Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Articles tagged #Dipsea

Today's Running News

The Last Push Before Summer: How Runners Are Peaking This Spring

As the calendar turns toward May, runners across the globe are entering a crucial phase in their annual training cycles: the final opportunity to race hard and fast before summer heat shifts the strategy.

While many spring races are just wrapping up—or happening this weekend—runners are still chasing personal bests and season goals. The London Marathon, Madrid Marathon, and Big Sur International Marathon are all set for this Sunday, capping off one of the most exciting stretches of the global racing calendar.

But the season isn’t quite over yet. The Eugene Marathon, Vancouver Marathon, Pittsburgh Marathon, and other early May events are giving runners one more shot to test their fitness—and many are taking full advantage.

A Critical Window for Speed and Strategy

“This is one of the best times of year to be fit,” says Coach Dennis from KATA Portugal. “Runners who stayed healthy through the winter and peaked for April races are now sharper than ever. If you can handle one more race effort, this is the time to go for it.”

Late April and early May offer ideal racing weather in much of the Northern Hemisphere. Cool mornings and calm conditions are perfect for PRs, BQ attempts, or one last tune-up before switching into base-building mode.

The Spring Surge Continues

The Eugene Marathon (April 27) and BMO Vancouver Marathon (May 4) are both known for fast, scenic courses and well-organized race weekends. They attract everyone from local club runners to elites trying to salvage a qualifying time or simply end the spring on a high note.

“My goal race is Berlin this fall, but Eugene gives me a mid-year checkpoint,” says California-based runner Mallory James. “If I’m not racing now, I’m falling behind.”

Time to Recover—or to Launch

Some runners will use May for recovery after a hard season. Others—especially those gearing up for summer trail and mountain races—are just now hitting their peak mileage. Events like the Dipsea, Mt. Washington Road Race, and Western States 100 are fast approaching.

Coach’s Tip: Plan Your Summer Wisely

According to KATA coach and 2:07 marathoner Jimmy Muindi, spring is where momentum is built—but summer is where runners evolve. “If you raced well this spring, great. Now shift the focus to long-term strength. Summer is for building, not burning out.”

Whether you’re racing this weekend or logging miles toward your fall marathon, this is your moment to finish strong—and set the tone for everything that comes next. As the calendar turns toward May, runners across the globe are entering a crucial phase in their annual training cycles: the final opportunity to race hard and fast before summer heat shifts the strategy.

by Boris Baron

Login to leave a comment

TWENTY-ONE YEARS AGO, HE WAS INCARCERATED FOR LIFE. LAST YEAR, HE RAN THE NYC MARATHON A RADICALLY CHANGED MAN.

RAHSAAN ROUNDED THOMAS A CORNER. Gravel underfoot gave way to pavement, then dirt. Another left turn, and then another. In the distance, beyond the 30-foot wall and barbed wire separating him from the world outside, he could see the 2,500-foot peak of Mount Tamalpais. He completed the 400-meter loop another 11 times for an easy three miles.

Rahsaan wasn’t the only runner circling the Yard that evening in the fall of 2017. Some 30 people had joined San Quentin State Prison’s 1,000 Mile Club by the time Rahsaan arrived at the prison four years prior, and the group had only grown since. Starting in January each year, the club held weekly workouts and monthly races in the Yard, culminating with the San Quentin Marathon—105 laps—in November. The 2017 running would be Rahsaan’s first go at the 26.2 distance.

For Rahsaan and the other San Quentin runners, Mount Tam, as it’s known, had become a beacon of hope. It’s the site of the legendary Dipsea, a 7.4-mile technical trail from Mill Valley to Stinson Beach. After the 1,000 Mile Club was founded in 2005, it became tradition for club members who got released to run that trail; their stories soon became lore among the runners still inside. “I’ve been hearing about the Dipsea for the longest,” Rahsaan says.

Given his sentence, he never expected to run it. Rahsaan was serving 55 years to life for second-degree murder. Life outside, let alone running over Mount Tam all the way to the Pacific, felt like a million miles away. But Rahsaan loved to run—it gave him a sense of freedom within the prison walls, and more than that, it connected him to the community of the 1,000 Mile Club. So if the volunteer coaches and other runners wanted to talk about the Dipsea, he was happy to listen.

We’ll get to the details of Rahsaan’s crime later, but it’s useful to lead with some enduring truths: People can grow in even the harshest environments, and running, whether around a lake or a prison yard, has the power to change lives. In fact, Rahsaan made a lot of changes after he went to prison: He became a mentor to at-risk youth, began facing the reality of his violence, and discovered the power of education and his own pen. Along the way, Rahsaan also prayed for clemency. The odds were never in his favor.

To be clear, this is not a story about a wrongful conviction. Rahsaan took the life of another human being, and he’s spent more than two decades reckoning with that fact. He doesn’t expect forgiveness. Rather, it’s a story about a man who you could argue was set up to fail, and for more than 30 years that’s exactly what he did. But it’s also a story of navigating the delta between memory and fact and finding peace in the idea that sometimes the most formative things in our lives may not be exactly as they seem. And mostly, it’s a story of transformation—of learning to do good in a world that too often encourages the opposite.

RAHSAAN “NEW YORK” THOMAS GREW UP IN BROWNSVILLE, A ONE-SQUARE-MILE SECTION OF EASTERN Brooklyn wedged between Crown Heights and East New York. As a kid he’d spend hours on his Commodore 64 computer trying to code his own games. He loved riding his skateboard down the slope of his building’s courtyard. On weekends, he and his friends liked to play roller hockey there, using tree branches for sticks and a crushed soda can for a puck.

Once a working-class Jewish enclave, Brownsville started to change in the 1960s, when many white families relocated to the suburbs, Black families moved in, and city agencies began denying residents basic services like trash pickup and streetlight repairs. John Lindsay, New York’s mayor at the time, once referred to the area as “Bombsville” on account of all the burned-out buildings and rubble-filled empty lots. By 1971, the year after Rahsaan was born, four out of five families in Brownsville were on government assistance. More than 50 years later, Brownsville still has a poverty rate close to 30 percent. The neighborhood’s credo, “Never ran, never will,” is typically interpreted as a vow of resilience in the face of adversity. For some, like Rahsaan, it has always meant something else: Don’t back down.

The first time Rahsaan didn’t run, he was 5 or 6 years old. He had just moved into Atlantic Towers, a pair of 24-story buildings beset with rotting walls and exposed sewer pipes that housed more than 700 families. Three older kids welcomed him with their fists. Even if Rahsaan had tried to run, he wouldn’t have gotten far. At that age, Rahsaan was skinny, slow, and uncoordinated. He got picked on a lot. Worse, he was light-skinned and frequently taunted as “white boy.” The insult didn’t even make sense to Rahsaan, whose mother is Black and whose father was Puerto Rican. “I feel Black,” he says. “I don’t feel [like] anything else. I feel like myself.”

Rahsaan hated being called white. It was the mid-1970s; Roots had just aired on ABC, and Rahsaan associated being white with putting people in chains. Five-Percent Nation, a Black nationalist movement founded in Harlem, had risen to prominence and ascribed godlike status to Black men. Plus, all the best athletes were Black: Muhammad Ali. Reggie Jackson. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. In Rahsaan’s world, somebody white was considered physically inferior.

Raised by his mother, Jacqueline, Rahsaan never really knew his father, Carlos, who spent much of Rahsaan’s childhood in prison. In 1974, Jacqueline had another son, Aikeem, with a different man, and raised her two boys as a single mom. Carlos also had another son, Carl, whom Rahsaan met only once, when Carl was a baby. Still, Rahsaan believed “the myth,” as he puts it now, that one day Carlos would return and relieve him, his mom, and Aikeem of the life they were living. Jacqueline had a bachelor’s degree in sociology and worked three jobs to keep her sons clothed and fed. She nurtured Rahsaan’s interest in computers and sent him to a parochial school that had a gifted program. Rahsaan describes his family as “upper-class poor.” They had more than a lot of families, but never enough to get out of Brownsville, away from the drugs and the violence.

Some traumas are small but are compounded by frequency and volume; others are isolated occurrences but so significant that they define a person for a lifetime. Rahsaan remembers his grandmother telling him that his father had been found dead in an alley, throat slashed, wallet missing. Rahsaan was 12 at the time, and he understood it to mean his father had been murdered for whatever cash he had on him—maybe $200, not even. Now he would never come home.

Rahsaan felt like something he didn’t even have had been taken from him. “It just made me different, like, angry,” he says. By the time he got to high school, Rahsaan resolved to never let anyone take anything from him or his family again. “I started feeling like, next time somebody tryin’ to rob me, I’m gonna stab him,” he says. He started carrying a knife, a razor, rug cutters—“all kinds of sharp stuff.” Rahsaan never instigated a fight, but he refused to back down when threatened or attacked. It was a matter of survival.

The first time Rahsaan picked up a gun, it was to avenge his brother. Aikeem, who was 14 at the time, had been shot in the leg by a guy in the neighborhood who was trying to rob him and Rahsaan. A few months later, Rahsaan saw the shooter on the street, ran to the apartment of a drug dealer he knew, and demanded a gun. Rahsaan, then 18, went back outside and fired three shots at the guy. Rahsaan was arrested and sent to Rikers Island, then released after three days: The guy he’d shot was wanted for several crimes and refused to testify against Rahsaan.

By day, Rahsaan tried to lead a straight life. He graduated from high school in 1988 and got a job taking reservations for Pan Am Airways. He lost the job after Flight 103 exploded in a terrorist bombing over Scotland that December, and the company downsized. Rahsaan got a new job in the mailroom at Debevoise & Plimpton, a white-shoe law firm in midtown Manhattan. He could type 70 words a minute and hoped to become a paralegal one day.

Rahsaan carried a gun to work because he’d been conditioned to expect the worst when he returned to Brownsville at night. “If you constantly being traumatized, you constantly feeling unsafe, it’s really hard to be in a good mind space and be a good person,” he says. “I mean, you have to be extraordinary.”

After high school, some of Rahsaan’s friends went to Old Westbury, a state university on Long Island with a rolling green campus. He would sometimes visit them, and at a Halloween party one night, he got into a scrape with some other guys and fired his gun. Rahsaan spent the next year awaiting trial in county jail, the following year at Cayuga State Prison in upstate New York, and another 22 months after that on work release, living in a halfway house in Queens. He got a job working the merch table for the Blue Man Group at Astor Place Theater, but the pay wasn’t enough to support the two kids he’d had not long after getting out of Cayuga.

He started selling a little crack around 1994, when he was 24. By 27 he was dealing full-time. He didn’t want to be a drug dealer, though. “I just felt desperate,” he says. Rahsaan had learned to cut hair in Cayuga, and he hoped to save enough money to open a barbershop.

He never got that opportunity. By the summer of 1999, things in New York had gotten too hot for Rahsaan and he fled to California. For the first time in his 28 years, Rahsaan Thomas was on the run.

EVERY RUNNER HAS AN ORIGIN STORY. SOME START IN SCHOOL, OTHERS TAKE UP RUNNING TO IMPROVE their health or beat addiction. Many stories share common themes, if not exact details. And some, like Rahsaan’s, are absolutely singular.

Rahsaan drove west with ambitions to break into the music business. He wanted to be a manager, maybe start his own label. His new girlfriend would join him a week later in La Jolla, where they’d found an apartment, so Rahsaan went first to Big Bear, a small town deep in the San Bernardino Mountains 100 miles east of Los Angeles. It’s where Ryan Hall grew up, and where he discovered running at age 13 by circling Big Bear Lake—15 miles—one afternoon on a whim. Hall has recounted that story so many times that it’s likely even better known than the American records he would go on to set in the half and full marathons.

Rahsaan didn’t know anything about Ryan Hall, who at the time was just about to start his junior year at Big Bear High School and begin a two-year reign as the California state cross-country champion. He didn’t even know there was a lake in Big Bear. Rahsaan went to Big Bear to box with a friend, Shannon Briggs, a two-time World Boxing Organization heavyweight champion.

Briggs and Rahsaan had grown up together in Atlantic Towers. As kids they liked to ride bikes in the courtyard, and later they went to the same high school in Fort Greene. But Briggs’s mom had become addicted to drugs by his sophomore year, and they were evicted from the Towers. Briggs and Rahsaan lost touch. Briggs began spending time at a boxing gym in East New York; often he’d sleep there. He had talent in the ring. People thought he might even be the next Mike Tyson, another native of Brownsville who was himself a world heavyweight champ from 1986 to 1989.

Briggs went pro in 1991, and by the end of that decade he was earning seven figures fighting guys like George Foreman and Lennox Lewis. Rahsaan was at those fights. The two had reconnected in 1996, when Rahsaan was trying to rebuild his life after prison and Briggs’s boxing career was on the rise. In August 1999, Briggs was gearing up to fight Francois Botha, a South African known as the White Buffalo, and had decamped to Big Bear to train. “He was like, ‘Yo, come live with me, bro,’” Rahsaan recalls.

Briggs was running three miles a day to increase his stamina. His route was a simple out-and-back on a wooded trail, and on one of Rahsaan’s first days there, he decided to join him. Rahsaan hadn’t done so much as a push-up since getting out of prison, but he wanted to hang with his friend. Briggs and his training partners set off at their usual clip; within a few minutes they’d disappeared from Rahsaan’s view. By the time they were doubling back, he’d barely made it a half mile.

Rahsaan never liked feeling physically inferior. So back in La Jolla, he started running a few times a week, going to the gym, whatever it took. Before long he was up to five miles. And the next time he ran with Briggs, he could keep up. After that, he says, “Running just became my thing.”

FOR YEARS, RAHSAAN HAD BUCKED AT TAKING RESPONSIBILITY for the murder that sent him to prison. The other guys had guns, too, he insisted. If he hadn’t shot them, they’d have shot him. It was self-defense.

In the moment, he had no reason to think otherwise. It was April 2000. A friend had arranged to sell $50,000 worth of weed, and Rahsaan went along to help. They met in the parking lot of a strip mall in L.A., broad daylight. The buyers brought guns instead of cash, things went sideways, and, in a flash of adrenaline, Rahsaan used the 9mm he’d packed for protection, killing one man and putting the other in critical condition. He was 29 and had been in California eight months.

After awaiting trial for three years in the L.A. County jails, Rahsaan was sentenced to 55 years to life. But for the crushing finality of it, the grim interminability, the prospect of never seeing the outside world again, he was on familiar ground. Even Brownsville had been a kind of prison—one defined, as Rahsaan puts it now, by division and neglect, a world unto itself that societal forces made nearly impossible to escape. He was used to life inside.

Rahsaan spent the next 10 years shuttling between maximum security facilities, the bulk of those years at Calipatria State Prison, 30 miles from the Mexican border. By the time he got to San Quentin, he was 42.

As part of the prison’s restorative justice program, Rahsaan met a mother of two young men who’d been shot, one killed and the other critically injured. Her pain, her dignity, her ability to forgive her sons’ shooters prompted Rahsann to reflect on his own crime. “It made me feel like, damn, I did this to his mother,” he says. “I did this to my mother. You don’t do that to Black mothers. They go through so much.”

ABOUT 2 MILLION PEOPLE ARE INCARCERATED IN THE UNITED States today, roughly eight times as many as in the early 1970s. Nearly half of them are Black, despite Black Americans representing only 13 percent of the U.S. population.

This disparity reflects what the legal scholar and author Michelle Alexander calls “the new Jim Crow,” an invisible system of oppression that has impeded Black men in particular since the days of slavery. In her book of the same title, Alexander unpacks 400 years of policies and social attitudes that have created a society in which one in three Black males will be incarcerated at some point in their lives, and where even those who have been paroled often face a lifetime of discrimination and disenfranchisement, like losing the right to vote. If you hit a wall every time you try to do something, are you really free? More than half of the people released from U.S. jails and prisons return within three years.

After Rahsaan got out of Cayuga back in 1992, with a felony on his permanent record, he’d had trouble doing just about anything legit: renting an apartment, finding a decent job, securing a loan. Though he’d paid for the Mercedes SUV he drove to California, the lease was in his girlfriend’s name. Selling crack had provided financial solvency, and his success in New York made him feel invincible. One weed deal in California seemed easy enough. But he wasn’t naive. Rahsaan packed a gun, and if he felt he had to use it, he would.

Today Rahsaan feels deep remorse for what transpired from there. But back then he saw no other way. “When we have a grievance, we hold court in the street,” he says of growing up in the Brownsville projects. “There’s no court of law, there’s no lawsuits.” Even while incarcerated, Rahsaan continued to meet threats with violence. But he also found that in prison, as in Brownsville, respect was temporary. “If you stab somebody, people leave you alone,” he says. “But you gotta keep doing it.”

Not long after Rahsaan got to Calipatria, around 2003 or 2004, an older man named Samir pulled him aside. “Youngster, there’s nobody that you can beat up that’s gonna get you out of prison,” Rahsaan remembers Samir saying. “In fact, that’s gonna make it worse.” Rahsaan thought about Muhammad Ali, how he would get his opponents angry on purpose so they’d swing until they wore themselves out. He realized that when you’re angry, you’re not thinking clearly or moving effectively. You’re not responding; you’re reacting.

The next time Rahsaan saw Samir was in the yard at Calipatria. They were both doing laps, and the two men started to run together. Rahsaan told Samir about the impact his words had on him, how they helped him see he’d always let “somebody else’s hangup become my hangup, somebody else’s trauma become my trauma.” Each time that happened, he realized, he slid backward.

Rahsaan began exploring various religions. He liked how the men in the Muslim prayer group at Calipatria encouraged him to think about his past, and the way they talked about God’s plan. He thought back to that day in April 2000 and came to believe that God would have gotten him out of that situation without a gun. “If I was meant to die, I was meant to die,” he says. “If I’m not, I’m not.” He started to see confrontations as tests. “I stopped feeding into the negativity and started passing the test, and I’ve been passing it consistently since,” he says.

CLAIRE GELBART PLACED HER BELONGINGS IN A PLASTIC TRAY AND WALKED THROUGH THE METAL detectors at the visitors’ entrance at San Quentin. She crossed the Yard to the prison’s newsroom. It was late fall of 2017, and Gelbart had started volunteering with the San Quentin Journalism Guild, an initiative to teach incarcerated people the fundamentals of newswriting and interviewing techniques.

Historically infamous for housing people like Charles Manson and Sirhan Sirhan, the man convicted of killing Robert Kennedy, and for having the only death row for men in California, San Quentin has in recent years instituted reforms. By the time Rahsaan arrived, the facility was offering dozens of programs, had an onsite college, and granted some of the individuals housed there considerable freedom of movement. Hundreds of volunteers pass through its gates every year.

Rahsaan was in the newsroom working on a story for the San Quentin News, where he was a staff writer. Gelbart and Rahsaan started to chat, and within minutes they were bonding over running. They talked about the San Quentin Marathon—in which Rahsaan was proud to have placed 13th out of 13 finishers in 6 hours, 12 minutes, and 23 seconds—and Gelbart’s plans to run her first half marathon that spring. “It was like I lost all sense of place and time,” Gelbart says, “like I could have been in a coffee shop in San Francisco talking to someone.”

In weekly visits over the next year, Gelbart and Rahsaan talked about their families, their hopes for the future. Gelbart had just graduated from Tufts University with dreams of being a writer. Rahsaan was working toward a college degree, writing for numerous outlets like the Marshall Project and Vice, and learning about podcasting and documentary filmmaking. In 2019, when Gelbart was offered a job in New York, she told Rahsaan she felt torn about leaving—they’d become close friends. They made a pact that if Rahsaan ever got out of prison, they would run the New York City Marathon together. “We couldn’t think of a better thing to celebrate him coming home,” Gelbart says.

When Rahsaan was sentenced, he still had hope for a successful appeal. But when his appeal was denied in 2011, he realized he was never going home. His parole date was set for 2085.

At the time, though, the political appetite for mass incarceration was starting to shift. Gray Davis, who was governor of California from 1999 to 2003, had never granted a single pardon; and his successor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, granted only 15. Then, between 2011 and 2019, Governor Jerry Brown pardoned or commuted the sentences of more than 1,300 people. Studies show that the recidivism rate among those who had been serving life sentences is less than 5 percent in a number of states, including California. And according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice, 98 percent of people convicted of homicide who are released from prison do not commit another murder.

In the fall of 2018, Governor Brown approved Rahsaan for commutation, but it was now up to his successor, Gavin Newsom, to follow through. And until a release date was set, there were no guarantees.

Back at San Quentin, Rahsaan was busier than ever. He was working on his fourth film, Friendly Signs, a documentary funded by the Marshall Project and the Sundance Institute; it was about fellow 1,000 Mile Club member Tommy Lee Wickerd’s efforts to start an ASL program to aid a group of deaf and hard-of-hearing newcomers to the prison. He had recently been named chair of the San Quentin satellite chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists and became a cohost and coproducer of Ear Hustle, a popular podcast about life in San Quentin that in 2020 was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize. He was also sketching out plans for a nonprofit, Empowerment Ave, to build connections to the outside world for other incarcerated writers and artists and to advocate for fair compensation. And after five years, he was just one history class away from getting his associate’s degree from Mount Tamalpais College.

In January 2020, Rahsaan began his final semester, eager to don his cap and gown that June. MTC always organized a festive graduation ceremony in the prison’s visiting room, inviting families, friends, students, and staff. Then COVID-19 hit. Lockdown. All classes canceled until further notice. The 1,000 Mile Club suspended workouts and races as well, its 70-plus members scattering throughout the prison, not sure when or if they’d ever get together again. Covid would officially kill 28 people at San Quentin and make many more very ill. College graduation, let alone races in the Yard and parole hearings, would have to wait.

For the first time since arriving at San Quentin, Rahsaan felt claustrophobic in his 4-by-10-foot cell. He couldn’t work on his films or go to the newsroom. All he could do was read and write, alone. After George Floyd was murdered that May, Rahsaan fell into a depression. He remembered something Chadwick Boseman had said in a 2018 commencement speech at Howard University: “Remember, the struggles along the way shape you for your purpose.”

Rahsaan decided his purpose was to write. Outside journalists couldn’t enter the prison during the pandemic, but their publications were thirsty for prison Covid stories. Rahsaan saw an opportunity. Between June 2020 and February 2023, he published 42 articles, and thanks to Empowerment Ave, he knew what those articles were worth. As a writer for the San Quentin News, Rahsaan earned $36 a month; those 42 articles for external publications netted him $30,000.

DOZENS OF PEOPLE GATHERED OUTSIDE SAN QUENTIN’S GATES. IT WAS A FRIGID MORNING IN EARLY February 2023; the sun hadn’t yet risen. Among those assembled were two cofounders of Ear Hustle, Earlonne Woods and Nigel Poor, along with executive producer Bruce Wallace, recording equipment in hand. A procession of white vans, each carrying one or two men, arrived one by one. After three or four hours, the air had warmed to a balmy 60 degrees. Another van pulled up, Rahsaan got out, and the crowd erupted. Nearly 23 years after he’d been sentenced to 55 years to life, Rahsaan Thomas had been released.

Rahsaan got into a Hyundai sedan and was soon headed away from San Quentin. Wallace sat in the back, recording Rahsaan seeing water, mountains, and a highway from the front seat of a car for the first time in decades. “I feel like I’m escaping,” he joked. “Is anybody chasing us? This is amazing. This is crazy.”

Rahsaan called his mom, who wasn’t able to make it to California for his release.

“Hey, Ma, it’s really real,” he said, breathless with joy. “I’m free. No more handcuffs.”

Jacqueline’s exuberance can be heard in her laughter, her curiosity about what his first meal would be (steak and French toast), and her motherly rebuke of his plan to buy a Tesla.

“You ain’t been drivin’ in a while and I know you ain’t the best driver in the world,” she teased.

Rahsaan moved into a transitional house in Oakland and wasted no time adjusting to life in the 21st century. He got an iPhone, and a friend gave him a crash course in protecting himself from cyberattacks. He’s almost fallen for a few. “There’s some rough hoods on the internet,” he jokes. Earlonne Woods, who was paroled in 2018, and others taught Rahsaan how to use social media. He opened Instagram and Facebook accounts and worked on his own website, rahsaannewyorkthomas.com, which a friend had built for him while he was in San Quentin to promote his creative projects, Empowerment Ave, and even a line of merch.

Despite all the excitement and chaos, Rahsaan never forgot about the pact he’d made with Claire Gelbart. He found her on Facebook and sent a simple, two-line message: “Start training. We have a marathon to run.”

IN LATE MARCH, SIX WEEKS AFTER HIS RELEASE, RAHSAAN FLEW TO NEW YORK CITY. IT WAS THE FIRST time he’d been home in nearly a quarter century, and he hadn’t flown since before 9/11. The security protocols at SFO reminded him more of prison than of the last time he’d been in an airport. Actually, “it was worse than prison,” he jokes. They confiscated his jar of honey.

The changes to his home borough were no less surprising. He’d come to New York to take work meetings, see family, and catch a Nets game at Barclays Center in downtown Brooklyn. Rahsaan barely recognized Barclays; it had been a U-Haul lot the last time he was there, and skyscrapers now towered over Fulton Mall, where he used to buy Starter jackets at Dr. Jay’s and Big Daddy Kane tapes at the Wiz.

He met up with Gelbart on Flatbush Avenue, where come November they’d be just hitting mile 8 of the New York City Marathon. They hadn’t been allowed to touch at San Quentin and weren’t sure how to greet each other on the outside. “It was weird at first, because I was like, do we hug?” Gelbart recalls. But the awkwardness faded fast, and as they walked, Gelbart saw a different side of Rahsaan. “He seemed so much more relaxed,” she says. “Much happier, much lighter.”

Back in 1985, just a few blocks from where Rahsaan and Gelbart walked now, Rahsaan, his brother Aikeem, and his friend Troy had been on their way home from the Fulton Mall when out of nowhere, about a dozen guys rolled up on them. They started beating on Troy and, for a minute, left Rahsaan and Aikeem alone. Images of his father, throat slashed, flashed through Rahsaan’s mind. He pulled a rug cutter out of his pocket, ran to the smallest guy in the group, and jabbed it into the back of his head. “They looked at me like they were gonna kill me,” Rahsaan says. He threw the blade to the ground, slid his hand inside his coat, and held it there. “Y’all wanna play? We gonna play,” he said. The bluff worked; the guys ran. It was the first time Rahsaan had ever stabbed someone.

Change sometimes occurs gradually, and then all at once. That was a different Brooklyn, a different Rahsaan. He began to confront his own violence when he had met Samir some 20 years before, and continued to do so through his studies, his faith, his work in restorative justice, and his own writing. But the origin of his tendency toward violence, the death of his father, remained firmly rooted in his psyche. Then, in 2017, Rahsaan spoke for the first time with his estranged half-brother, Carl.

Carl had read Rahsaan’s work, and asked why he always said their father had been murdered.

“That’s what grandma told me,” Rahsaan said.

“But he wasn’t murdered,” Carl told him. “He killed himself.”

And it wasn’t in 1982, as Rahsaan remembered, but in 1985—the same year Rahsaan started carrying blades.

Rahsaan didn’t believe it until Carl sent him a copy of the suicide note. Even then he remained in shock. “To think I justified violence, treating robbery like a life-or-death situation, over a lie,” he says. Jacqueline was as surprised as Rahsaan to learn the truth of Carlos’s death. He never seemed troubled or depressed to her when they were together, but, “You can’t really read people,” she says. “You don’t know.”

Rahsaan still can’t account for why his grandmother told him what she did, nor for the discrepancy between his memory and the facts. Regardless, after more than 30 years, Rahsaan was finally able to let go of the one trauma that had calcified into an instinct to kill or be killed. And he has no intention of dredging it back up.

THE FASTEST RUNNER IN THE 1,000 MILE CLUB’S HISTORY IS MARKELLE “THE GAZELLE” TAYLOR, WHO was paroled in 2019 and went on to run 2:52 in the 2022 Boston Marathon. Rahsaan is the slowest. At San Quentin, he was often the last one to finish a race, but that wasn’t the point—he liked being out in the Yard with the guys. It gave him a sense of belonging, and not just to the 1,000 Mile Club, but to the running community beyond.

Like every other 1,000 Miler who gets released from San Quentin, Rahsaan had a rite of passage to conquer. On Sunday morning, May 7, 2023, he met a handful of other runners from the club and a few volunteer coaches in Mill Valley. After a decade of gazing up at Mount Tam from the Yard as he completed one 400-meter loop after another, Rahsaan was finally about to run over the mountain all the way to the Pacific.

The runners did a few final stretches, wished one another luck, and started to run. Almost immediately they had to climb some 700 stairs, many made of stone, and the course only got more treacherous from there. Uneven footing, singletrack paths, and 2,000-plus feet of elevation all conspire to make the Dipsea notoriously difficult. The giant redwoods and Douglas firs along the course were lost on Rahsaan; he never took his eyes off the ground.

One of the coaches, Jim Maloney, stayed with Rahsaan as his guide, and to help him if he slipped or fell. Markelle Taylor came too, but said he’d meet them in Stinson Beach. He knew how dangerous the trail was, Rahsaan says, and had vowed to never run it again. After his own initiation, Rahsaan decided that he, too, would never do it again. “I’ve been shot at,” he says. “I’ve been in physical danger. I don’t want to revisit danger.”

Rahsaan now logs most of his miles on a treadmill because of knee issues, but on occasion he ventures out to do the 3.4-mile loop around Lake Merritt, a lagoon in the heart of Oakland. He decided to use the New York City Marathon to raise money for Empowerment Ave, and to accept donations until he crossed the finish line in Central Park. Gelbart wrote a training plan for him and got him a new pair of shoes. In prison, Rahsaan had run in the same pair of Adidas for three years, and he was excited to learn about the maximalist shoe movement. Gelbart tried to interest him in Hokas, but Rahsaan thought they were ugly. He wanted Nikes.

In June, Gelbart went to the Bay Area to visit family and met Rahsaan for a six-mile run around Lake Merritt. As they looped the lake at a conversational 11:30 pace, they talked about work, relationships, and, of course, the New York City Marathon. Rahsaan was disappointed to learn that he would probably not be the last person to finish. (He still holds the record for the slowest San Quentin Marathon in its 15-year history, and he hopes no one ever beats it.) Besides, the more time he spent on the course in New York, he figured, the longer people would have to donate to Empowerment Ave.

On Sunday, November 5, Gelbart and Rahsaan made their way to Staten Island. Waiting at the base of the Verrazzano Bridge, Gelbart recorded Rahsaan singing along to Frank Sinatra’s “New York, New York” for Instagram, and captioned the video “back where he belongs.” They documented much of their race as they floated through Brooklyn, Queens, Manhattan, and the Bronx: greeting friends along the course, enjoying a lollipop on the Queensboro Bridge, beaming even as their pace slowed from 11:45 per mile for the first 5K to 16:30 for the last. Rahsaan finished in six hours, 26 minutes, and 21 seconds, placing 48,221 out of 51,290 runners. The next day, he sent me a text: “The marathon was pure love.” What’s more, he received more than $15,000 in donations for Empowerment Ave, enough to start a writing program at a women’s prison in Texas.

Every runner has an origin story. Every runner finds a reason to keep going. At Calipatria, Rahsaan liked to joke that he ran because if an earthquake ever came along and brought down the prison’s walls, he needed to be in shape so he could escape and run to Mexico. In San Quentin, he ran for the community. Today he has a new reason. “I heard that running extends your life by 10 years,” he says, “and I gave away 22.” Now that he’s out, his motivation has never been higher. He has so much to do.

Login to leave a comment

Unleash Your Inner Runner on These Five Amazing California Trails

California boasts some of the most stunning trails in the world. The correct jogging trail can make all the difference in your training, whether you are a seasoned pro or a novice. The topic of staying active and sports, in general, has never been more prominent at present, especially with the sun shining and the new NFL campaign right around the corner.

Numerous well-known online bookmakers have made an effort to profit from this popularity by offering a variety of casino slots for sports fans. Soccermania, a game geared toward football lovers, may be something you'll like if you're eagerly anticipating the aforementioned return of the sport.

The slot game allows you to choose from the 2022 World Cup teams, transporting you into the world of football through immersive animations. And following a run in the scorching California sun, such games may prove to be the ideal way to unwind.

But if you frequently go for runs in California, which routes should you be considering? In this article, we'll explore some of California's best running trails and give you all the information you need to choose the ideal running location for you.

Muir Woods Trail in Marin County

Muir Woods Trail in Marin County is truly a runner's paradise, with countless reasons why it's considered one of the best running spots. A standout feature is the stunning scenery, as you'll be surrounded by majestic redwoods, providing an awe-inspiring view that is unparalleled. The trail itself is well-maintained, ensuring easy navigation without the risk of getting lost in the forest. Moreover, you'll enjoy a peaceful and serene experience, away from the hustle and bustle of the city, as traffic is minimal along this route.

Mount Tamalpais State Park in Marin County

Mount Tamalpais State Park offers a breathtaking perspective of the San Francisco Bay Area, and the trail network caters to runners of all abilities with a variety of terrains and challenges. The legendary Dipsea track, a strenuous and beautiful track that extends 7.4 miles from Mill Valley to Stinson Beach, is available for running.

As an alternative, consider hiking the routes that lead to picturesque viewpoints like Mount Tamalpais' East Peak or West Peak. The opportunity to run in the shadow of old-growth redwood trees is one of the special features of this state park. Take your running gear, then, and head to Mount Tamalpais State Park for a memorable and beautiful running experience.

Bay Area Ridge Trail

375 miles of the San Francisco Bay Area's slopes and hillsides are traversed by the Bay Area Ridge Trail. If you are looking for a challenging workout, this beautifully maintained trail starts in an urban setting, but quickly enters stunning natural landscapes. You can enjoy stunning Bay Area views while running this track, and if you're lucky, you might even spot some wildlife. Although the route is accessible year-round, the greatest seasons to go are winter and spring when the mountains are covered in wildflowers.

Griffith Park in Los Angeles

Griffith Park boasts an extensive network of trails, catering to both beginners and seasoned runners. The awe-inspiring views of the Hollywood Hills and the bustling cityscape serve as a remarkable source of motivation during your run. Not to mention, the park is also home to notable landmarks like the Griffith Observatory, allowing you to blend your workout with a touch of culture and immerse yourself in the park's natural splendor.

Moreover, Griffith Park offers a range of amenities, including water fountains and restrooms, ensuring that runners can stay refreshed and hydrated throughout their workout. It's no surprise that Griffith Park is widely regarded as one of SoCal's most scenic and accessible spots for a satisfying run.

Santa Monica State Beach in Los Angeles

Santa Monica State Beach is the ideal location for you if you enjoy running by the sea. The Pacific Ocean delivers a pleasant, invigorating air as you run down the three miles of white sand beach. You may see some famous sites while running along the beach, including Venice Beach, Muscle Beach, and the Santa Monica Pier. The best time to go is in the winter to avoid the crowds and the scorching temperature, although a run at dusk in the summer is as amazing.

Conclusion

Going to the trail and running your heart out is a fantastic way to stay in shape while being immersed in nature. The five trails described throughout this article are all great places for long runs on varied terrain. With the combination of mountainous regions, beach sides, and scenic city views, there’s something for everyone in California.

In whatever trail you choose to indulge in, remember that every step will bring you closer to unwinding from the stresses of everyday life and closer to becoming one with nature. So put those running shoes on and unleash your inner runner today!

Login to leave a comment

More Prize Money Is Flowing Into Trail Running. What Does That Mean for the Sport?

Annie Hughes, one of the top trail runners in the U.S. for the past two years, had another amazing season running ultra-distance races in 2022. On September 17, the 24-year-old Hoka-sponsored runner and part-time college student won the Run Rabbit Run 100 in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, her fourth win of 100 miles or longer since April. Earlier this year, she won the Coldwater Rumble 100 in January, Cocodona 250 in April and the High Lonesome 100 in July.

Those were all exceptional efforts in really challenging races, but the big difference she experienced after crossing the Run Rabbit Run finish line, 21 hours and 26 minutes later, was that she won $17,500. (And yes, she was handed one of those cartoonish, oversized checks at the awards ceremony.)

Run Rabbit Run is one of the rare American trail races that offers a relatively large prize purse, and for a decade, it's been the largest in the sport. Hughes earned $15,000 for winning the women's race and split another $5,000 with Arizona trail runner Peter Mortimer (who placed 12th overall) as part of the event's new team competition.

"That wasn't the reason I was drawn to the race, but it was definitely pretty cool to win that much money," Hughes said. "I'm glad I did it, because it wound up being a really great race with an amazing course on a beautiful day."

The origins of trail running were always more about the joy and freedom of ambling through the natural world, and less about the specific time and pace of any run or race, which is why winning big cash prizes is mostly uncommon in the sport, even for top-tier runners like Hughes. Over the past two years, Hughes has won 10 races of 50 miles or longer, yet her Run Rabbit Run victory was the first time she's ever earned money for her efforts.

More sponsorship money and bigger cash prizes are flowing into the sport, helping the top athletes earn a full-time living in the sport and become global stars. But that evolution has also created a desperate need for a unified governing body and more consistent drug-testing as doping becomes a more acute concern.

A Windfall of Prize Money

Historically, America's biggest and most notable trail running races haven't offered any prize money at all-Western States 100, Hardrock 100, Dipsea Trail Race, Leadville 100, Mount Marathon Race, Seven Sisters, Black Mountain Marathon/Mount Mitchell Challenge-partially because races simply couldn't afford to pay it, and also because, at the soul of the sport, that's not what the races were historically about or why most top runners were competing.

But with the continued growth of the sport-trail running has grown by 231 percent over the past 10 years, according to one report-and the dawn of a new level of professionalization over the past decade, there is a lot more money being injected into the sport. That includes more high-profile events and race series, more brands investing in the sport, more sponsored runners and trail running teams, as well as a growing expectation that prize money should be part of the equation as it is in road running, triathlon, and even obstacle course racing.

For many years, The North Face 50 near San Francisco was one of the only ultra trail races in the world to offer a significant prize purse. From its inception in 2006, until it disappeared after 2019, that race famously awarded $30,000 in prize money, which included $10,000 to the top finishers in the men's and women's races, plus $4,000 for second and $1,000 for third. It was a race to look forward to at the end of the calendar year, both for the cash awards and the prize-induced competition that drew top runners from around the world.

During that span, Run Rabbit Run, though a lower-profile race, quietly began dishing out some of the biggest payouts in the sport, in part because race organizers Fred Abramowitz and Paul Sachs believe in rewarding its top athletes for their efforts (as well as giving back to the community via even bigger charitable contributions). The race winnings come primarily from entry fees of the 600-runner event and sponsors, if and when the race has them. That wasn't possible back in the early days of the sport, when entry fees were minuscule and cash sponsors were mostly non-existent, but things have started to change.

Abramowitz and Sachs, who both earn their living as attorneys, are unique in that they want to give back to the elite athletes and the Steamboat Springs community, but they also want to help grow the sport. Abramowitz outlined what he calls "A Blueprint for Sponsors of Ultra Running," a three-page document that explains how and why trail ultrarunning-both as a sport and as individual races-can connect to more casual runners, sports fans, and the general public.

He points to the rampant growth of NASCAR, Professional Bull Riding, and professional poker over the past 20 years from their roots as fringe sports, relatively speaking, to mainstream spectacles with massive fan bases, TV contracts, and social media followings. Trail and ultrarunning aren't there yet, Abramowitz has noted, but they've certainly been growing rapidly.

"Today millions watch those events, though the actual number of participants is minuscule," Abramowitz wrote in his missive. "Ultrarunning can learn from these events: it needs new ideas, new ways of attracting the already committed runners and the casual sports fan to our terrific sport. Fields need to be competitive and races [need to be] dramatic; there are hundreds of 100-mile races, but those that offer competitive fields are a handful at most. Most ultra-races offer spectacular scenery in interesting venues."

Abramowitz said sponsors should support races such as Run Rabbit Run that offer prize money not merely because it's good for sport, but also because prize money can attract competitive fields, and competitive fields attract interest-from spectators, participants, potential sponsors, and the general public. He also points out that having prize money at more domestic races is a way to keep the sport from becoming entirely Euro-centric, which has been an increasing trend in the past several years.

The trend of cash purses seems to be increasing, and on the face of it, that's good for elite athletes capable of podium finishes. But it's a complex topic and one that certainly will simultaneously increase the competitiveness of the sport while, some argue, continue to pull the sport away from its organic, racing-in-nature roots that was mostly viewed as the antithesis of competitive road racing.

On the same day Run Rabbit Run paid out $75,000 in total prize money, the Pikes Peak Ascent awarded $18,000 in prize money for its top 10 finishers-including $3,000 apiece to the men's and women's winners-while the Pikes Peak Marathon, on September 18, had an additional $10,500 in total prize money for the top five runners. The races also offered $2,000 (Ascent) and $4,000 (Marathon), respectively, as course-record bonuses, and a $10,000 premium to any runner surpassing a pie-in-the-sky time well ahead of the course records. None of those records were broken, but the $28,500 in total prize money-partially backed by the Salomon-sponsored Golden Trail Series-was one of several large prize purses offered at U.S. races this year.

Other big American prize purses were also primarily tied to the Golden Trail Series events-the $50,000 spread over four races at the mid-June Broken Arrow Sky Races in Olympic Valley, California, and the September 25 Flagstaff Sky Peaks 26K race in Flagstaff, Arizona, where runners competed for $18,000 in prize money and a chance to compete at the Golden Trails World Series Final, and the $15,000 winner's earnings at the Madeira Ocean & Trails 5-Day Stage Race in October.

Also of note, the November 18-20 Golden Gate Trail Classic paid out $25,000 in total prize money to the top five finishers in both the 100K and half-marathon races, which were part of this year's nine-race $270,000 Spartan Trail World Championship Series.

Meanwhile, the Cirque Series, sponsored by On, paid out $3,600 in total prize money at each of its six sub-ultra mountain running races in the U.S., including $1,000 for the men's and women's winners. The Mt. Baldy Run-to-the-Top on September 5 in Southern California offered $3,000 to runners who broke the event's longstanding course records, and Joe Gray and Kim Dobson obliged by taking down each mark.

Most U.S. Trail and Mountain Running Championships have a minimum of $2,000 in prize money. Typically that comes from regional sponsors eager to support the local race organizations, such as the case with Northeast Delta Dental's contributions behind this year's Loon Mountain Race in Lincoln, New Hampshire, which hosted the U.S. Mountain Running Championships. That event had a $1,500 total prize purse that was paid out to the top three men and women in each race, but it also had an additional $1,500 for an Upper Walking Boss premium that was spread among the top three fastest times in each gender on the super-steep upper part of the course.

Meanwhile, the 2022 World Mountain and Trail Running Championships in Thailand paid out $66,000 to the top five finishers over four races, including $4,000 to the winners of each event.

"(The prize money) is way better than it's ever been, both for the athletes earning it and the number of sponsors who are contributing to it," says Nancy Hobbs, executive director of the American Trail Running Association and the chairperson of the USATF Mountain Ultra Trail Council that oversees national championship races and the U.S. Mountain Running Team.

From a longer view over the past decade or so, Joe Gray agrees there is more money coming into the sport than ever before. As a top-tier pro since 2008 and 21-time U.S. champion, he's regularly won more prize money at high-level races in Europe for more than a decade. But more than the growth of prize money, he has seen more brands interested in putting money behind athletes, races, and the sport in general.

"I think there has always been prize money there, and if you're successful you could make a lot more money really quickly," said Gray, a two-time World Mountain Running Champion. "I do think there is more money coming from the sponsors paying out better contracts and bigger bonuses, which I think will wind up being more beneficial to athletes overall."

Most elite trail runners get annual stipends from their sponsoring brands and bonus money for top performances. Gray is backed by Hoka, but he also has sponsorship deals with Fox River Socks, Kriva, Never Second, Knockdown, Tanri, Momentous, Casio, and GoSleeves. In addition to Hoka, Annie Hughes gets additional support from Ultraspire, Coros, and Tailwind Nutrition. But the life of professional trail runners-independent contractors who don't get healthcare and retirement program benefits-can get expensive with the growing cost of travel, regular bodywork/physio treatments, and private health insurance.

The sport's top-tier elite athletes-Joe Gray, Kilian Jornet, Courtney Dauwalter, Jim Walmsley, Maude Mathys, and Scott Jurek, among others-make a good living from their sponsorships. But there are really only a handful American trail runners making more than about $50,000 a year from shoe brand sponsorships. (Most "sponsored" trail runners are making somewhere between $10,000 to $30,000 per year.) The bottom line is that winning prize money, for those who are fast enough to consistently finish on the podium in big races, certainly helps make ends meet and is necessary to keep the sport's top athletes from having to work other jobs so they can focus entirely on training, recovery, and racing.

"This [2022] is the first year I've gone all-in on trail running," said Hughes, who worked as a waitress in Leadville the previous two years. "I'm able to live off what I make, but I'm not really saving anything. So it was really nice to win that money because then I can put some away in savings."

Higher European Standards

So far, Abramowitz appears to be right about the sport shifting to more of a European focus, and it's, at least in part, tied to the increased prize money that has attracted competitive athletes. While many top-tier European events have paid out modest prize purses for years, some of those races have also helped out visiting runners by way of travel stipends, hotel accommodations, or appearance fees. That's partially because European races are generally larger (500 to 1,000 participants or more) than U.S. races (typically fewer than 500 participants).

Unlike Hughes, who only raced in the U.S. this year, American runner Abby Hall, who runs for the Adidas-Terrex team, raced three times in Europe and earned prize money each time. She placed second in the Transgrancanaria 126K in the Canary Islands in March (which doubled as the Spartan Trail World Championship), finished third in the CCC 100K in Chamonix in August, and won the Transvulcania by UTMB 72K back in the Canary Islands in October.

Like Hughes, Hall receives an annual stipend and race bonuses from her sponsor, but admits it's been nice to have more opportunities to win money-both because it helps her make a living wage and because it's consistent with other professional endurance sports.

"In the past, it hadn't even been a consideration before, for how income would work out as an athlete," Hall said. "But this year it actually added up to be a decent amount. I'm grateful for the opportunities."

In 2022, American runner Hayden Hawks won an off-the-radar 100K a race in Krynica, Poland, and brought home the 100,000 zloty winner's prize ($26,000), one of the bigger individual purses ever awarded in trail running. In 2017, when Hawks won the CCC race, he didn't win anything because UTMB had refused until 2018 to offer prize money at its races, partly because race founders Catherine and Michel Poletti have believed that increased prize money will bring more incentive for some athletes to consider doping or that agents would take too big of a cut.

UTMB finally began offering prize money to podium finishers in 2018 with a total purse of about $34,000 (35,000) and continued that through 2021. But after forging a business relationship with Ironman and launching the new UTMB World Series, it has increased the prize money awarded in Chamonix. In 2022, UTMB said it paid out about $162,000 in total prize money (the approximate equivalent of its stated 156,000 prize purse) to the top 10 men and women finishers of the UTMB, CCC, and OCC races.

That includes $10,400 to the winners of each of those races, with approximately $5,200 going to second-place finishers and $3,125 for third. Fourth- and fifth-place finishers in each of those races earned about $1,500, while 6th through 10th took home $1,000.

While those more notable ultrarunning paydays can be big windfalls for a trail runner, they still pale in comparison to what elite-level road marathoners and triathletes earn at the biggest races that have a much larger audience, including live TV coverage. For example, the 2022 Boston Marathon awarded $876,500 in prize money and $150,000 to the winners, while New York City Marathon paid out $530,000 in total prize money at its November 6 race, including $100,000 to the men's and women's winners. The 2021 Ironman World Championships in St. George, Utah, had a $750,000 prize purse, including $125,000 to the winners, similar to what was awarded at the 2022 Ironman World Championships October 6-8 in Hawaii.

While only a few top trail runners could have opted to pursue a marathon or triathlon career instead of trail running, what's more relevant is the spike of growth trail running. Although it is not yet internationally televised as major marathons and triathlons are, the surge in participation and livestream viewing options is starting to bring in more media attention and sponsorship money than ever before. And more media attention begets more participation and professionalization.

"I think we'll definitely see ultra-trail running continue to grow for years to come," says Mike McManus, director of global sports marketing for Hoka. "I think it's at a point where it's just on the cusp of the real growth that's coming and all that will come with it, similar to where the marathon was in the 1980s and triathlon in the 1990s. It might never be as big as marathoning, but trail running will definitely get more built out as it continues to grow."

"It's nice to make some money for the sport we do. This is my job, and being able to support my family with a decent chunk of money is pretty nice," Hawks says. "I definitely don't go after races just for money, but if there is a gap in my schedule where I can win a little bit of money, I am definitely going to take advantage of that for sure. I want to continue to be in this sport and live this lifestyle as long as I can, so knowing that there are sponsors and races investing more in runners is something I am really grateful for."

The Ongoing Dilemma

While Abramowitz and Sachs have been eager to give out prize money at Run Rabbit Run, not all races are equipped to do so. Many U.S. races are garage-shop operations that barely break even, while some are just too small to make it happen. The Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run (WSER) is operated by a non-profit organization, and offering prize money goes against the mission of the race, says race director Craig Thornley.

The biggest concern that race directors have, including Thornley, is that prize money attracts athletes willing to use performance-enhancing drugs because the sport lacks a comprehensive anti-doping strategy that includes both post-race testing and out-of-competition testing.

"In general, I think the prize money is probably a good thing because professional athletes are able to make a living," Thornley said. "But I think, as a sport, we'll probably have to be more aware of people trying to use drugs or some other ways to get that prize money."

A few years ago, the Western States 100 famously announced its zero-tolerance policy regarding the use of performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) that prohibits any athlete who has been determined to have violated anti-doping rules or policies-by World Athletics, World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA), or any national sports federation-is ineligible for entry into the WSER. Although Western States has regularly drug-tested its top finishers, only a few other big trail or ultra-distance races test its finishers with a WADA-sanctioned program.

Thornley believes the incentive to cheat has probably increased as more brands have stepped up to sponsor athletes, but the increase in prize money probably makes it more tangible.

He's not the only one. Ultrarunning coach and podcaster Jason Koop, an outspoken proponent for authentic drug-testing in the sport, agrees, saying that it's time for the sport to collectively start developing mandatory drug-testing protocols, even on a small scale. While he doesn't believe doping is prevalent in trail running, he believes it's definitely already an issue.

"People would be fooling themselves if they thought that every trail running performance was clean. If you think that that's the case, then I have a bridge to sell you," Koop says. "Prize money or no prize money, I think the bigger thing is that the ecosystem is developed enough and there is enough financial reward at stake to where everyone kind of owes it to everybody else to get something done."

In other words, it's time for the sport to take some next steps-either by big governing bodies or small factions of people interested in the long-term health of the sport-to develop more structure and universal anti-doping policies.

by Trail Runner Magazine

Login to leave a comment

VO2 Max Output As A High-Performance, Anti-Aging Superweapon

This article is purely theoretical. Some readers will think that the theory is obvious on its face, and others will think that it's wrong. The joy of talking about training theory at the intersection of science and anecdote is that there are too many physiological metrics to track, and too many variable responses to interventions, so the resulting conclusions fall somewhere on the spectrum between fundamental truth and biased bullshit. Throughout, I'll try to check my biases and acknowledge the unknowns.

You know I'm nervous about writing an article when the first paragraph is undercutting myself with disclaimers. To be fully real with you: I am unsure on this one.

This article tries to articulate an unexpected observation that now forms a cornerstone of my coaching approach, but I have too much self-doubt to ignore my biases. It's like looking at a diagram of constellations in the night sky. The diagram might say: "This is the mighty hunter, pursuing the courageous bear."

So remember, as I try to break this down, I'm describing a scene with a mighty hunter, but I'm painfully aware it might just be dots and a phallus.

Here it is, distilled down to 3 sentences:

Output at VO2 max while climbing (measured via grade-adjusted pace) may have a high predictive value for athlete progression and regression over time, particularly with age.

The metric likely is a proxy variable for limitations of mechanical output that are faced by some athletes from the start of their running journeys, and confronted by all athletes with age.

Constant reinforcement of the metric may improve performance at all effort levels, including long ultras, and can seem to reverse the athletic decline process in some cases.

That's it. To paraphrase The Lion King: Simba, let me tell you something that my father told me. Look at the stars. YOU SEE WHATEVER YOU WANT TO SEE.

Observations From Athlete Training

Let's have some fun with training theory, reverse-engineering why I think this conclusion is significant and may be overlooked. When my co-coach/wife Megan and I started coaching (we talk about this topic more on episode 114 of our podcast), we began as acolytes to coaches like Renato Canova and Jack Daniels who excelled with Olympic-level athletes on the road and track.

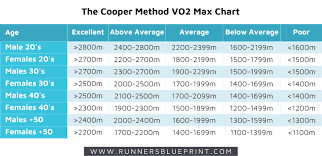

We added some wrinkles here and there based on data we saw along the way, which seemed to especially manifest themselves with athletes that might not have Olympic-level VO2 maxes, whether due to genetics or age (VO2 max measures peak oxygen utilization during exercise, has a strong genetic component, declines with age, and is not highly trainable). You have probably seen me write about a lot of those wrinkles: plenty of fast strides, a higher proportion of short yet controlled intervals, and the heavy use of hill intervals year-round.

But Megan and I both kept hitting the same stumbling block: athletes over age 40 just didn't respond as well as we would like.

So we tried something new. With sub-ultra trail runner Mark Tatum and a few other athletes, we moved almost every workout into the hills, with an astounding number of power hill strides, and at least one session most weeks with short hill intervals. Mark and some others had breakthroughs, seemingly giving a big middle finger to the aging process. For Mark, a few years of training later, it led to an overall win at the Dipsea Race.

That made sense with aging athletes. Hills reduce impact forces and may increase muscle recruitment/mechanical demand (2017 review article in Sports Medicine), and short intervals may counteract natural VO2 max reductions, so they are great for the aging athlete. I've written about that before, as have others. It was nothing new, although maybe the approach was more committed to the bit.

But then something fascinating happened. A few younger athletes that we coached also seemed to have issues where traditional speedwork didn't lead to the expected adaptations. Maybe it was repeated injury cycles without clear explanations, or maybe it was just an unexplained performance reduction. So we tried a similar intervention. While results varied, the hill emphasis had a substantial effect size on results in our team, including preceding a couple national championships.

Now we were intrigued. Is it just the specificity of hills for trail running? Possibly, but we saw similar improvements in some road runners. Could it be an improvement in the VO2 max variable? That's doubtful, since there's little evidence that it can increase much in trained athletes. Lower injury rates? That likely plays a big role, but later we started to see similar results in athletes who rarely got injured. Or, to summarize: The hunter, or a random association of dots?

As we started to incorporate short hills more for all of our athletes, with all different backgrounds, we started to hone in on one primary explanation: the unique neuromuscular and biomechanical demands of mechanical output in running.

Here, mechanical output is shorthand for how aerobic processes interact with the musculoskeletal, biomechanical, and neuromuscular systems to create speed. A thorough explanation of mechanical power output is in this 2018 article in the Journal of Biomechanics, but just think of it as how each stride transmits force, rather than as conveying everything that goes with the technical term. For our purposes, effort level at VO2 max does not refer to the specific physiological measure, but is a general shorthand for high-yet-controlled outputs.

We have seen that if an athlete can improve their output around VO2 max on hills, they can counteract - even reverse - part of the athletic aging process at all distances. The reason that the short hills should lead to more broad-ranging development is that athletes accumulate lots of aerobic work over time, and those lower-level aerobic gains accumulate.

There is nothing new about this concept. For example, Norwegian training principles are so hot right now. Most of the focus is on the high volume of threshold work. But if you look closely at some of the sample weeks, you'll sometimes see a day full of short, fast hills (and that's for young, immensely talented athletes). Similar concepts were rumored to be included in the training of Jake Wightman, World Champion in the 1500 meters. Whether it's Lydiard-based systems from the 1960s and 1970s, Canova-inspired hill sprints, or hybrid approaches, once you start looking, you'll see these elements all over, even for athletes that seem to have almost no genetic or age limitations.

Possible Physiological Explanation

Okay, let's go back to first principles. VO2 max peaks at a young age, and it isn't highly trainable. So how do athletes keep getting faster if their peak oxygen intake is staying flat or declining?

The answer is that their output at VO2 max improves, usually measured as velocity at VO2 max, even as the denominator doesn't improve. The prototypical example is Paula Radcliffe (see this 2006 study in the International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching), whose VO2 max actually decreased from when she was a champion junior athlete, but her running economy (the amount of energy she used to run fast) improved by 15 percent. Those running economy improvements likely come from some mix of lower-level aerobic development leading to more efficient cellular processes of fatigue management, neuromuscular/biomechanical efficiency, and mechanical output. I'm not concerned with how much oxygen an athlete can consume, but what they do with the oxygen they have.

Running economy can be measured across multiple intensity levels. At the intense end of the spectrum, you have velocity at VO2 max (think 10ish minute effort, with variance). More toward the middle is critical velocity or velocity at lactate threshold (~30- to 60-minute effort). At the easier end of the spectrum is velocity at aerobic threshold (2-3+ hours, depending on the athlete). With age, vVO2 goes down first (often in an athlete's mid-20s), followed by vLT (30s or later), then vAeT (which can stay higher for a long time due to the aerobic component). That makes intuitive sense-athletes move up in distance with age by necessity as VO2 max and mechanical output go down, while long-term aerobic development is ongoing.

Side note: there are 10 statements in the preceding paragraphs that are controversial in exercise physiology. Sorry about that. If there's anything I learned from eating a lot of cereal as a kid, it's that if you spot them all and mail proof of purchase to General Mills, they might send a free toy!

Back to it. Our theory is that focusing too heavily on the aerobic side of the running economy equations misses out on the mechanical power side. Yes, VO2 max will decrease with time. But based on what we have seen, the mechanical output associated with VO2 max doesn't need to decrease much at all. And it can even go up very far into an athletic journey!

Mechanical Limitations

Why is that significant for an athlete competing in longer races? Think back to the experienced 60-year old athlete who progresses a bunch with short hill intervals. Their VO2 max number likely can't change much at that point of their athletic journeys, but we think that their mechanical output can. And because mechanical power is a strong performance indicator at all efforts in aging athletes, it doesn't matter that the short hills are non-specific to their race distances. It's the highest-yield stimulus for output, and it pushes back the strongest against the inertia of aging, so they get faster at everything.

If you're 50+, I think that you can take that to the bank. Focus on mechanical output/strength alongside aerobic development, and you'll be rich as hell. Now, let's dive into a more speculative investment.

The hardest logical leap is to take these principles and apply them to younger athletes. Why might they progress even when they aren't limited by mechanical output in the same way?

Our theory: they are limited in that same way, just to a less clear extent. In fact, most of us have some mechanical limitations that are semi-independent of traditional aerobic development.

Talented, elite athletes are the origin point for many training theories, and most of those athletes have few limits associated with vVO2-that's why they're elite in the first place. So they can focus more heavily on the aerobic-input components of speed, plus specific training for their events. But for most of us, mechanical power at the top-end of aerobic capacity is a limiter from when we are young, and it only gets worse with time.

That's one reason we strongly encourage athletes to eat enough, always. Running is a power sport, even if it doesn't always feel that way. And that may add another explanation of why athletes who restrict food almost never improve over time.

Theoretical Implications

Since mechanical output is the true theorized limiter, it may be better to do many of the sessions targeting it on uphills. Flat intervals are fantastic and important at times, but many athletes end up not having the biomechanical and neuromuscular efficiency to translate their aerobic ability into the same output. In our data, an athlete who is not extremely fast (in a road/track sense) will often have a faster grade-adjusted pace on a 2-minute hill interval than pace on a 2-minute flat interval, often by 20-30 seconds per mile. Combined with the higher muscular demand and lower injury risk, output around VO2 max seems to be optimized on hills.

A quick disclaimer: we could easily be confusing cause-and-effect here. Perhaps it's all driven by reduced injury rates and lower soreness levels, creating more consistency over time (or any other explanation you can think of). Going backwards from outcome to mechanism is problematic for 99 reasons, and for the strength of this theory, each and every one of them is a bitch.

But the practical takeaway is this: we have seen that if an athlete can improve their output around VO2 max on hills, they can counteract - even reverse - part of the athletic aging process at all distances. The reason that the short hills should lead to more broad-ranging development is that athletes accumulate lots of aerobic work over time, and those lower-level aerobic gains accumulate.

The aerobic system can continue to improve, but for many athletes, it runs into a ceiling that we think is often set by mechanical output. If you raise that ceiling, there can be a positive feedback cycle where improved mechanical output allows the improving aerobic system to translate to better running economy, which improves mechanical output more, and so on.

The Big Takeaway

Don't let your mechanical output be too strong of a limiter, no matter what training approach you use. For us, that involves three main elements.

First, athletes do hill strides year-round to encourage max power development. That can be as simple as 2 sessions of 4-6 by 20-30 second fast hills in the 2nd half of runs each week, or adding hill strides after a flat workout. Or it can be bigger, dedicated sessions like in the Norwegian training sample weeks. Flat strides can also work for this purpose, particularly for advanced athletes.

Second, athletes periodically do moderately hard hill intervals, as often as weekly for aging or injury-prone athletes, and as little as every 6 weeks in durable track or road athletes (with other sessions being on flat or rolling terrain). Our usual guideline is 12-20 minutes of total intervals, with each interval being 3 minutes or less with run down recovery between them. Simple go-to examples are 16-20 x 45 seconds, 8 x 90 seconds, 6 x 2 minutes, or 5 x 3 minutes, though you can get creative with it based on what's the most fun for you. Mix up the gradient, with the sweet spot being 8%, but it's cool to have fun with steeper or shallower grades, too.

Third, do strength work. We are partial to Mountain Legs and Speed Legs, but anything that improves your strength can work. Just avoid overdoing it.

And remember: this is just one element of our training theory, and our training theory is a grain of sand on the beach of training theories that are out there for free on the internet. Even for us, it interacts with hundreds of other concepts. Listen to your body and do what works for you. Ignore this if you disagree. Send all of your complaints to General Mills.

But don't accept that getting weaker is a foregone conclusion. Aging is inevitable. If you zoom out far enough, slowing down is inevitable, too. But slowing down is not inevitable tomorrow or next year. And I think there's a strong argument that it's not inevitable 5 or 10 years from now either. What do we say to

by Trail Runner Magazine

Login to leave a comment

In order to win his first Dipsea Race 28-year-old Eddie Owens had to study it first.

Two years ago when he moved to San Francisco, Eddie Owens knew nothing about the Dipsea – the country’s oldest trail race – other than what he heard from area runners. It prompted him to visit Marin County to meet Dipsea historian and author Barry Spitz, who has written the quintessential book about historic race, “Dipsea: The Greatest Race.” Owens bought a book from Spitz and said he was curious about the fastest times on record in the race.

Apparently, Owens not only read about them, but he appears hell bent on eclipsing them.

With a time of 48:35 on Sunday – more than a minute faster than anyone else in the field – Owens easily won the 111th Dipsea with a race for the ages. He became the first runner in his 20s to win the historic 7.5-mile foot race from downtown Mill Valley to Stinson Beach since 25-year-old Carl Jensen was the last person to win the event from scratch in 1966.

That feat followed Owens’ astonishing Dipsea debut effort last November when he denied Alex Varner of a 10th Best Time Award by finishing fourth overall with an actual running time of 47:47, the fastest in 26 years.

Owens, who grew up in Brooklyn, N.Y. and attended Princeton University, obviously is a fast learner when it comes to the Dipsea.

“I’ve run races all over the country and all over the world, but there is nothing like the Dipsea,” said Owens, who was a member of Team USA at the 2021 World Mountain and Trailrunning Championships. “I look forward to coming back for many years and decades to come.”