Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #Kristian Blummenfelt

Today's Running News

IRONMAN Kona 2024: Kristian Blummenfelt targets World Championship RECORD

There is one triathlon summit Kristian Blummenfelt has yet to scale, and this Saturday (October 26) in Hawaii he bids to end the wait.

Kona 2024 sees the professional men return to the Big Island for the first time in two years to fight out the 2024 IRONMAN World Championship, with a stellar field set to line up.

Blummenfelt, third behind compatriot Gustav Iden in 2022, will likely start the favourite to top the podium this time, with his friend and rival still rebuilding from a 2023 beset by injury and personal tragedy.

It will not be a cakewalk though (when is Kona ever a cakewalk), with defending champion Sam Laidlow, two-time king Patrick Lange and giant Dane Magnus Ditlev among those also set to toe the line.

Blummenfelt has already shown he is Ironman-ready for this test – remember how he aced Frankfurt less than two weeks after racing the Mixed Relay at the Paris 2024 Olympics? A blistering 7:27:21 – topped off by a 2:32:29 marathon – shocked many, including the man himself.

Blummenfelt Kona prep

Since then Blummenfelt and Iden have been preparing for Kona in the familiar surroundings of Flagstaff, Arizona. And according to Kristian’s coach Olav Aleksander Bu, things are going well.

The Norwegians are always brutally honest about where they are at heading into a race, and always fiercely ambitious with their goals. This time is clearly no different, Blummenfelt is aiming not just to win…

Bu told TRI247: “Prep has been good. It helps that it is a couple of weeks later this year. Race day will have to show what he is capable of ? The weather plays a big role, but a record is always a good target.”

The current Kona record remember was set just two short years ago, in the last Pro Men championship race on the Big Island. That was Iden with a spectacular 7:40:24.

Once Kona is in the rear view mirror, all attention will turn to what Blummenfelt does from 2025 on. That ambitious plan to move to pro cycling and the Tour de France appears to be dead, so he is once again all in on triathlon.

What next for Blummenfelt in 2025?

If L.A. 2028 is confirmed as a future goal, the big question will be how ‘Big Blu’ approaches the four-year cycle heading once more towards the greatest show on earth.

As Bu told TRI247 recently, 10 months of short-course preparation and racing heading into Paris 2024 was ‘mission impossible’, so it is likely the 30-year-old from Bergen would transition back down in distance much earlier next time round.

Bu explained: “We’ll have to come back to this later, but if LA becomes realistic, it means transitioning earlier with more short-course racing. However, with the development we have seen around the tactics, involving dedicated domestiques, it has become a less interesting sport from an individual level, and more a “team” sport.”

We also asked Bu who he fears among the opposition this coming Saturday, and his response as ever was illuminating. The focus is 100 percent on elite preparation and performance from his own athletes, and absolutely nothing else.

“I don’t know, as I really don’t pay attention to what others do. I obviously know some of the household names, which have been on the podium the last few years, but not how they are performing and who is on the start line.”

by Graham Shaw

Login to leave a comment

Ironman World Championship Triathlon Men

The inaugural KONA™ race was conceptualized in 1978 as a way to challenge athletes who had seen success at endurance swim, cycling, and running events. Honolulu-based Navy couple Judy and John Collins proposed combining the three toughest endurance races in Hawai’i—the 2.4-mile Waikiki Roughwater Swim, 112 miles of the Around-O’ahu Bike Race and the 26.2-mile Honolulu Marathon—into one event. ...

more...Why Are Runners Suddenly So Fast?

Records are falling and times are dropping. Is it the shoes, or something else?

Consider the Paris Diamond League meet in early June. Jakob Ingebrigtsen smashed the two-mile world best by more than four seconds, becoming just the second man to run back-to-back sub-four-minute miles. Then Faith Kipyegon notched her second world record in a row, outsprinting the reigning record-holder over 5,000 meters just a week after becoming the first woman under 3:50 in the 1,500 meters. Then, to cap the night, Lamecha Girma took down the steeplechase record.

It was a great night—but it was just one of many great nights that track fans have been treated to recently. A week later, at the historic Bislett Games in Oslo, eight men broke 3:30 for 1,500 meters in one race, setting a new record—including Yared Nuguse, who set a new U.S. best. Meet records fell in almost every event. At the collegiate level, an analysis by Oregon-based coach Peter Thompson shows that the number of middle- and long-distance runners hitting elite benchmark times has doubled, tripled, or in some events even quadrupled in the last two years. Earlier in June, four high-school boys broke four minutes for the mile in a single race, matching the total number of people who’d done it in history prior to 2011.

I could go on.

There are two main questions that arise from this buffet of speed. First, is it real? Are runners getting faster across the board, or are we just being fooled by the brilliance of a few individuals and random fluctuations in the depth of different events? Second, if it’s really happening, then why? The easy answer is, “It’s gotta be the shoes” (or, in this case, the super spikes), but does the data really back that up?

I don’t have any definitive answers at this point, but here are my thoughts on some of the possible explanations.

It’s easy to make an anecdotal case that runners are faster than ever. Backing that up with data isn’t quite as straightforward. If you look only at whether the top-ranked time in the world is getting faster or slower from year to year, any trends will depend on whether you happen to have a generational athlete in the event at a given point in time. The effect of an Usain Bolt is bigger than the effect of, say, a new shoe design. Even if you go deeper, the top ten times in any year often come from just one or two races that took place in exceptionally good conditions. So you’re better off looking farther down the list.

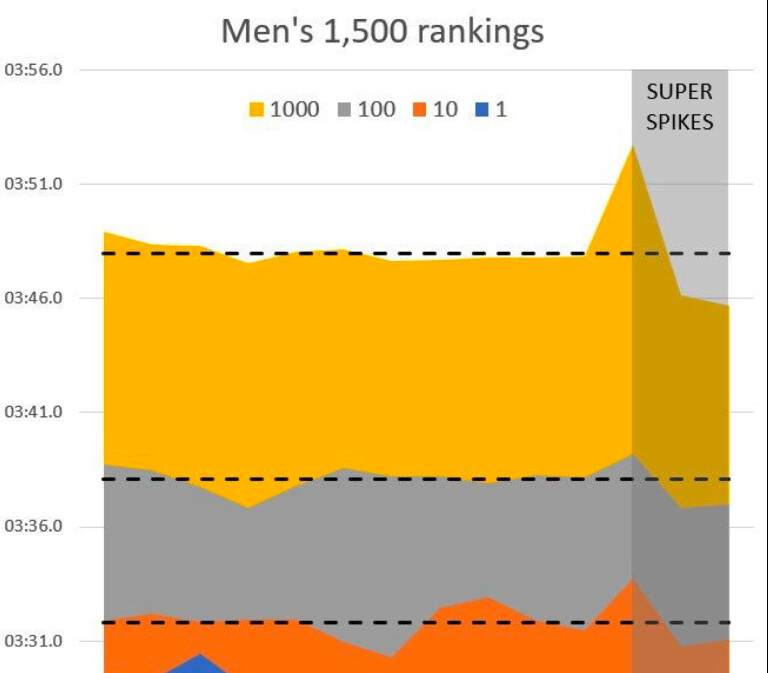

For example, here’s some data for the men’s 1,500 meters between 2009 and 2022, drawn from the World Athletics database. I’ve shown the first, tenth, 100th, and 1,000th ranked performers (not performances) for each year. The horizontal dashed lines show the average for 2009 to 2018. The first super spike prototypes had shown up on the circuit by 2019 at latest, and were widely available by 2021. The big spike of slower times in 2020 is because there were so few races due to the pandemic.

The number-one times don’t show any particular trend. The tenth-best times show a dip since 2021, but no bigger than the dip in 2014-2015 (which corresponded to two particularly fast races in Monaco). For the 100th and 1,000th best times, the pre-pandemic data finally starts to look more consistent, which makes the dip since 2021 more telling. The 1,000th-best performer is now 0.9 percent faster than the pre-pandemic average, and the 100th-best is 0.5 percent faster. This is smaller than the 1.3-percent estimate derived from lab testing of super spikes, but in the ballpark.

Here’s comparable data for the women’s 5,000 meters:

Again, the first- and tenth-ranked times fluctuate too much to draw any conclusions. The 100th and 1,000th places do show an apparent drop in the last few years, by 1.9 and 2.0 percent respectively—more than the lab estimate. There are lots of possible explanations for this discrepancy, including that the benefits of super spikes are reduced at faster speeds.

I’ll add one more graph just for context. Supershoes came to road running way back in 2016 (for prototypes) and became widely available by 2018. I think most observers agree that these shoes really have affected road-running times. So what does the comparable data show for, say, men’s marathon times? Here it is:

The data is confounded by the effects of the pandemic, particularly in 2020. Still, the post-supershoe improvement looks fairly similar to the track data. Compared to the 2009 to 2016 average, last year’s times were 0.7 percent faster at tenth, 1.6 percent faster at 100th, and 1.3 percent faster at 1,000th.

The conclusion I take from all this data? It does like there’s something going on, both on the track and on the roads. But it’s way less obvious in the data than I expected. My subjective feeling was that the last few years have seen records broken and times redefined at a totally unprecedented rate. I thought I’d see robust improvement of at least three or four percent. But that scale of change is not there, at least in the events I sampled.

So with that in mind, what explains the changes we do see?

My starting assumption is that any performance improvements we’ve seen in the last few years are because of the shoes. I’m not going to belabor that point here, because I’ve already written plenty on both road supershoes and super spikes.

But I do want to make one key point. The reason my prime suspect is the shoes is that we have direct laboratory evidence that both types of shoes improve running economy, by around 2 percent on the track and at least 4 percent on the roads (and, to complete the circle, lab evidence that improved running economy directly translates to faster race times). It would take some weird and hitherto undiscovered science in order for the shoes not to make us faster. In contrast, the other hypotheses that I’m going to discuss below may be compelling to various degrees, but all rely on some assumptions and guesses and hand-waving.

Here’s a sentence you wouldn’t have read prior to 2018, from Letsrun’s description of Kipyegon’s thrilling 1,500 world record in Florence: “Kipyegon sprinted away from the pacing lights with 200m to go, lengthening her gap from the green lights as she rounded the turn and entered the home straightaway.” I wrote about World Athletics’s introduction of Wavelight pacing lights when Joshua Cheptegei set the 5,000-meter world record in 2020, positing that more even splits could make a notable difference to times. Good pacing has been a hallmark of this year’s records too, all assisted by Wavelight.

Wavelight doesn’t factor in on the roads, but ever since Eliud Kipchoge’s sub-two marathon exhibitions, big-time marathons have devoted more attention to providing top-notch pacers for their elite runners. That has the double benefit of saving the mental effort of setting the pace, and of reducing air resistance. I think good pacing and drafting are both beneficial. But that can’t explain why the 100th and 1,000th performers seem to be getting faster, because Wavelight and paid rabbits are generally reserved for the front of the pack.

Freed from the tyranny of over-frequent racing during lockdowns, runners spent 2020 building up a massive base of endurance that has catapulted them to new levels. It’s even possible that, having learned their lesson, they’ll continue with this more patient approach to training. This theory has the disadvantage of being both unprovable and unfalsifiable. That doesn’t necessarily mean it’s untrue, but if performance levels don’t start regressing to their pre-pandemic means over the next few years, I’ll remain skeptical.

It’s the “big, sexy thing” in endurance training these days, as miler Hobbs Kessler put it in a recent interview: lactate-guided double-threshold training, as popularized by Norwegian Olympic champions Jakob Ingebrigtsen and Kristian Blummenfelt. As I explained in this article, the approach emphasizes high volumes of threshold training with very tight control on the intensity to avoid going too hard. Whether it’s objectively better than other training approaches remains to be seen—but it hasn’t yet been adopted widely enough to make a noticeable impact on the top-1,000 list.

In the past, when I’ve looked at broad trends in performance over time, one of the first factors I’ve considered is changes in drug availability or drug testing. It’s extremely noticeable (though of course not proof of anything) that long-distance track times took off like a rocket shortly after the introduction of EPO in the early 1990s. If you look carefully, you can find what seems to be the performance signature of various drug-related events like the introduction of EPO testing and, more recently, the implementation of athlete biological passports.

Is there something new on the scene over the last few years? Or are we still seeing the effects of pandemic-related disruptions in out-of-competition drug testing? I certainly hope it’s not the case, but you’d have to be amnesiac to discount the possibility entirely. Once again, the best counterargument is that the performance improvements are noticeable even at the 1,000th-best level—though perhaps I’m being naive.

As you can probably tell, I don’t think any of the alternative explanations I’ve offered so far hold water compared to my default assumption that it’s the shoes. But this last category is a little different. If you spend enough time arguing with people about why runners are getting faster, you’ll encounter a number of broad, hand-waving theories that are hard to substantiate but nonetheless sound reasonable.

For example, I can attest to the fact that the Internet has made training knowledge far more widely accessible than it was when I was a young athlete in the 1990s. Ideas and approaches (like the Norwegian model) are endlessly debated and dissected, and any student of the sport is exposed to multiple perspectives. (In contrast, when I arrived at university and found that the workouts were different from those I’d done in high school, I thought the world was ending.) This theory has been offered frequently over the last decade or more as an explanation for steadily improving U.S. high school times. Maybe it’s true more broadly: people everywhere simply know more about the principles of training, and are doing it better (or at least fewer people are doing really stupid training) compared to the past. Even if elite coaching was always pretty good, this creates a wider pyramid of prospective talent feeding into the elite coaches.

I also have the sense that the pendulum has swung away from sit-and-kick racing towards aggressive front-running. After the 2019 world championships, where super spikes first made headlines, I wrote an article about the unusually fast early paces of the races. Jakob Ingebrigtsen, the current king of the 1,500, is notable for running from the front and pushing the pace rather than relying on a finishing sprint—which likely helps explain why he led those seven other men under 3:30 in Oslo. If runners these days are more focused on running fast times rather than trying to win sprint finishes, it stands to reason that times would get faster overall.

And there are plenty of other theories out there—broader support for professional training groups, better nutrition and recovery, the inevitable march of progress, and some that I’ve undoubtedly missed completely. As I said at the top, I don’t know the answers, and I don’t think anyone else does either. Times do seem to be improving, but not as much as I would have guessed based on all the hype about recent record-breaking. The shoes almost certainly play some role—but if there’s some other secret sauce in there, it’ll be fun trying to figure out what it is.

by Outside Online

Login to leave a comment

Hawaii Ironman World Championships 2022 Results: Gustav Iden Victorious With A New Course Record

Norway's Gustav Iden took the win at the 2022 Hawaii Ironman World Championships in his first try on the Big Island and second Ironman ever in a time of 7:40:24.It was calculated gutsiness that helped Norway’s Gustav Iden claim the 2022 Hawaii Ironman World Championship on his first try with a result that surprised no one – and everyone.

Much like women’s race winner, Chelsea Sodaro, this was Iden’s second Ironman event ever, but he raced it like a veteran, making decisive moves on the bike, pacing well on the run, and seizing the moment to take it all. His time of 7:40:24 is also a new course record and his 2:36 would be a new run course record of 2:36:15.

Read on to see how the 2022 Hawaii Ironman World Championship played out on the Big Island.Hawaii Ironman World Championships 2022: The SwimWith similar conditions to Thursday’s women’s race – slightly choppy with a rolling swell – many assumed the swim would favor the stronger swimmers. But on this day, everyone seemed to be a strong swimmer. Straight from the start cannon, a large pack formed, led by Sam Laidlow and Florian Angert. Despite attempts to pull away in the first half of the swim, neither were successful in building a definitive lead.

Instead, a staggering 19 pros exited the water within 15 seconds of each other, led by Angert in 48:15 and Laidlow in 48:16. This tight pack included some of the most dangerous triathletes in the field, setting up the likes of Kristian Blummenfelt, Gustav Iden, and Braden Currie in perfect position for a tactical race at the front of the field.

One minute and 15 seconds later, another large pack emerged from the water, containing even more strong cyclists capable of quickly bridging the gap. These included Igor Amorelli, Patrick Lange, Rudy Von Berg, and Magnus Ditlev.A third and final large pack, four minutes down from the leaders, contained Matt Hanson, Chris Lieferman, Cam Wurf, Sebastian Kienle, Joe Skipper, and Lionel Sanders.

Hawaii Ironman World Championships 2022: The BikeLaidlow was the one to take charge in the initial miles of the bike, setting an average pace of 27 miles per hour over the first 25 miles. Max Neumann was the only one willing to take the bait, staying just out of Laidlow’s draft to avoid a penalty.

Behind them, big groups stuck together as the crosswinds picked up through the lava fields. Fifty seconds down, the first chase group of 11 included Ditlev, Blummenfelt, Iden, O’Donnell, and Bakkegard; almost two minutes behind was a group of 18 that included contenders like Lange, Currie, Ben Hoffman, and Denis Chevrot.At mile 30 on the bike, the massive groups continued through the rolling hills on the way to Hawi. With 42 men racing within 5 minutes of each other, space was hard to come by – and the referees noticed.

As with the women’s race on Thursday, the penalties began early and often, with Angert, Clement Mignon, Mathias Petersen, and Arnad Gilloux being the first to serve their five-minute punishment for position infractions. Leon Chevalier soon joined them for a one-minute penalty as well.

Soon, more setbacks started to snowball in the men’s field. With each passing mile, Sanders saw the race get away from him as his position slipped from 4:42 down out of the water to 7:13 by mile 30. Colin Chartier, who was in the first large pack out of the swim, found it difficult to recover after an early flat tire. Lange seemed unable to jump on to the train of competitors passing him at full speed, and in a shocking twist, pre-race favorite Currie dropped from the race around mile 35.

Meanwhile, the men’s race began to take shape near the base of Hawi as Ditlev went to the front of the race and took control. Behind him, Laidlow and Neumann could not match the effort, while countrymen and training partners Iden and Blummenfelt sat 30 seconds behind Ditlev, working together near mile 50.

Just after the Hawi turnaround, Laidlow reclaimed his lead, but Ditlev, Neumann, Blummenfelt, and Iden were hot on his tail. Further back, a group including Kyle Smith, Tim O’Donnell, and Jesper Svensson trailed the leaders by 2:30; 3:30 back from the leaders were Kristian Hogenhaug and Daniel Bakkegard. A big group of dangerous bike/runners sat 5 minutes behind the front pack that included Wurf, Chevalier, Skipper, Lange, Kienle, and Andreas Dreitz.

Near mile 90, disorganization plagued the chase group of Iden, Blummenfelt, Ditlev, and Neumann as they lost an additional 1:30 to the race leader, Laidlow. Further back, Wurf, Kienle, and Chevalier led a rally to try to get within striking distance of the front, putting 2:20 into the Norwegian group over a span of over 10 miles.

As the race barreled toward T2, the chaos continued, with Ditlev receiving a five-minute position penalty at a time when most would be making their critical moves in a race.Up front, Laidlow seemed to not know – or care – about what was playing out behind him. Instead, the young gun stayed focused on his own race, surging ahead. By mile 88, Laidlow’s lead grew to 2:37; at mile 94, a 4:11 advantage.

Heading into T2, Laidlow smashed Cam Wurf’s 2018 bike course record with a split of 4:04:36—knocking almost five minutes off the previous time. Behind him, the chase group was six minutes down, and the second chase had 8:30-9:45 to make up.

Laidlow set out on the run with a target on his back. The question then became: Would his bold bike strategy pay off, or would it end in disaster? Could he actually beat the notoriously fast Norwegian runners to the finish line? Could anyone?

Hawaii Ironman World Championships 2022: The RunAs the men’s pro field moved through T2, the field shifted from large packs to a steady trickle. It was soon clear who had paced themselves well on the bike and who had burned their matches. Behind Laidlow, Blummenfelt and Iden led the charge, setting out at a 5:54 minute-per-mile pace to the leader’s 6:13 pace. Behind them, O’Donnell and Kienle were the fastest movers in the second chase pack early in the run, along with Ditlev—finally released from his penalty.

As Laidlow made his way up the Palani climb, his pace slowed to 6:23. Iden and Blummenfelt powered on, checking their watches to ensure they were sticking to their staggeringly consistent 5:58 pace. With every footfall, they seemed to cut into Laidlow’s lead. Neumann, looking to hold his own in his Kona debut, followed suit.

Slightly further back, strong runners like Kienle and Ditlev were working together as well, slowly making their way up through the top ten, through the first half of the marathon—as did Joe Skipper. At the halfway point, they found themselves in fifth and sixth place, with elder statesman Kienle offering words of encouragement to the young Dane as they ran together.Between miles 11 and 16, the Norwegians’ march toward Laidlow started to stall as the Frenchman found a way to staunch the bleeding. As he made his way out the Queen K, it seemed as if he found a pace he could comfortably sustain.

At the turnaround in the infamous Energy Lab, Laidlow could see exactly where he was relative to his competition. He knew he had a lead of just over two minutes, but what he didn’t know was whether or not the Norwegians had another gear. Anticipating a battle, Laidlow gathered all he could from the aid stations – cups of ice, a gallon bottle of water to douse himself on the scalding Kona pavement.Indeed, Iden had just decided to drop his friend and training partner, pulling ahead in the Energy Lab just before mile 19, while Blummenfelt trailed behind. With less than eight miles to go, Iden broke out into 4:38 min/mi pace, laser-focused on the task ahead.

At mile 22, Iden gave Laidlow a pat on the back to let him know his time at the front was up. With a handshake and a smile, Iden made the pass, striding confidently to the finish line.After the pass, it was the Iden show, as the Norwegian extended his lead to set a new course record with a time of 7:40:24 and a new run course record of 2:36:15. Not far behind, Sam Laidlow valiantly hung on for second place with a time that also broke the previous run record, 7:42:24. Kristian Blummenfelt would fade only slightly, but still stand on the podium with another course record time of 7:43:23.

“That was so freaking hard,” Iden said just moments after his record-setting finish. “The last 10K I was worried about the legend of the island killing me. Everything was going pretty smoothly until I caught Sam Laidlow. When I passed him, the island really tried“That was so epic, and I’m so proud of Sam and Kristian making the podium. I’m not sure if I’m coming back here, this was too hard.”

Laidlow was tearful after leading the race for so long.

“I was just loving it, I’ve been dreaming this since I was four or five,” said an emotional Laidlow. “This is my style of racing. I’ve been inspired by Jan Frodeno, and the way he races. If I win, I want to win like he does. I’m just getting started.

“It’s hard to believe as I’ve been watching the Norwegians, and to beat the Olympic champion, I really can’t put words to it.”

Login to leave a comment

How to train like a Norwegian: norwegian endurance athletes have been dominating competitions around the world. What's their secret?

Norway has long been known for producing some of the world’s best cross-country skiers, but in recent years the small Nordic country has also been turning out several other world-class endurance athletes. Kristian Blummenfelt took home the gold in the men’s triathlon at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, and of course, few runners are unfamiliar with the Ingebrigtsen brothers, led by Jakob Ingebrigtsen’s gold medal performance in the Olympic 1,500m final.

How are so many incredible athletes coming out of such a small country? Olympian, doctor, and coach Marius Bakken recently published a lengthy article about the Norwegian training system, and their approach may surprise you.

Before we get started

The article, which can be read in full here, is very lengthy and includes a tonne of detail. It is a bit heavy, so we’re going to pull out the main points to give you an overview so you can apply some of the Norwegian training principles to your own training.

Before we do that, there are a few important things to keep in mind. The first is that these training principles have almost exclusively been tested on elite athletes, who are genetically different from the average runner. This doesn’t mean that none of these principles apply to recreational runners, but understand that your results may differ depending on your age, sex and experience.

With that in mind, here are the big takeaways from Bakken’s paper:

Controlled intensity + high volume = success

The Norwegian training model has athletes control their intensity by monitoring their lactate levels, with a large portion of their running volume done at an easy pace (or zone one, according to this study). The majority of their interval training is done at an intensity that is just below their lactate threshold (zone two), and a very small amount of their training is done at zone three (high intensity).

This is important because there are two factors that might cause you to slow down during a race or a hard effort: mechanical factors (your musculoskeletal, neuromuscular and biomechanical systems) and your aerobic system (your heart, lungs and cells). For many athletes, their aerobic system tends to be the limiting factor between the two.

This is where your lactate threshold comes in. Lactate is a by-product of glucose metabolism and energy production, and your body can re-cycle that lactate to be used to produce even more energy using a lactate-shuttling mechanism. When that mechanism is over-stressed, your lactate levels rise, you accumulate fatigue, and you have to slow down. Raising your lactate threshold (the point at which lactate begins to accumulate) can produce significant performance benefits.

This is the reason why the Norwegians focus the majority of their interval work at that lactate threshold zone. Could they go faster? Absolutely. But they would be missing out on the aerobic benefits. Of course, most recreational athletes don’t have the tools to monitor their lactate threshold, but you can keep yourself within that zone 2 range during an interval workout using effort-based cues, like running a pace you can maintain for an hour, running 15K or half-marathon pace or simply by avoiding that muscle-burning feeling (a sure-fire sign you’ve accumulated lactate).

Running at this pace also allows you to do a much greater volume of intervals (as long as you have the base to do so), which will ultimately improve performance.

A small amount of high-intensity work

As we mentioned above, the Norwegians don’t neglect high-intensity work altogether. In his description of the Norwegian training system, Bakken still includes top-end, high-intensity (zone 3) work, but it is primarily made up of fast strides and short hill repeats. This type of work will develop those mechanical factors mentioned earlier, which will improve your speed and power.

The Norwegian training approach operates on the principle that you don’t need a tonne of volume at that intensity to elicit the desired training effect. This is because, for most runners, the speed you can run will be largely dictated by your aerobic capacity.

The caveat to this, as explained in this article, is that younger athletes, or less-experienced athletes, may need to spend more time developing their speed at their VO2 max in order for this type of training to be effective. This may also be true for athletes who aren’t able to do a tonne of volume in their training, either because of injury issues or time constraints.

Double down

According to Bakken’s paper, one of the biggest differences between the Norwegian training model and other training models is the inclusion of days when the athlete does not one, but two threshold workouts. Of course, the concept of doubling (running once in the morning and then again in the afternoon/evening) is not new. In fact, it is a very commonplace practice for most elite runners. In most cases, though, the athlete will do one workout and one recovery run in the same day, not two workouts.

If doing two workouts in one day sounds outrageous to you, remember that both of these sessions are threshold workouts, so athletes are not running at their all-out max. When these workouts are run at the correct intensity, athletes don’t accumulate too much fatigue so they can turn around and do it again a few hours later. This allows them to do a greater volume of work than they could if they tried to do one big session.

This final point is when the Norwegian training approach becomes less approachable for the recreational runner. Most of us don’t have the time to do two workouts in one day, nor do we have the physical ability (it takes time to build up the capacity to do consistent double runs at an easy pace, let alone doing two workouts in one day).

The bottom line

While most of us won’t be (and shouldn’t be) doing doubles, there are still a number of valuable takeaways from Bakken’s paper.:

According to the Norwegian training principles, developing your aerobic system should be your highest priority as a distance runner. This means the majority of your workouts should be done at your lactate threshold pace, and shouldn’t leave you completely spent at the end. In other words, don’t race your workouts.

Developing speed is still important, but it should only make up a small part of your training program.

Always keep your easy days easy. Control is key.

by Brittany Hambleton

Login to leave a comment