Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #running streak

Today's Running News

Jon Sutherland’s 55 Year World Record Running Streak is being challenged

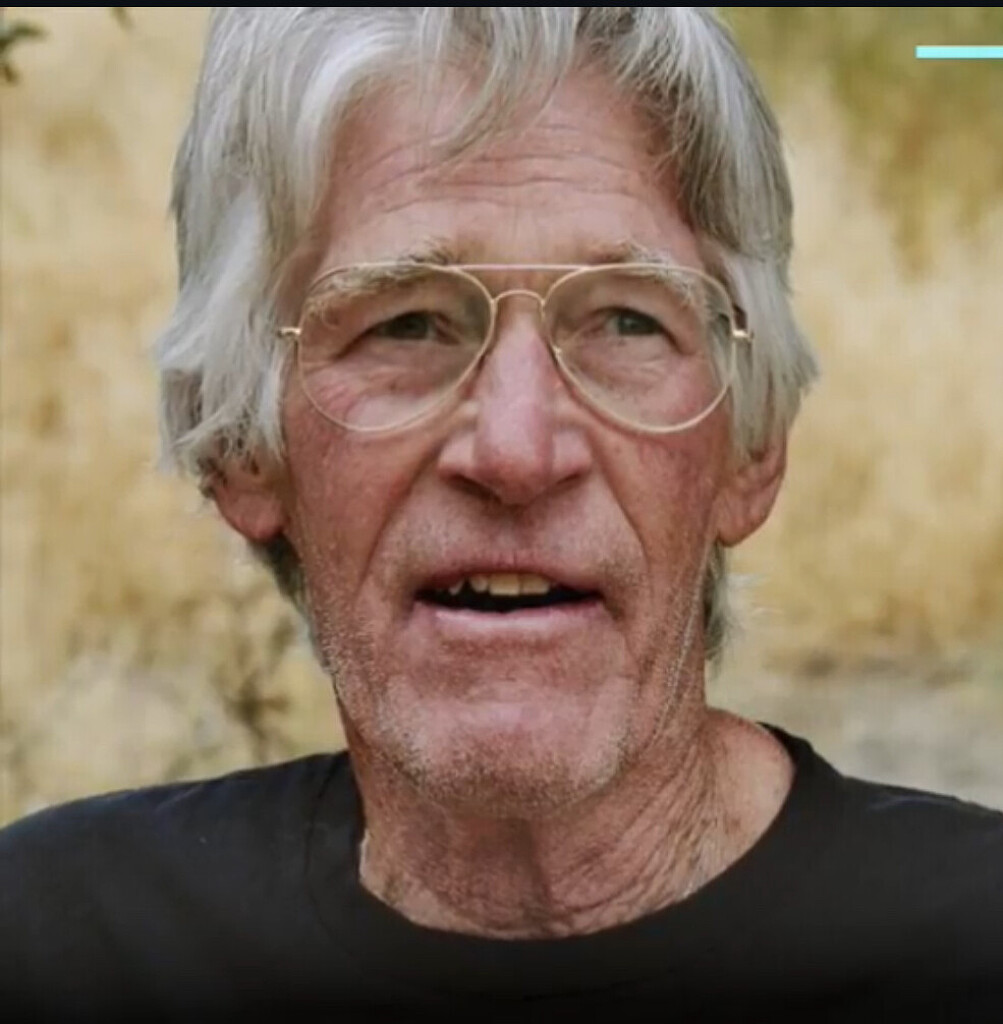

Jon Sutherland of Washington, Utah, officially ended the longest consecutive daily running streak in history on December 31, 2024. He ran every single day for 55 years, 7 months, and 6 days, totaling 20,309 consecutive days—a record of unmatched consistency, discipline, and passion for the sport.

Sutherland began his streak on May 29, 1969, at just 19 years old. Over five and a half decades later, now 74, he finally decided to hang up the streak—but not before cementing himself in the annals of running history.

For perspective, that’s nearly two-thirds of a century without missing a single day. Rain, injury, illness—none of it stopped him from getting in at least one mile daily. Though not all of those runs were fast or long, the sheer volume of uninterrupted effort is unparalleled.

Interestingly, just behind Sutherland on the all-time list is Jim G. Pearson, who began his still-active streak on February 16, 1970, in Marysville, Washington. Pearson, now 81, has logged 20,236 consecutive days (55.4 years) as of today—meaning he could soon surpass Sutherland’s final total if he keeps going.

As of now, Jon Sutherland holds the record for the longest running streak ever completed.

If you’ve ever skipped a run because of bad weather or a sore ankle, let Jon’s example remind you what commitment really looks like.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Emily Infeld: Olympian, Streak-Holder, and Inspiration for Runners Everywhere

Olympian Emily Infeld recently shared a heartwarming post on Facebook about two significant running streaks in her household—her husband’s incredible 21-year run streak and her own 21-year streak of running sub-5-minute miles. While both accomplishments reflect remarkable consistency and dedication, Emily’s streak is a unique marker of her speed and longevity as an elite runner.

Emily’s sub-5-mile streak began in 2005 during her freshman year of high school when she first broke the coveted barrier. Now, 21 years later, she continues to hit this milestone each year, either in a race or during training sessions. Her most recent achievement came just this week, when she clocked her first sub-5-minute mile of 2025 during a workout.

“Thinking back, I realized that I’ve broken 5 minutes in the mile every year since [2005],” Infeld wrote. “All of that is to say this lil streak made me feel proud, and now that it’s 21 years strong, I want to see how much longer I can continue it!”

Infeld, a 2016 Olympian and world-class distance runner, has a storied career that includes a bronze medal at the 2015 World Championships in the 10,000 meters. Known for her resilience and positive attitude, she’s a celebrated figure in the running community and an inspiration to athletes of all levels.

She also took a moment to celebrate her husband’s run streak, which has lasted an astonishing 21 years. (Third photo is her husband out front of their new home.) While her own streak involves hitting sub-5-minute miles annually, her husband’s dedication to daily runs highlights another side of the running spectrum: the mental and physical discipline to show up every day, no matter the circumstances.

“Cheers to anyone doing a run streak, even if you don’t realize it yet,” Emily added in her post, offering encouragement to runners pursuing their own goals.

Emily’s story reminds us that streaks, whether built on speed or consistency, are deeply personal and worth celebrating. Her combination of elite-level achievement and her genuine passion for running exemplify what makes the sport so special: there’s room for everyone to find meaning, motivation, and pride in their journey.

As Emily continues her streak of sub-5-minute miles into its 22nd year, she inspires us all to reflect on the milestones—big or small—that keep us moving forward. Whether you’re chasing personal records, daily runs, or simply a love for the sport, Emily’s story proves that every streak starts with a single step.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Florida man reaches 50-year run streak

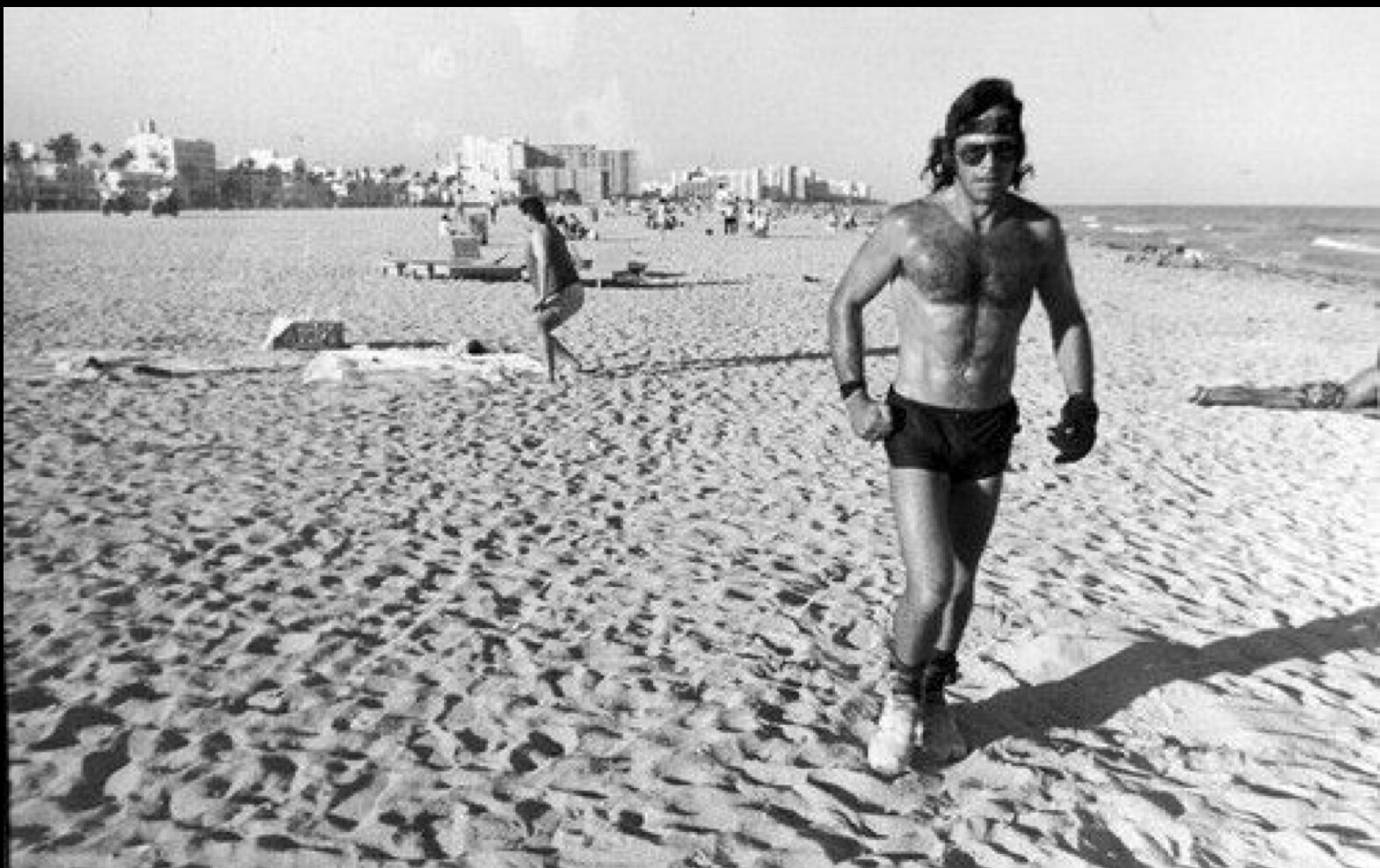

Miami’s Robert “Raven” Kraft was streaking long before it was cool, and not in the way that gets you arrested. On Tuesday afternoon at 5th Street Lifeguard Station in Miami’s South Beach neighbourhood, Kraft completed his 18,263rd run, marking an impressive 50-year streak of daily running.

Kraft began his prolific streak on January 1, 1975, when he was 24, and over half a century later, he’s amassed 18,263 total runs and over 234,000 kilometres. That’s roughly equivalent to walking around the world more than five and a half times—quite a feat!

The 74-year-old was joined on Tuesday by hundreds of runners for his daily tradition of running eight miles (12.87 km) along the sands of South Beach. Kraft, who has also been a singer and songwriter for just as long, played a few songs after his anniversary run alongside the Dark Shadows band.

Beyond the streak, Kraft has built a community around his daily runs, called the “Raven Runners.” Unlike most, Kraft’s eight-mile route has never changed. He has reportedly run the exact same route in almost every single run. In an interview with Sports Illustrated, Kraft said he has a list of more than 3,700 runners from around the globe who have joined him for a run over the past 50 years. “The Raven List” reflects that he has been joined by runners from all 50 states, as well as runners from more than 60 countries.

Kraft’s legacy will soon be etched into Miami Beach’s history. On Jan 1, Third Street and Ocean Drive will reportedly be renamed “Robert ‘Raven’ Kraft Way.”

According to the United States Running Streak Association, Kraft has the sixth-longest active run streak. Jon Sutherland of Washington, Utah, holds the world’s longest-running streak with over 55 years (20,000+ days). Toronto’s Rick Rayman has the longest active run streak in Canada, with a total of 16,824 days (46+ years).

Login to leave a comment

Florida man reaches 50-year run streak

Miami’s Robert “Raven” Kraft was streaking long before it was cool, and not in the way that gets you arrested. On Tuesday afternoon at 5th Street Lifeguard Station in Miami’s South Beach neighbourhood, Kraft completed his 18,263rd run, marking an impressive 50-year streak of daily running.

Kraft began his prolific streak on January 1, 1975, when he was 24, and over half a century later, he’s amassed 18,263 total runs and over 234,000 kilometres. That’s roughly equivalent to walking around the world more than five and a half times—quite a feat!

The 74-year-old was joined on Tuesday by hundreds of runners for his daily tradition of running eight miles (12.87 km) along the sands of South Beach. Kraft, who has also been a singer and songwriter for just as long, played a few songs after his anniversary run alongside the Dark Shadows band.

Beyond the streak, Kraft has built a community around his daily runs, called the “Raven Runners.” Unlike most, Kraft’s eight-mile route has never changed. He has reportedly run the exact same route in almost every single run. In an interview with Sports Illustrated, Kraft said he has a list of more than 3,700 runners from around the globe who have joined him for a run over the past 50 years. “The Raven List” reflects that he has been joined by runners from all 50 states, as well as runners from more than 60 countries.

Kraft’s legacy will soon be etched into Miami Beach’s history. On Jan 1, Third Street and Ocean Drive will reportedly be renamed “Robert ‘Raven’ Kraft Way.”

According to the United States Running Streak Association, Kraft has the sixth-longest active run streak. Jon Sutherland of Washington, Utah, holds the world’s longest-running streak with over 55 years (20,000+ days). Toronto’s Rick Rayman has the longest active run streak in Canada, with a total of 16,824 days (46+ years).

by Marley Dickinson

Login to leave a comment

What’s Your Why? Our Readers Share Their Biggest Motivators for Getting Out There to Run

We asked runners what motivates them to get out and hit the road—their answers may inspire you.

Why do you run? If you’ve never thought about it before, ask yourself now.

Being intentional about the reason why you run is a crucial part of maintaining motivation, especially if you’re just starting your running journey. Most of us know the research-backed benefits of running, but what is going to be that thing that gets you out the door when you don’t even feel like moving?

While your reason should be unique and personal to you, here’s some inspiration from our dedicated Runner’s World+ members and social audiences on Instagram and Facebook to keep in mind when considering what your why is.

For Myself

“Running is my ‘me time.’ It is time for me to simply run, listen to music, and enjoy the outdoors. It allows me to begin each day with a sense of accomplishment, and along the way I plan my to-do list, calculate finances, and solve problems. I do my best thinking when I am running. It also keeps me focused on my health and I always have at least one half marathon or marathon to train for.”—Jill Pompi (RW+ member)

“Because it’s the only thing in my life that’s just mine.”—April Thomson

“As a mom of three littles, running is my ‘me time.’ Time to fill my own cup; time to work toward a personal goal; time to show my kids that I enjoy movement simply because it helps me be happy, healthy, and strong!”—Marlena Shaw (RW+ member)

“It’s my time—no one asking me for anything. It’s me vs. me. Love the feeling after a long run.”—Spullins JB

“Running is just for me, and I run so I can be my best self. I don’t mean physically. Sure, I love how strong my legs feel when I cross a finish line or that good burn after a long run. But my best self is found when I hit the pavement and process whatever is going on in my life. I have two young kids (ages 3 and 14 months), and I am constantly being poked, pulled, and called. When I lace up my running shoes, the stress melts away and I am a better mother because of it.”—Melissa Hofstrand (RW+ member)

“To escape from reality for a brief moment and enjoy my ME time.”—Yuri Aguilar

“Sometimes to relax, regroup, and shake out anything bothering me… but usually to start my day off just right!”—Erin Carey Ryan

For My Health

“My health, specifically my heart.”—Kati Johnson (RW+ member)

“To maintain my health and challenge myself to reach new running goals.”—Gwen Jacobson (RW+ member)

“To fight bad genetics and hear my grandkids say, ‘Whoa, Grandma!’”—Michele (RW+ member)

“My asthma kept me from doing exercise for so many years. I’m running because I can finally do something I never thought possible.”—Patricia McHugh (RW+ member)

“To save my life. I am type 2 diabetic by way of having PCOS. By the time I was diagnosed with PCOS, I had developed full-blown diabetes. I run now to train for a half marathon I crazily signed up for and to get in shape for my first century ride next year. I will run and bike towards a cure.”—Stephanie Gold (RW+ member)

“I exercise and stay active so that I can be mobile and independent as long as possible as I get older. I choose running because it gives me such a great sense of accomplishment.”—Lisa Bartlett

“I run because last year I got Pulmonary embolisms in my lungs and now I want to improve my health and my lungs and spread awareness!”—Jennifer Cole

“Manage stress and support in quitting smoking.”—Aude Carlson (RW+ member)

“Keeps my AFib under control.”—Todd W. Peterson

“I want to be able to walk well into my old age. I have family members who have significantly lost mobility due to their unwillingness to exercise.”—Amy Watkins (RW+ member)

“To control my type 2 diabetes! It works!”—Mike Shamus

For Someone Else

“I started running after witnessing my mom complete a marathon and was overcome with emotion when she finished. I began running the very next year and completed a half marathon with my mom and have been running ever since. Running does so many things for me. It’s my escape, it keeps me centered, helps me to focus, a confidence builder but more importantly allows me to follow in the footsteps of my mom and continue to honor her. I wear a shirt with a picture of her running our last race together so that she’s running with me. I love to run!”—Chantal (RW+ member)

“My daughter.”—Jesse Sturnfield (RW+ member)

“To keep my sanity. Also, I wanna show my kids if they work hard, don’t give up, and find a love for something, they can accomplish anything in life. When they’re tired, stressed, unhappy, just to channel in and get the work done. They’ve been there when I run my marathons and have shown support and encouragement, and I’ll do the same for them. My daughter joined cross country this year and wants to join again next year. My son is wanting to join as well.”—Angela Yawea

“Because my dad ran. I lost him six years ago and clearing his flat I found his medal from Reading Half Marathon in 1988. Holding it inspired me to change. I have my dad’s and my medal from the same race together.”—Stumpy Taylor

For My Mental Health

“To keep my sanity!”—Libby Meyer (RW+ member)

“It’s my therapy.”—Allie Haight

“Running is my ultimate stressbuster! As a middle-aged tech leader, husband, and father to two preteens, running generates all the right endorphins and energy to ensure I’m on top of my game—all of my games!”—Annu Kristipati (RW+ member)

“Cheaper than therapy.”—Louie J. Frucci

“Running helps me dealing with my anxiety, my mental health, but especially this past year with grief. I lost my dad last year and couldn’t work out for two months. I was able to go back to working out thanks to running. Then I signed up for my first marathon. That was on the one-year anniversary of my dad’s passing. Running is my way to feel my dad close and be able to connect with him.”—Fadela (RW+ member)

“Because it has the power to mute my anxiety and self-doubt.”—Nicholas Kuiper

“Running makes me happy. It reduces my stress and anxiety and improves my mental health. It keeps my cardiovascular system strong.”—Suzanne Reisman (RW+ member)

“To stay calm in the chaos.”—Christine Starkweather

To Feel Powerful & Free

“Because it makes me feel powerful and healthy (sometimes only once it’s over).”—Laura (RW+ member)

“To be a real-life video game character.”—Erin Fan (RW+ member)

“Feels like I’m flying. Powerful and free.”—Tenaya Hergert

“I run because I want to be healthier in my 50s than I was in my 30s! And, also, running makes me feel powerful.”—Laura (RW+ member)

“Running gives me a voice.”—Becky Westcott Capazz

“It makes me feel strong and confident, that I can handle everything else in my day.”—Rebecca Eisenbacher (RW+ member)

“To feel free, manage anxiety, accomplish increasing mileage.”—Barbara Saunders (RW+ member)

“Total freedom. Slap your shoes on and be free.”—coach_shasonta

For Connection

“Running makes me feel strong and is my way of meditating. I also love that I’ve been able to connect with people and make so many new friends through running. I enjoy seeing my fitness progression.”—Gisele Carig (RW+ member)

“For my mental health and human connection with friends.”—lizpowers76

“Refreshes the spirit. BTW: I can no longer run; I train and enter races as a walker. Have made many new friends who accept me for just being there.”—Lewis Silverman

“I have many reasons. I connect with my running partners on some runs. I connect with God on others. I find a sense of accomplishment. I like to test what my body can tolerate.”—Tim Thomas (RW+ member)

“When I’m alone, I run to quiet my mind. It is meditative and rejuvenating. I also run to be social. The running community is the best.”—Andy Romanelli (RW+ member)

“Makes 77 feel young and hanging around with younger runners is a whole lot of fun. Not to mention I’ve been loving going for a run for more than 46 years.”—Barbara Ann Morrissey

Because I Love Racing

“I want to improve my 5K time.”—Courtney Danko-Searcy (RW+ member)

“The feeling I have on race day, within the first mile, that all the training is paying off.”—Mark Hopkins (RW+ member)

“My husband and I started running about six years when my son, who was about 12 at the time, had run over 25 5Ks. It took about a year until we were ready for our first 5K. We love running and training together. Running helps me at the end of a long teaching day, and it just feels so good after! We have since ran many 5Ks, some 10Ks, and two half marathons!”—Suzy Wintjen (RW+ member)

“It’s at the end of Ironman.”—Cheryl Turpin

“First, I began to improve my health, then I got hooked. Fifteen years later I am chasing my Six Star Medal.”—Jorge Mitey (RW+ member)

“It’s something I’ve always done since fifth grade. I got into racing 25 years ago. I love the challenge running gives me to constantly improve and get back out there whenever I’ve been injured or ill; and next month will one year since starting my first running streak! Most of all, I run because I love how it makes me feel. It has gotten me through the worst times in my life. Whenever I’m having a bad day, whether I’ve already gone running or not, I go running. It always calms me and makes feel better.”—Elle Escochea Grunert

So That I Can Indulge

“Because I love carbo loading.” —Bud Bjanuar

“I run so I can eat whatever I want and still be in shape!”—Christi Webb (RW+ member)

“I run to eat poutine.”—Robin Bosse

“So I can drink beer!”—Kathy Davis Ward

“Because I am a chocoholic.”—Chantal Englebert

“Faster than walking and I like tacos.”—Shelly Pedergnana

“I run to eat crispy pata.”—Arrin Villareal

To Get Outside

“Fitness and peace of mind. Also, a great way to explore neighborhoods and the outdoors.”—Sue Padden

“The feel of being outside with my dog. Watching him enjoy the run lets me enjoy the run.”—Stan (RW+ member)

“It’s my time with nature. It’s for me to clear my head and think.”—Assa Burton

“Running is my sanctuary. It’s where I can clear my mind, letting go of stress and finding clarity with each step. The rhythm of my feet hitting the ground is a meditative escape, helping me to focus and recharge. Physically, running keeps me in peak condition, building strength and endurance while boosting my overall health. But what I love most is being outside, feeling the fresh air, and soaking in the beauty of nature. Whether it’s a sunlit trail or a quiet street at dawn, running connects me to the world around me in a way nothing else can.”—Adam Scolatti (RW+ member)

Because I Can

“This is my ‘stock’ answer. I do because I can and I can because I do.”—Chip Kidd

“Because I’m not ready to give up yet.”—Martha Rhine (RW+ member)

“Because I was completely disabled, not able to move, stand, walk, talk, or do anything... stuck in the hospital for 13 weeks. When I was discharged and started to walk a little, I needed something to help me get some kind of life back. Running was it.”—Rob Snavely

“Because I’m 70, and not dead yet.”—Michele Glover

“Because I can. One day I won’t be able to and it’s not today.”—Mike Bravo

“Because one day I’ll be old and everything will hurt, and it’s the one thing in my life that lately makes me happy. When you’re running you forget everything. If you’re still thinking of debt, sadness, breakups, you’re not trying hard enough. Every day you have to push yourself.”—Miryam Hernandez

“Because I still can… at 73.”—Joanne Gile Michaelsen

“Forty-five years, why stop now? Never regret going for a run.”—Leslie Kitching

“Sixty-one years old. Been running since I was 15. Because a day without running is like a day without brushing your teeth.”—Sharon Graeber Hall

To Prove it to Myself or Someone Else

“To prove I can. And prove my mind is more powerful than my body.”—Colton James

“Because I still can, and everyone tells me I can’t!”—Lloyd K Leverett

“To tell people I did.”—Chris S. Charlett

“I’m 55. Basketball days are over. The need to compete is still there, and even if that means competing with myself, running allows me to do that.”—Shawn Davis

Because I Hate How I Feel When I Don’t

“I don’t know, but recently I injured my knee, and I was sad I couldn’t run. Thank god, it healed itself. I think running gives me inner peace.”—Jose Murga

“Because I hate the way my brain itches when I don’t.”—Joe Baron

“Because it’s better than smacking my family upside the head from being over stimulated. [It] helps my mental health.”—heatherbrubaker19

“I don’t like it until it’s over.”—Laurie Stinson Fuller

“So that I am tolerable to my husband!”—Dimitra Zakas

“It’s either that or sending my work computer flying out the window like a frisbee on the regular.”—Ayla Amon

“It feels so good when I stop.”—Sarah Wiley

Login to leave a comment

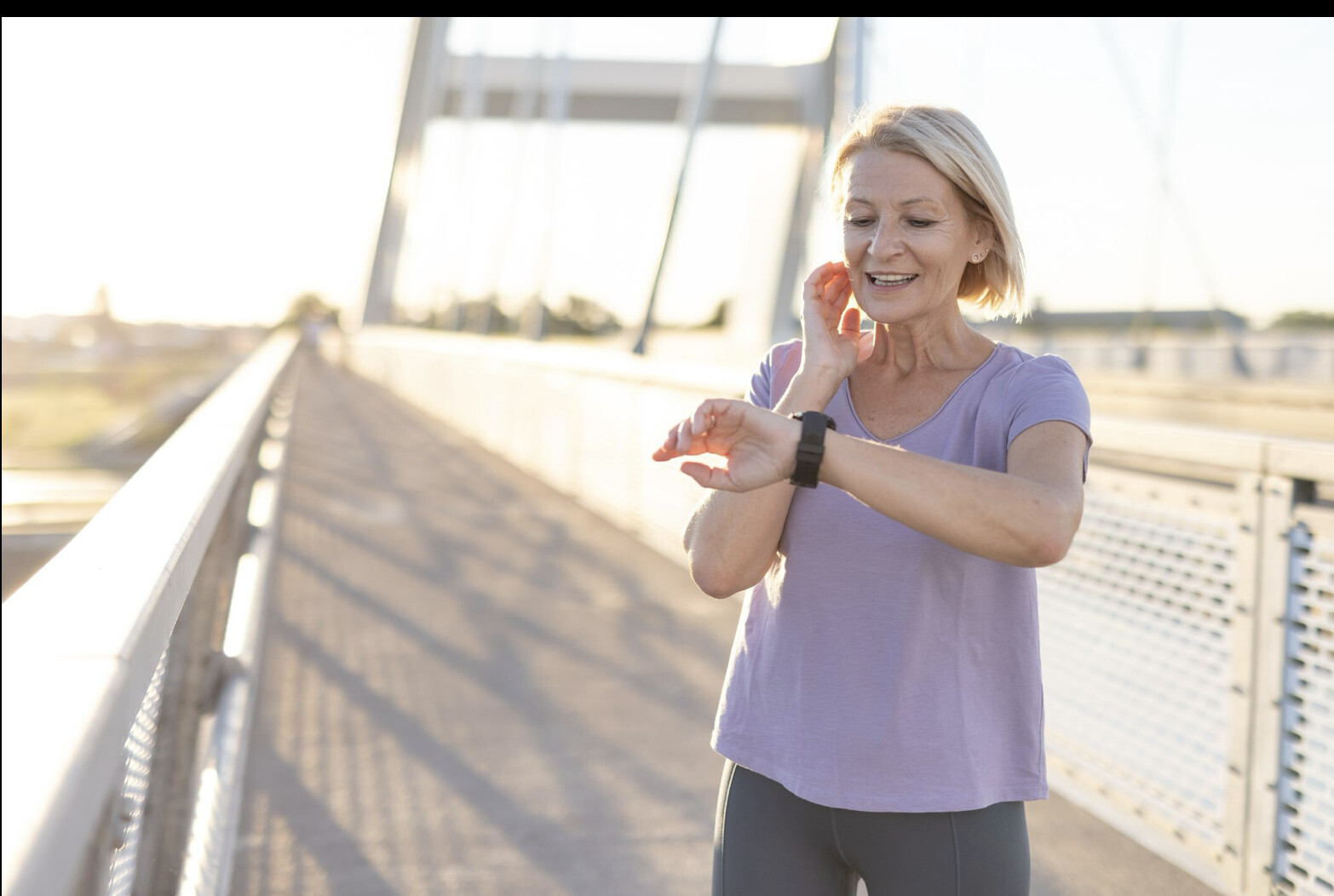

Canadian Boston Marathon age-grouper shares tips for running as we age

Sandy Rutledge began running in his early 60s; he has run the Boston Marathon four times. The Nova Scotian clocked an impressive 3:31:38 at Monday’s 128th running of the famous race, earning him second place for his division and top Canadian in that age bracket.

“It was a slower than normal Boston, with the heat,” Rutledge told Canadian Running after his race. “I backed it off and went a little slower than last year, because I didn’t want to push it and not finish.”

After a decade of running, Rutledge knows what he needs to do to stay competitive, but above all else, he’s looking at his longevity in the sport. “My goal is to run as long as I can,” he says. “In my 60s, I could run seven days a week and over 100 kilometres per week, but I’ve now backed that off to five days a week and lower volume,” he adds.

Rutledge has completed around 19 marathons and several shorter-distance races. And he has stayed relatively injury-free, thanks to a couple of key regimens that anchor his weekly training.

“I take Tuesdays entirely off running, and I do strength training,” he says, acknowledging that the consistency of these sessions has helped his healthy running streak. “I focus on the core in these… as we age, many people tend to develop back issues, and I’m no exception.”

Rutledge also shared that 20 to 30 minutes of daily stretching, often before his runs, has also played a big role in injury prevention.

As his career in real estate has wound down, Rutledge is grateful to running for helping him keep a daily routine, and a sense of purpose. “I wake up at 5 a.m.–I’m a morning person,” he says. “Running has brought me a sense of youth. I have continued doing most of the things I could do when I was younger, and I think running has done that for me.”

Having taken up running later in life than many other runners, Rutledge encourages anyone to give it a try if they’re curious, no matter their age. “I started really slow,” he says. “It began with walking and then adding in some running slowly… maybe a kilometre to start, and building up from there.”

Rutledge has no plans to slow down. “I’ve heard that most people have a 15-year life cycle in the marathon, and I’m 10 years in,” he says. “I’d like to keep running marathons into my 80s, but as long as I can keeping running five days a week, I’ll adjust the speed and the distances of my races, if I need to.”

Rutledge is looking forward to, hopefully, running the Athens Marathon later this year or next.

“That’s where it all began,” he says of the marathon. “I think we all owe it to the running gods to do that one at least once.”

by Running Magazine

Login to leave a comment

Canadian Boston Marathon age-grouper shares tips for running as we age

The Halifax runner took up running in his early 60s, and ran his fourth Boston Marathon on Monday.

Sandy Rutledge began running in his early 60s; he has run the Boston Marathon four times. The Nova Scotian clocked an impressive 3:31:38 at Monday’s 128th running of the famous race, earning him second place for his division and top Canadian in that age bracket.

“It was a slower than normal Boston, with the heat,” Rutledge told Canadian Running after his race. “I backed it off and went a little slower than last year, because I didn’t want to push it and not finish.”

After a decade of running, Rutledge knows what he needs to do to stay competitive, but above all else, he’s looking at his longevity in the sport. “My goal is to run as long as I can,” he says. “In my 60s, I could run seven days a week and over 100 kilometres per week, but I’ve now backed that off to five days a week and lower volume,” he adds.

Rutledge has completed around 19 marathons and several shorter-distance races. And he has stayed relatively injury-free, thanks to a couple of key regimens that anchor his weekly training.

“I take Tuesdays entirely off running, and I do strength training,” he says, acknowledging that the consistency of these sessions has helped his healthy running streak. “I focus on the core in these… as we age, many people tend to develop back issues, and I’m no exception.”

Rutledge also shared that 20 to 30 minutes of daily stretching, often before his runs, has also played a big role in injury prevention.

As his career in real estate has wound down, Rutledge is grateful to running for helping him keep a daily routine, and a sense of purpose. “I wake up at 5 a.m.–I’m a morning person,” he says. “Running has brought me a sense of youth. I have continued doing most of the things I could do when I was younger, and I think running has done that for me.”

Having taken up running later in life than many other runners, Rutledge encourages anyone to give it a try if they’re curious, no matter their age. “I started really slow,” he says. “It began with walking and then adding in some running slowly… maybe a kilometre to start, and building up from there.”

Rutledge has no plans to slow down. “I’ve heard that most people have a 15-year life cycle in the marathon, and I’m 10 years in,” he says. “I’d like to keep running marathons into my 80s, but as long as I can keeping running five days a week, I’ll adjust the speed and the distances of my races, if I need to.”

Rutledge is looking forward to, hopefully, running the Athens Marathon later this year or next.

“That’s where it all began,” he says of the marathon. “I think we all owe it to the running gods to do that one at least once.”

by Claire Haines

Login to leave a comment

Boston Marathon

Among the nation’s oldest athletic clubs, the B.A.A. was established in 1887, and, in 1896, more than half of the U.S. Olympic Team at the first modern games was composed of B.A.A. club members. The Olympic Games provided the inspiration for the first Boston Marathon, which culminated the B.A.A. Games on April 19, 1897. John J. McDermott emerged from a...

more...Take a Sneak Peek into 'Born to Run 2'

Thirteen years after the publication of Christopher McDougall's popular book, Born to Run, the author teams up with renowned running coach Eric Orton for Born to Run 2: The Ultimate Training Guide, a fully illustrated, practical guide to running for everyone from amateurs to seasoned runners, about how to eat, race, and train like the world's best. Born to Run 2 will be available on December 6, 2022, but you can read this excerpt from the book.

Chapter 8: Form - The Art of Easy

Eric promised he could teach running form in ten minutes. If I had to estimate, I'd guess he was miscalculating by a factor of at least 7,000 percent, so I subjected his proposition to lab testing and gave it a try myself:

I hit Pause and checked my watch. Then I tried it again. Each time, I found Eric's estimate to be wildly exaggerated. It wasn't even close to ten minutes. More like five.

One song. One wall. Three hundred seconds. If someone had only shared this secret with Karma Park, it could have saved her a world of misery.

Karma was such a disaster, the Navy honestly couldn't tell if she was a terrible runner or a terrific actor. How she even made it into boot camp was a mystery.

The strange thing was, running was her only weakness. Chuck her out of a boat at sea? No problem. Pull-ups, push-ups, crunches? Piece of cake. Karma was a competitive swimmer and varsity wrestler growing up, so two-hour workouts were in her blood. But ask her to run a mile and a half? In under thirteen minutes? Not a chance. Over and over she tried, and every time she ended up walking, grabbing her ribs from stitches and wincing from aches in her legs.

"I'm pretty sure the recruiter fudged the numbers on my Physical Readiness Test so she could get me in," Karma believes. "I finished the run and thought, Oh crap, I'm a minute too slow, and she's like, 'No, no, you're good.' "

When Karma got to basic training, she gritted her teeth and did her best. The Navy was her ticket to a dream life, so there was no way she was giving up. Karma was twenty-five at the time, with a wife in law school and hopes of becoming a surgeon. The surest path toward financing their future was a career in the military. Besides, she had a debt to pay back. Karma came to America from South Korea at age eleven, and while, yeah, maybe Alabama wasn't the most welcoming place for a foreign kid with budding gender issues, Karma was still deeply grateful for the life her family was able to create there.

"I really wanted to serve this country," she says. "But in boot camp I was in and out of sick bay all the time." Karma chanted the drill instructors' mottoes to herself-Pain is only skin deep! Heel to toe! Heel to toe!-but the harder she pushed, the more she broke down. "At first maybe they were checking that I wasn't dogging it," Karma recalls. "I can see how I would be suspected because I feel that other recruits faked it to get out of running, but I was in so much pain, they knew something else was going on."

Finally, Navy doctors diagnosed Karma with chronic hip displacement. She was ordered to report to the long-term sick bay, where she'd be stuck for as long as it took-a month, six months, a year-for her to either heal or quit. Those were her options: get better, get faster or get out.

Karma was crushed, but privately vindicated: ever since she was young and her mom would sign the whole family up for local 5Ks as a way of assimilating into their new home, Karma knew she couldn't run. "My dad and I would walk at the back of the pack, and I thought, This is the most ridiculous thing ever. We have cars and bikes, why are we running? I was really fit in all the other aspects of PE, but with running, I tried and tried and never got any better."

Back in civilian life, Karma struggled. She put her own education on hold and began managing a Subway so her wife could finish law school. She began putting on weight, but when she tried to exercise, her old leg injuries flared up and she finally discovered the real cause of her pain was rheumatoid arthritis. The medication made her lethargic and bloated, and her body ached so badly she needed a cane to walk.

Karma was in a bad spiral that nothing could stop. Except her wife's lover.

"My wife had an affair with a guy who was really fit," Karma says. "When I confronted her, she told me I was fat. That hit me really hard." So hard that after she and her wife separated, Karma decided to punish herself with the thing she detested most. "I decided to drown my emotional pain by subjecting myself to physical pain," she says. "When I left the Navy I swore off running-I hate it hate it hate it, never running again. This time, I decided to run myself ragged into an early grave. I hated myself and hated running, so this is what I'll do."

For once, Karma's injuries came to the rescue. Her legs seized up before her heart, and while she was searching for a new way to beat on herself, she had the enormous good luck to meet Sheridan. With that amazing woman by her side, parts of Karma that she hadn't even realized were hurting began to heal. For the first time, she had the confidence and support to face her gender identity and begin transitioning to the self that had always been buried.

She also resolved, once again, to get back into shape.

If you're keeping score at home, by now Karma has struck out three times as a runner. Over the years, I've heard a lot of stories like this from busted ex-runners-and lived one myself-but this is the first instance where I thought, okay, maybe it's time for the mercy rule to kick in and let it go for good. But against those odds, Karma stepped up again. When Sheridan gave birth to their first son, Karma set her jaw and decided their baby wasn't going to grow up with a parent hobbled with a cane or gone before their time.

"That's how I began my journey into learning how to run properly," she says.

This go-round, Karma attacked the problem from a different angle: What if her brain was the problem and not her body? Karma is a math whiz and comes from a medical family, so she was a little annoyed at herself for not realizing sooner that if your equation keeps giving you the wrong result, adding the same numbers isn't going to help. Rather than running harder, she thought, maybe there was a way she could run smarter.

Her eureka! moment occurred soon after, when she noticed that her legs hurt more on downhills than ups. That's when it hit her: What if she treated the entire planet like a hill? Get up on her forefoot, in other words, instead of heel-toe, heel-toeing it like she'd always been told.

"When I mentioned this to a friend, she immediately said, 'Haven't you read Born to Run? That's what it's all about.'"

Karma picked up a copy, and there, on page 181, she found the role model who would change her life. Not Ann Trason, the courageous science teacher who nearly outran a team of Raramuri runners in the Leadville Trail 100. Not Scott Jurek, the gracious and unbreakable hero who rose from a rough Minnesota childhood to become the greatest ultrarunner of all time. Karma didn't even see herself in Jenn Shelton, that patron saint of human fireballs, or Caballo Blanco, the lovelorn loner who used running to heal a broken heart.

Nope. When Karma looked into the mirror, grinning back at her was Barefoot Ted.

I'm not happy about this now, but when Caballo Blanco and I first met Ted McDonald, we were ready to Rock-Paper-Scissors over who was going to clunk him on the head and chuck him into the canyon. Ted likes to say "My life is a controlled explosion," which only confirmed my conviction that he has no idea what "control" means.

I was slow to see what Jenn and Billy Bonehead and Manuel Luna liked about Ted. It took a few clashes before I finally got it, including a toe-to-toe shouting match in the middle of Death Valley, where I threatened to leave Ted by the side of the road to die while he was yelling in my face, "I don't care how big you are! I'll fight you!"-at the very moment, by the way, when we were supposed to be crewing for Luis Escobar in the Badwater Ultramarathon.

But I couldn't miss the fact that lots of other people really enjoy him. Ted is a lot on a slow day, but he's also a huge-hearted friend and his own kind of genius. When I sent word to Ted that a group of my Amish ultrarunning buddies were traveling through Seattle en route to a Ragnar Relay, he immediately threw open the doors of his Luna Sandal shop and made them at home in an improvised bunkhouse. Nearly every year, Ted travels back down to the Copper Canyons and hands a wad of cash to Manuel Luna, the Raramuri artisan who taught him how to make huaraches. Not because they're partners; because they're friends.

Still, it was gratifying to see that Luis had as much steam shooting out of his ears as I did after we invited Ted to join us in Colton for our photo shoot. For forty-eight hours we couldn't get a yes or no out of the guy, which would have been fine if he'd just stayed silent as well. Instead, Luis and I kept getting cryptic little teaser texts, like digital art smiley faces that dissolved from our phones a few seconds after appearing. It felt less like waiting for a friend to show up (or not) and more like being stalked by the Zodiac Killer.

Then lo and behold, an Amtrak train pulls into San Bernardino station and out pops Barefoot Ted, a big Santa Claus backpack full of sandal-making supplies over his shoulder. He'd spent six hours getting there, and immediately began hand-crafting a gorgeous pair of custom sandals for each of our volunteer models. While his hands were busy, so was his mouth: Ted cut loose with a thirty-minute spoken-word performance that left us all slack-jawed in astonishment as he prattled on, fluently and kind of brilliantly, about everything that had been rattling around inside his skull while he was captive on the train. ("Turning everything you see into food is a superpower. Do you have it?" is the only line I remember.) Soon after finishing a dozen sandals he was gone, grabbing a lift back to Santa Barbara that same night because, unbeknown to us, he'd had a pressing commitment there all along. What a guy.

As a runner, Ted was a true revolutionary. He was so far ahead of the pack when it came to minimalism, the rest of the country took years to catch up. Not that he didn't make a compelling argument from the start. It's just that in typical Ted fashion, the story took a direction only a man who calls himself The Monkey would follow.

If you recall, Ted only began running in the first place because he dreamed of becoming America's Anachronistic Ironman. Which meant, for reasons known only to Ted, he wanted to spend his fortieth birthday completing a full triathlon (2.4-mile ocean swim, 112-mile bike ride and 26.2-mile run) but only using gear from the 1890s. If Ted has one quality greater than his raw athleticism it's his absolutely bulletproof self-confidence, so when he found he could handle the swimming and cycling but not the running, the problem couldn't be his body: it had to be the running.

Close: it was actually the running shoes. The first time Ted ran barefoot, his planetary axis shifted. "I was totally amazed at how enjoyable it was," Ted says. "The shoes would cause so much pain, and as soon as I took them off, it was like my feet were fish jumping back into water after being held captive."

On a barefooter's blog, he found the Three Great Truths:

Change the way you run That was the opposite of everything Ted had ever been told about running, but everything Ted had ever been told about running wasn't working. Besides, it immediately made sense. No decent basketball player just heaves the ball in the air and hopes for the best. No serious tennis player slashes their racket around like a club. Ted had spent a few years as a teacher in Japan, and he knew that sushi chefs and martial artists spend years perfecting the basic steps of their craft. In the world of movement, form and technique reign supreme.

Ted didn't know any barefoot runners in person, only online, so he set off on this quest for reinvention on his own. He found himself in the same predicament as a Czech soldier he'd heard about who, during the Second World War, spent his long nights on guard duty dreaming of Olympic glory. Rather than stand and shiver, the soldier began running in place, lifting his knees high to clear the snow and, to avoid being heard, landing as silently as possible in his heavy boots.

Back home after the war, the soldier replaced slippery snow with wet laundry: he washed his clothes by running on top of them in a bathtub full of soap and water. (Get a load of that, Mr. 100 Up: one sloppy stride in a sudsy tub and you're not starting over, you're heading to the emergency room.)

Those weird home experiments paid off spectacularly. Coached only by his own ingenuity, Emil Zatopek pulled off the most stunning track performance in Olympic history: at the 1952 Games, he won gold in all three distance events, including the first marathon he ever attempted.

Despite how fast he ran, Emil took a ton of crap about how awful he looked. Upstairs, Zatopek was a horror. He'd get this grimace on his face, one sportswriter said, "as if he'd just been stabbed through the heart." Zatopek's head lolled around and his hands clawed his own chest like he was birthing an alien baby through his rib cage. But what sportswriters missed was that below the waist, Zatopek was a machine: rhythmic, precise, impeccable.

Ted never did get around to his Anachronistic Ironman-not yet, at least-but otherwise, he was unstoppable. Once he realized that running was a skill to be mastered and not a punishment to be endured, he became a Monkey on a mission.

Before long, he'd ripped out a marathon quick enough to qualify for Boston, and then ran Boston quick enough to qualify for the next one, and from there it was onward and literally upward, as he shifted from long roads to high-mountain ultramarathons.

But what Karma envied most wasn't Ted's remarkable twenty-five-hour finish at the Leadville Trail 100, or his out-of-left-field world record for skateboarding (242 miles in twenty-four hours). She didn't care if she ever ran as fast as Ted. She just wanted to be as healthy. She wanted to follow his footsteps from Hurt Ted to Happy Ted.

"I made a conscious decision to fully embrace forefoot running," Karma says.

Maybe embrace isn't the right word. Since May 3, 2014, Karma hasn't missed a single day of running. Every evening, no matter what kind of storm is blowing through Birmingham, Alabama, no matter if she's fighting a cold or dealing with craziness at the medical office she manages, Karma pulls on her sandals and heads out the door.

Her eight-year-and-counting streak began in true Barefoot Ted fashion: bizarrely. Less than a year after changing her form, the woman who swore she'd never run again was bringing home her first marathon medal. Gone was the cane, forgotten was the specter of crippling arthritis. By changing the way she moved, Karma discovered she could change the way she felt. She soon ramped up from a marathon to a 50K, and that's when things took off. The day after that first ultramarathon, Karma decided to test her soreness by jogging an easy two miles. She was surprised to find her legs actually felt better after that run, so she went out again the next day and the next and thus a streak was born.

To maintain her daily running streak, Karma logs at least one mile a day, but that's just her baseline. During her first year of streaking she also tackled three ultramarathons, and then began creating streaks within her streak: she ran five miles a day for a full year, seven miles a day for ten months, and three miles a day for 1,300 days. Despite all these clicks on her odometer, Karma still felt she needed to borrow one more hack from Barefoot Ted: as a reminder to remain smooth and light, she always runs in a pair of his Lunas.

Karma had never actually met Ted in person until the day he hopped off the train in San Bernardino and blew into our photo shoot like a grinning bald tornado. Ted is usually quick on his feet, but when he came eye to eye with Karma, it took him a few beats to get his bearings.

The person who'd reached out to Ted years ago had never felt at home in her body and was facing two frightening transformations. The Karma in front of Ted today had made it through to the other end. In the past, Karma had looked to Ted for hope and guidance. Now, she deserved something very different. Ted understood, and delivered.

"If you have any questions, ask Karma," Ted said, as he addressed the circle of very experienced and accomplished ultrarunners hanging on his every word about the art of minimalist running. "She knows as much as I do."

This is an excerpt from Born to Run 2: The Ultimate Training Guide by Christopher McDougall and Eric Orton, available on December 6, 2022 by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright 2022 by Christopher McDougall and Eric Orton.

by Trail Runner Magazine

Login to leave a comment

Here’s What Happens to Your Body (and Mind) When You Run Every Day

From your muscles to your mental state, you gain a plethora of benefits from daily runs.

Are you in the midst of a streak and feeling like a different person than when you started? That’s because you are. Running every day triggers a variety of mental and physical benefits, all of which can help improve your athletic performance and make you a healthier human.

“If running or exercise were a pill, it would be the most widely prescribed drug in the world for all of the benefits for your health that it has,” Todd Buckingham, Ph.D., chief exercise physiologist at The Bucking Fit Life, a wellness coaching company and community, tells Runner’s World. “Exercise really is medicine, and running is medicine,” he says.

If you’re wondering about the effects of your daily dose, here are a list of all the benefits of running every day. Let it fuel you with motivation to keep running toward your run streak goal.

Your Heart Gets Stronger and More Efficient

As a new runner, those first couple of runs can be brutal. Your breathing is labored, and your heart feels like it’s pounding against your chest. Meanwhile, your legs are barely moving. But, a couple of weeks into your training, breathing becomes easier, and that heart-pounding sensation lessens as your feet pick up the pace.

If you’re wearing a fitness tracker, you may even notice a dip in your heart rate while you hit the same paces. “The heart is a muscle, just like every other muscle in the body. The more that you train it, the stronger it’s going to get,” Buckingham says.

He explains that running every day strengthens cardiac muscle tissue and causes the heart’s left ventricle, the chamber that forces oxygenated blood into the aorta (the artery that carries blood from the heart to the body), to increase in size. “There’s more space in that left ventricle to fill up with blood,” he says. “So not only is there more blood to be pumped out, but the heart is also stronger, so it can pump more blood out with each beat.”

As a result, your heart doesn’t have to work as hard to deliver oxygenated blood to your muscles. This is a boon for your daily runs and your overall heart health.

You Gain Muscle Mass and Strength

When you pound the pavement, treadmill, or trail day after day, your muscles—specifically, the glutes, quadriceps, hamstrings, soleus, and gastrocnemius (those last two are your calf muscles)—respond to the stimulus being imposed upon them.

“The muscle is damaged, and that means that the body has to repair the damaged muscles so that the same run doesn’t have the same effect that it did last time,” Buckingham says. Essentially, the muscles are re-built bigger and stronger. “It’s a lot like lifting weights,” he says.

But, unless your workouts consist of sprint intervals paired with resistance training, don’t expect to bulk up. Running long distances (even just a mile or more) at a sustainable pace primarily engages type I muscle fibers, which are good at resisting fatigue but are small in size. (Type II fibers, which are quick to fatigue but generate more force and power, are generally responsible for visible muscle growth.)

“You might see a little bit of increase in [muscle] size with distance running, but it’s not going to be as pronounced. Type I muscle fibers can get bigger, but not to the same extent as those type II fibers,” Buckingham explains.

Your Connective Tissue (Slowly) Adapts

Your body’s connective tissue, namely the tendons and ligaments, will also adapt to withstand the daily stress of running—just not as quickly as your muscle tissue. “The reason for this is because tendons and ligaments don’t have the same amount of blood flow that the muscles do, so it takes them longer to adapt,” Buckingham says.

While your muscles may begin to change a couple of weeks into a running streak, it could take three to four months for your tendons and ligaments to catch up, he says.

To prevent overuse injuries, it’s best to begin a streak with a conservative goal (a mile a day is a good place to start, says Buckingham) and gradually build upon that foundation. The general rule of thumb is to increase your mileage by no more than 10% each week, but Buckingham notes that this can vary depending on the athlete, their experience, and their mileage.

Avoiding long breaks is helpful for your connective tissues, says Alison Staples, coach at &Running in Howard County, Maryland. “Tendons need to be loaded consistently to learn how to accept the impact of running,” she says. “Running sporadically often leads to injury because we haven’t practiced loading our tendons enough before tacking on mileage.”

Your Nervous System Becomes Fine-Tuned

Buckingham compares the nervous system to a maze. “The first time you do it, you’re going to take a lot of wrong turns and end up doing extra work,” he says. But, over time, you learn the most direct path from point A to point B.

Similarly, the first few times you go out for a run, your neuromuscular connections will fire inefficiently, as one nerve fiber connects to multiple muscle fibers. Muscle fibers that don’t need to contract will be stimulated, resulting in wasted energy. However, with consistent running, your nervous system eventually adapts and learns the optimal route so everything works more efficiently.

Research backs this up, too, saying that consistent running trains your central nervous system to adjust to and get more efficient at the commands of running.

“The more you run, the more efficient you’re going to become [at running] because you're teaching the body which muscle fibers should be firing and which shouldn’t,” Buckingham says.

You Feel Mentally Sharper

Running boosts circulation, increasing blood flow to the brain and delivering the nutrients you need to think and function. But exercise has also been shown to promote the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein important to brain function and memory.

“BDNF actually increases the brain’s ability to form new synapses, or connections, in the brain,” Buckingham says. “This helps with learning and memory. It makes it easier to absorb information and form long-term memories. The more BDNF that somebody has, the more the memory improves in function and capacity.”

According to Buckingham, the effects of increased BDNF are cumulative, but you may feel mentally sharper and more alert after just a few days of running.

Your Mood and Motivation Improve

BDNF can also help mitigate stress. “It doesn’t decrease stress hormones, but it does decrease the number of stress receptors,” Buckingham says. “And this could minimize the effect of those stress hormones in the brain.”

Add that to an exercise-induced endorphin release, and you have a recipe for an improved mood. In fact, research shows just 10 minutes of running can enhance your happiness.

“I am currently running the #RWRunStreak myself, and based on my own experience, running a mile every day has been a huge boost in my mood and motivation,” Staples says. “My one mile a day is my own form of non-negotiable self-care… And by doing this run streak, I’m certainly more relaxed and motivated to get my run in every day.”

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

The craziest active streaks in running

On Jan. 29, New Zealand’s Nick Willis ran another sub-4 minute mile at the NYC Millrose Games for the 20th consecutive year. This achievement is something only a few runners have come close to, which has sparked us to find the craziest active running streaks.

Nick Willis – 20 years of sub-4 minute miles

Willis first ran sub-4 during his undergrad at the University of Michigan in 2003 (3:58.15). At last weekend’s Millrose Games, Willis broke four minutes for the 63rd time in his career (3:59.71), which marked the 20th consecutive year he has run sub-4 miles. Willis is New Zealand’s only two-time Olympic medallist in the 1,500 metres, winning a silver medal in Beijing and bronze in Rio. In 2020, Willis passed his countryman, Sir John Walker, who previously held the consecutive sub-4 mile record of 18 years.

Simon Laporte – 46 years of running every day

At 46 years, the Notre-Dame des Prairies, Que. runner holds the longest active run streak in Canada. Laporte began his streak on Nov. 27, 1975, and hasn’t missed a day since. The 70-year-old run streaker has no plans to stop anytime soon, and he is planning for his streak to reach 50 in 2025. The longest active streak in the world is held by Jon Sutherland of Utah. Sutherland’s run streak of 52.7 years recently passed the legendary record set by Ron Hill (52.1) last year.

Streak Runners International (SRI) says for runs to qualify as a streak, they must cover at least one mile (1.61 kilometres) each day. The run may occur on the road, track, trails, or treadmill, but a minimum of one mile must be completed.

Lois Bastien – 41.8 years of running every day

Bastien holds the longest-standing women’s run streak record, at 42 years. She is now 79 and still runs every day in her home state of Florida.

Ben Beach – 54 consecutive Boston Marathons

Although Beach does not have the record for most Boston Marathon finishes (58), the 72-year-old marathoner does have the record for most consecutive Boston Marathons (54). Beach ran his first Boston in 1967 when he was 18. This year, Beach completed his 54th consecutive Boston Marathon, finishing in 5:47:27.

Allyson Felix – Five straight Olympic Games with a medal in track and field

U.S. sprinter Allyson Felix is one of the greatest female Olympians ever. She has not only represented her country at five straight Olympic Games, but she has also medalled at all of them (seven gold, three silver and one bronze) – a feat that no other female athlete has accomplished in track and field. Although Felix intended that Tokyo would be her last Olympics, her streak will remain active until Paris 2024, where Jamaican sprinter Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce will get the chance to equal her at five consecutive Olympics with a medal.

Karl Meltzer – a 20-year streak of winning a 100-mile race

Meltzer, 54, has been on the elite ultramarathon scene for more than 20 years. With his most recent win this year at the Beast of the East 100-miler, he has won a 100-miler for 20 consecutive years, bringing his career total to 45 wins over 100 miles. This is an unprecedented number, and the only person who can top it (for now, at least) is Meltzer himself.

by Running Magazine

Login to leave a comment

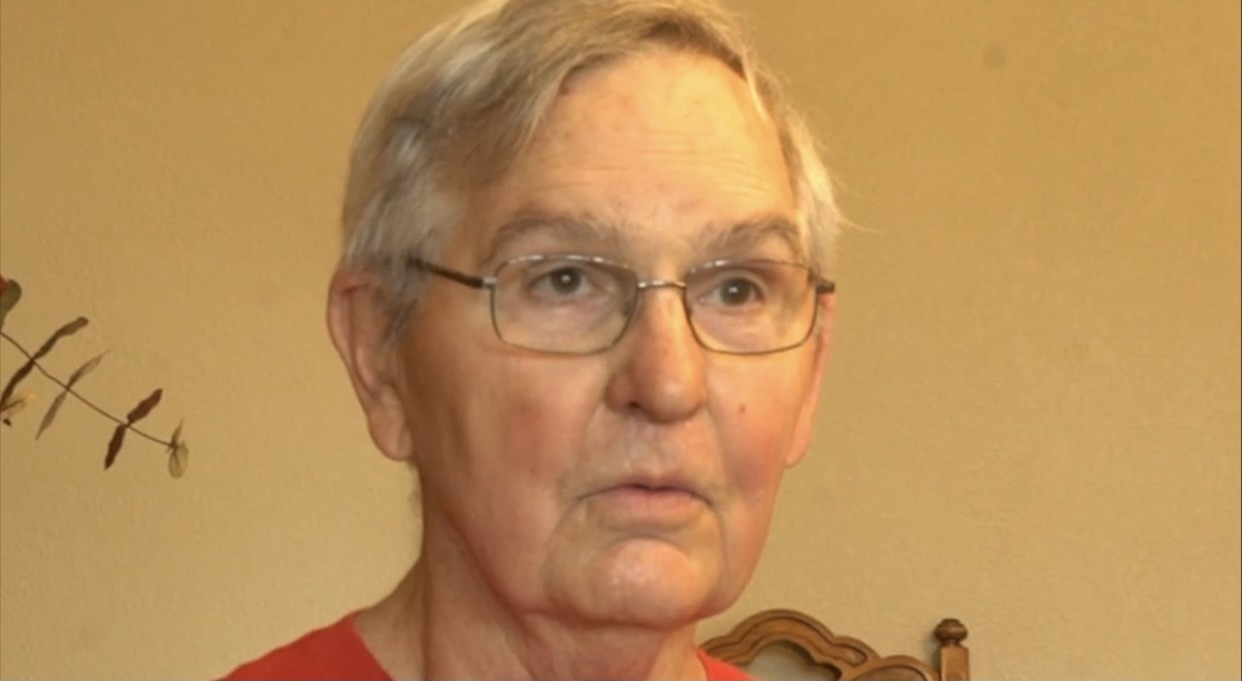

Bill Anderson ran at least one mile every day for over 44 years has passed away

Bill Anderson has passed away. He has been fighting prostate cancer since 1999.

"He was a fighter," says his brother Bob Anderson (director of My Best Runs). "I know he would be proud to know that he was able to run a mile just ten days before his death. R.I.P. The world will miss you."

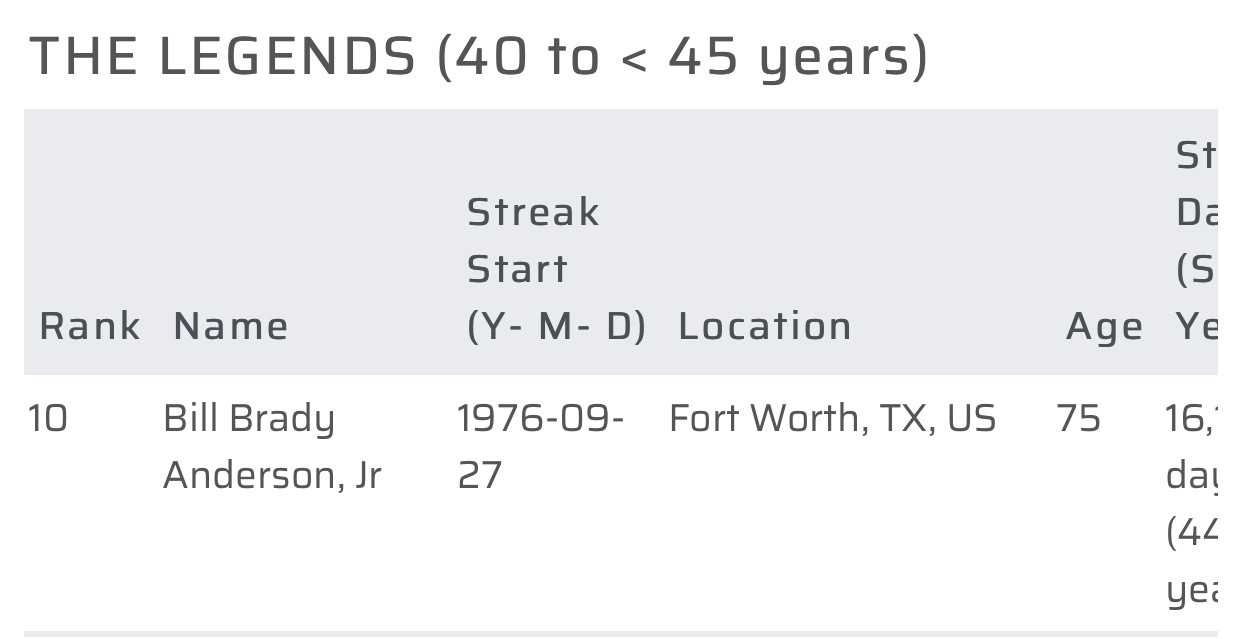

In 2018 he shared his secrets with MBR. Bill Anderson (72) started his running streak on September 27, 1976 in Fort Worth Texas. He has run at least one mile everyday since then. He is currently number ten on the Official USA Active Running Streak List.

"My brother Bill has never been injured," says Bob Anderson. Asked why he has never been injured he says, "Shoes are the hidden secret to avoid injuries. I make sure they are always fresh," Bill says.

"Secondly I always run within my capacity. Thirdly, I make sure I enjoy every run. Fourth, I know myself well enough to anticipate a potential issue before it happens."

His daughter (Barb) posted this on FB on December 23, 2020.

“The Streak has ended…

My dad did not do something yesterday that he’d done the past 16,000 + days – he did not go run at least one mile.

On September 27, 1976, he went for a run…I was 2 years old. He continued that for 44 years, 2 months and 25 days and ended his running career with the 10th longest documented running streak in the United States.

The rules? At least one mile, outside, in running shoes.

At some point the streak became another family member that we’ve all formed a complicated relationship with, especially my mom, who has worried about him, followed him in the car in the hail or after a little too much to drink, cursed the inconvenience of the “damn streak” on occasion and supported him every day.

When I was in high school, I started running with him. The first time I ran four miles, I was with my dad and we had about a third of a mile to go, all uphill. I was ready to quit when he calmly said, “At this point it’s really just a matter of one’s character.” I didn’t stop.

I’ve run with him numerous distances, in numerous locations, sometimes in formal races and sometime just around the hood. But my dad’s run in every state, dozens of countries and incredible ranges of temperatures and weather conditions, juggling time zones, international date lines, snow, wind, rain, prostate cancer surgeries, bladder cancer, Parkinson’s, nine chemo cycles, a ruptured appendix and age.

On Monday the 21st my mom practically pushed him out the front door and followed him in the car one last time, this time for concern of his mental acuity.

I ran with him on Tuesday the 22nd, not knowing but somehow feeling the final curtain call. We reminisced about our most memorable runs together – like the one time, a very low-to-the-ground bulldog joined us from nowhere and ran at least a mile right between us. We both thought that dog would go into cardiac arrest. At some point he bailed on us but when we got back to the house, we jumped in the car to try and find him because we were convinced that he was dead, lost or both. We never did find him.

On Wednesday the 23rd after being rushed to the hospital, he announced with dignity, strength and no regret, that the streak was over.

He made the right decision. But I can’t help feeling like we lost a family member yesterday.

My dad has always been my hero. Dad, today I went for a run and even though I cried through half of it, I ran with new purpose and I crushed it. I love you.”

Click on link (the title) to listen to Bill talk about his streak.

Login to leave a comment

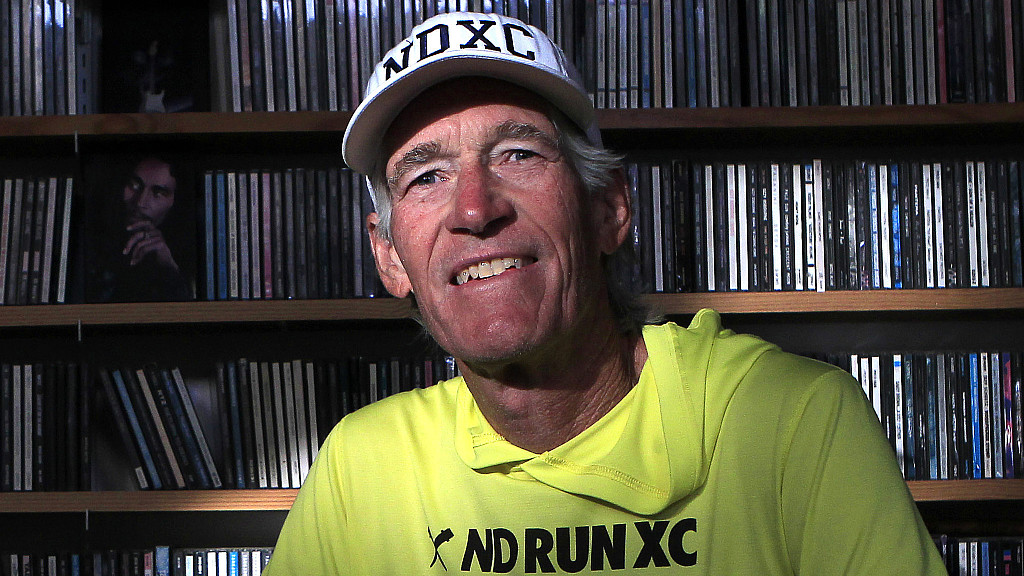

75 year-old, Jim Pearson has run at least a mile every day for 50 years and he won´t stop doing it

The lead story in The Seattle Times on Feb. 15, 1970, was headlined, “Nixon bans war toxins.” In sports, the banner trumpeted that the Seattle Pilots were dropping the price of their field box seats for 1970 from $6 to $4.50 – though it became a moot point when the Pilots moved to Milwaukee six weeks later.

One other event that day, however, went unnoted in the news. Jim Pearson, the cross-country coach at Ferndale High School, didn’t go for a run.

The world has changed in myriad ways in the ensuing half-century, but there has been one constant. Through rainstorms and blizzards, floods and Nor’westers, surgeries and illness, and now through a worldwide pandemic, Pearson has run every day since.

That’s 50 years, 40 days and counting for the 75-year-old Pearson, now hunkered down in Marysville. Hunkered, that is, except for his daily peregrination in Adidas, a welcome diversion in our shelter-in-place existence.

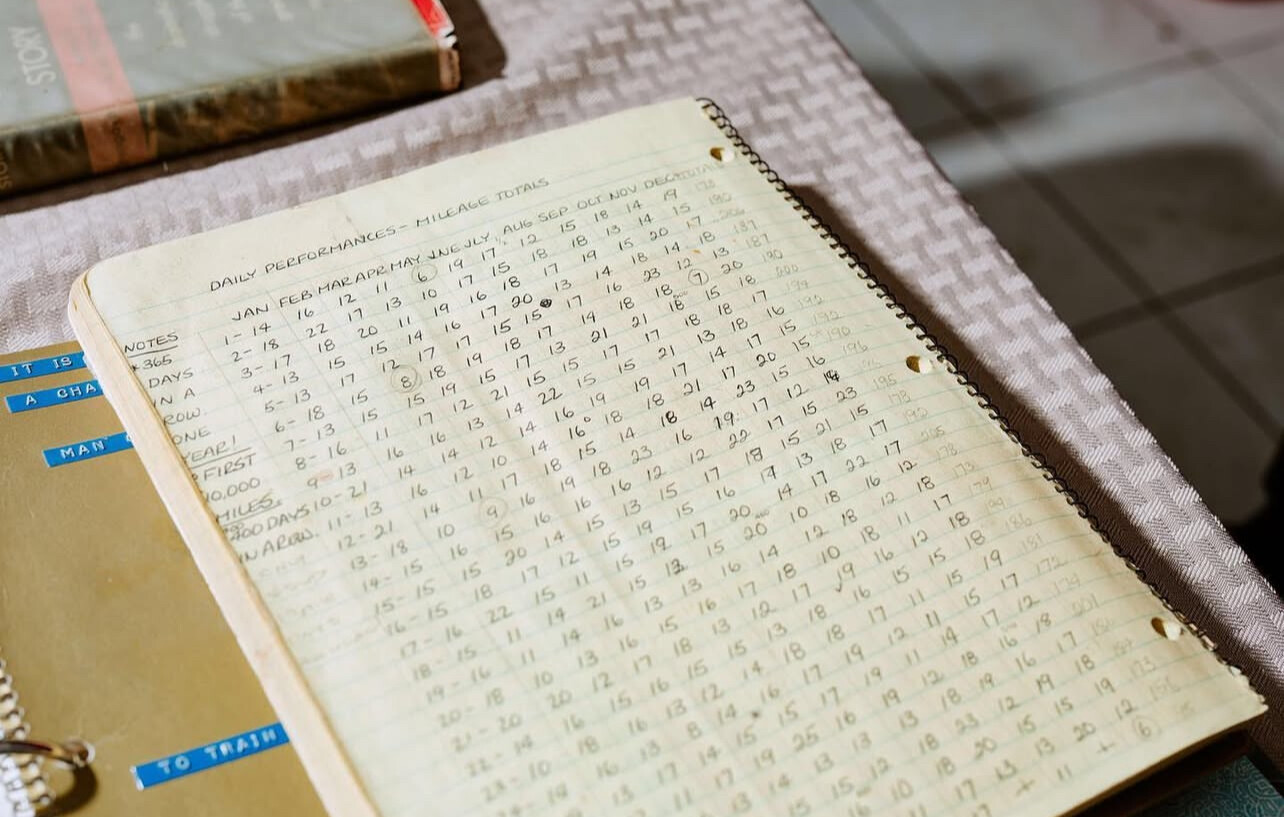

Put another way, it’s 18,304 straight days of running at least a mile, which is the minimum requirement for an officially recognized running streak (but Pearson, a former national record-holder at 50 miles, almost never runs that short a distance). Put yet another way, it’s 176,926 total miles, up to and including Pearson’s 2½-mile run on Friday.

It’s the second-longest active streak in the country, 266 days behind the 18,570 of 69-year-old Jon Sutherland of West Hills, Calif. Pearson says with mock indignation, “Every day I run, and I haven’t gained a day on him.”

But everyone else in the country, and probably the world, is behind these two ironmen, as compiled by the Streak Runners International Inc. and United States Running Streak Association, Inc. Their registry is all based on the honor system, but Pearson has 50 years-plus of log books and running diaries to back him up.

“I’ve always said the first 100 days are the hardest on this streak stuff,’’ said Pearson. “People say, ‘Oh, you’re amazing.’ No, I’m not. People who can do one year, that’s amazing. How do you run every day for a year? But once you’ve done that, it’s something you just do.”

Pearson is duly grateful that running is an activity that can be maintained through the coronavirus quarantining – with proper social distancing, of course. It’s just one of numerous challenges Pearson has faced to keep his streak alive since his summer coach with the Everett Elks track team, Keith Gilbertson Sr., implored Pearson to get more consistent with his running.

Running became a way of life in the Pearson family. All three of his children, two boys and a girl, put together run streaks that stretched into multiple years. Barbie, his wife, didn’t run, but she told Jim when they were married, “I won’t interfere with your running.”

by Larry Stone

Login to leave a comment

Tim Osberg running streak is approaching 33 years and he has no plans of stopping soon

Login to leave a comment

Bill Anderson's secrets for Running Injury Free for Over 41 years

Bill Anderson (72) started his running streak on September 27, 1976 in Fort Worth Texas. He has run at least one mile everyday since then. He is currently number nine on the Official USA Active Running Streak List.

"My brother Bill has never been injured," says Bob Anderson. Asked why he has never been injured he says, "Shoes are the hidden secret to avoid injuries. I make sure they are always fresh," Bill says.

"Secondly I always run within my capacity. Thirdly, I make sure I enjoy every run. Fourth, I know myself well enough to anticipate a potential issue before it happens."

Training

Login to leave a comment

What is the World's Longest Running Streak?

Login to leave a comment

Jon Sutherland Started His Running Streak in 1969

Login to leave a comment