Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #Shannon Rowbury

Today's Running News

'It kills me inside'- British runner on how competing at the dirtiest race in Olympic history forced her to retire

The 2006 Commonwealth Games 1500m champion explained how competing in the dirtiest race in history forced her into early retirement.

Retired English middle-distance runner Lisa Dobriskey has detailed how having to compete against runners who cheat fueled her desire to retire before she was ready.

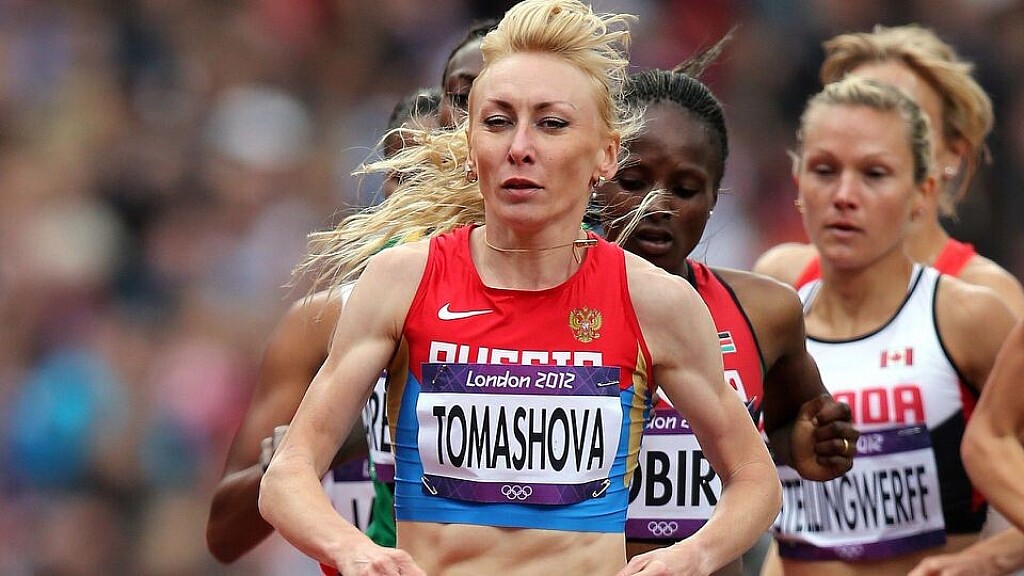

The former Commonwealth Games champion recounted the 1500m final race at the London 2012 Olympic Games where almost every runner was banned for doping. The winner of the race, Asli Cakir Alptekin was banned in 2017, for a third-time offence, this time for life.

The second-place finisher, Gamze Bulut was also banned for four years in 2016, meaning the athlete who finished third at the time, Maryam Yusuf Jamal, was elevated to first place. Tatyana Tomashova who finished fourth was banned for two years in 2008.

Abeba Aregawi who finished fifth was suspended in 2016 but that was lifted. Shannon Rowbury was elevated to third place in the race. Natallia Kareiva was also banned for two years in 2014 while Lucia Klocova was since elevated to fourth. Ekaterina Kostetskaya was also banned for two years in 2014 with Lisa Dobriskey now elevated to fifth-place. Laura Weightman, Hellen Obiri and Morgan Uceny were also in that race.

Lisa Dobriskey revealed that athletes constantly cheating impacted her career and she opted to leave other than having to constantly fight for justice and nothing right seemed to be happening.

“Trying to get back I thought, ‘What’s the point?’ I lost my heart and it played a big part of my decision to walk away. I have never, ever got over it. There’s not a day that goes by when I don’t think about it. It kills me inside,” Dobriskey said as per The Times.

“I’m not someone who makes that sort of comment lightly. I knew my sport so well and I knew what I was saying was grounded and true. It was a case of, ‘I’m telling you these people are cheating,’ but my voice just got crushed and I was made to look foolish and bitter. From the outside I can understand I looked spoilt, but it took courage to speak out, and that got trampled on.”

The doping menace hurt her so bad that she admitted she could not watch the Paris Olympic Games. Dobriskey disclosed that she never wanted to stop running but her body had had enough and was not going to condone that.

Even after a series of attempts, she could not get herself to get back on track since it was mentally draining. She has lost a lot of faith in what the future holds when it comes to track and field as she believes the game is rigged.

“I just can’t. It hurts so much. I didn’t want to stop running but my body gave up. I tried to get back to watching but it’s just too painful and makes me spiral and get in a mess mentally. Now 2012 feels almost comical. I was fifth but never finished fifth,” she said.

“I just don’t know. It’s hard to trust a system that let you down so many times. I’m detached from it now. I’ve moved on.”

by Abigael Wafula

Login to leave a comment

The sport we love is going to be ruined unless something is done. It seems to me if we can not make sure whoever is on the starting line is legal at that moment or not. We can not keep banning people after the fact. Something needs to change. - Bob Anderson 11/26 7:54 am |

Russia's Tatyana Tomashova stripped of silver in historic 2012 Olympic 1500m final doping scandal

Former Russian athlete Tatyana Tomashova stripped of 2012 Olympic silver for doping marking a significant scandal in athletics history.

Former Russian athlete Tatyana Tomashova has been stripped of her 2012 Olympic 1500m silver medal following the reanalysis of doping tests that revealed the use of prohibited substances.

The decision was announced on Tuesday by the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS). At 49, Tomashova has faced a severe setback with a 10-year ban in addition to losing her Olympic medal.

The CAS statement detailed the tests conducted out of competition on June 21 and July 17, 2012, which showed traces of anabolic steroids.

These findings led to the disqualification of all Tomashova's competitive results from June 21, 2012, to January 3, 2015, including the forfeiture of titles, awards, and earnings.

"The Sole Arbitrator in charge of the matter found to her comfortable satisfaction that Ms. Tomashova committed an Anti-Doping Rule Violation (ADRV) in relation to the 2012 Samples through violations of Rule 2.2 of the 2021 WA Anti-Doping Rules (WA ADR) (Use or Attempted Use of a Prohibited Substance or a Prohibited Method)," the CAS detailed in their release.

Further aggravating Tomashova's case was her doping history, including a previous two-year suspension in 2008. The arbitrator cited this history in deciding the severity of the sanctions.

"Turning to the sanction, taking into account a previous ADRV committed by Ms. Tomashova in 2008, the Sole Arbitrator determined the appropriate sanction applicable to multiple ADRVs to be the imposition of a ten-year period of ineligibility, commencing on this day, the date of the CAS decision, as well as the disqualification of all competitive results obtained by Ms. Tomashova from 21 June 2012 until 3 January 2015, with all resulting consequences, including the forfeiture of any titles, awards, medals, points, and prize and appearance money," the statement added.

This scandal has cast a shadow over what has been referred to as one of the most contentious races in Olympic history.

The 1500m final at the London Olympics was particularly notable for its multiple disqualifications.

Originally finishing fourth, Tomashova had been upgraded to silver after the first and second place finishers, Asli Cakir Alptekin and Gamze Bulut of Turkey, were also disqualified for doping violations. With further disqualifications of Natallia Kareiva and Yekaterina Kostetskaya, the race's initial lineup has been largely overturned.

Bahrain's Maryam Yusuf Jamal, who initially crossed the finish line third, ultimately received the gold medal.

The reshuffling continues down the line, with American runner Shannon Rowbury, who finished sixth, now in line to receive the bronze medal.

The CAS acted as the primary decision-making authority in this matter, stepping in for the Russian Athletics Federation, which remains suspended by World Athletics (formerly IAAF).

by Festus Chuma

Login to leave a comment

The former Nike Oregon Project changes team name to Union Athletic Club

One of the world’s best-known professional running clubs has found a new name after the Nike Oregon Project was abolished, coincident with the four-year ban of ex-head coach Alberto Salazar. The new name, Union Athletic Club, was announced on the Elevation Om YouTube page and confirmed by Chris Chavez on Twitter on Thursday.

After Salazar’s dismissal, the group remained intact through the past three years under coach Pete Julian.

Julian is currently the coach of many of the world’s top athletes, such as Suguru Osako, Shannon Rowbury, Raevyn Rogers, Jessica Hull, Donovan Brazier and Craig Engels.

He spent three years coaching at Washington State University before moving to the Oregon Project in 2012, where he was the assistant coach to Galen Rupp, Matt Centrowitz, Mo Farah and Canadian record holder Cam Levins.

The 2021 NCAA indoor 800m champion and Australian Olympian Charlie Hunter will be the newest member of the group.

Union Athletic Club is based out of Oregon and sponsored by Nike Running.

Login to leave a comment

Some Veteran Pro Runners Are Making Less This Year, and They're Ditching the Sport

Many athletes are confronting a bleak financial reality. Some are quitting the sport entirely.

What do Noah Droddy, Ben True, and Andy Bayer have in common?

They’re all ranked among the top 10 Americans of all time in their events—Droddy in the marathon, True in the 10,000 meters, Bayer in the steeplechase.

How Much Do Pro Runners Make? For Some Veterans, It’s Less This Year

And they were all dropped by their sponsors at the end of 2020.

This news took a while to seep out—after all, athletes don’t tend to publicize it when their sponsors reduce their pay or stop supporting them altogether. But Droddy, 30, and True, 35, have been open about their status and confirmed it in calls with Runner’s World (both had been sponsored by Saucony), and Bayer told the Indy Star that Nike dropped him and he has left the sport, at age 31, for a job in software engineering.

Droddy—one of running’s most recognizable figures in races with his long hair, backward baseball cap, and habit of losing his lunch at marathon finish lines—summed up his situation in a tweet on February 19.

Is he right? Is it typical for top runners, at the height of their careers, to lose financial backing from shoe companies? Or is this an anomaly at the end of an unusual, pandemic-marred 15 months?

Runner’s World had conversations with eight athletes, four agents, two marketing employees at brands, and three coaches to get a sense of the current economics for athletes. They painted a complex picture.

Are most pro runners broke?

Many are just getting by. For years, America’s pro runners have been on shaky financial footing. With the exception of those who win global medals or major marathons, distance runners often struggle to earn enough money to pay for their essentials (rent and food), plus cover all their running-related expenses, such as coaching, travel to races and altitude camps, health care, gym membership, and massage.

Over the past year, the pandemic has erased lucrative racing opportunities. Additionally, shoe companies have been reevaluating their sports marketing budgets, from which runners are paid. Experts say that the result has been an increasing bifurcation between the sport’s haves and have nots.

The most successful, those destined for the Olympic team or starring on the roads, are earning generous base payments and bonuses for setting records or winning. Many of the rest are scraping by, with smaller contracts, if any, and they’re supplementing their shoe company earnings with jobs.

Running’s middle class, much like America’s, is shrinking.

The exception is runners who belong to a single-sponsor training group, like those in Flagstaff, Arizona (Hoka); Boston (New Balance); and Portland, Oregon (Nike). In those cases, coaching, travel, and training camp costs are absorbed by the club, easing the financial pressure on athletes and making it possible for them to pursue the dream.

Brands these days appear to be more eager to devote dollars to groups and the athletes who train with them, rather than individual athletes training on their own in different locations. That presents a quandary for midcareer runners who have achieved a level of success. Faced with the loss of a sponsorship, they aren’t always willing to pick up and move to a new town and a new coach.

What do contracts look like?

If you’re a top runner in the college ranks, and you’ve won multiple NCAA titles at the Division I level, shoe companies—Nike, Adidas, Brooks, Saucony, Hoka, and others—will usually come calling, offering more than $100,000 a year for multiple years, with a spot in a group or a stipend to pay your coach. Those companies are betting on those NCAA champions to be Olympians of the future.

Dani Jones, for instance, won three individual NCAA titles at the University of Colorado, and she signed with New Balance at the end of last year. Her agent, Hawi Keflezighi, said she entertained competing offers from other companies.

A midcareer athlete with a breakthrough performance—hitting the podium at a major marathon or making an Olympic team, for instance—might also be rewarded with a base contract worth $50,000 to $100,000.

The top sprinters earn even more (although their careers are typically shorter). Usain Bolt famously made millions, and Canadian sprinter Andre De Grasse was 21 when he signed a deal worth $11.25 million—before bonuses—from Puma in 2015, the Toronto Star reported.

The payouts drop significantly after that. Let’s say you’re a distance runner, but you haven’t been able to get a big win in college, although you’ve come close. The lucky ones are looking at deals for about $30,000 to $75,000 per year.

Your agent takes a 15 percent cut of that. And this base salary most often comes without benefits: no health insurance, no 401(k). As independent contractors, pro runners are paying all their own taxes. (In contrast, traditional full-time employees have half of their Social Security and Medicare taxes paid by the employer.)

Many young runners out of college join pro groups, and they’re not making anything beyond free gear and coaching. Others might get a stipend worth $10,000 or $12,000 a year.

The contracts typically sync with the Olympic calendar. At the end of 2020, many athletes’ contracts were expiring—even though the Olympics didn’t happen. That’s how Droddy, True, and Bayer were dropped. Shannon Rowbury, a three-time Olympian, told Track & Field News her deal with Nike was extended for one year, two if she makes the Olympic team this summer.

If an athlete has a good Olympics, the sponsoring company often has an option to extend the deal for an additional year, which includes the world track & field championships. It’s at the company’s discretion—not the athlete’s.

Parts of the sponsorship model appear to be changing, but slowly. When NAZ Elite announced a new deal with Hoka last fall, it included health insurance for the runners. Similarly, members of Hansons-Brooks in Rochester, Michigan, get health insurance if they work in the Hansons running specialty stores. And last May, Tracksmith brought Mary Cain and Nick Willis on as employees at the company—Cain in community engagement, Willis as athlete experience manager—with the plan that both would continue to train and race at an elite level.

Why doesn’t anyone know exactly how much runners are making?

As part of these deals, athletes have to sign non-disclosure agreements (NDAs), promising to keep the terms quiet. If an athlete violates the NDA, the sponsor can void the contract—or sue for breach of contract.

This is, in fact, similar to other sports. In basketball, LeBron James is being paid $39.2 million this season by the Los Angeles Lakers. But he also has an endorsement deal with Nike, and the exact structure of that is unknown.

In running, prize purses are publicized—$150,000 for winning the Boston Marathon, $25,000 for being the top American at New York in 2019, $75,000 for winning the Olympic Marathon Trials.

But as in other sports, the terms of the sponsor deals are kept mum. And appearance fees at major races, as well as time bonuses within those appearance fees, which represent a major source of income for road runners (mainly marathoners), are also mostly unknown.

Athletes feel that the silence around sponsor contracts and appearance fees puts them at a disadvantage—it’s hard to know their market value. Yes, they can—and do—have quiet conversations with peers about it. But lacking broad knowledge, they lack power.

And as a result, the industry is rife with rumors and assumptions. Athletes’ values are often inflated through the grapevine.

“I think it is very similar to the dynamic that would occur if no one knew the price of home sales,” Ian Dobson—a 2008 Olympian who ran for Adidas and Nike during his pro career, which ended in 2012—told Runner’s World. “How could you ever be confident in a sale price if you didn’t know what any other homes in your neighborhood were selling for? Granted, we don’t know every detail of every home sale in the neighborhood, but it’s certainly helpful to know in general terms the dollar amount that these are going for so that we can all understand what value our home might have.”

Also, athletes keep quiet when their circumstances change. They feel embarrassed. One athlete told Runner’s World, “No one in track wants to be the one to say, ‘I got dropped,’ or ‘I got reduced.’ It's all taboo.”

Even so, $30,000 is nothing to sneeze at—especially for a job that’s about pursuing individual goals.

No, it’s not. But not every contract is structured the same way.

Some pay that base amount, no matter what. Other contracts penalize athletes with reductions if, for instance, they don’t finish in the top three in the country in Track & Field News rankings, or if they get injured and can’t race a certain number of times per year.

That’s why numerous Nike athletes seemed to be eagerly seeking racing opportunities of any kind last summer amid the pandemic. Marathoner Amy Cragg raced a 400 meters at an intrasquad meet on July 31, and finished in 90.15 seconds—6:00 pace—presumably to check a box on her contract. On August 7, she ran 800 meters in 3:03.85. The record of those races are in her World Athletics profile.

A Nike spokeswoman, when asked about athletes racing in 2020 to meet contractual obligations, responded: “We do not comment on athlete contracts.”

Time bonuses, once seen as a reliable way to beef up athletes’ base payments, are also becoming less frequent or harder to hit, as shoe technology improves and fast times become more common, according to one agent.

What role do agents play?

For athletes who have never previously had a sponsorship deal, it’s almost impossible to secure one without the help of an agent, who can get in the door at all the major brands.

For American distance runners, there are nine main agents—all men—negotiating the deals (Keflezighi, Josh Cox, Paul Doyle, Ray Flynn, Chris Layne, Dan Lilot, Tom Ratcliffe, Ricky Simms, and Mark Wetmore). Karen Locke, one of the few female agents in track and field, represents a few distance runners among her roster of clients in field events.

Of course, all the prominent agents—who have multiple clients across multiple brands and at various stages of their athletic careers—have data about what athletes are worth. But they have a duty to each one to maintain confidentiality about the specifics of that deal.

Agents bring to their athletes a broad picture of the market and what each might command, providing advice to those considering offers: Yes, this a fair offer, a solid deal. Or no, you can do better.

They also help get athletes into competitive track races like the Diamond League and elsewhere, or into the World Marathon Majors. They can handle travel arrangements to meets and help to make sure records get ratified. Generally, their role is to go to bat for athletes, no matter what they need.

For their services, they take 15 percent of everything an athlete earns: sponsor deals, appearance fees, and prize money, no matter how small the race or winnings.

Agents are supposed to negotiate on behalf of each client individually, but athletes have no idea if that’s happening. Are they being used as part of a package deal? Thrown in at a minimal rate as a thank you to a brand for giving a generous deal to a superstar? Or, on the upside, getting a small appearance fee from a major marathon that they wouldn’t be able to get into on their own, because they have the same agent as a mega-star?

“Agents want to bring in the most money for their combined athletes—if they manage 20 athletes, they’re trying to bring in the maximum money they can across 20 athletes,” one athlete told Runner’s World. “That doesn’t necessarily mean they’re trying to maximize for each individual. The difference between earning $20,000 a year and $30,000 a year is profound in terms of your ability to actually train as a professional. But it translates into a small amount [$1,500] for the agent.”

Why is the market tricky right now?

The pandemic caused upheaval in marketing budgets. Also, the people who work in marketing at shoe brands can be inexperienced in the running industry, and turnover often runs high at those positions, jeopardizing relationships between athletes and brands that have lasted years.

The marketing budget questions are not limited to running, said Matt Powell, a sports business analyst and vice president for NPD.

“I think brands are taking a more circumspect view of endorsement contracts in general—whether it’s teams, leagues, or individual athletes,” he said. “They’re [questioning whether] they’re getting the return on that investment.”

Nike is rumored to have cut its marketing budget for running, amid layoffs at the company. Nike did not return an email from Runner’s World seeking clarification on the budget or the numbers of runners it currently sponsors.

Although Nike’s superstars are said to be fine and not facing any reductions in their deals, one Nike athlete, a 2016 Olympian, told Runner’s World, “It’s pretty much assumed that everyone is getting less.”

And it’s believed that several of these contracts are for shorter periods of time than they might have otherwise been: through the world championships in 2022 in Eugene, Oregon, instead of through the next Olympics in 2024.

In answer to questions from Runner’s World about True and Droddy—as well as rumors about a new Saucony-sponsored training group—Saucony responded with an emailed statement from Fábio Tambosi, Saucony’s chief marketing officer:

“At Saucony we believe you cannot have a sports brand without the inclusion and authentic connection with athletes. We are excited about the evolution of Sports Marketing as a brand pillar for years to come, and remain committed to building an athlete strategy that aligns with this goal.”

Good news abounds, too

On the positive side for distance runners, Puma has re-entered the distance running market. Molly Seidel was lured from Saucony to Puma, and Aisha Praught Leer told Women’s Running she signed a “big girl contract” with Puma. Additionally, the company started a group in North Carolina, coached by Alistair Cragg and with three athletes so far.

The shoe company On has also invested heavily, starting a new team in Boulder, Colorado, coached by Dathan Ritzenhein and with athletes like Joe Klecker and Leah Falland.

Keira D’Amato, 36, signed her first pro contract, with Nike, after a string of impressive performances during the pandemic on the track and roads. She has kept her job as a realtor.

Keflezighi sees an opening for apparel brands that don’t have footwear to sponsor more athletes. Women’s apparel company Oiselle has done this for years, and Athleta is now sponsoring Allyson Felix. Could a menswear company be far behind? These arrangements leave athletes free to choose their own running shoes, which can be advantageous as shoe technology advances so quickly.

Why do brands have pro runners anyway?

Beyond the individual dollar amounts in contracts, brands seem to be rethinking what the role of a professional athlete is. Is it to inspire with performances, and hope those performances translate into shoe sales? Or is it to connect with fans on social media and promote product sales that way?

“You have to kind of look at it big picture,” True told Runner’s World. “These companies aren’t giving athletes money for charity; they’re doing it for a marketing investment and they’re looking for a return on their investment. And currently—and this is not ideal, in my mind—you look at the rise of social media and influencers. They are very inexpensive for marketers to go after and they get their products in front of a lot of eyeballs.”

A 2:20 male marathoner who also has a drone and a great Instagram account or YouTube channel might be gaining followers, True said, while a 2:05 marathoner is training hard and devoting his craft toward the next race.

“The average person, they don’t understand that 15-minute difference,” he said. “One historically will cost that company a lot of money. The other does not cost much at all and will get a whole lot more eyeballs on the product. You have to understand that.”

In his nine years with Saucony, True, training on his own in Hanover, New Hampshire, was part of only one ad campaign the company ran. The company preferred to use models for its ads and catalogs.

In February, True ran 27:14 for 10,000 meters, a personal best and faster than the Olympic standard. He wore Nike spikes and a plain yellow singlet. If all goes according to plan, he’ll race the U.S. Olympic Track and Field Trials in June and try to make his first team. His wife, professional triathlete Sarah True, is pregnant and due in July. And after that, he’ll run a fall marathon. True intended to debut at the marathon last fall, before the pandemic canceled all the races.

He’s moving ahead and training hard, despite the financial uncertainty. “I would have loved to have spent my entire career with Saucony,” he said. “I very much enjoyed working with them. I’ve been fortunate enough that I have had probably a lot more support than many other people in my position. That’s been nice.”

At this point, he is hoping another company will pick him up to take him through the next few years. “If a company just gave me a bonus structure that is fair for the result, I’d be happy with that,” he said. “It’s not like we’re looking for huge amounts of money. I’m very pragmatic and very realistic. I don’t think you should be paid for potential; I think you should be paid for results.”

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

New Salazar documentary questions reasons for his 2019 suspension

Nike’s Big Bet, the new documentary about former Nike Oregon Project head coach Alberto Salazar by Canadian filmmaker Paul Kemp, seeks to shed light on the practices that resulted in Salazar’s shocking ban from coaching in the middle of the 2019 IAAF World Championships. Many athletes, scientists and journalists appear in the film, including Canadian Running columnist Alex Hutchinson and writer Malcolm Gladwell, distance running’s most famous superfan.

Most of them defend Salazar as someone who used extreme technology like underwater treadmills, altitude houses and cryotherapy to get the best possible results from his athletes, and who may inadvertently have crossed the line occasionally, but who should not be regarded as a cheater. (Neither Salazar nor any Nike spokesperson participated in the film. Salazar’s case is currently under appeal at the Court of Arbitration for Sport.)

Salazar became synonymous with Nike’s reputation for an uncompromising commitment to winning. He won three consecutive New York City Marathons in the early 1980s, as well as the 1982 Boston Marathon, and set several American records on the track during his running career.

He famously pushed his body to extremes, even avoiding drinking water during marathons to avoid gaining any extra weight, and was administered last rites after collapsing at the finish line of the 1987 Falmouth Road Race.

Salazar was hired to head the Nike Oregon Project in 2001, the goal of the NOP being to reinstate American athletes as the best in the world after the influx of Kenyans and Ethiopians who dominated international distance running in the 1990s. It took a few years, but eventually Salazar became the most powerful coach in running, with an athlete list that included some of the world’s most successful runners: Mo Farah, Galen Rupp, Matt Centrowitz, Dathan Ritzenhein, Kara Goucher, Jordan Hasay, Cam Levins, Shannon Rowbury, Mary Cain, Donovan Brazier, Sifan Hassan and Konstanze Klosterhalfen.

Goucher left the NOP in 2011, disillusioned by what she saw as unethical practices involving unnecessary prescriptions and experimentation on athletes, and went to USADA in 2012. An investigation by the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency followed on the heels of a damning BBC Panorama special in 2015, and picked up steam in 2017.

When Salazar’s suspension was announced during the World Championships in 2019, he had been found guilty of multiple illegal doping practices, including injecting athletes with more than the legal limit of L-carnitine (a naturally-occurring amino acid believed to enhance performance) and trafficking in testosterone – but none of his athletes were implicated. (Salazar admitted to experimenting with testosterone cream to find out how much would trigger a positive test, but claimed he was trying to avoid sabotage by competitors.)

That Salazar pushed his athletes as hard in training as he had once pushed himself is not disputed; neither is the fact that no Salazar athlete has ever failed a drug test. Gladwell, in particular, insists that Salazar’s methods are not those of someone who is trying to take shortcuts to victory – that people who use performance-enhancing drugs are looking for ways to avoid extremes in training.

That assertion doesn’t necessarily hold water when you consider that drugs like EPO (which, it should be noted, Salazar was never suspected of using with his athletes) allow for faster recovery, which lets athletes train harder – or that the most famous cheater of all, Lance Armstrong, trained as hard as anyone. (Armstrong, too, avoided testing positive for many years, and also continued to enjoy Nike’s support after his fall from grace.)

Goucher, Ritzenhein, Levins and original NOP member Ben Andrews are the only former Salazar athletes who appear on camera, and Goucher’s is the only female voice in the entire film. It was her testimony, along with that of former Nike athlete and NOP coach Steve Magness, that led to the lengthy USADA investigation and ban.

Among other things, she claims she was pressured to take a thyroid medication she didn’t need, to help her lose weight. (The film reports that these medications were prescribed by team doctor Jeffrey Brown, but barely mentions that Brown, too, was implicated in the investigation and received the same four-year suspension as Salazar.) Ritzenhein initially declines to comment on the L-carnitine infusions, considering Salazar’s appeal is ongoing, but then states he thinks the sanctions are appropriate. Farah, as we know, vehemently denied ever having used it, then reversed himself.

It’s unfortunate that neither Cain, who had once been the U.S.’s most promising young athlete, nor Magness appear on camera. A few weeks after the suspension, Cain, who had left the NOP under mysterious circumstances in 2015, opened up about her experience with Salazar, whom she said had publicly shamed her for being too heavy, and dismissed her concerns when she told him she was depressed and harming herself. Cain’s experience is acknowledged in the film, and there’s some criticism of Salazar’s approach, but Gladwell chalks it up to a poor fit, rather than holding him accountable.

Cain’s story was part of an ongoing reckoning with the kind of borderline-abusive practices that were once common in elite sport, but that are now recognized as harmful, and from which athletes should be protected.

Gladwell asserts that coaches like Salazar have always pushed the boundaries of what’s considered acceptable or legal in the quest to be the best, and that the alternative is, essentially, to abandon elite sport. It’s an unfortunate conclusion, and one that will no doubt be challenged by many advocates of clean sport.

by Running Magazine

Login to leave a comment

These Track Photographers Are Giving Back to an Oregon Community Hit Badly by Wildfires

Just weeks after photographing a track meet in the area, they are selling photos to help with recovery.

The night prior to the Big Friendly track meet on July 17, Jake Willard was so excited he couldn’t sleep.

It had been months since the Eugene, Oregon-based photographer covered a race of any kind, due to the COVID-19 outbreak. And he couldn’t wait to shoot the elite-only competition at the McKenzie Community Track, situated among towering pine trees next to the McKenzie River in Vida, Oregon.

On July 17, Willard and fellow photographers Howard Lao and Tim Healy took pictures of some of the world’s best athletes. They watched world bronze medalist Shannon Rowbury run 8:40.26—the fastest performance in the world at that point—to win the women’s 3,000 meters. Olympic silver medalist Nijel Amos ran a world lead in the men’s 600 meters. And three professional training groups competed against each other in a rarely contested mixed-gender relay, among other standout performances.

The meet at the McKenzie Community Track was the second of five competitions in the Big Friendly Series, which were COVID-adjusted events organized by Portland Track this summer. With most tracks closed during the pandemic, Portland Track scrambled to coordinate competitions with different facility organizers. And the McKenzie Community Track board of directors was one of the groups that offered to help.

We thought [hosting the meet] was a really good gesture,” Duane Aanestad, vice president of McKenzie Community Track and Field, told Runner’s World. “We got the track here, there’s nothing going on, go for it.”

Big Friendly organizers required negative tests from everyone in attendance, didn’t allow spectators inside the facility, and asked the competitors—some racing for the first time this year—to socially distance. While documenting these unprecedented moments, Willard felt at peace for the first time in months.

“It felt like a good day, and the athletes had fun with it,” Willard told Runner’s World. “There was a noticeable camaraderie for everyone in attendance, a lot of smiles, a lot of laughing, a lot of elbow bumps instead of high-fives. It was cool to see everyone there enjoy that for a moment, life was normal. Track was the center of our universe.”

But weeks after the Big Friendly meets, the same community that welcomed local track athletes needed major assistance. In early September, the region was nearly decimated by the Holiday Farm Fire, a 173,000-acre blaze that burned more than 430 homes and infrastructure in the McKenzie River Valley. As reported by The Oregonian, the photographers and Portland Track organizers responded to the crisis by giving back to the community that opened its doors to them.

“[McKenzie board of directors] were such a great, welcoming community when we were trying to figure this out,” Michael Bergmann, president of Portland Track, told Runner’s World. “We were literally flying by the seat of our pants, and so we just wanted to return that favor as part of the track and field community in bringing that care for a community that’s in pain.”

As Lao monitored the fire from his home in Portland, he emailed Willard and Healy on September 12, suggesting they sell prints of their photographs from the competition and donate the proceeds. In coordination with Portland Track, the photographers each donated three photos for an Etsy shop, where funds from every photo sold goes to the McKenzie Community Recovery Fund. As of November 10, the Portland Track Store has made 12 sales.

“It was a really big team effort from everybody,” Lao told Runner’s World. “We’re just trying to get some relief down to the people there. The track was used for a track meet in the summer and then it was used for a safe meeting place during the fire. It’s more than just a track.”

Retired track coach Jeff Sherman is one of the local contacts that helped coordinate the Big Friendly. When the fire hit the McKenzie community, Sherman and his family were able to evacuate to eastern Oregon. But many were unable to leave because debris blown over by the blaze blocked the roadways. Residents took refuge in the track infield, where a fire crew worked tirelessly to protect them from the flames.

“[The fire] burned right up to the fencing on the track and a metal building with hurdles stored inside, it scorched the back of that,” Sherman said. “From what I understand, people were there for about four or five hours.” He said rescue crews ultimately led residents to safety with road-clearing equipment around 5 a.m. local time.

Weeks later, the McKenzie community is working to rebuild after the fire’s mass destruction. But the gesture from Portland Track and the photographers is providing a bright spot in a time of need.

“[Portland Track] were reaching out from the get-go to ask if we needed help,” Aanestad said. “It seemed like we were part of a family, and you take care of family.”

by Runner’s World

Login to leave a comment

After dealing with a plantar fasciitis problem in Europe, Donavan Brazier ends his season

Donavan Brazier’s 2020 outdoor season is over.

The reigning outdoor champion and U.S. record-holder in the 800 meters has been dealing with nagging plantar fasciitis problem in his right foot according to Pete Julian, Brazier’s coach.

Not that anybody could tell from his performances. Brazier won his 10th consecutive race -- a streak that dates to 2019 -- Sunday in the Stockholm Diamond League meet, taking the 800 in 1 minute 43.76 seconds with a late charge on the home straight.

And, for Brazier, that was that.

In a text message, Julian said Brazier’s has been dealing with “one of those types of injuries that most runners can relate to. Not bad enough to stop but not good enough to bring fuzzy happiness. It’s all always about finding the right combination of what you can and cannot do.

“As long as he was getting through the training and making a little bit of progress from week to week, and with the support of his doctor, I welcomed the adversity as a teaching tool. He did a great job keeping his head straight and focusing on winning stead of whining. By Stockholm, his foot was feeling better and you could tell in the way he raced.”

Just the same, Brazier and Julian decided enough was enough.

“He was fishing on the banks of Stockholm the next day,” Julian said.

Julian said the runners in his training group will go different directions soon. Craig Engels, Jessica Hull, Raevyn Rogers and Shannon Rowbury are entered in a meet in Goteborg, Sweden on Saturday. After that, Julian and some of his athletes will head home.

Engels is penciled into the 1,500 at the Diamond League in Brussels on Sept. 4. Hull and Rowbury are scheduled for the 1,500 in Berlin on Sept. 13.

“Shann and Jessica want to stay in Europe and keep racing any willing participants,” Julian said.

by Ken Goe

Login to leave a comment

Shannon Rowbury just might make her fourth US Olympic Team post-pregnancy

Shannon Rowbury proved she can run elite times post-pregnancy. Next year, she hopes to be the latest example that an Olympic career doesn’t end with motherhood.

“Having a child isn’t a death sentence,” she told fellow Olympic runner and mom Alysia Montaño in a recent On Her Turf interview. “You can come back even better.”

Rowbury, a 35-year-old, three-time Olympian, raced this month on the Diamond League circuit for the first time in three years and since having daughter Sienna in June 2018.

It went pretty well. She clocked her second-fastest 5000m ever, a 14:45.11 to place fifth in Monaco.

Only four other Americans have ever gone faster. One is retired (Shalane Flanagan). It’s very possible that two of the others could focus on other distances next summer (Shelby Houlihan and Molly Huddle).

Rowbury is right in the mix to make a fourth straight Olympics, given three U.S. women qualify per event. She can become the oldest U.S. woman to race on an Olympic track since Gail Devers in 2004, and one of the few moms to do so.

Rowbury is the former American record holder at 1500m and 5000m with a pair of fourth-place finishes from racing the former at the last three Olympics.

In 2018, she returned to training eight weeks after having Sienna. Ramping up too quickly led to a stress fracture in early 2019. She felt fatigued from sleep deprivation and breastfeeding and struggled with her identity.

Will I ever be the same? How much do I have left? Who am I without sport?

“I love my daughter,” she said last year, “but I loved my life before as well.”

She kept running. Rowbury placed sixth in the 5000m at the 2019 USATF Outdoor Championships, racing on a lack of training due to the injury. She missed an Olympic or world championships team for the first time since 2007, when she graduated from Duke.

Then in November, she won the U.S. 5km title on the roads in New York City. Rowbury raced for the first time this year in July and is still in Europe, torn while spending three weeks away from Sienna and husband Pablo Solares, a former middle-distance runner from Mexico.

“I felt very strongly that I would never prioritize my career over my family and over my daughter,” she said. “My performance right now is testament to the fact that you can have a healthy, natural weaning process, and you can still compete at a very high level.”

Rowbury partly dismissed motherhood earlier in her career because she was afraid of potential consequences. In more recent years, runners including Rowbury, Montaño and Allyson Felix fought for maternity protection in the sport, such as with health insurance through USA Track and Field and in sponsor contracts.

“I don’t think that any woman should be told she needs to do something in order to compete as an athlete or to pursue her dreams,” Rowbury said.

by Yahoo Sports OlympicTalk

Login to leave a comment

Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games

Fifty-six years after having organized the Olympic Games, the Japanese capital will be hosting a Summer edition for the second time, originally scheduled from July 24 to August 9, 2020, the games were postponed due to coronavirus outbreak, the postponed Tokyo Olympics will be held from July 23 to August 8 in 2021, according to the International Olympic Committee decision. ...

more...Long hours, short nights and ulcers: Portland Track defies the coronavirus to stage elite meets

If Portland Track’s Jeff Merrill feels a little ragged, well, no wonder.

The legwork it takes to stage elite track meets during the coronavirus pandemic would be a strain on anybody.

“It’s an around-the-clock type of thing,” Merrill says. “The days all kind of blur together.”

Portland Track has put on two popup meets, the Big Friendly 1 on July 3 at Portland’s Jesuit High School and the Big Friendly 2 (the Bigger Friendly) on July 17 at McKenzie Track, 40 miles outside of Eugene.

Big Friendly 3 is being planned for Friday at an undisclosed location somewhere in the Portland area. Organizers are staying mum about the location to discourage spectators and prevent potential spread of the virus.

The effort it’s taken to get to this point would exhaust a marathoner. Portland Track has consulted with Oregon’s three, Nike-sponsored elite distance groups — the Bowerman Track Club, Oregon Track Club Elite and coach Pete Julian’s unnamed group.

The Portland Thorns of the National Women’s Soccer League have advised. The office of Oregon Gov. Kate Brown has signed off. So have Multnomah and Lane counties, and, presumably, the county in which the next one will take place if it’s not Multnomah. So has USA Track & Field.

Portland Track organizers have arranged with Providence-Oregon for participants to be tested twice in a 48-hour period shortly before race day. They have had to find available tracks suitable for Olympic-level athletes that meet USATF’s sanctioning criteria.

In the case of McKenzie Track, that meant building an inside rail the day before the meet, even while on the phone to Lane County Health and Human Services.

“We weren’t sure the meet was going to happen because a new mask order was going into effect and we wanted to find out for sure that we were OK to hold it,” Merrill says.

They were — once they had passed the hat to participants to pay for the rail. Portland Track is a shoestring operation with an all-volunteer board and next-to-no budget. Merrill, who is a Portland Track board member and works fulltime for Nike, hasn’t slept much this month.

None of this is easy. All of it is time consuming. Start with finding a track.

“It’s pretty hard,” says Portland Track president Michael Bergmann. “I’ve learned about all the tracks in the state, from Lane Community College, to George Fox, to Linfield, to Mt. Hood Community College. All of those guys have rails. But the schools are closed. The campuses are closed. Most of those places don’t want to take the risk of having any sort of event, which I totally understand and respect.”

McKenzie Community Track & Field didn’t have those concerns, which made the track available on July 17 — providing Portland Track brought the rail.

But that track’s tight turns make it less suitable for running fast and setting records, which is what athletes such as Donavan Brazier, Craig Engels, Konstanze Klosterhalfen, Raevyn Rogers and Shannon Rowbury of Team Julian, Nijel Amos and Chanelle Price of OTC Elite, and Josh Kerr of the Brooks Beasts want to do.

“A good call out is, when you’re looking at an aerial view on Google Maps, you want a track with a soccer field in the middle because those are wider,” Merrill says. “If they just have a football field in the middle, they’re a little narrow.”

The Thorns became involved because some players are fans of Tracklandia, a talk show Portland Track streams and Merrill co-hosts with two-time Olympian Andrew Wheating.

Thorns defender Emily Menges, who ran track at Georgetown, has been known to join the pre-pandemic post-show gatherings at an adjacent restaurant. When Merrill mentioned Portland Track was trying to set up a coronavirus testing protocol, Menges put the organizers in touch with the Thorns training staff. That led Portland Track to Providence for the testing.

“Their system is awesome,” Bergmann says.

On race day, Portland Track is serious about keeping out spectators and holding down the number of people around the track.

At McKenzie Track, “we had folks from their board at the front of the road access with a checklist,” Bergmann says. “Nobody got past who wasn’t on the list. When people come into the facility, we do a temperature check and give them a wristband to show they’ve been checked.”

Athletes are asked to wear masks when not competing. Portland Track board members do everything from labeling and handing out race bibs to counting laps to handling the public address announcing.

They had hoped to livestream the McKenzie meet, but rural Lane County couldn’t provide the necessary bandwidth. That shouldn’t be a problem Friday.

J.J. Vazquez, a Portland State professor who runs the production company Locomotion Pictures, is set to be in charge of streaming the action live on Portland Track’s free

There should be plenty to watch. Team Julian, OTC Elite, the Brooks Beasts of Seattle and Little Wing of Bend will compete. Seattle-based post-collegians mentored by University of Washington coaches Andy and Maurica Powell also figure to be there.

Bergmann has hinted there could be surprises — either entries or record attempts — but declines to be more specific.

The Bowerman Track Club has opted out, choosing instead to hold intrasquad time trials.

Bergmann says BTC coach Jerry Schumacher “knows what we’re doing. But they’ve been pretty successful doing it their way. He has his plan. I’m not going to beg him.”

The people at Portland Track have enough on their plate as it is. They aren’t getting rich.

On their own time, they are providing the region’s Olympic-level athletes a chance to do what they train to do.

“We’re having a blast,” Merrill says. “Although, I might have an ulcer.”

by Oregon Live

Login to leave a comment

First american trio Cory McGee, Dani Jones and Emma Coburn, to run sub 4:24 in the same race at Indiana Mile

Cory McGee, Dani Jones and Emma Coburn took advantage of racing at sea level for the first time outdoors this year and achieved history by becoming the first American trio to all run under 4 minutes, 24 seconds in the same race Saturday at the Team Boss Indiana Mile at Indiana Wesleyan University in Marion.

McGee, a New Balance professional, surged with 250 meters remaining and never relinquished control, clocking a lifetime-best 4:21.81 to elevate to the No. 8 all-time American outdoor performer.

Jones (4:23.33), a first-year professional, and Coburn (4:23.65), also a New Balance athlete, achieved significant personal bests to ascend to the Nos. 10 and 11 outdoor performers in U.S. history.

Tripp Hurt won the men’s mile in a world-leading 3:56.18, just off his 3:56.02 lifetime best, with Nick Harris running a personal-best 3:57.11 and Mason Ferlic achieving a sub-4 clocking for the first time in his career to place third in 3:58.87.

McGee also achieved a 1,500-meter personal best en route of 4:03.82 to run the fastest female mile time ever on Indiana soil. Jones also ran 4:05 to lower her 1,500 personal best as well.

Canadian talent Nicole Sifuentes clocked 4:30.50 in the mile on the oversized indoor track at Notre Dame in 2016, to move just ahead of Suzy Favor Hamilton’s 4:30.64 on a standard 200-meter indoor banked track from 1989 in Indianapolis.

But thanks to the aggressive pacing of South African Dom Scott Efurd, an adidas professional who brought the group through 440 yards at 1:03.2 and the midway point in 2:10.08, all of her teammates benefited to post the top three outdoor marks in the world this year.

Coburn, who ran 4:32.72 at 4,583 feet elevation June 27 to win the Team Boss Colorado Mile at Colorado Mesa University in Grand Junction, held the advantage with one lap remaining Saturday at 3:16.30, followed closely by McGee (3:16.56) and Jones (3:16.85).

On four previous occasions, a pair of Americans had both run under 4:24 in the same mile race, but never a trio of athletes. The most recent occurrence came at the 2018 Muller Anniversary Games, the annual London Diamond League Meeting, with Jenny Simpson placing fourth in 4:17.30 and Kate Grace taking eighth in 4:20.70 behind winner and Dutch star Sifan Hassan in 4:14.71.

Grace and Shannon Rowbury were the only tandem to achieve the feat indoors at the 2017 Wanamaker Mile at the NYRR Millrose Games, finishing second and third behind World 1,500-meter gold medalist Hassan.

The other two races where two Americans have run under 4:24 outdoors occurred at the 2015 Diamond League final in Belgium – with Rowbury and Simpson taking third and fourth behind Kenya’s Faith Kipyegon and Hassan – along with the 1998 Goodwill Games in New York, where Regina Jacobs and Favor Hamilton took second and third behind Ireland’s Sonia O’Sullivan.

The last country to achieve the feat of three athletes running sub-4:24 in the same mile race was Ethiopia, which had Gudaf Tsegay (4:18.31), Axumawit Embaye (4:18.58) and Alemaz Samuel (4:23.35) at last year’s Diamond League Meeting in Monaco.

Russia at the 1993 Golden Gala in Rome and Great Britain at the 2017 Muller Anniversary Games in London are the only other countries to accomplish the sub-4:24 trifecta in the same race.

Australian talent Morgan McDonald paced the men’s race through 440 yards in 58.9 and the midway point in 1:58.87. He brought his teammates through 1,000 meters at 2:28, before moving out wide to give way to Hurt just before the bell lap at 2:57.25.

Harris surged with 300 meters remaining to take a brief lead, but Hurt responded to regain the advantage with 200 left, as the athletes achieved the top two outdoor times in the world this year, with Ferlic elevating to the No. 4 global performer.

The fastest men’s mile time on Indiana soil remains a 3:54.48 from Irish star Marcus O’Sullivan in Indianapolis in 1993.

by Mile Split

Login to leave a comment

Four Olympians and Top International Competitors will Seek World and American Records at Applied Material Silicon Valley Turkey Trot

The Applied Materials Silicon Valley Turkey Trot produced by the Silicon Valley Leadership Group Foundation announced full fields today for both their women’s Elite 5k presented by Silicon Valley Bank and their men’s Elite 5k presented by Juniper Networks.

While the Silicon Valley Turkey Trot is often known as one of the world’s largest turkey trots boasting over 25,000 runners and nearly $1,000,000 in annual fundraising, this year the elites are leading the conversation. Athletes will contend for more than $30,000 in prize money and potential bonuses.

On the women’s side Shannon Rowbury returns as the most accomplished 5k runner in the field boasting a best of 14:38 on the track. Rowbury is coming fresh off a victory at the USATF 5k Road Championships in New York City and has the American road record in her sites.

“I’m certainly in better shape than last year” said Rowbury, “and you know, on the right day anything can happen.” Shannon will be challenged by fellow U.S. Olympians Kim Conley and Emily Infeld, plus 10k/marathon specialist Stephanie Rothstein Bruce. Full fields listed below.

The men’s field is highlighted by Kenyans David Bett and Lawi Lalang. Bett has made no secret that the IAAF World 5k Road Record is his only goal. That record was recently set at 13:22 in Paris by Robert Keter. Lalang has a best of 13:00 on the track and has placed at Silicon Valley in the past.

Rounding out the elite field for the men includes Ethiopian Josef Tessema (13:22), Canadian Luc Bruchet (13:24 best), and American Jeff Thies (3rd at 2019 USATF 5k Road Champs).

Race Founder and Executive Director, Carl Guardino shared his excitement for the event. “This might be the most accomplished Elite field in our 15-year history and certainly has the most depth. While we expect over 25,000 runners at the largest timed Turkey Trot in the U.S., it brings me joy to also welcome some of the world’s fastest athletes to Silicon Valley on Thanksgiving Day”

Login to leave a comment

Applied Materials Turkey Trot

Start Thanksgiving Day off on the right foot at the Applied Materials “Silicon Valley Turkey Trot”. Before the big games, the big meal, the parades and the pies, why not get in a little exercise with a few thousand neighbors? It’s an event the whole family will enjoy! Many have made the “run” or “walk” a Thanksgiving Day tradition. You’ll...

more...Defending champion Emily Sisson and Shannon Rowbury to highlight women’s field at USATF 5 km Championships

The 2019 Abbott Dash to the Finish Line 5K and USA Track & Field (USATF) 5 km Championships on Saturday, November 2, will feature seven Olympians and two past champions the day prior to the TCS New York City Marathon and will be broadcast live on USATF.TV as part of the 2019 USATF Running Circuit. Abbott will return as the title partner of the event which features a $60,000 prize purse – the largest of any 5K race in the world.

Emily Sisson is looking to defend her USATF 5 km title after storming to victory last year in a solo run to the finish in 15:38. The two-time United Airlines NYC Half runner-up clocked the fastest-ever debut by an American on a record-eligible course at this year’s Virgin Money London Marathon, finishing sixth place in 2:23:08.

She will line up in Central Park against three-time Olympian and World Championship medalist Shannon Rowbury and Olympian and World Championship medalist Emily Infeld.

“I loved my experience at the Abbott Dash and USATF 5 km Championships last year,” Sisson said. “There’s no place like New York City on marathon weekend, and I’m excited to help kick everything off by defending my 5K title on the streets of New York.”

In the men’s field, Olympian Shadrack Kipchirchir will attempt to reclaim his title after taking second in a photo-finish last year. At the 2017 edition of the event, he won his third national title in 13:57.

He will be challenged by Rio 2016 Olympic gold medalist and seven-time national champion Matthew Centrowitz, who has had previous success in New York, winning the NYRR Millrose Games Wanamaker mile three times and the 5th Avenue Mile once. Reid Buchanan, a 2019 Pan American Games silver medalist, and Eric Jenkins, the 2017 NYRR Wanamaker Mile and 5th Avenue Mile champion, will also line up.

Following in the footsteps of the professional athletes will be more than 10,000 runners participating in the Abbott Dash to the Finish Line 5K, including top local athletes and runners visiting from around the world. The mass race will offer a $13,000 NYRR member prize purse. John Raneri of New Fairfield, CT and Grace Kahura of High Falls, NY won last year’s Abbott Dash to the Finish Line 5K.

Abbott, the title sponsor of the Abbott World Marathon Majors, will be the sponsor of the Abbott Dash to the Finish Line 5K for the fourth consecutive year. Abbott, a global healthcare company, helps people live fully with life-changing technology and celebrates what’s possible with good health.

The Abbott Dash to the Finish Line 5K annually provides TCS New York City Marathon supporters, friends and families the opportunity to join in on the thrill of marathon race week. The course begins on Manhattan’s east side by the United Nations, then takes runners along 42nd Street past historic Grand Central Terminal and up the world-famous Avenue of the Americas past Radio City Music Hall. It then passes through the rolling hills of Central Park before finishing at the iconic TCS New York City Marathon finish line.

Login to leave a comment

Dash to the Finish Line

Be a part of the world-famous TCS New York City Marathon excitement, run through the streets of Manhattan, and finish at the famed Marathon finish line in Central Park—without running 26.2 miles! On TCS New York City Marathon Saturday, our NYRR Dash to the Finish Line 5K (3.1 miles) will take place for all runners who want to join in...

more...Shalane Flanagan has announced her retiring from professional running

With happy tears I announce today that I am retiring from professional running. From 2004 to 2019 I’ve given everything that’s within me to this sport and wow it’s been an incredible ride! I’ve broken bones, torn tendons, and lost too many toenails to count. I've experienced otherworldly highs and abysmal lows. I've loved (and learned from) it all.

Over the last 15 years I found out what I was capable of, and it was more than I ever dreamed possible. Now that all is said and done, I am most proud of the consistently high level of running I produced year after year. No matter what I accomplished the year before, it never got any easier. Each season, each race was hard, so hard. But this I know to be true: hard things are wonderful, beautiful, and give meaning to life. I’ve loved having an intense sense of purpose. For 15 years I've woken up every day knowing I was exactly where I needed to be.

The feeling of pressing the threshold of my mental and physical limits has been bliss. I've gone to bed with a giant tired smile on my face and woken up with the same smile. My obsession to put one foot in front of the other, as quickly as I can, has given me so much joy.

However, I have felt my North Star shifting, my passion and purpose is no longer about MY running; it's more and more about those around me. All I’ve ever known, in my approach to anything, is going ALL IN.

So I’m carrying this to coaching. I want to be consumed with serving others the way I have been consumed with being the best athlete I can be.

I am privileged to announce I am now a professional coach of the Nike Bowerman Track Club. This amazing opportunity in front of me, to give back to the sport, that gave me so much, is not lost on me. I’ve pinched myself numerous times to make sure this is real. I am well aware that retirement for professional athletes can be an extremely hard transition. I am lucky, as I know already, that coaching will bring me as much joy and heartache that my own running career gave me.

I believe we are meant to inspire one another, we are meant to learn from one another. Sharing everything I’ve learned about and from running is what I’m meant to do now.I would like to thank: The 5 coaches who guided me throughout my career, Michael Whittlesey and Dennis Craddock (2004-2005), John Cook (2006-2008), Jerry Schumacher (2009-2019), and Pascal Dobert (2009-2019). Each man was instrumental in developing me into the best version of myself.

Jerry, Pascal and I will continue to work together in this next chapter and I couldn’t be more grateful.

Jerry has been my life coach, running coach and now will mentor me towards my next goal of becoming a world-class coach myself. I’m thankful for his unending belief in me.

My family and husband who have traveled the world supporting my running and understanding the sacrifices I needed to make. Their unconditional love is what fueled my training.My longtime friend, Elyse Kopecky who taught me to love cooking and indulge in nourishing food. Run Fast. Eat Slow. has been a gift to my running and to the thousands of athletes.

My teammates, and all the women I've trained with, for pushing me daily, and the endless smiles and miles. They include: Erin Donahue, Shannon Rowbury, Kara Goucher, Lisa Uhl, Emily Infeld, Amy Cragg, Colleen Quigley, Courtney Frerichs, Shelby Houlihan, Betsy Saina, Marielle Hall, Gwen Jorgensen, Kate Grace.

My sponsor Nike for believing in me since 2004 and for continuing to support my new dream as a professional coach. I hope I made myself a better person by running. I hope I made those around me better. I hope I made my competition better. I hope I left the sport better because I was a part of it.

My personal motto through out my career has been to make decisions that leave me with “no regrets”.....but to be honest, I have one. I regret I can’t do it all over again.

by Shalane Flanagan

Login to leave a comment

TCS New York City Marathon

The first New York City Marathon, organized in 1970 by Fred Lebow and Vince Chiappetta, was held entirely in Central Park. Of 127 entrants, only 55 men finished; the sole female entrant dropped out due to illness. Winners were given inexpensive wristwatches and recycled baseball and bowling trophies. The entry fee was $1 and the total event budget...

more...Shelby Houlihan runs a big PR to break the American 5000m record, clocking 13:34

Login to leave a comment