Running News Daily

Running News Daily is edited by Bob Anderson. Send your news items to bob@mybestruns.com Advertising opportunities available. Train the Kenyan Way at KATA Kenya and Portugal owned and operated by Bob Anderson. Be sure to catch our movie A Long Run the movie KATA Running Camps and KATA Potato Farms - 31 now open in Kenya! https://kata.ke/

Index to Daily Posts · Sign Up For Updates · Run The World Feed

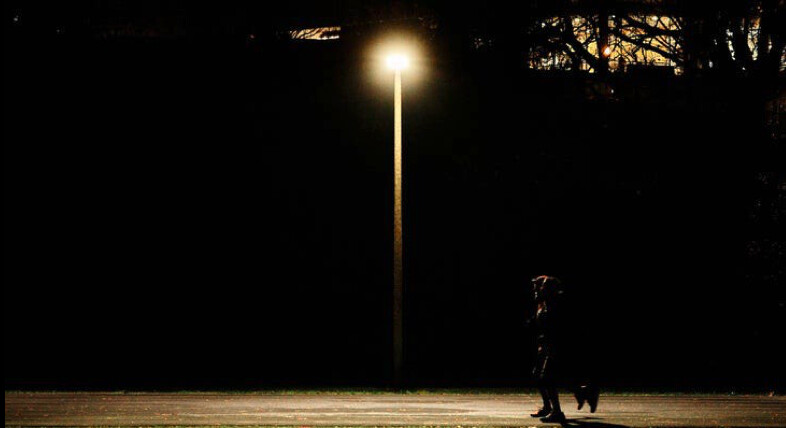

Running Through the Night to Confront the Darkness of Substance Addiction

Ultrarunner Yassine Diboun found his own unique way to help those in recovery move through darkness together. It’s working.

Since 2020, Yassine Diboun has made it a point each year to black out one square on his calendar with a Sharpie.

It’s a gesture to signify that on this day, typically set around the winter solstice, this 45-year-old ultrarunner and coach from Portland, Oregon, won’t run during the day, as he does most every other day of the year. Instead, he’ll watch a movie with his daughter, Farah, or cook a meal with his wife, Erica, eagerly waiting for night to fall. Because that is when the action starts.

Diboun has become a fixture in Portland’s trail running scene, a Columbia-sponsored runner and one of the most electric and positive forces in the U.S. ultrarunning scene today. He is also an athlete in active substance addiction recovery since 2004.

And here, at the confluence of endurance and recovery, is where Diboun enacts an annual tradition in Portland called Move Through Darkness. From sundown to sunup, Diboun runs through the evening, covering a route that connects city streets with trails in Forest Park while accompanied by dozens of other runners.

On December 9, Diboun will start his fourth-annual Move Through Darkness run. It may exceed 70 miles. It may not. That’s not really the point, though in some sense it is, for the more miles he runs, the more pledge-per-mile dollars he gains to funnel into future recovery programs, the very support structures that saved his own life two decades prior.

In 2009, Diboun and his wife moved to Portland, where he pursued a career in coaching. One of the first things Diboun did upon arrival was to connect with the recovery community, which led him to The Alano Club of Portland, the largest recovery support center in the United States.

Diboun’s personal history of substance addiction is circuitous and complicated—documented extensively in Trail Runner, The New York Times, Ginger Runner interviews, and others—but what’s most important to know is that it led him down a path that wasn’t his own. Alcoholics Anonymous (A.A.) and the 12-step program threw him a lifeline and he white-knuckled it to shore, reinforced by commitments to a plant-based diet and a healthy dose of body movement. (That’s code for running a ton of miles.)

Such discipline brought him to the highest levels of ultrarunning. He’s a four-time finisher of the Western States 100 Mile Endurance Run (once in the top 10), a three-time finisher of the H.U.R.T. 100, in Hawaii, and he represented the U.S. at the IAU Trail World Championships in 2015. These accolades sit beside countless ultra wins and podiums.

His success story prompted Brent Canode, executive director of the Alano Club or Portland, to reach out to Diboun in 2018 with a proposition. Diboun had, by then, teamed up with mountain athlete Willie McBride, to start Wy’East Wolfpack in 2012. The business offers group functional fitness programs, youth programs, and personal guidance to get people outdoors and on trails.

Under Canode’s leadership, the Alano Club just launched The Recovery Gym (TRG)—a CrossFit-style facility offering courses for those in recovery, and Canode saw running as a natural extension of this program. He asked Diboun to spearhead a new running portion of the gym. For Canode, though models like the 12-step program were widely available and proven effective, he found the diversity of options for community lacking beyond that.

“What we learned was that a lot of folks don’t attend 12-step programs,” Canode says. “They haven’t found a connection anywhere else, and that’s a matter of life or death for a person in recovery.”

Together, the two started regular informal runs called the Recovery Trail Running Series, which evolved into a more formalized wing of the gym: Run TRG. This program quickly took off, offering evening group runs, outings that would often end in post-run dinners and fun gatherings. The groups grew bigger each week.

“We cultivated this community for anybody in or seeking recovery from substance addiction, and it really picked up some good momentum,” Diboun says.

When the pandemic shut everything down in March 2020, including The Recovery Gym and its new Run program, regulars instantly lost the group’s connection. Many relapsed and started using substances again. A few turned to suicide, including a prospective coaching client for Diboun who had met with him just one week prior.

“I know from personal experience that life can get too overwhelming at times and you get too stressed or overwhelmed and you can’t see anything,” Diboun says. “You can’t see any hope, so you just live recklessly, helplessly. In extreme cases, life can feel not worth living anymore.”

While running one evening by headlamp, Diboun thought about the fragility of hope, the pandemic, the recent suicides, and the ever-increasing need for community. The combination of isolation and mental health decline, paired with an uptick in running popularity during the pandemic (Run TRG, once relaunched, tripled in size), created an opportunity for Diboun to leverage his visibility as both a decorated ultrarunner and someone vocal about his addiction history.

An idea was born: Move Through Darkness.

For one night, sundown to sunrise, he would organize a run to crisscross the city, connecting various trail systems and raising visibility of the mental health challenges entangled with isolation and addiction. It would take place around the winter solstice, the longest night of the year.

The initiative would serve three main purposes: First, it would be a personal pilgrimage for Diboun, a reminder of his own ongoing relationship with sobriety. Second, it would offer another way for those in recovery to come closer during difficult times. And third, the event would raise financial support for the Alano Club of Portland, which serves more than 10,000 people in recovery each year through mutual support groups like A.A., peer mentoring services, art programs, harm reduction services, and fitness-based initiatives like The Recovery Gym and Peak Recovery, Alano’s newest program, which provides free courses in split boarding, rock climbing, and mountaineering. Over the last eight years Alano has won four national awards for innovation in the behavioral health field.

December 2020 was the first-ever Move Through Darkness event. About 30 runners participated throughout the night, joining Diboun in various sections of his sinuous route. Given that the invitation was to run upwards of 100K through the night in some of the worst weather of the year, the turnout was impressive. The group eventually made their way to Portland’s Duniway Track to complete a few hours of loops, encouraged onward by music.

One of those runners that first year was Mike Grant, 47, a licensed clinical social worker from Portland. Grant has been in long-term recovery with substance addiction and understands the initial hurdles of getting out there. During the event, Grant completed his first ultra-distance run by covering 50 miles. He hasn’t missed a Move Through Darkness run since.

This year, he’ll be joining again, in large because of Diboun.

“You hang out with Yassine for any length of time, and the next thing you know you’re running further than you ever have before,” Grant says. “He’s one of those people you just feel better when you’re around.”

The Move Through Darkness route is roughly the same every year, but it always starts and ends at the Alano Club, located in Portland’s Northwest neighborhood. This first year, his daughter, Farah, ran with him from Duniway to the Alano Club, which was a particularly special moment to share.

The fundraising component is a pledge-per-mile model, where you can pay a certain dollar amount for every mile Diboun will cover. All funds go to support the Alano Club, specifically the Recovery Toolkit Series. Other recovery-focused gyms are increasingly available nationwide, but The Recovery Gym is the only CrossFit affiliate in the U.S. designed from the ground up, exclusively for individuals in recovery.

Each week, TRG offers six to eight classes free of charge to anyone in recovery. Every coach holds credentials in both CrossFit instruction and peer mentoring for substance use and mental health disorders. An original inspiration for Run TRG was the Boston Bulldog Running Club, a nonprofit established in 2015 to provide running community reinforcement for those affected by addiction and substance addiction.

According to national statistics released earlier this year, 29 percent of U.S. adults have been diagnosed with depression at some point in their lives—the highest rate since such data was measured. Suicides in the U.S. reached all-time highs in 2022, at nearly 50,000 lives—about 135 people per day lost to self-inflicted death. In 2022, 20.4 million people in the U.S. were diagnosed with substance abuse disorder (SUD).

Oregon, specifically, is rated number one in the country for illicit drug use. In 2020, Oregon had the second-highest alcohol and drug addiction rates in the country, while ranking last in treatment options.

Canode says that, after 40 years of researching addiction and effective recovery, the single most important aspect of recovery success is authentic connection to a like-minded community. That’s why both Canode and Diboun are building an all-hands-on-deck approach to recovery through running, to strengthen connections through movement.

“In recovery, we know how to grind,” he says. “We are naturally great endurance athletes. We also know how to consistently move through darkness, which is especially true in the beginning of someone’s recovery journey. It’s often not rainbows and unicorns and lots of positivity. It’s a grind. It’s grueling.”

Annalou Vincent, 42, a senior production manager at Nike, is one of the many people who have reached out to Diboun from all over the Portland community.

“Finding Yassine and Run TRG saved my life,” she says. After starting a running practice in her thirties, she started feeling better and decided to question decisions like drinking alcohol. She eventually dropped booze and became a regular at the Run TRG. Vincent has worked closely with Yassine to develop and promote Run TRG, and has joined Diboun for various legs of Move Through Darkness over the years.

“I can’t imagine my life or my sobriety without running and this program, says Vincent. “Over the years I’ve seen it change the lives of many others. Move Through Darkness is an extension of that. This program and others like it are saving lives.”

Willie McBride, Diboun’s business partner, supports Move Through Darkness each year and has witnessed its evolution and impact.

“I think people really connect with this project because they understand those dark parts of life, and how challenging they can be. Darkness comes in all different forms,” he says. “But also the very tangible act of running all night, literally putting their body out there—coming together as a group sheds light right into that darkness.”

Diboun is reminded daily of his life’s work, to remain sober and offer his endurance as a gift to others, even when it gets difficult.

“I’m coming up on 20 years sober, but I’m not cured of this,” he says. “This is something I need to keep doing and stay on the frontlines.”

With record rainfall aiming for Oregon in December, this Saturday night calls for a 58 percent chance of rain showers, with the last light at 5 P.M. and the first light around 7 A.M. That’s potentially 14 soggy hours of night running. But this forecast doesn’t cause Diboun any concern. He’s used to it, used to running for hours in the dark, used to being drenched. He’s faced that long tunnel and knows that there’s always light at the end, as long as you keep trudging forward, and best when together.

“You keep passing it on,” he says. “You keep giving it away, in order to keep it. Gratitude is a verb.”

by Outside Online

Login to leave a comment