Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #Diabetes

Today's Running News

Move or Die: SCIENTISTS CRUNCHED THE NUMBERS TO COME UP WITH THE SINGLE BEST PREDICTOR OF HOW LONG YOU’LL LIVE—AND CAME UP WITH A SURPRISINGLY LOW-TECH ANSWER

TO PREDICT your longevity, you have two main options. You can rely on the routine tests and measurements your doctor likes to order for you, such as blood pressure, cholesterol levels, weight, and so on. Or you can go down a biohacking rabbit hole the way tech millionaire turned longevity guru Bryan Johnson did. Johnson’s obsessive self-measurement protocol involves tracking more than a hundred biomarkers, ranging from the telomere length in blood cells to the speed of his urine stream (which, at 25 milliliters per second, he reports, is in the 90th percentile of 40-year-olds).

Or perhaps there is a simpler option. The goal of self-measurement is to scrutinize which factors truly predict longevity, so that you can try to change them before it’s too late. A new study from biostatisticians at the University of Colorado, Johns Hopkins University, and several other institutions crunched data from the long-running National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), comparing the predictive power of 15 potential longevity markers. The winner—a better predictor than having diabetes or heart disease, receiving a cancer diagnosis, or even how old you are—was the amount of physical activity you perform in a typical day, as measured by a wrist tracker. Forget pee speed. The message to remember is: move or die.

It’s hardly revolutionary to suggest that exercise is good for you, of course. But the fact that people continue to latch on to ever more esoteric minutiae suggests that we continue to undersell its benefits. That might be a data problem, at least in part. It’s famously hard to quantify how much you move in a given day, and early epidemiological studies tended to rely on surveys in which people were asked to estimate how much they exercised. Later studies used cumbersome hip-mounted accelerometers that were seldom worn around the clock. The new study, published in Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, draws on NHANES data from subjects recruited between 2011 and 2014, the first wave of the study to employ convenient wrist-worn accelerometers that stay on all day and night.

Sure enough, it turns out that better data yields better predictions. The study zeroed in on 3,600 subjects between the ages of 50 and 80, and tracked them to see who died in the years following their baseline measurements. In addition to physical activity, the subjects were assessed for 14 of the best-known traditional risk factors for mortality: basic demographic information (age, gender, body mass index, race or ethnicity, educational level), lifestyle habits (alcohol consumption, smoking), preexisting medical conditions (diabetes, heart disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, cancer, mobility problems), and self-reported overall health.

Take a moment to let that sink in: how much and how vigorously you move are more important than how old you are as a predictor of how many years you’ve got left.

The best predictors? Physical activity, followed by age, mobility problems, self-assessed health, diabetes, and smoking. Take a moment to let that sink in: how much and how vigorously you move are more important than how old you are as a predictor of the years you’ve got left.

These results don’t arrive out of nowhere. Back in 2016, the American Heart Association issued a scientific statement calling for cardiorespiratory fitness, which is what VO2 max tests measure, to be considered a vital sign that doctors assess during routine checkups. The accumulated evidence, according to the AHA, indicates that low VO2 max is a potentially stronger predictor of mortality than usual suspects like smoking, cholesterol, and high blood pressure. But there’s a key difference between the two data points: VO2 max is about 50 percent determined by your genes, whereas how much you move is more or less up to you.

All this suggests that the hype about wearable fitness trackers over the past decade or so might be justified. Wrist-worn accelerometers like Apple Watches, Fitbits, and Whoop bands, according to the new data, are tracking the single most powerful predictor of your future health. There’s a caveat, though, according to Erjia Cui, a University of Minnesota biostatistics professor and the joint lead author of the study. Consumer wearables generally spit out some sort of proprietary activity score instead of providing raw data, so it isn’t clear whether those activity scores have the same predictive value as Cui’s analysis. Still, the results suggest that tracking your total movement throughout the day, rather than just formal workouts, might be a powerful health check.

The inevitable question, then, is how much movement, and of what type, we need in order to live as long as possible. What’s the target we should be aiming for? Cui and his colleagues track the raw acceleration data in increments of a hundredth of a second, which doesn’t translate very well to the screen of your smartwatch. The challenge remains about how to translate that flood of data into simple advice regarding how many minutes of daily exercise you need, how hard that exercise needs to be, and how much you should move around when not exercising.

To be honest, though, I’m not sure the quest to determine an exact formula for how much we should move is all that different from the belief that measuring your urine speed will give you actionable insights about your rate of aging. Metrics do matter, and keeping tabs on biomarkers backed by actual science, like blood pressure, makes sense. But it’s worth remembering that the measurement is not the object; the map is not the road. What’s exciting about Cui’s data is how it reshuffles our priorities, shifting the focus from all the little things our wearable tech now tracks to the one big thing that really works—and which is also a worthwhile goal for its own sake. Want to live forever? Open the door, step outside, and get moving.

Login to leave a comment

What’s Your Why? Our Readers Share Their Biggest Motivators for Getting Out There to Run

We asked runners what motivates them to get out and hit the road—their answers may inspire you.

Why do you run? If you’ve never thought about it before, ask yourself now.

Being intentional about the reason why you run is a crucial part of maintaining motivation, especially if you’re just starting your running journey. Most of us know the research-backed benefits of running, but what is going to be that thing that gets you out the door when you don’t even feel like moving?

While your reason should be unique and personal to you, here’s some inspiration from our dedicated Runner’s World+ members and social audiences on Instagram and Facebook to keep in mind when considering what your why is.

For Myself

“Running is my ‘me time.’ It is time for me to simply run, listen to music, and enjoy the outdoors. It allows me to begin each day with a sense of accomplishment, and along the way I plan my to-do list, calculate finances, and solve problems. I do my best thinking when I am running. It also keeps me focused on my health and I always have at least one half marathon or marathon to train for.”—Jill Pompi (RW+ member)

“Because it’s the only thing in my life that’s just mine.”—April Thomson

“As a mom of three littles, running is my ‘me time.’ Time to fill my own cup; time to work toward a personal goal; time to show my kids that I enjoy movement simply because it helps me be happy, healthy, and strong!”—Marlena Shaw (RW+ member)

“It’s my time—no one asking me for anything. It’s me vs. me. Love the feeling after a long run.”—Spullins JB

“Running is just for me, and I run so I can be my best self. I don’t mean physically. Sure, I love how strong my legs feel when I cross a finish line or that good burn after a long run. But my best self is found when I hit the pavement and process whatever is going on in my life. I have two young kids (ages 3 and 14 months), and I am constantly being poked, pulled, and called. When I lace up my running shoes, the stress melts away and I am a better mother because of it.”—Melissa Hofstrand (RW+ member)

“To escape from reality for a brief moment and enjoy my ME time.”—Yuri Aguilar

“Sometimes to relax, regroup, and shake out anything bothering me… but usually to start my day off just right!”—Erin Carey Ryan

For My Health

“My health, specifically my heart.”—Kati Johnson (RW+ member)

“To maintain my health and challenge myself to reach new running goals.”—Gwen Jacobson (RW+ member)

“To fight bad genetics and hear my grandkids say, ‘Whoa, Grandma!’”—Michele (RW+ member)

“My asthma kept me from doing exercise for so many years. I’m running because I can finally do something I never thought possible.”—Patricia McHugh (RW+ member)

“To save my life. I am type 2 diabetic by way of having PCOS. By the time I was diagnosed with PCOS, I had developed full-blown diabetes. I run now to train for a half marathon I crazily signed up for and to get in shape for my first century ride next year. I will run and bike towards a cure.”—Stephanie Gold (RW+ member)

“I exercise and stay active so that I can be mobile and independent as long as possible as I get older. I choose running because it gives me such a great sense of accomplishment.”—Lisa Bartlett

“I run because last year I got Pulmonary embolisms in my lungs and now I want to improve my health and my lungs and spread awareness!”—Jennifer Cole

“Manage stress and support in quitting smoking.”—Aude Carlson (RW+ member)

“Keeps my AFib under control.”—Todd W. Peterson

“I want to be able to walk well into my old age. I have family members who have significantly lost mobility due to their unwillingness to exercise.”—Amy Watkins (RW+ member)

“To control my type 2 diabetes! It works!”—Mike Shamus

For Someone Else

“I started running after witnessing my mom complete a marathon and was overcome with emotion when she finished. I began running the very next year and completed a half marathon with my mom and have been running ever since. Running does so many things for me. It’s my escape, it keeps me centered, helps me to focus, a confidence builder but more importantly allows me to follow in the footsteps of my mom and continue to honor her. I wear a shirt with a picture of her running our last race together so that she’s running with me. I love to run!”—Chantal (RW+ member)

“My daughter.”—Jesse Sturnfield (RW+ member)

“To keep my sanity. Also, I wanna show my kids if they work hard, don’t give up, and find a love for something, they can accomplish anything in life. When they’re tired, stressed, unhappy, just to channel in and get the work done. They’ve been there when I run my marathons and have shown support and encouragement, and I’ll do the same for them. My daughter joined cross country this year and wants to join again next year. My son is wanting to join as well.”—Angela Yawea

“Because my dad ran. I lost him six years ago and clearing his flat I found his medal from Reading Half Marathon in 1988. Holding it inspired me to change. I have my dad’s and my medal from the same race together.”—Stumpy Taylor

For My Mental Health

“To keep my sanity!”—Libby Meyer (RW+ member)

“It’s my therapy.”—Allie Haight

“Running is my ultimate stressbuster! As a middle-aged tech leader, husband, and father to two preteens, running generates all the right endorphins and energy to ensure I’m on top of my game—all of my games!”—Annu Kristipati (RW+ member)

“Cheaper than therapy.”—Louie J. Frucci

“Running helps me dealing with my anxiety, my mental health, but especially this past year with grief. I lost my dad last year and couldn’t work out for two months. I was able to go back to working out thanks to running. Then I signed up for my first marathon. That was on the one-year anniversary of my dad’s passing. Running is my way to feel my dad close and be able to connect with him.”—Fadela (RW+ member)

“Because it has the power to mute my anxiety and self-doubt.”—Nicholas Kuiper

“Running makes me happy. It reduces my stress and anxiety and improves my mental health. It keeps my cardiovascular system strong.”—Suzanne Reisman (RW+ member)

“To stay calm in the chaos.”—Christine Starkweather

To Feel Powerful & Free

“Because it makes me feel powerful and healthy (sometimes only once it’s over).”—Laura (RW+ member)

“To be a real-life video game character.”—Erin Fan (RW+ member)

“Feels like I’m flying. Powerful and free.”—Tenaya Hergert

“I run because I want to be healthier in my 50s than I was in my 30s! And, also, running makes me feel powerful.”—Laura (RW+ member)

“Running gives me a voice.”—Becky Westcott Capazz

“It makes me feel strong and confident, that I can handle everything else in my day.”—Rebecca Eisenbacher (RW+ member)

“To feel free, manage anxiety, accomplish increasing mileage.”—Barbara Saunders (RW+ member)

“Total freedom. Slap your shoes on and be free.”—coach_shasonta

For Connection

“Running makes me feel strong and is my way of meditating. I also love that I’ve been able to connect with people and make so many new friends through running. I enjoy seeing my fitness progression.”—Gisele Carig (RW+ member)

“For my mental health and human connection with friends.”—lizpowers76

“Refreshes the spirit. BTW: I can no longer run; I train and enter races as a walker. Have made many new friends who accept me for just being there.”—Lewis Silverman

“I have many reasons. I connect with my running partners on some runs. I connect with God on others. I find a sense of accomplishment. I like to test what my body can tolerate.”—Tim Thomas (RW+ member)

“When I’m alone, I run to quiet my mind. It is meditative and rejuvenating. I also run to be social. The running community is the best.”—Andy Romanelli (RW+ member)

“Makes 77 feel young and hanging around with younger runners is a whole lot of fun. Not to mention I’ve been loving going for a run for more than 46 years.”—Barbara Ann Morrissey

Because I Love Racing

“I want to improve my 5K time.”—Courtney Danko-Searcy (RW+ member)

“The feeling I have on race day, within the first mile, that all the training is paying off.”—Mark Hopkins (RW+ member)

“My husband and I started running about six years when my son, who was about 12 at the time, had run over 25 5Ks. It took about a year until we were ready for our first 5K. We love running and training together. Running helps me at the end of a long teaching day, and it just feels so good after! We have since ran many 5Ks, some 10Ks, and two half marathons!”—Suzy Wintjen (RW+ member)

“It’s at the end of Ironman.”—Cheryl Turpin

“First, I began to improve my health, then I got hooked. Fifteen years later I am chasing my Six Star Medal.”—Jorge Mitey (RW+ member)

“It’s something I’ve always done since fifth grade. I got into racing 25 years ago. I love the challenge running gives me to constantly improve and get back out there whenever I’ve been injured or ill; and next month will one year since starting my first running streak! Most of all, I run because I love how it makes me feel. It has gotten me through the worst times in my life. Whenever I’m having a bad day, whether I’ve already gone running or not, I go running. It always calms me and makes feel better.”—Elle Escochea Grunert

So That I Can Indulge

“Because I love carbo loading.” —Bud Bjanuar

“I run so I can eat whatever I want and still be in shape!”—Christi Webb (RW+ member)

“I run to eat poutine.”—Robin Bosse

“So I can drink beer!”—Kathy Davis Ward

“Because I am a chocoholic.”—Chantal Englebert

“Faster than walking and I like tacos.”—Shelly Pedergnana

“I run to eat crispy pata.”—Arrin Villareal

To Get Outside

“Fitness and peace of mind. Also, a great way to explore neighborhoods and the outdoors.”—Sue Padden

“The feel of being outside with my dog. Watching him enjoy the run lets me enjoy the run.”—Stan (RW+ member)

“It’s my time with nature. It’s for me to clear my head and think.”—Assa Burton

“Running is my sanctuary. It’s where I can clear my mind, letting go of stress and finding clarity with each step. The rhythm of my feet hitting the ground is a meditative escape, helping me to focus and recharge. Physically, running keeps me in peak condition, building strength and endurance while boosting my overall health. But what I love most is being outside, feeling the fresh air, and soaking in the beauty of nature. Whether it’s a sunlit trail or a quiet street at dawn, running connects me to the world around me in a way nothing else can.”—Adam Scolatti (RW+ member)

Because I Can

“This is my ‘stock’ answer. I do because I can and I can because I do.”—Chip Kidd

“Because I’m not ready to give up yet.”—Martha Rhine (RW+ member)

“Because I was completely disabled, not able to move, stand, walk, talk, or do anything... stuck in the hospital for 13 weeks. When I was discharged and started to walk a little, I needed something to help me get some kind of life back. Running was it.”—Rob Snavely

“Because I’m 70, and not dead yet.”—Michele Glover

“Because I can. One day I won’t be able to and it’s not today.”—Mike Bravo

“Because one day I’ll be old and everything will hurt, and it’s the one thing in my life that lately makes me happy. When you’re running you forget everything. If you’re still thinking of debt, sadness, breakups, you’re not trying hard enough. Every day you have to push yourself.”—Miryam Hernandez

“Because I still can… at 73.”—Joanne Gile Michaelsen

“Forty-five years, why stop now? Never regret going for a run.”—Leslie Kitching

“Sixty-one years old. Been running since I was 15. Because a day without running is like a day without brushing your teeth.”—Sharon Graeber Hall

To Prove it to Myself or Someone Else

“To prove I can. And prove my mind is more powerful than my body.”—Colton James

“Because I still can, and everyone tells me I can’t!”—Lloyd K Leverett

“To tell people I did.”—Chris S. Charlett

“I’m 55. Basketball days are over. The need to compete is still there, and even if that means competing with myself, running allows me to do that.”—Shawn Davis

Because I Hate How I Feel When I Don’t

“I don’t know, but recently I injured my knee, and I was sad I couldn’t run. Thank god, it healed itself. I think running gives me inner peace.”—Jose Murga

“Because I hate the way my brain itches when I don’t.”—Joe Baron

“Because it’s better than smacking my family upside the head from being over stimulated. [It] helps my mental health.”—heatherbrubaker19

“I don’t like it until it’s over.”—Laurie Stinson Fuller

“So that I am tolerable to my husband!”—Dimitra Zakas

“It’s either that or sending my work computer flying out the window like a frisbee on the regular.”—Ayla Amon

“It feels so good when I stop.”—Sarah Wiley

Login to leave a comment

3 Years Ago, He Weighed Almost 500 Pounds. Now He’s a Marathon Finisher

César Torruella says running has been instrumental in building a healthy life.

In 2021, César Torruella struggled to walk even short distances around his neighborhood in Houston, Texas. Weighing in at 495 pounds, the former vocalist and music teacher underwent bariatric surgery to address critical health issues that were putting his life at risk.

Three and a half years later, Torruella completed his first 26.2 at the 2024 Chicago Marathon, an experience he considers a “celebration” after many hard-fought moments in the 35-year-old’s weight-loss journey.

On race day, Sunday, October 13, Torruella faced setbacks—including a pulled muscle in his right quad, which forced him into the medical tent at mile 17—but he continued on, often pushing through tears in the latter half of the race.

In the tougher miles, Torruella focused on regulating his breath under a compression suit designed to hold in excess skin and prevent chafing beneath his shorts and singlet. He thought about running to his partner, Esteban, at mile 20 in the Pilsen neighborhood. He also focused on who he would become when he finally reached the finish in Grant Park.

“This pain and struggle was necessary to carry me through closing this chapter of my life after losing so much weight,” Torruella told Runner’s World a few days after completing the marathon in 5:58:46.

“I feel like a new version of myself was born as I crossed that finish line.”

Growing up in Puerto Rico and later moving to Houston in 2012, Torruella struggled with weight management for most of his life. When the pandemic forced everyone into quarantine, Torruella ate as a way to cope. “I found asylum in food to a point that it got out of control,” he said. “I became addicted to eating and eating unhealthy.”

In 2021, Torruella weighed almost 500 pounds. He was diagnosed with high blood pressure, pre-diabetes, and hypertension. He was also starting to lose his vision, a condition that can develop as a result of high blood pressure and diabetes.

It was a wakeup call for the singer, who decided to change his habits and undergo bariatric surgery—a weight-loss procedure that involves making changes to the digestive system to help the patient lose weight. After the procedure, patients must make permanent healthy changes to their diet and exercise routine to help ensure the long-term success of the surgery.

Post-surgery in June 2021, Torruella had to relearn the basics of eating (a process that involves different phases, similar to how a baby learns how to eat solid foods) and how to exercise.

“Never in my life did I know what going to the gym meant or what you do when you get there,” Torruella said. “I was learning how to move again, how to accept my body, and how to find love in the foods that nourish me.”

Six months after surgery, Torruella lost almost 200 pounds, a result of medical and family support as well as

“I wouldn’t be closing this chapter of my life if it weren’t for the opportunity I got through TCS,” Torruella said. “They gave me a platform to advocate for arts education and to encourage other teachers and folks that are struggling with obesity that this is possible.”

After the defining experience in Chicago, Torruella is already planning to take on another marathon next year. This time, he wants to run a personal best.

“I will gain a lot more flexibility and freedom to move [after surgery], and then I can start training to finish my marathon a little faster,” he said.

Login to leave a comment

'Micro-Walks' Could Burn More Calories Than Longer Ones. Here's How Long You Should Be Walking For

A new study just discovered the benefits of shorter strolls.

For years, doctors have stressed the importance of being active during your day—after all, research has found that sitting for too long raises your risk of a slew of serious health conditions, including cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. But the idea of going for hour-long walks can be overwhelming. Now, new research suggests you don’t need to jam in a massive stroll into each day: Instead, you can go for “micro-walks.”

That’s the main takeaway from a study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, which found that micro-walks may be even better for you than long ones. Here’s the deal.

What are ‘micro-walks’?

In this study, a “micro-walk” is defined as walking between 10 and 30 seconds at a time (with breaks in between your next walk).

Are ‘micro-walks’ more beneficial for your health? Why?

It depends on how you’re looking at it. In this particular study, volunteers walked on a treadmill or climbed a short flight of stairs for different periods of time, ranging from 10 seconds to four minutes. The study participants wore masks to measure their oxygen intake (which can be used to calculate energy or calorie consumption).

The researchers discovered that people who walked in short bursts used up to 60 per cent more energy than longer ones, despite the walks covering the same distance. (The more energy you expend, the more calories you can burn.)

Basically, you may be able to rev up your metabolism and burn more calories if you do short bursts of walking versus longer cruises around.

Albert Matheny, RD, CSCS, a co-founder of SoHo Strength Lab, says there’s something to this. “Getting activity throughout the day, in general, is better for people,” he says. “It’s better for circulation, mental health, and digestive health.”

You’re also more likely

by Women Health magazine

Login to leave a comment

How Many Calories Do You Actually Burn While Running?

Most people overestimate how many calories they torch while running. Here’s how to figure out your numbers—and tips to boost the burn.

There are so many reasons to run, including spending time in nature, taking a break from scrolling social media, and hanging with like-minded people. One of the most common reasons people turn to the sport: to boost physical and mental health. In fact, three out of four runners say staying healthy and in shape is a primary motivation for lacing up, according to a survey from Running USA.

For many people, “staying healthy and in shape” translates to burning calories and keeping weight in check, and running is a top activity for revving your heart rate and blasting calories. But just how many calories do you burn running one mile?

Turns out most people don’t know the answer: When runners completed both moderate- and vigorous-intensity workouts on a treadmill, they greatly overestimated how many calories they burned—some by as much as 72 percent—in a 2016 study in Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise.

So let’s break down approximately how many calories the average runner burns over the course of one mile and how to calculate your calorie-burn rate, plus expert tips to raise that number.

How many calories does the average runner burn running one mile?

It’s difficult to generalize how many calories everyone would burn running one mile, as many factors play into your energy expenditure. But the general baseline is that runners burn about 100 calories per mile, April Gatlin, certified personal trainer and senior master coach for STRIDE Fitness in Chicago tells Runner’s World.

Two important factors that change that number are the intensity of your run and your weight, according to the 2024 Adult Compendium of Physical Activity, which calculates the energy cost of physical activity based on metabolic equivalents (METs).

Based on the MET chart, running a 10-minute mile (6 mph) is equivalent to about 9.3 METs. That means a 150-pound person (68 kilograms), would burn about 11 calories per minute or about 110 calories in a mile when running at 6 mph.

To calculate calories burned per minute using METs, follow this formula: METs x 3.5 x (your bodyweight in kilograms) / 200

Intensity and weight aren’t the only variables that can alter how many calories you burn running a mile, though. “Running mechanics play a big role in caloric expenditure—different aspects such as ground contact time, vertical motion, and muscular strength have a significant effect on the amount of calories that are burned or energy that is expended in terms of oxygen consumption,” Grace Horan, exercise physiologist at Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City tells Runner’s World.

That oxygen consumption, along with fuel utilization—which is how our cells use carbs and fat for fuel—is what caloric expenditure is all about, she says. Because there’s more vertical motion (or bounce) in running compared with walking, that translates to higher calorie burn. “Your body is now not only using energy to travel horizontally but vertically as well,” Horan adds.

What factors affect your one-mile calorie burn?

1. Weight

“The heavier the runner, the higher the calorie burn as their body is working harder to move forward,” says Gatlin. In fact, a 185-pound person burns nearly 100 calories more per 30 minutes of running at 5 mph compared with a 125-pound person, according to estimates from Harvard Medical School.

2. Pace

Running a fast mile will burn a higher number of calories than a slow mile, says Gatlin, especially if you mix in speed intervals: “Intervals will burn more calories overall due to the varied high-to-low heart rate burst causing excess post-exercise oxygen consumption (EPOC), which is an after-burn effect,” she explains. “That causes the body to continue to burn at the higher metabolic rate after the training is complete.”

The same holds true about running versus walking: People who ran a mile showed increased energy expenditure (read: calorie burn) for 15 minutes postworkout while those who walked the same distance increased the after-burn effect for only 10 minutes, according to a study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research in 2012, involving 15 males and 15 females.

3. Sex

“There is also some evidence that gender plays a role in caloric expenditure, with females often burning less calories compared to their male counterparts when running at the same speed for the same distance,” says Horan.

However, she notes, the difference in overall body mass between men and women is generally thought to be the primary cause for this.

4. Fitness, biomechanics, and genes

While concrete stats, such as speed and weight, contribute to calorie burn, so do fluctuating variables that are more difficult to count. “Burning calories is directly related to oxygen consumption, which is determined largely by the ability of the lungs to take in large amount of oxygen and the heart to pump oxygenated and nutrient-filled blood to the working muscles, so cardiorespiratory fitness [level] has a major effect [on calorie burn],” notes Horan. While there’s no simple way to incorporate these details into your calorie estimates, know that they do have a bearing.

In other words, while you can get a rough estimate of how many calories you burn over a given distance or time, remember that these are just estimates.

How can you estimate your personal calorie burn?

In addition to the MET equation mentioned above, Runner’s World has a calories burned calculator to help. Pop in your weight, along with how far you ran and how long it took you, and it’ll pinpoint approximately how many calories you expended on that outing.

While this does take some variables into account (i.e., your weight and speed), it doesn’t factor in extras like your fitness level or what kind of terrain you covered. For example, if your course was totally flat, you likely torched slightly fewer calories than if you’d encountered tons of hills, according to Gatlin.

How can you increase the calorie burn of your one-mile run?

1. Add in speed

The higher your effort during a run, the more calories you’ll burn per minute, which also means you can expend more energy in less time the faster you run.

Research backs this up: A study published in 2019 found that high-intensity interval training (doing 10 reps of one-minute intervals at 100 percent of VO2 max with one minute of recovery) took less time to reach the same energy expenditure of a moderate-intensity workout (going for 35 minutes at 65 percent of VO2 max).

Another study, published in 2013, also found that sprint interval training can increase total daily energy expenditure after one session.

2. Tackle hills

Heading to a hilly course outside (or cranking up the incline on a treadmill) is great for torching calories, because it’s as if you’re adding resistance training to the workout, notes Gatlin. That’s because your lower-body muscles perform at a higher level of mechanical work to increase your potential energy on an incline, compared with level or downhill running, according to a 2016 article in Sports Medicine.

3. Break up your run

Planning to run three miles today? If you break them up into three one-mile runs throughout the day and run each of those at a faster pace than you’d run one steady-state run, you’ll boost the calorie burn, says Gatlin.

The reason: It goes back to that afterburn effect—you burn more calories when you’re done running—as well as the ability to turn those shorter runs into higher-intensity exercise.

What other benefits do you gain from running a mile?

All this being said, frying calories is hardly the only benefit of a running routine. Opt to run instead of walk a mile and you will also boost your aerobic capacity, muscular endurance, and metabolic rate, says Gatlin.

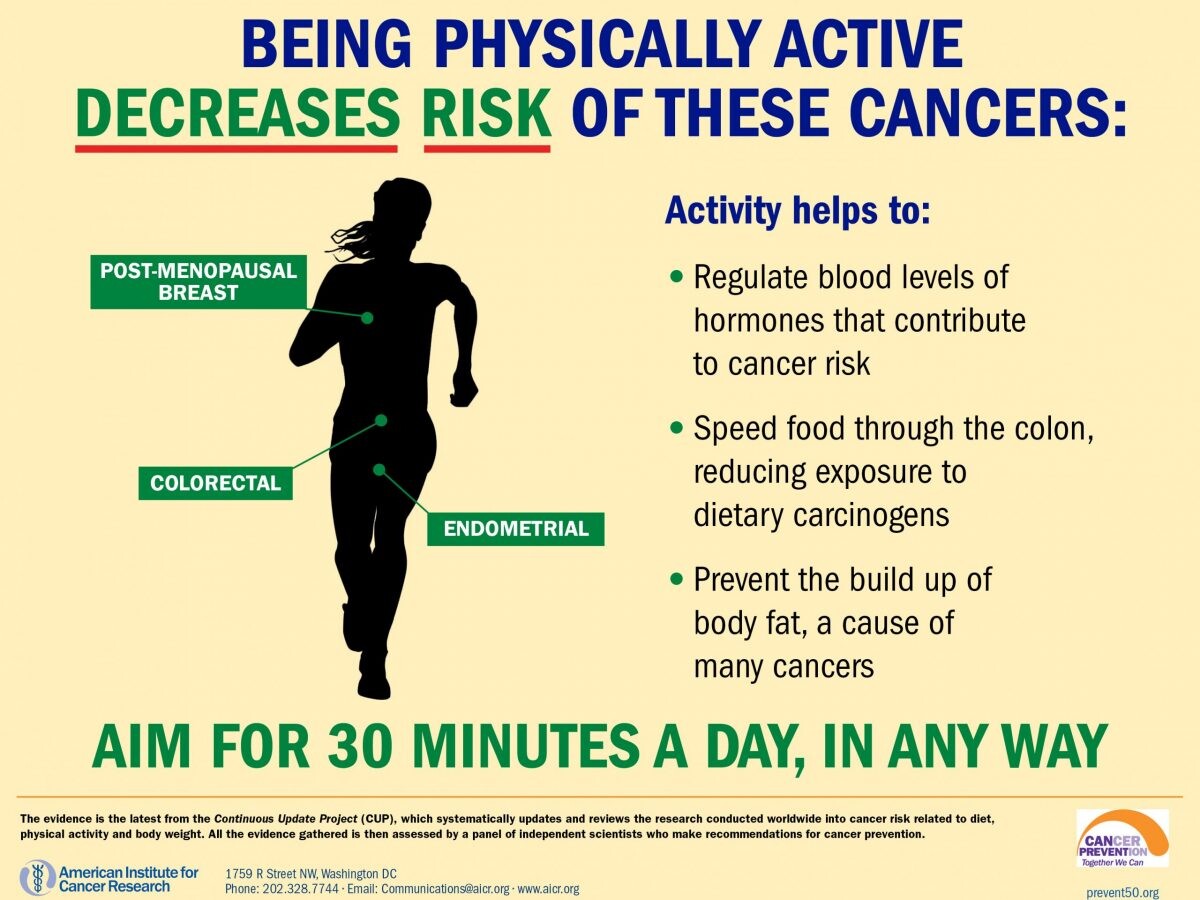

Additionally, running improves your overall health by warding off all kinds of medical issues. “It’s heavily supported that increasing aerobic capacity through running has been linked to decreases in incidence of many health conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, and some forms of cancer,” says Horan. Plus, “recreational running on a regular basis also creates favorable conditions for bone formation, which leads to increased bone mineral density and decreased risk of fractures.”

Even slow, short runs have fantastic health benefits. One study that followed more than 55,000 Americans over 15 years found that those who ran less than a 10-minute-per-mile pace for five to 10 minutes a day had significantly reduced risk for all causes of death.

So even if you come to running for the calorie burn, there are good reasons (lots of them!) to keep coming back for an all-over health boost.

Login to leave a comment

How to Avoid Leg Cramps while Running that Slow You Down

Leg Cramps while Running

Runners can avoid the most common injury of muscle cramping if they tried. These cramps develop mostly in their lower legs and feet. The effects can be debilitating, especially when you are experiencing them for the first time. Learn more about this problem and a few tips to become a better runner while avoiding cramps.

Stretch Before You Go

Many sports require their participants to be lean and flexible, and running is no different. Stretching helps to loosen the muscles in your legs, arms and back. Even people who have naturally stiff, rigid legs can run farther after a few stretches. Muscles that are used more often are less likely to tear. So people who do not exercise regularly are more likely to get cramps.

To improve your running performance, turn stretching into a routine. Perform quick, five-minute stretching exercises that take no more than 10 minutes to complete. Perform these exercises right before you begin running. Once you’ve finished, it’s optional to stretch your muscles again.

Stay Hydrated

Staying hydrated is necessary to maintain a normal body temperature and remain cool while you’re running on hot days. Dehydration occurs when you run for long periods without drinking water. To remain hydrated, drink long sips of water before, during and after your running sessions.

Some people choose to drink an hour or two right before they start running. Some runners add salt to their water. Sodium from the body is lost through sweat as you run. These “salt shots” are supposed to make up for this loss and keep the body in proper balance.

Why are Electrolytes So Important?

For people who cannot carry around salt or ten bottles of water, consuming an SOS electrolyte drink is the easiest way to hydrate yourself. SOS Hydration contains the right mixture of healthy fluids and sodium that your body needs to stay in top performance. Regular water alone is not enough. Also read: What are Electrolytes.

The sodium that you lose in your sweat could lead to muscle cramps in the end. Losing too much sodium is dangerous for runners and athletes in particular. An electrolyte drink (SOS) contains 330mg of sodium, on average, for every eight ounces (236.59 mL) of water along with 195mg of potassium for good muscle contractions.

Avoid Certain Foods or Drinks

There are some habits to avoid before you run. Know that a caffeinated soft drink is the worst choice for runners as it contains high amounts of sugar. Consuming too much sugar at once has good and bad effects on the body. At first, you may feel a boost of energy, but sodas and juices increase your risks of tooth decay, diabetes or obesity.

Start Out Slowly

Another reason why cramps may occur is because the body is not prepared for intense workouts. This happens to people who have not exercised for long periods of time. They have the right attitude but assume that their bodies are naturally fit and healthy. As a new runner, you cannot perform an endless series of sprints when you haven’t gotten used to jogging yet. Build up your running slowly and take it one step at a time. Listening to your body while running is an incredibly important skill.

Have Rest Periods

Cramping occurs to runners who do not rest properly. Even experienced runners run into problems when they overuse their bodies. They begin to overstretch their muscles and risk injuries, even after years of experience. Allow your body enough time to rest in between sessions and rebuild its muscular strength. Most fitness experts suggest that runners have at least one day of rest every week to allow your body to recover for your next run.

From sports doctors, one of the most popular complaints involves muscle cramps, swelling and stiffness. Anyone who has fallen behind on exercise is likely to get cramps. However, some of the best runners have occasional cramps when they miss a few steps in their routines. Stretch, stay hydrated, consume electrolytes and get enough rest to get the best results from your running.

by Sos Hydratation

Login to leave a comment

Does running really help you live longer?

Running is often hailed as a fountain of youth, with promises of extended lifespan, reduced risk of chronic diseases and improved mental health. But can hitting the pavement really help you live longer (and by how much)? A recent large-scale study explored the relationship between different sports and longevity, offering insights into whether running—and other physical activities—actually add years to your life.A global look at sports and lifespan

Researchers out of the European Research Institute for the Biology of Ageing analyzed data from over 95,000 athletes across 183 countries, representing 44 different sports disciplines. They aimed to discover how various sports impacted lifespan by comparing athletes’ ages at death with those of the general population. The study was primarily male-dominated (95.5 per cent of the data), but it provided some fascinating insights into which sports extended lifespan the most.

Interestingly, the results varied widely depending on the sport. Aerobic activities like running, known for improving cardiovascular health, were expected to have positive outcomes. But how did running compare to other sports, and what were the key takeaways?

Does running really extend your life?

In this study, running wasn’t singled out as the top sport for extending lifespan, but aerobic and mixed sports consistently showed a positive impact on longevity. This makes sense given the well-known cardiovascular benefits of running, including improved heart health, better blood circulation and a lowered risk of conditions like stroke or hypertension. According to the study, running helps boost endurance and overall health, both crucial factors in longevity.How other sports stack up

While running is great for your heart, other sports like pole vaulting and gymnastics had the biggest positive impact, with athletes gaining up to 8.4 extra years of life. On the other hand, sports like volleyball and sumo wrestling were linked to a reduction in lifespan, possibly due to high physical strain or weight-related factors in those sports. Mixed sports that combine aerobic and anaerobic exercise, like rowing or tennis, also showed significant benefits, particularly in extending the lifespans of both male and female athletes.Why running helps

Running’s benefits likely come from its aerobic nature. Aerobic exercise improves the body’s ability to use oxygen efficiently, which boosts heart health and endurance. This, in turn, helps reduce the risk of chronic diseases like diabetes and heart disease—two major contributors to early death. Studies also show that runners tend to maintain better body composition, stronger bones and reduced inflammation, all of which contribute to living longer and healthier. Should you add gymnastics training or pole vault practice to your running routine? Well, that part is up to you.

by Running Magazine

Login to leave a comment

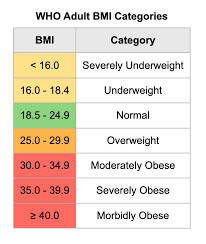

BMI Is a Controversial Measure of Health Outcomes—a New Study Suggests a Better Method

It’s not all about height and weight.

New research suggests incorporating waist circumference into how we predict health outcomes, instead of relying on BMI.

Study authors say BMI does not take into account muscle mass or the links between abdominal fat and poorer health, among other downfalls of the measurement.

In an effort to understand how body composition affects health, most medical professionals and researchers still use the body mass index (BMI), but this has always been a problematic and controversial method when actually applied to individuals, rather than large populations. For example, commentary in the British Journal of General Practice, published back in 2010, called use of BMI unethical, overly simplistic, and potentially harmful to a significant proportion of patients.

A new study in JAMA Network Open assessed a possible pivot toward a different measurement tool: the body roundness index, or BRI. In addition to weight and height (which is all that the BMI includes), the BRI considers waist circumference because that can more comprehensively reflect visceral fat distribution, according to the study’s lead author Xiaoqian Zhang, M.D., at Beijing University of Chinese Medicine in China.

In the cohort study involving nearly 33,000 U.S. adults, researchers looked at the association between an increase in BRI from 1999 to 2018 and the significant rise in all-cause mortality (particularly cardiometabolic disease, kidney disease, diabetes, and cancer) during the same period.

More abdominal fat has been linked to higher risk of these conditions because this type of fat is often visceral, which means it wraps around your organs instead of sits just under the skin. That means it can increase inflammation and drive more chronic diseases, Zhang told Runner’s World. For example, one study of Korean adults found those with normal body mass index had more cardiovascular risk factors if they carried excess abdominal obesity.

“Because of the way it includes waist circumference, BRI effectively provides a more accurate indication of health problems related to being overweight or underweight,” Zhang said. “We found both the lowest and the highest BRI values are associated with significantly increased risks of all-cause mortality.”

The Problem with BMI

Considering a switch away from BMI involves understanding why this effort matters. BMI was not meant to be used on an individual level. It relied only on Belgian men (because it was a formula devised in the 1830s by a Belgian mathematician) and did not take women and/or non-Caucasians into account, the British Journal of General Practice authors noted. As other researchers note, it was also not meant to inform medicine or predict health outcomes

By looking only at height and weight, the BMI might measure general obesity but it doesn't distinguish body fat from muscle mass, said the recent study’s co-author Wenquan Niu, Ph.D., at the Center for Evidence-Based Medicine in China. Because of this, for example, many bodybuilders are classified as obese.

“Fat distribution and body composition can vary dramatically among individuals who have the same BMI,” he told Runner’s World. “That’s why we need a more accurate indication of health problems related to overweight or underweight. Using the BRI is more helpful for this, given the limitations of the BMI metric.”

What to Know About Waist-to-Hip Ratio

The BMI and BRI are not the only possibilities when it comes to body composition. One that’s easy to measure at home is hip-to-waist ratio (WHR), which involves measuring both of those and then dividing your waist number by your hip number. According to a study published in JAMA Network Open in 2023, the ideal ratio for most men is below 0.95 and under 0.85 for women.

Even if you’re physically active and are not overweight, the WHR can help identify your risk of future metabolic issues, because abdominal fat plays a significant role in issues like insulin resistance and hypertension, according to Vitor Engrácia Valenti, Ph.D., a researcher at Sao Paulo State University in Brazil who has done work on body composition.

“The BMI calculation is far less helpful than your WHR, which can give you an indication of whether your waist circumference is outside the normal range,” he told Runner’s World.

Other indicators of body composition are lean muscle mass and fat mass, but those require specialized equipment such as a DXA scan for accurate numbers, Valenti added.

In general, the goal shouldn’t be reducing body fat as much as possible—you do need body fat for overall health—but to focus on reduction of abdominal fat in particular.

Although “spot training” for this type of fat is not a possibility, a systematic review and meta-analysis published in Advances in Nutrition looked at 43 studies focusing on training styles and their effects. Researchers found that although aerobic exercise tends to produce slightly greater efficacy in decreasing belly fat, the biggest change comes when it’s combined with resistance training.

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

All the Benefits You Gain from Walking, Even if You Don’t Hit 10,000 Steps

Putting one foot in front of the other can help you live a healthier, happier life.

In the age of biohacking and complicated training protocols, it’s a good idea to periodically circle back to basics and remind yourself that exercise doesn’t need to be complicated to be effective. Sometimes, the best type of movement is the simplest, and it doesn’t get simpler than walking.

Yes, walking—the same physical activity you’ve been performing since toddlerhood. Back then, putting one foot in front of the other and moving your body from point A to point B was a thrill. Truthfully, you may never fully tap into that feeling of unencumbered freedom or primal joy again. Nevertheless, understanding the physical and mental health benefits of walking may inspire you to up your daily step count or squeeze in a quick stroll after dinner.

To convince you to do just that, we looked at the research and chatted with health and fitness experts for their thoughts on the benefits of walking. The next time you bump up against some confusing health advice or feel too overwhelmed to work out, consult this list. Then go for a walk.

1. Blood Sugar Stabilization

Consistently, research has shown that even a leisurely 10-minute stroll after dinner can help regulate blood sugar levels.

“The food that you eat is broken down in the stomach. Some of that gets broken down into different simple sugars and then sent to the bloodstream, and then that can be utilized in the muscles,” Todd Buckingham, Ph.D., exercise physiologist at PTSportsPRO in Grand Rapids, Michigan, tells Runner’s World. “Walking can help stabilize the blood sugar levels and not get that spike immediately after eating because the muscles are being activated and are going to uptake blood glucose.”

While even slow walking will do the trick, there is some evidence that picking up your pace may further mitigate the risks of type 2 diabetes. The findings of a systematic review published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine suggest that the faster you walk, the greater the benefits. According to the included studies, frequently walking at a casual pace (less than two miles per hour) was associated with a disease risk reduction of around 15 percent. A faster “brisk” pace of between three and four miles per hour was associated with a 24 percent lower risk, and an even quicker pace was linked to a 39 percent risk reduction.

2. Better Sleep

Walking, a low-impact exercise you can do daily, is “the single best way to improve sleep quality,” Michael Breus, Ph.D, clinical psychologist, sleep medicine expert, and founder of The Sleep Doctor, tells Runner’s World.

In simple terms, walking tires the body and increases the naturally increasing pressure to sleep throughout the day. Research shows that physical activity also increases melatonin, a sleep-promoting hormone, regulates body temperature, and can help reduce stress, which can negatively affect sleep.

If you’re having trouble falling asleep, Dixon recommends swapping your before-bed scroll sessions for an evening stroll at dusk. “Walking at night can be especially helpful when it comes to falling asleep. Natural light and avoiding screen time tell your body that it’s time to wind down,” he says.

3. Healthy Weight Maintenance

“The amount of calories burned while walking depends on the speed and distance, but any amount of calories burned can help with your goal of maintaining or losing weight,” William Dixon, M.D., co-founder of Signos and Clinical Assistant Professor at Stanford School of Medicine tells Runner’s World

In one study published in the Journal of Exercise Nutrition and Biochemistry, clinically obese women who participated in a 12-week walking program (50 to 70 minutes of moderately intense walking three days a week) lost abdominal fat and showed improvements in their fasting glucose levels. Members of the control group, all of whom maintained a sedentary lifestyle, exhibited no significant changes.

4. Stress Relief and Mood Regulation

There are reasons why taking a walk to “clear your head” actually works. “Walking can help with emotional regulation,” Craig Kain, Ph.D., a psychologist and psychotherapist based in Long Beach, California tells Runner’s World. “At times, our feelings get the best of us, and we find ourselves off-balance emotionally. Walking can increase levels of two neurotransmitters, dopamine, the ‘happy hormone,’ and decrease levels of cortisol, the ‘stress hormone,’ restoring our brains to a state of equilibrium.”

Kain notes that a regular walking routine can provide over-stimulated people a “time-out” for quiet self-reflection or allow isolated individuals to connect with others in their community. “A client of mine was depressed and housebound after COVID. Walking helped them gain confidence and a sense that they fit into the world again,” Kain says. “By just walking through their neighborhood, they began to feel less fear of other people. They loved dogs and began to say hello to the dogs and owners they saw along the way. Soon, their depression began to lift, and they looked forward to their walks, which became a daily practice, and [it inspired] the feeling of belonging in society.”

5. Reduced Risk of Dementia

Some research shows that getting in your daily steps—right under 10,000 is ideal—is associated with a reduced risk of dementia. But even less than half that amount could make a positive effect, according to a study published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

The authors of the cross-sectional study found that participants who walked at least 4,000 steps a day exhibited better cognitive functioning and had thicker medial temporal lobes (a part of the brain associated with memory) than individuals who accumulated fewer steps. Exactly how physical activity influences brain health isn’t entirely clear, but the authors suggest that the theory of “adaptive capacity model” may be at play.

“This model suggests that during aging, the brain responds adaptively by diminishing capacity so as to reduce energy costs, leading to age-related regional brain atrophy and associated function,” they write. “Engaging exercise in late life can adaptively increase capacity, thus reducing the impacts of cognitive aging.”

“As a therapist who is very aware of the toll dementia takes on individuals, families, and extended families, 4,000 steps seems one of the best preventative mental health actions one can take,” Kain says.

6. Boosted Recovery

While walking is accessible, beginner-friendly, and appropriate for older adults, it can also benefit athletes and individuals who enjoy intense exercise.

“Personally, I like to use walking as a recovery tool,” Buckingham says. He explains that walking helps facilitate blood flow, which can help clear the byproducts of a tough workout and promote the repair of damaged muscle fibers. Walking can also help reduce postworkout swelling.

Dixon notes that some avid exercisers, especially those who prefer high-intensity activities, are often inactive (or even sedentary) during the other 23 hours when they’re not in the gym. “Walking is an easy way to increase your exercise when you might be too tired for another tough workout,” he says.

7. Inspiration to Move More

In and of itself, walking is an excellent use of your time, as evidenced by all the aforementioned benefits. But you may find that consistently hitting your daily step target leads to setting (and conquering) even more ambitious goals.

“I think one of the biggest [benefits of walking] is that it just gets people used to committing to physical activity,” Dixon says. “Often this encourages them to choose behaviors we know are healthy in other aspects, like sleeping more and making healthier diet choices.”

8. Easy to Stay Consistent

Compared to other types of exercise, walking has very few barriers to entry. It doesn’t require an expensive gym membership or sports equipment. You don’t need any special skills or training, and even those new to exercise or navigating health challenges can usually walk. “It’s low-impact, so you’re not going to get stress on the knees, ankle, and other joints that you might with running,” Buckingham says.

To get started with walking, all you really need is a pair of comfortable shoes. “Heck, you don’t even need a pair of shoes. You can walk around barefoot. Go for a walk on the beach,” Buckingham says. New walkers can start with a leisurely walk around the block and gradually add distance or pick up the pace.

Finally, unlike other workouts, you can easily incorporate walks throughout your day—every walk doesn’t have to feel like a workout. You can walk while you take a phone call or during a lunch break. If you don’t have time for one 30-minute walk, you can split it up into two 15-minute walks or three 10-minute walk breaks.

With a little planning, walking can become part of how you connect with friends, family, or pets. “I take my dog for a walk around the block, and we go for a walk around the block with family after dinner just to talk and get outside,” Buckingham says.

Login to leave a comment

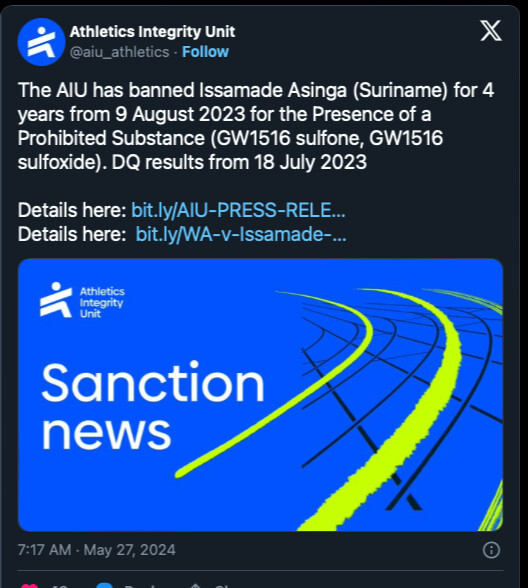

Suriname sprinter blames Gatorade for positive doping test

On Monday morning, Surinamese sprinter and current world U20 100m record holder Issam Asinga was issued a four-year doping ban by the Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU) after testing positive for the metabolites of GW1516 in an out-of-competition test on July 18, 2023. Asinga and his agent claimed the positive test resulted from ingesting Gatorade Recovery Gummies, which were given to him after he won the Gatorade U.S. Boys Track and Field Athlete of the Year award last July.

A few weeks later, at the South American Athletics Championships in São Paulo, Brazil, Asinga set a new U20 100m world record of 9.89 seconds, only to be provisionally suspended two weeks later, just before the start of the 2023 World Athletics Championships in Budapest.

GW1516 was originally developed to treat obesity and diabetes, but is not approved for human use, due to its carcinogenic effects. It is banned both in and out of competition and is not eligible for a Therapeutic Use Exemption (TUE). A USADA bulletin from 2019 states that GW1516, also known as cardarine or endurobol, has been found in some supplements, despite being illegal.

Asinga claimed he took gummies from Gatorade that were supposed to help with recovery. He said two containers of the gummies revealed the presence of the banned substance, but the AIU panel stated he did not show proof that the gummies were the source of the drug found in his sample.

According to the AIU, Asinga claimed he took the Gatorade gummies the week before the positive test, and that subsequent testing of two unsealed containers of Gatorade gummies, provided by the athlete, revealed the presence of GW1516 and GW1516 sulfoxide. “The Disciplinary Tribunal found that Asinga did not satisfy his burden of proof to establish that the Gatorade Recovery Gummies were the source of the GW1516 metabolites detected in his sample.”

In making its decision, the AIU Disciplinary Tribunal stated that the Gatorade recovery gummies provided in unsealed containers by the athlete for testing contained significantly more GW1516 on the outside than on the inside, which practically excludes any contamination by raw ingredients during the manufacturing process. They also noted that the gummies were batch-tested by the National Sanitation Foundation (NSF), and that a sealed jar of the Gatorade recovery gummies, from the same batch taken by Asinga, tested negative for GW1516.

The 19-year-old sprinter plans to appeal the ban, which would take the case to the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) in Switzerland.

All of Asinga’s results from July 18 onward will be disqualified, including his two South American Championships gold medals in the 100m and 200m, as well as his world U20 100m record of 9.89 seconds.

by Running Magazine

Login to leave a comment

Treadmill desks are becoming more popular—but do they help your running performance?

We all know that exercise has a multitude of benefits, and sitting at a desk all day can take a toll on our mental and physical health. It can be hard to get out for a run sometimes, let alone get in our daily step count. Could a treadmill desk be the answer?

Prolonged inactivity is known to increase the risk of heart disease, Type 2 diabetes and other health issues, with the adage “sitting is the new smoking” underscoring the dangers of a sedentary lifestyle. Conversely, walking as few as 4,000 steps a day has been shown to benefit both mind and body. Treadmill desks, which combine a standing desk with a treadmill, offer a potential solution to counteract sedentary office environments, The New York Times recently reported. But are they a worthwhile investment for runners?

Are they effective?

As treadmill desks become more popular, researchers are examining their efficacy. Studies, though sometimes limited in scope, indicate that treadmill desks can help people stay active, potentially adding an average of two extra miles of walking per day. A 2023 study even found that regular use of treadmill desks increased energy levels, improved mood, and in some cases, enhanced job productivity.

Akinkunle Oye-Somefun, a doctoral candidate at Toronto’s York University and lead author of a recent meta-analysis on treadmill-desk research, says that adding small amounts of activity throughout the day can accumulate. He cautions: “walking on a treadmill desk is a supplement, not a replacement for your regular exercise routine.” In other words—while a treadmill desk may boost training by enhancing your mood and adding to time spent on your feet, it’s not a replacement for your regular running routine.

Be mindful of cost

While treadmill desks can increase daily movement, they come with potential drawbacks. Noise is a significant issue, especially with standard running treadmills—the motor and the sound of footsteps can make it difficult to concentrate, both for the user and their co-workers. Quieter models tend to be more expensive, with treadmills and walking pads running from $280 to $1,400.

Taking those Zoom meetings can be a little challenging if you’re trying to speedwalk, and fine motor skills take a hit: Jenna Scisco, an associate professor of psychology at Eastern Connecticut State University and lead author of a 2023 study on treadmill desks, found that typing becomes more challenging while walking. Despite this, she noted that the health benefits often outweigh these drawbacks.

Build a consistent routine

Let’s face it—a walking desk won’t help you race to your next PB… directly. However, building a daily routine of getting more consistent exercise will make you fitter, and you may find yourself pushing through distance and effort barriers with more ease. While adding a lunchtime walk is still a good option if you’re limited by cost or office dynamics, establishing a regular routine on a treadmill desk can be an effective way to add more movement to your day. Experts suggest starting small, with 30-minute increments, before spending longer periods of your work day moving your legs.

by Keeley Milne

Login to leave a comment

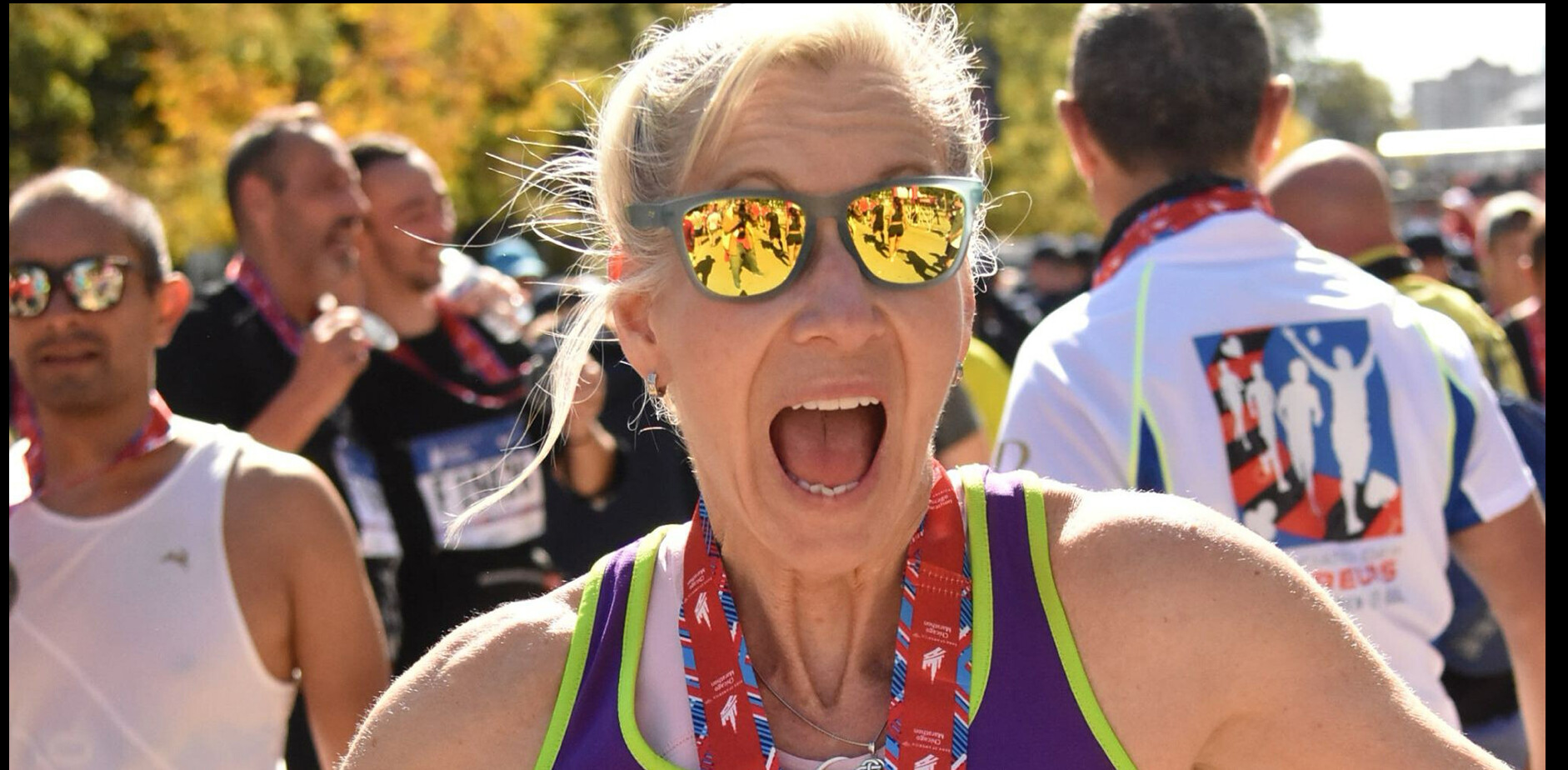

She Qualified for Boston by Doing the Majority of Her Running in Water

Running changed my life trajectory. Before I started running, I had a job as an executive in fast-food marketing. After I started, I changed my career course to focus on health and fitness. I became a certified personal trainer via the American Council on Exercise (ACE) in 2008. In 2011, I became a USA Track & Field run coach, certified Aquatic Exercise Association instructor, and then created Fluid Running as a result for my passion of water running.

I started running 5Ks and 10Ks, but then signed up for a marathon. I ran my first marathon, the Chicago Marathon, in 2001. Then in 2002, I ran the Chicago Marathon again and qualified for Boston. I was hooked. I followed Hal Higdon’s plans exclusively for my first 12 marathons that I ran between 2001 and 2009, and still reference him.

However, in 2010, I was training for the Chicago Marathon with my siblings, and raising money for the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation in honor of my nephew. Six weeks before the race, I tore my calf muscle and my doctor told me I could not run. I was devastated, yet determined.

I searched “how do you stay in running shape when you can not run,” and came across an article on aqua jogging, and contacted the author who is a running coach. His associate gave me a training plan that included five runs a week in the pool, including my 20 miler! I ran solely in the water for the final six weeks of marathon training.

After I discovered pool running in 2010, I would still reference Hagdon’s plans, but I would replace two to three of the land runs on the schedule for water runs.

For pool running, I wear a flotation belt which allows me to run as if I were on land. I am upright in the pool with my legs underneath me. I keep my head held high, shoulders pulled back, and my arms swing by my side. My legs mimic land running form but with a little more “sweepy” back and forth motion.

For the 2022 Chicago Marathon, I decided to try a Track Club Babe training plan because I liked lower mileage, and I focused on speed and slower long runs. I only did the long run and one speed work run on land. The rest I replicated in the pool, and I still qualified for Boston!

Since discovering pool running, my last six marathons have been a combination of about 50 percent pool and 50 percent pavement.

This was my “aha” moment, and I wanted to share my journey, so I created Fluid Running in 2011. A huge benefit is that there is absolutely no impact on the body, so you can do it with many common injuries.

In my recent training for the 2024 Boston Marathon, I did two or three land runs per week (which includes a speed session and the long run), the rest of my running in the water.

I honestly don’t know what I would do without running in my life! It’s my moving meditation. I started dating my husband through running, made many friends, and ultimately created Fluid Running because of it.

These tips have made my running journey a success:

1. Strength train

I’m a huge fan of strength training, especially as we age. I do two sessions a week focusing on my leg muscles and core. I do a lot of single-leg exercises. I know this has played a huge role in keeping me strong, especially toward the end of marathons.

2. Adopt positive self talk

I’m a big believer in positive self-talk. I talk to myself constantly during my runs. One of my mantras that I will say over and over when I run is “strong legs, strong mind, strong body.” “Yes you can” is another one I say often.

3. Learn from your setbacks

I’ve had some setbacks, like all runners. Setbacks, though, are when I ultimately become better and stronger. Setbacks allow me to reflect, and they make me realize just how much I love and need running in my life! Setbacks are temporary, so don’t stress out about them.

Jennifer’s Must-Have Gear

→ SPI Belt: I love it because it’s comfortable and holds so much—my phone, my airpods, gum, and a gel!

→ Power Plate Vibrating Roller: I love it because it gets so deep and feels so good. I try to use it both before and after my runs.

→ Goodr Sunglasses: I love them because they are light, cute, and they make everything look deeper in color. The sky is so blue when I wear them!

Login to leave a comment

Plant-based perfection: super snacks for runners

These nutritious and easy-to-make snacks are perfect grab-and-go fuel for busy days.

Whether you already enjoy a plant-based diet, are curious about trying more plant-based nutrition or are simply looking for some fast, healthy snacks for pre or post-run, we’ve got you covered. Runners can successfully fuel with a variety of different styles of eating, but plant-based nutrition is becoming more popular among elite athletes and regular runners—the shift in eating is credited with lowering inflammation levels, improving cardiovascular health and preventing diseases like Type 2 diabetes. Here are a few delicious recipes to fuel your next run.

Sweet Potato and Oat Muffins

Enjoy these delicious sweet potato and oat muffins as a nutritious snack before or after (or during) your run. Store any leftovers in an airtight container at room temperature for up to three days, or store in the freezer.

Ingredients

1 cup mashed sweet potato (about 2 medium sweet potatoes, cooked and mashed)1/4 cup unsweetened applesauce1/4 cup maple syrup or agave nectar1/4 cup almond milk (or any plant-based milk)1 tsp vanilla extract1 cup whole wheat flour1 cup rolled oats1 tsp baking powder1/2 tsp baking soda1 tsp ground cinnamon1/4 tsp ground nutmeg1/4 tsp saltOptional: 1/4 cup chopped nuts or seeds for added texture

Directions

Preheat your oven to 375 F (190 C) and grease a muffin tin or line with paper liners. In a large mixing bowl, combine mashed sweet potato, applesauce, maple syrup, almond milk and vanilla extract. Mix until smooth.

In a separate bowl, whisk together whole wheat flour, rolled oats, baking powder, baking soda, cinnamon, nutmeg and salt.

Gradually add the dry ingredients to the wet ingredients, stirring until just combined. Be careful not to overmix. If using, fold in chopped nuts or seeds. Spoon the batter into the prepared muffin tin, filling each cup about 3/4 full.

Bake for 20-25 minutes or until a toothpick inserted into the centre comes out clean. Allow the muffins to cool in the tin for a few minutes, then transfer to a wire rack to cool completely.

Scott Jurek’s Rice Balls (Onigiri)

These are a favourite of ultrarunning legend Scott Jurek, from his book Eat & Run.

Ingredients

2 cups sushi rice4 cups water2 teaspoons miso3–4 sheets nori seaweed

Directions

Cook the rice in the water on the stovetop or using a rice cooker. Set aside to cool.

Fill a small bowl with water, and wet both hands so the rice does not stick. Using your hands, form ¼ cup rice into a triangle. Spread ¼ teaspoon miso evenly on one side of the triangle. Cover with another ¼ cup rice.

Shape into one triangle, making sure the miso is covered with rice. Fold the nori sheets in half and then tear them apart. Using half of one sheet, wrap the rice triangle in nori, making sure to completely cover the rice.

Repeat using the remaining rice, miso and nori.

Chickpea flour mini quiches

Enjoy these tasty protein-packed mini quiches warm, or wrap them up and eat them on the go.

Ingredients

1 cup chickpea flour1 cup unsweetened almond milk1/2 cup diced vegetables (spinach, bell peppers, onions, mushrooms, etc.)1/4 cup nutritional yeast1 tsp baking powderSalt and pepper to taste

Directions

Preheat your oven to 375 F (190 C) and grease a mini muffin tin. In a bowl, whisk together the chickpea flour, almond milk, nutritional yeast, baking powder, salt and pepper until smooth.

Stir in diced vegetables, and pour the batter into the prepared muffin tin, filling each cup about 3/4 full.

Bake for 15-20 minutes or until the edges are golden brown and the tops are set. Let cool slightly before removing from the tin. Enjoy warm or at room temperature for a protein-packed snack on the go.

by Keeley Milne

Login to leave a comment

Five foods to supercharge your running performance

Winter is the perfect time to introduce these nutrient-dense superfoods into your diet. From supporting immune function to providing sustained energy in the face of brisk temperatures, these foods will not only fortify you against the season’s demands, but will also help you lay the foundation for a resilient and powerful season. Try these simple and delicious recipes to elevate your nutrition and better fuel your runs.

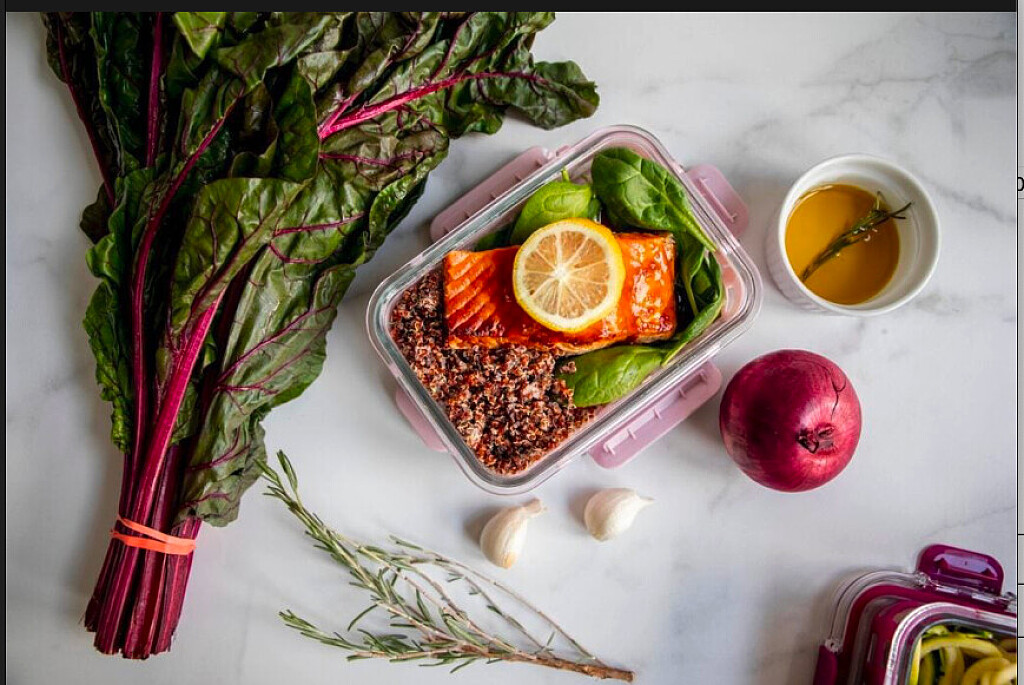

1.- Quinoa

Why it’s a superfood: Quinoa is a complete protein source, containing all nine essential amino acids crucial for muscle repair and recovery. The grain is also packed with magnesium, an often under-consumed mineral that is linked to reduced risk of Type 2 diabetes.

Try: Quinoa Salad with Avocado and Chickpeas

Toss cooked quinoa, diced avocado, canned chickpeas (rinsed and drained), cherry tomatoes, cucumber and feta cheese in a bowl, drizzle with olive oil and lemon juice and season with salt and pepper for a protein-packed and nutrient-rich salad.

2.- Chia seeds

Why they’re a superfood: Chia seeds absorb water to aid in hydration during long runs and are rich in healthy Omega-3 fatty acids. The antioxidants in the seeds are thought to help reduce the inflammation that takes place when muscles suffer micro-tears.

Try: Chia Seed Pudding with Berries

Mix chia seeds with almond milk and vanilla extract, sweeten with honey, refrigerate overnight and top with fresh berries for a delicious pudding that can serve as breakfast or dessert.

3.- Spinach

Why it’s a superfood: Spinach is rich in iron, crucial for oxygen transport to muscles and packed with antioxidants for overall health.

Try: Spinach and Feta Stuffed Chicken Breasts

Sauté chopped spinach and garlic in olive oil, stuff mixture into sliced chicken breasts and season with salt and pepper. Bake until cooked throughout for an iron-packed and protein-rich main course.

4.- Sweet potatoes

Why they’re a superfood: Sweet potatoes provide complex carbohydrates, promote sustained energy levels and are rich in vitamins A and C for immune support. Each potato contains four grams of fat-fighting fibre, and supplies potassium, an electrolyte that helps your body convert carbohydrate to glycogen, to be used as fuel during exercise.

Try: Baked Sweet Potato Fries

Cut sweet potatoes into fry-size portions, toss with olive oil and seasonings of choice (try paprika, garlic powder and salt and pepper), and bake until crispy for a delicious and energy-boosting snack or side dish.

5.- Salmon

Why it’s a superfood: Salmon is loaded with Omega-3 fatty acids, supporting heart health, reducing inflammation and aiding in muscle recovery. It also packs a protein punch and is a great source of vitamin D.

Try: Grilled Lemon Garlic Salmon

Marinate salmon fillets in a mixture of lemon juice, minced garlic, olive oil, salt and pepper, then grill for a flavourful and nutritious pre- or post-run meal.

Incorporating these superfoods into your diet can provide the essential nutrients needed for optimal running performance while supporting endurance, recovery and overall well-being.

by Keeley Milne

Login to leave a comment

6 Running Benefits for Seniors That’ll Convince You to Lace Up Today

Research and experts explain all the advantages you gain from going for a run, including the physical and mental.

Despite what you may have been told, running has no cut-off age. You don’t have to slow down once you hit a particular milestone or switch to low-impact exercise. Running isn’t too hard on an older body, and, no, it won’t wreck your knees.

In fact, the list of running benefits for seniors spans the physical, mental, and social. To highlight some of the most compelling reasons for running well into your golden years, we asked coaches, trainers, and healthcare professionals who work with an older population for their takes. Read on to learn why some of your best miles may be ahead of you.

1. Supports Heart Health

As you age, your risk for cardiovascular disease increases as performance and health-related factors like cardiac output (or the volume of blood your heart pumps per minute), maximal oxygen uptake (a.k.a. VO2 max), and maximum heart rate wane. But research shows that exercise can help decrease your risk of heart disease—and the more active you are, the lower your risk.

“Running won’t stop the decline, and it isn’t for everyone. But done correctly and safely by engaging in a program designed specifically for seniors, it provides a way to slow and mitigate these inevitable declines,” Hiroyuki “Mike” McKnight, coach and founder of Running Workx, a program that specializes in training older adults, tells Runner’s World. “Running consistently over time with higher endurance levels makes the heart stronger and more efficient, especially for those who have been living more sedentary lifestyles during their older adult years.”

Because it’s an aerobic activity, running can improve the heart’s stroke volume (or the amount of blood pumped out of the heart with each contraction), encourage the formation of new blood vessels, and increase the number and size of mitochondria or the “powerhouse” of the cells that help you produce energy.

2. Improves Breathing Function

Lung function, which basically means how well a person breathes, peaks in your 20s and starts to decline around age 35. Combined with age-related sarcopenia (muscle loss and atrophy) of the breathing muscles, namely the diaphragm, can make breathing more difficult and render you more susceptible to respiratory infections, like the flu and pneumonia.

Research shows that moderate to high-intensity exercise, like running, may improve pulmonary function in seniors. A randomized clinical trial involving 45 people, published in Perceptual and Motor Skills, found that participants over 75 who engaged in moderate aerobic activity showed improved forced vital capacity (FVC, a marker of pulmonary health) after a 10-week exercise program. Seniors who performed high-intensity exercise for the same period of time showed improved FVC and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1.0, an additional pulmonary health marker). Meanwhile, the sedentary control group showed no improvements.

3. Increases Bone Density

When it comes to bone density, running is a bit of a double-edged sword. Robert Linkul, C.S.C.S., owner of Training the Older Adult, is quick to point out that the high-impact nature of running may not be advisable for deconditioned seniors with bone density issues. Doing too much too soon could lead to shin splints and other micro-fractures, he warns.

That said, an appropriately progressive training plan that slowly ramps up to running can help improve conditions like osteopenia and osteoporosis. “Ground impact is beneficial, big time,” he says. “You’re getting anywhere between three to six times your bodyweight with ground impact when you’re leaving the ground when you’re striding on a run.”

Todd Buckingham, Ph.D., professor of movement science at Grand Valley State University in Allendale, Michigan, also lists “bone strengthening” among the biggest benefits to senior runners, as it has real implications for quality of life and long-term health outcomes.

Buckingham notes that falls are among the leading causes of injury and injury death for seniors, and hip fractures are associated with elevated mortality. “Increasing the bone density of the hip can help prevent those fractures from occurring,” he says. “Running also strengthens the muscles of the lower body and helps improve balance, so you’ll be less likely to fall in the first place.”

4. Boosts Mood

A run is the ultimate mood booster, especially for older individuals who may be at greater risk for depression. “It’s hard to quantify, but in my experience on the ground, I see running providing seniors with a positive mechanism to cope with the everyday stresses of life,” McKnight says. “Whether it’s before the day starts or at the end of a tough day, there’s nothing like a good run outside to take one’s mind off things and create an environment to enjoy the moment.”