Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

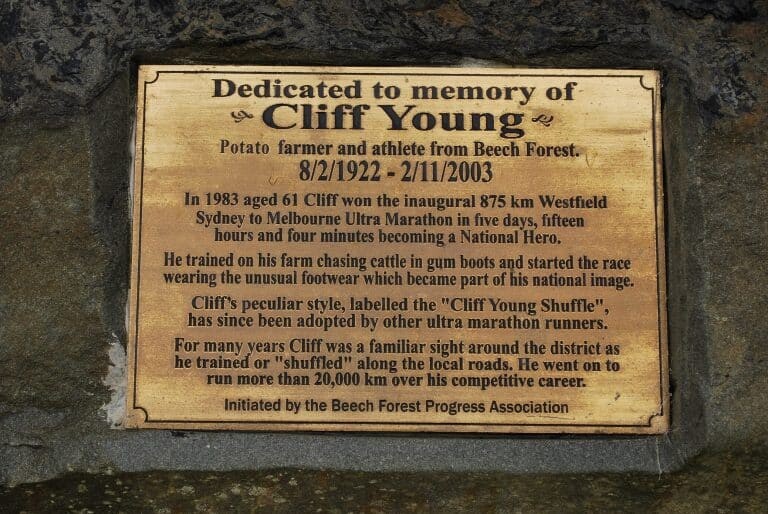

61 Years Old, in Gumboots, and Unstoppable: The Legend of Cliff Young

Sydney, Australia 1983 - When the Sydney–to–Melbourne Ultramarathon assembled its field, Cliff Young looked like a mistake.

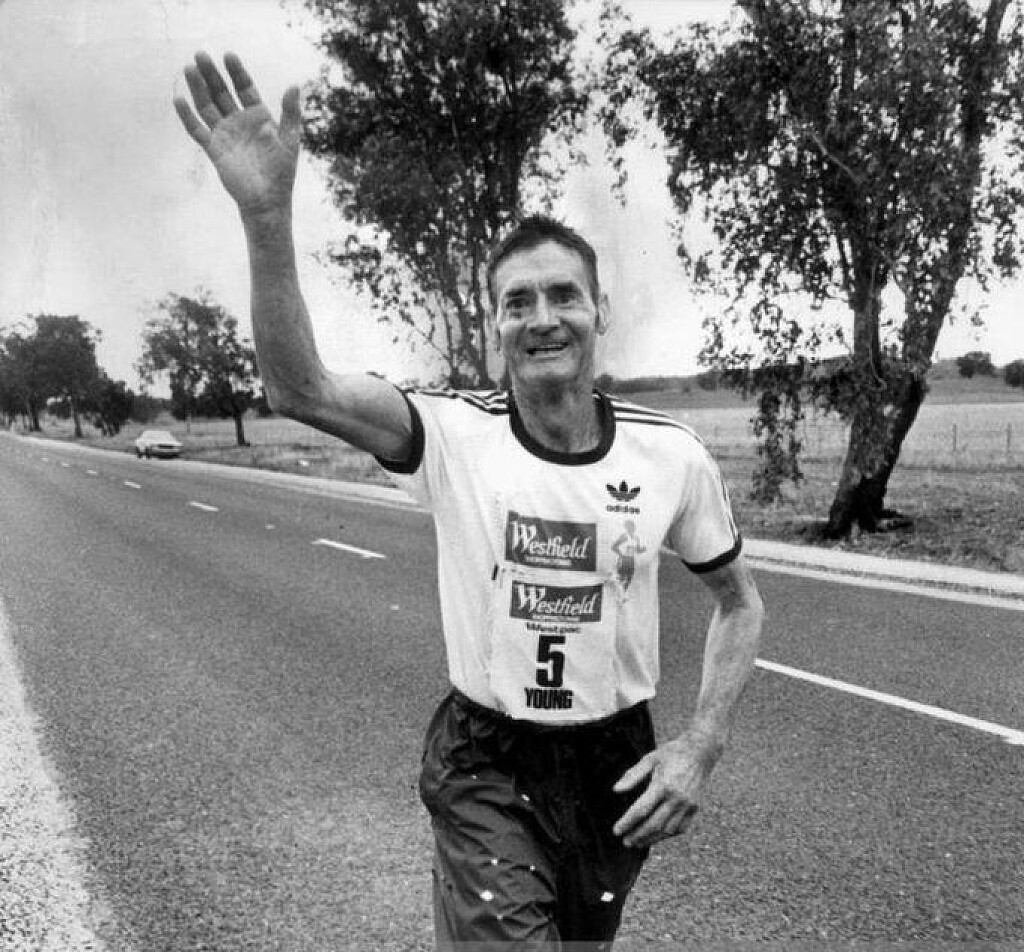

Around him stood elite endurance runners—lean, sponsored, wrapped in the best gear money and sports science could provide. Then there was Cliff: a 61-year-old potato farmer from rural Victoria, dressed in overalls, a faded cap on his head, and rubber gumboots on his feet. He looked less like a professional athlete and more like someone who had wandered in from the farm after finishing his chores.

The race itself was unforgiving. Eight hundred and seventy-five kilometers (544 miles) of continuous road running, stretching over five to six days, with little margin for error. Even experienced ultramarathoners considered it one of the toughest endurance events in the world. Many believed it demanded youth, precision training, and carefully managed recovery.

Cliff had none of that.

When reporters asked why he thought he could compete, his answer was simple and unpolished. Growing up on a large sheep farm, he explained, meant running for days at a time to round up animals during storms—sometimes without sleep, sometimes without stopping, just moving until the work was finished.

The smiles he received were polite. The skepticism was private but absolute.

Most expected him to drop out early.

At the starting gun, the elite runners surged forward with long, powerful strides, quickly stretching the field. Cliff moved too—but not in the way anyone expected. He shuffled, taking short, economical steps, arms barely swinging, his gumboots slapping softly against the pavement. Within minutes, the professionals disappeared down the road, and Cliff was left behind, alone.

Spectators laughed. Drivers stared. Commentators treated him as a novelty.

Then night came.

As darkness fell, the leading runners followed standard ultramarathon practice. They stopped to rest, sleeping several hours in hotels to recover before continuing. Cliff didn’t stop—not out of bravado, but because no one had told him that sleep was part of the strategy.

On the farm, storms didn’t pause for nightfall. You kept going until the job was done.

So Cliff kept shuffling through the dark.

By morning, something unexpected had happened. Cliff was still moving—steady, unchanged—while others had been resting. Hour by hour, night after night, the pattern repeated. The younger athletes battled fatigue, blisters, and breakdown. Their pace rose and fell. Cliff’s never did.

By the third day, disbelief turned into fascination. Radio stations began tracking his progress. News crews followed the quiet farmer who refused to stop. His awkward shuffle—once laughed at—was proving remarkably efficient, conserving energy and reducing impact over immense distances.

On day four, Cliff Young took the lead.

The moment felt unreal. A 61-year-old farmer with no formal training was dismantling everything people thought they knew about endurance racing. While others slept, he advanced. While others struggled, he remained patient.

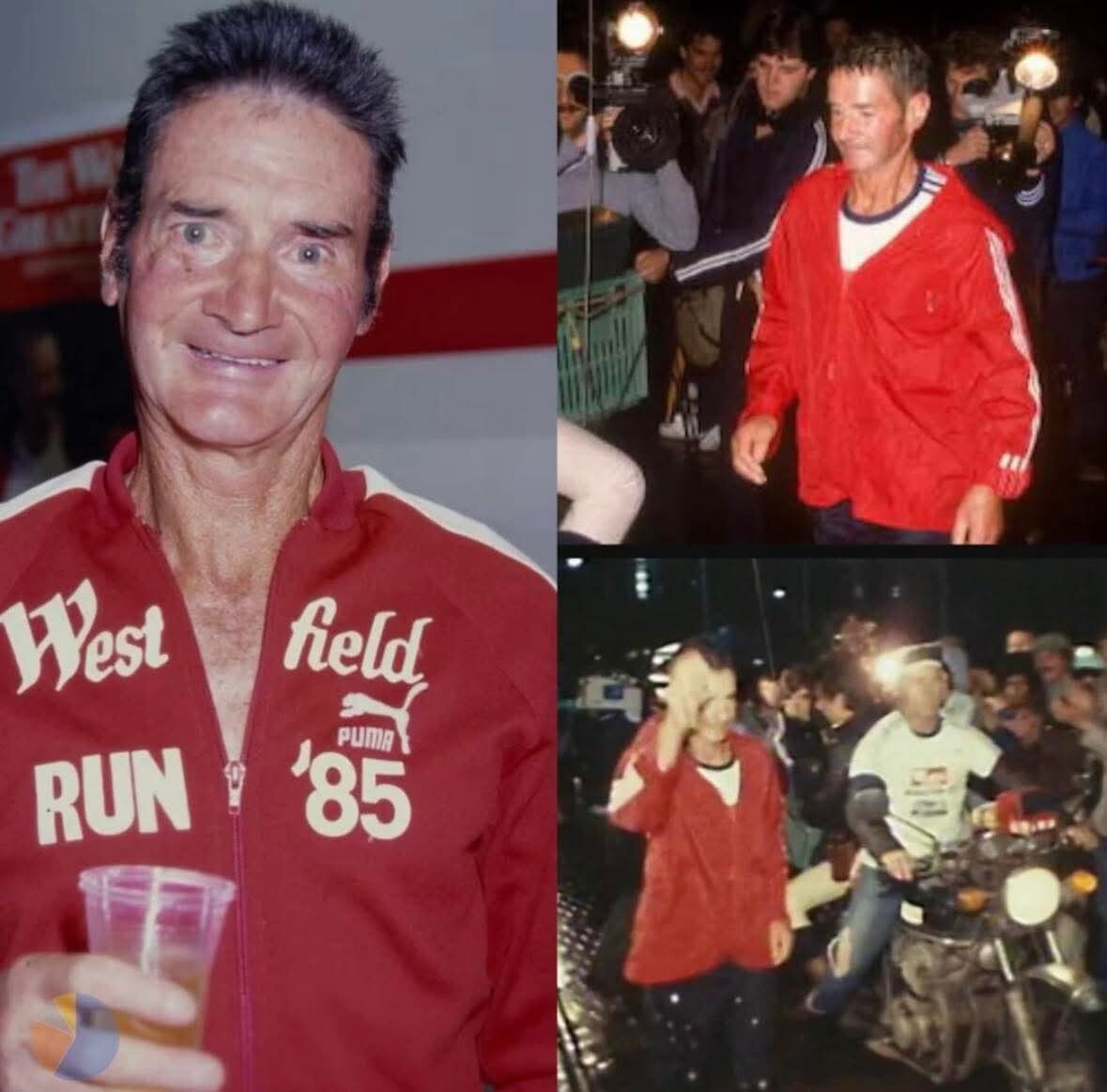

By day five, as the course approached Melbourne, crowds lined the roads. They weren’t cheering for a polished champion. They were cheering for persistence itself.

Cliff crossed the finish line first.

His time—5 days, 15 hours, and 4 minutes—shattered the previous course record by almost two full days. He finished nearly ten hours ahead of the next competitor, an elite athlete half his age.

When officials handed him the $10,000 prize, Cliff was surprised. He hadn’t known there was prize money. He said he had only come to run. Then he gave the entire amount away, sharing it among the runners who finished behind him because, in his view, they had all endured the same suffering.

Cliff Young’s victory changed ultramarathon running forever. His shuffling gait—later known as the “Young Shuffle”—proved to be an efficient endurance technique and is still referenced today. His approach to rest challenged long-held assumptions about human limits.

He continued racing into his seventies, always humble, always smiling, always shuffling.

When Cliff Young passed away in 2003 at the age of 81, Australia mourned not just a champion, but a reminder: that age is not a boundary, that heart matters more than equipment, and that sometimes the people who don’t know the rules are the ones who redefine what’s possible.

Cliff Young didn’t win because he was faster.

He won because he never knew he was supposed to stop.

by Erick Cheruiyot for My Bestruns.

Login to leave a comment