Running News Daily

Top Ten Stories of the Week

12/25/2021

These are the top ten stories based on views over the last week.

What All Runners Should Know About Protein

Every runner knows they need carbs, but protein is just as crucial to muscle recovery after a workout. It repairs muscle damage, diminishes the effects of cortisol—the so-called "stress" hormone that breaks down muscle—and, when taken with carbohydrates, speeds your body's ability to replenish its glycogen stores, your all-important energy source for those long runs during marathon season. If you've ever "hit the wall" or "bonked" in a marathon, you know what it feels like to deplete your glycogen reserves.

The 30/30 Rule

To gain the full benefits of protein's power, most sports dieticians and nutritionists recommend getting 10-20 grams of protein within 30 minutes of finishing a run, and some say even sooner—that's when your muscles are the most receptive to a helping hand.

The amount of protein you eat matters; 10 grams is a baseline and 20 grams is optimal, according to Deborah Shulman, who holds a doctorate in physiology. Much more protein than that won't do you any good. A 2009 study published in the Journal of the American Dietetic Association found that consuming more than 30 grams of protein in a single sitting didn't help muscles any further than more moderate amounts. Call it the 30/30 Rule: eat less than 30 grams of protein in less than 30 minutes post-run.

Healthy Protein

What kind of protein is best? The folks at the Harvard School of Public Health recommend fish, poultry and beans. Sure, a big juicy steak will do the trick, but it comes with a price: loads of saturated fat. A 3-ounce serving of salmon (about the size of a deck of cards or a woman's palm) gives you 17 grams of protein and only 2 grams of saturated fat. Beans do fish one better: a cup of cooked lentils has 18 grams of protein and less than 1 gram of fat.

Don't have the time or inclination to cook up a meal? Many athletes fuel post-run with a smoothie or protein shake. Just be sure to watch those protein amounts—some shakes carry a wallop. According to dietician Matthew Kadey, excess protein, like excess everything else, can be converted into fat.

Carb-to-Protein Ratio

Be sure to hydrate and eat plenty of carbs too. Remember, carbs and protein work together to replenish your glycogen stores more efficiently. The jury is still out on the ideal ratio of carbs to protein, but most sports nutritionists say to aim for a 3:1 or 4:1 ratio for your post-run meal, especially when you've run for an hour or longer.

Here's a handy formula from Running Times magazine to figure out how many carbs you should be eating at mealtime: divide your weight in half. That's your magic carb number. You can extrapolate your protein intake from there by dividing that number by three or four.

For a 125-pound runner:

63 grams of carbs, 21 grams of protein in a 3:1 ratio

63 grams of carbs, 16 grams of protein in a 4:1 ratio

And when in doubt, just remember the 30/30 Rule: eat less than 30 grams of protein in less than 30 minutes after a run.

(12/20/21) Views: 88Karla Bruning

How one runner made a bucket list trail running trip into reality - The Dream: Running Hut-to-Hut in the Dolomites

By Andy COCHRANE

I was no more than 8 years old when I saw my first photo of someone running in the Dolomites. Red windbreaker, dark shorts, storm brewing over a line of jagged peaks. I cut it out of the magazine (don’t tell my mom) and still have it in my wallet today. For years, trail running in the Italian Alps wasn’t on my bucket list; it was my bucket list.

This fall, I finally got to check it off. Along with two friends and my coach Magda Boulet, I flew to Venice and drove north into the Dolomites. We spent a week running from hut to hut, meandering 20 miles each day, stopping for cappuccinos and strudel and staying at small, family-run rifugios high up in the mountains.

It was a trip of hearty laughs, long meals, stout climbs, loose descents and a handful of exposed ledges to tiptoe across. But the top of the long list of highlights was the people we met. The kindness and care we received from total strangers was unlike anything I’d ever experienced.

Route & Rifugios

We worked with a local guiding company, Dolomite Mountains, that made our planning easy. They offered suggestions on trails, places to sleep and peaks to climb. Our route took us 100 miles from San Candido to Compatsch, along a few of the major thoroughfares. We ran through the Sesto subgroup of mountains, on the border of Italy’s German-speaking South Tyrol and the Italian Veneto region, which was the frontier of Austria and Italy in World War I.

Many of the trails here were developed by soldiers– old trenches, defensive barricades and forts are still visible in many places. On our first day we ran under Tre Cime, a trio of peaks that reminded me of home in the Tetons. We continued through remote valleys and high passes in Fanes-Sennes-Braies Nature Park, through the iconic Alta Badia valley, past Puez Nature Park to Val Gardena, through a beautiful alpine meadow called Alpe di Siusi, then summited Plattkofel and climbed up Rosszahnscharte, our last major pass, before running all the way down to Compatsch.

For the first two days we were led by Paolo Posocco, a local runner and incredibly knowledgeable guide, who offered a steady buffet of insights on the ecology, history and trails of the area. After two days with Paolo, we were sad to see him go– and still stay in touch to this day.

There are dozens of bucolic rifugios, but a few stand out from the rest. Drei Zinnen Blick is in a valley adjacent to a beautiful lake, close to Tre Cime. Rifugio Fodara Vedla is perched high in the range, with no cell service and warm and friendly hosts that make you feel like family. Rifugio Sassopiatto has some of the best views, perched on a ridgeline. Gostner Schwaige, a small restaurant near the very end of our run, was hands down the best food we had all trip.

Weather & Seasons

We spent the last week of September in the Dolomites, which is squarely in the fringe season. With cool temperatures (we had more than one frosty morning), leaves changing color and admittedly fickle weather, I think it was the perfect time to visit. There were considerably fewer tourists than during the peak seasons, making trails more fun to run. Midday rifugio stops were quieter and we had a lot more options for places to stay, making our interactions with hosts and immersion into local culture that much more intimate.

Gear We Used & Loved

Outdoor Voices Exercise Dress– OV only recently started making gear for the running scene and hit the mark with this dress. Breathable fabric, adjustable straps, two pockets and a built-in liner make it great for long days in the mountains.

Outdoor Voices Fast Track Shortsleeve– Less is often more. This running tee is comfortable, breathes well and is lightweight, everything I ask for in a good running base layer.

Stio Fremont Stretch Fleece Jogger– We had a lot of cold mornings when shorts wouldn’t quite cut it. These breathable fleece tights move with you and are some of the comfiest tights we’ve ever tested.

Stio Alpiner Hooded Jacket– A must-have layer for any high-output alpine missions, the Alpiner rarely overheats even when you’re sweaty. Stretchy and water resistant, it was perfect for our cool, misty days.

Tracksmith Brighton Base Layer– One of the brand’s most popular pieces for a reason. With a Merino wool mesh that’s more open around the core, it keeps your extremities warm while not overheating the rest of you. Plus it’s odor resistant, which is a huge bonus on a week-long trip.

Tracksmith Off Road Shorts– Designed for long days on the trail, these 2-in-1 shorts have a light outer layer with compression shorts underneath, a back belt for carrying an extra layer, two waist pockets for snacks and liner pockets for your phone or keys.

Ciele ALZCap– The newest iteration of the widely popular GOCap, it has more mesh coverage to maximize breathability and a more fitted, low profile look than previous versions.

Skida Nordic Hat– The brand’s first product hasn’t changed in years, for good reason. Originally designed for cross country skiing, we found the Nordic hat to be perfect for fall running. It wicks moisture while keeping you comfy and warm, and is easy to stow when not in use.

Brooks Catamount Trail Shoe– The trails in the Dolomites are rocky and rough, which means a shoe with good traction is key. With a unique rubber grip, foam cushioning and a protective midsole layer, the Catamount helped us get up and down half a dozen mountain passes.

Coros Apex Pro Watch– With an incredibly long battery life, accurate tracking and well-designed mapping features, the Apex Pro played a key role in keeping us on route and on time.

(12/18/21) Views: 82Trail Runner Magazine

Professional singer caught cutting course at Vienna City Marathon

On Sept. 12, British musician James Cottriall ran the Vienna City Marathon, setting an eyebrow-raising personal best of 2:56:46. Upon a further breakdown of his result by Derek Murphy of marathoninvestigation.com, it became obvious that Cottriall’s cut the course on an out-and-back route between 32 and 35 kilometres, clocking a world record 5K split of nine minutes.

Cottriall was on pace for a 3:10 to 3:15 marathon at the 30K mark when he decided to cut the course. What made his activity more suspicious was the singer’s uploads on his Strava page: “I am feeling ready, it’s time to break 3 hours! The training is done, my legs are prepared!” Clearly, he said the sub-three-hour marathon goal in his mind before the start of the race.

After the marathon, the singer did the media rounds, appearing on Austrian news shows and doing an interview with Heute.at, where he talked about beating Austria’s Labour Minister, Martin Koche, and how he ran the marathon off six hours of sleep while promoting his new album. Cottriall also spoke with Heute about his four months of training leading up to the race where he ran 100 km per week. But on further investigation, his highest training in last the year was one 90 kilometre week.

Cottriall crossed the line in 75th place and said after the race that breaking three was a lifelong dream. In 2019, Cottriall legitimately ran Vienna City Marathon in 4:03:51 and the LA Marathon in 3:55:04. “I am unsure of his motivation,” says Murphy. “He would have run a fast time and still shattered his marathon personal best even without cutting this small section.”

Earlier this year, Cottriall released his fourth album “Let’s Talk,” which was written throughout the various lockdowns in Austria. He has also appeared as Fauke on Austria’s version of The Masked Singer in 2020.

(12/18/21) Views: 74Marley Dickinson

Olympic Bronze Medalist Molly Seidel has started a YouTube channel

Her first video gives you a behind-the-scenes look at her trip to the New York City Marathon.

Molly Seidel fans have another place where they can follow along with their favorite runner. The Tokyo Olympic bronze medalist has started her own YouTube channel, and her first video, which follows her during her trip to the New York City Marathon, is full of that goofy charm we’ve all come to know and love from Seidel, along with a few snot rockets.

Barely three months after her incredible third-place finish at the Tokyo Olympic Marathon, Seidel finished fourth at the 2021 New York City Marathon in 2:24:42.

Her time broke the previous American course record of 2:25:53, set by Kara Goucher in 2008. She revealed after the race that she had fractured a few ribs during her build-up to New York, making her performance through the five boroughs even more outstanding.

“This was truly one of the most challenging marathon builds I’ve ever had to do — mentally and physically,” Seidel says in the video. “Just getting through the amount of pain, the de-motivation after the Olympics, dealing with the pressures that now come from being an Olympic medalist and the eyes on you.”

(12/20/21) Views: 74Brittany Hambleton

Scottish veteran Paul Forbes smashes 800m world masters record

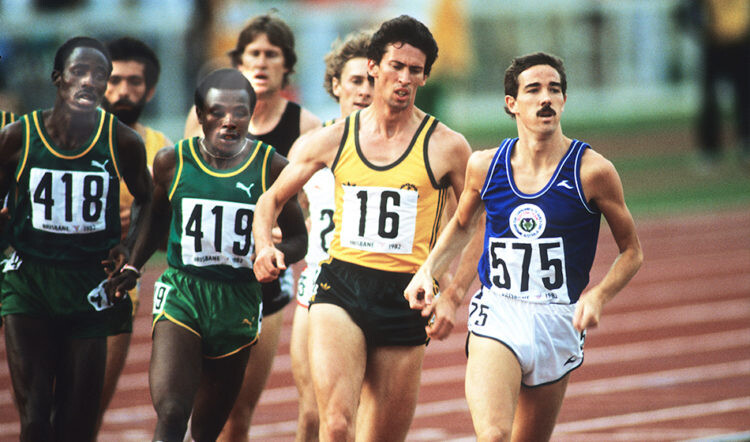

Scottish veteran and three-time Commonwealth Games competitor smashes M65 indoor mark with 2:15.30.

Glasgow 12’s Fun Day & Glasgow AA Yuletide Open Graded Meeting, December 18 Almost 40 years since he reached the 1982 Commonwealth Games 800m final (a feat he repeated in 1986), Paul Forbes broke the world M65 indoor 800m record with a 2:15.30 clocking.

The time is half a minute outside his lifetime best – 1:45.66 set in Florence in 1983 behind world silver medalist Rob Druppers’ 1:45.12.

Forbes finished third in his heat behind Cumbernauld’s Dylan Drummond, who is 45 years his junior and who won in 2:01.49, plus Scottish M40 Stephen Brown (2:09.25).

Showing the great range of ages in the race (a 51-year age gap), behind Forbes came 14-year-old Lydia Simon in sixth and first woman in 2:20.75.

Forbes began as a cross-country runner and won the Scottish East District Junior Boys Championships in 1969 and he was sixth that season in the Scottish Championships. In 1973 he won the Scottish Schools 1000m steeplechase title and then won over two laps in 1974 in 1:58.0.

In the Scottish Under-20 Championships he was second in 1:56.5 but ahead of future Commonwealth Games 1500m medalist John Robson and in 1975 he won the AAA Junior title in 1:50.1 and made the European Junior final that year in Athens where he placed eighth.

Forbes won the UK title in 1982 in a championship best 1:46.53 narrowly ahead of Steve Caldwell (1:46.65) and Peter Elliott (1:47.76) and he also ran for Scotland in the 1978 Commonwealth Games where he was a semi finalist.

After his successful senior career – spanning three Commonwealth Games – he had a complete break in his 30s before later returning as a master and he was involved in a stunning battle with Alastair Dunlop in the Scottish Championships in his first major race as a vet with Dunlop edging home in 2:00.60 to Forbes’ 2:00.61.

After that 1997 race Forbes said he felt he was capable of a world masters record if he could train seriously but the world record ultimately took nearly another 25 years with injury regularly scuppering his ambitions.

He competed in the European masters 10km as an M45 in 2005 and ran a few other masters road championships before eventually re-focusing again on the track.

He made another comeback as a M60 – finishing sixth in the World Masters 800m at Toruń in 2019 and winning the Scottish and British masters indoor titles in 2021 at the age of 64 – but it was turning 65 in November that gave him the opportunity to make a real mark in the masters.

The previous best was held by Ireland’s multiple world age-group champion Joe Gough with 2:16.65 in Dublin in 2018.

Forbes’ 2:15.30 is his fastest in recent years, equaling his outdoor best of 2021 and is even faster than the outdoor UK M65 best.

The Scot’s run took an astonishing nine seconds off of Pete Molloy’s UK indoor best of 2:24.48 set in 2014 and is even fractionally quicker than Dave Wilcock’s M60 UK indoor record of 2:15.60.

(12/21/21) Views: 65Steve Smythe

Do these things to recover faster after your race

After running a half marathon, the last thing you’ll want to do is more work. But taking the time to properly recover can prevent long-term injury and get you back into shape sooner.

Richard Neitzelt, PT, DPT, SCS and Katherine Wayman, PT, DPT, SCS, physical therapists at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, offer some advice on recovering in the first few hours after your race.

Take these four tips into account after your next race and you’ll be on your way to feeling better in no time at all:

1. Stretch right away

Neitzelt explains that stretching isn’t guaranteed to totally prevent oncoming muscle soreness, though it does provide an opportunity to improve your flexibility and expedite the healing process. Exercising loosens up and brings blood to your muscles, making them more willing to stretch. Stretching within the first 15 minutes following the race takes advantage of this state and can leave your muscles more flexible than they were before the race.

Post-race stretches should be static rather than dynamic, meaning they don’t involve extra movement. Static stretches involve holding the muscles in a stretch for an extended period of time, typically around 30 seconds. Static stretches are repeated two to three times on each muscle and have the added benefit of allowing the body to mostly rest, which lets the muscles start replenishing spent glycogen.

Neitzelt suggests focusing on muscles that you know are usually tight or weak and returning to these spots multiple times during the post-race cool down. A foam roller or massage stick can also help target a specific area and massage the muscles more deeply than a regular stretch would, bringing in extra oxygen and blood flow.

2. Change into warm, dry clothes

The clothes will help keep your muscles warm and let them ease back to normal. Leaving your muscles exposed leads to a rapid decrease in temperature that will force them to tighten up before they’re ready.

3. Grab a snack

Eating is necessary to give the body fuel to start putting itself back together. Recovery doesn’t start until you bring in nutrients. Wayman suggests a balance of carbs and protein, offering a turkey sandwich or a smoothie with whey protein as easy, effective options. Sodium and a little sugar are also helpful, so have some pretzels and drink fruit juice along with plenty of water.

"Replenishing fuel and fluids is absolutely IMPERATIVE after a race. Everyone wants to train like they’re an elite athlete, but no one wants to recover like one," says Wayman.

4. Take a nap

After stretching and eating, you’ve put your body on the path to recovery. Get home and shower, then try a 15-minute ice bath for your lower body. After that, take a nap or just let yourself rest.

Taking care of your body is an ongoing effort, and the hours immediately following the race are crucial.

Proper recovery is necessary to get your body back into shape without any problems. Running a half marathon leads to a lot of wear on the body, even with proper training. Starting recovery right away means your muscles will spend less time in their worn-out state, avoiding damage and getting you back to pre-race shape sooner.

(12/21/21) Views: 63Noah Mastruserio

World 100 meters champion Christian Coleman to make his return from 18 months suspension at Millrose Games

Christian Coleman, who served an 18-month ban for breaching anti-doping whereabouts rules, plans to race for the first time in nearly two years at New York's Millrose Games, the American told Reuters.

Millrose Gemes will be his first since February 2020 after the COVID-19 pandemic and the anti-doping suspension curtailed the 25-year-old's career.

"I think it will be emotional to get out there and finally display my talents again," the indoor 60m world record holder said by telephone from Lexington, Kentucky, where he trains.

The Atlanta sprinter had been given a two-year suspension by an independent tribunal of track and field's Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU) before it was reduced to 18 months by the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS).

Under the so-called whereabouts rule, elite athletes must make themselves available for random out-of-competition testing and state a location and one-hour window where they can be found on any given day.

"I think it comes down to being more responsible," said Coleman, 25, who has never failed a doping test but was suspended after three failures to be at a location provided to anti-doping officials.

"Those are the rules and I just have to do better."

An alarm on his phone that reminds him to update his schedule daily and a new doorbell that alerts him to visitors are helping to prepare for testers, he said.

Training continued throughout most of the suspension, which ended in November, and he had begun speed work, Coleman said.

He does not see Millrose as just a trial run.

"I want to win," said Coleman. "I think I have a higher standard for myself than just being back out there and being average."

He said he would see how his body feels before determining his indoor season, though defending his world indoor 60m title in March in Belgrade is definitely on his schedule.

"The ultimate goal is to be ready for the world (outdoor) championships" said Coleman.

That meet in Eugene, Oregon in July will be the first World Championships held in the United States.

Whether Coleman will just defend his 100m title or add the 200 remains to be seen but he plans to run both during the regular season.

While he said he had "come to terms" with missing the Tokyo Games because of his suspension he wants to compete in Paris in 2024 and Los Angeles four years later.

Beyond that, Usain Bolt's 100m world record of 9.58 seconds remains on his bucket list.

"As time goes on, I think it is possible," said the American, who ran a personal best of 9.76 in winning the 2019 world championships.

Coleman said he wanted to be remembered as "one of the great competitors in sport".

"I want people to think of me as one of the legends, one of the great sprinters who have come through the USA ranks," he added.

(12/20/21) Views: 60Gene Cherry

The Long Slow Distance Run vs. Tempo

In the traditional marathon training plan, a long slow distance (LSD) run serves as the cornerstone. The LSD run is often prescribed as a weekend run, anywhere from 2-3 hours long, and run at a pace about 30-90 seconds slower than your goal race pace.

By contrast, the tempo run is much shorter and sometimes mixed into a training plan. Tempo works as a speed day when track workouts aren’t an option. The most common tempo run is about 30 minutes at a pace you can hold for the duration.

Recently there has been a lot of debate over which run is better in training for the half marathon and marathon. The new argument is that speed and endurance can be accomplished without spending early weekend mornings running long, slow miles. In addition, some argue that the long, slow run can lead to injury.

So is one really better than the other?

First, it’s best to understand what each training run does for your body.

The LSD, according to running coach Brad Minus, is meant purely to build aerobic endurance.

“When running at a ‘conversational pace’ as I like to call it, the runner breathes more naturally,” he says. “By breathing more deeply the body is provided with more oxygen which translates into a higher capillary density, which, in turn, increases mitochondria.”

If you remember back to biology class, mitochondria are found in cells and are part of the respiration and energy production—both of which runners need.

“The more oxygen in the cells of the muscles, combined with glucose, makes more ATP which is the energy source that moves the muscles,” says Minus. “Endurance cannot be built without increasing the transport of oxygen.”

For newer runners, the long slow run can greatly improve their aerobic endurance and help them reach new distance goals. The newer the runner, the more they can benefit from a long, slow run. Often times, newer runners set a mileage goal for a long run and that also helps boost their mental confidence.

The tempo run will burn through energy more quickly but helps a runner increase the overall quality of training runs. These help a runner incorporate more race day scenarios, such as running hard when your legs become fatigued. Physiologically the tempo run increases a runner’s lactate threshold, the point at which your body fatigues.

In reviewing both the LSD and the tempo run, it would appear that the answer to this debate lies somewhere in the middle, and the long, fast run could be the answer to gaining both aerobic endurance and increasing lactate threshold.

“High-end aerobic endurance athletes thrive off lots of work ranging from long steady runs at marathon pace to runs done at threshold,” says running coach and two-time U.S. Olympic Trials qualifier Mason Cathey. “Alternating paces has been found to be very productive for slow-twitch athletes.”

According to Cathey, slow-twitch runners have better aerobic fuel systems, are not sprinters, and can handle longer runs. She prescribes a variety of runs to her athletes including long runs that incorporate fartleks and short tempos or progressive finishes.

“Speed endurance with anaerobic work is helpful for when we want to maximize performance, but we don’t want to do so much speed that we deteriorate on aerobic strength,” she says.

So there you have it—sort of. The best recipe is one that includes a variety of ingredients. Don’t be shy about pushing yourself with speed work, but maintain an LSD-to-tempo balance for best results.

(12/18/21) Views: 51Beth Shaw

Can undiagnosed celiac disease put you at risk for bone stress injuries?

Bone stress injuries are common among runners, particularly females. There are many possible reasons they might occur, but recent research has determined that undiagnosed celiac disease could put affected runners at a higher risk for these types of injuries. While the portion of the population with celiac disease remains very small, it may be an important consideration for some runners when evaluating their injury risk.

Prevalence of celiac disease

The study, which was published in the Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, tested 85 runners for celiac disease using Anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody (TTG) testing. Two participants already had pre-existing celiac disease and three more were confirmed to have celiac disease following an endoscopic biopsy.

In total, approximately five per cent of the group were confirmed to have celiac disease, which is five per cent higher than Canadian population estimates, according to the Canadian Digestive Health Foundation. It’s worth noting, however, that experts believe about 90 per cent of cases go undiagnosed.

There was one thing every runner in this study had in common: they all had a bone stress injury. When left untreated, celiac disease can damage the small intestine, which leads to poor absorption of vitamins and minerals that are important for bone health, like calcium and vitamin D. This, ultimately, could put someone at an increased risk for injuries like stress fractures.

Of course, it’s difficult to definitively say that the patients with celiac disease were at greater risk because of their condition, but considering that this population had a five times greater prevalence of celiac disease than the general population, it is possible that there could be a correlation. This lead the researchers to conclude that “anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody screening for CD should be considered in all patients presenting with BSIs (bone stress injuries).”

What should runners do?

If you’re generally healthy and aren’t presenting with any of the symptoms of celiac disease (like diarrhea, fatigue, weight loss, bloating and anemia), it’s unlikely you have the condition. If you do frequently struggle with one or more of those symptoms, it’s worth looking into, not only to help prevent stress fractures, but several other health problems as well.

(12/17/21) Views: 50Brittany Hambleton

The Four Pillars of Distance Running

1. Aerobic Conditioning

When the term “aerobic conditioning” is mentioned, miles and miles of running immediately come to mind—but that is only one aspect of aerobic conditioning.

I like to compare aerobic conditioning to communication—when communicating, you are attempting to get information or a message from a sender to a receiver through a medium or channel. Without any one of those aspects, the message does not travel. In aerobic conditioning, you are attempting to move oxygen from a sender to a receiver through a medium. The sending is done by your heart and lungs, and to maximize the those organs’ abilities to transmit oxygen, you need to develop more capillaries—which are built up by the body when an athlete performs an aerobic function for longer than 60 minutes (but are more effective for lengths of effort longer than 75 minutes).

That takes care of sending, but what is the receiver? And, how is the ability to receive maximized?

The receiver is the muscles, and we increase the muscles’ ability to take on oxygen by training at or close to the velocity at which the maximum volume of oxygen can be moved, or vVO2max. vVO2max training is done as repeats in bouts of 90 seconds to about five minutes with a rest interval that is approximately equal to the duration of vVO2max effort.

Last is the medium in which the oxygen travels. Well, we all know that oxygen is carried in red blood cells through arteries to the muscles, except for the veins, which carry oxygenated blood from the alveoli of the lungs back to the heart. So how is that process improved?

Being able to move in the most efficient manner possible.

Getting rid of the excess hydrogen ions in the blood that is broken down from lactic acid buildup due to burning glycogen without oxygen with higher-intensity running.

Efficient running (or running economy) is developed and improved by a combination of the next three pillars. Your body’s ability to get rid of hydrogen ions is developed by training at a velocity equal to about 80% to 90% of an athlete’s vVO2max. That is done by what is known as tempo running (which is closer to the 80% area), lactate threshold or cruise intervals (done at about 85%), and critical velocity, which is 90% to 91% and also has a vVO2max improvement component.

2. Speed or Anaerobic Condition

The next pillar of distance running is speed or anaerobic condition (which by definition means “without oxygen”). With regard to the high school cross country distance of 5k, science tells us that anaerobic use of fuel comprises about 7% of an athlete’s effort. That is where many coaches come up short in their application of anaerobic training.

That’s not to say that speed is the only thing it takes to make a distance runner. On that thought, in 1987, Bob Kennedy won the Kinney (now Footlocker) National Cross Country Championship. A year later, as a true freshman at Indiana, he won the NCAA National Cross Country Championship. He was the first native-born American to break 13 minutes in the 5,000-meter event and never ran more than 35 miles a week in high school—and, after that, about 45 miles a week as a pro with mostly speed work as a staple of his training.

High school coaches all over the U.S. got a hold of that information and created maybe the worst decade in American high school distance running in history. Running a 3200m in under nine minutes was rare in the 1990s. Where are we at now? At the last Arcadia Invitational, 14 runners finished faster than nine minutes in one meet. So, where does that leave us with speed? More than just training your body to use a fuel source without the use of oxygen, anaerobic speed training has several other functions.

First, running fast is a skill that utilizes a combination of strength, reactiveness, and coordination, all of which must work in unison to perform effectively. That skill is no different than hitting a baseball, throwing a football, or even shooting a basketball. If an athlete in any of those sports spends time not practicing those functions, they lose muscle memory for that skill. It is for that reason that speed work must be a part of a distance runner’s training, year-round.

Why does a distance runner need the skill of speed? The more comfortable a distance runner is at running fast, the easier it feels to run at an aerobic race pace and the more economical the athlete performs the function of running. Speed is an athletic movement. Endurance runners do well in distance races, but endurance athletes win distance races. Speed helps turn the endurance runner into an endurance athlete.

Several forms of speed training can be utilized to build the function of speed in the athlete. Speed training as basic as 60-yard strides at the end of a warm-up can be trained almost on a daily basis. Flys of 30-50 meters are also useful. The types of speed training utilized by most distance coaches are:

Speed

Speed endurance

Special endurance 1

Special endurance 2

Those distances go all the way up to 600 meters and build fast twitch, strength, and lactate tolerance. The variance of distances and speeds used together and sequenced properly in a macrocycle work together to prepare the athlete for the culminating event.

3. Strength and Mobility

If you wanted to build a V8 engine that can also go from 0-60 in a few seconds, you wouldn’t put that engine in the frame of a Pinto. That’s where this third pillar comes in—if you assign the work required to build a strong, aerobic, and fast athlete into a young runner without a strong athletic background, many stress-related problems will start to occur because their body just can’t handle it.

So, what type of strength does a distance runner need in order to handle the stresses of training required to improve? The basic answer is…all of it.

I like to build strength from the knee to the shoulder and all points in between. Start with the quadriceps to the hip flexors with the lunge matrix or band work, and the runner can handle the mileage required to build an aerobic engine. The abdominal and all the core muscles help the athlete hold form throughout the race; if that form breaks down, it could reduce the runner’s speed and efficiency while increasing the likelihood of injury.

The chest and shoulder strength come in at the end of the race—during the kick, extra upper-body strength is used to bring about that last bit of form and speed needed to win the sprint finish. Mobility comes into play with the reduction of stiffness of muscles and joints, which could adversely affect movement, cause reduced efficiency, and increase the risk of injury. Strength training should be performed throughout the year and macrocycle to an extent necessary to prepare the athlete to perform their best.

4. Rest

I’ve heard many coaches talk about how their athletes performed due to a specific type of training or workout, but athletes don’t actually respond to a program or workout—they perform as a result of recovering from the stresses of that program or workout. Rest is essential. The stress put on an athlete flexes the body—if they don’t recover from that stress, they cannot benefit from it. The various stresses create micro tears in the muscle and those tears need to heal. That’s where recovery comes in.

Rest in distance running comes in different forms at different times, and for different reasons. Easy running is a form of rest. The reason the athlete runs on a recovery day instead of no work at all is that the run elevates the runner’s pulse to above 120 beats per minute. That helps bring the healing blood to the damaged tissues from the hard workout and flush out the toxins created by the damage of the workout. Recovery days should be treated with as much importance as each hard workout day.

Another form of rest is sleep. The endurance runner experiences a stress that is unlike most other athletes, and most of the healing from that stress comes through sleep. An endurance athlete needs at least eight hours per night, and if that is not possible due to schoolwork or other factors, the coach should alter or reduce the training because the athlete is unable to properly recover from the workout.

The last type of rest is actual days off. During a macrocycle, a rest day can be done a few ways without reduction of performance. Once a week is the most popular among high school athletes; however, a high school athlete should not go more than 21 days without at least one rest day.

Outside of the macrocycle, the athlete needs a rest period more for psychological than physiological reasons. High school coach and physiology teacher Scott Christensen says a high school runner needs about six weeks off in a calendar year. Other coaches say that rest of longer than two weeks at a time leads to injury once the athlete starts back up. The best method is the one that works for your program and athletes, but they do need some form of a rest period following a season.

(12/18/21) Views: 50Jeremy Duplissey