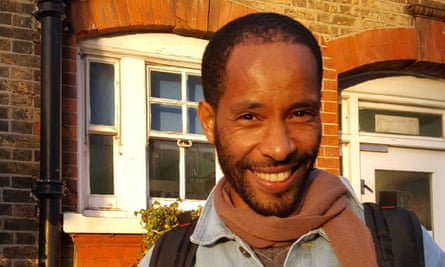

The current course record holder for the Beckenham parkrun (15 min 58 sec) looks stricken as he recalls the most challenging run of his life. It wasn’t a timed 5K in the suburbs but a desperate, terrifying sprint, head down, heart pounding, through a maize field toward a perimeter fence, sick with dread that the armed guards will stop shouting and start shooting.

That was more than two years ago, and since then, Dame Dibaba, a refugee from the Oromia region of Ethiopia, has been, in his words, a “ghost” in this country, albeit a ghost that runs like the wind.

Dibaba’s troubles began early in 2015, when he left his parents, three younger sisters and the family farm to work in a relative’s photocopying shop in Ambo, 74 miles from the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa. As an Oromo, Dibaba probably knew he was taking a risk. Although the Oromo people are the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia, making up around 35% of the population, they are routinely persecuted. On 26 October this year, security forces opened fire on Oromo protesters in Ambo, killing eight people and injuring 20. Last year, more than 700 people were killed during a sustained bout of unrest.

Dibaba was charged with disseminating Oromo liberation propaganda and imprisoned for six weeks. He was allowed home, but was subsequently intimidated, arrested and imprisoned again. During this incarceration he was beaten up, losing teeth and sustaining wounds to his arm in the process. One day, while working under armed guard in the maize fields surrounding the prison, he ran for it.

“The corn was high and I could not see the guard, so I decided he could not see me. I kept down and ran low to the edge of the field. I could hear them shouting but I looked forward and kept running.”

The next few months were spent on the road, working where possible, relying on the goodness of others and surviving. Dibaba walked to Asosa, then Ad Damazin in the Sudan and north to Khartoum, following the well-trodden refugee route to Benghazi in Libya and on to Tripoli, to take his chances on the sea crossing to Italy.

“Some smugglers are good people. You keep walking, you’re afraid people may kill you, but some people will give you food and try to help. I got on the boat because all my other options were closed,” Dibaba says.

“There were so many people in the boat. I was in the bottom, I could not see out or smell fresh air. The engines made a noise. Everyone was vomiting, I was vomiting, too, but there was nothing was in my stomach. I felt so ill for 19 hours.”

It was while he was in the Calais refugee camp known as the Jungle that Dibaba’s repeated attempts to escape over razor wire, to take his chances under a ferry-bound lorry, were captured by the mobile-phone cameras creating the footage for the BBC’s Exodus: Our Journey Continues.

Dibaba now lives in Lewisham, south London, where the generous people featured on the programme have welcomed him as a member of the family for more than a year now. His eyes brim as he talks about their kindness. He hesitates before he utters anything negative about his situation here in London, for fear of sounding ungrateful, but I suspect that sometimes he feels as alone and wretched as he did in that boat’s stinking hull.

While his legal representative navigates his case through the Home Office system, Dibaba lives on charity alone. He cannot work, cannot claim benefits, and last spoke to his mother three months ago. His father, who suffered a gunshot wound some years back, has been too ill to speak to his son since Dibaba left Ethiopia.

So, Dibaba runs.

His English family signed him up for Saturday parkruns, researched running clubs and settled on the redoubtable Kent AC, and bought him running shoes. Dibaba came along to the track one Tuesday last June and has scorched round it every week since. His running, says lead coach Ken Pike, is impressive.

“It’s too early to say whether Dibaba’s running can improve to top flight, but he’s making strong progress. I can see him shining at 10k distance and in cross country.”

GivenDibaba’s history, it’s hardly surprising that running his guts out over five miles of Surrey mud holds few fears. He sets out fast. And hangs on as best he can. “He’s suffered a bit with that kind of impetuous pacing,” says Ken, “but Dame is willing to learn, and I’m optimistic that he’ll raise his game. I see him every week working hard and getting results.’

For Dibaba, club running has given the waiting game of his daily life some structure. He looks forward to Tuesday evenings on the track, he joins the rest of the A team for long Sunday runs from Greenwich park, and he runs round his area to get to know the lie of the land.

The local mosque, and English lessons organised for him by his family, also bring warmth and compassion to flesh out his ghostly life, but running brings the most relief.

“When I am racing, I must try to forget about all my problems until I get to the finish. If memories of sadness come into my head, my legs will fail and my speed will go down.”

When he’s not running, that sadness returns, so Dibaba tries to dispel his gloom by talking with his hosts, or reading the English-language books donated to him. He’s currently working his way through the highly apposite Man’s Search for Meaning, by Viktor Frankl, although he’s struggling with the language.

Iolanda Chirico, founder and manager of Action for Refugees in Lewisham (AFRIL), a registered charity, agrees: “That’s why we encourage individuals like Dame to contact our organisation, for access to immigration solicitors, English-language education and local support services.

“We’re also here to show refugees that they can make a contribution to society and local culture by volunteering at our food bank and other fundraising initiatives, thereby practising their English and learning about local services.”

His running mates at Kent AC need Dibaba’s contribution too, to turn out for cross-country meetings and keep the club flying high in the league. They are doing everything they can to be his second foster family. This sense of being a key member of a team is essential for morale.

Dibaba smiles when he talks about his first cross-country race wearing his Kent AC vest. He invites his English family to the Saturday races now, to make them proud: “All these good people are helping me, even while I find it very hard to make a plan for my life, but I know that Kent AC people are my people.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion