Running News Daily

Top Ten Stories of the Week

6/15/2024

These are the top ten stories based on views over the last week.

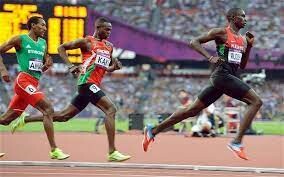

Daniel Mateiko explains why teaming up with Nicholas Kimeli guarantees Kenya an Olympic medal

Daniel Mateiko has given a reason why he believes teaming up with Nicholas Kimeli will earn Kenya the coveted gold medal.

The reigning Ras Al Khaimah Half Marathon champion Daniel Mateiko has explained why teaming up with Nicholas Kimeli guarantees Team Kenya an Olympic medal in the men’s 10,000m.

Mateiko and Kimeli got direct Olympic qualification following their impressive runs at the Prefontaine Classic, the Diamond League Meeting in Eugene, which also served as the Kenyan trials for the 10,000m.

The 25-year-old clocked a stunning world leading and personal best time of 26:50.81 to win the race as Kimeli finished second in a personal best time of 26:50.94. The third participant will be selected by a panel of selectors.

The 2022 Antrim Coast Half Marathon champion noted that he trains with Kimeli, something that places them at a greater level of winning the gold medal that was last won during the 1986 Olympic Games by Naftali Temu.

“Firstly, Kimeli and I train together, so I think we make a great team since we have been training together and we are going to Paris together, so we shall do well. It’s all about working on the confidence and believing in yourself that you can win.

“Actually, my journey in athletics has had ups and downs, sometimes you fail sometimes you succeed. Both of them are important in my career because when you fail, you grow,” he said.

The Kenyan also insisted that he will not change any of his training techniques in the build up to the global bonanza. He admitted that training with some of the greatest long-distance runners including Eliud Kipchoge and Geoffrey Kamworor has helped him gain confidence and helped him learn a lot of skills.

“I believe my preparation will be good and I have no plans of changing any program that I have been doing so I go and do my best there. I hope to do my best.

“It’s a great motivation for me to be training with great athletes like Eliud Kipchoge and Geoffrey Kamworor and I have learnt a lot of tactics and resilience from them,” Mateiko said.

(06/07/24) Views: 166Abigael Wuafula

TWENTY-ONE YEARS AGO, HE WAS INCARCERATED FOR LIFE. LAST YEAR, HE RAN THE NYC MARATHON A RADICALLY CHANGED MAN.

RAHSAAN ROUNDED THOMAS A CORNER. Gravel underfoot gave way to pavement, then dirt. Another left turn, and then another. In the distance, beyond the 30-foot wall and barbed wire separating him from the world outside, he could see the 2,500-foot peak of Mount Tamalpais. He completed the 400-meter loop another 11 times for an easy three miles.

Rahsaan wasn’t the only runner circling the Yard that evening in the fall of 2017. Some 30 people had joined San Quentin State Prison’s 1,000 Mile Club by the time Rahsaan arrived at the prison four years prior, and the group had only grown since. Starting in January each year, the club held weekly workouts and monthly races in the Yard, culminating with the San Quentin Marathon—105 laps—in November. The 2017 running would be Rahsaan’s first go at the 26.2 distance.

For Rahsaan and the other San Quentin runners, Mount Tam, as it’s known, had become a beacon of hope. It’s the site of the legendary Dipsea, a 7.4-mile technical trail from Mill Valley to Stinson Beach. After the 1,000 Mile Club was founded in 2005, it became tradition for club members who got released to run that trail; their stories soon became lore among the runners still inside. “I’ve been hearing about the Dipsea for the longest,” Rahsaan says.

Given his sentence, he never expected to run it. Rahsaan was serving 55 years to life for second-degree murder. Life outside, let alone running over Mount Tam all the way to the Pacific, felt like a million miles away. But Rahsaan loved to run—it gave him a sense of freedom within the prison walls, and more than that, it connected him to the community of the 1,000 Mile Club. So if the volunteer coaches and other runners wanted to talk about the Dipsea, he was happy to listen.

We’ll get to the details of Rahsaan’s crime later, but it’s useful to lead with some enduring truths: People can grow in even the harshest environments, and running, whether around a lake or a prison yard, has the power to change lives. In fact, Rahsaan made a lot of changes after he went to prison: He became a mentor to at-risk youth, began facing the reality of his violence, and discovered the power of education and his own pen. Along the way, Rahsaan also prayed for clemency. The odds were never in his favor.

To be clear, this is not a story about a wrongful conviction. Rahsaan took the life of another human being, and he’s spent more than two decades reckoning with that fact. He doesn’t expect forgiveness. Rather, it’s a story about a man who you could argue was set up to fail, and for more than 30 years that’s exactly what he did. But it’s also a story of navigating the delta between memory and fact and finding peace in the idea that sometimes the most formative things in our lives may not be exactly as they seem. And mostly, it’s a story of transformation—of learning to do good in a world that too often encourages the opposite.

RAHSAAN “NEW YORK” THOMAS GREW UP IN BROWNSVILLE, A ONE-SQUARE-MILE SECTION OF EASTERN Brooklyn wedged between Crown Heights and East New York. As a kid he’d spend hours on his Commodore 64 computer trying to code his own games. He loved riding his skateboard down the slope of his building’s courtyard. On weekends, he and his friends liked to play roller hockey there, using tree branches for sticks and a crushed soda can for a puck.

Once a working-class Jewish enclave, Brownsville started to change in the 1960s, when many white families relocated to the suburbs, Black families moved in, and city agencies began denying residents basic services like trash pickup and streetlight repairs. John Lindsay, New York’s mayor at the time, once referred to the area as “Bombsville” on account of all the burned-out buildings and rubble-filled empty lots. By 1971, the year after Rahsaan was born, four out of five families in Brownsville were on government assistance. More than 50 years later, Brownsville still has a poverty rate close to 30 percent. The neighborhood’s credo, “Never ran, never will,” is typically interpreted as a vow of resilience in the face of adversity. For some, like Rahsaan, it has always meant something else: Don’t back down.

The first time Rahsaan didn’t run, he was 5 or 6 years old. He had just moved into Atlantic Towers, a pair of 24-story buildings beset with rotting walls and exposed sewer pipes that housed more than 700 families. Three older kids welcomed him with their fists. Even if Rahsaan had tried to run, he wouldn’t have gotten far. At that age, Rahsaan was skinny, slow, and uncoordinated. He got picked on a lot. Worse, he was light-skinned and frequently taunted as “white boy.” The insult didn’t even make sense to Rahsaan, whose mother is Black and whose father was Puerto Rican. “I feel Black,” he says. “I don’t feel [like] anything else. I feel like myself.”

Rahsaan hated being called white. It was the mid-1970s; Roots had just aired on ABC, and Rahsaan associated being white with putting people in chains. Five-Percent Nation, a Black nationalist movement founded in Harlem, had risen to prominence and ascribed godlike status to Black men. Plus, all the best athletes were Black: Muhammad Ali. Reggie Jackson. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. In Rahsaan’s world, somebody white was considered physically inferior.

Raised by his mother, Jacqueline, Rahsaan never really knew his father, Carlos, who spent much of Rahsaan’s childhood in prison. In 1974, Jacqueline had another son, Aikeem, with a different man, and raised her two boys as a single mom. Carlos also had another son, Carl, whom Rahsaan met only once, when Carl was a baby. Still, Rahsaan believed “the myth,” as he puts it now, that one day Carlos would return and relieve him, his mom, and Aikeem of the life they were living. Jacqueline had a bachelor’s degree in sociology and worked three jobs to keep her sons clothed and fed. She nurtured Rahsaan’s interest in computers and sent him to a parochial school that had a gifted program. Rahsaan describes his family as “upper-class poor.” They had more than a lot of families, but never enough to get out of Brownsville, away from the drugs and the violence.

Some traumas are small but are compounded by frequency and volume; others are isolated occurrences but so significant that they define a person for a lifetime. Rahsaan remembers his grandmother telling him that his father had been found dead in an alley, throat slashed, wallet missing. Rahsaan was 12 at the time, and he understood it to mean his father had been murdered for whatever cash he had on him—maybe $200, not even. Now he would never come home.

Rahsaan felt like something he didn’t even have had been taken from him. “It just made me different, like, angry,” he says. By the time he got to high school, Rahsaan resolved to never let anyone take anything from him or his family again. “I started feeling like, next time somebody tryin’ to rob me, I’m gonna stab him,” he says. He started carrying a knife, a razor, rug cutters—“all kinds of sharp stuff.” Rahsaan never instigated a fight, but he refused to back down when threatened or attacked. It was a matter of survival.

The first time Rahsaan picked up a gun, it was to avenge his brother. Aikeem, who was 14 at the time, had been shot in the leg by a guy in the neighborhood who was trying to rob him and Rahsaan. A few months later, Rahsaan saw the shooter on the street, ran to the apartment of a drug dealer he knew, and demanded a gun. Rahsaan, then 18, went back outside and fired three shots at the guy. Rahsaan was arrested and sent to Rikers Island, then released after three days: The guy he’d shot was wanted for several crimes and refused to testify against Rahsaan.

By day, Rahsaan tried to lead a straight life. He graduated from high school in 1988 and got a job taking reservations for Pan Am Airways. He lost the job after Flight 103 exploded in a terrorist bombing over Scotland that December, and the company downsized. Rahsaan got a new job in the mailroom at Debevoise & Plimpton, a white-shoe law firm in midtown Manhattan. He could type 70 words a minute and hoped to become a paralegal one day.

Rahsaan carried a gun to work because he’d been conditioned to expect the worst when he returned to Brownsville at night. “If you constantly being traumatized, you constantly feeling unsafe, it’s really hard to be in a good mind space and be a good person,” he says. “I mean, you have to be extraordinary.”

After high school, some of Rahsaan’s friends went to Old Westbury, a state university on Long Island with a rolling green campus. He would sometimes visit them, and at a Halloween party one night, he got into a scrape with some other guys and fired his gun. Rahsaan spent the next year awaiting trial in county jail, the following year at Cayuga State Prison in upstate New York, and another 22 months after that on work release, living in a halfway house in Queens. He got a job working the merch table for the Blue Man Group at Astor Place Theater, but the pay wasn’t enough to support the two kids he’d had not long after getting out of Cayuga.

He started selling a little crack around 1994, when he was 24. By 27 he was dealing full-time. He didn’t want to be a drug dealer, though. “I just felt desperate,” he says. Rahsaan had learned to cut hair in Cayuga, and he hoped to save enough money to open a barbershop.

He never got that opportunity. By the summer of 1999, things in New York had gotten too hot for Rahsaan and he fled to California. For the first time in his 28 years, Rahsaan Thomas was on the run.

EVERY RUNNER HAS AN ORIGIN STORY. SOME START IN SCHOOL, OTHERS TAKE UP RUNNING TO IMPROVE their health or beat addiction. Many stories share common themes, if not exact details. And some, like Rahsaan’s, are absolutely singular.

Rahsaan drove west with ambitions to break into the music business. He wanted to be a manager, maybe start his own label. His new girlfriend would join him a week later in La Jolla, where they’d found an apartment, so Rahsaan went first to Big Bear, a small town deep in the San Bernardino Mountains 100 miles east of Los Angeles. It’s where Ryan Hall grew up, and where he discovered running at age 13 by circling Big Bear Lake—15 miles—one afternoon on a whim. Hall has recounted that story so many times that it’s likely even better known than the American records he would go on to set in the half and full marathons.

Rahsaan didn’t know anything about Ryan Hall, who at the time was just about to start his junior year at Big Bear High School and begin a two-year reign as the California state cross-country champion. He didn’t even know there was a lake in Big Bear. Rahsaan went to Big Bear to box with a friend, Shannon Briggs, a two-time World Boxing Organization heavyweight champion.

Briggs and Rahsaan had grown up together in Atlantic Towers. As kids they liked to ride bikes in the courtyard, and later they went to the same high school in Fort Greene. But Briggs’s mom had become addicted to drugs by his sophomore year, and they were evicted from the Towers. Briggs and Rahsaan lost touch. Briggs began spending time at a boxing gym in East New York; often he’d sleep there. He had talent in the ring. People thought he might even be the next Mike Tyson, another native of Brownsville who was himself a world heavyweight champ from 1986 to 1989.

Briggs went pro in 1991, and by the end of that decade he was earning seven figures fighting guys like George Foreman and Lennox Lewis. Rahsaan was at those fights. The two had reconnected in 1996, when Rahsaan was trying to rebuild his life after prison and Briggs’s boxing career was on the rise. In August 1999, Briggs was gearing up to fight Francois Botha, a South African known as the White Buffalo, and had decamped to Big Bear to train. “He was like, ‘Yo, come live with me, bro,’” Rahsaan recalls.

Briggs was running three miles a day to increase his stamina. His route was a simple out-and-back on a wooded trail, and on one of Rahsaan’s first days there, he decided to join him. Rahsaan hadn’t done so much as a push-up since getting out of prison, but he wanted to hang with his friend. Briggs and his training partners set off at their usual clip; within a few minutes they’d disappeared from Rahsaan’s view. By the time they were doubling back, he’d barely made it a half mile.

Rahsaan never liked feeling physically inferior. So back in La Jolla, he started running a few times a week, going to the gym, whatever it took. Before long he was up to five miles. And the next time he ran with Briggs, he could keep up. After that, he says, “Running just became my thing.”

FOR YEARS, RAHSAAN HAD BUCKED AT TAKING RESPONSIBILITY for the murder that sent him to prison. The other guys had guns, too, he insisted. If he hadn’t shot them, they’d have shot him. It was self-defense.

In the moment, he had no reason to think otherwise. It was April 2000. A friend had arranged to sell $50,000 worth of weed, and Rahsaan went along to help. They met in the parking lot of a strip mall in L.A., broad daylight. The buyers brought guns instead of cash, things went sideways, and, in a flash of adrenaline, Rahsaan used the 9mm he’d packed for protection, killing one man and putting the other in critical condition. He was 29 and had been in California eight months.

After awaiting trial for three years in the L.A. County jails, Rahsaan was sentenced to 55 years to life. But for the crushing finality of it, the grim interminability, the prospect of never seeing the outside world again, he was on familiar ground. Even Brownsville had been a kind of prison—one defined, as Rahsaan puts it now, by division and neglect, a world unto itself that societal forces made nearly impossible to escape. He was used to life inside.

Rahsaan spent the next 10 years shuttling between maximum security facilities, the bulk of those years at Calipatria State Prison, 30 miles from the Mexican border. By the time he got to San Quentin, he was 42.

As part of the prison’s restorative justice program, Rahsaan met a mother of two young men who’d been shot, one killed and the other critically injured. Her pain, her dignity, her ability to forgive her sons’ shooters prompted Rahsann to reflect on his own crime. “It made me feel like, damn, I did this to his mother,” he says. “I did this to my mother. You don’t do that to Black mothers. They go through so much.”

ABOUT 2 MILLION PEOPLE ARE INCARCERATED IN THE UNITED States today, roughly eight times as many as in the early 1970s. Nearly half of them are Black, despite Black Americans representing only 13 percent of the U.S. population.

This disparity reflects what the legal scholar and author Michelle Alexander calls “the new Jim Crow,” an invisible system of oppression that has impeded Black men in particular since the days of slavery. In her book of the same title, Alexander unpacks 400 years of policies and social attitudes that have created a society in which one in three Black males will be incarcerated at some point in their lives, and where even those who have been paroled often face a lifetime of discrimination and disenfranchisement, like losing the right to vote. If you hit a wall every time you try to do something, are you really free? More than half of the people released from U.S. jails and prisons return within three years.

After Rahsaan got out of Cayuga back in 1992, with a felony on his permanent record, he’d had trouble doing just about anything legit: renting an apartment, finding a decent job, securing a loan. Though he’d paid for the Mercedes SUV he drove to California, the lease was in his girlfriend’s name. Selling crack had provided financial solvency, and his success in New York made him feel invincible. One weed deal in California seemed easy enough. But he wasn’t naive. Rahsaan packed a gun, and if he felt he had to use it, he would.

Today Rahsaan feels deep remorse for what transpired from there. But back then he saw no other way. “When we have a grievance, we hold court in the street,” he says of growing up in the Brownsville projects. “There’s no court of law, there’s no lawsuits.” Even while incarcerated, Rahsaan continued to meet threats with violence. But he also found that in prison, as in Brownsville, respect was temporary. “If you stab somebody, people leave you alone,” he says. “But you gotta keep doing it.”

Not long after Rahsaan got to Calipatria, around 2003 or 2004, an older man named Samir pulled him aside. “Youngster, there’s nobody that you can beat up that’s gonna get you out of prison,” Rahsaan remembers Samir saying. “In fact, that’s gonna make it worse.” Rahsaan thought about Muhammad Ali, how he would get his opponents angry on purpose so they’d swing until they wore themselves out. He realized that when you’re angry, you’re not thinking clearly or moving effectively. You’re not responding; you’re reacting.

The next time Rahsaan saw Samir was in the yard at Calipatria. They were both doing laps, and the two men started to run together. Rahsaan told Samir about the impact his words had on him, how they helped him see he’d always let “somebody else’s hangup become my hangup, somebody else’s trauma become my trauma.” Each time that happened, he realized, he slid backward.

Rahsaan began exploring various religions. He liked how the men in the Muslim prayer group at Calipatria encouraged him to think about his past, and the way they talked about God’s plan. He thought back to that day in April 2000 and came to believe that God would have gotten him out of that situation without a gun. “If I was meant to die, I was meant to die,” he says. “If I’m not, I’m not.” He started to see confrontations as tests. “I stopped feeding into the negativity and started passing the test, and I’ve been passing it consistently since,” he says.

CLAIRE GELBART PLACED HER BELONGINGS IN A PLASTIC TRAY AND WALKED THROUGH THE METAL detectors at the visitors’ entrance at San Quentin. She crossed the Yard to the prison’s newsroom. It was late fall of 2017, and Gelbart had started volunteering with the San Quentin Journalism Guild, an initiative to teach incarcerated people the fundamentals of newswriting and interviewing techniques.

Historically infamous for housing people like Charles Manson and Sirhan Sirhan, the man convicted of killing Robert Kennedy, and for having the only death row for men in California, San Quentin has in recent years instituted reforms. By the time Rahsaan arrived, the facility was offering dozens of programs, had an onsite college, and granted some of the individuals housed there considerable freedom of movement. Hundreds of volunteers pass through its gates every year.

Rahsaan was in the newsroom working on a story for the San Quentin News, where he was a staff writer. Gelbart and Rahsaan started to chat, and within minutes they were bonding over running. They talked about the San Quentin Marathon—in which Rahsaan was proud to have placed 13th out of 13 finishers in 6 hours, 12 minutes, and 23 seconds—and Gelbart’s plans to run her first half marathon that spring. “It was like I lost all sense of place and time,” Gelbart says, “like I could have been in a coffee shop in San Francisco talking to someone.”

In weekly visits over the next year, Gelbart and Rahsaan talked about their families, their hopes for the future. Gelbart had just graduated from Tufts University with dreams of being a writer. Rahsaan was working toward a college degree, writing for numerous outlets like the Marshall Project and Vice, and learning about podcasting and documentary filmmaking. In 2019, when Gelbart was offered a job in New York, she told Rahsaan she felt torn about leaving—they’d become close friends. They made a pact that if Rahsaan ever got out of prison, they would run the New York City Marathon together. “We couldn’t think of a better thing to celebrate him coming home,” Gelbart says.

When Rahsaan was sentenced, he still had hope for a successful appeal. But when his appeal was denied in 2011, he realized he was never going home. His parole date was set for 2085.

At the time, though, the political appetite for mass incarceration was starting to shift. Gray Davis, who was governor of California from 1999 to 2003, had never granted a single pardon; and his successor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, granted only 15. Then, between 2011 and 2019, Governor Jerry Brown pardoned or commuted the sentences of more than 1,300 people. Studies show that the recidivism rate among those who had been serving life sentences is less than 5 percent in a number of states, including California. And according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice, 98 percent of people convicted of homicide who are released from prison do not commit another murder.

In the fall of 2018, Governor Brown approved Rahsaan for commutation, but it was now up to his successor, Gavin Newsom, to follow through. And until a release date was set, there were no guarantees.

Back at San Quentin, Rahsaan was busier than ever. He was working on his fourth film, Friendly Signs, a documentary funded by the Marshall Project and the Sundance Institute; it was about fellow 1,000 Mile Club member Tommy Lee Wickerd’s efforts to start an ASL program to aid a group of deaf and hard-of-hearing newcomers to the prison. He had recently been named chair of the San Quentin satellite chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists and became a cohost and coproducer of Ear Hustle, a popular podcast about life in San Quentin that in 2020 was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize. He was also sketching out plans for a nonprofit, Empowerment Ave, to build connections to the outside world for other incarcerated writers and artists and to advocate for fair compensation. And after five years, he was just one history class away from getting his associate’s degree from Mount Tamalpais College.

In January 2020, Rahsaan began his final semester, eager to don his cap and gown that June. MTC always organized a festive graduation ceremony in the prison’s visiting room, inviting families, friends, students, and staff. Then COVID-19 hit. Lockdown. All classes canceled until further notice. The 1,000 Mile Club suspended workouts and races as well, its 70-plus members scattering throughout the prison, not sure when or if they’d ever get together again. Covid would officially kill 28 people at San Quentin and make many more very ill. College graduation, let alone races in the Yard and parole hearings, would have to wait.

For the first time since arriving at San Quentin, Rahsaan felt claustrophobic in his 4-by-10-foot cell. He couldn’t work on his films or go to the newsroom. All he could do was read and write, alone. After George Floyd was murdered that May, Rahsaan fell into a depression. He remembered something Chadwick Boseman had said in a 2018 commencement speech at Howard University: “Remember, the struggles along the way shape you for your purpose.”

Rahsaan decided his purpose was to write. Outside journalists couldn’t enter the prison during the pandemic, but their publications were thirsty for prison Covid stories. Rahsaan saw an opportunity. Between June 2020 and February 2023, he published 42 articles, and thanks to Empowerment Ave, he knew what those articles were worth. As a writer for the San Quentin News, Rahsaan earned $36 a month; those 42 articles for external publications netted him $30,000.

DOZENS OF PEOPLE GATHERED OUTSIDE SAN QUENTIN’S GATES. IT WAS A FRIGID MORNING IN EARLY February 2023; the sun hadn’t yet risen. Among those assembled were two cofounders of Ear Hustle, Earlonne Woods and Nigel Poor, along with executive producer Bruce Wallace, recording equipment in hand. A procession of white vans, each carrying one or two men, arrived one by one. After three or four hours, the air had warmed to a balmy 60 degrees. Another van pulled up, Rahsaan got out, and the crowd erupted. Nearly 23 years after he’d been sentenced to 55 years to life, Rahsaan Thomas had been released.

Rahsaan got into a Hyundai sedan and was soon headed away from San Quentin. Wallace sat in the back, recording Rahsaan seeing water, mountains, and a highway from the front seat of a car for the first time in decades. “I feel like I’m escaping,” he joked. “Is anybody chasing us? This is amazing. This is crazy.”

Rahsaan called his mom, who wasn’t able to make it to California for his release.

“Hey, Ma, it’s really real,” he said, breathless with joy. “I’m free. No more handcuffs.”

Jacqueline’s exuberance can be heard in her laughter, her curiosity about what his first meal would be (steak and French toast), and her motherly rebuke of his plan to buy a Tesla.

“You ain’t been drivin’ in a while and I know you ain’t the best driver in the world,” she teased.

Rahsaan moved into a transitional house in Oakland and wasted no time adjusting to life in the 21st century. He got an iPhone, and a friend gave him a crash course in protecting himself from cyberattacks. He’s almost fallen for a few. “There’s some rough hoods on the internet,” he jokes. Earlonne Woods, who was paroled in 2018, and others taught Rahsaan how to use social media. He opened Instagram and Facebook accounts and worked on his own website, rahsaannewyorkthomas.com, which a friend had built for him while he was in San Quentin to promote his creative projects, Empowerment Ave, and even a line of merch.

Despite all the excitement and chaos, Rahsaan never forgot about the pact he’d made with Claire Gelbart. He found her on Facebook and sent a simple, two-line message: “Start training. We have a marathon to run.”

IN LATE MARCH, SIX WEEKS AFTER HIS RELEASE, RAHSAAN FLEW TO NEW YORK CITY. IT WAS THE FIRST time he’d been home in nearly a quarter century, and he hadn’t flown since before 9/11. The security protocols at SFO reminded him more of prison than of the last time he’d been in an airport. Actually, “it was worse than prison,” he jokes. They confiscated his jar of honey.

The changes to his home borough were no less surprising. He’d come to New York to take work meetings, see family, and catch a Nets game at Barclays Center in downtown Brooklyn. Rahsaan barely recognized Barclays; it had been a U-Haul lot the last time he was there, and skyscrapers now towered over Fulton Mall, where he used to buy Starter jackets at Dr. Jay’s and Big Daddy Kane tapes at the Wiz.

He met up with Gelbart on Flatbush Avenue, where come November they’d be just hitting mile 8 of the New York City Marathon. They hadn’t been allowed to touch at San Quentin and weren’t sure how to greet each other on the outside. “It was weird at first, because I was like, do we hug?” Gelbart recalls. But the awkwardness faded fast, and as they walked, Gelbart saw a different side of Rahsaan. “He seemed so much more relaxed,” she says. “Much happier, much lighter.”

Back in 1985, just a few blocks from where Rahsaan and Gelbart walked now, Rahsaan, his brother Aikeem, and his friend Troy had been on their way home from the Fulton Mall when out of nowhere, about a dozen guys rolled up on them. They started beating on Troy and, for a minute, left Rahsaan and Aikeem alone. Images of his father, throat slashed, flashed through Rahsaan’s mind. He pulled a rug cutter out of his pocket, ran to the smallest guy in the group, and jabbed it into the back of his head. “They looked at me like they were gonna kill me,” Rahsaan says. He threw the blade to the ground, slid his hand inside his coat, and held it there. “Y’all wanna play? We gonna play,” he said. The bluff worked; the guys ran. It was the first time Rahsaan had ever stabbed someone.

Change sometimes occurs gradually, and then all at once. That was a different Brooklyn, a different Rahsaan. He began to confront his own violence when he had met Samir some 20 years before, and continued to do so through his studies, his faith, his work in restorative justice, and his own writing. But the origin of his tendency toward violence, the death of his father, remained firmly rooted in his psyche. Then, in 2017, Rahsaan spoke for the first time with his estranged half-brother, Carl.

Carl had read Rahsaan’s work, and asked why he always said their father had been murdered.

“That’s what grandma told me,” Rahsaan said.

“But he wasn’t murdered,” Carl told him. “He killed himself.”

And it wasn’t in 1982, as Rahsaan remembered, but in 1985—the same year Rahsaan started carrying blades.

Rahsaan didn’t believe it until Carl sent him a copy of the suicide note. Even then he remained in shock. “To think I justified violence, treating robbery like a life-or-death situation, over a lie,” he says. Jacqueline was as surprised as Rahsaan to learn the truth of Carlos’s death. He never seemed troubled or depressed to her when they were together, but, “You can’t really read people,” she says. “You don’t know.”

Rahsaan still can’t account for why his grandmother told him what she did, nor for the discrepancy between his memory and the facts. Regardless, after more than 30 years, Rahsaan was finally able to let go of the one trauma that had calcified into an instinct to kill or be killed. And he has no intention of dredging it back up.

THE FASTEST RUNNER IN THE 1,000 MILE CLUB’S HISTORY IS MARKELLE “THE GAZELLE” TAYLOR, WHO was paroled in 2019 and went on to run 2:52 in the 2022 Boston Marathon. Rahsaan is the slowest. At San Quentin, he was often the last one to finish a race, but that wasn’t the point—he liked being out in the Yard with the guys. It gave him a sense of belonging, and not just to the 1,000 Mile Club, but to the running community beyond.

Like every other 1,000 Miler who gets released from San Quentin, Rahsaan had a rite of passage to conquer. On Sunday morning, May 7, 2023, he met a handful of other runners from the club and a few volunteer coaches in Mill Valley. After a decade of gazing up at Mount Tam from the Yard as he completed one 400-meter loop after another, Rahsaan was finally about to run over the mountain all the way to the Pacific.

The runners did a few final stretches, wished one another luck, and started to run. Almost immediately they had to climb some 700 stairs, many made of stone, and the course only got more treacherous from there. Uneven footing, singletrack paths, and 2,000-plus feet of elevation all conspire to make the Dipsea notoriously difficult. The giant redwoods and Douglas firs along the course were lost on Rahsaan; he never took his eyes off the ground.

One of the coaches, Jim Maloney, stayed with Rahsaan as his guide, and to help him if he slipped or fell. Markelle Taylor came too, but said he’d meet them in Stinson Beach. He knew how dangerous the trail was, Rahsaan says, and had vowed to never run it again. After his own initiation, Rahsaan decided that he, too, would never do it again. “I’ve been shot at,” he says. “I’ve been in physical danger. I don’t want to revisit danger.”

Rahsaan now logs most of his miles on a treadmill because of knee issues, but on occasion he ventures out to do the 3.4-mile loop around Lake Merritt, a lagoon in the heart of Oakland. He decided to use the New York City Marathon to raise money for Empowerment Ave, and to accept donations until he crossed the finish line in Central Park. Gelbart wrote a training plan for him and got him a new pair of shoes. In prison, Rahsaan had run in the same pair of Adidas for three years, and he was excited to learn about the maximalist shoe movement. Gelbart tried to interest him in Hokas, but Rahsaan thought they were ugly. He wanted Nikes.

In June, Gelbart went to the Bay Area to visit family and met Rahsaan for a six-mile run around Lake Merritt. As they looped the lake at a conversational 11:30 pace, they talked about work, relationships, and, of course, the New York City Marathon. Rahsaan was disappointed to learn that he would probably not be the last person to finish. (He still holds the record for the slowest San Quentin Marathon in its 15-year history, and he hopes no one ever beats it.) Besides, the more time he spent on the course in New York, he figured, the longer people would have to donate to Empowerment Ave.

On Sunday, November 5, Gelbart and Rahsaan made their way to Staten Island. Waiting at the base of the Verrazzano Bridge, Gelbart recorded Rahsaan singing along to Frank Sinatra’s “New York, New York” for Instagram, and captioned the video “back where he belongs.” They documented much of their race as they floated through Brooklyn, Queens, Manhattan, and the Bronx: greeting friends along the course, enjoying a lollipop on the Queensboro Bridge, beaming even as their pace slowed from 11:45 per mile for the first 5K to 16:30 for the last. Rahsaan finished in six hours, 26 minutes, and 21 seconds, placing 48,221 out of 51,290 runners. The next day, he sent me a text: “The marathon was pure love.” What’s more, he received more than $15,000 in donations for Empowerment Ave, enough to start a writing program at a women’s prison in Texas.

Every runner has an origin story. Every runner finds a reason to keep going. At Calipatria, Rahsaan liked to joke that he ran because if an earthquake ever came along and brought down the prison’s walls, he needed to be in shape so he could escape and run to Mexico. In San Quentin, he ran for the community. Today he has a new reason. “I heard that running extends your life by 10 years,” he says, “and I gave away 22.” Now that he’s out, his motivation has never been higher. He has so much to do.

(06/09/24) Views: 148How to prepare for a marathon, according to official Comrades coach

John Perlman speaks with Lindsey Parry, Official Comrades Marathon Coach.

Running a marathon is a massive task, and far more goes into it than just the actual running.

In the final two days of a race, there are a few things a runner needs to do for the best outcome.

Eat at the right time:

Your biggest main meal leading up to the race should be two nights before the race.

The night before you should not eat anything too heavy.

Get your sleep:

The few nights before running a marathon you should get a full night’s sleep.

Many people will not sleep that well the night before, so Parry says you should be sure to rest well two or three nights before.

“Night two and night three, those are really the nights to try and get yourself a good night’s sleep.”

- Lindsey Parry, Official Comrades Marathon Coach

Make a realistic race plan:

Before you start running you should look at what you have done with previous races or training, and plan accordingly.

This year the first 50km have a significant amount of climbing, so you should be conservative in this time.

Stay positive:

It can be easy to get overwhelmed by bad thoughts, especially if you have recently had a bad run.

Parry says you should just enjoy the day for what it is and focus on the run ahead.

(06/07/24) Views: 147Keely Goodall

Five signs that you need new running shoes

Each year, warm weather brings out many new runners to run clubs or to start the sport. When you’re new to any sport, you work with the equipment you have. Running shoes are more than just footwear; they play a pivotal role in helping you become a better runner and chase your goals. Wearing worn-out shoes can lead to discomfort and injury, and can hurt your performance. Here are five dire signs that indicate it’s time to invest in a new pair of running shoes.

1.- They aren’t running shoes

This one may seem straightforward, but after attending a few run clubs, I’m amazed at how many individuals still run in worn-out skateboarding shoes or cheap trainers. Compared to other sports, running has a low entry cost. Even if you aren’t sure what you’re looking for, ask around or drop in to your local running store. You can tell them your goals, and the staff will recommend a few options for you to try out.

2.- Shin splints

Your running shoes should be the most comfortable pair of shoes you own. If you start experiencing shin splints or any pain or discomfort in your feet, it’s a sign that your shoes aren’t providing adequate support, or they may not be right type of running shoes for you. The foam in running shoes deteriorates over time (even if you aren’t using them for running), leading to less shock absorption and more stress on your joints and muscles.

3.- Worn-out soles

The most obvious sign you need to buy new running shoes is visible wear and tear on the outsole. Examine the soles of your shoes for uneven wear patterns, which can indicate that the cushioning and support are compromised. The outsole is designed to provide grip and stability, but over time it can wear down and become flat, particularly in high-impact areas like the heel and forefoot. A flattened outsole not only reduces traction, but also affects the overall structure and support of the shoe. If your shoe’s outsole is noticeably worn and smooth, it’s a clear indication you need a new pair. On average, a new pair of running shoes should last between 400 and 700 kilometers.

4.- Frequent blisters

If you are getting nonstop blisters every time you run, getting fitted for a new pair of shoes is a quick fix. Blisters indicate that your current shoes do not fit properly, are too old or aren’t meant for your foot type and running style. Shoes that are too tight, too loose or have a shape that doesn’t match your foot can cause friction, which leads to blisters. You need to get fitted at a running specialty store for a new pair of shoes.

5.- Compressed cushioning

A critical function of every running shoe is to provide cushioning for your landings. Over time, the foam in the midsole compresses and loses its ability to rebound and provide adequate support. Even if you aren’t tracking the miles in the shoes, there’s still a way to test if they are worn out. Put your hand inside the shoe and push against the midsole, with your other hand on the bottom of the outsole. If it feels hard or you can feel the force of your hand, it’s a sign that the cushioning is worn out. The pounding of your body weight against the ground is a lot more force than your hand, so if you can feel anything, it’s a clear-cut sign the shoes need to be replaced. Continuing to run on compressed cushioning can lead to increased fatigue and possible injury.

(06/07/24) Views: 145Marley Dickinson

David Rudisha explains why he never switched to a longer distance in his prime years

David Rudisha has explained why he could never dare to compete in a longer distance than the 800m.

World 800m record holder David Rudisha has disclosed why he could never dare to run a longer distance than the 800m.

Most 800m runners love blending the two-lap race with the 1500m but Rudisha opted to scale down to the 400m and he admitted that it worked perfectly for him.

In Kenya, Emmanuel Wanyonyi is one of the athletes who does the 800m and combines it with longer distances but reigning world 800m champion Mary Moraa is more of Rudisha’s type. Moraa is always known to compete in the 400m and 600m and she rarely makes appearances in the longer distances.

“If you see 800m runners, you find that some are doing 800m and others can move to 1500m and 5000m. However, others can only move to the 400m and I believe I’m the one who could only do the 400m.

“Even during my training days, I wasn’t doing so well with the endurance and I would struggle a lot. I wasn’t kind of a longer-distance athlete and at some point, at the beginning of the season, my coach would tell me to do 800m and 600m races.

“However, I never liked that because it was tough. During training, I would usually do maybe one 600m race and then go down to 200m or 400m and then the 300m, the one that I loved,” Rudisha said in an interview with World Athletics.

Speaking about his world record at the 2012 London Olympics, Rudisha disclosed that he had worked towards achieving that goal for years.

The two-time Olympic champion was only making his debut at the Olympics and deep down, he knew there was no chance of making mistakes. He explained that his team had worked around the clock and refined the finer things in his training and he was confident of running something special.

However, the two-time world champion noted that it was not an easy thing but he knew if he missed that chance, he would have to wait for four more years to make history.

“London 2012 was my first Olympic Games and as I was training, way back, my coach used to emphasise and he would say we would be in the Olympics and that got into my mind. Over five, six, seven, or eight years, I was focusing on the Olympics.

“Going there was very special and we did very good preparation to make it happen since you can’t make mistakes at the Olympics. I knew that I had a better chance and I was still in the peak of my career and we did very good training.

“At the beginning of the season, I did like two races in New York and Paris and I did 1:41, and going to London, I knew it wasn’t easy. I made my plans and knew that if I executed the race well, I would win the 800m and because I was a front runner, it would be easier for me,” Rudisha said.

(06/07/24) Views: 142Abigael Wuafula

Three workouts to rev up any race pace

Whether you’re hoping to maximize your mile pace or prepping for a fall marathon, these speedwork sessions are for you. Dr. Andrew Reheisse, a Salt Lake City-based chiropractor and running coach, suggests adding one of these speed-boosting sessions to your training regime once a week. These workouts are based around your mile pace for your goal race distance—if you calculate your running pace in kilometres, just multiply it by 1.6. For these workouts, you’ll be gearing up to 30 seconds to one minute faster than goal mile pace.

Reheisse explains that as you progress, you can extend the intervals so that you’re comfortably covering longer distances at tempo pace.

1.- 200m repeats

For these intervals, you’re aiming to run a minute or faster than your goal (mile) race pace for the interval. Tweak the number of sets to prep for any distance: for a 5-10K race, run 2-3 sets, for a half-marathon, aim for 3-4 and for a marathon, bump it up to 5 or 6. This workout is easiest on a track, where 4 laps equal 1 mile.

Warm up with a mile of easy jogging and some dynamic drills, like these.

Run 4 x 200m with a 200m jog between reps; take a 400m jog between sets.

Cool down with a mile of easy running.

2.- Speedy fartlek fun

“In this workout we play around with our speed at different intervals of time, says Reheisse. “I outlined a common workout I do, but it can really be any amount of short bursts.”

Warm up with 1 mile of easy running and 5 minutes of dynamic drills. Start with 3 sets of this workout at 1 minute faster than race pace to get a feel for it—add more sets when you feel ready.

Run 3 sets of 40 seconds, 30 seconds and 20 seconds, with recovery time equalling interval time (40 seconds of speed work followed by 40 seconds of recovery, 30 seconds fast running followed by 30 seconds recovery, etc.).Take 2 minutes of easy recovery running.Run 1 minute, 1 minute 30 seconds, 1 minute, with recovery time equalling interval time (1 minute interval followed by 1 minute of easy running).Take 2 minutes of very easy running to recover.Run 3 sets of 40 seconds, 30 seconds and 20 seconds, with recovery time equalling interval time.

Cool down with a mile of easy running.

3.- Yo-yo intervals

“These are necessary to turn your newfound speed into a sustainable pace during a race, explains Reheisse. “Performing repeat miles or 800s, or yo-yo-ing back and forth in this workout, you will still be running faster than your goal pace.” Reheisse suggests aiming for 15-30 seconds faster than goal pace on the mile repeats, and 45 seconds to 1 minute faster in the 800s. “As you progress, it will be the rest period that gets shorter, so that it becomes more race-like.

Warm up with a one-mile jog and 5 minutes of dynamic drills. This example workout is designed for a 8:00/mile goal race pace. Take 2-3 minutes of recovery running between each interval to start; lower to 1-1.5 minutes as your fitness progresses.

Run 800m with a goal time of 3:30.Run 1 mile with a goal time of 7:30-7:40.Run 800m with a goal time of 3:30.Run 1 mile with a goal time of 7:30-7:40.Run 800m with a goal time of 3:30.Cool down with an easy one-mile run.

Remember to hydrate well during speedwork sessions (and all training sessions) and follow a harder training day with a day of very easy running or complete rest.

(06/07/24) Views: 137Keeley Milne

New York Mini 10k 2024: Senbere Teferi wins third consecutive race

Senbere Teferi, a two-time Olympian and two-time World Championships medalist from Ethiopia, won her third consecutive Mastercard New York Mini 10K in a time of 30:47, just shy of the record she set in 2023 with a time of 30:12.

ABC 7 New York provided live streaming coverage of the New York Road Runners' Mini 10K race in Central Park with more than 9,000 runners expected this year.

Teferi also won 2019 UAE Healthy Kidney 10K in New York and the 2022 United Airlines NYC Half, which was the second-fastest time in the history of the event.

"It is such a special race because there is a bond that exists with thousands of women also running. Even though we are not related, I feel supported like we are all sisters in running," Teferi said prior to today's race.

2022 TCS New York City Marathon champion Sharon Lokedi finished second with a time of 31:04.

Lokedi was also the runner-up at both the 2022 Mastercard New York Mini 10K and the 2024 Boston Marathon.

"Although I have only run the Mini once before, I felt embraced by the many thousands of women who ran the race before me, and hope to inspire the many thousands more who will come after me," Lokedi said prior to today's race. "It's an awesome thing, how women from so many different places and life experiences can come and feel connected to each other through the simple act of running a loop in Central Park."

Sheila Chepkirui finished third (31:09) while American Amanda Vestri finished fourth (31:17).

The 2024 Mastercard New York Mini 10K will feature four past champions, five Paris 2024 Olympians, and seven of the top 10 finishers from the 2024 U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials.

The 52nd running of the event also featured members of 2024 U.S. Olympic Women's Marathon Team - Fiona O'Keeffe, Emily Sisson, and Dakotah Lindwurm.

New York Road Runners started the Mini 10K in 1972 as the first women-only road race, known then as the Crazylegs Mini Marathon. Seventy-two women finished the first race, and three weeks later Title IX was signed into law, guaranteeing girls and women the right to participate in school sports and creating new opportunities for generations of female athletes.

The Mastercard New York Mini 10K is now one of nonprofit NYRR's 60 adult and youth races annually and has garnered more than 200,000 total finishers to date.

The 2024 Mastercard New York Mini 10K offered $39,500 in total prize money, including $10,000 to the winner of the open division. Mastercard served as title sponsor of the event for the fourth year, and as part of its ongoing partnership with NYRR will also serve as the presenting sponsor of professional women's athlete field.

Eyewitness News provided live updates from the race and streamed the event live on abc7NY. An all-women team of WABC sports anchor Sam Ryan and meteorologist Dani Beckstrom, along with U.S. Olympian Carrie Tollefson, host of the Ali on the Run Show podcast Ali Feller, and running advocate Jacqui Moore anchored the coverage.

(06/08/24) Views: 133American track star Parker Valby wins NCAA 10,000m title in controversial shoes

Valby wore customized Nike Vaporfly Next% 3 track spikes, which are 40 mm high.

There is no doubt University of Florida athlete Parker Valby is one of the best American distance runners on the scene today; on Thursday, she earned her fifth career NCAA track and field title, winning the women’s 10,000m event in a championship record 31:46.09. After the race, Valby told Citius Mag she had a boost from her custom 40 mm stack height Vaporfly Next% 3 track spikes, which, if the NCAA followed World Athletics competition rules, would be illegal.

Since there are no rules against 40 mm shoes (with or without spikes) or prototypes in the NCAA, Valby was allowed to wear them. In World Athletics-accredited competitions, track spikes with a stack height over 25 mm are not allowed. When Valby was asked about her spikes post-race, she said Nike made them for her and presented several options for this race.

The Nike Vaporfly Next% 3 is typically used for road racing, and features a carbon-fiber plate and a max-cushioning midsole with a 40 mm stack height in the heel. This combination of the carbon-fiber plate and foam on impact increases energy return, meaning more of the runner’s exerted energy is converted into forward motion, improving speed and reducing fatigue. With spike pins added, this shoe would certainly enhance performance significantly on the track.

Valby will compete again at the 2024 NCAA Track and Field Championships on June 8 in the women’s 5,000m. She has not stated whether she will wear her personal prototype shoe. She is the reigning NCAA champion over the distance.

Valby, 21, was the only athlete in the women’s 10,000m final wearing these max-cushioned custom spikes, and she made it look easy, spending the first few laps of the 10,000m waving to herself on the Hayward Field jumbotron. Since USATF follows World Athletics competition rules, Valby’s winning time from this race would not be eligible for the U.S. Olympic Trials 10,000m qualification (though it doesn’t matter, since she has previously run a qualification time wearing a WA-legal pair of spikes).

World Athletics introduced in-competition stack height rules in 2021 to ensure fairness, maintain the integrity of the sport and address the performance advantages provided by technological advancements in footwear. As things stand in the NCAA, athletes who wear shoes with a heel stack height over the legal 25 mm will not have their times count for anything outside of the NCAA; this makes monitoring the issue extremely complicated, with hundreds of meets condensed over a 3.5-month season.

(06/08/24) Views: 132Marley Dickinson

Why Eliud Kipchoge trains on a gravel track in Eldoret once a week as he gears up for Paris Olympics

Experts have explained why Eliud Kipchoge and his teammates regulary train on a gravel track once a week as preparations for the Paris 2024 Olympics hit top gear.

Eliud Kipchoge's head coach Patrick Sang and training expert Louis Delahaije have explained why the legendary marathoner and his training mates train at the Moi University Law School track in Annex, Eldoret as they gear up for the Olympic games.

Kipchoge will be hoping to claim his third Olympic title in the marathon after securing wins at the 2016 Rio Olympics and the delayed 2021 Tokyo Olympic Games.

His management, the NN Running team, is also making sure the five-time Berlin Marathon champion is in the right shape to achieve his goals. One way has been to normalize training athletes on the gravel track.

Sang explained that the track helps in recovery especially when one is going for tougher sessions and it also does not affect the legs a lot.

“We are at Moi University, Law School, a place in Eldoret called Annex. This is where most of the athletes do their training. You can see it’s a big group training here.

“Today, we’ve had athletes run the 800m all the way to the marathon. Of course, they come here to do specific sessions, specific to their event.

“The surface is good, I mean generally when you train on tartan or the road and train here, which is a dirt track, the recovery and the stress on the legs is less and recovery for the next hard session is quicker.

“We train here twice in a week for the track runners and for the marathoners, we do it once a week,” the veteran coach said in a documentary posted by NN Running team.

On his part, Delahaije was also quick to note that Eldoret being closer to the equator is a plus for athletes and insisted that competing on such a track reduced the risk of injury. He marveled at always finding athletes running before the crack of dawn.

“When you arrive on the track, let’s say at 6 o’clock, it’s already dark and one of the nice things is there are people running around the track and slowly by slowly, in let’s say, 10-15 minutes, the lights turn on.

“I think, when you look at injuries, it’s much safer to run at a gravel track, like Annex. Obviously, it’s a 400m track and it’s in Eldoret, so it’s a little bit lower than our grounds in Kaptagat. It’s about 2000m of altitude which I think is also perfect to do some speedwork.

“Well, Eldoret is very close to the Equator which means that there is a very stable climate, first of all. The runners also feel comfortable let’s say around 20 degrees. Well, you have that more or less all year round over there,” he added.

(06/10/24) Views: 111Abigael Wuafula

Chesebe ready to defy odds to make Team Kenya to the Olympics

2011 All-African Games women's 800m bronze medalist, Sylvia Chesebe has warned her competitors not to underestimate her ahead of the Olympic trials.

Eleven athletes will vie for a spot in the women's 800 team at the Nyayo National Stadium this weekend. So far, only four have the Olympic qualification mark of 1:59.30.

Chesebe is yet to qualify as her fastest time this year is 2:03.92— set at last month's National Championships.

Motivated to make her Olympic debut, Chesebe exuded confidence in posting the qualification time at Nyayo Stadium.

“I am confident I will attain the Olympic qualification time and make Team Kenya. Competition will no doubt be tough but winning depends on preparations and I am well prepared,” Chesebe stated.

Chesebe, however, acknowledged her competitors but also warned them not to overlook her.

“I am not underrating anybody and they should not underestimate me either. I am here to push everyone to the limit,” she added.

Headlining the list is world champion Mary Moraa, who already has the qualification mark of 1:56.03 posted in Budapest, Hungary, last year.

Vivian Kiprotich is the other athlete to watch having qualified after clocking 1:58.26 during the Kip Keino Classic, where she placed second behind Moraa (1:57.96).

21-year-old Nelly Chepchirchir clocked 1:58.98 for fourth place at the same event while Naomi Korir clocked 1:59.19 during the Grifone meeting in Italy last month.

Others on the list include national champion Lilian Odira, Dorcas Ewoi, Sarah Moraa, Mweni Kalimi, Winnie Kipsang and Naumglorious Chepchumba.

Chesebe emphasised that making the Olympics team would be a dream come true and will be hoping to end Kenya’s 16-year wait for gold in the two-lap race.

"The Olympics are a dream for every athlete. It is the biggest stage to display your talent. It would mean a lot for me to make my first appearance and also win gold for Kenya,” she stated.

Kenya’s only gold medal in the women’s 800m came at the 2008 Beijing Olympics through Pamela Jelimo, who clocked 1:54.87 to clinch the title. She led leading compatriot Janeth Jepkosgei (1:56.07) and Morocco’s Hasna Benhassi (1:56.73) to the podium.

Jelimo won bronze at the 2012 London Olympics in 1:57.59) while Margaret Wambui (1:56.89) posted the same at the Rio Olympics.

Coached by her husband, Michael Cheren, Chesebe is focusing on fine-tuning her speed to ensure she is in prime condition for the trials.

“I am working on my speed. I already have the endurance, but I need to improve my speed, especially my finishing, to ensure I make the Olympic time at the trials,” she stated.

On Friday, Chesebe took part in the World Masters Athletics Trials at the Ulinzi Sports Complex, winning the 400m W35 category in 54.24 secs.

She hopes that competing in the 400m race will help her in improving her finishing.

“I took part in the 400m at the World Masters trials to work on my finishing. I hope it will pay off come the trials,” she stated.

During the 2011 All-Africa Games in Maputo, Mozambique, Chesebe clocked 2:04.16 behind Ethiopia's Fantu Magiso (2:03.22) and Uganda's Annet Negesa (2:01.81).

The 37-year-old is also a silver medallist at the 2014 World Relay Championships in Nassau, Bahamas, in the 4x800m clocking 8:04.28 together with Agatha Jeruto, Janeth Jepkosgei and Eunice Jepkoech.

(06/10/24) Views: 108Teddy Mulei