Running News Daily

Top Ten Stories of the Week

5/13/2023

These are the top ten stories based on views over the last week.

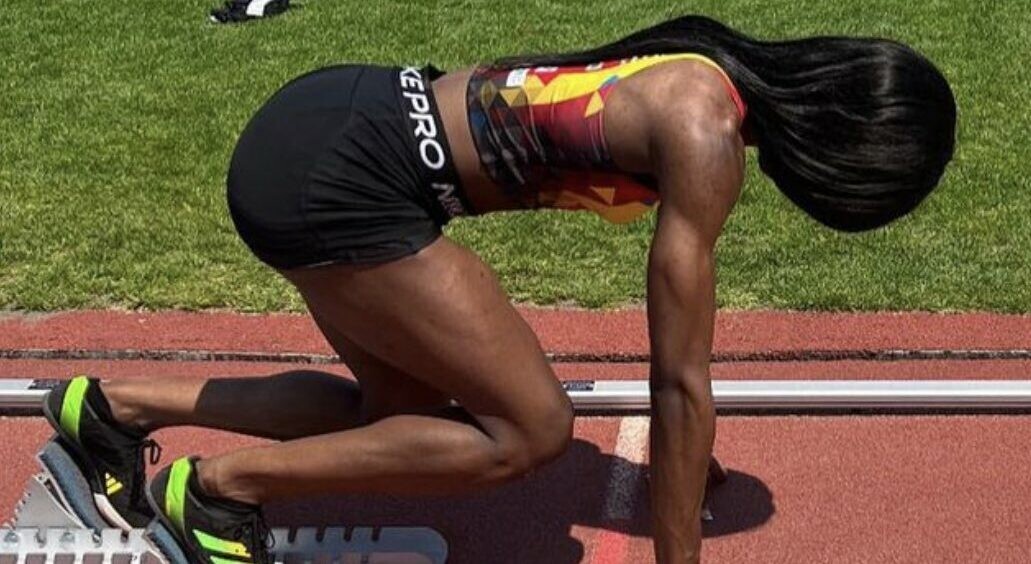

Trans athlete feels "hounded" by World Athletics after Paris 2024 dream ends

French sprinter Halba Diouf has spoken out saying she feels she is being marginalised and hounded out of sport after her dream of participating at the Paris 2024 Olympic Games ended when World Athletics banned transgender women from female competition.

The 21-year-old had been training to compete in the 200 metres event in her country's capital next year.

However, her hopes were dashed in March when the governing body ruled that transgender women who have gone through male puberty were not allowed to compete in women's events.

World Athletics took the decision citing a "need to protect the female category".

"I cannot understand this decision as transgender women have always been allowed to compete if their testosterone levels were below a certain threshold," Diouf told Reuters.

"The only safeguard transgender women have is their right to live as they wish and we are being refused that, we are being hounded - I feel marginalised because they are excluding me from competitions."

Senegalese-born Diouf arrived in France aged four before moving to Aix-en-Provence as an adult where she started hormone therapy to change sex.

Her gender transition was then recognised by French authorities in 2021.

Diouf's endocrinologist, Alain Berliner, said Diouf "is a woman, from a physiological, hormonal and legal point of view."

"Her testosterone levels are currently below those found on average in women who were born as women" he said, as reported by Reuters.

Until World Athletics introduced its new rules, transgender women and athletes with Differences in Sex Development (DSD) could take part in elite events between 400m and a mile if their testosterone levels were below five nanomoles per litre.

That was then cut by half to 2.5 nanomoles per litre and must be maintained for at least 24 months before DSD athletes can compete in female competitions.

(05/10/23) Views: 113Owen Lloyd

Interval workouts: what runners typically get wrong

Intervals are a key aspect of training for any race. From the 100m to the marathon, interval work can improve your fitness and results. But are you approaching interval training correctly? Potentially not–and it’s a very common mistake.

Steve Magness is the author of the book Do Hard Things: Why We Get Resilience Wrong and the Surprising Science of Real Toughness. He’s also a performance coach and a former miler. Magness writes that many runners (especially new runners) have the wrong idea when it comes to interval training. “What do they get wrong? They go too hard at the wrong time,” Magness writes, “resulting in meaningless fatigue, instead of purposeful and productive fatigue.”

What Magness describes is an issue of pacing. He says some runners start their workouts too quickly, resulting in maxing out their efforts too early.

For example, if your prescribed workout is 8x200m, a common pitfall would be to start at 32 seconds and only be able to finish running 42 seconds–in other words, you go backward. Magness says this results in a feeling of ‘dying’ during your workout. “Mechanics get sloppy, fatigue wins. Their final few intervals are a lesson in how to look miserable, and just try to survive.” You spend the whole workout just trying to get through it, which is a really difficult (and potentially discouraging) way to exercise.

How to do it properly

What Magness recommends instead is starting at a pace you can sustain (more or less) throughout the entire workout. It should feel consistently more difficult with every repetition–but never like you’re approaching full-body failure. “If you average roughly the same time all the way across, it’ll be intense enough, and challenging towards the end, so you can practice maintaining form and force output under heavy fatigue. You’re teaching good habits.”

Know the point of the workout

Another key aspect of interval training, which Magness highlights, is to know the purpose of your workout. For example, if you’re trying to build your anaerobic engine (so you can go hard when you need to), consider short, faster reps with longer rest. If you’re looking to improve your endurance, then longer, slower reps with shorter rest will do the trick.

(05/05/23) Views: 91Madeleine Kelly

How to Pace Yourself Like a Pro

The art of pacing has, sadly, become a lost art.

Gone are the times of heading out the door, running a 30 minute out-and-back and calling it four miles.

No more coming home and trying to explain to your wife how you ran a distorted cloverleaf through the subdivision.

Now you can upload your data and show her! Figuring out how to pace yourself running is no longer needed

What made running so simple, so pure of a sport, perceived effort versus the clock is just as much an afterthought as what life was like before cell phones.

Working with runners on a daily basis for almost a decade now, I have noticed a growing population of runners solely depending on GPS watches to keep a constant pace while running.

Rarely do I see workout feedback explaining how they felt going into a workout, how they felt as the workout progressed or how they felt post workout.

Feedback is wrapped up in hitting target paces, heart rate averages, and elevation gain.

Completing a workout is no more about how you feel inside, what we refer to as internal cues. Rather we focus so much on external feedback from data and devices that are readily at our fingertips.

How does this type of reliance affect our ability to gauge and adjust our pace as we move through our marathon training schedule?

I like to compare the dependence on GPS data to our vision.

If you want to experiment, stand on one foot, hands out to keep balance. Next, put hands by your sides and don’t allow them to move. Not a huge difference in the ability to keep balance.

Now, with arms remaining at your side, close your eyes.

How long were you able to remain on one foot?

Notice how much more dependent we are on our visual feedback than our proprioceptive feedback?

Same is true for most runners when you take away their GPS watch. Their ability to pace goes out the door because they can’t feel or decode what their internal cues are giving them.

So how do we regain that sense and sharpen it in training and carry it over to race day?

Pace Yourself Better In Training

Learn to pace by listening to your body.

You can’t become better at pacing until you know what you’re looking for.

Coach Jeff says, “The ability to properly adjust your effort as an experienced runner is critical when you’re pushing for that last one percent improvement to break through the plateau.”

It’s great to have that data that a GPS gives you but it should be in support of what your body is telling you.

You might be wondering:

What internal cues do I need to look for to learn how to pace myself better?

Perceived effort

On a scale of 1-10 how are you feeling.

Make notes of your effort level during different workouts in your training log. Over time you’ll begin to look back and see similarities.

Thresholds are consistently around 7-8. Easy runs are 4-6.

Learning to see a workout and automatically knowing the effort it will need before going into the workout is a huge advantage.

Breathing rate

Think about your breathing rate while running at different effort levels.

Typically the faster you run the more your breathing rate picks up. Very similar to the effort scale.

Think and feel how many steps you’re taking while you’re breathing in, while you’re breathing out.

Are you doing a workout that asks to switch paces drastically? How does your breathing change when the paces change? How does your breathing rate gradually pickup over the course of a tempo run?

Foot strike rhythm

Counting strides per minute is good for a number of reasons but it’s especially helpful with gauging different paces.

As we increase in speed, most of us increase in steps per minute as well. Sometimes faster paces or harder efforts means we can tell a difference in the sound our foot is making with the ground.

Both are great tools to learn and use as workouts progress, we fatigue, and when to adjust or gauge pace within a run or race.Learn to pace from workouts

Why not let the RunnersConnect customized coaching schedules do the hard work for you. We will give you a variety of paces within the training cycle to practice this with. In any given week you could run workouts that culminate in your running extended periods of time at 5-6 different paces.

One of my favorite workouts to learn how to connect a pace with an effort level is the cutdown run.

In a cutdown, or progression run, the goal is to get quicker as the run progresses. Typically you’re “going through the gears” hitting several different pace ranges that you commonly train or race at.

This type of a run forces you to focus on your ability to dial in a pace based on effort multiple times throughout the workout.

Cutdown’s are just one example, but any type of workout that asks you to vary pace often throughout a run is makes for a great opportunity to learn how to gauge pace and adjust effort accordingly.

Pace Yourself Better While Racing

Matt Fitzgerald has written, “The goal in racing is to cover the distance between the start and finish lines as quickly as possible given one’s talent and conditioning levels. To achieve this goal, a runner must have a solid sense of the fastest pace he or she can sustain through the full race distance and the ability to make appropriate adjustments to pace along the way based on how he or she feels.”

How to find your goal pace from your training

All too often we set time goals based on expectations, comparisons, or qualifiers.

Many times I’ve seen 5:00 marathoners setting a goal to BQ at 3:45 in 6 months.

Although a BQ is achievable with a long-term, consistent, training it more than likely is not achievable within half a year. We need to learn to dial in a realistic goal race pace based on recent training results.

When an athletes comes to me we do sit down and talk about goal setting. We line up a timeline of racing goals which are mostly based around time.

We revisit original goal and compare it to how training has progressed over the course of the previous few months. Then formulate a goal pace to target in the final 6-8 weeks of training leading up to race day.

When we begin to taper, typically anywhere from 7 days to 3 weeks depending on athletes, we reevaluate our goal time based solely on the previous 6-8 weeks not the time we originally set 5 months prior.

This is the best formula I’ve found to setup a realistic goal time and allows us to plan for the race.

Creating A Race Plan

Now that you have a pretty good idea of how to assess a goal pace for a race, the second step would be putting together a race plan.

You wouldn’t go into a workout consisting of mile repeats without a goal time range to hit nor should you toe the line of a race without a detailed race plan.

Now that you are equipped with a goal race pace based on past training outcome you also need to take these things into consideration:

Race course elevation gain and loss

You very well could be in sub 4-hour shape with many weeks of training that prove that fitness level but if the course profile has a lot of elevation gain or loss than you need to adjust race pace based on those circumstances.

A 3:55 marathon on a course with 3,000 feet of elevation gain over 26.2 miles takes a lot more fitness than a 3:55 at Berlin, or a relatively flat course.

Study the course map, break the race down into smaller sections to enable better focus, and adjust plan accordingly to ensure the fastest 26.2 miles.

Race day weather conditions

Take the same 3:55 example. Optimal marathon temperatures for most runners are in the 50’s, although research has found that every runner has an optimal race temperature.. A 3:55 will feel a lot easier at 55 degrees compared to 75 degrees.

The rule of thumb is for every 5 degrees over 60 you can estimate 1-3 minutes added to your marathon time. With that being said, weather is a major factor is setting up a race plan that you can execute with success.

Allow some flexibility on race day

Staying with the 3:55 example that is 8:58 per mile. As mentioned before, each mile is different therefore each mile in the marathon shouldn’t be 8:58 on the dot.

Trying to do so means constantly putting in mini surges, which is not ideal for any runner in a marathon.

This is a great example of learning to pace based on effort.

Following this guide will leave you with a race plan based on your recent training results, course profile and weather conditions, and you have a very specific idea of how to attack race day.

Now for the toughest part:

Your final step is putting it all together and executing accordingly without being influenced by hundreds of other runners. The number one mistake I continue to see in marathon racing is going out too hard in the first 6 miles.

The first 10k sets up the last 10k, good or bad. You have planned your work now it’s time to work the plan.

A sound race plan is only half the equation. The other half starts in training and unlocking the keys to better gauge and adjust pace based on what your body is telling you.

Next time out on an easy run spend time gauging effort by clicking off miles without looking at your watch but rather feeling, thinking, and listening to what your body is saying.

Before you glance at your GPS to confirm a mile split take a guess at what pace you are running and use your watch as a secondary means of feedback and confirmation.

Over time this still of knowing pace based on sensory data within will becomes fine-tuned and ultimately a better race predictor than what your watch is telling you.

(05/11/23) Views: 91Coach Danny

83-year-old Hopes to Run Olympic ‘Marathon for All’ in Paris

At age 83, Barbara Humbert dreams of taking part in next year's 'Marathon for All’ race at the Paris Olympic Games.

It is the first event of its kind, permitting amateur athletes to run the same race path as the Olympic marathon athletes.

Humbert has a history of success suggesting she could beat some runners half her age.

Not your usual great-grandmother, the German-born Frenchwoman runs 50 kilometers a week. She has competed in many marathons - and has the medals to show for it.

"It's extraordinary to have the Olympics in Paris," said Humbert at her home in Eaubonne. The town is one hour's drive north of Paris. "It would be a gift for my 60th marathon," she added. "For me it would be a crowning achievement."

However, Humbert is unsure if she will get to compete in the race because the number of runners is limited.

In marathons, runners often receive race bibs – a piece of paper with a number on it to identify the runner. Race bibs for the Marathon for All will be limited to 20,024, to be chosen in a random draw.

Humbert’s husband Jacques is her biggest supporter. He is helping where he can. He is waiting to hear from the sports ministry about the request to reserve a bib for his wife. The ministry was not immediately available for comment to the Reuters news agency.

Many medals hang in the entrance of Barbara and Jacques’ home.

They remind Barbara of all the races she has been part of, from Athens to Boston and many other cities. She estimates that she has run about 8,000 kilometers in those races.

More than 40 years after she first started racing, Humbert beat a world record in her group during the French athletics championships last year.

She ran 125 kilometers in 24 hours.

How did she do it? By training a lot, and being careful with her diet, she said.

Humbert wants others to follow in her footsteps. She said of running, "It gives you balance. You run, you empty your head, you feel so much better afterwards."

Barbara is not planning to stop anytime soon. "As long as my joints don't cry out in pain, I will keep running," she said.

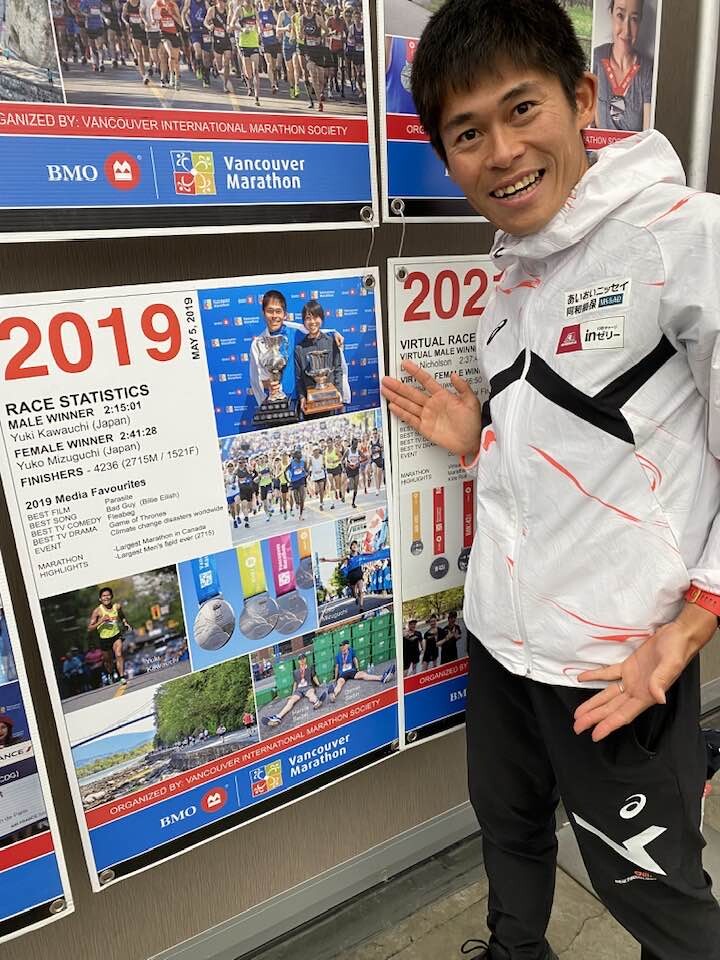

(05/06/23) Views: 83Yuki Kawauchi snags second BMO Vancouver Marathon victory

Japan’s Yuki Kawauchi claimed his second BMO Vancouver Marathon title on Sunday, finishing in 2:17:05–just over two minutes slower than his course-record-setting time of 2:15:01 in the 2019 marathon, and good enough to secure the 36-year-old a decisive victory against Toronto’s David Mutai (20:20:05) and Mississauga’s Sergio Raez Villanueva (2:23:21). Vancouver was just one of a number of marathons in Canada and Europe on Sunday.

With his latest victory, Kawauchi adds to an impressive list of accomplishments as a marathoner. The 2018 Boston Marathon champion was recognized by the Guinness World Records in 2021 for becoming the first person to run 100 sub-2:20 marathons.

Vancouver’s own Dayna Pidhoresky won the women’s marathon in 2:34:27, ahead of fellow Canadian Rozlyn Boutin (2:48:09) and U.S. marathoner Callahan McKenzie (2:49:28). Highlights of Pidhoresky’s running resume include winning the Canadian Olympic Trials Marathon in 2019 and being a four-time winner of the Around the Bay 30K race in Hamilton, Ont.

(05/08/23) Views: 79Paul Baswick

After 6-year-old ran Flying Pig last year, the marathon is changing age rules

After last year's Flying Pig Marathon, there was outrage from Olympic runners, hundreds of critical comments on social media and even a report sent to child protective services.

All of this happened because a 6-year-old ran and completed the full race. Some people believed this was far too young for a 26.2-mile run.

This year, the race has drastically expanded its policy concerning the age of racers. Last year, the policy simply stated that no one under 18 could participate in the marathon unless they got an exemption from the race organizers. How and why those exemptions were granted was not defined.

New age rules and requirements for the Flying Pig Marathon in 2023

The updated policy states:

Participants must be 18 years of age on race day to participate in the marathon, 14 years of age on race day to participate in the half-marathon, and 12 years of age on race day to participate in the 10K and the relay.

There is no age requirement for distances less than 10K.

Waivers for participation in the half-marathon and marathon distances will be considered for those 12 years and older on race day.

Waivers for participation in the 10K or relay will be considered for all ages.

This year, the waiver process has also been more clearly defined. Those who are younger than the age limit must:

Have parental approval.

Have approval from a primary care physician.

Allow Pig Works medical staff to discuss participation with primary care physician.

Meet in-person or via phone with Pig Works medical staff.

Have a guide to participate with them throughout the duration of the event and/or provide a personal emergency action plan for race day contacts.

All waivers were required to be submitted at least 30 days before the race and are subject to the discretion of Pig Works, the non-profit that organizes the Flying Pig and several other area races.

Following the 2022 race, Pig Works CEO Iris Simpson Bush took responsibility for allowing the 6-year-old son of Ben and Kami Crawford race. The Crawford family of Bellevue, Kentucky, has a large social media following and has published a book about hiking the Appalachian Trail together.

"This decision was not made lightly because the father was determined to do the race with his young child regardless. They had done it as bandits in prior years before we had any knowledge and we knew he was likely to do so again," Simpson Bush said.

A "bandit" is someone who runs a race without being properly registered.

The Crawfords defended their decision to let their son race. Ben Crawford said his son had begged to participate and they were prepared to let him stop at any time. They produced a documentary about it.

The Crawford family did not reply to emails or messages on social media asking about their plans for the Flying Pig this year.

In a statement this year, Simpson Bush said about 40,000 people are set to participate in the Flying Pig Marathon and its associated races.

“The Flying Pig Marathon was created to provide opportunities for people of all abilities. The safety and security of everyone on the course from participants, volunteers and spectators remains our top priority," she said. "With that in mind, we review our policies every year with our medical team and our board of directors to ensure they provide safety for our event.”

(05/05/23) Views: 77Cameron Knight

Kenya's track sensation Mary Moraa has her eyes firmly focused on a World Championship conquest in Budapest later in the year

Barely in her 20s, Kenya's track sensation Mary Moraa is already hogging the global limelight and stealing headlines at whim.

The 2022 Commonwealth Games 800 metres gold medallist has rocked premier global athletics shows in recent years to deservedly cut herself a niche in the Hall of Fame.

Fondly known as "The Kisii Express" by her dotting fans, Moraa has already claimed her space in the cutthroat world of athletics. Undoubtedly, the decorated track prodigy deserves every ounce of international acclamation.

Only recently, she set a new PB in April after storming to the 400m title at the Botswana Golden Grand Prix in an astonishing time of 50.44.

The sublime performance she pulled off in the blistering contest saw her smash her previous national record by 0.24 seconds, subsequently attaining the World Athletics Championships qualifying standards of 51.0 seconds.

"My previous 400m best was 50.67, which I attained at the Diamond League meeting in Brussels in September."

In Botswana, the two-lap specialists obliterated a stellar field that boasted Olympic and world finalist Candice McLeod of Jamaica, USA’s Kyra Jefferson, and the Botswana duo of Naledi Lopang and Thompang Basele.

She breezed to victory ahead of South Africa’s Miranda Coetzee and McLeod who crossed the line in 51.13s and 51.17s respectively.

She rallied from behind to take the lead with 30m to go on her way to the winner's podium at the National Stadium, Gaborone.

Moraa smashed the national record when she won the Kenyan trials for World Championships and Commonwealth Games in 50.84 on June 25, last year at the Moi Stadium, Kasarani.

Moraa, 23, has vowed to step into the big shoes of her role model Hellen Obiri, the middle and long-distance track sensation.

"I've always admired Obiri. I grew up watching her clinch titles and her amazing performances have inspired me a great deal. To an extent, there is a part of her that lives in me. I just want to be exactly like her," Moraa said.

"To date, Obiri still inspires me a great deal and I'm eager to emulate her success on the international stage," she added.

Indeed, Moraa has every reason to admire Obiri. She is the only woman to have won world titles in indoor track, outdoor track, and cross-country races.

Notably, Obiri is a two-time Olympic 5000 metres silver medallist from the 2016 Rio and 2020 Tokyo Olympics, where she also placed fourth over the 10,000 meters.

She is a two-time world champion, having claimed the 5000 m title both in 2017 and 2019 when she set a new championship record.

Obiri also tucked away a bronze in the 1500 metres during the 2013 World Championships and a silver in the 10,000 m in 2022.

She won the 3000 meters race at the 2012 World Indoor Championships, claimed silver in 2014, and placed fourth in 2018. She romped to the 2019 World Cross Country title and triumphed in the 2023 Boston Marathon.

Moraa said she and Obiri share a lot in common. Besides being compatriots, Moraa is elated they hail from the same county.

Coached by seasoned National Police athletics team gaffer Alex Sang, Moraa has her eyes firmly trained on a World Championship conquest in Budapest, Hungary later in the year.

She said she intends to run the 800m race at the World Championships in Budapest, Hungary in August, adding that she is determined to breast the tape in under two minutes.

Born on June 15, 2000, Moraa attended Nyangononi Primary School in Bassi Borabu, Kisii County where she sat for her Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE) in 2014.

Her potential in athletics came to the fore at Nyangononi when she ran away with several titles in the sprints and middle-distance races.

"I stamped authority in 100m, 200m, 400m, and 800m and even shattered the 400m East Africa school games record in 2014," Moraa proudly recounted.

Upon completing her studies, Moraa proceeded to Ibacho Secondary School in Kisii County but lasted there for only two years before transferring to Mogonga PAG Mixed secondary school where she sat for her Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE) in 2018.

"While at Ibachi, I experienced difficulties paying my school fees and it was the principal who would chip in most of the time. Unfortunately, he got transferred from the school and I was left stranded.

"I later joined Mogonga Mixed Secondary School, where I got a lot of support from the principal who also happened to be my coach."

An orphan from a disadvantaged background, Moraa got financial help from her school principal Aron Onchonga who paid all her school fees at Mogonga. Indeed, aside from affording her pertinent financial assistance, Onchong'a played a key role in honing her skills and carving her path to stardom. It was during her years in Mogonga that Moraa started jutting out her talons on the track.

"I am grateful to the school administration and the Principal for the moral and financial support they gave me while there."

During my years in Mogonga, I wanted to remain a role model to the young girls who shied away from sporting activities. I was determined to train and participate in various activities even after completing school," said Moraa.

(05/05/23) Views: 73Tony Mballa

Best Training Plan for Your First 5K

Want to run a faster 5K come race day? Start by breaking it down to two main components: your training plan and your race-day tactics.

Training Plan

First, take a look at your training plan. Try to add in or tweak a few workouts so they are 5K-specific, incorporate hills on a regular basis and add strength workouts. These will ensure that you are physically prepared for a 5K.

- Speedwork

To race faster, you must practice running faster. Start incorporating some faster running days (speed workouts) into your training plan. Speed workouts can range from short, fast surges of 20-30 seconds, to mile repeats, to 15-20 minute tempo runs.

- Hill Work

Hills are speedwork in disguise: They help strengthen your legs and build endurance that will come in handy as you are powering through your next race. A hill workout doesn't have to be fancy; it can be as simple as incorporating a hilly route in your everyday training runs. If you are looking to make it more formal, find a hill (anywhere from 200-400m in distance) with a 4 to 8 percent grade; sprint or run hard up the hill; and recover on the downhill (either walk or slowly jog). Repeat a few times, gradually building up the number of intervals over time.

- Strength work

Focusing on strength work a few times a week will not only make you stronger (which helps you run faster), but it can help prevent injuries by increasing the ability of your bones, ligaments, tendons and muscles to withstand the impact of running.

Race Day Tactics

You also want to take a look at the tactical side of racing a 5K. Aspects such as running the tangents better, proper pacing and strengthening your mind can make a huge difference in your 5K finish time.

- Run the tangents better

You can run your fastest 5K ever, but still end up with a slower time. How is that possible? Running even just .10 mile extra (3.2 instead of 3.1) could cost you 30-plus seconds extra on your official time. The better you run the tangents, the less mileage you will run and, therefore, the less time you will be running. Aim to cut the corners as closely as possible while looking for the shortest route in between the curves.

- Perfect Your Pacing

Even if you follow everything in this article, you can sabotage all of your hard work by starting too fast on race day. You trained for a certain pace; trust it. You will show up to the start line with freshly tapered legs, and the pace will feel easy when you start. Don't give in. Trust your training, stick to your goal pace and save energy for the last portion of the race.

- The Mental GameA 5K can hurt — there's no way around that — and you will find that your mind will want to quit long before your body does. As the race progresses, your lungs will be burning and lactic acid will be telling your legs to slow down. Thoughts of quitting or easing up the pace start to take over. Prepare yourself to quiet the negative thoughts when they begin to creep in during the last half of a 5K.

(05/06/23) Views: 73Michele Gonzalez

This Ultrarunner Is Living in a Glass Box for 15 Days

During the experiment, Krasse Gueorguiev will have only a bed and a treadmill

Krasse Gueorguiev, a Bulgarian ultramarathon runner, will spend 15 days in a glass box in a park in Sofia, Bulgaria, to raise money to help young people battling addiction.

Gueorguiev, a motivational speaker and charity ambassador, has run nearly 30 ultramarathons worldwide, from the Arctic to Cambodia, including the 135-mile Badwater Ultramarathon in Death Valley, California.

"I want to challenge myself," Gueorguiev told Reuters. "I want to show when you put someone in the box how psychologically they change."

Proceeds from the stunt will be used for several projects aimed at preventing addiction for children under 18, not just for drugs and alcohol—the runner also hopes to help teens avoid addiction to things like social media and energy drinks.

On Sunday, the runner was placed in a box with three glass walls on a pedestal in front of the National Palace of Culture in Sofia (Bulgaria's capital). During the experiment, Gueorguiev will have only a bed and a treadmill, with no access to books, a computer, or a phone. He will only be allowed to speak to members of the public for 30 minutes each day.

"This is not a physical experiment; it is a psychological experiment," he said.

If the stunt sounds familiar, you may remember magician David Blaine undertaking a similar experiment in 2003. The illusionist spent 44 days in a glass box suspended over the River Thames in London.

The stunt was met with much public outcry, though, unlike Gueorguiev, Blaine's time in the box was for entertainment purposes only. He endured drumming from the crowd in the evening hours and having eggs and other items hurled at his temporary home. The magician seemingly took it all in stride. "I have learned more in that box than I have learned in years. I have learned how strong we are as human beings," Blaine told reporters after emerging from the box. Upon completing the 44 days, Blaine was noticeably thinner, with depleted muscle mass and a thick beard.

Only time will tell if a similar fate inside the box will befall Gueorguiev.

This is also not the ultrarunner’s first attempt at performing a stunt in the name of goodwill. In 2019, Gueorguiev ran about 750 miles through Bulgaria, North Macedonia, and Albania to urge the governments to build better infrastructure, and in January of 2018, Krasse ran for 36 hours straight on a treadmill at a Sofia shopping mall.

(05/06/23) Views: 70Runner’s World

Hellen Obiri: Boston Marathon winner on family sacrifice and quitting the track

As Hellen Obiri crossed the finish line to win this year's Boston Marathon, a few metres ahead was her daughter, Tania.

The double world champion was soon locked in an embrace with both her husband, Tom, and Tania as the family celebrated the surprise win in what was only her second marathon.

Speaking to BBC Sport Africa, Obiri found it all hard to describe.

"That was one good moment for me, at the finish line seeing my daughter. I cannot even explain what I felt."

The rush of emotion, which left Obiri in tears, is understandable when placed in the context of her decision to uproot her family and move them from Kenya to the United States after she quit track running to target the marathon.

"When switching to the road, I felt I needed a coach on the ground with me in training," the 33-year-old explained.

"On track you can train without a coach present and do well, but with the marathon sometimes you need a coach to watch what you are doing."

The Obiris' new home is in the city of Boulder, Colorado. But her husband and daughter only arrived a few weeks before the race in Boston. For months before that Obiri had been on her own.

'Why am I here?'

Previously a 5000m specialist who claimed world titles over the distance in 2017 and 2019, the 2018 Commonwealth title and Olympic silver medals in 2016 and 2020, Obiri made her marathon debut in New York last November.

Two months prior she had moved to the US to join her coach, retired American athlete Dathan Ritzenhein.

At the time, it meant leaving Tania and Tom back in Kenya waiting on their visas.

"It was a challenge because you don't have a family in the US. Sometimes the time difference (for) calling is not good. Maybe when you call the child is sleeping," she said.

"The most important thing is the family understands what you are going there to do, because it's a short career. The family give me a lot of time, support and a lot of encouragement."

But the pain of separation sometimes led Obiri to question her decision.

"She (Tania) was always telling me 'Mommy, I want you to come now'. When she tells you, you feel like crying, you feel you don't have morale.

"Why am I here and my baby's crying there?"

Despite her best efforts to remain focussed, New York did not go as planned as poor race tactics saw her finish sixth on her marathon debut.

"I used to run from the front in track races. I thought even in a marathon I can run in front. That cost me a lot because in marathon you can't do all the work for 42 kilometres," she admitted.

"What I learned from New York is patience, just wait for the right time so you can make a move."

Obiri proved to be a fast learner. With her family now watching on, she won her second marathon, taking more than four minutes off her time in New York.

"When you have your family around you, that means you don't have stress.

"You don't need to think about anything else. You are thinking about your family and the race and when your family is there to watch you, they give you a lot of encouragement."

Rocking life in Boulder

With the family now settled in their Colorado home, Tom has enrolled as a student. But Obiri worries about how a seven-year-old Kenyan girl will adjust to life in a different country.

"The first week was terrible for her because she didn't have friends here, it's a new environment," she said, fretting as any mother would.

"(But) Tania is so friendly. So after one week and a half, she was coming and telling mum 'I have some friends, this one and this one...'"

Obiri also had concerns when it came to Tania enrolling in school.

"I was so worried. I wondered, how will the teachers treat her as she's from Africa?

"Maybe some schoolmates will think 'You are from Africa, we don't want to be your friends.'

"I used to ask after school, 'Who wasn't nice to you? Do they treat you well?' and she said 'No, I'm okay with my friends and my teachers'."

Olympic agenda

The 2019 world cross country champion says not all of her friends understood her decision to uproot her family, but Obiri blocks out the "negative talk" to focus on her athletic ambitions and is also now at peace with her family situation.

Her next big mission, away from the six World Marathon Majors - which are Boston, New York, Chicago, London, Berlin and Tokyo - is to try to complete her list of global titles, filling the one very obvious hole in her list of achievements.

"I will work hard to be in the Kenya (marathon) team for Paris 2024."

"I have won gold medals in World Championships so I'm looking for Olympic gold. It is the only medal missing in my career."

(05/08/23) Views: 70

Sports Africa