Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #Stress fractures

Today's Running News

The Evolution of the High School Sub-4 Mile Club

On May 6, 1954, Roger Bannister made history by running the first sub-4-minute mile, clocking 3:59.4 in Oxford, England. His groundbreaking achievement redefined what was possible in middle-distance running, inspiring generations of athletes to chase the elusive mark.

For decades, breaking the 4-minute barrier remained an extraordinary feat, but in recent years, more high school runners in the United States have joined this exclusive club. As of February 2025, 23 American high school boys have accomplished this milestone, with notable additions in 2024 and 2025.

The Latest High School Runners to Break Four Minutes

The most recent athletes to achieve the sub-4-minute mile in high school competition are:

- Drew Griffith – 3:57.72 (May 30, 2024, Festival of Miles, St. Louis, Missouri)

- JoJo Jourdon – 3:59.87 (February 3, 2024, New Balance Indoor Grand Prix, Boston, Massachusetts)

- Zachary Hillhouse – 3:59.62 (June 16, 2024, New Balance Nationals Outdoor, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)

- Owen Powell – 3:57.74 (February 15, 2025, UW Husky Classic, Seattle, Washington)

These runners continue to prove that the sub-4-minute mile, once thought to be nearly impossible for young athletes, is an achievable milestone with the right combination of talent, training, and opportunity.

Jim Ryun and Alan Webb: The Legends of the High School Mile

Jim Ryun: A Historic Career

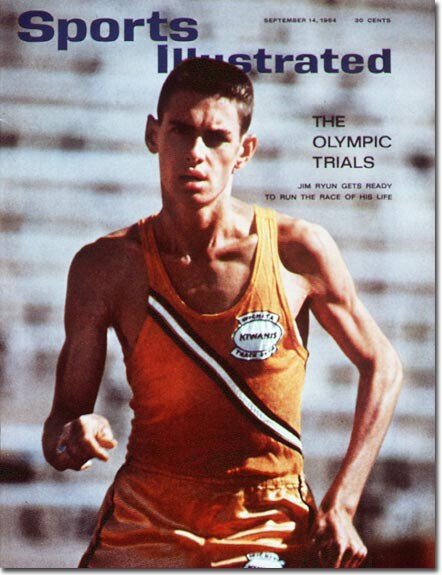

Jim Ryun was the first high school runner to break the 4-minute mile, running 3:59.0 in 1964 as a junior. He later set the national high school record of 3:55.3 in 1965, a time that stood for 36 years.

After his historic high school career, Ryun went on to break the world record in the mile twice—first in 1966, and then again in 1967 when he ran 3:51.1. At 19 years old, he remains the youngest world record holder in the mile to date. His record stood for nine years before being broken in 1975.

Ryun represented the United States in three Olympic Games (1964, 1968, and 1972), winning a silver medal in the men’s 1500m at the 1968 Olympics. His dominance in middle-distance running made him one of the greatest milers in history.

Alan Webb: The New Generation's Record-Breaker

In 2001, Alan Webb broke Ryun’s long-standing high school mile record by running 3:53.43 at the Prefontaine Classic. Webb’s performance redefined expectations for young milers and set a new benchmark for high school runners.

Webb continued his success post-high school and later set the American record in the mile, running 3:46.91 in 2007. This remains one of the fastest mile performances ever by an American.

Despite his success, Webb’s professional career was marked by injuries, including Achilles tendonitis and stress fractures, which affected his consistency. However, his high school and professional achievements cemented his place as one of the greatest milers in U.S. history.

The Complete List of High School Sub-4 Milers

Below is the full list of American high school runners who have broken the 4-minute mile, ranked by their fastest time achieved during high school competition:

- Alan Webb (first photo) – 3:53.43 (May 27, 2001, Prefontaine Classic, Eugene, Oregon)

- Jim Ryun (second photo) – 3:55.3 (June 27, 1965, AAU Championships, San Diego, California)

- Colin Sahlman (third photo) – 3:56.24 (May 28, 2022, Prefontaine Classic, Eugene, Oregon)

- Drew Griffith – 3:57.72 (May 30, 2024, Festival of Miles, St. Louis, Missouri)

- Hobbs Kessler – 3:57.66 (February 7, 2021, American Track League Invitational, Fayetteville, Arkansas)

- Drew Hunter – 3:57.81 (February 20, 2016, NYRR Millrose Games, New York City, New York)

- Gary Martin – 3:57.89 (June 2, 2022, Festival of Miles, St. Louis, Missouri)

- Connor Burns – 3:58.83 (June 2, 2022, Festival of Miles, St. Louis, Missouri)

- Tim Danielson – 3:59.4 (June 11, 1966, San Diego Invitational, San Diego, California)

- Reed Brown – 3:59.30 (June 1, 2017, Festival of Miles, St. Louis, Missouri)

- Matthew Maton – 3:59.38 (May 8, 2015, Oregon Twilight Meet, Eugene, Oregon)

- Grant Fisher – 3:59.38 (June 4, 2015, Festival of Miles, St. Louis, Missouri)

- Michael Slagowski – 3:59.53 (April 29, 2016, Jesuit Twilight Invitational, Portland, Oregon)

- Leo Daschbach – 3:59.54 (May 23, 2020, The Quarantine Clasico, El Dorado Hills, California)

- Simeon Birnbaum – 3:57.53 (June 1, 2023, Festival of Miles, St. Louis, Missouri)

- Rheinhardt Harrison – 3:59.33 (June 3, 2022, Golden South Series #2, Tarpon Springs, Florida)

- Marty Liquori – 3:59.8 (June 23, 1967, AAU Championships, Bakersfield, California)

- Lukas Verzbicas – 3:59.71 (June 11, 2011, Adidas Grand Prix, New York City, New York)

- JoJo Jourdon – 3:59.87 (February 3, 2024, New Balance Indoor Grand Prix, Boston, Massachusetts)

- Zachary Hillhouse – 3:59.62 (June 16, 2024, New Balance Nationals Outdoor, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)

- Owen Powell – 3:57.74 (February 15, 2025, UW Husky Classic, Seattle, Washington)

- Tinoda Matsatsa – 3:58.70 (June 1, 2023, Festival of Miles, St. Louis, Missouri)

- Jackson Heidesch – 3:59.08 (June 1, 2023, Festival of Miles, St. Louis, Missouri)

The Sub-4 Mile Remains an Iconic Benchmark

Roger Bannister’s 1954 breakthrough redefined human potential in distance running, and the high school sub-4-mile club continues to grow. As competition and knowledge improve, the question isn’t whether more young runners will join the club, but just how fast the next generation can go

Login to leave a comment

When It’s Time to Replace Your Running Shoes

When this assignment hit my inbox, my first thought was: I am 100 percent going to find out that I need to buy new running shoes. I jog a few times a week and haven’t replaced my Hoka Clifton 9’s since 2023. The chunky, cushioned sole that Hokas are known for has been flattened by months of trail running, and the bright neon yellow exterior has dimmed to a dull mustard.

But they do the job, and I’m a bit frugal, so I’ve stuck with them. But after speaking with a few sneaker experts, I learned I’m not doing myself any favors by holding onto beat-up gear. The more I use them, the greater my risk of an injury.

Here’s why it’s worth replacing your go-to kicks—and how to figure out when to do it.

What Is the Average Lifespan of Running Shoes?

The average running shoe is thought to last about 300 to 500 miles or five to eight months of regular use, but determining your shoe’s true lifespan is more complicated, says Daniel Shull, Run Research Manager at Brooks Running.

Many factors shorten or extend the longevity of your sneakers, including how often you wear them, the kind of terrain and weather you run in, and your stride and strike habits, says Shull.

“Every runner is different, and every shoe is different,” says Arianna L. Gianakos, a Yale Medicine orthopedic surgeon specializing in sports-related foot and ankle injuries.

Trekking through mud, gravel, and puddles can erode your footwear, as can working out in hot or frigid temperatures, says Susan L. Sokolowski, a professor of sports product design at the University of Oregon. She explains if you’re a heavy runner, meaning you land on your foot hard, the foam in the middle of your shoe will break down faster. And if your foot rolls inward or outward, you can wear out a part of your shoe that isn’t built for regular impact, such as the edges or outsole, speeding up your need for

For example, I don’t merely wear my Hokas when I jog. I also wear them when I recreationally hike, bike, and walk my dog all over town. So, while I’d love to think my running shoes last a year, they probably give out much sooner.

Why It’s Important to Replace Running Shoes

When your foot slams onto the ground, your shoe acts as a buffer and absorbs some of the force hitting your foot and ankle, Gianakos says. According to a 2023 review published in Exercise Science and Sports Reviews, shoes influence how your foot interacts with the ground, impacting your performance, speed, comfort levels, and risk of sustaining an injury.

If your sneaker no longer provides the support and cushioning your feet need, you can hurt the joints, tendons, and ligaments in your feet, ankles, and even upper leg, says Gianakos. You can run (pun intended) into a whole host of injuries like plantar fasciitis, tendonitis, stress fractures, and shin splints, she adds.

You may get pain in the ball of your foot (or metatarsalgia), patellofemoral pain syndrome, which causes pain around the kneecap, or iliotibial (IT) band syndrome, a condition that causes pain near the outside of your

So, do a body scan next time you’re out on the trail. Do you notice any foot or ankle aches and knee pains? What about burning sensations on the sole of your foot? How about blisters or calluses? Any of these symptoms may indicate your shoes are shot, says Gianakos.

How to Extend the Life of Your Favorite Pair of Sneaks

First, be mindful of how you store your shoes. You want to keep them in a clean, dry location to prevent mold from growing, says Sokolowski. And don’t store them in a hot, sunny car—UV exposure and heat can cause them to dry out and crack, she adds.

Gianakos recommends having (at least) two pairs of sneakers. That way, you can occasionally switch them out to slow the wear and tear. Another tip: have different sneakers for running in different environments—like “a trail shoe, a road shoe, and even a race day shoe,” says Sokolowski.

And save your running shoes for running only. “The time and amount of steps put on your shoes by walking, standing, and running errands all count towards how long they’ll last,” says Shull.

For all your other day-to-day activities and

Login to leave a comment

Recovery runs: Everything you need to know

At first glance, the words ‘recovery’ and ‘run’ might seem juxtaposed. After all, running is about expending energy, while recovery seems to be about recouping it. Even if we accept the term, what’s the point of a recovery run? And how does it distinguish itself from other forms of running, such as easy running? Understanding the definition and purpose of recovery runs can help you to incorporate them into your routine – boosting your recovery and overall fitness.

What’s the point of a recovery run?

In the aftermath of a hard workout or race, your muscles can become sore – a phenomenon known as DOMS (short for ‘delayed onset muscle soreness’). In this state, the prospect of running may seem unappealing, but doing so can loosen up the body by increasing blood flow to the muscles and flushing out waste. This, in short, is the purpose of a recovery run.

How do you do a recovery run?

In many ways, a recovery run is similar to an easy run. It’s done at a slow pace (or in heart rate zones 1 or 2, for those who use that as a metric) and should feel easy and relaxed throughout. However, from a duration perspective, recovery runs tend to be around 20-30 minutes in length, whereas easy runs could conceivably stretch to an hour or more. The reason for this is that, after 30 minutes of running, the body begins to produce metabolic waste, which in itself requires recovery time. When it comes to recovery runs, think easy and short.

What is active recovery?

Another terms that seems self-contradictory, active recovery is loosely defined as ‘low-intensity exercise that a person performs after high-intensity exercise to improve recovery’. Recovery runs fit firmly into this category. The alternative to active recovery is passive recovery, defined as ‘a period of inactivity after exercise where the body is allowed to heal without any additional physical activity’. Neither is better than the other, and the smart runner will use a combination of both passive and active recovery. As a general rule, though, passive recovery is the better choice if you’re showing signs of overtraining. These signs include extreme tiredness, lingering soreness, trouble sleeping, irritability or an elevated resting heart rate.

Is recovery different for men and women?

Although both sexes need to recover adequately after hard workouts and races, there is some evidence to suggest that recovery times vary between men and women. In a new study that looked at men and women who’d just run a half marathon, women showed earlier functional recovery than men. There are several potential reasons for this. One is that women have lower muscle mass and power output than men, so are therefore considered less prone to fatige. Another is the role of estrogen, which might lower the impact of exercise-related skeletal muscle damage. That said, women’s recovery is heavily influenced by where they are in their menstrual cycle, with one study finding that menstruation raises metabolic rate by more than 6% – something that will an impact on recovery and overall perception of fatigue.

What are the alternatives to recovery runs?

Of all the types of running session, recovery runs are probably the easiest ones to substitute for other cross training activities. Low-impact activities such as cycling or swimming will provide the same benefits, without any of the pavement pounding. If you’re a runner who is susceptible to impact injuries, such as stress fractures or shin splints, it’s worth thinking about whether your next recovery session actually needs to be a run.

by Rick Pearson

Login to leave a comment

Which Running Tests Are Worth the Investment?

Experts break down which type of runner is most likely to benefit from tests including a gait analysis, VO2 max, and more.

Running itself is pretty basic—in the best of ways. All you really need is a pair of running shoes to get started. Of course, additional gear can be helpful, not to mention fun to test out and use to boost performance. Investing in certain fitness tests and assessments can also up the fun factor and give you an edge for training and race-day success.

These days, you can find a ton of options in this realm, which can feel overwhelming, but experts caution against getting too caught up in the hype.

“Information and knowledge is a good thing, but sometimes there can be a little bit too much,” says James Robinson, M.D., sports medicine physician at Hospital for Special Surgery. He says that if you’re not having problems (like injuries or pain) and you’re hitting reasonable running goals, you probably don’t *need* any type of fitness test.

One exception: Keep up with your yearly physicals (during which you may have some blood work done) as a baseline. From there, your doctor may also suggest other specific tests (like a DEXA scan, which looks at bone density, for those with osteopenia or a history of broken bones).

That said, keep reading for what runners should know about some of the most popular fitness lab tests out there right now, how each can support your goals, and which type of runner is more likely to benefit from investing in each one.

If you’re chronically injured or looking to improve efficiency...

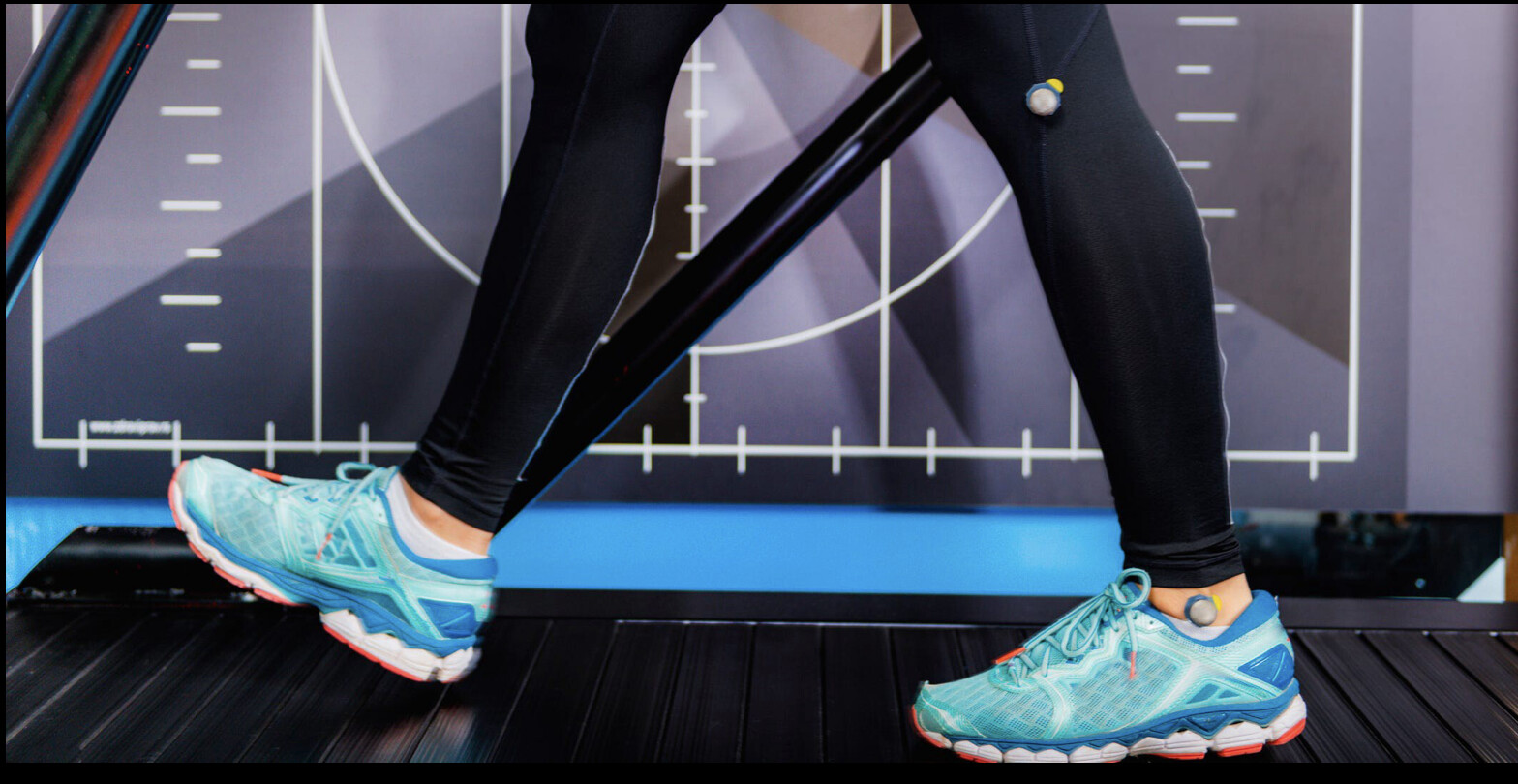

Consider a gait analysis

A gait analysis—which involves being recorded from different angles while running on a treadmill to look at form, including foot strike and body alignment—is especially useful for runners with chronic injuries like shin splints, patellofemoral pain, or IT band issues, says Robinson.

“The gait analysis can show things in your running mechanics that are making you more prone to injuries and especially certain types of injuries,” says Robinson. This analysis may also ID weaknesses or muscle imbalances and things like overstriding, overpronating, or a low cadence.

Runners looking to improve efficiency may also benefit from this test. “There can be ways to improve your biomechanics to improve your running efficiency,” like working on optimizing hip extension, which is important for minimizing vertical excursion (or too much up and down movement rather than straight ahead).

N’Namdi Nelson, C.S.C.S., an exercise physiologist at NYU’s Sports Performance Center adds that beginners can benefit from a gait analysis: “The activity you’re going to be doing is running, so why not do a running analysis to assess your biomechanics to see exactly what's going on in your gait, and identify things that you may be doing incorrectly and ways that you can improve it?” This will not only set you up for success in the sport of running in terms of performance, but help you avoid injuries before they show up in your stride.

Where to get it: Running labs like at universities and medical centers or at a local physical therapy clinic

Typical cost: Starting at about $150 (or free with your physical therapy appointment, depending on insurance)

If you’re new to running…

Consider a functional movement screening (FMS)

When doing a functional movement screen, a coach or trainer will typically put you through movements (e.g. a single-leg squat, push-up, and step-over) and watch how your body moves. If your hip drops to one side or your knees cave in on that squat, for example, that could indicate weakness in your core stability, Robinson says, which could affect your injury risk in running. The facilitator will then give you specific exercise recommendations to strengthen those weaknesses.

Nelson recommends the FMS for beginners in particular. “It’s going to give us more information as to what’s going on in the body,” he says. “So for example, if we see weakness in certain muscles or a decrease in flexibility in certain joint ranges, then we can try to get ahead of it and try to correct it, decreasing your chances of sustaining some type of running-related injury.”

Where to get it: Some places, like NYU, HSS, and the Columbia RunLab, offer running analyses which combine a gait analysis on a treadmill with a movement screen like the FMS so it’s one stop shopping. Nelson says that having information from both of these inputs—the gait analysis and FMS—can be helpful when making correlations.

You can also often get an FMS at a gym as part of an initial training evaluation, and it can be useful on its own. (If you’re choosing between a gait analysis and an FMS, Robinson argues the former is more beneficial as it’s more specific to runners.)

Typical cost: Included in the above services, with rates changing depending on insurance and/or location

If you’re more experienced and/or get sidelined by cramps…

Consider a metabolic profile test

This type of test typically includes a VO2 max test, lactate threshold evaluation, and metabolic efficiency testing. It involves a finger stick capillary blood test, as well as running on a treadmill at increasing intensity with a mask on to measure how much oxygen you’re consuming, as well as CO2 output and heart rate.

VO2 max measures your aerobic capacity. It can give you a sense of your cardiovascular fitness, which can be helpful as a benchmark to try to improve (often via short, intense intervals).

This test can also help you determine your max heart rate, and training zones based on that

“Lactate threshold is basically the point at which your body starts to go from aerobic to anaerobic and starts to really ramp up its levels of lactate,” says Robinson. “The lactate threshold basically tells a runner the pace at which they could run a short distance, like a 5K or 10K, which can be useful when you’re talking about training paces.”

Importantly, lactate threshold is something you can train and improve, Robinson adds. Knowing your threshold allows you to train in the proper zones to increase it. For example, if your lactate threshold is nine minutes per mile, then training with runs at that pace could help to improve that, Robinson says. (And then if you repeated this test months later, you can see if it improves.)

As for metabolic efficiency, Robinson says this can help you strategize fueling for long races—and it’s also trainable. This test profile measures how many calories you use per hour and the breakdown of fat versus carbohydrate at various exercise intensities.

“We have a lot of fat stores in our body, but our body has very limited carbohydrate stores,” he says. So, if the test reveals that you’re using mostly carbs for long runs, for example, you’ll run out of fuel quickly and knowing this would help you ID exactly how much nutrition you need to bring along.

Robinson says this test is most useful for runners trying to improve efficiency and pace. For example, if you want to run a sub-four-hour marathon, this test can be useful to one, see if you’re able to achieve that goal at your current fitness level, and if not, figure out which zones to train to get there.

The test can also be useful for those who deal with cramping when they run. “Usually cramps are a fueling issue more so than a true dehydration issue,” says Robinson. “So the metabolic profile can be useful for fueling to see why someone might be cramping, or for someone that hits a wall at mile 20 or 21 in the marathon, that could be a fueling issue, and the metabolic profile can definitely help clue you into strategies to help.”

Where to get it: At NYU, this test is called the “Sports Performance” evaluation and includes a gait analysis, stability and mobility screen, and VO2 max, with the option to add lactate threshold testing. At HSS, it’s Metabolic Testing and includes all of the metrics (VO2 max, lactate threshold, metabolic efficiency, and also running economy). You also may be able to find similar tests at other universities, medical centers, and running labs.

If you want to DIY…

Use your wearable data

Robinson acknowledges that many wearables now provide lots of info that you’d get as part of a formal gait analysis, like cadence, vertical oscillation, and stride length, in addition to metrics like VO2 max. “They’re pretty accurate now,” he says, adding that they can be more accessible and less expensive (assuming you’ve already paid for the wearable) than additional testing.

Still, sometimes people need help with interpretation of this data and they don’t know what to do with it on their own. “Seeing an exercise physiologist or a running coach could help them interpret some of the data,” he says.

Typical cost: Free (after the cost of a wearable, which typically starts around $200)

If you’re into lots of data and optimizing health…

Consider a blood panel

As long as you pass your yearly physical, additional blood work probably won’t tell you much more about your running performance, according to Nelson. “You can identify some nutritional deficiencies and things like that that may affect your performance, but those things may also be highlighted in your yearly physical,” he adds.

However, for those really into data and optimization of health and performance, a full blood panel might be helpful, so long as you know what to do with the information (or have someone to interpret the results). This additional screen may look into nutritional biomarkers beyond your typical blood test at a physical, like omega-3 levels, electrolytes like calcium and magnesium, and many other health-related metrics that are related to heart health, immune regulation, and more.

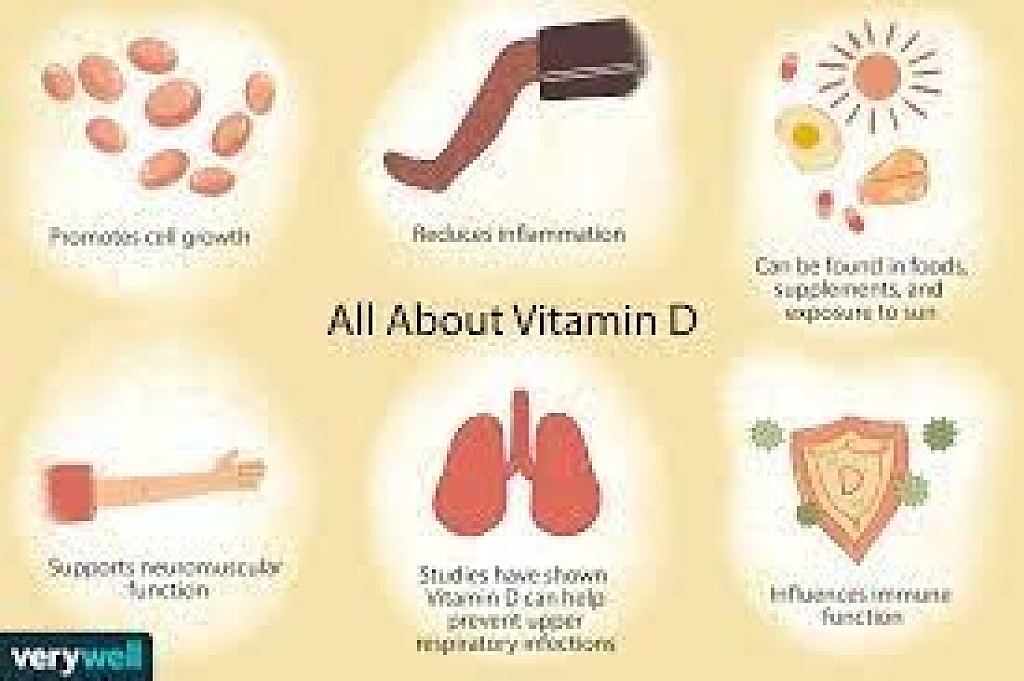

The one biomarker both experts agree is wise to get tested for all runners is vitamin D. “I do recommend that runners get their vitamin D checked regularly because if you are low in vitamin D, then that can put you at risk for bone injuries such as stress fractures, and vitamin D deficiency is extremely common, especially in places where you don’t get as much sunlight,” says Robinson.

Other than that, if you’re having specific issues or have concerns about your overall health, consult with your doctor to see what biomarkers, if any, should be tested.

Where to get it: Your doctor should be able to run additional lab tests if you have a medical need for them, but you can also try a direct-to-consumer service like Function or Inside Tracker.

Typical cost: Free one time a year with most insurance providers (for the basics), but around $500 for the DTC services.

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

How to Maintain Your Running Fitness When an Injury Has You Sidelined

Follow this expert advice to avoid losing all those aerobic gains.Whether you’re nursing a serious injury, dealing with a nagging illness, or you’re too swamped with a busy schedule, every runner now and then comes up against a setback that keeps them from their regular pavement-pounding routine. A little time off won’t hurt you (in fact, some R&R might be just what the doctor ordered). But trade in your sneakers for the sofa too long and your fitness will quickly take a nosedive.

While a few factors play into exactly when your fitness declines, like your fitness level before you took time off and whether you stop exercising completely, metabolic changes can happen within just two weeks, Jeff Gaudette, owner and head coach at RunnersConnect tells Runner’s World.In 21 days of no activity, older research has found a 7 percent reduction in VO2 max, a marker of your fitness. That might sound negligible, but it could add minutes to your race times, Gaudette says. Newer research published in 2022 backs this up, saying VO2 max can decline as much as 20 percent after 12 weeks.

But good news: Taking a total break from running doesn’t mean you have to wind up totally out of shape. Keep reading for expert tips about the best ways to cross-train, including the best non-weight-bearing exercises to do to keep up your aerobic fitness when you can’t handle impact. Plus, learn exactly what you should put on your calendar for the weeks you need to take off.

One important note: If you are injured and need to stay off your feet, make sure you get your doctor’s clearance before

Recognize When It’s Time to Take a Break from Running

A lot of times, you can run with various aches and pains as long as you’re giving yourself some TLC as you work through them—though it’s always good to check in with a doctor to be sure it’s safe to keep running. But there are, of course, injuries that require time off.

Stress fractures are the most common injuries that sideline runners for extended periods of time, says Anh Bui, D.P.T., C.S.C.S., a former collegiate runner, physical therapist, and biomechanics specialist in Oakland, California. “The other reason someone may need to take time off is tendon ruptures, usually partial, which can require immobilization or surgery,” she says.

How long you have to take off with any injury will vary. Times even vary with a stress fracture, though you can expect to hang up your running shoes for at least a month and a half. “Time off from running depends on the location of the stress fracture and the severity, which we usually determine with an MRI,” says Bui. Fractures in the tibia (i.e., your shinbone) typically require six to eight weeks of rest, for example, while one in the femoral neck (at the top of your thighbone) takes 12 to 16 weeks of rest to heal. (A stress fracture in the latter is rare, accounting for only 3 percent of sport-related stress fractures, but is most common among long-distance runners, according to a 2017 review from the U.K.)

Whatever time off your doc recommends, you have to stick to it, says Bui: “Run on a stress fracture too soon and you’ll risk delaying and complicating the healing process.”

Figure Out the Type of Non-Weight-Bearing Exercise That Works for You

You might think there’s no cardio quite like running. But many other workouts can keep you in good aerobic shape while also going easy on your joints. “The best activities are going to be the ones that mimic running the most,” says Gaudette.

His number-one pick is aqua jogging if you have access to a pool: It gets your heart rate up, mimics the posture and movements of running on dry land, and is non-weight-bearing. “Your pool-running form is like your regular running form, except you have a little more upright posture and lift your knees a little higher with less back kick,” he notes. If a pool isn’t in the cards, time on the elliptical is a close second (in terms of form).

If your doc nixes all weight-bearing exercise, riding a bike or swimming are also good choices, says Gaudette. Cycling in particular helped improve 3,000-meter running performance and hip extensor strength among high-school runners in a 2018 study in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

And when deciding what activity to fill your schedule for your weeks without running, it’s also important keep in mind what you enjoy, Gaudette adds: “If getting in the pool is logistically difficult or you hate it, but you love biking, then getting on the bike consistently is the better option.” Just be careful to stay seated on the bike: “Cycling is considered to be non-weight-bearing unless you ride out of the saddle,” adds Bui.Consider this more extension list of non-weight-bearing exercises to determine what’s right for you when you can’t run:

Aqua jogging

Cycling

Swimming

Rowing

Seated exercises

How to Schedule Cross-Training to Maintain Your Fitness

Look at the calendar and pencil in the runs you’d normally be doing—noting mileage or time, intensity (whether it’s an easy run or sprint workout, for instance). Then go back over the days and mark in what activity you’ll do in place of the run, aiming to move for the same amount of time you would’ve spent on your feet and hitting the same effort level.

“So, if you run for an hour four days per week and one of those sessions is a harder workout/effort, I’d do the same with your cross training,” advises Gaudette. “Most people should be able to jump into this on week one.”

If you tend to gauge your effort by heart rate, it’s okay to keep that up—but it can be a little tricky because your heart rate can differ depending on the type of exercise you’re doing, says Gaudette. “In the pool, your heart rate is lower due to the water, and on the bike it can be harder to get your heart rate up because you’re not using your arms,” he explains. “RPE works just as well and is easier to adjust to different situations.”

Consider the Importance of Strength Building

You’ll want to add in a couple strength sessions per week, though you might need to take a couple weeks off before you do so; make sure to talk with your PT or doc about when you can start and what exercises to include, says Bui. A physical therapist should offer up moves to help you rehab that you can regularly include in your routine. Keep in mind that if you need to do non-weight-bearing exercises that would include only moves you perform while sitting or lying down.

If you have an injury like a stress fracture, consulting with your medical team is important because “the type of strength exercise you should do depends on the location and severity of your fracture—for instance, squats are not advised for someone on crutches recovering from a femoral neck stress fracture but can be okay for someone with a stable tibial stress fracture,” says Bui. (In any case, it’s best to work with a PT for any type of fracture.)

Working in some plyometrics the last couple weeks before you plan to run again is also a good idea, Bui adds, because it preps your body for the impact of running. But don’t do plyometrics before getting clearance from your doctor.

Bui also recommends scheduling time for mobility work. “Maintaining range of motion is extremely important when you have to be non-weight-bearing,” she explains—especially if you’re using crutches or a boot, which can cause joints to stiffen and muscles to atrophy. Talk with your PT for mobility drills and schedule a little time to work on them daily.

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

THE TRUTH ABOUT RUNNING AND WEIGHT LOSS

When approached realistically, running can be an excellent tool for weight loss and weight management, but don’t be fooled by the numerous myths surrounding them

People often start running to drop a few pounds. Hopefully, they fall in love with it, move beyond the number on the scale and continue running for its many other benefits; but for many people, it’s impossible to decouple running from the weight-loss goal. When done correctly, running can help people struggling with excess weight to shed pounds—and continuing to run can be effective way to keep them off. But the subject of running and weight loss is fraught with mythology. We delve into some of the problems with the weight-loss approach to running, including what actually works, what definitely doesn’t and how to keep running as part of your life, regardless of whether you lose weight.

Myth

You can run a marathon PB while dropping 10 pounds

You can do anything, but you can’t do everything. As a rule, you won’t boost performance at the same time that you’re purposely losing weight. Often, the opposite is true, says Kylee Van Horn, RD, owner of Flynutrition in Boulder, Colo. When you’re restricting your food intake, you’re unlikely to make performance gains, but unfortunately, we often equate being faster with being thinner.

“The first thing I tell a client with a weight-loss goal is that losing weight will not necessarily make you a faster runner,” adds Carla Rodriguez Dimitrescu, PhD, an Edmonton-based expert in nutrition and metabolism who works primarily as a running coach. It’s fine if weight loss is your goal—but don’t confuse it with performance, because the way that you’ll get faster isn’t necessarily the way that you’ll drop a pound a week (which should be the maximum weight you’re losing per week, unless advised otherwise by your doctor).

Myth

There is one “runner’s body”

Let’s be clear: there is no single body type that signifies “runner.” Often, people with weight-loss goals who run have a vision in their minds of the long, lanky phenotype often associated with marathoners. But runners come in all shapes and sizes—and if you run, you have a runner’s body, period.

Even in the professional sphere, there are different body types that excel at different types of running. “You would never tell a professional runner that he doesn’t look like an astrophysicist,” says Dimitrescu. “But for some reason, that astrophysicist is upset that he doesn’t look like a runner.” She adds that people have different somatotypes, which means that genetics and environment will both play a role in how running (or dieting, or strength training) changes your body. And if you really want to see how every body is a runner’s body, sign up for a local 5K race and look around you at the start.

Still, the “runner’s body” myth runs deep, and it can be hard to break free of the desire to be ultra-thin. That’s why Stevie Lyn Smith, RD, a board-certified sports dietitian based in Buffalo, N.Y., tries to focus her clients on health outcomes as well as esthetic goals. “We try to look at other goals, like running your personal best in a race,” she says. “Maybe you won’t achieve whatever physique is jammed in your mind as the ‘ideal,’ but you’re able to appreciate these non-body-focused victories.”

Myth

Lighter is healthier/faster

Here’s an oversimplified example: say you’ve had the stomach flu for a week. You’ve lost seven pounds during that time, thanks to days spent in agony. You head out for your first run since you got sick. How does it go? That’s right—dropping weight doesn’t always lead to speedy running, and while that’s an extreme example, it’s not much different from how you’d perform after a week of crash dieting.

“Slimmer is not necessarily better,” says Dimitrescu. “And too much weight loss or restriction can lead to issues like stress fractures, increased rates of illness and injury and chronic fatigue. That’s not going to make you healthier or faster.”

And unfortunately, Don Henley was right when he sang, ‘You can’t go back, you can never go back.’ If, at 46, you’re mourning your running prowess or body composition from when you were 17, you may need to come to terms with the fact that your body isn’t the same, and no amount of training or restricting will get you there. You need to find your new healthy, speedy body, says Van Horn.

Myth

Runners can lose weight faster by eliminating carbs

Skip any diet that eliminates entire macronutrient groups, says Dimitrescu. These fad diets come and go, and for someone who wants to be a healthy, optimized runner, they’re just not worth it. “I don’t like any restrictive diet that advocates for super low calories or eliminates a macronutrient,” she says.

“My priority is always that clients get plenty of protein—at least one gram per kilogram of body weight—and adequate carbohydrates. People have a fear of carbohydrates, but if you don’t eat enough carbs, you’re going to use the protein as your source of energy instead of using it to help build and repair muscle. You’re not doing any favours to your body if you don’t provide it with the energy it needs to do the work that you’re asking it to do.”

Myth

Running earns you calories

A common saying about running is that you run to eat. But really, you should be eating to run. “Don’t create a reward/punishment mentality around running and food,” says registered dietitian and runner Lindsey Elizabeth Cortes of San Antonio, Texas. “Try to focus on how you fuel and how you train as lifestyle choices and not things that need to be rewarded or punished.”

For example: it’s not, “I had a great run, so now I get to reward myself with nachos,” nor is it “I had a bad run, so now I can only eat a salad.” Instead, reframe to: “I ran, and now I’m craving nachos! Maybe I’ll have nachos with a salad.” Or, “I didn’t run, and I’m craving nachos. Maybe I’ll have nachos with a salad.”

Myth

Fasted running and intermittent fasting will speed up weight loss

Yes, fasted runs and intermittent fasting may potentially have some longevity and fitness-based benefits, but when it comes to weight loss, they’re not going to move the needle. In fact, they might be sabotaging your efforts. “For most people, things like fasted runs and intermittent fasting just equate to saving up their calories until the end of the day and then overdoing it in the evening, or using these so-called ‘healthy’ concepts to put a healthy spin on unhealthy, restrictive eating patterns,” says Van Horn. “But if you look into the research, there’s no benefit for doing fasted training for weight loss. In fact, we know that fasted running can raise cortisol levels, which can make weight loss harder.”

Intermittent fasting that takes place around your running window means that your runs aren’t being fuelled—which can both decrease your running performance and make it harder to lose weight, since you’re more likely to over-indulge later in the day. “At minimum, fuel around your workouts and during your training, so that you have enough calories on board to develop some adaptations and buffer the stress of the workout,” says Van Horn. She adds that if weight loss is the goal, you can reduce calories at meals that aren’t near your workout window. Calories should come out of meals that aren’t right before or after your runs. Lowering your portion of rice with dinner or cutting out dessert if you trained in the morning will give you greater results than skipping your post-run snack. (But keep your caloric deficit at a maximum of 500 calories per day.)

Things like fasting and fat adaptation (training your body to optimize fat over glycogen for fuel) may sound like they’re about weight loss, but the reality is that neither is likely to help you lose weight. Some research has found that when done under the right conditions, they might increase certain health markers or improve longevity, but they’re not the weight-shedding tools you may think they are.

Myth

The more you run, the more weight you lose

The natural inclination of someone who wants to lose weight by running is to run longer. Usually, the idea of training for a marathon or half-marathon gets floated around. But running shorter routes, with some harder efforts thrown in, will lead to better weight loss outcomes, because you’re able to get the benefits of the run cardio without as much stress on the body. And because the more you run, the more you need to fuel, chasing higher mileage is actually a bit of a fool’s errand, where weight loss is concerned.

“Endurance sport is not a weight management tool,” says Smith. “Volume-wise, if you’re running more than 10 hours a week while also working a normal job, spending time with family, dealing with all of those normal responsibilities, the long-term stress of that is not going to be conducive to weight loss. With a more appropriate training load for your current lifestyle, it’s easier for you to manage stress, and you’ll see better results.”

Myth

The number on the scale is the only number that matters

Rather than focusing on your weight in pounds, look at different metrics. “I like a combination of measurements with a soft tape measure, how a certain item of clothing fits, and scale weight done once a month,” says Van Horn. While body composition-measuring tools like a DEXA scan are often considered the gold standard, they are expensive and often difficult to access, so rather than spending time and money on that, focus instead on simple measurements that are replicable.

Daily weigh-ins are also a mistake, says Van Horn. Our bodies fluctuate from day to day, so scale weight on a daily basis can be disheartening. Instead, shift to weekly or monthly and look for a general trend rather than placing any importance on half a pound.

Finally, it’s not all about your body weight or size. Dimitrescu recommends looking at fitness and health markers, such as your resting heart rate, blood glucose levels, and HDL and LDL cholesterol. Often, these markers will improve quickly once you adopt a running habit and focus on healthy eating, and can help you see that even if the number on the scale isn’t changing, your body is.

In fact, research has shown that a focus on getting into the habit of running regularly actually is more effective for long term weight loss than focusing on the number on the scale—so it may be worth shifting your focus to the number of times per week you’re physically active, or minutes spent moving.

Login to leave a comment

Why older runners need to strength train and how to get started

There’s no way to stop time, but strength training will help you run stronger for longer. Strength training is particularly important for older runners, as it helps counteract age-related muscle loss, enhances bone density and improves overall stability, reducing the risk of injuries and promoting longevity. Here’s what you need to know to run long and strong.

Combat age-related muscle loss

One of the most significant concerns for older runners is the loss of muscle mass. Scientific studies consistently emphasize the effectiveness of strength training in combating this age-related decline. Resistance exercises like weight-lifting trigger muscle protein synthesis, promoting the growth and maintenance of muscle mass. Not only will this improve running performance, it also plays a crucial role in supporting overall mobility and reducing the risk of injuries.

Enhance bone density

Aging often brings a decline in bone density, increasing runners’ susceptibility to fractures and injuries. Strength training is a powerful ally in maintaining and enhancing bone density; weight-bearing exercises stimulate bone-forming cells, leading to stronger and more resilient bones. For older runners, this means a reduced risk of stress fractures and a safeguard against the impact-related challenges that can accompany running over time.

Boost your metabolism

Metabolism tends to slow down with age, contributing to a potential decline in energy levels. Strength training, particularly high-intensity interval training (HIIT), can rev up the metabolic rate. This not only aids in weight management, but also provides older runners with the energy needed to tackle longer distances. As your running efficiency improves, your overall performance is enhanced.

Get started today

No idea how to begin? If you have access to a local gym, it’s a great idea to invest in one or two sessions with a trainer to get used to the equipment and learn a few exercises you can do on your own. There are plenty of ways runners can work on strength at home, though, and YouTube has many videos that are useful to help figure out how to strength-train at home correctly and safely.

Try bodyweight exercises such as squats, lunges, push-ups, and planks, which require no equipment and effectively target key muscle groups for runners.

Incorporate resistance bands for added challenge; they’re affordable, versatile, and can be used for exercises like leg lifts, lateral leg raises, and upper body workouts.

Start with a set of light dumbbells for exercises like bicep curls, overhead presses and weighted lunges, gradually increasing the weight as you get stronger.

Incorporating some strength training into your routine doesn’t have to take a lot of time–even fifteen minutes after a run a few times a week will make a real difference.

by Keeley Milne

Login to leave a comment

Five nutrition rules runners can forget

Proper nutrition can make a big difference to your running performance, but there are a lot of myths out there that can derail your efforts for a new personal best. These six nutrition “rules” are probably doing more harm than good, and we’re here to tell you it’s time to forget about them.

1.- Fasted runs will improve performance

There is some evidence to suggest that doing some of your runs in a fasted state will improve your body’s ability to use fat for energy rather than glycogen (which is stored carbohydrate), which is good for endurance. But for most (especially female) runners, this is likely to decrease their performance during workouts.

As Dr. Stacy Sims explained in this interview, women’s bodies already preferentially use fat and protein for fuel. Because of this, fasted training in women increases cortisol levels, causing a cascade of poor adaptation, fatigue, depression, anxiety and a build-up of body fat.

If you run early in the morning or prefer not to have a lot of food in your stomach when you run, don’t fret. Even just something small like half a banana or a piece of toast 10-20 minutes before you head out the door is all you need to bring your blood sugar up and decrease your cortisol levels.

2.- Gluten is bad for you

Unless you have celiac disease or a gluten allergy, this is simply not true. The gluten-free diet has risen in popularity over the last decade, but in many cases, it is actually less healthy than a standard diet, due to the often highly-processed nature of many gluten-free foods. If you’re experiencing GI distress and you think gluten might be the problem, talk to your doctor. They will be able to rule out other potential causes of your discomfort and help you resolve the issue.

3.- You need supplements to meet your nutrition needs

If you have diet restrictions, you may need some supplements to meet your nutrition needs, but otherwise, you can get everything you need from a healthy, well-balanced diet that contains plenty of fruits and vegetables. If you think your diet may be lacking, consult a dietitian (preferably with expertise in sports nutrition). They can assess your current eating habits and work with you to ensure you’re meeting your nutrition needs through whole foods. Then they can make supplement recommendations based on your goals and your lifestyle.

4.- You should never eat white bread or white rice

Fibre is an important nutrient, and many well-meaning runners have banished all non-whole-grain foods from their diets in the name of optimal health. The truth is, foods like white bread and white rice often do have a place in a runner’s diet and can provide a quick source of energy ahead of a big run or workout. Running can also be hard on your gut, and for some runners, too much fibre can exacerbate already-existing GI issues. Plus, eating fibre-rich foods too close to a run can cause GI distress, even for runners with strong stomachs. So while whole-grain, high-fibre foods are an important part of your diet, don’t be afraid to reach for the white rice once in a while.

5.- You need to watch your calorie intake to stay lean and fast

Countless runners have fallen prey to the “lean equals fast” mentality, but not only is this not true, it will ultimately decrease your performance, and it’s also potentially dangerous. Runners should always focus on consuming plenty of calories to fuel their training. Underfuelling will likely cause your performance in workouts to suffer, and is likely to lead to injuries like stress fractures and burnout. Listen to your body and eat whenever you’re hungry (and don’t skimp on healthy carbs). If you’re having trouble eating enough to keep up with your training, talk to a dietitian, who can give you strategies to ensure you’re fuelling properly.

by Brittany Hambleton

Login to leave a comment

Molly Bookmyer who overcame cancer now challenges TCS Toronto Waterfront Marathon

Marathoners endure much suffering in order to excel in their sport but few have struggled with brain cancer.

American Molly Bookmyer underwent two surgeries eight years ago following a diagnosis of a brain tumor while finishing up her degree at Ohio State University.

With that awful period behind her now, as an elite marathoner, her path has led her to the 2023 TCS Toronto Waterfront Marathon where she, and a growing number of American elites, will attempt to qualify for the 2024 US Olympic Trials, to be run in Orlando, Florida on February 3.

Her current best is 2:31:39 and she sees Toronto Waterfront – her first international race – as an opportunity to knock off a significant chunk of time.

“I want to run 2:27,” she reveals. “I feel I haven’t had a breakthrough in my marathon I have had some good races at shorter distances. I ran a 1:10:51 half marathon last fall. So I have had some success at the shorter distances and I haven’t quite figured out the full marathon distance yet.

“My first goal is to get the world championship standard and the second goal is to get the Olympic standard.”

Bookmyer graduated from Ohio State in 2013 with a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration, Management and Operations. While she was a member of the Buckeyes’ cross-country and track teams she was not a scholarship athlete. Now she has a better understanding as to why she was limited.

“I was a walk-on at OSU. I got better but I wasn’t a star in college,“ she explains. “When I look back at it, it was probably because I was sick at the time. I didn’t know I had a brain tumor. I competed on the team but my times weren’t spectacular. I lettered in cross country and track but I wasn’t All American and I didn’t make it to the NCAA’s.”

A series of stress fractures also held her back and it was by a stroke of luck that the tumor was discovered.

“In different blood tests to try to find why I got stress fractures they found one of my hormones prolactin was high,” Bookmyer says. “This (hormone) is associated with tumors near your pituitary gland. They did a scan and they found the tumor in my ventricle. It was kind of luck. I probably had symptoms but thought it was normal.”

Following the diagnosis she underwent a spinal tap to determine if the cancer cells were in her spinal column. Fortunately, it came back negative. But the surgery to remove the growing tumor was vital.

Originally from Cleveland, she moved to Columbus to study at OSU and remained there ever since. That’s also where she met her husband, Eric.

Immediately after graduation she worked for the Abercrombie & Fitch company. Then, having dealt with her own serious illness, Eric was diagnosed with testicular cancer. Running was helpful in both relieving the stress of being a full-time caregiver to him as well as helping in her own recovery.

“I am healthy now,” she says through a smile. “I get a brain scan every year. It used to be every six months. After the first surgery I had complications from the surgery. The tumor has not come back.

“Eric just had his 5-year checkup, He had a couple of surgeries and ‘chemo’ so now he is healthy as well, I guess we are lucky we went through a lot and came out the other side healthy.”

Two years ago she was recruited by one of her former contacts at Abercrombie & Fitch to work for Hawthorne Gardening Company which is involved in the hydroponics industry selling lights, pots, containers, benches and other gardening equipment in both the cannabis and general botany industry. Most importantly, the job allows her to work remotely, something that helps while training full time.

Down time is limited but she says she enjoys spending time with Eric and her dog Cooper. Listening to music is another relaxing pastime with Rob Thomas of Matchbox Twenty remaining a favorite. With the Toronto Waterfront Marathon rapidly approaching she is confident she will perform at her best on the big occasion.

“Training is going really well,” Bookmyer declares. “I had a little setback in the spring. I tore my plantar fascistic but that’s fully healed. My mileage has gone to 115 to 120 miles (185km – 193km) a week which is higher than I have been before; paces are good, I am feeling strong. I am excited for what that means.”

by Paul Gains

Login to leave a comment

TCS Toronto Waterfront Marathon

The Scotiabank Toronto Waterfront Marathon, Half-Marathon & 5k Run / Walk is organized by Canada Running Series Inc., organizers of the Canada Running Series, "A selection of Canada's best runs!" Canada Running Series annually organizes eight events in Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver that vary in distance from the 5k to the marathon. The Scotiabank Toronto Waterfront Marathon and Half-Marathon are...

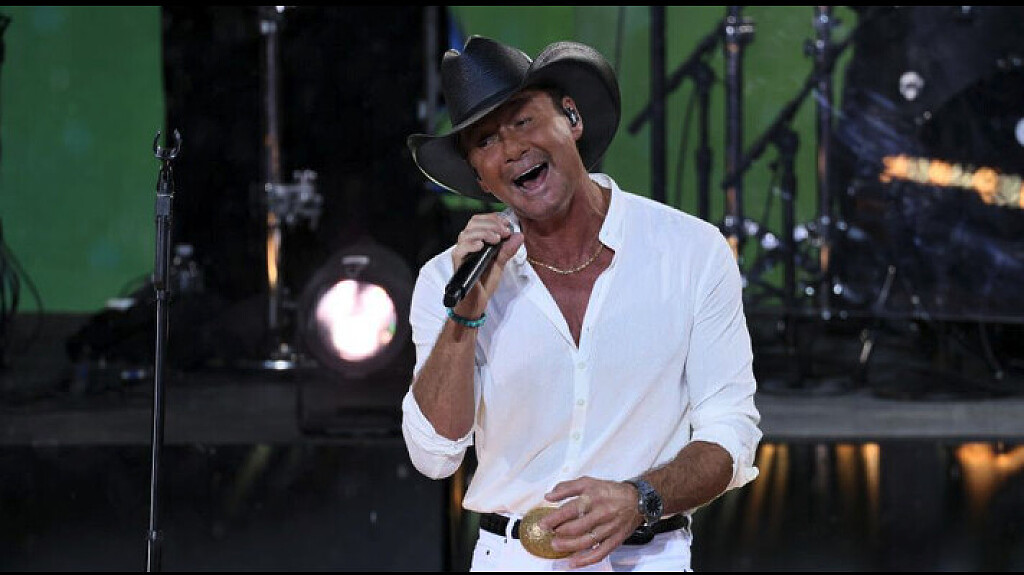

more...Tim McGraw Used to Run 7-8 Miles Before Every Concert

Once a runner—the country artist misses his mileage, but he still walks for an hour every day.

Country musician Tim McGraw is a former runner whose pre-show routine used to include running seven to eight miles to clear his mind before playing to crowded auditoriums.

In an interview with Entertainment Tonight Canada, the three-time Grammy Award-winning artist shared that he’d still be running today—before the shows on his current “Standing Room Only” tour—if he weren’t so injury prone. McGraw says he’s broken his foot three times, and had two knee surgeries and an elbow surgery to boot. He can no longer run and misses getting in his miles. Instead, he now starts each day with an hour-long walk, and he makes sure to go for a stroll before he performs onstage.

It’s not just running that’s taken a toll on McGraw’s body though. In 2011, he landed himself in a boot with two stress fractures caused by “too much spearfishing and beach volleyball,” as the singer-songwriter wrote on Instagram at the time. The same year, he broke his foot while on tour for his “Emotional Traffic” album and performed wearing a cast.

He told CMT, “I don’t know if it happened running or in the part of the show where I jump off speakers. It could’ve happened any number of ways. It hurt for a while, and I kept running and kept working out and kept doing shows. For a couple weeks, it just kept getting worse and worse, and it finally got to where I couldn’t walk, and it was really swollen.”

Even without running in his life, the 56-year-old continues to maintain a rigorous exercise regimen. He played sports growing up, then fell out of shape. Around 2008, he gave up alcohol, burgers, and “truck stop food,” and got excited about working out again. He even opened his own gym in Nashville in 2019 and has written a book about his late-career fitness transformation.

It pays dividends on tour, too, with all that cavorting around with a guitar and mic. He uses his whole body to sing, and as he told Men’s Health, “having more control over those things makes my voice stronger.”

He continued, “I don't really get tired of training. There’s such a feeling of accomplishment that comes from the feeling of being my age and still being at the top of my game.”

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

Why Carbon-Plated Running Shoes Can Lead to Injury

Ten Non-plated running shoes that let your feet move freely, provide stable cushioning, and deliver a fast, agile ride

The advent of supershoes has transformed the running shoe world in every category, none more than the class of shoes that used to be called lightweight trainer-racers. Rather than low, flexible, relatively firm shoes, the majority of up-tempo shoes now have a thick stack of light, bouncy foam with a curved carbon or plastic plate embedded in the midsole. Shoes without a plate are now defined by its absence. But concerns continue to grow about injury risk in carbon-plated shoes, and a growing number of models are eschewing the high-stack-with-plate trend and reviving the simple up-tempo shoe category with modern touches.

Besides not having a plate, these shoes share other characteristics. Like supershoes, they all feature advanced midsole foams that are ultra-light and hyper-responsive. Unlike supershoes, however, they all have relatively low stack heights and tend to be built on wider platforms, both of which enhance their stability. They also all have a flexible forefoot (rather than a rigid, rockered one), svelte uppers that have just enough structure to hold the foot in place, and price tags that run around $100 less than their supershoe siblings.

If plated super racers and trainers are indeed super, allowing you to run faster with less effort, why would anyone want anything else? The answer has two seemingly contradictory parts: 1) to avoid the excess stresses and accompanying injuries that supershoes can cause, and 2) to allow the natural training stresses that supershoes reduce, in order to build stronger, more robust feet and lower legs.

The problems start with supershoes’ thick, bouncy, sole that propels you forward, but can also throw you sideways. “Running in supershoes is a much less stable environment,” says Jay Dicharry, physical therapist, biomechanical researcher, and professor at Oregon State University. “If you have really good alignment and foot and ankle control, you might be OK, but if not, a supershoe will greatly magnify your instability. You’ll wind up with a considerable increase in stress—and if you have something borderline, it might push you over the threshold.”

Amol Saxena, a leading sports podiatrist in Palo Alto, California, also points out issues with the prescriptive rigidity of the plates. “The problem with the carbon-plated shoes is that your foot is individualized, and the carbon plate is not,” Saxena says. “So if the shape or length of your metatarsals line up differently than where it has to bend, or your plantar fascia is less flexible, you can get stressed in those areas—that’s why people are breaking down. I’ve had people break or tear things just in one run in the shoes.” The more flexible plates found in many super trainers reduce some of this stress, but these shoes are still tuned to optimize specific strides and don’t let the foot move freely in its preferred patterns.

Research has also shown that running in supershoes changes your form: It decreases your cadence, increases stride length and peak vertical forces, and alters foot mechanics. All these add stress to joints. “When you put a supershoe on, you basically have a trampoline,” Dicharry says. “It’s going to compress and rebound, and creates a different rate of loading to muscles and joints.” While no studies to date directly demonstrate that supershoes cause injury, evidence links them to stress fractures, plantar fasciitis, achilles tendinopathy, and other foot and lower-leg issues.

Paradoxically, while supershoes’ unstable platform and rigid plates can add excessive stress, their performance-enhancing rebound can also remove some of the training load. Supershoes lower the load at the ankle and foot, reducing the work they have to do and making running easier in the short-term, but simultaneously removing some of the stimulus for your body to adapt and grow stronger in the long-term. “If you run in supershoes exclusively, you’re going to end up with a bunch of deficient runners prone to injury—runners with less springy tendons, weaker tendons, and lower bone density,” Dicharry says.

The solution is to wear a variety of shoes in your training. “It is good to use different stack heights and flexibility,” Saxena says. “Plated shoes should be a training tool as well as for races—but how much depends on the runner.” You want to train some in the shoes you’ll be racing in, to let your body adapt to their unique stresses and stride patterns. But training in more flexible, less-bouncy shoes has been shown to improve running economy and build the strengths you need to handle the unstable rebound of supershoes. “If you want to run in super shoes you need to put the work in to show up with stable parts,” Dicharry says.

Fortunately, I don’t find training in these shoes a chore. They may not be performance-enhancing racers, but they are light, nimble, stable, and make my feet feel connected, engaged, and alive.

After having run in dozens of shoe models released this spring, I selected those that fit in the category and ran in a different shoe every day for six weeks—on asphalt, concrete, and dirt roads. I did at least one daily run and speed workout in each, ranging from 100-meter pickups to VO2-max intervals to tempo runs. Despite their similarities, each shoe has a slightly different ride and significantly different fit, so it’s worth trying out a few before buying. All of these models will serve as an excellent trainer for easy daily runs, interval workouts, tempo runs, and occasionally going long.

by Outside Online

Login to leave a comment

Four ways hitting the trails can benefit road runners

Nothing rouses a runner’s self-discipline quite like training for a road race. Whether it’s preparing for a 5K or a marathon, getting in the best possible shape for the big event usually means setting a clear training schedule and sticking to it.

While challenging oneself to stay fully committed to a plan during weeks and months of tough sessions has a certain appeal, becoming overly obsessed with hitting every target on the calendar can turn training into a mental and physical grind. As road-race training plans tend to focus exclusively on road and track work, the lack of variety in sessions can make training feel even more taxing.

Adding the occasional trail run to a road-race training schedule can be a great way to keep training fresh without having to sacrifice crucial road or track sessions. You can tuck a trail run seamlessly into an existing training plan by scheduling it on a dedicated easy-run day, or on days when the schedule gives the option for either a rest day or an easy run. However it best fits best into the schedule, here are four reasons road runners may want to consider taking the odd trip down the trail.

1.- Enhanced stability and strength

Navigating hills, rocks and uneven terrain on trail runs forces runners to engage a wider range of muscles, including those in the glutes, hips and core, which are often neglected during road running. Further developing these muscles can help runners enhance stability, power and injury prevention–benefits that can reap rewards as runners progress in their road training.

2.- Reduced impact on joints

Trails generally have softer surfaces, such as dirt or grass, which reduces the impact on joints and can help prevent injuries like shin splints. A recent study found adding too many fast kilometres too quickly, as can happen in speed-focused road and track sessions, is more likely to lead to tibial stress fractures than taking on the steeper, slower climbs associated with trail running.

3.- Improved aerobic fitness

The generally slower pace of trail running lends itself to training at an easier effort, which can strengthen aerobic capacity. Training in the aerobic zone can help increase the body’s ability to take in, transport, and use oxygen, leading to improved running performance and greater endurance capacity.

4.- Greater mental stimulation

The changing scenery and the need to focus on the trail can offer a mental escape from the monotony of running only on the road. It can be an engaging and exciting experience that helps alleviate boredom and keep the mind sharp. Trail running allows you to explore new areas, discover hidden gems and become immersed in nature’s beauty.

by Paul Baswick

Login to leave a comment

Tips for returning to speedwork after injury

Returning to running after injury can spark intense feelings of both joy and fear. Any runner who has been sidelined for a seemingly endless stretch of weeks or months has felt the elation of finally being able to slip back into their running shoes, head out the door, stretch their legs and feel their spirit soar. But a rebound from injury can also be riddled with doubts: is it too soon to start running again? Am I going to retrigger the injury? Can I ever get back to being the runner I was before I got hurt?

Uncertainty and uneasiness tend to ramp up in step with training intensity, making a return to speedwork that much more of a mental challenge. With speedwork being an important part of training for any distance, from track events to ultramarathons, the time eventually comes for the fully recovered runner to get back up to speed by reintroducing some intervals into their training. If you’re an injured runner on the road to recovery, or if you’ve recently returned to action but find yourself stuck in a slower gear, consider these tips for safely reintroducing speedwork into your training.

Let your caution be your guide

It’s important to remember feelings of apprehension you may have about upping the intensity of your runs are natural, and are likely serving you well. Erring on the side of caution is key when returning to running, especially when the focus is on speed. Appreciate the uneasiness about returning to speedwork as the inner voice of wisdom that it is, instead of mischaracterizing it as irrational worry. Your instincts to be very careful about speedwork are supported by science: a recent study, for example, found adding too much speed in training too quickly is more likely to lead to stress fractures than is running tough uphills and downhills. As the researchers of that study noted, the lesson for runners isn’t to stop doing speedwork, but to approach it with the appropriate patience and care.

Consult a health-care professional

Before resuming any intense training or speedwork after an injury, it’s crucial to consult with a health-care professional, such as a physiotherapist or sports medicine specialist. They can evaluate your condition and provide specific guidance tailored to your injury and recovery progress.

Begin with a proper warm-up

Begin each speedwork session with a thorough warm-up to prepare your body for the increased intensity. Incorporate dynamic stretches, light jogging and mobility exercises to gradually raise your heart rate and loosen up your muscles. This helps reduce the risk of further injury and may enhance your performance.

Start with short intervals

When reintroducing speedwork, start with shorter intervals rather than long, intense efforts. For example, instead of jumping straight into 800-metre repeats, begin with shorter intervals like 200 or 400 metres. This allows your body to adapt gradually to the increased pace and intensity.

Allow for adequate recovery time

Intense speedwork places significant stress on your body, so it’s essential to incorporate adequate recovery time between sessions. Give yourself at least 48 hours of rest or easy running between speedwork sessions to allow for muscle repair and adaptation. This helps prevent overuse injuries and promotes a safer progression.

Listen to your body

Pay close attention to any warning signs or pain during and after speedwork sessions. If you experience sharp or worsening pain, discomfort, or unusual fatigue, it’s important to back off and allow your body more time to recover. Pushing through pain can lead to further injuries and setbacks. Be patient and gradually increase the intensity and volume as your body allows.

by Paul Baswick

Login to leave a comment

Study finds speedwork (not hill repeats) more likely to cause stress fractures in runners

Fast efforts are more likely than tough hill sessions to lead to tibia (shin-bone) stress fractures, according to new research out of the University of Calgary. In fact, the same factors that can make hill work so gruelling might also help promote runners’ bone health.

The findings come from a study in which researchers enlisted 17 volunteers for treadmill runs up to 16 km/h, at five different slopes. Through complex modeling that also pulled information from motion-capture testing and a database of computerized tomography (CT) scans of volunteers’ tibia bones, researchers were able to get insights into the type of running that places greater stress on the tibia, which in turn is more likely to result in a stress fracture.

“I’ve really been interested in running biomechanics, and in particular, understanding why people get injured,” says Michael Baggaley of the University of Calgary’s faculty of kinesiology. He tells Canadian Running that although the link between increasing training intensity and a greater risk of tibial stress fractures is well established, he and his team wanted to understand what specific aspects of training were more likely to result in injury.

“We didn’t really see a difference in the damage potential when you run uphill or downhill relative to running on flat ground,” Baggaley says of his team’s findings, “but changing the speed that you run at really did change what we consider the damage potential.”

He suggests the body’s response to the challenge of running uphill helps protect runners from shin-bone stress.

“It can be counterintuitive, because uphill running is very exhausting, really taxing, but when you run uphill, you tend to run with a very quick cadence and a very short stride length,” he says. “So it’s actually these adaptations going uphill running that minimize the loading on the bone. Inadvertently, the fact that running uphill is so tough, that it costs so much energy and oxygen, actually causes you to change the way you run into a more protective manner for our body. Conversely, when you run fast [i.e., on flat ground], you take longer strides and spend more time in the air. All that requires more force to be placed on your body.”

He says while other factors, such as previous bone injuries or malnutrition, can increase susceptibility to stress fractures, the study does make a clear connection between running faster and increasing the risk of damage to the tibia. “The faster you’re trying to run, the more likely you are to be stressing the bones to a higher degree,” says Baggaley.

The takeway for runners, he says, is to take easy runs easy, and to be careful not to introduce too much speedwork too quickly into your training. “There’s a general premise that most runners spend too much time training too fast, and most of us should spend most of our runs at an easy, conversational pace. I think the results of this work support that notion, and that many people are putting themselves at a higher risk than is necessary in order to gain the training benefits of running.”

by Running Magazine

Login to leave a comment

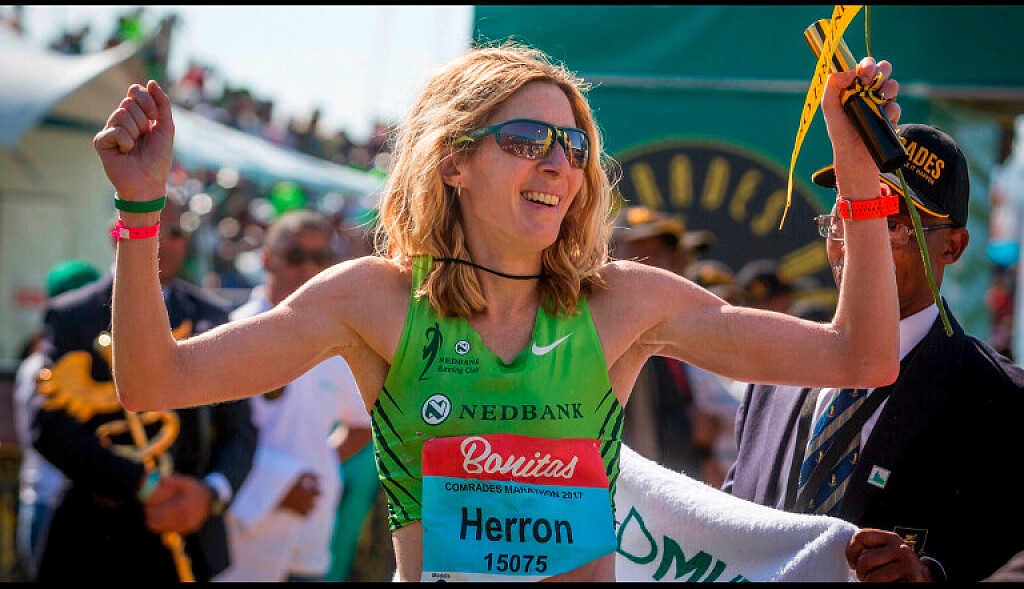

Camille Herron’s Advice: Skip the Long Run

Bones are made of dynamic tissues that need stress, just not too much, says one of the world's best ultrarunners

In January, my social media feeds were filled with the typical new year posts—year-end recaps, reflections and resolutions, and hopes for the coming year. But one tweet caught my eye.

Ultrarunner Camille Herron shared one reason why she thought she was “crushing world records” in her forties: She only does one or two long runs a month (nothing over 22 miles) and she never does back-to-back long runs. Case in point: she ran one easy 20-miler in the lead-up to the Jackpot Ultra Running Festival’s 100-mile race last year, which she won outright. Instead, she focuses on cumulative volume and running frequency.

In her words, “Long runs are overrated.”

In the world of ultrarunning, where there’s a bravado around epic big-mileage days, Herron seems like an anomaly. Among the replies to her tweet, there was curiosity tinged with a side of skepticism. How could an ultra-distance athlete—one who holds world records for 100 miles and for the longest distance covered in 24 hours—run no longer than what you’d typically do in a marathon build-up? Shouldn’t her training mirror what she’d need to do in an ultra?

Karen Troy saw Herron’s tweet too. But her first thought was, “Wow. Someone’s actually trying to do it.” To Troy, who’s a professor of biomedical engineering and the director of the musculoskeletal mechanics lab at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Herron’s training philosophy reflected what she’d read in scientific journals and seen in the lab related to mechanical stress and bone adaptation. “To me, it really aligned well with a lot of the theory,” she says.

Bone is a dynamic tissue. It changes, adapts, and gets stronger in the same way that muscles do. And in order for them to get stronger, you have to load them.

Bones have a “set point”—akin to the thermostat in your house—for the optimal amount of mechanical stress it wants to experience. Depending on the amount and rate of force transmitted through the bone, bone cells respond by either adding or removing bone. Too much force and the cells build bone to temper the load. Too little force and the cells get rid of bone so that it can sense more load.

Scientists have long been interested in finding the sweet spot between the amount of physical activity that induces adaptation and strengthens bone and the amount that can lead to injury—a fine line that many runners are intimately familiar with. What they’ve found in studies with animals like mice and rats is that, after back-to-back loading cycles, bone cells start to ignore the mechanical stress and stop adapting. Troy says it’s like when you walk into a smelly room. “It smells pretty bad for 10 to 15 minutes, and then you adapt. If you stay in the room, it stops smelling,” she says.

However, just like your nose can become re-sensitized if you leave the smelly room, bone cells do too. Studies have found that bone cells start to pay attention to mechanical stress again after a four-to-eight-hour rest period. When you spread the load over multiple sessions rather than one sustained bout, you gain more bone. (Tendons and ligaments respond similarly.)

The evidence suggests that distance running has diminishing returns when it comes to bone health. Troy hypothesizes that bone may respond to the stress of running over the first half mile or so but then become desensitized to the monotonous, repetitive loading. “You’ll get muscle and cardiovascular adaptations, but your bones aren’t paying attention anymore,” Troy says. “You’re just adding miles and potentially accumulating damage, but you’re not going to add adaptive stimulus that will help the bone become stronger.”

There isn’t a lot of data in people, making Herron an interesting case study. “Humans are made to move frequently,” Herron says. “The body responds to change and dynamic stimuli, so you need to stress the body in different ways.” It’s an approach she believes can work for runners at all levels and distances.

Her training is peppered with frequent, shorter bouts of running. Most days, Herron will run 10 to 15 miles and then doubles back for six or seven miles after a four-to-eight-hour rest period. Over a two-week period, she completes four main workouts—short intervals like 400-meter repeats; long intervals like one-to-three-mile repeats; a progression run, usually incorporated into a long run; and a hill session where she stresses both the uphill and downhill components to load her body eccentrically.

In between workouts, she runs easy and incorporates strides and drills twice a week. She likes to race a marathon or 50K a couple of weeks before a big race as a way to practice her nutrition and stress her body “just enough.”

“You can’t just look at a singular long run or back-to-back long runs. You have to look at the whole picture. Every run is like bricks that add up over time,” she says. Over the years, Herron has played around with her training formula and has cut back on her long runs, emphasizing quality over quantity and running for time rather than just distance. “I’m totally fine doing two hours as my long run,” she says.

It makes sense that Herron’s training is steeped in science. She was pre-med at the University of Tulsa before turning her focus to scientific research, studying the impact of strength training on bone and muscle. In graduate school at Oregon State, she investigated the relationship between mechanical stress and bone recovery for her master’s thesis. By studying bones, maybe she hoped to understand why she experienced multiple stress fractures in high school and college. What she learned shaped how she trains.