our Sport

I am alarmed by how the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) is policing our sport. It's disheartening to see athletes win races only to be stripped of their titles months later due to delayed doping allegations. This approach undermines the integrity of athletics and, in the long run, does more harm than good.

Having dedicated my life to running—I ran my first mile on February 16, 1962, and I discovered my passion for our sport after clocking a 2:08.5 in a 880-yard race JUne 1, 1963—I've witnessed the sport's evolution firsthand. As the founder and publisher of Runner’s World for 18 years and, since 2007, the editor and publisher of My Best Runs, I am concerned about the professional side of athletics.

The Flaws in WADA's Zero-Tolerance Policy

WADA's strict liability standard holds athletes accountable for any prohibited substance in their system, regardless of intent. This has led to controversial sanctions, such as the four-year ban of American runner Shelby Houlihan. She tested positive for the steroid nandrolone, which she attributed to consuming a pork burrito. Despite her defense, the ban was upheld, raising questions about the fairness of such rigid policies.

Overhauling the Banned Substances List

The extensive list of prohibited substances maintained by WADA includes compounds with minimal or no performance-enhancing effects. By focusing on substances with proven performance benefits, we can prevent athletes from being unjustly penalized for trace amounts of inconsequential substances.

The Problem with Retroactive Disqualifications

Delayed disqualifications due to retroactive positive tests cause significant disruptions. Athletes are stripped of titles months or even years after competitions, leading to uncertainty and diminished trust in the sport. Investing in faster, more sensitive testing methods is crucial to detect violations promptly, ensuring that competition results are reliable and fair.

Rethinking the "Whereabouts" Requirement

WADA's "whereabouts" rule mandates that athletes provide their location for one hour each day to facilitate out-of-competition testing. This constant monitoring infringes on athletes' privacy rights and imposes an unreasonable burden. Reevaluating this policy could help balance effective anti-doping measures with respect for personal freedoms.

Understanding Blood Doping and Its Implications

Blood doping, which involves increasing red blood cells to enhance performance, poses significant health risks, including blood clots, stroke, and heart attack. While it's linked to deaths in sports like cycling, there is no documented case of a runner dying directly from blood doping.

Interestingly, many doping violations involve substances like erythropoietin (EPO), which, despite health risks, haven't been directly linked to fatalities among runners. In contrast, alcohol—a legal substance—is responsible for approximately 3 million deaths worldwide annually. This disparity raises questions about the consistency of current substance regulations in sports.

The Business of Anti-Doping

Established in 1999 with an initial operating income of USD 15.5 million, WADA's budget has grown significantly, reaching USD 46 million in 2022. This increase reflects the expanding scope of WADA's activities, including research, education, and compliance monitoring.

Funding is primarily sourced from public authorities and the sports movement, with the International Olympic Committee (IOC) being a major contributor. Notably, in 2024, the United States withheld over USD 3.6 million—about 6% of WADA's annual budget—due to disputes over the agency's handling of doping cases.

EPO's Prevalence in Doping Cases

Erythropoietin (EPO) has a history of abuse in endurance sports due to its performance-enhancing capabilities. For example, Kenyan marathon runner Brimin Kipkorir was provisionally suspended in February 2025 after testing positive for EPO and Furosemide. This suspension adds to a series of high-profile doping cases affecting marathon running, especially among Kenyan athletes.

Adapting Governance and Policies to Maintain Trust

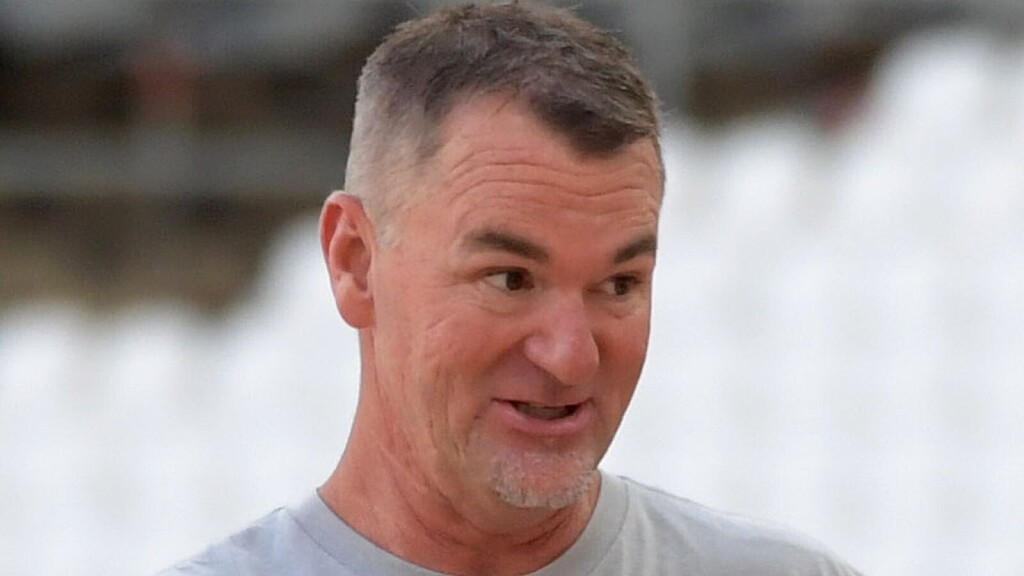

High-profile doping scandals have exposed flaws in the governance of athletics. The case of coach Alberto Salazar illustrates the challenges in enforcing anti-doping regulations. Salazar, who led the Nike Oregon Project, was initially banned for four years in 2019 for multiple anti-doping rule violations, including trafficking testosterone and tampering with doping control processes.

In 2021, he received a lifetime ban for sexual and emotional misconduct. His athlete, Galen Rupp, never tested positive for banned substances, yet his reputation suffered due to his association with Salazar. This situation underscores the importance of independent and transparent governance in maintaining the sport's integrity.

The banned drug list

The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) maintains a comprehensive list of substances and methods prohibited in sports to ensure fair competition and athlete health. This list is updated annually and includes categories such as:

· Anabolic Agents: These substances, including anabolic-androgenic steroids, promote muscle growth and enhance performance.

· Peptide Hormones, Growth Factors, and Related Substances: Compounds like erythropoietin (EPO) and human growth hormone (hGH) that can increase red blood cell production or muscle mass.

· Beta-2 Agonists: Typically used for asthma, these can also have performance-enhancing effects when misused.

· Hormone and Metabolic Modulators: Substances that alter hormone functions, such as aromatase inhibitors and selective estrogen receptor modulators.

· Diuretics and Masking Agents: Used to conceal the presence of other prohibited substances or to rapidly lose weight.

· Stimulants: Compounds that increase alertness and reduce fatigue, including certain amphetamines.

· Narcotics: Pain-relieving substances that can impair performance and pose health risks.

· Cannabinoids: Including substances like tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which can affect coordination and concentration.

· Glucocorticoids: Anti-inflammatory agents that, when misused, can have significant side effects.

Additionally, WADA prohibits certain methods, such as blood doping and gene doping, which can artificially enhance performance. It's important to note that while substances like alcohol are legal and widely consumed, they are not banned in most sports despite their potential health risks.

In contrast, substances like EPO, which have not been directly linked to fatalities among runners, are prohibited due to their performance-enhancing effects and potential health risks. This raises questions about the consistency and focus of current substance regulations in sports..

Regarding the percentage of doping violations involving EPO, specific statistics are not readily available. However, EPO has been a focal point in numerous high-profile doping cases, particularly in endurance sports. For detailed and up-to-date information, consulting WADA's official reports and statistics is recommended

Blood Doping Across Sports

Blood doping is prohibited across various sports, particularly those requiring high endurance. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) banned blood doping in 1985, and since then, numerous sports organizations have implemented similar prohibitions. Cycling has been notably affected, with many major champions associated with or suspended for blood doping.

In conclusion, while the fight against doping is essential to maintain fairness in athletics, the current methods employed by WADA may be causing more harm than good. It's imperative to develop more nuanced, fair, and effective anti-doping policies that protect both the integrity of the sport and the rights of its athletes.

by Bob Anderson

Login to leave a comment

The Chicago Marathon has a strong history

First run in 1977, this Sunday, Chicago hosts its 46th marathon (it lost 2020 to the Covid-19 pandemic; 1987 to sponsorship issues). One of the six Abbott World Marathon Majors, the history of the BofA Chicago Marathon has been one of rising, falling, and rising again.

In 2023, it witnessed its third men’s marathon world record, 2:00:35, gloriously produced by the late Kenyan star, Kelvin Kiptum, who tragically died in a car accident on February 11, 2024 (age 24 years), in Kaptagat, Kenya.

But the roots of the modern Bank of America Chicago Marathon traces back to 1982 when, in its sixth year, known as America’s Marathon/Chicago, the event rebooted, much as New York City 1976 was a reordering for the Big Apple 26-miler.

In America’s bicentennial year, the New York Road Runners expanded their event from four laps of Central Park to all five boroughs. It was a gamble. But in one fell swoop, the event grabbed the public’s attention, took on international importance, and ushered in a new era of urban marathons, even though they had run six previous marathons under the same banner.

In 1982, Chicago’s move from a regional marathon to the big time came about because of two things: one, the $600,000 budget put up by race sponsor, Beatrice Foods, and the hiring of one Robert Bright III of Far Hills, New Jersey to serve as athlete recruiter.

Bob Bright (left) at the Litchfield Hills Road Race in Connecticut with Nike east coast promo man, Todd Miller.

Recommended to the event by Olympians Frank Shorter and Garry Bjorlund, Bright had successfully elevated a modest 15K road race in Far Hills, New Jersey, called the Midland Run, to international prominence in 1980. So loaded was the Midland Run elite field, Sports Illustrated sent a reporter and photographer to cover the event.

What Bright brought to Chicago was zeal and a vision. Before Bright, there had been very little orchestration of competitive marathon racing. The Bright idea was simple: actively recruit a field of international athletes who came ready to run, so elite competition would become the hallmark of the event.

First, a brief history. For many decades, Boston dominated the marathon scene as essentially the only game in town. Yes, there was the Yonkers Marathonin New York, first contested in 1907; the Polytechnic Harriers’ Marathon for the Sporting Life trophy in England, which began in 1909. The Košice Peace Marathon in Slovakia joined the club in October 1924; Enschede and Fukuoka in 1947; Beppu in ’52.

But the Boston Athlettic Association’s attitude from its marathon’s inception in 1897 up to the mid-1980s remained, “We’re running our race on Patriots’ Day starting in Hopkinton, Massachusetts at noon. It will cost you three bucks to enter. See you at the bus line for the ride out to the start.” No bells, no whistles, no invitations.

When New York City debuted in 1970, it spun four laps of Central Park to total its 26.2 miles. But in 1976, with the city in a major financial difficulty amidst America’s Bicentennial, the New York Road Runners boldly took its marathon from the confines of Central Park and expanded it through all five boroughs hoping to attract more tourists.

Race Director Fred Lebow recruited a few big guns upfront to entice press coverage, Olympic gold and silver medalist Frank Shorter along with Shorter’s rival, American record holder from Boston 1975, fellow Olympian, Bill Rodgers. Everyone else filled in from behind, with the City of New York being the true star attraction.

First considered a onetime gimmick, the five-borough experience proved so successful, the NYRRs embraced it as the path forward. Still, the actual races in NYC were never very competitive. Rodgers won by three minutes over Shorter in ‘76, 2:10:10 to 2:13:12. Then dominated for the next three years, as well.

Chicago 1982 would be the first, full–blown, orchestrated marathon race, as Bright had a specific recruitment strategy.

“We wanted six guys who thought coming in that they had a chance to win,” said Bright. “Then we wanted six more behind them who figured they had a shot at the top 10. So, right away we didn’t go after a guy like Alberto Salazar (who was ranked number one in the world after wins in New York City in 1980, a short-course world record in ‘81, and a Boston title in 1982.)

“And if you figure that a top race has a main pack of 10 to 15 athletes, you’re going to double that number in invitations. That guarantees that even if two of every five don’t run well for one reason or another, you still have a big group ready to race.”

Redundancy was the key, the money, the magnet. The total amount taken home by runners from Chicago in 1982 was $130,000.

This was when Boston was still embracing its amateur roots, stiff-arming the new breed of runners looking to get paid for their craft. In New York, Lebow had to keep his payments under the table in order to avoid being billed for city services on race day.

Chicago put up $48,000 in prize money for the men in 1982, with $12,000 going to the winner, 600 for 15th place. The women’s split was $30,000, with $10,000 awarded for the win through $500 for 10th. The remaining $52,000 represented the grease in upfront, under-the-table appearance fees.

“We wanted the money to be respectable, but not overwhelming the first year,“ explained Bright, whose history as a dog sled racer and thoroughbred horse trainer made him one of the best judges of the running animal. “We didn’t want it to appear like the race was store-bought, like the Atlantic City pro race a few years ago, where the money was good, but no one took the race seriously.

“So, we put up $78,000 in prize money, which, to the public, doesn’t sound like all that much. But when you added on the appearance money, it represented as much as any other race handed out.“

For the money on offer, and the prestige of doing well against a field of that caliber – as good as the group assembled at the 1980 Moscow Olympics, according to Sweden’s Kjell Eric Stahl – what came down in Chicago 1982 was a new course record by University of Michigan grad Greg Meyer (2:10:59), along with 22 more sub -2:220s, and nine personal bests out of the first 11 finishers.

The top five women followed suit, led by Northampton, Massachusetts’s Nancy Conz, whose 2:33:33 also represented a new course record for Chicago, some 12 minutes faster than the old mark.

The event treated the athletes well; offered a new opportunity in the fall, competing with New York City; Chicago witnessed its first truly world-class marathon; the sponsor, Beatrice Foods, received enormous visibility for its dollars; and a new professionalism attended the art of marathon orchestration. Chicago was now the new kid on the block, with toys to match anyone’s.

But now the pressure was on, not just to maintain its pace, but to top itself in 1983. The story continues.

by Toni Reavis

Login to leave a comment

Bank of America Chicago

Running the Bank of America Chicago Marathon is the pinnacle of achievement for elite athletes and everyday runners alike. On race day, runners from all 50 states and more than 100 countries will set out to accomplish a personal dream by reaching the finish line in Grant Park. The Bank of America Chicago Marathon is known for its flat and...

more...Simpson, Frisbie, Rodriguez, Estrada Commit to Run Crazy 8s 8K Hoping for USATF National Championshisp

With the announcement that the Ballad Health Niswonger Children’s Network Crazy 8s 8K Run will host both the USATF Men’s & Women’s 8K Road Championship Presented by Gatorade on July 20th, competition is heating up for both championships.

Olympic bronze medalist Jenny Simpson and Annie Frisbie will be two of the headliners in the women’s field with Isai Rodriguez and Diego Estrada the early favorites on the men’s side.“We’re off to a good start,” said co-director Hank Brown.

“We are receiving tremendous interest from some of the best runners from around the country. We’re expecting 40-50 elite runners in the USATF championship which will be very exciting.”

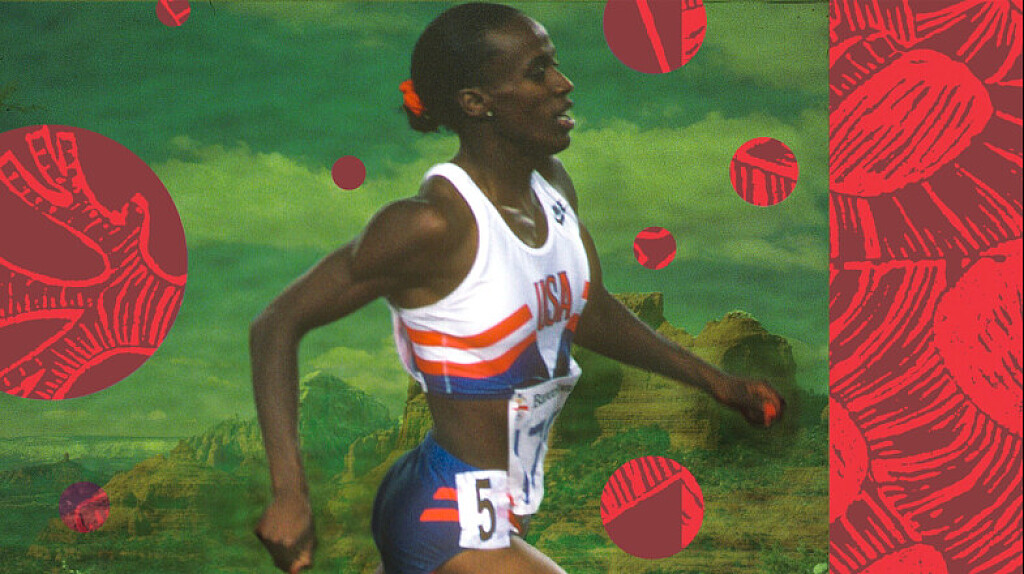

Simpson is arguably one of the more recognizable women’s middle/long distance runners in the United States. She won the bronze medal in the 1500 meters at the 2016 Rio Olympics, the gold medal at the 2011 World Championships, and followed with silver medals at the 2013 and 2017 World Championships Simpson is a former American record holder for the 3000 meter steeplechase and has represented the United States at three Olympics – 2008 Beijing, 2012 London, and 2016 Rio.

Frisbie is on a personal tear recently, running personal bests in 2024 for the 10K (31:49), 15K (49:28), 25K (1:22:37), and half marathon (1:07:34, 1st place). She is running her best and is in excellent shape.In 2023, the men’s race came down to a sprint finish in J. Fred Johnson Stadium with Clayton Young outlasting Andrew Colley and Isai Rodriguez. Young will be going to Paris to run the marathon and Colley is nursing a sore foot, so Rodriguez will be the top returning finisher (Colley is still tentative).

Rodriguez has a 10,000 meter personal-best under 28 minutes and was the Pan Am Games 10k champion in 2023.Estrada is a veteran runner making a successful comeback in 2024. He represented his native Mexico in the 10,000 meters in the 2012 London Olympics, but became a US citizen in 2014 at which time became eligible to represent the USA in international competition.

He has an impressive 10k time of 27:30 set in 2015, and 5K of 13:31 at the Carlsbad 5K in 2014. He is now 34 and quite possibly running his best times in 2024.

He placed fifth at the Aramco Houston Half Marathon in January, running a very fast 1:00:49, which is a personal best at that distance and tnen followed that a thrid-. place finish at the USATF 15K Championship in Jacksonville. In May he set an American best of 1:13:09 at the USATF 25K Championship, winning the Amway 25K River Run in Grand Rapids, MI.

“We are thrilled to have these guys and gals at Crazy 8s,” said Brown. “When we decided to host the USATF 8K Championship this is exactly the caliber of runners we were hoping to attract to Kingsport.”

The Regional Eye Center is offering a $10,008 American Record bonus for men who can break Alberto Salazar’s record of 22:04 (1981) or women who can break Deena Kastor’s record of 24:36 (2005).

In addition to the bonus, the race is offering prize money to the top 10 in the USATF Men’s and Women’s Championships.Sponsors are Ballad Health Niswonger Children’s Network, Gatorade, The Regional Eye Center, Eastman Credit Union, Kingsport Pediatric Dentistry, Food City, Martin Dentistry, Mycroft Signs, Culligan, Associated Orthopaedics of Kingsport, and JA Street.

by TriCitiesSports.com

Login to leave a comment

Crazy 8s 8k Run

Run the World’s Fastest 8K on the world famous figure-8 course on beautiful candle-lit streets with a rousing finish inside J. Fred Johnson Stadium. Crazy 8s is home to womens’ 8-kilometer world record (Asmae Leghzaoui, 24:27.8, 2002), and held the men’s world record (Peter Githuka, 22:02.2, 1996), until it was broken in 2014. Crazy 8s wants that mens’ record back. ...

more...The Pill That Over Half the Distance Medallists Used at the 2023 Worlds

What's the deal with sodium bicarbonate?What if there was a pill, new to the market this year, that was used by more than half of the distance medalists at the 2023 World Athletics Championships? A supplement so in-demand that there was a reported black market for it in Budapest, runners buying from other runners who did not advance past the preliminary round — even though the main ingredient can be found in any kitchen?

How did this pill become so popular? Well, there are rumors that Jakob Ingebrigtsen has been taking it for years — rumors that Ingebrigtsen’s camp and the manufacturers of the pill will neither confirm nor deny.

So about this pill…does it work? Does it actually boost athletic performance? Ask a sports scientist, someone who’s studied it for more than a decade, and they’ll tell you yes.

“There’s probably four or five legal, natural supplements, if you will, that seem to have withstood the test of time in terms of the research literature and [this pill] is one of those,” says Jason Siegler, Director of Human Performance in the College of Health Solutions at Arizona State University.

But there’s a drawback to this pill. It could…well, let’s allow Luis Grijalva, who used it before finishing 4th in the World Championship 5,000m final in Budapest, to explain.

“I heard stories if you do it wrong, you chew it, you kind of shit your brains out,” Grijalva says. “And I was a little bit scared.”

The research supports that, too.

“[Gastrointestinal distress] has by far and away been the biggest hurdle for this supplement,” Siegler says.Okay, enough with the faux intrigue. If you’ve read the subtitle of this article, you know the pill we are talking about is sodium bicarbonate. Specifically, the Maurten Bicarb System, which has been available to the public since February and which has been used by some of the top teams in endurance sports: cycling juggernaut Team Jumbo-Visma and, in running, the On Athletics Club and NN Running Team. (Maurten has sponsorship or partnership agreements with all three).Some of the planet’s fastest runners have used the Maurten Bicarb System in 2023, including 10,000m world champion Joshua Cheptegei, 800m silver medalist Keely Hodgkinson, and 800m silver medalist Emmanuel Wanyonyi. Faith Kipyegon used it before winning the gold medal in the 1500m final in Budapest — but did not use it before her win in the 5,000m final or before any of her world records in the 1500m, mile, and 5,000m.

Herman Reuterswärd, Maurten’s head of communications, declined to share a full client list with LetsRun but claims two-thirds of all medalists from the 800 through 10,000 meters (excluding the steeplechase) used the product at the 2023 Worlds.

After years of trial and error, Maurten believes it has solved the GI issue, but those who have used their product have reported other side effects. Neil Gourley used sodium bicarbonate before almost every race in 2023, and while he had a great season — British champion, personal bests in the 1500 and mile — his head ached after races in a way it never had before. When Joe Klecker tried it at The TEN in March, he felt nauseous and light-headed — but still ran a personal best of 27:07.57. In an episode of the Coffee Club podcast, Klecker’s OAC teammate George Beamish, who finished 5th at Worlds in the steeplechase and used the product in a few races this year, said he felt delusional, dehydrated, and spent after using it before a workout this summer.

“It was the worst I’d felt in a workout [all] year, easily,” Beamish said.

Not every athlete who has used the Maurten Bicarb System has felt side effects. But the sport as a whole is still figuring out what to do about sodium bicarbonate.

Many athletes — even those who don’t have sponsorship arrangements with Maurten — have added it to their routines. But Jumbo-Visma’s top cyclist, Jonas Vingegaard — winner of the last two Tours de France — does not use it. Neither does OAC’s top runner, Yared Nuguse, who tried it a few times in practice but did not use it before any of his four American record races in 2023.“I’m very low-maintenance and I think my body’s the same,” Nuguse says. “So when I tried to do that, it was kind of like, Whoa, what is this? My whole body felt weird and I was just like, I either did this wrong or this is not for me.”

How sodium bicarbonate works

The idea that sodium bicarbonate — aka baking soda, the same stuff that goes in muffins and keeps your refrigerator fresh — can boost athletic performance has been around for decades.

“When you’re exercising, when you’re contracting muscle at a really high intensity or a high rate, you end up using your anaerobic energy sources and those non-oxygen pathways,” says Siegler, who has been part of more than 15 studies on sodium bicarbonate use in sport. “And those pathways, some of the byproducts that they produce, one of them is a proton – a little hydrogen ion. And that proton can cause all sorts of problems in the muscle. You can equate that to that sort of burn that you feel going at high rates. That burn, most of that — not directly, but indirectly — is coming from the accumulation of these little hydrogen ions.”

As this is happening, the kidneys produce bicarbonate as a defense mechanism. For a while, bicarbonate acts as a buffer, countering the negative effects of the hydrogen ions. But eventually, the hydrogen ions win.The typical concentration of bicarbonate in most people hovers around 25 millimoles per liter. By taking sodium bicarbonate in the proper dosage before exercise, Siegler says, you can raise that level to around 30-32 millimoles per liter.

“You basically have a more solid first line of defense,” Siegler says. “The theory is you can go a little bit longer and tolerate the hydrogen ions coming out of the cell a little bit longer before they cause any sort of disruption.”

Like creatine and caffeine, Siegler says the scientific literature is clear when it comes to sodium bicarbonate: it boosts performance, specifically during events that involve short bursts of anaerobic activity. But there’s a catch.

***

Bicarb without the cramping

Sodium bicarbonate has never been hard to find. Anyone can swallow a spoonful or two of baking soda with some water, though it’s not the most appetizing pre-workout snack. The problem comes when the stomach tries to absorb a large amount of sodium bicarbonate at once.

“You have a huge charged load in your stomach that the acidity in your stomach has to deal with and you have a big shift in the partial pressure of carbon dioxide across the gut,” Siegler says. “And that’s what gives you the cramping.”

A few years ago, Maurten was trying to solve a similar problem for marathoners trying to ingest large amounts of carbohydrates during races. The result was their carbohydrate drink, which relies on something called a hydrogel to form in the stomach. The hydrogel resists the acidity of the stomach and allows the carbohydrates to be absorbed in the intestine instead, where there is less cramping.

“We thought, okay, we are able to solve that one,” Reuterswärd says. “Could we apply the hydrogel technology to something else that is really risky to consume that could be beneficial?”

For almost four years, Maurten researched the effects of encapsulating sodium bicarbonate in hydrogels in its Swedish lab, conducting tests on middle-distance runners in Gothenburg. Hydrogels seemed to minimize the risk, but the best results came when hydrogels were paired with microtablets of sodium bicarbonate.

The result was the Maurten Bicarb System — “system,” because the process for ingesting it involves a few steps. Each box contains three components: a packet of hydrogel powder, a packet of tiny sodium bicarbonate tablets, and a mixing bowl. Mix the powder with water, let it stand for a few minutes, and sprinkle in the bicarb.The resulting mixture is a bit odd. It’s gooey. It’s gray. It doesn’t really taste like anything. It’s not quite liquid, not quite solid — a yogurt-like substance flooded with tiny tablets that you eat with a spoon but swallow like a drink.

The “swallow” part is important. Chew the tablets and the sodium bicarbonate will be absorbed before the hydrogels can do their job. Which means a trip to the toilet may not be far behind.

When Maurten launched its Bicarb System to the public in February 2023, it did not have high expectations for sales in year one.

“It’s a niche product,” Reuterswärd says. “From what we know right now, it maybe doesn’t make too much sense if you’re an amateur, if you’re just doing 5k parkruns.”

But in March, Maurten’s product began making headlines in cycling when it emerged that it was being used by Team Jumbo-Visma, including by stars Wout van Aert and Primož Roglič. Sales exploded. Because bicarb dosage varies with bodyweight, Maurten’s system come in four “sizes.” And one size was selling particularly well.

“If you’re an endurance athlete, you’re around 60-70 kg (132-154 lbs),” Reuterswärd says. “We had a shortage with the size that corresponded with that weight…The first couple weeks, it was basically only professional cyclists buying all the time, massive amounts. And now we’re seeing a similar development in track & field.”

If there was a “Jumbo-Visma” effect in cycling, then this summer there was a “Jakob Ingebrigtsen” effect in running.To be clear: there is no official confirmation that Ingebrigtsen uses sodium bicarbonate. His agent, Daniel Wessfeldt, did not respond to multiple emails for this story. When I ask Reuterswärd if Ingebrigtsen has used Maurten’s product, he grows uncomfortable.

“I would love to be very clear here but I will have to get back to you,” Reuterswärd says (ultimately, he was not able to provide further clarification).

But when Maurten pitches coaches and athletes on its product, they have used data from the past two years on a “really good” 1500 guy to tout its effectiveness, displaying the lactate levels the athlete was able to achieve in practice with and without the use of the Maurten Bicarb System. That athlete is widely believed to be Ingebrigtsen. Just as Ingebrigtsen’s success with double threshold has spawned imitators across the globe, so too has his rumored use of sodium bicarbonate.

Grijalva says he started experimenting with sodium bicarbonate “because everybody’s doing it.” And everybody’s doing it because of Ingebrigtsen.

“[Ingebrigtsen] was probably ahead of everybody at the time,” Grijalva said. “Same with his training and same with the bicarb.”

OAC coach Dathan Ritzenhein took sodium bicarbonate once before a workout early in his own professional career, and still has bad memories of swallowing enormous capsules that made him feel sick. Still, he was willing to give it a try with his athletes this year after Maurten explained the steps they had taken to reduce GI distress.

“Certainly listening to the potential for less side effects was the reason we considered trying it,” says Ritzenhein. “I don’t know who is a diehard user and thinks that it’s really helpful, but around the circuit I know a lot of people that have said they’ve [tried] it.”

Coach/agent Stephen Haas says a number of his athletes, including Gourley, 3:56 1500 woman Katie Snowden, and Worlds steeple qualifier Isaac Updike, tried bicarb this year. In the men’s 1500, Haas adds, “most of the top guys are already using it.”

Yet 1500-meter world champion Josh Kerr was not among them. Kerr’s nutritionist mentioned the idea of sodium bicarbonate to him this summer but Kerr chose to table any discussions until after the season. He says he did not like the idea of trying it as a “quick fix” in the middle of the year.

“I review everything at the end of the season and see where I could get better,” Kerr writes in a text to LetsRun. “As long as the supplement is above board, got all the stamps of approvals needed from WADA and the research is there, I have nothing against it but I don’t like changing things midseason.”

***

So does it actually work?

Siegler is convinced sodium bicarbonate can benefit athletic performance if the GI issues can be solved. Originally, those benefits seemed confined to shorter events in the 2-to 5-minute range where an athlete is pushing anaerobic capacity. Buffering protons does no good to short sprinters, who use a different energy system during races.

“A 100-meter runner is going to use a system that’s referred to the phosphagen or creatine phosphate system, this immediate energy source,” Siegler says. “…It’s not the same sort of biochemical reaction that eventuates into this big proton or big acidic load. It’s too quick.”

But, Siegler says, sodium bicarbonate could potentially help athletes in longer events — perhaps a hilly marathon.

“When there’s short bursts of high-intensity activity, like a breakaway or a hill climb, what we do know now is when you take sodium bicarbonate…it will sit in your system for a number of hours,” Siegler says. “So it’s there [if] you need it, that’s kind of the premise behind it basically. If you don’t use it, it’s fine, it’s not detrimental. Eventually your kidneys clear it out.”Even Reuterswärd admits that it’s still unclear how much sodium bicarbonate helps in a marathon — “honestly, no one knows” — but it is starting to be used there as well. Kenya’s Kelvin Kiptum used it when he set the world record of 2:00:35at last month’s Chicago Marathon; American Molly Seidel also used it in Chicago, where she ran a personal best of 2:23:07.

Siegler says it is encouraging that Maurten has tried to solve the GI problem and that any success they experience could spur other companies to research an even more effective delivery system (currently the main alternative is Amp Human’s PR Lotion, a sodium bicarbonate cream that is rubbed into the skin). But he is waiting for more data before rendering a final verdict on the Maurten Bicarb System.

“I haven’t seen any peer-reviewed papers yet come out so a bit I’m hesitant to be definitive about it,” Siegler said.

Trent Stellingwerff, an exercise physiologist and running coach at the Canadian Sport Institute – Pacific, worked with Siegler on a 2020 paper studying the effect of sodium bicarbonate on elite rowers. A number of athletes have asked him about the the Maurten Bicarb System, and some of his marathoners have used the product. Like Siegler, he wants to see more data before reaching a conclusion.

“I always follow the evidence and science, and to my knowledge, as of yet, I’m unaware of any publications using the Maurten bicarb in a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial,” Stellingwerff writes in a text to LetsRun. “So without any published data on the bicarb version, I can’t really say it does much.”

The closest thing out there right now is a British study conducted by Lewis Goughof Birmingham City University and Andy Sparks of Edge Hill University. In a test of 10 well-trained cyclists, Gough and Sparks found the Maurten Bicarb System limited GI distress and had the potential to improve exercise performance. Reuterswärd says the study, which was funded by Maurten, is currently in the review process while Gough and Sparks suggested further research to investigate their findings.

What about the runners who used sodium bicarbonate in 2023?

Klecker decided to give bicarb a shot after Maurten made a presentation to the OAC team in Boulder earlier this year. He has run well using bicarb (his 10,000 pb at The TEN) and without it (his 5,000 pb in January) and as Klecker heads into an Olympic year, he is still deciding whether the supposed benefits are worth the drawbacks, which for him include nausea and thirst. He also says that when he has taken the bicarb, his muscles feel a bit more numb than usual, which has made it more challenging for him to gauge his effort in races.

“There’s been no, Oh man I felt just so amazing today because of this bicarb,” Klecker says. “If anything, it’s been like, Oh I didn’t take it and I felt a bit more like myself.”

Klecker also notes that his wife and OAC teammate, Sage Hurta-Klecker, ran her 800m season’s best of 1:58.09 at the Silesia Diamond League on July 16 — the first race of the season in which she did not use bicarb beforehand.

A number of athletes in Mike Smith‘s Flagstaff-based training group also used bicarb this year, including Grijalva and US 5,000 champion Abdihamid Nur. Grijalva did not use bicarb in his outdoor season opener in Florence on June 2, when he ran his personal best of 12:52.97 to finish 3rd. He did use it before the Zurich Diamond League on August 31, when he ran 12:55.88 to finish 4th.“I want to say it helps, but at the same time, I don’t want to rely on it,” Grijalva says.

Almost every OAC athlete tried sodium bicarbonate at some point in 2023. Ritzenhein says the results were mixed. Some of his runners have run well while using it, but the team’s top performer, Nuguse, never used it in a race. Ritzenhein wants to continue testing sodium bicarbonate with his athletes to determine how each of them responds individually and whether it’s worth using moving forward.

That group includes Alicia Monson, who experimented with bicarb in 2023 but did not use it before her American records at 5,000 and 10,000 meters or her 5th-place finish in the 10,000 at Worlds.

“It’s not the thing that’s going to make or break an athlete,” Ritzenhein says. “…It’s a legal supplement that has the potential, at least, to help but it doesn’t seem to be universal. So I think there’s a lot more research that needs to be done into it and who benefits from it.”

The kind of research scientists like Stellingwerff want to see — double-blind, controlled clinical trials — could take a while to trickle in. But now that anyone can order Maurten’s product (it’s not cheap — $65 for four servings), athletes will get to decide for themselves whether sodium bicarbonate is worth pursuing.

“The athlete community, obviously if they feel there’s any sort of risk, they’re weighing up the risk-to-benefit ratio,” Siegler said. “The return has got to be good.”

Grijalva expects sodium bicarbonate will become part of his pre-race routine next year, along with a shower and a cup of coffee. Coffee, and the caffeine contained wherein, may offer a glimpse at the future of bicarb. Caffeine has been widely used by athletes for longer than sodium bicarbonate, and the verdict is in on that one: it works. Yet plenty of the greats choose not to use it.

Nuguse is among them. He does not drink coffee — a fact he is constantly reminded of by Ritzenhein.

“I make jokes almost every day about it,” Ritzenhein says. “His family is Ethiopian – coffee tradition and ceremony is really important to them.”

Ritzenhein says he would love it if Nuguse drank a cup of coffee sometime, but he’s not going to force it on him. Some athletes, Ritzenhein says, have a tendency to become neurotic about these sorts of things. That’s how Ritzenhein was as an athlete. It’s certainly how Ritzenhein’s former coach at the Nike Oregon Project, Alberto Salazar, was — an approach that ultimately earned Salazar a four-year ban from USADA.

Ritzenhein says he has no worries when it comes to any of his athletes using sodium bicarbonate — Maurten’s product is batch-tested and unlike L-carnitine, there is no specific protocol that must be adhered to in order for athletes to use it legally under the WADA Code. Still, there is something to be said for keeping things simple.

“Yared knows how his body feels,” Ritzenhein says. “…He literally rolls out of practice and comes to practice like a high schooler with a Eggo waffle in hand. Probably more athletes could use that kind of [approach].”

Talk about this article on our world-famous fan forum / messageboard.

by Let’s Run

Login to leave a comment

The Mysterious Case of the Asthmatic Olympians

You won’t freeze your lungs exercising outdoors this winter, but there are reasons to be cautious about inhaling extremely cold air

When an athlete reaches the podium despite a prior medical event—a cancer diagnosis, say, or a car accident—we consider it a triumph of the human spirit. When a bunch of athletes do so, and all of them have suffered the same setback, we can be forgiven for wondering what’s going on. According to the International Olympic Committee, roughly one in five competitive athletes suffers from exercise-induced bronchoconstriction, or EIB, an asthma-like narrowing of the airways triggered by strenuous exercise. The numbers are even higher in endurance and winter sports. Puzzlingly, studies have found that athletes with EIB who somehow make it to the Olympics are more likely to medal. What’s so great about wheezing, chest tightness, and breathlessness?

The answer isn’t what you’re thinking. Sure, it’s possible that some athletes get a boost because an EIB diagnosis allows them to use otherwise-banned asthma medications. But there’s a simpler explanation: breathing high volumes of cold or polluted air dries out the airways, leading to an overzealous immune response and potential long-term damage. “It’s well established that high training loads and ventilatory work increase the degree of airway hyper-responsiveness and hence development of asthma and EIB,” explains Morten Hostrup, a sports scientist at the University of Copenhagen and lead author of a new review on EIB in the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. In other words, the athletes who train hard enough to podium are more likely to develop EIB as a result.

That trade-off might be worthwhile if it means competing at the Olympics. For those of us who simply enjoy spending our winter days vigorously exploring the outdoors, the risk of EIB remains mostly unknown territory. Activities with the highest risk involve sustained efforts of at least five minutes, particularly if they take place in cold or polluted air. Cold air doesn’t hold much moisture, so it dries the airways. This affects skiers, runners, and triathletes, among others. Indoor environments like pools and ice rinks are also a problem, because of the chloramines produced by pool water and exhaust from Zambonis. As a result, swimmers, ice skaters, and hockey players are also at elevated risk of EIB. Over time, repeated attacks can damage the cells that line the airways.

Unfortunately, many athletes develop symptoms of EIB without realizing the underlying problem. After all, the feeling that you can’t catch your breath is pretty much written into the job description of most endurance activities. But starting in the 1990s, sports scientists began to suspect that top athletes had more breathing problems than would be expected. Before the 1998 Winter Games, U.S. Olympic Committee physiologists examined Nagano-bound athletes to see whose airways showed abnormal constriction in response to arduous exercise. Almost a quarter of the athletes tested positive, including half the cross-country ski team.

One reason EIB often flies under the radar is that the usual diagnostic workups aren’t challenging enough to provoke an attack in conditioned athletes. Among the accusations against disgraced coach Alberto Salazar was that he showed athletes how to fool EIB tests to get permission to use asthma meds. “He had a specific protocol,” star 5,000-meter runner Lauren Fleshman told ProPublica in 2015. “You would go to the local track and run around the track, work yourself up to having an asthma attack, and then run down the street, up 12 flights of stairs to the office and they would be waiting to test you.” Salazar certainly gave some shady advice, including encouraging Fleshman to push for the highest possible dosage of medication. But his tips for gaming the asthma test were similar to what USOC physiologists advocate, and an IOC consensus statement published last spring also concluded that more intense exercise challenges are better for diagnosing EIB in conditioned athletes. If you’re really fit, in other words, the rinky-dink treadmill in the doctor’s office isn’t going to push you hard enough.

If you do get an EIB diagnosis, your doctor can prescribe asthma medication, including inhaled corticosteroids like fluticasone and airway dilators like salbutamol. If you’re an elite athlete subject to drug testing, you’ll need to tread carefully, since some of those medications are either banned or restricted to a maximum dosage. Hostrup and his colleagues note that there’s also evidence that fish oils high in omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin C, and even caffeine might help reduce EIB symptoms. And on the non-pharmaceutical side, you can minimize the chance of an attack by doing a thorough warm-up of 20 to 30 minutes, including six to eight 30-second sprints. This can temporarily deplete the inflammatory cells that would otherwise trigger an airway-narrowing attack.

The best outcome of all, of course, is to avoid developing the problem in the first place. In 2008, I interviewed a Canadian military scientist named Michel Ducharme, who told me stories of cross-country skiers swallowing Vaseline in an attempt to protect their airways from the cold. This is a terrible idea on many levels—and, he assured me, totally unnecessary. Air warms up very quickly when you inhale it, so there’s no risk of freezing your throat tissue. But dryness is another question, and scientists have reconsidered whether some kind of protection—just not Vaseline—could be useful if you’re going hard on cold days.

One option is a heat-and-moisture-exchange mask, which warms and moistens the air you inhale. A company called AirTrim makes them with a range of levels of resistance for training or racing. Several studies have found that this type of mask seems to reduce EIB attacks. Research by Michael Kennedy at the University of Alberta found that EIB risk increases significantly when temperatures drop below about five degrees Fahrenheit. The precise threshold depends on conditions and individual susceptibility, so if you start coughing or wheezing, that’s a sign your airways are irritated. If you don’t have a breathing mask, a scarf or a Buff over your mouth can offer a temporary solution.

Don’t take all this as a warning against getting outdoors in the winter. I live in Canada, so staying inside when it’s below five degrees Fahrenheit would be a death sentence. But I’m no longer as macho about the cold as I used to be. I wear puffy mittens and merino base layers, and when my snot starts to freeze I cover my mouth and nose. Athletes with EIB may do better than their unimpaired peers at the Olympics, but that’s one edge I can do without.

by Outside Online

Login to leave a comment

Nike and Alberto Salazar settle $20 million lawsuit with Mary Cain over alleged abuse

On Monday, Nike, disgraced coach Alberto Salazar and distance runner Mary Cain reached a settlement in the $20 million lawsuit filed by Cain, as reported by The Oregonian.

The lawsuit accused Salazar of emotional and physical abuse towards Cain and highlighted Nike’s alleged failure to provide adequate oversight during her time with Salazar. Cain, who ran for Nike’s Oregon Project from 2012 to 2016, spoke out in 2019 about abuse within the program, exposing broader cultural issues at Nike, including a reported “boys’ club” atmosphere.

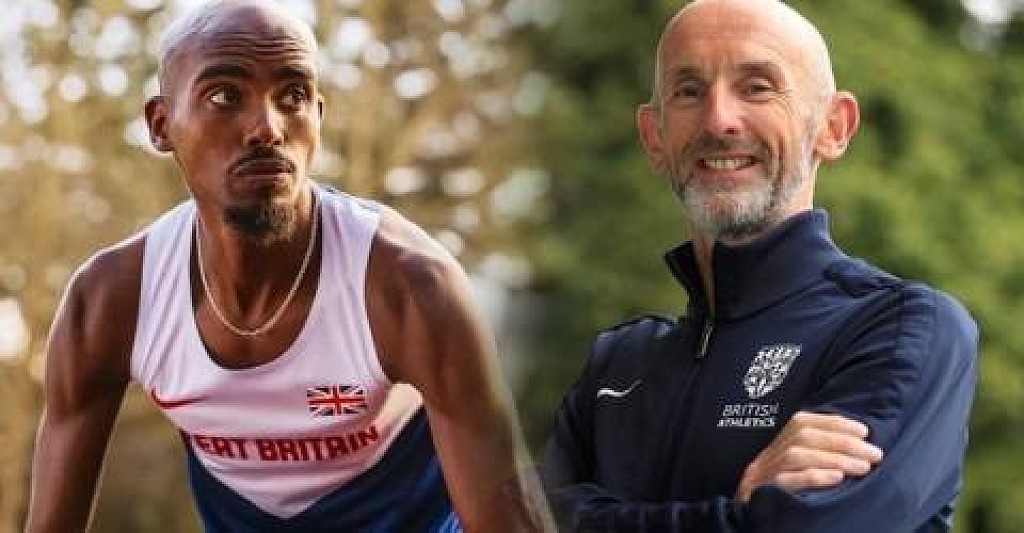

Salazar, once celebrated for coaching Olympic medallists Mo Farah, Galen Rupp and Matt Centrowitz, faced a permanent ban from working with U.S. track and field by U.S. SafeSport for alleged sexual assault and a doping scandal. Nike disbanded the Oregon Project in 2019, and Salazar’s name was removed from a building on the company’s campus following the ban.

Cain’s allegations against Salazar included controlling behavior, inappropriate comments about her body and humiliating practices, which led to depression, an eating disorder and self-harm. Nike was implicated in the lawsuit for allegedly not taking sufficient action to protect Cain, a sponsored athlete. Salazar denied the allegations, emphasizing his commitment to athletes’ well-being. Cain filed the $20 million lawsuit in 2021.

Numerous runners have come out and criticized Nike for its lack of support for female athletes. In 2018, U.S. Olympian Allyson Felix called out the brand for allegedly asking her to take a 70 per cent pay cut during her pregnancy, prompting Felix to leave Nike and join the female-powered brand Athleta before the Tokyo Olympics.

by Marley Dickinson

Login to leave a comment

Galen Rupp: Healthy Again After Two Rough Years

The past two years have been the most difficult of Galen Rupp’s career.

The four-time Olympian’s racing in 2022 and the first nine months of 2023 have included a mix of subpar results and DNFs. The last time he finished a marathon was July 2022, when he ran 2:09:36 at the 2022 World Championships in Eugene, Oregon, and finished 19th. Cameras caught him walking for short stretches during the final miles of the race. Last November, he started the New York City Marathon but dropped out before 18 miles. At the NYC Half in March this year, which was the last time he raced, Rupp was 17th in 1:04:57.

You’d have to go back to October 2021, when he finished second at the Chicago Marathon in 2:06:35, that he last had a result he was happy about.

Now, Rupp, 37, is back on the starting line at Chicago, having overhauled his mechanics and having spent the past two months away from Portland, Oregon, where he lives, and training in Flagstaff, Arizona, where his coach, Mike Smith, lives. For the first time in several years, Rupp is free of the back pain that had plagued him. He spoke to reporters at a press conference in Chicago. Here’s what we learned:

He was in pain just walking around last summer

After last year’s world championships, Rupp tried to push through the pain for his New York City Marathon buildup, but it didn’t work. Smith told Rupp that he needed to get fully healthy before he could start training again.

The NYC Marathon “was a really big wakeup call,” Rupp said, calling himself “hard-headed” in his attempt to run it, just getting through one workout at a time. “For a long time I was just surviving,” he said. “You can’t do that as an elite athlete.”

He’s been working on mechanics…

Rupp has been rebuilding his form, which he thinks was thrown off after his back injury. He’s been working with a team of therapists and running mechanics experts to fix what he called the “terrible” form he had in New York City last year. “That’s been the biggest thing I’ve been addressing,” he said. “I’ve got to clean that stuff up. It takes a lot of time. Running is such a repetitive motion. If you’re doing things a little funky or off, it starts to engrain in there. This past year, I’ve been trying to undo that.”

When pressed for specifics, Rupp cited the positioning of his hips, and how his left foot interacted with the ground. “My whole body was twisted up, in a nutshell,” he said.

…but now he’s training well

Rupp said his buildup has gone about as well as the one he did before Chicago two years ago and he’s returned to his previous volume, which at times has been 130 miles per week with 25-mile long runs. He was vague about his goals for Sunday, saying during the press conference portion of the day, “Above all else, I really just want to have a real solid race here.”

He’s unclear what role, if any, Alberto Salazar will have in his training going forward

Alberto Salazar, Rupp’s former coach with the Nike Oregon Project, was banned by the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency for 4 years in September 2019 for anti-doping violations. Subsequently, Salazar was banned permanently by the U.S. Center SafeSport for sexual misconduct.

Rupp was asked if he would use Salazar in a consulting role going forward.

“I’m not really going to get into that too much,” he said. “I am looking forward to having a personal relationship with [Salazar] going forward, but I’ve got to figure out what exactly the rules are. Things have been going good with Mike. It’s been a great buildup in Flagstaff. I’ve had enough to worry about getting ready for this race. I’ve been focusing on my training.”

He has no problem with the announced noon start at the Olympic Marathon Trials

Rupp said he is not a morning person, and whatever the weather conditions are like at the Trials, scheduled for noon on February 3, 2024, in Orlando, he’ll be ready. “That’s the one thing I absolutely hate about road running and the marathon. I’d rather run at 11 or 12 than 7 in the morning,” he said.

He also has no problem with the current Olympic marathon qualifications system, in which runners can “unlock” spots for their countries, based on running a qualifying time, finishing top 5 in a World Marathon Major, or being high enough in the world rankings.

But if an athlete unlocks a spot, he or she does not automatically get it. In the U.S., those spots go to the top three finishers of the Olympic Marathon Trials.

Rupp hasn’t paid much attention to it.

“The Trials to me has always come down to getting it done on that day,” he said. “You’ve got to get in the top three. That’s the way it’s always been. That pressure is a great thing. I learned at a young age, having to go through that process, about getting it right on that day, being ready and mentally dealing with all that pressure. I think it has served me well when I got to the Olympics.”

He has two Olympic medals to prove it.

He thinks he has several more years ahead of him.

Rupp isn’t giving thought to retiring any time soon. He hopes to get to the 2028 Olympics in Los Angeles, when his kids—he has 9-year-old twins and a 7- and 4-year-old—would be old enough to remember and appreciate it.

He doesn’t feel like age right now is a limiting factor. Staying healthy is.

“I truly believe, especially with the marathon, you can keep doing this well into your 40s,” he said. “A lot of it comes down to your health and how you’re moving. I really feel good about where I’m at.”

He also said he doesn’t lack for motivation, even after two Olympic medals and a Chicago Marathon title in 2017. He still enjoys getting the most out of himself as he can.

“I love movement, training, all that,” he said. “I love the journey of getting ready for races. That fire burns as hot as ever.”

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

Scott Fauble Is Aiming for the Olympic Standard at Berlin Marathon

Fauble will hope to become first American man to hit 2:08:10 Olympic standard in Sunday’s race

Scott Fauble was not planning on running a fall marathon in 2023. On April 17, he finished 7th at the Boston Marathon to earn top American honors — just as he did in Boston and New York in 2022. His time of 2:09:44 represented the fourth sub-2:10 of his career, making him just the seventh American to accomplish that feat after Ryan Hall, Galen Rupp, Meb Keflezighi, Khalid Khannouchi, Alberto Salazar, and Mbarak Hussein. In previous years, a top-10 finish at a World Marathon Major counted as an automatic qualifying standard for the Olympic marathon; Fauble, with three straight top-10 finishes on his resume, figured he was in good position for Paris and could shift his focus to the US Olympic Trials in February 2024.

But the Olympic qualifying system for 2024 is far more complicated than in previous years, with ever-shifting world rankings and things like “quota reallocation places” creating confusion among fans and athletes alike. Any athlete ranked in the top 65 of the filtered “Road to Paris” list on January 30, 2024, is considered qualified…except the “Road to Paris” list does not currently exist. After Boston, Fauble, who is currently ranked 122nd* — that’s in the world rankings, which is a different list than “Road to Paris” — tried to take a closer look at where he stood, creating spreadsheets and projecting where he might rank after accounting for time qualifiers, the three-athlete-per-country limit, and potential changes after the 2023 fall marathon season. After a while, his brain began to hurt.

“I felt like the Pepe Silvia meme from It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia,” Fauble said. “…It was like, this is complicated and stressful and I can just get the standard. This doesn’t need to be an issue.”

That is why Fauble, begrudgingly, made the decision to run the Berlin Marathon. He was not initially looking forward to the race, but with a strong training block in Boulder behind him and the race just four days away, he has changed his tune.

“I’m very excited,” Fauble said. “I wasn’t planning on doing a fall marathon after Boston and I had to figure out ways to get excited for it and I think that’s one of the things that has fired me up, actually seeing how fast I can go and pushing for a PR as opposed to letting the race play out and seeing what I can do.”

Chasing a time is a dramatically different approach to Fauble’s typical marathon M.O. Of the nine marathons he has run, only two have featured pacemakers: his debut in Frankfurt in 2017, and the Marathon Project in 2020. When Fauble runs Boston and New York, the hilly courses where he has found the greatest success, he does not enter with a goal time in mind. Instead, Fauble will wait until the race begins and assess a number of factors — the weather, how he’s feeling, how fast the other runners are going — before deciding which pace to run. Typically, that has led to Fauble letting the leaders go early and picking off stragglers as they fade over the second half of the race.

Berlin will be different. There are no hills to account for, and while Fauble will still fight for every place, he is not hiding the fact that the primary goal of this race is to hit a time. Specifically, the Olympic standard of 2:08:10. Only five Americans have ever bettered that time in history, but Fauble, who ran his personal best of 2:08:52 in Boston in 2022, believes he is capable of doing it.

“I don’t think that me running in the 2:07s is a huge stretch of the imagination,” said Fauble, who has removed some of the hillier routes from his training under coach Joe Bosshard but has otherwise prepared similarly for Berlin as he would Boston or New York. “I think I’ve been in that kind of shape a bunch of times.”

Every American marathoner will be rooting for Fauble

Currently, no male American marathoner has earned the 2024 Olympic standard — either by hitting the time standard of 2:08:10 or by finishing in the top five of a Platinum Label Marathon (which includes Berlin). It’s pvery likely someone such as Fauble or Conner Mantz will be ranked in the top 65 of the “Road to Paris” list at the end of January, but with the Olympic Trials less than five months away, US marathoners are getting antsy.

American pros rarely run the Berlin Marathon, typically opting for Chicago or New York in the fall — both of which pay much bigger appearance fees to American runners. But this fall, many are bypassing New York because of the date (just 13 weeks before the Trials) and the course (too slow for a shot at the Olympic standard). A sizeable crew, led by Mantz and Galen Rupp, will be in Chicago, while a far larger number than usual have opted for Berlin.

Berlin’s course is just as fast as Chicago’s, if not faster. It’s also two weeks before Chicago — an extra two weeks to prepare for the Trials — and the weather is typically a little better in Berlin than Chicago. That’s why Keira D’Amato opted for Berlin over Chicago for her American record attempt last year. It’s also why 60:02 half marathoner Teshome Mekonen — another American targeting the Olympic standard this fall — chose Berlin over Chicago.

In addition to Fauble and Mekonen, the 2023 Berlin field also includes 2016 Olympian Jared Ward, 2021 Olympian Jake Riley, and Tyler Pennel, who has finished 5th and 11th at the last two Olympic Marathon Trials. All of them will be looking to run fast. And every other American marathoner will be hoping they do the same.

That’s because of a new provision in the Olympic qualification system which states that any country with three qualified athletes may choose to send any three athletes it wants to Paris — as long as they have run at least 2:11:30 (men) or 2:29:30 (women) within the qualifying window. That’s why every American will be rooting for Fauble and others to run fast this fall: if the US has three athletes with the standard, then anyone who has run under 2:11:30 has the opportunity to make the team by finishing in the top three at the Trials.

The above provision, which World Athletics is referring to as “quota reallocation” means that someone such as Fauble could run the Olympic standard and open up a spot in Paris for an American athlete who ends up beating him at the Trials — thus taking a spot that would not otherwise be available had Fauble not run the standard. Fauble, obviously, is hoping such a scenario does not come to pass. But he is aware of the possibility and has accepted it as part of his reality.

“I don’t mind it,” Fauble said. “Sports have never really been about identifying the best team or the best athlete. They’re an entertainment product and they overemphasize very specific days on the calendar. Even if I was the only one with the standard and I get beat at the Trials, the 73-9 Warriors didn’t win the NBA title that year. You’ve gotta do it on the big days. That’s what being a professional athlete is about.”

by Jonathan Gault

Login to leave a comment

BMW Berlin Marathon

The story of the BERLIN-MARATHON is a story of the development of road running. When the first BERLIN-MARATHON was started on 13th October 1974 on a minor road next to the stadium of the organisers‘ club SC Charlottenburg Berlin 286 athletes had entered. The first winners were runners from Berlin: Günter Hallas (2:44:53), who still runs the BERLIN-MARATHON today, and...

more...Utah’s Clayton Young won the Crazy 8s 8K title on Saturday night

Utah’s Clayton Young bided his time until the last moment and made a strong move to win Saturday’s 33rd Ballad Health and Niswonger Children’s Hospital Crazy 8s 8-kilometer run on the candle-lit streets of the Model City.

With 200 meters to go, Young — the 2019 NCAA 10,000-meter champion from BYU — broke away from a group of six runners as he made his way into J. Fred Johnson Stadium to claim his second USATF title in 22:46 and the $5,000 that went along with the win.

There were nearly 3,200 finishers in Saturday’s races, including the Almost Crazy 3K, which was up almost 300 from last year.

“I was talking with my teammate Conner Mantz, who was runner-up last year and he said when he made his move, he felt like it wasn’t strong enough,” Young said. “He told me that I should be making that move before I turn up the hill. When I made my move, I was thinking about him and how he coached me through those final stages.”

Alberto Salazar’s American record of 22:04 lived another day. The start of the race was delayed by 45 minutes because of a strong thunderstorm that swept through the area.

“I had a lot of confidence going into this race,” Young said. “I’ve trained with Conner a lot and he’s had a great season, so that was a pretty good indicator. I just rode his coattails and went out there to see what I could do today.”

ZAP Endurance runner Andrew Colley was runner-up, finishing in 22:48. Oklahoma State graduate Isai Rodriguez took out the pace early and finished third in 22:49.

Young — who won the 2021 USATF 15K title in Jacksonville, Florida — trains with Mantz and now he’s got one up on his former BYU teammate.

“It’s finally nice to win another U.S. championship,” Young said. “You’ve got to celebrate all the victories, no matter how big or small they are. They keep you going and keep you motivated.

“To feel that strength over the last 800 meters was really validating and hopefully it’ll propel me through these next couple of races and into a fall marathon.”

Kingsport native Emma Russum — a member of Dobyns-Bennett’s 2019 state cross country state title team who now runs for Chattanooga — won the women’s division in 31:02.

It’s a dream come true of sorts for Russum, who’s regularly run the race since she was 6 years old.

“It feels really good to win and it’s even better because I got second last year,” Russum said. “I ran 20 seconds slower than last year, but it was super fun and I definitely was trying to keep a more relaxed effort at the beginning.

“People were yelling at me in the last bit that a girl was coming, so I had to kick it in. I love this race and I’ve been running it since I was big enough to run in (Little 8s).”

Russum made a little bit of area history as well, becoming the third local female runner to win the Crazy 8s title. She joined Johnson City’s Jenna Hutchins and Bristol, Virginia’s Stephanie Place.

“It’s really cool to be a part of such a short history of local winners,” Russum said.

by Tanner Cook

Login to leave a comment

Crazy 8s 8k Run

Run the World’s Fastest 8K on the world famous figure-8 course on beautiful candle-lit streets with a rousing finish inside J. Fred Johnson Stadium. Crazy 8s is home to womens’ 8-kilometer world record (Asmae Leghzaoui, 24:27.8, 2002), and held the men’s world record (Peter Githuka, 22:02.2, 1996), until it was broken in 2014. Crazy 8s wants that mens’ record back. ...

more...Kara Goucher’s Book Offers Rare Insight Into Elite Athlete Contracts

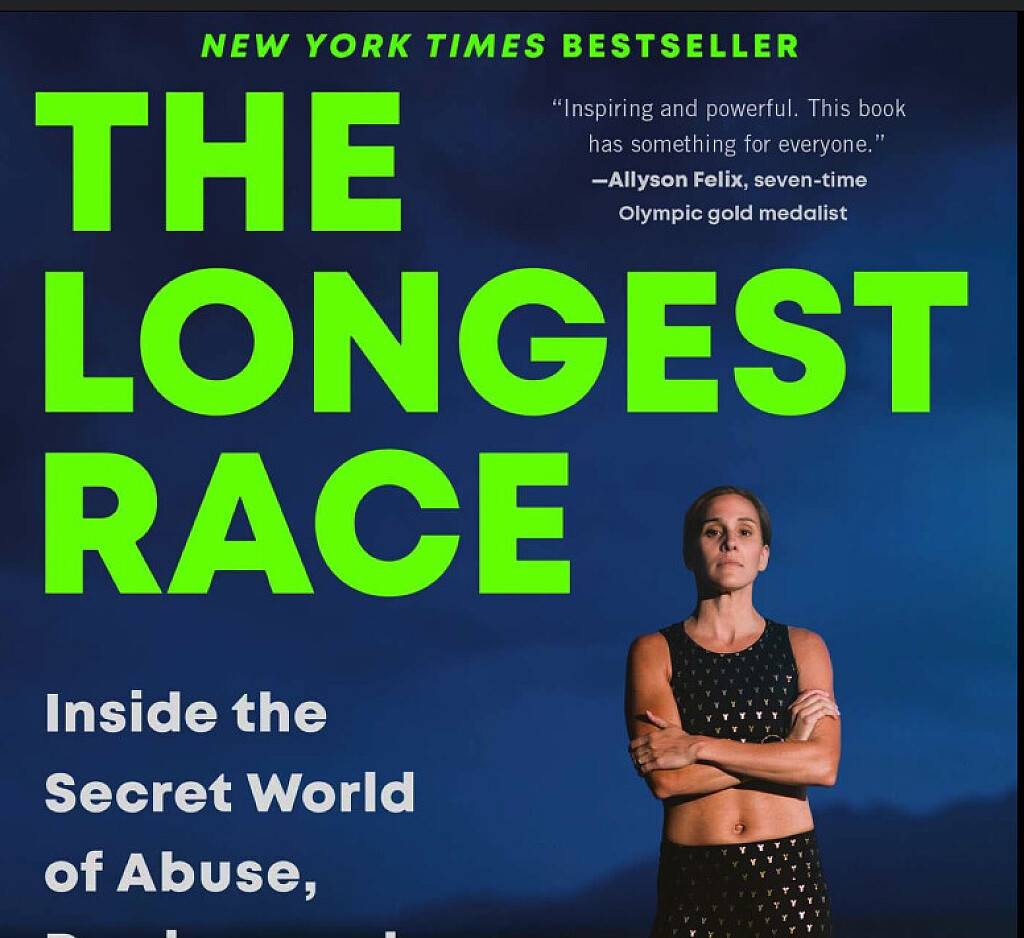

Confidentiality clauses usually stop runners from talking about their endorsement deals.Kara Goucher’s memoir about her career in professional running, The Longest Race, alleges shocking behavior by her longtime coach, Alberto Salazar, and how she overcame it. But a subplot throughout the book is how much money she was earning in the sport along the way.

Goucher is open about her contract with Nike and appearance fees at races, including the New York City Marathon, the Boston Marathon, and the Great North Run in the U.K. (Nike did not respond to an email from Runner’s World seeking comment.) Even though the deals are from 10 to 20 years ago, they provide an interesting look at the business side of professional running. It’s a rare peek, too, because sponsor contracts are bound by confidentiality clauses and, in many cases, those clauses extend beyond the term of the contract.

Goucher’s did, but she decided to reveal the information anyway—to be helpful to other athletes. “I just felt like it was very important to have those numbers in there,” she said in a phone call with Runner’s World. “How do you know what to ask for if you have no idea what anyone else is getting paid?” Here’s what we learned about Goucher’s pay and that of her husband, Adam Goucher, from the book:

In 2000, Adam Goucher was making a base payment of $50,000 from Fila, his first sponsor. In his first year, he ran so well that he earned $185,000 with bonuses. Goucher writes that the pay was a “welcome windfall that helped him pay off student loans.”

In 2001, Kara Goucher signed a four-year deal with Nike for $35,000 per year. This was her first professional contract after she graduated from the University of Colorado.

In 2003, Adam Goucher signed with Nike with a base pay of $90,000 per year. The Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamIn the fall of 2007, she ran the Great North Run, a half marathon in Newcastle, England. The race director paid her an appearance fee of $13,000 and made a deal with Goucher’s agent at the time, Peter Stubbs, to pay her $30,000 if she won. The money was “not far off the annual salary I had lived on for years,” Goucher wrote. She won the race.

In February 2008, Goucher signed a new Nike deal that paid her $325,000 per year for four years, with an option for Nike to extend to a fifth year. The contract included performance bonuses ranging from $10,000 to $500,000 for an Olympic gold medal. There were also reductions, which could cut her pay. She had to race 10 USATF-sanctioned events per year, and if she ended the year ranked lower than third in her event in the U.S. or out of the top 10 in the world, Nike could dock her pay.

Goucher told Runner’s World that, for her second shoe deal, she asked her agent to accept a commission of 8 percent for each year of the deal. The industry standard is 15 percent. He agreed. She continued to pay him 15 percent on her appearance fees and prize money. She also made sure that she was paid directly by Nike and then she paid her agent. (In most cases these days, the shoe company pays the agent, who then pays the athletes, because it’s less paperwork for the shoe company, having to deal with individual athletes.)

In November 2008, Goucher made her marathon debut at the New York City Marathon. She earned an appearance fee of $175,000. Nike also paid her bonuses paid on based on her place and time, but Goucher didn’t disclose those. She wrote, “One good marathon and I could easily walk away with more than my yearly contract salary.” In April 2009, Goucher ran the Boston Marathon, which, at the time, traditionally paid less in appearance fees to athletes than New York. (It is also the only major marathon in the U.S. in the spring.) Her appearance fee was $80,000, but when she learned another American, a male runner, was making $85,000, she asked the BAA to match that. Race organizers agreed.

In early 2010, Goucher learned she was pregnant with her son, Colt. Salazar confirmed with Nike executive John Capriotti on Goucher’s behalf that Goucher wouldn’t suffer a reduction in her pay as long as she remained “relevant,” she wrote. Her first of four quarterly payments from Nike arrived on time in January, as did her second in April. But in July, her accountant told her that her payment hadn’t arrived. Nor did her October payment.

This set off a lengthy battle between Goucher and Nike over money during her pregnancy. Ultimately, Nike docked her pay for six months and extended her contract to the end of 2013.

At the end of 2010, Adam Goucher’s contract with Nike ended.

In 2011, USA Track & Field (USATF) said it would be dropping the Gouchers’ health insurance, because her marathon ranking had dropped while she was pregnant. She appealed the decision, and the U.S. Olympic Committee stepped in and reinstated the health insurance. This rule has subsequently been changed—pregnant athletes can keep their health insurance—and today’s runners laud that change.

At the end of September 2011, Goucher left the Nike Oregon Project. She remained under contract with Nike and stayed in Portland, Oregon. Jerry Schumacher coached her, and she trained with Shalane Flanagan.

At the end of 2013, Goucher scrambled to race 10 times so Nike wouldn’t suspend her pay again. She ran a turkey trot to fulfill her obligations (and won a pie). Her contract with Nike ended at the end of the year, and she and Adam sold their house in Portland and moved to Boulder, Colorado.

In 2014, Goucher entertained contract offers from other companies, although Nike still had the option to match any offers. Saucony offered her $1 million total over 5 years, with bonuses and no reductions. Ultimately, she chose to sign with women’s clothing brand Oiselle for $20,000 per year, and a 2 percent stake in the company. She signed a separate deal for footwear with Skechers.

Today, Goucher encourages athletes to speak up and not be afraid to rock the boat, especially those who are lower-paid. She faults the secrecy around pay in track and field with creating difficult situations. It’s required to agree to the confidentiality clause in contracts in order to secure the deal, she said, and in some cases, that gives cover to companies that underpay talented athletes. The confidentiality clause “only harms the athlete and protects the brand,” she said. “Because then they can continue to pay you the least amount possible.”

Agent Hawi Keflezighi, who has never worked with Goucher, agreed with her assessment. “I think there are a lot of very bad contracts out there that footwear brands would probably be embarrassed to admit to,” he said. “There are some really bad deals out there that would probably create a backlash.”

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

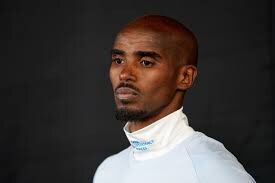

Mo Farah expects his final London Marathon to be emotional

Mo Farah expects there to be tears on Sunday when he runs the marathon in the city he calls home for one final time.

The four-time Olympic gold medallist turned 40 last month and has confirmed this weekend’s London Marathon will be his last race over that distance. He then plans to run in just two more events before he retires at the end of this year.

This will be Farah’s fourth marathon in the capital, after finishing eighth in 2014, third in 2018 – when he broke the British record - and fifth in 2019.

And he thinks it will be an emotional farewell in the city he was smuggled to from Somalia aged eight – and where he enjoyed his greatest glory by winning golds in the 5,000m and 10,000m at London 2012.

‘This is it. It will be my last marathon,’ said Farah in London on Thursday. ‘When you know it’s the end of the road, you always get emotional. I think it will get to me. Maybe after the race there will be tears.