Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #ultrarunning

Today's Running News

Anne Flower Sets New Women’s 50-Mile World Record at the 2025 Tunnel Hill 50 Mile

In a stunning display of endurance and precision pacing, emergency-room physician and ultramarathon standout Anne Flower blazed to a new women’s world record of 5:18:57 for the 50-mile distance at the 2025 Tunnel Hill 50 Mile in Vienna, Illinois. The mark shatters the previous record of 5:31:56 held by Courtney Olsen, set on the same course last year.

Record-Setting Performance

Held on the flat, crushed-gravel rails-to-trails route of the Tunnel Hill State Trail, the race has become a proving ground for world-class performances. Flower averaged an extraordinary 6:23 per mile (3:57 per kilometer) across the full 80.47 km course, running even splits and showing no signs of strain even as temperatures climbed later in the race.l

From the opening miles, Flower stayed well ahead of record pace, never faltering and closing strongly to seal a performance that redefines the women’s 50-mile standard. Olsen, competing in the 100k event this year, passed the 50-mile mark in 5:33:59—still an elite split, but more than 15 minutes behind Flower’s record pace.

From Marathons to Ultramarathons

Based in Colorado Springs, Colorado, Flower balances her demanding career as an emergency-room doctor with elite-level training. Before moving to the trails in 2019, she competed in marathons and took part in the 2020 U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials. Her road background shows in her efficient stride and disciplined pacing.

Over the past two seasons, she has built an impressive résumé:

Winner of the 2024 Javelina 100k

Champion of the 2025 Silver Rush 50 Mile

Record-breaker at the 2025 Leadville 100 Mile, where she eclipsed Ann Trason’s 31-year-old mark in her debut at the distance

These results paved the way for her dominant performance at Tunnel Hill, demonstrating both her endurance and her remarkable consistency.

Raising the Bar for Women’s Ultrarunning

Flower’s 5:18:57 isn’t just fast—it’s a historic leap forward. Taking more than 12 minutes off a world record at this level is rare, and doing so with such control underscores her potential for even greater achievements ahead.

Tunnel Hill has become synonymous with world-record performances, and Flower’s run further cements the race’s reputation as one of the premier venues for ultradistance excellence.

What’s Next

With records now at both 50 and 100 miles, Flower’s next challenge may be defending or lowering her new mark—or shifting her focus toward international championship events. Whatever path she chooses, her rise through the sport has been nothing short of extraordinary.

Anne Flower has proven that it’s possible to balance a demanding professional life with world-class athletic performance. Her blend of discipline, determination, and pure endurance has elevated her into the top tier of ultrarunning’s global elite.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Did You Know? No One Has Come Close to Sorokin’s 24-Hour Record Since 2022

Did you know that Aleksandr Sorokin’s legendary 24-hour world record—set in 2022—is still untouched, and no one has even come particularly close?

At the 2022 IAU 24-Hour European Championships in Verona, Italy, Lithuanian ultrarunner Aleksandr Sorokin ran a staggering 198.598 miles (319.614 kilometers) in a single day. That’s the equivalent of running from New York City to Washington, D.C.—and then some—all in just 24 hours.

Even more impressive: Sorokin averaged a 7:15-per-mile (4:30/km) pace the entire time. That’s a tempo most runners struggle to hold for a 10K—let alone for nearly 200 miles.

What’s Happened Since?

At the 2023 IAU 24-Hour World Championships, Sorokin competed again and covered 301.790 kilometers—an outstanding performance, but still nearly 18 kilometers short of his own world record.

No other male athlete has even broken the 300 km barrier since.

Meanwhile, on the women’s side, Japan’s Miho Nakata set a new world record in 2023, covering 270.363 km, which is phenomenal—but still nearly 50 km less than Sorokin’s historic run.

Top 24-Hour Running Performances (All-Time)

|

Runner |

Gender |

Year |

Distance (km) |

Gap to Sorokin (km) |

|

Aleksandr Sorokin |

Male |

2022 |

319.614 |

0.00 |

|

Yiannis Kouros |

Male |

1997 |

303.506 |

16.11 |

|

Aleksandr Sorokin |

Male |

2023 |

301.790 |

17.82 |

|

Tamas Bodis |

Male |

2023 |

295.290 |

24.32 |

|

Haruki Okayama |

Male |

2023 |

289.420 |

30.19 |

|

John Stocker |

Male |

2021 |

285.300 |

34.31 |

|

Miho Nakata |

Female |

2023 |

270.363 |

49.25 |

|

Camille Herron |

Female |

2019 |

270.116 |

49.50 |

|

Patrycja Bereznowska |

Female |

2022 |

263.660 |

55.95 |

The Legacy

More than two years later, Sorokin’s record remains the gold standard in ultrarunning. His 2022 performance wasn’t just a world record—it redefined what humans can do in a single day.

Whether you’re a weekend warrior or an elite endurance athlete, one thing is clear: nobody’s chasing Sorokin. He’s still out in front—by miles.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Ludo Pommeret and Katie Schide Dominate a Gritty 2025 Hardrock 100

The 2025 Hardrock 100 delivered everything the ultra-trail world expects from one of the sport’s most iconic races—grit, altitude, heartbreak, and triumph. At the heart of it all, France’s Ludovic “Ludo” Pommeret successfully defended his title, while American ultra star Katie Schide shattered the women’s course record.

Pommeret Goes Back-to-Back

For the second year in a row, the 49-year-old Pommeret conquered the brutal 102.5-mile loop through Colorado’s San Juan Mountains, finishing in 22:21:55—the fifth-fastest time in race history. Battling thin air, smoky conditions from nearby wildfires, and rugged terrain with over 33,000 feet of elevation gain, Pommeret executed a masterclass in pacing.

Starting conservatively on the climbs, he surged on the descents, aided by elite pacers Jim Walmsleyand Vincent Bouillard. By dawn, he had extended his lead and cruised into Silverton well under the 48-hour cutoff, earning another coveted kiss of the Hardrock finish-line rock.

The men’s podium was a French sweep: Mathieu Blanchard placed second in 23:44, followed by Germain Grangier in 24:04.

“I was worried about the smoke early on,” Pommeret said afterward, “but the final miles were magic. I even walked the last climb to take it all in.”

Schide Smashes Course Record

In the women’s race, Katie Schide delivered one of the most commanding performances in Hardrock history, crossing the finish in 25:50—the fastest counterclockwise time ever on this course. Her effort redefined what’s possible on one of the toughest 100-milers in the world, solidifying her place among the sport’s elite.

A Somber Note

The celebration was tempered by tragedy. One of the 146 starters, 60-year-old Elaine Stypula, passed away early in the race. The trail community paused to honor her memory, a reminder of both the beauty and the inherent risk of this extreme pursuit.

Why This Race Matters

• Age is just a number: At nearly 50, Pommeret continues to perform at the highest level, adding another major title to a résumé that includes victories at UTMB (2016) and Diagonale des Fous (2021).

• Trail’s toughest test: With extreme elevation, altitude averaging over 11,000 feet, and no room for error, Hardrock remains a crucible for the toughest athletes on Earth.

• Global competition: With a French men’s podium and an American record-breaker, the international caliber of this year’s race underscored its global significance.

2025 Hardrock 100 Key Results

|

Category |

Winner |

Time |

|

Men’s Champion |

Ludovic Pommeret |

22:21:55 |

|

Women’s Champion |

Katie Schide |

25:50 (course record) |

|

Men’s 2nd |

Mathieu Blanchard |

23:44 |

|

Men’s 3rd |

Germain Grangier |

24:04 |

|

|

|

|

With record-breaking performances and powerful moments of perseverance, the 2025 Hardrock 100 once again proved why it’s one of the most respected races in the world of ultrarunning.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Hardrock 100

100-mile run with 33,050 feet of climb and 33,050 feet of descent for a total elevation change of 66,100 feet with an average elevation of 11,186 feet - low point 7,680 feet (Ouray) and high point 14,048 feet (Handies Peak). The run starts and ends in Silverton, Colorado and travels through the towns of Telluride, Ouray, and the ghost town...

more...Abby Hall Claims Fairytale Victory at 2025 Western States 100 After Golden Ticket Surprise

In a race defined by resilience, heat, and high drama, Abby Hall delivered one of the most emotional and triumphant performances in Western States Endurance Run history, winning the women’s race at the 52nd edition of the world’s oldest and most iconic 100-mile trail event.

Hall, who just months ago wasn’t even on the start list, crossed the finish line at Placer High School in 16 hours, 37 minutes, and 16 seconds, recording the fourth-fastest women’s time in race history. Her victory marks a stunning return to form after years of injury setbacks and a last-minute Golden Ticket entry.

A Storybook Build-Up to the Start Line

Hall’s journey to Western States was anything but straightforward. After a lengthy recovery from a serious knee injury, the American ultrarunner returned to form with a win at Ultra-Trail Kosciuszko by UTMB in December 2024. But a Golden Ticket to Western States proved elusive.

She finished fifth at the Black Canyon Ultras, narrowly missing an automatic entry. However, fate intervened when a pregnancy deferral by fellow runner Emily Sullivan caused the Golden Ticket to roll down—giving Hall an unexpected but welcome shot at redemption.

“It was such a beautiful passing of the baton,” Hall shared on Instagram. “I’m so inspired watching an incredible athlete like Emkay enter this new season of her life as she becomes a mother.”

How the Race Unfolded

Hall made her intentions clear early, leading through the Escarpment checkpoint at mile 4. Although she was briefly overtaken, she reclaimed the lead shortly after mile 60 and never looked back.

Facing fierce competition from Fuzhao Xiang (CHN)—who finished second last year—Hall maintained a steady and commanding pace through the canyon heat, where temperatures reached 104°F (40°C). With 10 miles to go, she held a 10-minute lead over Xiang, and that gap remained virtually unchanged to the finish.

Xiang once again finished runner-up, clocking 16:47:09, while Marianne Hogan (CAN) surged late in the race to secure third in 16:50:58, overtaking Ida Nilsson (SWE) in the final miles. Fiona Pascall (GBR) rounded out the top five.

2025 Western States 100 – Women’s Results

June 28, 2025 | 100.2 miles

1. Abby Hall (USA) – 16:37:16

2. Fuzhao Xiang (CHN) – 16:47:09

3. Marianne Hogan (CAN) – 16:50:58

4. Ida Nilsson (SWE) – 17:00:48

5. Fiona Pascall (GBR) – 17:21:52

Hall also placed 11th overall, finishing just behind many top men’s competitors in one of the deepest fields in race history.

A Career-Defining Moment

This was Hall’s second appearance at Western States—her first came in 2021, when she finished 14th. Her return this year wasn’t just about redemption; it was a masterclass in determination, patience, and execution.

“It’s surreal,” Hall said at the finish. “This race has meant so much to me for so long. To be back here, to be healthy, and to be crossing that line first—it’s everything.”

The Global Rise of Women’s Ultrarunning

With five nations represented in the top five, the 2025 women’s race showcased the global depth and diversity of talent in ultrarunning. From Xiang’s technical brilliance to Hogan’s consistency and Nilsson’s enduring grit, this was a race that highlighted how far the women’s field has come—and how fast it continues to get.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Caleb Olson Stuns the Field with Breakthrough Win at the 2025 Western States 100

American ultra-trail runner Caleb Olson delivered a career-defining performance at the 2025 Western States Endurance Run, emerging as the surprise champion in what was billed as one of the most competitive editions in the race’s 52-year history.

The 29-year-old from Salt Lake City conquered the infamous 100-mile (161-kilometer) course through Northern California’s rugged Sierra Nevada mountains, finishing in 14 hours, 11 minutes, and 25 seconds—just two minutes shy of Jim Walmsley’s legendary course record set in 2019 (14:09:28). Olson’s time is now the second-fastest ever recorded at Western States.

His win comes just a year after a strong fifth-place finish in 2024 and cements his place among the top ranks of global ultrarunning.

A Battle of Heat, Elevation, and Grit

The race began at 5:00 a.m. in Olympic Valley, with runners quickly climbing to the course’s highest point—2,600 meters (8,600 feet)—before descending into the heat-scorched canyons. Snowfields in the early miles gave way to punishing heat, as temperatures soared to 104°F (40°C) in exposed sections of the trail.

Despite the brutal conditions, approximately 15 elite athletes crested the high point together, setting the stage for a tactical and attritional race. Olson surged to the front midway, clocking an average pace near 12 kilometers per hour and never relinquished his lead.

Elite Field Delivers Drama

Close behind Olson was Chris Myers, who battled stride-for-stride with the eventual winner for much of the race before taking second in 14:17:39. It was a breakthrough performance for Myers, who has been steadily climbing the ultra ranks.

Spanish trail running legend Kilian Jornet, 37, finished third, matching his 2010 result. Returning to Western States for the first time since his win 14 years ago, Jornet hoped to test himself against a new generation on the sport’s fastest trails. Though renowned for his resilience in mountainous terrain, he struggled to match the frontrunners during the course’s hottest sections.

“Western States always finds your limit,” Jornet said post-race. “Today, that limit came earlier than I’d hoped.”

Rising Stars and Withdrawals

Among the elite field was David Roche, one of America’s most promising young ultrarunners, who was forced to withdraw after visibly struggling at the Foresthill aid station (mile 62). Roche had entered the race unbeaten in 100-mile events.

“I’ve never seen him in that kind of state,” said his father, Michael Roche, who was on hand to support him. “This race just takes everything out of you.”

Roche’s exit was a reminder that, even with perfect preparation, the Western States 100 is as much about survival as speed.

The Lottery of Dreams

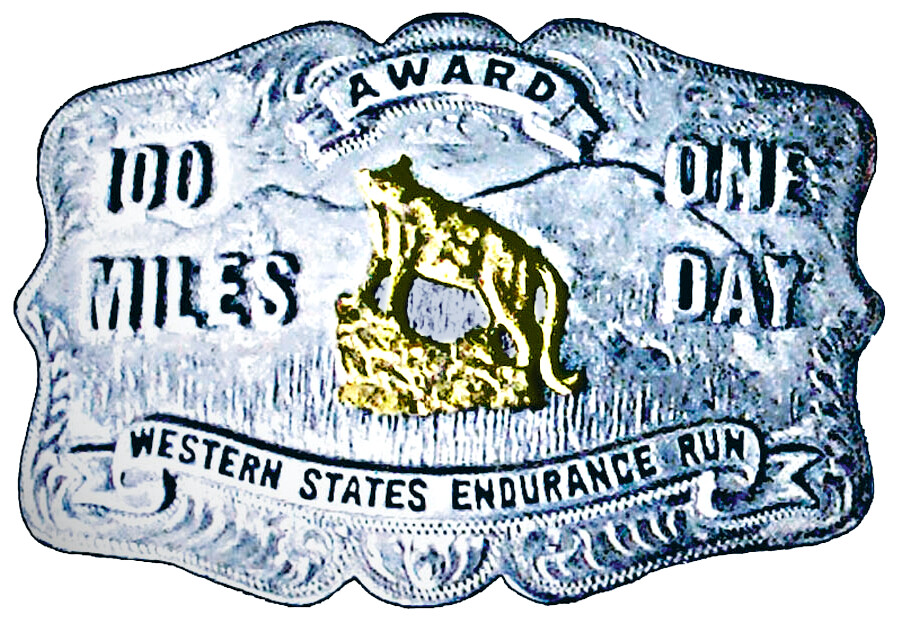

Held annually since 1974, the Western States Endurance Run is more than a race—it’s a pilgrimage. With only 369 slots available, most runners enter via a lottery system with odds of just 0.04% for first-timers. Elite athletes can bypass the lottery by earning one of the coveted 30 Golden Ticketsawarded at select qualifying races each year.

For many, getting to the start line takes years of qualifying and persistence—making finishing the race an achievement in itself.

Olson’s Star Ascends

Before this landmark win, Caleb Olson was already on the radar of the ultra community. He had logged top-20 finishes at the “CCC”—a 100-kilometer race associated with the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc series—and had demonstrated consistency in major trail events.

Saturday’s victory vaults him into the upper echelon of global ultrarunners and marks a generational shift in the sport.

“I’ve dreamed of this moment,” Olson said at the finish. “Today, everything came together—the training, the heat management, and the belief. This is why we run.”

2025 Western States results

Men

Saturday June 28, 2025 – 100.2 miles

Caleb Olson (USA) – 14:11:25

Chris Myers (USA) – 14:17:39

Kilian Jornet (SPA) – 14:19:22

Jeff Mogavero (USA) – 14:30:11

Dan Jones (NZL) – 14:36:17

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Western States 100

The Western States ® 100-Mile Endurance Run is the world’s oldest and most prestigious 100-mile trail race. Starting in Squaw Valley, California near the site of the 1960 Winter Olympics and ending 100.2 miles later in Auburn, California, Western States, in the decades since its inception in 1974, has come to represent one of the ultimate endurance tests in the...

more...Western States 100 Gears Up for an Epic Showdown Across Sierra Trails

The legendary Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run returns June 28–29, 2025, promising one of the most competitive and compelling editions in its storied history. Known as the world’s oldest 100-mile trail race, this ultra begins in Olympic Valley (formerly Squaw Valley) and finishes 100 rugged miles later at Placer High School in Auburn, California.

With more than 18,000 feet of climbing and 23,000 feet of descent, the race tests every aspect of a runner’s will and endurance. From snow-capped ridges to sweltering canyon floors, the course traverses remote backcountry, river crossings, and punishing climbs—all under the clock, with the coveted silver belt buckle awaiting those who finish under 24 hours.

Who’s Racing?

This year’s field is packed with elite talent, resilient veterans, and powerful storylines.

Top Men’s Contenders:

• Rod Farvard (USA) – One of the fastest Golden Ticket winners this season.

• Dan Jones (New Zealand) – Former Olympic Trials marathoner.

• Caleb Olson (USA) – Rising talent on the ultra scene.

• Chris Myers (USA) – Strong performances across the trail circuit.

• Jia-Sheng Shen (China) – Brings international prestige to the field.

Leading Women:

• Emily Hawgood (Zimbabwe) – Regular top-10 finisher with unfinished business.

• Eszter Csillag (Hungary) – One of Europe’s most consistent mountain runners.

• Heather Jackson (USA) – Former pro triathlete turned ultra star, back after a win at Unbound Gravel XL.

• Fu-Zhao Xiang (China) – Dominant at multiple global ultras.

• Ida Nilsson (Sweden) – Former European mountain running champion.

Notable Golden Ticket Winners:

• Riley Brady, Hannah Allgood, Rosanna Buchauer, Hậu Hà, Tara Dower, Abby Hall, Lin Chen, Caitlan Fielder, Nancy Jiang, Fiona Pascall, Johanna Antila

A Field That Crosses Generations

One of the most heartwarming developments this year is the record-setting six athletes aged 70 or older toeing the line.

Among them is Jim Howard, a two-time Western States champion (1981, 1983), who is making an inspiring return at age 70—running with two artificial knees. “I want to go out there one more time and be part of this incredible race,” Howard told Canadian Running.

Also returning is Jamil Coury, founder of Aravaipa Running, looking to build on his strong performance 15 years ago.

The Course

• Start: Olympic Valley (elevation: ~6,200 ft)

• Highest Point: Emigrant Pass (~8,750 ft)

• Finish: Auburn (elevation: ~1,200 ft)

• Snow is often a factor in the early miles, with extreme heat common in the canyons. Aid stations are spaced roughly every 4–8 miles, supported by over 1,500 volunteers.

Runners cross rivers, climb ridgelines, descend technical single-track, and are cheered into the stadium at Placer High—often in the dead of night.

Media and Spectator Access

• Live coverage, tracking, and video will be available on the Western States Endurance Run website.

• Key aid stations will allow crew and spectators, including Foresthill (mile 62) and Robie Point (mile 99).

A Race Like No Other

• One of the five races in the Grand Slam of Ultrarunning

• A UTMB World Series qualifier

• Historic, grassroots feel with world-class competition

Whether you’re cheering for a podium contender, an age-defying legend, or simply following the passion of runners determined to finish within 30 hours, this year’s Western States 100 is poised to deliver drama, beauty, and inspiration.

Let the countdown begin.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Western States 100

The Western States ® 100-Mile Endurance Run is the world’s oldest and most prestigious 100-mile trail race. Starting in Squaw Valley, California near the site of the 1960 Winter Olympics and ending 100.2 miles later in Auburn, California, Western States, in the decades since its inception in 1974, has come to represent one of the ultimate endurance tests in the...

more...Why Dill Pickles and Pickle Juice Are a Secret Weapon for Runners

When ultrarunning star Camille Herron clinched victory at the Ice Age Trail 50 earlier this May, she credited an unlikely trio for her late-race revival: an ice pitcher, a cold beer—and pickle juice.

Around mile 40 of the 50-mile race, heat and humidity hit hard, forcing Herron to take a break. But with a sodium boost from pickle juice, she was back on her feet and flying to the win. “I needed more sodium, so I learned a new trick with the pickle juice. I got going again and felt much better,” she shared on social media.

Herron isn’t alone. Many endurance runners are discovering the benefits of dill pickles and their salty brine. But why does it work?

What Makes Pickle Juice Effective?

1. Sodium Replenishment

When you sweat, your body loses vital electrolytes—especially sodium. Pickle juice is packed with it. One shot can contain up to 500–1000 mg of sodium, helping to restore electrolyte balance quickly.

2. Cramp Relief

Multiple studies suggest that pickle juice can stop cramps within minutes. The theory is that the acidic and salty solution triggers a reflex in the mouth and throat that interrupts cramping signals from the nervous system. It’s not just hydration—it’s neuromuscular magic.

3. Quick Absorption

Unlike sugary sports drinks, pickle juice doesn’t require digestion to be effective. It’s absorbed almost immediately, delivering rapid results during a race.

4. Gut-Friendly for Some

While not for everyone, many runners find that pickle juice is easier on their stomach than processed gels or sweet drinks during ultra events.

Why Dill Pickles?

It’s not just the juice—eating actual dill pickles provides a crunch of salt and hydration in solid form. The vinegar in dill pickles may also aid in reducing blood sugar spikes and promoting a steady energy level, especially in the latter stages of a long race.

Pickles in Daily Practice

Lifetime runner Bob Anderson, founder of My Best Runs, discovered dill pickles and pickle juice several years ago—and never looked back. “I love the taste and it just seems to work in so many different ways,” says Anderson, who eats and drinks from a big jar almost every day.

Pickles have become a staple at aid stations in trail and ultra races. From pickle popsicles to pickleback shots (yes, even paired with beer), the humble cucumber in brine has earned its place in the runner’s toolkit.

As Camille Herron proved, even champions lean on the classics. Whether you’re training for your first ultra or just need a leg up during your next 10K, a little pickle power might be exactly what you need.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

I am a pickle and pickle juice nut. Really helps keep me running I think. - Bob Anderson 5/23 3:56 pm |

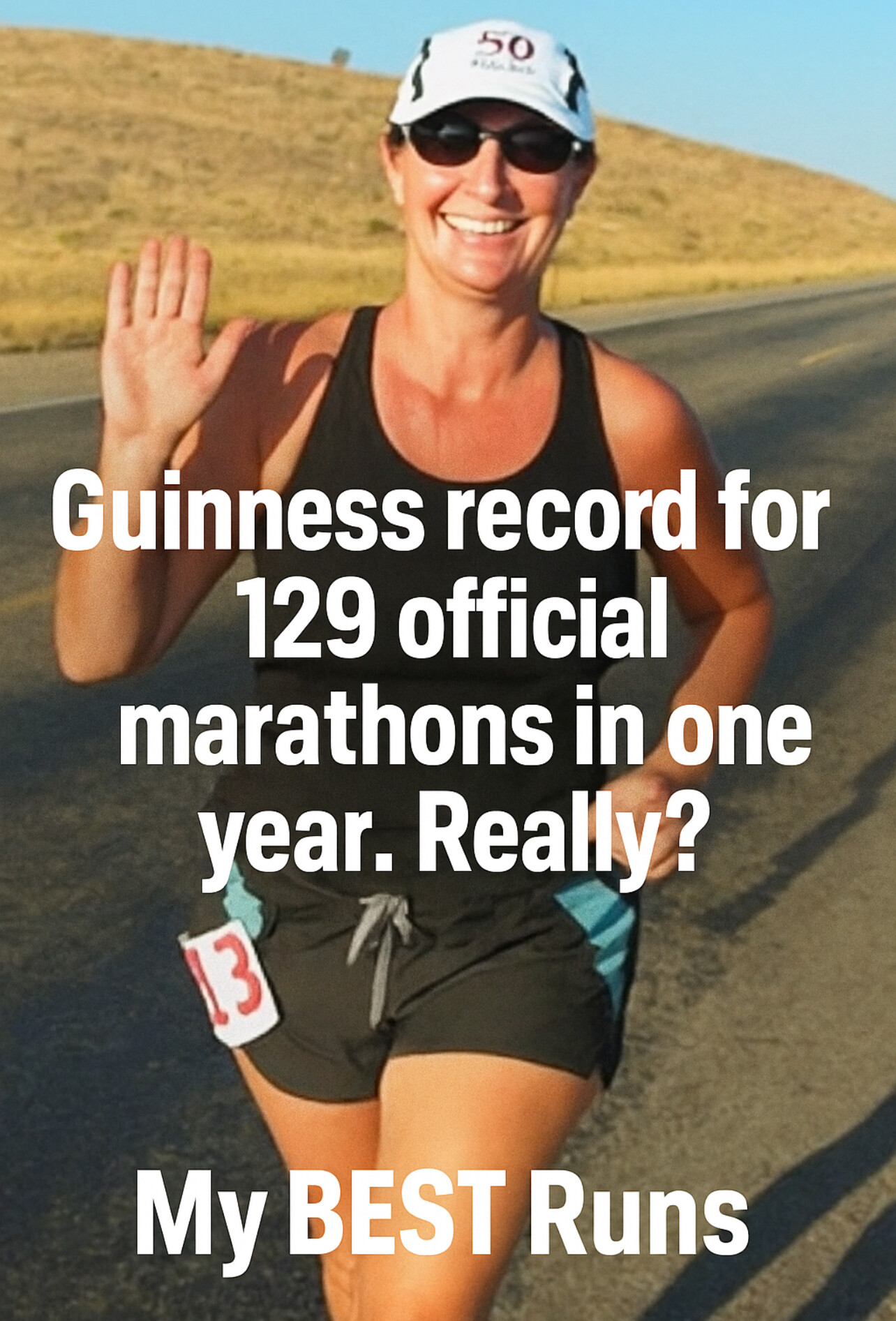

Angela Tortorice’s 1,000 Marathons and a Guinness Record — But Do the Numbers Add Up?

Angela Tortorice, a Dallas-based runner and full-time accountant, has received widespread praise on social media and in the running community for her astonishing endurance achievements. According to Guinness World Records, she holds the title for the most race marathons run in a single year by a woman: an incredible 129 marathons completed between September 1, 2012, and August 31, 2013. Nearly a decade later, she was celebrated again for completing her 1,000th marathon at the Irving Marathon in Texas on April 2, 2022, reportedly making her the first American woman to reach that milestone.

These accomplishments are inspiring — but they also raise serious questions.

The Math Behind the Record

Completing 129 marathons in 365 days averages to one marathon every 2.8 days. Since most official marathons take place on Saturday or Sunday mornings, a runner could theoretically participate in two marathons per weekend — totaling 104 races per year if no weekends were lookmissed. To reach 129 official marathons, one would need to find an additional 25 races held on weekdays, which is highly unlikely, especially in the U.S. where weekday marathons are rare.

Moreover, Angela reportedly maintained a full-time accounting job throughout this year, making the travel, recovery, and logistics of such a schedule even more challenging.

So how was this record verified?

Guinness Confirmation Process

According to Guinness World Records, all record attempts must be supported with documentation, including:

• Official race results

• Event certifications

• Witness statements

• Media coverage

While Guinness confirmed Tortorice’s record, the details of how each marathon was documented and what criteria defined a “race marathon” have not been made public. Many in the running community are left to wonder: Were all 129 races USATF- or IAAF-certified events? Or did some involve multi-loop courses, self-organized races, or training runs that happened to reach 26.2 miles?

If the latter, should they count toward an “official” marathon record?

The 1,000 Marathon Milestone

Tortorice ran her first marathon in November 1997 at the San Antonio Marathon. Reaching 1,000 marathons by April 2022 spans approximately 24.4 years. To accomplish this, she would have had to average more than 41 marathons per year for nearly two and a half decades — while working full time and recovering from each race.

Even with her 129-marathon year included, the pace remains difficult to reconcile with the typical calendar of official events. A search on marathonview.net, a site that tracks certified marathon results, lists only 313 races under her name — far short of 1,000. That gap again raises concerns about how these totals are being calculated and what types of events are being counted.

Ultrarunning Records Raise More Questions

Further complicating the narrative is data from UltraRunning Magazine, which tracks ultramarathon performances across the U.S. According to their published records, Tortorice competed in:

• 6 ultramarathons in 2012, totaling 182 miles

• 5 ultramarathons in 2013, totaling 152 miles

These included timed events like Run Like the Wind (26.7 miles in 6 hours) and longer efforts such as the Sunmart Texas Trails 50K and the Nashville Ultra. Running multiple ultramarathons during the same period she allegedly completed 129 marathons suggests an even greater load on the body — further straining plausibility.

To perform at this level, she would have needed to recover within 24–48 hours, every single week, for a full year, without serious injury. That level of resilience is virtually unheard of in the sport.

A Matter of Integrity

This story began as a celebration of one woman’s determination and consistency. Angela Tortorice clearly has passion and commitment to the sport, and there’s no question she’s run more marathons than most runners will ever attempt.

But when numbers like “129 official marathons in one year” or “1,000 official marathons in a career” are published and shared without full transparency, it matters. The integrity of marathon records — and the accomplishments of every runner who pushes through 26.2 miles — depends on clear, consistent standards.

If some of these marathons were self-supported runs or informal events, they are still worthy efforts — but should be categorized appropriately.

800 Marathons by 2019 — Then 200 More in 30 Months?

Another milestone adds complexity to the story. On October 5, 2019, Angela Tortorice celebrated her 800th marathon, as shown in a Facebook post and commemorative photo holding a cake at the finish line. That celebration is just 2 years and 6 months before her 1,000th marathon, reportedly completed at the Irving Marathon on April 2, 2022.

That means she would have completed 200 marathons in just 30 months, averaging over 6.5 marathons per month, or about 1.5 per week, every single week — during the height of the pandemic era when many events were canceled or limited.

Even more striking, race result records from this period show that she was also participating in ultramarathons, including at least one 24-hour race, according to UltraRunning Magazine. These events demand far more recovery than standard marathons. Yet her pace of marathons never seems to slow down.

The Core Question Remains

Angela Tortorice has no doubt logged thousands of miles and displayed a deep love for running. But the record of 129 marathons in a single year, verified by Guinness, was widely interpreted as representing 129 official, certified marathons — the kind that appear in race databases, are publicly timed, and meet governing body standards.

The mounting evidence — including her ultrarunning participation, the 800-to-1000 marathon timeline, and her full-time employment — raises a fundamental question: Were all of these “marathons” part of certified, organized events, or were many informal, self-organized, or private runs?

For a record with such significance, the running world deserves clarity. Not to diminish the accomplishment — but to ensure accuracy and integrity in what we celebrate.

Angela Tortorice has no doubt achieved extraordinary things. But the marathon world deserves clarity: What exactly counts as a marathon in these records? If the claim is that all 1,000 were “official race marathons,” then we must ask — where’s the list?

Until those questions are answered, the celebration must also come with scrutiny. The running community deserves both inspiration and truth.

by Bob Anderson and Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

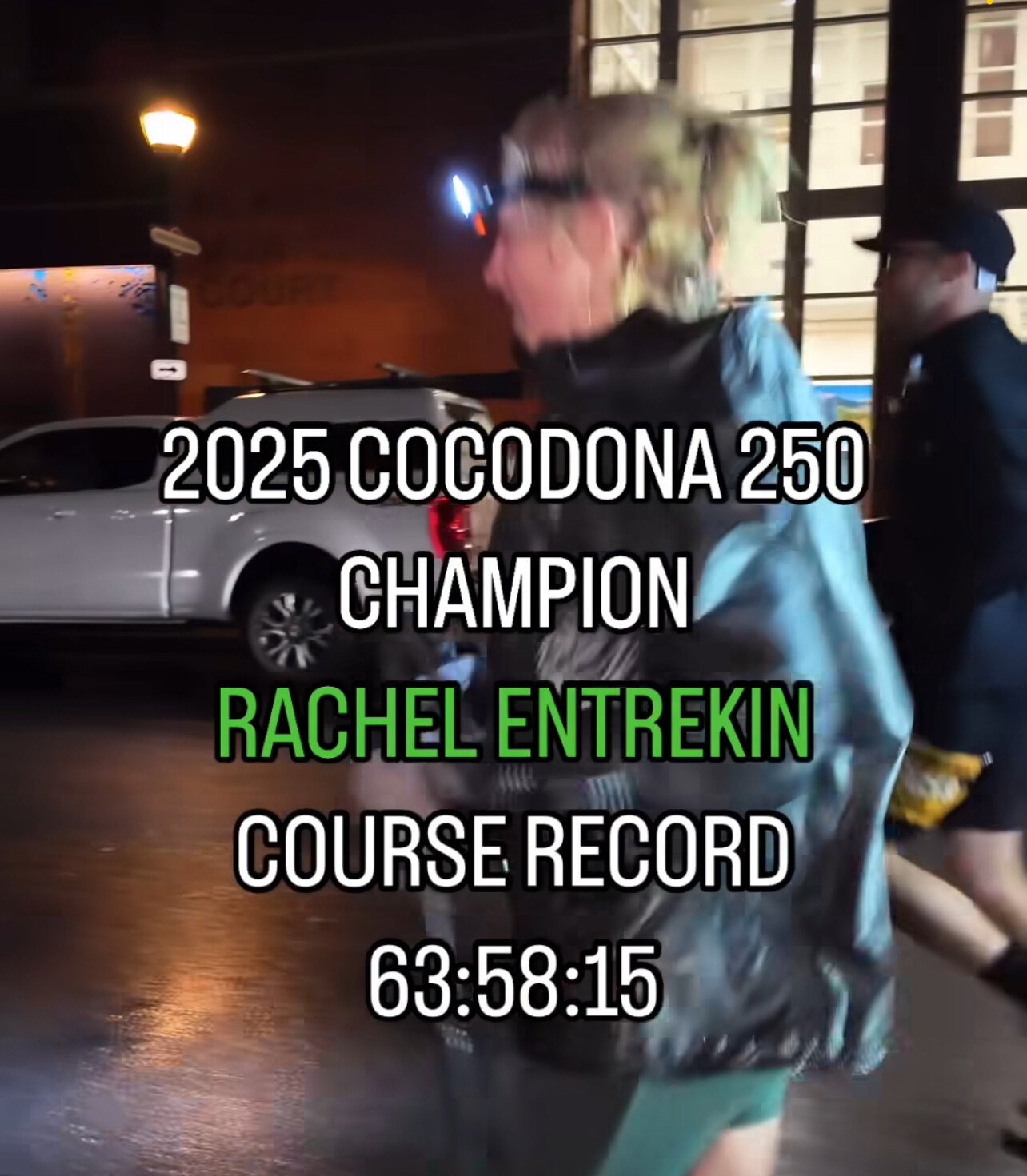

Arizona’s Monster — Why the Cocodona 250 Is One of the Toughest Races on Earth

The Cocodona 250 isn’t just a race—it’s an odyssey through Arizona’s most rugged and awe-inspiring landscapes. Spanning 256.5 miles from Black Canyon City to Flagstaff, this ultramarathon demands everything a runner has—physically, mentally, and emotionally.

With over 40,000 feet of elevation gain, participants climb mountain passes, descend desert valleys, and navigate technical trails through towns rich in mining and frontier history—Crown King, Prescott, Jerome, Clarkdale, and Sedona—before reaching the final climb to Mount Elden and the finish in Flagstaff.

The terrain breakdown reflects the challenge:

• 45% single-track trails

• 46% jeep and double-track roads

• 9% pavement

Runners face a 125-hour cutoff to complete the course, pushing through heat, altitude shifts, and sleep deprivation. With elevations ranging from 1,996 feet to over 9,200 feet, it’s a test of true ultrarunning grit.

For those who dare to take it on, Cocodona is more than a race—it’s a journey across time, terrain, and personal limits.

by Pros Baron

Login to leave a comment

Dan Green Wins Cocodona 250 in Record Time Averaging 13:45 per mile

Dan Green, a seasoned endurance athlete from Huntington West Virginia, took on the grueling Cocodona 250ultramarathon across Arizona this week—and not only finished the race, he won it in spectacular fashion.

Green completed the 256.5-mile course in 58 hours, 47 minutes, and 18 seconds, setting a new course record and surpassing the previous best by over an hour. That’s an average pace of 13 minutes and 45 seconds per mile—an incredible feat considering the race includes nearly 40,000 feet of elevation gain.

The Cocodona 250 is one of the most challenging ultramarathons in the world, stretching from Black Canyon City to Flagstaff, with runners navigating desert heat, rugged mountain trails, and rocky ascents through towns like Prescott, Jerome, and Sedona. The course is roughly 45% single-track trail, 46% jeep and dirt road, and just 9% paved.

Top 5 Men’s Finishers

1. Dan Green (USA) – 58:47:18 (13:45/mi)

2. Ryan Sandes (South Africa) – 61:21:04

3. Edher Ramirez (Mexico) – 63:10:13

4. Harry Subertas – 65:28:53

5. Finn Melanson – 66:29:40

Women’s Champion

• Rachel Entrekin – 63:58:15

Set a new women’s course record by more than seven hours

Green’s calm and steady demeanor helped him manage the distance. Speaking with a reporter mid-race via video call, he said:

“Some people take it too seriously. Like why? I mean, you can have fun, still do good, and you can brighten people’s day a little better too.”

This mix of positivity and performance is exactly what the ultrarunning world thrives on—and Dan delivered both in Flagstaff.

Cocodona 250 Quick Facts

• Distance: 256.5 miles

• Elevation Gain: ~40,000 ft

• Time Limit: 125 hours

• Cutting Through: Black Canyon, Crown King, Prescott, Jerome, Sedona, Flagstaff

• Terrain Breakdown:

• 45% single-track trail

• 46% double-track/jeep road

• 9% pavement

"Congratulations to Dan Green—your new course record holder and a shining example of what grit, strategy, and a good attitude can achieve over 250+ miles," says MBR editor Bob Anderson

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Meg Eckert Smashes World Record running Over 600 Miles in Six Days

American ultrarunner Meg Eckert has just rewritten the record books. Covering a jaw-dropping 603.156 miles (970.685 kilometers) over six days, Eckert shattered the women’s six-day world record at the 24H World Challenge in Policoro, Italy, making headlines in the ultrarunning world.

The previous record of 576.6 miles (928.1 km) was held by Australia’s Dipali Cunningham, set in 2001. Eckert not only surpassed that mark—she obliterated it with consistent pacing, minimal rest, and an iron will that held up through blistering heat, exhaustion, and the mental toll of running for nearly a full week.

The six-day race is one of the ultimate endurance tests in ultrarunning, requiring not just physical toughness but strategic discipline. Athletes eat, rest, and sleep in short bursts, logging as many miles as possible around a looped course. Eckert averaged over 100 miles per day, an incredible feat. Many runners only average this in an entire month.

Eckert, 42, from the United States, has long been respected in the ultra community, but this performance launches her into an elite tier of historical significance. Her run wasn’t just about physical achievement—it was a showcase of mental strength and deep experience with multi-day racing.

“It was about being in the moment, one lap at a time,” Eckert said afterward. “I knew what I was capable of, but to actually do it… that took everything.”

As more runners continue to push the boundaries of what the human body and mind can handle, performances like Eckert’s redefine the limits of endurance running. Her new world record is expected to stand as a monumental benchmark for years to come.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

The GOAT Returns: Courtney Dauwalter Takes on the Cocodona 250 Mile Ultra

Courtney Dauwalter, widely regarded as one of the greatest ultrarunners of all time, is set to take on the formidable Cocodona 250—a 250-mile ultramarathon stretching from Phoenix to Flagstaff, Arizona. This grueling race, commencing at 5 a.m. PT on Monday, May 5, 2025, marks her first race over 200 miles since 2020 .

Born on February 13, 1985, in Hopkins, Minnesota, Dauwalter’s athletic journey began with cross-country skiing, where she became a four-time state champion during high school. She continued her athletic pursuits at the University of Denver on a cross-country skiing scholarship and later earned a master’s degree in teaching from the University of Mississippi in 2010 . Before turning professional in 2017, she taught middle and high school science in Denver.

Dauwalter’s ultrarunning career is marked by remarkable achievements. In 2023, she became the first person to win the Western States 100, Hardrock 100, and the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB) in the same year . Her victories often come with record-breaking performances, showcasing her exceptional endurance and mental fortitude.

The Cocodona 250 is a point-to-point race that challenges runners with diverse terrains, including desert landscapes, mountainous trails, and significant elevation changes. For Dauwalter, this race presents an opportunity to explore new limits. “I haven’t run a race over 200 miles since 2020,” she noted, highlighting the significance of this endeavor .

Her preparation for Cocodona has been promising. She began her 2025 season with a victory at the Crown King Scramble 50K, indicating strong form leading into this ultramarathon .

A distinctive aspect of Dauwalter’s approach is her embrace of the “Pain Cave,” a term she uses to describe the mental space where she confronts and overcomes extreme physical challenges. She visualizes it as a place to “chip away” at her limits, finding growth through adversity.

Unlike many elite athletes, Dauwalter eschews strict training regimens and coaching, opting instead for an intuitive approach that prioritizes joy and curiosity. Her philosophy centers on listening to her body and finding happiness in the process, which she believes enhances performance.

Courtney Dauwalter’s journey from a science teacher to an ultrarunning icon serves as an inspiration to athletes and non-athletes alike. Her achievements demonstrate the power of resilience, mental strength, and a passion-driven approach to pursuing one’s goals.

As she embarks on the Cocodona 250, the ultrarunning community watches with anticipation, eager to witness another chapter in the extraordinary career of this remarkable athlete.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

One Mile or One Hundred The Battle for the Soul of the Mile in 2025

In 2025, the word “mile” carries very different meanings depending on who’s lacing up their shoes. For some, it’s about blistering speed—the chase for a personal best in an all-out sprint lasting just a few intense minutes. For others, it’s about endurance, grit, and surviving a 100-mile ultramarathon—not once, but four times in one season. While one version of the mile is measured in minutes, the other is measured in days, elevation, and blisters.

Both forms of running are surging in popularity, drawing passionate athletes and growing crowds. But which “mile” speaks to you?

The Rise of the Road Mile

The road mile is back in the spotlight. Once overshadowed by the 5K and 10K, this short, intense race has re-emerged as a fan favorite. In cities across the U.S. and around the world, runners are lining up for high-stakes, high-speed showdowns that test both speed and tactical racing smarts.

One of the most iconic examples is the New Balance 5th Avenue Mile in New York City. Scheduled for Sunday, September 7, 2025, this legendary event draws elite professionals, masters athletes, and youth competitors for a one-mile drag race down Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue. With the skyline as a backdrop and cheering crowds lining the route, it offers one of the purest expressions of speed in road racing.

“It’s raw, it’s electric, and it’s over before you know it,” said one competitor who’s raced both marathons and the mile. “The road mile demands absolute precision—whether you’re aiming to break five minutes or six, you don’t get time to recover from a tactical mistake.”

Events like the Guardian Mile in Cleveland and the Grand Blue Mile in Iowa have followed suit, offering prize money, flat courses, and the kind of short-format excitement that appeals to both spectators and athletes. The mile, once seen as a track-specific discipline, has truly found a home on the road.

The Grand Slam of Ultrarunning

At the other extreme lies the Grand Slam of Ultrarunning—one of the sport’s most grueling and prestigious challenges. Often confused online with terms like “mile grand slam” due to the cumulative 400 miles of racing, the official name is simply The Grand Slam.

To earn this distinction, runners must complete four of the oldest and most iconic 100-mile trail races in the United States during a single summer. The core races typically include:

• Western States 100 (California)

• Vermont 100 Mile Endurance Run

• Leadville Trail 100 (Colorado)

• Wasatch Front 100 (Utah)

Some years permit substitutions like the Old Dominion 100, depending on scheduling. Regardless of the lineup, the difficulty is staggering: thousands of feet of elevation gain, brutal cutoffs, altitude, heat, and sleep deprivation.

“To finish one 100-miler is an accomplishment,” said a veteran ultrarunner who’s completed the Slam. “To finish four in under 16 weeks—there’s nothing like it. It’s not about speed. It’s about survival, strategy, and heart.”

Since its formal inception in the 1980s, fewer than 400 runners have completed the Grand Slam—a testament to its difficulty and prestige.

Two Extremes, One Shared Spirit

At first glance, these two uses of the word “mile” couldn’t be more different. One is sleek and fast; the other is rugged and long. One ends before your legs even start to ache; the other pushes your limits for an entire day—and night.

But at their core, both disciplines require the same fuel: dedication, discipline, and the courage to test yourself. Whether it’s the final lean in a road mile or the final climb at mile 96 of a trail race, runners in both arenas are chasing something personal—and powerful.

Final Thought

So what does the mile mean in 2025? For some, it’s a tactical burn over 1,760 yards. For others, it’s the slow, steady march of 100 trail miles—repeated four times. Either way, the mile remains one of the sport’s most meaningful measures of challenge.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

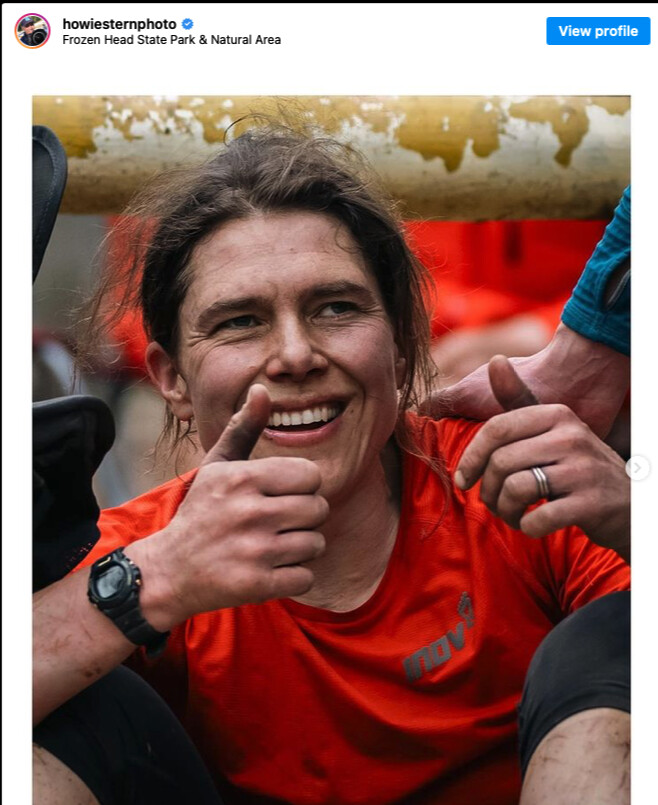

Only one women has ever finished the Barkley Marathons since it started in 1986 - Jasmin Paris

Jasmin Paris cemented her place in ultrarunning history by becoming the first woman to finish the Barkley Marathons in 2024. Known for her endurance and mental toughness, Paris completed the brutal 100-mile course in 59 hours, 58 minutes, and 21 seconds, finishing with just 99 seconds to spare.

A seasoned ultrarunner and former winner of the Spine Race, she battled extreme terrain, sleep deprivation, and navigation challenges to achieve this groundbreaking feat. Her success not only shattered barriers but also proved that women can conquer one of the toughest endurance events ever devised, inspiring runners worldwide.

The Barkley Marathons often called the hardest foot race on the planet has long been a symbol of ultimate endurance in the ultrarunning community Established in 1986 this grueling event challenges participants to complete five approximately 20 mile loops totaling around 100 miles within a 60 hour limit Historically the race has seen a minuscule completion rate with only 15 different individuals finishing between 1986 and 2022

A Surge in Finishers

The 2023 edition marked a significant shift Three runners Aurelien Sanchez John Kelly and Karel Sabbe successfully completed the course Kelly who had previously finished in 2017 was joined by Sanchez a debutant and Sabbe who had come close in prior attempts This uptick in completions prompted discussions about the race’s evolving difficulty

The trend continued in 2024 with an unprecedented five finishers

• John Kelly Secured his third completion reinforcing his status among elite ultrarunners

• Jared Campbell Achieved a remarkable fourth finish showcasing enduring resilience

• Ihor Verys A newcomer who defied expectations with a successful debut

• Greig Hamilton Demonstrated exceptional endurance to join the finishers ranks

• Jasmin Paris Made history as the first woman to complete the Barkley Marathons finishing with just 99 seconds to spare

Paris’s groundbreaking achievement garnered international attention highlighting both her personal triumph and a potential shift in the race’s perceived difficulty

Anticipating the 2025 Edition

The exact date for the 2025 Barkley Marathons remains undisclosed adhering to the event’s tradition of secrecy Historically the race occurs between mid March and early April often aligning with April Fools Day Participants typically receive a 12 hour notice before the start signaled by the blowing of a conch shell by race director Gary Lazarus Lake Cantrell

In light of the recent increase in finishers Cantrell has hinted at making the 2025 course more challenging While specific changes have not been confirmed the goal is to restore the race’s notorious difficulty potentially reducing the number of successful completions

The Barkleys Enduring Challenge

Despite the recent surge in finishers the Barkley Marathons remains an extreme test of endurance navigation and mental fortitude Each year approximately 40 runners are selected to face the unpredictable course with the vast majority unable to complete it As the 2025 edition approaches the ultrarunning community eagerly awaits to see how the race will evolve and who if anyone will overcome its relentless challenges

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

It is amazing that anyone can tackle such a course but they have including the first woman in 2024! - Bob Anderson 3/17 10:21 pm This event is insane and they are going to make the course even harder? - Bob Anderson 3/18 8:40 am |

Estefanía Unzu Sets New Spanish 100km Record in Canberra

Just under three weeks after completing the World Marathon Challenge—running seven marathons on seven continents in seven days—Spain’s Estefanía Unzu has shattered the national women’s 100km record at the Australian 100km Championship in Canberra.

On February 22, Unzu, a 39-year-old mother of eight, finished the race in 7 hours, 47 minutes, and 46 seconds. She was the first female finisher and placed second overall, just behind men’s champion Dominic Bosher, who completed the course in 7 hours, 45 minutes, and 30 seconds.

This performance broke the previous Spanish women’s 100km record of 7 hours, 52 minutes, and 21 seconds, set by Mireia Sosa in 2023. Overwhelmed with emotion, Unzu shared on social media, “I want to cry. My name will forever be a part of Spanish athletics history.”

Unzu’s achievement is particularly remarkable given her recent participation in the World Marathon Challenge, where she ran seven marathons across seven continents in one week. While many athletes require extended recovery periods after such endeavors, Unzu demonstrated exceptional resilience by promptly setting her sights on the 100km ultramarathon.

Known as “Verdeliss” on social media, Unzu has a substantial following, with nearly 1.5 million Instagram followers and over 2 million YouTube subscribers. Beyond her athletic pursuits, she is the founder and CEO of the cosmetics brand Green Cornerss and gained public attention after appearing on the sixth season of the Bulgarian reality show VIP Brother in 2014.

In May 2024, Unzu won the 100km distance at the Spanish National Ultra Marathon Championship with a time of 7 hours, 59 minutes, and 30 seconds. Her recent accomplishments have solidified her status as one of Spain’s premier endurance athletes, inspiring many with her ability to balance elite athletic performance and family life.

As Spain celebrates its new national record holder, the ultrarunning community eagerly anticipates Unzu’s future endeavors, confident that her determination and drive will lead to more groundbreaking achievements.

Login to leave a comment

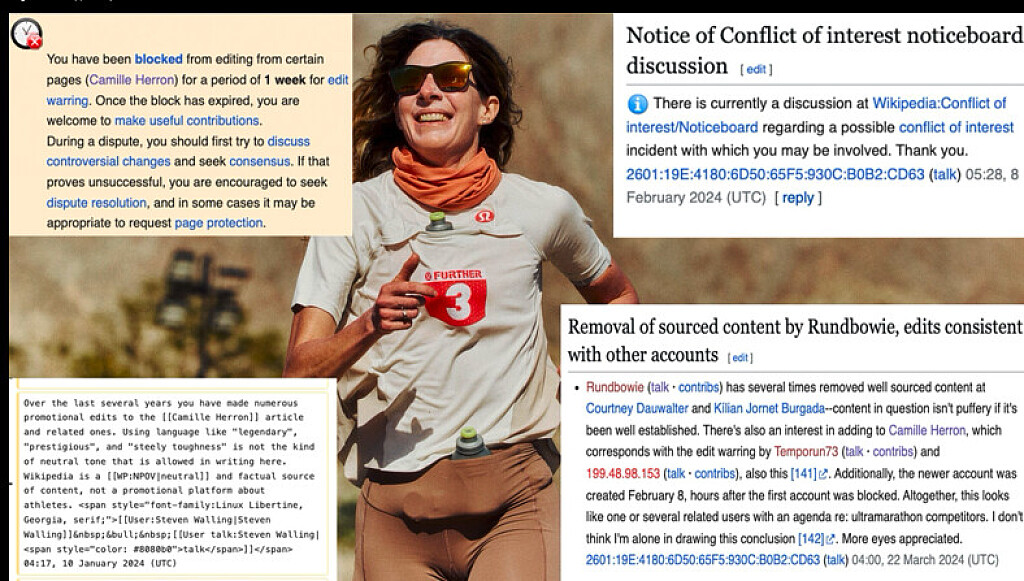

Camille Herron and the Wikipedia Controversy: Integrity in Ultrarunning Under Scrutiny

Update: after reading our article Camille sent this to MBR "Individuals are violating World Athletic rules and publicly claiming they broke my records. It’s undermining the integrity of the sport and devaluing those who adhere to the rules and the ratified record holders, including me.

I hope Yiannis’s statement provides added clarity who’s behind the push to disregard the rules and retaliated against me."

Camille Herron recently addressed the Wikipedia controversy on her Facebook page, expressing her commitment to fairness and accountability in ultrarunning. She acknowledged the challenges of speaking up about rules and technicalities, noting that it can lead to retaliation.

Herron emphasized that the International Association of Ultrarunners (IAU) has validated her concerns twice, confirming that she continues to hold the IAU World Records and World Bests for 48 Hours and 6 Days. She concluded by thanking her supporters and reaffirming her dedication to integrity in the sport.

In September 2024, the ultrarunning community was shaken by a controversy involving American ultrarunner Camille Herron and her husband and coach, Conor Holt. The couple was accused of editing Wikipedia pages to enhance Herron's achievements while diminishing those of her competitors.

An investigation by Canadian Running revealed that two Wikipedia accounts, "Temporun73" and "Rundbowie," were linked to Herron's email and Holt's IP address. These accounts made numerous edits to Herron's page, amplifying her accomplishments, and altered the pages of fellow ultrarunners, including Courtney Dauwalter and Kilian Jornet, to downplay their achievements. For instance, statements like "widely regarded as one of the best trail runners ever" were removed from competitors' pages, while Herron was described as "widely regarded as one of the greatest ultramarathon runners of all time."

Following the exposure of these activities, Herron's primary sponsor, Lululemon, terminated their partnership with her. In a statement, the company emphasized its commitment to equitable competition and stated, "After careful consideration and conversation, we have decided to end our ambassador partnership with Camille."

In response to the allegations, Holt took full responsibility, stating, "Camille had nothing to do with this. I'm 100 percent responsible and apologize [to] any athletes affected by this and the wrong I did." He explained that his actions were an attempt to protect Herron from online harassment and bullying that had adversely affected her mental health.

The incident has sparked widespread discussion within the ultrarunning community, with many expressing disappointment over the unsportsmanlike behavior. Herron, known for her numerous world records and contributions to the sport, now faces challenges in rebuilding trust and credibility within the community.

As the situation unfolds, it serves as a reminder of the importance of integrity and sportsmanship in athletics. The ultrarunning community continues to reflect on the implications of this controversy and the lessons to be learned moving forward.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Pushing the Limits: Sophie Power Sets a New Women’s 48-Hour Treadmill World Record

The treadmill, often seen as a monotonous exercise machine, became a stage for human endurance and determination when ultrarunner and campaigner Sophie Power set a remarkable new world record. At this year's National Running Show, Sophie achieved the seemingly impossible, running 370.9 kilometers (230.5 miles) on a treadmill in 48 hours non-stop. This astonishing feat earned her the women's 48-hour treadmill world record, inspiring countless others to challenge their limits.

Sophie, a mother and well-known advocate for women in sports, approached the challenge with her characteristic determination and grit. She demonstrated not just physical endurance but also mental resilience, as running continuously on a treadmill for two days tests the mind as much as the body. "The treadmill is a space where you can push your boundaries, where it's just you and your willpower," Sophie shared after her record-breaking performance.

Her journey to this achievement wasn't without its difficulties. Sophie balanced a strict training regimen with her personal and professional commitments. As an ultrarunner, she is no stranger to grueling physical challenges, having previously competed in some of the toughest endurance races worldwide. But the treadmill, an environment devoid of changing scenery and external stimuli, posed a unique and formidable challenge.

The National Running Show provided the perfect backdrop for Sophie's attempt, with spectators and supporters cheering her on through every step of her journey. The energy from the crowd fueled her determination, proving the power of community and encouragement in achieving seemingly insurmountable goals.

Sophie's record stands as a testament to human capability and the idea that limits exist only in the mind. By running over 370 kilometers in two days, she not only set a new benchmark in the world of ultrarunning but also inspired countless others to embrace challenges, however daunting they may seem.

Her accomplishment reminds us all that with determination, preparation, and resilience, we can achieve extraordinary things even on a treadmill.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

230 miles in 48 hours! Maybe I have run that many miles over three weeks when I was much younger. An amazing number of miles. - Bob Anderson 1/31 7:03 am |

5 Reasons to run outside all winter—and get stronger, tougher, faster, healthier and happier

In the winter of 1939, when the military posted Swedish miler Gundar Hagg to the far north of that nordic country, he devised a unique training program of running on trails through knee- or hip-deep snow. Most days he would do 2500 meters in snow for strength, followed by 2500 meters on a cleared road for turn-over. But during those times when he couldn’t find cleared roads—sometimes for weeks—he’d run up to the full 5-kilometers in snow. The next summer he set huge PRs, coming within one second of the mile world record.

Hagg continued his routine in subsequent winters, devising a hilly 5K loop in a different locale that trudged through snowy forest for 3000 meters then ended with a 2000 meter stretch of road where he could run at full speed. He kept improving, and the summer of 1942 he set 10 world records between the 1500 and 5,000 meters.

While Hagg’s routine was created out of necessity, he obviously valued the snowy training. When he moved to a city with a milder climate, he wrote in a training journal, “It will be harder running than any previous year. Probably there won’t be much snow.” And every winter he scheduled trips north to train on the familiar, tough, snowy trails.

Hagg isn’t the only runner who has found winter training valuable. Roger Robinson, who raced internationally for England and New Zealand in the 1960s before setting masters road records in the ‘80s, recalls his training for the deep-winter English cross country championships of the 1950’s and 60s. “We ran, often at race pace, over snow, mud, puddles, deep leaves, ploughed fields, scratchy stubble, stumpy grass, sticky clay, sheep-poo, whatever, uphill and down,” Robinson says. “And thus, without going near a gym or a machine, we developed strength, spring, flexibility, and stride versatility that also paid off later on the road or track; I made one of my biggest track breakthroughs after a winter spent running long intervals on a terrain of steep hills and soft shifting sand.”

Robinson, now 85, with two artificial knees, still runs in the cold and slop. “Running is still in great part about feeling the surfaces and shape of the earth under my feet,” he says.

Hagg and Robinson are of a different generation than those of us with web-connected treadmills that can let us run any course on earth from the comfort of our basement, but they’re on to something we might still benefit from: winter can be an effective training tool. Here are five reasons you’ll want to bundle up and head out regardless of the conditions, indeed, why you can delight when it is particularly nasty out.

1) Winter Running Makes You Strong

As Hagg demonstrated and Robinson points out, winter conditions work muscles and tendons you’d never recruit on the smooth, dry path. A deep-winter run often ends up being as diverse as a set of form and flexibility drills: high knees, bounds, skips, side-lunges, one-leg balancing.

Bill Aris, coach of the perennially-successful Fayetteville-Manlius high school programs, believes that tough winter conditions are ideal for off-season training that has the goal of building aerobic and muscular strength. He sends the kids out every day during the upstate New York winter, and says they come back, “sweating, exhausted and smiling, feeling like they have completely worked every system in their bodies.”

2) Winter Running Makes You Tough

No matter how much you know it is good for you and that you’ll be glad when you’re done, it takes gumption to bundle up, get out the door and face the wintry blast day after day. But besides getting physically stronger, you’re also building mental steel. When you’ve battled snow and slop, darkness and biting winds all winter, the challenges of distance, hills and speed will seem tame come spring.

3) Winter Running Improves Your Stride

Running on the same smooth, flat ground every day can lead to running ruts. Our neuromuscular patterns become calcified and the same muscles get used repeatedly. This makes running feel easier, but it also predisposes us to injury and prevents us from improving our stride as we get fitter or improve our strength and mobility. Introducing a variety of surfaces and uncertain footplants shakes up our stride, recruits different muscles in different movement patterns, and makes our stride more effective and robust as new patterns are discovered.

You can create this stride shake-up by hitting a technical trail. But as Megan Roche, physician, ultrarunning champion, clinical researcher at Stanford and Strava running coach, points out, “A lot of runners don’t have access to trails. Many runners are running on flat ground, roads—having snow and ice is actually helpful, makes it like a trail.”

In addition to creating variety, slippery winter conditions also encourage elements of an efficient, low-impact stride. “One thing running on snow or ice reinforces is a high turn over rate and a bit more mindfulness of where your feet are hitting the ground,” Roche says. “And those two things combine to a reduced injury risk.” After a winter of taking quicker, more balanced strides, those patterns will persist, and you’ll be a smoother, more durable runner when you start speeding up and going longer on clearer roads.

4) Winter Running Makes You Healthier

“Exercising in general, particularly during periods of higher cold or flu season has a protective effect in terms of the immune system,” says Roche. You get this benefit by getting your heart rate up and getting moving even indoors, but Roche says, “Getting outside is generally preferable—fresh air has its own positive effect.”

Cathy Fieseler, ultrarunner, sports physician, and chairman of the board of directors of the International Institute of Race Medicine (IIRM), says there’s not much scientific literature to prove it, but agrees that in her experience getting outside has health benefits. “In cold weather the furnace heat in the house dries up your throat and thickens the mucous in the sinuses,” Fieseler says. “The cold air clears this out; it really clears your head.”

Fieseler warns, however, that cold can trigger bronchospasms in those with asthma, and Roche suggests that when it gets really cold you wear a balaclava or scarf over your mouth to hold some heat in and keep your lungs warmer. “Anything below zero, you need to be dressed really well and mindful of your lungs, making sure that you’re not exposing your lungs to too cold for too long,” Roche says.

5) Winter Running Makes You Feel Better

For all its training and health benefits, the thing that will most likely get most of us out the door on white and windy days is that it makes us feel great. “A number of runners that I coach and that I see in clinics suffer from feeling more depressed or a little bit lower in winter,” says Roche. “Running is a great way to combat that. There’s something really freeing about getting out doors, feeling the fresh air and having that outdoor stress release.”

Research shows that getting outside is qualitatively different than exercising indoors. A 2011 systematic review of related studies concluded, “Compared with exercising indoors, exercising in natural environments was associated with greater feelings of revitalization and positive engagement, decreases in tension, confusion, anger, and depression, and increased energy.” They also found that “participants reported greater enjoyment and satisfaction with outdoor activity and declared a greater intent to repeat the activity at a later date.”

That “intent to repeat” is important. Running becomes easier and more enjoyable, the more you do it. “Consist running is really the most fun running,” Roche says. “It takes four weeks of consistency to really feel good. Your body just locks into it.”

Most people associate consistency with discipline, and setting goals and being accountable is an effective way to build a consistent habit. Strava data shows that people who set goals are much more consistent and persistent in their activities throughout the year. The desire to achieve a goal can help overcome that moment of inertia when we’re weighing current comfort with potential enjoyment.

But the best way to create long-term consistency is learning to love the run itself. Runners who make it a regular part of their life talk little about discipline and more about how much they appreciate the chance to escape and to experience the world on their run each day—even, perhaps especially, on the blustery, cold, sloppy ones.

Login to leave a comment

How Did Courtney Dauwalter Get So Damn Good?

If Courtney Dauwalter could travel back in time, this is what she would do: She’d join a wagon train crossing the American continent, Oregon Trail-style, for a week, maybe more, just to see if she could swing it. It would be hard, and also pretty smelly, but Dauwalter wonders what type of person she’d be if she deliberately decided to take that journey. Would she stop in the plains and build a farm? Could she make it to the Rocky Mountains? How much suffering could she take, and how daunted might she be by the terrain ahead of her?

“If you get to Denver and this huge mountain range is coming out of the earth, are you the type of person who stops and thinks, ‘This is good’?” she wonders. “Or are you the person who’s like, ‘What’s on the other side?’ ”

Dauwalter is probably (definitely) the best female trail runner in the world—a once-in-a-generation athlete. She’s hard to miss at the sport’s most famous races, and not just because of the nineties-style basketball shorts she prefers. (Her explanation: she just likes them.) It’s because she’s often running among the leading men in the sport, smiling beneath her mirrored sunglasses. The 39-year-old is five foot seven and lean, with smile lines and hair streaked with highlights from abundant time spent in high-altitude sun.

Dauwalter shared her historical daydream with me while sipping a pink sparkling water at her house in Leadville, Colorado, after a four-hour morning training run. Her cross-country wagon musings get at why she’s the best female ultrarunner ever to live: Dauwalter is curious. She’s curious about pain, about limits, about possibility. This quality is fundamental to what makes her so good.

Over the past eight years, Dauwalter has won almost everything she’s entered. In 2016, she set a course record at the Javelina Jundred—an exposed, looped route through the Sonoran Desert of Arizona. That same year she won the Run Rabbit Run 100-miler in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, by a margin of 75 minutes, despite experiencing temporary blindness for the last 12 miles (she could only see a foggy sliver of her own feet). Because of ultrarunning’s huge distances, it’s not unheard of to beat the competition by so much, but it doesn’t happen with the frequency that Dauwalter manages.

In 2018, she won the extremely competitive Western States 100 in California; it was her first time on the course. A year later, she set a new course record while winning the prestigious Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB), besting the second-place finisher by just under an hour. In 2022, she set the fastest known time on the 166.9-mile Collegiate Loop Trail in her backyard in Colorado, and she won (and set a new course record at) the Hardrock 100, a grueling high-altitude loop through the state’s San Juan Mountains.

Dauwalter is also one of the few runners of her caliber to seriously dabble in the really long distance races. In 2017, she won the Moab 240—yes, that’s 240 miles—in two days, nine hours, and fifty-five minutes, ten hours ahead of the second-place finisher. She ran even farther at Big’s Backyard Ultra in 2020, a quirky test of wills where athletes complete a 4.167-mile course every hour on the hour until only one runner is left. Dauwalter set a women’s course record of just over 283 miles.

Given everything she’s accomplished, it’s hard to believe that the past two summers have been her most successful yet. In 2023, she returned to Western States, where she smashed the women’s course record by more than an hour and finished sixth overall. When she passed Jeff Colt, who finished ninth, he remembers how calm and collected she looked, running all alone. “My pacer looked back at me and said, ‘Jeff, I can’t even keep up with her right now,’ ” he says. Less than three weeks later, she won Hardrock again, taking fourth place overall and setting a new women’s course record. The race changes direction on the looped course each year, and she now holds both the clockwise and counterclockwise records.

In the interest of testing herself one more time, in late August she traveled to France to run UTMB again. She won that race too, becoming the first person in history to win all three races in a single summer. “She’s one of those humans who defy even the concept of an outlier,” says Clare Gallagher, a former Western States winner who has raced against Dauwalter. “I look at her summer and I have no words. It’s truly hard to conceptualize.”

Dauwalter led UTMB from the start, and she finished more than an hour ahead of the woman in second place. As she descended the final stretch of trail, she was followed by a barrage of cameras and a handful of people who looked like they just wanted a bit of her magic to rub off on them. As crowds roared on either side of the finish line in Chamonix, she looked back at the spectators and clapped in their direction, never raising her hands above her head or pumping her fists in the air. After hugging her parents and her husband, 39-year-old Kevin Schmidt, she jogged back in the direction she’d just come to high-five hundreds of fans.

Dauwalter grew up in the suburbs of Minneapolis, in a tight-knit family that was always active. The kids all played soccer, and when they weren’t at practice they were busy building tree forts or making up games at the local park. In seventh grade, she started running cross-country, and in eighth grade she joined the nordic ski team. She claims to have spent the first years just trying to stay upright, but in high school she went on to be a four-time state nordic ski champion and attended the University of Denver on a cross-country-skiing scholarship. She says that her parents, who now frequently crew and support her at races, led by example. “You work hard, you give everything you’ve got, you don’t forget to have fun,” she says.

Minnesota winters are notoriously cold, and she credits her ability to dig deep within herself to the unforgiving conditions. “Growing up there, you just learn to do stuff, regardless of the weather,” she says. She also points to a cross-country coach who taught her to think differently about pain. “He laid the groundwork for understanding that our bodies are capable of so much,” she says. “We can push past those initial signals saying that’s all I have and turn the knob, and there’s always one more gear.”

After college, Dauwalter taught middle and high school science in Denver, which is where she met Schmidt. “A woman I worked with and a guy he worked with were married, and they just kept putting us in the same places,” she says. “I didn’t know they were meddling!” Schmidt, who works as a software engineer, is also a competitive runner. He and Dauwalter train together—sometimes he’ll join in for her second run of the day—and they trade off supporting each other during races. When I met up with them in Leadville, Dauwalter had just finished crewing for Schmidt at a 100-miler in Switzerland. During her races, he maps her splits, takes care of her aid-station needs, and serves as crew captain. He’s the “spreadsheet brain” to her “tie-dye brain,” as he puts it, and he provides emotional support too.

“Its clear to me when she has taken up residence in the pain cave, so I try my best to fill it with snacks and encouragement,” says Schmidt. One time, while driving to an aid station during a race, Schmidt got a flat tire while carrying everything Dauwalter needed for the night. He wound up sprinting the final three miles to catch her in time.

When Dauwalter started racing more competitively and winning, she and Schmidt had a series of discussions about what they wanted their lives to look like. Ultimately, they decided that she should try to give professional running a shot. In 2017, without a sponsor and with a lot of unknowns still ahead, she left teaching to run full-time. “What we wanted was to look back when we were 90 years old and not wonder what if? about anything,” she says.

Mike Ambrose, the former team manager at Salomon, offered Dauwalter her first sponsorship as a trail runner that same year. She was still new on the scene, but Ambrose could see that she was driven, and the talent was there. “She’s super curious about pushing herself,” he says. “She had this huge engine coming from nordic skiing, and her 24-hour time was really crazy. I thought, well, if she just figures it out and gets more trail experience, she obviously has the mental and physical capacity.”

Despite her nearly superhuman athleticism and mental fortitude, Dauwalter is also very normal. She likes nachos, candy, and beer. She watches sports (the Vikings are her NFL team, even though she’s been in Broncos territory for years), and she wants to spend time with the people she loves, including her parents, and the friends who often crew for her.

Ultrarunning frequently sees short-lived stars, runners who dominate for a couple of years before burning out or slowing down, either from overtraining or simply from the passage of time and the wear on their bodies. Dauwalter, however, seems to have a rare capacity to push against her own limits without tipping over the edge. She’s been running long distances at an elite level for seven years now. Gallagher wonders how she’s managed to avoid injury, given Dauwalter’s volume of physically demanding races.

Login to leave a comment

Hayden Hawks Named 2024 UltraRunner of the Year

Hayden Hawks has been named the 2024 UltraRunner of the Year, cementing his status as one of the most accomplished athletes in ultrarunning. The recognition comes after a stellar season highlighted by victories in some of the world’s most prestigious ultra-distance races.

The Cedar City, Utah native delivered standout performances, including a victory at the Courmayeur-Champex-Chamonix (CCC) 101K on Mont Blanc. Known as one of the toughest races in the Ultra-Trail World Tour, the CCC is a proving ground for elite ultrarunners, and Hawks’ 10:20:11 finish solidified his dominance on the global stage.

He also claimed victory at the highly competitive Black Canyon 100K in Arizona, where he not only won but set a new course record with a time of 7:30:18. His season was rounded out with podium finishes at races like the Western States 100, where he placed third in 14:24:31, and the Julian Alps Ultra-Trail in Switzerland, where he finished second.

Hawks lives in Cedar City with his wife, Ashley, and their two children. Balancing a demanding training schedule with family life, he credits his support system for his success, calling his family his “greatest motivation.”

Hawks’ achievements in 2024 highlight his versatility across different terrains and conditions. Whether racing on the mountainous trails of Europe or the arid landscapes of the American West, Hawks has consistently demonstrated his ability to adapt and excel. His Black Canyon course record and CCC triumph underscore his speed, endurance, and tactical prowess.

As the 2024 UltraRunner of the Year, Hayden Hawks has not only etched his name into the sport’s history but also inspired countless runners worldwide to push their limits. With a career that continues to rise, the running community eagerly awaits what 2025 will bring for this ultrarunning star.

Login to leave a comment

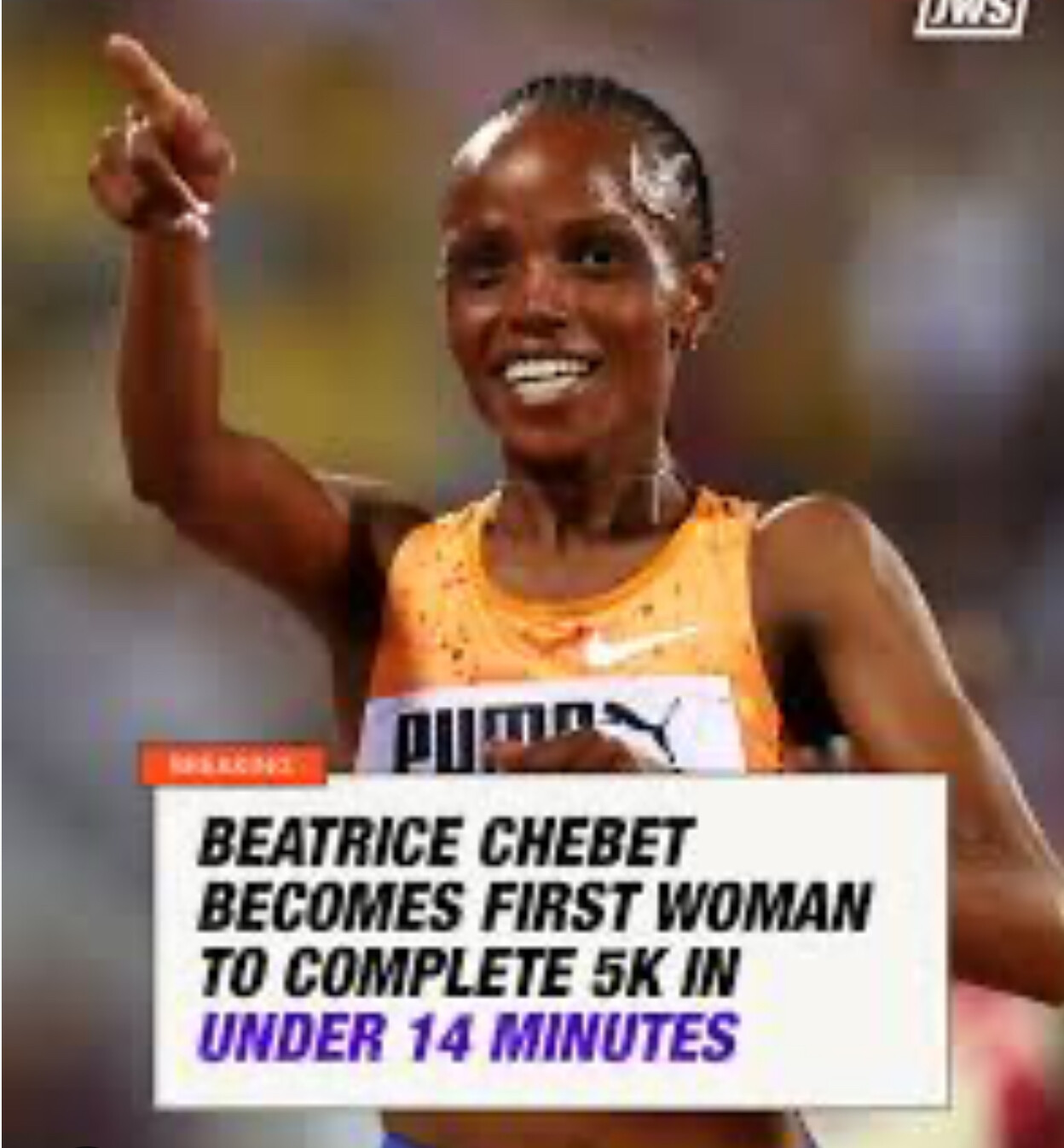

The Distance Running Scene in 2024: A Year of Remarkable Achievements

The global distance running scene in 2024 was marked by incredible performances, new records, and innovative approaches to training and competition. From marathons in bustling city streets to ultramarathons through rugged terrains, the year showcased the resilience, determination, and evolution of athletes from all corners of the globe.

The World Marathon Majors—Tokyo, Boston, London, Berlin, Chicago, and New York—continued to be the centerpiece of elite distance running, each event contributing to a year of unprecedented performances and milestones.

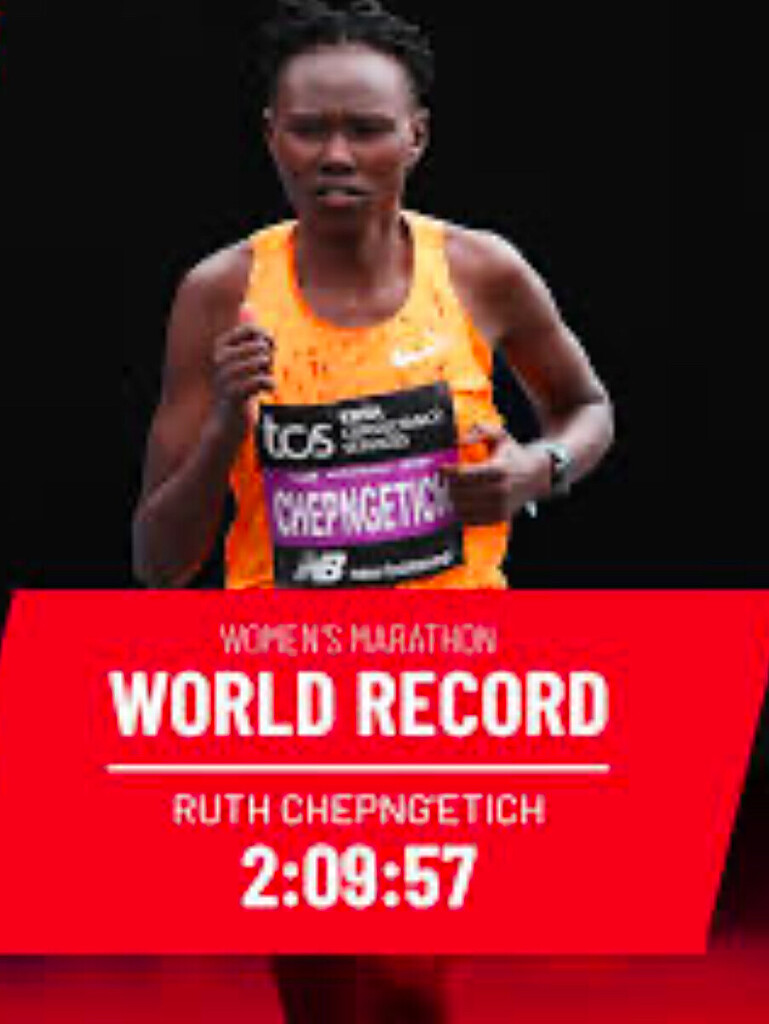

Tokyo Marathon witnessed a remarkable performance by Kenya's Ruth Chepngetich, who set a new women's marathon world record with a time of 2:11:24. This achievement sparked discussions about the rapid advancements in women's long-distance running and the influence of technology in the sport.

In the Boston Marathon, Ethiopia's Amane Beriso delivered a dominant performance, winning in 2:18:01. On the men's side, Kenya's Evans Chebet defended his title, highlighting Boston's reputation for tactical racing over sheer speed.

London Marathon saw Ethiopia's Tamirat Tola take the men's crown, besting the field with a strong tactical race. Eliud Kipchoge, despite high expectations, did not claim victory, signaling the growing competitiveness at the top of men’s marathoning. On the women's side, Kenya's Peres Jepchirchir triumphed, adding another major victory to her impressive resume.

The Berlin Marathon in 2024 showcased yet another extraordinary performance on its fast course, though it was Kelvin Kiptum’s world record from the 2023 Chicago Marathon (2:00:35) that remained untouched. In 2024, Berlin hosted strong fields but no records, leaving Kiptum’s achievement as the defining benchmark for men’s marathoning.

The Chicago Marathon was the highlight of the year, where Kenya's Ruth Chepngetich made history by becoming the first woman to run a marathon in under 2:10. She shattered the previous world record by nearly two minutes, finishing in 2:09:56. This groundbreaking achievement redefined the possibilities in women's distance running and underscored the remarkable progress in 2024.

The New York City Marathon showcased the depth of talent in American distance running, with emerging athletes achieving podium finishes and signaling a resurgence on the global stage.

Each marathon in 2024 was marked by extraordinary performances, with athletes pushing the boundaries of human endurance and setting new benchmarks in the sport.

Olympic Preparations: Paris 2024 Looms Large

With the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris just around the corner, many athletes used the year to fine-tune their preparations. Qualifying events across the globe witnessed fierce competition as runners vied for spots on their national teams.

Countries like Kenya, Ethiopia, Japan, and the United States showcased their depth, with surprising performances by athletes who emerged as dark horses. Japan’s marathon team, bolstered by its rigorous national selection process, entered the Olympic year as a force to be reckoned with, particularly in the men's race.

Ultramarathons: The Rise of the 100-Mile Phenomenon

The ultramarathon scene continued to grow in popularity, with races like the Western States 100, UTMB (Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc), and Leadville 100 drawing record participation and attention.

Courtney Dauwalter, already a legend in the sport, extended her dominance with wins at both UTMB and the Western States 100, solidifying her reputation as the GOAT (Greatest of All Time) in ultrarunning.

On the men’s side, Spain’s Kilian Jornet returned to form after an injury-plagued 2023, capturing his fifth UTMB title. His performance was a masterclass in pacing and strategy, showcasing why he remains a fan favorite.