Running News Daily

Top Ten Stories of the Week

6/29/2024

These are the top ten stories based on views over the last week.

Fernando Matos wins first race ever held in the tiny village of Monforte da Beira home of the newly open KATA Portugal Retreat

The first ever race in the village of MONFORTE DA BEIRA was held this morning Sunday June 23. 101 participants signed up for the 5k walk/run.

58-year-old Fernando Duarte Matos from Castelo Branco was the overall winner clocking 18:23, a world class time on a course with a few hills. First woman was a KATA (Kenyan Athletics Training Academy) athlete Lucy Murita clocking 22:17. Third was an Anderson Manor Retreat guest Jonathan Suah, an American living in Angola clocked 24:12. In fourth was a naive from the village, Manuel Joao Brito Russo clocking 27:04.

Both of the winners won a trophy, medal and 100 cash euros. There was no entry fee. Over 20 prizes were given out randomly and plenty of food and drink was provided.

The president of the village was the official starter (see photo) after saying some opening remarks. Thanks to our sponsors who were organized by Joao Santos and to Alberto Santos who along with Joao have gotten our Manor in shape for this event. Both participated in the 5k.

“My wife and I (Catherine Cross) met so many nice people today. Welcome to our family. We are looking forward to stage many more races from our Anderson Manor Retreat,” says Bob Anderson.

—- (Portuguese translation)

A primeira corrida na nossa aldeia de MONFORTE DA BEIRA BAIXA foi um evento muito divertido. 101 participantes se inscreveram para nossa caminhada/corrida de 5 km. Fernando Duarte Matos, de Castelo Branco, 58 anos, foi o vencedor geral com 18:23, um tempo de classe mundial num percurso com algumas subidas. A primeira mulher foi a atleta da KATA (Academia de Treinamento de Atletismo do Quênia), Lucy Murita, marcando 22:17. O terceiro foi o convidado do Anderson Manor Retreat, Jonathan Suah, um americano que vive em Angola com cronometragem de 24h12. Em quarto lugar ficou um ingénuo da aldeia, Manuel João Brito Russo, com 27h04. Ambos os vencedores ganharam um troféu, uma medalha e 100 euros em dinheiro. Não houve taxa de entrada. Mais de 20 prêmios foram distribuídos aleatoriamente e muita comida e bebida foram fornecidas.

O presidente da aldeia foi o titular oficial depois de fazer alguns comentários iniciais. Obrigado aos nossos patrocinadores que foram organizados pelo João Santos e ao Alberto Santos que juntamente com o João prepararam o nosso Solar para este evento. Ambos participaram dos 5k. “Minha esposa e eu (Catherine Cross) conhecemos tantas pessoas legais hoje. Bem vindo a nossa familia. Estamos ansiosos para realizar muitas outras corridas em nosso Anderson Manor Retreat”, disse Bob Anderson

(06/23/24) Views: 420Bob Anderson

Which U.S marathon provides the most prize money to the winner? Here are the top seven

Which U.S marathon provides the most prize money to the winner? This question continuously rings in the minds of some youngsters who dream about running and getting the best time in some of these world events or even breaking records. Just like any other sport, races also offer the best prizes to the winners. Running challenges you with self-control and persistence besides the cash injections provided to the top athletes. Here is a ranked list of 7 U.S marathons with the highest prize money, sourced from factual publications.

Which U.S marathon provides the most prize money to the winner?

According to RunRepeat, the highest prize money offering in the United States is the Boston Marathon, which we will explore in-depth in this article. Nevertheless, every year, the country is flooded with innumerable races, most of which gather teams of participants. Most dared to break their personal while others also won the races.

(06/21/24) Views: 163Kenneth Mwenda

Zac Clark is a real runner and has run a 1:32 half marathon

Grandma's Marathon is just hours away! If you are running any of the races, you are likely feeling a few nerves right about now. You are definitely not alone in that.

Here's some excitement to take your mind off it: a reality star is flying in to Minnesota to take part in the race and taking part in the full marathon!

Zac Clark Got The Final Rose

Lovers of 'The Bachelor' franchise will recognize this star! Zac was the winner of The Bachelorette a few seasons back.

A few months ago, I noticed that Zac was posting a lot of videos about running and even mentioned Grandma's Marathon in one of his posts! He shared he'd be running the race, and he is a very serious runner.

On Thursday afternoon (June 20th), Zac posted another video relating to the big race, sharing his stats, his goal time and how he is feeling about the big race right now.

(06/21/24) Views: 131Team USA Track and Field Team for the Paris Olympics

Here’s who will be representing the U.S. in Paris—so far.

The Team USA track and field team will compete at this summer’s Olympic Games in Paris from August 1 to August 11. The first members were named on February 3 at the U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials in Orlando, Florida. The rest of the squad will be determined at the Olympic Track and Field Team Trials in Eugene, Oregon, which are taking place now until June 30.

Here’s who has made Team USA—so far.

100 meters

Women’s team

Sha’Carri Richardson

24 | First place in 10.71 | First Olympics

Melissa Jefferson

23 | Second in 10.80 | First Olympics

Twanisha “TeeTee” Terry

25 | Third in 10.89 | First Olympics

Multi events

Men’s decathlon

Heath Baldwin

23 | First place with 8625 points | First Olympics

Zach Ziemek

31 | Second with 8516 points | Sixth at 2020 Olympics, seventh at 2016 Olympics

Harrison Williams

28 | Third with 8384 points | First Olympics

Shot put

Men’s team

Ryan Crouser

31 | First place in 22.84 meters | Olympic gold medalist in 2016 and 2020

Joe Kovacs

34 | Second in 22.43 meters | Olympic silver medalist in 2016 and 2020

Payton Otterdahl

28 | Third in 22.26 meters | 10th at 2020 Olympics

10,000 meters

Men’s Team

Grant Fisher

27 | First in 27:49.47 | 5th in 10,000 meters at 2020 Olympics

Woody Kincaid

31 | Second in 27:50.74 | 15th in 10,000 meters at 2020 Olympics

Nico Young

21 | Third in 27:52.40 | First Olympics

Marathon

Women’s Team

Fiona O’Keeffe

25 | First in 2:22:10 | First Olympics

Emily Sisson

32 | Second in 2:22:42 | 10th in 10,000 meters at 2020 Olympics

Dakotah Lindwurm

28 | Third in 2:25:31 | First Olympics

Men’s Team

Conner Mantz

27 | First in 2:09:05 | First Olympics

Clayton Young

30 | Second in 2:09:06 | First Olympics

Leonard Korir

37 | Third in 2:09:57 | 14th in 10,000 meters at 2016 Olympics

(06/23/24) Views: 127How to Run in the Heat Like the Pros

Over the past decade, training for the heat has gone from a nice-to-have to an absolute necessity for top runners. Professor Chris Minson is attempting to perfect the science.

After a few pleasant hours sitting in the sun watching the Prefontaine Classic in Eugene, Oregon last month, I headed down into the bowels of Hayward Field for a grueling test for running in the heat. Chris Minson, a professor of human physiology at the University of Oregon, had invited me to try the heat adaptation protocol he has developed for elite athletes from the university and from local pro teams like the Bowerman Track Club. I’ve written about Minson’s research several times, so experiencing the protocol first-hand seemed like a good idea… at the time.

Heat is a big deal in sports these days, and it’s only getting bigger. In recent years we’ve had major events like the world track and field championships in insanely hot places, like Qatar, where the marathons had to be started at midnight. But summertime in Eugene (where the Olympic Track Trials will take place later this month) and Paris (where the Olympics will be held) can also be sizzling. Over the past decade, heat preparation has gone from a nice-to-have to an absolute necessity for top athletes. The details of how to prepare remain more art than science, though, so I was interested to see how Minson put theory into practice.

Back in the 1920s and 1930s, scientists developed the first heat adaptation protocols for workers in South Africa’s sweltering gold mines. The gold standard for heat adaptation evolved from that work: spend at least an hour a day exercising in hot conditions, and after 10 to 14 days you’ll see a bunch of physiological changes. Your core temperature will be lower, your blood volume will be higher, you’ll begin sweating and dilating your blood vessels at a lower temperature threshold, you’ll sweat more, and so on. Put it all together and you’ll be able to stay cooler and run faster in hot conditions.

In fact, there’s even evidence that this type of heat adaptation can make you faster in moderate weather, perhaps as a result of the extra blood plasma. In the lead-up to the 2008 Olympics, Minson was working with American marathoner Dathan Ritzenhein, helping him prepare for the expected hot conditions in Beijing. But he started to worry about what would happen if it wasn’t hot: would all the heat training actually make Ritzenhein slower? Minson and his colleagues ran a study to find out; the results, which they published in 2010, suggested that heat adaptation helps even in cool conditions. That’s the study that really kicked interest in heat training into higher gear.

The problem with the classic approach, though, is that training for an hour in hot, muggy conditions is exhausting. If you’re trying to do a hard workout, you won’t be able to hit the splits you want. If you’re trying to do an easy run, it’s going to take more out of you than it usually does, potentially compromising your next hard workout or raising your risk of overtraining. So how do you get the benefits of heat adaptation without tanking the rest of your training plan?

Minson’s Exercise & Environmental Physiology Lab at the University of Oregon, which he co-runs with fellow physiologist John Halliwill, is located in the Bowerman Sports Science Center, a state-of-the-art facility located under the northwest grandstand of Hayward Field. The key piece of equipment, for my purposes, is an environmental chamber that can take you down to 0 degrees Fahrenheit or up to 22,000 feet of simulated altitude, deliver simulated solar radiation, or blast you with wind. For my heat run, Minson set the dials to 100 degrees Fahrenheit and 40 percent humidity.

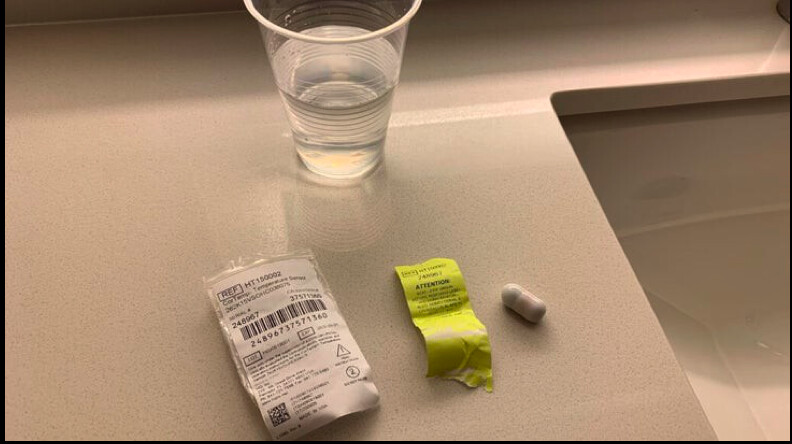

Earlier that day, Minson had given me a thermometer pill to swallow, which would enable him to wirelessly track my core temperature as the run progressed. “I’ll need that back,” he warned me, poker-faced. Fortunately, he was joking.

Before I entered the chamber, I peed in a cup so that Minson could check my urine-specific gravity, the ratio of how dense your urine is compared to water. I clocked in at 1.025, marginally above Minson’s threshold of 1.024 for mild dehydration. I blame it on having spent a few hours sitting in the sun watching the track meet. Then he checked my weight, so that he’d be able to figure out how much I sweated during the test.

When I stepped into the chamber, wearing nothing but shorts and running shoes, I could feel the blast of heat, but it wasn’t too oppressive—like a really hot day at the beach but under an umbrella. I started with a five-minute warm-up at a slow pace, gradually ramping up until I hit 7:30 mile pace. Then the formal protocol started: 30 minutes at that pace.

The pace was self-chosen; Minson refused to tell me the pace I “should” run. The goal was to settle in at an effort that I could comfortably maintain for half-an-hour, and that would get me hot enough to trigger adaptations—a core temperature of about 101 degrees Fahrenheit is thought to be about right—without overshooting and roasting myself. Most of the elite runners he works with end up choosing paces between 7:00 and 8:00 per mile. I slotted myself in the middle of that range—which, let’s be honest, was a dumb thing to do for an aging non-elite runner.

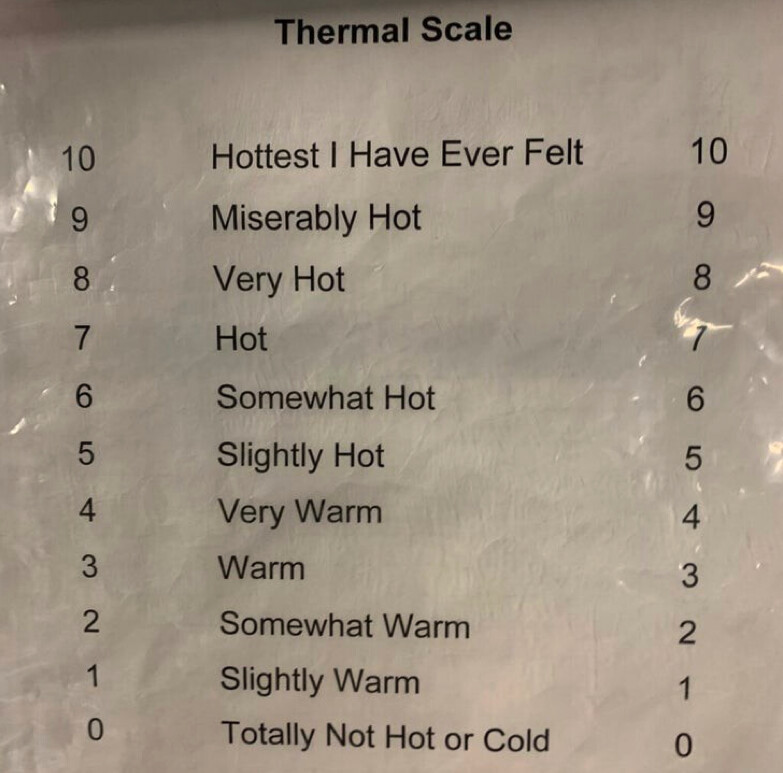

Still, the running itself felt easy to me. Every five minutes or so, Minson had me rate my perceived effort on the Borg scale, which runs from 6 to 20, and also rate how hot I felt. For this, he used his own 0 to 10 thermal scale.

I started out at the effort of 10 (“very light”) and thermal sensation of 3 (“warm”). After 15 minutes, my effort had crept up to 12 (“somewhat hard”), but my thermal sensation was still 3. By this point I was sweating up a storm, watching with interest as my splatters of sweat made a distinctly asymmetric pattern on the treadmill’s control panel. (Clearly I needed to visit the biomechanics lab down the hallway to sort out my stride asymmetries.)

In the latter part of the test, my sweat rate seemed to drop—not a great sign, since it could signal dehydration. My effort topped out at 13, but my thermal sensation crept up to 4 (“very warm”), then 5 (“slightly hot”), then 6 (“somewhat hot”). I still felt under control, though. Then the test ended, and Minson ushered me off the treadmill, into the next room, and into the hot tub, where he asked me to submerge myself up to my neck. The water was set to 104 degrees Fahrenheit, and it was awful. My thermal sensation immediately spiked up to 8 (“very hot”) and then 9 (“miserably hot”).

The odd thing is that the water was basically the same temperature as I was. My core temperature had crept up to 103.2 degrees towards the end of the run, and hit 103.7 shortly afterward. The water wasn’t warming me up in any significant way, but it was robbing me of the superficial perception of coolness that I got from air currents and the evaporation of sweat. It’s a good reminder of why cooling techniques like ice towels or simply dumping water on your head can be valuable: they can dramatically change your perception of how hot you are.

Sitting in that hot tub wasn’t fun, but it’s a key tool for Minson in his efforts to help athletes adapt to heat without interfering with their normal training. It extends the period of thermal stress without trashing their legs. A half-hour easy run, even in hot conditions, isn’t that draining for a well-trained athlete. At least, it’s not supposed to be.

After I’d had a cold shower and chugged a few bottles of sports drink, Minson went over the results with me. The good news is that I hadn’t seemed very bothered by the heat. I’d sweated out 2.2 pounds of fluid, indicating a fairly high sweat rate of around 2 liters per hour. That suggests that I should already be reasonably well equipped to race in warm conditions.

The bad news, though, was that my numbers didn’t make sense. There are no “wrong” answers on a subjective scale, but mine were puzzling. As the test proceeded and my core temperature drifted over 100 degrees, I kept claiming that I felt merely 3-out-of-10 “warm.” That might mean that I’m immune to heat—but more likely, it suggests that I wasn’t properly attuned to my body’s condition. If you’re running in the heat but you’re totally oblivious to how hot you’re getting, that can be a recipe for disaster.

In fact, my subjective numbers were strikingly similar to those of an elite runner Minson has worked with—one who has struggled in the heat. Minson helped the athlete renormalize his heat perception, so that conditions he originally labeled as 3 out of 10 became a more realistic 5 or 6 out of 10.

The ability to accurately gauge how hot you are is important even in training, because those core temperature pills are about $70 a pop. Once athletes have a sense of how hot they should feel during heat adaptation runs, Minson has them judge their half-hour efforts by feel. If they start getting too hot—above 7 on the Minson Scale—they can turn a fan on in the heat chamber to avoid overheating. There’s no rigid schedule of when they do these heat runs: they fit them in around their other training and racing and travel plans.

In practice, of course, most of us don’t have access to a high-tech heat chamber and temperature-controlled hot tub. But studies in recent years have shown that you can use a variety of approaches to get your core temperature up: hot baths, saunas (Minson has one in his lab, and another in his backyard), overdressing during runs. The big-picture takeaway from Minson’s approach is that you can find ways of getting a heat stimulus without disrupting the rest of your training.

To do that, though, you need to be able to gauge when you’re getting overcooked. When I got back to my hotel room that afternoon, I realized that I was feeling wrung out, as if I’d done a long, hard workout rather than a half-hour jog. I’d missed the mark. I decided to take the next day off, and dreamed that night of Minson’s other recent research focus: ice baths.

(06/24/24) Views: 119Outside Online

Mountain Running World Cup opens at Broken Arrow

The 2024 Valsir Mountain Running World Cup kicks off in style on Friday (21) at the Broken Arrow in Palisades Tahoe, California. The season launches with the Broken Arrow VK, a short uphill gold label race, and continues with the 23km Broken Arrow Skyrace, a long gold label race, on Sunday.

With a base elevation of 1890m and stunning peaks all around, including the prominent 2700m Washeshu Peak, Broken Arrow has the perfect credentials for mountain racing.

Many of the athletes from last year’s podiums return. In the women’s VK, last year’s winner Anna Gibson is back to defend her title. The 2023 runner up, Jade Belzberg, also returns, as do Annie Dube and Anna Mae Flynn, who finished fourth and fifth respectively last year. But they will face stiff competition in the form of Allie McLaughlin, the uphill champion at the World Mountain and Trail Running Championships in 2022, and Tabor Hemming.

The men’s VK is also looking incredibly competitive. Darren Thomas, second last year, is back, as is last year’s fifth-place finisher Abraham Hernandez Cruz. Joining them will be some big names, including 2023 World Cup winner Philemon Kiriago, Jim Walmsley, Eli Hemming and Christian Allen.

Many runners are contesting both the VK and the Skyrace, with a day in between to recover. Last year the Skyrace was severely affected by snow, but the snowline is not set to be as low this year.

Memorably McLaughlin battled with Gibson last year, taking the lead and stretching it out to win. McLaughlin is doing the double here, as are Tabor Hemming, who was third last year, and Dube. Janelle Lincks, fourth last year, also returns. Sophia Laukli, a breakout star in last year’s World Cup, also looks to be toeing the line and will be one to watch.

In the men’s Skyrace, defending champion Eli Hemming returns, along with the rest of last year’s podium, Chad Hall and Meikael Beaudoin-Rousseau. Allen, Kipngeno and Thomas will double up, which should make things interesting. To shake things up even further, former world champion Joe Gray is on the start list. Zak Hanna, who finished fourth in last year’s VK, is just taking on the Skyrace this year.

The VK on Friday starts on the valley floor and climbs its way up 914m over 4.8km to the summit of Washeshu Peak at 2708m. Despite some changes to the course this year, along the way it still takes in some brutally steep terrain, leading up to the iconic Headwall Ridge and the ‘stairway to heaven’ bolted ladder to the summit of Washeshu Peak. Runners will experience steep rock slabs, snow and scree, which is guaranteed to deliver an exciting race.

On Sunday the Broken Arrow Skyrace is held on a loop which climbs 1533m over the course of 23km. It starts in Palisades Tahoe Village and most of the race takes place above the tree line on technical and demanding trails. Runners will be treated to views of Granite Chief Wilderness and they will experience Emigrant Pass, KT-22 and, like the VK runners, the ‘stairway to heaven’ ladder to Washeshu Peak.

The Broken Arrow offers the first two of 12 races that form part of the Valsir Mountain Running World Cup in 2024. The season closes with the World Cup Final Val Bregaglia Trail on 13 October. There will be a livestream of the Broken Arrow action available on the event website.

(06/23/24) Views: 119

Canadian ultra-star Priscilla Forgie is ready to crush Western States 100

Edmonton’s Priscilla Forgie is blazing a trail in Canadian ultrarunning, and she’s primed for one of the biggest races of the year—Western States 100-miler, set for June 29th. Having finished as the top Canadian in last year’s race (eighth place overall), Forgie is back, even more prepared and ready to tackle the course in Auburn, California. Her secret? Three specific strategies that can benefit any runner aiming to elevate their performance.

Forgie has dominated numerous races in recent years, with victories at the Squamish 50-mile and 50/50, a second-place finish at the Canyons Endurance Run, and an overall win (with a course record) at the Near Death Marathon. Here’s how she’s preparing for Western States 100 and how you can apply her methods to your own training.

“Last year, I was told I looked better at the 100K mark than at 50K! The elevation in the high country kicked my butt, so I arrived a bit earlier this time around to adjust,” Forgie shares.

Altitude can be a game-changer in endurance races. If your race is at a higher elevation than you’re used to, plan to arrive several days or even weeks early if at all possible, to give your body time to acclimate. If you’re unable to spend extra days at altitude, make sure to incorporate lots of elevation gain into your training runs and consider practising breathing techniques to help reduce respiratory fatigue.

(06/24/24) Views: 117Running Magazine

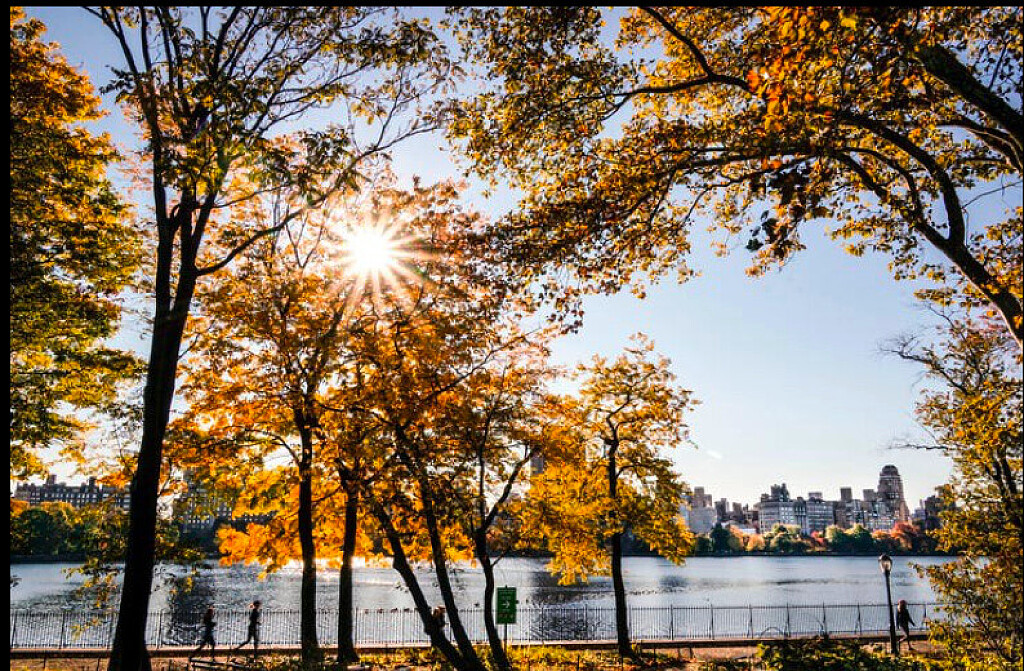

Reasons to Love Running in New York City

This highly-runnable city has a variety of events, routes, and resources that draw in an active community of runnersThere’s no place like New York City, especially if you’re a runner. Whether you’ve raced multiple marathons or you prefer a mellower pace, you’ll always have a new route to explore, a run club to meet up with, or an event to sign up for.

“Any kind of running experience you want to have, you can have here,” says Dave Hashim, a New York City–based photographer who recently completed the Perimeter Project, where he ran around the borders of all five boroughs.

For Caitlin Papageorge, president of North Brooklyn Runners, part of the city’s love affair with running stems from the way its citizens normally get around.

“New York is such a pedestrian city,” she says. “I think for that very reason, it sets New York up really well for a great running scene.”Ready to experience what New York has to offer? Here’s your quickest path to connection with the city’s broad and diverse running community.

Central Park: No trip to New York is complete without a jog through Central Park. Hashim recommends following the main paved path for a seven-mile loop, but make sure to lap the Harlem Meer, in the park’s northeast corner—it’s an often overlooked but especially beautiful area.

Hudson River Greenway: Stretching 12.5 miles from Battery Park all the way up to Inwood Hill Park at the northern tip of Manhattan, the Hudson River Greenway offers superb views of the Hudson River and nearby parks all along its length.

Roosevelt Island: Get off the beaten path with a four-mile run around Roosevelt Island in the East River. Both Hashim and Papageorge recommend it for its quiet atmosphere (there’s very little traffic), interesting architecture (like an abandoned smallpox hospital), and panoramic vistas of the Manhattan skyline.

McCarren Park Track: Brooklyn’s McCarren Park is a popular spot for runners thanks to its public track. Head here for a sprint workout or a warm-up lap before a longer run—just keep an eye out for obstacles like wayward soccer balls or the occasional ice cream cart cruising around in lane one.New Balance 5th Avenue Mile: The 5th Avenue Mile proves that short distances can attract stiff competition. Elite sprinters battle here each year, and the course itself is a star: Competitors race from 80th Street to 60th Street, passing distinguished institutions like the Frick Collection art museum.

United Airlines NYC Half: This 13.1-mile spring classic has become a destination race for good reason, providing a scenic tour of two boroughs packed with iconic landmarks. Join 25,000 racers on closed NYC streets, from a Brooklyn start, across the Manhattan Bridge, heading up through Times Square, to a home stretch in Central Park.

Al Gordon 4-Miler: This race takes place in Prospect Park, Brooklyn’s answer to Central Park, and honors Al Gordon, a New Yorker who began running marathons in his 80s. While the distance is short, the course showcases the park’s beautiful scenery and includes some hilly terrain for an extra challenge. “I just love being there,” says Papageorge. “It’s underrated.”No More Lonely Runs: Looking for someone to run with? Take a tip from Mallory Kilmer, a seasoned marathoner who started this club to help runners of all experience levels find community in the sport. The beginner-friendly groups gather every Saturday morning.

Endorphins: This nationwide running group has a strong presence in New York City. While the group runs every Monday are a big draw, joining Endorphins also gets you access to online resources like Q&As with running coaches and physical therapists.

Asian Trail Mix: This club’s mission is twofold: Increase AAPI representation in running and get New Yorkers onto the dirt. If you’re itching for trails, join one of the club’s all-are-welcome group runs, which explore the wealth of wilderness areas just a short train ride outside the city.

Front Runners New York: Front Runners is where New York’s LGBTQ+ and running communities overlap, and the group creates a positive, inclusive atmosphere at its weekly Fun Runs. If you become a member, you can also join the group’s coached workouts and triathlon training sessions.

Almost Friday Run Club: Why not start the weekend a little early? Almost Friday is the group to do it with: this friendly club meets every Thursday morning on the Hudson River Greenway for a chill run by the water. It’s the perfect midweek pick-me-up.

New Balance Upper West Side: New Balance’s Upper West Side location—just a few strides from Central Park—will be your go-to spot for running shoes, gear, and advice. Key highlight: The store is equipped with a 3D foot scanner to help you get the perfect fit in your next pair of shoes.

(06/22/24) Views: 111Outside Online

After Double Knee Surgery, This Runner is Poised to Make Team USA for the Paris Olympics

Val Constien has surmounted obstacles along every step of her career—including a devastating knee injury just 13 months ago. Now the 28-year-old is a favorite to make her second Olympic team in the 3,000-meter steeplechase heading into the U.S. Track and Field Olympic Trials.

Val Constien started 2023 in the best shape of her life. She had been an Olympian in the 3,000-meter steeplechase at the Tokyo Olympics. And yet, she had no professional sponsorships.

Constien, then 26, had spent the several years after graduating from the University of Colorado in 2019 continuing to train for the steeplechase under her college coaches while working a full-time job mostly because she loved it, and partly because she was betting on herself that she could continue to progress to a higher level.

While studying environmental engineering at CU, Constien twice earned All-American honors in the steeplechase and helped the Buffaloes win a NCAA Division I national championship in cross country. She then finished 12th in the steeplechase at the Tokyo Olympics in 2021. And yet the Boulder, Colorado-based runner hadn’t been able to attract a sponsorship deal from a shoe and apparel brand. She squeezed her workouts in before work, paid for her travel to races, and remained determined and hopeful.

But then, after winning a U.S. indoor title in the flat 3,000 meters in early 2023, she caught the attention of Nike, which signed her to a deal that would lead into the 2024 Olympic year. Finally, it was the break she’d be hoping for.

However, less than three weeks after signing the contract, while running the steeplechase in a high-level Diamond League meet in Doha, Qatar, Constien landed awkwardly on her right leg early in the race and immediately knew something was wrong. She could be seen visibly mouthing “Oh no!” on the livestream, as she hobbled to the side of the track out of the race.

It was a worst case scenario: a torn ACL in her right knee. That meant surgery and a long road back to running fast again.

“That was awful,” said Kyle Lewis, her boyfriend who was watching the race online from Boulder. “The doctors over there initially told her they thought it was a sprain, but she came home and two days later she got an MRI and found out that it was a completely torn ACL, and she was obviously very upset. That was only a couple of weeks after she signed the Nike deal. But that’s just kind of been like with Val’s whole career. Nothing has ever come easy to that girl.”

How Constien, now 28, returned to top form a year later to become one of the top contenders to make Team USA in the steeplechase heading into the June 21-30 U.S. Olympic Trials in Eugene, Oregon—her preliminary race on June 24 will be only 398 days after her knee was surgically repaired—is a testament to the grit and confidence Constien possesses.

“It’s all just an extension of how tough I am and how willing I am to make hard decisions, and how badly I want it,” Constien said. “I love running. If I didn’t love running this much, I would’ve quit a long time ago.”

Constien had surgery last May 2023 at the Steadman Clinic in Vail, Colorado, not far from where she grew up. But that also presented a challenging twist.

One of the most popular types of ACL reconstructions for athletes is called a patella tendon graft, in which the doctor cuts off pieces of bone from the patient’s tibia and patella and several strands of the patella tendon and uses those materials to replace the ACL. Usually those grafts are harvested from the same injured leg, but doctors determined Constien’s right patella had a bone bruise on it and wasn’t healthy enough to use. So instead, they grafted the replacement materials from her left leg. That meant undergoing surgery on both legs, rendering her recovery even more difficult.

For the first two weeks after surgery, she couldn’t stand up or sit down on her own. She had trouble moving around and even had to sit down to take a shower. It took a full month until she started to get comfortable enough to go on short, easy walks and start to regain her mobility.

“The first month post-op was really devastating,” she said. “I was in a lot of pain, and it was hot and I was uncomfortable. I’m glad he did it the way he did it, but it was a really, really challenging recovery.”

All the while, though, Constien never stopped thinking about getting back to racing and the prospect of what 2024 might hold. That’s what helped her make a huge mental shift two weeks after the surgery and refocus all of her energy into returning to peak form and chasing another Olympic berth.

That was obviously easier said than done, but Constien has grown used to working hard and battling adversity. Her college career had been disrupted by injuries and slow progress. She was overlooked by brands when she got out of school in 2019 and again in 2021 after she slashed 7 seconds off her personal best time to finish third at the U.S. Olympic Trials and earn a spot in the Tokyo Olympics. And after she ran two strong races in Tokyo—the first international races of her career—to make it to the final and place 12th overall.

Even when she’s been overlooked or discounted, Constien has always believed in her potential. And that’s why, after a year of hyper-focused dedication, she’s on the brink of making it back onto Team USA to compete in this summer’s Paris Olympics.

“I’ve told her many times, no matter what happens after this point, what a comeback it’s already been,” Lewis said. “But what’s amazing about her is that, after that initial rough part, when she wasn’t able to walk, she just did an incredible job of compartmentalizing and being focused. I never saw her get sad or upset. She was always just super clinical about everything and really happy. It’s been incredible to watch.”

All last summer and fall, she continued building strength and began rejuvenating her aerobic strength—running more miles, getting stronger and getting faster. And that was amid working full-time doing quality assurance work for Stryd, a Boulder-based company that makes a wearable device to monitor running power and gait metrics. Heather Burroughs and Mark Wetmore, who have coached Constien since 2014, knew she had made considerable progress. But it wasn’t until early February that they began to realize the magnitude of her comeback.

“There was a point this winter, when she wasn’t running races, yet but she had some workouts that impressed me,” Burroughs said. “I wasn’t really worried about her ability to get fit enough the last four months, but it was whether her knee could handle the steeple work, especially the water jump.”

They never discussed that—because there was no point—and Constien went boldly into the outdoor season with her goal of breaking the 9:41.00 Olympic Trials qualifying standard. She started training outdoors in March and started her season by running a strong 1500-meter race on April 12 near Los Angeles (she won her heat in 4:12.27). But it wasn’t until May 11—roughly a year after she blew out her knee in Doha—that she ran her first steeple race.

At the Sound Running Track Fest, she ran patiently (with a smile on her face most of the way) just off the lead for the seven-and-a-half-lap race. She then unleashed an explosive closing kick to outrun Kaylee Mitchell down the homestretch and win in 9:27.22—securing her place in the Olympic Trials. That got her an invitation to the Prefontaine Classic, an international Diamond League meet on May 25 in Eugene, where she ran the best race of her life and finished fifth—and first American—in a new personal best of 9:14.29.

That put Constien at No. 7 on the all-time U.S. list. But more importantly, Constien closed hard after Uganda’s Peruth Chemutai had split the field apart en route to a world-leading 8:55.09, the sixth-fastest time in history.

“I’m more impressed by her comeback than she is, and it’s because I think she expected it,” Burroughs said. “It’s not that I didn’t expect it, but it was still improbable. But even now that she’s come back, she’s not impressed with herself at all. After the Prefontaine meet, I texted her about the race, and I got a five-word response—‘Let’s get back to work’—just very businesslike. She’s just dialed in and, to me, that says, ‘My big goal is yet to come.’”

For the last decade-plus, Emma Coburn and Courtney Freirichs have dominated the U.S. women’s steeplechase. They both suffered season-ending injuries this spring (broken ankle and torn ACL, respectively). Their absence leaves the event wide open for the likes of Constein, who is ranked second, and Krissy Gear, who enters the meet at the top seed (9:12.81) and as the defending national champion. But rising stars Courtney Wayment (9:14.48), Olivia Markezich (9:17:36), Gabrielle Jennings (9:18:03), and Kaylee Mitchell (9:21.00) are among several fast, young runners eager to battle for a spot on the Olympic team.

Constien knows she has two just goals to execute: run smart and fast enough to qualify for the finals on June 27, and then do whatever it takes to finish among the top three in that race.

Burroughs believes she’s as fit and as strong as she’s ever been, much improved since 2022, when she finished a disappointing eighth at the U.S. championships (9:42.96) while recovering from Covid. In fact, she’s even much better than her breakout year in 2021.

Over the past several weeks in Boulder, Constien has sharpened her fitness, including a final tuneup on June 12: a robust tempo run on the track with two hurdles per lap, which was preceded and followed by several fast 200-meter repeats. She’s also sharpened her perspective.

“There were definitely some dark times where I doubted myself and I doubted the process,” Constien said. “But I kind of just had to lock those thoughts away and just try to focus on the positive. And it’s really paid off.

“I never gave up when I didn’t have a sponsor and had to figure it all out on my own,” she added. “So tearing my ACL, yeah, that really sucks. That was really, really hard. But a part of me was like, ‘I’ve already done the hardest thing ever’ just by staying in the sport on my own. I look at it like, ‘I am the toughest person out here regardless of that ACL.’”

(06/22/24) Views: 106Olympic 800m champion Athing Mu out of Paris 2024 after falling at US trials

Olympic champion Athing Mu’s hopes for a repeat came crashing down on the first lap of the 800m final at the US Olympic trials on Monday.

Racing in the middle of the pack, Mu tangled with a bunched group of runners and went crashing to the ground before rolling on to her back. She got back to her feet and finished the race, but was more than 22 seconds behind the winner, Nia Akins, who took first place with a time of 1 minute 57.36 seconds.

The 22-year-old Mu was choking back tears as she headed quickly off the track and through the tunnel after the race. She did not immediately come through the media area for interviews.

The Olympic trials were Mu’s first meet of the year after dealing with injuries all season. She looked to be in good form in her first two rounds, but was out of the running in the final before the first 200m.

It was Exhibit A of the unforgiving format of the US trials, where the top three finishers make the Olympic team and past performances mean nothing.

“I’ve coached it,said told The Associated Press. “And here’s another indication that regardless of how good we are, we can leave some better athletes home than other countries have. It’s part of our American way.”

Kersee said Mu was clipped from behind and that a protest had been lodged. USA Track and Field did not immediately respond to queries about the status of the protest. Kersee said Mu got spiked, had track burns and hurt her ankle.

“She’s going to be licking her wounds for a couple of days,” Kersee said.

Mu could still go to Paris as part of the US relay pool; she was a key part of America’s gold-medal win in the 4x400m three years ago in Tokyo.After winning college, national, world and Olympic championships all before turning 21, Mu won a bronze medal at worlds last year and, afterward, conceded she needed a break from the pressure and demands that come with being tagged as one of track’s new stars.

“For sure, I wasn’t really happy to be there,” she told the Guardian when asked about her 2023 season. “Mentally, I just wasn’t really there. I just wasn’t present. I didn’t appreciate being there. I didn’t really enjoy what was happening to me.”

She has dominated the 800m thanks, in part, to a long, loping stride, and that may be what cost her in a race in which she came in as the favorite. Mu was racing on the outside in a tightly bunched pack and looked to be veering to her left toward Juliette Whitaker when she tripped, leaving three runners behind her flailing as they jumped over her.Mu is hardly the first athlete to suffer such misfortune. One of the more memorable and heartbreaking moments came eight years ago in the same event, when Alysia Montano, looking to return to the Olympics, was tripped up in the homestretch and stayed down on the track crying.

There was drama elsewhere on a busy night that included six finals.

The women’s 5000m came down to a 0.02sec difference with Elle St Pierre finishing in 14:40.34, just ahead of Elise Cranny. Both are going to the Olympics.

Vashti Cunningham, who had a combined 13 straight US indoor and outdoor titles coming into the week, won a jump-off for third to make her third Olympic team.

Meanwhile, 16-year-old Quincy Wilson finished sixth in the 400m final with a time of 44.94, his third sub-45 race in three tries at the trials.

Now, he will wait to see if the US track team calls on him to be part of the relay pool.

“All I know is I gave everything I had,” he said. “I can’t be too disappointed. I’m 16, and I’m running grown-man times.”

(06/25/24) Views: 99