Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #Lance Armstrong

Today's Running News

The Rush to Discredit Greatness – Why Do We Doubt Record-Breaking Performances?

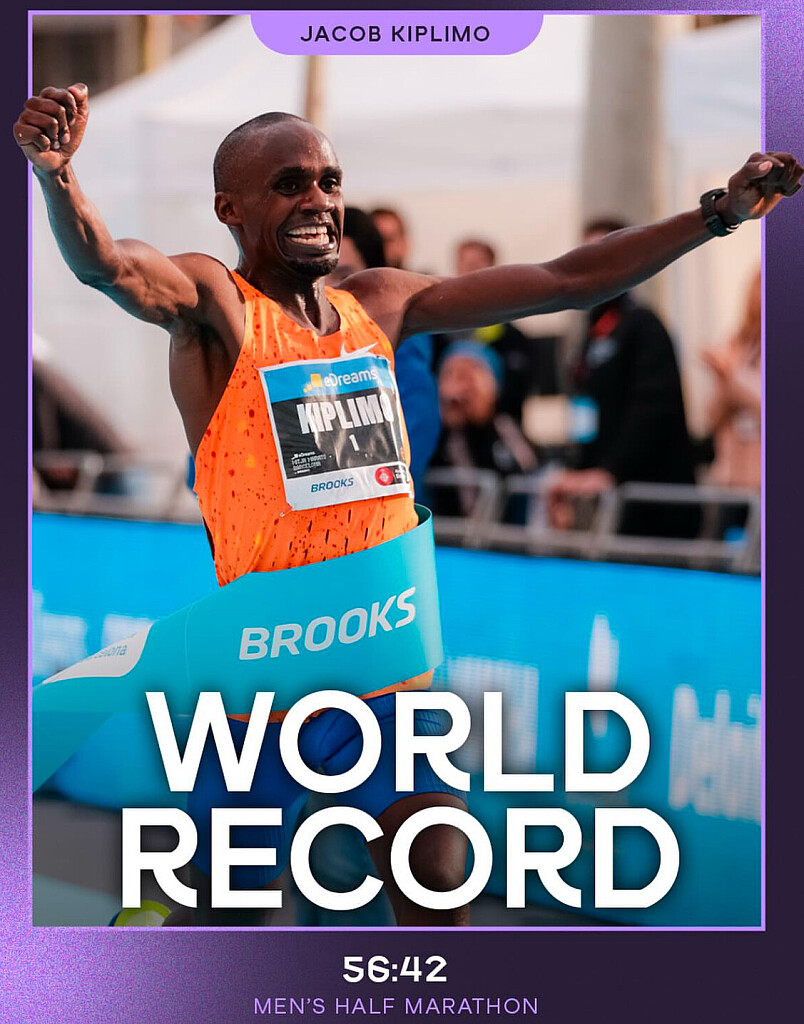

When news broke that Jacob Kiplimo had run an astonishing 56:42 half marathon, the immediate reaction on social media was a mix of awe, skepticism, and outright accusations of cheating. Many simply couldn’t believe that a human could run that fast.

By Bob Anderson, Editor of My Best Runs

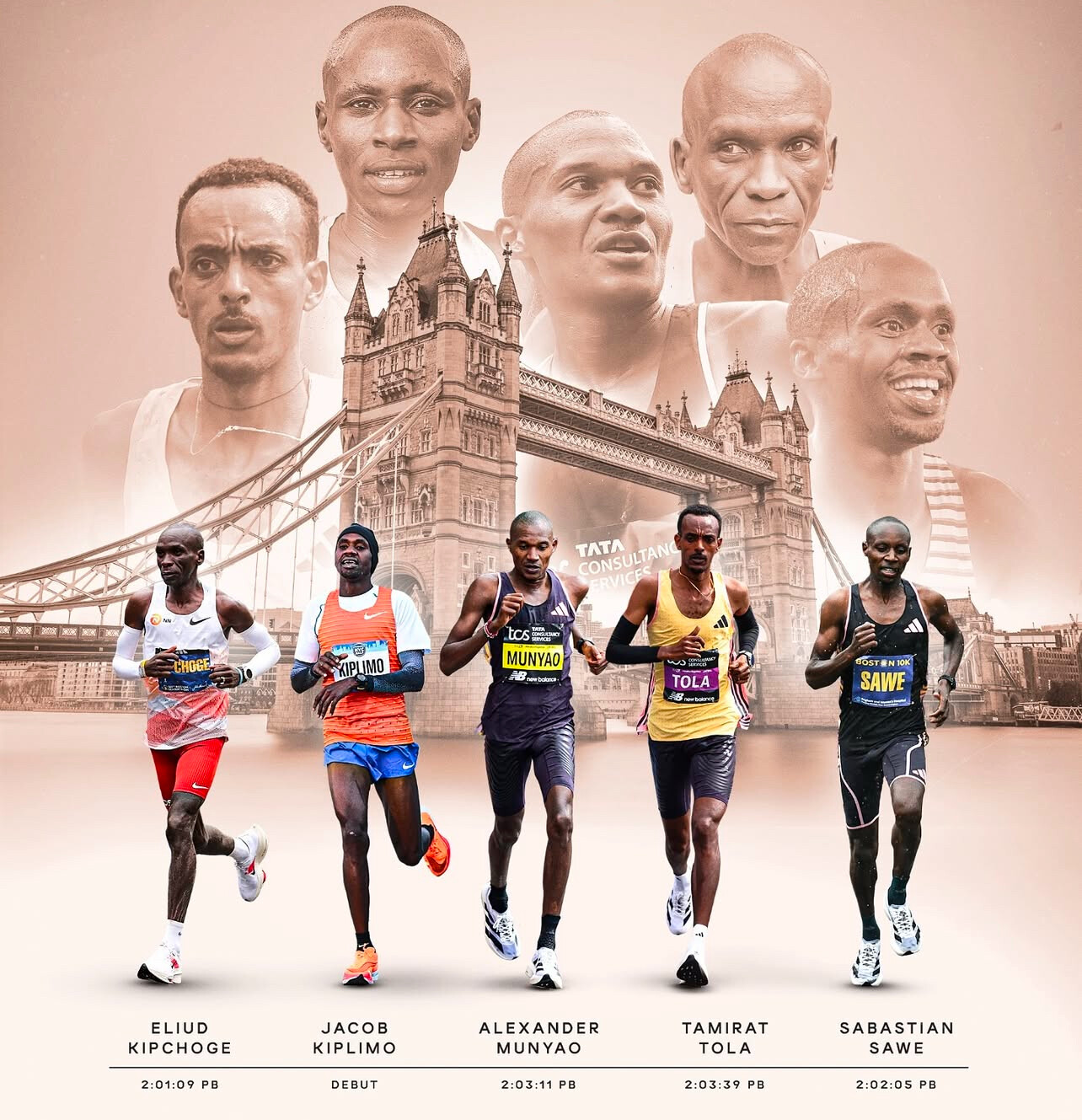

I understand why people might be shocked. This was not just a fast race—it was arguably the greatest distance running performance ever. Kiplimo’s time shattered previous records and redefined what we thought was possible over 21K. But should disbelief automatically lead to accusations?

The reality of record-breaking feats

Throughout history, incredible performances have often been met with doubt. In 1954, Roger Bannister’s sub-4-minute mile seemed superhuman, but today, elite high schoolers chase that mark. When Eliud Kipchoge broke the two-hour marathon barrier (albeit in a controlled environment), people debated how much was due to pacing, shoes, or course setup.

Now, with Kiplimo’s 56:42, we see the same pattern. Questions arise:

Was the course accurate? This will be verified before the record is ratified.

Did he use performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs)? As far as we know, he has passed every drug test, and accusations without evidence are unfair.

What about Nike’s super shoes? Yes, he wore them, but these shoes are legal under World Athletics regulations.

These are reasonable questions to ask, and the governing bodies will do their due diligence. But what’s frustrating is the knee-jerk reaction of immediately assuming foul play.

The culture of doubt in modern running

Why do some past champions and fans rush to discredit new performances? Some of it comes from personal experience—many former elite runners trained incredibly hard, and when they see times they never thought possible, it’s natural to wonder what changed. Some of it also comes from a real history of doping scandals in the sport, from Ben Johnson to Lance Armstrong to the Russian state-sponsored program.

But there’s another factor—social media. Unlike in Bannister’s era, when skepticism was confined to private conversations, today’s doubts explode instantly across the internet. A single tweet suggesting “this must be doping” spreads like wildfire, often without evidence.

Jacob Kiplimo is no stranger to records

Let’s not forget that this is not Kiplimo’s first world record. He has been at the top of the sport for years, previously holding the half marathon world record at 57:31 before Kelvin Kiptum broke it. He has consistently performed at the highest level, winning Olympic and World Championships medals. Are the same people suggesting he cheated back then too? Or is it only now, when the record has taken a dramatic leap, that they feel the need to discredit him?

Innocent until proven guilty

In sports, as in life, we must be careful about making baseless accusations. If evidence emerges that Kiplimo cheated, that’s one thing. But until then, we should celebrate an incredible performance and let the process of verification take its course.

To those quick to assume wrongdoing, I ask—what if you’re wrong? What if Kiplimo is simply that good? Greatness should inspire us, not immediately make us suspicious. Until proven otherwise, this was a historic day for distance running—one that deserves recognition, not reckless doubt.

by Bob Anderson

Login to leave a comment

New Salazar documentary questions reasons for his 2019 suspension

Nike’s Big Bet, the new documentary about former Nike Oregon Project head coach Alberto Salazar by Canadian filmmaker Paul Kemp, seeks to shed light on the practices that resulted in Salazar’s shocking ban from coaching in the middle of the 2019 IAAF World Championships. Many athletes, scientists and journalists appear in the film, including Canadian Running columnist Alex Hutchinson and writer Malcolm Gladwell, distance running’s most famous superfan.

Most of them defend Salazar as someone who used extreme technology like underwater treadmills, altitude houses and cryotherapy to get the best possible results from his athletes, and who may inadvertently have crossed the line occasionally, but who should not be regarded as a cheater. (Neither Salazar nor any Nike spokesperson participated in the film. Salazar’s case is currently under appeal at the Court of Arbitration for Sport.)

Salazar became synonymous with Nike’s reputation for an uncompromising commitment to winning. He won three consecutive New York City Marathons in the early 1980s, as well as the 1982 Boston Marathon, and set several American records on the track during his running career.

He famously pushed his body to extremes, even avoiding drinking water during marathons to avoid gaining any extra weight, and was administered last rites after collapsing at the finish line of the 1987 Falmouth Road Race.

Salazar was hired to head the Nike Oregon Project in 2001, the goal of the NOP being to reinstate American athletes as the best in the world after the influx of Kenyans and Ethiopians who dominated international distance running in the 1990s. It took a few years, but eventually Salazar became the most powerful coach in running, with an athlete list that included some of the world’s most successful runners: Mo Farah, Galen Rupp, Matt Centrowitz, Dathan Ritzenhein, Kara Goucher, Jordan Hasay, Cam Levins, Shannon Rowbury, Mary Cain, Donovan Brazier, Sifan Hassan and Konstanze Klosterhalfen.

Goucher left the NOP in 2011, disillusioned by what she saw as unethical practices involving unnecessary prescriptions and experimentation on athletes, and went to USADA in 2012. An investigation by the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency followed on the heels of a damning BBC Panorama special in 2015, and picked up steam in 2017.

When Salazar’s suspension was announced during the World Championships in 2019, he had been found guilty of multiple illegal doping practices, including injecting athletes with more than the legal limit of L-carnitine (a naturally-occurring amino acid believed to enhance performance) and trafficking in testosterone – but none of his athletes were implicated. (Salazar admitted to experimenting with testosterone cream to find out how much would trigger a positive test, but claimed he was trying to avoid sabotage by competitors.)

That Salazar pushed his athletes as hard in training as he had once pushed himself is not disputed; neither is the fact that no Salazar athlete has ever failed a drug test. Gladwell, in particular, insists that Salazar’s methods are not those of someone who is trying to take shortcuts to victory – that people who use performance-enhancing drugs are looking for ways to avoid extremes in training.

That assertion doesn’t necessarily hold water when you consider that drugs like EPO (which, it should be noted, Salazar was never suspected of using with his athletes) allow for faster recovery, which lets athletes train harder – or that the most famous cheater of all, Lance Armstrong, trained as hard as anyone. (Armstrong, too, avoided testing positive for many years, and also continued to enjoy Nike’s support after his fall from grace.)

Goucher, Ritzenhein, Levins and original NOP member Ben Andrews are the only former Salazar athletes who appear on camera, and Goucher’s is the only female voice in the entire film. It was her testimony, along with that of former Nike athlete and NOP coach Steve Magness, that led to the lengthy USADA investigation and ban.

Among other things, she claims she was pressured to take a thyroid medication she didn’t need, to help her lose weight. (The film reports that these medications were prescribed by team doctor Jeffrey Brown, but barely mentions that Brown, too, was implicated in the investigation and received the same four-year suspension as Salazar.) Ritzenhein initially declines to comment on the L-carnitine infusions, considering Salazar’s appeal is ongoing, but then states he thinks the sanctions are appropriate. Farah, as we know, vehemently denied ever having used it, then reversed himself.

It’s unfortunate that neither Cain, who had once been the U.S.’s most promising young athlete, nor Magness appear on camera. A few weeks after the suspension, Cain, who had left the NOP under mysterious circumstances in 2015, opened up about her experience with Salazar, whom she said had publicly shamed her for being too heavy, and dismissed her concerns when she told him she was depressed and harming herself. Cain’s experience is acknowledged in the film, and there’s some criticism of Salazar’s approach, but Gladwell chalks it up to a poor fit, rather than holding him accountable.

Cain’s story was part of an ongoing reckoning with the kind of borderline-abusive practices that were once common in elite sport, but that are now recognized as harmful, and from which athletes should be protected.

Gladwell asserts that coaches like Salazar have always pushed the boundaries of what’s considered acceptable or legal in the quest to be the best, and that the alternative is, essentially, to abandon elite sport. It’s an unfortunate conclusion, and one that will no doubt be challenged by many advocates of clean sport.

by Running Magazine

Login to leave a comment

Many Protests as Russia doping ban cut to two years

Russia's ban from international sport was halved to two years on Thursday and its athletes were cleared to compete as neutrals, drawing condemnation from athletes and anti-doping advocates.

The Swiss-based Court of Arbitration for Sport cut the initial four-year ban imposed by the World Anti-Doping Agency, citing "matters of proportionality" and the "need to effect cultural change and encourage the next generation of Russian athletes".

"The consequences which the Panel has decided to impose are not as extensive as those sought by WADA," a CAS statement said.

"This should not, however, be read as any validation of the conduct of RUSADA (Russia's anti-doping watchdog) or the Russian authorities."

The CAS judgement comes after WADA hit Russia with the four-year ban last year for doping non-compliance after finding data handed over from its tainted Moscow laboratory had been manipulated.

The saga first erupted in 2016 when Grigory Rodchenkov, the laboratory's former head, blew the whistle over state-backed doping at the 2014 Winter Olympics in the Russian resort of Sochi.

The shortened ban imposed by CAS runs until December 16, 2022, encompassing the Tokyo Olympics, Beijing Winter Games and the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, which ends two days later.

Russia's flag is forbidden, but its athletes will be allowed to compete in a uniform bearing the word "Russia", as long as it also says "neutral athlete", the court said.

Government representatives including President Vladimir Putin are barred, but they may still attend if invited by the host country's head of state, CAS added.

WADA president Witold Banka said he was "disappointed" that the four-year ban was cut, but still called the ruling "an important moment for clean sport".

"WADA is pleased to have won this landmark case," Banka said, adding that the verdict "clearly upheld our findings that the Russian authorities brazenly and illegally manipulated the Moscow laboratory data in an effort to cover up an institutionalised doping scheme".

'Devastating decision'

But there was strong condemnation elsewhere. US Anti-Doping Agency chief executive officer Travis Tygart, who played a key role in exposing cycling's Lance Armstrong doping scandal, called it a "devastating decision".

"At this stage in this sordid Russian state-sponsored doping affair, now spanning close to a decade, there is no consolation in this weak, watered-down outcome," Tygart said.

He called it "a catastrophic blow to clean athletes, the integrity of sport, and the rule of law" and, in an interview with AFP, said the ruling was a "tragedy" for the global fight against drug cheats.

British Olympic gold medal-winning cyclist Callum Skinner tweeted, "The biggest doping scandal in history goes unpunished," and Global Athlete, which advocates for sportspeople, called the ruling "farcical".

"The fact that Russian Athletes can compete as 'Neutral Athletes from Russia' is another farcical facade that makes a mockery of the system."

by AFP

Login to leave a comment

Lance Armstrong ran the Austin Marathon clocking 3:02:13 raising money for a program called Charity Chaser

Lance Armstrong ran the Austin Marathon last Sunday, finishing in 3:02:13. He was raising money through a program called the Charity Chaser. Armstrong started behind the pack and earned one dollar for every person he passed. He finish 58th overall, meaning that he managed to pass 2,594 people.

Armstrong ran his first marathon in 2006 in 2:59:36, but his running results were threatened once he was convicted of doping in 2012 and received a lifetime ban from cycling. Armstrong was stripped of seven Tour de France titles for violating anti-doping rules.

The former cyclist’s running results have stood, and in 2016 the USADA officially stated, “He can compete in a sanctioned event at a national or regional level in a sport other than cycling that does not qualify him…to compete in a national championship or international event.”

His personal best is 2:46:43 from the New York City Marathon.

Login to leave a comment

Austin Marathon Weekend

The premier running event in the City of Austin annually attracts runners from all 50 states and 20+ countries around the world. With a downtown finish and within proximity of many downtown hotels and restaurants, the Austin Marathon is the perfect running weekend destination. Come run the roads of The Live Music Capital of the World where there's live music...

more...Lance Armstrong will run the Austin Marathon for Charity

The Austin Marathon, which will take place on February 19th, 2019, has Lance Armstong on the start list. Armstrong will be a Charity Chaser, and hopes to raise over $1 million in support of the Austin community.

Armstong told race organizers, “I’m honored to be the Charity Chaser and help Austin Gives Miles surpass it’s $1 million goal,” said Armstrong. “My training for the Austin Marathon has begun and I’m ready to amplify the positive effects Austin Gives Miles and its official charities have on our community.”

During the 2018 Austin Marathon, Austin Gives Miles donated $670,000 to the Central Texas Community. The 2019 event will be the 28th running of the marathon. Lance Armstrong’s personal best is 2:46:43 clocked at the New York City Marathon.

Login to leave a comment