Running News Daily

Top Ten Stories of the Week

6/26/2021

These are the top ten stories based on views over the last week.

Western States 100 preview: pre-race favourites

Women’s field - There are three former WSER champions entered in this year’s race: Gallagher, who won in 2019, 2016 winner (and 2019 third-place finisher) Kaci Lickteig and 2015 champ Magdalena Boulet. All three women are American, and they’ll be joined on the WSER start line by several of their high-profile compatriots. Brittany Peterson, the second-place finisher from 2019, will be in the race for just the second time in her career, along with Nicole Bitter, the seventh-place woman in 2019, which was also her WSER debut.

Pascall and Drew headline the international entries in the women’s field. Pascall, who hails from Great Britain, finished fourth in 2019, and she is a serious threat to take the win this year. Earlier in 2021, she won the Canyons 100K in California, and in 2020, she broke the Bob Graham Round FKT in her home country. She has also recorded two top-five finishes at the past two editions of the famed Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc. Pascall is in incredible form, and she’s a threat to run away with this year’s race, which would make her the first non-American woman to win the WSER title since Ellie Greenwood (who is British but lives in Canada) in 2012.

This will be Drew’s second WSER appearance, and she, too, has what it takes to improve on her result from 2019. She has several big wins to her name, including top finishes at the Chuckanut 50K and Canyons 100K in 2019. She has also represented Canada at the IAU Trail World Championships. B.C.’s Sarah Seads will also race in California, making her first WSER appearance.

When it comes to debut WSER runs, there are several big names to watch. New Zealand’s Ruth Croft is having a tremendous season, with a pair of big wins. Her first came at the Tarawera Ultra in Rotorua, New Zealand, where she won the overall title in the 102K race. A few months later, she was in action in Australia, where she won a 50K race in Katoomba, a town west of Sydney, at Ultra-Trail Australia.

France’s Audrey Tanguy is also running WSER for the first time. Tanguy has had a great year so far, first winning the Hoka One One Project Carbon X 2 100K event in Arizona in January and then following it up with a third-place finish at the Canyons 100K in April. She is also a two-time UTMB TDS winner (2018 and 2019).

Finally, there’s American ultrarunning star Camille Herron. The owner of multiple American and world records, Herron is another threat for the win at WSER. She has won the Comrades Marathon, multiple world championships and many other races around the world, and it shouldn’t be a surprise if she adds a top WSER finish to her resume.

Men’s field - The only WSER champion in the 2021 field is Walmsley, who has won the past two editions of the race. In 2018, he won in 14:30:04, and a year later, he set the course record with an incredible 14:09:28 run. This year, he has raced one ultramarathon, Hoka’s Project Carbon X 2, which he won in 6:09:26, coming extremely close to breaking the 100K world record of 6:09:14. That was several months ago, but if his fitness is anywhere close to where it was at that race, he should be able to lay down another historic WSER run.

Walmsley’s fellow American Jared Hazen, the 2019 runner-up, is also set to race this year. In 2019, Hazen ran a remarkable time of 14:26:46, which would have easily won him the WSER title if Walmsley hadn’t been in the race. He’ll be looking to take that final step onto the top of the podium this year.

A pair of Americans making their WSER debuts are Tollefson and Hayden Hawks. Tollefson has several big wins to his name in the past year alone, including titles at the 2020 Javelina Jundred 100 Miler and USATF 50-Mile Trail Championships. He has also recorded victories at the 120K Lavaredo Ultra-Trail race in Italy in 2019 and the 100K Ultra-Trail Australia in 2017, along with a pair of third-place finishes at UTMB in 2016 and 2017.

Hawks has won many races throughout his career, including the JFK 50-Miler in 2020. He set the course record of 5:18:40 at that race, beating Walmsley’s mark of 5:21:28 from 2016. The WSER course is twice as long as the JFK 50, but Hawks has proven he can match or better Walmsley’s efforts, so it will be interesting to see how he fares in California.

(06/20/21) Views: 296

Running Magazine

World Athletics commits an extra US$1million prize money for athletes at World Athletics Championships

World Athletics today announced it was substantially increasing the prize money for athletes at its flagship world championships, starting with the World Athletics Championships Oregon22 next year.

US$2 million has been ringfenced from the fines paid by the Russian Athletics Federation for breaching the sport’s anti-doping rules, to go directly to athletes in the form of prize money at the WCH Oregon22 and at the WCH Budapest 23.

Speaking from the US Olympic Trials in Eugene, Oregon, World Athletics President Sebastian Coe said: “The last 18 months have been really tough for thousands of athletes who make their living from competing in events around the world. While we have focused on helping meetings around the world stage as many events as possible over this period – more than 600 events – we know many athletes had a very lean year last year and are still experiencing challenges this year.

“Last year we also set up an athlete fund, supported by some generous donations, to provide some financial relief to those athletes most in need. 193 athletes from 58 countries were granted up to US$3000 to go towards basic living costs such as food, accommodation and training expenses.”

World Athletics will fund the additional $1million per World Championships for the next two editions, with each of the 44 individual events receiving an additional US$23,000 of prize money at each championship.

At the most recent World Championships in Doha in 2019, US$7,530,000 in prize money was distributed to athletes who finished in the top eight of an event.

While the intention is to see the new funds go to as many athletes as possible in leading positions, the Athletes’ Commission and Competition Commission will make a recommendation to the World Athletics Council on how the funds will be allocated. The additional US$1 million in prize money will form part of the host city contract from 2025 onwards.

(06/21/21) Views: 220World Athletics

Sarah Lancaster was born to run but she also excelled in tennis and basketball too

If you’ve spent early mornings on the trails near downtown Austin, Texas you’ve probably crossed paths with Sarah Lancaster — 5 feet, 8 inches of mostly limbs and ponytail, casually eating up miles faster than you could drive on the Hike and Bike Trail, or sprinting so fast around the Austin High track off Lady Bird Lake that her male training partners have to tag each other in for pacing duty.

Lancaster is not just the fastest runner in Austin. She's one of the fastest women in the entire country, and she's competing at the U.S. Olympic Trials in Eugene, Ore., on Friday in both the 1,500- and 5,000-meter runs.

Her personal bests of 4 minutes, 5.55 seconds and 15:13.56 are only a few seconds off the Olympic standards of 4:04.20 and 15:10, meaning she can make this summer's Tokyo Olympics team if she can shave a few seconds off her best times and place in the top three.

Texas legend Trey Hardee, a 2012 Olympic silver medalist in the decathlon, recently declared Lancaster the best athlete in Longhorns history on Twitter, although that actually has as much to do with her pedigree as a dual-sport athlete at UT in tennis and basketball as it does her running resume.

At 33 years old, Lancaster is nearly 15 years behind most of her competitors in terms of specific training for distance running. She works full-time as an attorney in Austin, but nearly everyone who has run with her or coached her agrees: the former tennis ace possesses an unbeatable work ethic and killer instinct that makes her a natural on the track, no matter how late she found the sport.

Tennis beginnings

Lancaster grew up in San Antonio playing every sport offered, but quickly found herself drawn to tennis and basketball. She started taking tennis lessons when she was six years old and was competing in statewide tournaments by the time she was 11.

Lancaster's mother, Kelly, says Sarah was competitive "in everything. It wasn't necessarily sports," and that she inadvertently stoked the fire a few times when Sarah drew a tough opponent during a travel tournament.

“I would say, ‘Oh gosh, you play so-and-so today, I just hope you get a point,’” Kelly Lancaster said. “Because maybe it was one of the top girls in Texas. She’s commented that I’d pack up our bags to check out of the hotel because I knew she was playing somebody (who was a top seed). And you can always go check back in, but if you don’t check out by 10 or 11, then you have to pay for a whole ‘nother day.

“She said, ‘I’d see mom packing up the bags and think, ‘Obviously, she doesn’t think I’m gonna win today, so I’m gonna show her!' I really didn’t do it for that reason. I was thinking, ‘We’re done, I’m tired, we’re going home.’ Little things like that, I guess, motivated her a little bit to prove me wrong.”

Lancaster played tennis, basketball and ran track during her freshman year at Alamo Heights High School before deciding to enroll in a tennis academy that her coach established more than 200 miles away in Conroe. The academy is no longer in existence, but at the time was affiliated with John Roddick, the older brother of tennis star Andy Roddick.

“I was 15 at the time and, looking back at it, I can’t believe my parents let me do that,” Lancaster said.

A typical day at the tennis academy included two hours of practice in the morning, home school sessions for five to six hours, and another afternoon practice session that could last anywhere from two to three hours. There were about five other female boarders, more young men, and a number of local kids from the area who drove in for practice every day.

“We had a good time,” Lancaster said. “It was definitely not your normal high school experience. ... We were at tournaments a lot, we would go to the movies or just normal things like that ... (but) you’re there to play tennis and you’re there to get good, you’re not there to be partying and having fun.”

Lancaster thrived in the environment, improving her national and state rankings to become one of the best players in Texas.

“For me, it was — I want to go and I want to get as good as I can and see what I can do,” she said of her motivation to attend the tennis academy. “Maybe a little part of me thought I was going to play professionally one day, but I think the focus for me was more on college ... making sure I was going to be recruited.”

Lancaster committed to Texas — "hands down my first choice" — but then suffered a stress fracture in her back and had to take a few months off from tennis. She moved back home and re-enrolled at Alamo Heights, where her old friends convinced her to play basketball again.

It was an easy sell. After all, she was already the best player when she was only a freshman.

"I talked to the UT tennis coach," Lancaster said. "'Hey, you know, I'd kind of like to play basketball. I think it would be fun for me and it might be good for me, coming back from this injury, to do a different sport.'" And she was agreeable to it as long as I taped my ankles for every practice or game."

The move was eerily prescient for her career at Texas. Also prescient — she ran a few track races (she said her best time was a 58-second 400 meters as a freshman).

Texas fight

Given her experience living away from home at the tennis academy, Lancaster’s transition to college and NCAA athletics was pretty seamless. The Texas women’s tennis team, which recently captured its third national championship, was solidly ranked within the top 10 to 20 programs in the nation during her years there, and as a senior in 2010, she helped the Longhorns to the Sweet 16 round of the NCAA Tournament while totaling a 25-8 singles record, including an 11-0 mark in the Big 12.

“She is one of the best competitors I ever coached,” former UT women’s tennis coach Patty Fendick-McCain said in a text message. “She was the most solid player I ever coached at her position and when the chips were down, I always knew she would come through. She didn’t care what line she played, but that she would get a ‘W’ and contribute to the team.”

Of her own heroics on the court, Lancaster says simply that her personal highlight of her college tennis career was “probably the fact that we beat A&M every time we played them.”

Bored over the summer after her senior year and with one extra semester of school to complete, Lancaster and one of her tennis teammates filmed a video of her doing a trick layup shot. They sent it to their coach, who forwarded the video to the women’s basketball coach at the time, Gail Goestenkors.

To Lancaster’s surprise, Goestenkors told her to go play some pick-up games that summer with the team.

"I went and played with them over the summer, and it was really just pick-up games, coaches couldn't come," Lancaster said. "I didn't really feel like I was completely in over my head, you know — I wasn't like, 'Oh, I'm better than any of these people that have been playing their whole lives and have been recruited to play at the University of Texas,' (but) I felt like I could hold my own."

Sight unseen, based on positive feedback from the players on the team, Lancaster was invited to officially join the roster in the fall.

"None of the coaches had ever seen me play and they basically told me that they would let me play on the team, which was a little bit terrifying,” she said. “The first practice, I was like, please do not miss a layup, please do not miss a layup.

"I think part of it was, the team was really young, there were six or seven freshmen. There was really only one other senior at the time on the team and I think they were just kind of like, 'Sarah knows how to be a student-athlete, she can help these freshmen.' And I guess they confirmed with some other people that I wasn't a terrible basketball player."

Lancaster stepped into the leadership role naturally, had fun at practice and was fine with getting less minutes as the season went on. Her personal highlight from her basketball career didn’t even take place in the Big 12.

"My only basketball highlight is in seventh grade, when I scored 46 points in a game," she said with a straight face.

'That’s just not something you see every day'

Paras Shah remembers the first time Lancaster showed up to a casual evening workout with RAW Running a few years ago. She made it up Wilke Road — a notoriously brutal 300-meter, 10.8% grade hill in the Barton Hills neighborhood — for all eight repeats, just a few strides behind Shah and the other former NCAA Division I male runners in the group.

"I asked her where she ran in college and she said she didn’t," said Shah, who ran at LSU. "(I thought) that’s obviously not possible. I just didn’t believe her.”

Lancaster was always naturally fast.

In mile time trials throughout her athletic career, she’d routinely clock in just under 5:30.

"Every running drill we did, Sarah was fastest and had the best endurance," Fendick-McCain said. "Her attitude was to leave blood on the court if necessary. She had better endurance than any other player I ever coached or that she played against. If it was a test of wills and endurance, she would always find a way to win."

When Lancaster started law school, she played in various recreational leagues and just had fun ("law school was the most free time I've ever had in my life," she said) while casually completing her first half-marathon. But a few years into the workforce, she happened to meet UT club running coach Kyle Higdon, a UT graduate student, and she asked him to train her to break five minutes in the mile.

"I just felt like that would be a cool thing to say I could do," she said. "And I had actually talked to multiple guys who told me that they tried to do it and couldn't do it. So I was, you know, even more motivated to try."

With light mileage (20-25 miles per week) and a few basic workouts under her belt, she clocked 4:46 in her first 1,500 meter race — the equivalent of a 5:07 mile. By the end of the spring, she had improved to about 4:30 for the 1,500, an incredible time for a brand new runner, albeit one who was 28.

As she watched the Rio Olympics that summer, she wondered: Could she qualify for the 2020 Olympic Trials?

“I had no concept of what a good time was,” she said.

The idea of the Trials wasn’t quite a solidified goal at that point — just a little bug in her head that popped up every now and then. With Higdon finishing his studies and moving on with his career, Lancaster evaluated her group running options, which, in Austin, are mostly marathon training groups that meet in the wee hours of the morning, or more casual after-work clubs.

She chose the latter, and started showing up to RAW. That’s where she met Shah, who helps organize the annual Schrader 1600 every May for high school runners and members of the community.

At the 2018 event, with about two years of casual training under her belt, Lancaster ran 4:37.55 for 1,600 meters. The girl who kicked the boys’ butts at RAW workouts every Tuesday was legit.

Mike Kurvath remembers the race very vividly. Then 28, the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) track alum ran 4:17 in his section. At the time, he was thinking of moving on from running competitively.

"I remember that very specifically, because in the final 200 meters, she elbowed her way through a couple of high schoolers and it was a really strong move," Kurvath said. "That’s just not something you see every day.

"I was thinking that I was going to be done with running. After I saw that race ... it was actually quite inspiring. After a couple weeks of training with Sarah, you knew the potential was there. It gave me a second chance at my own running."

Kevin Kimball, a UT track alum, offered to help train her.

"Kevin was like, 'you could definitely run the Olympic Trials qualifying time,'" Lancaster said. “In the back of my mind, I had always thought I could … I haven't really been doing that much training and I can already run this fast, like, why can't I run, you know, sub-4:10 in the 1,500? I mean, looking back, that is kind of crazy to think about, but it probably benefited me that I had no real knowledge of running because I didn't see any limitations for myself.”

To make the 2021 Olympic Trials, the qualifying time in the 1,500 meters was 4:06, the equivalent of a 4:25 mile and 4:24 1,600 — a full 13 seconds faster than she had just run.

"Kevin was like, 'I think you can do it,' and I was like, 'all right, well, I'll give it a go.'"

2021 Olympic Trials

Lancaster definitely falls into the camp of athletes who benefited from having an extra pandemic year to train in preparation for the Olympic Trials.

She struggled with injuries in 2019 but regained form in early 2020, running an impressive 15:56 in a 5K time trial at the beginning of the pandemic. That made her consider switching events. She improved her time to 15:34 in December, then ran her Olympic Trials qualifying marks in a two-week period in May.

The major change she made in that six-month period was working with 1996 Olympian Juli Benson. The longtime coach has mentored some of the world’s best distance runners, including Jenny Simpson, whom she guided to a gold medal in the 1,500 at the 2011 World Championships.

"I was very taken aback," Benson said when Lancaster reached out to her. "That’s how unusual it is. I’ve been in the sport for a very long time and her story is really unique.

"I was certainly curious, but it was fairly late into the Olympic year to take on a new athlete who was trying to qualify for the Trials, but her story was so unique and her approach and perspective so intriguing that I definitely wanted to take up the challenge and she’s proven to be remarkable at every turn.

"She can handle everything I throw at her and it’s been really fun. It’s so rare and unique and surprising and refreshing and all of those adjectives, but she is an incredible athlete, I’ll say that."

For the Trials, Lancaster decided to focus on the 1,500, where she's the 14th seed, but also declared in the 5,000, where she's the 17th seed, as a backup plan in case she were to fall or otherwise not advance from her preliminary race. The first round of both races are Friday; the finals are on Monday.

Kurvath, who recently clocked his own personal best of 14:34 in the 5,000, said he knows Lancaster is capable of breaking the 15-minute barrier because they do all of their workouts together.

"I’ve seen it. I’ve seen the workouts, I’ve done the workouts," he said. "She’s been there with me and I just ran 14:34."

Benson thinks Lancaster is just tapping the surface of what she can do in the sport.

"The other thing that's really, really fascinating about Sarah — she has got the most incredible race instincts," Benson said. "She races as if she's been on a world-class stage for seven or eight years. Her instincts are brilliant. ... I think she really loves to compete and it’s really no more complicated than that. Yes, she has interesting genetics, yes, she has really interesting talent, but I think she keeps it really simple and just wants to go out and see how many people she can beat.”

Lancaster isn’t sure if she’ll keep racing after this year. The World Athletics Championships are hosted by the United States next year, which presents a unique opportunity. She’s engaged to be married this fall. She’ll be 34 next year. For right now, it’s all about soaking in the realization of a long-awaited dream.

And no, she’s not totally sure where her affinity for middle-distance running comes from, either.

"Tennis is an individual sport," she said. "It’s a high-pressure situation, you know you’re out there playing someone and you can only look at yourself (for) the outcome. You can’t blame anyone else. I think that translates to running. It’s you out there.

"I think I’ve always just wanted to win, I’ve always wanted to compete well and that’s just kind of ingrained in me. So I don’t know if I have a better answer for you than that.”

(06/18/21) Views: 103Johanna Gretschel

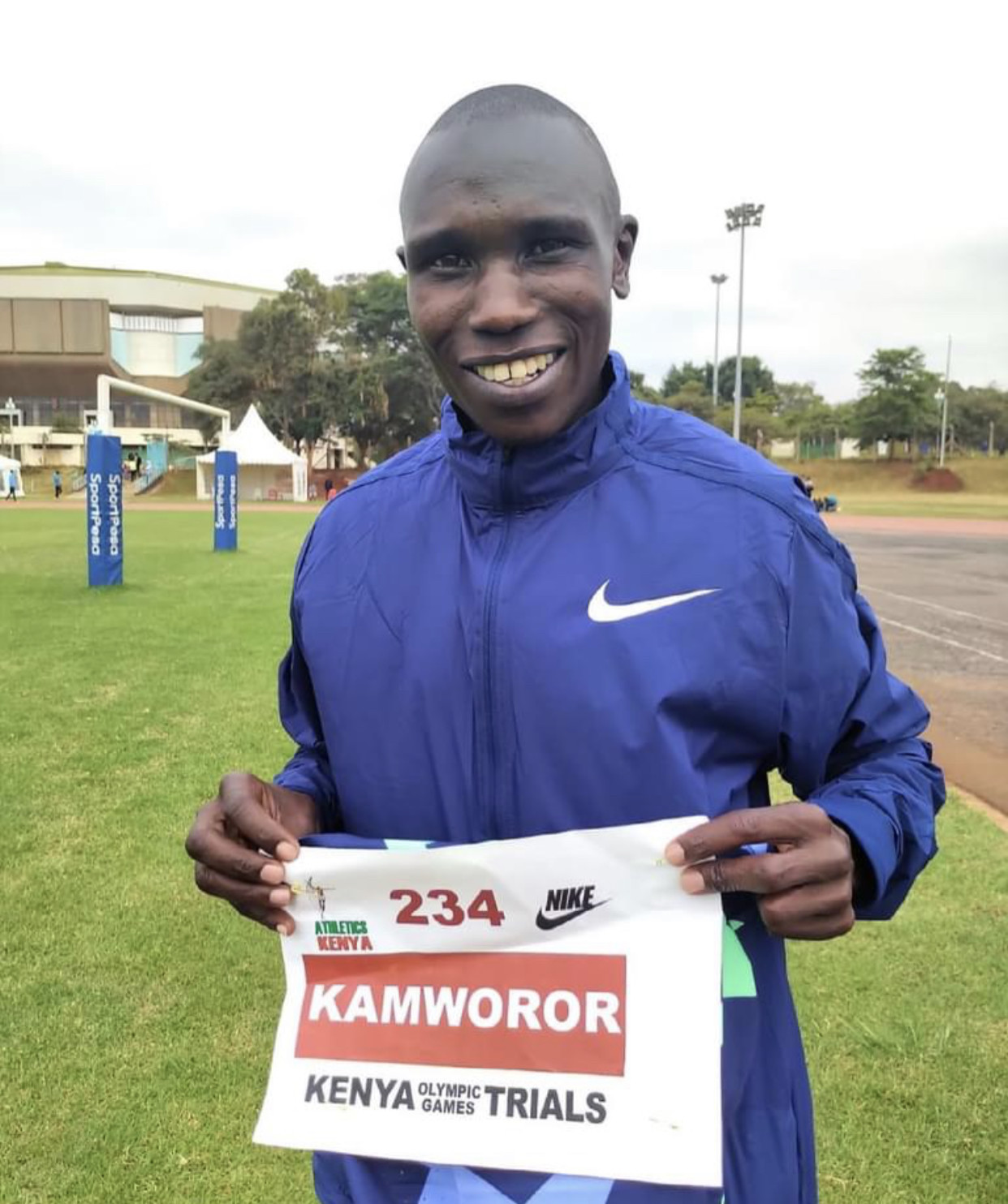

Geoffrey Kamworor ran the fastest time for 10000m in history at altitude

The 10000m race at the Kenyan Olympic Trials was one amazing event. The Kenyan Tokyo Olympic Trials happening June 17 to June 19 were moved from the Kipchoge Keino Stadium in Eldoret, to Moi International Sports Centre (MISC), Kasarani. Kasarani is located approximately 10 kilometres outside of Nairobi.

Athletics Kenya (AK) announced via press release that the changes are needed to test systems and requirements in readiness for the World Athletics Under-20 Championships which are planned for Aug. 17 to Aug. 22.

Geoffrey Kamworor clocked 27:01 for 10000m in the Kenyan Olympic Trials today. No one has run faster at altitude.

"I'm really happy to have qualified for the Olympics by running the fastest time in history in altitude. Now, we’re building on towards the bigger goal ahead," says Geoffrey Kamworor.

The altitude at the stadium is 1865 meters or 6118 feet.

Rodgers Kwemoi was second in a very fast 27:05.51 and Weldon Kipkirui Langat was third clocking 27:24.73. Ronex lead from the start but dropped out at 7k.

Geoffrey and Kwemoi were behind, when Geoffrey decided to break, Kwemoi resisted but with two laps to go Geoffrey made his big break and widen the gap winning by just over four seconds.

(06/18/21) Views: 102Tokyo Marathon October 17 will only be open to residents of Japan

Organizers of the Tokyo Marathon have announced that the upcoming edition of their race, which is set for October 17, will only be open to residents of Japan. The country’s COVID-19 restrictions are still quite strict, and there is no word on when they might be eased, so organizers made the difficult decision to block any international runners from travelling to Japan and competing in the marathon. International athletes who were registered for the Tokyo Marathon will have their entries deferred until the 2023 event.

Earlier this year, Tokyo Marathon organizers set their race date, moving the event from its traditional late February or early March run date to the fall. The run wouldn’t have worked so early in the year due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, but they hoped it would be able to go ahead later in 2021. At the moment, the race is still a go, but it will be a Japan-only event.

When organizers decided on the October race date, they also noted that the event capacity would be lowered to 25,000 runners from the usual field size of around 38,000. Nothing has been published regarding the race capacity in its new field format.

Japan has been able to host many big road and track races throughout the pandemic, but they’ve mostly been for runners already living within the country’s borders. The Tokyo Marathon may be the biggest Japanese race to bar international competitors, but it’s certainly not the first. The pandemic forced many popular races to only welcome citizens and residents of Japan, including last year’s Fukuoka International Marathon and the 2021 Lake Biwa, Osaka International Women’s and Nagoya Women’s marathons.

Unfortunately for anyone hoping to run in Tokyo, they will have to wait more than a year to do so, as international entries aren’t being deferred to 2022, but 2023.

(06/21/21) Views: 98Ben Snider-McGrath

Woody Kincaid Wins the Men’s 10,000 Meters at the Olympic Track and Field Trials

In the first track final of the U.S. Olympic Track & Field Trials, Woody Kincaid, Grant Fisher, and Joe Klecker earned spots on Team USA heading for Tokyo.

Kincaid, 28, finished in 27:53.62, by virtue of a blistering final 400 meters, which he covered in 53.47. His Bowerman Track Club teammate Fisher, 24, was less than a second behind in 27:54.29, and Klecker, also 24, of the new On Athletics Club in Boulder, ran 27:54.90.

Ben True, 35, finished in hard-luck fourth place; he couldn’t match the closing kick of the three Olympians and crossed the line in 27:58.88. True, who has never made an Olympic team, will be the alternate.

The race opened up with a fast pace, because most of the field did not have the 27:28 Olympic qualifying standard they need—along with a top-three finish—to earn a trip to the Games. This race was the last chance for them to run the standard.

Conner Mantz of BYU, Robert Brandt of Georgetown, and Frank Lara of Roots Running ran up front for the first two miles, but by halfway, reached in 13:56, the pace slowed, leaving no hope for anyone without the standard to get onto the team. Lopez Lomong dropped out, grabbing his right leg, as did Eric Jenkins, leaving only five men with the standard in the field.

The big crowd in the early miles was distracting for Kincaid. “My confidence was the lowest 10 laps in, that’s when the doubts really crept in,” he said in a press conference after the race. But as the miles clicked off, the pace slowed, and he made his way to the front, he felt better. “With four laps to go, this is what I had practiced in my mind over and over. I’m going to get into third or fourth position, just like practice, and that’s what happened.”

Kincaid said his last lap was the easy part: “It’s just everything you’ve got,” he said. “Getting there, in a position to win, is the hard part.”

He had praise for his teammate, Fisher, whom he runs with every day. “It’s a shame that I like him so much, because I have to race him all the time,” Kincaid said.

Kincaid said he plans to race the 5,000 meters and if he makes the team in that event, he’ll do both the 10,000 meters and 5,000 meters at the Games.

Fisher was soaking in the moment. “I’ve dreamed about this moment, but even now it doesn’t feel real,” he said in the post-race press conference. “I don’t even know how to describe it, but I’m just so happy.”

Klecker, the third-place finisher, had his collegiate career at the University of Colorado shortened by the pandemic. “This means a lot,” he said. “I mean I had my NCAA career cut short. I never won an NCAA title, but making an Olympic team makes up for that.”

He is the son of Janis Klecker, a 1992 Olympian in the marathon for the U.S. Her advice? Candy. “She told me that the night before she made an Olympic team, she ate a Snickers bar, and I followed that to a tee and it worked out,” Klecker said.

True said he was turning his attention to the 5,000 meters later in the meet, but he has plenty of other things to look forward to. His wife is expecting their first child on July 15, and he’ll make his marathon debut this fall.

Galen Rupp, who already is representing the U.S. in the marathon, finished sixth in 27:59.43.

It is the first Olympics for Kincaid, Fisher, and Klecker. The event represents a changing of the guard—the top three are a complete turnover from the 2016 squad, when Rupp, Shadrack Kipchirchir, and Leonard Korir were the Americans who went to Rio in the event.

(06/19/21) Views: 78Runner’s World

Track star Allyson Felix launches her own shoe brand after breaking up with Nike

After breaking up with Nike in 2019 and landing a sponsorship deal with Gap’s Athleta, the brand’s first, track and field star Allyson Felix is launching her own shoe business.

On Wednesday, Felix debuted Saysh, which she pitches as a lifestyle brand designed with women in mind. Saysh’s first product, the Saysh One sneaker, retails for $150 and is currently available for preorder in three colors. Other products are in the works, according to the company’s website.

Customers are also able to buy membership to the “Saysh Collective,” which comes with workout videos and occasional interactions with Felix. An annual membership costs $150, while a monthly pass goes for $10.

The announcement comes after Felix finished second in the 400 meter at the U.S. Olympic Track and Field trials this past weekend, clinching her spot in the Tokyo Olympics. Felix is the most decorated female track and field star in U.S. history.

Time first reported on Felix’s shoe launch. In an interview with the magazine, Felix said the women’s footwear market is underserved, and that the mentality has often been to “shrink it and pink it.”

“It’s really about meeting women where they are,” Felix said. “It’s for that woman who has been overlooked, or feels like their voice hasn’t been heard.”

Felix departed a deal with Nike in 2019 after she said the company wanted to pay her 70% less following her pregnancy. She has since been invested in raising awareness around health-care inequities facing Black mothers.

Felix serves as Saysh president, while her brother and business partner Wes holds the CEO title. The company has raised $3 million in seed money from a broad range of venture investors, according to Time.

It’s unclear if Athleta, where Felix has a multiyear sponsorship deal to design clothing, will begin to carry the shoes in the future.

(06/23/21) Views: 71Lauren Thomas

Use Threshold Training to Run Faster, Longer

The primary purpose of training is to enable your body hold a faster pace for a longer time. The first step toward getting faster is building an aerobic base of easy miles and improving running economy through strides and short intervals. After you’ve developed a base, the best way to go faster for longer is through threshold training.

Mention threshold training in a group of coaches, and an Anchorman-like rumble will erupt in a minute or two. If you search threshold-training philosophy online, keywords like “tempo” and “steady state” seem to mean slightly different things to everyone. But there’s no need for things to escalate quickly into a brawl over slight disagreements on terminology, since the basic principles are universal.

What do we mean by threshold?

Contrary to conventional wisdom, lactate is a fuel source, not a boogeyman that forces you to slow down. However, it is associated with waste products that force you to slow down, so for most runners it’s a distinction without a difference. Lactate threshold (LT) is the tipping point when your body produces more lactate than it can use and waste products accumulate without being cleared.

Similar to LT, anaerobic threshold (AnT) measures the point at which your body starts burning glycogen rather than fat as its primary fuel source. AnT and LT are often close to one another, and most athletes can probably get by without differentiating them.

In lieu of lab testing, LT usually corresponds to an effort you could hold for about an hour, though it varies based on physiology, training background and the LT definition you prefer. It should feel somewhat hard, a seven or eight out of 10 on the perceived exertion scale, where you can talk in short sentences, but not sing.

You can calculate your LT heart rate (LTHR) by doing a 30-minute time trial. At 10 minutes, lap out your watch—the average heart rate for the final 20 minutes is your LTHR.

Why do we care about lactate threshold?

Lactate threshold is often the most important element in determining running success in long-distance races, even at races far longer than an hour. The power of LT likely comes from a few factors. First, it is trainable, meaning well-trained athletes will have higher LTs and will run faster in races (whereas VO2 max is less willing to budge). Second, exceeding LT results in relatively rapid onset of fatigue, so improving LT raises the “point of no return.” Finally, LT is usually associated with performance at lower levels of exertion like aerobic threshold and even more intense exertion levels, like VO2 max.

What matters is how fast you can run at your LT, or your velocity at LT (vLT). On trails, vLT gets a bit more complicated, mixing how fast you can run on flat ground with your ability on hills and technical terrain.

How can we improve vLT on trails?

High-volume aerobic training can improve LT the most. So before worrying too much about intricate workouts, build aerobic volume at “Zone two.” Zone two itself is subject to debate, but you can think of it as an aerobic intensity that is a five or six on the perceived exertion scale, or easy to easy-moderate exertion where you can comfortably hold a conversation. For my athletes, we use 81 to 89 percent of LTHR.

For most athletes, at least 80-percent of your training should be aerobic. Add fast strides and short intervals to aerobic training to improve running economy, and you are ready for intervals that directly target LT. The extent of aerobic training depends on your background and goals, but most athletes should spend at least a few weeks doing easy running before jumping into harder workouts.

Now is when “threshold” or “tempo” running comes in. Remember, tempo usually corresponds with the effort you could sustain for about an hour. It’s not a race—by training at LT, rather than going as fast as you can, you can elicit more improvement. The general principle is to run 20 to 45 minutes at LT over the course of a workout, broken up as needed, on terrain that suits your goals.

What are examples of LT workouts?

Within those general constraints—20 to 45 minutes at LT—LT workouts can take any form. You can do the LT workout in one tempo run, or over the course of intervals with half the recovery time or less (Coach Jack Daniels would call these “cruise intervals”). Here are five examples (do 20 minutes of easy running before and after each workout).

The Steady Freddie: Thirty minutes at LT on terrain similar to your race. This workout is hard, but not so taxing that you’ll need to be scraped off the trail with a spatula. You can also take a couple minutes of easy running recovery in the middle. This workout is simple and achievable, good for all levels.

The Cruisey Susie: Six to eight x 4 minutes at LT with two minutes of easy recovery. This “cruise interval” workout is an ideal intro to LT training, since the recovery periods make it comfortable. It has the benefit of making sure you are running fast at LT, since many trail runners will have biomechanical fatigue with sustained efforts that is lessened with shorter intervals. Don’t go too fast, even though you’ll be tempted to.

The Crooked Buzzsaw: Eight to 12 x 3 minutes uphill at LT with one minute of jog down recovery. For this workout, you need a long hill. This workout is relatively low stress, with reduced pounding, so is a great option for low volume runners or runners over 50.

Like Riding a Bike: Two x 20 minutes at LT with five minutes of easy recovery. This workout mimics the classic bike workout designed to improve power. Since the physiological principles are the same, it’s also one of the best run workouts, but comes with additional injury risk since 40 minutes at LT running involves lots of pounding on your legs. Only advanced runners should do the full workout.

Ladder to Heaven: 1/2/3/4/5/4/3/2/1 minutes at LT with one minute easy recovery. This workout is similar to the Cruisey Susie, but with some variation in interval length that keeps it fresh. Ladders are a great option to optimize time at LT while keeping the run interesting.

When are LT workouts most beneficial?

The goal is to train your body to go faster at LT, so it’s essential to do LT workouts rested and ready, providing enough recovery time afterward for adaptation. In general, do no more than two LT workouts each week. For trail runners, a great option is to embed a LT workout within a weekend long run. For example, the Crooked Buzzsaw (30 minutes at LT) can be added in the middle of a two- or three-hour run. Like all training, LT workouts have diminishing returns, so after four to six weeks, mix up your training, emphasizing more intense VO2 max efforts or longer aerobic threshold training.

Smooth is sustainable. Lactate-threshold training helps make your smooth pace faster, which means you’ll be able to sustain faster paces on race day.

(06/19/21) Views: 62

Trail Runner Magazine

Mo Farah’s Manchester mission

Olympic champion hopes to beat the 10,000m qualifying standard for the Tokyo Games at an invitational race on the first day of the Müller British Athletics Championships

After shaking off the ankle problem which affected his performance at the Müller British 10,000m Championships and European Cup event at the University of Birmingham last week, Mo Farah will have another crack at the Olympic qualifying mark in a special invitational race on Friday June 25 at the Müller British Athletics Championships in Manchester.

Farah clocked 27:50.64 in Birmingham on June 5 as he finished second Briton home behind Marc Scott and eighth overall in a race won by Morhad Amdouni of France. But after seeking treatment for the injury, the 38-year-old is going to Sportcity in Manchester next week to attack the 27:28.00 qualifying mark.

Farah insisted in Birmingham last week that he can still get into shape to defend his Olympic title in Tokyo and rumours are he was in excellent form up until the eve of the British trials and European Cup race but the edge was taken off his fitness in the final fortnight due to the injury and slight illness.

This invitational 10,000m race will kick off a busy three-day Olympic trials meeting and will evoke memories of classic 10,000m races on Friday night at the AAA Championships from yesteryear.

Most notably, for example, Dave Bedford set a world record of 27:30.8 at Crystal Palace in 1973. Ironically, Farah needs to run just 2.8 seconds quicker next Friday too, although it is unlikely to be easy and the veteran distance runner will rely on several pacemakers to help him in his quest.

(06/20/21) Views: 61Athletics Weekly

The U.S. Track and Field Athletes Who Qualified for 2021 Olympics

The team representing the U.S. in Tokyo is a mix of veterans and first-timers.

The U.S. Olympic Track and Field Trials are taking place at Hayward Field in Eugene, Oregon, from June 18 through June 27, and the top three finishers in each event will represent the United States at the Olympic Games in Tokyo. Here’s a list of those who have already qualified and have met the Tokyo Olympic Standard.

Aliphine Tuliamuk — Women’s Marathon

Qualified: First in 2:27:23

Olympic history: This will be Tuliamuk’s first Olympic appearance.

Molly Seidel — Women’s Marathon

Qualified: Second in 2:27:31

Olympic History: This will be Seidel’s first Olympic appearance.

Sally Kipyego — Women’s Marathon

Qualified: Third in 2:28:52

Olympic History: 2012 — Silver medal in the 5,000 meters.

Galen Rupp — Men’s Marathon

Qualified: First in 2:09:20

Olympic history: 2016 — Bronze medal in the marathon, fifth in 10,000 meters; 2012 — silver medal in 10,000 meters, seventh in 5,000 meters; 2008 — 13th in 10,000 meters.

Jake Riley — Men’s Marathon

Qualified: Second in 2:10:02

Olympic history: This will be Riley’s first Olympic appearance.

Abdi Abdirahman — Men’s Marathon

Qualified: Third in 2:10:03

Olympic history: 2012 — DNF in marathon; 2008 — 15th in 10,000 meters; 2004 — 15th in 10,000 meters; 2000 — 10th in 10,000 meters.

(06/19/21) Views: 55Runner’s World