Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #Mary Cain

Today's Running News

Jane Hedengren’s Historic 5K Was Just the Beginning of a Record-Breaking Spring

On April 17, 2025, Jane Hedengren made U.S. high school history by becoming the first American high school girl to run under 15 minutes for the 5,000 meters, clocking an astonishing 14:57.93 at the Bryan Clay Invitational in Azusa, California. Now, over a month later, the running world is still feeling the shockwaves of her performance—and she’s not done yet.

The senior from Timpview High School in Utah led much of the race against top collegiate and pro runners. Despite being passed in the final stretch, Hedengren finished third overall, showing poise, power, and world-class pacing. Only New Mexico’s Pamela Kosgei (14:52.45) and future BYU teammate Lexy Halladay-Lowry (14:52.93) crossed the line ahead of her.

Prior to that, on April 12, Hedengren broke the U.S. high school girls’ outdoor two-mile record with a 9:34.12 effort at the Arcadia Invitational. That time eclipsed the previous record of 9:41.76 and underscored her extraordinary range—from the mile to 5K, Jane is dominating every step of the way.

What She’s Done Since

While May has been a quieter race month for Jane, she’s been focused on tuning up for a big June. According to her coach and recent interviews, Hedengren has been training at altitude in Utah, sharpening her speed with race-pace workouts and eyeing her final high school meets before transitioning to BYU.

She’s scheduled to compete at the HOKA Festival of Miles on June 5 in St. Louis, one of the most prestigious high school mile events in the country. There, she could challenge her own national mile record (4:26.14, set indoors in March) or even take aim at Mary Cain’s 4:24.11 outdoor mark from 2013.

A Season of Dominance

Here’s a look at what Hedengren has accomplished in just the last few months:

• March 2025 – Broke U.S. high school indoor records in both the mile (4:26.14) and 5,000m (15:13.26) at the Nike Indoor Nationals.

• April 12, 2025 – Set a new national 2-mile record of 9:34.12 at Arcadia Invitational.

• April 17, 2025 – Ran 14:57.93 for 5,000m at the Bryan Clay Invitational, becoming the first U.S. high school girl to break 15 minutes.

• June 5, 2025 (upcoming) – Scheduled to race the mile at HOKA Festival of Miles.

What’s Next?

With a spot secured at BYU and a history-making senior year already behind her, Jane Hedengren is setting herself up not just as one of the greatest U.S. high school distance runners of all time—but as a potential future Olympian. All eyes will be on St. Louis in June, and beyond that, the U.S. Junior Championships and her NCAA debut could come sooner than expected.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Sadie Engelhardt: Rising Star Shines with Historic Indoor Mile Performance

On February 2, 2025, at the New Balance Indoor Grand Prix in Boston, Sadie Engelhardt, a senior from Ventura High School in California, delivered a remarkable performance by completing the mile in 4:29.34. This achievement ranks as the second-fastest indoor mile in U.S. high school history, trailing only Mary Cain's 2013 record of 4:28.25.

Engelhardt's journey in track and field began in elementary school, where she participated in cross country at Poinsettia Elementary in Ventura. Initially, running served as conditioning for her primary passion, soccer. However, by eighth grade, after clocking a 4:40 mile, she recognized her exceptional talent and shifted her focus to track.

Throughout her tenure at Ventura High School, Engelhardt has consistently broken records and garnered accolades. In 2022, she became the California State Champion and set an all-time record in the 1600 meters at the Arcadia Invitational. The following year, she achieved a historic double at the CIF State Track and Field Championships in Clovis, winning both the 1600-meter and 800-meter events. Notably, she set a meet record in the 1600 meters with a time of 4:33.45, a feat last accomplished in 1975.

Academically, Engelhardt has maintained a weighted 4.59 GPA and has committed to competing on scholarship at North Carolina State University starting in the fall of 2025.

Reflecting on her recent performance, Engelhardt emphasized the importance of enjoying the journey, stating, "I'm still in high school, so this is like the fun part before it gets really serious in college and (at the) professional level, so just doing my best."

Engelhardt's blend of academic excellence, athletic prowess, and grounded perspective underscores her as a standout figure in high school athletics. As she continues to break barriers, the track and field community eagerly anticipates her future endeavors.

Login to leave a comment

High school girls are clocking some very fast miles this season

Never before has a national high school record been broken in back-to-back races.

Well, until Thursday May 30.

Just 10 minutes separated two historic efforts at the mile distance between high school girls at the Festival of Miles in St. Louis, Missouri, with Virginia native Allie Zealand getting things started under the lights with a time of 4:30.38.

However, it wasn't long before Ventura junior Sadie Engelhardt, whose own national record of 4:31.72 was broken by Zealand, got her own crack at it in the women's professional mile that followed.

Roughly 10 minutes later.

Engelhardt's patience was played to perfection, as she bided her time in the pack before working her way up over the last 200 meters and hitting for a 63-second final lap to score a new national record in 4:28.46.

Her finish only paled Jenn Randall's winning time of 4:28.23.

Engelhardt's performance was just 0.21 seconds shy of Mary Cain's longstanding overall national record of 4:28.25, which was set indoors in 2013.

Engelhardt put together laps of 68.9 over 409 meters, 68 seconds over the second 400 meter frame, 68.3 in the third quarter and 63.2 in the closing lap.

Zealand, meanwhile, went 69.23, 68.94, 67.38 and 64.81. Cuthbertson's Charlotte Bell was second in 4:35.70 while Allison Ince was third in 4:35.96.

Five girls finished under 4:40 and six more were under 4:50.

Login to leave a comment

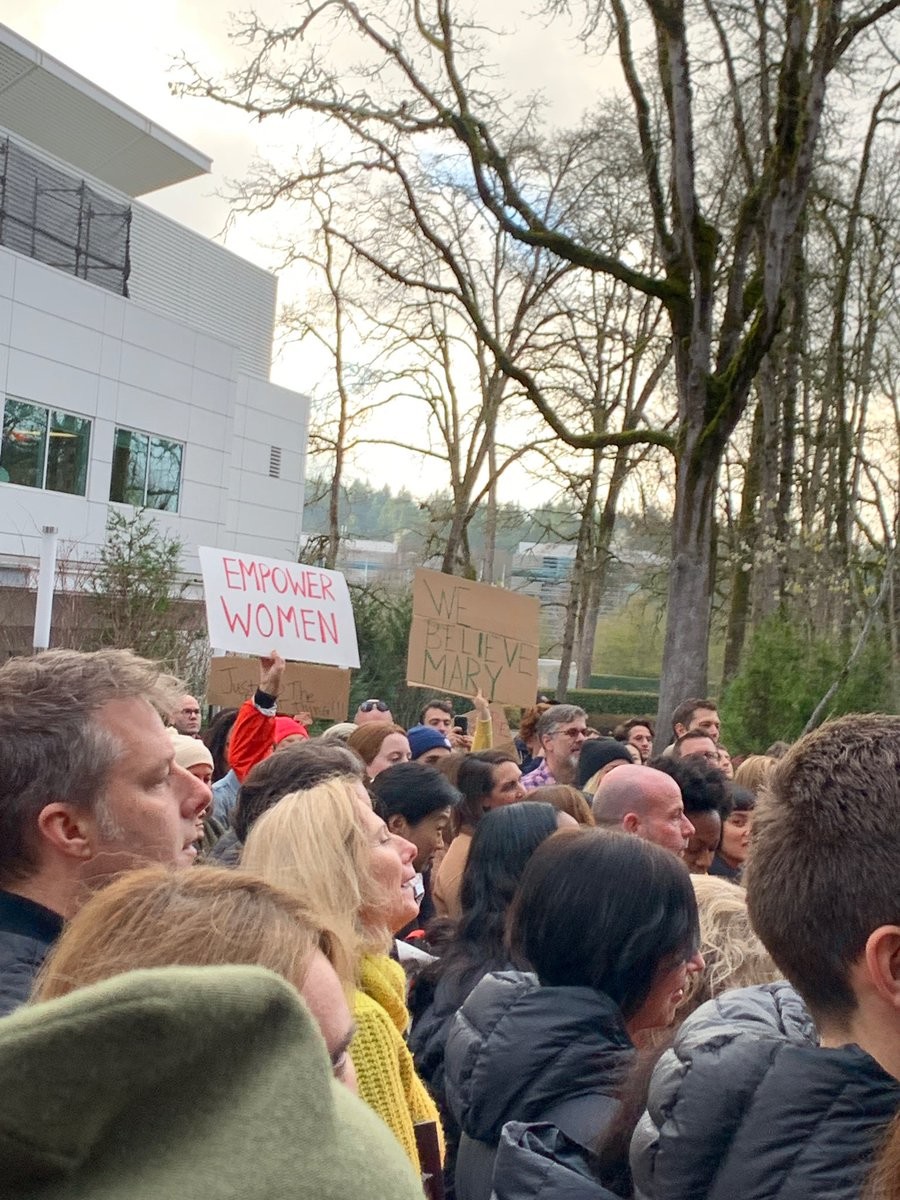

Nike and Alberto Salazar settle $20 million lawsuit with Mary Cain over alleged abuse

On Monday, Nike, disgraced coach Alberto Salazar and distance runner Mary Cain reached a settlement in the $20 million lawsuit filed by Cain, as reported by The Oregonian.

The lawsuit accused Salazar of emotional and physical abuse towards Cain and highlighted Nike’s alleged failure to provide adequate oversight during her time with Salazar. Cain, who ran for Nike’s Oregon Project from 2012 to 2016, spoke out in 2019 about abuse within the program, exposing broader cultural issues at Nike, including a reported “boys’ club” atmosphere.

Salazar, once celebrated for coaching Olympic medallists Mo Farah, Galen Rupp and Matt Centrowitz, faced a permanent ban from working with U.S. track and field by U.S. SafeSport for alleged sexual assault and a doping scandal. Nike disbanded the Oregon Project in 2019, and Salazar’s name was removed from a building on the company’s campus following the ban.

Cain’s allegations against Salazar included controlling behavior, inappropriate comments about her body and humiliating practices, which led to depression, an eating disorder and self-harm. Nike was implicated in the lawsuit for allegedly not taking sufficient action to protect Cain, a sponsored athlete. Salazar denied the allegations, emphasizing his commitment to athletes’ well-being. Cain filed the $20 million lawsuit in 2021.

Numerous runners have come out and criticized Nike for its lack of support for female athletes. In 2018, U.S. Olympian Allyson Felix called out the brand for allegedly asking her to take a 70 per cent pay cut during her pregnancy, prompting Felix to leave Nike and join the female-powered brand Athleta before the Tokyo Olympics.

by Marley Dickinson

Login to leave a comment

Sophia Kennedy, Daughter Of Bob Kennedy, Looks For Steady Progress As She Prepares For Two National Meets

INDIANAPOLIS – As far as she is concerned, Dad is Dad. But every once in a while, Sophia Kennedy’s father comes up in conversation.

“Oh yeah, my dad ran professionally,” she says.

“Who’s your dad?”

“Bob Kennedy.”

After the oh-my-gosh replies, Sophia can’t help but smile.

“That always feels kind of cool.”

Also cool: Sophia Kennedy has qualified for both high school nationals in cross country, the Nike race Saturday at Portland, Ore., and Champs Sports (formerly Foot Locker and Eastbay) on Dec. 10 at San Diego. She is a senior at Park Tudor School in Indianapolis and has committed to Stanford.

For an American distance runner, being Bob Kennedy’s daughter is analogous to being an Obama sister entering politics or an actress whose father is Brad Pitt. Comparisons are inevitable, and inevitably unfair.

Yet by now, 52-year-old father and 17-year-old daughter are so used to it, it is a source of amusement rather than pressure. No one will be another Bob Kennedy. His impact on track and field cannot be overstated.

The two-time Olympian won four NCAA titles while at Indiana University and became the first non-African to run 5,000 meters in less than 13 minutes. His 1998 American record at 3,000 meters, 7:30.84, has been lowered little (to 7:28.48 by Grant Fisher) despite a 24-year span and introduction of super-shoes.

Sophia did not have to follow in those spikesprints. Her twin brother, Marcus, is a soccer standout. No way Sophia was going that route. She was once a goalkeeper “because I was a liability on the soccer field.”

Sophia took ballet lessons, played the clarinet. Her mother, Melina, a former IU runner who once ran for mayor of Indianapolis, and father encouraged the twins to try everything.

“Ultimately, they choose their own passion,” the father said. “We were big on hopefully finding something. Because I think it’s important to life and growth to find something that interests you, whether you’re the best at it or just really enjoy it.”

For Sophia, that became running. She was among the best and really enjoyed it.

Her transformational moment came when she nearly won a two-mile race around school grounds as a fifth-grader. She was outkicked by a boy. Then “it was on,” her father said.

Sophia affiliated with a local club, the Carmel Distance Project, and began winning races. In age-group cross-country nationals, she was 32nd in 2016 and 11th in 2017.

She didn’t have to travel far for competition, either. The Kennedy and Farley families used to live on Pennsylvania Street in Indianapolis homes separated by 73rd Street. Sophia grew up playing with a future Park Tudor teammate, Gretchen Farley, who has also qualified for San Diego.

Bob Kennedy has characterized Farley, a 2:09/4:50 runner who competes in four sports, as “a super talent.”

Sophia said all her parents have ever asked is whatever she does, give it her all.

“My parents have made it super clear, if I’m ever not happy in the sport, I don’t have to keep running,” she said. “It’s just something I’ve come to love because I love the hard work and the opportunities that it brings and the people that I meet.”

Sophia’s progress has not gone uninterrupted.

After setting an Indiana indoor 3,200-meter record of 10:12.32 last Feb. 19, she developed a fever, then an injury. She tried to maintain fitness via cross-training and anti-gravity treadmill. In May, when she began state track qualifications in a sectional, it was her first running on the ground in six weeks.

Given all that, it was redemptive to finish second at state in 10:25.02, or two seconds behind champion Nicki Southerland. Sophia lowered that to a 10:20.13 two-mile in finishing eighth at the Brooks PR Invitational.

Sophia took a measured approach to this cross-country season. Her father has credited her high school coaches, Garrett Lawton and Ryan Ritz, with prioritizing long-term future over short-term success. Sophia does not exceed 40 miles a week, and sometimes runs as few as 30.

“The one thing I realized,” she said, “if I want to be successful, I need to be healthy this year.”

That has been manifested in what is arguably her best run of runs. In a span of six 5Ks over eight weeks – none of which she won – she clocked 17:10, 17:12, 17:25, 17:24, 17:11, 17:23. She was third at state, fifth at NXR Midwest and second at Champs Midwest.

Even her cautious father conceded the daughter is on a trajectory that will accelerate as her strength matches her aerobic capacity. Sophia’s VO2 max is 82. Bob Kennedy’s was 83.

“I’m a little biased. I think you’re going to see huge leaps,” he said.

Sophia has come along during an unprecedented era in Indiana. Not only did Addy Wiley set a national record for 1,600 meters last June, there have been opponents such as Lily Cridge, Southerland, Addison Knoblauch and Farley.

According to inccstats.com, Cridge, Southerland and Kennedy rank Nos. 1, 4 and 5, respectively, in Indiana cross-country over the past 40 years.

Sophia is not intimidated at national meets. She sees such competition regularly. At San Diego last December, she led through a 5:19 mile and finished seventh.

She became the first Indiana girl in 15 years to have four top-five finishes at state cross-country . . . but never has she been a state champion on grass or track.

“She’s generationally great, and hasn’t won one yet. That’s stunning to me,” said Scott Lidskin, who coached Westfield to four state titles in girls cross-country.

Sophia will be surrounded by talent at Stanford. She chose the Farm over Notre Dame, North Carolina State, Virginia and Colorado.

Stanford was 13th in NCAA cross-country with a roster of six sophomores and one freshman. The team did not include two 1:59 freshmen, Roisin Willis and Juliette Whittaker, who won gold and bronze medals in the 800 meters at the World Under-20 Championships. Nor did it include Irene Riggs, a 2023 recruit coming off a 16:02 that was the second-fastest 5K in high school cross country history.

Sophia Kennedy, taking cues from her parents, pleads patience.

“I don’t want to be just a really good freshman,” she said. “I want to be really good in four years and five years and 10 years.”

It is mildly disappointing to be without a state title in Indiana’s single-class system. To win state at 3,200 meters, for instance, she suggested it might take 9:50 to beat Cridge (10:03.16 PB) and win.

No high school girl has broken 9:50 in an outdoor two-mile. Three have done so indoors: Mary Cain, Natalie Cook, Sydney Thorvaldson.

“I’m not looking for these immediate responses in my high school career,” Sophia said. “I want to run better at Nike nationals than I would have at the state meet. I want to be strong for the spring and not get injured.”

And not get caught up in what Dad did, other than to have a long career in the long run.

by Runner’s Space

Login to leave a comment

Whittaker repeats as mile champion in Seattle by edging Engelhardt and elevates to No. 7 all-time outdoor performer with 4:36.23 effort in first girls high school race with seven athletes running under 4:40

Julia Flynn called it.

“I knew it. I knew today was going to be a crazy race,” said Flynn, a recent graduate of Traverse City Central High in Michigan.

That it was. On a cloudy Wednesday afternoon at the University of Washington’s Husky Stadium in Seattle, Flynn was part of the fastest Brooks PR Invitational mile in meet history.

Defending champion Juliette Whittaker of Mount de Sales in Maryland led the charge with a final surge down the straightaway to win in 4 minutes, 36.23 seconds, lowering her own meet record of 4:38.65 from last year.

Six girls quickly followed, all crossing the finish line under 4:40 to make it the deepest girls mile race in U.S. prep history. The boys mile also didn’t disappoint to cap the meet by having junior Simeon Birnbaum of Rapid City Stevens High in South Dakota eclipse the 4-minute barrier and five athletes run sub-4:02 for the first time in a single high school race.

“I predicted Juliette was going to win, but I was like, ‘You know what? Regardless of the winner, we’re all going to get really big PRs,’” Flynn said. “That’s why it’s Brooks PR, it lives up to the name.”

With the girls and boys miles scheduled annually as the last races of the meet, fans at Husky Stadium lined the outskirts of the track down the straightaway, creating an intimate and electric environment for the 12 female runners all capable of winning the event.

“I knew it was going to be a fast race and I knew it was going to be competitive,” Whittaker said. “Just the fact that we came around with a lap to go and all of us were still in the race, was insane, it was really just a kick to the finish.”

With a slight separation from the pack, Whittaker and freshman Sadie Engelhardt of Ventura High in California – who set an age 15 world mile record April 9 by running 4:35.16 at the Arcadia Invitational – came sprinting down the last 100 meters.

Similar to how the New Balance Indoor National mile championship race played out March 13 between the two athletes, Whittaker had a little more left in her to pull ahead of Engelhardt for the victory. Whittaker prevailed by a 4:37.23 to 4:37.40 margin at The Armory in New York.

Engelhardt finished runner-up Wednesday in 4:36.50, while Flynn ran 4:37.73 to set a Michigan state record by eclipsing the 2013 standard of 4:40.48 produced by Hannah Meier of Grosse Pointe South.

Riley Stewart of Cherry Creek High was fourth in 4:38.21, lowering her own Colorado state record of 4:40.66 from last year, when she placed second behind Whittaker.

“I’m feeling amazing,” Stewart said. “I’ve been 4:40 three times now, so to finally get it (under 4:40) and to run with all these amazing girls, I have to say that was probably one of the best miles we’ve ever seen come through here, so just to be part of it is just amazing.”

Samantha McDonnell of Newbury Park High in California placed fifth in 4:38.44, Isabel Conde de Frankenberg of Cedar Park High was sixth in a Texas state record 4:38.55, and Mia Cochran from Moon Area in Pennsylvania secured seventh in 4:39.23. Conde de Frankenberg eclipsed the 2009 standard of 4:40.24 established by Chelsey Sveinsson of Greenhill High.

Every performance achieved from Engelhardt to Cochran was the fastest all-time mark by place in any high school girls mile competition.

Just missing going under 4:40 was Taylor Rohatinsky of Lone Peak High in Utah, clocking 4:41.83 to also produce the fastest eighth-place performance in any outdoor prep mile race.

Whittaker’s winning effort made her the No. 7 outdoor competitor in U.S. prep history, with three of the marks achieved this year, the other two coming from Dalia Frias of Mira Costa High in California (4:35.06) – who also ran the national high school outdoor 2-mile record 9:50.70 to open Wednesday’s meet – and Engelhardt’s victory at Arcadia.

Whittaker, along with Flynn, Stewart, 10th-place finisher Ava Parekh (4:52.09) of Latin School in Chicago and Roisin Willis from Stevens Point in Wisconsin – second place Wednesday in the 400 in 53.23 – are all part of Stanford’s 2022 recruiting class.

Despite having an unusual high school career due to the pandemic, Whittaker said the surge of quicker times and a more competitive environment may be due to the circumstances the pandemic created with more time for training.

“I feel like ever since COVID, honestly we have just surpassed any goals that we used to always set,” Whittaker said. “(Running) 4:40 used to be a barrier that like many people wanted to break, if so, maybe one, but the fact that seven girls (did) in the same race. I’m excited for years to come to keep watching. Sadie, obviously only being a freshman, and like other girls, I’m excited to see what times they are going to run.”

Here is the list of high school girls who have broken 4:40 before this race:

High School Girls Who Have Run Sub-4:40 Miles

Mary Cain — 4:28.25i (2013)

Alexa Efraimson — 4:32.15i (2014)

Katelyn Tuohy — 4:33.87 (2018)

Dalia Frias — 4:35.06 (2022)

Sadie Engelhardt — 4:35.16 (2022)

Polly Plumer — 4:35.24 (1982)

Katie Rainsberger — 4:36.61i (2016)

Kim Gallagher — 4:36.94 (1982)

Sarah Bowman — 4:36.95 (2005)

Arianna Lambie — 4:37.23 (2003)

Juliette Whittaker — 4:37.23i (2022)

Marlee Starliper — 4:37.76i (2020)

Christina Aragon —4:37.91 (2015)

Addy Wiley — 4:38.14 (2021)

Victoria Starcher — 4:38.19 (2020)

Caitlin Collier — 4:38.48 (2018)

Debbie Heald — 4:38.5i (1972)

Ryen Frazier — 4:38.59 (2015)

Taryn Parks — 4:39.05i (2019)

Wesley Frazier — 4:39.17 (2013)

Sarah Feeny — 4:39.23 (2014)

Danielle Toro — 4:39.25 (2007)

Mia Barnett — 4:39.41 (2021)

Katelynne Hart — 4:39.57 (2020)

Cami Chapus — 4:39.64 (2012)

Brie Felnagle — 4:39.71 (2005)

Dani Jones — 4:39.88 (2015)

Angel Piccirillo — 4:39.94 (2012)

Allison Cash — 4:39.98 (2013)

by Mary Albl of DyeStat

Login to leave a comment

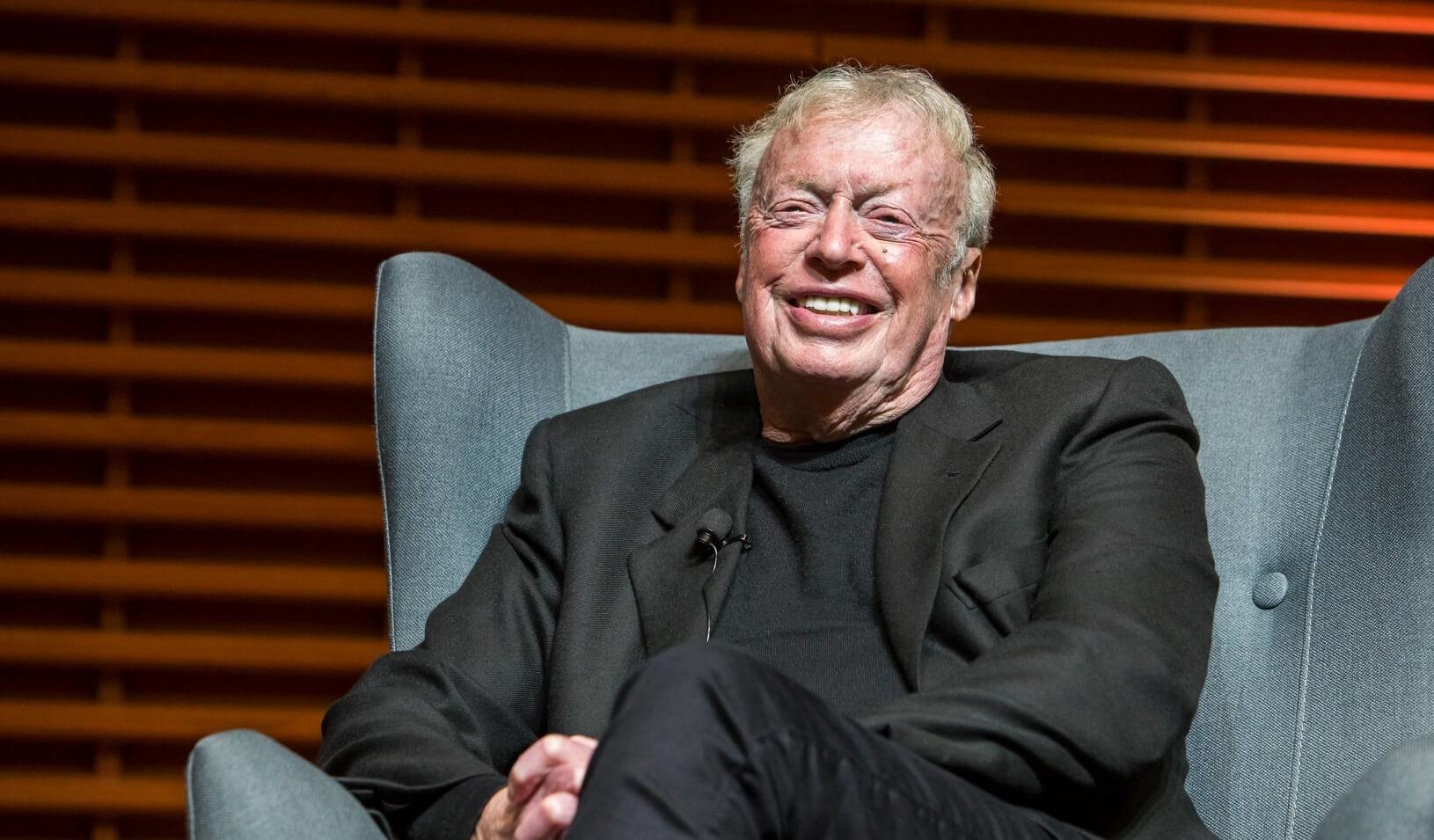

Alberto Salazar’s permanent ban from SafeSport was for alleged sexual assault, new report finds

Just last month, former Nike Oregon Project coach Alberto Salazar had his permanent ban from the sport upheld by the U.S. Center for SafeSport. A new report from the New York Times on Monday revealed it was because an arbitrator found that he more likely than not had sexually assaulted an athlete on two different occasions.

The famed running coach Alberto Salazar, who helped top Americans be more competitive in track and field before he was suspended for doping violations, was barred from the sport for life last month after an arbitrator found that he more likely than not had sexually assaulted an athlete on two different occasions, according to a summary of the ruling reviewed by The New York Times.

The case against Salazar was pursued by the United States Center for SafeSport, an organization that investigates reports of abuse within Olympic sports. SafeSport ruled Salazar permanently ineligible in July 2021, finding that he had committed four violations, which included two instances of penetrating a runner with a finger while giving an athletic massage.

Salazar asked for an arbitration hearing, where he denied the accusations and said he did not speak with or see the runner on the days in question. The arbitrator did not find Salazar’s explanation credible, and accepted his accuser’s version of events.

The details of the ruling, which have not been reported until now, shed new light on why Salazar, a powerful figure within elite running, was specifically barred from his sport. A number of runners have publicly accused him of bullying and behavior that was verbally and emotionally abusive, but the accusations of physical assault had not been publicly revealed. Salazar has never been criminally charged in connection with these allegations.

SafeSport, an independent nonprofit organization in Denver that responds to reports of misconduct within the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic sports, pursued action against Salazar and ruled him permanently ineligible in July 2021.

They currently list Salazar’s misconduct on their database as “sexual misconduct,” though the specific allegations against the coach were not known because they do not release details of its rulings. The report from The Times reveals new details on why the famed running coach Salazar was banned. Until now, the details were unknown.

Salazar has been accused of making comments about teammates’ bodies and weight in the past, but accusations of physical assault had not been publicly revealed. He has not been criminally charged with these allegations.

Numerous athletes have spoken out against Salazar for conduct against women. In November 2019, former high school star Mary Cain, who trained under Salazar from 2013 to 2015, spoke out about years of emotional abuse as a member of the Nike Oregon Project.

After Cain’s public comments, several other members of the project spoke out and shared their own experiences under Salazar.

Salazar, 63, has denied all allegations. In an email to The Times, he said he “never engaged in any sort of inappropriate sexual contact or sexual misconduct.”

Salazar also told The Times that the SafeSports process was “unfair” and “lacked due process protections.”

The United States Anti-Doping Agency also banned Salazar, along with Dr. Jeffrey Brown in September 2019 for four years. Although no athlete training under Salazar tested positive for a banned substance, the USADA determined Salazar tampered with the doping control process and trafficked banned performance-enhancing substances.

Salazar also denied those allegations and appealed that ban. His appeal was denied in September.

by NY Times and OregonLive

Login to leave a comment

Oregon Ducks athletic programs no longer can monitor athletes’ weight, body fat percentage

The University of Oregon strengthened protocols in late October to prohibit athletic programs from requiring athletes to be tested for body fat percentage.

According to the revised written protocols, athletes can choose to be tested. But results of the test “should not be reported beyond the student-athlete, dietitian and relevant medical personnel. Reporting of individual results to coaches is not permitted.”

The move came in apparent response to an Oct. 25 story from The Oregonian/OregonLive in which six former women track athletes accused the track program of emphasizing and tracking weight and body fat percentage to the point it led to eating disorders.

The athletes alleged UO coach Robert Johnson’s program required athletes to undergo regular DEXA scans to precisely measure their body fat percentages, then pushed them to lower those percentages.

She told the publication she believes the dietary restrictions led to an injury-plagued sophomore season.

In a story appearing Tuesday in the British newspaper The Telegraph, former Oregon distance runner Philippa Bowden said she was told to drop weight even after confiding she previously had battled an eating disorder.

She said she eventually withdrew from school in 2019 after beginning to purge in an effort to keep her weight low.

UO spokesperson Jimmy Stanton said the athletic department recommended in fall 2020 that coaches stop emphasizing weights and body fat percentage in training. That recommendation is now a requirement.

The recently revised protocol further states: “Coaches must be careful never to suggest or require changes in weight or body composition.”

Johnson has guided the Ducks to 14 national championships in cross country, indoor and outdoor track, cementing Oregon’s position as one of the elite programs in college track and field.

That was followed up in an Oct. 29 story in Runner’s World in which former UO distance runner Katie Rainsberger made similar allegations.

Rainsberger told Runner’s World she was encouraged to drop her body fat percentage and weight even though a nutritionist with the program knew she no longer was getting her menstrual period.

He outlined his training philosophy to The Oregonian/OregonLive in early October. It put a heavy emphasis on using advanced technological tools such as blood tests, hydration tests and DEXA scans to track athletes’ body composition.

Johnson did not respond to interview requests for this story.

A DEXA scan is a medical imaging test that uses X-rays to precisely measure bone density, muscle mass and body fat percentage.

Athletes said they believe Johnson and other coaches always knew the test results revealing their body fat percentages.

Even before DEXA scan technology became available to Oregon in recent years, Johnson’s program measured athletes’ body fat with skinfold caliper tests.

A former UO employee who worked with the athletic department dietitians, helped measure body composition with skinfold calipers from 2014-16. Results of the tests were tracked on a spreadsheet.

“In my experience, the coaches always had access to athletes’ body composition,” the former employee says.

The employee — who still works in the field and did not want be identified for fear it would restrict future employment opportunities — became concerned about Johnson’s reliance on body fat percentage as a training tool.

“I had athletes express to me a feeling like they needed to be compliant with coaches’ wishes in order to maintain their scholarships and be able to compete in the important races,” the former employee said.

The former employee said at one point, Johnson and sprint coach Curtis Taylor wanted athletes to severely restrict their consumption of carbohydrates to facilitate weight loss.

“Obviously, that is not a diet backed by science,” the former employee said. “I spoke with athletes about this and explained it’s not backed by science. It’s not appropriate. Carbohydrates are important for athletes.

“I remember an athlete saying, ‘I hear you. I believe you. I know you’re right. But at the end of the day, Coach Johnson decides who competes. So, I have to do this.’”

At one point, the former employee said, Johnson called out the employee and a mid-distance runner in front of the team during a training session inside the Moshofsky Center, the school’s indoor practice facility.

“He pointed at her and started making accusations at me, saying I wasn’t doing my job to help her lose weight,” the former employee said. “He never was responsive to my attempts to clarify the nature of body composition and how it relates to athletic performance.”

Former UO high jumper Ashlyn Hare said she and other athletes discussed the track team’s approach to weight and body composition with Johnson in the wake of similar accusations made in 2019 by professional runner Mary Cain against Nike Oregon Project coach Alberto Salazar.

Hare said Johnson listened to the athletes over the course of several weeks. Eventually, though, she received a text message from him containing a link to an article in which a former professional runner defended the value of tracking weight and body fat percentage.

“After that it was conversation closed,” Hare said in a text message to The Oregonian/OregonLive. “He had received confirmation of his bias. He didn’t need to hear any more.”

Hare, who competed for the Ducks from 2016-19, said athletes during her time always believed DEXA scans were mandatory for athletes.

She shared a text exchange from a UO dietitian during her time at Oregon reminding Hare she hadn’t undergone her DEXA scan.

“I was told by our athletic trainer that I didn’t need to do the DEXA because I was not training and about to have surgery,” Hare said in a text message. “But I was told I had to anyway.”

NEW UO PROTOCOLS

Assessment of bone density and body composition (DEXA) relates to highly sensitive personal information and belongs to the student-athlete.

All student-athletes should receive annual education about how this information can support their performance and they should have the optionto participate.

In order to protect the student-athlete and the coach, data should not be shared or reported beyond the student-athlete, dietician, and relevant medical personnel. Reporting of individual results to coaches is not permitted.

Body image and disordered eating pose serious physical and psychological risks to student-athletes, and our primary goal is to support a healthy mind and body.

High risk sports should receive annual education about the prevalence, risks, and warning signs of disordered eating.

High risk sports should complete annual assessment for disordered eating risk factors.

At risk individuals should enter an interdisciplinary support model that includes dietetics, athletic medicine, and mental health services.

The focus of nutrition should be on the development of healthy habits that support performance — hydration, fueling, recovery.

Any changes in weight and body composition should be initiated and motivated by the student athlete under the guidance of a dietician.

Coaches must be careful never to suggest or require changes in weight or body composition.

by Oregon Live

Login to leave a comment

Women athletes allege body shaming within Oregon Ducks track and field program

Six women athletes who left the University of Oregon track and field program in recent seasons say they felt devalued as individuals and at risk for eating disorders because of the program’s data-driven approach to their weight and body fat percentages.

Five of the women departed with remaining eligibility.

One said she began binge-eating while at Oregon. Another says she struggles with body dysmorphia and has nightmares about competing at Hayward Field, Oregon’s iconic track stadium, while UO coaches stare at her and say: “You’re never going to be good enough.”

Robert Johnson, who became UO’s track and field and cross country head coach in 2012, has guided the Ducks to 14 NCAA championships while elevating what already had been one of the sport’s premier college programs.

Under Johnson the Ducks increasingly have embraced expensive and advanced technological tools such as blood tests, hydration tests and DEXA scans. A DEXA scan is a medical imaging test that uses X-rays to precisely measure bone density and body fat percentage.

DEXA scans, in particular, have become a flashpoint for some athletes, who say the precise body fat percentage measurements can trigger unhealthy behaviors.

Johnson contends his scientific approach largely removes human bias from judgments about athletes and allows the UO coaching staff to design workouts precisely tailored to each athlete’s needs.

“Track is nothing but numbers,” he says. “A good mathematician probably could be a good track coach.”

He says UO athletes receive DEXA scans in the fall, winter and spring, and no more often because of radiation emitted during the tests.

“When we get the numbers from our DEXA scans, we have an Excel spreadsheet that we can plug the numbers into, hit a button and it gives us a starting value for a training program.” he says. “It allows us to be cutting edge and innovative in our approach to performance.”

Some athletes contend this innovation comes at a staggering personal price.

An athlete who graduated from Oregon at the end of the 2020 school year emailed UO deputy athletic director Lisa Peterson, senior women’s administrator, in October 2020.

In the email she says she had been receiving text messages and Snapchats that fall from former teammates so worried about upcoming DEXA scans they were starving themselves.

She tells Peterson in the email: “I have seen and experienced an absolutely disgusting amount of disordered eating on the women’s track team, all because the coaches believe body fat percentage is a key performance indicator.

“We are not professional athletes. We do not have access to a bounty of organic food. We do not have unlimited time to cook. We cannot plan our days around our nutrition, and we are not the 30-year-old Olympians that coach Johnson seeks to compare our body fat percentage to.

“While knowing body composition may be helpful for some athletes, I have seen it be nothing but destructive.”

The athlete says Peterson responded by thanking her for the email and saying she had passed it on and said that Peterson thought the allegations would be investigated. A public records request did not turn up a report of an internal investigation.

“A BIG, BIG ISSUE”

The issues of weight-shaming, body image and body fat percentage testing have become more common in recent years. Longtime Washington track coach Greg Metcalf lost his job in 2018 after accusations of body-shaming and verbally abusive treatment of female athletes. Former Nike Oregon Project star Mary Cain and other women who competed for the NOP have made similar accusations about former coach Alberto Salazar.

Five former UO athletes consented to extensive interviews on the condition their names not be used for several reasons. Among them:

• Oregon is one of the most nationally prominent college track and field programs.

• The school has a cozy relationship with Nike, which underwrites the funding for USA Track & Field and sponsors a high percentage of professional track athletes.

• Oregon’s Hayward Field, largely built with money donated by Nike co-founder Phil Knight, is the host of the Prefontaine Classic professional meet, the semi-permanent host of the NCAA Outdoor Track & Field Championships, next year’s USATF Outdoor Championships and the 2022 World Outdoor Championships.

One athlete says Johnson “is such a terrifyingly powerful man. There are people who would lose their ability to go to the Pre Classic or lose USATF funding, because speaking up against him is like speaking up against basically USA Track & Field.”

One athlete says when she was given her first DEXA scan at Oregon, she already had not had a menstrual period in a year and a half. She says the nutritionist knew that.

The scan showed her body fat percentage at 16%. She was told by the nutritionist she should consider lowering it to about 13%. And while the suggestion came from the nutritionist, she is certain the message originated with the coaching staff.

“They always were talking together,” she says.

The university did not make available a nutritionist or nutritionists in response to a formal interview request.

The athlete consulted her personal doctor, who advised her not to try to lower her body fat percentage any further. The American Council on Exercise suggests an ideal body fat percentage for a female athlete to between 14% and 20%.

“He said I already was in a situation that was dangerous for my body and that I needed to make sure I got my period back,” she says.

After that, she says, she struggled mentally.

“I started worrying a lot about what I was eating,” she says. “I wanted to make sure I wasn’t going to get too much bigger of a percentage. That was like a big, big issue.”

She was very careful during the day. At night in her apartment, though, she began binge-eating, which she says led to feelings of depression and guilt.

“That never had happened before I came to Oregon,” she says. “I never had any issues with food. I was completely fine. I loved food.”

At Oregon, she says, the yearlong monitoring became a trigger.

“You want to make sure you don’t put on weight, you become more paranoid and it gets worse,” she says.

She left after the school year, and still fights the temptation to binge.

Another athlete says her events coach conferred with her during her freshman year. She says he admitted he wasn’t supposed to tell her this, but said if she were to go above a certain body weight she never would be an Olympian.

After her first DEXA scan, the nutritionist told her she couldn’t travel to away track meets unless her body fat level was below 12%.

“That was when I started counting calories,” she says.

She says she weighed herself daily. What she saw on the scales determined whether she viewed her day as successful.

If she was above the targeted weight, “I would look at my legs, and I would say, ‘My legs look like tree trunks,’” she says. “If I was below that weight, I would be like, ‘Oh, I must be skinny.’ In reality, two or three pounds looks no different on your body.

“It wasn’t until I started seeing a sports psychologist that I realized this was not normal.”

That came after she transferred and her new school flagged her for an eating disorder.

A third athlete says that during her freshman year Johnson called her over during a workout and asked if she was on birth control.

Stunned by the question, she stammered “no” and returned to the workout.

“It was very crazy,” she says. “I was like, ‘What is going on? This is not happening. I am not having this conversation with him right now. This is just wrong. It’s none of his business.’”

She returned to ask Johnson why he wanted to know.

She says he told her: “Well, I noticed your hips have gotten wider, and that comes along with that kind of stuff.”

She says at Oregon she constantly monitored what she ate.

“They do multiple things to people about their weight,” she says. “They’re kind of notorious for it. They keep weight at a very high importance level. …

"Like whenever I would eat a cookie, I would feel so guilty. I would be like ‘Wow, it’s going to make my next DEXA scan bad. I’m going to get in trouble.’”

Four of the women interviewed say athletes whose DEXA scans show what coaches/staff consider an unacceptably high body fat content frequently are required to do additional cross training on a stationary bike.

Other athletes know who is doing mandatory cross training and why, even though it’s not explicitly said.

Athletes interviewed say this not only stigmatizes those doing the extra training, but incentivizes others to carefully monitor themselves so they aren’t singled out in that way.

“This program is just something different,” says one athlete who left the UO track team. “I don’t think it’s a place for young girls.

“Girls already have enough body image issues.”

“WE TRY TO APPROACH IT WITH SCIENCE”

Johnson said he would respond to specific allegations in general because he didn’t know which athletes were making the allegations. He says he feels sympathy and regret for athletes who believe they developed eating disorders while part of his program.

He says he and others in positions of responsibility within the program have acted swiftly and decisively to intervene when learning of athletes with disordered eating, or with emotional or physical problems.

“If these things were happening, such as binge-eating, or they were going down this road of unhealthy behaviors, hopefully we would catch it, and then give them resources to get better,” Johnson says.

“The health and safety of all our student-athletes is extremely important and at the forefront at all times.”

Johnson says nutritionists meet regularly with athletes in each event group so they understand the program’s approach and to identify any potential problems.

“We try not to let this weight issue be the pink elephant in the room,” he says. “We try to approach it with conversation and we try to approach it with science. … That’s one thing the DEXA scan helps us do. It takes our personal opinions out of it.”

Johnson says all UO athletes receive DEXA scans, men and women. He says UO track athletes are told there are sports psychologists available to them if they are struggling mentally with any aspect of being a college athlete.

But he says neither he nor psychologists can help if athletes don’t come forward.

“If those things were their experiences here, it’s shameful,” Johnson says. “We try to give them the information and the execution to deal with these things. If they choose to engage in those, there is help there. We can’t read their minds.”

Johnson says if he asked an athlete about birth control, it would have been only to suggest she use one recommended by UO doctors so weight gain wouldn’t be a side effect.

He says mandatory cross training isn’t meant to stigmatize athletes, but to help them get into competitive shape. He says that is part of his responsibility as coach.

Johnson says he could send those athletes on extra training runs to accomplish the same purpose. But that would expose their legs and feet to more pounding and increase the potential for injury.

“It’s basically that we want to increase their activity level in a safe manner that allows them to move closer to achieving their goals they set for themselves,” he says.

Many UO athletes compete for the Ducks without adverse effects.

Sprinter Rachel Vinjamuri says she is untroubled by the different ways the program monitored her, including the DEXA scans that revealed her body fat percentage.

“I never had a negative mindset about it,” says Vinjamuri, who transferred to UO from Portland State and graduated in 2020.

“It was just like this is where you need to be at to perform your best and here is how we do it. It was never like you get punished. It was just, let’s work toward this.”

She says she found the coaches and nutritionists constructive and helpful.

“People are more aware that eating disorders, dieting and things like that are becoming a huge problem in college sports,” she says. “I think Oregon is becoming more aware of that. I think they were doing the best they could.”

Vinjamuri says one difference between Portland State and Oregon is the superior resources at UO. In addition to the various high-tech tests, UO athletes have access to nutritionists who supplied them with snack bags of healthy food and recipes.

Some athletes who have competed for other programs in Power Five conferences, though, say differences in approach between Oregon and those programs are stark.

One says at her current school “everything is about holding yourself accountable. But if you don’t, you’re not getting punished. I think it’s the way you should treat college athletes. We’re adults. We’re not high schoolers anymore.”

Dan Steele was an assistant track coach at Oregon through 2009. He later was head coach at Northern Iowa and an assistant at Iowa State. He says his coaching philosophy is to steer clear of discussions about weight and body fat percentage.

“Testing for body fat is humiliating and detrimental to the athlete’s psyche,” he writes in a text message. “Young female athletes need to know their coaches believe in them.”

Steele says he never brought up an athlete’s weight or appearance, believing the athlete is the person most aware if she is too heavy or out of shape.

“I always tell them, ‘You’re fine. If you eat sensibly your body will morph naturally to the perfect size for optimum performance,’” he texts. “And that’s what I believe.”

“ATHLETES ARE NOT MACHINES”

Body weight and body fat percentage do factor into athletic performance. But several sports psychologists see red flags in approaches such as the one Oregon uses, particularly with women college athletes.

The sports psychologists consulted spoke in general terms, and not specifically about the UO track program.

Eugene sports psychologist Melissa Todd says she finds a process-oriented training approach better for college athletes than ones targeting a specific outcome.

She says young adults, away from home for the first time, are at a vulnerable point in their lives. The danger of emphasizing weight or body fat percentage is that those arbitrary numbers can begin to define victory for competitive people conditioned to win.

The first rule of any training strategy, she says, “should be to seek to minimize the potential for harm.”

“Athletes are not machines,” Todd says. “We need to see them in their entirety, as a whole person, and not boil down athletic performance to small details while missing the big picture.”

Portland sports psychologist Brian Baxter agrees, saying coaches should be at least as concerned with athletes’ emotional and mental well-being as they are with skill, technique and conditioning.

“The physical body doesn’t matter without mental health,” Baxter says. “Really, that has to be first.”

On its website, the National Eating Disorders Association includes a “Coach & Athletic Trainer Toolkit” for working with athletes. It includes this admonition:

“Coaches should strive not to emphasize weight for the purpose of enhancing performance, for example by weighing, measuring body fat composition, and encouraging dieting or extra workouts.”

The toolkit section of the website continues to say coaches who emphasize those things can lead athletes into unhealthy behaviors such as disordered eating that offset any gains achieved by lowering weight or body fat percentage.

The email sent in October 2020 to Peterson, the deputy athletic director and senior women’s administrator, seems not to have altered Johnson’s use of DEXA scans to monitor body fat percentage.

Responding by email, Peterson writes that she forwarded the email detailing concerns about the track program’s use of DEXA scans to “the appropriate campus officials.”

UO spokesperson Jimmy Stanton issued a statement in which he says the health and safety of athletes is the athletic department’s top priority.

Stanton’s statement continues: “There are many sports professionals on our staff that work closely in supporting student-athletes, including our medical team, athletic trainers, sports scientists and nutritionists. Additionally, all of our coaches undergo annual training from the UO Title IX office on a variety of topics, including communication with student-athletes.”

by Oregon Live

Login to leave a comment

Mary Cain sues Alberto Salazar and Nike for $20 million over alleged abuse

Mary Cain, the promising distance runner whose career fizzled after what she has described as four miserable years at the Nike Oregon Project, has filed a $20 million lawsuit against her former coach, Alberto Salazar, and their employer, Nike.

Cain accused Salazar of emotionally abusing her when she joined the team as a 16-year-old. The lawsuit portrays Salazar as an angry control freak who was obsessed with Cain’s weight and didn’t hesitate to publicly humiliate her about it.

That, she said, took a toll on her physical and mental health. Nike was aware, the lawsuit alleges, but failed to intervene.

Nike did not return messages. Salazar could not be reached but has previously denied abuse allegations, and he has said neither Cain nor her parents had raised concerns while she was part of the program.

In the lawsuit filed Monday in Multnomah County Circuit Court, Cain alleges Salazar on several occasions required her to get on a scale in front of other people and would then criticize her.

“Salazar told her that she was too fat and that her breasts and bottom were too big,” the lawsuit alleges.

Salazar took to policing Cain’s food intake, she said. At times, Cain was so hungry, she said, she stole Clif Bars from teammates.

Cain went to her parents for support. She alleges Salazar eventually tired of the parental interference.

“He prevented Cain from consulting with and relying on her parents, particularly her father, who is a doctor,” said Kristen West McCall, a Portland lawyer representing Cain.

By 2019, Cain says she was deeply depressed, had an eating disorder, generalized anxiety and post-traumatic stress syndrome. She also was cutting herself.

Darren Treasure, Nike’s in-house sports psychology consultant, knew of Cain’s distress, the lawsuit alleges. But he’s accused in the complaint of doing nothing about it, other than to share this “sometimes intimate and confidential information … with Salazar.”

Nike did nothing to intervene, Cain alleges.

“Companies are responsible for the behavior of their managers,” McCall said. “Nike’s job was to ensure that Salazar was not neglecting and abusing the athletes he coached.”

McCall added: “Nike was letting Alberto weight-shame women, objectify their bodies, and ignore their health and wellbeing as part of its culture. This was a systemic and pervasive issue. And they did it for their own gratification and profit.”

Nike athletes generally sign non-disclosure statements that strictly prohibit them from revealing any sensitive corporate secrets. Cain smashed the Nike code of silence two years ago when The New York Times published her wrenching account of her years at Nike.

Due in part to a protracted series of injuries, Cain never lived up to her superstar-in-the-making expectations. But when she was 16, after a brilliant high school running career, she was a hot commodity in distance running circles.

In 2012, she opted to skip college and go straight to Beaverton to run for Salazar. Salazar, himself a legendary runner, helped found the Nike Oregon Project to make American distance runners competitive with the rest of the world.

Salazar has had some big successes, particularly with Galen Rupp, the Portland kid who has become one of the world’s best marathoners. On Aug. 5, 2012, two Salazar athletes — Mo Farah and Rupp — finished one-two in the 10,000 at the Olympic Games in London.

His program also has been dogged by allegations that he pushed the use of performance-enhancing drugs.

The Nike Oregon Project was disbanded in 2019 after the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency accused Salazar of three violations. The agency banned him from the sport for four years.

Salazar appealed to the Court for Arbitration for Sport. Last month, the court upheld Salazar’s ban from the sport and some of USADA’s findings. It ruled that Salazar attempted an “intentional and orchestrated scheme to mislead” anti-doping investigators when he tampered with evidence.

The court reduced the duration of his ban from four to two years.

Salazar added: “Mary at times struggled to find and maintain her ideal performance and training weight.” Nike added that Cain had requested to be allowed back on the team after she left.

Salazar said this to Sports Illustrated:

My foremost goal as a coach was to promote athletic performance in a manner that supported the good health and well-being of all my athletes. On occasion, I may have made comments that were callous or insensitive over the course of years of helping my athletes through hard training. If any athlete was hurt by any comments that I have made, such an effect was entirely unintended, and I am sorry. I do dispute, however, the notion that any athlete suffered any abuse or gender discrimination while running for the Oregon Project.”

by Jeff Manning

Login to leave a comment

Nike wasn't 'giving me really what I needed,' U.S. Olympian says about jumping to LuluLemon

When her contract with Nike (NKE) was up for renegotiation, American Olympian Colleen Quigley chose to leave the athletic apparel giant for a different type of deal with Lululemon (LULU).

"I've been with Nike since 2015 when I graduated from Florida State University... and joined the team out here in Portland, then had a great five-year run with them,” Quigley said on Yahoo Finance Live. “But I think when I got to the end of that, I just decided that they weren't giving me really what I needed off of the track and not really seeing me as anything more than just a runner.”

Quigley — a 2016 U.S. Olympic 3000m steeplechaser who withdrew from 2021 Olympic trials — joins a growing number of athletes who were dissatisfied with Nike endorsement deals. Other top runners that parted ways with footwear giant include Mary Cain and Allyson Felix, who respectively spoke out about the company's allegedly toxic culture and lack of maternity protections.

“I started to see myself as more than a runner, and I like to do a lot of different things," Quigley said. "I have different initiatives that I'm working on, really focusing on young athletes and young female athletes."

Lululemon "values me as that whole person," she added, "which is really what drew me to them."

Colleen Quigley places second in women's steeplechase heat in 9:53.48 to advance during the USATF Championships Jul 26, 2019; Des Moines, IA (Kirby Lee-USA TODAY Sports)

"You don't have to be on top of the podium to really send a strong message”

Professional athletes in sports such as track and field seek sponsorship deals for compensation since there are few leagues — particularly for women — that pay viable salaries. For college stars like Quigley, signing with a major brand represents the dream of taking one's running career to the next level.

When describing her contract with Nike, Quigley stressed that it was a “transactional relationship.”

“So you run this time, you qualify for this team, you place top three, and you get paid this amount, and if you don't perform and you don't make the team and you don't get a medal, then you don't get paid,” she said. “All of the traditional brands really just see you as a results machine and what you can perform, and what you can give them on the track is really the only thing that they value.” Nike estimated that it will spend $1.33 billion in endorsement contracts in fiscal year 2021, according to company filings. That figure varies based on how well athletes perform and doesn't include the cost of athletic gear provided to endorsers.

Despite the massive marketing machine, top women athletes are increasingly looking for sponsorships that go beyond rewarding athletic accomplishments.

In 2019, Olympic sprinter Allyson Felix departed from Nike after she said she felt pressure from the company to return quickly after her pregnancy and accept a significant pay cut.

“If we have children, we risk pay cuts from our sponsors during pregnancy and afterward," she wrote in an op-ed at the time. "It’s one example of a sports industry where the rules are still mostly made for and by men." (Nike updated its maternity policy to guarantee pay for pregnant athletes after Felix, as well as runners Alysia Montaño and Kara Goucher, went public with their pregnancy stories.)

by Grace O’Donnell

Login to leave a comment

Alberto Salazar gets lifetime ban for sexual, emotional misconduct

Alberto Salazar, the 1982 Boston Marathon champion from Wayland and once a prominent Nike coach of some of the world’s top distance runners, was permanently barred from participating in track and field Monday by the US Center for SafeSport, which cited Salazar for sexual and emotional misconduct.

Salazar, 62, has 10 business days to request an appeal through arbitration of the ruling made by SafeSport, a nonprofit founded in 2017 to protect athletes from sexual, physical and emotional abuse.

The decision Monday was the latest stage of a humiliating fall for Salazar, who was suspended for four years in September 2019 by the United States Anti-Doping Agency for violating rules governing banned substances. He is appealing that suspension to the Court of Arbitration for Sport, the Swiss-based equivalent of a Supreme Court for international sports.

The SafeSport charges were not detailed Monday. In January 2020, the organization temporarily barred Salazar from participating in track and field after elite female runners who formerly trained under him, including Mary Cain, Amy Yoder Begley and Kara Goucher, described what they said were years of psychological and verbal abuse by the coach.

Neither Salazar nor his lawyer immediately responded to requests for comment Monday. Salazar has previously denied all accusations of misconduct.

In a 2019 video produced by the Opinion department of The New York Times, Cain, a former high school phenom from New York who is now 25, accused Salazar of shaming her in front of others on the Nike Oregon Project team — which has since been disbanded — when she did not reach weight targets. She said that her low weight caused her to miss her period for three years, leading to lower levels of estrogen and five broken bones.

Cain also said that she had suicidal thoughts and had cut herself, but that no one at Nike “really did anything or said anything.”

Yoder Begley, a 2008 Olympian, tweeted in 2019 that she was removed from the Oregon Project after a disappointing showing in the 10,000 meters at the 2011 United States track and field championships.

“I was told I was too fat and ‘had the biggest butt on the starting line,’ " Yoder Begley wrote.

Goucher, another American Olympian who once trained with the Nike Oregon Project, told The Times that after being cooked meager meals by an assistant coach, she often ate more in the privacy of her room, nervous that she would be heard opening the wrappers of energy bars she furtively consumed.

Salazar replied to Cain’s 2019 video in a statement to The Oregonian newspaper: “Neither of her parents nor Mary raised any of the issues that she now suggests occurred while I was coaching her. To be clear, I never encouraged her, or worse yet, shamed her, to maintain an unhealthy weight.”

Cain acknowledged at the time that she had sought to train again with Salazar, seeking an apology, closure and his approval. But she described their relationship as poisonous, saying, “I was the victim of an abusive system, an abusive man.”

Salazar told Sports Illustrated in 2019 that his “foremost goal” was to promote athletic performance in line with the good health and well-being of his athletes, but he acknowledged, “On occasion, I may have made comments that were callous or insensitive.”

by Jere Longman

Login to leave a comment

Mary Cain launches professional women's running team

Mary Cain has announced the launch of her new professional women’s running team, Atalanta New York. Cain previously ran for Alberto Salazar and the Nike Oregon Project (NOP), and in 2019, four years after leaving the team, she opened up about the emotional and physical abuse she endured in her short time training with that group. That abuse pushed Cain to the point of considering suicide, and it was fuelled by Salazar’s win-at-all-costs mentality. Cain is now looking to fight this mindset (which was not unique to the NOP), and Atalanta NY will work to empower and support its athletes and young female runners everywhere.

Cain is the president and CEO of Atalanta NY, an endeavour she says is the next step in her fight against the toxicity plaguing the world of athletics. “Ever since I shared my story to The NY Times, I have wanted to do more,” she wrote on Instagram. The first step in this fight, she said, was speaking out against Salazar, the NOP and the must-win culture (which has led to the abuse of so many female athletes) in track. “Maybe it’s the runner in me, but I wanted to take more than a first step.”‘

Atalanta NY is a New York City-based nonprofit that will employ its athletes, not as competitors, but as mentors to young women in the running community. This takes the emphasis off of performance (which is the usual focus for professional running teams) and instead places it on community involvement, something that Cain said she believes will “shake up the current model of professional sports.”

This is similar (although not identical) to the structure of Tracksmith’s partnership with Cain. In 2020, Cain signed with Tracksmith to work as a full-time employee while also running for the brand. This allowed Cain to run worry-free, as her contract was not dependent on her results, but rather on her work as the brand’s New York City community manager. Cain is still representing Tracksmith, and the company is a founding sponsor of Atalanta NY.

“Atalanta New York’s mission is two-fold,” reads a post on the Tracksmith Instagram page. “As a team, its goal is to help elite runners chase their athletic dreams through a sustainable and healthy organizational model. As a nonprofit, the goal is to educate and inspire young female athletes in underserved New York communities to find joy and wellness through sport.”

So far, Atalanta NY has only named two professional athletes to the team: Cain and Jamie Morrissey. Cain hasn’t raced much in the past few years (she raced four times in 2020, interrupting a four-year break from competition), but she still owns several big records, including the world U20 indoor 1,000m record (2:35.80) and American U20 two-mile best (9:38.68). Morrissey is a former University of Michigan standout who owns a PB of 4:11.48 in the 1,500m.

No other runners have been publicly added to the team yet, but Cain has said there will be more athlete announcements soon. To learn more about Atalanta NY and the team’s mission,

by Running Magazine

Login to leave a comment

Record-crushing track superstar Mary Cain launches professional women’s running team

Mary Cain has announced the launch of her new professional women’s running team, Atalanta New York. Cain previously ran for Alberto Salazar and the Nike Oregon Project (NOP), and in 2019, four years after leaving the team, she opened up about the emotional and physical abuse she endured in her short time training with that group. That abuse pushed Cain to the point of considering suicide, and it was fuelled by Salazar’s win-at-all-costs mentality.

Cain is now looking to fight this mindset (which was not unique to the NOP), and Atalanta NY will work to empower and support its athletes and young female runners everywhere.

Cain is the president and CEO of Atalanta NY, an endeavour she says is the next step in her fight against the toxicity plaguing the world of athletics. “Ever since I shared my story to The NY Times, I have wanted to do more,” she wrote on Instagram. The first step in this fight, she said, was speaking out against Salazar, the NOP and the must-win culture (which has led to the abuse of so many female athletes) in track. “Maybe it’s the runner in me, but I wanted to take more than a first step.”‘

Atalanta NY is a New York City-based nonprofit that will employ its athletes, not as competitors, but as mentors to young women in the running community. This takes the emphasis off of performance (which is the usual focus for professional running teams) and instead places it on community involvement, something that Cain said she believes will “shake up the current model of professional sports.”

This is similar (although not identical) to the structure of Tracksmith’s partnership with Cain. In 2020, Cain signed with Tracksmith to work as a full-time employee while also running for the brand. This allowed Cain to run worry-free, as her contract was not dependent on her results, but rather on her work as the brand’s New York City community manager. Cain is still representing Tracksmith, and the company is a founding sponsor of Atalanta NY.

“Atalanta New York’s mission is two-fold,” reads a post on the Tracksmith Instagram page. “As a team, its goal is to help elite runners chase their athletic dreams through a sustainable and healthy organizational model. As a nonprofit, the goal is to educate and inspire young female athletes in underserved New York communities to find joy and wellness through sport.”

So far, Atalanta NY has only named two professional athletes to the team: Cain and Jamie Morrissey. Cain hasn’t raced much in the past few years (she raced four times in 2020, interrupting a four-year break from competition), but she still owns several big records, including the world U20 indoor 1,000m record (2:35.80) and American U20 two-mile best (9:38.68). Morrissey is a former University of Michigan standout who owns a PB of 4:11.48 in the 1,500m.

No other runners have been publicly added to the team yet, but Cain has said there will be more athlete announcements soon.

by Ben Snider-McGrath

Login to leave a comment

Shelby Houlihan will not compete at Trials after all

The U.S. Olympic track and field trials are set to start today, and American 1,500m and 5,000m record holder Shelby Houlihan will not be on the start line, after all. Mere hours after the USATF announced she would be permitted to compete, the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee reversed the decision in an effort to remain in line with the Court of Arbitration for Sport’s (CAS) ruling to uphold her four-year ban.

Earlier this week, the track and field world learned that Houlihan had received a four-year ban after she tested positive for the steroid nandrolone. She protested vehemently that she had ever taken performance-enhancing drugs, blaming the positive test on contaminated meat in a burrito she had eaten 10 hours before being tested.

The reversal came after pushback from the international anti-doping community as well as several prominent elite runners, who believed a banned runner should not be permitted to compete at trials. The Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU), which runs the anti-doping program for World Athletics, released a statement Thursday saying that the USATF must respect and implement the decisions of the CAS. The Clean Sport Collective also published a petition against letting her compete, signed by a number of athletes, including Des Linden, Steph Bruce, Mary Cain, Emma Coburn, Mason Ferlic, Molly Seidel, Emily Sisson and retired Canadian pro runner Nicole Sifuentes.

Under normal circumstances, athletes who test positive for a banned substance first have a hearing before the AIU, but with the Olympic trials so close, Houlihan took her appeal straight to the CAS in Switzerland. The CAS upheld her ban, which leaves her with only one option: to appeal the CAS decision before a Swiss Federal tribunal. According to sources, however, this avenue is only for matters of procedure, while the decision itself is binding. Not only will Houlihan miss this year’s Olympics, but she will miss the 2024 Games also.

by Running Magazine

Login to leave a comment

Some Veteran Pro Runners Are Making Less This Year, and They're Ditching the Sport

Many athletes are confronting a bleak financial reality. Some are quitting the sport entirely.

What do Noah Droddy, Ben True, and Andy Bayer have in common?

They’re all ranked among the top 10 Americans of all time in their events—Droddy in the marathon, True in the 10,000 meters, Bayer in the steeplechase.

How Much Do Pro Runners Make? For Some Veterans, It’s Less This Year

And they were all dropped by their sponsors at the end of 2020.

This news took a while to seep out—after all, athletes don’t tend to publicize it when their sponsors reduce their pay or stop supporting them altogether. But Droddy, 30, and True, 35, have been open about their status and confirmed it in calls with Runner’s World (both had been sponsored by Saucony), and Bayer told the Indy Star that Nike dropped him and he has left the sport, at age 31, for a job in software engineering.

Droddy—one of running’s most recognizable figures in races with his long hair, backward baseball cap, and habit of losing his lunch at marathon finish lines—summed up his situation in a tweet on February 19.

Is he right? Is it typical for top runners, at the height of their careers, to lose financial backing from shoe companies? Or is this an anomaly at the end of an unusual, pandemic-marred 15 months?

Runner’s World had conversations with eight athletes, four agents, two marketing employees at brands, and three coaches to get a sense of the current economics for athletes. They painted a complex picture.

Are most pro runners broke?

Many are just getting by. For years, America’s pro runners have been on shaky financial footing. With the exception of those who win global medals or major marathons, distance runners often struggle to earn enough money to pay for their essentials (rent and food), plus cover all their running-related expenses, such as coaching, travel to races and altitude camps, health care, gym membership, and massage.

Over the past year, the pandemic has erased lucrative racing opportunities. Additionally, shoe companies have been reevaluating their sports marketing budgets, from which runners are paid. Experts say that the result has been an increasing bifurcation between the sport’s haves and have nots.

The most successful, those destined for the Olympic team or starring on the roads, are earning generous base payments and bonuses for setting records or winning. Many of the rest are scraping by, with smaller contracts, if any, and they’re supplementing their shoe company earnings with jobs.

Running’s middle class, much like America’s, is shrinking.

The exception is runners who belong to a single-sponsor training group, like those in Flagstaff, Arizona (Hoka); Boston (New Balance); and Portland, Oregon (Nike). In those cases, coaching, travel, and training camp costs are absorbed by the club, easing the financial pressure on athletes and making it possible for them to pursue the dream.

Brands these days appear to be more eager to devote dollars to groups and the athletes who train with them, rather than individual athletes training on their own in different locations. That presents a quandary for midcareer runners who have achieved a level of success. Faced with the loss of a sponsorship, they aren’t always willing to pick up and move to a new town and a new coach.

What do contracts look like?

If you’re a top runner in the college ranks, and you’ve won multiple NCAA titles at the Division I level, shoe companies—Nike, Adidas, Brooks, Saucony, Hoka, and others—will usually come calling, offering more than $100,000 a year for multiple years, with a spot in a group or a stipend to pay your coach. Those companies are betting on those NCAA champions to be Olympians of the future.

Dani Jones, for instance, won three individual NCAA titles at the University of Colorado, and she signed with New Balance at the end of last year. Her agent, Hawi Keflezighi, said she entertained competing offers from other companies.

A midcareer athlete with a breakthrough performance—hitting the podium at a major marathon or making an Olympic team, for instance—might also be rewarded with a base contract worth $50,000 to $100,000.

The top sprinters earn even more (although their careers are typically shorter). Usain Bolt famously made millions, and Canadian sprinter Andre De Grasse was 21 when he signed a deal worth $11.25 million—before bonuses—from Puma in 2015, the Toronto Star reported.

The payouts drop significantly after that. Let’s say you’re a distance runner, but you haven’t been able to get a big win in college, although you’ve come close. The lucky ones are looking at deals for about $30,000 to $75,000 per year.

Your agent takes a 15 percent cut of that. And this base salary most often comes without benefits: no health insurance, no 401(k). As independent contractors, pro runners are paying all their own taxes. (In contrast, traditional full-time employees have half of their Social Security and Medicare taxes paid by the employer.)

Many young runners out of college join pro groups, and they’re not making anything beyond free gear and coaching. Others might get a stipend worth $10,000 or $12,000 a year.

The contracts typically sync with the Olympic calendar. At the end of 2020, many athletes’ contracts were expiring—even though the Olympics didn’t happen. That’s how Droddy, True, and Bayer were dropped. Shannon Rowbury, a three-time Olympian, told Track & Field News her deal with Nike was extended for one year, two if she makes the Olympic team this summer.

If an athlete has a good Olympics, the sponsoring company often has an option to extend the deal for an additional year, which includes the world track & field championships. It’s at the company’s discretion—not the athlete’s.

Parts of the sponsorship model appear to be changing, but slowly. When NAZ Elite announced a new deal with Hoka last fall, it included health insurance for the runners. Similarly, members of Hansons-Brooks in Rochester, Michigan, get health insurance if they work in the Hansons running specialty stores. And last May, Tracksmith brought Mary Cain and Nick Willis on as employees at the company—Cain in community engagement, Willis as athlete experience manager—with the plan that both would continue to train and race at an elite level.

Why doesn’t anyone know exactly how much runners are making?

As part of these deals, athletes have to sign non-disclosure agreements (NDAs), promising to keep the terms quiet. If an athlete violates the NDA, the sponsor can void the contract—or sue for breach of contract.

This is, in fact, similar to other sports. In basketball, LeBron James is being paid $39.2 million this season by the Los Angeles Lakers. But he also has an endorsement deal with Nike, and the exact structure of that is unknown.

In running, prize purses are publicized—$150,000 for winning the Boston Marathon, $25,000 for being the top American at New York in 2019, $75,000 for winning the Olympic Marathon Trials.

But as in other sports, the terms of the sponsor deals are kept mum. And appearance fees at major races, as well as time bonuses within those appearance fees, which represent a major source of income for road runners (mainly marathoners), are also mostly unknown.

Athletes feel that the silence around sponsor contracts and appearance fees puts them at a disadvantage—it’s hard to know their market value. Yes, they can—and do—have quiet conversations with peers about it. But lacking broad knowledge, they lack power.

And as a result, the industry is rife with rumors and assumptions. Athletes’ values are often inflated through the grapevine.

“I think it is very similar to the dynamic that would occur if no one knew the price of home sales,” Ian Dobson—a 2008 Olympian who ran for Adidas and Nike during his pro career, which ended in 2012—told Runner’s World. “How could you ever be confident in a sale price if you didn’t know what any other homes in your neighborhood were selling for? Granted, we don’t know every detail of every home sale in the neighborhood, but it’s certainly helpful to know in general terms the dollar amount that these are going for so that we can all understand what value our home might have.”

Also, athletes keep quiet when their circumstances change. They feel embarrassed. One athlete told Runner’s World, “No one in track wants to be the one to say, ‘I got dropped,’ or ‘I got reduced.’ It's all taboo.”

Even so, $30,000 is nothing to sneeze at—especially for a job that’s about pursuing individual goals.

No, it’s not. But not every contract is structured the same way.