Running News Daily

Top Ten Stories of the Week

6/22/2024

These are the top ten stories based on views over the last week.

To Fight Midlife Blues, Try Mastering Something Difficult

How is it possible to become good at something when you’re already far behind and time isn’t on your side?

That was the question pressing against my brain in April 2018. I was four months shy of my 47th birthday and had just completed my first obstacle-course racing competition, something called a Spartan Race. My age put me at the rock bottom of the well-known U-shaped curve of life happiness, bracketed on either side by younger and older adults. I was content enough, but my days were clouded by sameness—the same work routine, same circle of friends, a narrowing of interests skewed to my competencies.

Trying to interrupt my midlife slump with this race was predictable, I suppose. What happened to me after that day was not.

As an unathletic desk jockey glued to my screens, training for the competition seemed like a way to fight back against inertia and a body heading past its prime. Obstacle-course racing combines endurance running in often difficult terrain with military- and hunter-gatherer-styled obstacles: crawling under barbed wire in mud, lugging heavy sandbags up mountains, climbing ropes, scaling walls. You even throw a spear. A version of the sport will be included in the 2028 Olympics as part of the modern pentathlon.

As someone who’d chosen bowling to fulfill my university’s physical education requirement and earned the nickname “Bones” in junior high for her physique, my goal was simple: Finish and don’t die. Then I’d go back to my sitting and screens, with my race T-shirt tucked in the drawer—a sartorial red sports car to don when midlife seemed bleak.

But in the days after crossing the finish line—a middle-aged athletic nobody who fell 10 feet off a rope during the competition into a crumpled heap of humiliation—all I could think about (apart from how much every part of me hurt) was: When can I race again? And how can I get better—a lot better?

I’d taken my first step on the road to mastery—a journey that has been profoundly humbling, and one that I’ll likely never finish.

I n today’s culture, we celebrate “life hacks” and shortcuts to good health and happiness, whether through supplements, fad diets, five-minute workouts or the short-lived dopamine hit of social media likes. In the workplace, completing goals by setting and achieving KPIs (key performance indicators) often determines our professional value. These expectations can make it difficult to start something new and hard in midlife, when we tend to gravitate toward what we’re already good at and the rewards that come with completing it.

At first, I certainly fell into this mindset. Closing in on age 50, “mastery” seemed vaguely absurd. Haunting me was the much-discussed 10,000-hour rule popularized by Malcolm Gladwell in his book “Outliers,” where he suggested that it usually takes that much specialized practice to become an expert in a discipline. Even with two hours a day of training—if I could manage that with a full-time job and loads of middle-aged responsibilities—it would take more than 13 years to hit the mastery mark. I’d be 60. Mastery, I felt, was a journey for those who start young.

But my experience and research over the past six years show that I was wrong to see the challenge in such stark, age-bound terms. As I discovered, pursuing something difficult at any age can have profound benefits for health and happiness, even if you never become a master or an expert.

Becca Levy, a professor of epidemiology at Yale, examined data from one of the country’s most detailed studies of growing older, the Ohio Longitudinal Study on Aging and Retirement, and overlaid it with mortality data. She found that older people with more positive perceptions of aging live 7.5 years longer, on average, than those who are less positive.

One factor believed to fuel this longer lifespan is a “will to live,” which can include pastimes that excite and push us. This doesn’t mean we should be occupied all the time. There’s a lot of creative and mental good to be gained from putting down our smartphones, turning off the TV and letting the mind wander. But chronic boredom and a general lack of purpose have been correlated with anxiety, depression and risk of making mistakes.

That feeling began creeping into my life before I discovered obstacle-course racing. But humbling myself among younger people in gyms, training nearly every day no matter how busy or tired, having the goal of racing in new places (like the Arabian Desert)—it has ignited in me a renewed will to live. I am constantly learning, relearning and unlearning.

I am also constantly having to be OK looking dumb.

The Greek Stoic philosopher Epictetus mused that if you want to improve at something, you need to “be content to be thought foolish and stupid.” I’ve channeled his wisdom, flailing about on playground monkey bars as impatient children commented on my technique and their amused parents (my peers) watched. Neighbors can see me crawling around my backyard like a wounded animal, performing mobility exercises with stiff middle-aged limbs.

I have felt the sting of finishing races almost dead last, and I once quit a competition midway because I was too cold. I’d never quit anything in my life until that point. Showing up at my gym the next day with everyone else clad in their finisher T-shirts felt like not getting invited to prom.

On the other hand, it’s very hard to be bored slithering under barbed wire in mud, hurling spears and learning to pull yourself up a 17-foot rope. And with improvement has come a mental shift to believe the file labeled “me” isn’t finished—that I can still add to it.

These benefits are available on a variety of fronts as we age. The Seattle Longitudinal Study, started in 1956, is one of the most comprehensive research projects on how we develop and change cognitively throughout adulthood. Among its key findings: Some abilities, such as word skills, may increase into our 60s and beyond, particularly for women, while others, such as spatial abilities—think assembling furniture or reading a map—hold up into our 80s for men. That’s a lot of opportunity for later-in-life learning and journeys of mastery.

Here’s the thing about trying to achieve mastery later in life: You may not reach your destination. And I’ve come to believe that’s a good thing. Because unlike the enjoyable activities we pursue that have definitive endings—taking a walk, eating a great meal, going on vacation—training to get good at something hard is ongoing, incomplete. And that’s the beauty of it: There’s always something to look forward to.

Regardless of what you’re trying to master—fly fishing, chess, pickleball—experts say that regular movement of some sort is critical for maintaining the physical and cognitive health you’ll need. Starting a new exercise program, particularly in midlife, when noticeable decline often begins, “can really interrupt the pace of those not-good changes, those negative changes, and turn them into positive changes,” says Steven Austad, senior scientific director for the American Federation for Aging Research. New research, he adds, shows “physical activity is one of the best ways to avoid later-life dementia.”

Six years have passed since my first race. After some 4,000 hours of practice, I’ve advanced on the five-stage “Dreyfus model” of skill acquisition from “novice” to “advanced beginner” to “competence.” I now race competitively in my age group and have under my belt 19 top-three podium finishes and two world championship competitions. Some days, when everything is clicking, I may even touch the fourth stage of proficiency.

It’s a far cry from childhood, when I cowered behind my best friend during dodgeball and warmed my school’s bench in soccer games. Longevity is never guaranteed, but I’ve made strides to keep functioning independently as I age—lifting my suitcase into the airplane’s overhead bin, hiking three miles in snow if our car breaks down. I’m also more confident off the racecourse. Not long ago, I took a job with a tech start-up where I’m one of the oldest employees. Younger workers teach me about AI; I took a crew of them on their first Spartan Race.

Admittedly, I’m still coming to peace with the idea that I’ll never reach the final stage of “expert” at this sport I now love. I’ve met people who are experts: They possess natural talent I don’t, or have spent time training that I probably can’t at this point. There remain obstacles I fail during races more than I’d like; now that I’m 52 years old, I don’t know if that will change.

These reminders of my limitations and mortality are what’s been most humbling about the experience. But “never finished” may be the best medicine when life seems to be making a turn toward endings. I interviewed a woman in her 80s nicknamed “Muddy Mildred” who ran obstacle-course races. How far can I get with the time that is left to me?

1. Intrinsic motivation gets you farther than extrinsic motivation. Motivation from external factors—money, a promotion, a medal—can be short-lived. “I can probably get someone up from the couch to run a 10K if I give them enough money,” says Chad Stecher, a behavioral health economist and assistant professor at Arizona State University. “But after that 10K, unless I provide additional incentives or support, their physical activity won’t persist.”

Instead, look for a pursuit where you are motivated to engage because of personal satisfaction or a deeper drive. One place to start: childhood. What did you want to be or do when you grew up, but it hasn’t yet happened? My experience of being a gawky kid still drives me.

2. Cultivate a “growth mindset.” Believing your success is tied more to hard work than innate talent is critical on the mastery journey. The well-known Stanford University psychologist Carol Dweck talks about one Chicago school’s unorthodox but effective grading protocol, where instead of a failing grade, students would get a “Not Yet.”

You’re not going to become a good diver without landing a lot of belly-flops, or a competent fly-fisherman without the line occasionally getting wrapped up in a tree. It doesn’t mean you won’t get there; it just means you haven’t gotten there yet.

3. Locate edges and equalizers. Crystallized intelligence—your stored-up body of wisdom—can make age a secret weapon. The older you are, the more you’ve tried, failed, succeeded and learned. Draw from that bank. I can’t rely on a 25-year-old body to perform well, so I’ve turned to information: intel on gear, clothing, weather, hydration, terrain, sleep.

“When you’re older, you can see the bigger picture more than you could when you were 17,” says Alex Hutchinson, bestselling author of the book “Endure.” “It’s really easy to get excited about big goals, but to actually achieve them takes patience to take care of details, patience to stay on track when obstacles arise.”

4. Prioritize what’s essential. You can’t hack your way to mastery. It takes time and the “disciplined pursuit of less,” as Greg McKeown explains in his book “Essentialism.”

To include obstacle-course racing in an already full life, I trimmed my Instagram feed to mainly follow accounts helping me learn about the sport. After analyzing how much of my workday was spent in inefficient, hour-long, weekly one-on-one meetings, I cut most of them back to 25 minutes and set clear agendas. I declined all social invitations that weren’t from my closest friends and stepped away from many boards I served on. With every “no,” I got back a few more hours to devote to this new journey.

5. The mastery journey can be never-ending. And that’s fine. Finishing only that first race would have given me short-lived bragging rights and an awesome social media photo. But then it would have been over—extinguishing a source of meaning in my life.

It wasn’t until I firmly entered the realm of “never finished” that I realized how electrifying it could be. Which sure feels like a far cry from being stuck at the bottom of a U curve.

(06/18/24) Views: 215What You Need to Know About the U.S. Track and Field Olympic Trials

From June 21-30, more than 900 runners, throwers, and jumpers will put it all on the line for a chance to compete for Team USA at the Paris Olympics

The U.S. Track and Field Olympic Trials is a showcase of hundreds of America’s best track and field athletes who will be battling for a chance to qualify for Team USA and compete in this summer’s Paris Olympics. For many athletes competing in Eugene, simply making it on to the start line is a life-long accomplishment. Each earned their spot by qualifying for the trials in their event(s). The athlete qualifier and declaration lists are expected to be finalized this week.

But for the highest echelon of athletes, the trials defines a make-or-break moment in their career. Only three Olympic team spots (in each gender) are available in each event, and given the U.S. depth in all facets of track and field—sprints, hurdles, throws, jumps, and distance running events—it’s considered the world’s hardest all-around team to make. How dominant is the U.S. in the world of track and field? It has led the track and field medal count at every Olympics since 1984.

At the trials, there are 20 total events for women and men—10 running events from 100 meters to 10,000 meters (including two hurdles races and the 3,000-meter steeplechase), four throwing events (discus, shot put, javelin, and hammer throw), four jumping events (long jump, triple jump, high jump, and pole vault), the quirky 20K race walking event, and, of course, the seven-event heptathlon (women) and the 10-event decathlon (men).

(At the Olympics, Team USA will also compete in men’s and women’s 4×100-meter and 4×400-meter relays, plus a mixed gender 4×400, and a mixed gender marathon race walk. The athletes competing on these teams will be drawn from those who qualify for Team USA in individual events, along with alternates who are the next-best finishers at the trials.

There’s also the Olympic marathon, but the U.S. Olympic Trials Marathon was held on February 3 in Orlando, Florida, to give the athletes enough time to recover from the demands of hammering 26.2 miles before the big dance in Paris.

Although some countries arbitrarily select their Olympic track and field teams, the U.S. system is equitable for those who show up at the Olympic Trials and compete against the country’s best athletes in each particular event. There’s just one shot for everyone, and if you finish among the top three in your event (and also have the proper Olympic qualifying marks or international rankings under your belt), you’ll earn the opportunity of a lifetime—no matter if you’re a medal contender or someone who burst onto the scene with a breakthrough performance.

The top performers in Eugene will likely be contenders for gold medals in Paris. The list of American stars is long and distinguished, but it has to start with sprinters Sha’Carri Richardson and Noah Lyles, who will be both competing in the coveted 100 and 200 meters. Each athlete won 100-meter titles at last summer’s world championships in Budapest and ran on the U.S. gold-medal 4×100 relays. (Lyles also won the 200) Each has been running fast so far this spring, but more importantly, each seems to have the speed, the skill, and swagger it takes to become an Olympic champion in the 100 and carry the title of the world’s fastest humans.

But first they have to qualify for Team USA at the Olympic Trials. Although Lyles is the top contender in the men’s 100 and second in the world with a 9.85-second season’s best, five other U.S. athletes have run sub-10-second efforts already this season. Richardson enters the meet No. 2 in the U.S. and No. 3 in the world in the women’s 100 (10.83), but eight other Americans have also broken 11 seconds. That will make the preliminary heats precariously exciting and the finals (women’s on June 22, men’s on June 23) must-see TV.

There are five returning individual Olympic gold medalists competing in the U.S. Olympic Trials with the hopes of repeating their medals in Paris—Athing Mu (800 meters), Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone (400-meter hurdles), Katie Moon (pole vault), Vallarie Allman (discus), and Ryan Crouser (shot put)—but there are more than a dozen other returning U.S. medalists from the Tokyo Olympics, as well as many more from the 2023 world championships, including gold medalists Chase Ealey (shot put), Grant Holloway (110-meter hurdles), Laulauga Tausaga (discus), and Crouser (shot put).

The most talented athlete entered in the Olympic Trials might be Anna Hall, the bronze and silver medalist in the seven-event heptathlon at the past two world championships. It’s an epic test of speed, strength, agility, and endurance. In the two-day event, Hall and about a dozen other women will compete in the 100-meter hurdles, high jump, shot put, 200 meters, long jump, javelin throw, and 800 meters, racking up points based on their performance in each event. The athletes with the top three cumulative totals will make the U.S. team. At just age 23, Hall is poised to contend for the gold in Paris, although Great Britain’s Katarina Johnson-Thompson, the world champion in 2019 and 2023, is also still in search of her first Olympic gold medal after injuries derailed her in 2016 and 2021.

If you can find your way to Eugene—and can afford the jacked-up hotel and Airbnb prices in town and nearby Springfield—you can watch it live in person at Hayward Field. Rebuilt in 2021, it’s one of the most advanced track and field facilities in the world, with an extremely fast track surface, a wind-blocking architectural design, and 12,650 seats that all offer great views and close-to-the-action ambiance. Tickets are still available for most days, ranging from $45 to $195.

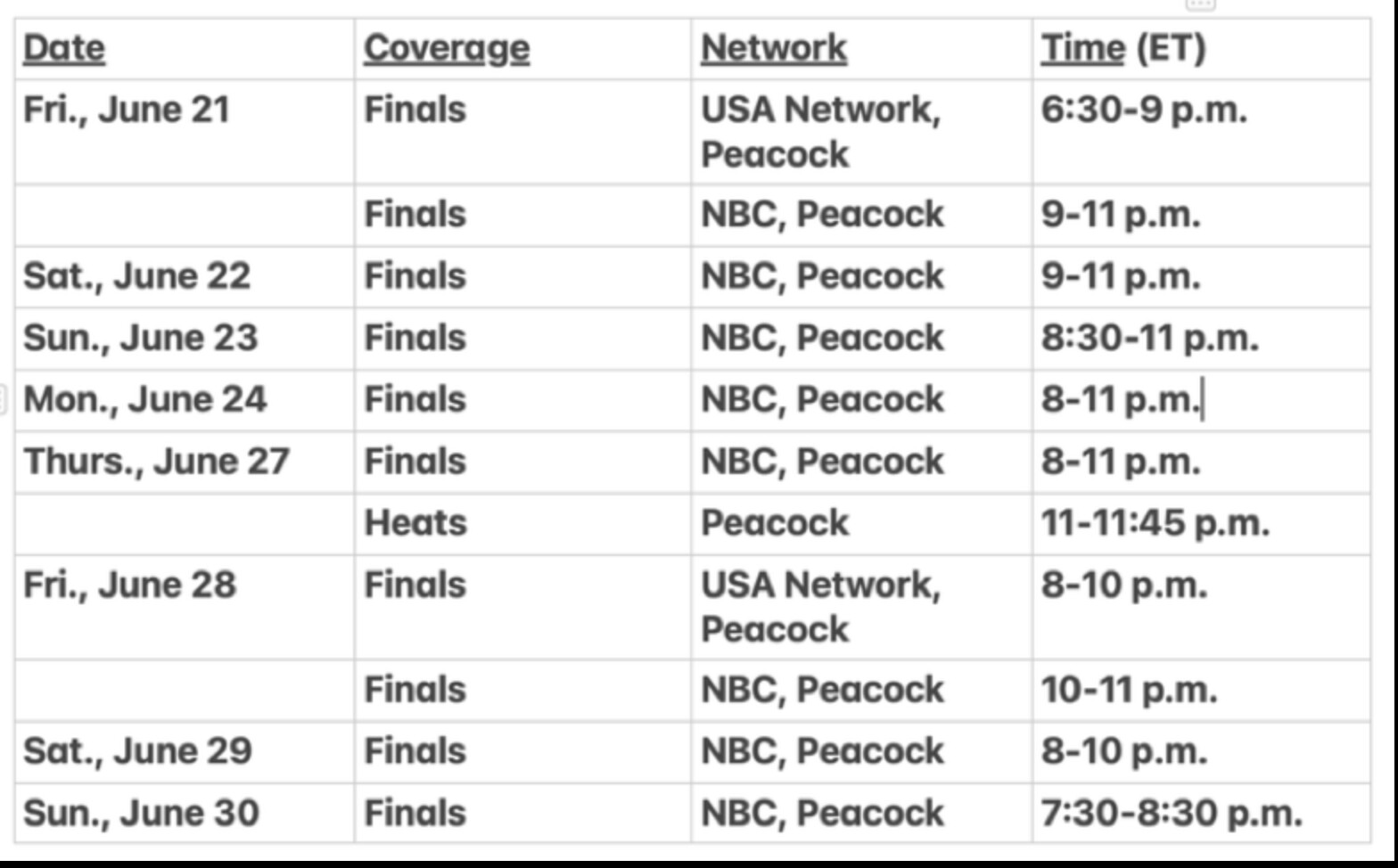

If you can’t make it to Eugene, you can watch every moment of every event (including preliminary events) via TV broadcasts and livestreams. The U.S. Olympic Trials will be broadcast live and via tape delay with 11 total broadcast segments on NBC, USA Network, and Peacock. All finals will air live on NBC during primetime and the entirety of the meet will be streamed on Peacock, NBCOlympics.com, NBC.com and the NBC/NBC Sports apps.

The Olympic Trials will be replete with young, rising stars. For example, the men’s 1500 is expected to be one of the most hotly contested events and the top three contenders for the Olympic team are 25 and younger: Yared Nuguse, 25, the American record holder in the mile (3:43.97), Cole Hocker, 23, who was the 2020 Olympic Trials champion, and Hobbs Kessler, 21, who turned pro at 18 just before racing in the last Olympic Trials. Sprinter Erriyon Knighton, who turned pro at age 16 and ran in the Tokyo Olympics at age 17, is still only 20 and already has two world championships medals under his belt. Plus, the biggest track star from the last Olympics, Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone, is aiming for her third Olympics and third Olympic gold (she won the 400-meter hurdles and was on the winning 4×400 relay in Tokyo), and she’s only 24.

Several young collegiate stars could earn their place on the U.S. team heading to Paris after successful results in the just-completed NCAA championships. Leading the way are double-NCAA champions McKillenzie Long, 23, a University of Mississippi senior who enters the trials ranked sixth in the world in the 100 (10.91) and first in the 200 (21.83), and Parker Valby, a 21-year-old junior at the University of Florida, who ranks fifth in the U.S. in the 5,000 meters (14:52.18) and second in the 10,000 meters (30:50.43). Top men’s collegiate runners include 5,000-meter runner Nico Young (21, Northern Arizona University), 400-meter runner Johnnie Blockburger (21, USC), and 800-meter runners Shane Cohen (22, Virginia) and Sam Whitmarsh (21, Texas A&M).

It’s very likely. Elle St. Pierre is the top-ranked runner in both the 1500 and the 5,000, having run personal bests of 3:56.00 (the second-fastest time in U.S. history) and 14:34.12 (fifth-fastest on the U.S. list) this spring. Although she’s only 15 months postpartum after giving birth to son, Ivan, in March 2023, the 29-year-old St. Pierre is running better and faster than ever. In January, she broke the American indoor record in the mile (4:16.41) at the Millrose Games in New York City, then won the gold medal in the 3,000 meters at the indoor world championships in Glasgow in March.

St. Pierre could be joined by two world-class sprinters. Nia Ali, 35, the No. 2 ranked competitor in the 100-meter hurdles and the 2019 world champion, is a mother of 9-year-old son, Titus, and 7-year-old daughter, Yuri. Quanera Hayes, 32, the eighth-ranked runner in the 400 meters, is the mother to 5-year-old son, Demetrius. Hayes, a three-time 4×400 relay world champion, finished seventh in the 400 at the Tokyo Olympics.

Meanwhile, Kate Grace, a 2016 Olympian in the 800 meters who narrowly missed making Team USA for the Tokyo Olympics three years ago, is back running strong at age 35 after a two-year hiatus during which she suffered from a bout of long Covid and then took time off to give birth to her son, River, in March 2023.

No, unfortunately, there are a few top-tier athletes who are hurt and won’t be able to compete. That includes Courtney Frerichs (torn ACL), the silver medalist in the steeplechase at the Tokyo Olympics in 2021; Alicia Monson (torn medial meniscus), a 2020 Olympian in the 10,000 meters, the American record holder in the 5,000 and 10,000 meters, and the fifth-place finisher in the 5,000 at last year’s world championships; and Joe Klekcer (torn adductor muscle), who was 16th in the Tokyo Olympics and ninth in the 2022 world championships in the 10,000. Katelyn Tuohy, a four-time NCAA champion distance runner for North Carolina State who turned pro and signed with Adidas last winter, is also likely to miss the trials due to a lingering hamstring injury. There is also some doubt about the status of Athing Mu (hamstring), the Tokyo Olympics 800-meter champion, who has yet to race in 2024.

Meanwhile, Emma Coburn, a three-time Olympian, 2017 world champion, and 10-time U.S. champion in the 3,000-meter steeplechase, broke her ankle during her season-opening steeplechase in Shanghai on April 27. She underwent surgery a week later, and announced at the time that she would miss the trials, but has been progressing quickly through her recovery. If both she and Frerichs miss the meet, it will leave the door wide open for a new generation of steeplers—including 2020 Olympian Valerie Constein, who’s back in top form after tearing her ACL at a steeplechase in Doha and undergoing surgery last May.

The U.S. earned 41 medals in track and field at the 2020 Paralympic Games in Tokyo—including 10 gold medals—which ranked second behind China’s 51. This year’s Paralympics will follow the Olympics from August 28-September 8 in Paris.

The 2024 U.S. Paralympic Trials for track and field will be held from July 18-20 at the Ansin Sports Complex in Miramar, Florida, and Paralympic stars Nick Mayhugh, Brittni Mason, Breanna Clark, Ezra Frech, and Tatyana McFadden are all expected to compete.

In 2021 at the Tokyo Paralympics, Mayhugh set two new world records en route to winning the 100 meters (10.95) and 200 meters (21.91) in the T-37 category, and also took the silver medal in the 400 meters (50.26) and helped the U.S. win gold and set a world record in the mixed 4×100-meter relay (45.52). Clark returns to defend her Paralympic gold in the T-20 400 meters, while McFadden, a 20-time Paralympic medalist who also competed on the winning U.S. mixed relay, is expected to compete in the T-54 5,000 meters (bronze medal in 2021).

Livestream coverage of the U.S. Paralympic Trials for track and field will be available on Peacock, NBCOlympics.com, NBC.com, and the NBC/NBC Sports app, with TV coverage on CNBC on July 20 (live) and July 21 (tape-delayed).

(06/15/24) Views: 196JP Flavin and Erin Mawhinney Victorious at 2024 Under Armour Toronto 10K

JP Flavin rang up Under Armour Toronto 10K organizers last week and asked if there was a place in the event for him. His eleventh-hour plea came just before the race limit of 7,500 was reached. Lucky for him.

The 25 year old New Jersey native showed his gratitude by front running his way to a victory in 29:20 and in the process pulling top Canadian Andrew Davies to a new personal best of 29:25. Third place overall went to Lee Wesselius in 29:49 and the third Canadian was Rob Kanko in 30 minutes flat.

“I am very thankful they let me in the race,” said Flavin, a member of the Brooks Hanson Project based in Rochester Hills, Michigan. “I did really well. I kept 4:40 miles throughout, which was my plan. It was fun.”

Midway through the race - the lead pack of seven runners reached 5K in 14:32 - he went to the front with the objective of breaking pre-race favorite Andrew Davies.

The Sarnia native has been training in Vancouver, where he is a law student at the University of British Columbia. Earlier this year, he ran a personal best 10,000m on the track (28:34.63) and also finished 2nd in the NAIA (collegiate) national championships in that event, which caught the attention of his peers.

“I knew if I stayed with Andrew to the last two kilometres, odds are he would outkick me,” Flavin added. “So a little before 5K, I started picking it up. I wanted to use that long hill [at the Canadian Legion] to come hard off it.”

"When I made my move and started feeling bad at mile five, I could hear from the crowd; they were screaming his name a little bit. So I knew I had to pay attention, stay on it, and not let up too much. I was able to grind and finish off strong.”

Davies was satisfied with his personal best. When Flavin made his move, he made an effort to maintain contact but could never close the gap.

"I was trying to cover it as best I could without risking blowing up at the end,” he revealed. “I couldn’t quite cover it. I stayed pretty close. I couldn’t catch him over the last two kilometres. He held that gap the whole way.”

Despite his earlier 10,000m success in the spring, Davies admitted he has lately been focusing on the 5,000m, the event he will race at the Canadian Olympic trials June 26-30 in Montreal.

While the men’s race had its drama, the women’s race saw the same podium finishers as in 2023, although Erin Mawhinney’s title defence was emphatic. The 28-year-old Hamilton, Ontario, nursing consultant won by 25 seconds over Salome Nyirarukundo.

Mahwinney’s 33:40 time was a pleasant surprise after she learned earlier in the year she was iron deficient.

“This was the first race since February that I haven’t felt dizzy, so this is the first one in a while that has felt like that,” says Mawhinney, who was greeted at the finish by her coach, two time Canadian Olympic marathoner, Reid Coolsaet.

Respect for her competitors was evident in her further comments.

“At no point was I confident of winning,” she declared. “Salome is so talented, and I knew there was a good chance she would come flying by but someone yelled at me with a kilometre to go that I had a good gap.

To run in the 33s, especially today, it's hotter and windier than last year, to run the same time as last year off much less training is great.”

Mawhinney also credited Toronto running coach Paddy Birch for helping her through the windy stretches along Lake Shore Boulevard.

“I owe my life to Paddy Birch. He was sort of breaking some of the wind and pacing up to about 8K, so I didn’t have to think quite as hard about it,” she added. “He is much faster than me, but I think he was going for an easy run. He was (pacing me) on purpose when he was talking to me.”

Nyirarukundo, who competed for Rwanda at the 2016 Olympics, now lives in Ottawa. She complained about having an upset stomach last night and into the race morning.

“I was a little bit tired. This morning I had a problemwith stomach. Even now, I have it,” she said with a smile, “so I was struggling even to finish, but because I am a fighter, I just tried to finish. It was not bad.”

“I appreciate the organisers; they are very, very good to the elites. It is really good and I enjoy the people (on the course) who are cheering.”

Rachel Hannah, now recovered from her 3rd place finish in the Ottawa Marathon, was 3rd in today’s race. Her time of 34:10, almost a minute faster than her 2023 finish, pleased her.

Once again, the Under Armour Toronto 10K served as the Canadian Masters’ championships, with Toronto’s Allison Drynan crossing the line first in the 45-49 age bracket, recording a time of 38:46. She finished just 8 seconds ahead of Miriam Zittel (40-44).

In the men’s master’s race, Bryan Rusche earned top honours with his 33:37 performance, and Brian Byrne of London, Ontario, finished next in 33:51.

Race director Alan Brookes was delighted with the sold-out event and pointed out that runners from nine provinces, two territories (the Yukon and the Northwest Territories), eighteen American states, and twenty countries enjoyed the day.

(06/15/24) Views: 174Paul Gains

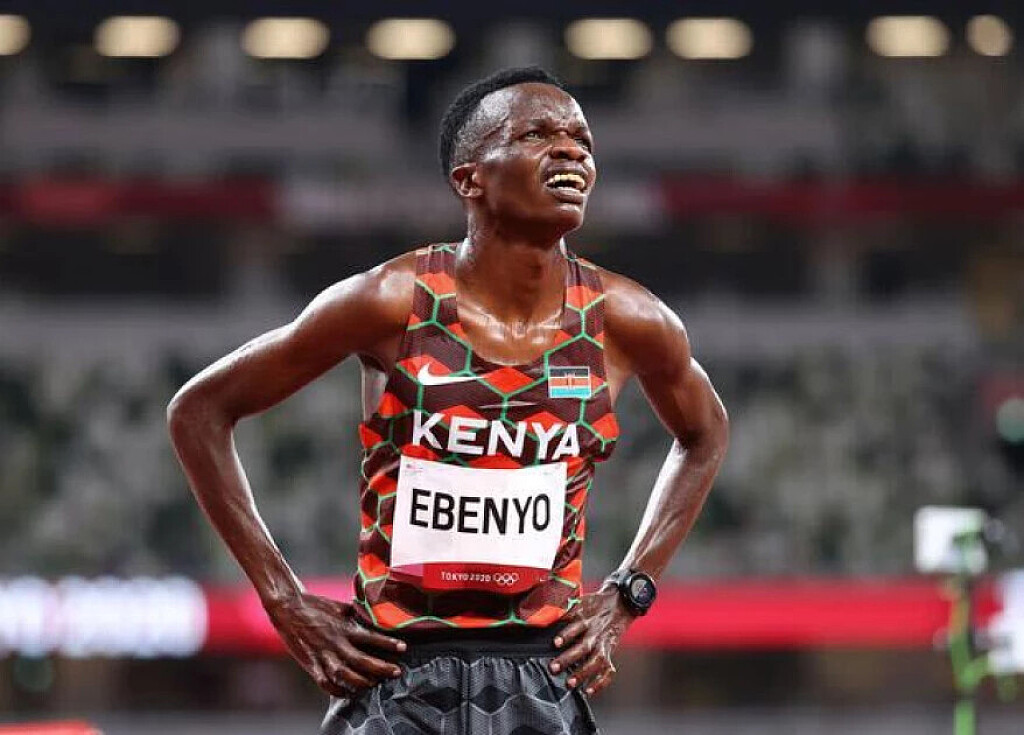

Why Daniel Simiu was not selected for the men's 10,000m for Paris Olympics

The selection panel has given a candid explanation of why Daniel Simiu was left out of the men's 10,000m team at the Paris 2024 Olympics.

The selection panel, led by Athletics Kenya Nairobi Chair Barnaba Korir has explained why world 10,000m silver medallist Daniel Simiu was snubbed from the men’s 10,000m team to the Paris 2024 Olympics.

As per the International Olympic Committee, the first two athletes to cross the finish line automatically qualify for the event with the third athlete being chosen by a panel of selectors.

Daniel Mateiko and Nicholas Kimeli finished first and second respectively with Bernard Kibet finishing third in the race. Simiu stumbled and fell, but he had to push himself and could only afford an eighth-place finish at the event.

Athletics Kenya president Jack Tuwei weighed in and explained that all athletes had a n equal chance of qualifying and they all arrived at Oregon in good time ahead of the race.

“We had a bit of a challenge with the travel documents but made sure that all the athletes who had been selected to go to Oregon to go there for the trials, Ebenyo included. There was a challenge but we made sure they all ended up there and they came back safely,” Tuwei said.

Meanwhile, Korir explained that Simiu arrived in Oregon, two days before the race, and had enough time to rest and also prepare himself for the race.

He added that there was tough competition since most athletes had qualified and they scratched their heads to come up with that decision.

“The preparation of the team to go to Oregon was very rigorous and the team that was selection process was done by the technical bench and the coaches who have been engaging with these athletes.

“Every athlete who had the opportunity to go and compete was contacted and nobody was left out in this process. The athletes who have been selected have all qualified and the 10,000m is currently limited and they have very few races in Europe.

“The decision was that most athletes had qualified and give them an opportunity to race and give them a feel of the track before the Paris Olympics. The selection had some problems but every athlete that was supposed to go there made it.

“Ebenyo made it there two days prior to the competition and he had an opportunity to rest and he had an advantage. All of them were okay and ready and the coaches prepared the athletes very well,” Korir said.

He added the committee had to check the performance of Kibet and Simiu and they realised that the former had also been performing well and there was no way he could have been left out.

He added that they did not want to name the team in Oregon since making the decision would be tough and they had to come back to the country to sit down and come up with a team.

“The committee realised that the third athlete had been performing well in other championships and there was no way he would be dropped. Selecting the men was very tough.

“We did not name the team since we had to sit down and rigorously decide on who was going to make the team. They made the decision according to many other reasons and the 10,000m was superb and the run was amazing,” Korir said.

Meanwhile, Milcah Chemos added that Kibet has shown impressive performances in previous races and he also played a huge role in Team Kenya winning silver at the World Championships in Budapest, Hungary.

She added that at the Prefontaine Classic, he fought hard for the third place and he deserves a chance. Chemos also believes that Kibet will not disappoint at the Paris 2024 Olympics.

“I was in Oregon and I witnessed all that was going on, so for the number three, we came up with them because of their performance. All athletes had an equal chance in Oregon and we all saw how Bernard did his best especially when the light had gone, he tried so had to close the gap.

“In Budapest, he also played a huge role in ensuring Kenya won the silver medal. It was hard to give out the number three but at least we sat, almost 10 of us, and we came up with the number three and I believe he deserves the position,” Chemos said.

(06/15/24) Views: 163Abigael Wuafula

Under Armour Diversity Series: Toronto’s Karla Del Grande

For multiple world record holder Karla Del Grande, age is just a state of mind.

Under Armour has teamed up with Canadian Running to produce the Under Armour Diversity Series—an exclusive feature content series designed to highlight and promote individuals and organizations who have demonstrated a commitment to grow the sport of running, support those who are underrepresented and help others. The series features stories and podcasts highlighting these extraordinary Canadians who are making a difference in their communities and on the national running scene.

Karla Del Grande has a few big goals: First, she wants to set another world record, and take home another medal at World Masters Athletics Championships this year. She wants to support her track team at Variety Village in Toronto. And she really, really wants masters athletes to know that the track is open to everyone.

After all, she didn’t find her way there until she was nearly 50 years old. Now, at 71, she’s become a poster-woman of the sport in Canada, thanks to her indomitable record-setting, her sheer dedication to the sport and her love of bringing new people in.

We met up on a snowy day in March at Variety Village, where she trains and runs with the Variety Village Athletics Club. I arrived late, just in time to catch the last 15 minutes of her workout class. Rather than let me stand on the sidelines, she jogged over, grabbed me by the hand, and pulled me into the group class, where athletes of all ages, shapes, sizes and abilities started doing rubber band work with a partner.

(“Everybody has the right to be part of a gym and have that social connection, no matter who you are, whether you’re a wheelchair user, or you have a mobility issue or anything else,” says Jill Ross Moreash, the class instructor, a former teacher and one of the fittest women I’ve ever seen, told me after class.)

Del Grande handed me a band after I shucked my winter coat and shoes. “You can be my partner,” she said. The workout was not easy.

This isn’t the first time Del Grande has helped bring someone into one of the workout classes. She recalls another snowy day, when she was heading into Variety Village for track practice, and she noticed an older woman standing next to her car, looking bereft. Del Grande started up a conversation, quickly learning the woman had recently been widowed and was hoping to find some conversation and community, but was overwhelmed about going into the gym. Del Grande shepherded her in, gave her a tour, helped her get signed up and brought her to class. She’s so well known as a woman who brings people into the community that she’s honoured on the wall at Variety Village.

That’s how she is on the track, as well: open and generous with her time (while still training to set world records, of course).

As a young girl, Del Grande was sporty, but she and her gym bestie (a race walker named Nicky Slovitt) both recall how, in gym class when they were in school, girls weren’t encouraged to run. That whole bit about our ovaries falling out if we sprinted or high jumped? Not a joke, if you were a gym teacher in the 60s, apparently. They believed it.

The track club at Variety Village isn’t just masters athletes; head coach Jamal Miller has created a vast community of runners ranging from pre-teens to the 70+ age group, with elite runners training alongside new track athletes. “We’re the best kept secret in Scarborough,” says assistant coach Katie Watkins. “We’re in a little bubble of what the world should be. Our track club is quite a diverse team. We cater to people of all abilities, from those living with disabilities to grassroots runners, starting off at age four, all the way up to world champions. The unique part about Jamal and how he trains is that if you’re interested, and you want to try it, he wants to work with you.”

Del Grande is at Variety Village early most days of the week. On Monday, she swims or aqua-jogs, then does weights. (“It’s a longevity thing,” she says. “You need to have balance between focusing on performance but also thinking toward longevity.”) Tuesday, she trains on the indoor track that runs around Variety VIllage’s main gym space. Wednesday is another weight session, this time in a class, and she runs again Thursday. Friday through Sunday depend on what her competition schedule looks like–when we met up on Wednesday, she was racing on Sunday, so the rest of the week was relatively easy, to prepare for that.

Del Grande found the track by accident–a work friend introduced her to running workouts on the track, and it grew from there. At the time, she did casual 5K and 10K runs and races, but she wouldn’t call herself a runner. Her friend brought her along to a track workout held by a local shop. “I really liked the short stuff,” she recalls. “We’d be doing track workouts and everybody else would be complaining that you had to go fast, and going around the track over and over was boring. But I loved it. And finally somebody said, ‘Well, why aren’t you racing it?'”

It was a lightbulb moment. “I thought adults just did road races,” she says. “It’s very hard to get out the information about the sprinting. But it exists–and there are adults doing high jump and shot put and all the other track and field sports, as well.”

She signed up, one thing led to another, and now, she’s one of the fastest female masters athletes in Canada.

“We always say that you’re never too old, you’re only too young to join Canadian Masters Athletics,” she laughs.

(06/14/24) Views: 162

Molly Hurford

Four super-speedy half-marathon workouts

These short but suffer-inducing sessions will have you charging to a PB with speed to spare.

Most of us would much rather bask in the sunshine with family and friends than hit the pavement for lactic-inducing, leg-burning repeats. However, to crush those speed goals, we need to squeeze in some tougher workouts. Luckily, these challenging sessions can be tweaked to fit your needs and abilities, and deliver a powerful punch without eating up all your popsicle-munching, beach volleyball-playing time.

When it comes to threshold pace, imagine the speed you’d hold for an hour-long race, or a bit faster than your half-marathon pace. If these training sessions seem too daunting or you are short on time, feel free to adjust by lengthening your recovery time and running fewer repeats.

Quick and punchy intervals

Option A

Warm up with 10 minutes of easy running.

Run 3-5 repeats of 4 x 1K at threshold pace, with 2 minutes of easy running between intervals for recovery.

Cool down with 10 minutes of easy running.

Option B

Warm up with 10 minutes of easy running.

Run 2 x 3K at threshold pace with 2 minutes of recovery between intervals.

Cool down with 10 minutes of easy running.

Speed progression

Warm up with a super easy 5-minute jog (your progression run begins at a very slow pace, so you can skip the warmup on this one, if you prefer).

Run a 10K progression run, starting with an easy pace and finishing at threshold pace. There are no hard-and-fast rules for this workout, so feel free to tweak it according to how you’re feeling and how hard you want to run. Just make sure you’re gradually getting faster as you run—you can judge this by either pace or effort.

Cool down with 10 minutes of very easy running.

Strong and steady

Slide this workout in when you want to do something challenging, but don’t want to completely drain the tank.

Warm up with 5-10 minutes of very easy running.

Run 8K steady state at marathon pace. This can be done by time or by effort, just aim to keep it consistent throughout. (If it’s a warm day, you may run more slowly than your ideal pace, and that’s OK.)

Cool down with 5-10 minutes of very easy running.

Follow any of these harder sessions with a very easy running day or a rest day, and make sure to hydrate before, during and after your workout, especially in warmer weather.

(06/18/24) Views: 161Keeley Milne

Dominic Ondoro and Elisha Barno will headline in the Grandma’s Marathon

Former champions and countrymen Dominic Ondoro and Elisha Barno will dominate the headlines in the Grandma’s Marathon men’s field, together having accounted for seven wins in the past nine years at this race.

Barno won for a record fifth time in his career last year, which came just one day after he was officially inducted into the Grandma’s Marathon Hall of Fame. Ondoro, meanwhile, still owns the event record of 2:09:06, a time he ran in 2014 that broke the longstanding record of Minnesotan Dick Beardsley.

The women’s field may be the most wide open of all this year’s events, with two-time Belarus Olympian Volha Mazuronak seemingly the pre-race favorite. She has top five finishes at both the Tokyo and Rio Olympics on her resume, as well as a runner-up finish earlier this year at the Los Angeles Marathon.

(06/15/24) Views: 157Running USA

Confident Faith Kipyegon ready to double at Paris Olympics after impressing on day two of Kenyan trials

Winning the 1500m at the Kenyan Olympic trials has boosted Faith Kipyegon's confidence and she has disclosed plans to double in the 1500m and 5000m at the Paris 2024 Olympics.

Three-time world 1500m champion Faith Kipyegon has impressed one more time on day two of the Kenyan Olympic trials, winning the 1500m and she has admitted it is a confidence booster for her to double in the 1500m and 5000m.

The double world champion clocked an impressive 3:53.98 to cross the finish line ahead of Nelly Chepchirchir who also qualified for the games, clocking 3:58.46 to cross the finish line.

Us-based runner Susan Ejore completed the podium, clocking an astonishing 4:00.22 to also qualify for the games.

Kipyegon was proud to share that the win is a confidence booster since she has been out with an injury and opening her season with a win and clocking such a fast time has encouraged her to double at the Olympics.

Before the race, her goal was to ensure she motivates others to join her in search for Olympic glory and she explained that her main aim was to ensure they run a faster race, something she was happy to have achieved and also pushed Chepchirchir and Ejore to hit the Olympic qualifying mark.

“I had not raced due to an injury but I thank God because I ran an incredible race today. I can declare that I’m going to double after this win because I have gained more confidence and I’m doing well. I’m ready to go and represent Kenya in the 1500m and 5000m.

“I see the team is very strong because we have worked together and we had talked before the race that we shall run a fast one. Today we wanted to run faster.

“After now, we are going to prepare for the Games and pray to God that we stay healthy and focus on the Olympics,” Kipyegon said after the race.

In her season opener at the Nyayo National Stadium on Friday, Kipyegon also outsmarted other world 10,000m record holder Beatrice Chebet to take the crown.

The two-time Olympic 1500m champion clocked 14:46.28 to cross the finish line as Chebet finished second in 14:52.55. Margaret Chelimo completed the podium, stopping the clock at 14:59.39.

(06/15/24) Views: 150Abigael Wuafula

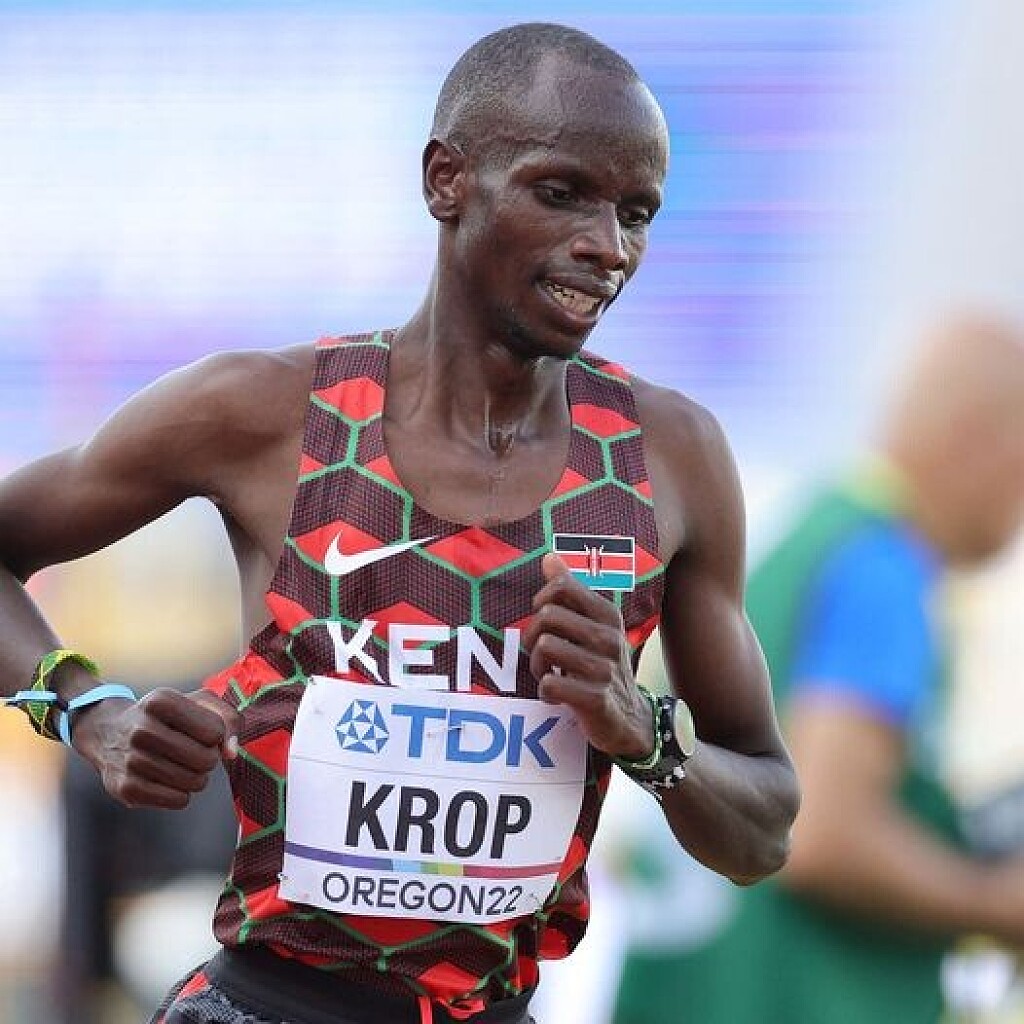

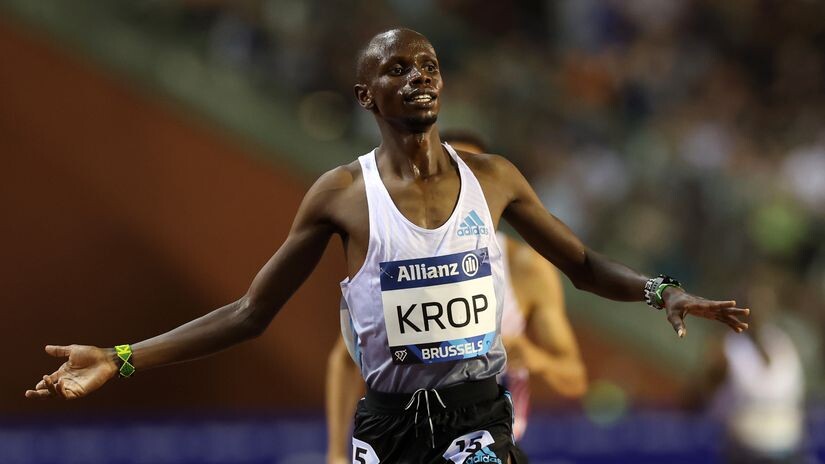

Ingebrigtsen, Cheptegei beware! Jacob Krop sets target after punching 5000m ticket to Olympic Games

Jacob Krop has sent a stark warning to Jakob Ingebrigtsen, Joshua Cheptegei, and other 5000m bound athletes after securing a ticket to the Olympic Games, following his relentless run at the Kenyan Olympic trials.

World 5000m bronze medallist Jacob Krop has promised to burn the midnight oil and ensure all the glory comes back to Kenya as he heads to the Paris 2024 Olympic Games.

Krop secured a direct ticket to the global showpiece, thanks to his relentless pursuit of greatness at the Olympic trials where he managed to finish second in the 5000m, clocking an impressive 13:27.54 to cross the finish line behind Ronald Kwemoi who won the race in 13:27.20. Edwin Kurgat completed the podium, clocking 13:27.75 to cross the finish line.

He will team up with Kwemoi and Krop believes they have the ability to silence serial winner Jakob Ingebrigtsen of Norway, defending champion Joshua Cheptegei and other opponents who have for long dominated the distance.

He disclosed that he moved to Japan and training there has been very effective since he has been able to work on certain areas of his training and he is now back.

“This is my first time to make the cut to the Olympic team and I want my fans to expect something good. To bring the medals back home, we shall practice teamwork and invest more time in training.

“Everything is possible and I know it’s not easy but we shall work hard in training and see how things work out. I went to Japan and my stay there had been great since they always give me ample time to even come back to Kenya and train,” he said.

Meanwhile, Kenya last won the Olympic gold medal over the distance at the 1988 Seoul Olympics where John Ngungi beat a strong field to claim the coveted prize.

During the delayed 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games, no Kenyan made it to the podium as Cheptegei claimed the top honours with Canadian Mohammed Ahmed finishing second in the race as Kenyan-born American Paul Chelimo completed the podium.

As they head to the Olympics, Krop is aware of the tough opposition but he is sure anything is possible if they work hard and embrace team work.

(06/15/24) Views: 149Abigael Wuafula

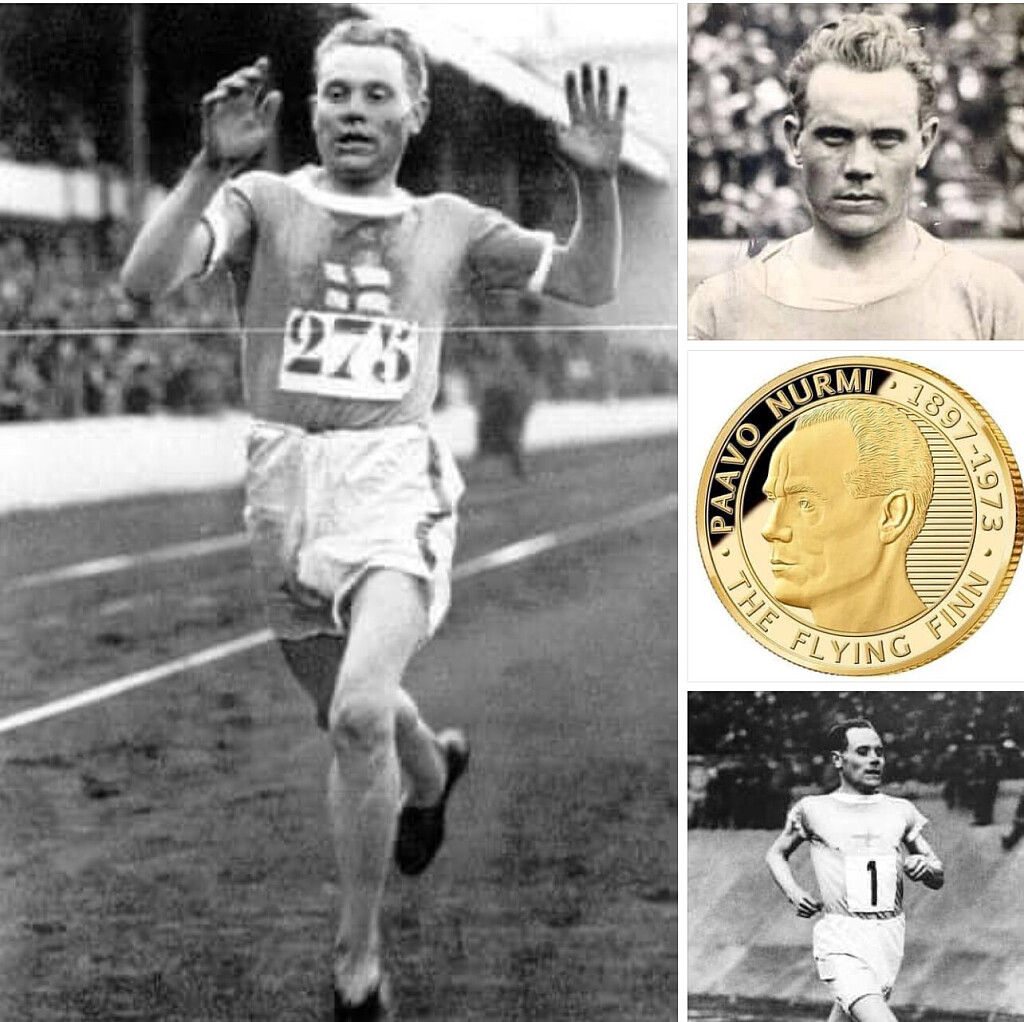

Times have improved so much over the years - Just a Quick Look back on the Flying Finn

94 years ago on Jun 9, 1930 – Finland’s Paavo Nurmi runs a World Record 6-mile clocking 29:36.4. Paavo was nicknamed the 'Flying Finn' as he dominated distance running in the early 20th century. Nurmi set 22 official world records at distances between 1500 metres and 20 kilometers, and won nine gold and three silver medals in his twelve events in the Olympic Games. At his peak, Nurmi was undefeated at distances from 800 meters upwards for 121 races. Throughout his 14-year career, he remained unbeaten in cross country events and the 10,000 meters.

(06/14/24) Views: 148Gary Cohen