Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson in Mountain View, California USA and team in Thika Kenya, La Piedad Mexico, Bend Oregon, Chandler Arizona and Monforte da Beira Portugal. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Over one million readers and growing. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Running Retreat Kenya. (Kenyan Athletics Training Academy) in Thika Kenya. Opening in june 2024 KATA Running retreat Portugal. Learn more about Bob Anderson, MBR publisher and KATA director/owner, take a look at A Long Run the movie covering Bob's 50 race challenge.

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

DIRK HELLER WINS 300 MILE RACE

Dirk Heller from Germany is our overall winner for the MYAU 300 mile race. Second came Josh Tebeau (USA) and Elise Zender (Germany). Those two are also a couple and a race like this is a very serious stress test for any relationship.

They did it in style! Josh and Elise also entered in the team category placed 1st team. They connected their entry with a fundraiser effort for We Can Run Project which is looking to contribute to the higher education of female students in Sierra Leone. Last and certainly not least came Dirk Groth from Australia who said it was incredibly hard, especially the road from Pelly Farm to Pelly Crossing – due to a lot of fresh and unpacked snow. But he made it before the cut-off of 8 days and I think he liked it ?

Yukon Artic ultra 300 miler

The Yukon Arctic Ultra is the world's coldest and toughest ultra! Quite simply the world's coldest and toughest ultra. 430 miles of snow, ice, temperatures as low as -40°C and relentless wilderness, the YUA is an incredible undertaking. The Montane® Yukon Arctic Ultra (MYAU) follows the Yukon Quest trail, the trail of the world's toughest Sled Dog Race. Where dog...

more...The Cold, Hard Reality of Racing the Yukon Arctic Ultra

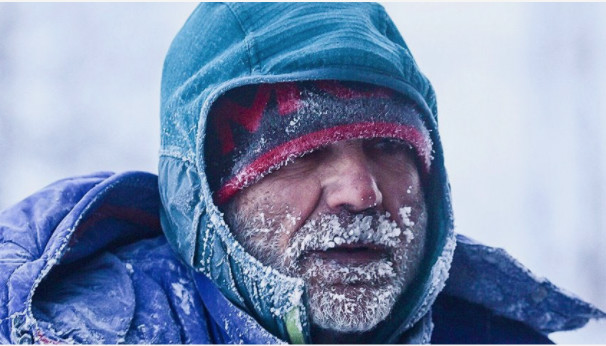

Temperatures were brutally low at this year’s running of the 300-mile competition, and one frostbitten competitor may lose his hands and feet. Is this just the price of playing a risky game, or does something need to change?

Roberto Zanda left the Carmacks checkpoint of the Montane Yukon Arctic Ultra just before noon on February 6. He was at least 150 miles into the 300-mile race—he’d already been slogging down a dogsled trail through the Yukon backcountry for more than five full days. Temperatures had plunged below minus 40 Fahrenheit on the first night out of Whitehorse, the small Yukon city where the race began; along the race course, temperatures consistently ranged from the minus 20s to the minus 40s.

In short, conditions were brutal. Of the eight racers who’d begun the 100-mile version of the variable-length event, just four had finished. Of the 21 who’d started the 300-miler, only the 60-year-old Zanda and two others remained. Most of the rest had scratched with frostbite or hypothermia.

When Zanda left the checkpoint, hosted in a village rec center, a race medic wrote on the event’s Facebook page that the racer had paused only for “a short rest and a big meal. He was looking very strong.”

Just over 24 hours later, Zanda was in a helicopter, being rushed to Whitehorse General Hospital with hypothermia and catastrophic frostbite, lucky to be alive. He now faces the likely amputation of both hands and both feet. What went wrong?

This was the 15th running of the Yukon Arctic Ultra, an annual race in which competitors choose their distance—marathon, 100 miles, 300 miles, or, every second year, 430 miles—and their mode of transportation: a fat bike, cross-country skis, or their own booted feet. Race organizer Robert Pollhammer, 44, who runs an online gear store in his native Germany, started the event in 2003 after being involved with Iditasport, a similar event on the Alaskan side of the border.

The Yukon race takes place on part of a trail built each year by the Canadian Rangers for the Yukon Quest, a 1,000-mile dogsled race, and it’s as much a feat of logistics as it is an athletic contest. It’s continuous, not a stage race; competitors are self-sufficient, carrying all their camping and survival gear, spare layers, food, and water in sleds they pull behind them. Temperatures are cold enough to kill, and it’s dark for roughly 14 hours every day. Nonetheless, eager ultra racers travel from around the world for the event, paying anywhere from $750 to $1,750 USD to enter (depending on when they register and the distance they’re attempting), plus the cost of flights, hotel, and gear. The total can easily add up to $5,000 or more.

The entrants tend to be experienced ultra and adventure racers; many athletes have already completed events like the Gobi March or the Marathon des Sables. Most competitors come from Europe, although this year’s race also saw entrants from South Africa and Hong Kong. The race organization offers a survival course a few days beforehand—a crash education in moisture management, layering, and cold-weather injuries. Generally speaking, the racers are accomplished athletes, but they may not have extensive experience with severe cold. The challenge lies in keeping themselves safe while moving through the Yukon’s remote, frigid backcountry.

The race is billed as “the world’s coldest and toughest ultra,” and there have been plenty of serious injuries before: flesh blackened by frostbite, frozen skin peeling off racers’ faces like wax, and bits of fingers and toes lost to amputation. But what happened to Zanda is by far the worst medical outcome yet, and it has shocked former racers, event organizers, and fans. It has also led to discussions and debates, often heated, about where a race organization’s responsibilities end and a racer’s personal assumption of risk begins.

As Zanda moved out of Carmacks, his Spot tracker showed him clipping along steadily at around three miles per hour. Between 3 p.m. and 9 p.m., his beacon’s transmissions became more erratic—but that’s fairly normal in the Yukon, where satellite signals can be weak or inconsistent. Between 9 and 10 p.m., the problem cleared up and the Spot began sending signals every few minutes.

The last blip came in at 10:08 p.m., at route mile 189.7, and then the device went into sleep mode. After a strong ten-hour, 25-mile push from Carmacks, Zanda appeared to have stopped to camp for the night.

In the morning, as the sun rose, his tracker still hadn’t moved. The race crew wasn’t concerned yet—Zanda had taken a 12-hour rest once before during the race, as had some other athletes. At 9:32 a.m., Pollhammer posted on Facebook that two volunteer trail guides were headed out to check on him. “His Spot has not been sending for a long time now. Once we have news I will let you all know.”

The trail guides are the race’s safety net, patrolling hundreds of miles by snowmobile to check on the athletes and, when necessary, evacuate them from the course. They motored down the trail toward Zanda’s Spot location, but when they got there, in late morning, they found only the racer’s harness and sled, loaded with a tent and sleeping bag, a stove and fuel, and—crucially—the Spot device. Zanda was gone.

They called back to Pollhammer, who contacted the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and then they began searching the area, looking for some sign of where the racer might have left the packed trail and wandered into the forest. The Mounties were about to launch a search of their own when the call came in: Zanda had been found. A helicopter was dispatched and landed near him. The trail guides, advised by the incoming medical team, did what they could to care for Zanda while they waited. As Pollhammer put it in an email to me: “No time was lost.”

A few days later, Zanda spoke to a Canadian television reporter from his hospital room in Whitehorse. He wore a pale-green gown, and his hands were heavily bandaged, nearly up to his elbows. His feet and shins were the same. He said he’d left his sled behind to go look for help because his feet were freezing up. He and his family members have also told race organizers that Zanda had lost the trail and went in search of the next marker, leaving the sled behind while he scouted.

Hypothermia must have already had Zanda in its grip by then, muddying his mind and compromising his decisions. His sled was his lifeline, containing everything he needed to stay alive and the only tool he had to call for help. He wandered through the cold and dark all night while the sled sat on the trail, sending out a reassuring beacon to the world that all was well.

I competed in this year’s Yukon Arctic Ultra—my first attempt—and I didn’t last long. Twenty-two hours in, suffering from frostbite on three fingertips, I scratched from the event, one of four 100-mile racers who decided to quit.

I never met Zanda, though for all I know we could have been standing side-by-side at the start line. On the afternoon of day one, he left the first checkpoint 19 minutes ahead of me. That night, I passed by as he bivied on the side of the trail. A couple hours later, I put up my own tent, crawled inside, and was trying to change into dry clothes with my hands briefly exposed. That was long enough for frostbite to set in.

Early the next morning, Zanda and two other racers passed my tent. I heard them go by but didn’t call out. I was waiting until daylight to push the help button on my Spot. I’ve thought about those encounters a lot since I learned about what happened to Zanda. It’s impossible not to hear his story and ask: Could that have been me?

Easily. I knew when I signed up for the race that amputations, or even death, were among the potential consequences. At such low temperatures, exhausting yourself to the degree required to complete an ultramarathon is a good way to erase whatever thin margin of safety you’ve managed to create. But while some of my friends had concerns, I wasn’t really worried. That disconnect is what allows many of us to put ourselves in these situations.

Zanda wasn’t the only person hospitalized. Nick Griffiths, another 300-mile racer, scratched on day two. The frostbite on his left foot had become severe by the time he was whisked from the trail to a remote checkpoint for eventual evacuation to Whitehorse. Griffiths spent five days in the hospital, and he will eventually lose his big toe and two others next to it. (To preserve as much healthy tissue as possible, doctors will allow the toes to “self-amputate,” meaning that the dead tissue will simply fall off.) Losing the big toe, in particular, could have a serious impact on Griffiths’ future ability to walk, hike, and run.

“I’m hoping I’ll be all right,” he told me from his home in England, where he’s been reading up on athletes who’ve lost toes. “I’m not expecting to be able to go and do ultras or things like that, but there’s other challenges. It’s not ideal, but there’s no point jumping up and down about it. It’s done.”

I’m not sure I could muster the same acceptance if I were in Griffiths’ position, let alone Zanda’s. Understandably, the Italian racer’s friends and family are extremely upset. In the days after his rescue, the race’s Facebook page filled up with furious comments from people demanding to know how this could have happened, why Zanda wasn’t checked on sooner, why the race hadn’t been canceled entirely when the weather refused to relent. Zanda’s wife, Giovanna, wrote, in Italian, “It’s been too many hours before you decided to verify what happened. He didn’t die by miracle.” His brother, Paolo, posted, “Why they promise you safety when they do not care about you?” To which Pollhammer replied, “Nobody promises safety.”

That much is certain. The waiver I signed when I filed my registration paperwork last summer listed the risks I was assuming as including but not limited to “dehydration, hypothermia, frostbite, collision with pedestrians, vehicles, and other racers and fixed or moving objects, sliding down hills, overturning of ice-rocks, falling through thin ice, avalanche, dangers arising from other surface hazards, equipment failure, inadequate safety equipment, weather conditions, animals, the possibility of serious physical and/or mental trauma and injury, including death.”

Still, even as we sign our lives away, participating in an organized race may provide us with an illusion of safety in a way that an independent backcountry trek might not. If so, I suppose it becomes our job to tear down that illusion and make clear-eyed choices about the risks. That’s easier said than done, of course.

Throughout the aftermath of this year’s race, Pollhammer has remained calm as he answered his critics, walking the fine line of showing empathy for Zanda and his family while making it clear that he believes the error was the racer’s. Initially he seemed shaken, unsure about running the event again next year, but he has since announced the 2019 dates. I asked Pollhammer if, with the benefit of hindsight, he would do anything differently. He said that the rules and safety procedures evolve almost every year, and next year will likely be no different. But there are limits to what he can do, no matter how much he tweaks his protocols

“We can increase the list of mandatory gear, make people carry a sat phone, warn athletes even more so than we do now,” Pollhammer said. “We can do many things. However, we won’t be able to make sure people don’t get hypothermic and start making mistakes when they are out there. It they don’t act, or if they act too late, it will always mean trouble. I wish I could take that away from them, but it is impossible.”

Or as Nick Griffiths put it, “I can’t blame anybody for it—it was my own fault.”

As for Zanda, he told the CBC that he’ll be back out racing again—on prosthetics, if need be.

(02/21/2021) Views: 1,095 ⚡AMPYukon Artic ultra 300 miler

The Yukon Arctic Ultra is the world's coldest and toughest ultra! Quite simply the world's coldest and toughest ultra. 430 miles of snow, ice, temperatures as low as -40°C and relentless wilderness, the YUA is an incredible undertaking. The Montane® Yukon Arctic Ultra (MYAU) follows the Yukon Quest trail, the trail of the world's toughest Sled Dog Race. Where dog...

more...Tibi Ușeriu has finished the Yukon Arctic Ultra race and said The road seemed at one point without end

Fabian Imfeld from Switzerland was able to maintain his comfortable lead all the way to the finish line. After a stay at Pelly Farm that Fabian considers his home away from home, he went back to the Pelly Crossing Finish line. It has been really great to see him come in. All the way he had done very well. Always positive and in a good mood. Fabian had already been with us last year and had experienced issues with a bit of frostbite which meant he could not finish. Not this time! Congratulations!

Tiberiu Useriu has got a similar story. He tried the 430 last year and got very bad frostbite – even though he had already considerable experience with cold weather races. I was very happy to see that, instead of trying to overtake Fabian, which I am sure he wanted with all his heart, he actually took the rest his body needed. Lesson learned. Tibi finished. Zero problems with frostbite this time.

The Romanian also has a very interesting story and I think it is okay if I share it here. In his home country he is famous for his athletic achievement but also his life change. The short version is that he had a very difficult youth and I am sure a lot of people would have thought that his entire life would go the wrong way. A lost case for society. He stumbled and fell. Tibi realised he needed to change and he got up again. Now he is helping kids in Romania who are faced with the same or similar problems to get back on track. Doing these races he can show them that anything is possible. And he is leading a project with a great team of people to create a permanently marked long distance hike trail in Romania. An exciting project that creates jobs and will help with tourism. Congratulations, Tibi! And good luck with your work!

As those two were approaching the finish line we had still hopes that Patrick O Toole and Paul Deasy from Ireland would also get to Pelly. However, Patrick had to be pulled at McCabe due frostbite on a finger. Paul originally left that checkpoint but about 10 km in he experienced stomach problems and just could not get warm. So, he made the right decision and did not continue.

All athletes and crew arrived safely back in Whitehorse. Some hours ago we had a very nice little party at the Coast High Country Inn. Trail stories were exchanged and I have seen a lot of happy faces.

Safe trip home everyone!

(02/09/2020) Views: 1,384 ⚡AMPYukon Artic ultra 300 miler

The Yukon Arctic Ultra is the world's coldest and toughest ultra! Quite simply the world's coldest and toughest ultra. 430 miles of snow, ice, temperatures as low as -40°C and relentless wilderness, the YUA is an incredible undertaking. The Montane® Yukon Arctic Ultra (MYAU) follows the Yukon Quest trail, the trail of the world's toughest Sled Dog Race. Where dog...

more...Ultra runners are prepared for 2020 Yukon Arctic Ultra

On January 30 at Shipyards Park, more than 60 athletes from 16 nations will converge on Whitehorse to begin the Montane Yukon Arctic Ultra, one of the coldest, toughest, ultramarathons in the world.

Since 2003, the Montane Yukon Arctic Ultra (MYAU) has been held every February along the Yukon Quest Trail – the route of the 1,000-mile sled dog race.

A cumulative total of nearly 900 hardy souls have toed the start line in Whitehorse next to the Yukon River to cover their choice of four distances along this brutally cold and challenging trail, with a marathon, 100 and 300 mile races.

Every second year there is also a 430 distance, which is the case again in 2021. In 2020 an expected 65 athletes from 16 countries will compete, with more than half signed up for the 300-mile race.

The 300-mile race sees athletes travel to Pelly Farm, there they will leave the river to turn around and go to Pelly Crossing on the farm road.

“Once again we have an amazing race roster with great athletes from all over the world,” said Robert Pollhammer, MYAU race director. “It’s a perfect mixture between veterans, newcomers and athletes returning to finish unfinished business. As always, I keep my fingers crossed that they all reach their respective goals.”

Athletes can complete their chosen distance either on foot, fat bike, or cross country skis.

Shelley Gellatly is a local racer and is a 300-mile finisher. This year, she will attempt the trek to Pelly Crossing again, this time on skis.

Gellatly has been involved in the race since it’s inauguration and was inspired to try it as a way to see the Yukon Quest trail.

“I did it the first time in ‘03 because I wanted to see the trail,” said Gellatly. “I originally thought I would try and mush the trail but realized I didn’t have the cash or the knowledge and thought this would be a great chance to see it.

“I’ve been involved every year. It’s really fun and interesting.”

During the race, competitors are expected to be self-sufficient, towing food and shelter behind them in heavily laden sleds called ‘pulks’ and melting snow to provide water.

Night temperatures can reach as low as -50 C, which when coupled with windchill and sheer physical exhaustion can be not just challenging, but extremely dangerous. Situations which under normal circumstances would be inconsequential can become life-threatening.

This year is the 17th edition of the race. There have been 891 participants, including 2019 so far. Forty-one nations have been represented. In order of most representation are Canada, UK, Germany, Italy, United States and Denmark.

(01/18/2020) Views: 1,454 ⚡AMP

by John Tonin

Yukon Artic ultra 300 miler

The Yukon Arctic Ultra is the world's coldest and toughest ultra! Quite simply the world's coldest and toughest ultra. 430 miles of snow, ice, temperatures as low as -40°C and relentless wilderness, the YUA is an incredible undertaking. The Montane® Yukon Arctic Ultra (MYAU) follows the Yukon Quest trail, the trail of the world's toughest Sled Dog Race. Where dog...

more...Paul Fosh from Monmouth will have to endure frostbite-threatening minus-30C temperatures in the arduous Yukon Arctic Ultra race

Paul Fosh from Monmouth will have to endure frostbite-threatening minus-30C (-22F) temperatures in the arduous 430-mile Yukon Arctic Ultra race in north west Canada, with just 13 days to finish the trek.

He’s no stranger to the Arctic Circle, having completed two previous races in the Yukon, including the Ultra 300-mile course in 2016, but this will be his longest yet.

The 52-year-old father-of-two, who runs Paul Fosh Auctions, said: “I love the challenge, both physical and mental but know that probably less than a quarter of those entering the race will complete it.”

Last year, because of the extreme conditions and the toll it takes on the body, only one person finished the 300-mile race.

And tragically, experienced ultra race athlete Roberto Zanda from Italy lost both his lower legs and his lower right arm due to catastrophic frostbite damage sustained during the race.

Property auctioneer Paul said: “Over time, you become thrilled to be part of the small percentage that have completed the race.

“I have invested a lot of time, effort and money to get myself out there and I want to do myself proud. I don’t ever want to fail at anything I do.”

All of the 441 entrants, 41 of them in the 430-mile race, are entirely self-sufficient and carry all their belongings, food, clothes, tent and other equipment on a sled called a pulk.

“A lot of people underestimate the mental challenge," says Paul.

“There are those of us that almost enjoy the pain, but if it was too easy there would be no pleasure at the end.”

He is aiming to finish within 10 days by averaging around 43 miles a day, and said: “I know my level of fitness is right to achieve this goal, I have been doing a lot of training for this one as it is the most demanding race I’ve ever done.

“Someone once told me to train hard and play easy. Admittedly, that was in the context of rugby, but I think it can apply to this too.”

Despite the 13-day time limit on the race, there will be very little time for sleep, which means that competitors will spend a lot of time walking both day and night.

“Walking in the daylight is much easier psychologically because you’ve got such fantastic scenery to look at.

“At night, you could be anywhere, you’ve just got your headtorch beam to follow.

“One of my biggest challenges is complacency."

(01/30/2019) Views: 2,161 ⚡AMPYukon Artic ultra 300 miler

The Yukon Arctic Ultra is the world's coldest and toughest ultra! Quite simply the world's coldest and toughest ultra. 430 miles of snow, ice, temperatures as low as -40°C and relentless wilderness, the YUA is an incredible undertaking. The Montane® Yukon Arctic Ultra (MYAU) follows the Yukon Quest trail, the trail of the world's toughest Sled Dog Race. Where dog...

more...Ultra runner Diane Van Deren says running is her outlet, her medicine and she doesn't say I can't anymore

Former professional tennis player Diane Van Deren was diagnosed with epilepsy in her 30s. For most people, this would not only end their career as a professional athlete, but also place major constraints on their daily routines and personal lives. That was not the case, however, for Van Deren. She not only persevered and ultimately found a way to get around her epileptic seizures – she did the extreme, opting to have a piece of her brain surgically removed to end her decade-long struggle with the disorder. After healing, Van Deren began running, trying her luck at a 50 mile race at age 42. Shortly thereafter, she ran her first 100-mile race and won it, right out of the gates. Since then, she has won the infamous Yukon Arctic Ultra, a 430-mile ultra footrace pulling a 50-pound sled through temperatures below 50 degrees for eight days, and set a record for the 1,000-mile Mountains to Sea Trail, where she traversed the state of North Carolina in just over 22 days. She’s been a professional endurance athlete with The North Face for the past 16 years. Van Deren, 58, is a wealth of positivity despite some of the obstacles she’s faced, including at times losing her sense of time and direction as a result of the surgery. “Running was my outlet, my medicine, the way to create a safe place for me,” Van Deren says. “When you are trying to be a wife and a mom, and you don’t know when the next seizure is going to come, it’s living in constant fear of ‘When is the beast going to hit me?’ When that changes and you get your health back, how can you not be grateful? I don’t say ‘I can’t’ or ‘I’m afraid’ anymore, or ‘What if?’ Now the way I look at life is, ‘I can’ – I can do it, I can try. So that’s where the gratitude comes from. I’ve walked it, I’ve lived it, I’ve been in a horrific situation, and through the brain surgery I now have wealth. I have my health.” (05/10/2018) Views: 1,859 ⚡AMPInspirational Stories

Athletes declare that they “learned so much†about themselves in the course of these events says Eva Holland

The Montane Yukon Arctic Ultra is billed as the world’s coldest and toughest ultramarathon. When I signed up for the 2018 race, I expected the race to end like this. I travel across 100 miles of frozen, snow-packed trail through the Yukon wilderness, towing a sled loaded with everything I need to survive. I arrive, exhausted but elated, at the finish line; my friends greet me there with a cold beer. I kneel, pull down my frost-covered balaclava to kiss the finish-line banner, and can barely stand up again afterwards. I was in the best shape of my life; my winter-travel systems had been well and truly stress-tested. And I understood, now, why the racers I’d interviewed four years earlier kept coming back for more punishment, even if they hadn’t been able to articulate it to me then. I’d always have the memories of that giant moon swinging above me as I traveled up the frozen Takhini. But, had my frostbitten fingers not thwarted me, could I have finished? I still didn’t have the answer to my question, the riddle of the finish line and the failure. I still don’t. The only way to find out, I suppose, is to try again. (03/16/2018) Views: 1,578 ⚡AMPOnly 32 people have finished the Arctic Ultra Race Ever

Romanian endurance athlete Tibi Useriu has “a commanding lead†in this year’s Arctic Ultra, one of the toughest ultra-marathons in the world. Useriu won the Arctic Ultra in 2016 and 2017 and is now the only Romanian still competing in the race, after Avram Iancu, Polgar Levente, and Florentina Iofcea all had to drop out. “As this report is written, Tibi Useriu, previous champion and all round legend, has a commanding lead on the ice road having passed through Mid Peel River check point and well on his way to Aklavik." The race takes place in extremely harsh conditions, at temperatures ranging between -50 and -30 degrees Celsius. Throughout the nine editions of the race, only 32 participants made it to the finish line. The race started on March 9 in Yukon. It will end at Tuktoyaktuk, on the banks of the Arctic Ocean (03/12/2018) Views: 1,959 ⚡AMPEpic Running Adventures

This race is considered the Coldest Ultramarathon on the Planet

The Yukon Arctic Ultra conditions sound like that of a frozen tundra nightmare in what could be the Canadian equivalent of the Barkley Marathons. Race director Robert Pollhammer posted on Facebook on Thursday that South African Jethro De Decker was the lone runner to make it to the finish line of the 300-miler (483K). Temperatures were at or below -40 for almost the entire week that the race went on. “It was a tough year, Many of the participants of the 300-miler, were taken off course and treated for frostbite and/or hypothermia at the hospital," says Robert. For sure this is the Coldest Ultramarathon... (02/08/2018) Views: 1,757 ⚡AMPEpic Running Adventures