Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Search Results for Ultra

Today's Running News

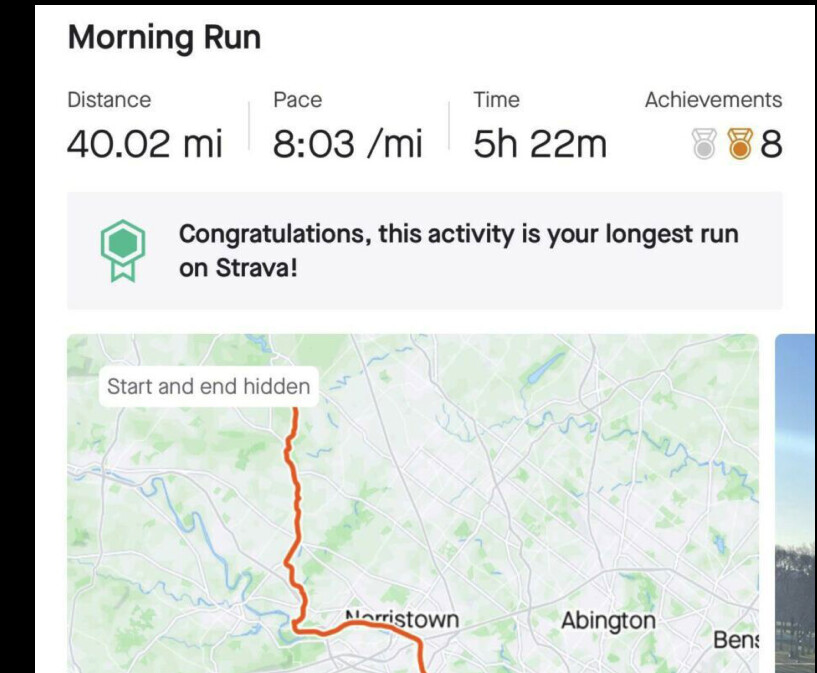

Pennsylvania woman rips fast 40 miles for her 40th birthday

Some runners celebrate reaching a new age category by heading out for their new number in minutes or covering it in kilometres; Holly Benner of Macungie, Penn. took it to the next level, ripping a speedy 40-mile trail run to celebrate her becoming a quadragenarian.

Benner covered 40 miles (64 kilometres) in just over five hours, averaging a pace of five minutes per kilometre.

Going in, Benner intended to cover 40 miles but had no particular time goal. “I just went with the flow,” she says. “I felt great at 20 kilometres and never looked back. It’s so cool to see what our bodies are capable of.”

Benner knew she wanted to spend her birthday doing something she loved, which is how running 40 birthday miles came into her mind. “It was so much fun—it’s cool to challenge yourself,” says Benner. “I didn’t do this to prove anything.”

Benner comes from an athletic background. She was the team captain of her NCAA collegiate swim team and went on to race triathlon at an elite level before taking up trail running in 2010. She has run ultra-trail races from 50K to eight hours, reaching the podium in her last two of three races.

In December, she hit her long-time goal of a sub-three-hour marathon at the 2022 California International Marathon, finishing in 2:53:55. Benner considers herself primarily a road marathoner, but intends to get more into ultra-trail racing eventually. “My immediate goal is sub-1:20 for the half and then attempt a sub-2:45 marathon in the fall,” she says.

“There’s a few 50K’s in Canada that I have my eye on,” she laughs.

When we asked Benner what she was most excited about in turning 40, like a true masters runner, she said, “the new age category.”

(03/18/2023) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

Ethiopians poised to dominate Rome Marathon

The Acea Run Rome The Marathon has proved a happy hunting ground in recent years for athletes from the east African nation

Winners of the Rome Marathon in the past include Emile Puttemans of Belgium, Bernie Ford from Britain and Stefano Baldini of Italy. But Ethiopia has dominated in recent years and the east African nation will be tough to beat again in the 2023 event on Sunday (March 19).

Six of the last nine men’s winners and seven of the last eight women’s champions in Rome have come from Ethiopia and runners from that country lead the entries this weekend too.

Fikre Bekele will attempt to defend his men’s title whereas fellow Ethiopian Zinash Debebe Getachew leads the women’s line-up.

Bekele ran a course record of 2:06:48 last year in the Italian capital but has since improved his best to 2:06:16 when he won the Linz Marathon in October.

Also expected to be at the front of the 15,000-strong field are Berhanu Heye and Alemu Gemechu of Ethiopia along with Nicodemus Kimutai of Kenya. Look out too for reigning Dublin Marathon champion Taoufik Allam of Morocco.

Women’s favorite Getachew has a best of 2:27:15 but will be challenged by Brenda Kiprono of Kenya, plus Mulugojam Ambi and Amid Fozya Jemal of Ethiopia.

The women’s course record is held by Alemu Megertu with 2:22:52.

Italian interest, meanwhile, includes Nekagenet Crippa (the older brother of European 10,000m champion Yeman), Stefano La Rosa and Giorgio Calcaterra. The latter, who is now aged 51, is known as the ‘king of Rome’ as he first ran the Rome Marathon 20 years ago and has completed 330 marathons during his life, won the world 100km title three times and has notched up 12 consecutive victories in the famous 100km del Passatore ultra-marathon.

A little further down the field, all eyes will be on Ermias Ayele, a former race director of the Great Ethiopian Run who is aiming to complete the 26.2 miles barefoot in memory of the great Abebe Bikila, who stormed to Olympic glory on the streets of Rome in 1960.

“Abebe Bikila laid the foundation for the success of not only Ethiopian athletes, but Africans in general as he was the first black to win a gold medal in the Olympic Games,” he says. “However, I have always felt that he did not get the recognition he deserved. Moreover, his story always inspired me and that’s why I am planning to emulate him in the same place and the same way, where he made history and pay tribute to all he’s done for athletics and Ethiopia.”

(03/17/2023) ⚡AMPby Jason Henderson

Run Rome The Marathon

When you run our race you will have the feeling of going back to the past for two thousand years. Back in the history of Rome Caput Mundi, its empire and greatness. Run Rome The Marathon is a journey in the eternal city that will make you fall in love with running and the marathon, forever. The rhythm of your...

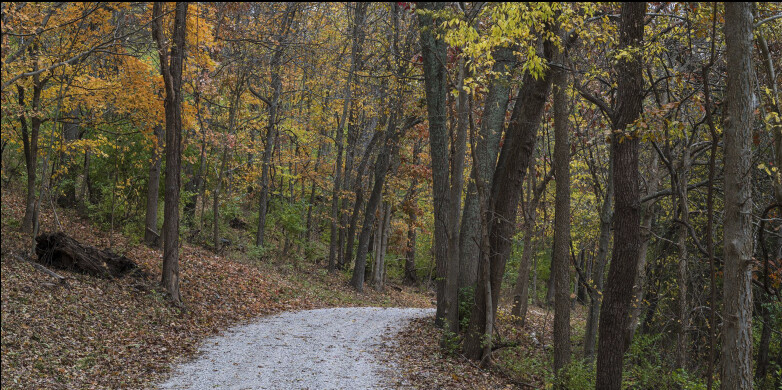

more...Runner Sues After He Was Shot By Hunter on Missouri Trail

Fred Cay says he can no longer run marathons or ultramarathons and is suing the turkey hunter and the state of Missouri after suffering injuries as a result of the 2021 incident.

On the morning of May 8, 2021, Fred Cay donned a yellow vest and headed out to a bucolic public trail in St. Louis overlooking the Missouri River to put in some miles at the Weldon Spring Conservation Area, a popular hiking, biking—and hunting—spot. However, his 8.2-mile run on the Lewis Trail was cut short when a hunter fired his shotgun at Cay, felling the then 47-year-old endurance athlete. First responders wheeled Cay to a clearing and he was flown to the hospital by helicopter.

He’s now suing the hunter, Mark A. Polson, the state of Missouri, and a group involved with developing trail systems in the region, according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. An incident report shows that Polson thought he’d shot at a turkey. The hunter, 62 at the time of the incident, told investigators that he fired one shot at a flying turkey and then immediately heard a person scream. He said that when he found Cay, he’d been hit in the side by three shot pellets, including two that went into the chest cavity.

According to the lawsuit, Cay alleges that he suffered a collapsed lung, punctured lung, lacerated spleen, punctured pericardium, and two puncture wounds in the side. He went through multiple surgeries—exploratory, open-heart, and to repair damage to his lungs and other organs—and suffered a blood clot while recovering.

Before the shooting, Cay competed in marathons and ultramarathons, and now, his attorney, Carey Press, argues in court records, his “endurance and running ability has been hindered by his injuries, and it is unknown if they will ever return to their previous capacity.”

Polson had a permit to hunt in the conservation area that day, but Cay’s lawsuit claims there weren’t adequate warnings to notify runners, cyclists, and pedestrians of the managed turkey hunt taking place.

“By specifically regulating, inviting, and permitting these hunters to be in such extremely close proximity to public recreational users, MDOC breached its duty to keep public users, such as Fred Cay, free from foreseeable harm,” the lawsuit states.

Mark Zoole, in charge of the district’s defense, told a reporter that while the Metropolitan Park and Recreation District “naturally feels sympathy for Mr. Cay’s injury, it is not responsible in any way for the incident.” He continued, “The District did not own or control the property where it occurred, and did not have any control over the actions of the individuals involved.”

Polson, the hunter, entered an Alford plea to second-degree assault early this year, an acknowledgment that there is enough evidence to convict, but not an admission of guilt. His sentence was suspended and he’s been placed on probation for five years, with conditions that he cannot obtain firearms or hunting licenses during this time, and must complete a hunter safety course.

Turkey hunting season begins again this April at the Weldon Spring Conservation Area, but Polson won’t be amongst his fellow sportsmen this year. Nor will Cay be joining fellow runners for local events like the St. Louis Track Club’s upcoming Weldon Spring Trail Marathon and Half.

(03/11/2023) ⚡AMPThree Rules to Keep Your Running Simple

One of my most memorable runs took place in Costa Rica when I was wearing sandals, board shorts, and a bathing suit after river rafting, and I couldn't resist the opportunity to run through a rainforest full of birdsong and howler monkeys.

My watch couldn't find the GPS signal to measure distance, but I didn't let that, or the lack of running shoes, stop me. I ran for 30 minutes, energized and entranced by the surroundings. That joy-filled run is a powerful reminder that we don't always need a planned workout or gear to reap the benefits of a run. We just need to break into a run and go.

Having run trails and ultras for two decades, I sense that runners are overthinking and over-complicating the relatively simple act of trail running more than ever before. We have way more access now to information and commentary about ultra-distance running, and more biofeedback due to sensors on smartwatches, phones, and gadgets. We follow elite runners online and try to train like them. It's easier than ever to fall into the comparison trap, feeling that our training is inadequate compared to the others we follow on Strava and social media.

I'd encourage you to tune out those messages and tune into the reasons you chose running long distances on trails in the first place: because it's healthy, beautiful, adventurous, and it makes you feel better. It's motivating and rewarding to train for an ultramarathon. And it's relatively cheap and simple, especially compared to gear-intensive sports like skiing or cycling. Just lace up your shoes-it's OK if those shoes are designed for road running!-and find your way to some dirt path somewhere, then go.Don't Let Perfect Be the Enemy of Good

During the many years I coached runners, the most difficult-to-coach clients tended to share a perfectionist streak that made them research the heck out of the sport and ask all sorts of questions, ranging from foot strike to electrolytes. Paradoxically, they often skipped workouts, or on race day, they DNFed. I suspect these high-achievers spread themselves too thin to fit in their training, plus they wanted each workout and race to be planned and executed to an extremely high standard. They couldn't adapt to a "good enough" or "some is better than none" mindset to just get out and get 'er done, and their seriousness sucked much of the joy out of the process.

Coach Liza Howard, a highly accomplished ultrarunner, told me she had a similar experience with some of her athletes. "I've had a lot of 'come to Jesus' talks where I say, 'You just need to get out and run.'" She says they'll send her articles about certain hill workouts to add to their training, or ask what their stride length should be, and she'll reply, "I don't want to talk to you about any doodad unless you start getting at least six hours of sleep." Three Basic Rules

The food writer and journalist Michael Pollan famously distilled all his research into a single line of nutrition advice composed of three short phrases that are rules to follow: "Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants."

Could we come up with a similar line of basic advice for our sport? I'll try: Run regularly. Not too fast. Mostly trails.

Run Regularly.

"Regularly" means consistently and frequently, following a sensible pattern that gradually increases the amount you run over weeks and months, depending on your goals. Carve out time to run at least three, preferably more, times a week, even if it's only for 20 minutes on some days. Sometimes, generally once a week, push the duration of a run to a point that feels challenging and fatiguing. Prioritize a good night's sleep to recover, and make sure you don't stack too many extra-long or hard-effort runs on top of each other so that you can adequately recover from the stress.

"Training is not always exciting, and in some cases, it may even be boring," says competitive ultrarunner Jade Belzburg, who coaches with her partner Nick de la Rosa at Lightfoot Coaching. "How many easy eight-mile runs have I done in the last eight years? Too many to count. And yet, I find these simple, consistent runs are what have made the biggest impact over time."

We don't always need a planned workout or gear to reap the benefits of a run. We just need to break into a run and go.

"Regularly" also suggests naturally and normally. This can be accomplished by paying attention to your internal cues-breath rate, fatigue and sweating-to determine how hard you're running and to find a sustainable effort level that allows you to keep going for the duration of your run, ideally with more joy than stress.

Howard advises the athletes she coaches to focus on their breathing to determine an appropriate pace and to ignore their watch mid-run, then review the watch's data afterward rather than while running. Not Too Fast.

This brings us to the next rule: "not too fast." Most of your runs should be at a steady "tortoise" pace that feels sustainable and allows you to talk in full sentences. Running in the aerobic zone (less than 80 percent of your max heart rate, or, put simply, at an effort level that allows you to talk) has numerous benefits and develops your aerobic energy system for long-distance running. If you get so winded running up a hill that you gasp while trying to speak, then downshift to hiking.

"Learn the rate of perceived exertion"-a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being maximum unsustainable effort and speed-"and keep most runs at what feels like an easy pace of 4 to 6," advises de la Rosa. The beauty of the rate of perceived exertion is that you follow your body's cues, not your watch's pace or heart rate reading.

Some high-intensity workouts with bursts of faster running are beneficial for any runner, to boost cardiovascular fitness and develop quicker leg turnover for speed. Hence, most runners fit some form of speedwork into their weekly routine. But most running should feel relatively slow and easy.

Mostly Trails.

OK, so why the final rule: "mostly trails"? The inherent variability and enjoyment of trail terrain can help you accomplish the first two points-to run more regularly and intuitively, and not too fast. If you're an urban dweller in a flat region who can only get to a trailhead occasionally, don't despair. Run wherever is most convenient and motivating, and try getting creative using stairways or a treadmill's incline to simulate hills.

Stay Safe, Simply

After you purchase the most basic and essential piece of gear-your running shoes-you'll face decisions about clothing, gear, hydration, and fueling. These aspects of trail running quickly become expensive and complex. To simplify, ask yourself, what do I need to stay safe?

The riskiest, most potentially life-threatening scenarios of trail running involve getting too hot (heat stroke) or too cold (hypothermia), dehydration or overhydration without adequate sodium (hyponatremia), getting lost, or getting hurt and not being able to get help. Start by planning your clothing, gear, and hydration now to avoid those scenarios in the future.

Use layers of clothing to regulate your body temperature and to provide sun and wind protection. A lightweight, breathable wind shell that repels rain can be a trail runner's best friend. Investing in gear such as a headlamp and a GPS tracker with an SOS button (in case you're out after dark or in the backcountry out of cell range) are wise investments for mountain runners, as is a basic first aid kit.

Carry plenty of water, along with some form of electrolytes such as salty snacks or tabs that dissolve in fluid, to replace fluids and salt you lose through sweating. Drink to thirst and do "the spit test" to determine if you're hydrating adequately. Is your mouth too dry to easily form spit? Then you need to drink!

You'll need something to carry your gear and hydration. As with shoes, a comfortable hydration vest or waist pack is a highly individualized choice. Try some on, read reviews, and look for bargains such as sales on last year's models.Tips to Fill Your Tank

Eating before, during, and after a longer run is vital, too, but it's more of a performance matter and rarely a safety issue. If you bonk from low blood sugar or puke, you'll still have enough stored energy in the form of fat to keep slogging through your run. As long as you're adequately hydrated, you'll be OK when you get home, or to the next aid station in a race, where you can regain some calories. You just won't run well or feel good, so let's avoid that scenario with proper fueling!

The amount and type of food you should consume mid-run depends on your fitness, body size, and the intensity and duration of your outing, so you'll need to experiment to find what works for you.

Generally speaking, you don't need to consume calories during everyday lower-intensity runs that are shorter than about 90 minutes, as long as you start your run with a "full tank" from healthy and satisfying eating throughout the day. Don't forget to refuel post-run, to restore the burned energy. Nonetheless, it's wise to carry a simple snack such as an energy gel on any run, and use it if you feel weak, or in case you end up on the trail longer than expected.

For runs and races that go from several hours to a full day, aim to eat around 200 calories per hour after the first hour. Don't demonize carbs, as they're your best energy source mid-run. Whether simple sugars from gels and sports drinks or a picnic-like buffet of sweet and starchy snacks, what works best for you during a long run can depend on many factors, including your stomach and palate. The best advice I got for parenting my two kids also applies to mid-ultra fueling: "Do what works!"

In addition to trying specialized gels and powders on the market, I also encourage you to experiment with everyday options on longer trail runs that are available from any grocery store, including potato chips, trail mix, a banana, or a good ol' PB&J. For sugar, try a cookie or some candy.

Most of all, try to remember that food is an athlete's fuel and friend, and it's best to eat a variety of food in quantities that leave you feeling truly satisfied. Runners who develop an adversarial or overly controlling relationship with food are doomed to suffer negative consequences in the long run, literally and figuratively. Ultimately: don't overthink it, and do what works best for you.

(03/10/2023) ⚡AMPby Trail Runner Magazine

110 Ultra Trail Runners Evacuated from Race Course

Heavy rains caused a river to overflow, stranding runners in freezing temperatures during the Southern Lakes Ultra in New Zealand.

A 7-day, 6-stage ultra-marathon on the South Island of New Zealand, was interrupted by severe weather earlier this week, which resulted in several athletes needing to be rescued, according to the New Zealand Herald. Rains quickly became intense, causing the Arrow River to rise in the wee hours of the morning, leaving runners stranded and unable to cross. Temperatures hovered around freezing, which meant athletes started experiencing hypothermia. Rescue efforts included personnel from the New Zealand Police Department, Search and Rescue, Fire and Emergency New Zealand, and Queenstown rescue helicopters.All in, 110 racers were evacuated. Seven race participants and one official were flown to Queenstown Lakes Hospital to be treated for hypothermia. According to reports, all have been released and are doing well. The South Island of New Zealand (Te Waipounamu) is known for its stunning glacial lakes and towering mountains. Runners of the event are promised endless breathtaking views before finishing in Queenstown, known as the adventure capital of the world. Participants have the choice between the long course (261 km) or the short course (226 km), and are encouraged to go at their own pace—from hiking to competitive running. The Southern Lakes Ultra spans 6-stages from February 19-25, including a rest day. It’s billed as a race that’s perfect for experienced trail runners and beginners alike. Each stage is between 10 and 70 kilometers. According to the race website, the course requires comfort in the backcountry. “Please, do not take lightly the terrain you will be in. Some of our stages are remote. You will be climbing and descending for hours, potentially some in the dark. You must be confident in the backcountry, on trails.”

Despite the weather conditions and rescue efforts, the race is continuing as planned. Some athletes have voiced disappointment in that decision, saying the race should have been called off and river levels checked more frequently. According to reports, one athlete said, “Conditions on the mountain were treacherous in the dark for an event which was pitched for beginner ultra competitors. ‘Show must go on mentality’ seems tone deaf.”

Most importantly, everyone is safe and accounted for. Rescue Coordination Centre Operations Manager Michael Clulow said he was grateful for everyone who helped with and supported the rescue effort.

(03/10/2023) ⚡AMPby Runner’s World

Top six reasons ultra runners are a breed apart, Ultrarunners' brains might be wired differently (how else to explain it?)

Ultra runners are pretty unique athletes. How many people are willing to run 50K, 100K, 100 miles or more? The answer is not a lot, which is why ultra running is so different from other sports. There are things that ultra runners do that no other athletes (not even short-distance runners) understand. Don’t believe us? Take a look at these few differences between ultra running and other sports.

Eating contests

To run an ultra marathon, you have to train well, but when race day arrives, your success will come down to how much you can eat–because after you’ve been running for several hours, your digestive system might be a little out of whack (and what goes in has been known to come back out). If you can keep enough nutrition down to keep your energy levels high for the entire race, you’ll do well.

To do that, ultra runners will eat some pretty random things on the race course (flat Coke and scalloped potatoes, anyone?), besides your classic energy gels and electrolyte drinks. Athletes in other sports are very careful about what they eat or drink before and during competitions, but for ultra runners, it seems like pretty much anything will work as fuel to get them to the finish line.

Weird sleeping habits

A basketball player wouldn’t take a court side nap, just like a hockey player would never go to sleep on the bench or in the penalty box, but that’s not the case with ultra runners. If you’re in a race that will take you more than a day to complete, you’re going to get pretty exhausted on the course, and that might mean you’ll need to take a nap break at some point–even if it means lying down by the side of the trail, or in a ditch, for a few minutes of shut-eye. (It’s called a dirt nap, for the uninitiated.) Ultra runners get pretty good at sleeping anywhere and for however long, so they can re-energize and get back to racing.

No rush

In most sports, you’re encouraged to go as fast as possible, because your speed will be rewarded with a touchdown, goal, basket or some other form of points. In ultra running, athletes aim to complete each race in good time, but there’s no rush. In fact, going too fast will only hurt your result and jeopardize your chances of finishing the race at all. Ultra runners quickly learn how to find a comfortable pace that they can hold for hours upon hours (or even days) of running and power-hiking.

No end

While most ultra marathons have set distances, some events are open-ended and go as long as it takes until only one runner is left standing. These are known as backyard ultras, and they task competitors with running a 6.71-km (4.17-mile) lap every hour for as many hours as they can. One by one, athletes will drop out of the race, either because they can’t go any longer or because they don’t complete a lap before the hour is up. Can you think of any other sport with this last-runner-standing, no-end-in-sight format? Didn’t think so.

No schedule

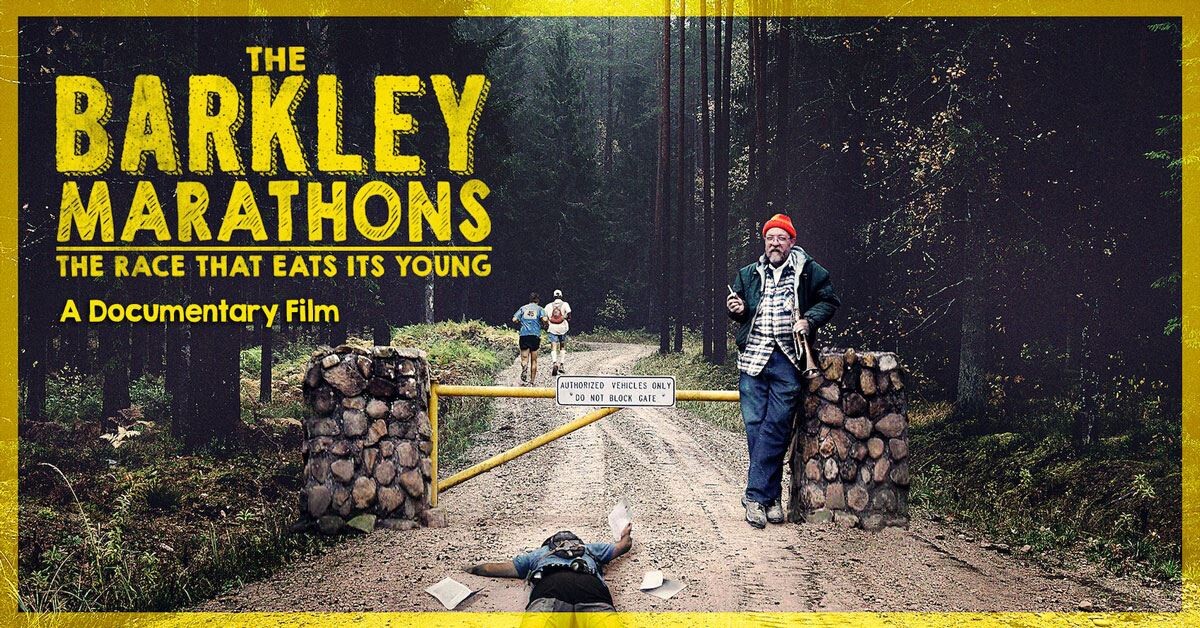

The Barkley Marathons is one of the most infamous ultra marathons on the planet, but despite its cachet, it is incredibly secretive. The race’s start date isn’t even public knowledge until the athletes are at the start line. This would never fly in other sports. The NHL couldn’t tell players to be on-call and ready for a random start date for a game, but in the world of ultra marathons, this system works (for the Barkley Marathons, at least).

Get emotional

After running 100 miles, you’re going to be beaten down, both physically and mentally. Because of this mental wear, you may burst into tears at any moment. In most sports, crying may be a sign of weakness, but in ultras, it’s pretty normal. No one’s going to judge you, and who knows, if they see you crying they may join you.

(03/08/2023) ⚡AMPby Ben Snider-McGrath

80-year-old runs wild time at USATF 100 Mile Championships

The USATF 100-mile road national championships were held in Henderson, Nev. on Friday and Saturday at the Jackpot Ultra Running Festival, and while the elite men and women produced impressive results, the performance of the weekend has to go to David Blaylock, an 80-year-old athlete from Salt Lake City, Utah. Blaylock finished the race in a fantastic time of 29 hours, 47 minutes and 29 seconds, and he was followed by three other men in the 80-plus age division, each of whom finished the race.

80-plus division

Before this year’s race, Blaylock had already raced the Jackpot 100 several times, and he had managed to break 30 hours on multiple occasions. In 2022, the final year of his 70s, he ran 31:56:28 at the event. While this was still a great result, it wouldn’t have been a surprise if Blaylock, now in the M80 division, didn’t break 30 hours again over 100 miles, but he did just that on Saturday, crossing the finish line with 12 and a half minutes to spare.

The fact that Blaylock ran 100 miles at the age of 80 is impressive enough, but his sub-30-hour result makes the achievement all the more amazing. His average pace was just over 11 minutes per kilometre for the 160K race. Although it’s unclear where Blaylock’s result ranks all-time among Americans, based on the USATF record books, his 29:47 sits near the top. The current M80 American record over 100 miles belongs to Maurice Robinson, who posted a time of 29:03:21 at a race in Kansas in March 2022.

While Blaylock ultimately won the M80 race by more than 20 minutes, his victory was far from a lock. He had to chase 83-year-old Edward Rousseau for most of the run, and for a long stretch, he was an hour back of first place. It wasn’t until the 95th mile that Blaylock made the pass on Rousseau, and from that point on, his lead only grew.

Rousseau ended up crossing the line in a fantastic time of 30:09:08, and 80-year-olds Ian Maddieson and Denis Trafecanty finished third and fourth, respectively, in times of 37:15:39 and 37:59:42.

The elite races

San Francisco‘s Jonah Backstrom, 49, took home the men’s national 100-mile title with a winning time of 14:11:03. He won the race by more than 30 minutes over second-place finisher Zach Merrin, who finished in 14:48:59. Third place went to Pete Kostelnick, who stopped the clock almost an hour later in 15:47:24. In the women’s race, Nevada local Sierra DeGroff won in 15:59:56, just eking out a sub-16-hour result. She finished close to an hour ahead of second-place Lisa Cabiles, who completed the race in 16:42:54. Heather Huggins finished third in a time of 17:09:29.

(03/07/2023) ⚡AMPby Ben Snider-McGrath

Lattelecom Riga Marathon

If you have never been to Riga then, running a marathon or half-marathon could be a good reason to visit one of the most beautiful cities on the Baltic Sea coast. Marathon running has a long history in Riga City and after 27 years it has grown to welcome 33,000 runners from 70 countries offering five race courses and...

more...Colin Boerger and Jessy Sorrick win 2023 Little Rock Marathon

Colin Boerger and Jessy Sorrick are the winners of the 2023 Little Rock Marathon.

Beginning shortly after 11 a.m. Sunday and continuing into the afternoon, finishers of the 21st Little Rock Marathon will trickle across the finish line on La Harpe Boulevard.

Their legs plenty tired after completing the 26.2-mile course, runners will take a couple hundred more steps, following the signs directing them inside the back of the Statehouse Convention Center.

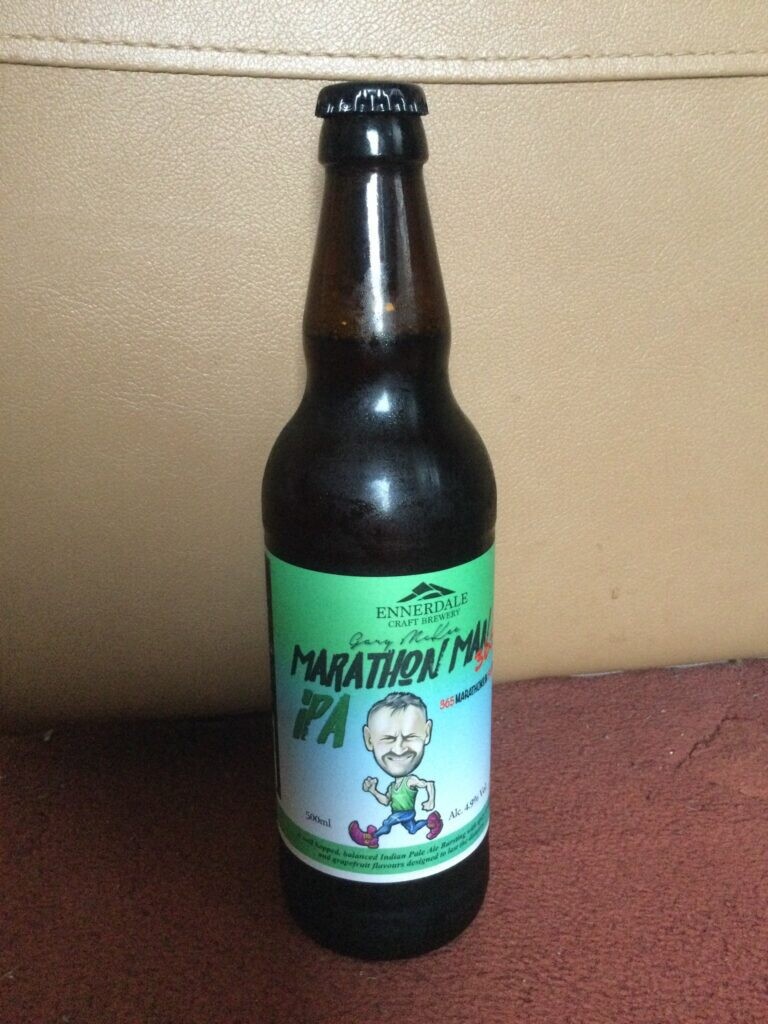

The runners will pose for pictures, then go grab a snack to refuel or some more water. Others might go for a celebratory Michelob Ultra -- or two -- before seeking out their friends and family for a hug.

But before any of that, each finisher will find a smiling volunteer and bow their head, awaiting one of the hundreds of oversized, sparkly, brightly-colored medals that will be placed around their neck.

Since its third edition in 2005, the Little Rock Marathon has awarded those who complete the race with a distinct, intricate prize -- enormous in size while also extravagant in detail.

This year's medal is no different, measuring in at more than 8 inches wide and nearly 3 pounds. Inspired by the theme, "Peace, Love, Little Rock Marathon," it features an interlocking peace sign and heart surrounded by symbols associated with the hippie movement such as flowers, doves, music and a van, brought to life with an array of bright, sparkly colors as is tradition for executive director Geneva Lamm.

Year after year, Lamm attempts to one-up herself with a unique and elaborate design, ensuring that each runner -- everyone from Searcy native Tia Stone, winner in five of the last seven women's races, to the final finisher -- has something to appropriately commemorate their accomplishment.

The idea spawned from a race Lamm ran in southern Texas shortly after beginning her role with the Little Rock Marathon in 2002. Lamm had just finished the marathon and her friend had completed the 5K race.

"When we finished, we got the same medal, and I was like, 'Oh, no, no, I did the marathon. I didn't do the 5K,' Lamm recalled. "They're like, 'No, that's the medal for everybody.' "

That didn't sit right with Lamm. She believed that everyone should get a medal the size of their individual achievement.

So, Lamm set out to make that the case for her race in Little Rock. She sketched out what she wanted of the first medal -- mostly in stick figures -- but quickly discovered that the companies bidding to produce them had a different idea of what it would actually look like.

That led Lamm to teach herself how to use the Adobe Creative Suite so she could specifically design the medals on her own. In 2006, she produced a sparkly version of the race's corporate logo, which Lamm calls "The Shield."

From there, the medals took on a life of their own, and each year, Lamm tasks herself with designing something one-of-a-kind to fit that race's theme.

In 2008, it was "Six in the City" to celebrate the race's sixth edition. In 2012, the theme was disco. The 2015 race was pirate-themed -- perhaps Lamm's favorite to date -- and as is the case each year, Lamm and race organizers encourage runners to dress in costume.

But idealizing and designing the medals is one thing. It's another to produce them, especially as the race has grown as large as 10,000 total runners across the different competitions -- marathon, half-marathon, 10K and 5K.

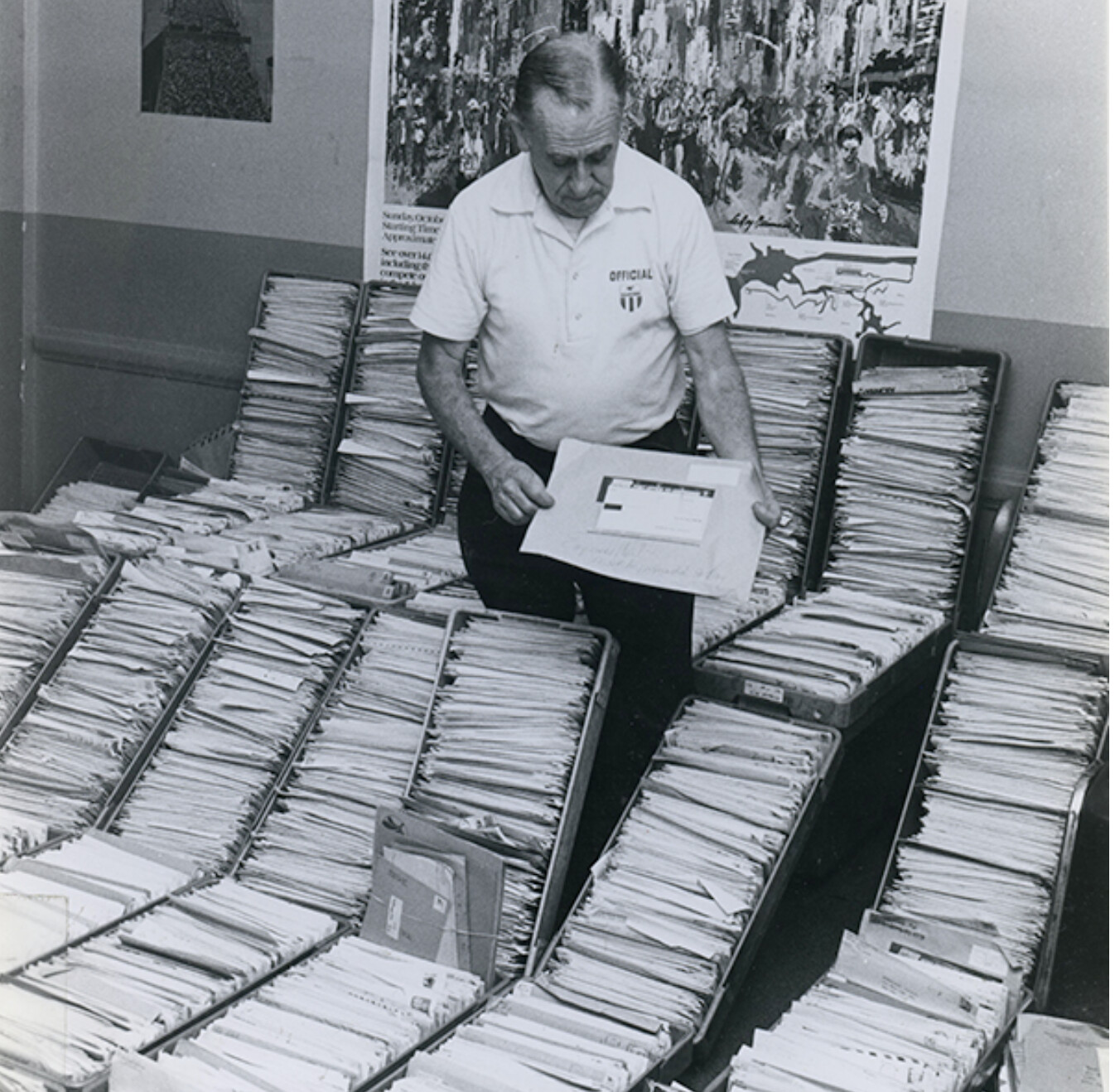

Steve Hasty, owner of Hasty Awards in Ottawa, Kan., has worked in conjunction with Lamm on and off for the last 12 years. It's not guaranteed Hasty will be the one chosen to produce the medals each race -- because the Little Rock Marathon is a fundraiser for the City of Little Rock's Parks and Recreation Department, Lamm has to run an annual blind-bidding process to determine who will get the contract for a given year.

But Hasty holds a special place in his heart for Little Rock because the medals are such a passion project for Lamm.

"There's no question that the Little Rock Marathon is the most fun race," Hasty told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. "[Geneva] is an educated customer, which makes it a lot easier."

The bidding typically begins in June, and for an early March race, Hasty likes to begin production no later than September.

For the marathon medals, the die-casting process begins by forcing each of the different colors of zinc-based alloy into the molds. Each of the different colors, many with glitter -- a Lamm specialty -- is allowed to dry before Hasty moves on to the next color.

All told, creating the Little Rock Marathon medal takes about 50 days. That's before the ribbon is hand-sewn on, all adding up to a cost of $13 per medal and leaving little profit margin for Hasty.

The goal is then to have all the medals completed and in Little Rock no later than January. Across the different competitions, that's between 9,000 and 10,000 medals -- almost a 400% increase from the 2,502 that participated in the inaugural race in 2003.

Lamm keeps a notepad on her desk at home with ideas for future themes, and she's already thinking about concepts and designs of medals for at least the next five years.

After 19 years, it's nothing but "a labor of love."

"It's always on my mind," Lamm said. "We're always trying to figure out how to do something better and new. ... The payoff for me and my staff is seeing those people cross the finish line."

(03/06/2023) ⚡AMPby Mitchell Gladstone

Little Rock Marathon

The mission of the Little Rock Marathon is provide a premier event open to athletes of all abilities, while promoting a healthy lifestyle through running and walking and raising money for Little Rock Parks & Recreation. Since inception in 2003, more than $1,093,000 has been donated to Little Rock Parks & Recreation. Little Rock Marathon Race Weekend is held the...

more...Love Advice from the Non-Runner Significant Other

Runners love runners, and while runners often date and marry other runners, some runners date non-runners who despise running.

My fiance is the latter. Running isn't for her. It isn't for everyone. A large part of me wishes we could share the miles and time together, and she wishes we could actually spend a Saturday morning together instead of me going on a long run only to come back, eat, and nap.

There's give and take in any relationship, but with any passion comes sacrifice. We see the passion on display everyday, but little do we hear about the sacrifice, the unfiltered thoughts of those who might not share the same affinity for run culture.

This Valentine's Day, we give them the mic. To my fiance, and to anyone else in similar situations, I hope you feel seen today.

Forty Years and 200+ Hundred Milers

If anyone can understand the grind and sacrifice of supporting an ultrarunner, it's Martha Ettinghausen. Her husband, Ed, 60, has logged more than two hundred 100-plus milers since his first in 2009-one of three people ever to hit that milestone.

For the vast majority of those races, the couple from Murieta, California, has done it all stride for stride. Martha was crew chief, sacrificing weekends, birthdays, and Mother's Days for her runner. It also included nights at home waiting to eat dinner until late hours, delayed romantic evenings on vacation due to Ed being "lost in the moment" of a run, and endless time and money poured into the sport.

"It really has cost us a fortune," Martha said. "There's so much sacrifice, if you want to call it that, that was given up for Ed to pursue his dream. I look at the time and money spent over the years. Sometimes I say, 'This could be our new car,' or, 'This could be an amazing vacation.' Really, it's kind of a selfish hobby, but so is any hobby."

But that's not what Martha takes away from Ed's passion. It has taken years to find balance, and also to recognize that you can be supportive without having to attend every race like she did at first. Now, she goes when she wants to.

"For the first 19 years of marriage, I don't think we spent one night apart," Martha said. "That was a lot of time together. We did everything together, and I like that connection, but in order to find my own life outside of it while he's off doing his thing, I had to learn to do my own thing. He's pursuing his passion; I can pursue mine also."

This has taken various forms: Saturday morning walks with her friends, starting her own business, not waiting to eat meals, even walking 104 miles herself last April at Beyond Limits in California. A big reason she pursued most of these passions was Ed's inspiration.

"One of the biggest things I've learned from Ed doing ultras is going in with a positive mindset and believing you can do it," Martha said. "Never be negative or allow doubt. That carries into every aspect of life. Don't take it so seriously. Watching Ed, I'm like, "You know what? I can do anything.'"

These are lessons learned from 40 years of marriage and 14 years of ultras. While it has its pros and cons and still requires conversations and compromises from both, Martha said the best advice she has for a non-runner significant other is letting each other know what makes the other happy and working toward those goals.

"I would never ask him not to run because that would be like taking his soul away," Martha said. "It's about finding a balance, about what's going to make both people happy. It's sitting down and asking, 'Can we satisfy the runner's desires and passion with the partner's desires and passions?'"

We Don't Talk About Trail Running

When you love something, you want to share it with those you love. Take running. Runners love sharing their goals, training, miles, tales from run group, what the pros are doing, what they read, listened to, or saw about running, *insert endless examples here.*

If you paused at any point during that and sighed, you've likely been on the receiving end of a runner, and Stephen Ettinger, 33, wants you to know something:

"I've gotten the impression that it's a widespread problem among ultrarunners," he said. "Corrine and I have this anecdote that, at some point, I was like, 'You have to find some other people in the trail running community to talk about this stuff. Find an outlet. Talk about trail running with them because I can't listen to you talk about trail running all the time. It's driving me bonkers.'"

He's (mostly) kidding, but he's not wrong. If you put a quarter in a runner's jukebox, that song will play in its entirety. His wife, pro runner Corrine Malcolm, was guilty of it, and she heard that feedback. She's now a podcaster, author, editor-in-chief of FreeTrail, race announcer, Pro Trail Runners Association board member, and various other trail adjacent projects.

Ettinger gets his ultra stories in moderation now, and, with someone who lives and breathes the sport, he knows how important it is for her. It's a lot, but it's a healthy outlet runner's need, especially as Malcolm faced injuries in recent years.

"An injured runner is an unhappy runner," Ettinger said. "It's super frustrating for them, and it's hard to be the partner of someone who's frustrated because you don't want them to be sad and bummed out. How can you not when you can't do the thing you love? Like anyone, they need an outlet."

Ettinger has found his own outlet in recent years. It wasn't something he expected after retiring from professional mountain biking and going to medical school and doing his residency in San Francisco. But when the trails in the city weren't as accessible to bikes as running was, he ran with it.

Before that, the couple split up at trailheads to bike and run. Going together, he says, brought them closer. They understand that Ettinger could spend that time reviewing charts and Malcolm could be going faster to train.

He's not sure why, but he said he might even sign up for an ultra this summer.

"It's not my most favorite thing, but I do enjoy it," Ettinger said. His parting advice: "Never expect 10 toe nails. Expect weird tan lines, and make sure to give your dog a break from running every now and then."

Balancing 'Me Time' and 'Us Time'

Char Ozanic, 46, of Grand Junction, Colorado, is not a fan of running. She recalled bad experiences with the required elementary school mile. When asked if she'd ever run a race again now, she said, "I'm giggling so much it hurts. No."

Ultrarunning found its way into her life through her husband, Matt, 48. They have two boys, and when they moved out, running filled his rediscovered free time as a work destresser.

"By the time the boys left, we had already been in the schedule mode of practices, dinners, and booked weekends so we fell back into that rhythm again quickly," Char said. "But, instead of the boys, it was Matt."

There were mixed feelings initially. Matt had found a passion, but it involved hours they could otherwise spend together or visiting their boys. If this was going to be their life, compromises were a must. Mostly, they had to prioritize scheduling things they wanted or needed around, and not over, those of the other.

"We had a lot of sit-downs," Char said. "You can't get your feelings hurt about every moment you're expecting to get [with your partner] because I also have a life of my own. It's our schedule. It belongs to both of us. You just need to be mindful of each other."

Part of the adjustment was significant amounts of "me time," Char said. Matt usually does two 100 milers a year. This year, one is the Moab 240. Many nights after work and long-run weekends add up fast for Matt.

"You have to genuinely be okay with being by yourself," Char said. "I go see movies by myself all the time, especially movies Matt might hate, or have a spa day. I do a lot of mental health stuff when he's trekking some big miles."

Sometimes it can be tough to find time together, especially in big mileage weeks. Char said that sometimes that means combining "me time" with "us time."

"If I'm craving more us time, I'll go to the trail with him and aid him along the way," she said. "I get my 'me time' and I get time with him. Other times, I like kicking him out the door to read a good book. It's all about balance."

This is also the case for races. Char has only missed one ever for Matt. Travel, she says, is her favorite perk. "It brings us to so many places," Char said. "He'll sign up for a race in, like, Beaver Canyon, Utah. I've never heard of it. Then we go and it's so beautiful. When he's racing, I can go on these small hikes and venture out to do what I want, too. I Google things I can try."

His best advice for anyone dating a distance runner: "Always have snacks around. Easy to grab. Runners can go from wanting a snack to ragingly starving quickly. Trust me. Snacks."

Never Run to Impress

Who hasn't done something to impress a person they're dating? Justin Charboneau, 33, can relate. When he started dating his now-wife, Brittany, 34, in 2016, she was qualifying for the 2020 U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials with sites on going pro.

So, Justin did what any love-struck person would do in that situation: sign up for a half marathon. He completed it, plus some other races and triathlons, too. It wasn't his thing, but he kept up the charade because he thought Brittany wanted him to run.

But in 2022, they hadthe talk.

"I started a cookie company in 2019 and running stopped," he said. "I still do Peloton and cycling now, but I kept running sometimes, and it got to a point where Brit's like, 'Do you like running?' I said no. She was like, 'You don't have to be a runner.' It was a huge weight off my shoulders."

Though he doesn't run anymore, Justin admires the work Brit, and other runners, put in to complete these long distances. He experienced running firsthand, and he wasn't a fan, but what Brittany does inspires him. At the same time, it can be a challenge. Being Denver-based with most friends from the running community, running can dominate the conversation and the attention.

"I've felt a little bit not heard or lonely because Brit does so much," he said. "There were times early on when it felt like Brit was doing all these awesome things and everyone's telling me my wife is so amazing. I got to a point where I'm like, 'What can I do to get some attention?' Eventually, I stepped back and realized that this is us. It's our life. Everything either of us do is for both of us. She inspires me, and it makes me excited to celebrate with her and be her support system."

That same friend group has no judgments since Justin stopped running. He joins them for "Fun Club" after runs and he's heartily welcomed, he said. The only other challenge, Justin says, is working around a runner's schedule. Brit goes to bed early and Justin is a social night owl, so compromising is a must.

"Being social after work fills my bucket. Sometimes, that's completely opposite of what Brit needs during training," Justin said. "It's an interesting thing to navigate because we still want to spend time together, so how can we find those things that fill both our buckets? It's a challenge, but definitely doable."

Finally, his best advice for anyone dating a distance runner: "Always have snacks around. Easy to grab. Runners can go from wanting a snack to ragingly starving quickly. Trust me. Snacks."

Young Love on the Trails

We conclude with our youngest couple: Heidi Strickler, 33, and Hannah Gordon, 38, of Seattle, Washington, an 11-month-old relationship between two passionate outdoor lovers. Strickler is more the runner of the two, competing in ultras and spending days in the mountains. Gordon enjoys a three- to six-mile run here and there, but is more of an outdoor generalist with passions for hiking, biking, and rock climbing.

Together, they find love on and off the trails.

"I view our relationship as three relationships: Heidi with herself, me with myself, and us," Gordon said. "I think we're pretty aligned. We both have interests in certain things and would like to pursue those, and also share them. But that doesn't mean the other person needs to be 100 percent in it."

Each part of that trio requires intentionality and attention, Gordon adds. When she goes on her adventures, or Strickler goes on hers, they both return fulfilled in their passion and, in turn, better versions for their partners.

"I almost wonder if there's an independence level in both parties that works well for people who are partnered, with ultrarunning or some big passion," Gordon said.

At the same time, scheduling becomes intentional, too. Planning their passions is as important as planning to be together. For example, Tuesdays are set aside for just them. Outside of that, they work around friends, work, and being outside, to spend time together. Through communicating ahead of time, they make it work. One thing they haven't experienced yet, Gordon and Strickler said, was a big training block for Strickler.

"I see the potential conflict depending on how many races per year are being trained for if that gets in the way of what we're hoping for intentional time together," Gordon said. "I think I could see that would be something we would just need to talk about. I think it's still solvable."

Additionally, Gordon says that having someone with inner drive to do things like ultras is attractive.

"Watching Heidi, I see such joy and exuberance when she comes back from the mountain," she added. "For me as a partner, I am very thankful that I am with somebody who finds so much joy in the activity that she's born to do. I can see the joy on her face when she comes back and brings in the mud and she's just smiling and beaming that she got to get so dirty and run 30 miles in the cold - which makes no logical sense to me."

(03/05/2023) ⚡AMPby Trail Runner Magazine

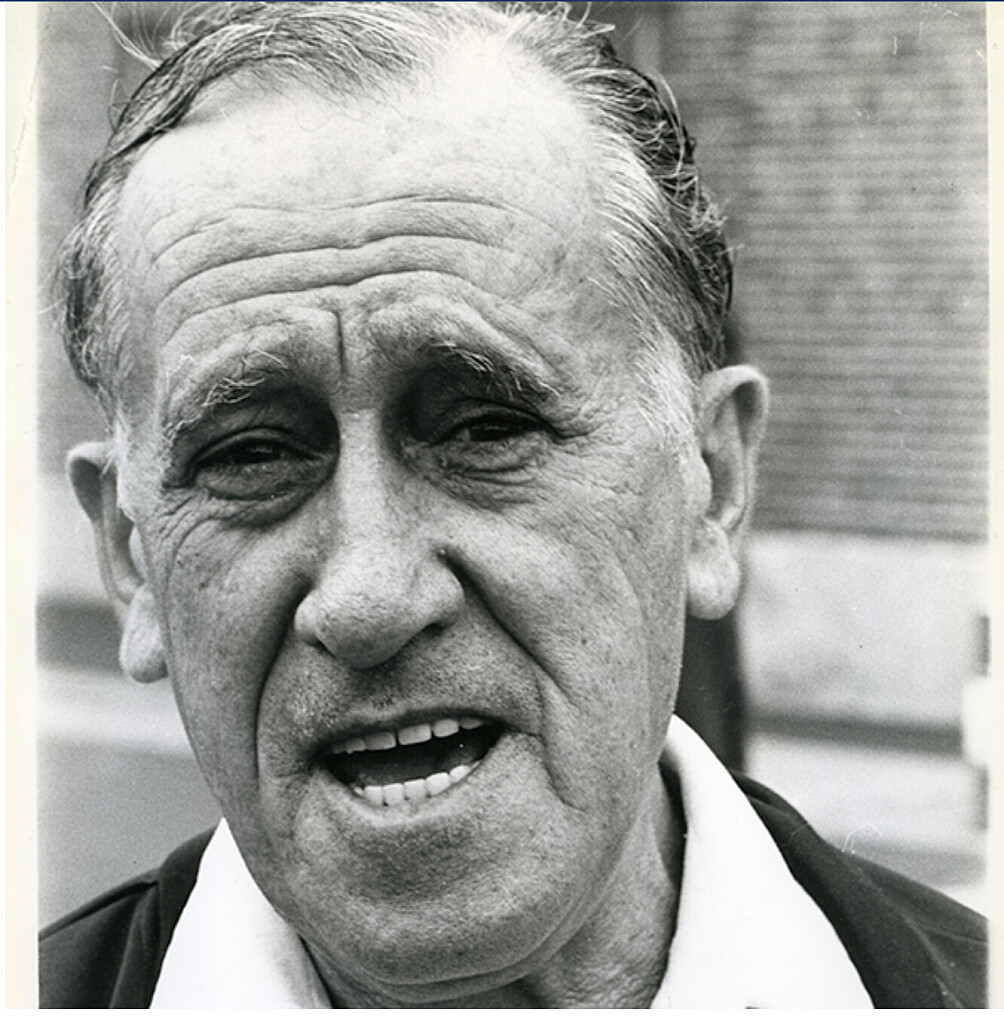

The 90-Year-Old Man Who Still Crushes 100 Milers

Don Jans clipped the curb with his car as he pulled into a rest stop in Texas. It was a minor incident that likely stemmed from the exhaustion of a solo, 2,000-mile drive home to Florida, after completing 127 miles at January's Across the Years in Phoenix.

Inspecting the damage, the 90-year-old Florida man was relieved to see none. So, he hopped in his sleeping bag for a few hours before waking up around 3 A.M. to get back on the road. A few miles later, the car rebelled.

"The temperature gauge was at the max, so I pulled off the interstate and shut it down," Jans said. "Around three or four in the morning, I get towed to a mechanic in Ozana, Texas, which is in the middle of nowhere. When I got there, I climbed back in my sleeping bag and the mechanics arrived around 7 A.M. and found me there. Unfortunately, they didn't do radiators."

Jans received another tow to another mechanic in town and was back on the road the next day after sleeping in that mechanic's lot that night. He would make it home a day or so later.

In a way, it's a fitting description of Jans as runner and person. At 90 years old, Jans finds ways and reasons to keep moving in his 10th decade on Earth, and his fifth running.

If he can do it, he'll do it. It might take a little longer than it used to, or, using one of Jans's many sayings and mottos, "Don't be getting in a hurry."

"I have no explanation for why I should keep running, but I highly recommend it to everybody," he said. "It's just great to be out there on the course, in the fresh air, and the training isn't a burden. I mean, if it's something you like to do, it's not punishment. If it's punishment, you need to find something you like. That's what we're here for right? To have fun."

A Wife, a Man, and a Van

Endurance goals have been top of mind for Jans since 1980. Then 48, he started running to lose weight. Realizing he enjoyed the challenge, he became a triathlete. One race turned into another, and he eventually qualified for and ran Kona in 1987.

The same happened when he transitioned to trails in the 1990s. He found new challenges and a community in running.

"The people in the ultra and running community are such a wonderful bunch to be around," Jans said. "Everybody helps everybody. They're just the salt of the earth. I said to myself that this was the place to be."

With the help of his wife Dorothy, they packed into the family van and found races to run and volunteer at all over the country. Though never a runner herself, Dorothy became the "ultimate crew chief" for Jans. She took extensive notes, took pictures of what Jans wore so he had a reference for future races, and stocked the van like a mini aid station on wheels for other runners in need.

"She was a super mom," said Sharon Jans, 67, Jans's daughter. "I have three brothers and three sisters, and caretaking people out was kind of her life. She just extended that to runners. She helped a lot of people here and there at so many races. Whatever they needed, she had it somewhere in that van. She loved it. It kept her busy."

While they mostly stuck to the Southeast near their Clearwater, Florida home, Jans racked up multiple ultra finishes a year after 1990, including the Umstead 100 (eight times), JFK 50 (also eight times), and Ancient Oaks 100, to name a few. He was in his 60s and 70s for the majority of these.

Then, it all came to a halt in 2009.

They first noticed it at a race. Jans came into an aid station and found Dorothy asleep in the van. She had never missed him or been asleep at any aid station before.

Soon after, Dorothy was diagnosed with lymphoma. When that seemed to be cured, another diagnosis followed.

"We went through a battle for five to six years," Jans said. "You lose track of time, and I'm not blaming the medical people. Once you think you're over one hurdle, there's another one. There's a continual series of disappointments, if you want to call it that. You just do it. We had been married for 60-some years, and for these next years, I was a full-time caregiver. Nothing else. You just do it."

When Dorothy passed away in October 2015, Jans didn't know what to do. He hadn't run in years while tending to his wife and best friend. He had a hip replacement and had done some swimming and walking, but nothing near what he used to. He wasn't sure if he'd ever run like he did.

A Comeback Story

Looking for something to occupy his mind and time, one conversation led to rediscovering his goals through discovering a new race.

Depending on who you ask in the family, you'll get a different story. Jans goes with his version in which one of his daughters, Marilyn Jans Schupbach, 69, alerted him to the existence of A Race for the Ages (ARFTA). The Tennessee-based race is essentially a timed, multi-day race but with a couple twists. Everyone 40 and younger gets to run the final 40 hours of the race. Anyone 41 and older is allotted a number of hours equal to their age. In 2018, that meant Jans, who was 85, got 85 hours to run.

"I was just trying to recoup mentally from losing my wife, so it was a distraction, get your mind onto something worthwhile," Jans said. "Marilyn told me, 'Why don't you try this and see how it goes?'"

Intrigued by the concept, Jans signed up, training around the roads in his new home in The Villages, Florida. He was also motivated by having someone to race with: Marilyn.

Jans had inspired her and Sharon to get into ultras in the 1990s, and Marilyn wanted to see if she could catch her dad. I signed up with him," Marilyn said. "That was my first and last time. I'm so much younger and he started 21 or 22 hours ahead of me. I never caught up with him. He ran 120 miles and I had 104. He was like 85 at the time, by the way."

While Marilyn hasn't returned, Jans has become a fixture at the event. He's run every single one since 2018, including 119 miles in 2022. He's also been able to convince his other daughter, Sharon, to join him for the last two.It may help that he pays her race entry and signs her up.

"I didn't think I could ever do that race," Sharon said. "Then, he just paid for my race entry and told me, 'You can do it. Give it a try.' I had done some 50Ks, but I had never tried anything like it. Since then, I've done a couple 100 milers. I even did Long Haul 100 in January with Marilyn. Dad missed it because he was tired from the drive home [from Across the Years]."

"I beat him by one mile," Sharon said. "He's 25 years older than me, and it took me until the final hour to catch up. He rests, but he never stops."

Most recently, he added Across the Years to his annual race calendar. At his inaugural run at age 90, he ran 127 miles during the six-day race. Rainy weather and cooler temperatures caused some hiccups, like a "frog strangling downpour," he said, leading to him "being old in a 1010 dome tent with wet clothes and cold weather."

Despite the conditions, he said it was one of his favorite race experiences. He said he'll just have to "come back next year with a different plan," which includes not driving home right after the race ends.

Going Further

Not everyone is blessed with mobility later in life. Genetics, previous injuries, and the wear and tear of life can build up.. For Jans, his abilities at 90 are a blessing, and he recognizes that.

Though not as fast as the people who, quite literally, run circles around him, he gets out there everyday anyway. Most importantly, he shows up on race day.

"Truth be told, you don't feel like you're 90," Jans said. "It's just a number. Even though you can't perform like you did 10, 15 years ago, I still feel the same way. When I wake up in the morning, I do. I don't say, 'Oh golly, I have to train.' I say, 'I want to go train.' It's a delight, not a punishment. I'm sure it's the same way for the guy who won the last-person-standing race at ATY. We wake up and say, 'Oh boy! We get another to go for a run.'"

His biggest opponent right now is cutoffs. The standard 30 to 36 hours aren't conducive for runners who need more time to hit their goals. While events can't go on forever, we are seeing more events that tailor to these needs.

In fact, Jans is seeking out his first 10-day race, and not because he wants more time to hit 100. His next goal after that?

"I'd like to do a 200-miler," he said. "I think I'd need a 10-day race to do it, which I don't think that's in the cards. A lot of races keep talking about doing a 10-day event, but I don't know if that's just scuttlebutt. I'll just keep trying to do my best if I can't find 10-day events. Just keep going."

(03/04/2023) ⚡AMPby Trail Runner Magazine

How Courtney Dauwalter Keeps Running Simple

In a world where fitness tracking devices and high-tech training plans dominate the running scene, ultrarunner Courtney Dauwalter has found success by keeping things simple.

Dauwalter's love for running started at a young age, with the Presidential Fitness Test in elementary school.

"I started running in elementary school when we had to run the mile for gym class," she said. "I remember loving it. I really liked how it felt to run, and I really liked how I could push myself as hard as I wanted."

In 1997, Dauwalter's passion for running evolved when she joined the cross-country team at her Minnesota high school. "When I joined the cross-country team, a whole social element got added to running that made me fall in love with it even more," she said.

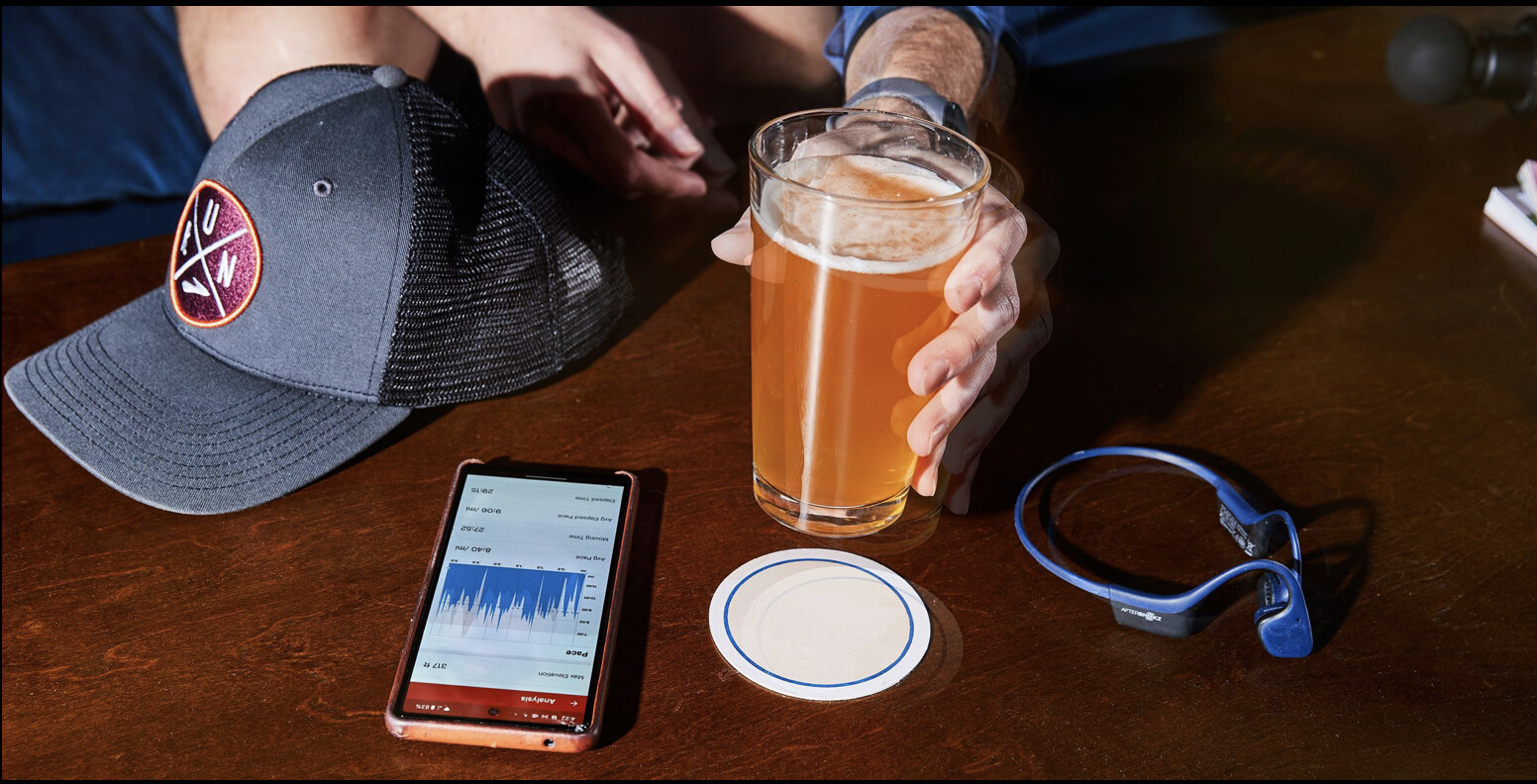

But as many runners know, it's easy to lose sight of the joy of running amidst the pressure to achieve personal records and track every metric imaginable. Unlike many in the endurance space, Dauwalter does not use Strava, but she does still think it's a great tool for others.

Dauwalter, now the top women's ultrarunner in the world, has found success by sticking to her roots and embracing a simple approach to training. She has not worked with a running coach since she her high school cross-country days. Her strategy includes a flexible training plan that allows for rest days, spontaneous runs, and a mindset that focuses on the joy of the movement. "I think it's important to stay in touch with why you love running," Dauwalter said.Dauwalter's evergreen approach is atypical. But should it be?

Her process has paid off, with impressive performances in ultra-marathons. But Dauwalter's success is not just measured in podiums and race times. For her, running is a way to connect with nature and others who share her love for the sport.

As we continue to navigate the complexities of modern fitness culture, perhaps we can learn something from Dauwalter's approach. By embracing the childlike joy of running and simplifying our approach to training, we may find that the movement becomes more meaningful and enjoyable.

Keeping Things Loose (After Coffee)

Unlike many of her peers, Dauwalter shuns the rigidity of a training regimen and doesn't obsess over the particulars.

"Every morning after coffee, I'll decide what my run is for the day based on how my body and brain are feeling," she said. "Sometimes that's a long run on some of my favorite trails, or summiting a local peak, or it might feel like a great day for hill repeats or intervals, and some days I won't really know what I'm doing until I leave the house and let my feet choose the route."

Her daily runs typically last between two and four hours, and, while she may know when a race is coming up, she decides what her training will look like based on how she feels physically and mentally.

"There are so many ways to train, enjoy, and go after running goals. Having a training plan, using devices and analyzing data, or not doing any of those things, are all great options," she explained. "I think it depends on the person and how they find joy. But I also think there is no downside to occasionally leaving the watch at home and heading out the door for a run where you just listen to your body and not worry about metrics."

Her general approach involves listening to her body and not following a predetermined plan, allowing her to focus on the experience rather than the results. For instance, if she's training for a race with a lot of climbing, she'll incorporate more mountain runs into her routine.Over the years, Dauwalter has focused on being more adaptive to her body. She stays in tune with her emotions and doesn't take things too seriously. She approaches her training with a sense of playfulness, which keeps her motivated and engaged.

Dauwalter's cheerfully unconcerned approach to training is the exact opposite of what you might expect from a world-class athlete. Rather than obsessing over sleep metrics and biomarkers, she keeps her routine flexible and listens to her body. She doesn't overthink her diet, instead opting to eat what looks good, sounds good, or is most convenient. Some of her favorites include nachos, pancakes, gummy bears, Snickers, root beer, etc.

"I almost always just go running without a structured plan. I am usually wearing a watch that can tell me data, but I am not looking at this during my run," said Dauwalter. "I find the most joy when I leave my house and let my feet be the tour guides."Without a predetermined plan, she's learned to tune in to her body and react accordingly. Her approach permits her to pay close attention to what her body tells her and avoid disregarding symptoms or signs that she should change course.

The basics of enjoying the processes are essential for Dauwalter. She does better when she's not holding too tightly to any piece of running. The flexibility of her training keeps things fresh and fun

Take a Break from the Gadgets

"Sometimes our gadgets can get in the way of our enjoyment of the run," said Dauwalter. "The gadgets are cool, but so is the simplicity of running."

Her primary approach helps in races when things inevitably get challenging. She speaks about turning to her mental "filing cabinet" and "telling herself jokes" to overcome the obstacles of the mind and body she's trained in.

Moreover, her decluttered training style extends to the simplicity of using breathing and mindfulness exercises to focus on the calm of the trails. Keeping it simple helps push through demanding times. Focusing on her breathing or looking at the trail where she's headed can bring peace in trying moments.

Dauwalter's intuitive running style may not be for everyone, but the approach can provide a refreshing change of pace. Dauwalter's lower-intensity mindset offers a powerful reminder that running can be as simple as putting on our shoes and heading out the door.

"It really can be just you out in nature with the sound of your breathing and footsteps, rolling with the terrain at whatever pace feels good that day," she said. "I try to run like this as much as possible."

(03/04/2023) ⚡AMPby Trail Runner Magazine

Japanese man runs 3:28 marathon in wooden sandals

Finishing a marathon is hard enough, but one Japanese runner pushed his limits at the 2023 Osaka Marathon, clocking a three-hour and 28-minute marathon while wearing traditional wooden Japanese geta sandals.

Takanobu Minoshima, a 47-year-old runner from Sapporo, averaged a pace of 4:56/km over 42.195 kilometres while wearing the wooden shoes and even had the word “Geta” as his name on his Osaka Marathon bib.

His final finishing time was 3:28:11 for 2,896th place (out of 10,000+ runners), which is only eight minutes shy of the 2023 Boston Marathon qualifying time of 3:20:00 for his M45 to 49 age group.

Geta are traditional Japanese sandals that are often paired with the yukata (robe) for informal occasions, such as summer festivals. The geta has a slab of wood attached to the foot with strings or ribbons and rests on a sturdy piece of wood (that’s a little higher than the maximum stack height allowed by World Athletics!). We have to hand it to him for being able to stay on his feet for an entire marathon while wearing these.

This isn’t the first time Minoshima has raced wearing geta. In 2019, he ran a 100K ultra race in 13 hours and 45 minutes at the Kamalai Shrine 100 in Taiwan. He has a marathon best of 2:59:20 from the Hokkaido Marathon in 2014, when he wore regular running shoes.

(03/02/2023) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

Five times non-running sports stars smashed foot races

Have you ever wondered if your favorite athletes in other sports could make it as elite runners? They’re at the top of their own sports and they’re clearly athletically gifted, so it wouldn’t be the biggest surprise if they could transition into running. Well, we can’t say for sure which athletes could have had success on the track or road if they’d dedicated their careers to running, but thanks to a few races over the years, we’ve been able to see a few sports stars in action.

Here are the top five times athletes from other sports crushed it in running races.

Arjen Robben

In November, former Dutch soccer star Arjen Robben ran the Zevenheuvelenloop, a popular 15K race in Nijmegen, Netherlands. Robben played for some of the top clubs in Europe, including Real Madrid and Bayern Munich, and he made it to the World Cup Final in 2010 with the Dutch national team. In Nijmegen, he ran the 15K course in 55:01, a time that works out to a pace of 3:40 per kilometer. As a player, Robben was known for his speed on the pitch (in 2014, he reached a top speed of 37 kilometers per hour during a World Cup match), but few people knew he could lay down such an impressive result on the roads.

Wayne Gretzky

In 1982, Wayne Gretzky (you might also know him as the best hockey player of all time) ran an exhibition race in Sweden alongside Pelé, Sugar Ray Leonard and Björn Borg—some of his fellow sports stars of the day. The race was 60m, and right from the gun, there was no doubt that it was Gretzky’s to win. He blasted off of the starting blocks and flew away from his competitors, eventually crossing the line in 7.24 seconds. (Granted, he was considerably youner than his competiors at the time.)

Alex Honnold

Alex Honnold is one of the world’s most famous climbers, thanks mainly to his 2017 free solo (meaning he climbed without ropes) ascent of Yosemite’s El Capitan and the subsequent Oscar-winning film, Free Solo, which documented his climb. It turns out that Honnold is not just a rockstar climber, as he proved he can run pretty quickly (and far) when he wants to. In November, he ran the Red Rock Canyon 50K Ultra near Las Vegas, racing to a sixth-place result in five hours and 23 minutes.

Therese Johaug

Norwegian cross-country skier Therese Johaug has the most impressive transition to running on this list, thanks to a couple of 10,000m races she ran in 2019 and 2021. Johaug is a six-time Olympic medalist (four of them gold) and a 19-time world championship medalist (with a whopping 14 gold). She entered the 2019 Norwegian 10,000m championship on a whim (after the race, she told reporters she hadn’t run on a track in 11 years) and ended up winning the title in a championship record of 32:20.86. That time was the fifth-fastest result in Norwegian history, but Johaug didn’t stop there. She ran another 10,000m in 2021 and improved her PB to 31:32.88, which is the fourth-best on Norway’s all-time list.

Chris Froome

British cycling champion Chris Froome may not have run an actual race, but in the 2016 Tour de France, he did resort to running the course for a stretch following a crash. Froome had a kilometer to go in that day’s stage when he collided with a motorcycle. His bike was wrecked and couldn’t have gotten him to the finish, so he turned and ran uphill until his team caught up and gave him a new ride. Froome lost the stage that day, but he won the Tour de France overall, thanks in part to his on-the-spot decision to run.

(02/28/2023) ⚡AMPby Ben Snider-McGrath

Gerda Steyn hopes for a fourth win at Two Oceans

With 50 days to go to the “world’s most scenic race”, the Totalsports Two Oceans Marathon (TTOM) is shaping up to be an elite fest with a stellar field.

Once again, any athlete who breaks the record in the Men’s or Women’s Ultra Marathon Race can look forward to a record incentive of ZAR 250,000 (EUR 12,800) in cash.

With prize money for the Totalsports Two Oceans Ultra Marathon at ZAR 250,000, any record-breaker could look forward to a massive ZAR 500,000 pay day on 15 April 2023.

Nkosikhona “Pitbull” Mhlakwana, who made a sensational Totalsports Two Oceans Marathon debut last year, lived up to his nickname showing tremendous tenacity finishing in a superb second place behind Ethiopia’s Endale Belachew, with Sboniso Sikhakhane coming in third.

As expected, the 30-year-old considers himself to be a bit stronger and wiser, and determined to do one better this year.

“My main goal is to improve my position from last year,” says Mhlakwana.

The Hollywood Athletic club athlete says he picked up invaluable experience last year and now knows what to expect.

Another epic battle for supremacy is expected this year in the women’s Ultra. Gerda Steyn and ASICS athlete, Irvette van Zyl, who both shattered Frith van der Merwe’s longstanding women’s 56km record of 3:30:36 set in 1989, have confirmed they will line up again this year.

Steyn (3:29:42) became the first woman to run the grueling route in sub 3:30. The 32-year-old returns this year in a bid to be crowned champion for an unprecedented fourth consecutive time, while running as the current record-holder.

The three-time champion, who will be running in her permanent blue number, 6067, will, however, not have it all her own way, with the 34-year-old Van Zyl (3:30:31) finishing just a few seconds behind her last year. The purists can rest assured that Van Zyl will come out guns blazing and ready for another classic battle with Steyn.

Steyn says she is very excited to be preparing for the Totalsports Two Oceans Marathon again.

“This will be my fifth time running the race, and I am really hoping for a fourth win after taking the title three times in a row now. Last year was such a highlight for me. I am just hoping to repeat that experience and that win. The preparations until now have been going well, which makes me even more excited for the race,” she says.

With 50 days to go before Race Day, Steyn feels the next three to four weeks will be crucial to her preparations.

“Another very exciting aspect of this year’s Totalsports Two Oceans Marathon is that it will be the first time that I will be running in my permanent number in any race.

“Usually, one has to complete 10 Ultra Marathons, but I managed to win the race three times, therefore earned a blue number. This brings a very special touch for me. At the moment I am preparing for the Two Oceans in Johannesburg. The energy level and excitement is at an all-time high," adds Steyn before wishing all runners everything of the best with the final stretch of preparations.

If excitement levels are high for the Ultra on the Saturday, the battle for supremacy in the Half Marathon on Sunday, 16 April, will be even higher. The likes of previous winners Stephen Mokoka, Elroy Gelant, as well as Precious Mashele from the Boxer Athletic Clubs, have all confirmed their entries. Moses Tarakinyu from Zimbabwe is back to defend his title with Entsika’s Desmond Mokgobu also looking to improve on his third place from last year.

Last year’s winner, Fortunate Chidzivo, will not be lining up to defend her title in the women’s Half Marathon this year, which leaves the race wide open for a new champion to be crowned.

(02/28/2023) ⚡AMPby AIMS

Two Oceans Marathon

Cape Town’s most prestigious race, the 56km Old Mutual Two Oceans Ultra Marathon, takes athletes on a spectacular course around the Cape Peninsula. It is often voted the most breathtaking course in the world. The event is run under the auspices of the IAAF, Athletics South Africa (ASA) and Western Province Athletics (WPA). ...

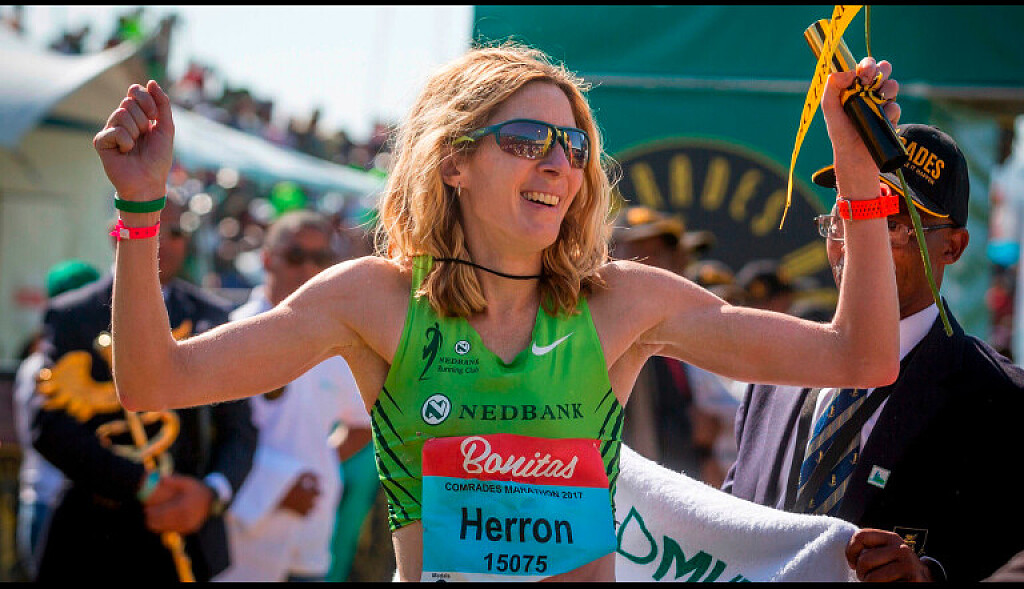

more...Ethiopian runner breaks women-only world 50K record in South Africa

Ethiopia’s Emane Seifu Hayile broke the women-only 50K record at a race in South Africa on Sunday, running 3:00:29. Competing in the Nedbank Runified Breaking Barriers Ultramarathon in Gqeberha, a coastal South African city, Hayile shaved almost four full minutes off the previous women-only world record. She was less than a minute off American Des Linden‘s 50K women’s mixed-gender race world record of 2:59:54 from 2021.

Women-only races mean that there are no men in the field. Because of the potential benefit that female runners can receive while pacing off male athletes, World Athletics recognizes two types of records for road races, making it possible for Hayile’s 50K record to co-exist with the one belonging to Linden, which she ran alongside male pacers.

Despite running in a women-only race, Hayile came extremely close to claiming the outright 50K world record, finishing mere seconds behind Linden’s time. She ran with two fellow Ethiopians and a Swedish athlete in the opening stages of the race, passing through 10K in just over 36 minutes and 15K in 54. At around 20K, Hayile and her compatriots dropped the Swedish runner and carried on in a three-way battle. At the halfway mark, the trio clocked a split of 1:30:28, just shy of sub-three-hour pace.

Over the next 10K or so, Hayile dropped her two remaining challengers, and by the 40K checkpoint she was almost a minute ahead of second place. She clocked a 2:32 marathon and managed to accelerate as she neared the finish, crossing the line just north of three hours. Hayile won the race by six minutes and bettered the women-only record by four minutes.

“I am lost for words and don’t know how to describe it,” Hayile told World Athletics after the race. “All in all, it was an exciting event. I’m very happy.”

In the men’s race, South Africa’s Tete Dijana ran a course record of 2:39:04. This result is the second-fastest 50K of all time, sitting just 20 seconds behind American CJ Albertson‘s world record of 2:38:44, which he ran in Oct. 2022.

(02/27/2023) ⚡AMPby Ben Snider-McGrath

After 113 straight ultramarathons, Candice Burt still isn’t done

American ultrarunner and race director Candice Burt completed a 50K on Sunday morning. She did the same thing on Saturday, and also on Friday, and for 110 days before that. In November, Burt, who hails from Boulder, Colo., decided to shoot for the Guinness World Record for most consecutive ultramarathons.

The previous record was 23 days, a total Burt surpassed about three months ago, and she’s still going, with a whopping 113 consecutive ultramarathons to date.

When Burt started her ultramarathon record attempt, the number to beat was 11 days. The total has reportedly been changed on multiple occasions since Burt set out to break the record, and it currently sits at 23 days on the Guinness World Records site. The record Burt was chasing and has since beaten is listed as a female and non-binary mark, but she has also smashed the male record of 21 days.

As Burt noted on her website, she can’t recall exactly what sparked her desire to chase this record, but she said it could have been after she saw ultrarunner Jacky Hunt-Broersma run 104 marathons in a row in 2022, or Alyssa Clark, who ran 95 straight marathons in 2020.

Burt added that it may have been her own previous hiking and ultrarunning feats that convinced her she could complete a challenge as big as an ultramarathon streak. But it looks like she could keep going for a while.

While Burt has now produced an incredible streak of more than 100 days, she wrote that she wasn’t even sure if she could make it to the record. “From the very start of considering the streak I just wanted to be open to doing it for as long as my body would hold up,” she wrote. “I wasn’t sure if that would even be the record-breaking 23 days, but I wanted to try.” Despite this uncertainty, she said that her goal was to go “much, much bigger” than 23 days, and even early in this journey, a result in the triple digits was on her radar.

Burt is the race director of popular ultras like the Moab 240 and Bigfoot 200.

(02/27/2023) ⚡AMPby Ben Snider-McGrath

Courtney Dauwalter dominates Transgrancanaria in record-setting fashion

American ultrarunning star Courtney Dauwalter proved why she’s the athlete to beat on the ultramarathon scene after an incredible performance at the Transgrancanaria in Spain’s Canary Islands on Saturday. Dauwalter crossed the finish line of the 128K course in 14:40:39, a course record and almost two full hours ahead of second-place finisher (and Canadian) Jazmine Lowther. The Transgrancanaria marked the start of the 2023 Spartan Trail World Championships series.

Dauwalter’s dominance

Everyone in the trail and ultrarunning communities knows that Dauwalter is an all-time great, but it’s still awe-inspiring when she shows up to hotly contested races and dominates her competitors. As listed on the trail and ultrarunning results database UltraSignup, Dauwalter entered the Transgrancanaria on a 14-race win streak that stretches all the way back to March 2021. (The last time she failed to reach the top step of the podium came at the Barkley Marathons.) She added yet another win to her resume on Saturday, extending that amazing streak to 15 and counting.

The Transgrancanaria is held on Gran Canaria, one of the Canary Islands, and it takes athletes along an arduous 128K course that features more than 7,000m of elevation gain. Dauwalter started the race chasing Lowther and Spain’s Claudia Tremps, who led for the opening stages of the run. About a quarter of the way into the race, Dauwalter took control of the field and moved into first place. From that point on, she never looked back, leaving Lowther and Tremps to battle it out for second place.