Running News Daily

Top Ten Stories of the Week

2/5/2022

These are the top ten stories based on views over the last week.

National record-holder Tonatiu Lopez, on track and making history for Mexico

For all its strength across the sporting spectrum, Mexico has had scant success of late on the track when it comes to major championships. At the Tokyo Olympics, the nation of 128 million fielded full teams across the marathons and race walks, but had just one male competitor on the track.

That athlete was Jesus Tonatiu Lopez, a 24-year-old whose Games came to an end in the semifinals of the 800m, a tactical mistake costing him precious fractions of a second and leaving him wondering what might have been. Lopez finished third, just 0.03 behind Emmanuel Korir of Kenya and 0.17 behind Patryk Dobek of Poland – who went on to win gold and bronze respectively.

“I cried,” says Lopez, who made his 2022 debut at the Millrose Games, a World Athletics Indoor Tour Gold meeting, on Saturday (29). “I felt very frustrated. I knew maybe I could be in that race.”

Over the coming months, he’ll have ample opportunity to make amends, with Lopez targeting the World Athletics Indoor Championships Belgrade 22 in March and the World Athletics Championships Eugene 22 in July.

“I’m not looking for a big achievement,” he says of Belgrade. “To compete with the best in the world is going to be helpful; I’ll get a lot of experience. In Eugene, I want to make the final. Obviously I want a medal, but I try to not stress myself with (such a) specific objective.”

On the build-up to Tokyo, the medal question was often put to him by Mexican journalists, and Lopez did his best to play down expectations.

“I don’t like to talk like that,” he says. “I just want to run the best I can. I’m going to do my best, but of course with my best race I can get a medal.”

The past 12 months have taught him as much.

Through 2020 and 2021 Lopez has taken many small steps that, ultimately, led to one giant leap into world-class territory. In May last year he lowered his national record to 1:44.40 and then two months later, he hacked almost a full second off that mark, clocking 1:43.44 in Marietta, USA.

It sounds strange, but Lopez was actually happier after the first race. The reason?

“When I ran 1:43, that same day was (the) Monaco (Diamond League meeting), and (Nijel) Amos ran 1:42.91,” he says. “I wanted to be there, so I was frustrated. I thought I could run faster.”

What led to his breakthrough? Lopez’s story is similar to many other athletes who had their worlds turned upside down in 2020, forced to reassess his approach, rebuild his fitness and return better than ever once racing resumed.

“I think the pandemic helped me,” he says.

In 2019 he set a Mexican record of 1:45.03 shortly before the Pan American Games in Lima, Peru, but he was struck down with injury in the heats at that championships and failed to finish.

“In 2020 our philosophy was to get better in the things we do well and fix the things we don’t do well,” he says. “It was to get better in our weaknesses. I was not giving it everything I had (before) and I felt I needed to give a little more to get better.”

Lopez is a full-time athlete these days and trains in Hermosillo, a city of 800,000 people, located in the state of Sonora in northwest Mexico. It’s also where he grew up, first finding athletics at the age of seven, brought to it by his parents, Claudia Alvarez and Ramon Enrique.

At the time, he was playing American football, putting his speed to good use as a running back, and in those early years he “didn’t really care so much” about athletics. His parents, though, made sure he stayed the course.

“They obligated me to train,” he says. “When I was a boy I wanted to (play) American football, soccer, but they were like, ‘no, you’re going to be a track and field athlete.’”

There was no athletics background in his family, but his coach knew talent when he saw it. In 2013 Lopez – then 15 – competed at the World U18 Championships in Donetsk, Ukraine, and it left an indelible mark.

“I realized: I want to do this all my life,” he says.

At 16 he lowered his best to 1:50.33, and competed at the World U20 Championships in Eugene, USA. At 17 he was running 1:48.13. At 18: 1:46.57.

In 2017 he made his first World Championships at senior level, competing in London before going on to win the World University Games title in Taipei. By then he was a student at the University of Sonora, studying physical culture and sports and training under Conrado Soto, who still coaches him today.

Lopez would rise early, training at 6am before his classes, steadily progressing each month, each year. The sporting and academic demands meant he wasn’t able to work on the side, but support from his parents – who started him out on this path – has never wavered.

“Even with not much money, they gave me what I needed to put me in the city where I need to compete,” he says. “The first years were very difficult but thanks to them I was able to be consistent from year to year. They were also always there for me for emotional support. All this, I owe to my parents.”

As he told his story, Lopez was sitting trackside in the Armory, New York City, ahead of the Millrose Games. He’d never raced on a 200m indoor track before but Lopez ran well to finish sixth in 1:48.60.

“It was a very fierce competition but I’m satisfied,” he said. “I can get better and I know what I need to do to be better next time.”

Given his pedigree as a teenager, he had a range of options available to study in the US but Lopez overlooked them in favor of staying at home. “My coach was great, I had my family, my home,” he says. “I don’t need to go to other places when I have everything in Hermosillo.”

Growing up, he had few compatriots to look up to who were mixing it at the top level in middle-distance events, but Lopez is hoping his presence on that stage – both now and in the future – will inspire many others to follow.

“I always wanted that,” he says. “Every competition, I want to have people by my side. It took me a long time to believe I could compete with the (world’s best), but one year ago I really believed. I can compete with them.”

(01/31/22) Views: 599World Athletics

Try this 5K progression run to build your speed, add some variety to your training with this endurance focused speed workout

When training for a goal, we choose to do certain workouts to develop our top-end speed and long runs to help our endurance – but what if there is a workout that can do both? The progression run is a gradual workout that involves a mix of speed and endurance. Its purpose is to boost your aerobic system while still running at a high-intensity effort.

Progression runs tend to start at an easy pace and gradually build up to paces around your goal 5K pace or faster.

The 5K progression workout

To start, base the workout off your previous 5K time (if you have a 5K PB of 25:00 – you’ll want to start the first kilometer around 6:00 per/km).

After the first kilometer, increase the pace by 15 seconds (using the 25-minute PB as an example, 5:45/km) for the second kilometer. Do the same for the third and fourth kilometers, until you eventually get down to your race pace on the fifth.

As the workout evolves your body will get tired, which will make it tougher to increase the pace. It is important to make sure that you hit the pace on the first two kilometers. If you start too fast or slow, it will be hard for your body to perform at your aerobic capacity on the fourth and fifth kilometers.

This workout can be a fun way to add some variety to your training and a confidence booster if you can hit your race pace heading into a 5 or 10K race.

(02/01/22) Views: 104Marley Dickinson

Alberto Salazar’s permanent ban from SafeSport was for alleged sexual assault, new report finds

Just last month, former Nike Oregon Project coach Alberto Salazar had his permanent ban from the sport upheld by the U.S. Center for SafeSport. A new report from the New York Times on Monday revealed it was because an arbitrator found that he more likely than not had sexually assaulted an athlete on two different occasions.

The famed running coach Alberto Salazar, who helped top Americans be more competitive in track and field before he was suspended for doping violations, was barred from the sport for life last month after an arbitrator found that he more likely than not had sexually assaulted an athlete on two different occasions, according to a summary of the ruling reviewed by The New York Times.

The case against Salazar was pursued by the United States Center for SafeSport, an organization that investigates reports of abuse within Olympic sports. SafeSport ruled Salazar permanently ineligible in July 2021, finding that he had committed four violations, which included two instances of penetrating a runner with a finger while giving an athletic massage.

Salazar asked for an arbitration hearing, where he denied the accusations and said he did not speak with or see the runner on the days in question. The arbitrator did not find Salazar’s explanation credible, and accepted his accuser’s version of events.

The details of the ruling, which have not been reported until now, shed new light on why Salazar, a powerful figure within elite running, was specifically barred from his sport. A number of runners have publicly accused him of bullying and behavior that was verbally and emotionally abusive, but the accusations of physical assault had not been publicly revealed. Salazar has never been criminally charged in connection with these allegations.

SafeSport, an independent nonprofit organization in Denver that responds to reports of misconduct within the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic sports, pursued action against Salazar and ruled him permanently ineligible in July 2021.

They currently list Salazar’s misconduct on their database as “sexual misconduct,” though the specific allegations against the coach were not known because they do not release details of its rulings. The report from The Times reveals new details on why the famed running coach Salazar was banned. Until now, the details were unknown.

Salazar has been accused of making comments about teammates’ bodies and weight in the past, but accusations of physical assault had not been publicly revealed. He has not been criminally charged with these allegations.

Numerous athletes have spoken out against Salazar for conduct against women. In November 2019, former high school star Mary Cain, who trained under Salazar from 2013 to 2015, spoke out about years of emotional abuse as a member of the Nike Oregon Project.

After Cain’s public comments, several other members of the project spoke out and shared their own experiences under Salazar.

Salazar, 63, has denied all allegations. In an email to The Times, he said he “never engaged in any sort of inappropriate sexual contact or sexual misconduct.”

Salazar also told The Times that the SafeSports process was “unfair” and “lacked due process protections.”

The United States Anti-Doping Agency also banned Salazar, along with Dr. Jeffrey Brown in September 2019 for four years. Although no athlete training under Salazar tested positive for a banned substance, the USADA determined Salazar tampered with the doping control process and trafficked banned performance-enhancing substances.

Salazar also denied those allegations and appealed that ban. His appeal was denied in September.

(01/31/22) Views: 99NY Times and OregonLive

Kenyan Sebastian Kimaru crashes the Sevilla Half Marathon course record

Kenya’s Sebastian Kimaru made his Internationa debut memorable when he ran the fastest time ever at the 27th edition of the EDP Sevilla Half Marathon that was held on Sunday (30) in Sevilla, Spain.

Kimaru was the surprise winner as he was tasked to pace the race but after the 10km mark he decided to forge ahead and fight for the title as he crashed the previous record of 1:00.44 that was set in 2020 by Eyob Faniel from Italy.

Kimaru cut the tape in a personal best of 59:02 which is the sixth fastest time in history at the flattest half marathon in Europe as he led 1-2 Kenyan podium finish. David Ngure came home in second place 1:00.22 with Gebrie Erkihuna from Ethiopia closing the first three podium finishes in 1:00.27.

All the first three runners ran under the previous course record.

LEADING RESULTS

21KM MEN

Sebastian Kimaru (KEN) 59:02

David Ngure (KEN) 1:00.22

Gebrie Erkihuna (ETH) 1:00.27

(01/31/22) Views: 89John Vaselyne

Matsuda runs 2:20:52 to break Osaka Women's Marathon record

Mizuki Matsuda broke the race record at the Osaka Women’s Marathon on Sunday (30), improving her PB to 2:20:52 to win the World Athletics Elite Label event.

Her time beats the 2:21:11 event record which had been set by Mao Ichiyama last year and moves her to fifth on the Japanese all-time list. It is also the second-fastest time by a Japanese athlete in Japan, behind Ichiyama’s 2:20:29 set in Nagoya in 2020.

Matsuda was followed over the finish line by Mao Uesugi, Natsumi Matsushita and Mizuki Tanimoto, as the top four all dipped under 2:24.

Before the race, Matsuda had explained how her goal was to win the race with a performance that would help her to secure a spot on the team for the World Athletics Championships in Oregon later this year. After winning in Osaka in 2020 with 2:21:47, Matsuda had later missed out on a place at the Tokyo Olympics when Ichiyama ran faster in Nagoya.

“I could not attain my goal today,” she said after the race, with beating Ichiyama’s 2:20:29 a likely aim. “I am happy that my hard training paid off well.

“I think the result was good because I ran aggressively from the start. I just hope that I will be selected for the World Championships team. During the race, I was imagining myself running in Eugene, thinking: ‘How would the world-class runner run at this stage of the race?’”

Despite the pandemic, the event in Osaka was able to go ahead as planned, under good conditions with little of the expected wind.

Matsuda and Uesugi had run together behind the three male pacemakers until just after 25km, passing 10km in 33:02 and half way in 1:09:57 – a half marathon PB for Uesugi.

At 25km the clock read 1:22:47, but Uesugi started to drift back a short while later and by 30km – passed in 1:39:15 – Matsuda had built a 31-second lead.

She went through 35km in 1:56:04 and 40km in 2:13:23, with the pacemakers leaving the race as they entered Nagai Stadium park at around 41km.

Matsuda went on to cross the finish line in 2:20:52 to achieve her third Osaka Women’s Marathon win after her victories in 2018 and 2020, maintaining her unbeaten record in the event.

Although Uesugi’s pace began to slow as she was dropped, she held on to run a big PB of 2:22:29, while Matsushita was third in 2:23:05 and Tanimoto fourth in 2:23:11. Yukari Abe was fifth in 2:24:02 as the top five all set PBs, with Sayaka Sato sixth in 2:24:47. The top six all qualified for the Marathon Grand Championship, the 2024 Olympic trial race.

(01/30/22) Views: 78

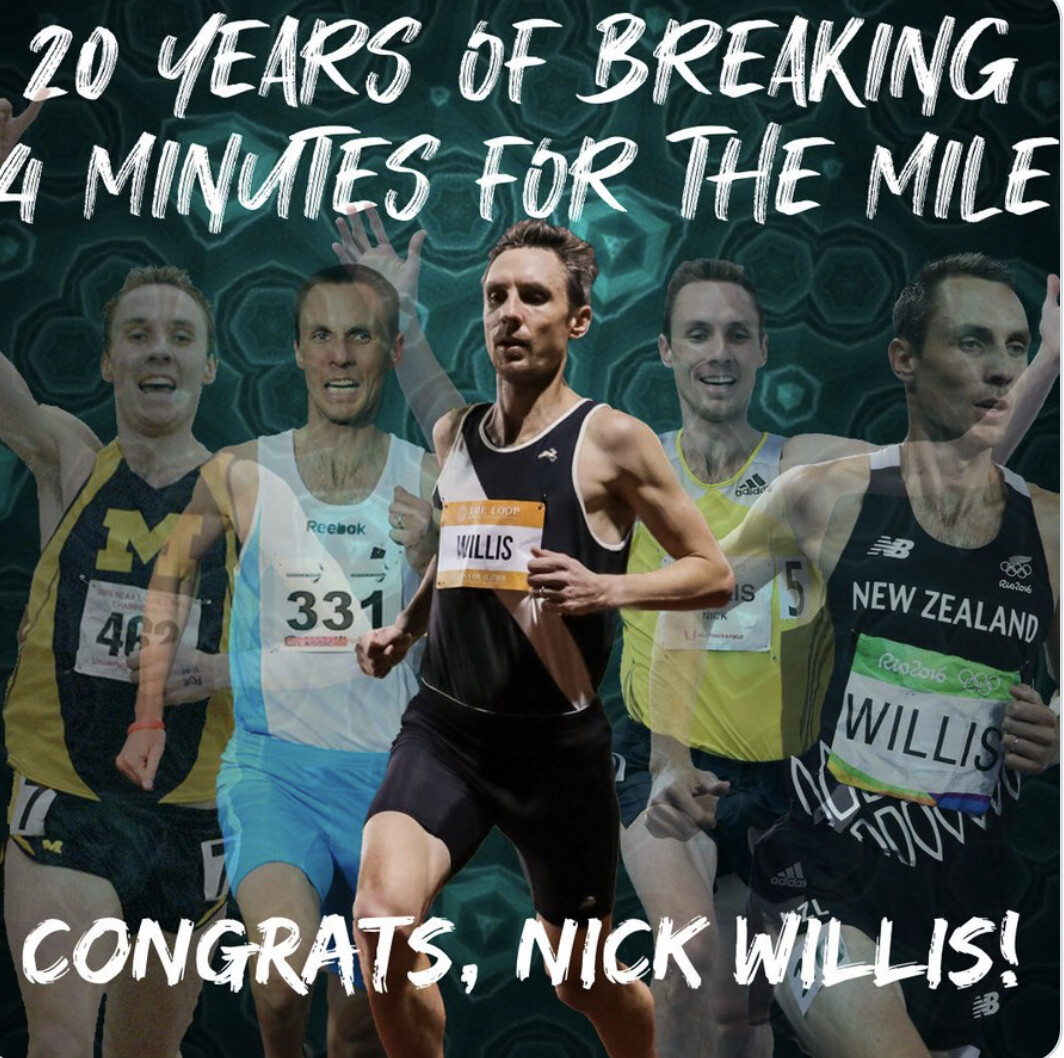

Nick Willis runs sub-four minute mile for 20th consecutive year

Nick Willis ran a sub-four minute mile at the Millrose Games in New York- 20 seasons after first breaking the barrier in 2003.

New Zealand track and field great Nick Willis has earned $25,000 for an athletics charity after completing 20 years of sub-four minute miles.

The 38-year-old finished ninth in the Wanamaker men’s mile at the Millrose Games indoor meet in New York City on Saturday January 29 in 3min 59.7sec.

It was in 2006 that Willis experienced international success for the first time, claiming 1500m gold at the Commonwealth Games in 3:38.49 ahead of Canada’s Nathan Brannen and Australia’s Mark Fountain. That same year, he lowered his mile personal best to 3:52.75.

In 2007, Willis made his first world 1500m final, placing 10th in Osaka in 3:36.13.

The following year, Willis ran what he considers one of his best races to improve his mile personal best to 3:50.66, finishing second behind Kenya’s Shadrack Korir at the Prefontaine Classic in Eugene, Oregon. Two months after that, he went on to claim 1500m silver at the Beijing Olympics in China.

At the following 2012 Olympic Games, Willis had the privilege of being his country’s flag bearer during the opening ceremony held at the London Stadium. He finished ninth in the Olympic 1500m final and had a season's best of 3:51.77 for the mile.

In 2014 at the Glasgow Commonwealth Games, Willis earned 1500m bronze, his third straight Commonwealth medal after the one he had taken in Delhi four years prior. It was also in 2014 that he set his lifetime best of 3:49.83 in the mile, which stood as the Oceanian record until July 2021.

In 2015, Willis clocked a still-standing Oceanian record of 3:51.46 for the indoor mile, and a national 1500m record of 3:29.66 at the Herculis Diamond League meeting in Monaco. That same year he finished sixth with 3:35.46 in the 1500m final at the World Championships in Beijing, his best placing in the competition.

The following year, Willis added two global medals to his tally with a 1500m bronze at the World Indoor Championships in Portland and an Olympic 1500m bronze in Rio.

At 38, Willis was the oldest athlete in the 1500m field at the Tokyo Olympics, where he placed ninth in his semifinal in a season’s best of 3:35.41.

Earlier in 2021, he had already broken the record of 19 consecutive years of sub-four-minute miles. And he finally went on to improve that record to 20 on 29 January 2022 with his 3:59.71 run.

(01/29/22) Views: 73World Athletics

This weekend's Osaka International Women's Marathon will go ahead despide omicron wave

Despite Osaka being named to a preliminary state of emergency as Japan goes deeper into its omicron wave, this weekend's Osaka International Women's Marathon and Osaka Half Marathon are going ahead on their traditional public road courses. Osaka Women's is Japan's last remaining purely elite marathon, and with the mass-participation Osaka Marathon moving to the last weekend of February this year and targeting WA platinum label status the writing has to be on the wall for its future.

It just doesn't seem sustainable to have this race four weeks before the start of a three-week run of platinum label races, one in the same city, one in Tokyo and one in Nagoya.

But for this year, at least, Osaka Women's clearly has the support up top in the local government to keep moving, and that counts for something. Like the 2021 race, despite its name it's a Japanese-only field with male pacers, kind of inevitably on the first point given Japan's ongoing border fortification but a bit regrettably on the second. Take out the "International" and "Women's" and what have you got left?

The win looks almost definitely to be between Mizuki Matsuda (Daihatsu) and Sayaka Sato (Sekisui Kagaku). Matsuda has one of the best records in the sport, with three wins and a 5th-place in Berlin out of five marathon starts, all between 2:21:47 and 2:22:44. The only misfire she's had was a 2:29:51 for 4th in Japan's Olympic marathon trials that left her as alternate. How she would have done if she'd replaced one of the less-than-100% women who ran the Olympics is one of last year's biggest what-ifs. Sato was the 4th-fastest Japanese woman in 2020 and 2021 and set the 25 km NR en route in her marathon debut, a mark that Matsuda broke while winning Nagoya last year. Sato will need a big step up and/or another miss from Matsuda to compete, but it should be a good race.

The supporting cast includes 2019's fastest Japanese woman Reia Iwade (Adidas), and 2021's 3rd and 4th-placers Yukari Abe (Shimamura) and Mao Uesugi (Starts). Osaka Women's factors into the complex algorithms for making the Oregon World Championships team and Paris Olympics marathon trials, and with six other women in the field having run under the 2:27:00 B-standard for qualification for the Olympic trials the race to finish in the 4th-6th place B-standard bracket should be just as good as the one to make the 1st-3rd place A-standard bracket.

Alongside the marathon, the Osaka Half Marathon will also feature two-time Osaka International winner Kayoko Fukushi (Wacoal) in her final race. Fukushi's marathon debut in Osaka in 2008 was possibly the wildest elite-level marathon debut in history, and while she might not have another marathon in her it's great to see her bring her career to a close back where she had one of its most unforgettable highlights. Sub-61 half marathoner Kenta Murayama (Asahi Kasei) leads the men's field in the half in a tune-up for one of the big marathons a month away whose future is still up in the air.

Fuji TV is handling TV broadcasting duties starting at noon Sunday Japan time. Official streaming looks to be through the TVer subscription service, so get your VPNs now. You might have luck with mov3.co too, but use a popup blocker. JRN will also be covering the race on @JRNlive.

(01/29/22) Views: 71Brett Larner

American Jim Walmsley will be taking another stab at UTMB

The 2022 edition of the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB) is seven months away, but the elite fields have been made official. Although he has never done better than fifth (and that was back in 2017), American Jim Walmsley will be gunning for a podium finish again on Aug. 28, along with seven of Canada’s top ultrarunners, including last year’s third-place finisher, Mathieu Blanchard. Check out the top athletes who will be racing this year.

UTMB — men

Blanchard, who is from France but lives and trains in Montreal, is among the top men who will be competing this year. Going into the race, Blanchard says his goal is to win the race, and he’ll have two main focuses for his training: “the first will be to prepare myself mentally, to visualize, to accept this possibility of a big goal because I still have trouble believing it today,” he says. “The second will be to build a logical race path to prepare for this race, choices of reason rather than choices of the heart.”

Last year’s second-place finisher, Aurélien Dunand-Pallaz of France will be returning, along with 2019 UTMB winner, Pau Capell of Spain. Walmsley, whose top finish was fifth in 2017 but who has won the Western States 100 for three consecutive years (2021, 2019, 2018) will also be challenging for a podium spot, as will France’s Xavier Thévenard, who has won UTMB three times (2018, 2015, 2013) and placed second in 2019. Nine other recent top-five finishers will also be joining them on the start line.

Notably absent from the start list is last year’s winner, François D’Haene and three-time UTMB champion, Kilian Jornet.

UTMB – women

Canadian ultrarunning fans will have plenty to cheer about in the women’s race in August. Three top Canadians will be on the start line, including Montreal’s Marianne Hogan, who won the 2022 Bandera 100K and placed second at the Ultra-Trail Cape Town 100k. Toronto’s Claire Heslop, Canada’s top finisher in 2021, will be joining Hogan, along with Alissa St. Laurent of Moutain View, Alta., who placed fifth in the 2018 UTMB TDS 145K in 2018 and sixth at UTMB in 2017.

“My dream result would be a top 10 at UTMB,” says Hogan, “so I will definitely shoot for that. A lot can happen come race day, so I will make sure to show up to the start line as ready as possible.”

Other top contenders on the women’s side include Camille Herron, who won the 2021 Javelina Jundred Mile (and broke the course record) in 2021 and set the 24-hour world record in 2019, Anna Troup, who won the 2021 Lakeland 100 Mile and the 2021 Spine Race Summer Edition 268 Mile, Sabrina Stanley, two-time winner of the Hardrock 100 and Beth Pascal, winner of last year’s Western States and two-time top-five finisher at UTMB.

There will be five other recent top-five finishers on the start line as well, but running fans will be disappointed to hear the two-time winner Courtney Dauwalter, 2019 third-place finisher Maite Maiora, among several other past winners, will not be in Chamonix on August 28.

CCC — women

There will be three elite Canadian women in the 100K CCC, including Victoria’s Catrin Jones, who placed in the top-10 at the 2019 Comrades Marathon 90k and holds the Canadian 50-mile and six-hour records. She will be joined by Ailsa MacDonald of St. Albert, Alta., who won the 2020 Tarawera 100 Mile and the Hoka One One Bandera 100K, and placed sixth in the CCC in 2019. Rounding out the Canadian squad will be Vancouver’s Kat Drew, who was third at the 2019 Bandera 100K, first at the Canyons 100K and eighth at Western States in 2019.

Other notable runners in the CCC include New Zealand’s Ruth Croft, who won the 2021 Grand Trail des Templiers 80k, placed second at the 2021 Western States 100 and won the UTMB 55K OCC in 2018 and 2019. France’s Blandine L’hirondel will also be looking to land on the podium after winning the OCC last year.

(01/28/22) Views: 68Brittany Hambleton

The 2022 Rock ‘n’ Roll Running Series New Orleans Returns Feb. 5-6

The 2022 Rock ‘n’ Roll Running Series New Orleans returns to the Big Easy on Saturday, Feb. 5 and Sunday, Feb. 6. Race weekend kicks off on Friday, Feb. 4 with the Health & Fitness Expo at the New Orleans Morial Convention Center. On Saturday, Feb. 5 race day returns with the 5K and on Sunday, Feb. 6, the participants will take on the half marathon and 10K distances all starting and finishing at the University of New Orleans.

Elite runners from around the world will contest the Rock ‘n’ Roll Running Series New Orleans , Anne-Marie Blaney (USA), Megan O’Neil (USA) and Maura Tyrrell (USA) in the women’s field, and Wilkerson Given (USA), John Börjesson (SWE) and Mo’ath Alkhawaldeh (JOR), who most recently took the overall win at the 2021 Rock ‘n’ Roll Washington D.C. Half Marathon, in the men’s field.

Schedule:

Friday, Feb. 4

12:00 p.m. – 7:00 p.m. – Health & Fitness Expo – New Orleans Morial Convention Center

Saturday, Feb. 5 – Race Day

9:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. – Health & Fitness Expo – Phoenix Convention Center

7:40 a.m. – 5K – University of New Orleans

Sunday, Feb. 6 – Race Day

7:40 a.m. – 10K Start – University of New Orleans

7:40 a.m. – Half Marathon Start – University of New Orleans

9:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. – Encore Entertainment – James Martin Band – University of New Orleans

*All times listed are in CST

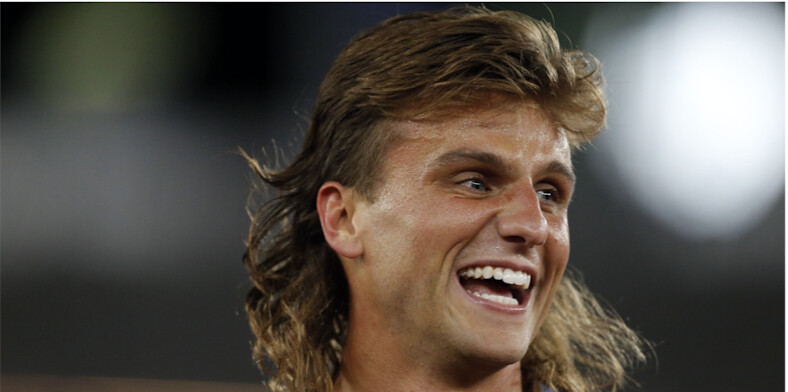

(02/01/22) Views: 65Craig Engels, Running’s Most Committed Party Animal, Returns to Nike—and Running Fast

Craig Engels explains what he can about his new four-year deal and heads to Millrose Games in good shape.

Craig Engels, the fun-loving 1500-meter runner who never misses a party, inked a new deal with Nike in the early days of 2022. It’s a four-year agreement, taking him through 2026.

But he went through a lot of soul-searching before he decided to return to running at a high level.

Engels, 27, finished fourth by half a second in the 1500 meters last June at the U.S. Olympic Track and Field Trials, just missing the team bound for Tokyo.

In the days afterward, he was adrift. “Everything I worked towards [was] over,” he told Runner’s World during one of several recent interviews. “I didn’t know what to do with myself. Which—I don’t know what emotion that is. It wasn’t sadness. More like, what do I do?”

He spent the rest of the summer racing on the track and road circuit in the U.S. He helped pace men who were trying to break 4:00 in the mile, and he encouraged facial hair growth. And still, he raced at a high level, although neither Engels nor his coach, Pete Julian, would say that his training resembled what it was before the Trials.

“We had to change things up,” Julian told Runner’s World last September, “had to piece together workouts in between to keep him so he could at least finish a mile. That’s what Craig needed at the moment.”

On August 14, he finished second at a mile in Falmouth, Massachusetts, clocking 3:53.97. Six days later he finished second again in the international mile at the Prefontaine Classic in Eugene, Oregon, in 3:55.41.

That runner-up finish at Pre came as a result of a premature celebration. He waved to the crowd at the top of the home stretch, but Geordie Beamish of New Zealand sailed by him with a few meters to go.

They hugged it out on the track and then took a victory lap.

“That’s Craig,” Julian said. “He makes mistakes along the way, it’s why he’s so damn popular. I’ve never seen anybody do something as dumb as wave to the crowd and then get beat and still get to take a victory lap. Pretty classic, right? There’s one guy in the world who can do that, and that’s Craig.”

After Pre, Engels shut down his season. In the fall, he returned to the University of Mississippi to finish the final semester of classes he needed to complete his MBA.

While Engels was in Oxford, Mississippi, he trained with Ole Miss cross-country coach Ryan Vanhoy, who had coached him in college, and the Ole Miss team. They logged high mileage and did a lot of long strength-based workouts. Meanwhile, Engels pondered his future.

Engels flirted with retirement, and Julian said Engels was sincere in his questioning, asking himself: “Is this something that I want to do?”

Running the Numbers

As Engels got back into shape and finished his classes, he began the process of negotiating a new contract. Initially, he tried to do it alone. He said he parted ways with his first agent, Ray Flynn, via email between rounds of the 1500 at the Olympic Trials.

Reached by text message, Flynn said, “It’s all good with Craig and I. Happy to see him doing well.”

Engels said he had long struggled with the role of agents in pro running and the fee they charge—15 percent of everything, including sponsorship deals, appearance fees, and prize money—for negotiating what often turns out to be a single contract with a shoe company.

“A lot of these agents were athletes,” Engels said. “I don’t know how they possibly sleep at night, taking 15 percent. NFL agents are capped out at three [percent].”

But as Engels talked to shoe company executives and weighed various offers and training situations, he realized he needed someone to review the contracts—“the lawyer jargon,” he calls it. “I was getting a little stressed,” he said.

So he hired Mark Wetmore as his agent, who also represents Engels’s teammate Donavan Brazier, among others. Wetmore immediately increased the value of the offers Engels had started negotiating on his own behalf.

Engels signed with Nike again. At the end of the four-year deal, he’ll have run professionally for 9 years, and he said it will be his last contract.

The terms of the deal are private—Engels had to sign a nondisclosure agreement, as most athletes do, which also limits the knowledge athletes have about their value in the market.

All he could say about it? “I definitely had some great offers on the table, which led to a very good contract for myself.”

Engels said if it were up to him, he’d post the details of his contract on Instagram to his 97,000 followers. Such knowledge would only help other runners, he says, while the current system benefits agents.

The Athlete Changes the Coach

Engels also returned to train with Julian and his team, recently named the Union Athletics Club (UAC). The club is headquartered in Portland, Oregon, but between altitude stints, training camps, and races, they’re rarely there for long.

He is now doing the bulk of his workouts with Charlie Hunter, who is on the UAC, and Craig Nowak, who trains with the group but isn’t officially on the roster. The group has been training in San Luis Obispo, California—team member Jordan Hasay’s hometown—and enjoying sunny skies and warm weather, and preparing to race the Millrose Games. Engels is entered in the mile.

“I’m in pretty good shape, yeah,” he said. “I don’t want to talk too much before it happens. I’m in pretty good shape.”

After Millrose, UAC hosts an indoor meet in Spokane, Washington, the Lilac Grand Prix, on February 11. The U.S. indoor championships are back in Spokane two weeks after that.

Julian, for one, is glad to count Engels on the roster. He told Runner’s World that Engels has “completely changed” the way he coaches.

“He’s made me realize that making [something] enjoyable and working hard don’t have to be separated, don’t have to be mutually exclusive,” Julian said. “The two things can exist. And we can be really great. But by being able to enjoy ourselves and being able to have some fun. To not take ourselves as seriously, but at the same time, take what we’re doing very seriously. You can do both.”

That’s a startling admission from Julian, who was a longtime assistant coach to Alberto Salazar. He was viewed as in relentless pursuit of every advantage for his athletes. Salazar is now banned from coaching Olympians permanently by SafeSport and serving a four-year ban for anti-doping offenses.

“[Engels has] made me realize that, hey, we can add some color to our lives,” Julian continued. “We’re not curing pediatric cancer here. We’re running around in half tights on a 400-meter circle. Coming from my own background, I’ve had to realize that, too, [with] my own coaching the last four or five years. You know what? Everyone needs to chill out a little bit. Let’s quit trying to eat our own and actually try to promote the sport and race really, really fast.”

One small way that Engels has changed the team? He prefers FaceTime to phone calls. Julian said Engels likes to see people, likes to smile at them. The FaceTime habit has spread throughout the group, so now, anytime anybody communicates on the team, it’s always by FaceTime. “That started from Craig,” he said.

Critics of Engels—who is an unabashed beer drinker, hot-tub soaker, RV driver, and mullet wearer—don’t see the work that he does, his coach says. And they don’t see how hard he tries.

“He did everything he could to make that Olympic team,” Julian said. “He’s done everything he can to make the sport better. He puts forth an amazing effort and he tries to win. But he’s not a robot, either.”

(01/29/22) Views: 54

Runner’s World