Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #ZoomX Vaporfly Next%

Today's Running News

Do Super Shoes Give Regular Marathoners a Performance Boost?

Research shows economy gains at slower paces, but they’re smaller and not guaranteed.

It’s no coincidence that running records have been falling in droves in the era of super shoes. While researchers still may not be able to fully explain how the technology works, they have shown that the ultra-compressible foam, curved carbon-fiber plate, and rockered geometry that first appeared in the Nike Vaporfly 4% in 2017 provide competitive runners a 2.7–4.2 percent boost in running economy. In other words, thanks to these shoes, runners need 2.7-4.2 percent less energy to run the same pace—meaning that they can conserve that energy to run farther or expend it to run faster.

One caveat is that, until now, super shoes have been tested only at running speeds of 7:26/mile or faster. Translated into marathon times, that means the science is applicable to someone who runs a marathon in 3:15 or faster—a feat accomplished by only 21 percent of the 2021 Boston Marathon field.

However, new research has finally emerged that looks at whether the majority of runners get an edge from super shoes. The answer: probably yes, but less.

Research for Non-Elites

Dustin Joubert, Ph.D., a kinesiology professor at St. Edward’s University in Austin, Texas, likes to do research, in his words, “for the people.” This is how he came to conduct a study looking into whether super shoes, specifically the Nike ZoomX Vaporfly Next% 2, confer the same running economy advantage to athletes who run at slower paces.

“There’s a lot of people who don’t fit under the umbrella of the speeds that have been tested in all this laboratory research, and a lot of people are asking: Should I spend my money on this? Do they work for slower people?” said Joubert. “That was the next logical question to me.”

To answer the question, Joubert and his colleagues recruited 16 runners—eight men and eight women with prior-year 5K PRs averaging 19:06 and 20:18, respectively—and had them complete two sets of four 5-minute running reps on a treadmill. Each runner ran one set at a 12 kilometers/hour pace (8:00/mile, which would be marathon pace for a runner with a 5K PR of 22:15), and the other set at 10K/hour (9:40/mile, which would be on the slower end of easy pace for that same 22:15 5K runner). Within a given set, the runners tested two different shoes: they ran one 5-minute rep in an experimental carbon-plated shoe, the Nike ZoomX Vaporfly Next% 2, and the other rep in a control shoe, the Asics Hyper Speed. Then, the runners repeated the reps but reversed the order in which they wore shoes (e.g., Asics first, then Nike).

The researchers chose the Asics Hyper Speed as the control shoe because it lacks the technology of the Vaporfly (carbon plate and advanced foam) but matches its mass. This was an important variable to match because mass affects running economy; a heavier shoe will require more energy to move and could therefore confound results. One earlier study compared the Vaporfly to runners’ everyday training shoes, but most regular training shoes are more than 100 grams (3.5 ounces) heavier—the equivalent of about 40 pennies. Imagine lifting those pennies 55,000 times (the average number of steps in a marathon, for men; women take about 63,000 steps). That would require quite a bit more energy!

Economy Advantages for 3:30–4:15 Marathoners

The new study found that, on average, running economy was better in the Vaporfly than in the Hyper Speed. However, at these slower speeds, the improvements were smaller than at faster speeds: runners gained just 1.4 percent in running economy at 8:00/mile pace and 0.9 percent at 9:40/mile pace, compared to the 2.7–4.2 percent advantage runners gained at speeds of 7:26/mile or faster. (And, as we’ll see below, even those improvements came with a caveat.)

Joubert speculates that the reason for this difference comes down to how the foam in the shoes is working. Much of the running economy advantage comes from compressing the compliant/resilient foam in the shoes and then having that energy returned as the foam springs back. A faster runner who is generating larger ground reaction forces will compress the foam more than a slower runner who, because of their speed, isn’t generating as much ground reaction force.

“The shoe is not creating energy for you; it’s only giving back what you put into it,” explained Joubert.

Not Everyone Benefits

Before you decide “an advantage is an advantage,” there is one other finding from this study that should give runners pause. While the results from the 16 test subjects showed a 0.9–1.4 percent average improvement in running economy, one third of the participants actually showed worse running economy when they ran at the 9:40/mile speed in the Vaporflys, compared to the control shoe. This finding diverges from the results of testing done on the Vaporflys at faster speeds, where runners experienced varying degrees of running economy improvement, but no one saw a detriment.

One possible reason has to do with the Vaporfly’s carbon plate. Research has shown that increased longitudinal bending stiffness, or the rigidity of a shoe underfoot, helps to improve running economy at faster speeds by reducing the amount of energy your foot requires as you land and push off from the metatarsophalangeal joint (where your foot connects with your toes). Joubert hypothesizes that, at slower speeds, the stiff carbon plate might stop saving runners energy and instead create a need for more energy in order to get “up over” the plate.

“If the plate’s really stiff, maybe at these slower speeds that’s an impairment to economy,” Joubert said.

Nathan Brown, a doctor of physical therapy at Pineries Running Lab in Stevens Point, Wisconsin, and senior contributor at Doctors of Running, said that this finding in particular helps to reinforce the shoe selection guidance he already offers his patients and the runners he coaches.

“If your goal of picking a shoe for race day is to get faster, but there’s a 30 percent chance that you get worse, I care more about finding the shoe that you like to run in than the shoe that may or may not give you a benefit,” said Brown.

So, Should You Wear Super Shoes?

If you’re an 8:40-9:00/mile marathoner, what should you do? Do you gamble on being in the 66 percent of responders and plunk down your cash for a pair of super shoes? Or do you stick with what you have?

Footwear is ultimately a personal decision, so here are a few more points to consider.

Choose a shoe that’s comfortable.

If a super shoe feels uncomfortable, that might be an indicator that the shoe won’t help you make the economy gains you’re seeking. Joubert guesses that the comfort of your shoes could affect biomechanical aspects of your race-day performance, including economy. “I think if a shoe is uncomfortable, it’s probably not going to be economical,” he said.

Brown emphasizes focusing on comfort and confidence in a race-day shoe rather than “carbon [plate] or no carbon.” To determine whether it’s comfortable, Brown recommends trying your racing shoe in a few workouts and, if your goal race is a marathon, a few long runs in advance of race day.

“You want to feel comfortable [in the] shoe and confident psychologically,” he said. “To know what to expect on a long run from your race-day shoe can be a big deal for performance.”

Don’t wear a super shoe (or any one shoe) for every single run.

Heather Knight Pech, a decorated masters runner and coach for McKirdy Trained and Knight Training, tells every one of her athletes, from high schoolers to masters runners, to invest in a minimum of three pairs of running shoes: a trainer (e.g., Brooks Ghost), a lightweight trainer (e.g., New Balance Rebel), and a race-day shoe (e.g., Nike Vaporfly Next%). She then has them rotate among these shoes for several reasons. First, it decreases injury. Research has shown that runners who rotate their shoes decrease their injury risk by 39 percent compared to runners who wear the same pair for every run.

“Running is a repetitive motion, so you avoid overloading any one muscle, bone, or tendon,” said Pech. “And on the flip side, you’re simultaneously strengthening other structures by rotating your shoes.”

In his physical therapy practice, Brown has found that super shoes tend to reduce the loading on lower leg structures like the Achilles tendon and calf. As a result, he’s noticed a trend in repetitive stress injuries further up the chain, to the hamstrings and hip flexors, in runners who wear that shoe for most or even all of their runs.

The second reason Pech advises runners to rotate shoes is that it forces them to decide between shoes for a given run, which helps them gain a better sense of self-awareness. “We should be very dialed in to how we feel—that’s part of running training and racing,” said Pech. The saying she repeats is: different shoes for different runs for different days.

Look at a variety of styles and brands.

The Nike Vaporfly was the first high-stack carbon-plated shoe on the market, and as a result, it is arguably the most well known. Most brands now have a similar shoe, and while research shows they’re not yet up to par when it comes to running economy, that doesn’t mean different shoes won’t work better for certain runners based on foot anatomy, running stride, and even pure preference.

Pech points out that the Nike Vaporfly is a very high, very narrow, very bouncy shoe. The Saucony Endorphin Pro, on the other hand, she describes as “more stable underfoot, with firmer foam. It’s great for runners who want to feel the ground.” Meanwhile, the Asics Metaspeed, which is also slightly wider underfoot than the Nike Vaporfly, offers two versions between which runners can choose based on their running style: cadence (increasing their turnover) or stride (increasing their stride length).

“I think they’ve all caught up, in that, now, there are different shoes for different people,” said Pech.

Remember: economy isn’t everything.

While running economy does influence running performance, it’s only one small part; how well you eat and sleep, your level of anxiety, how consistently you trained, how well you tapered, and numerous other factors have an equal, if not greater effect on the time you ultimately run in any given race.

Therefore, if you’re a 3:30–4:15 marathoner and don’t want to shell out the money or risk finding yourself in the 33% “anti-responder” group, double down on some basics like pre- or post-run nutrition or even just sleep. Plus, when you beat your Vaporfly-wearing counterparts, you’ll never have to ask, “Was it the shoes?”

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

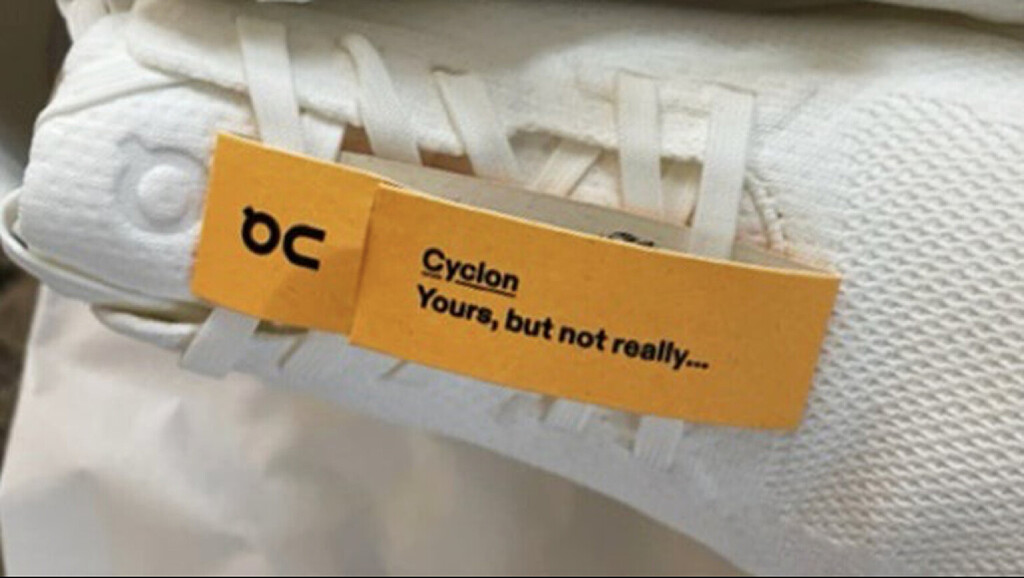

Why You Should Lease, Not Buy, Your Next Pair of Running Shoes

I signed up for the On Cyclon subscription running shoe service and get a perfectly clean new pair every three months

Back in September 2020, the Swiss running shoe company On announced a potentially industry-changing environmental business model called “Cyclon.” The program finally launched in fall 2022 with the release of the Cloudneo, a fully-recyclable running shoe that consumers don’t ever own.

Instead of spending $120 to $200 on a single pair of shoes, running in them until the cushioning is shot, and then (hopefully) donating them to a good cause, runners “lease” the Cloudneo road running shoe for $30 per month. Whenever runners want a new pair—as long as it’s been at least 90 days since they received their last shoes—they log onto their account and request the recycle option. Days later, a brand-spanking-new pair of Cloudneos arrive, along with a FedEx return label. Subscribers then have 30 days to send back their old pair, which is cleaned, ground down into recyclable components, and made into new pairs of Cloudneos.

It’s a circular, closed-loop process that costs subscribers roughly the amount they would spend to buy three new pairs of $120 running shoes per year—with zero-waste. The whole shoe, except for small elements like glue and the sock liner, is made out of a material called PA11, which comes from castor bean oil and pebax elastomers (also bio-based from castor beans). This mesmerizing video on the On-running website—which I couldn’t help but watch a few times—illustrates the process.

I got my own pair of Cloudneos early in fall 2022, anxious to test the shoes on the road—they’re touted as “performance running shoes,” after all—and the subscription program as a whole.

Upon opening the box, the first thing that stood out to me was the stark whiteness of the shoes and the white bag (made out of polypropylene) they come neatly packaged in. The color is on-trend with what the “cool kids” (my college-aged nieces and family friends) are wearing, and the kicks could pass for lifestyle shoes, look good with jeans, and “go” with everything. But how do they run?

On a four-mile jaunt around my neighborhood, I immediately enjoyed the snappy, supportive ride produced by what On calls a “Speedboard.” This full-length, semi-flexible plate is sandwiched between two layers of pebax-based foam, with three small “Cloudtec” pods—one above and two below the plate—under the midfoot. I’ve tested plenty of shoes with carbon and composite plates of various shapes in recent years. This plate—and the midsole overall—felt less turbo-boosting than those found in a supershoe like the Nike ZoomX Vaporfly Next%, but did give me some extra pop. And, while most On shoes have felt on the firmer side to me—aside from the soft and cushy Cloudmonster—the combination of bouncy foam, responsive plate, and minimal Cloudtec pods on the Cloudneo feels energetic.

On subsequent runs on paved roads and smooth dirt paths around Boulder, I felt capable in the shoes, whether running slowly or upping the pace. I did one-mile pickups up and down a slight incline during a six-mile run and felt like I was in good shoes for the job. The slightly rockered shape of the shoe seemed like it encouraged forward propulsion and a smooth stride, and the under-eight-ounce weight for my women’s pair moved with me. For runs longer than seven-or-so miles, however, I’d likely choose to run in a cushier shoe.

The upper, which is constructed from a single piece of undyed, recyclable, bio-based yarn, wrapped my feet comfortably. It’s soft and flexible, like a sock, and I didn’t feel any pressure points when I pulled the laces tight around my narrow feet.

I took the shoes on a trip to San Diego, figuring I’d wear them both casually and on runs with friends. I ended up on a hike, and the traction wasn’t great on the sandy, dusty terrain, but I wasn’t expecting it to be. These are road shoes through-and-through, not intended for trail. That said, I managed in them just fine on the trail, and appreciated that I could wear one pair of shoes for all activities over a three-day trip.

Over the months I put them to the test, I got them super dirty, which made receiving a brand-new pair that much more satisfying when they arrived. As promised, the box arrived just a few days after I hit the “recycle” button on my On-running Cyclon profile page, and the pre-paid label made the return process simple.

Bottom line: The Cyclon subscription process is promising on many levels. The Cloudneo shoes run well for me and, in my opinion, look good…and they’ll always look good because I’ll always get a new pair once they start looking shabby. On says the shoes should last around six months or 375 miles of running, but subscribers can request new (clean) ones after three months. The closed-loop, zero-waste process of the Cloudneo will hopefully inspire other brands—even across industries—to follow.

Weight: 9.0 ounces (Men’s 8.5), 7.2 ounces (Women’s 7) Stack Height: 33.6 mm heel / 24.6 mm forefoot (9 mm drop) Upper: 100% Bio-based lightweight breathable knit derived from castor beans Midsole: Two layers of lightweight, bio-based pebax foam Outsole: Injected bio-based pebax Price: $29.99+ tax/month

by Outside Online

Login to leave a comment

Who Wore Which Shoes at the New York City Marathon?

The running shoe hype train was high in New York City with a few fast yet-to-be-released shoes in the men’s and women’s elite fields.

For a few miles early in the New York City Marathon, Desi Linden surged into the lead of the women’s elite field. The two-time Olympian and 2018 Boston Marathon champion didn’t think she’d run away and win the race that way, but she was just trying to keep the pace honest.

However, hiding in plain sight on her feet as she was off the front of the pack was a yet-to-be-released pair of orange, white and black Brooks prototype racing shoes. A day later, no one is willing to give up any details of the shoe, except that, like all of the other top-tier racing shoes in both the men’s and women’s elite fields, it features a carbon plate embedded in a hyper-responsive foam midsole. And although it’s all in accordance with World Athletics regulations, it won’t be released in Spring 2024 … so we’ll all have to wait a bit to see what that shoe is all about.

Linden’s shoes weren’t the only speedy outliers among the top 25 men’s and women’s finishers. While Nike, Adidas and ASICS shoes were the most prevalent brands among elite runners, there were several shoes that aren’t yet available to the public.

For example, the first runner to cross the finish line of this year’s New York City Marathon, women’s winner Sharon Lokedi, was wearing a pair of Under Armour Velociti Elite shoes. That’s notable for several reasons—because it was Lokedi’s first marathon, because the shoe won’t become available until early 2023 and because it’s the first podium finish at a major international marathon for a runner wearing Under Armour shoes.

There were also three pairs of yet-to-be-released Hoka Rocket X 2 shoes on the feet of three Hoka NAZ Elite runners — two of whom set new personal best times, Aliphine Tuliamuk (7th, 2:26:18) Matthew Baxter (12th, 2:17:15). Those fluorescent yellow shoes with orange, white and blue accents and blue laces were on the feet of Hoka pros at the Boston Marathon in April and Ironman World Championships in Hawaii in October, but they won’t be released to the public until late February or early March.

Meanwhile, the winner of the men’s race, Evans Chebet, was wearing a pair of Adidas Adizero Adios Pro 3, a shoe worn by four other runners in the top 25 of the men’s race and six among the women’s top 25, making it the second most prevalent model among the elites. Oddly, that was the same shoe worn by Brazil’s Daniel do Nascimento, who went out at record-setting sub-2:03 pace on his own, only to crumple to the ground at mile 21 after succumbing to fatigue and cramping.

The most common shoe among the top finishers was the Nike ZoomX Vaporfly Next% 2, which was on the feet of 11 of the 50 runners among the women’s and men’s top 25 finishers. There were eight runners wearing either the first or second version of the ASICS MetaSpeed Sky.

Six runners wore Nike Air Zoom Alphafly Flyknit shoes, three wore Nike Air Zoom Alphalfy NEXT% 2. There were two pairs of On Cloudboom Echo 3 in the field, including those worn by Hellen Obiri who finished sixth while running a 2:25:49 in her marathon debut, while three runners wore Puma Fast R Nitro Elite.

And what about actor Ashton Kutcher? He wore a pair of purple Nike Air Zoom Alphafly NEXT% Flyknit shoes and finished in a very respectable 3:54:01.

Matt James, the former lead of the Bachelor, finished in 3:46:45 with Shalane Flanagan as his guide wearing a pair of New Balance FuelCell Comp Trainer shoes. Flanagan wore Nike Air Zoom Alphafly Next% Flyknit shoes, as did Meghan Duggan, an Olympic gold medalist hockey player who ran a solid 3:52:03. Lauren Ridloff, actress from “The Walking Dead,” ran in a pair of Brooks Glycerin 20 and finished in 4:05:48, while Chelsea Clinton, daughter of Bill and Hillary Clinton finished in 4:20:34 wearing a pair of Brooks Ghost 14 and Tommy Rivers Puzey (aka “Tommy Rivs,” a former elite runner who survived a deadly bout of cancer in 2020, wore a pair of Craft CTM Ultra Carbon Race Rebel and finished in 6:13:54.

Here’s a rundown of what was on the feet of the top 25 women’s and men’s finishers in the Big Apple.

1. Sharon Lokedi (Kenya) 2:23:23 — Under Armour Velociti Elite

2. Lonah Salpeter (Israel) 2:23:30 — Nike ZoomX Vaporfly Next% 2

3. Gotytom Gebreslase (Ethiopia) 2:23:39 – Nike ZoomX Vaporfly Next% 2

4. Edna Kiplagat (Kenya) 2:24:16 — Nike ZoomX Vaporfly Next% 2

5. Viola Cheptoo (Kenya) 2:25:34 — Adidas Adizero Adios Pro 3

6. Hellen Obiri (Kenya) 2:25:49 — On Cloudboom Echo 3

7. Aliphine Tuliamuk (USA) 2:26:18 — Hoka Rocket X 2

8. Emma Bates (USA) 2:26:53 — ASICS MetaSpeed Sky+

9. Jessica Stenson (Australia) 2:27:27 – ASICS MetaSpeed Sky

10. Nell Rojas (USA) 2:28:32 — Nike Air Zoom Alphafly Flyknit

11. Lindsay Flanagan (USA) 2:29:28 – ASICS MetaSpeed Sky

12. Gerda Steyn (South Africa) 2:30:22 — Adidas Adizero Adios Pro 3

13. Stephanie Bruce (USA) 2:30:34 — Hoka Rocket X 2

14. Caroline Rotich (Kenya) 2:30:59 — ASICS MetaSpeed Sky+

15. Keira D’Amato (USA) 2:31:31 — Nike Air Zoom Alphafly Flyknit

16. Des Linden (USA) 2:32:37 — Brooks Prototype

17. Mao Uesugi (Japan) 2:32:56 — Adidas Adizero Adios Pro 3

18. Eloise Wellings (Australia) 2:34:50 — Adidas Adizero Adios Pro 3

19. Sarah Pagano (USA) 2:35:03 — Adidas Adizero Adios Pro 3

20. Grace Kahura (Kenya) 2:35:32 — Nike ZoomX Vaporfly Next% 2

21. Annie Frisbie (USA) 2:35:35 — Puma Fast R Nitro Elite

22. Molly Grabill (USA) 2:39:45 — Nike Air Zoom Alphafly NEXT% Flyknit

23. Kayla Lampe (USA) 2:40:42 — ASICS MetaSpeed Sky+

24. Maegan Krifchin (USA) 2:40:52 — Adidas Adizero Adios Pro 3

25. Roberta Groner (USA) 2:43:06 — Nike Air Zoom Alphafly NEXT% 2

1. Evans Chebet (Kenya) 2:08:41 — Adidas Adizero Adios Pro 3

2. Shura Kitata (Ethiopia) 2:08:54 — Nike ZoomX Vaporfly Next% 2

3. Abdi Nageeye (Netherlands) 2:10:31 — Nike ZoomX Vaporfly Next% 2

4. Mohamed El Aaraby (Morocco) 2:11:00 — ASICS MetaSpeed Sky+

5. Suguru Osako (Japan) 2:11:31 — Nike ZoomX Vaporfly Next% 2

6. Tetsuya Yoroizaka (Japan) 2:12:12 — Nike ZoomX Vaporfly Next% 2

7. Albert Korir (Kenya) 2:13:27 — Adidas Adizero Adios Pro 3

8. Daniele Meucci (Italy) 2:13:29 — ASICS MetaSpeed Sky+

9. Scott Fauble (USA) 2:13:35 — Nike Air Zoom Alphafly NEXT% 2

10. Reed Fischer (USA) 2:15:23 — Adidas Adizero Adios Pro 3

11. Jared Ward (USA) 2:17:09 — Saucony Endorphin Pro 3

12. Matthew Baxter (New Zealand) 2:17:15 — Hoka Rocket X 2

13. Leonard Korir (USA) 2:17:29 — Nike ZoomX Vaporfly Next% 2

14. Matthew Llano (USA) 2:20:04 — Under Armour Velociti Elite

15. Olivier Irabaruta (Burundi) 2:20:14 — On Cloudboom Echo 3

16. Hendrik Pfeiffer (Germany) 2:22:31 — Puma Fast R Nitro Elite

17. Jonas Hampton (USA) 2:22:58 — Adidas Adizero Adios Pro 3

18. Alberto Mena (USA) 2:23:10 — Nike ZoomX Vaporfly Next% 2

19. Jacob Shiohira (USA) 2:23:33 — Nike Air Zoom Alphafly Flyknit

20. Edward Mulder (USA) 2:23:42 — Nike Air Zoom Alphafly Flyknit

21. Jordan Daniel (USA) 2:24:27 — Nike ZoomX Vaporfly Next% 2

22. Nathan Martin (USA) 2:25:27 — ASICS MetaSpeed Sky+

23. Jeff Thies (USA) 2:25:45 — Nike Air Zoom Alphafly NEXT% 2

24. Shadrack Kipchirchir (USA) 2:28:15 — Puma Fast R Nitro Elite

25. Abi Joseph (USA) 2:29:16 — Nike Air Zoom Alphafly Flyknit

by Outside

Login to leave a comment

The North Face Just Dropped the First Carbon-Plated Trail Running Shoe

Controversial speed is coming to a mountain near you

I’ve tested out carbon-plated shoes from a variety of running brands over the last 12 months. A movement that began with Nike’s NEXT% line — which propelled Kenyan legend Eliud Kipchoge to a mind-boggling sub-two hour marathon back in late 2019 — has now firmly taken over the sport.

For the skeptics out there, these shoes are legit. There’s a reason the success of Nike’s shoe led to allegations of “gear doping,” new rules from the World Athletics body, and a call to arms for competitors like Adidas, ASICS and Saucony. The shoes generally combine tall, lightweight foam (which running journalist Amby Burfoot once compared to having extra leg muscles), with a carbon insert, meant to facilitate maximum energy retention — to “propel you froward” as the brand copywriters like to say.

After all that initial noise, they’re not only here to stay; they’re poised to take over other sub-sections of the sport. Yesterday, The North Face dropped a first look at its VECTIV series, the world of trail running’s first official carbon-plated running shoes.

I have zero complaints about my carbon-plated shoes. (Lately, I’ve been running in the Nike ZoomX Vaporfly NEXT%s and the Saucony Endorphin Pros.) In a year without races, they’ve helped me to log some benchmark times I’m proud of. That said, those shoes are noticeably reliant on dry, clean surfaces. They like asphalt, they prefer track. Whenever either is slick from rain or snow, or — god forbid — roots or leaves get involved, they have a ton of trouble gripping the ground.

The North Face, a brand as synonymous with all-elements gear as any on the planet, has designed a carbon-plated shoe that can actually handle unforgiving trails. Most running brands have their athletes come in and test out prototypes on a treadmill; TNF trail runners logged up to 600 miles in a single pair, and much of them on punishing terrain. One runner ran 93 miles around Mt. Rainier in them this past summer.

The premier release in TNF’s line, the FLIGHT VECTIV, aims for stability and strength, like any other reliable trail running shoe. It has a high-grip outsole, while its mesh fibers are literally reinforced with Kevlar. But it’s built for speed. The shoes contain a 3D plate directly underneath the foot, alongside a rocker midsole. Ultrarunner Pau Capell described the shoes as a “downhill weapon.” Trail runners often have to slow down due to practical concerns, not for lack of spirit. These shoes are designed to let them fly.

And, crucially, to avoid injury while doing so. The maximalist foam included in carbon-plated shoes blunts the impact of runners logging so many miles. Ultrarunners are on another level entirely; they’re incessantly susceptible to stress fractures, plantar fasciitis, sprained ankles, cramps, and broken toes. But the VECTIV line — which also includes the INFINITE and the ENDURIS, two shoes less concerned with speed — promises 10% less “impact shock.” It could bring more newcomers to the sport, and keep around those who already love it.

Login to leave a comment

By Defying Expectations, Nike NEXT% Moves Athletes Forward

Call it the ultimate test run: When Eliud Kipchoge broke the two-hour marathon barrier in Vienna this past October, he was wearing a prototype of the Nike Air Zoom Alphafly NEXT%.

"For runners, records like the four-minute mile and two-hour marathon are barometers of progress. These are barriers that have tested human potential. When someone like Eliud breaks them, our collective belief about what's possible changes," says Tony Bignell, VP, Footwear Innovation. "Barriers are inspiring to innovators. Like athletes, when a barrier is in front of us, we are challenged to think differently and push game-changing progress in footwear design.”

The NEXT% platform is the ultimate expression of Nike's ambition to engineer footwear with measurable performance benefit. NEXT% is all about creating more efficient intersections between the body and technology to enable athletes to shatter personal boundaries — and sometimes, as our athletes have shown, break records. It is the ultimate meeting of sports science and purposeful design.

“The groundbreaking research that led to the original Vaporfly unlocked an entirely new way of thinking about marathon shoes,” says Carrie Dimoff, an elite marathoner and member of Nike’s Advanced Innovation Team. "Once we understood the plate and foam as a system, we started thinking about ways to make the system even more effective. That’s when we struck upon the idea of adding Nike Air to store and return even more of a runner’s energy and provide even more cushioning.”

Nike NEXT% is a footwear innovation system engineered to give athletes a measurable benefit. Informed by sport science and verified by the Nike Sport Research Lab, the Nike Air Zoom Alphafly NEXT% features three critical components, working together to help runners on race day:

Nike’s newest race-day shoe, the Nike Air Zoom Alphafly NEXT% features two new Nike Zoom Air pods, more ZoomX foam and a single carbon fiber plate (all updates from its predecessor, the Nike ZoomX Vaporfly NEXT%), and an ultra-breathable, lightweight Flyknit upper – all adding up to improved cushioning and running economy.

The shoe is part of a suite of products releasing in summer 2020, including the Nike Air Zoom Tempo NEXT% and Nike Air Zoom Tempo NEXT% FlyEase, complementary training shoes that translate the principles of the Alphafly to rigorous daily use, and track spikes (the Nike Air Zoom Victory) that extend the NEXT% design ethos to new disciplines.

For the Tempo NEXT%, the NEXT% system is specifically tuned to training. The plate shifts from carbon to a composite — softer for added comfort over higher mileage — but still serves to provide stability and transition throughout a runner's full stride. ZoomX, prized for its energy return and responsiveness, sits above the plate at mid and forefoot. For maximum impact protection and durability, Nike React Foam is used at the heel. The same Nike Zoom Air pods featured in the new Nike Air Zoom Alphafly NEXT% are also placed in the Tempo’s forefoot to offer responsive cushioning and a sensation of propulsion.

The Nike Air Zoom Alphafly NEXT%, Nike Air Zoom Tempo NEXT% and Nike Air Zoom Tempo NEXT% FlyEase give athletes of today an opportunity to stamp their mark and motivate athletes (and designers) of tomorrow to set even greater goals.

Login to leave a comment

Nike's controversial Vaporfly shoe has been permitted for use in the Tokyo 2020 Olympics

World Athletics has temporarily updated its guidelines for sports shoes worn in competitive events ahead of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics in July.

The new guidelines from the international governing body for athletics bans the trainer Eliud Kipchoge wore to break the two-hour marathon record.

Vaporfly meets new stipulations, However, Nike's Vaporfly range – including the Nike ZoomX Vaporfly NEXT% and the Zoom Vaporfly 4% – meets the stipulations of World Athletics' amended Technical Rules.

These prohibit shoes with soles that are thicker than 40 millimetres and the inclusion of more than one carbon-fibre plate, or similar item, in the sole.

The news comes amid criticism of the fairness of allowing athletes to compete while wearing the Vaporfly range, which have thick, foam soles and carbon-fibre plates to improve speed.

In 2019, 31 of the 36 podium positions in the six world marathon majors were won by elite athletes wearing Vaporfly, as reported by the Guardian.

World Athletics' Moratorium, which forms part of the Clothing section of the guidelines, also states that, from 30 April, shoes have to be on the open market for at least four months before an elite athlete can wear them for a contest.

While Vaporfly remains within the amends, the prototype Air Fly trainer that Nike-sponsored Kenyan runner Eliud Kipchoge wore to run a sub-two-hour marathon in October 2019 will be banned under the regulations.

The sneaker has a much chunkier sole than the Vaporfly and reportedly includes three carbon-fibre plates.

It has been reported, however, that Nike still has time to make amends to the Alpha Fly ahead of a release in March – over four months before the start of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics on 24 July.

This could make it possible for athletes to wear the shoe during the major competition.

by Eleanor Gibson

Login to leave a comment

Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games

Fifty-six years after having organized the Olympic Games, the Japanese capital will be hosting a Summer edition for the second time, originally scheduled from July 24 to August 9, 2020, the games were postponed due to coronavirus outbreak, the postponed Tokyo Olympics will be held from July 23 to August 8 in 2021, according to the International Olympic Committee decision. ...

more...Nike’s Fastest Shoes May Give Runners an Even Bigger Advantage Than First Thought

Anyone who saw Eliud Kipchoge of Kenya break the two-hour marathon barrier in October very likely saw something else, too: the thick-soled Nike running shoes on his feet, and, in a blaze of pink, on the feet of the pacers surrounding him.

These kinds of shoes from Nike — which feature carbon plates and springy midsole foam — have become an explosive issue among runners, as professional and amateur racers alike debate whether the shoes save so much energy that they amount to an unfair advantage.

A new analysis by The New York Times, an update of the one conducted last summer, suggests that the advantage these shoes bestow is real — and larger than previously estimated.

At the moment, they appear to be among only a handful of popular shoes that matter at all for race performance, and the gap between them and the next-fastest popular shoe has only widened.

We found that a runner wearing the most popular versions of these shoes available to the public — the Zoom Vaporfly 4% or ZoomX Vaporfly Next% — ran 4 to 5 percent faster than a runner wearing an average shoe, and 2 to 3 percent faster than runners in the next-fastest popular shoe. (There was no meaningful difference between the Vaporfly and Next% shoes when we measured their effects separately. We have combined them in our estimates.)

This difference is not explained by faster runners choosing to wear the shoes, by runners choosing to wear them in easier races or by runners switching to the shoes after running more training miles. In a race between two marathoners of the same ability, a runner wearing these shoes would have a significant advantage over a competitor not wearing them.

The shoes, which retail for $250, confer an advantage on all kinds of runners: men and women, fast runners and slower ones, hobbyists and frequent racers.

Many other brands, including Brooks, Saucony, New Balance, Hoka One One and Asics, have introduced similar shoes to the market or plan to. These shoes may provide the same advantage or an even larger one, but most do not yet appear in sufficient numbers in our data to measure their effectiveness.

What makes these shoes different is, among other things, a carbon-fiber plate in the midsole, which stores and releases energy with each stride and is meant to act as a kind of slingshot, or catapult, to propel runners. The shoes also feature midsole foam that researchers say contributes to increased running economy.

Whether the shoes violate rules from track’s governing body, World Athletics, depends on how one interprets this sentence from its rulebook: “Shoes must not be constructed so as to give athletes any unfair assistance or advantage.” It does not specify what such an advantage might be.

“We need evidence to say that something is wrong with a shoe,” a spokesman for the governing body, then called the I.A.A.F., told The Times last year. “We’ve never had anyone bring some evidence to convince us.”

In an announcement earlier this year, the group said, “It is clear that some forms of technology would provide an athlete with assistance that runs contrary to the values of the sport.” It has since appointed a technical committee to study the shoe question, and to make a report with recommendations. (The report was originally intended to be released to the public by the end of the year; it will now reportedly be released in 2020.)

When we asked Nike last year about whether its shoes might violate I.A.A.F. rules, a spokesman said the shoe “meets all I.A.A.F. product requirements and does not require any special inspection or approval.”

Last Thursday, the company said in a statement, “We respect the I.A.A.F. and the spirit of their rules, and we do not create any running shoes that return more energy than the runner expends.”

There is no such thing as a large-scale randomized control trial for marathons and shoes, but there is Strava, a fitness app that calls itself the social network for athletes. Nearly each weekend, thousands of runners compete in races, record their performance data on satellite watches or smartphones, and upload their race data to the app. This data includes things like a race name, finish time, per-mile splits and overall elevation profile. And about one in four races includes self-reported information about a runner’s shoes.

In all, this data includes race results from about 577,000 marathons and 496,000 half marathons in dozens of countries from April 2014 to December 2019.

How we measured the shoes’ effect

[These approaches are essentially identical to the ones The Times used last summer. See that article for more examples and methodological details.]

We measured the shoes’ performance using four different methods — each with its own strengths and flaws:

1. Using statistical models2. Studying groups of runners who ran the same pair of races3. Following runners as they switch shoes4. Measuring the likelihood of a personal record in a pair of shoes

None of these approaches are perfect, but they all point to the same conclusion: Something is happening in races with the Vaporfly and Nike Next% shoes that is not happening with most any other kind of popular shoe.

Besides race times and the names of shoes, we also have data on runners’ gender and approximate age. For some of the more serious runners, we have detailed information about their training volume in the months leading up to a race. We also know about the weather on race day.

When we put this information into a statistical model, times associated with Vaporfly and Next% shoes are a clear outlier — about 2 percent faster than with the next-fastest shoe. The model estimates the effect of wearing these shoes compared with the effect of wearing other shoes.

No statistical model is perfect, and it’s possible that runners who choose to wear Vaporfly or Next% shoes are somehow different from runners who do not. Regardless of the decisions that went into this model — even when trying to control for runners’ propensity to wear the shoes in the first place — the outputs were similar.

Strava is very popular among runners. At last year’s Berlin Marathon, for example, more than 10,000 runners uploaded race information to Strava, and this year, more than 14,000 did. Crucially for our purposes, about a thousand of those runners ran both races, and a subset of them reported racing in different shoes.

We could then examine the change in performance of two similar runners — people with similar race performances and, ideally, training regimens — and compare the improvement of a runner who switched shoes with a runner who did not. In Berlin, runners who switched to Vaporfly or Next% shoes improved their times more than runners who did not, on average.

For two athletes and a single pair of races, this might not tell us much. But in our data, there are thousands of instances when pairs of runners ran in the same two races.

When we perform this calculation for every pair of races in our data and measure the effect of switching to any kind of popular shoe, we see that runners who switch to these Nike shoes improved significantly more than runners who switched to any other kind of shoe. No other shoe comes close to having the same effect.

More than 110,000 athletes uploaded data for more than one marathon, and about 47,000 uploaded data for three or more marathons. The Strava data allows us to follow these repeat racers over time and as they change shoes.

When we aggregate the change in race times for runners the first time they switch to a new pair of shoes, runners who switched to Vaporflys or Next% shoes improved their times more than runners who switched to any other kind of popular shoe.

Race times are, in many ways, a crude way to measure performance. One marathon may be hilly or full of sharp turns; others may be flat and straight. Weather, too, is important, with higher temperatures typically resulting in slower times. And yet race times are how runners qualify for prestigious races, like the Boston Marathon, and most runners know their personal best times by heart, regardless of whether the race they ran was flat or hilly, on a hot day or a cold one.

We can follow the runners in our data with this measure in mind, testing whether a runner’s fastest time is more likely when he or she switches to any kind of shoe.

Someone can run a personal best for all kinds of reasons unrelated to shoes. A runner may train more, execute a better strategy on race day or run an easier course. Regardless, we found that runners who switched to these shoes were more likely to run their fastest race than runners who switched to any other kind of popular shoe.

by Kevin Qealy and Josh Katz

Login to leave a comment

A New York Times study finds the Nike Next% and Vaporfly could lead runners to improved odds of a personal best

The New York Times repeated, with a larger sample size, the study of the Nike Vaporfly that they conducted in 2018. Their updated study included the Nike Next% and the findings were surprising. We knew the Vaporfly and Next% were arguably some of the best shoes on the market, but the NYT finds that their current dominance is undeniable.

The New York Times repeated, with a larger sample size, the study of the Nike Vaporfly that they conducted in 2018. Their updated study included the Nike Next% and the findings were surprising. We knew the Vaporfly and Next% were arguably some of the best shoes on the market, but the NYT finds that their current dominance is undeniable.

The study founds that, “The Zoom Vaporfly 4% or ZoomX Vaporfly Next% — ran 4 to 5 percent faster than a runner wearing an average shoe, and 2 to 3 percent faster than runners in the next-fastest popular shoe.” The name four per cent was born out of Nike’s finding that the shoe could make the wearer four per cent more efficient–efficiency translates to less effort at the same pace, which means a runner can go faster. So the claim that the shoe makes a runner faster as opposed to simply more efficient is new.

Another key finding was that men had a 73 per cent chance of running a personal best in the shoes, while women had a 74 per cent chance, “In a race between two marathoners of the same ability, a runner wearing these shoes would have a significant advantage over a competitor not wearing them.” The Times also reports, “In the final months of 2019, about 41 per cent of marathons under three hours were reported to have been run in these shoes (for races in which we have data).”

When someone first comes to running, they find that after the initial agony of getting your legs used to the motion, there’s quick improvement. You’ll run a 5K personal best and then a subsequent PB just weeks (or even days) later. Because you’re new to the sport, the time melts away in the first few races.

But as you progress and become better, it can take months and even years to run a personal best. And for the competitive runner, staying patient is the hardest part. But what if someone told that runner who’d been trying to PB for 14 months, 27 days and 13 hours, that if they spent $330 CAD they had a 73 per cent chance at finally improving? If they have the budget, that’s an appealing statistic.

Two weeks ago Molly Huddle, who has the sixth-fastest marathon time among American women in 2019 (she ran a personal best 2:26:33 at the London Marathon), replied to a tweet by sports journalist Cathal Dennehy about the AlphaFly (Nike’s next step in the carbon-plated game). The shoe was first seen on the feet of marathon world record-holder Eliud Kipchoge, who raced to a 1:59:40 finish in them at the INEOS 1:59 Challenge in Vienna last month. Huddle’s comment: “Kinda nervous as to how this would affect the Olympic Trials over here @usatf.”

It’s not just Huddle who has noticed the effect the shoe (or prototype versions) could have on the US Olympic Marathon Trials. Runners are qualifying for the event at unprecedented rates. With the qualifying window still open for another five weeks, entries are already nearing the thousands.

It’s important to note that the qualifying standard for the trials did get two minutes easier (2:43 in 2016 to 2:45 in 2020). But does two minutes warrant a potentially doubled field size or are technological advantages, like the Nike shoes, the reason for the jump? The New York Times’ finding would suggest the latter.

by Madeleine Kelly

Login to leave a comment

It was a good day for American men at the Chicago Marathon as the top four ran under 2:11

The Chicago Marathon may not have gone well for 2017 champion and Olympic bronze medalist Galen Rupp, who dropped out just before the 23-mile mark. (He had been nursing a calf strain since mile six and just could not handle the pain any longer.) But for many of the other American pro men, the cool temperatures, boisterous crowds, and fast course brought breakthroughs.

Four U.S. men ran under 2:11, six placed in the top 15, and many others set significant personal bests.

Working together in a pack, a group of more than a dozen stuck together through about the 35K mark, trading off leading duties because of the wind.

They didn’t coordinate beforehand, exactly, but they shared a goal: “We were all interested in having a good American day,” said top U.S. finisher Jacob Riley, 31, who finished ninth in 2:10:36.

Riley is no newcomer to Chicago—he debuted at the distance here in 2014, when he ran 2:13:16 to place second American and 11th overall. At the Olympic Marathon Trials in 2016, he placed 15th, with a 2:18:31.

But he hasn’t toed a marathon starting line since. In fact, he’s undergone a near complete life upheaval. He left Michigan and the Hansons-Brooks Distance Project to move to Boulder, Colorado, where he now trains under coach Lee Troop. In 2018, he underwent Achilles surgery due to a condition called Haglund’s deformity—the same one that affected Rupp.

Amidst all the challenge, he said, he definitely contemplated quitting. “At the same time, running has been kind of the constant in my life since I was in high school,” he said. “The idea of having all this other change and then not doing that as well was scary and just not worth it.

After a slow, steady, return to running—he recalls Troop assigning him segments of one-minute jogs with nine-minute walk breaks—Riley raced again at the Boulder Boulder 10K in May, where he ran 31:20 and placed 25th. On Sept. 2, he ran 1:10:59 for 15th place at the USATF 20K Championships, which “felt terrible.”

“This is the first race where I've actually felt like the old me beforehand—or actually a better me, because I have two good Achilles now,” he said.

In his debut at the distance, 24-year-old Jerrell Mock ran 2:10:37 to place ninth, and second American. An All-American at Colorado State, Mock finished just out of contention to make the 10K final at the 2018 NCAA Outdoor Championships. Though he graduated last year, he still lives and trains in Fort Collins, Colorado, and is coached by CSU’s Art Siemers.

This year, he ran 1:02:15 to place 13th—and third American—in his first half marathon, in Houston. His 59:43, ninth-place finish at the USATF 20K Championships last month gave him confidence lining up in Chicago.

Still, he didn’t know quite what to expect in the marathon, given the “horror stories” he’d heard about the later miles. “I was just waiting to get to that moment of darkness,” he said. But it never came. “The mile splits just stayed right on. And so when we got to 20, I was like—‘Man, I think, I think I might've gotten away with it.”

Both Riley and Mock are unsponsored and wore ZoomX Vaporfly Next% shoes during the race. “I bought into the hype,” Riley said, though he noted he’s open to experimentation if any sponsors should come calling. Mock expressed similar sentiments: “There’s a lot of companies that are coming out with the same kind of idea now,” he said. “I’d be interested to try some of those too.”

Parker Stinson, meanwhile, runs in Saucony—making him one of the few elites in the field not to sport bright pink on their feet. He denied that puts him at a disadvantage, noting that he broke the American record in the 25K—the 1:13:48 he ran in May’s River Bank Run—in the brand.

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

Bank of America Chicago

Running the Bank of America Chicago Marathon is the pinnacle of achievement for elite athletes and everyday runners alike. On race day, runners from all 50 states and more than 100 countries will set out to accomplish a personal dream by reaching the finish line in Grant Park. The Bank of America Chicago Marathon is known for its flat and...

more...