Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Search Results for Ultra

Today's Running News

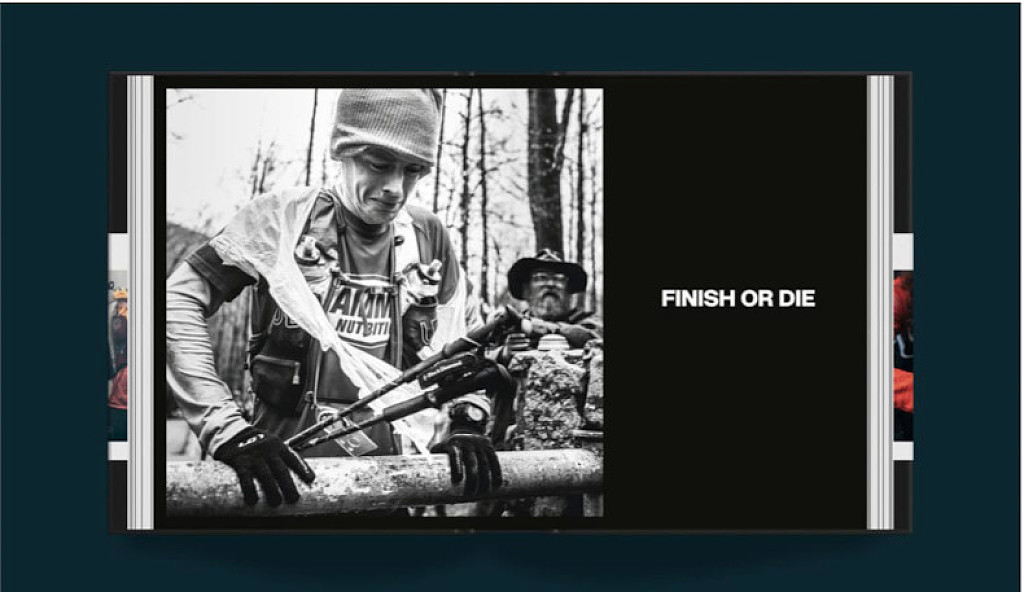

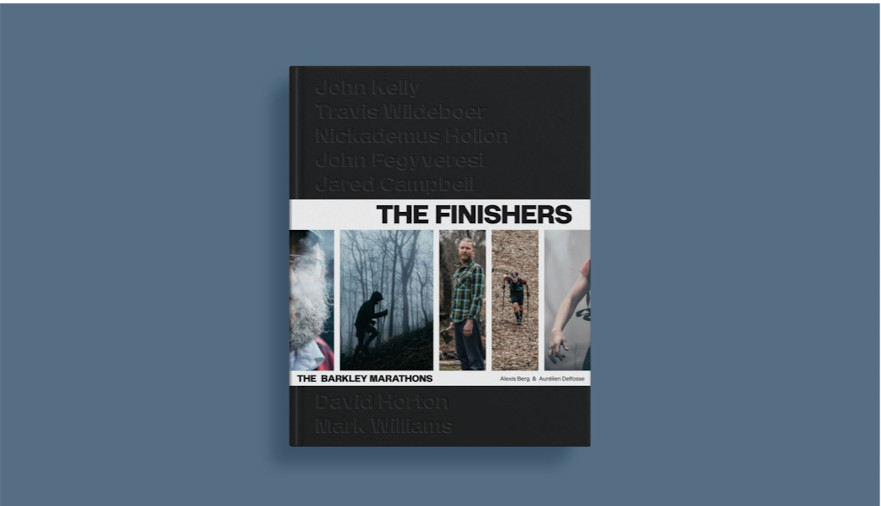

Barkley Marathons book documents race’s 15 finishers

If you follow trail running or ultrarunning, odds are you know about the Barkley Marathons. You might not know much about the race, but you’ll at least know it’s incredibly difficult. So difficult, in fact, that only 15 runners have ever completed the roughly 100-mile run through Tennessee’s Frozen Head State Park in its 35-year history. A new book titled The Finishers has been published in French (with an English edition on its way), which tells the stories of those 15 Barkley Marathons finishers, as well as the tale of the event itself, through photography and runners’ stories from one of the world’s toughest races.

The race

Laz Lake is well known in the world of ultrarunning. He has created several races, all of which are long, gruelling affairs, but his most famous event is the Barkley. The first running of the event was in 1986, and it didn’t see a finisher until nine years later, when Mark Williams completed the full route in 1995.

Since then, 14 more runners have joined Williams on the short list of finishers, and a couple of men have recorded multiple finishes (Brett Maune finished in 2011 and 2012 and Jared Campbell finished in 2012, 2014 and 2016). The most recent finish belongs to John Kelly, who was the only person to complete the race in 2017. (Gary Robbins of Chilliwack, B.C., has raced the Barkley three times, and came close to finishing in 2017.)

Around 40 runners get to race the Barkley Marathons every year, and the run through the woods and mountains of Tennessee starts when Lake lights a cigarette – one hour after the conch blows. Participants (and that’s what most will be — participants, not finishers) have 60 hours to navigate the five-loop course, which is not marked, and GPS devices are not allowed. In addition to running and navigating, runners must find books hidden around the course, tearing out the page corresponding to their bib number (which is different for each loop) – turning the ultramarathon into a brutal scavenger hunt.

If a runner can find each of the books (the number varies from year to year) and make it through all five laps, they will have covered about 100 miles and climbed around twice the height of Mount Everest in 60 hours or less. Finishing the first three loops in under 40 hours counts as a “Fun Run,” and is required to be allowed to attempt a fourth loop.

The Finishers

French photographer Alexis Berg and friend Aurélien Delfosse (a writer for the French sports newspaper L’Équipe) teamed up to put together The Finishers. As Berg says, he “had the crazy idea to make a very long trip through the U.S.,” and after pitching it to Delfosse, they set off on their journey, travelling around the country to talk to the 15 Barkley Marathons finishers.

Some of these athletes were easy enough to find and interview, while others had never spoken to the media, despite their monumental accomplishments in Frozen Head State Park. “If this book has any lasting meaning, it is in the depiction of these shadowy figures, seemingly ordinary yet extraordinary,” Berg says. “Each meeting at their home was, for Aurélien and me, a moment of grace, heart and intelligence. We will remember these moments all our lives.”

Berg and Delfosse endeavoured to share these meetings with the world through photography and text, and The Finishers is their final product. The book even includes a preface from Lake himself. Berg notes that this is far more than “just a sports book,” though, as it looks at the Barkley as a whole, from its inaugural running to its most recent, and uses the race to “explore our bodies, minds and the real or invented barriers that every day we decide to push back.”

The Finishers is available to purchase in French, and the English version is set to be released in March 2022 (although it can be pre-ordered now, and orders will be shipped by the end of 2021).

To learn more about The Finishers, click here, and to keep up to date on the 2021 edition of the Barkley Marathons (which we have reason to believe may be starting very soon), be sure to check in on the Canadian Running website and social channels.

(04/18/2021) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

Endurance athlete from Bristol is hoping to run 200 marathons in 100 days

In 2019, Nick Butter became the first person to complete a marathon in every country of the world.

The gruelling challenge took him from North Korea to El Salvador, across war zones and freezing temperatures. At one point he was bitten by a dog and mugged.

Nick's latest feat is unlikely to take him to such extremes, as he'll be running along the coast of Britain - but he will be attempting to complete two marathons a day.

Starting at the Eden Project on Saturday April 17, Nick will run for 14 hours each day to cover 52.4 miles (a double marathon), every day for 100 days.

He will run 5,240 miles in total, ending up where he began at the Eden Arena on Monday July 26.

I honestly don't know if I can do it but we're going to give it a go. He says.

Nick will be supported by a team of five people across three camper vans.

The first will hold his support team, keeping him safe and fed, the second will be his media crew and the third will be his home on the road. It will be driven by Nick's girlfriend Nikki and their dog Poppy will also join them.

When Nick ran across the world, he did it in aid of Prostate Cancer UK after a fellow ultra runner, Kevin Webber, was diagnosed with the disease.

He has so far raised more than £140,000.

For his 2021 challenge, he has set up The 196 Foundation. Its title comes from the 196 countries across the world and reflects all the needs across the planet.

Each year it will support one cause, voted on by the foundation's donors. It could be anything from buying a wheelchair for a family to building a school.

The 30-year-old hopes to be joined by other runners along the route. "We'd love to have some company and people to come and keep me company for the 100 days," Nick said.

"When I'm running for 11 hours a day, getting through 9,000 calories, I need all the help I can get".

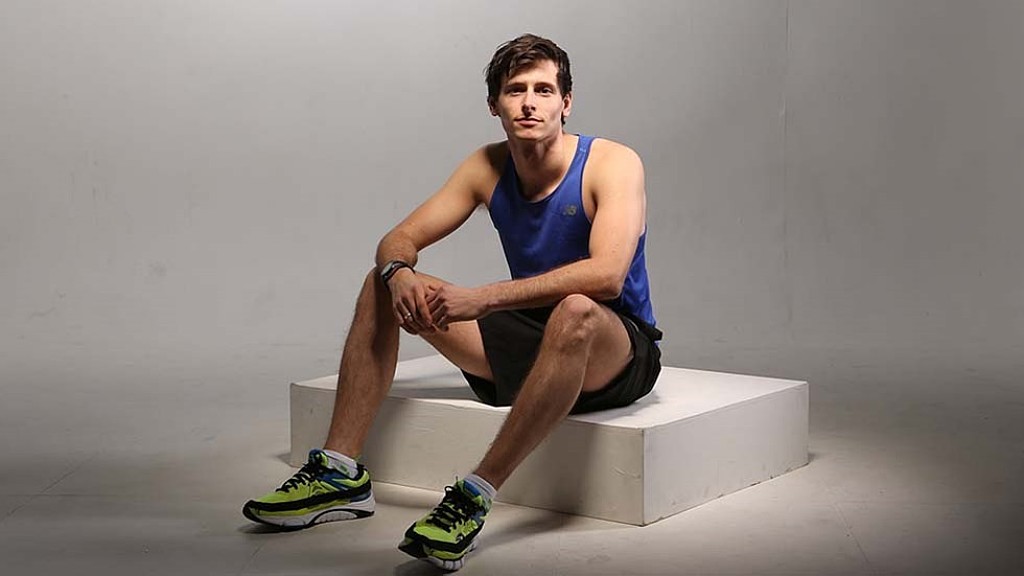

(04/16/2021) ⚡AMPDes Linden smashes the world record for 50k in her first ultra marathon

Des Linden’s elite marathon career has included two Olympic Games and a Boston Marathon win.

Tuesday morning, running on the Row River Road bike path along the northern bank of Dorena Lake near Cottage Grove, Oregon Linden became a world record holder.

In her first ultramarathon attempt, the 37-year-old from Michigan ran the 50K course in 2 hours, 59 minutes, 54 seconds to shatter the previous women’s record of 3:07:20 held by Great Britain’s Aly Dixon since Sept. 1, 2019.

“I thought it would take a disaster for it to not happen, but you get to the marathon distance and disasters are pretty common,” Linden said. “Then you extend that and you just don’t know. As confident as I was, it’s unknown territory. I was trying to respect it as much as possible.”

Linden averaged 5:47 per mile. She hit the 26.2-mile marathon mark in 2:31:13 and powered through the final five miles with the help of American men’s marathoner Charlie Lawrence, who paced Linden through the entire 50K.

“We held it together, but it got hard the last five but I knew we had that time locked away,” said Linden, who couldn’t see the clock at the finish line. “But I knew. We were crunching the numbers out there. I’m like ‘I gotta break 3 (hours) or else I’m going to have to do this again, like soon.’”

Linden said she’d been planning for this race for a couple of years and felt like the time was right to give it shot.

“The spring is totally free,” Linden said. “Without the major marathons it was like, let’s figure it out. And I think a small operation is a little bit better for trying to test the waters anyways, and with COVID, that’s how it has to be. We just tried to quietly do something and see how I liked the distance and how I measure up and if it’s something I want to pursue moving forward.”

The Row River Road course has been the site of several under-the-radar races the past year, including attempts by former Oregon stars Galen Rupp and Jordan Hasay to break U.S. half-marathon records. Neither were able to do what Linden did Tuesday.

“This is definitely one of the highlights of my running career thus far,” Lawrence said. “Being able to help a friend and probably my biggest mentor in the sport achieve a goal of hers and get a world record, is awesome.”

Linden finished seventh at the 2016 Summer Games in Rio de Janeiro and two years later won the Boston Marathon.

She finished fourth at the U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials in Atlanta in early 2020 before the pandemic shut everything down. She remains the alternate for the Tokyo Olympics this summer behind the three American qualifiers — Aliphine Tuliamuk, Molly Seidel and Eugene’s Sally Kipyego.

(04/13/2021) ⚡AMPby Chris Hansen

How to run efficiently on concrete, sand, dirt or trail

Running on pavement, cement, sand, dirt or trail have their unique challenges. It’s not simply about which running surface is better or more optimal since that answer is: “it depends” or “none of them is best.” In fact, your best bet is likely to mix up your running surfaces to change your loading and balance the way that you run.

“The human body adapts incredibly well to its situation,” says Jeff Knight, senior manager of digital product science for connected fitness at Under Armour and former running coach. “Basically, researchers have found that runners adjust to run with a softer stride over the firmer surface and a harder stride over the softer surface.”

When you switch things up, there are certain ways to optimize your running. Here’s what you need to know about different running surfaces and how to train on them for the best possible performance:

Concrete and cement are the hardest materials you’ll likely run on. If you observe most serious runners, you’ll notice they often eschew the sidewalk in favor of the shoulder of the road for this reason. On the flip side, sidewalks are going to be safer than running in the street when it comes to traffic. Some sidewalks have a dirt or grass medians you can take advantage of to give your feet a break.

This is also where finding a good road running sneaker comes into play. “A standard road shoe. The cushioning of a neutral running shoe options helps dampen the impact of each stride.

Ranked slightly softer than concrete sidewalks, running in the streets or on asphalt paths is better than trying to stay on sidewalks when it comes to running efficiently. As Knight points out, humans are amazingly adaptable, so if you live in a concrete jungle, don’t stress: You’ve likely developed a stride that takes hard surfaces into account. But when you can, hop onto the grass and run the side of a field or a trail: Research shows running in grass reduces the stress on your body compared to running on a more rigid surface.

Gravel trails and roads are firm and are good for running since they’re slightly softer than asphalt without much difference in the actual surface, unlike a dirt trail in the woods. But the loose layer of dust and gravel on top ultimately slows you down. “In Austin, Texas, we have a popular running trail in the middle of town that surrounds Ladybird Lake. That trail is made of crushed up bits of granite,” Knight says. “When I was coaching, we added 5–10 seconds per mile if we did a tempo run on that trail!”

So, while gravel may be optimal for long endurance runs compared to pounding the pavement for hours, don’t expect a PR. Similarly, rail-trails are the best for your joints thanks to their cushiness and lack of any technical navigation. Rail trails also tend to be flat and straight, with relatively few obstacles. Their surfaces are akin to those of gravel roads, but the flatness makes them more beginner-friendly, while gravel roads can easily get ultra-hilly.

Here, we’re talking about technical trails, not dirt roads. Trails are softer in general, but present runners with more ankle-biting obstacles, and because of this, your stability may suffer. On technical trails, Knight recommends swapping to a more trail-friendly shoe. “Usually, trail shoes offer a bit more stability and traction,” he explains. “If I catch a root or rock wrong, I am less likely to slide off that root and turn my ankle. To summarize, lots of roots the size of baseball bats or rocks the size of baseballs means switch shoes.” He notes that if you’re looking for speed on the trails, a dedicated trail shoe helps with that as well. “That extra bit of traction and stability may keep you safe when you start getting sloppy,” he adds. “No one is as sure-footed at the end of a hard trail session as they are at the beginning!”

Soft sand is by far the most challenging surface to run on, and it will fight you every step of the way. If you’re a beach runner, stick to the hard pack sand by the water’s edge and wear your trail shoes for more stability. You can head into the soft sand as an interval, since it will immediately make maintaining your pace much more challenging as an almost full-body workout.

But if you have a tendency toward rolled ankles, skip running on soft sand altogether: It might be nicer on your joints from a softness perspective, but the lack of stability makes it potentially dangerous. Surprisingly, one study showed that compared to running on a sandy soft surface, running on asphalt actually decreased the risk of tendinopathy in runners.

(04/12/2021) ⚡AMPby Molly Hurford

Over Half Of Ultrarunners Get Nauseous During Races; Here's Why

The list of issues and injuries that an ultrarunner can face while racing is lengthy. Blisters, chafing, cramps, muscle strains, knee pain, heat illnesses, and altitude sickness are just a handful of the possibilities. Perhaps none of these potential problems, however, are as prevalent and impactful during ultramarathons as nausea and vomiting. Indeed, practically every ultrarunner has their own tale of yakking on the side of a trail or into an aid station trashcan. For some, it's an unlucky one-off event, but for others, recurrent nausea consistently mars their ability to perform up to their expectations.

The reason so many ultrarunners get stricken with nausea is undoubtedly multi-faceted, and to be honest, there is not a cut-and-dry singular explanation. Still, we do have some clues as to why the prevalence of nausea and vomiting is up to 2-3 times more common in these races than much shorter distances. Let's take a look at what the research says about the possible culprits as well as some of the strategies you can try to deal with this troublesome symptom.

Just How Common Is Nausea?

Beyond the anecdotes, what exactly do we know about the prevalence of nausea in ultrarunners? Before we get to some data on that question, it's important to recognize that surveys used to gather this information quantify nausea differently. In addition, the occurrence of nausea is likely to vary with temperature and humidity, elevation, and the length of a race. As such, it's a bit foolhardy to throw out a single estimate of nausea and think that it applies to every ultrarunning scenario.

Caveats aside, some of the relevant data tells us that nausea incidence clearly increases with race duration. Dr. Martin Hoffman, professor emeritus in the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at the University of California, Davis, has overseen several studies on this topic, and in some cases, up to 6 out of 10 runners experience nausea during an ultramarathon. To give you some perspective, consider that around 10% of regular marathoners typically suffer from nausea.

Now, some of these cases of nausea are quite mild or transient, meaning they won't hurt performance much. Still, up to half of cases can be severe enough to impact ultrarunning performance. In fact, one of Hoffman's investigations found that nausea or vomiting was the leading reason for racers to drop out of the Western States 100-mile Endurance Run. During a regular 26.2-mile marathon, a runner suffering from nausea near the end of the race is likely to grit their teeth and finish. In contrast, the thought of having to suffer for another 20, 30, or 50-plus miles while feeling queasy is, very understandably, too much for some ultrarunners to cope with.

Multiple Causes

The puzzle of why nausea is so common during ultrarunning is difficult to solve, in large part because there are multiple physiological changes occurring simultaneously over the course of an ultrarace. It's also incredibly tough to match the demands of an ultrarace in a laboratory, so mechanistic studies looking at the origins of nausea during super-prolonged exercise are few and far between.

Even with the scientific uncertainty, we do have some decent guesses as to what's provoking the urge to spew in so many ultrarunners. During prolonged exercise, you secrete hormones like adrenaline and glucagon into your blood that allow your body to liberate fat stores, make glucose, and maintain your blood sugar levels. Arginine vasopressin, a fluid-conserving hormone, is also released so that you can reduce urine production. Blood levels of endotoxins (sort of invader molecules that seep through your gut's walls) and inflammatory molecules can also surge. And finally, you've got muscle breakdown products, like urea and creatine kinase, spilling into your bloodstream. All these substances can stimulate what's called the chemoreceptor trigger zone in your brainstem, which communicates with another brain region called the vomiting center.

Long story short, you've got a cocktail of substances circulating in your bloodstream that act as a potent trigger for nausea. The concentrations of all these substances tend to increase over time during prolonged exercise, which may help to explain why nausea becomes much more common in the latter half of ultraraces.

A Nervous Gut

The release of stress hormones like adrenaline can also occur even before you take your first official stride during an ultra. Throughout the history of sport, many athletes have been plagued by precompetition anxiety severe enough to induce vomiting. Bill Russell, perhaps the best center of all-time in the sport of basketball, reportedly vomited before many of his big games. There's also a moment in the Steve Prefontaine biopic Without Limits that perfectly captures what prerace nerves can do to even the most elite athletes. In the scene, Prefontaine is seen puking under the grandstands before his race against other running greats like Frank Shorter and Gerry Lindgren, even as the crowd chants his name.

These anecdotal accounts are also beginning to be backed by research. Just this year, two of my colleagues and I published an investigation that found anxiety to be associated with the occurrence of nausea in endurance race competitors. The study, published in the European Journal of Sport Science, had 186 endurance-trained individuals document their life stress and anxiety as well as the gut symptoms they experienced during one of their recent races. A subset of the subjects also reported how anxious they felt on race morning. Ultimately, racers who reported higher levels of general anxiety had over three times the odds of experiencing significant levels of nausea during competition. Further, those who reported lots of anxiety on race morning had over five times the odds of experiencing substantial in-race nausea.

These are correlations, so it's hard to definitively prove that these athletes' nausea issues were completely due to anxiety. That said, other lines of evidence support the idea that this relationship is at least partially cause and effect. Plus, most of us have had our own out-of-sport run-ins with gut distress stemming from worries and anxieties, whether they be from a first date, a medical procedure, or an interview.

Sweltering Heat and Altitude

Environmental conditions also play a major role in development of nausea during ultras. Some of the most prominent ultramarathons in the world (e.g., Western States Endurance Run, Badwater Ultramarathon, Marathon des Sables) are held in sweltry conditions. When researchers ask runners to exercise in the heat, the incidence of nausea can quadruple in comparison to exercise carried out at the same intensity in more mild conditions.

Besides the heat, another environmental factor that many ultrarunners deal with is altitude. Nausea is a well-known symptom of acute mountain sickness, with written accounts going back at least several hundred years. Add exercise to the mix, and you can start to understand why nausea is a big issue for competitors at races like the Hardrock 100 and the Khardung La Challenge, which has the highest elevation of any ultrarace in the world.

Fueling: A Delicate Balance

One other notable contributing factor to nausea is in-race fueling. The nutritional demands of ultrarunners can far outpace those of other athletes competing at shorter distances. For those ultrarunners who are looking to push the boundaries of what their bodies can do, they might end up consuming carbohydrate at rates of 60-90 grams per hour. That's roughly equivalent to 3-4 sport gels per hour! Even lesser amounts of carbohydrate (30-60 grams per hour), though, can pose a significant challenge to the gut's capacity to digest and absorb fueling.

In short, fueling during an ultramarathon often takes place on a knife's edge. Too little can lead to a bonk and even nausea if your blood sugar gets too low, while too much foodstuff can also provoke the gut and induce queasiness. With that in mind, it's critical that ultrarunners practice their fueling strategies multiple times throughout the weeks leading up to a race. Ideally, at least some of these gut-training sessions would be done at a pace similar to race-pace and in similar environmental conditions that an athlete expects to compete in.

Strategies to Quell or Avoid Nausea

Given all this information, you might be wondering how to best avoid the nauseous fate of so many ultrarunners. First, you should accept the fact that there is likely no ironclad way to completely eliminate the risk of nausea during an ultra. There are just too many potential causes. That being said, you do have the power to minimize your risk of being stricken with severe nausea. And for some athletes, it will be important to take a multi-pronged approach as opposed to relying on a single strategy. Below are my top five tips for reducing the odds of tossing your cookies during your next ultra.

Acclimate to the heat and altitude if your race is held under those conditions. Likewise, employ cooling strategies (e.g., drinking cool beverages, putting some ice in your cap or shirt, dousing yourself with cool/cold water, etc.) throughout a race that's held in sweltering conditions.

If you suffer from prerace nerves, try techniques like slow deep breathing or mindfulness. Better yet, consult with a sports psychologist.

Avoid both overhydrating as well as underhydrating. During a single-stage ultramarathon, some amount of weight loss is normal (due to the loss of energy stores), so you shouldn't be drinking so much that you weigh the same or more after a race as before the race. On the other hand, large body mass losses (e.g., >5%) may be a sign that you're underhydrating.

Train your gut! If you plan to push the boundaries of food and fluid intake during the race, of course it makes sense that you should practice your nutrition plan during some of your longer training runs. Much like other organs in your body, the gut is adaptable.

Try ginger. I'm generally not a purveyor of supplements, but if the above mentioned strategies don't do the trick for you, there is at least one nutritional product that has shown some anti-nausea properties in settings outside of exercise: ginger. To be specific, these anti-queasiness effects have been most often studied in nausea occurring during pregnancy, motion sickness, and chemotherapy. No supplement is without risk, and many products sold in the U.S. are of questionable quality, so anyone looking to use ginger supplements-or any other supplement for that matter-should do their research and consult with their healthcare provider as well.

(04/11/2021) ⚡AMPby Trail Runner Magazine

Season 1, Episode 2 of 'Run Around the World': A Docuseries About Chasing the Gnarliest Adventures

Mountain athlete Jason Schlarb and ultrarunner Meredith Edwards travel to Yunnan, China, with an ambitious plan to run a 55K trail race and establish the Fastest Known Time on 17,703-foot Haba “Snow” Mountain.

A dramatic ultramarathon racing culture is only rivaled by life on the frontier, where the pair experience a few nights on a rural farm before ascending a Himalayan-scale peak. Adventure runs high and success is elusive to the end.

Global travel may have slowed down this year, but running certainly did not—especially for the crew of Run Around the World. Crossing Switzerland on foot, running through the arts district of Mexico City, and overcoming the hurdles of a global pandemic made 2020 a year of growth.

Join the team—including world-renowned ultrarunners Jason Schlarb, Meredith Edwards, Ian Morgan, Diego Pazos, and Knox Robinson—for reflections on the benefits running brought to 2020.

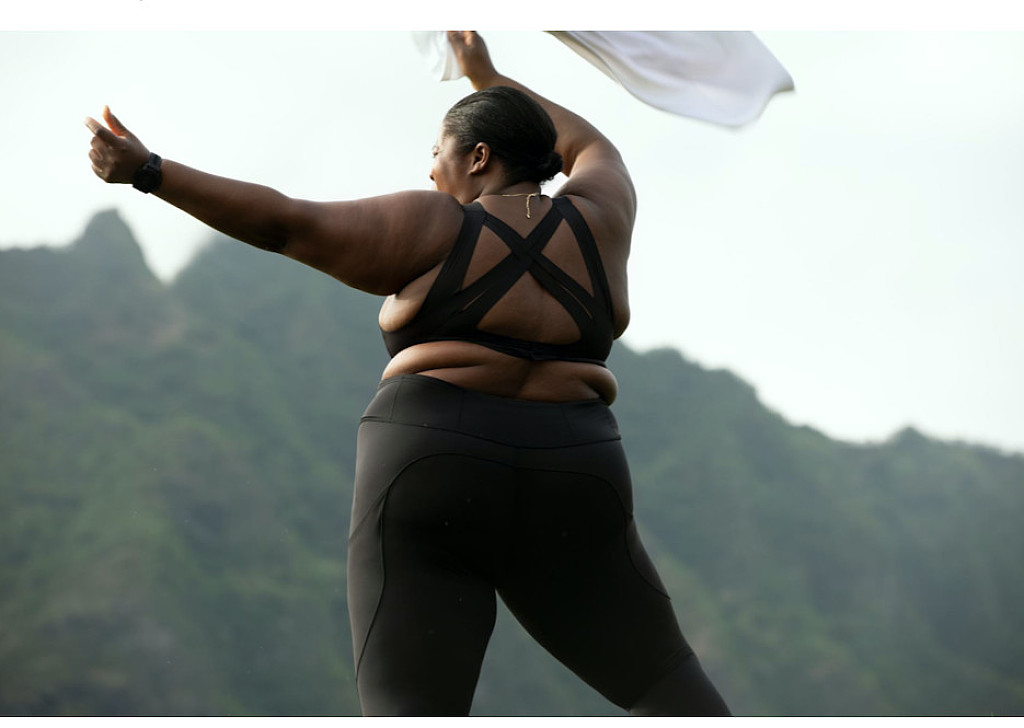

(04/11/2021) ⚡AMPLululemon's new campaign star has a body-inclusive message: 'Running is for everyone who has a body and wants to run'

Lululemon's newest ambassador and campaign star is going to great lengths to make running more accessible and body-inclusive.

The athletic apparel brand has tapped ultramarathoner, author, speaker and former Fat Girl Running blogger Mirna Valerio to front its new global "Feel Closer to Your Run" campaign and offer better representation of runners whose body types are typically overlooked within the fitness space. The Vermont-based Valerio tells Yahoo Life that she hopes to inspire and empower both people who have felt excluded by activities like running, and the brands that have the power to provide better quality gear for bigger bodies.

"Make no mistake: All kinds of people in all sorts of bodies want to be able to engage in movement that is meaningful to them, and they need apparel that fits, is functional and well-made," Valerio says. "There was this prevailing idea that plus-size folks didn’t do or want to do things like running, cycling, swimming, etc. But guess what? We’ve always done those things and have had to contend with ill-fitting apparel — because we’ve been forgotten and ignored — poorly constructed clothing that is not fit for any athletic activity, or if they do fit, pieces in limited colors and styles.

"When people see a person like me in a magazine or in a company’s marketing and advertising media [while] running or hiking or riding a bike, it’s easier for them to envision themselves doing the same thing," she adds. "It signals to them that they belong in that space too. And hopefully, it gives them a little push to perhaps try something they’ve always been curious about but could never really see themselves doing."

It was a health scare that gave Valerio herself that "little push" more than a decade ago. Though she's been a runner and athlete since high school, she fell into a three-year slump as she juggled the demands of grad school, a teaching career and family life.

"I wasn’t sleeping or taking care of myself, and it was a health scare connected to all of these things that prompted me to start running again," she says. "I’m never looking back!"

Assuming things are "rolling nicely" and she's injury-free, she runs about four or five times a week, leaving time for recovery days. When she's training for a race or marathon, she'll typically clock 30 to 45 miles a week — and sometimes 50 if her coach calls for it. Her next big challenge is the Trans Rockies 6-Day Stage Race in August.

"It’s six days of running the Colorado Rockies for about 120 miles, with 20,000 feet of vertical gain," she says. "It’s one of my favorite events ever, and I’ve managed to finish only once, so I’m going to go for it again this year."

And then there's the challenge of her new role in supporting Lululemon's diversity and inclusion efforts, and continuing to speak out about being active as a larger woman. Valerio is confident that the images of her hitting the trail in the campaign will serve as an inspiration, and invitation.

"You absolutely belong and are entitled to the fitness space," she says. "Running is for everyone who has a body and wants to run. Guess what? We all have bodies, so that means… "

(04/11/2021) ⚡AMPThe art and allure of 24-hour track racing

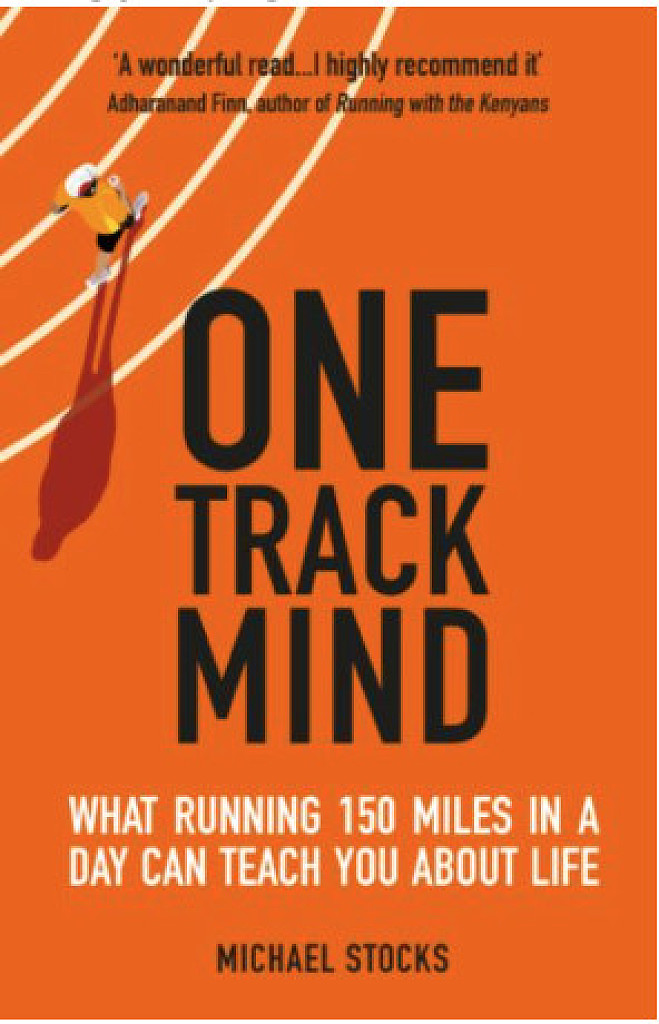

Author Michael Stocks gives his perspective on what it’s like to tackle the challenge of running for an entire day PLUS win a copy of his new book One-track Mind

Most us have experienced the feeling of standing on the start line of a track race, consumed by the mixture of tension, trepidation and anticipation of what lies ahead.

Not so many of us, however, will have stood on that start line knowing that the finish line is a full 24 hours away. Michael Stocks is one of those people and his new book One-track Mind: What Running 150 Miles in a Day Can Teach You About Life is a beautifully written account of everything involved in a challenge which test the limits of physical and mental endurance.

The race about which he writes is the 2018 edition of Self Transendence 24 hour, which takes place annually on the track in Tooting Bec, South London.

Rather than it being a case first past the post, when the hooter sounds after 24 hours victory goes to the person who has covered the greatest distance.

A place on the Great Britain team for the 24 hour World Championships was part of the incentive and Stocks manages to take the reader on just about every step of the incredible journey which unfolded along that 400m lap.

He will be back in action later this month at the Centurion Track 100 race in Ashford, with designs on breaking the V50 100-mile world record of 13:27:27 which is currently held by Russian Oleg Kharitonov.

So what is it that draws him to this particular strand of endurance running?

“In a way it suits my character and plays to one of my strengths which is that when I’m running I don’t really mind where I am – the act of running is the thing, if it’s a race,” says the man who has competed for both Great Britain and England.

“I do love going to beautiful places and running – and then I’m aware of my surroundings – but if I’m racing then really I don’t much mind where I am because it’s about the race and the running and the movements.

“I can honestly say that the fact that I was in the same place, running around and around wasn’t a big thing for me, though I did prepare mentally for that, which I think is really important.”

Stocks admits to being daunted ahead of the race getting underway but, as many long distance runners will attest, breaking the task at hand down into manageable chunks is as important as it is mentally helpful. 24-hour track racing is no different.

“I broke it down into half hours,” he says. “We know we need to drink every half hour, to eat every half hour and that really was my horizon. I just tried to stay in it and not think longer than half an hour.

“But then you’ve also got the change in direction every four hours, which was really important. I was also ticking off every 10k early on, so you kind of find those little goalposts, or goals and then I think the key when you when you get to them is not to think ‘okay I’ve done one hour but I’ve got 23 to go’ but rather to think ‘I’ve got one hour’ and to put that hour behind you.

“I almost had the sense of physically picking something up and placing it behind me and going ‘wow that’s great, I’ve collected that hour’.

“Yes it was daunting, but I really worked hard on staying in the present and thinking about what I’d done rather than about what was to come. It wasn’t successful all the time but on the start line I was confident that I had prepared well enough to get through it.”

One key challenge to overcome during a 24-hour race is, of course, running through the night. Stocks had never done it before and the experience was one of the most memorable and enduring points of the event.

“When I got through the night and the light came I suddenly realised how special the night had been,” he says. “I was really struggling a lot for a lot of it, and obviously you are late in the race, but there was this complete quiet and a sense of nothing outside. It creates this very unusual environment.

“I went through some of my worst stages and bad patches in the night but when I got to the end of those I remembered how the light looked brighter on the track because there was a wet sheen and you’ve got these massive spotlights, but you’ve got hardly anyone on the track because half of the runners had left by then.

“It was an almost surreal environment and I wanted to cling on to part of that quiet because it was such an unusual and special experience and I also had never run through the night.

“It would have been special in the mountains, too, but there was something about the track and the colours and the sense of quiet that just made it quite, quite special.”

Another special aspect of ultra marathon running, Stocks insists, is the community which surrounds it. From the athletes, to the support crews who literally keep their runners fed, watered and clothed, to the race organisers, the nature of the events create a unique sense of camaraderie.

“One of the things I really wanted to get across in the book is this excellent sense of community,” says the London Heathside runner. “When I left that track and the race it was almost heart wrenching because I felt there was such a sense of presence and positivity and community around the track.

“Everything from the organisers and the whole ethos of their races to the other crews who were supporting all the runners, not just their own runner.

“Paul [Maskell], who I was racing for the victory, we were just increasingly helping each other and encouraging each other and it’s really, really incredible.

“I think it’s probably the adversity that keeps you humble. There are just so many amazing people doing the sport.”

(04/10/2021) ⚡AMPby Athletics Weekly

8 reasons to give ultrarunning a try

Ultramarathons are pretty daunting, but you should run one anyway

This might be a tough sell, but you should run an ultramarathon. We know that the idea of running 50K, 100K or even more might not sound like something you want to do, but that could just be because you haven’t trained properly for it. After all, when you first started running, 5Ks, 10Ks and regular marathons probably sounded daunting, but you trained well and got through them. Not convinced? Here are a few more reasons to at least consider testing the waters of ultramarathons at some point in your running career.

Bragging rights

We don’t recommend doing anything simply for the attention it may bring you, but there’s no denying that ultrarunning will impress people. Most non-runners will be impressed if you tell them that you’ve run a marathon before, so you’ll blow their minds when you say you ran an ultra. A lot of people don’t even know what an ultramarathon is, and when you tell them how far you ran, they’ll think you’re amazing.

Mental challenges

Any long-distance race requires mental toughness, but the farther you go, the more you need it. Venturing past 42.2K will take you from a mostly physical endeavour to a mostly mental one, and that’s when you’ll learn more about yourself. Plus, you’ll become stronger mentally thanks to ultras, and you can apply that mental toughness to every other type of race you enter in the future, which will only help you on the course.

You could become obsessed with it

Some people might view this as a reason not to take up ultrarunning, but we think it’s definitely a reason to do it. As unattractive as running 100 miles might seem right now, after your first 50K, you shouldn’t be surprised when you feel the need to enter another ultra-distance race. Even if you tell yourself something like “Never again” during the race, we’re willing to bet that you’ll be asking “When can I do that again?” after you reach the finish line

More racing opportunities

If you add ultra distances to your list of options when picking your race schedule, you’ll only be increasing the number of racing opportunities in your life. Can’t find a marathon to race on a certain weekend this summer? If you’re open to running farther than 42K, you have more of a chance to fill that slot with an ultramarathon.

The community

Everyone who has done an ultra mentions the community and how great it is. The running community in general is awesome, but as you get into more and more specific groups within the sport, that we’re-all-in-this-together kind of feeling only intensifies. Also, since an ultra is such a huge undertaking, bonding with your fellow athletes is even easier than usual, because you’re all in for the same long and arduous experience.

It’s not over until it’s over

If you’re an athlete who races to win, then an ultramarathon is a great place for you, because no gap is insurmountable. You could be an hour behind the race leader, but in a run that lasts dozens of hours or even multiple days, that’s nothing, and it’s 100 per cent possible to chase them down and take the win. In a marathon, on the other hand, even just a 10-minute gap can be impossible to overcome.

It’s not permanent

Just like any kind of race, if you enter an ultra and don’t like it, you can leave that part of your life behind and never try it again.

It could be your forte

Working off that fact, there’s also the chance that you’ll fall in love with ultrarunning and actually be quite good at it. If you don’t try, you’ll never know. If you do try and you don’t like it, you can forget about it, but if you love it, then it can become your new go-to type of racing.

(04/04/2021) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

Entries for Comrades Marathon virtual race open

The world’s greatest ultramarathon is all set to stage the world’s greatest virtual event with runners from around the globe invited to participate on Sunday, 14 June 2020 with FREE entry to all South African runners who entered the 2020 Comrades Marathon.

The Comrades Marathon Association (CMA) last month launched its one and only officially sanctioned virtual race, ‘Race the Comrades Legends’ which promises to be The Ultimate Virtual Race.

GET A REAL MEDAL:

Participants who sign up for and complete the ‘Race The Comrades Legends’ are guaranteed a real finishers medal, together with the bragging rights of having completed the very first virtual event hosted by the CMA.

YOU ARE NOT ALONE:

It may seem new age to traditional Comrades Marathon runners but ‘Race the Comrades Legends’ is a great option for runners who for months have done training runs in isolation and no longer feel part of a close-knit running community. The ‘Race the Comrades Legends’ will provide a platform to engage with other runners throughout South Africa and the rest of the world as well as opportunity for family members to participate in the action, all with the reassurance of safety and convenience, while here in South Africa doing so within the constraints of the government’s National Lockdown regulations.

RACE AGAINST THE LEGENDS:

The CMA’s ‘Race The Comrades Legends’ is a running concept based on the stories of the greatest Comrades Legends in history. The official Comrades Marathon website will include an online functionality where runners can virtually compete, run with and compare with each other and the likes of Bruce Fordyce, Frith van der Merwe, Samuel Tshabalala and many others; where each participant creates their own personal story and on completion is able to earn a real medal.

CHOOSE YOUR DISTANCE - 5, 10, 21, 45 OR 90KM:

By creating an international virtual event with great public focus, based on a series of distances that various running legends have defined in their time, from the 5km to the marathon as well as the usual Comrades Marathon ultra, the CMA has effectively created a virtual mass-participation event for everyone to be a part of.

All that runners need to do is go to the Comrades website; register for ‘Race The Comrades Legends’; select their distance of 5km, 10km, 21km, 45km or 90km.

ENTER ONLINE:

The cost is R150 for South African runners and $25 for foreign athletes.

(03/26/2021) ⚡AMPComrades Marathon

Arguably the greatest ultra marathon in the world where athletes come from all over the world to combine muscle and mental strength to conquer the approx 90kilometers between the cities of Pietermaritzburg and Durban, the event owes its beginnings to the vision of one man, World War I veteran Vic Clapham. A soldier, a dreamer, who had campaigned in East...

more...Covid-Safe Medtronic Twin Cities Marathon Planned for October 3

The 2021 Medtronic Twin Cities Marathon is scheduled to take place as a reduced-size, COVID-safe event on Sunday, October 3, race organizer Twin Cities In Motion announced. The race, which was cancelled last year due to the pandemic, will limit marathon participation to 4000 runners, and COVID-safety measures will be in place throughout the event.

Registration for the 2021 marathon and other Medtronic Twin Cities Marathon Weekend events will open on Thursday, April 8. The marathon race runs from downtown Minneapolis to the State Capitol grounds in St. Paul.

“We’re optimistic about our ability to host an in-person event this fall,” Twin Cities In Motion Executive Director Virginia Brophy Achman said. “Our team has consulted medical and crowd science experts and worked closely with relevant public agencies to get to this point. That work will continue until race day as we properly calibrate the event to this fall’s public health situation.”

Participants can expect to see changes in the event from previous editions. While plans will be modified to match conditions later in the year, Twin Cities In Motion is telling participants to expect:

• Reduced field sizes in all marathon weekend races

• Mask-wearing requirements except while racing

• Social distancing requirements across the event weekend

• Spectating discouraged and spectator access limited in certain areas

• Reduced touchpoints when possible

“While there will be noticeable differences from pre-COVID days,” Brophy Achman said, “we plan to do all we can to maintain the spirit and energy of the event despite the constraints. The power of the event lies in the thousands of personal achievements that culminate at our finish line, and we’re excited to return those moments to our participants’ lives after all they’ve endured.”

The return of the event to streets of Minneapolis and St. Paul will also reestablish an important fundraising platform for dozens of local nonprofits who use the marathon to raise money and awareness of their organizations. Runners raised more than $1 million at the last in-person edition of the race in 2019.

“The TCM team is pleased to be preparing for an in-person race, because it’s the work we love to do,” Twin Cities In Motion President Dean Orton said.

“But we know the event is an important annual event in our community and we’re excited to be bringing back all the meaningful elements marathon weekend offers – from youth fitness to volunteer opportunities, from economic impact to the unique fundraising platform we offer.”

Registration for the marathon will be conducted online through the Twin Cities In Motion website, tcmevents.org, beginning at 10:00 a.m. CDT on April 8. Registration will also open for the following Medtronic Twin Cities Marathon Weekend events:

• Medtronic TC Family Events

• TC 5K, presented by Fredrikson & Byron P. A.

• TC 10K

Those events take place at the State Capitol grounds on Saturday, October 2. Registration will also open for the TC Loony and TC Ultra Loony Challenges – where runners participate in the TC 5K and TC 10K prior to running either the 10 mile or marathon the following day. The registration drawing for the Medtronic TC 10 Mile held on October 3 will be open in mid-summer.

More than 25,000 runners participated in the 2019 Medtronic Twin Cities Marathon Weekend, including more than 7,000 marathoners and more than 13,000 10 milers.

(03/24/2021) ⚡AMPMedtronic TC 10 Mile

Twin Cities In Motion originated in a grassroots effort to bring the energy and positivity of a community-wide running event to Minneapolis and St. Paul. From the first strides of the inaugural Twin Cities Marathon in 1982 through a rich history that saw the addition of events and programming to serve the community, TCM has inspired and empowered the Twin...

more...Former top tennis pro runs David Goggins's 4 x 4 x 48 ultra challenge

James Blake, an American retired professional tennis player who climbed as high as fourth in the world rankings in his career, recently completed ultrarunner David Goggins‘s 4 x 4 x 48 Challenge. Blake has been running for a few years, and since retiring from professional tennis, he has competed in a few races. The 4 x 4 x 48 was unlike any running event the former tennis pro had ever attempted before, though, and he was understandably exhausted after the two-day challenge.

4 x 4 x 48

The 4 x 4 x 48 Challenge is simple to explain, but far from easy to complete. Participants run four miles (6.4K) every four hours for 48 hours. This works out to 48 miles (77K) and a lot of short naps (or very little sleep at all) in two days. Goggins has turned this into an official event, and the 2021 edition ran from March 5 to 7.

“Goggins, thank you. I just finished my 4 x 4 x 48,” Blake said in a video he posted to Twitter. “Thank you for coming up with this challenge and putting me to the test. I dug deep plenty in my career to win tennis matches, but nothing like this.”

Blake said he had “no real rest, no real sleep” over the course of the 48-hour event. He added that he questioned himself during each of the 12 four-mile legs, but he pushed through those tough moments and and eventually made it to the finish two days after he started.

Not a new runner

While this was Blake’s first time running the 4 x 4 x 48 Challenge, it wasn’t his first time completing a running event of any kind. After retiring from tennis in 2013, he got into running, and in 2015, he ran the New York City Marathon. He crossed the finish line in 3:51:19.

In 2020, Blake ran 21.1K in the virtual NYC Marathon as part of a relay with running legend Meb Keflezighi. The pair of former professional athletes teamed up to raise funds for a couple of charities. Blake ran to support his own charity, the James Blake Foundation, which raises money for cancer research, while Keflezighi ran for the NYRR Team for Kids.

(03/20/2021) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

UTMB Is Back!

The world's most important trail race is driving forward-pandemic or not-and despite a tough year across the board, it seems to only be gaining steam.

While many races struggle to fill their 2021 entry slots, that was not a problem for UTMB, Chamonix, France's Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc-now six races from 40 to 300 kilometers, all of which take place during the final week of August in the legendary mountain town at the base of Mont Blanc. Despite a year off due to the global pandemic, interest in the race series remains very strong.

For the 16th time in a row, the UTMB races have sold out, with 10,000 runners slated across all the races. With the pandemic continuing to complicate international travel, the event's mix of nationalities has shifted, with more participants from within Europe and fewer from China and Japan. Despite the long-haul travel involved, U.S. interest in UTMB continues to grow, up slightly to 338 participants.

The UTMB organization is contemplating a number of changes this year, including a streamlined bib pickup system and wave starts with a few hundred runners in each block. Runners will have to wash their hands on their way into aid stations, with social distancing and masks being de rigeur. Shared food bins will be a thing of the past, and it's possible runner assistance areas may be altered or eliminated.

Despite the global uncertainty, 2021's marquee race around 15,774-foot high Mont Blanc looks to be among the most competitive trail races ever, on a par with 2017, which some observers have considered the most stacked trail race in the history of the sport. That year, France's Francois D'Haene edged out Catalonia's Kilian Jornet by 15 minutes, and Spain's Nria Picas won in a down-to-the-wire race, edging out Switzerland's Andrea Huser by under three minutes.

How did such a strong field coalesce? "It was really just organic. We didn't do anything specific to make it happen," says UTMB's Press Officer, Hugo Joyeux. One example is a post by three-time UTMB winner D'Haene, who asked on Instagram, "Who's coming back to take part in the party? I'll be there!" D'Haene went on to tag his top challengers, gently teasing them into showing up at the starting line next to the Mayor's office in the old part of Chamonix this August 27th. Most are in, with Jornet notably absent as he continues to reduce his trail-racing schedule to focus on mountaineering objectives.

The USA's top runners didn't need a social media ribbing from D'Haene to add the race to their calendars. Starting for the women will be Courtney Dauwalter, aiming for a second consecutive UTMB win, along with Katie Schide, Kaytlyn Gerbin, Brittany Peterson and Stephanie Howe. Schide, second in the CCC race in 2018, and 6th in the UTMB in 2019, currently lives in the south of France, in the maritime Alps region, and is easily the most experienced European racer among the U.S. women's elite entrants.

"UTMB reliably draws the most competitive field of the year," says Schide. With top runners coming out of an usual pandemic year-plus, Schide is eager to go head-to-head. "Time trials and personal challenges are fun, but racing is where I'm really able to find the absolute limits."

The U.S. men's delegation is equally competitive-with a dose of angst added, too. In 18 years, no American male has ever won UTMB. It's long since started to be a topic of discussion. Flagstaff, Arizona's Jim Walmsley has started UTMB twice, finishing fifth in 2017 and dropping out in 2019, while Tim Tollefson, from Mammoth Lakes, California, has had four starts, with two third-place finishes. In 2018, he took a serious fall, fileting a quadricep-yet he still managed to run another 90 kilometers before having to drop. The wound ended up requiring eight stitches. The following year, he showed up at the starting line feeling ill, and eventually dropped.

About 2021, Tollefson says, "It's going to be another barn burner," revealing that comparisons with others toeing the start line has been something with which he has struggled over the years. "Contrary to what most may believe, anxiety over who is or isn't in a field has tormented me historically," he explains. "Insecurities over training, fraudulent thoughts of belonging, self punishment and disrupted sleep were commonplace."

For Tollefson, that mix of emotions has added up to sleepless nights and high levels of stress. This past year, counseling has offered him a better perspective. In addition to the usual training, he's working on "becoming mindful in life and believing that the quest to become the best version of myself-which is not dependent on the love, acceptance or applause of anyone else-is the ultramarathon worth mastering."

"I left the Chamonix valley in 2018 full of anger, guilt and shame. What brewed over the next 12 months was a toxic cocktail of unchecked emotions and coping strategies," says Tollefson. "No matter how much I lied to myself and others, I simply did not want to be there."

How will he feel, arriving in Chamonix valley this August? "For the first time in years, the thought of being back in the valley, truly present, is beginning to excite me."

The restart of UTMB this summer is welcome news to this Alps tourist hub, which historically welcomes close to 100,000 guests for the race series at the close of each August. When last August's races were cancelled, the organization refunded 55 percent of the entrance fees for the 10,000 registered runners. The split created grumblings on social-media platforms. Meanwhile, the staff of 30, which includes UTMB's international races, suffered its own share of disruptions. They began working from home starting with the first French lockdown on March 17th, and didn't return to the office until this past December. They now operate with 50 percent of the staff in the office-masks required.

(03/14/2021) ⚡AMPby Trail Runner Magazine

Des Linden will be looking to break the 50K world record next month

Boston Marathon champ Des Linden is officially entering the world of ultramarathoning, as she has announced that she will attempt to break the 50K world record next month.

In mid-April at an undisclosed location (details are intentionally vague because of pandemic concerns), she will take a crack at U.K. runner Aly Dixon‘s record of 3:07:20, which she set in 2019.

In October, Linden invited runners to participate in a challenge she called Run Destober, in which each day, participants ran the number of kilometers (or miles) that corresponded to the date. For example, on October 1 participants ran one kilometer, and on October 31 they ran 31. In total, the challenge worked out to be either 496K or 496 miles.

While this was a great way to engage the running community, it was also an effective way for Linden to slowly ramp up her weekly mileage and see how her body responded to the increased volume.

Back in August, Linden also expressed interest in ultramarathoning when she said in an interview that the Comrades Marathon and UTMB were on her bucket list. It is unclear whether this run will take place on the road or the trails, but either way, her result next month will be a good indicator of how she’ll fare when she finally decides to tackle the trails.

The headphone company Jaybird is supporting Linden during her record-breaking attempt, and the official announcement was made on their Instagram page on Tuesday. In order to beat Dixon’s time, Linden will need to maintain a pace of 3:44 per kilometer.

Given that she ran approximately 3:22 per kilometer for her marathon personal best of 2:22:38, this pace doesn’t seem unattainable, but of course, in a 50K race, it’s hard to say what could happen in the last 8K. We will be waiting for her result in April, and if she accomplishes her goal we expect to see Linden attempt more ultras in the future.

(03/10/2021) ⚡AMPby Brittany Hambleton

Pam Reed Becomes the 17th Person to Finish 100 100-Mile Races. And She Has Some Advice for You

The ultrarunning legend shares wisdom gleaned from nearly three decades of running 100-milers.

Ultrarunning legend Pam Reed just celebrated her 60th birthday as part of one of the most exclusive clubs in running: the group of runners who have finished 100 official races of at least 100 miles.

According to ultrarunning historian Davy Crockett, Reed is the 17th person in recorded history to have completed 100 100-milers in their lifetime (it was recently discovered that Frederick Davis III also reached this mark in December 2019, making him the 18th member of this group). Reed achieved the impressive mark at the Grandmaster Ultras in Littlefield, Arizona, on February 6, where she finished the 100-miler in 25:02:54—first woman, and third overall.

To clarify, this honor is the completion of 100 official races that were at least 100 miles. This means that even if Reed completed 491 miles at an event, like she did at the 2009 Self-Transcendence Six-Day Race, she was only credited with a single 100-miler. Though you may think Reed wishes that the extra mileage had added up to reaching her title sooner, she wouldn’t trade away any parts of her storied career.

Reed has run ultras, ranging from 50K to multi-day races, for three decades. Among her many accolades, she was the first woman to outright win the Badwater 135—a feat she achieved in 2002 and repeated in 2003.

In 2019, Crockett mentioned to Reed that she was at 89 total 100-mile finishes. That surprised her, because she assumed she had already hit that mark.

“In my mind, the way I counted, I thought I had done it,” Reed told Runner’s World. “But I counted 220 miles that I ran at a 48-hour race as two [100-milers] or my six-day race as four. But they didn’t count, and when I found out I was 11 away from something only a handful of people had done before, I decided to go for it.”

So Reed set the goal of reaching the 100 mark before her 60th birthday in February 2021, and decided to do 10 100-milers in 2020. In addition to a handful of 50Ks, a 60K, a 100K, and a half Ironman, this was going to be her biggest year ever. Previously, the most she had done five or six in a year, with other distances sprinkled in as well.

As you can imagine, Reed’s year was turned upside-down as the pandemic wiped away many of the races she wanted to do. Having to adapt, she signed up for virtual races, running courses she and her friends mapped out near in Jackson, Wyoming, where she’s based. She ran from her home to the Grand Tetons for races like Hardrock Hundred and Wasatch 100. She also did 100-mile races, such as Bryce Canyon Ultras and the Javelina Jundred, in-person when she could.

“I don’t really plan that much,” Reed said. “I’m not a great planner. It just kind of happens, and if a race happens, I go for it. I made courses if I had to, calling my friend who made a five-loop course climbing up a mountain five times. I don’t want to do this five times. I can be a whiner, but I did it and 100-milers are hard no matter what way you do them.”

For her century race, she planned to do Arrowhead 135, a challenging winter race in northern Minnesota in February. However, that was canceled because of the pandemic, so she opted for the Grandmasters Ultra for her 100 crown.

And Reed had a chance to win the race—she was leading after 39 miles, but a few runners took a wrong turn on a 5.5-mile loop, and the course was adjusted after Reed had already completed the section. She was passed and took third overall, but that didn’t spoil her big day. When she came across the line, she received not only her belt buckle, but also a plaque and a cake commemorating her 100th 100-miler.

“I’m so blessed to have the body that can keep doing this,” Reed said. “It’s cool that only so many people have ever done this. I’m really proud of it. My goal in life is to be able to run until I die and I am 100-percent serious when I say that. I just want to live my life to the absolute fullest, and, in my opinion, that is being able to run, skate ski, swim, bike, and get outside as long as I can.”

As the 60-year-old looks back on fondly on her race resume and the different challenges that each race presented, we also asked her what wisdom she might have for budding or experienced ultrarunners who dream of reaching the heights that Reed has in her career.

Here is what she had to say.

Energy powers her: I’m Finnish, a quarter Swedish, and a quarter Norwegian—I think there’s something to that. I know a lot of Finnish people, and they are hardcore. Living in Jackson, I’m surrounded by hardcore people. I just have a lot of energy, so I always want to be doing things. That really helps me do what I do.

Do a lot of modalities: I do a lot of hot yoga, often twice a day. I do acupuncture, I get massages regularly, and when things are hurting, I work on them immediately. I used to be a gymnast, and I could put my chest on the floor between my legs. Now, I don’t need to do that. I adjust my yoga to fit what I want to do as a runner. I’m intuitive about what I do and do not do.

Don’t wear so many clothes: I can’t tell you how many times I start with more clothes than I needed. I’ve learned from winter races that you can’t sweat or you’ll get colder, and I needed to find a happy place. Turns out in the summer, that’s a cotton shirt, arm sleeves, and men’s nylon socks.

Learn to fuel properly: I learned that I’m best running with Tailwind, nut butter, and Justin’s Almond Butter. I use GU gels when I race Ironmans, but I usually can’t get those down in a 100-miler. Except for one time at Leadville, I started throwing up eight hours into the race, and I didn’t stop until I took a GU with about 13 miles to go.

Listen to your body above anything else: Okay, don’t necessarily try this at home, but I don’t always listen to what experts tell me. I listen to my body. That’s not to say I ignore experts. But it’s also okay, in my opinion, to investigate. You should do that. Everyone is different, and you have to figure out what works for you. Don’t hurt yourself, but try things like massages or hyperbaric chambers. Do your research first, of course.

Fail and learn: Failing is learning. No one race is the same and not all races will be perfect. We all have to learn again and again.

(03/06/2021) ⚡AMPby Runner’s World

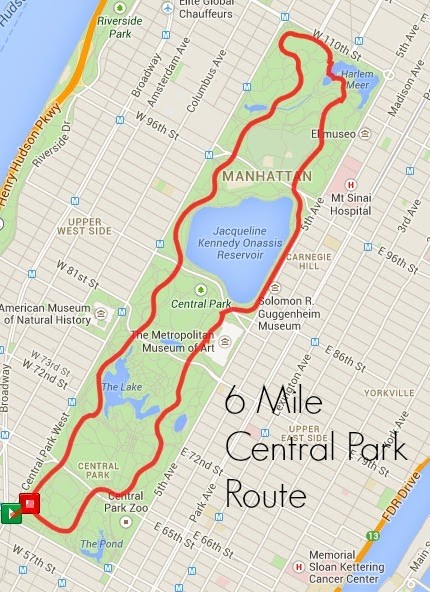

The Six-Mile Central Park Loop Has Been Renamed After Running Pioneer Ted Corbitt

“The Father of Long-Distance Running” receives a much-deserved honor.

Central Park has long played a significant role in New York City’s running culture. Runners who visit the city carve out time for a few miles in the famous park. Those who call New York City home circle the loops during long runs. It is home to the New York City Marathon finish line.

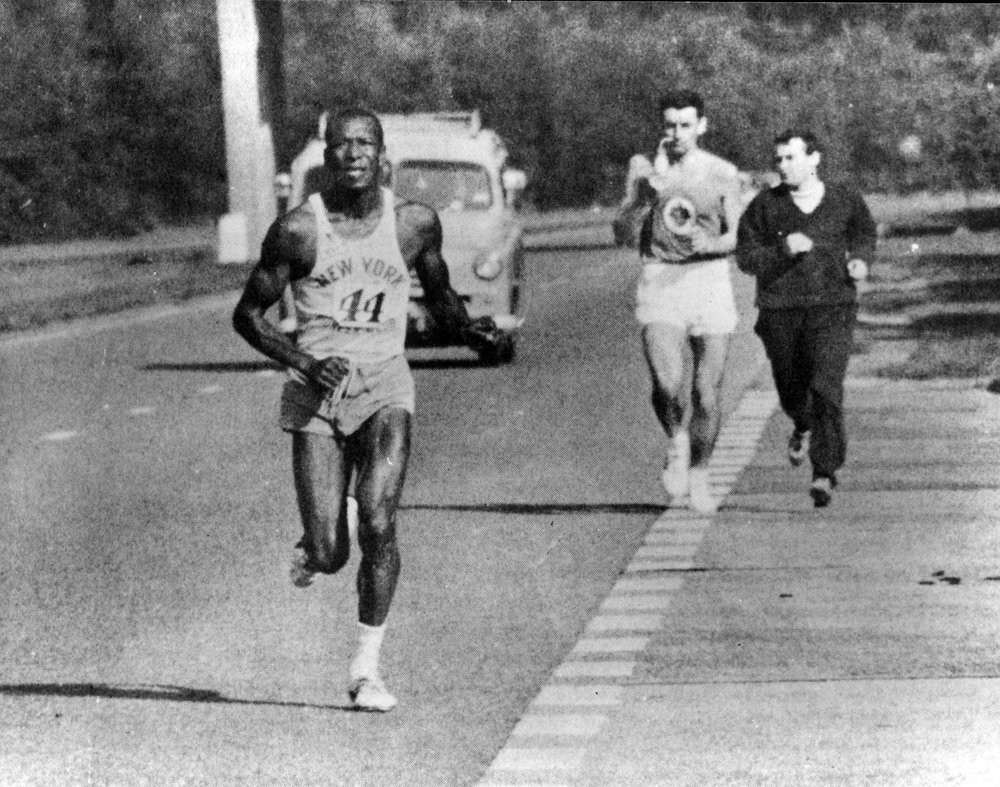

And now, the most famous running loop within the 51-blocks long park is named after running pioneer and Olympian Ted Corbitt.

The six-mile route—now called the “Ted Corbitt Loop—will feature six landmark street signs commemorating Corbitt along the path, and will have a NYC Parks-branded sign at the base of Harlem Hill at 110th St. and Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard in Harlem.

“As an avid runner, I am incredibly proud to commemorate the contributions of a man that inspired me and countless others to push through boundaries and live more abundantly,” NYC Parks Commissioner Mitchell Silver said in a statement. “It is an honor to celebrate Black History Month this year by shining light on Ted Corbitt’s influence and advocacy for underrepresented groups in running and beyond. May his legacy and pioneering spirit live on to inspire the next generation of runners to strive for greatness, progress, and peace.”

The move comes as NYC Parks continues to work toward ending systemic racism and providing a better representation of all races. Part of that is honoring Corbitt, a true pioneer of the sport who earned the title, “the father of long-distance running.”

In a 50-year running career, Corbitt ran 199 marathons and ultramarathons. He was the first Black American to represent the U.S. in the Olympic marathon in 1952, and he wore the No. 1 bib in the first-ever NYC Marathon in 1970. He was the founding president of NYRR and was an inaugural inductee into the National Distance Running Hall of Fame. These are still only some of his accomplishments.

His legacy is one that should be heralded in the Mount Rushmore of running. His name on the famous Central Park loop is a start.

“My father and other men and women volunteers worked tireless hours to help invent the modern day sport of long distance running,” Corbitt’s son Gary Corbitt said in a statement. “Many of the innovations in the sport were started in New York during the 1960s and early 1970s. This naming tribute celebrates all these pioneers.”

(02/28/2021) ⚡AMPby Runner’s World

UTMB announces stacked fields for 2021 races

The 2021 edition of the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB) is still months away, but the fields for the August race are officially set. After UTMB organizers cancelled their event in 2020 due to COVID-19, any race would have been exciting to watch this year, but fans will be treated to a pair of stacked lineups in the men’s and women’s fields. With six former UTMB champions and many other world-class runners set to race in Chamonix, France, later this year, the storied 170K ultramarathon looks like it will be can’t-miss action.

The women’s race

Former UTMB champs Courtney Dauwalter of the U.S. and Francesca Canepa of Italy headline the women’s race. Dauwalter is the reigning UTMB champion after her win in 2019, which was her first time running the race. She is widely recognized as one of the best ultrarunners on the planet, and she will be extremely tough to beat in Chamonix.

RELATED: UTMB adds to international race lineup with Thailand ultramarathon

Canepa won the women’s UTMB crown in 2018, and she also placed second in 2012. Other former top UTMB finishers on the start list for 2021 include Japan’s Kaori Niwa (fourth in 2017 and the winner of the 2019 Oman by UTMB 170K ultramarathon), Uxue Fraile Azpeitia of Spain (three-time UTMB podium finisher) and Beth Pascall of the U.K. (fourth- and fifth-place finishes in 2018 and 2019).

Multiple world record holder Camille Herron is also set to race in Chamonix. She has won ultramarathons around the world, including the Comrades Marathon in South Africa in 2017 and the Tarawera 100-miler in New Zealand in 2019, and she certainly has what it takes to win or place high in the overall UTMB standings.

Ailsa Macdonald is the lone Canadian in the elite UTMB women’s field. With big results like her wins at the Golden Ultra in B.C. in 2018 and the Tarawera 100 in 2020, Macdonald is another podium threat. She also has experience in Chamonix, having placed sixth in the UTMB’s CCC 101K ultra in 2019.

The men’s race

On the men’s side, there are four former UTMB winners: Pau Capell of Spain (winner in 2019) and French athletes François D’Haene (won in 2012, 2014 and 2017), Ludovic Pommeret (won in 2016) and Xavier Thévenard (won in 2013, 2015 and 2018). The past eight UTMB crowns belong to these four men, and they’re all capable of extending that streak to nine straight this year.

Jim Walmsley and Tim Tollefson are the top two American hopes on the men’s side. Tollefson made the UTMB podium in 2016 and 2017 with a pair of third-place finishes, while Walmsley has only raced in Chamonix once, running to fifth place. As Walmsley showed recently in a 100K world record attempt (he ran 6:09:26, missing the record by 12 seconds), he is in incredible shape this year, and while August is still months away, he has to be considered a favourite.

Also on the start list is the U.K.’s Damian Hall, who finished in fifth at the 2018 edition of UTMB. Hall is coming off a fantastic year of running that featured several prominent FKTs, and although he hasn’t raced in a while, he shouldn’t be counted out come August.

Finally, Canada will be represented by Mathieu Blanchard. Born in France, Blanchard now lives and trains in Montreal. He has raced in Chamonix before, running to a 13th-place finish in 2018, and in 2020 he ran onto the podium at the 102K Tarawera Ultra race.

UTMB is set to run from August 23 to 29, 2021.

(02/27/2021) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

Six former UTMB champs are on the start lists for the famed ultramarathon's comeback in August

The 2021 edition of the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB) is still months away, but the fields for the August race are officially set. After UTMB organizers cancelled their event in 2020 due to COVID-19, any race would have been exciting to watch this year, but fans will be treated to a pair of stacked lineups in the men’s and women’s fields.

With six former UTMB champions and many other world-class runners set to race in Chamonix, France, later this year, the storied 170K ultramarathon looks like it will be can’t-miss action.

The women´s race

Former UTMB champs Courtney Dauwalter of the U.S. and Francesca Canepa of Italy headline the women’s race. Dauwalter is the reigning UTMB champion after her win in 2019, which was her first time running the race. She is widely recognized as one of the best ultrarunners on the planet, and she will be extremely tough to beat in Chamonix.

Canepa won the women’s UTMB crown in 2018, and she also placed second in 2012. Other former top UTMB finishers on the start list for 2021 include Japan’s Kaori Niwa (fourth in 2017 and the winner of the 2019 Oman by UTMB 170K ultramarathon), Uxue Fraile Azpeitia of Spain (three-time UTMB podium finisher) and Beth Pascall of the U.K. (fourth- and fifth-place finishes in 2018 and 2019).

Multiple world record holder Camille Herron is also set to race in Chamonix. She has won ultramarathons around the world, including the Comrades Marathon in South Africa in 2017 and the Tarawera 100-miler in New Zealand in 2019, and she certainly has what it takes to win or place high in the overall UTMB standings.

Alisa McDonald

Is the lone Canadian in the elite Camille Herron is also set to race in Chamonix. She has won ultramarathons around the world, including the Comrades Marathon in South Africa in 2017 and the Tarawera 100-miler in New Zealand in 2019, and she certainly has what it takes to win or place high in the overall UTMB standings.

The men’s race

On the men’s side, there are four former UTMB winners: Pau Capell of Spain (winner in 2019) and French athletes François D’Haene (won in 2012, 2014 and 2017), Ludovic Pommeret (won in 2016) and Xavier Thévenard (won in 2013, 2015 and 2018). The past eight UTMB crowns belong to these four men, and they’re all capable of extending that streak to nine straight this year.

Jim Walmsley and Tim Tollefson are the top two American hopes on the men’s side. Tollefson made the UTMB podium in 2016 and 2017 with a pair of third-place finishes, while Walmsley has only raced in Chamonix once, running to fifth place.

As Walmsley showed recently in a 100K world record attempt (he ran 6:09:26, missing the record by 12 seconds), he is in incredible shape this year, and while August is still months away, he has to be considered a favorite.

Also on the start list is the U.K.’s Damian Hall, who finished in fifth at the 2018 edition of UTMB. Hall is coming off a fantastic year of running that featured several prominent FKTs, and although he hasn’t raced in a while, he shouldn’t be counted out come August.

Finally, Canada will be represented by Mathieu Blanchard. Born in France, Blanchard now lives and trains in Montreal. He has raced in Chamonix before, running to a 13th-place finish in 2018, and in 2020 he ran onto the podium at the 102K Tarawera Ultra race.

(02/24/2021) ⚡AMPby Ben Snider-McGrath

North Face Ultra Trail du Tour du Mont-Blanc

Mountain race, with numerous passages in high altitude (>2500m), in difficult weather conditions (night, wind, cold, rain or snow), that needs a very good training, adapted equipment and a real capacity of personal autonomy. It is 6:00pm and we are more or less 2300 people sharing the same dream carefully prepared over many months. Despite the incredible difficulty, we feel...

more...The history of black running in America

Ted Corbitt laid the basis for measurement of road running courses in the USA and was the founding president of NYRR (New York Road Runners. He was black; and many assume he was the first black American endurance runner of historic importance.

Corbitt (1919–2007) was a formidable figure in long-distance running, but he was far from the first – or the only – notable African American long-distance runner. The history of black running in America dates back to at least the 1870s and is both rich and profound.

Gary Corbitt, Ted’s son, has spent years researching and writing about black American running and bringing many untold stories to life. He founded the Ted Corbitt Archive to preserve and highlight some of the amazing and almost forgotten stories of black American runners, coaches, clubs, teams, events, supporters and leaders.

“My dad always told me he wasn’t alone – that there were other great black American long-distance runners,” says Gary. “I didn’t know how rich the story was until I started looking into it myself.”

Using books, articles, and a huge amount of primary documents, Gary created a “Black Running History 100 years (1880–1979)” timeline that spanned 100 years (1880–1979). “The work is not finished yet,” he says. “I have probably captured 75 percent of what is known from this 100-year period.”

He was inspired by a story his father told him about a letter he received from a young black runner. “The runner wrote that he wished he had known about my dad when he was in school and the coaches steered him away from long-distance running and into sprints,” said Gary. “If he’d had a black long-distance runner like my father as a role model, things might have turned out differently. I want today’s young black runners to know that they are part of a rich history and that they have many role models.”

Here are just a few of the highlights from the Chronicle. See tedcorbitt.com for more.

Frank Hart and the marchers (pedestrian) movement

In the late 1870s the most popular sport in the United States – and a few other countries – was pedestrianism: multi-day running and walking competitions over hundreds of miles, often on covered lanes in front of large crowds. Participants came from all walks of life and one of the most successful was a young black runner named Frank Hart (above, left). Born Fred Hichborn in Haiti in 1858 he moved to Boston as a teenager, worked as a grocer, and started running long distance runs to make extra money. He changed his name when he became a professional “walker” (pedestrian).

Hart won the prestigious O’Leary Belt Six Days at Madison Square Garden in 1880 completing an astonishing 565 miles – a world record. The runner-up, William Pegram, was also black. Hart’s success earned him fame and fortune; his image was featured on trading cards (the forerunner of baseball cards) nationwide, and he likely made over USD 100,000 in his lifetime thanks to the legal gambling that was at the heart of the sport and even allowed participants to wager on themselves.

Unfortunately Hart also endured racism, including heckling and physical harassment from viewers and snubs and slurs from his rivals. In the late 1880s baseball – with its rigid racial segregation policy – ousted walking in popularity. As an excellent all-round athlete, Hart joined a “Negro League Team” for a few years.

The spirit of the march (pedestrian) era inspired Ted Corbitt, who ran (and won) many ultra runs, completing 68.9 miles in 24 hours at the age of 82. “My father talked about running 600 miles in six days and walking 100 miles in 24 hours,” said Gary. “These were milestones from the marchers’ days, the meaning of which I only fully understood much later, after his death.”

Early NYC running clubs and marathon runners

Several black running clubs in NYC in the early 1900s, including the Salem Crescent Athletic Club, St. Christopher’s Club of NY, and the Smart Set Athletic Club of Brooklyn, showcased the talents of a generation of black runners at sprint to marathon distances.

In 1919, Aaron Morris of the St. Christopher Athletic Club finished sixth in the Boston Marathon in 2:37:13, making him the first known African American to run the race. At the 1920 Boston Marathon, Morris’ teammate Cliff Mitchell finished eighth in 2:41:43. Mitchell finished 13th in Boston in 1921, and another St. Christopher runner, John Goff, finished ninth that year in 2:37:35.

The New York Pioneer Club, which was founded in Harlem in 1936 by trainer Joe Yancey and two other black men, campaigned to give everyone interested and qualified regardless of race a chance. “It was an integrated running team that preceded the integration of professional sport,” says Gary Corbitt. Ted Corbitt joined the Pioneer Club in 1947 and in 1958 he and other members formed the core of the New York Road Runners.

Marilyn Bevans

Opportunities for female long-distance runners were few before the early 1970s. NYRR always allowed women as members and in its events, but the Boston Marathon excluded women until 1972, the same year that a women’s 1500m (less than a mile) run was added to the Olympic programme.

In the 1970s Marilyn Bevans of Baltimore emerged as the first competitive modern black American marathon runner. She was the first black American to win a marathon – the Washington Birthday Marathon in Maryland in 1975. She finished fourth in the 1975 Boston Marathon with a time of 2:55:52, making her the first black American to win a marathon run in under three hours. She completed a total of 13 marathons under three hours. Bevans later became a coach and is now in her 70s.

(02/24/2021) ⚡AMPby Gordon Bakoulis

The Cold, Hard Reality of Racing the Yukon Arctic Ultra

Temperatures were brutally low at this year’s running of the 300-mile competition, and one frostbitten competitor may lose his hands and feet. Is this just the price of playing a risky game, or does something need to change?

Roberto Zanda left the Carmacks checkpoint of the Montane Yukon Arctic Ultra just before noon on February 6. He was at least 150 miles into the 300-mile race—he’d already been slogging down a dogsled trail through the Yukon backcountry for more than five full days. Temperatures had plunged below minus 40 Fahrenheit on the first night out of Whitehorse, the small Yukon city where the race began; along the race course, temperatures consistently ranged from the minus 20s to the minus 40s.