Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

Search Results for Ultra

Today's Running News

2021 Western States 100 Women’s Race

With three women inside the top-10 overall, some of the fastest times ever run on the course, and tight competition wire to wire, the top-10 women changed Western States 100 history—and women’s ultrarunning history—this weekend.

Numerous international women chose to make the trip to the States for States. Among them were Beth Pascall (pre-race interview) from the U.K., who’d spent the past 10 weeks in the U.S. after running the Canyons 100k. Ragna Debats (pre-race interview), who is from the Netherlands but who lives in Spain, was present, running her first Western States, as was Ruth Croft (pre-race interview), all the way from New Zealand, lining up for her first attempt at 100 miles. On the domestic side, defending champion Clare Gallagher (pre-race interview), Brittany Peterson (pre-race interview), Addie Bracy, Camille Herron, and so many more women all hoped to have a good run. What ensued was tight racing from start to end with impressive performances all around.

The race started under clear skies, a setting moon, and a comfortable 53 degrees Fahrenheit. Fast out of the gate, France’s Audrey Tanguy was the first over the Escarpment, mile 3.5, followed a minute back by Herron. Gallagher, Pascall, and Bracy filled out the top five just two minutes back from Tanguy. All the women received enthusiastic encouragement from the resident Yeti of Olympic Valley who’d come out to spectate.

By Red Star Ridge at mile 15, Pascall had moved to the front. After finishing just off the podium in fourth in 2019, she was eager to move up in the final standings and wasted no time making her intentions known. Tanguy, Bracy, and Gallagher gave chase, all within 90 seconds, and a long string of women trailed just as closely behind.

By Robinson Flat at mile 30, we understood that Pascall meant business. Looking relaxed, she’d moved to just three minutes off of course-record pace. Bracy and Debats continued to chase, holding the gap to within five minutes. In the next eight miles, Pascall went from three minutes over record pace to nine minutes under it. She flew in and out of the Dusty Corners aid station in a minute.

Halfway through, many of the top women were looking comfortable. Pascall even claimed that it didn’t feel too hot. Still, the heat must have been affecting her as she slowly lost some time on the course-record pace. Debats continued a steady march forward, keeping the gap at a manageable size. Katie Asmuth, now running in third, received the award for the happiest runner through midway, and the one with the hat with the most flair.

By mile 61, Pascall had worked herself into 10th overall, but the full group of top-10 women were running within about 45 minutes of each other. And at 10.5 hours in, there were 19 women in the overall top 40, a testament to the depth and talent in the field.

At mile 71, along the infamous Cal Street, the race was on. Pascall came through at 11:51, moving up to ninth overall with a fast transition. At just 14:15 back, Debats barely stopped at the aid station. Two minutes later, Asmuth ran through, only grabbing ice. Croft followed less than four minutes in arrears, and Peterson came through flying two minutes later. Tanguy left a mere four minutes after that. Count them! That’s six women within 27 minutes of each other almost three quarters of the way through a 100 miler. What, what?

In the next 14 miles, Croft made her move, coming through Auburn Lake Trails, mile 85, in second, just 18 minutes down on Pascall, but only a mere two minutes up on determined Dabats. A charging Peterson moved by Asmuth. With the top-six women now within 45 minutes of each other at mile 85, there was still plenty of racing to be done in the final miles.

But no one could stop Pascall. Consistent from Olympic Valley to Auburn, she finished in 17:10:41, the second-fastest time in women’s history. She was also seventh overall, continually moving up through the field as the day wore on.

Croft finished a strong second in the women’s field and ninth overall with a time of 17:33:48. Debats would hold on to finish third with a time of 17:41:13, putting three women into the top-10 overall.

This trio was followed by Peterson and Asmuth rounding out the top-five women. For the balance of the women’s top 10, sixth place was ultimately Tanguy, her first Western States finish. This year, seventh place belongs to Emily Hawgood, the Zimbabwean who lives in the U.S., and who has a charmer of a story. Hawgood tried three Golden Ticket races to gain Western States entry this year, achieving it on the third try. In eighth was Camelia Mayfield, who follows up on her fifth-place finish in 2019 with another smartly run race in this gnarly year. Keely Henninger gains the F9 bib in her debut 100 miler, and 10th place belongs to none other than Kaci Lickteig (pre-race interview), whose finish marks her seventh at this event.

Together these 10 women finished within the top-21 overall. Let’s just pause a moment to let that significance soak in.

And to bring this full circle, Gallagher and Herron crossed the line outside of the top 10 having their own challenging days. And Bracy threw in the towel at mile 62.

(06/27/2021) ⚡AMPby I Run Far

These races are epic and why ultrarunning is soaring in popularity

The events can be gruelling and even dangerous, yet more and more people are signing up

John Stocker hadn’t slept in three-and-a-half days when he finally crossed the finish line after running more than 337 miles in an ultramarathon event in Suffolk, stopping only at brief intervals for food and rest.

Of the 123 people who started the race in Knettishall Heath on 5 June, he was the last person still running 81 hours later on Tuesday evening, and had to summon all of his physical and mental strength to get around the last lap.

“Your tiredness just takes over. And then I clipped my toe and went down on the concrete. I laid there thinking I wasn’t going to be getting back up,” the 41-year-old personal trainer said, as he recovered at home in Bicester. “But the whole reason I do these ultras is to show my kids that they should try to achieve as much as they can, and not be told by anyone that they can’t do something. That’s what kept me going.”

Ultrarunning has soared in popularity, with a report in May showing a 345% increase in participation globally over the past 10 years and thousands of events taking place annually. Meanwhile, participation in 5Ks has declined since 2015, and participation in marathons has levelled off.

The term broadly refers to any race over the length of a marathon, and can come in many shapes and forms – including the six-day, 251km Marathon des Sables across the Sahara, and the Spine Race across the Pennine hills covering 431km.

“It has been an explosion. When I came to ultrarunning about 14 years ago, I did a Google search and found about 60 races. Now we estimate there’s probably about 10,000,” said Steve Diedrich, the founder of the website Run Ultra. “The pandemic put people into two categories: the people who sat on the couch and the people who got off the couch. And those who got off the couch have pushed themselves further and become ultrarunners.”

Adharanand Finn, the author of The Rise of the Ultra Runners, said: “Generally as running has got more popular and more people have done marathons there’s a natural inflation. To tell people you’ve run a marathon is maybe not as impressive as it once was.

“These races are so epic and so huge, people are so impressed and it’s easy to get sucked in by that.”

The UK has a long history of ultrarunning in the form of fell races, but races specifically labelled as ultras are on the increase. The “back yard challenge” races, which originated in the US, are particularly gruelling; at the Suffolk event participants had to run a 4.167-mile (7km) route every hour until they could no longer carry on. If runners complete their lap early they can take a short break to sleep, eat and use the toilet before heading back to the start line.

“It’s like Groundhog Day. Because you get back to the tent and you’ve got a few minutes and then all of a sudden it’s your next loop, it starts all over again,” said Stocker. “I still have nightmares now of them blowing the whistle over and over again.”

Along with his fellow runner Matthew Blackburn, he beat the world record for the event previously held by Karel Sabbe, a Belgian dentist who ran 312.5 miles (502km) in 75 hours in October. Now the pair will head to Tennessee to take part in the back yard ultra world championships and compete against the best in the field.

The races are not without risk. The ultrarunning community is still reeling from the deaths of 21 runners in an ultramarathon event in China last month after high winds and freezing rain hit the course. The country has suspended all long-distance races and an investigation into the tragedy is being carried out.

“Through the history of ultraracing there have been issues with floods, cold exposure, heat exposure, a range of everything depending on the location,” but deaths are very rare, said Diedrich. In its 35-year history, two people have died taking part in the Marathon Des Sables.

“We have to have some sort of a safety net, because you’re asking people to push to the absolute limit of their exhaustion,” said Lindley Chambers, the owner of Challenge Running, which organised last week’s Suffolk back yard ultra. He said the route was carefully mapped out to avoid risk of injury and staff were on hand to aid runners at all times.

“You need to be sensible, and manage the risks as best you can,” he said. “But then on the other side, the runners want it to feel like an adventure, they want to feel like they’re challenged. They don’t want you to hold their hand all the way round.”

(06/26/2021) ⚡AMP

The Western States 100 Is Back and It’s Going to be HOT!

Western States is famously competitive - and this year is shaping up to be one of the toughest competitions yet with hot temps, and a stacked field.

Jim Walmsley and Magda Boulet will be back at the Western States Endurance Run this week.

And so will Clare Gallagher, Patrick Reagan, Max King and Brittany Peterson. And, so too is race pioneer Gordy Ainsleigh and 312 other inspired runners who have been training for more than a year and a half to get to the starting line. In fact, we’re all heading back to the Sierra Nevada range this weekend — even if vicariously — to what feels like a bit of normalcy returning.

After a year mostly away from the trail racing running scene, things are starting to feel like old times. With stacked men’s and women’s fields, scorching heat in the forecast and last year’s Covid-19 hiatus hopefully mostly behind us, it’s definitely the event the ultrarunning community has been looking forward to. The race begins at 5 a.m. PST on June 26 and it looks like it’s going to be an epic one. (Follow via live tracking or the live race-day broadcast.)

“Yeah, it will be good to be there and see people and actually be in the race,” says Walmsley, who won the race in 2018 and 2019 in course-record times. “It’s been an odd year.”

Odd for sure, but with deep men’s and women’s fields, hot weather, dusty trail conditions and the late June gathering of a few hundred runners on this hallowed ground feels somewhat normal. The mountains and canyons in and around Olympic Valley northwest of Lake Tahoe have been a sacred place for the native Washoe people for thousands of years before Gordon Ainsleigh’s first romp over the Western States Trail in 1974.

It’s been an especially odd year for Walmsley, who, for the second straight year, had planned to use the first half of his year training for the 90K Comrades Marathon in South Africa. But that was canceled last year (with just about every other big race, including the Western States 100) and this year, too.

So instead, after setting a new U.S. 100K road record in January, he took a sponsor’s entry into the Western States 100 from HOKA One One and will be once again lining up in America’s most celebrated trail running race. With notable first-timers Tim Tollefson and Hayden Hawks in the mix along with Walmsley, Reagan, King, Matt Daniels, Alex Nichols, Kyle Pietari, Mark Hammond, Stephen Kersh, Jeff Browning and Jared Hazen all returning with previous top-10 finishes, on paper anyway, the men’s race is shaping up to be one of the most competitive in recent memory or maybe ever, even though it’s comprised entirely of domestic runners.

The women’s race might be even more competitive with former champions Boulet, Gallagher (2019) and Kaci Lickteig (2016) leading the way, plus elite American runners Camille Herron, Addie Bracy, Camelia Mayfield and Keely Henninger and international stalwarts Ruth Croft (New Zealand), Audrey Tanguy (France), Beth Pascall (UK), Emily Hawgood (Zimbabwe), Kathryn Drew (Canada) and Ragna Debats (Spain) joining the fray.

Who are the favorites? It’s hard to tell. Most of those runners, including Walmsley and Boulet, have admitted to having dealt with some minor injuries, inconsistent training, a lack of motivation and other setbacks over the crazy year that was. Based on what runners have been reporting, it seems like most are just eager to get back and immerse in a competitive 100-miler and see what they can do.

However, one of the keys will certainly be who can survive the heat the best. The forecast is calling for high temperatures in the upper 80s to the high 90s on Saturday after and the canyons between Robinson Flat and Michigan Bluff could even reach over 100 degrees.

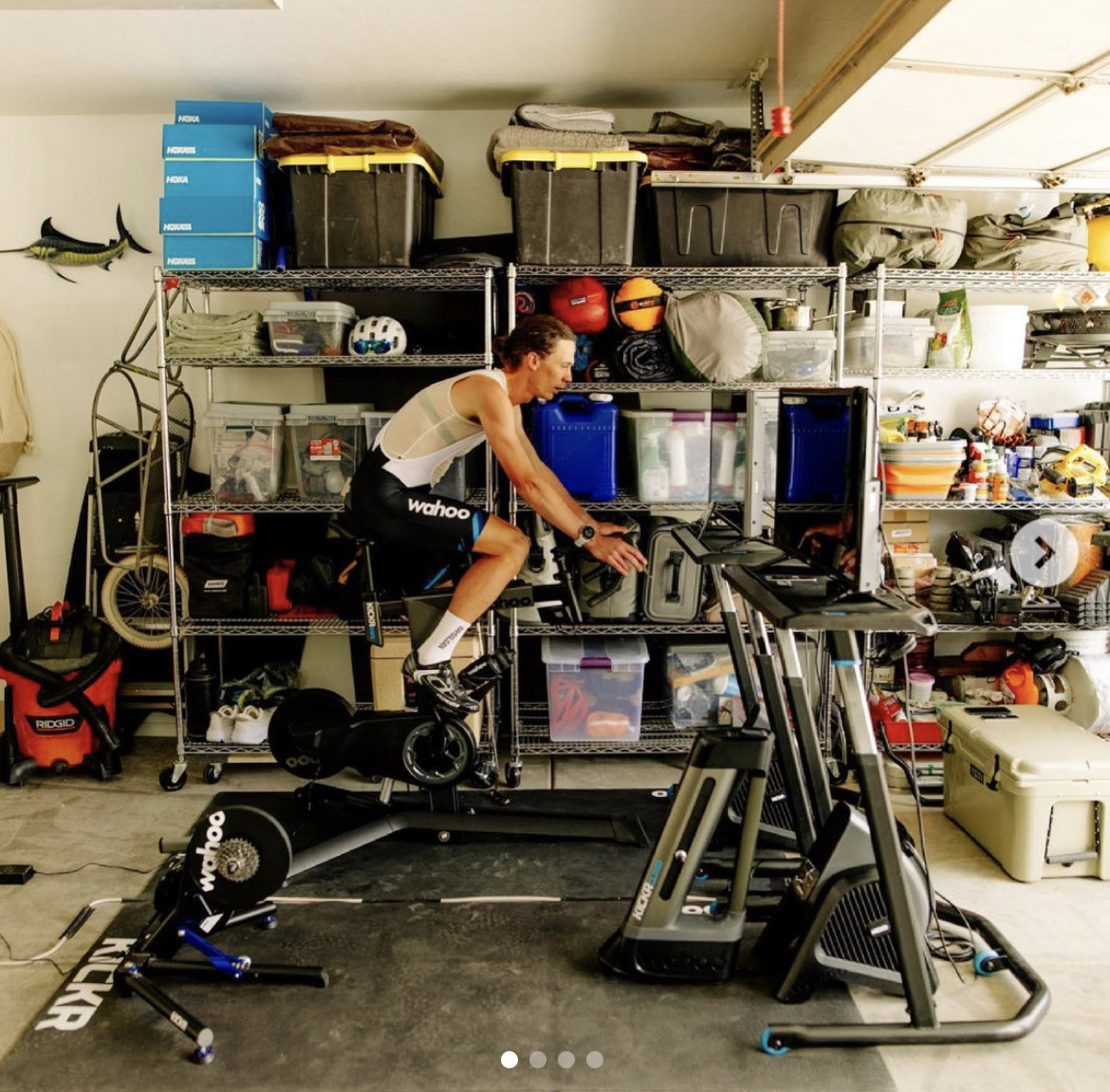

Walmsley has said he’s dealt with some IT band issues and has focused mostly on running with a lot of vert, focusing on getting optimal recovery, strength sessions and body work, as well as spending as much time running in extreme heat as possible. That includes running and hiking countless laps to the summit of 9,298-foot Mt. Elden in Flagstaff, averaging 20 to 25 hours per week on the trails and also spending a lot of time on a bike trainer.

But he’s also spent a lot of time in the infrared sauna in his home and spent time with family in the Phoenix area, where he ran in the afternoons amid 115- to 120-degree heat.

“The heat training is kind of lucky for me, because growing up in the heat in Arizona, I didn’t know any different,” Walmsley says. “I just thought everyone was roasting in the heat. It’s what I grew up with and I try to lean into those memories and embrace the heat.”

Boulet, who lives in Berkeley, Calif., has also gone out of her way to train in the heat. While she says her build-up has been inconsistent compared to previous years, she’s been doing a lot of climbing and descending in the heat, and also working on box jumps to strengthen her legs for the long descent into Auburn. She says a recent 40-mile run up 3,849-foot Mt. Diablo east of Berkeley, is a good indicator that she’s ready to roll.

“I’ve definitely been spending more time in the heat lately, which is something I personally don’t enjoy running in,” says Boulet, who won the race in 2015, DNF’ed in 2016 and placed second in 2017. “But I know the importance of preparing in the heat and falling in love with running in the heat by race day. You can be as physically as ready as possible in terms of your fitness, but if you don’t have the heat training and you’re trying to tackle some of the parts of the canyons that are in the middle of the race, It’s really tough.”

Given the extreme heat, it’s not likely that anyone will challenge Walmsley’s 14:09 course record set two years ago, when it was in the low-80s and cloudy on race day. But there’s also no snow on the course this year, so the early sections that have previously forced runners to hike and walk early on will likely be faster, and that will likely result in fatigue that will slow them down in later stages of the race.

“You’ve got to take what the course gives you,” Walmsley says. “I’ve learned that you don’t fight the course where you shouldn’t. I have some splits in mind that would get me there under 15 hours and maybe close to 14:30, but it’s going to be all about feeling out what the course is giving me, following those guidelines and not forcing it. Because anyone who forces it in that heat will be doomed.”

(06/25/2021) ⚡AMPby Outside Online (Brian Metzler)

Western States 100

The Western States ® 100-Mile Endurance Run is the world’s oldest and most prestigious 100-mile trail race. Starting in Squaw Valley, California near the site of the 1960 Winter Olympics and ending 100.2 miles later in Auburn, California, Western States, in the decades since its inception in 1974, has come to represent one of the ultimate endurance tests in the...

more...Jim Walmsley opens up about injury ahead of Western States 100

The defending WSER champion has been dealing with knee issues over the past few months, but he says he's ready to race this weekend

If you follow American ultrarunner Jim Walmsley on Strava and wondered why he’s been so quiet lately, he posted on Instagram on Tuesday to talk about an injury that has been nagging him for the past few months. Walmsley wrote that he has been dealing with knee and IT band issues, but he added that he has been pain-free for the past couple of weeks. His recovery couldn’t have come at a better time, as he is set to race the Western States 100 (WSER) in California on Saturday. Walmsley is the two-time defending WSER champion and course record holder, and he will be looking to make it three wins in a row this weekend.

As Walmsley wrote on Instagram, his knee and IT band issues began about three months ago. “It was at a point I saw as a crucial time to take it seriously and take some time to address it,” he said. He made big changes to his training schedule, taking five days off of running each week for the better part of a month. Walmsley said the injury came as a surprise, noting that his training load had been steady and his workouts had been going well for the previous month.

After his “reset with running,” Walmsley said he had eight weeks to go until WSER. While he might have felt better, he didn’t push himself too much, and he spent the next while taking care in his workouts and visiting his physiotherapist regularly. He added that he spent a lot of time riding his bike to make up for his lack of run training in this period.

Walmsley races at Hoka One One’s Project Carbon X 2, where he ran 6:14:26, just 12 seconds off the 100K world record. Photo: Hoka One One

“This block has been so much more work than usual,” he wrote. “I went through ups and downs with emotions, not knowing if I’d be able to line up healthy.” With just a few days to go until WSER, Walmsley’s careful training and build to race day worked out, and he said he feels better and healthier than he has at any point in the past three months.

“I feel like I’m gaining momentum at the right time,” he wrote, “and I couldn’t be more excited to be back at Western States ready to rock.”

(06/23/2021) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

Western States 100

The Western States ® 100-Mile Endurance Run is the world’s oldest and most prestigious 100-mile trail race. Starting in Squaw Valley, California near the site of the 1960 Winter Olympics and ending 100.2 miles later in Auburn, California, Western States, in the decades since its inception in 1974, has come to represent one of the ultimate endurance tests in the...

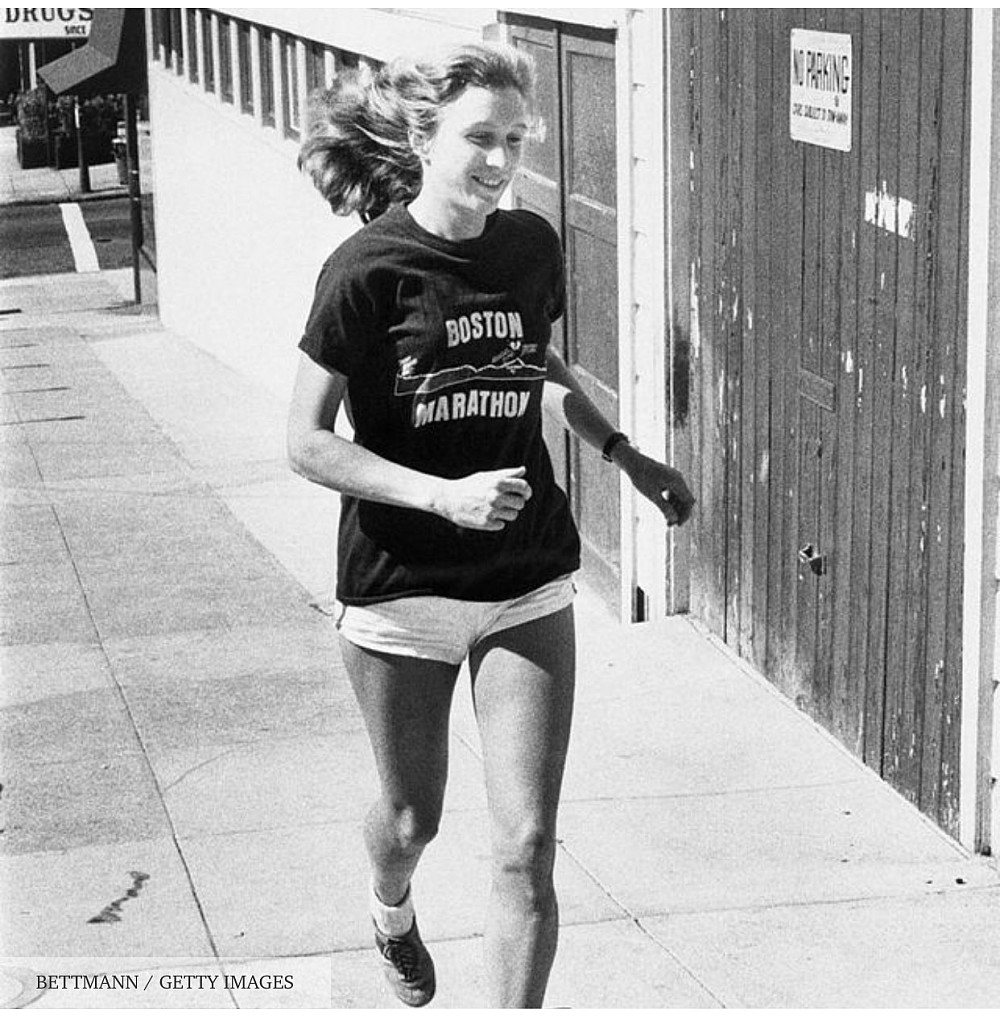

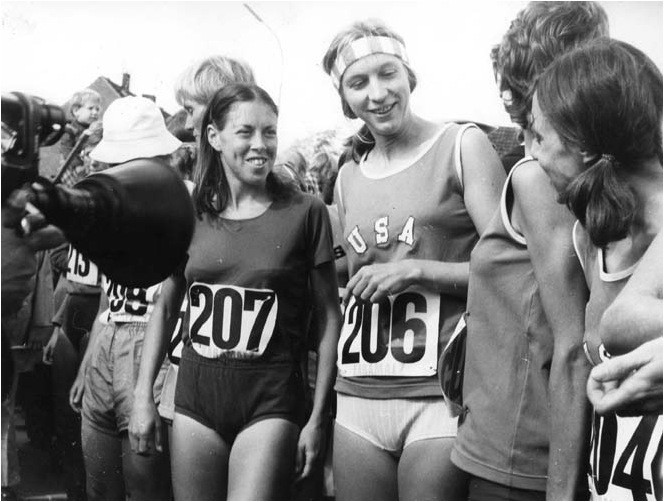

more...Joan Ullyot a pioneer for women’s running has died

Women’s Running Pioneer Joan Ullyot Dies at 80

She started running at age 30 and was instrumental in lobbying for the women’s marathon to be included in the Olympic Games.

Dr. Joan Ullyot, whose running achievements and medical expertise made her a major pioneer of women’s running, died on June 18, at her home in Snowmass Village, near Aspen, Colorado. She was 80. The cause was a heart attack.

Ullyot’s book, Women’s Running, published in 1976, was the world’s first on the subject, and she was a leader as a writer, speaker, medical scientist, activist, and role model for all women who begin to run relatively late in life, in her case at 30.

Growing up in Pasadena, California, Ullyot went to Wellesley College, but at that time she was so uninterested in running that she never troubled to watch the Boston Marathon go by. A talented linguist, she aspired to the Foreign Service, until she learned that women diplomats were not permitted to marry. Switching to medicine, she attended the Free University of Berlin, and entered Harvard Medical School, becoming one of its early women graduates.

She held a fellowship in cellular pathology at the University of California, married, and had two sons, before growing discontent with her 30-year-old body.

“I was the ultimate creampuff. If I could become an athlete, anyone could do it,” she is quoted as saying in Running Encyclopedia.

She gave credit for her venturing into running to Dr. Kenneth Cooper’s seminal book Aerobics, and to assistance from the family black lab, who towed her up the local hill on her experimental first runs, as she told Gary Cohen in an extensive 2017 interview.

Her first race was San Francisco’s iconic Bay to Breakers, and within a few months she had run her first marathon, placing 13th at Boston in 1974, only the third time the race was officially open to women. Quickly, Ullyot began applying her varied intellectual skills and high energy to the totally new field of women’s running.

Within two years, she was winning races like Lilac Bloomsday in Spokane and Hospital Hill Run in Kansas City, representing the U.S. as both a marathoner and interpreter at the International Women’s Marathons in Waldniel, Germany, writing articles and columns for Runner’s World and Women’s Sport and Fitness, and traveling the world as a groundbreaking speaker.

“I talked all around the country on the same ticket as George Sheehan and Joe Henderson. It was great fun,” she said in the Cohen interview.

Absorbed in this new area of knowledge, she switched her medical specialty from pathology to exercise physiology. In 1976, only three years after she took her first running steps, she had researched and published Women’s Running with the World Publications division of Runner’s World.

She sold the idea to editor Joe Henderson and publisher Bob Anderson as a way of dealing with the numerous queries she was receiving, as a Runner’s World columnist, from new women runners. The book was a bestseller, and she followed with Running Free (1980; her own story plus profiles of runners such as Sister Marion Irvine) and The New Women’s Running (1984).

Ullyot’s own racing continued to progress, as she followed Arthur Lydiard’s training principles with guidance from U.S. marathoner Ron Daws. She ran Boston 10 times, winning the masters race in 1984, at age 43, with a 2:54:17. She won 10 marathons outright, and finally broke 2:50 at age 48, with her 2:47:39 personal record on the time-friendly St. George Marathon course.

She chose her races like her wines, with catholic enthusiasm, and was a loyal supporter of San Francisco’s local DSE (Dolpin South End Runners) events as well as eagerly taking international opportunities with the Avon Circuit and extending her active career through ultraracing.

Her medical standing made her an important advocate for women’s distance running in the years of lobbying and protest that led ultimately to the inclusion of all women’s events in the Olympic Games.

“Her research was presented…to the International Olympic Committee by the Los Angeles Olympic Committee before the vote to include the women’s marathon in the 1984 Games,” said former world record holder Jacqueline Hansen in an online tribute this week. That credit is also given in the citation for Ullyot’s induction into the Road Runners Club of America Hall of Fame in 2019.

Ullyot and her second husband, scientist Charles Becker, moved in the early 1990s to Snowmass. She coached the Aspen Runners Club for about 10 years from 1993, and kept in shape by biking until a nearly fatal crash. In her later years, she focused on walking.

Many tributes this week have recalled her high intelligence and zest for life.

“In the weeks leading to her unexpected death, Joan was characteristically high energy and had a blast,” wrote her son Ted Ullyot.

“In the 1970s, as we all worked to break down the myths that restricted women from running, Joan was our medical beacon, a feisty example of transformation from zero to 2:47 marathon, and an unstoppable personality, bigger than life, opinionated at the top of her mighty lungs, and with an unstinting appetite for fun and capacity for wine,” said Kathrine Switzer.

Ullyot also sustained her lifetime devotion to travel, reading, and friendships. These included many who were her competitors and collaborators in the 1970s and ’80s, years when their pioneering generation created, advocated, fought for, and left strong the visionary new sport of women’s road running.

(06/23/2021) ⚡AMPby Runner’s World (Roger Robinson)

China punishing 27 officials after deadly ultramarathon

Runners everywhere were shocked last month when they learned on May 23 that 21 athletes had died of hypothermia when extreme weather hit the Huanghe Shilin Mountain Marathon in the northwestern province of Gansu, China. According to a report by CNBC, 27 government officials deemed responsible for the incident, which was one of the world’s deadliest sporting tragedies in recent history, have been punished.

The Gansu government opened a formal investigation soon after the tragedy occurred, and on Friday they announced that several government officials had been dismissed from their posts, including the head of Jingtai county, where the race was held. The mayor and the Communist Party chief of the city of Baiyin, the jurisdiction in which Jingtai belongs, were also dismissed, while several others received major “demerit ratings” and disciplinary warnings.

According to the investigators, the tragedy was a public safety incident, caused by extreme weather, high winds and cold temperatures, along with unprofessional organization and operation. Just over a week ago, China’s sport administration also announced that it was suspending all high-risk sports events that lack a supervisory body, established rules and clear safety standards, including mountain and desert trail sports, wingsuit flying and ultra-long distance running.

(06/20/2021) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

Western States 100 preview: pre-race favourites

Women’s field - There are three former WSER champions entered in this year’s race: Gallagher, who won in 2019, 2016 winner (and 2019 third-place finisher) Kaci Lickteig and 2015 champ Magdalena Boulet. All three women are American, and they’ll be joined on the WSER start line by several of their high-profile compatriots. Brittany Peterson, the second-place finisher from 2019, will be in the race for just the second time in her career, along with Nicole Bitter, the seventh-place woman in 2019, which was also her WSER debut.

Pascall and Drew headline the international entries in the women’s field. Pascall, who hails from Great Britain, finished fourth in 2019, and she is a serious threat to take the win this year. Earlier in 2021, she won the Canyons 100K in California, and in 2020, she broke the Bob Graham Round FKT in her home country. She has also recorded two top-five finishes at the past two editions of the famed Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc. Pascall is in incredible form, and she’s a threat to run away with this year’s race, which would make her the first non-American woman to win the WSER title since Ellie Greenwood (who is British but lives in Canada) in 2012.

This will be Drew’s second WSER appearance, and she, too, has what it takes to improve on her result from 2019. She has several big wins to her name, including top finishes at the Chuckanut 50K and Canyons 100K in 2019. She has also represented Canada at the IAU Trail World Championships. B.C.’s Sarah Seads will also race in California, making her first WSER appearance.

When it comes to debut WSER runs, there are several big names to watch. New Zealand’s Ruth Croft is having a tremendous season, with a pair of big wins. Her first came at the Tarawera Ultra in Rotorua, New Zealand, where she won the overall title in the 102K race. A few months later, she was in action in Australia, where she won a 50K race in Katoomba, a town west of Sydney, at Ultra-Trail Australia.

France’s Audrey Tanguy is also running WSER for the first time. Tanguy has had a great year so far, first winning the Hoka One One Project Carbon X 2 100K event in Arizona in January and then following it up with a third-place finish at the Canyons 100K in April. She is also a two-time UTMB TDS winner (2018 and 2019).

Finally, there’s American ultrarunning star Camille Herron. The owner of multiple American and world records, Herron is another threat for the win at WSER. She has won the Comrades Marathon, multiple world championships and many other races around the world, and it shouldn’t be a surprise if she adds a top WSER finish to her resume.

Men’s field - The only WSER champion in the 2021 field is Walmsley, who has won the past two editions of the race. In 2018, he won in 14:30:04, and a year later, he set the course record with an incredible 14:09:28 run. This year, he has raced one ultramarathon, Hoka’s Project Carbon X 2, which he won in 6:09:26, coming extremely close to breaking the 100K world record of 6:09:14. That was several months ago, but if his fitness is anywhere close to where it was at that race, he should be able to lay down another historic WSER run.

Walmsley’s fellow American Jared Hazen, the 2019 runner-up, is also set to race this year. In 2019, Hazen ran a remarkable time of 14:26:46, which would have easily won him the WSER title if Walmsley hadn’t been in the race. He’ll be looking to take that final step onto the top of the podium this year.

A pair of Americans making their WSER debuts are Tollefson and Hayden Hawks. Tollefson has several big wins to his name in the past year alone, including titles at the 2020 Javelina Jundred 100 Miler and USATF 50-Mile Trail Championships. He has also recorded victories at the 120K Lavaredo Ultra-Trail race in Italy in 2019 and the 100K Ultra-Trail Australia in 2017, along with a pair of third-place finishes at UTMB in 2016 and 2017.

Hawks has won many races throughout his career, including the JFK 50-Miler in 2020. He set the course record of 5:18:40 at that race, beating Walmsley’s mark of 5:21:28 from 2016. The WSER course is twice as long as the JFK 50, but Hawks has proven he can match or better Walmsley’s efforts, so it will be interesting to see how he fares in California.

(06/20/2021) ⚡AMP

by Running Magazine

Missouri man returns for another ‘Grandma’s Double,’ running the course twice in one day

The first 25-26 miles are “the easy ones,” said Eric Strand, 60. “Then you have the benefit of aid stations, the crowd and fellow runners to commiserate with on the way back. It’s a fun way to get a training run in.”

Before runners hit the starting line, before volunteers set up aid stations and before the sun rises, Eric Strand is running Grandma’s Marathon.

Backwards. And then back again.

The “Grandma’s Double” is a long-running tradition for Strand.

About 3 a.m. on race day, his wife drops him off in Canal Park. He runs 26.2 miles to Two Harbors — and joins the other marathoners for Round 2.

The first 25-26 miles are “the easy ones,” said Strand, 60. “Then you have the benefit of aid stations, the crowd and fellow runners to commiserate with on the way back. It’s a fun way to get a training run in.”

It started as a way to prepare for the 100-mile Leadville Trail ultramarathon. Grandma’s landed on a weekend that Strand needed to get in a 50-mile run. Instead of spreading it out, he decided to pack it into one day.

“It was very interesting running the course backwards, especially when the bars had people filing out. You had an interesting crowd," Strand said in a 2012 News Tribune story.

Strand gets to see things other marathoners don’t: the race course waking up and volunteers getting ready, and some of the aid station captains are there every year.

He has heard his fair share from passersby about going the wrong way, and it happens even more now.

“They've all learned their lines,” he said with a laugh.

The Missouri man, formerly of St. Paul, grew up hearing about Grandma’s, but on New Year’s Eve before his 40th birthday, he registered for it.

He trained for six months and made every mistake.

“There’s euphoria. You hit new distance markers … you get this in your mind that you are invincible. The next day, you wake up, and you have plantar fasciitis or shin splints or your knee hurts, and you very quickly realize you aren't,” Strand said.

But you slow down, heal up, maybe bike for a while and you get back to running, he added.

Strand recalled the end of his first Grandma’s Marathon: “As I was enjoying the runner’s high, my kids reminded me that there were three 70-year-olds that beat me that day. It brought me down to earth; they’re really good at doing that.”

Strand said tying training into a race is one way to make it fun. He averages about 2,500 miles a year; that’s typically 7 miles a day, but sometimes, it’s 100 miles at a time.

Strand ran his first five Grandma’s Doubles solo, save for one year with Ben McCaux. Since then, he has been joined by his son, Zach.

They’ve tackled the Double three times; they ran their first father-son Leadville 100 in 2017.

In a 2017 video of the latter, the pair are seen trekking across Colorado terrain.

“Zach’s doing great,” Eric Strand says into the camera. “He’s fun to run with. As long as he keeps his fueling and hydration in good shape, he’s down for a buckle.”

They have tallied 25 marathons and ultramarathons together.

“He’s better than me now, which he’s quick to point out,” he said.

During training, Strand mostly listens to audiobooks, but, if he needs motivation, there’s Britney Spears and Miley Cyrus — music his kids listened to when they were teens.

As for his powerhouse song, that’s Eminem’s “Lose Yourself.”

He doesn’t listen to anything during races; he likes to interact with others.

His race-day eats were pretty standard: Gatorade and gels; but for ultramarathons, his wife brings him a cheeseburger at mile 50.

Saturday will be his 22nd Grandma’s Marathon — his 10th Grandma’s Double — and there’s no end in sight.

There’s a cadence to the year — the Boston Marathon in April, Leadville in August, Chicago in October, a mix of others — but June will always be Duluth.

“There will be a day when I won’t be able to do this,” Strand said, “but it’s not today, and hopefully won’t be for a long time. I hope to enjoy it as long as I can.”

(06/16/2021) ⚡AMPby Melinda Lavine

Grandmas Marathon

Grandma's Marathon began in 1977 when a group of local runners planned a scenic road race from Two Harbors to Duluth, Minnesota. There were just 150 participants that year, but organizers knew they had discovered something special. The marathon received its name from the Duluth-based group of famous Grandma's restaurants, its first major sponsor. The level of sponsorship with the...

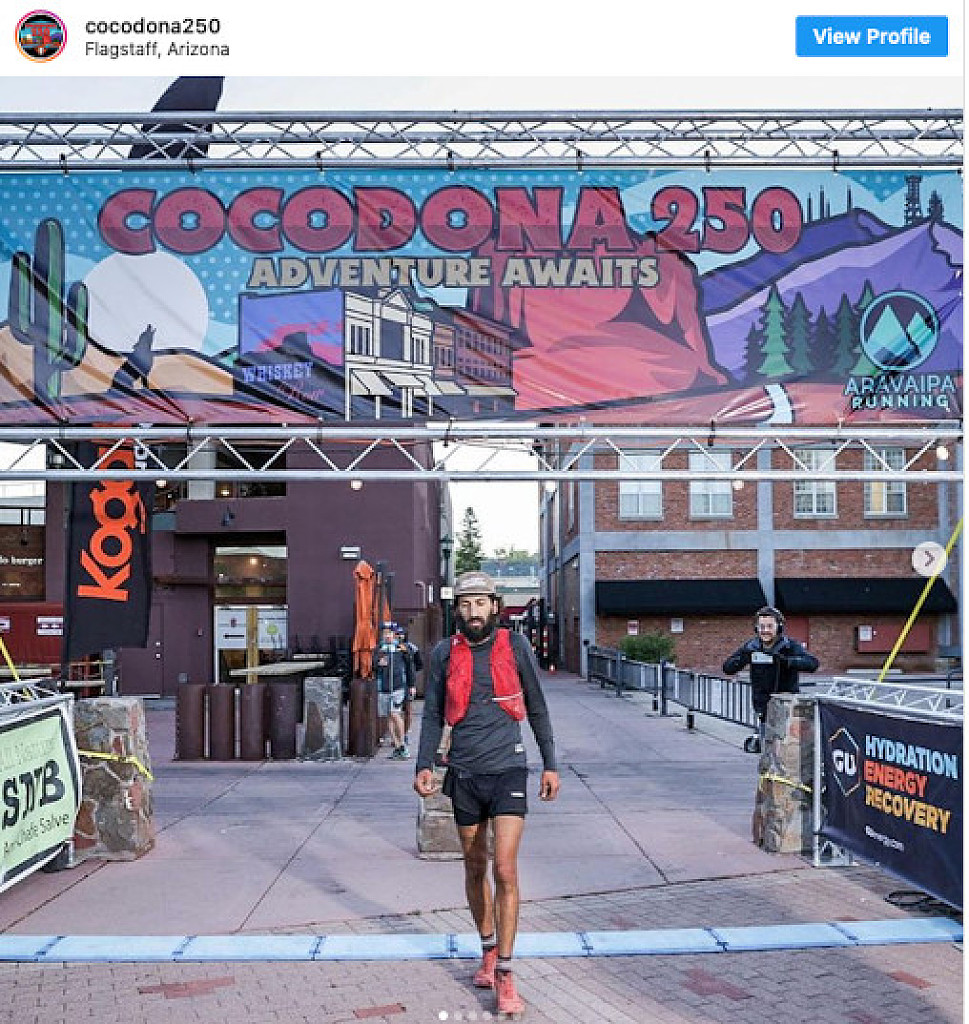

more...Gene Dykes breaks M70 50K world record clocking 3:56:43, breaking the previous record by nearly 19 minutes

On a sunny Sunday in East Islip, NY, Gene Dykes broke the M70 50K world record at the USATF national 50K road championships, crossing the finish line in 3:56:43. He beat the previous record of 4:15:55, set by Germany’s Wilhelm Hofmann in 1997, by nearly 19 minutes.

This is the third world record Dykes can add to his resume, along with his M70 100-mile and 24-hour records. While his time has yet to be ratified, this is an incredible accomplishment for the already-decorated ultrarunner. To make his run even more impressive, he completed another 50K trail race only two weeks prior to his record-breaking run, and it’s been barely one month since he ran 152 miles (245 kilometres) at the Cocodona 250 in Arizona.

According to Dykes, the weather for Sunday’s race in Caumsett State Park was sunny, moderately windy, and not too hot, with temperatures hovering in the low 20s (Celsius) for most of the event. In a brief conversation with him after the race, he told Canadian Running (in a half-joking, half-serious manner) that he credits Canada’s late Ed Whitlock, one of the most decorated masters runners who ever lived, with his new 50K record.

“Thank you, Ed Whitlock, for never running a 50K,” he says.

Dykes is still aiming to take down Whitlock’s M70 marathon world record of 2:54:48, which he will attempt to do at this year’s London Marathon on October 3.

(06/14/2021) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

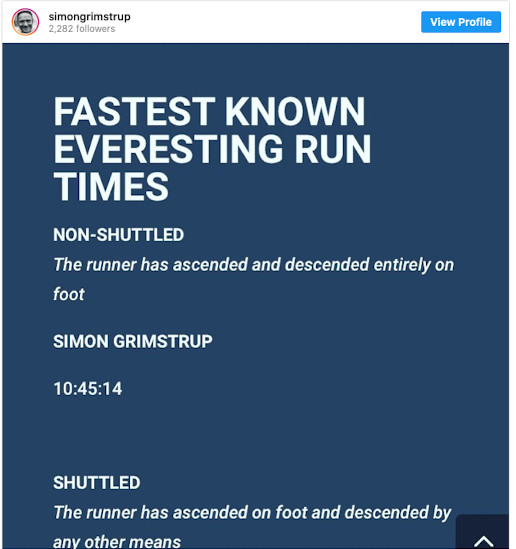

Danish runner shatters Everesting world record with sub-11-hour result

Everesting originally started as a cycling challenge that saw athletes ride up one hill over and over again until they reached 8,848m of elevation gain. As the challenge grew more popular, it found its way into the world of running, and since then, 447 runners have completed it

For a run to count as an official Everesting attempt, runners must follow a few simple rules. Firstly, the run has to be on one hill, meaning an individual can’t run around a hilly region on multiple routes until he or she hits 8,848m of elevation gain. It doesn’t matter how steep or how long the hill is, and the official rules state that “Essentially anything that has a vertical gain can be used” for the challenge.

There’s also the matter of sleep, which is not allowed in Everesting attempts. While sleep is always an option for runners in long ultramarathons, it isn’t permitted for Everesting runs. If a runner takes a nap, the attempt is over. When it comes to ascending and descending the chosen hill, a runner can choose whether to run down after each lap or get a ride down (whether that’s in a car, a gondola on a bike or any other form of transportation). Because of this option, there are two separate Everesting run records: shuttled and non-shuttled.

Grimstrup’s run was non-shuttled, and he ran or walked down the hill every lap. This not only made the challenge much more difficult, as Grimstrup didn’t get the chance to rest after each ascent, but as he said in an interview with the Vietnam Trail Series (VTS), it also left him wondering if he would make it to the finish line.

“I was not sure I would get the world record until the last two laps,” he said. “I was worried that I would fall on the downhill.” Running down a steep hill (the one Grimstrup chose was 130m long and featured 44m of elevation gain) is difficult enough on tired legs, but the task was made tougher for Grimstrup due to rain. He told the VTS team that, due to the rain, he had originally planned to only run a half-Everesting attempt as a test run on the hill.

After he ran 100 laps, though, Grimstrup said his friends convinced him to keep going for the full run. He gave in, but he said the trail he followed only got worse and more torn up with each lap. Despite the sketchy terrain, he made it to the finish, beating the previous Everesting world record by 16 minutes.

“It was the hardest, stupidest, most epic thing I have ever done,” Grimstrup said.

In addition to running the Everesting attempt for the physical challenge, Grimstrup linked it to a fundraiser for Doctors Without Borders

(06/14/2021) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

British runner breaks Backyard Ultra world record

John Stocker ran 337 miles in 81 hours at the Suffolk Backyard Ultra event this weekend

A British ultrarunner has broken the Backyard Ultra world record.

John Stocker, from Oxfordshire, ran more than 337 miles in 81 hours at the Suffolk Backyard Ultra beginning on Saturday.

Runners taking part have to complete a 4.167 mile lap of Suffolk’s Knettishall Heath every hour until they can’t carry on any longer. Participants must arrive back to the start in time for the next loop or they are knocked out.

According to race organisers, Stocker and fellow runner Matt Blackburn both beat the previous record of 312.5 miles in 75 hours, set by Belgian Karel Sabbe at Big’s Backyard last October. Sabbe told Runner’s World last year that his secret to resting was to 'give into sleep deprivation', turning his headlamp low and walking with his eyes closed so that he was ready for sleep by the time he returned to base.

Stocker and Blackburn both completed 80 laps, before Blackburn pulled out during the 81st lap. As no winner would be declared if he did not complete the lap, Stocker continued to run, completing the lap in 52 minutes, his slowest time.

That final lap was particularly difficult, Stocker told Runner's World. As he came out of the 'Spooky Woods' area of the course, he tripped and landed hard on his ribs. He thought he had "just lost it all", he said, before his resolve hardened. "I knew I just had to finish no matter what."

He said: "You could say the whole race flashed before my eyes, but with every small step I started walking along the road, then limping and onto running towards the finish and the win."

Race director Lindley Chambers told the BBC: 'What these guys have achieved is pretty incredible.'He added: 'I knew we had the calibre of people taking part and I personally thought we'd do 50 or 60 loops but these guys have gone beyond my expectation and have gone further than anyone else in the world competing in this format.'

Stocker and Blackburn reportedly completed each lap in around 45 to 50 minutes, leaving 10 to 15 minutes after each lap to rest and refuel before heading out for the next lap.

American runner Courtney Dauwalter told the BBC why this race format appealed to her in April: 'It’s a fun mental challenge,' she said, adding that backyard ultras are about 'finding out what’s possible rather than a race that you want to win. If we don’t limit ourselves, it’s pretty cool what can happen.'

(06/12/2021) ⚡AMPby Runner’s World

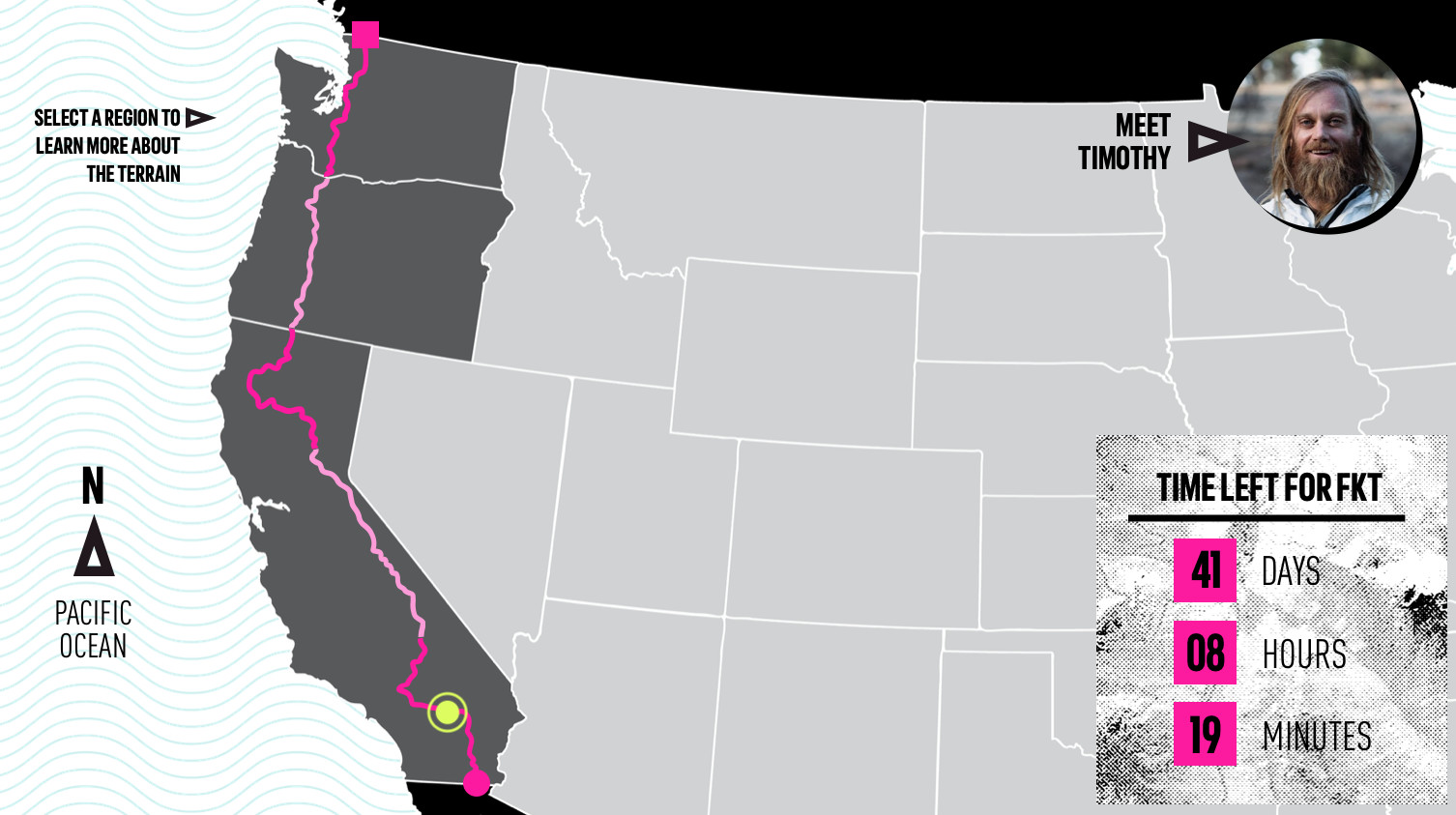

Timothy Olson Is Attempting a FKT on the PCT-The record he needs to break? 52 days

Ultrarunner and Adidas Terrex athlete Timothy Olson will attempt to set a fastest known time (FKT) on the 2,650-mile Pacific Crest Trail, starting at the California-Mexico border and finishing at Washington-Canada border. His goal? Break the current FKT of 52 days and change.

Timothy is a two-time winner and former record holder of the Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run. But he has a special connection to the Pacific Crest Trail, sections of which he’d run from his house in Ashland, Oregon, where he began his ultrarunning career a decade ago. Timothy has been training to set a FKT on the PCT for two years (last year’s attempt having been postponed by the COVID-19 pandemic). A self-professed “lover of life and explorer of nature,” Timothy’s goal on the attempt is to “live consciously” as he runs through the mountains. “I’m not trying to conquer nature,” he says. “I’m trying to move through and appreciate it.” Timothy wants his effort to be a celebration of our post-pandemic return to life. “I see this as a time for us all to reemerge from our cocoons,” he says. “I want to set a marker for what is possible.” Here's what he's up against—and how we plans to tackle it section by section.

Region 1: Southern California

Campo to Walker Pass: Miles 0-652

The southern terminus of the PCT is near the aptly named California town of Campo. A shoulder-high monument a few yards from the wall marking the Mexican border is the official starting point. From there, the trail forges north through the Sonoran Desert, through the Laguna Mountains and into the Mojave. Daytime temps here can spike to the hundreds in June, so Timothy plans on predawn starts. And because there can be up to 30 miles of trail between water sources, he will rely on midday water resupplies from his team at road crossings and trailheads.

Region 2: Central California

Walker Pass to Donner Pass: Miles 652-1,157

From Walker Pass, near the town of Kernville, the trail dips to the South Fork of the Kern River, the geographic start of the Sierra Nevada. Arguably the PCT’s most difficult section, the trail through the High Sierra spends considerable time above 10,000 feet, includes eight passes over 11,000 feet, and peaks at 13,153-foot Forester Pass, the PCT’s high point. Timothy calibrated his early-June start time to reach the High Sierra when most of the snow should be melted, so he won’t have to lug heavy gear like crampons and ice axes. The crux of his effort will be the remote section from Sequoia National Park through Yosemite National Park, where the PCT merges with the famously majestic John Muir Trail for 160 miles. Timothy likely won’t see his resupply team for several days in this section.

Region 3: Northern California

Donner Pass to Oregon Border: Miles 1,157-1,689

This Northern California section begins where Interstate 80 crosses Donner Pass and continues through the High Sierra, but then gives way to the drier volcanic peaks and plains of the southern Cascades. From there to the Oregon border, the skyline is dominated by the Mount Shasta stratovolcano. Three to four weeks into the six-week effort, Timothy will need to listen to his body to stave off overuse injuries; he may have to sleep an extra hour or two or shorten his days to let his feet, knees, or shins heal. But with his experience and abilities, says coach Koop, “he can be three days off the record in this section and make it up in a single day.”

Region 4: Oregon

California Border to Washington Border: Miles 1,689-2,144

The easiest section of the trail, the PCT through Oregon contains fewer significant elevation changes, though the route is no less stunning, winding through old-growth forests, skirting alpine lakes, and connecting snowcapped volcanoes—including Mount Washington, Mount Jefferson, and the iconic Mount Hood—that dominate the skyline. But while the run should be easier physically, Timothy will likely be getting trail weary by this point. That’s where meeting up with his family at trailheads and road crossings will be a boost. “A hug from [my son] Kai and I’ll be energized to run all day,” he says.

Region 5: Washington

Washington Border to Canadian Border: Miles 2,144-2,650

Beginning at the trail’s lowest elevation, the Bridge of the Gods (180 feet) over the Columbia River, the Washington section rises past the talismanic peaks of mounts Adams and Rainier and then northward into the rugged and remote north Cascades, probably the PCT’s second most difficult section. In addition to presenting extreme elevation gains and losses and intense, dangerous river crossings, the north Cascades can be the PCT’s wettest section, with frequent summer storms that should test Timothy’s resolve and gear. “I’ll go several consecutive 60- and 50-mile days without seeing my crew—and may arrive at the border alone if the access from Canada is still closed.”

(06/12/2021) ⚡AMPby Outside On Line

China will file criminal charges against 27 officials after deadly ultra marathon

China reported on Friday that it will file criminal charges and take disciplinary measures against 27 leaders and public officials who were found responsible for a disaster in a recent marathon, in which 21 runners died after an abrupt change in weather conditions.

After revealing the findings of an investigation, authorities in the northwestern province of Gansu mentioned, among the officials sanctioned, some leaders of the Communist Party and the administration of the county and city where the tragedy took place on May 22.

They emphasized that the incident occurred as a result of poor quality and unprofessional management.

The Gansu Government opened an investigation into the incident, as the marathon covered 100 kilometers and some parts of the route recorded temperatures close to zero degrees.

The mountain race was taking place in a forest in Baiyin County with 172 participants, but a spate of hail, freezing rain and gale force winds suddenly lashed a 20-30 kilometer section of the event, which included a high-altitude stage.

Organizers stopped the marathon when they found that many runners suffered physical discomfort and loss of body heat due to low temperatures, while some went astray. However, 21 died, including Asian champion Liang Jing and Paralympic star Huang Guanjun.

As a result of the incident, China suspended other similar competitions until it checked its safety mechanisms, as it detected flaws in their organization and logistics to respond to emergencies.

(06/11/2021) ⚡AMPby Prensa Latina

Canadian Stephanie Simpson to attempt Canadian 100-mile record on June 12 at the Montreal 24-hour Endurance Challenge

Canadian ultrarunner Stéphanie Simpson will be attempting to break the Canadian 100-mile (160 km) record this weekend at the Défi 24 heures Endurance (24-hour endurance challenge) in Montreal, Que. The current Canadian record, held by Michelle LeDuc of Russell, Ont., is 15:19:45, and Simpson’s goal is to not only beat that time, but to complete the distance in 14:45.

Simpson began running in 2008 as a way to deal with stress when her mother was sick. She started the way many of us do, running shorter distances like 5K’s and 10K’s, eventually working her way up to half-marathons and marathons. She completed her first 50-kilometer ultramarathon after the birth of her first child in 2015 and never looked back. She was relatively unknown in the world of ultra trail running until last October when she became the Canadian winner at Big’s Backyard Ultra, running for 43 hours to lead Team Canada to a third-place finish.

So what does the training for a record attempt like this look like? For Simpson, it’s been fewer really long runs and more speedwork.

“I haven’t run really long distance since the Backyard,” she says. “Since then, I haven’t done anything above 50, but I’ve still been doing big weeks of 200 kilometers. I’ve been doing more speed lately, because you need some kind of speed to run for that long at that pace.”

To run her goal time, Simpson will need to maintain a pace of 5:29 per kilometer. Because the event is a 24-hour race, her plan is to get through 100 miles in her goal time, then see what happens with the rest. The Canadian 24-hour record is 238 kilometers, and while that record isn’t her main goal, two records in one race isn’t out of the realm of possibility. Regardless, in order to achieve her goal, Simpson says mindset and confidence are the two main keys to success.

“A hundred-miler at that pace is really mental, so you have to be really really ready,” she says. “I’ve been visualizing everything that could happen, and when you run those kinds of distances, you have to be really confident in your plan — that’s the only way you’re going to get through 100 miles.”

Simpson will be running with seven other local runners around the outdoor track at McGill University. The race is set to begin at 8 am this Saturday, June 12, and if all goes according to plan, she should reach the 160-kilometer mark just before 1 a.m. on Sunday.

(06/08/2021) ⚡AMPby Brittany Hambleton

Meet Chamonix's Trail Running Dog

Here's a lesser-known fact about Chamonix, France, one of the world's renowned trail running towns: it might just have the planet's highest density of tough mountain dogs. Here, there are dogs living at high mountain huts, guarding livestock, rescuing avalanche victims and even climbing ladders bolted to cliff sides. Dogs saunter along the pedestrian center of Chamonix, often unaccompanied, and wander into cafes and restaurants as if they own the places. And, in a sense, they do.

Into this mix, and reigning over the high northeast end of this 20-kilometer-long valley is the fluffy-but-tough Enzo Molinari Spasenoski Kotka, longtime trail-running partner to one of the world's strongest ultrarunners, Sweden's Mimmi Kotka.

Kotka, 39, though she lives a low-profile life with her husband Toni Spasenoski, is well known in the valley. Sponsored by La Sportiva, she has a litany of top finishes in the world's most competitive ultras. In Chamonix alone, she has won three races: the 90K in the Mont Blanc Marathon series, the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB) 101K CCC and the 119K UTMB TDS, during which she set a course record. Modest and easy-going, you will never hear Kotka brag about her successes. Well, almost never. Once, a few days after winning TDS, Kotka was stopped on a trail and got to deliver a line many dream of uttering. "Did you run one of the UTMB races?" a passerby asked. Kotka admitted that, why yes, in fact, she had. The questioning continued. "So, how did you do?" Kotka chuckled and beamed. "I won!"

Kotka, who has a Masters of Science in Molecular Nutrition and is a partner in Moonvalley, an organic sports food company, lives in the village of Le Tour, just below the Swiss border, with her husband Spasenoski, who works remotely as a high-tech project manager. And, rounding out the family, there is Enzo.

Spend more than a day or two on the quiet, rugged trails in this part of the valley and your paths will cross with Mimmi and Enzo. They are so often together, it's more common to hear Mimmiandenzo than the former without the latter.

Enzo, now 4, it must be said, is beautiful and highly photogenic. His thick, mottled coat of blue-gray, brown, black and white fur is perfectly suited for a life herding sheep high in Italy's Gran Paradiso region from where he came.

Kotka's trail-running partner seems to know just how gorgeous he is. "He's kind of a Diva," Kotka says. "He just wants attention. He'll lie down in front of onlookers, expecting to be admired and cuddled. We spoiled him, and we got the dog we deserve."

These days, Enzo is getting plenty of time in the limelight. Kotka's Instagram feed is filled with striking photos, taken by Spasenoski, of the two out in the mountains in all seasons. Spasenoski joins the two for runs, taking photos and struggling to maintain the pace. Enzo knows the drill, often climbing up to view points, puffing his chest like the Lion King surveying his kingdom. "He thinks he's a mountain guide, but really he's an influencer," Kotka laughs.

With or without the lens eye, however, Mimmiandendzo have a tight bond on the trail. Together, they have run to glaciers halfway up Mont Blanc and high-mountain huts like the Refuge Albert Premier perched on the jagged skyline high above their Le Tour home.

"Sometimes, when I'm running with him, I feel one energy." Kotka pauses, trying to explain the sensation. "I feel very connected to him." When she stumbles, she says, Enzo immediately runs back to her to make sure she's okay.

There are the inevitable bumps, of course. Herding is part of Enzo's DNA, and there's no off switch, either. Running high above their village, Enzo once spotted a sheep away from its flock.

"He went completely nuts," says Kotka. "He was barking like mad and not listening to me. At the time, I didn't understand the instincts of a shepherd dog." At other times, Enzo's been known to herd escaped sheep back to the right side of their fenced-in pastures.

For better or worse, those herding instincts apply when the animal has two legs, too-that can make for awkward moments when Kotka is running with friends and the group spreads out. "I feel sorry for the runner in the back," explains Kotka. "Enzo literally nibbles at their butt."

Like every mountain runner, Enzo has had his accident or two. Descending from the Possettes, a dramatic ridgeline that is part of the course of the Mont Blanc Marathon, he took a tumble over a cliff band. The two heard Enzo barking, far below. Early spring, he fortunately landed on a snowfield but had taken a long slide.

"He was OK, but frazzled," says Spasenoski. "I've done the same thing!" And a few winters ago, out with Kotka while she was ski mountaineering, Enzo injured his eye in a freak accident when he hit a metal object buried in the snowpack. An infection and cataracts ensued. To protect his eyes after the incident, their Italian adoptee received dog goggles for Christmas. They did not go over well.

"He wouldn't move. He was like a statue," says Spasnoski. "He was like, 'What the hell am I wearing?'" These days, Enzo takes a timeout during the rugged Alps winter season.

Along the thousands of kilometers of mountain trails they've shared together, Enzo has been a teacher as well. "I've learned a lot from Enzo," says Kotka. "I wasn't expecting that." [TK-any specific lessons?]

What other life lessons has their social media star imparted to the family? "Some days can be pretty crummy," says Spasnoski, "But then you see this guy," he says, gesturing downward. "And everything is OK."

"Enzo makes us a family," Kotka adds. "We have someone to care about. He's been good for our relationship. Besides, she adds, "He's such a character, and makes us laugh. And he has a good heart. Right, Enzo?"

The tail thumps once on the floor. Definitely.

Name: Named after Enzo Molinari, a character from Kotka and Spasenoski's favorite film, The Big Blue, about the world's greatest free diver. Before discovering trail running, Kotka had a brief obsession with free diving. All that remains are, she notes, a lifelong addiction to the film and a bad diver tattoo on her back. Molinari had a big personality and a kind heart.

Birthplace: Enzo was born at an organic honey farm in Valsavarenche, Italy, next to northern Italy's wild Gran Paradiso National Park. One of six pups, his mom is Australian Shepherd. His father has been narrowed down to one of three likely suspects, but has not come forward.

Age: Four, or 32 in dog years. Enzo turns 5 on June 12th.

Weight: 30 kilos, about 65 pounds.

Favorite animals: A very large, fat cat used to be part of the family, and to this day Enzo loves cats. (As a rule, they do not love him back.)

Running Routine: 10 to 20 kilometers a day. "Around here, that's a lot," says Kotka, alluding to the challenging nature of the terrain around Chamonix. Enzo avoids runs of more than a few hours, and during the warm summer months prefers to run in the early morning or later in the day ."He could easily go for 10 hours," says Kotka, who is cautious about the miles logged on Enzo's pads. "He loves riding lifts," she adds.

Longest Trail Run: The pair did a two-day reconnaissance of parts of UTMB's technical TDS course. "We went slowly," says Kotka, "and made plenty of stops."

Favorite food: Homemade cheese pizza. "Eating some of a pizza I made was the only time he didn't greet Mimmi," says Spasenoski. "He's Italian. What do you expect?"

When he's not trail running: Napping on cool surfaces and sniffing human butts.

House rules: Enzo's not allowed in the bed. "It's too hot for him, anyway," says Kotka. Instead, he sleeps near the drafty balcony door. After breakfast, he'll often sleep outside in the cool mountain air that blows off the nearby Le Tour glacier.

(06/06/2021) ⚡AMPby Trail Runner Magazine

China suspends all high-risk sports events after deadly mountain ultra-marathon

China has indefinitely suspended all ultra-marathons and trail-running events in the wake of a mountain race that saw 21 runners die in extreme weather last month.

The staggering death toll of the 100-kilometer (62-mile) ultra-marathon in Gansu province triggered a public outcry over lax industry standards and weak government regulation.

On Wednesday, China's General Administration of Sport said it is halting all high-risk sports events that lack a clear oversight body, established rules and safety standards, according to a statement on its website.

The sports suspended include mountain and desert trail running, wingsuit flying and ultra-long distance races, the statement said.

The administration did not specify how long the suspension would last, but said it is taking a detailed look into the country's sports events to improve regulatory systems, strengthen standards and rules, and enhance safety.

It also ordered local authorities "not to hold any sports competitions unless necessary" and call off any event with safety risks in the lead-up to the Chinese Communist Party's centenary, which falls on July 1.

Authorities didn't say how many races will be affected by the suspension. According to the Chinese Athletic Association, 481 trail races and 25 ultra-marathons were held in 2019 -- more than a quarter of all long-distance running events in the country.

Marathons and trail races have exploded in popularity as China's rising middle class picked up the running bug in recent years. But industry insiders say the races are often poorly organized, lacking safety measures and contingency planning -- and sometimes plagued by injuries and deaths.

Trail races are often held in far-flung parts of the country that lag behind in development and resources. The deadly mountain race on May 22 took place in the remote countryside of Gansu, one of the poorest regions in the country.

Most of the victims, including some of the country's best long-distance runners, were poorly equipped for cold weather and died of hypothermia -- a dangerous drop in body temperature caused by prolonged exposure to bitter cold.

The tragedy shocked China's running community and prompted public outrage, with many questioning whether organizers had planned the race properly or prepared participants for the extreme weather.

Even before the announcement on Thursday, dozens of marathons and trail-running races had been cancelled or postponed across the country in the past two weeks, according to state media.

(06/03/2021) ⚡AMPby Nectar Gan

Ethiopian runner sets men’s 50K world record with 2:42:07 run in South Africa

Ketema Negasa broke the men's world record and South Africa's Irvette Van Zyl ran the second-fastest women's 50K in history

Ethiopia’s Ketema Negasa broke the men’s 50K world record on Sunday, running 2:42:07 at the Nedbank Runified race in South Africa. Negasa led the way as he and three other runners beat American CJ Albertson‘s previous record of 2:42:30. In the women’s race, Des Linden‘s recent 2:59:54 world record remained unbeaten, but South Africa’s Irvette Van Zyl ran a national record of 3:04:23, which is the second-fastest women’s result in history.

Negasa’s record

Negasa is primarily a marathoner, but he has never been able to match the necessary times to shine in Ethiopia. He owns a marathon PB of 2:11:07, a time that would rank him in the top 10 all-time among Canadian runners but isn’t even in the top 250 results in Ethiopian history. After his run on Sunday, though, it looks like ultras may be his forte.

It’s important to note that Albertson’s world record, which he set in November 2020, came on a track, while Negasa’s run on Sunday was on the road. Ultrarunning world bests are unique in this sense, because while Albertson and Negasa ran on completely different surfaces, their runs count in the same category of the 50K in general, as the International Association of Ultrarunners introduced a rule that eliminated surface-specific records in 2014. In other World Athletics-sanctioned events, the surface comes into play. For example, the 5K and 5,000m world records both belong to Uganda’s Joshua Cheptegei, but they’re two different times.

Negasa’s run worked out to an average per-kilometre pace of 3:15 for the full 50K, which helped him top Albertson’s result by 23 seconds. He crossed the line in first place, and he was followed closely by Machele Jonas, who also beat Albertson’s record with a 2:42:15 run. Third went to Mphakathi Ntsindiso in 2:42:18, and in fourth place was Kiptoo Kimaiyo Shedrack, who just beat Albertson’s record in 2:42:29.

Irvette Van Zyl run

Had the Nedbank Runified race been held a couple of months earlier, Van Zyl would have broken the women’s 50K world record. Since the race took place in late May, though, Van Zyl was late to the party, and her time is second-best to Linden’s. When she ran her race in Oregon, Linden became the first woman to break three hours over 50K, and she smashed Aly Dixon‘s previous record of 3:07:20.

While Van Zyl didn’t manage to beat Linden, she did crush Dixon’s result with her 3:04:23 finish, which is the new South African 50K record. Behind Van Zyl was Lilian Jepkorir Chemweno, who finished in second place in 3:05:00, which is now the third-fastest 50K in history.

(05/30/2021) ⚡AMPby Running Magazine

How shepherd saved runners in deadly China ultra-marathon race

A shepherd has been hailed as a hero in China after it emerged that he saved six stricken runners during an ultramarathon in which 21 other competitors died.

Zhu Keming was trending on the Twitter-like Weibo on Tuesday, three days after a 100-kilometre (60-mile) cross-country mountain race in the northwestern province of Gansu turned deadly in freezing rain, high winds and hail.

The incident triggered outrage and mourning in China, as questions swirled over why organisers apparently ignored warnings about the incoming extreme weather.

Zhu was grazing his sheep on Saturday around lunchtime when the wind picked up, the rain came down and temperatures plunged, he told state media.

He sought refuge in a cave where he had stored clothes and food for emergencies but while inside spotted one of the race's 172 competitors and checked to see what was wrong because he was standing still, apparently suffering cramps.

Zhu escorted the man back to the cave, massaged his freezing hands and feet, lit a fire and dried his clothes.

Four more distressed runners made it into the cave and told the shepherd others were marooned outside, some unconscious.

Zhu headed outside once more and, braving hail and freezing temperatures, reached a runner lying on the ground. He carried him towards the shelter and wrapped him in blankets, almost certainly saving his life.

"I want to say how grateful I am to the man who saved me," the runner, Zhang Xiaotao, wrote on Weibo.

"Without him, I would have been left out there."

Zhu has been feted in China for his selfless actions, but the shepherd told state media that he is "just an ordinary person who did a very ordinary thing".

Zhu rescued three men and three women, but regrets that he was unable to do more to help others who reportedly succumbed to hypothermia.

"There were still some people that could not be saved," he said.

"There were two men who were lifeless and I couldn't do anything for them.

"I'm sorry."

The tragedy has thrown a renewed spotlight on the booming marathon and running industry in China, with authorities ordering sports competitions to improve safety.

According to The Paper in Shanghai, five cross-country, marathon or other running races have been cancelled at short notice.

(05/29/2021) ⚡AMPUltra-Trail du Mont-Blanc officials confirm plans for 2021 in-person race

Organizers of the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc announced on Friday that their ultramarathon will be back this year after missing 2020 due to COVID-19.

The storied ultramarathon features multiple events, including the classic 171K UTMB race that takes athletes around Mont Blanc and through parts of France, Italy and Switzerland. Race organizers were able to confirm the running of the event after the French government released its latest COVID-19 guidelines, and it is officially locked in for August 23 to 29.

While the race is set to run later this year, there will be COVID-19 restrictions and guidelines in place for all racers. Like most mass participation races that have been held since the start of the pandemic, masks will be mandatory at the start and finish lines, and racers will be asked to wear them when they approach aid stations along the route. They will also be required to wash their hands as they pass through, and there will be no self-service at aid stations, which will help avoid the potential spreading of germs from each runner.

The race start will also feature waves, and crowds will be limited along the course. The number of spectators permitted may vary throughout the route, though, as it will be dependant on the rules of each town, region and country that runners pass through on the course. There will reportedly be other restrictions in place, but organizers have yet to finalize all of the details.

There’s also the matter of travel restrictions, which the race of course cannot control. The French government is set to introduce a “Sanitary Pass” on June 9, and this will allow outsiders from other European countries to visit France. For Canadians and other non-Europeans, organizers said the Sanitary Pass details are still being figured out, but they will keep all potential UTMB racers in the loop as the matter progresses.

Sanitary Passes will be mandatory for everyone participating in any French events of more than 1,000 people, and it requires individuals to have one of three things: proof of full vaccination, a recent negative COVID-19 test or a certificate of COVID-19 recovery. Anyone who does not qualify for a Sanitary Pass will be unable to get their bib ahead of the race.

(05/25/2021) ⚡AMPby Ben Snider-McGrath

North Face Ultra Trail du Tour du Mont-Blanc

Mountain race, with numerous passages in high altitude (>2500m), in difficult weather conditions (night, wind, cold, rain or snow), that needs a very good training, adapted equipment and a real capacity of personal autonomy. It is 6:00pm and we are more or less 2300 people sharing the same dream carefully prepared over many months. Despite the incredible difficulty, we feel...

more...Ethiopia´s Ketema Negasa sets men’s 50K world record with 2:42:07 run in South Africa

Ethiopia’s Ketema Negasa broke the men’s 50K world record on Sunday, running 2:42:07 at the Nedbank Runified race in South Africa. Negasa led the way as he and three other runners beat American CJ Albertson‘s previous record of 2:42:30. In the women’s race, Des Linden‘s recent 2:59:54 world record remained unbeaten, but South Africa’s Irvette Van Zyl ran a national record of 3:04:23, which is the second-fastest women’s result in history.

Negasa’s record

Negasa is primarily a marathoner, but he has never been able to match the necessary times to shine in Ethiopia. He owns a marathon PB of 2:11:07, a time that would rank him in the top 10 all-time among Canadian runners but isn’t even in the top 250 results in Ethiopian history. After his run on Sunday, though, it looks like ultras may be his forte.

It’s important to note that Albertson’s world record, which he set in November 2020, came on a track, while Negasa’s run on Sunday was on the road. Ultrarunning world bests are unique in this sense, because while Albertson and Negasa ran on completely different surfaces, their runs count in the same category of the 50K in general, as the International Association of Ultrarunners introduced a rule that eliminated surface-specific records in 2014. In other World Athletics-sanctioned events, the surface comes into play. For example, the 5K and 5,000m world records both belong to Uganda’s Joshua Cheptegei, but they’re two different times.

Negasa’s run worked out to an average per-kilometer pace of 3:15 for the full 50K, which helped him top Albertson’s result by 23 seconds. He crossed the line in first place, and he was followed closely by Machele Jonas, who also beat Albertson’s record with a 2:42:15 run. Third went to Mphakathi Ntsindiso in 2:42:18, and in fourth place was Kiptoo Kimaiyo Shedrack, who just beat Albertson’s record in 2:42:29.

Irvette Van Zyl run

Had the Nedbank Runified race been held a couple of months earlier, Van Zyl would have broken the women’s 50K world record. Since the race took place in late May, though, Van Zyl was late to the party, and her time is second-best to Linden’s. When she ran her race in Oregon, Linden became the first woman to break three hours over 50K, and she smashed Aly Dixon‘s previous record of 3:07:20.

While Van Zyl didn’t manage to beat Linden, she did crush Dixon’s result with her 3:04:23 finish, which is the new South African 50K record. Behind Van Zyl was Lilian Jepkorir Chemweno, who finished in second place in 3:05:00, which is now the third-fastest 50K in history.

(05/24/2021) ⚡AMPby Ben Snider-McGrath

Eliud Kipchoge wants to run ‘all major marathons’

Boston, New York, and Tokyo are on the GOAT marathoner's bucket list

Eliud Kipchoge has revealed he would like to run “all major marathons” in the remainder of his career.

Speaking to Gordon Mack on the Flotrack podcast, the GOAT marathoner said because he has already run Berlin, London, and Chicago, the remaining major marathons on his “bucket list” were Boston, New York, and Tokyo.

He said because he plans to focus firstly on the Tokyo Olympics this summer, before a busy autumn of marathons, he would “close” his bucket list before “jumping in” again on January 1 2022.

Kipchoge also suggested he might be interested in dabbling in ultrarunning for a fresh challenge.

“I would love to try 80km, 60km. I need to go to California and hike for six hours," he said. He added that he was looking forward to the next phase of his running after his professional career is over: “I’m really excited to approach life in another dimension,” he said, “to go up the mountains with different people, with different lifestyles.”

He said, “I’m really excited to instil inspiration in the youth of the whole world. To travel along the big cities, in every country if possible, to send positive vibes.”

Kipchoge was speaking to Flotrack ahead of taking part in NN Running’s MA RA TH ON virtual marathon relay this weekend. Like others taking part in the virtual race, he will run a 10.5km relay on May 22-23 which will be added to the efforts of three teammates to make up the full marathon distance.

(05/23/2021) ⚡AMPby Runner’s World

TCS London Marathon

The London Marathon was first run on March 29, 1981 and has been held in the spring of every year since 2010. It is sponsored by Virgin Money and was founded by the former Olympic champion and journalist Chris Brasher and Welsh athlete John Disley. It is organized by Hugh Brasher (son of Chris) as Race Director and Nick Bitel...

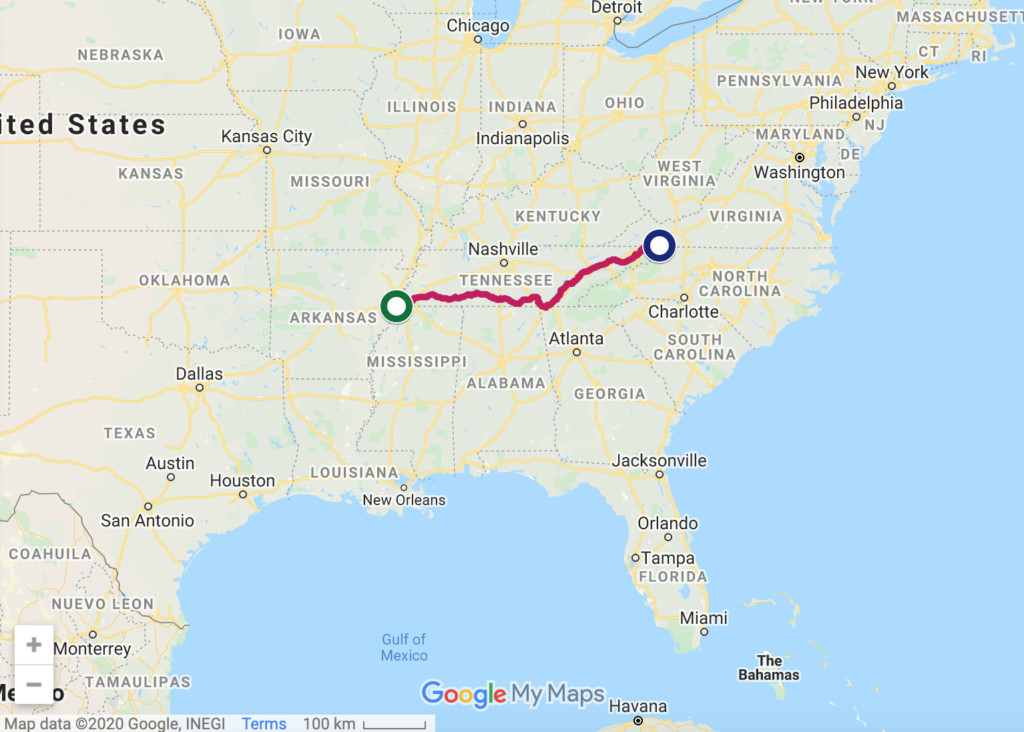

more...Canadian Ultrarunner Runs 1,000K in Fewer Than 10 Days to Win the Great Virtual Race Across Tennessee

After finishing in 148th overall in last year’s race, Morris was on a mission to win.

For the second year in a row, the Great Virtual Race Across Tennessee (GVRAT) has been won by a Canadian, and once again in a record-breaking performance.

Varden Morris, 50, who lives in Calagary, Alberta and is from Jamaica, completed the 1,000K distance (a little more than 621 miles) in 9 days and 23 hours, averaging more than 100K a day. Morris beat out fellow Canadians Matthew Shepard, 33, and Crissy Parsons, 40, who finished in 13 days and 15 days, respectively.

“Honestly, I’m in disbelief,” Morris told Runner’s World. “Just hearing stuff on social media about the magnitude of what I just did. I knew it was possible but after finishing and realizing that not many people have done what I’ve done, it baffles my mind.”

Last April, Barkley Marathons creator Gary “Lazarus Lake” Cantrell came up with the idea of hosting a virtual ultra, giving people four months to run twice the distance of the Last Vol State 500K—and more than 19,000 runners signed up. One of them was Morris, who went out with the fastest of the bunch, but due to lack of training, he picked up a few injuries and was forced to slow down. He finished 148th overall.

After that, Morris decided he wanted to win the 2021 race, so he studied the training methods of successful ultrarunners and increased his mileage. By the start of 2021, he was running about 14 miles a day for a week before upping that mileage by four miles to his daily total until he reached a max of 36 miles a day. In March alone, he covered 965 miles.

On May 1, when GVRAT finally began, Morris set out to not only win, but to also finish in fewer than 10 days.

“My strategy was to run as close to possible to the same average distance every day,” he said. “Most people try to put in most miles in the first few days. My plan was to be consistent. I went a little above my average the first day by 10 percent, but I was doing mostly the same miles every day.”

Morris ran around his neighborhood in Calgary, with a routine of running for six hours and resting for five. He rotated through three pairs of Asics shoes, and for fuel, he focused on solid foods like boiled eggs with veggies, Jamaican sweet potato pudding, toto (a Jamaican pastry), and fruit, such as grapes, bananas, oranges, and watermelon.

No day was easy. Morris said he often found himself contemplating if he would complete the run he was on. On the first day, he picked up a groin injury that lasted a couple days. Another day, he ran through rain and hail with winds over 25 mph.

“Every minute was important,” he said. “Each day was more and more difficult. There was a sense of uncertainty if I would finish. It wasn’t something easy. It was something very difficult. We just took it one day at a time.”

When Morris woke for his final push of 44 miles, he was hurting but he knew he was ahead of his fellow Canadians. His wife, who also served as his crew chief, joined him for the first 15 miles of that final push, and his daughter ran the final four miles with him.

Celebrations included a big meal at home of meat and veggies and some non-alcoholic wine. With the record in hand, Morris plans on running back across Tennessee; part of the GVRAT format allows runners to run back across Tennessee as many times as they like during the four-month period.