Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

The truth about blood lactate, why lactic acid isn't the enemy you thought it was

Every runner is familiar with that burning sensation that builds up in your legs during a hard run. For years, a buildup of lactic acid was blamed for this unpleasant sensation, and coaches and sports scientists have tried to devise ways to rid your body of this so-called toxin as fast as possible. New research, however, is suggesting we’ve been wrong all along. So if lactic acid isn’t to blame, what is?

What is lactic acid?

When you’re engaging in intense physical activity, your body has to burn sugar (glucose) for energy. When you do this, there are two potential outcomes. If you’re exercising at an intensity that allows your cells to get enough oxygen (think walking, easy jogging or steady-state running), the end product of that sugar-burning is pyruvate. Because you’re working at a low intensity, pyruvate can easily be shuttled back through the same pathway to help produce more energy later on.

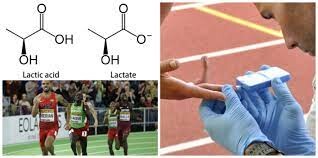

If you’re working at a high intensity (i.e.- sprinting), your body can’t get enough oxygen for that process to work. This is called anaerobic respiration (as opposed to aerobic respiration). In this case, your body converts pyruvate to lactate and hydrogen, collectively known as lactic acid.

The terms lactate and lactic acid are often used interchangeably, but they are not exactly the same thing. As we’ve learned, lactic acid is a combination of lactate and hydrogen. That hydrogen ion lowers the pH of your muscles and makes them more acidic, which is where the burning sensation comes from. This is where lactic acid got a bad rap. In reality, it actually helps your muscles.

Here’s how: when lactic acid leaves your muscles and enters the bloodstream, the hydrogen molecule detaches so you have lactate and hydrogen existing separately. That lactate can then be recycled and used as energy, which your body desperately needs in that moment. Lactate already exists in your body, even when you’re at rest, but most of the time your body clears it out about as fast as it’s created. As your exercise intensity increases and your oxygen needs exceed supply, lactate levels increase, which triggers your heart rate and respiratory rate to increase in order to supply the muscles with the energy they need.

How does this impact performance?

Contrary to what you may have been told, you don’t have to worry about lactic acid buildup. Why? Because your body simply will not allow you to exercise past the point that it can safely clear lactate and hydrogen from your blood. When you hit that limit, no amount of mind over matter will prevent you from slowing down. This is called your lactate threshold.

A very fit individual can only keep running at this intensity for two to three minutes. 800m runners, for example, will use this system primarily during their race and are thus very well-acquainted with hitting their lactic acid threshold (hence why the final 100m of an 800m race are often not pretty). The same goes for the world’s best 1,000m and 1,500m runners.

To recap so far: that burning sensation in your muscles is not caused by lactic acid, but by hydrogen ions (and other chemical byproducts that researchers are still investigating) that are causing your muscles to be more acidic. These ions attach to lactate and enter your bloodstream, ultimately forcing your body to slow down.

How can I reduce lactic acid?

When you exercise at a high intensity, lactate and hydrogen are going to build up in your blood and there’s nothing you can do to prevent that (as we’ve learned, that extra lactate is actually a good thing). What you can do is increase your fitness level so it takes you longer to reach your lactate threshold by improving how efficiently you use oxygen while exercising. This will allow you to train harder for longer before oxygen is no longer sufficiently supplied to your cells, and lactic acid is produced.

How quickly can you recover from lactic acid buildup?

Your body can clear lactic acid fairly quickly once you reduce your exercise intensity. That’s why you can do a series of 400m repeats at a high intensity as long as you rest in between. The harder you run, the longer you will need in between intervals in order to produce the same level of intensity again.

What about DOMS?

For a long time, lactic acid often got blamed for causing the delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) that often follows a bout of intense exercise, but we know now that is not the case. That soreness you feel the day or two after a hard workout is a result of microscopic tears that form in your muscles during intense exercise. Within reason, these tears are a good thing because it’s the healing process that causes muscle growth.

This is why you may have sore legs the day after a long run or race. You likely weren’t running fast enough to reach your lactate threshold, but you sustained enough tiny tears in your muscles to cause some discomfort in the days after your run. As long as this does not persist for more than a few days, this is a sign that you’re building strength and endurance.

The bottom line

Lactate and lactic acid are not your enemies. In fact, they’re there to help you continue to produce energy so you can keep working at a higher intensity. If you train consistently and recover well between sessions, you’ll be able to increase your lactate threshold so you can run faster and farther.

by Brittany Hambleton

Login to leave a comment