Running News Daily

Top Ten Stories of the Week

7/20/2024

These are the top ten stories based on views over the last week.

Ludovic Pommeret Wins Hardrock 100 in Course-Record Time Courtney Dauwalter is on course-record pace, trying to win the race for a third consecutive year

This is an ongoing story that will continue to be updated as more runners reach the finish line in Silverton, Colorado.]

Maybe you forgot that Ludovic Pommeret was the 2016 Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc champion. Or that he was the fifth-place finisher in Chamonix, France, just last year. Or maybe you thought the 49-year-old Frenchman was past his prime. Either way, he reminded us all he’s at the top of not only his game, but the game at the 2024 Hardrock 100.

The Hoka-sponsored runner from Prevessin, France, took the lead less than a third of the way into the rugged 100.5-mile clockwise-edition of the course after separating from countryman François D’Haene, the 2021 Hardrock champion and 2022 runner-up, and never looked back. Pommeret progressively chipped away at the course record splits—a course record, mind you, set by none other than Kilian Jornet in 2022—to win this year’s event in 21:33:12, the fastest time in the race’s 33-year history. Jornet set the previous overall course record of 21:36:24, also in this clockwise direction in 2022.

(Pommeret kissed the rock in to complete the course in 21:33:07 at 4:33 A.M. local time, but race officials credited him with the slightly slower official time.)

“It was my dream (to win it),” Pommert told a small collection of fans and media after winning the race at 3:33 A.M. local time. “I was just asking ‘when will there be a nightmare?’ But finally, there was no nightmare. Thanks to my crew. They were amazing. And thanks to all of you. This race is, uh, no word, just so cool and wild and tough.”

On Friday, July 12, 146 lucky runners embarked on the 2024 Hardrock 100. Run in the clockwise direction this year, it was the “easy” way for the course with a staggering 33,000 feet of climbing and an average elevation over 11,000 feet thanks to the steep climbs and more tempered, runnable descents.

Combined with relatively cooperative weather (hot during the day on Friday, but no storms) and a star-studded front of the pack headlined by Courtney Dauwalter and D’Haene, the tight-knit Hardrock 100 community was on course record watch.

And the event delivered—along with a whole lot more.

On the men’s side, the front of the race took a blow before the gun even went off when Zach Miller, last year’s Ultra-Trail du Mont Blanc runner-up, was denied entry after undergoing an emergency appendectomy the weekend before.

Despite the heartbreak of being forced to wait another year to participate in this hallowed event, Miller was very much a presence in the race, most notably for slinging fastnachts (Amish donuts) from his van in Ouray for race supporters and fans.

Such is the spirit of this event, deemed equally as much a run as a race.

The men’s race was further upended when D’Haene, in tears surrounded by his wife, three children, and friends, dropped from the race at the remote Animas Forks aid station (mile 58). An illness from two weeks before proved insurmountable for the challenge ahead. That blew the door wide open for the hard-charging leaders ahead.

Pommeret had built a 45-minute lead over Jason Schlarb, an American runner who lives locally in Durango, and Swiss runner Diego Pazosby, the time he had left the 43.9-mile Ouray aid station amid 85-degree temperatures. His split climbing up and over 12,800-foot Engineer Pass (mile 51.8) extended his lead to more than an hour over Schlarb and nearly 90-minutes at the Animas Forks aid station.

“I thought it was great. To run off the front like he did, and then just hold that all day and get the overall course record is pretty awesome,” Miller said. “When Killian did it, two years ago, it was a, it was a track race between him, Dakota, and François, after they got some separation from Dakota, it was Kilian and and François, all the way to Cunningham Gulch (the mile 91 aid station) and then Kilian just torched it on the way in. So yeah, it was super, super impressive for Ludo to do that. That’s a very impressive effort.”

The sleepy historic mining town of Silverton, Colorado was unusually hectic at 6 A.M. on Friday. In the blue hour before the sun poked over the San Juan Mountains looming above, 146 runners toed the start line of the Hardrock 100, marked by flags from the countries represented by competitors on either side of the dirt road.

With the sound of the gun, runners jogged off the start line—their caution a tacit sign of respect for the monumental challenge of what was to come. As the runners passed through town to the singletrack wending its way up to Miner’s Shrine, group of men headlined by D’Haene, Ludovic Pommeret, Diego Pazos, and Jason Schlarb quickly took command of the front, the bright yellow t-shirt of Courtney Dauwalter was easy to spot just behind, along with Katharina Hartmuth and Camille Bruyas.

If they weren’t awake already, runners certainly were after crossing the ice-cold Mineral Creek two miles into their journey before starting the grunt up to Putnam Basin. At the top of a sunny, grassy Putnam Ridge (mile 7) 1:34 into the race, the lead pack of men remained, while Dauwalter had made a statement solo just three minutes back from the men and four minutes up on Hartmuth.

Dauwalter was smiling and chatty when she reached the KT aid station at mile 11.5, in 2:24 elapsed. By Chapman (mile 18.4), four hours in and 10 minutes under her own course record pace, she was pouring water on her head under the blazing sun. Things were heating up—in more ways than one.

When Pommeret galloped into Telluride (mile 27.7) after 5:37 of elapsed time in the lead, he was right on Jornet’s course record pace. One minute, some fluids and restocking later, and he was gone.

But wait, it was still a close race! D’Haene charged into Telluride just two minutes later and hardly stopped before continuing on through downtown before busting out the poles and starting the steep, steep 5,000-foot climb up Virginius Pass to the iconic Kroger’s Canteen aid station nestled into a notch of rock at the top at 13,000 feet.

Not to be outdone, the women’s race proved equally thrilling coming into Telluride. Bruyas bridged the gap up to Dauwalter, and the two ran into town together in 6:25 elapsed. Both took three minutes in the aid station, although that must have been enough social time for Dauwalter, as she pulled ahead marching up the climb, poles out and head down. A bouncy Bruyas alternated between hiking and jogging just behind.

But time again again, Dauwalter’s long, powerful stride simply proved unparalleled. By Kroger’s (mile 32.7) Dauwalter had reestablished her lead by five minutes over Bruyas and 17 ahead of Hartmuth in third. She’d built that gap to 10 minutes in Ouray at mile 43.9, but she left that aid station in less than two minutes with a stern, serious look on her face. But as she crested Engineer Pass at the golden hour, wildflowers blanketing the vibrant green hillsides basking in the setting sun, she enjoyed a 30-minute lead in the women’s race and was knocking at the door of the men’s podium.

While Dauwalter forged ahead with her unforgiving campaign for a third straight win, the men’s race started to rumble. Like Dauwalter, Pommeret continued to blaze the lead looking strong as he trotted down Engineer to the Animas Forks aid station at mile 57.9 in 11:39 elapsed. He hardly stopped before continuing on to Handies Peak, which at 14,058 feet marks the high point of the race. He had blown the race wide open.

An hour and 15 minutes later, Schlarb, looking a bit more beleaguered, ran into Animas Forks with his pacer, where he sat down and changed his shirt while receiving a pep talk from his partner and son. But he made quick work of the time off feet nonetheless, and three minutes later he was back at it, seven minutes before Pazos appeared.

While D’Haene arrived just 10 minutes later, he did so in tears, holding the hand of his youngest son. After a considerable amount of time sitting in the aid station, surrounded by his family and crew, he called it quits. The lingering effects of an illness from just 10 days before proved too much to overcome as the hardest miles of the race loomed ahead.

While D’Haene pondered his fate, Dauwalter blitzed into Animas Forks in 13:26 with that same look of determination, 16 minutes ahead of course-record pace. She briefly stopped to prepare for the impending night, picking up her good friend and pacer Mike Ambrose to leave the aid station in fourth overall. Bruyas maintained her second place position 30 minutes back, with Hartmuth in third about 20 minutes behind her.

Pommeret continued charging ahead solo, increasing over Schlarb and Pazzos by more than two hours late in the race. When Pommeret passed through the 80.8-mile Pole Creek aid station at 10:44 P.M., it shocked the small group of race officials, media and fans watching the online tracker from the race headquarters in Silverton. Based on that split, it was originally calculated that Pommert could arrive as early as 2:34 A.M.—which would have been a finishing time of 20:34—but he didn’t run the final 20 miles quite as fast as Jornet did in 2022.

Behind him Pazos caught Schlarb to take over second place before Pole Creek and increased the gap to four minutes by the Cunningham aid station (mile 91.2).

Pommeret, who develops training software for air traffic controls in Geneva, Switzerland, didn’t break into ultra-trail running until 2009 when he was 34 years old. He was third in UTMB that year—behind a 20-year-old Jornet, who won for the second straight year—the first of seven top-five finishes in the marquee race in Chamonix. (He was third in 2017 and 2019 and fourth in 2021 and 2023.) He also won the 90-mile TDS race during UTMB week in 2022, and the 170-kilometer Diagonale des Fous race (Grand Raid La Reunion) on Réunion Island in the Indian Ocean in 2021 and placed sixth in his first attempt at the Western States 100 in California in 2022.

Last year, Pommeret placed 13th overall in the Western States 100 and nine weeks later finished fifth at UTMB behind Jim Walmsley, Miller, Germain Grangier, and Mathieu Blanchard.

“We know Ludo is a beast, but to be a beast for so long, for so long is so impressive,” Miller said. “He’s 49, which by all means is a capable age in this endurance world. But I think anytime someone 49 does something like that, it’s gonna turn some heads because that would’ve been a really good performance for anyone. To have the track record he’s had—winning Diagonale des Fous, UTMB and Hardrock, that’s pretty impressive.”

Courtney’s Final

By the time Dauwalter was pushing her way up Handies Peak, she had a smile on her face and engaged in playful conversation with media and spectators on the course. She had good reason to smile: she was feeling good and she had increased her 10-minute lead at Ouray to more than 60 minutes. Dauwalter went through the Burrows aid station (mile 67.9) in less than a minute, while Bruyas came in an hour later and spent four minutes refueling before heading out again.

Three hours after Pommeret had passed through the Pole Creek aid station (mile 80.8), Dauwalter arrived at 1:54 A.M., still in fourth place overall about 50 minutes behind Pazos and Schlarb. She took a little more time there, but was back on her feet in four minutes and running strong again and still on record pace. Bruyas walked in to Pole Creek at 3:08 A.M. in sixth overall, but the gap behind Dauwalter continued to widen.

Dauwalter was in and out of the Maggie aid station (mile 85.1) in two minutes and blazed through the Cunningham aid station (mile 91.2) even faster. The race seemed to be in hand at that point with Bruyas more than 90 minutes behind (in fact, someone updated Wikipedia and declared her the winner not long after Pommeret finished), it was just a matter of how fast she could finish.

(07/14/24) Views: 115Lucia Stafford demolishes 30-year-old Canadian record in 2,000m

At her very first Diamond League in Monaco on Friday, Canada’s Lucia Stafford obliterated the 30-year-old Canadian record over the 2,000m distance. Her time of 5:31.18 beat Angela Chalmers’ previous record of 5:34.49 by almost three seconds.

The 2,000m isn’t commonly run, so many of the elite athletes in the field jumped at the chance to set new records, including Australia’s Jessica Hull. The race was set up for Hull to challenge the world record of 5:21.56 set by Francine Niyonsaba of Burundi at the World Continental meet in Zagreb, Croatia in 2021. With the help of three different athletes who shared the job of pace-setting, Hull finished with a time 5:19.70–the fastest 2,000m in history–with exactly two seconds to spare.

In the same race, Cory Ann McGee‘s time of 5:28.78 betters the former North American record of 5:32.70, which Stafford also snuck under.

This sixth-place finish at her very first Diamond League marks Stafford’s first outdoor national record. She already holds the North American indoor 1,000m record of 2:33.75.

Arop runs season’s best

After getting passed in the final 100m stretch of his race, Marco Arop, the reigning world champion in the men’s 800m, finished sixth with a time of 1:42.93–also bettering his season’s best.

Making his Diamond League debut, 19-year-old Christopher Morales-Williams also took sixth place in his 400m race. Although his time of 45.11 is not nearly his fastest of the season, he’ll have the chance to compete against these world-class athletes at the Olympic Games in Paris next month.

Two-time Olympic pole-vaulter Alysha Newman took fourth place in her event earlier in the day, jumping a season’s best of 4.76m. She jumped her previous season’s best of 4.75m to take the win at the Canadian Olympic Trials in Montreal earlier this month.

(07/13/24) Views: 103Cameron Ormond

Vivian Chebet's story of luck from finishing fifth at Olympic trials to receiving late call up to women's 800m team

Vivian Chebet had already lost hope of making the Olympic team after finishing fifth at the Kenyan Olympic trials but luck knocked on her door and she will be flying Kenya's flag high in the women's 800m following new developments.

Vivian Chebet, the latest addition in the women’s 800m team to the Paris 2024 Olympics had already given up on her dream of making it to the global stage this season.

At the Kenyan Olympic trials, Chebet finished fifth and she knew there was no chance for her to compete at the Olympic Games in Paris, France.

However, Mary Moraa’s sister cousin, Sarah Moraa, who finished third, failed to attain the qualifying time before the deadline and was forced to pull out of the Games.

That is when Chebet, who never thought luck would visit her, received a call inquiring whether she would want to join Moraa and Lilian Odira to the Olympic Games.

She noted that the news came as a surprise to her, however, she had prepared well and was ready for the huge task that awaited her.

“It was surprise somehow because I was well-prepared to join the team and when we held the trials and I was number five, I knew that I had missed the golden opportunity,” she told the media on Thursday, July 11.

“After sometime, I was called and asked if I could join Odira and Mary and that’s when I was surprised because I had already surrendered,” she added.

Chebet had qualified for the Olympics via world rankings and this season, she had claimed a bronze medal in the women’s 800m at the African Games.

She added that training alongside Moraa, the reigning world champion, is a morale booster since she is able to learn a lot from her.

“Being with Moraa is a morale booster because at least we are able to rectify each other’s mistakes because no one is perfect. If I don’t run well, she comes and tells me and I also try and be of help to her. Training as a team is something very helpful,” she added.

(07/12/24) Views: 100Abigael Wafula

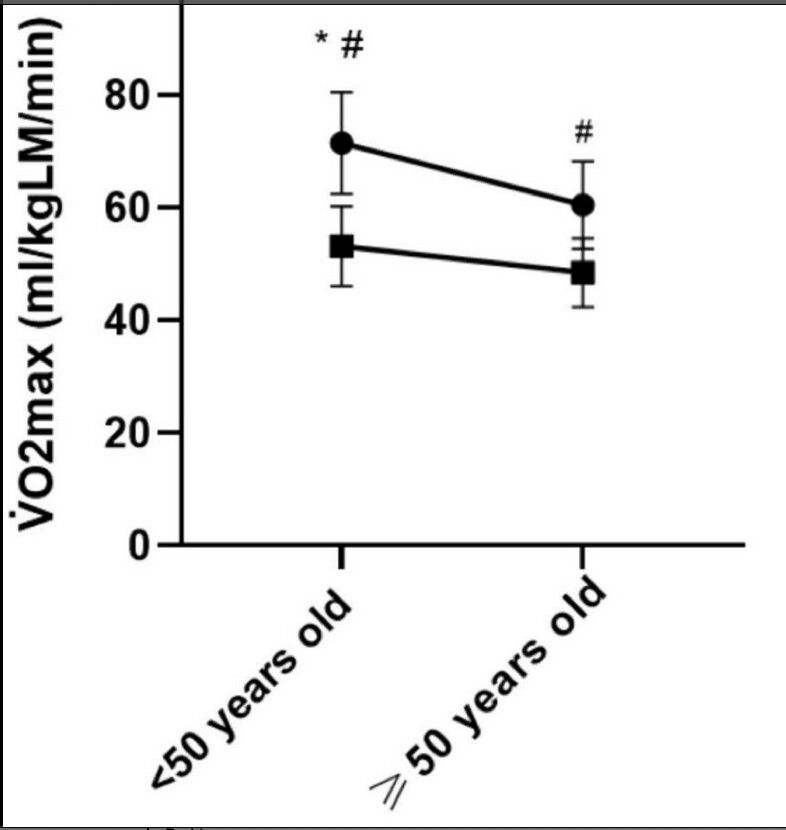

New Study Reveals How Women's VO2 Max Differs from Men's

A new study from researchers at the Federal University of São Paulo in Brazil focused on women's aerobic capacity suggests that the mechanisms of VO2 max decline—and thus perhaps the best countermeasures—are different in men and women.Maximal oxygen uptake, or VO2 max, is perhaps the single best predictor of long-term health and longevity. It’s also the key trait that distinguishes elite endurance athletes. We know all this from more than a century of research… in men. Whether the same things hold true for VO2 max in women is less clear, because there simply isn’t as much data on them.

A new study from researchers at the Federal University of São Paulo in Brazil aims to fill some of this gap. They recruited 85 runners and 62 sedentary people, all women between the ages of 20 and 70, and split them further into younger (less than 50) and older (greater than 50) age groups. Then they tested their VO2 max with a progressive treadmill test to exhaustion, measured their body composition with a DXA scan, and collected information about their training and other health-related habits. The results are published (and free to read) in Experimental Gerontology.

The headline findings are unsurprising: runners had higher VO2 max than non-runners, meaning they were able to suck in, distribute to their muscles, and use more oxygen per minute; younger people had higher VO2 max than older people. But when you zoom in on the details, some more interesting patterns emerge.What the VO2 Max Data Shows

There are three ways of expressing VO2 max. The first is absolute VO2 max, which is simply the greatest volume of oxygen you can use per minute, usually expressed in liters per minute. If you get fitter, you’ll be able to deliver and use oxygen more quickly, enabling you to power your exercise on sustainable aerobic metabolism for longer. Conversely, if you get too unfit and your VO2 max drops too low, even simple daily activities like climbing the stairs will require more oxygen than you can supply, turning them into challenging anaerobic efforts.

Here’s how the absoluteVO2 max values compared for the four groups, with runners represented by circles and sedentary people by squares:All this means that absolute VO2 max is a useful marker of health and performance—but it’s less useful for comparison between different people, because the amount of oxygen you use depends on body size. A heavyweight rower might use twice as much oxygen as a diminutive marathoner, but if she’s twice as big then she’s not necessarily fitter. Instead, she’ll need all that extra oxygen to move her larger body around. A better comparison would be to divide each person’s VO2 max by their weight, giving what’s called relative VO2 max, expressed in milliliters of oxygen per kilogram of body weight. Here’s what that data looks like:The key thing to notice here is that there’s a much bigger gap between the runners and non-runners in relative VO2 max than in absolute VO2 max, which is because the non-runners weigh substantially more on average. The relative value offers a much better reflection of how much fitter the runners are for running: what matters is not just how much aerobic power you can deliver, but how big a load that power needs to move.

Why Body Composition Matters, Too

The researchers also present a less-common third way of expressing VO2 max. In this case, they divided the absolute value not by total weight, but by the weight of each person’s lean mass, meaning primarily muscle as well as connective tissue.

To understand why this is relevant, it’s useful to think about VO2 max in terms of oxygen supply and demand. The traditional view of VO2 max was that it was dictated by oxygen supply—that is, by how quickly you could suck in oxygen, diffuse it from your lungs to bloodstream, and pump it to your muscles. These are all considered “central” limitations on VO2 max. The primary way changing VO2 max, in this picture, is for your heart to get stronger so that it can pump more blood to your muscles.

But oxygen demand also matters. It doesn’t matter how much oxygen you pump to your muscles if your muscles aren’t capable of extracting and, with the help of mitochondria, making use of it to provide aerobic energy. That’s why VO2 max is more closely proportional to your total muscle mass than to your overall weight. If you add ten pounds of fat to your body, your absolute VO2 max won’t change because fat doesn’t consume oxygen. If you add ten pounds of muscle, your ability to consume oxygen will increase, and your ability to supply oxygen will likely follow suit. How much muscle you have, and how effectively that muscle can use oxygen, are “peripheral” limitations on VO2 max.

Here’s what the data showed for VO2 max divided by lean mass only:An Unexpected Finding About VO2 Max in Women

Here’s where the surprise comes in. Based on earlier data from men, the researchers had hypothesized that these relative-to-muscle values would be less affected by aging than the relative-to-whole-body values. To put it another way, the male data had suggested that age-related declines in VO2max were primarily related to declines in central factors like the heart and circulatory system, while peripheral factors like the ability of muscle to use oxygen stayed relatively constant. But that’s not what they found here: both central and peripheral factors seemed to decline at similar rates in women.

Why should VO2-max declines in women be different than in men? One possibility is that it’s a fluke that’s specific to the relatively small group of women being tested here. But it’s also possible that there’s a genuine difference. The researchers suggest that “intramuscular adipose tissue”—that is, small amounts of fat located within the muscle itself, sometimes referred to as muscle fat infiltration—may play a role. This infiltration tends to be higher in women, and increases with age. If that’s what’s happening, then it suggests that the mechanisms of VO2 max decline—and thus perhaps the best countermeasures—are different in men and women.

There’s one final point to note in this data—one that, in this case, does echo previous findings in men. The runners experienced a steeper VO2 max decline with age than the non-runners. This might be a sort of physiological regression to the mean: the higher you start, the more you’re likely to fall. But it probably also reflects the fact that older runners tend to train less than younger ones, a pattern that showed up in this study too. There are plenty of good reasons for that, but it’s also a reminder: if you’re working hard to be super-fit now, you’ll have to keep working similarly hard to be similarly fit in the future. When it comes to fitness, saving for retirement only takes you so far.

(07/13/24) Views: 99Outside Online

'That is the only record I regret' - Asafa Powell on the 100m race he set a World Record in accidentally

Powell set a then100m World Record of 9.74 in 2007 despite intentionally slowing down towards the end of the race.

Jamaican sprint legend Asafa Powell, renowned for his blistering speed and dominance in the 100 meters, has recently opened up about a race he believes could have resulted in an even faster time if he had given it his all.

The race in question is the 2007 Rieti meeting in Italy, where Powell set a then-world record of 9.74 seconds. Despite his remarkable achievement, Powell reflects on what might have been had he not intentionally slowed down towards the end.

In a recent guest appearance on Justin Gatlin's Ready Set Go podcast, Powell shared his thoughts on the race and the strategy that led to his impressive but bittersweet performance.

The Rieti race took place shortly after the Osaka World Championships in 2007, and to this day, Powell holds the record for the most sub-10 second 100m races in history.

He previously held the world record in the event until fellow Jamaican Usain Bolt shattered it in 2008 with a 9.68-second run at the Beijing Olympics, followed by an astounding 9.58 performance in 2009 in Berlin, Germany.

Reflecting on his performance in Rieti, Powell explained his strategy and the circumstances that led to his record-setting but somewhat unfulfilled run.

"That is the only record I regret," Powell admitted. "This was after the world championships in Japan. We went to Rieti and in the warm-up, the coach was like, ‘make sure you get the 30 meters first.’"

Powell elaborated on the instructions from his coach, which focused on perfecting his drive phase and transition.

"When he makes a command, I am like, ‘I am going to do it,’ so the coach was like, ‘we are working on your drive phase and transition. When you get to 70 meters, just back off the gas,’" he recalled.

True to his coach's directive, Powell executed the plan flawlessly.

"I went out there and did just that, and when I crossed the finish line, I saw 9.74 and I was waiting for the clock to change or something. 9.74? I see everyone celebrating and I am like, I cannot even celebrate. This is just the heat. Am I going to go for the victory lap? I am just getting ready for the final. What am I going to do?" Powell recounted.

"I didn't even know what to do at that time. I see everyone celebrating. My manager was the first to get to the track and I am like, celebration? I need to get back to the warm-up. It was unexpected. I did not feel like I was running a world record at the time. I did not know what to do, but I think I ran that race flawlessly," he said.

Powell's reflection on the race leaves fans and athletes alike wondering what could have been. "I can’t even think about what I would have ran if I had kept on just going to the finish line. I would have ran 9.6 easily," he concluded.

Asafa Powell's legacy in the world of sprinting is undeniable, and his reflections on the Rieti race offer a glimpse into the mind of a true champion who continually strives for perfection.

Despite the "what ifs" that linger, Powell's accomplishments remain a testament to his remarkable talent and dedication to the sport.

(07/12/24) Views: 96Mark Kinyanjui

Could water sprinting be the next Olympic sport?

The 2024 Paris Olympics are fast approaching, and the world’s best athletes will compete for gold on the track, road and field. Is there the potential for a new Olympic sport that defies traditional athletic norms? Enter water sprinting—a phenomenon demonstrated by basilisk lizards and a bird called the Western grebe. Scientists are exploring the idea of whether humans could also manage this remarkable feat, as reported by physicsworld.com.

How do animals do it?

The basilisk lizard, often called the “Jesus Christ lizard” for its ability to sprint across water, can escape predators by briefly running on the water’s surface. Dr. Tonia Hsieh, a biologist at Harvard University, studied the way lizards defy gravity. Hsieh discovered that when the lizards run, their large feet slap the water, creating a force that propels them forward and upward. Hsieh’s research showed that while these lizards can run on water due to their speed and foot size, balancing on this ever-changing surface is still a significant challenge.

Humans and water running

The idea of humans mastering the ability to speed across watery surfaces is appealing, but challenging. Harvard researchers Tom McMahon and Jim Glasheen developed a mathematical model suggesting that to run on water, a human would need to slap the water with a force nearly 15 times greater than the maximum power we can exert. The basilisk is also running on a yielding surface, unlike humans on a track or road.

Humans and water running

The idea of humans mastering the ability to speed across watery surfaces is appealing, but challenging. Harvard researchers Tom McMahon and Jim Glasheen developed a mathematical model suggesting that to run on water, a human would need to slap the water with a force nearly 15 times greater than the maximum power we can exert. The basilisk is also running on a yielding surface, unlike humans on a track or road.

Sha’Carri Richardson could sprint in space

Titan, Saturn’s moon, offers a potential venue for water running. With only 13.8 per cent of Earth’s gravity and lakes of liquid ethane, could athletes like Richardson, the current women’s 100m champion, run on Titan’s surface? Richardson’s sprinting abilities just might make it possible to run across Titan’s ethane lakes, though she would have to deal with extremely cold temperatures.

While water running remains a phenomenon we marvel at in nature rather than a viable Olympic sport (at least for now), it sparks the imagination about what might be possible in different environments. If space exploration continues to advance, we might one day see Olympians racing across the waters of distant planets.

(07/13/24) Views: 93Western States 100: Walmsley Wins a Fourth Time While Schide Rocks the Women’s Field

For hours, Katie Schide (pre-race and post-race interviews) chased ghosts. For hours, Jim Walmsley (pre-race and post-race interviews) and Rod Farvard (post-race interview) chased each other. And in the end, after 100 courageous, gutsy miles at one of the world’s most iconic ultramarathons, it was Schide and Walmsley who won a fast, dramatic 2024 Western States 100.

Schide, an American who lives in France, was on pace to break the course record until late in the race, while Americans Walmsley and Farvard battled throughout most of the second half of the race, alternating the lead as late as mile 85.

Schide’s winning time was 15:46:57, just over 17 minutes behind Courtney Dauwalter’s 2023 course record, almost an hour faster than her own time last year, and the second fastest women’s time ever. Walmsley, meanwhile, won his fourth Western States in 14:13:45, the second fastest time ever — only behind his own record of 14:09:28 that he set in 2019.

Second and third in the men’s race came down to an epic sprint finish on the track between Farvard and Hayden Hawks (pre-race and post-race interviews), who finished in 14:24:15 and 14:24:31, respectively.

In the women’s race for the podium, Fu-Zhao Xiang (pre-race and post-race interviews) finished second in 16:20:03, and Eszter Csillag (pre-race and post-race interviews) took third for the second time in a row, in 16:42:17.

Both races featured one of the deepest and most competitive fields in race history, with the men’s top five all coming in faster than last year’s winning time, and the women’s top 10 finishing just under 40 minutes faster than last year’s incredibly competitive top 10.

At 5 a.m. on Saturday, June 29, they were all among the 375 runners who began the historic route from Olympic Valley to Auburn, California, traversing 100.2 miles of trail with 18,000 feet of elevation gain and 22,000 feet of loss. After last year’s cool temperatures, the weather at this year’s race was a bit warmer, albeit with a notable lack of snow in the high country. The high temperature in Auburn was in the low 90s Fahrenheit.

A special thanks to HOKA for making our coverage of the Western States 100 possible!

2024 Western States 100 Men’s Race

In his return to the race that propelled him to the heights of global trail running and his first ultra on American soil in three years, Jim Walmsley (pre-race interview) demonstrated why he is, once again, the king of Western States. Before the race, Walmsley exuded a calmness that perhaps eluded him during his first attempts, when he attacked it with an obsessive intensity that led him to famously take a wrong turn and then dropping out in back-to-back years.

“We’ll just roll with what plays out and just kind of see what happens in the race,” he said in his pre-race interview. There’s a marked difference when compared to his remarks from his interview before the 2016 race.

What happened in the race was this: In his fourth Western States, Rod Farvard (post-race interview) had the race of his life to push Walmsley like he’d never been pushed before in his long history with the event.

Farvard — a 28-year-old from Mammoth Lakes, California, who has improved his finish each year at the race, from a DNF in 2021 to 41st place in 2022 to 11th place last year — put himself in a strong position from the start, leading a large pack of runners that included Walmsley at the top of the Escarpment, the 2,500-foot climb in the first four miles of the race. For the next 45-plus miles, Farvard remained in the top 10, part of a chase pack of American Hayden Hawks (pre-race and post-race interviews), Kiwi Dan Jones (pre-race interview), and Chinese runner Guo-Min Deng, among others.

At the Robinson Flat aid station at mile 30 — the symbolic end of the runners’ time in the high country, which features an average elevation of around 7,000 feet — Walmsley, who started the race conspicuously wearing all black, came through in 4:24 looking fast and smooth, now wearing an ice-soaked white shirt. Jones, the 2024 Tarawera 102k champion and fifth-place finisher in his Western States debut last year, and Hawks, who set the course record at February’s Black Canyons 100k after dropping out of last year’s Western States, followed about 90 seconds later. The two runners, frequent training partners, ran together frequently throughout the day, with Hawks often foregoing ice at aid stations.

After the trio of Walmsley, Hawks, and Jones went through Last Chance at mile 43 together, Walmsley put nearly two minutes on them up the climb to Devil’s Thumb. “I was with everybody at the bottom,” he said, according to the race’s official livestream.

About halfway through, at mile 49.5, the order remained the same: Walmsley in the lead with an elapsed time of 6:58, followed by Jones one minute back, Hawks two minutes back, and Farvard just over two and a half minutes back. The rest of the top 10 were last year’s 17th-place finisher Dakota Jones; 2024 Transvulcania Ultramarathon champion Jon Albon (pre-race interview), who is from the U.K. but lives in Norway; 2023 fourth-place finisher Jia-Sheng Shen (China) (pre-race interview); 2023 Canyons 100k champion Cole Watson; Western States specialist Tyler Green (pre-race interview); and Jupiter Carera (Mexico).

Then began a thrilling, chaotic second half of the race — featuring a gripping back-and-forth between Walmsley and Farvard, a wildfire near the course, a two-man river crossing, and a sprint finish on the track.

It all started when Walmsley entered Michigan Bluff at mile 55, again looking calm and in control, changing shirts and getting doused with ice. Farvard came in just behind him and left the aid station first, leading the race for the first time since the first climb up the Escarpment. The same routine took place seven miles later at Foresthill: Walmsley entering first, Farvard leaving first.

For the next 18 miles, the two runners alternated in the lead. By mile 78, they were so close that they were crossing the American River at the same time. Their battle underscored the overall depth of the field at this year’s race: At mile 80, the top five men were within 16 minutes of one another.

Around then, the 15-acre Creek Fire, which started not long before, was visible from the final quarter of the course and crews were temporarily not permitted to travel to the Green Gate aid station at mile 80 because the route to it passed close to the fire. Eventually, a reroute was established for crews to get to Green Gate and, later, after the wildfire was controlled, the regular route was reopened.

At Green Gate, Farvard came through in the lead, with Walmsley four minutes back and looking like he was hurting. It was then, perhaps, that the thought entered people’s minds: Could Farvard really take down the champ?

But Jim Walmsley is Jim Walmsley for a reason, and he again proved why he is among the world’s best. Against the ropes, facing one of his first real challenges in the race that shaped him, he delivered, entering the next aid station, Auburn Lake Trails at mile 85, more than a minute earlier than Farvard. He had made up five minutes in five miles.

Walmsley never trailed again, increasing his lead to 11 minutes by the Pointed Rocks aid station at mile 94 and then picking up his crew, including his wife, Jess Brazeau, at Robie Point to run the final mile with him. He entered the track at Placer High School to loud cheers, his loping stride still looking smooth, stopping a few steps short of the tape to wave to the crowd and raise his arms in triumph. He had done it again.

Behind him, Farvard was fading but determined to cap an extraordinary race with a second-place finish. Hawks, who had made up five minutes on Farvard in the couple miles between Pointed Rocks and Robie Point, was on the hunt, and by the time he stepped on the track, Farvard was within sight.

It was then that fans were treated to one of the most unique sights in all of ultrarunning: After 100 miles of racing, two men were sprinting against each other on a track. In the end, Farvard’s lead held, and he finished 16 seconds ahead of Hawks. He collapsed at the finish line — a fitting end to an epic performance.

Dan Jones ended a strong race with a fourth-place finish in 14:32:29, with Caleb Olson capping an impressive second half of the race — from 11th at mile 53 to fifth in 14:40:12 at the finish. All five men ran a time that would have won the race last year.

Behind Olson came Jon Albon, running 14:57:01 in his 100-mile running-race debut, followed by the surgical Tyler Green, who finished in seventh for his fourth straight top 10 finish at the race. Green’s time of 15:05:39 also marked a new men’s masters course record, breaking the 2013 Mike Morton record of 15:45:21.

Rounding out the top 10 were Jia-Sheng Shen in eighth with a time of 15:09:49, Jonathan Rea in ninth who methodically moved his way up during the last 60 miles to finish in 15:13:10; and Chris Myers in 10th in 15:18:25.

2024 Western States 100 Women’s Race

Through the high country, into and out of the canyons, and along the river of the world’s oldest 100-mile trail race, Katie Schide (pre-race and post-race interviews) raced only the ghosts of the clock and history. Smiling throughout, she seemed unaffected by the solitude and the enormity of the possibility that lay before her: to attempt to break the course record of one of the world’s most iconic trail races.

Schide, an American who lives in France, came into the race as the clear favorite, and for good reason: She finished second last year, breaking Ellie Greenwood’s previously untouchable 2012 course record by more than three minutes and losing to only Courtney Dauwalter, who broke Greenwood’s record by an astounding 78 minutes on her way to a historic Western States-Hardrock 100-UTMB triple win. Schide, winner of the 2022 UTMB and 2023 Diagonale des Fous 100 Mile, spent the last two-and-a-half months in Flagstaff, Arizona, training for Western States, winning this year’s Canyons 100k in an impressive tune-up and putting in a monster training block.

In her pre-race interview, Schide said that she had thought about ways to improve her race from last year, which perhaps should have been the first warning to her competition. The second, then, was her immediate separation from the women’s chase pack: She summited the Escarpment, a 2,500-foot climb during the first four miles, in first place and never looked back. By the first aid station — Lyon Ridge at 10 miles — she was already 12 minutes under course record pace, and by Robinson Flat at mile 30, she was 21 minutes ahead of second-place Emily Hawgood (pre-race interview), from Zimbabwe but living in the U.S.

The lead only ballooned from there. By Dusty Corners at mile 38, Schide was an incredible 26 minutes under course record pace, and though she lost a few minutes from that pace by the time she climbed up to Michigan Bluff at mile 55, her smile had not waned even slightly. She smoothly entered the iconic aid station, doused herself with ice, changed shirts, and was soon on her way. She never sat down.

Twenty-seven minutes behind her was Hawgood, looking to build on back-to-back fifth-place finishes. Eszter Csillag (pre-race and post-race interviews), a Hungarian who lives in Hong Kong, followed soon after, in the same third spot she finished in last year.

After them ran a dense pack of women: Only 16 minutes separated Hawgood in second from Lotti Brinks in 11th.

At the halfway point, the top 10 were Schide, 33 minutes up in an elapsed time of 7:26; Csillag; Hawgood; Chinese runner Fu-Zhao Xiang (pre-race and post-race interviews), the fourth-place finisher at last year’s UTMB; Lin Chen (China); American Heather Jackson, a versatile former triathlete who recently finished fifth at a competitive 200-mile gravel bike race; ultrarunning veteran Ida Nilsson (pre-race interview), a Swede living in Norway; Becca Windell, second in this year’s Black Canyon 100k; 2023 CCC winner Yngvild Kaspersen (Norway); and Rachel Drake, running her 100-mile debut.

Schide, easily identifiable in her pink shirt, maintained her large lead throughout the second half of the race, remaining calm, controlled, and upbeat throughout the tough canyon miles. By Foresthill at mile 62, she was 19 minutes ahead of course record pace and 48 minutes ahead of the second-place Xiang. Schide’s stride still looked smooth as she waved to fans and even high-fived a cameraman.

Schide’s aggressive pace eventually slowed — by Green Gate at mile 80, her lead on the course record had dissipated — but her spirits did not. After a quick sponge bath at Auburn Lake Trails aid station at mile 85, she fell behind course-record pace for the first time all day, only 15 miles remained until the finish.

Schide entered the track a couple of hours later, running with her crew and no headlamp. She would finish before dark. She stopped for a hug on the final straightaway and lifted the tape with, of course, a smile.

Xiang had methodically pulled away from Hawgood and Csillag during an incredibly strong second half to win the battle for second. Fu-Zhao Xiang finished in 16:20:03 for the third fastest time in race history. Chen, who dropped out at mile 78, was one of the few elite runners who had a DNF on this day, which was categorized by a lack of attrition in both the women’s and men’s elite races.

Eszter Csillag came in about 22 minutes behind Xiang in 16:42:17 for her second consecutive third-place finish, a 30-minute improvement from last year — a statistic that perhaps exemplifies the speed of this year’s race better than any other.

The battle for fourth and fifth was nearly as close as Farvard and Hawks’s race for second in the men’s race a couple of hours earlier.

At Pointed Rocks at mile 94, Hawgood led by barely two minutes, running hard and straight through the aid station. Kaspersen, meanwhile, was drinking Coke and made up almost a minute by Robie Point.

Emily Hawgood’s lead ultimately held, and she finished fourth in 16:48:43 to improve her finish from prior years by one spot. Yngvild Kaspersen was less than two minutes back in 16:50:39. Ida Nilsson capped a strong day to finish sixth in 16:56:52 and break Ragna Debats’s masters course record by almost 45 minutes. That means the top six women all finished in under 17 hours in a race that had only ever had three women finish under that mark — and two of them, Dauwalter and Schide, were last year.

The rest of the top 10 were Heather Jackson in seventh in 17:16:43, and, in close succession, Rachel Drake in 17:28:35, Priscilla Forgie (Canada) in 17:30:24, and Leah Yingling in 17:33:54.

The top 10 women were all faster than the 12th-fastest time in race history going into the day.

(07/12/24) Views: 90Robbie Harms

How to Keep Tick Bites from Ruining Your Summer

More people in the U.S. are being diagnosed with tick-related diseases every year, but we don't have to let that stop us from getting outdoors.

At home in Brooklyn, New York, my wife and I have discovered ticks on our dog, a pit-boxer mix who lacks the wherewithal to notify us of such an intruder. A few weeks ago, I found a tick—luckily, before it bit—on my arm while visiting Oakland, California. Outside editors have been coming across the disgusting creatures in northern New Mexico, northern Virginia, and coastal Massachusetts.

A decade ago, my little sister contracted Lyme disease in high school, so I have always been paranoid about tick bites. And with growing tick populations, ever more tick-related diseases, and a flurry of headlines about both, I’m sure I’m not alone.

There are hundreds of species of ticks, but the one to be most concerned about in the United States is Ixodes scapularis. The hard-body tick, also known as the blacklegged tick or deer tick, is a vector for a handful of diseases, including Lyme. “It causes far and away the most trouble in terms of health,” says Dr. Peter Krause, a senior research scientist with a specialty in epidemiology and infectious diseases at Yale Medicine.

Ticks are experiencing a largely unwanted glow-up in our current times. The largest vector-borne disease today is still Lyme, says Alison Hinckley, epidemiologist with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Division of Vector-Borne Diseases in Fort Collins, Colorado. She cites a 2021 estimate based on insurance records that shows 476,000 Americans are diagnosed and treated for Lyme disease each year, which can cause headaches, muscle aches, joint swelling, severe fatigue, and even neurological symptoms. (As a point of comparison, only about 2,000 cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever are reported each year in the U.S.) The reasons for the rise in Lyme range from deer populations to climate change. It’s enough to make me consider trading my hiking boots for gym trainers.

But if we stay inside, the bugs win. So we spoke to some experts to learn why ticks are prospering, what we can do about it, and how to continue to exercise outside safely. The good news? You can take precautions no matter your outdoor sport of choice, and finding a tick doesn’t have to be a five-alarm emergency.

According to the CDC, there are ticks in every state, though different species (carrying different diseases) proliferate in different environments. For instance, the lone star tick, named for a white spot on its back, is often found in Texas, and the brown dog tick thrives in Arizona. Lyme hails from Krause’s home state of Connecticut—it was named for the town of Old Lyme, in the state—but he might also encounter wood ticks and brown dog ticks, which can both transmit Rocky Mountain spotted fever. It’s not very common, he says, but the disease can cause fever, nausea, muscle pain, and a host of other scary symptoms. Despite its name, the lone star tick can also be found in Connecticut (it’s prevalent elsewhere on the East Coast, too, and in the southeastern and south-central United States), and can transmit an infection that leads to Alpha-gal Syndrome, which sometimes causes a permanent allergy to red meat. And that’s just one state. Another tick-borne disease, Babeosis, used to be called “Nantucket fever,” because one of the first cases in America was found on the nearby Massachusetts island in 1969. The Gulf Coast, American dog, and winter ticks transmit different pathogens around the country. You can see what ticks live in your state on the CDC website.

Still, the majority of tick-borne illnesses in the United States are Lyme disease. Ticks have a three-stage life cycle, Krause explains. As larvae, ticks feed on small mammals like mice. If these mammals are carrying Lyme-causing Borrelia bacteria, the tick is now infected and can transmit the disease. The “bloodmeal” (yum!) allows the larvae to molt into its next stage, when it is known as a nymph. At this point, if a nymph feeds on a human, the human will become infected.

Climate change is a major factor in the rise in tick diseases. Ticks need temperate, moist climates—they’ll die if it’s too hot, cold, or dry. Global warming, Krause says, is increasing tick habitat, with more areas becoming warm and humid. Given the southern states are experiencing hot, dry weather, they might have a temporary decrease in tick populations, but that hasn’t yet been shown, he says.

As a point of proof, Krause points to our northern neighbor. Canada was not historically home to Lyme-carrying tick populations, but now sees many cases of Lyme each year, due to both climate change and tick migration. Deer ticks, predictably, travel on the backs of deer and other furry creatures, but they can also attach to birds, Krause says, allowing them to establish a new colony hundreds of miles away.

The second factor that might be fueling today’s tickflation is deer distribution. Adult ticks use deer as all-you-can-eat mating hotels, and a single deer can host hundreds of ticks, Krause explains. “Wherever deer are, there are a lot more ticks than there would be without deer,” he says.

There is some agreement from across the pond. Dr. Lucy Gilbert is a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Glasgow with a focus on ecology, environmental change, and infectious disease ecology, along with evolution and diversity. Her research strongly suggests that the boom in deer distribution and abundance is a greater factor in the proliferation of ticks (though not necessarily Lyme disease) than climate change.

Lyme disease cases surged by 69 percent in 2022, according to the CDC. But even as data collections gets more efficient, there are still likely many cases missed. As STAT News reports, “There are a lot more cases of Lyme disease in the country than are ever reported to the CDC.”

The increase in disease incidence, Gilbert says, may be related to deer and climate change. Additional factors could be better awareness from the public and doctors identifying tick-related diseases, paired with an increase in outdoor recreation.

The simple answer is that activities that put you in tick habitat—long grass or forests with dense shrubs—will be higher risk than sports that don’t. Hiking and running in the woods increase the likelihood that you’ll encounter a tick. Even short grass, like you’d find on a baseball field or soccer pitch, can carry ticks, Krause says. Something on a hard court, like basketball, would be very low-risk.

The CDC recommends staying away from thick vegetation, high grass, and leaf litter and to “walk in the center of trails when hiking,” to avoid brushing up against grass or other plants where ticks might be hanging out.

Riding a bike on a trail might be lower-risk than running it, says Krause, because ticks will have greater difficulty reaching you from the grass, and cyclists are more likely to stay in the center of the trail. Walking may also be safer than trail running, as you’re more likely to avoid brushing any grasses in places with sharp turns, Krause says.

Dr. Kevin DuPrey, a sports medicine specialist, wrote a 2015 article about Lyme disease in athletes for Current Sports Medicine Reports, and he also has firsthand experience. When running cross-country at University of Delaware, Duprey contracted Lyme disease. Before he was diagnosed and treated, he’d experienced mid-race fatigue—to the point of wanting to lie down and nap during the middle of a competition.

Today, as a precaution, DuPrey tries to avoid overgrown trails especially from mid-May through August, when the transmission rate is highest for Lyme and other tick-borne diseases. He’ll check himself for ticks after running, or even mid-run if he’s in an overgrown area.

He recommended bug spray with DEET to repel ticks, but also offered a clothing tip: light-colored threads can make it easier to spot ticks on your body.

The CDC also recommends using EPA-registered insect repellents (like OFF! Active Insect Repellent I), wearing loose-fitting clothing, and treating your gear with permethrin, an insecticide that should not be applied directly to your skin. The organization even has chat bots to help you find effective repellents (they recommend something with DEET, picaridin, IR3535, oil of lemon eucalyptus, para-menthane-diol, or 2-undecanone) and assessing tick bites.

“In general, DEET, if used as prescribed, is safe,” Krause says. You wouldn’t want to apply it to a small child if they’re going to lick their skin, he says, but considers it safe overall when used as directed. If ingested, it can cause serious side-effects including seizures, according to the National Pesticide Information Center. But aside from a chance of skin irritation, it’s safe to apply topically. Permethrin, which is only suitable for application to gear and clothing, has more safety concerns, says Krause.

When you head back inside, Hinckley recommends you check your clothing and gear for ticks. Then, using a mirror, check your entire body, particularly under your arms, in and around ears, inside your belly button, the backs of your knees, your hair, between your legs, and around your waist. Then, take a shower as soon as possible.

Hinckley also encourages good tick hygiene for pets. Preventative products like topicals, chews, and collars can help, and she advises manual pet-downs for ticks after time outside. This isn’t just for your pets sake—ticks can take a pitstop on your four-legged roommate before making their way to you.

It’s understandable that you might freak out if you find a tick, especially if it’s attached. But if you find it early—within 36 to 48 hours—DuPrey say, the chance of Lyme disease transmission is actually very low.

If you’re uncertain how long it’s been since you were bitten, he advises seeking professional medical advice, especially if you were bit during the summer months, find a circular rash, or experience flu-like symptoms. If caught early, both Krause and Duprey says, Lyme and other tick-borne diseases can be treated with antibiotics.

As an expert who’s closely studied ticks and tick-borne diseases, Gilbert praises the media’s coverage in highlighting tick awareness and Lyme disease. But she says there is sometimes “too much scare-mongering and exaggerating the outcomes of Lyme disease.” While noting that some people progress to chronic Lyme disease, which can be debilitating, the vast majority of people who contract Lyme do not develop a long-term illness.

Gilbert has heard about certain tick-removal techniques like applying Vaseline, olive oil, or burning them off your skin, but her advice is simple: “This is not a good idea!” Instead, she recommends gently plucking the tick off of your skin by its mouth, using fine tweezers or tick tools (available at veterinary clinics, pharmacies, and online) which won’t squash the tick. If you do find a tick, take a picture before you dispose of it, so you can show it to a doctor in the event you need to visit one.

For disposal, the CDC recommends putting the bug in alcohol, a sealed bag, tape, or a soon-to-be-flushed toilet. The CDC also has resources that can help you decide what to do after a tick bite.

People with immunocompromising conditions are at greater risk for tick-borne infection, Krause says, and should exercise additional caution. As a historical example, he notes when Babesia (the parasite that causes Babesiosis) took over Nantucket, an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine advised people who didn’t have a spleen avoid buying land on Nantucket. (The spleen, which helps fight infection, is crucial in warding off Babesiosis.)

The best path forward might be to channel an anti-Robert Frost mentality. If you’re going to choose a path to hike, run, or a bike, choose a well-worn one, and stay in the center of it. And I’m not sure if Frost wrote a poem about this, but check your body, take a shower, and throw all your clothes in the dryer when you get back inside.

(07/14/24) Views: 87Outside Online

How a trip to Kenya motivated former optician Guillaume Pontier to nurture athletics talent in Iten

Frenchman Guillaume Pontier is passionate about nurturing talent in Iten and has opened up on the motivation he got when he visited the area for the first time alongside his father, who was a coach.

Frenchman Guillaume Pontier, a former optician, is making huge contributions in the Kenyan athletics scene to ensure the nurturing of talents continues.

Most Kenyan athletes come from humble backgrounds and affording training gear is always an uphill task but Pontier has made it easy for the athletes, providing them with affordable training gear in a store set up in Iten.

With the help of the Distance Athletics company, where Pontier is the co-founder, he was able to construct a tiny metal hut in 2022 with the outside of the structure reading, “For All Runners”.

There, they sell second-hand shoes from well-known brands with prices ranging from about Ksh 300 to Ksh 1500.

His motivation came from a trip to Kenya with his father, Jef, who was a coach of the France national marathon team some years back. Seeing athletes run barefoot with some wearing inappropriate gear, Pontier was motivated to help them. His father also spent much of his time in Iten where he trained French runners.

“It’s a community project, not a profit-driven enterprise. We saw many athletes on our trips running barefoot because they didn’t have trainers. It’s inaccessible. In Kenya they run 200km a week…They need shoes to do that,” Pontier told Financial Times.

To ensure the shoes are sold at fair prices, Pontier noted that he has by Ledisha, a local athlete, who works with her brother at the shop and they always decide the prices of the shoes.

The training gear sells fast and Pontier admitted that once they restock, news spreads like wildfire and dozens of athletes flock the store to purchase what is available. Due to that Pontier decided to partner with Distance’s European stores to help.

(07/15/24) Views: 87Abigael Wafula

Timothy Cheruiyot reveals main aspect in training he needs to address before Paris 2024 Olympics

Timothy Cheruiyot has disclosed what he needs to work on after his second-place finish behind Jakob Ingebrigtsen at the Diamond League Meeting in Monaco.

Olympic 1500m silver medallist Timothy Cheruiyot has disclosed the one thing he needs to work on before descending on the purple track at the Stade de France for the men’s 1500m at the Paris Olympic Games.

Cheruiyot has battled injuries in the past seasons but he has slowly been bouncing back and this season has been steady on him. He qualified for the Paris 2024 Olympics at the Kenyan Olympic trials, finishing third in 3:35.90.

The 28-year-old, after finishing second at the Diamond League Meeting in Monaco, noted that he has to work on his speed endurance if he has to silence his serial rival Jakob Ingebrigtsen.

The Norwegian clocked a stunning 3:26.73 to join the club of legends with a win as Cheruiyot was forced to finish second in 3:28.71. Africa 1500m champion Brian Komen sealed the podium in 3:28.80.

The 2019 world champion was happy to be peaking at the right time, expressing his elation towards the time posted, just less than a month before the Olympic Games.

“The race was good, I am happy about my time and my position. The 1500m nowadays is a very competitive race with a lot of young guys coming up fast," Cheruiyot said in a post-race interview.

“So I am proud because I am peaking myself towards the Olympics. I need to work harder to keep up. I know that I can come back strong. I especially need to work on my speed endurance.”

In the 1500m, Cheruiyot opened his season with a second-place finish at the Diamond League Meeting in Doha before finishing fourth at the National Championships, clocking 3:40.23 to cross the finish line.

Cheruiyot also finished second behind Ingebrigtsen at the Diamond League Meeting in Oslo before the Olympic trials where he finished third. As he heads to the Paris Olympic Games, Cheruiyot hopes to improve on his silver medal won at the delayed 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games.

(07/13/24) Views: 85Abigael Wafula