Running News Daily

Top Ten Stories of the Week

10/14/2023

These are the top ten stories based on views over the last week.

Molly Seidel Stunned the World (and Herself) with Olympic Bronze in Tokyo. Then Life Went Sideways.

She stunned the world (and herself) with Olympic bronze in Tokyo. Then life went sideways. How America’s unexpected marathon phenom is getting her body—and brain—back on track.

On a clear December night in 2019, Molly Seidel was at a rooftop holiday party in Boston, wearing a black velvet dress, doing what a lot of 25-year-olds do: passing a joint between friends, wondering what she was doing with her life.

“You should run the Olympic Trials,” her sister, Izzy, said, as smoke swirled in the chilly air atop The Trackhouse, a retail shop and community hub on Newbury Street operated by the running brand Tracksmith. “That would be hilarious if you did that as your first marathon.”

Molly, an elite 10K racer who’d spent much of 2019 injured, looked out at the city lights, and laughed. Why the hell not? She’d just qualified for the trials, winning the San Antonio Half with a time of 1:10:27. (“The shock of the century,” as she’d put it.) True, 13.1 miles wasn’t 26.2—but running a marathon was something to do. If only because she never had before.

A four-time NCAA track and cross-country champion at The University of Notre Dame in Indiana, Molly had moved to Boston in 2017, where she’d worked three jobs to supplement her fourth: running for Saucony’s Freedom Track Club. The $34,000 a year that Saucony paid her (pre-tax, sans medical) didn’t go far in one of America’s most expensive cities. Chasing kids around as a babysitter, driving around as an Instacart shopper, and standing around eight hours a day as a barista—when you’re running 20 miles a day—wasn’t ideal. But whatever, she had compression socks. And she was downing free coffee and paying rent, flying to Flagstaff, Arizona, every so often for altitude camps, and having a good time. Doing what she loved. The only thing she’s ever wanted to do since she was a freckly fifth-grader in small-town Wisconsin clocking a six-minute mile in gym class.

“I was hustling, and I loved it. It was such a fun, cool time of my life,” she says, summarizing her 20s. Staring into Molly’s steely brown eyes, listening to her speak with such clarity and conviction about her struggles since, it’s easy to forget: She is still only 29.

After Molly had hip surgery on her birthday in July 2018, her doctors gave her a 50/50 chance of running professionally again. By summer 2019, she’d parted ways with FTC, which left her sobbing on the banks of the Charles River, getting eaten alive by mosquitoes and uncertainty. Her biggest achievement lately had been being named #2 Top Instacart Shopper (in Flagstaff; Boston was big-time).

The day after that rooftop party, Molly asked her friend and former FTC teammate Jon Green, who she’d newly anointed as her coach: “Think I should run the marathon trials?” Sure, he shrugged. Nothing to lose. Maybe it’d help her train for the 10K, her best shot—they both thought—at making a U.S. Olympic team.

“I’m going to get my ass kicked six ways to Sunday!” she told the host of the podcast Running On Om six weeks before the trials in Atlanta.

Instead, on February 29, 2020, she kicked some herself. Pushing past 448 of the fastest, most-experienced women marathoners in the country, coming in second with a 2:27:31, earning more in prize money ($60,000) than she had in two years of racing—and a spot on the U.S. trio for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, along with Kenyan-born superstars Aliphine Tuliamuk and Sally Kipyego. “I don’t know what’s happening right now!” Molly kept saying into TV cameras, wrapped in an American flag, as stunned as a lottery winner.

Saucony who? Puma came calling. Along with something Molly hadn’t anticipated: the spotlight. An onslaught of social media followers. And two weeks later, a global pandemic and lockdown—and all the anxiety and isolation that came with it. She was drowning, and she hadn’t even landed in Tokyo yet.

The 2020 Olympics, as we all know, were postponed to 2021. An emotional burden but a physical boon for Molly, in that it allowed her to get in a second marathon. In London, she finished two minutes faster than her debut. When the Olympics finally rolled around, she was ready.

Before the race, Molly says, “I was thinking: ‘Once I cross the starting line, I get to call myself an Olympian and that’s a win for the day.’”

But then she crossed the finish line—with a finger-kiss to the sky and a guttural Yesss!—in third place with a 2:27:46, just 26 seconds behind first (Kenya’s Peres Jepchirchir). And realized: She gets to call herself an Olympic medalist forever. Only the third American woman to ever earn one in the marathon.

Lots of kids have fleeting hopes of making it to the Olympics. I remember thinking I could be Mary Lou Retton. Maybe FloJo, with shorter fingernails. Then I decided I’d rather be Madonna or president of the United States and promptly forgot about it. But Molly held tight to her Olympic aspirations. She still has a poster she made in 2004, with stickers and a snapshot of her smiley 10-year-old self, to prove it. “I wish I will make it into the Olympics and win a gold medal,” she wrote, and signed it: Molly Seidel, the “y” looping back to underline her name. In case there was any doubt as to who, specifically, would be winning the medal.

Molly grew up in Nashotah, Wisconsin, and is the eldest of three. Her sister and brother, younger by not quite two years, are twins. Izzy is a running influencer and corporate content creator for companies like Peloton; and Fritz favors Formula 1 racing and weightlifting and works for the family’s leather-tanning business. The family was active, sporty. Dad, Fritz Sr., was a ski racer in college; Mom, Anne, a cheerleader. You can tell. Watching clips of Molly’s mom and dad watching the Olympic race from their backyard patio, jumping up and down, tears streaming, is the kind of life-affirming moment you wish you could bottle. “I’m in shock. I’m in disbelief,” Molly says into the mic, beaming. “I just wanted to come out today and I don’t know…stick my nose where it didn’t belong and see what I could come away with. And I guess that’s a medal.” When the interviewer holds up her family on FaceTime, Molly breaks down. “We did it,” she says into the screen between sobs and smiles. “Please drink a beer for me.

Molly hasn’t always been unabashedly herself, even when everyone thought she was. A compartmentalizer to the core, she spent most of her life hiding a huge part of it: anorexia, bulimia, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, debilitating depression.

It started around age 11, when she learned to disguise OCD tendencies, like compulsively knocking on wood, silently reciting prayers “to avoid God getting mad at me,” she says. “It was a whole thing.” She says her parents were aware of the behaviors, but saw them more as odd little habits. “They had no reason to suspect anything. I was very high-functioning,” she says. “They didn’t realize that it was literally taking over my life.”

She wasn’t officially diagnosed with OCD until her freshman year of college, when she saw a therapist for the first time. At Notre Dame, disordered eating took hold, quietly yet visibly, as it does for up to 62 percent of female college athletes, according to the National Eating Disorders Association. As recently as the Tokyo Olympics, she was making herself throw up in the airport bathroom, mere days before taking the podium. Molly hesitates to share that detail; she fears a girl might read this and interpret it as behavior to model. “Having been in that place as a younger athlete, I know I would have,” she says. But she also understands: Most people just don’t get how unrelenting eating disorders can be.

In February 2022, she finally received a diagnosis of the root cause for all of it: ADHD. About being diagnosed, she says, “It made me feel really good, like [I don’t have] a million different disorders. I have a disorder that manifests itself in a lot of different symptoms.”

She waited to try Adderall until after the Boston Marathon in April, only to drop out at mile 16 due to a hip impingement. Initially, the meds made her feel fantastic. Focused. Free. Until she realized Adderall hurt more than it helped. She couldn’t sleep, couldn’t eat, lost too much weight. Within weeks, she devolved. “The eating disorder came roaring back,” she says, referring to it, as she often does, as its own entity, something that exists outside of herself. That ruthlessly takes control over her very need for control. “I almost think of it as an alter ego,” she explains. “Adderall was just bubblegum in the dam,” as she puts it. She ditched the drug, and her life—professionally, physically—unraveled.

In July 2022, heading into the World Championships, she bombed the mental health screening, answering the questions with brutal honesty. She’d been texting Keira D’Amato weeks prior. “Yo girl, things are pretty bad right now. Get ready…” Sobbing on the sidewalk in Eugene, Oregon, she texted D’Amato again. And the USATF made it official: D’Amato would take her spot on the team. Then Molly did what she’d been “putting off and putting off”— checked herself into eating disorder treatment for the second time since 2016, an outpatient program in Salt Lake City, where her new boyfriend was living at the time.

Somehow (see: expert compartmentalizer) mid-meltdown, in February 2022, she had met an amateur ultrarunner named Matt, on Hinge. A quiet, lanky photographer, he didn’t totally get what she did. “I didn’t understand the gravity of it,” he tells me. “I was like, Oh she’s a pro runner, that’s cool. I didn’t realize she was, like, the pro runner!”

Going back to treatment “was pretty terrible,” she says. At least she could stay with Matt. Hardly a honeymoon phase, but the new relationship held promise. “I laid it all out there,” says Molly. “And he was still here for it, for all the messiness. It was really meaningful.” And a mental shift. “He doesn’t see me as just Molly the Runner.”

Almost a year later, on a freezing April evening in Flagstaff, Molly is racing around Whole Foods, palming a head of cabbage, grabbing a thing of hummus, hunting for deals even though she doesn’t need to anymore.

“It’s all about speed, efficiency, and quality,” she says, explaining the secret to her earlier Instacart success. She checks the expiration date on a container of goat cheese and beelines for the butcher counter, scans it faster than an Epson DS3000, though not without calculation, and requests two tomato-and-mozzarella-stuffed chicken breasts. Then she darts over to the beverage aisle in her marshmallow-y Puma slip-ons that Matt custom-painted with orange poppies. She grabs a case of La Croix (tangerine), then zips to the checkout. We’re in and out in under 15 minutes and 50 bucks, nothing bruised or broken.

Other than her body. Let’s just say: If Molly were an avocado or a carton of eggs, she probably wouldn’t pass her own sniff test. The week we meet, she is just coming off a month of no running. Not a single mile. She’s used to running twice a day, 130 miles a week. No wonder she’s spraying her kitchen counter with Mrs. Meyer’s and scrubbing the stovetop within minutes of welcoming me into her new home.

The place, which she shares with Matt and his Australian border collie, Rye, has a post-college flophouse feel: a deep L-shaped couch draped in Pendleton blankets, a bar cluttered with bottles of discount wine, a floor lamp leaning like the Tower of Pisa next to a chew toy in the shape of a ranch dressing bottle. Scattered about, though, are reminders that an elite runner sleeps here. Or at least tries to. (“Pro runner by day, mild insomniac by night” reads the bio on her rarely used account on what used to be Twitter.) There’s a stick of Chafe Safe on the coffee table. Shalane Flanagan’s cookbooks on the counter. And framed in glass, propped on the office floor: Molly’s Olympic kit—blue racing briefs with the Nike Swoosh, a USA singlet, her once-sweat-drenched American flag, folded in a triangle. “I’m not sure where to hang it,” she says. “It seems a little ostentatious to have it in the living room.”

With long brown curls and a round, freckly face, Molly has an aw-shucks look so innocent that it’s hard, at first, to perceive her struggles. Flat-out ask her, though—How are you even functioning?—and she’ll tell you: “I’m an absolute wreck. There’s no worse feeling than being a pro runner who can’t run. You just feel fucking useless.” Tidying a stack of newspapers, she adds, “Don’t worry, I’ve had therapy today.”

She’s watched every show. (Save Ted Lasso, “too sickly sweet.”) Listened to every podcast. (Armchair Expert is a favorite.) She’s got nothing else to do but PT and go easy on the ElliptiGo in the garage, onto which she’s rigged a wooden bookstand, currently clipped with A History of God: The 4,000 Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. “I don’t read running books,” she says. “I need something different.”

Like most runners—even the most amateur among us—running, moving, is what keeps her sane. “What about swimming? Can you at least swim?” I ask, projecting my own desperation if I were in her size 8.5 shoes. “I fucking hate swimming,” says Molly. Walking? “Oh, yeah, I can go on walks. Another. Long. Walk.”

The only thing she has on her schedule this week is pumping up a local middle school track team before their big meet. The invitation boosted her spirits. “Should I just memorize Miracle on Ice?” she says, laughing. “No, I know, I’ll do Independence Day.”

Injuries are nothing new for Molly. Par for the course for any professional athlete. But especially for women, like her, who lack bone density—and have since high school, when, according to a study in the Orthopedic Journal of Sports Medicine, nearly half of female runners experience period loss. Osteoporosis and its precursor, osteopenia, are rampant in female runners, leading to ongoing issues that threaten not just their college and professional running careers, but their lives.

Still, Molly admits, laughing: She’s especially accident-prone. I ask her to list every scratch she’s ever had, which takes her 10 minutes, and goes all the way back to babyhood, when she banged her head against the bathtub spout. There was a cracked spine from a sledding incident in 8th grade, a broken collarbone from a ski race in high school, shredded knee cartilage in college when a driver hit her while she was riding a bike. “Ribs are constantly breaking,” she says. In 2021, two snapped, and refused to heal in time for the New York City Marathon. No biggie. She ran through the pain with a 2:24:42, besting Deena Kastor’s 2008 time by more than a minute and setting the American course record.

Molly’s latest injury? Glute tear. “Literally a gigantic pain in the ass,” she posted on Instagram in March. Inside, Molly was devastated. Pulling out of the Nagoya Marathon—the night before her 6:45 a.m. flight to Japan, no less—was not in the plan. The plan, according to Coach Green, had been simple. It always is. If the two of them even have one. “Just to have fun and be consistent.” And get a marathon or two in before the Olympic Trials in February 2024.

She’d been finally—finally—fit on all fronts; ready to race, ready to return. She needed Nagoya. And then, nothing. “It feels like I’m back at the bottom of the well,” says Molly, driving home from Whole Foods in her Toyota 4Runner. “This last year-and-a-half has been so difficult. It’s just been a lot of doubt. How do I approach this, as someone who has now won a medal? Like, man, am I even relevant in this sport anymore?” She pops a piece of gum in her mouth. I wait for her to offer me some, because that’s what you do with gum, but she doesn’t. She’s so in her head. “It’s hard when you’re in the thick of it, you know, to figure out: Why the fuck do I keep doing this? When it just breaks my heart over and over and over again?”

We pull into her driveway. “I was prepared for the low period after Tokyo,” she says. “But this has been much longer and lower than I expected.”

The curse of making it to the Olympics, let alone coming back with a medal: expectations. Molly’s own were high. “I think I thought, after the Olympics, if I win a medal, then I will be fixed, it will fix everything.” Instead, in a way, it made everything worse.

That’s the problem that has plagued Molly for most of her running career: Her triumphs and troubles intermingle, like thunder and lightning. Which, by the way, she has been struck by. (A minor backyard-grill, summer-thunderstorm incident. She was fine.)

The next morning in Flagstaff, Molly’s feeling like she can run a mile, maybe two. It’s snowing, though, and she doesn’t want to risk the slippery track, so we meet at Campbell Mesa Trails. She loops a band around the back of her truck to stretch and sends me off into the trees to run alone while she does a couple of laps on the street.

Molly leaves for an acupuncture appointment, and we reunite later at Single Speed Coffee (“the best coffee in Flagstaff,” promises the ex-barista who drinks up to three cups a day). We curl up on a couch like it’s her living room, and she talks as freely—and as loudly—as if it was. Does she realize everyone can hear her? She doesn’t care. I guess that’s what happens when you’ve grown so comfortable sharing—in therapy, on podcasts, in a three-part video series on ADHD for WebMD—you just…share. Loud and proud.

Mental illness is so insidious, says Molly. “It’s not always this Sylvia Plath stick-my-head-in-a-fucking-oven thing, where you’re sad all the time,” she says. “High-functioning depressed people live normal successful lives. I can be having the happiest moment, and three days later I’m in a total downward spiral.” It’s something you never recover from, she says, but you learn to manage.

“I’m this incredibly flawed person who struggles so much. I think: How could I have won this thing when I’m so flawed? I look at all the people around me, all these accomplished people who have their shit together, and I’m like, ‘one of these things is not like the other,’” she says, taking a sip of her flat white. “I was literally in the Olympic Village thinking: Everybody is probably looking at me wondering: Why the hell is she here?”

They weren’t. They don’t. She knows that.

And yet her mind races as fast as she does. It takes up So. Much. Space. When she’s running, though, the noise disappears. She’s not Olympic Molly or Eating Disorder Molly, she’s not even, really, Runner Molly. “When I’m running,” she says, “I’m the most authentic version of myself.”

Talking helps, too. Molly first shared her mental health history a few years ago, “before she was famous,” as she puts it. After the Olympics, though, she kept talking and hasn’t stopped. The Tokyo Games were a turning point, she says. Suddenly the most revered athletes in the world were opening up about their mental health. Molly credits Simone Biles’s bravery for her own. If Biles, and Michael Phelps and Naomi Osaka, could come clean... then maybe a nerdy, niche-y, unlikely medaling marathoner could, too.

“Those guys got a lot more shit for it than I did,” says Molly. “I got off easy. I’m not a household name,” she laughs. She knows she can be candid and off the cuff—and chat freely in a not-empty café—in a way Biles never could. “I’m a nobody!” she laughs.

Still, a nobody with 232,000 Instagram followers whom she has touched in very IRL ways—becoming an unintentional poster woman for normalizing mental health challenges among athletes. “You are such an incredible inspiration,” @1percentpeterson posts, one comment of a zillion similar. “It’s ok to not be ok!” says another. Along with all the online love is, of course, online hate. Molly rattles off a few lowlights: “She’s an attention-seeking whore,” “Her bones are so brittle she’ll never race again,” “She’s running so badly and posting a lot she should really focus on her running more.” Molly finds it curious. “I’m like, ‘If you hate me, you don’t need to follow me, sir.’”

It’s Molly’s nobody-ness—what Outside writer Martin Fritz Huber called her “runner-next-door” persona, and I’ll just call “genuine personality”—that has made her somebody in running’s otherwise reserved circles.

Somebody who (gasp!) high-fives her sister in the middle of a major race, as she did at mile 18 of the 2021 New York City Marathon. “They shat on me in the broadcast for it,” she says. “They were like, ‘She’s not taking this seriously.’” (Except, uh, then she set the American course record, so…)

Somebody who, obviously, swears like a sailor and dances awkwardly on Instagram, who dresses up like a turkey, and viral-tweets about getting mansplained on an airplane. (“He starts telling me how I need to train high mileage & pulls up an analysis he’d made of a pro runner’s training on his phone. The pro runner was me. It was my training. Didn’t have the heart to tell him.”)

Somebody who makes every middle-aged mom-runner I know swoon like a Swiftie and say: “OMG! YOU HUNG OUT WITH MOLLY SEIDEL!!?” Middle-aged dad-runners, too. “I saw her once in Golden Gate Park!” my friend Dan fanboyed when he heard. “I waved!” Did she wave back? “She smiled,” he says, “while casually laying down 5:25s.”

And somebody who was as outraged as I was that I bought a $16 tube of French toothpaste from my hip Flagstaff motel. (It was 10 p.m.! It was all they had!) “For that price it better contain top-shelf cocaine,” she texted. Lest LetsRun commenters take that tidbit out of context: It’s a joke. It’s, in part, what makes Molly America’s most relatable pro runner: She’s not afraid to make jokes. (While we’re at it… Don’t knock her for smoking a little legal weed, either. That’s so 2009. Per the World Anti-Doping Agency: Cannabis is prohibited during competition, not at a Christmas party two months before it. Per Molly: “People would be shocked to know how many pro runners smoke weed.”)

I can’t believe I never asked to see it. Molly’s medal. A real, live Olympic medal. Maybe because it was tucked into a credenza along with Matt’s menorah and her maneki-neko cat figurines from Japan. But I think it was because hanging out with Molly felt so…normal, I almost forgot she’d won one.

People think elite distance runners have to be one-dimensional, she says. That they have to be sculpted, single-minded, running-only robots. “Because that’s what the sport has been,” she says.

Molly falls for it, too, she says. She scrolls the feeds, sees her fellow pros living seemingly perfect lives. She wants everyone to know: She’s not. So much so that she requested we not print the photos originally commissioned for this story, which were taken when she was at the lowest of lows. (“It’s been...refreshing...to be pretty open and real with Rachel [about] the challenges of the last year,” she wrote in an email to Runner’s World editors. “But the photos [were taken at] a time when I was really struggling and actively trying to hide how bad my eating disorder had become.”)

Molly finds the NYC Marathon high-five thing comical but indicative of a more serious issue in elite running: It takes itself too seriously. It’s too…elitist. Too stilted. “Running a marathon is a pretty freaking cool experience!” If you’re not having fun, she asks rhetorically, what’s the point? Still, she admits, she isn’t always having fun. Though you wouldn’t know it from her Instagram. “Oh, I’m very good at making it seem like I am,” she says.

She used to enjoy social media when it was just her friends. Before she gained 50,000 followers in a single day after the trials, and some 70,000 on Strava. Before the pandemic, before the Olympics. Keeping up with content became a toxic chore. “You feel like you’re just feeding this beast and it’s never going to stop,” she says. She’s taken to deleting the app off her phone, reloading it only to fulfill contractual agreements and post for her sponsors, then deleting it again.

As much as she hates having to post, she enjoys plugging products the only way that feels natural: through parody. As does Izzy, her influencer sister, who, like Molly, prefers to skewer rather than shill (à la their idea behind their joint Insta account: @sadgirltrackclub). “The classic influencer tropes make me want to throw up,” she says (perverse pun as a recovering bulimic not intended). “New Gear Drop!’ or ‘This is my Outfit of the Day!’ Cringe. “Hot Girl Instagram is not how I identify,” she says.

Nor is TikTok. “Sponsors tell me all the time: You should TikTok! I’m like, ‘I am not doing TikTok.’ I know how my brain works. They’ll say, ‘We’ll pay you less if you don’t’—and I’m, like, I don’t care.”

And to those sponsors who ghosted her after she returned to eating disorder treatment, good riddance. “Michelob dropped me like a bad habit,” she says. “Whatever. You have watery-ass beer anyway.”

To those who have stood by her, though, she’s utterly devoted. Pissed she couldn’t wear the Puma panther head to toe in Tokyo, Molly took off her Puma Deviate Elites and tied them over her shoulder, obscuring the Nike logo on her Olympic singlet for all the world to see. Or not see. “Nike isn’t paying my fucking bills.”

The love is mutual, says Erin Longin, a general manager at Puma. After decades backing legends like Usain Bolt, Puma was relaunching road running and wanted Molly as their guinea pig. “She’s a serious athlete and competitor, but she also has fun with it,” says Longin. “Running should be fun. Molly embodies that.” At their first meeting, in January 2020, Molly made them laugh and nerded out over their new shoes. “We all left there, fingers crossed she’d sign with us,” says Longin.

Come February, they all flipped out. Longin was watching the trials, not expecting much. And then: “We were all messaging, “OMG!!” Then Molly killed in London. Medaled in Tokyo. “What she did for us in that first year…” says Longin. “We couldn’t have planned it!”

Then came the second year, and the third, and throughout it all—injuries, eating disorder treatment, missed races, missed opportunities—Puma hasn’t flinched. “It’s easy for a company to do the right thing when everything is going great,” Molly posted in April, heartbroken from her couch instead of Heartbreak Hill. “But it’s when the sh*t hits the fan and they’re still right there with you….” She received 35,000 hearts—and a call from Longin: “You make me feel so proud.”

Does it matter to Puma if Molly never places—never races—again? “Nope,” Longin says.

My last afternoon in Flagstaff, it’s cloudy skies, still freezing. I find Molly on the high school track wearing neoprene gloves, black puffy coat, another pair of Pumas. Her breath is white, her cheeks red. Her legs churning in even, elegant strides. Upright, alone, at peace, backed by snow-dusted peaks. Running itself is what matters, not racing, she tells me. “I honestly don’t give a shit about winning,” she says. All she wants—really wants, she says—is to be healthy enough to run until she’s old and gray.

Molly’s favorite runner is one who didn’t get to grow old. Who made his mark decades before she was born: Steve Prefontaine. “Pre raced in such a genuine way. He made people feel something,” she says. “The sports performances you truly remember,” she adds, “are the ones where you see the struggle, the work, the realness.”

Sounds familiar. “I hate conversations like, ‘Who’s the GOAT?’” Molly continues. “Who fucking cares? Who’s got the story that’s going to get people excited? That’s going to make some kid want to go out and do it?”

I know one of those kids: My best friend’s daughter, Quinn, a rising track phenom in Oregon, who has dealt with anxiety and OCD tendencies. She has a picture of Molly Seidel, and her times, taped to her bedroom wall. This past May, Quinn joined Nike’s Bowerman Club. She was named Oregon Female Athlete of the Year Under 12 by USATF. She wants to run for Notre Dame.

“Quinn loves running more than anything,” her mom tells me, texting photos of her elated 11-year-old atop the podium. “But I don’t know…” She’s unsure about setting her daughter on this path. How could she not, though? It’s all Quinn wants to do. Maybe what Quinn, too, feels born to do.

It’ll be okay, I tell her, I hope. Quinn has something Molly never had: She has a Molly.

Molly and I catch up via phone in June. A team of doctors in Germany has overhauled her biomechanics. She’s been running 110 miles a week, feeling healthy, hopeful. Happy. A month later, severe anemia (and accompanying iron infusions) interrupts her summer racing schedule. She cancels the couple of 10Ks she had planned and entertains herself by popping into the UTMB Speedgoat Mountain Race: a 28K trail run through Utah’s Little Cottonwood Canyon—coming in second with a 3:49:58. Molly’s focus is on the Chicago Marathon, October 8th; her first major race in almost two years.

Does it matter how she does? Does it matter if she slays the Olympic Trials in February? If she makes it to Paris 2024? If she fulfills her childhood dream and brings home gold?

Nah. Not if—like Matt, like Puma, like, finally, even Molly herself—you see Molly the Runner for who she really is: Molly the Mere Mortal. She’s the imperfect one who puts it perfectly: What matters isn’t her time or place, how she performs on the pavement. Or social media posts. What matters—as a professional athlete, as a person—is how she makes people feel: human.

She’d been finally—finally—fit on all fronts; ready to race, ready to return. She needed Nagoya. And then, nothing. “It feels like I’m back at the bottom of the well,” says Molly, driving home from Whole Foods in her Toyota 4Runner. “This last year-and-a-half has been so difficult. It’s just been a lot of doubt. How do I approach this, as someone who has now won a medal? Like, man, am I even relevant in this sport anymore?” She pops a piece of gum in her mouth. I wait for her to offer me some, because that’s what you do with gum, but she doesn’t. She’s so in her head. “It’s hard when you’re in the thick of it, you know, to figure out: Why the fuck do I keep doing this? When it just breaks my heart over and over and over again?”

(10/08/23) Views: 119Runner’s World

Annie Rodenfels Wins Boston 10k For Women

The 47th running of the Boston 10K for Women, presented by REI, returned to the Boston Common and the streets of Boston and Cambridge on Saturday.

Over 4,000 women participated in the autumn classic, which began at 8:50 a.m. for handcycle and wheelchair participants and at 9 a.m. for all runners.

Formerly known as the Tufts Health Plan 10K for Women, the race is New England's largest all-women's sporting event.

The 6.2-mile course brings runs through Boston’s Back Bay and into Cambridge and finishes on Charles Street between the Public Garden and Boston Common.

This year's race was won by Annie Rodenfels, who broke the tape in her 10K debut in a time of 32:08. She was followed by Emily Venters with a time of 32:31 and Jenny Simpson at 32:39.

A Boston resident, Rodenfels surged on the Massachusetts Avenue bridge and ran uncontested through the last mile until the Charles Street finish line.

“I thought I would sit back and wait and out-kick them at the end, like -- their mistake if they leave me until the end -- because besides maybe Jenny Simpson I think I’ve probably got the best kick in the field,” Rodenfels said afterward, with an American flag draped around her shoulders. “But I just felt too good, I figured I’d just go for it. What do I have to lose?”

For Rodenfels, who trains along the banks of the Charles River, the familiarity aided her approach in the new distance.

“I like the course a lot – I love running in Boston, I feel like I can have a mediocre year the rest of the year and then when I get a race in Boston, I knock it out of the park. I feel like I get more cheers because I am from around here,” said Rodenfels, who earned $9,000 with the victory.

Winning the Masters Division and finishing 11th overall was Sara Hall, who clocked a 33:19. Fourteen-year-old Madelyn Wilson won the wheelchair division in a time of 35:50, racing for the first time in a larger chair.

(10/09/23) Views: 114

Kiptum smashes world marathon record with 2:00:35, Hassan runs 2:13:44 in Chicago

Kenya’s Kelvin Kiptum became the first athlete to break 2:01 in a record-eligible marathon, clocking a tremendous 2:00:35* to take 34 seconds off the world record at the Bank of America Chicago Marathon on Sunday (8).

On a remarkable day of racing, Dutch star Sifan Hassan moved to No.2 on the women’s all-time list, running 2:13:44 to triumph in the World Athletics Platinum Label road race. The only woman to have ever gone faster is Ethiopia’s Tigist Assefa, who set a world record of 2:11:53 to win the BMW Berlin Marathon last month.

Less than six months on from his 2:01:25 London Marathon win, which saw him become the second-fastest marathon runner of all time, Kiptum improved by another 50 seconds to surpass the world record mark of 2:01:09 set by his compatriot Eliud Kipchoge in Berlin last year.

In the third marathon of his career, which began with a 2:01:53 debut in Valencia last December, Kiptum even had enough energy to celebrate his historic performance on the way to the finish line – pointing to the crowds and the tape on his approach.

The 23-year-old broke that tape in 2:00:35, winning the race by almost three and a half minutes. Defending champion Benson Kipruto was second in 2:04:02 and Bashir Abdi was third in 2:04:32.

Kiptum pushed the pace throughout the 26.2-mile race. He broke away from a seven-strong lead group after reaching 5km in 14:26, joined only by his compatriot Daniel Mateiko, who was making his marathon debut. They were on world record pace at 10km, passed in 28:42, but the tempo dropped a little from that point and they reached half way in 1:00:48.

Kiptum had been running in a hat but that came off as they entered the second half of the race. After 30km was passed in 1:26:31, Kiptum kicked and dropped Mateiko. He was glancing over his shoulder but running like he still had the world record – not only the win – in his sights.

A blistering 5km split of 13:51 took him to the 35km checkpoint in 1:40:22 and he was on sub-2:01 pace, 49 seconds ahead of Mateiko.

Continuing to run with urgency, he passed 40km in 1:54:23 – after a 27:52 10km split – and sped up further, storming over the finish line with the incredible figures of 2:00:35 on the clock.

"I knew I was coming for a course record, but a world record – I am so happy,” he said. “A world record was not on my mind today, but I knew one day I would be a world record-holder.”

Despite only having made his marathon debut 10 months ago, Kiptum now has three of the six fastest times in history to his name. Only Kipchoge (with 2:01:09 and 2:01:39) and Kenenisa Bekele (with 2:01:41) have ever gone faster than the slowest of Kiptum’s times.

Mateiko had helped to pace Kiptum to his 2:01:25 win in London, running to the 30km mark. The pair stayed together until that point in Chicago, too, but Mateiko couldn’t maintain the pace and dropped out after reaching 35km in 1:41:11.

Kenya’s Kipruto used his experience of the course to leave the chase group behind after 35km and was a comfortable runner-up in 2:04:02, finishing half a minute ahead of Belgium’s world and Olympic bronze medallist Abdi.

Kenya’s John Korir was fourth in 2:05:09, Ethiopia’s Seifu Tura fifth in 2:05:29 and USA’s Conner Mantz sixth in 2:07:47.

In the women’s race, Hassan returned to marathon action just six weeks on from a World Championships track medal double that saw her claim 1500m bronze and 5000m silver in Budapest.

She was up against a field including the defending champion Ruth Chepngetich of Kenya, who was on the hunt for a record third win in Chicago following her 2:14:18 victory last year.

It soon became apparent that it would be those two athletes challenging for the title. After going through 5km in 15:42 as part of a pack that also featured Kenya’s Joyciline Jepkosgei and Ethiopia’s Megertu Alemu and Ababel Yeshaneh, Chepngetich and Hassan broke away with a next 5km split of 15:23 and reached 10km in 31:05 – on pace to break the recently-set world record.

They ran a 10km split of 30:54 between 5km and 15km, that point passed in 46:36, and they maintained that world record pace to 20km, reached in 1:02:14.

Chepngetich had opened up a six-second gap by half way, clocking 1:05:42 to Hassan’s 1:05:48, but Hassan would have surely felt no concern. On her debut in London in April, after all, she closed a 25-second gap on the leaders despite stopping to stretch twice, and went on to win in 2:18:33.

In a race of superb depth, Alemu, Jepkosgei and Yeshaneh were still on 2:14:52 pace at that point as they hit half way together in 1:07:26.

Hassan soon rejoined Chepngetich at the front and they ran side by side through 25km in 1:18:06. Then it was Hassan’s turn to make a move. Unable to maintain the pace, Chepngetich had dropped 10 seconds behind by 30km, reached by Hassan in 1:34:00, and from there the win never looked in doubt. The Dutch athlete was half a minute ahead at 35km (1:50:17) and she had more than doubled that lead by 40km (2:06:36).

Hassan was on track to obliterate her PB and also the course record of 2:14:04 set by Brigid Kosgei in 2019, which had been the world record until Assefa’s 2:11:53 performance last month.

She held on to cross the finish line in 2:13:44, a European record by almost two minutes. With her latest performance, the versatile Hassan is now the second-fastest woman in history for the track mile, 10,000m and marathon.

"The first group took off at a crazy pace, but I wanted to join that group,” said Hassan. “The last five kilometres, I suffered. Wow – I won again in my second marathon in a fantastic time. I couldn't be happier.”

Behind her, Chepngetich held on for second place in 2:15:37 as the top four all finished under 2:18 – Alemu placing third in 2:17:09 and Jepkosgei finishing fourth in 2:17:23. Ethiopia’s Tadu Teshome was fifth in 2:20:04, her compatriot Genzebe Dibaba sixth in 2:21.47 and USA’s Emily Sisson seventh in 2:22:09.

Leading results

Women1 Sifan Hassan (NED) 2:13:44 2. Ruth Chepngetich (KEN) 2:15:37 3. Megertu Alemu (ETH) 2:17:09 4. Joyciline Jepkosgei (KEN) 2:17:235 Tadu Teshome (ETH) 2:20:046 Genzebe Dibaba (ETH) 2:21:477 Emily Sisson (USA) 2:22:098 Molly Seidel (USA) 2:23:079 Rose Harvey (GBR) 2:23:2110 Sara Vaughn (USA) 2:23:24

Men1 Kelvin Kiptum (KEN) 2:00:352 Benson Kipruto (KEN) 2:04:023 Bashir Abdi (BEL) 2:04:324 John Korir (KEN) 2:05:095 Seifu Tura (ETH) 2:05:296 Conner Mantz (USA) 2:07:477 Clayton Young (USA) 2:08:008 Galen Rupp (USA) 2:08:489 Samuel Chelanga (USA) 2:08:5010 Takashi Ichida (JPN) 2:08:57

(10/08/23) Views: 104World Athletics

Lessons from the long run: with Kipyegon, Kipchoge and Sang

The long run, for elite and amateurs alike, forms an integral part of distance runners’ training.

In the west of Kenya, 20km to the south-east of Eldoret, that weekly ritual takes place early on a Thursday morning.

At 6am sharp the first runners make their way out of the gates of the Global Sports Communications Camp in Kaptagat to join some local runners who will try to keep them company.

In the pitch-black late June morning, the runners have already woken up half an hour or so before to get dressed, take some sips of water and go to the toilet.

The 30 or so athletes do not eat beforehand. They have determined that there are benefits to running fasted, the most prominent being training your body to get better accustomed to taking energy from your body’s fat reserves, something that may be important when carbohydrates sources are depleted towards the end of a marathon.

Of course, these are experienced athletes. For the double Olympic champion making his way to the group, he has spent 20 years building up and adapting his body to such challenges.

What is possible for Eliud Kipchoge would be simply unsustainable, and even ill-advised, for athletes new to the sport.

This particular morning, coach Patrick Sang has assigned the ‘Boston loop’ – an undulating route with far more elevation than its namesake marathon, eventually finishing high on the escarpment a few hundred meters higher than the 2200m starting elevation at Kaptagat.

For the Global Sports group, it is simply 40km straight out; the minibuses and pick-up trucks following them picking them up after to drive them home.

Most of Sang’s athletes training for an autumn marathon are expected to complete the full distance, among them three-time world cross-country champion Geoffrey Kamworor, fellow 2:04 marathon-man Kaan Kigen Özbilen, Kipchoge and a collection of five others all boasting either sub-60-minute half marathon or sub-2:07 marathon bests.

World and Olympic medalist Linet Masai and 2:20 marathon runner Selly Chepyego, setting off 15 minutes beforehand, have also been set that distance goal.

For world and Olympic champion and multiple world record-holder Faith Kipyegon, today’s task is 30km. Despite being on the longer end of what might be expected from a 1500m runner, Kipyegon is insistent that this run is her favorite type of training.

It may also be some indication of the strength shown in her 5000m world record in Paris.

Sang’s final instructions are minimal. He does not prescribe paces, simply asking that his athletes set an honest pace, go on how they feel and try if possible to pick up the pace towards the end of their run.

The early footsteps are on a dirt road, the group paying attention to where their marathon-specific shoes land and running in silence. Information about tree routes or dips in the road is often communicated via hand signals pointing to the hazard.

From the off, the going is uphill and within 10km the group is receiving the first of their carbohydrate drinks being passed from the pick-up truck following them.

After 15km the group hits the first of the tarmac roads of the C51 and the pace then starts to rise, slowly and subtly.

As they do, they gradually catch the groups ahead of them.

Geoffrey Kirui, the 2017 world marathon champion, has been told to run by himself as he is returning from an injury. Sang has intentionally encouraged Kirui not to fall into the usual pitfalls of over-exerting himself to go with a group.

Likewise Daniel Mateiko – the ninth fastest half-marathon runner in history, boasting a 58:26 best – was told to set off a few minutes before and will then join the group up to about the 35km marker. Still only 24 years of age and racing over a shorter distance, Mateiko’s training has its own minimal differences with the shorter-distance athletes generally doing shorter long runs.

Throughout the run, Sang will come alongside in the pick-up, judging his athletes’ efforts from the way they run. He later tells us he can notice minor indications from the way they land their feet on whether recent training has taken its toll.

Little advice is given; those he coaches have done this route many times before. More welcome instead are the drinks passed around every 5km or so. The group stays intact for almost 30km before it slowly fragments, Sang encouraging his athletes to sustainably push their effort over the final kilometers.

Kipyegon herself is nearing the end of her run, gradually progressing throughout the 30km but not pushing herself to the point of depletion.

Unfortunately for her, the moment her watch completes the distance, a few minutes over two hours after she began, is almost the highest point the group will reach that day.

She stops, jogs slowly for a few hundred meters before jumping in the van.

About a litre of carbohydrate drinks consumed after her run, she will not eat until an hour or so later when the whole group returns to the camp.

A long line of runners scattered along the road has yielded to a few isolated pockets completing the full distance and the leading group has whittled down to four.

Though interspersed with steady rises, the final five kilometers are slightly downhill. Kipchoge, Özbilen, Laban Korir and Hillary Kipchirchir run four abreast, completing these last kilometers in a few seconds inside 15 minutes.

Two hours 22 minutes after they started, they finish their undulating 40km with over 500m of elevation at a pace about 30 minutes slower than their best marathon times. It is an effort they might refer to as ‘steady’ and one in the midst of a typical 220km training week.

Like Kipyegon, they consume about a litre of drink as they get in the vans and make the 40-minute journey home, eating a nutritionally simple meal of beans, ugali, vegetables and some protein upon their return.

Their reward? A rare afternoon without another run, some sleep and a lighter Friday of two short easy runs.

A similar routine in a different setting to runners throughout the world, there are morsels of lessons for the everyday runner.

Progress sustainably, hydrate appropriately and perhaps trust your effort over your watch.

(10/09/23) Views: 98George Mallett for World Athletics

The simple, yet effective, diet of Eliud Kipchoge

If you think a high-performance diet needs to be complicated, think again. In an interview with Kenyan news outlet Nairobi News, marathon world record-holder Eliud Kipchoge revealed that he adheres to a simple yet effective diet that supports his intense training and racing schedule. Fresh off his fifth win at the Berlin Marathon, Kipchoge’s diet seems to be working for him, and now we know what keeps the world’s best marathoner going.

It’s about balance

Like most elite runners, Kipchoge’s diet revolves around a balanced mix of protein and carbohydrates. One of Kipchoge’s favourite foods is the Kenyan staple, ugali, a maize meal porridge he typically enjoys with lean beef and a side of nutrient-rich vegetables, like managu, cabbage or kale. Kipchoge usually incorporates other carbohydrates into his meals, often accompanying his ugali with beans, potatoes, or chapati. When he travels, he opts for the classic pre-race meal of runners everywhere–pasta

Good nutrition starts in the morning

To kickstart his day after long training runs, Kipchoge’s breakfast typically consists of a combination of white tea, bread, and various fruits. On race day, he opts for slightly lighter breakfast options like cereals and milk or oats, ensuring he eats enough to fuel his race without overwhelming his digestive system.

Hydrate, hydrate, hydrate

Hydration is also a key component of Kipchoge’s regimen. He constantly aims to drink three litres of water per day, replenishing the fluids lost through sweat during his intensive workouts. He sometimes enjoys plain milk or mursik, a traditional fermented milk popular in Kenya.

Carbs are key

Kipchoge’s nutritionist emphasizes consuming the right carbohydrates to enhance his endurance performance. This includes foods like rice, pasta, potatoes, oatmeal, bananas and pancakes in his diet. His nutritionist points out, however, that runners should be cautious when including a lot of whole grains or high-fibre carbohydrates in their diets since this can cause gastrointestinal distress for some.

Keep it simple

Despite his success, Kipchoge’s dietary approach remains uncomplicated, focusing on locally sourced, wholesome ingredients that provide the necessary nutrients to fuel his training. Nutrition is highly individual, so following the marathon world record holder’s diet religiously is not the right approach, but the simplicity of his diet is something everyone can emulate.

Your nutrition plan does not need to be complicated or expensive to be effective. By focusing on whole foods and balanced nutrition, you can get the energy and nutrition you need to perform at your best.

(10/07/23) Views: 96Brittany Hambleton

Kenyans Mathew Kiplagat and Beatrice Toroitich won the 40th edition of the Wizz Air Sofia Marathon

Kenya’s Mathew Kiplagat won the 40th edition of the Wizz Air Sofia Marathon held on Sunday (08) in Sofia, Bulgaria

The 35 year-old took the honors in a new personal best time of 2:12.12 and was followed a distant later in second by Ethiopia’s Alem Niguse in 2:14.31 with Chakib Latrache from Morocco wrapping up the podium three finishes 2:15.43.

Kenya’s Hosea Kipkemboi, France’s Alaa Hrioued and Duncan Koech also from Kenya finished in fourth, fifth and sixth place in respective time of 2:21.36, 2:22.06 and 2:22.10.

Kenya’s Beatrice Toroitich won the women’s marathon title at the 40th edition of the Sofia Marathon held on Sunday (08) in Sofia, Bulgaria.

The 41 year-old took the honors in 2:38.26 and was followed by Bulgaria’s Marinela Ninova in second place in 2:41.02 with her compatriot Hellen Kimutai sealing the podium three finishes in a time of 2:49.07.

Gladys Biwott from Kenya and Ethiopia’s Sintayeho Kibebo finished in fourth and fifth in respective time of 2:51.43 and 2:55.58.

(10/09/23) Views: 96John Vaselyne

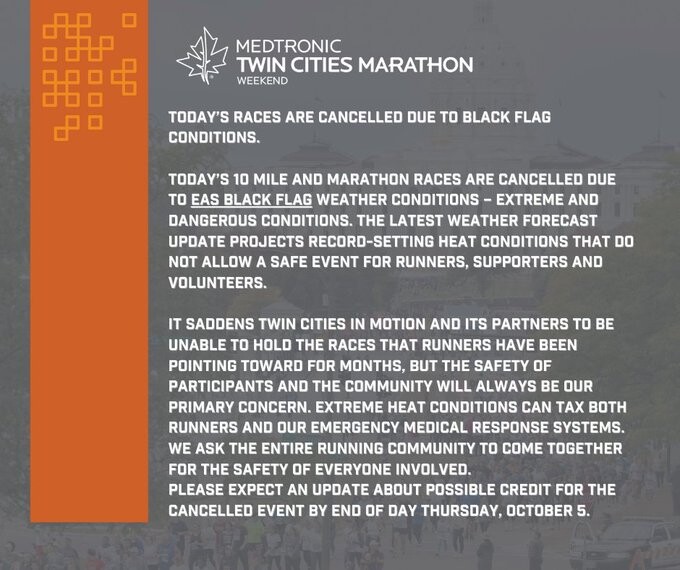

TCS Toronto Waterfront Marathon extends warm welcome to canceled Twin Cities Marathon athletes

The TCS Toronto Waterfront Marathon is extending a helping hand to several elite runners who were affected by the last-minute heat cancellation of the 2023 Twin Cities Marathon last Sunday.

Although Canada’s largest marathon had been sold out for months, marking the first time in the race’s history that the marathon has reached full capacity this early. There ended up being several withdrawals in the men’s and women’s elite fields two weeks before the Oct. 15 race day.

Jim Estes, the manager of the elite program at the Twin Cities Marathon, reached out to TCS Toronto Waterfront Marathon race director Alan Brookes, exploring the possibility of accommodating some of the elite runners. Brookes shared that he and Jim have a close relationship and have worked on elite teams at Chicago and Houston marathons. “We ended up extending three spots to athletes who did not get the chance to run the marathon in Minnesota,” says Brookes.

This period is crucial for U.S. marathoners, as many are shooting to qualify for U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials in Orlando next February. The fall marathon season represents a final opportunity to secure a qualification spot there or to chase an Olympic qualifying time of 2:08:10 (men) and 2:26:50 (women) before the trials.

Toronto was not the only marathon to offer invitations. The McKirdy Micro Marathon in Valley Cottage, N.Y., the Indianapolis Monumental Marathon and the Philadelphia Marathon have also offered spaces in their elite fields for athletes originally slated to compete in Twin Cities.

The Twin Cities Marathon was set to host nearly 8,000 runners on Oct. 1 but ended up being abruptly canceled just two hours before its 7 a.m. start due to soaring temperatures. Despite the short notice, many runners who had traveled to Minnesota decided to go ahead with their race on their own. The temperature in Minneapolis–Saint Paul, Minn., reached a high of 27 C (80 F) by 11 a.m. on Sunday.

Eli Asch, the race director of Twin Cities, defended their decision to cancel the race in an interview with Runners World, stating, “We saved lives.” However, Asch did not confirm whether the race would provide refunds or offer credits to the 20,000 registered participants but said the race’s intention is to be “as generous as possible.”

(10/06/23) Views: 88Marley Dickinson

Three progression workouts to transform your training

If you have ever started off strong on race day but found yourself falling apart at the closing stages, a progression run may be the ticket to elevating your performance. In a traditional progression run, a runner starts at an easy pace and gradually increases their speed throughout the run, finishing faster than they began. The progression training session aims to train the body to run efficiently, and to build endurance while gradually increasing the effort level.

Progression workouts are versatile and fun to switch up: run them by pace or by Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE), on trails or on roads, and adjust the distance and time to suit any goals.

Because your body is properly warmed up in a progression session before you begin any tough effort, you have a lower risk of injury than in many other hard-and-fast traditional speed workouts. You’ll also recover more quickly from a progression session than you would with faster-paced intervals. We have three progression workouts you can slide into your training schedule this week–you’ll reap the rewards with tireless legs next race.

For all of these workouts, make sure to use the beginning of the run as your warm up, taking it very slow and easy.

1.- Thirds progression run

A thirds progression run gives your aerobic capacity a boost while you practice managing steady pacing, and simulates using discipline during the initial stages of a race.

For this workout, break up your run into three equal parts. It doesn’t matter whether you train using distance or time; split the total up accordingly.

Begin running at an easy pace and gradually speed up as you enter the next third of your run. Make sure your speed changes are slight and not abrupt: each pace should feel sustainable.

If your progression run is scheduled for 60 minutes, run the first 20 minutes at an easy pace, the next 20 minutes at a race pace, and the last 20 minutes at a pace that is 10 seconds faster than your race pace.

Cool down with five minutes of very easy running.

2.- Fast finish progression run

Finishing a progression run quickly will help you crush that fast race-day kick. This workout is the perfect way to push mind and body to simulate racing conditions, without overtaxing yourself, and needing extra recovery time.

Start out at an easy pace or effort and extend that throughout most of this session, leaving only four to six minutes at the end for your hard effort. The final few minutes of this workout should be a much harder effort than in your other progression runs because the fast running time is much more limited.

Think of your 5K race pace or effort for the last section.

Cool down with five to 10 minutes of very easy running.

3.- Fast finish progression run

Finishing a progression run quickly will help you crush that fast race-day kick. This workout is the perfect way to push mind and body to simulate racing conditions, without overtaxing yourself, and needing extra recovery time.

Start out at an easy pace or effort and extend that throughout most of this session, leaving only four to six minutes at the end for your hard effort. The final few minutes of this workout should be a much harder effort than in your other progression runs because the fast running time is much more limited.

Think of your 5K race pace or effort for the last section.

Cool down with five to 10 minutes of very easy running.

(10/09/23) Views: 83Keeley Milne

Kenya’s Alfred Kipchirchir is set to debut at TCS Toronto Waterfront Marathon

Kenya’s Alfred Kipchirchir makes his marathon debut on October 15 at the TCS Toronto Waterfront Marathon and he hopes it goes as well as that registered by one of his training partners.

Kipchirchir, 29, trains in a group which includes Vincent Ngetich who chased two-time Olympic champion Eliud Kipchoge along the streets of Berlin last weekend, eventually finishing second in the famed Berlin Marathon in 2:03:13. It was a stunning performance and one that has inspired Kipchirchir.

“I am looking forward to running 2:05 or 2:04 in Toronto,” he reveals. “My training is going well. We run between 180 and 210km in a week.”

According to Coach Peter Bii these two star athletes trained together right up until the last two weeks with Kipchirchir running step for step with Ngetich. Of course, the latter had to back off training to prepare for the Berlin Marathon.

“I want to debut in Toronto because I like what I have heard about the city from Enock Onchari,” says Kipchirchir. A year ago Onchari, another member of the group, finished 4th in Toronto Waterfront.

“We know it’s very cold (in Toronto) from when Onchari was there. I have no information about the course,” he continues.

Kipchirchir has dipped under 60 minutes for the half marathon distance three times in the past three years with his best 59:43 set in the 2021 Madrid Half Marathon. With his current training going well, it is not unreasonable for him to have very high expectations.

All of his life the village of Kapkenu has been his home. It’s about 80 Kilometres from the famed ‘runners’ town’ of Iten. As a young boy he admired the achievements of his neighbour Geoffrey Kamworor who won both the world half marathon and world cross country championships three times and was twice winner of the New York City Marathon. But it was a family member who pushed him to become a runner in his youth.

“My brother introduced me to running. He works as the manager of the High Altitude Training Centre run by Lorna Kiplagat in Iten,” he reveals.

Like many Kenyan athletes, he leaves home every Monday morning and travels to the group’s training camp where he will remain until the following Saturday. He doesn’t own a car and relies upon a ‘matatu’, a publicly shared minibus. Sometimes his brother will drive him though. It’s a sacrifice he is prepared to make to ensure he achieves his running potential.

At the training camp there is much camaraderie. The shared sense of commitment and sacrifice he finds builds mental fortitude which he hopes to translate into a superb performance in Toronto. But there is also time to relax.

“I like to listen to music, Kalenjin (tribal) songs, when I am home and at camp,” he says. “And I watch football. I am a Manchester United supporter.”

Both he and Coach Peter laugh heartily when the interviewer shakes his head at the current disruption at the club. Among the group there are Tottenham Hotspur, Chelsea and Manchester City fans says Peter.

Earnings from Kipchirchir’s running career have helped him take care of his immediate family, his wife Rhoda Jepkemboi Mukche and his 14-month-old daughter Praise Jepkorir.

“I have already bought a small farm,” he says. “It’s two acres. I grow maize and I have goats. My family members are at my home and they look after the farm when I am away at camp.”

The TCS Toronto Waterfront Marathon course record is 2:05:00 held by Philemon Rono since 2019. On that occasion three runners came home within thirteen seconds of Rono, once again demonstrating fast times can be achieved here.

The transition to the marathon sometimes proves difficult for even some of the best distance runners in the world. But something in his preparation and attitude reveals Kipchirchir will have a memorable debut in Toronto.

(10/10/23) Views: 81

Christopher Kelsall

Two American men achieve the Olympic standard at Chicago Marathon

The American contingent was led by Conner Mantz, who finished sixth overall and ran a personal best of 2:07:47. His former BYU teammate Clayton Young placed seventh in 2:08:00. Both athletes dipped under the Olympic qualifying standard of 2:08:10.

Running his first marathon since the 2022 World Athletics Championships in Eugene, Oregon, Galen Rupp finished eighth in 2:08:48.

Three American women crack the top 10

A year after breaking the national record in Chicago, Emily Sisson returned as the top American with a seventh-place finish in 2:22:09. Olympic bronze medalist Molly Seidel finished eighth overall in 2:23:07, and Sara Vaughn placed 10th in 2:23:24.

After turning 40 in July, Des Linden broke the American masters record by running 2:27:35, beating the previous record (2:27:47) set by Deena Kastor.

(10/09/23) Views: 80