Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #100 mile

Today's Running News

Anne Flower Sets New Women’s 50-Mile World Record at the 2025 Tunnel Hill 50 Mile

In a stunning display of endurance and precision pacing, emergency-room physician and ultramarathon standout Anne Flower blazed to a new women’s world record of 5:18:57 for the 50-mile distance at the 2025 Tunnel Hill 50 Mile in Vienna, Illinois. The mark shatters the previous record of 5:31:56 held by Courtney Olsen, set on the same course last year.

Record-Setting Performance

Held on the flat, crushed-gravel rails-to-trails route of the Tunnel Hill State Trail, the race has become a proving ground for world-class performances. Flower averaged an extraordinary 6:23 per mile (3:57 per kilometer) across the full 80.47 km course, running even splits and showing no signs of strain even as temperatures climbed later in the race.l

From the opening miles, Flower stayed well ahead of record pace, never faltering and closing strongly to seal a performance that redefines the women’s 50-mile standard. Olsen, competing in the 100k event this year, passed the 50-mile mark in 5:33:59—still an elite split, but more than 15 minutes behind Flower’s record pace.

From Marathons to Ultramarathons

Based in Colorado Springs, Colorado, Flower balances her demanding career as an emergency-room doctor with elite-level training. Before moving to the trails in 2019, she competed in marathons and took part in the 2020 U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials. Her road background shows in her efficient stride and disciplined pacing.

Over the past two seasons, she has built an impressive résumé:

Winner of the 2024 Javelina 100k

Champion of the 2025 Silver Rush 50 Mile

Record-breaker at the 2025 Leadville 100 Mile, where she eclipsed Ann Trason’s 31-year-old mark in her debut at the distance

These results paved the way for her dominant performance at Tunnel Hill, demonstrating both her endurance and her remarkable consistency.

Raising the Bar for Women’s Ultrarunning

Flower’s 5:18:57 isn’t just fast—it’s a historic leap forward. Taking more than 12 minutes off a world record at this level is rare, and doing so with such control underscores her potential for even greater achievements ahead.

Tunnel Hill has become synonymous with world-record performances, and Flower’s run further cements the race’s reputation as one of the premier venues for ultradistance excellence.

What’s Next

With records now at both 50 and 100 miles, Flower’s next challenge may be defending or lowering her new mark—or shifting her focus toward international championship events. Whatever path she chooses, her rise through the sport has been nothing short of extraordinary.

Anne Flower has proven that it’s possible to balance a demanding professional life with world-class athletic performance. Her blend of discipline, determination, and pure endurance has elevated her into the top tier of ultrarunning’s global elite.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Oz Pearlman: Mentalist and Marathoner with a 2:23:52 Personal Best

Oz Pearlman is most known as a world-class mentalist and entertainer, dazzling audiences with mind-reading feats. While his stage act is about illusions and mind-reading, his running accomplishments are very real and recognized in the endurance community.

Oz has carved out a reputation as an elite runner, with marathon credentials and ultra-endurance performances that prove his strength goes far beyond the stage.

Marathon Credentials

Oz’s personal best marathon of 2:23:52, set at the Philadelphia Marathon in 2014, is a time most competitive runners can only dream of. He’s also posted:

• 2:26:59 at the 2014 New York City Marathon

• 2:29:19 at the 2021 NYC Marathon

• 2:40:14 at the 2022 NYC Marathon

Along the way, he’s notched victories in regional races, including the New Jersey Marathon, underscoring his range and consistency.

From Marathons to Ultramarathons

Oz didn’t stop at 26.2. He’s tested his limits in some of the sport’s toughest arenas:

• 100 miles in 16:53:25 at the Keys Ultra (2021), finishing second overall.

• 100 miles in 18:25:23 at the Umstead 100-Mile Endurance Run (2025).

• 117 miles in Central Park (2022), setting the record for most loops in a single day while raising funds for Ukrainian relief.

• A nonstop run from Montauk Point Lighthouse to Times Square — over 130 miles in 24 hours.

These efforts highlight not only his physical endurance but also his ability to push through the mental barriers that define ultra running.

Mind Over Miles

As a mentalist, Oz has honed a mastery of focus, patience, and mental toughness — qualities that translate seamlessly to distance running. Whether chasing sub-2:25 marathons or grinding through 100-mile ultras, he shows that success in endurance sport comes as much from the mind as from the legs.

Running With Purpose

Many of Oz’s longest challenges have doubled as fundraising efforts, proving that his running is about more than personal achievement. His Central Park ultra raised significant support for Ukraine, reflecting how he uses his talents — both on stage and on the course — to make an impact.

Oz Pearlman is more than an entertainer. He is a reminder that resilience, consistency, and the power of the mind can take us further than we imagine — sometimes all the way from Montauk to Manhattan.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

What Happens When the Finish Line Feels 100 Miles Away

We’ve all seen the footage: a runner, sometimes even an elite, staggering or crawling across the marathon finish line. It’s a powerful image—equal parts dramatic and heartbreaking. But what causes those jelly legs, and can it be prevented?

The Science of “Jelly Legs”

The feeling of wobbly or unresponsive legs at the end of a marathon is often the result of neuromuscular fatigue and metabolic depletion. After 26.2 miles, the body’s ability to send signals from the brain to the muscles can falter.

“You’re not just tired,” says Coach Jimmy Muindi, seven-time Honolulu Marathon champion. “Your legs stop responding to what your brain is telling them to do.”

Key Causes

1. Glycogen Depletion

Muscles run on glycogen, and after two to three hours of running, those stores run dry—especially if fueling is inadequate.

2. Dehydration and Electrolyte Imbalance

Even a small loss in body fluid affects muscle function. Electrolyte imbalances (particularly low sodium or potassium) can trigger cramps and weakness.

3. Central Nervous System Fatigue

Your brain gets tired, too. Prolonged effort reduces the brain’s ability to send strong, coordinated signals to the muscles.

4. Improper Pacing

Going out too fast early in the race can lead to full-system shutdown in the final miles. Your body simply can’t hold that pace.

5. Heat and Humidity

Hot races amplify all of the above. Core temperature rises, making it harder for muscles to function efficiently.

Why It Even Happens to Elites

Elite runners push their bodies to the limit. Sometimes a miscalculation in pace, nutrition, or weather adjustment can bring even the strongest athlete to their knees—literally. And because they’re aiming for peak performance, they’re often operating on a knife’s edge.

In 2018, American runner Sarah Sellers nearly collapsed after finishing second at the Boston Marathon, a race defined by brutal weather. Others, like Gabriela Andersen-Schiess in the 1984 Olympics, became iconic for their final, staggering strides.

Prevention Strategies

• Dial in race-day nutrition. Practice fueling with gels, fluids, and electrolytes during training.

• Train your brain. Long runs, heat training, and race simulations help develop mental toughness and delay central fatigue.

• Know your pace. Use race predictors and experience to avoid going out too fast.

• Hydrate smart. Don’t just drink water—replace lost electrolytes.

Final Thought

Marathon running pushes the human body to its limits. Jelly legs and crawl finishes are not signs of weakness—they’re the body’s emergency brake. With smarter training and fueling, most runners can avoid it. But when it does happen, it reminds us how far people will go to finish what they started.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Meg Eckert Smashes World Record running Over 600 Miles in Six Days

American ultrarunner Meg Eckert has just rewritten the record books. Covering a jaw-dropping 603.156 miles (970.685 kilometers) over six days, Eckert shattered the women’s six-day world record at the 24H World Challenge in Policoro, Italy, making headlines in the ultrarunning world.

The previous record of 576.6 miles (928.1 km) was held by Australia’s Dipali Cunningham, set in 2001. Eckert not only surpassed that mark—she obliterated it with consistent pacing, minimal rest, and an iron will that held up through blistering heat, exhaustion, and the mental toll of running for nearly a full week.

The six-day race is one of the ultimate endurance tests in ultrarunning, requiring not just physical toughness but strategic discipline. Athletes eat, rest, and sleep in short bursts, logging as many miles as possible around a looped course. Eckert averaged over 100 miles per day, an incredible feat. Many runners only average this in an entire month.

Eckert, 42, from the United States, has long been respected in the ultra community, but this performance launches her into an elite tier of historical significance. Her run wasn’t just about physical achievement—it was a showcase of mental strength and deep experience with multi-day racing.

“It was about being in the moment, one lap at a time,” Eckert said afterward. “I knew what I was capable of, but to actually do it… that took everything.”

As more runners continue to push the boundaries of what the human body and mind can handle, performances like Eckert’s redefine the limits of endurance running. Her new world record is expected to stand as a monumental benchmark for years to come.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

One Mile or One Hundred The Battle for the Soul of the Mile in 2025

In 2025, the word “mile” carries very different meanings depending on who’s lacing up their shoes. For some, it’s about blistering speed—the chase for a personal best in an all-out sprint lasting just a few intense minutes. For others, it’s about endurance, grit, and surviving a 100-mile ultramarathon—not once, but four times in one season. While one version of the mile is measured in minutes, the other is measured in days, elevation, and blisters.

Both forms of running are surging in popularity, drawing passionate athletes and growing crowds. But which “mile” speaks to you?

The Rise of the Road Mile

The road mile is back in the spotlight. Once overshadowed by the 5K and 10K, this short, intense race has re-emerged as a fan favorite. In cities across the U.S. and around the world, runners are lining up for high-stakes, high-speed showdowns that test both speed and tactical racing smarts.

One of the most iconic examples is the New Balance 5th Avenue Mile in New York City. Scheduled for Sunday, September 7, 2025, this legendary event draws elite professionals, masters athletes, and youth competitors for a one-mile drag race down Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue. With the skyline as a backdrop and cheering crowds lining the route, it offers one of the purest expressions of speed in road racing.

“It’s raw, it’s electric, and it’s over before you know it,” said one competitor who’s raced both marathons and the mile. “The road mile demands absolute precision—whether you’re aiming to break five minutes or six, you don’t get time to recover from a tactical mistake.”

Events like the Guardian Mile in Cleveland and the Grand Blue Mile in Iowa have followed suit, offering prize money, flat courses, and the kind of short-format excitement that appeals to both spectators and athletes. The mile, once seen as a track-specific discipline, has truly found a home on the road.

The Grand Slam of Ultrarunning

At the other extreme lies the Grand Slam of Ultrarunning—one of the sport’s most grueling and prestigious challenges. Often confused online with terms like “mile grand slam” due to the cumulative 400 miles of racing, the official name is simply The Grand Slam.

To earn this distinction, runners must complete four of the oldest and most iconic 100-mile trail races in the United States during a single summer. The core races typically include:

• Western States 100 (California)

• Vermont 100 Mile Endurance Run

• Leadville Trail 100 (Colorado)

• Wasatch Front 100 (Utah)

Some years permit substitutions like the Old Dominion 100, depending on scheduling. Regardless of the lineup, the difficulty is staggering: thousands of feet of elevation gain, brutal cutoffs, altitude, heat, and sleep deprivation.

“To finish one 100-miler is an accomplishment,” said a veteran ultrarunner who’s completed the Slam. “To finish four in under 16 weeks—there’s nothing like it. It’s not about speed. It’s about survival, strategy, and heart.”

Since its formal inception in the 1980s, fewer than 400 runners have completed the Grand Slam—a testament to its difficulty and prestige.

Two Extremes, One Shared Spirit

At first glance, these two uses of the word “mile” couldn’t be more different. One is sleek and fast; the other is rugged and long. One ends before your legs even start to ache; the other pushes your limits for an entire day—and night.

But at their core, both disciplines require the same fuel: dedication, discipline, and the courage to test yourself. Whether it’s the final lean in a road mile or the final climb at mile 96 of a trail race, runners in both arenas are chasing something personal—and powerful.

Final Thought

So what does the mile mean in 2025? For some, it’s a tactical burn over 1,760 yards. For others, it’s the slow, steady march of 100 trail miles—repeated four times. Either way, the mile remains one of the sport’s most meaningful measures of challenge.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Matt Richtman - The Unexpected Hero of American Distance Running

On March 16, 2025, Matt Richtman stunned the running world by becoming the first American man in 31 years to win the Los Angeles Marathon. His time—2:07:56—was not only a personal best, but also the seventh-fastest marathon time in U.S. history. What made the victory even more remarkable was how he got there: no professional training group, no high-profile coach, just relentless work, self-belief, and a deep-rooted passion for the sport.

Humble Beginnings in a Running Family

Born on January 13, 2000, in Elburn, Illinois, Richtman was raised in a family where running was part of the fabric of life. His parents, Tom and Karen, along with his sisters, Rebecca and Rachel, were known locally as “The Running Richtmans.” Inspired by that environment, Matt began running competitively in middle school and quickly rose through the ranks.

In 2017, as a senior at Kaneland High School, he won the Illinois Class 2A cross-country state title. From there, he ran at Bradley University before transferring to Montana State University, where he earned All-Big Sky honors and became a standout on the cross-country and track teams. He graduated in 2023 with a degree in mechanical engineering.

A Blue-Collar Approach to Greatness

After college, Richtman returned to Illinois to work with his father’s carpentry business and volunteered as a coach at his former high school. Though his path diverged from the traditional elite training pipeline, he continued to train with quiet intensity.

In October 2024, Richtman made his marathon debut at the Twin Cities Marathon, finishing fourth in 2:10:47. That performance earned him a sponsorship from ASICS, allowing him to train full-time. Still, he remained self-coached and based in Bozeman, Montana, where he trained with a small group that included former Montana State teammates.

His training emphasized consistency over flash: weekly mileage exceeding 100 miles, long progression runs, and mile repeats with short recovery. No altitude camps. No super team. Just hard work.

Making History in Los Angeles

At the 2025 LA Marathon, Richtman took control in the late miles and never looked back. He crossed the finish line alone, arms raised, breaking a 31-year drought for American men at this race. It was a breakthrough not just for Richtman, but for American distance running.

In post-race interviews, Richtman humbly credited his support system and years of preparation. His father, watching from the finish line, said it best: “Matt trains every day, rain or snow. He earned this.”

What’s Next?

With his sudden rise to national prominence, Richtman now has his eyes on the global stage. He hopes to represent the United States at future World Championships and at the 2028 Los Angeles Summer Olympics—poetically, back where it all started.

Whether or not he joins a professional group or continues to go it alone, one thing is certain: Matt Richtman has proven that there’s more than one path to greatness. His win in LA was more than just a race—it was a reminder of what’s possible when talent meets tenacity.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

Los Angeles Marathon

The LA Marathon is an annual running event held each spring in Los Angeles, Calif. The 26.219 mile (42.195 km) footrace, inspired by the success of the 1984 Summer Olympic Games, has been contested every year since 1986. While there are no qualifying standards to participate in the Skechers Performnce LA Marathon, runners wishing to receive an official time must...

more...What It Takes to Go Beyond 26.2 - Taking on the Ultra

For many runners, crossing the marathon finish line is the pinnacle of endurance racing. But for an increasing number of athletes, 26.2 miles is just the beginning. The ultramarathon—defined as any race longer than a marathon—has surged in popularity, drawing runners eager to test their limits over 50K (31 miles), 100K (62 miles), 50 miles, 100 miles, and beyond.

But how do you make the leap from marathoner to ultramarathoner? What does it take to conquer these longer distances? Let’s break it down

The Key Differences Between a Marathon and an Ultra

While both require strong endurance, an ultramarathon is a completely different beast from a road marathon. Here’s what sets them apart:

• Pacing Is Crucial – In a marathon, you can push your pace hard and still hold on. In an ultra, going out too fast can be a disaster. Starting conservatively is essential.

• Nutrition Matters More – Running beyond 26.2 miles means your body will need real food, not just energy gels. Successful ultrarunners eat a mix of carbohydrates, protein, and fatto sustain energy levels.

• Trail Running Dominates – Many ultras take place on rugged trails, requiring technical footwork, elevation gains, and varying terrain.

• Mental Fortitude is Everything – Ultramarathons test your mental resilience as much as your physical endurance. Learning to embrace discomfort and keep moving forward is key.

How to Train for an Ultramarathon

1. Build Your Base (Time on Feet > Speedwork)

Training for an ultra isn’t just about miles—it’s about spending long hours on your feet. Instead of focusing on speed, ultra training prioritizes slow, steady endurance.

• Increase Weekly Mileage Gradually – Aim for at least 50-70 miles per week for a 50K and 70-100 miles per week for a 100K or 100-miler.

• Back-to-Back Long Runs – Instead of one long run, many ultra plans include two long runs on consecutive days to simulate running on tired legs.

• Practice Hiking – Even elite ultrarunners hike the steep sections. Practicing power hiking helps conserve energy on climbs.

2. Strength Training & Mobility Work

Ultras put serious strain on your body. Strength training improves durability, while mobility work helps prevent injuries.

• Core Work – A strong core stabilizes you on technical trails.

• Leg Strength – Squats, lunges, and step-ups strengthen the quads, hamstrings, and calves.

• Ankle & Foot Mobility – Essential for navigating uneven terrain.

3. Master Race-Day Nutrition

Unlike marathons, where fueling is simpler, ultramarathon nutrition requires strategy.

• Eat Real Food – Ultras often include PB&J sandwiches, bananas, pretzels, and broth. Find what works for you in training.

• Stay Hydrated & Balance Electrolytes – Dehydration or electrolyte imbalances can end your race early.

• Fuel Frequently – Many ultrarunners eat every 30-45 minutes to avoid bonking.

4. Train for the Terrain

If your ultra is on technical trails, hills, or mountains, training in similar conditions is critical.

• Hill Repeats – Strengthen quads for long descents.

• Technical Trail Running – Practice on rocky or root-filled trails to improve footing.

• Night Running – Many ultras involve running in the dark, so get used to using a headlamp.

Mental Strategies for an Ultramarathon

Running an ultra is as much mental as physical. Even the fittest runners struggle if they aren’t mentally prepared.

• Break the Race Into Sections – Instead of focusing on the total distance, mentally divide the race into aid station segments.

• Have a Mantra – Simple phrases like “Relentless forward motion” or “One step at a time”can help during tough moments.

• Expect Lows—And Know They Pass – Every ultrarunner experiences physical and mental lows, but pushing through leads to new highs.

Choosing Your First Ultra

Not sure where to start? Here are three great entry points into ultramarathoning:

1. 50K Trail Race – A great intro, only 5 miles longer than a marathon but often on trails with varying terrain.

2. 50-Mile Race – A serious jump, requiring race-day nutrition and pacing mastery.

3. Timed Ultras (6-Hour or 12-Hour Races) – Rather than a set distance, these races challenge runners to cover as much distance as possible in a fixed time.

Should You Run an Ultra?

If you love endurance challenges, embrace the grind, and enjoy long hours on the trail, ultramarathoning might be your next big adventure. The transition from marathon to ultra isn’t just about running farther—it’s about running smarter, stronger, and with a mindset prepared for anything.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

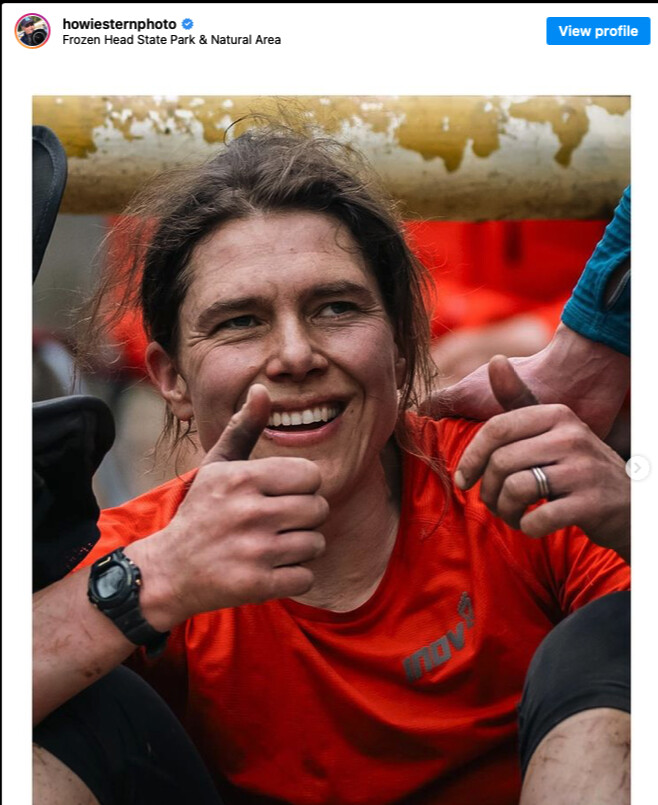

Only one women has ever finished the Barkley Marathons since it started in 1986 - Jasmin Paris

Jasmin Paris cemented her place in ultrarunning history by becoming the first woman to finish the Barkley Marathons in 2024. Known for her endurance and mental toughness, Paris completed the brutal 100-mile course in 59 hours, 58 minutes, and 21 seconds, finishing with just 99 seconds to spare.

A seasoned ultrarunner and former winner of the Spine Race, she battled extreme terrain, sleep deprivation, and navigation challenges to achieve this groundbreaking feat. Her success not only shattered barriers but also proved that women can conquer one of the toughest endurance events ever devised, inspiring runners worldwide.

The Barkley Marathons often called the hardest foot race on the planet has long been a symbol of ultimate endurance in the ultrarunning community Established in 1986 this grueling event challenges participants to complete five approximately 20 mile loops totaling around 100 miles within a 60 hour limit Historically the race has seen a minuscule completion rate with only 15 different individuals finishing between 1986 and 2022

A Surge in Finishers

The 2023 edition marked a significant shift Three runners Aurelien Sanchez John Kelly and Karel Sabbe successfully completed the course Kelly who had previously finished in 2017 was joined by Sanchez a debutant and Sabbe who had come close in prior attempts This uptick in completions prompted discussions about the race’s evolving difficulty

The trend continued in 2024 with an unprecedented five finishers

• John Kelly Secured his third completion reinforcing his status among elite ultrarunners

• Jared Campbell Achieved a remarkable fourth finish showcasing enduring resilience

• Ihor Verys A newcomer who defied expectations with a successful debut

• Greig Hamilton Demonstrated exceptional endurance to join the finishers ranks

• Jasmin Paris Made history as the first woman to complete the Barkley Marathons finishing with just 99 seconds to spare

Paris’s groundbreaking achievement garnered international attention highlighting both her personal triumph and a potential shift in the race’s perceived difficulty

Anticipating the 2025 Edition

The exact date for the 2025 Barkley Marathons remains undisclosed adhering to the event’s tradition of secrecy Historically the race occurs between mid March and early April often aligning with April Fools Day Participants typically receive a 12 hour notice before the start signaled by the blowing of a conch shell by race director Gary Lazarus Lake Cantrell

In light of the recent increase in finishers Cantrell has hinted at making the 2025 course more challenging While specific changes have not been confirmed the goal is to restore the race’s notorious difficulty potentially reducing the number of successful completions

The Barkleys Enduring Challenge

Despite the recent surge in finishers the Barkley Marathons remains an extreme test of endurance navigation and mental fortitude Each year approximately 40 runners are selected to face the unpredictable course with the vast majority unable to complete it As the 2025 edition approaches the ultrarunning community eagerly awaits to see how the race will evolve and who if anyone will overcome its relentless challenges

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

It is amazing that anyone can tackle such a course but they have including the first woman in 2024! - Bob Anderson 3/17 10:21 pm This event is insane and they are going to make the course even harder? - Bob Anderson 3/18 8:40 am |

5 Things Most Marathoners Shouldn’t Worry About

Marathon training can be overwhelming, but some things just aren't worth the stress

With the abundance of marathon training advice available today, figuring out how best to prepare can seem as daunting as the race itself. There are training plans for every ability level, books dedicated exclusively to the subject of marathon nutrition, and accessories for problems you probably didn’t know existed. For someone with limited time to dedicate to the inherently absurd pursuit of racing 26.2 miles, the question may arise: How much of this stuff do I really need to worry about?

Of course, the answer depends on your goals. Anyone looking to qualify for the Olympic Trials will be fine-tuning their training down to the last detail. But for the average marathon runners, it’s easy to miss the forest for the trees.

To help cut through some of the clutter and distill those aspects of marathon training that matter most, we consulted Mario Fraioli, a former collegiate All-American and head coach of the digital coaching service Ekiden. (He also writes a weekly newsletter called the Morning Shakeout.) Fraioli has coached several elite-level athletes, but we picked his brain about what the rest us should be most focused on.

There’s No Magic Marathon Diet

One reason long runs are indispensable to marathon training is that they give you a chance to practice taking in food and drink in a race scenario. When it comes to nutrition-related aspects of marathon prep, figuring out what will work for you in a race is more crucial than worrying about things like “carbo-loading” or trying to find a perfect marathoner’s diet.

Of course, a healthy diet will bolster your chances of racing well, and you’ll need to eat more as you burn more calories, but what constitutes a healthy diet for the average runner doesn’t dramatically differ from a healthy diet in general.

Ingesting gels during the late stages of a race, on other hand, poses a unique challenge that you should prepare for.

“In marathoning, fueling is the X-factor for a lot of people,” Fraioli says, noting that it’s essential to figure out beforehand how your body responds to taking on food after two hours of running. Then there’s the mechanics of it—things like learning to squeeze a plastic cup so you can drink its contents midstride without sending most of it straight up your nose.

“Drinking on the run is something a lot of people, even top pros, struggle with, because they don’t practice it,” Fraioli says.

You Don’t Have to Hit the Track

For most advanced marathon runners, training includes a combination of long runs at or near race pace, as well as short, fast interval workouts. If you can’t fit both into your schedule, it’s best to prioritize the former.

In recent years, fitness media has heralded the benefits of high-intensity interval training, or HIIT, often with the purpose of explaining how the short, fast repetitions can also benefit those preparing for long races. There’s no question that HIIT is a great way to build fitness quickly, but this shouldn’t obscure the fact that, ultimately, long runs are the closest simulation of what you’ll face in a marathon.

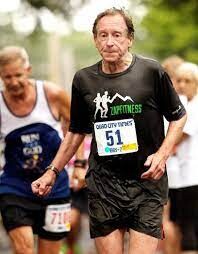

The bottom line is that while you can still achieve a very good result in the marathon without incorporating short intervals into your training, missing your long runs will lead to race-day disaster. (Case in point: 60-year-old 2:45 marathoner David Walters hardly runs any short stuff anymore, but, well, he’s still pretty good.)

“Even for most competitive marathoners who are not elite, they are running somewhere between two hours and 30 minutes and three hours and 30 minutes. That’s a lot of time on your feet,” Fraioli says. “Just from that standpoint, the long run carries a greater importance—so you’re comfortable being out on your feet and running that long.”

Focus on Your Own Training Plan, Not the Pros’

Fraioli has recently noticed a lot of very good amateurs trying to emulate the workouts of world-class runners. This is not a wise approach.

“Some runners look at all these wild workouts—40K at 95 percent marathon pace—and they’ll think, ‘Well, if this is what the top people in the world are doing, I’m going to tailor that to my own training,’” he says. “They don’t always realize that for these athletes, it’s their full-time job, and they’ve built up being able to handle that level of stress over the course of many years.”

Instead of trying to figure out what Galen Rupp is doing, the most valuable training log you can consult is your own. Fraioli has documented his training since his high school running days and says it’s like a personal reference text that provides healthy perspective on his entire running career. Such journals are a both great way to see how far you’ve come and an essential resource when it comes to planning your next training cycle.

Save the Racing Flats for When You Qualify for Boston

Yes, we’ve published articles about the benefit of racing in flats, and there have certainly been exciting innovations on this front, but for the majority of marathoners, the procurement of lightweight racing shoes is literally one of the last things they should be concerned about.

“I think racing flats falls into that last 5 percent,” says Fraioli. “Most people should look to optimize the other 95 percent of training elements first.”

If you’re new to marathoning, it’s advisable to complete a few races in the same running shoe you’re used for training, rather than opting for a lightweight model right off the bat. (For advice on picking the perfect shoe, look here.) Down the line, racing flats can increase running efficiency and help shave a few seconds off your finishing time, but they also offer less in the way of cushioning and support. Think of them as a reward to give yourself after your first breakthrough marathon performance.

Your Training Plan Is a Guide, Not an Instruction Manual

There’s no question that training for a marathon requires discipline, but discipline shouldn’t be confused with dogmatic adherence to a prescribed training plan. When putting together a workout schedule for a future race, it’s impossible to know how you’re going to feel on a particular day, eight weeks into your training. Furthermore, you probably can’t anticipate external factors that can cut into your time, whether that’s a workplace fiasco or sudden snowstorm.

Like elsewhere in life, flexibility is key. Once you accept the fact that you may be able to run only four days in a given week, you can focus on making sure to include those workouts that are most important—for example, the weekly long run mentioned above.

“I think there are too many people trying to cram 100 miles into what for them should be a 50-mile week, rather than thinking about what they should be prioritizing,” says Fraioli.

“You don’t want to chase [mileage] numbers for numbers’ sake. You want to prioritize the training elements that will yield the biggest returns for you, based on how much time you have available.”

Login to leave a comment

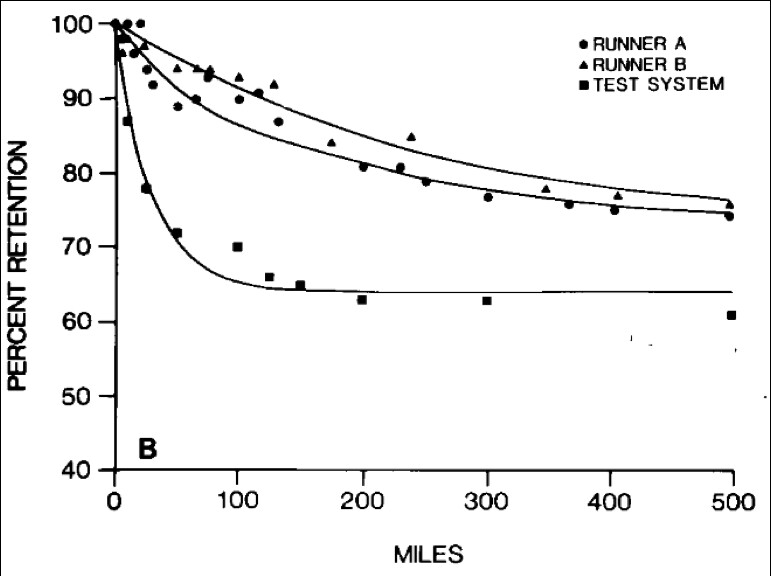

How Much Mileage Should You Run?

Less is not more. More is almost always more—within reason, and with a plan.People complicate it, but running is like almost every other activity. Want to be a good pianist? Practice a lot. Want to be a great surgeon? Cut a lot of people open.In both activities, it is important that your practice has some direction. Mindlessly slamming the piano keys or taking a knife to grandma during her afternoon nap will not make you an expert (nor popular with the neighbors). But in all cases, the common denominator of expertise is time invested.

It took me way too many years to learn this lesson. In summer 2010, I had just graduated college after gradually getting into running over the previous four years. I was running 20 to 30 mostly hard miles per week (along with some biking), thinking I was doing things right. Then, I found a dog-eared copy of the cult-classic novel Once a Runner, and everything changed.

Once a Runner tells the fictional story of Quenton Cassidy, who goes to the woods, trains his butt off, and ends up winning an Olympic medal. It wasn’t the melodramatic prose or poignant narrative that struck me—it was the mileage. Cassidy was running as much in a day as I was running in a week.

After adding a few more dog ears to the book and returning it to the library, I gobbled up every resource on running training I couldAs Cassidy said, “The only true way is to marshal the ferocity of your ambition over the course of many days, weeks, months, and (if you could finally come to accept it) years. The Trial of Miles; Miles of Trials.”What makes running different than activities like the piano is that doing it too much or too hard will result in injury. The injury conundrum makes running unique, and, in my opinion, is the main reason coaches exist. How can we keep you healthy and avoid burnout while maximizing your volume? That question is running training distilled down to its essence.

I’ve written about how to stay healthy before. Cliff notes version: run easy most of the time, practice injury prevention, and eat as hard as you train. But I haven’t confronted the other piece: How much running should you be doing?

How much mileage you should run depends on whether your goal is to finish strong (defined here as being confident that you have done enough training to reach the finish line smiling, even on a bad day) or perform optimally (being confident that you are doing the most you possibly can to reach your running potential). Both are great goals, and both come with different types of sacrifices and planning.To Finish Strong

The general guidelines for finishing strong (and smiling) are below. These mileage totals give you the volume needed to be sure your legs are prepared for racing the distance, with enough training to do the necessary long runs and avoid the race-day trauma that results from running on unprepared legs. (Endurance-based cross training, like biking or Elliptigo, does not count toward total mileage, but can be a valuable addition to a training program.)5K: 10 miles per week (over at least 2 runs)

10K: 15 miles per week (over at least 3 runs)

Half-marathon: 25 miles per week (over at least 3 runs)

Marathon: 30 miles per week (over at least 4 runs)

50 miles: 40 miles per week (over at least 4 runs)

100 miles: 40 miles per week (over at least 4 runs)

Longer races require more volume, and more volume requires more runs per week; concentrating too much mileage in too few runs increases injury risk.

At this level, 100 miles requires the same volume as 50 miles, because in those races, you will be stepping into the deep, dark abyss of the unknown no matter what. So if you are just aiming to finish strong, it is more important to focus on key long efforts (and pray to the ultra-gods profusely for their favor).

To Perform OptimallyPerformance is a tricky, deceiving monster. Much of elite performance is dictated by choosing the right parents. Therefore, we aren’t talking about absolute race performance here, but personal performance relative to genetic capabilities.

The numbers below represent peak sustained volume, or the highest volume you will achieve and sustain for at least a month during hard training.

This formulation is overly simple—you should work up to this volume slowly over time, building a base then adding workouts and modifying total volume based on periodization principles. Remember, volume comes with diminishing returns and is highly individual, so be careful not to run too much for you.

5K to 10K: 6 to 12 hours per week

Half-marathon to 50K: 7 to 15 hours per week

50 to 100 miles: 8 to 16 hoursThat is quite the range, but gives you an idea of the numbers you want to work toward over time. The lower end is for injury-prone or time-crunched runners, especially those who have not run high mileage previously.

These numbers are in time (rather than distance) to account for variances in terrain—steeper, more technical trails are slower, but have a similar aerobic stimulus. Finally, these numbers go out the window for older runners—injuries are more likely for runners in their 50s, 60s and 70s.

A less accurate but clearer way to picture it is in optimal miles per week, assuming non-technical terrain and a consistently durable runner:

5K to 10K: 50-70 miles per week (women), 70-90 (men)

Half-marathon to 50K: 60-90 (women), 70-110 (men)

50 to 100 miles: 60-110 (women), 80-120 (men)If you’re anything like me when I first started learning about training, you may be saying, “That is a lot of mileage!” Good. That is the point of this article—being an expert takes a lot of time, and it’s essential to acknowledge it whether you are a runner or a pianist.

Still, these numbers are not hard-and-fast rules, just guidelines. Just because you can’t reach these numbers doesn’t mean you won’t be amazing at running.

Remember, never increase mileage by more than 10 percent in a week (and 3 to 5 percent if you’ve never run higher mileage before). It took me two years to go from 20 to 30 miles per week to 90 miles per week.

No matter what, always be extremely attentive to injury. Staying healthy is the most important part of running, and durability is a talent in its own right.

There may be shortcuts to good (or even great) performance, but there are no shortcuts to your best performance. Plan for the long term, methodically increase volume and do smart workouts once or twice a week after you have a solid running base.

To put it another way, it’s all about the

Login to leave a comment

In His First 100-Miler, David Roche Demolishes the Legendary Leadville 100 Course Record

Matt Carpenter’s record stood for 19 years.

In his first 100-mile race of his career, trail runner and coach David Roche took down a legendary record in the sport. On Saturday, the 36-year-old broke Matt Carpenter’s storied Leadville 100 course record from 2005, winning in 15:26:34—over a 16-minute improvement of the record.

Roche won the men’s race by 30 minutes, on the dot. Adrian Macdonald was second in 15:56:34, and Ryan Montgomery placed third with a time of 16:09:40. In the women’s race Mary Denholm dominated, winning in 18:23:51. Zoë Rom took runner-up honors (21:27:41) while Julie Wright rounded out the podium in 21:48:57.

The Leadville course is notoriously difficult, primarily due to its situation at high altitude. The town of Leadville, Colorado—where the race starts and ends—sits at 10,119 feet above sea level. The “Race Across the Sky” covers more than 18,000 feet of vertical gain and at its highest point, runners reach an elevation of 12,600 feet. (For context, “high altitude” is generally considered to begin around 5,000 feet above sea level.)

Roche went out aggressively and built a sizable cushion on Carpenter’s record of 15:42:59. At the halfway mark, Roche was ahead of course-record pace by over 25 minutes, according to iRunFar. By the 87.4 mile split, the gap had decreased to 15 minutes, but it was enough of a buffer for Roche to maintain.

After the race, Roche posted on Instagram recapping the feat and noting some prerace nerves.

“I put a big scary goal out there early this year: chasing the historic 15:42 Leadville 100 course record by one of the GOATs, Matt Carpenter,” he wrote. “Approaching my first 100 miler, though, I’m not sure I truly believed. I kept joking about where I’d drop out and what my order would be at the Leadville Taco Bell.”

While Roche is an accomplished trail runner, he’s historically had the most success at shorter distances, like the half marathon and 50K. In 2014, he was named the 2014 USATF Sub-Ultra Trail Runner of the Year, and he’s represented Team USA internationally.

Roche, along with his wife, Megan, are well-known in the running community for their coaching business and podcast: Some Work, All Play (SWAP). According to its website, SWAP’s professional roster includes athletes like mountain running world champion Grayson Murphy, three-time Barkley Marathons finisher John Kelly, and steeplechaser/mountain runner Allie Ostrander.

Login to leave a comment

The Incredibly Specific, Occasionally Gross Food We Eat to Fuel Our Ultras

The strangest and most distinct snacks we can’t live without when we’re on the trail all day The Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB) World Series Finals kick off on August 26 and run through September 1. The annual finale is made up of three races: the Ultra Trail du Mont Blanc Orsières-Champex-Chamonix (50K), the Ultra Trail du Mont Blanc Courmayeur-Champex-Chamonix (100K), and the classic UTMB (100M), across France, Italy, and Switzerland.

Sure, crowds come for the world-class athletes and spectacular views of the Alps, but, some might argue, another big draw is the food—and even the race participants get a taste on the course. Much of the fuel at aid stations are sourced from nearby communities, who bring their best. Think: locally made croissants, bread, cheese, and prosciutto.

But for those of us who haven’t had the pleasure of running by tents filled with freshly baked French baguettes on our long runs, here’s the weird, the specific, and the sometimes gross on how we fuel our adventures.

On a 13-hour, nearly 10,000-vertical foot ridge scramble/romp through the high peaks in New Mexico a few years ago, I fueled with the food of the gods: birthday cake in a bag. I had somehow scammed my way into having three cakes at my birthday dinner a few nights prior and figured the calorie-to-weight ratio of buttercream frosting couldn’t be far off from Gu. So I cut a generous piece of birthday cake, put it in a Ziploc, and stashed it in my pack. By the time I went to eat it, it had lost all structure and I could easily squeeze it directly into my mouth from a hole —Abigail Barronian, senior editor, Outside

The last time I ran 100 miles, it was a self-supported multi-day journey through the English countryside. The bad news: no aid stations. The good news: pubs and cafes at far greater frequency. I was able to refill my vest with raisin scones and coffee every ten miles. By itself, a scone is pretty dry. But combined with a mouthful of coffee (or even water), it becomes an easy-to-digest, carby snack that’s just the right amount of sweet. Plus, it’s perfectly sized to fit in a chest pocket.

—Corey Buhay, interim managing editor, Backpacker

I have been blessed with a rock-solid stomach and have never had gastrointestinal issues during any run or race. That gives me the freedom to consume just about anything, but I notably veer away from energy gels and opt for real food—either the breakfast burritos or ramen noodles available at aid stations or peanut butter tortilla wraps (sometimes with Nutella) and Pay Day candy bars (because they don’t melt and have a good blend of calories, carbs, fat and protein). I have also been known to drink pickle juice straight from the jar for the sodium content. I love the taste!

—Brian Metzler, editor-in-chief, RUN

I’m all about having a variety of guilty pleasure snacks on hand during an ultra! My favorite is a specific mix from Trader Joe’s called Many Things Snack Mix, with honey-roasted peanuts, sweet and spicy Chex-like cereal squares, pretzel sticks, and bread chips. It’s basically Chex mix. I put it in a Ziploc bag and relish being able to eat it without guilt during my run (because when I eat it at home, it’s never really fulfilling any kind of nutritional need and I always eat too much of it!).

I’ll also pack a Ziploc bag with gummy bears, and then another one with half of a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. Peanuts and peanut butter go down easy for me while also providing a bit of a “stick to your ribs” satiety, while the gummy bears have a fun texture and come with a sugar rush. A PB&J sandwich kind of combines both sides of that, and then the Chex mix—as long as it has some spicy pieces—wakes up my taste buds.

Login to leave a comment

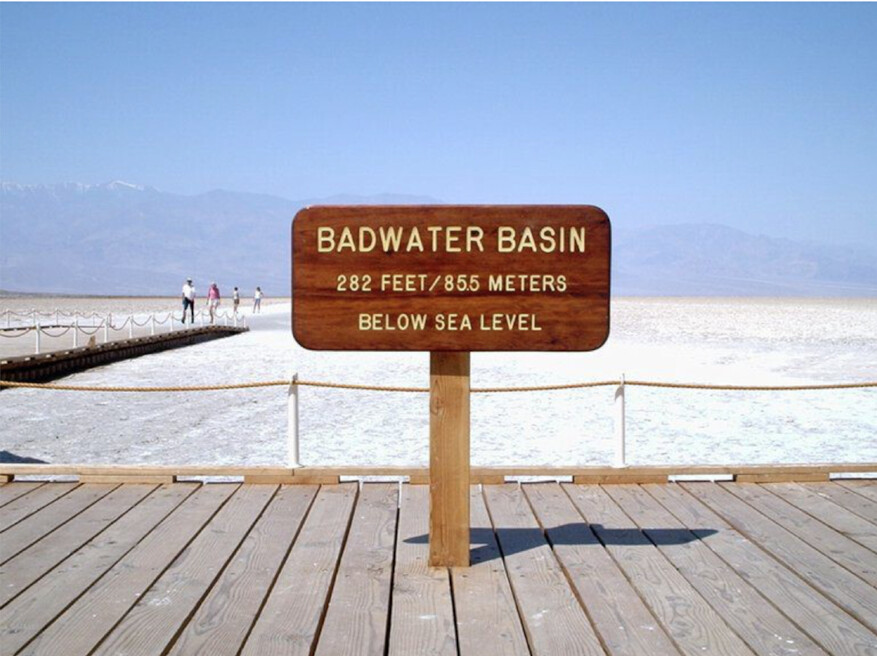

Harvey Lewis races Badwater 135 for the 13th time in a row

This year’s edition of Badwater 135, dubbed the “world’s toughest foot race,” kicked off on Monday, plunging runners into the brutal extremes of California’s Death Valley. This year’s race featured the return of fan favorites, including Backyard Ultra world champion Harvey Lewis, a two-time Badwater winner making his 13th consecutive appearance, and fellow American Pete Kostelnick, also a two-time champion, who made a remarkable comeback after a severe car accident in Leadville. American Shaun Burke claimed the overall victory amidst the scorching heat, while Norwegian Line Caliskaner triumphed in the women’s category, finishing an impressive second overall.

The 135-mile (217km) race kicks off at the Badwater Basin, which, at 85 metres below sea level, is the lowest point in North America. This year’s race saw temperatures hitting a scorching 51 degrees Celsius. Runners who finish under the 48-hour mark earn the prestigious Badwater 135 belt buckle.

In 2023, Viktoria Brown of Whitby, Ont., was the only Canadian in the field of 100 runners and finished in 30:11:52 securing fourth among the women and claiming 13th place overall. This year’s race saw two Canadians joining the ranks—Frances Picard of Quebec, and Hannah Perry from Canmore, Alta.

Men’s race

Last year’s men’s champion, Simen Holvik of Norway, led for much of the race—in 2023, Holvik was second to U.S. runner Ashley Paulson, who finished first overall and took two hours off her own women’s course record. Burke, who received a late invite to the event in June, steadily closed the gap, eventually overtaking him before the 108-mile timing point. Holvik did not finish the race, leaving Burke unchallenged for the remainder.

Burke completed Badwater for the first time in 2023, when he was sixth overall and fourth among the men. Spanish runner Iván Penalba Lopez claimed the second men’s spot (third overall) in 28:06:34 in his third finish of the race, and Michael Ohler of Germany completed the men’s podium and third man (fourth overall) in 28:24:25. Kostelnick succeeded in finishing his come-back race, crossing the line in 35:28:55; Lewis followed in 36:41:22.

Picard, who was tackling the race for the first time, was still on course at the time of publication.

Top men

Shaun Burke (U.S.) 23:29:00 Iván Penalba Lopez of Alfafar (Spain) 28:06:34 Michael Ohler (Germany) 28:24:25

Women’s race

Caliskaner became the first Norwegian woman to complete the event, finishing second overall. An accomplished ultrarunner, in 2023 52-year-old Calinskaner won both the Berlin Wall Race (100 miles), and the Thames Path 100-miler. She maintained a narrow lead over Micah Morgan of the U.S. early on and added to her lead as the race progressed. Caliskaner finished in 27:36:27, over two hours ahead of Morgan, who finished in 29:11:28, second among the women and fifth overall.

Josephine Weeden of the U.S. rounded out the women’s podium in 33:26:37. Absent from this year’s race was American Ashley Paulson, who won the women’s race for the past two years and took the overall title last year. Alberta’s Perry was still on course at the time of publication but had passed through the 108-mile aid station in 29 hours and 51 minutes.

Top women

Line Caliskaner (Norway) 27:36:27 Micah Morgan (U.S.) 29:11:28 Josephine Weeden (U.S.) 33:26:37

by Running magazine

Login to leave a comment

Western States 100: Walmsley Wins a Fourth Time While Schide Rocks the Women’s Field

For hours, Katie Schide (pre-race and post-race interviews) chased ghosts. For hours, Jim Walmsley (pre-race and post-race interviews) and Rod Farvard (post-race interview) chased each other. And in the end, after 100 courageous, gutsy miles at one of the world’s most iconic ultramarathons, it was Schide and Walmsley who won a fast, dramatic 2024 Western States 100.

Schide, an American who lives in France, was on pace to break the course record until late in the race, while Americans Walmsley and Farvard battled throughout most of the second half of the race, alternating the lead as late as mile 85.

Schide’s winning time was 15:46:57, just over 17 minutes behind Courtney Dauwalter’s 2023 course record, almost an hour faster than her own time last year, and the second fastest women’s time ever. Walmsley, meanwhile, won his fourth Western States in 14:13:45, the second fastest time ever — only behind his own record of 14:09:28 that he set in 2019.

Second and third in the men’s race came down to an epic sprint finish on the track between Farvard and Hayden Hawks (pre-race and post-race interviews), who finished in 14:24:15 and 14:24:31, respectively.

In the women’s race for the podium, Fu-Zhao Xiang (pre-race and post-race interviews) finished second in 16:20:03, and Eszter Csillag (pre-race and post-race interviews) took third for the second time in a row, in 16:42:17.

Both races featured one of the deepest and most competitive fields in race history, with the men’s top five all coming in faster than last year’s winning time, and the women’s top 10 finishing just under 40 minutes faster than last year’s incredibly competitive top 10.

At 5 a.m. on Saturday, June 29, they were all among the 375 runners who began the historic route from Olympic Valley to Auburn, California, traversing 100.2 miles of trail with 18,000 feet of elevation gain and 22,000 feet of loss. After last year’s cool temperatures, the weather at this year’s race was a bit warmer, albeit with a notable lack of snow in the high country. The high temperature in Auburn was in the low 90s Fahrenheit.

A special thanks to HOKA for making our coverage of the Western States 100 possible!

2024 Western States 100 Men’s Race

In his return to the race that propelled him to the heights of global trail running and his first ultra on American soil in three years, Jim Walmsley (pre-race interview) demonstrated why he is, once again, the king of Western States. Before the race, Walmsley exuded a calmness that perhaps eluded him during his first attempts, when he attacked it with an obsessive intensity that led him to famously take a wrong turn and then dropping out in back-to-back years.

“We’ll just roll with what plays out and just kind of see what happens in the race,” he said in his pre-race interview. There’s a marked difference when compared to his remarks from his interview before the 2016 race.

What happened in the race was this: In his fourth Western States, Rod Farvard (post-race interview) had the race of his life to push Walmsley like he’d never been pushed before in his long history with the event.

Farvard — a 28-year-old from Mammoth Lakes, California, who has improved his finish each year at the race, from a DNF in 2021 to 41st place in 2022 to 11th place last year — put himself in a strong position from the start, leading a large pack of runners that included Walmsley at the top of the Escarpment, the 2,500-foot climb in the first four miles of the race. For the next 45-plus miles, Farvard remained in the top 10, part of a chase pack of American Hayden Hawks (pre-race and post-race interviews), Kiwi Dan Jones (pre-race interview), and Chinese runner Guo-Min Deng, among others.

At the Robinson Flat aid station at mile 30 — the symbolic end of the runners’ time in the high country, which features an average elevation of around 7,000 feet — Walmsley, who started the race conspicuously wearing all black, came through in 4:24 looking fast and smooth, now wearing an ice-soaked white shirt. Jones, the 2024 Tarawera 102k champion and fifth-place finisher in his Western States debut last year, and Hawks, who set the course record at February’s Black Canyons 100k after dropping out of last year’s Western States, followed about 90 seconds later. The two runners, frequent training partners, ran together frequently throughout the day, with Hawks often foregoing ice at aid stations.

After the trio of Walmsley, Hawks, and Jones went through Last Chance at mile 43 together, Walmsley put nearly two minutes on them up the climb to Devil’s Thumb. “I was with everybody at the bottom,” he said, according to the race’s official livestream.

About halfway through, at mile 49.5, the order remained the same: Walmsley in the lead with an elapsed time of 6:58, followed by Jones one minute back, Hawks two minutes back, and Farvard just over two and a half minutes back. The rest of the top 10 were last year’s 17th-place finisher Dakota Jones; 2024 Transvulcania Ultramarathon champion Jon Albon (pre-race interview), who is from the U.K. but lives in Norway; 2023 fourth-place finisher Jia-Sheng Shen (China) (pre-race interview); 2023 Canyons 100k champion Cole Watson; Western States specialist Tyler Green (pre-race interview); and Jupiter Carera (Mexico).

Then began a thrilling, chaotic second half of the race — featuring a gripping back-and-forth between Walmsley and Farvard, a wildfire near the course, a two-man river crossing, and a sprint finish on the track.

It all started when Walmsley entered Michigan Bluff at mile 55, again looking calm and in control, changing shirts and getting doused with ice. Farvard came in just behind him and left the aid station first, leading the race for the first time since the first climb up the Escarpment. The same routine took place seven miles later at Foresthill: Walmsley entering first, Farvard leaving first.

For the next 18 miles, the two runners alternated in the lead. By mile 78, they were so close that they were crossing the American River at the same time. Their battle underscored the overall depth of the field at this year’s race: At mile 80, the top five men were within 16 minutes of one another.

Around then, the 15-acre Creek Fire, which started not long before, was visible from the final quarter of the course and crews were temporarily not permitted to travel to the Green Gate aid station at mile 80 because the route to it passed close to the fire. Eventually, a reroute was established for crews to get to Green Gate and, later, after the wildfire was controlled, the regular route was reopened.

At Green Gate, Farvard came through in the lead, with Walmsley four minutes back and looking like he was hurting. It was then, perhaps, that the thought entered people’s minds: Could Farvard really take down the champ?

But Jim Walmsley is Jim Walmsley for a reason, and he again proved why he is among the world’s best. Against the ropes, facing one of his first real challenges in the race that shaped him, he delivered, entering the next aid station, Auburn Lake Trails at mile 85, more than a minute earlier than Farvard. He had made up five minutes in five miles.

Walmsley never trailed again, increasing his lead to 11 minutes by the Pointed Rocks aid station at mile 94 and then picking up his crew, including his wife, Jess Brazeau, at Robie Point to run the final mile with him. He entered the track at Placer High School to loud cheers, his loping stride still looking smooth, stopping a few steps short of the tape to wave to the crowd and raise his arms in triumph. He had done it again.

Behind him, Farvard was fading but determined to cap an extraordinary race with a second-place finish. Hawks, who had made up five minutes on Farvard in the couple miles between Pointed Rocks and Robie Point, was on the hunt, and by the time he stepped on the track, Farvard was within sight.

It was then that fans were treated to one of the most unique sights in all of ultrarunning: After 100 miles of racing, two men were sprinting against each other on a track. In the end, Farvard’s lead held, and he finished 16 seconds ahead of Hawks. He collapsed at the finish line — a fitting end to an epic performance.

Dan Jones ended a strong race with a fourth-place finish in 14:32:29, with Caleb Olson capping an impressive second half of the race — from 11th at mile 53 to fifth in 14:40:12 at the finish. All five men ran a time that would have won the race last year.

Behind Olson came Jon Albon, running 14:57:01 in his 100-mile running-race debut, followed by the surgical Tyler Green, who finished in seventh for his fourth straight top 10 finish at the race. Green’s time of 15:05:39 also marked a new men’s masters course record, breaking the 2013 Mike Morton record of 15:45:21.

Rounding out the top 10 were Jia-Sheng Shen in eighth with a time of 15:09:49, Jonathan Rea in ninth who methodically moved his way up during the last 60 miles to finish in 15:13:10; and Chris Myers in 10th in 15:18:25.

2024 Western States 100 Women’s Race

Through the high country, into and out of the canyons, and along the river of the world’s oldest 100-mile trail race, Katie Schide (pre-race and post-race interviews) raced only the ghosts of the clock and history. Smiling throughout, she seemed unaffected by the solitude and the enormity of the possibility that lay before her: to attempt to break the course record of one of the world’s most iconic trail races.

Schide, an American who lives in France, came into the race as the clear favorite, and for good reason: She finished second last year, breaking Ellie Greenwood’s previously untouchable 2012 course record by more than three minutes and losing to only Courtney Dauwalter, who broke Greenwood’s record by an astounding 78 minutes on her way to a historic Western States-Hardrock 100-UTMB triple win. Schide, winner of the 2022 UTMB and 2023 Diagonale des Fous 100 Mile, spent the last two-and-a-half months in Flagstaff, Arizona, training for Western States, winning this year’s Canyons 100k in an impressive tune-up and putting in a monster training block.

In her pre-race interview, Schide said that she had thought about ways to improve her race from last year, which perhaps should have been the first warning to her competition. The second, then, was her immediate separation from the women’s chase pack: She summited the Escarpment, a 2,500-foot climb during the first four miles, in first place and never looked back. By the first aid station — Lyon Ridge at 10 miles — she was already 12 minutes under course record pace, and by Robinson Flat at mile 30, she was 21 minutes ahead of second-place Emily Hawgood (pre-race interview), from Zimbabwe but living in the U.S.

The lead only ballooned from there. By Dusty Corners at mile 38, Schide was an incredible 26 minutes under course record pace, and though she lost a few minutes from that pace by the time she climbed up to Michigan Bluff at mile 55, her smile had not waned even slightly. She smoothly entered the iconic aid station, doused herself with ice, changed shirts, and was soon on her way. She never sat down.

Twenty-seven minutes behind her was Hawgood, looking to build on back-to-back fifth-place finishes. Eszter Csillag (pre-race and post-race interviews), a Hungarian who lives in Hong Kong, followed soon after, in the same third spot she finished in last year.

After them ran a dense pack of women: Only 16 minutes separated Hawgood in second from Lotti Brinks in 11th.

At the halfway point, the top 10 were Schide, 33 minutes up in an elapsed time of 7:26; Csillag; Hawgood; Chinese runner Fu-Zhao Xiang (pre-race and post-race interviews), the fourth-place finisher at last year’s UTMB; Lin Chen (China); American Heather Jackson, a versatile former triathlete who recently finished fifth at a competitive 200-mile gravel bike race; ultrarunning veteran Ida Nilsson (pre-race interview), a Swede living in Norway; Becca Windell, second in this year’s Black Canyon 100k; 2023 CCC winner Yngvild Kaspersen (Norway); and Rachel Drake, running her 100-mile debut.

Schide, easily identifiable in her pink shirt, maintained her large lead throughout the second half of the race, remaining calm, controlled, and upbeat throughout the tough canyon miles. By Foresthill at mile 62, she was 19 minutes ahead of course record pace and 48 minutes ahead of the second-place Xiang. Schide’s stride still looked smooth as she waved to fans and even high-fived a cameraman.

Schide’s aggressive pace eventually slowed — by Green Gate at mile 80, her lead on the course record had dissipated — but her spirits did not. After a quick sponge bath at Auburn Lake Trails aid station at mile 85, she fell behind course-record pace for the first time all day, only 15 miles remained until the finish.

Schide entered the track a couple of hours later, running with her crew and no headlamp. She would finish before dark. She stopped for a hug on the final straightaway and lifted the tape with, of course, a smile.

Xiang had methodically pulled away from Hawgood and Csillag during an incredibly strong second half to win the battle for second. Fu-Zhao Xiang finished in 16:20:03 for the third fastest time in race history. Chen, who dropped out at mile 78, was one of the few elite runners who had a DNF on this day, which was categorized by a lack of attrition in both the women’s and men’s elite races.

Eszter Csillag came in about 22 minutes behind Xiang in 16:42:17 for her second consecutive third-place finish, a 30-minute improvement from last year — a statistic that perhaps exemplifies the speed of this year’s race better than any other.

The battle for fourth and fifth was nearly as close as Farvard and Hawks’s race for second in the men’s race a couple of hours earlier.

At Pointed Rocks at mile 94, Hawgood led by barely two minutes, running hard and straight through the aid station. Kaspersen, meanwhile, was drinking Coke and made up almost a minute by Robie Point.

Emily Hawgood’s lead ultimately held, and she finished fourth in 16:48:43 to improve her finish from prior years by one spot. Yngvild Kaspersen was less than two minutes back in 16:50:39. Ida Nilsson capped a strong day to finish sixth in 16:56:52 and break Ragna Debats’s masters course record by almost 45 minutes. That means the top six women all finished in under 17 hours in a race that had only ever had three women finish under that mark — and two of them, Dauwalter and Schide, were last year.

The rest of the top 10 were Heather Jackson in seventh in 17:16:43, and, in close succession, Rachel Drake in 17:28:35, Priscilla Forgie (Canada) in 17:30:24, and Leah Yingling in 17:33:54.

The top 10 women were all faster than the 12th-fastest time in race history going into the day.

by Robbie Harms

Login to leave a comment

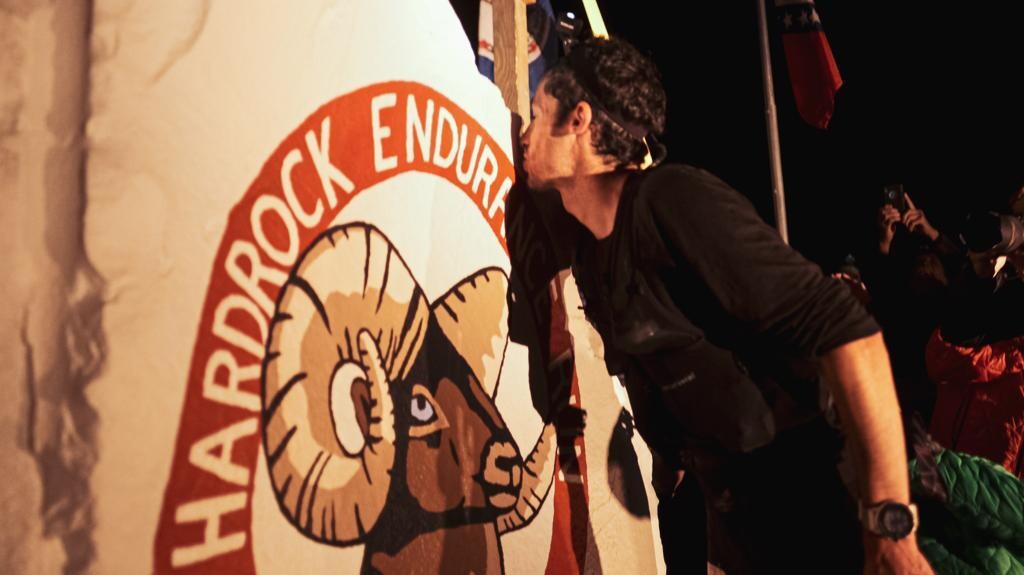

Hardrock 100

100-mile run with 33,050 feet of climb and 33,050 feet of descent for a total elevation change of 66,100 feet with an average elevation of 11,186 feet - low point 7,680 feet (Ouray) and high point 14,048 feet (Handies Peak). The run starts and ends in Silverton, Colorado and travels through the towns of Telluride, Ouray, and the ghost town...

more...TWENTY-ONE YEARS AGO, HE WAS INCARCERATED FOR LIFE. LAST YEAR, HE RAN THE NYC MARATHON A RADICALLY CHANGED MAN.

RAHSAAN ROUNDED THOMAS A CORNER. Gravel underfoot gave way to pavement, then dirt. Another left turn, and then another. In the distance, beyond the 30-foot wall and barbed wire separating him from the world outside, he could see the 2,500-foot peak of Mount Tamalpais. He completed the 400-meter loop another 11 times for an easy three miles.

Rahsaan wasn’t the only runner circling the Yard that evening in the fall of 2017. Some 30 people had joined San Quentin State Prison’s 1,000 Mile Club by the time Rahsaan arrived at the prison four years prior, and the group had only grown since. Starting in January each year, the club held weekly workouts and monthly races in the Yard, culminating with the San Quentin Marathon—105 laps—in November. The 2017 running would be Rahsaan’s first go at the 26.2 distance.

For Rahsaan and the other San Quentin runners, Mount Tam, as it’s known, had become a beacon of hope. It’s the site of the legendary Dipsea, a 7.4-mile technical trail from Mill Valley to Stinson Beach. After the 1,000 Mile Club was founded in 2005, it became tradition for club members who got released to run that trail; their stories soon became lore among the runners still inside. “I’ve been hearing about the Dipsea for the longest,” Rahsaan says.

Given his sentence, he never expected to run it. Rahsaan was serving 55 years to life for second-degree murder. Life outside, let alone running over Mount Tam all the way to the Pacific, felt like a million miles away. But Rahsaan loved to run—it gave him a sense of freedom within the prison walls, and more than that, it connected him to the community of the 1,000 Mile Club. So if the volunteer coaches and other runners wanted to talk about the Dipsea, he was happy to listen.

We’ll get to the details of Rahsaan’s crime later, but it’s useful to lead with some enduring truths: People can grow in even the harshest environments, and running, whether around a lake or a prison yard, has the power to change lives. In fact, Rahsaan made a lot of changes after he went to prison: He became a mentor to at-risk youth, began facing the reality of his violence, and discovered the power of education and his own pen. Along the way, Rahsaan also prayed for clemency. The odds were never in his favor.

To be clear, this is not a story about a wrongful conviction. Rahsaan took the life of another human being, and he’s spent more than two decades reckoning with that fact. He doesn’t expect forgiveness. Rather, it’s a story about a man who you could argue was set up to fail, and for more than 30 years that’s exactly what he did. But it’s also a story of navigating the delta between memory and fact and finding peace in the idea that sometimes the most formative things in our lives may not be exactly as they seem. And mostly, it’s a story of transformation—of learning to do good in a world that too often encourages the opposite.

RAHSAAN “NEW YORK” THOMAS GREW UP IN BROWNSVILLE, A ONE-SQUARE-MILE SECTION OF EASTERN Brooklyn wedged between Crown Heights and East New York. As a kid he’d spend hours on his Commodore 64 computer trying to code his own games. He loved riding his skateboard down the slope of his building’s courtyard. On weekends, he and his friends liked to play roller hockey there, using tree branches for sticks and a crushed soda can for a puck.

Once a working-class Jewish enclave, Brownsville started to change in the 1960s, when many white families relocated to the suburbs, Black families moved in, and city agencies began denying residents basic services like trash pickup and streetlight repairs. John Lindsay, New York’s mayor at the time, once referred to the area as “Bombsville” on account of all the burned-out buildings and rubble-filled empty lots. By 1971, the year after Rahsaan was born, four out of five families in Brownsville were on government assistance. More than 50 years later, Brownsville still has a poverty rate close to 30 percent. The neighborhood’s credo, “Never ran, never will,” is typically interpreted as a vow of resilience in the face of adversity. For some, like Rahsaan, it has always meant something else: Don’t back down.

The first time Rahsaan didn’t run, he was 5 or 6 years old. He had just moved into Atlantic Towers, a pair of 24-story buildings beset with rotting walls and exposed sewer pipes that housed more than 700 families. Three older kids welcomed him with their fists. Even if Rahsaan had tried to run, he wouldn’t have gotten far. At that age, Rahsaan was skinny, slow, and uncoordinated. He got picked on a lot. Worse, he was light-skinned and frequently taunted as “white boy.” The insult didn’t even make sense to Rahsaan, whose mother is Black and whose father was Puerto Rican. “I feel Black,” he says. “I don’t feel [like] anything else. I feel like myself.”

Rahsaan hated being called white. It was the mid-1970s; Roots had just aired on ABC, and Rahsaan associated being white with putting people in chains. Five-Percent Nation, a Black nationalist movement founded in Harlem, had risen to prominence and ascribed godlike status to Black men. Plus, all the best athletes were Black: Muhammad Ali. Reggie Jackson. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. In Rahsaan’s world, somebody white was considered physically inferior.

Raised by his mother, Jacqueline, Rahsaan never really knew his father, Carlos, who spent much of Rahsaan’s childhood in prison. In 1974, Jacqueline had another son, Aikeem, with a different man, and raised her two boys as a single mom. Carlos also had another son, Carl, whom Rahsaan met only once, when Carl was a baby. Still, Rahsaan believed “the myth,” as he puts it now, that one day Carlos would return and relieve him, his mom, and Aikeem of the life they were living. Jacqueline had a bachelor’s degree in sociology and worked three jobs to keep her sons clothed and fed. She nurtured Rahsaan’s interest in computers and sent him to a parochial school that had a gifted program. Rahsaan describes his family as “upper-class poor.” They had more than a lot of families, but never enough to get out of Brownsville, away from the drugs and the violence.

Some traumas are small but are compounded by frequency and volume; others are isolated occurrences but so significant that they define a person for a lifetime. Rahsaan remembers his grandmother telling him that his father had been found dead in an alley, throat slashed, wallet missing. Rahsaan was 12 at the time, and he understood it to mean his father had been murdered for whatever cash he had on him—maybe $200, not even. Now he would never come home.

Rahsaan felt like something he didn’t even have had been taken from him. “It just made me different, like, angry,” he says. By the time he got to high school, Rahsaan resolved to never let anyone take anything from him or his family again. “I started feeling like, next time somebody tryin’ to rob me, I’m gonna stab him,” he says. He started carrying a knife, a razor, rug cutters—“all kinds of sharp stuff.” Rahsaan never instigated a fight, but he refused to back down when threatened or attacked. It was a matter of survival.

The first time Rahsaan picked up a gun, it was to avenge his brother. Aikeem, who was 14 at the time, had been shot in the leg by a guy in the neighborhood who was trying to rob him and Rahsaan. A few months later, Rahsaan saw the shooter on the street, ran to the apartment of a drug dealer he knew, and demanded a gun. Rahsaan, then 18, went back outside and fired three shots at the guy. Rahsaan was arrested and sent to Rikers Island, then released after three days: The guy he’d shot was wanted for several crimes and refused to testify against Rahsaan.

By day, Rahsaan tried to lead a straight life. He graduated from high school in 1988 and got a job taking reservations for Pan Am Airways. He lost the job after Flight 103 exploded in a terrorist bombing over Scotland that December, and the company downsized. Rahsaan got a new job in the mailroom at Debevoise & Plimpton, a white-shoe law firm in midtown Manhattan. He could type 70 words a minute and hoped to become a paralegal one day.

Rahsaan carried a gun to work because he’d been conditioned to expect the worst when he returned to Brownsville at night. “If you constantly being traumatized, you constantly feeling unsafe, it’s really hard to be in a good mind space and be a good person,” he says. “I mean, you have to be extraordinary.”

After high school, some of Rahsaan’s friends went to Old Westbury, a state university on Long Island with a rolling green campus. He would sometimes visit them, and at a Halloween party one night, he got into a scrape with some other guys and fired his gun. Rahsaan spent the next year awaiting trial in county jail, the following year at Cayuga State Prison in upstate New York, and another 22 months after that on work release, living in a halfway house in Queens. He got a job working the merch table for the Blue Man Group at Astor Place Theater, but the pay wasn’t enough to support the two kids he’d had not long after getting out of Cayuga.

He started selling a little crack around 1994, when he was 24. By 27 he was dealing full-time. He didn’t want to be a drug dealer, though. “I just felt desperate,” he says. Rahsaan had learned to cut hair in Cayuga, and he hoped to save enough money to open a barbershop.

He never got that opportunity. By the summer of 1999, things in New York had gotten too hot for Rahsaan and he fled to California. For the first time in his 28 years, Rahsaan Thomas was on the run.

EVERY RUNNER HAS AN ORIGIN STORY. SOME START IN SCHOOL, OTHERS TAKE UP RUNNING TO IMPROVE their health or beat addiction. Many stories share common themes, if not exact details. And some, like Rahsaan’s, are absolutely singular.

Rahsaan drove west with ambitions to break into the music business. He wanted to be a manager, maybe start his own label. His new girlfriend would join him a week later in La Jolla, where they’d found an apartment, so Rahsaan went first to Big Bear, a small town deep in the San Bernardino Mountains 100 miles east of Los Angeles. It’s where Ryan Hall grew up, and where he discovered running at age 13 by circling Big Bear Lake—15 miles—one afternoon on a whim. Hall has recounted that story so many times that it’s likely even better known than the American records he would go on to set in the half and full marathons.

Rahsaan didn’t know anything about Ryan Hall, who at the time was just about to start his junior year at Big Bear High School and begin a two-year reign as the California state cross-country champion. He didn’t even know there was a lake in Big Bear. Rahsaan went to Big Bear to box with a friend, Shannon Briggs, a two-time World Boxing Organization heavyweight champion.

Briggs and Rahsaan had grown up together in Atlantic Towers. As kids they liked to ride bikes in the courtyard, and later they went to the same high school in Fort Greene. But Briggs’s mom had become addicted to drugs by his sophomore year, and they were evicted from the Towers. Briggs and Rahsaan lost touch. Briggs began spending time at a boxing gym in East New York; often he’d sleep there. He had talent in the ring. People thought he might even be the next Mike Tyson, another native of Brownsville who was himself a world heavyweight champ from 1986 to 1989.

Briggs went pro in 1991, and by the end of that decade he was earning seven figures fighting guys like George Foreman and Lennox Lewis. Rahsaan was at those fights. The two had reconnected in 1996, when Rahsaan was trying to rebuild his life after prison and Briggs’s boxing career was on the rise. In August 1999, Briggs was gearing up to fight Francois Botha, a South African known as the White Buffalo, and had decamped to Big Bear to train. “He was like, ‘Yo, come live with me, bro,’” Rahsaan recalls.

Briggs was running three miles a day to increase his stamina. His route was a simple out-and-back on a wooded trail, and on one of Rahsaan’s first days there, he decided to join him. Rahsaan hadn’t done so much as a push-up since getting out of prison, but he wanted to hang with his friend. Briggs and his training partners set off at their usual clip; within a few minutes they’d disappeared from Rahsaan’s view. By the time they were doubling back, he’d barely made it a half mile.

Rahsaan never liked feeling physically inferior. So back in La Jolla, he started running a few times a week, going to the gym, whatever it took. Before long he was up to five miles. And the next time he ran with Briggs, he could keep up. After that, he says, “Running just became my thing.”

FOR YEARS, RAHSAAN HAD BUCKED AT TAKING RESPONSIBILITY for the murder that sent him to prison. The other guys had guns, too, he insisted. If he hadn’t shot them, they’d have shot him. It was self-defense.